Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most prevalent complication of type 2 diabetes with an estimated 65% of people with type 2 diabetes dying from a cause related to atherosclerosis. Adenosine‐diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists like clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel and ticagrelor impair platelet aggregation and fibrinogen‐mediated platelet cross‐linking and may be effective in preventing CVD.

Objectives

To assess the effects of adenosine‐diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (issue 2, 2011), MEDLINE (until April 2011) and EMBASE (until May 2011). We also performed a manual search, checking references of original articles and pertinent reviews to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing an ADP receptor antagonist with another antiplatelet agent or placebo for a minimum of 12 months in patients with diabetes. In particular, we looked for trials assessing clinical cardiovascular outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors extracted data for studies which fulfilled the inclusion criteria, using standard data extraction templates. We sought additional unpublished information and data from the principal investigators of all included studies.

Main results

Eight studies with a total of 21,379 patients with diabetes were included. Three included studies investigated ticlopidine compared to aspirin or placebo. Five included studies investigated clopidogrel compared to aspirin or a combination of aspirin and dipyridamole, or compared clopidogrel in combination with aspirin to aspirin alone. All trials included patients with previous CVD except the CHARISMA trial which included patients with multiple risk factors for coronary artery disease. Overall the risk of bias of the trials was low. The mean duration of follow‐up ranged from 365 days to 913 days.

Data for diabetes patients on all‐cause mortality, vascular mortality and myocardial infarction were only available for one trial (355 patients). This trial compared ticlopidine to placebo and did not demonstrate any statistically significant differences for all‐cause mortality, vascular mortality or myocardial infarction. Diabetes outcome data for stroke were available in three trials (31% of total diabetes participants). Overall pooling of two (statistically heterogeneous) studies showed no statistically significant reduction in the combination of fatal and non‐fatal stroke (359/3194 (11.2%) versus 356/3146 (11.3%), random effects odds ratio (OR) 0.81; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.44 to 1.49) for ADP receptor antagonists versus other antiplatelet drugs. There were no data available from any of the trials on peripheral vascular disease, health‐related quality of life, adverse events specifically for patients with diabetes, or costs.

Authors' conclusions

The available evidence for ADP receptor antagonists in patients with diabetes mellitus is limited and most trials do not report outcomes for patients with diabetes separately. Therefore, recommendations for the use of ADP receptor antagonists for the prevention of CVD in patients with diabetes are based on available evidence from trials including patients with and without diabetes. Trials with diabetes patients and subgroup analyses of patients with diabetes in trials with combined populations are needed to provide a more robust evidence base to guide clinical management in patients with diabetes.

Keywords: Humans; Aspirin; Aspirin/therapeutic use; Cardiovascular Diseases; Cardiovascular Diseases/prevention & control; Clopidogrel; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/complications; Dipyridamole; Dipyridamole/therapeutic use; Drug Therapy, Combination; Drug Therapy, Combination/methods; Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors; Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors/therapeutic use; Purinergic P2Y Receptor Antagonists; Purinergic P2Y Receptor Antagonists/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Ticlopidine; Ticlopidine/analogs & derivatives; Ticlopidine/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Adenosine‐diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

Patients with type 2 diabetes have a much higher risk of strokes and heart attacks than the general population. Most strokes and heart attacks are caused by blood clots. Adenosine‐diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists are drugs which prevent the aggregation ('clumping') of platelets and consequently reduce the formation of blood clots. These medications are used to prevent cardiovascular disease such as heart attacks and strokes in the general population. This review assessed if these medications would be useful in patients with diabetes. We included eight trials with 21,379 patients and a mean duration of follow‐up ranging from 365 to 913 days. Specific data for patients with diabetes were only available in full for one of these trials and partial data were available for two trials. Analysis of the available data demonstrated that adenosine‐diphosphate receptor antagonists (such as clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor, ticlopidine) were not more effective than other blood thinning drugs or placebo for death from any cause, death related to cardiovascular disease, heart attacks or strokes. There was no available information on the effects of adenosine‐diphosphate receptor antagonists on health‐related quality of life, adverse effects specially for people with diabetes, or costs. The use of adenosine‐diphosphate receptor antagonists in patients with diabetes needs to be guided by the information available from trials which included patients with and without diabetes. All future trials on adenosine‐diphosphate receptor antagonists should include data which relate specifically to patients with diabetes in order to inform evidence‐based clinical guidelines.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Adenosine‐diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists (clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel, ticagrelor) for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus Settings: out‐patients Intervention: ADP receptor antagonists Comparison: Aspirin (/dipyramidole)/placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | ADP receptor antagonist | |||||

|

All‐cause mortality (ticlopidine vs placebo) |

14.1% | 17.4% | RR 1.29 (0.71 to 2.32) | 335 (1) | moderate quality | Seea |

| Vascular mortality (ticlopidine vs placebo) | 11% | 10.5% | RR 0.94 (0.47 to 1.88) | 335 (1) | moderate quality | Seea |

| Myocardial infarction (fatal and non‐fatal) (ticlopidine vs placebo) | 11.7% | 9.3% | RR 0.78 (0.39 to 1.57) | 335 (1) | moderate quality | Seea |

| Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal) (a. ticlopidine vs aspirin) (b. clopidogrel vs aspirin & dipyramidole) | a. 0.14% b. 0.11% |

a. 0.9% b. 0.12% |

a. RR 0.56 (0.37 to 0.94) b. RR 1.12 (0.95 ‐ 1.32) |

a. 597 (1) b. 5770 (1) |

a. moderate quality b. moderate quality |

a. Seea b. Seeb |

| Health‐related quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated for diabetes sub‐population |

| Adverse effects | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated for diabetes sub‐population |

| Costs | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated for diabetes sub‐population |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aOnly one study with small number of participants providing data

bUnclear random sequence generation and high attrition rates

Background

Description of the condition

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder resulting from a defect in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. A consequence of this is chronic hyperglycaemia (that is elevated levels of plasma glucose) with disturbances of carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism. Long‐term complications of diabetes mellitus include retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy. The risk of cardiovascular disease is increased. For a detailed overview of diabetes mellitus, please see under 'Additional information' in the information on the Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group in The Cochrane Library (see 'About', 'Cochrane Review Groups (CRGs)'). For an explanation of methodological terms, see the main glossary in The Cochrane Library.

Diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the role of platelets

The most prevalent complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus is cardiovascular disease (CVD). It is estimated that 65% of patients with type 2 diabetes die of a cause related to atherosclerosis (Gu 1998). Risk of mortality and morbidity due to myocardial infarction, stroke and peripheral arterial disease are two‐ to four‐fold increased compared with the general population. Once diagnosed with having diabetes, overall survival is comparable to a patient with a prior myocardial infarction (Haffner 1998).

Given the upcoming pandemic of patients with diabetes, world wide prevalence is expected to increase from 2.8% in 2000 to 4.4% in 2030 (Wild 2004), cardiovascular disease will continue to be responsible for a large proportion of global healthcare expenditures. This stresses the need for preventive measures. In the development of a cardiovascular event, platelets play an important role. Platelet adhesion and subsequent activation on dysfunctional endothelium fuel the inflammatory process in the atherosclerotic plaque. After disruption of the plaque, large aggregates of platelets lead to vessel occlusion. In the patient with diabetes, anti‐aggregatory mechanisms in the endothelium are impaired (Ceriello 2004). Platelets are more susceptible to activation and aggregation (Kutti 1986) and antifibrinolytic activity is attenuated (Colwell 2003).

Description of the intervention

Adenosine‐diphosphate (ADP) is a platelet activator that is released from red blood cells, activated platelets and damaged endothelial cells which induces platelet adhesion and aggregation (Kam 2003). ADP receptor antagonists noncompetitively and irreversibly inhibit platelet ADP receptors preventing platelet activation. This prevents the activations of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor complex and prolongs bleeding time, impairs platelet aggregation and fibrinogen‐mediated platelet cross‐linking (Goodwin 2011). The result is a 50% to 70% inhibition of platelet fibrinogen binding achieved after three to five days (Kam 2003).

Adverse effects of the intervention

Gastrointestinal side effects and skin rashes are common. Neutropenia and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura are significant but rarely fatal adverse events. Recovery of platelet function is delayed after discontinuation of the medication for approximately three to seven days (Kam 2003). In terms of cost, ADP receptor antagonists are considerably more expensive than aspirin.

How the intervention might work

There are clues that ADP receptor antagonists are superior to aspirin in preventing cardiovascular disease. In a Cochrane review, clopidogrel and ticlopidine were slightly, but significantly, more effective than aspirin in preventing serious vascular events in high‐risk patients (previous clinical manifestations of cardiovascular disease) (Sudlow 2009). Other evidence was derived from an analysis of the diabetic subgroup in the CAPRIE‐study. In that trial, 15.6% of patients with diabetes experienced a vascular endpoint versus 17.7% in the aspirin group (P = 0.042). In addition, patients in the clopidogrel group had less bleeding events: 1.8% versus 2.8% in the aspirin group (P = 0.031) (Bhatt 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite the evidence for possible advantages, the role of ADP receptor antagonists in the treatment of patients with diabetes seems to be limited. A recent position statement by the American Diabetes Association suggested the use of clopidogrel only in case of allergy for aspirin or in combination therapy with aspirin for one year after acute coronary syndrome (ADA 2011). The high costs of ADP receptor antagonists seem to be the major reason for the modest position these drugs have in treatment strategies. Evidence from systematic reviews and meta‐analyses is lacking for ADP receptor antagonists in patients with diabetes. To value the use of these agents in the treatment of patients with diabetes, a well‐designed systematic review is needed.

Objectives

To assess the effects of adenosine‐diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials comparing an adenosine‐diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonist with another antiplatelet agent or placebo for a minimum of 12 months. Trials with blinded trial participants and investigators were preferred, however, single‐blind and unblinded trials were considered. We included studies published in any language.

Types of participants

Eligible patients were adults (18 years and older) with diabetes mellitus. Trials which used the current standard criteria to establish the diagnosis of diabetes at the time of the trial were preferred, however, we accepted authors' definitions (ADA 1997; ADA 1999; WHO 1980; WHO 1985; WHO 1998).

Types of interventions

Intervention

Any orally administered ADP receptor antagonist given on a continuing basis.

Control

Placebo, another antiplatelet agent or no treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Mortality

All‐cause mortality.

Mortality related to cardiovascular events (death from myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, or sudden death).

Cardiovascular events

Myocardial infarction (fatal and non‐fatal).

Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal).

Peripheral arterial disease.

Secondary outcomes

Adverse effects, such as any major bleeding event, defined as intracranial bleeding or bleeding requiring surgical intervention or transfusion.

Health‐related quality of life, ideally measured with a validated instrument.

Costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The following sources were used from inception to specified time for the identification of trials.

The Cochrane Library (issue 2, 2011).

MEDLINE (until April 2011).

EMBASE (until May 2011).

We also searched databases of ongoing trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/ with links to several databases and https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/).

For detailed search strategies please see under Appendix 1.

No additional key words of relevance were detected during any of the electronic or other searches. Thus, the electronic search strategies were not modified. Studies published in any language were included.

Searching other resources

We sought additional unpublished information and data from the principal investigators of all included trials. We performed an extensive manual search, checking references of original articles and pertinent reviews to identify additional studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

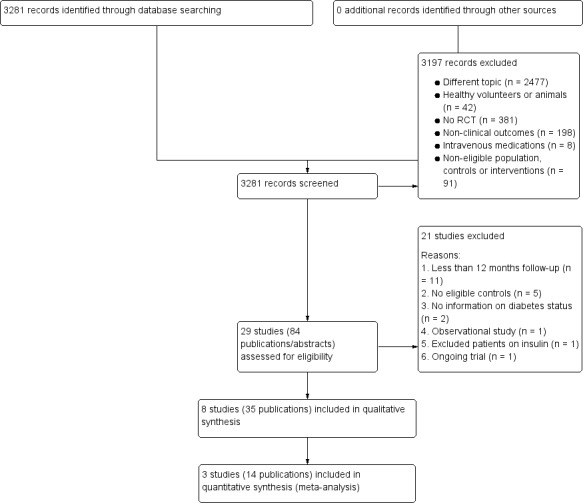

Two review authors (NV and MVD) independently scanned the titles and abstracts from the original search. If inadequate information was provided in the abstract to determine eligibility, the full text of the article was obtained. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion between the reviewers. In studies which did not report detailed subgroup data about patients with diabetes, we contacted the principal investigators for additional information. An adapted PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses) flow‐chart of study selection (Figure 1) (Liberati 2009) is attached.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

For studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, we extracted relevant population and intervention characteristics using standard data extraction templates (for details see 'Characteristics of included studies; Table 2; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4).

1. Overview of study populations.

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) and control(s) | [n] screened | [n] randomised | [n] ITT | [n] finishing study | [%] of randomised participants finishing study | |

| AAASPS | I(d): Ticlopidine 250 mg bd (diabetes patients) C(d): Aspirin 325 mg bd (diabetes patients) I(t): Ticlopidine 250 mg bd (all patients) C(t): Aspirin 325 mg bd (all patients) |

I‐ | I(d): 359 C(d): 379 I(t): 902 C(t): 907 |

I(d): 359 C(d): 379 I(t): 902 C(t): 907 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 626 C(t): 661 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 69.4 C(t): 72.9 |

|

| CAPRIE | I(d): Clopidogrel 75 mg daily (diabetes patients) C(d): Aspirin 325 mg daily (diabetes patients) I(t): Clopidogrel 75 mg daily (all patients) C(t): Aspirin 325 mg daily (all patients) |

‐ | I(d): 20% C(d): 20% I(t): 9599 C(t): 9586 |

I(d): 20% (1920) C(d): 20% (1917) I(t): 9599 C(t): 9586 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 9577 C(t): 9566 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 99.8 C(t): 99.8 |

|

| CATS | I(d): Ticlopidine 250 mg bd (diabetes patients) C(d): Placebo (diabetes patients) I(t): Ticlopidine 250 mg bd (all patients) C(t): Placebo (all patients) |

‐ | I(d): 172 C(d): 163 I(t): 525 C(t): 528 |

I(d): 172 C(d): 163 I(t): 519 C(t): 515 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 287 C(t): 364 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 54.7 C(t): 68.9 |

|

| CHARISMA | I(d): Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily (diabetes patients) C(d): Aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily (diabetes patients) I(t): Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily (all patients) C(t): Aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily (all patients) |

‐ | I(d): 3304 C(d): 3252 I(t): 7802 C(t): 7801 |

I(d): 3304 C(d): 3252 I(t): 7802 C(t): 7801 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 79.6% C(t): 81.8% |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 79.6 C(t): 81.8 |

|

| CURE | I(d): Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 to 300 mg daily (diabetes patients) C(d): Aspirin 75 to 300 mg daily (diabetes patients) I(t): Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 to 300 mg daily (all patients) C(t): Aspirin 75 to 300 mg daily (all patients) |

‐ | I(d): 1405 C(d): 1435 I(t): 6259 C(t): 6303 |

I(d): 1405 C(d): 1435 I(t): 6259 C(t): 6303 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 78.9% C(t): 81.2% |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 78.9 C(t): 81.2 |

|

| Park | I(d): Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 100 to 200 mg daily (diabetes patients) C(d): Aspirin 100 to 200 mg daily (diabetes patients) I(t): Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 100 to 200 mg daily (all patients) C(t): Aspirin 100 to 200 mg daily (all patients) |

‐ | I(d): 340 C(d): 364 I(t): 1357 C(t): 1344 |

‐ | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 327 C(t): 313 |

‐ | |

| PRoFESS | I(d): Clopidogrel 75 mg daily (diabetes patients) C(d): Aspirin/dipyridamole 25 mg/200 mg bd (diabetes patients) I(t): Clopidogrel 75 mg daily (all patients) C(t): Aspirin/dipyridamole 25 mg/200 mg bd (all patients) |

‐ | I(d): 2840 C(d): 2903 I(t): 10.151 C(t): 10.181 |

I(d): 2840 C(d): 2903 I(t): 10.151 C(t): 10.181 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 7736 C(t): 7095 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 76.2 C(t): 69.7 |

|

| TASS | I(d): Ticlopidine 250 mg bd (diabetes patients) C(d): Aspirin 650 mg bd (diabetes patients) I(t): Ticlopidine 250 mg bd (all patients) C(t): Aspirin 650 mg bd (all patients) |

‐ | I(d): 291 C(d): 306 I(t): 1529 C(t): 1540 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 1529 C(t): 1540 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 828 C(t): 941 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 54.2 C(t): 61.1 |

|

| Total | All interventions (diabetes patients) | 8711 (and CAPRIE participants) | |||||

| All controls (diabetes patients) | 8802 (and CAPRIE participants) | ||||||

| All interventions (all patients) | 38,124 | ||||||

| All controls (all patients) | 38,190 | ||||||

| All interventions and controls (diabetes patients) | 21,379 | ||||||

| All interventions and controls (all patients) | 76,314 |

"‐" denotes not reported

Abbreviations:

bd: twice daily; C: control; C(d): intervention (diabetes patients); C(t): intervention (all patients); I: intervention; I(d): intervention (diabetes patients); I(t): intervention (all patients); ITT: intention‐to‐treat

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (NV and MVD) assessed each trial independently. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, or with consultation of a third party.

We assessed risk of bias using The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool (Higgins 2011). We used the following risk of bias criteria.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other bias.

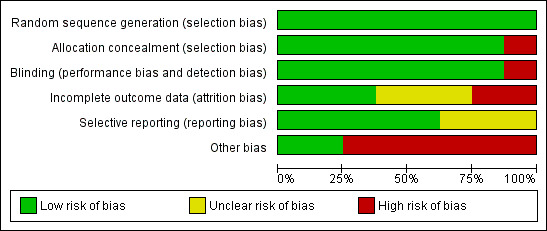

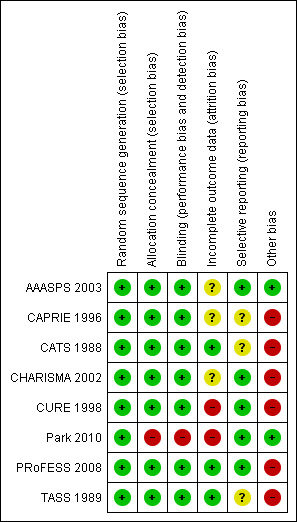

We judged risk of bias criteria as 'low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk' and evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). A 'Risk of bias' figure (Figure 2) and a 'Risk of bias summary' figure (Figure 3) are attached.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

We assessed the impact of individual bias domains on study results at endpoint and study levels.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data are expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We planned to calculate the risk difference (RD) and convert it into the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) or the number needed to treat to harm (NNTH) taking into account the time of follow‐up if the overall estimate of effect was statistically significant.

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to take into account the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over trials, cluster‐randomised trials and multiple observations for the same outcome. However, no such trial designs were included in this review.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to obtain relevant missing data from authors and carefully performed evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT), as‐treated and per‐protocol (PP) population. We investigated attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals and critically appraised issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example, last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF)).

Assessment of heterogeneity

As there was substantial clinical heterogeneity, study results were only reported as meta‐analytically pooled effect estimates for stroke (fatal and non‐fatal). We identified heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots, by using a standard Chi2 test and a significance level of α = 0.1, in view of the low power of this test. We specifically examined heterogeneity with the I2 statistic quantifying inconsistency across studies to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003), where an I2 statistic of 75% and more indicates a considerable level of inconsistency (Higgins 2011). In the presence of considerable statistical heterogeneity we used a random‐effects model for pooling.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we had identified more than 10 RCTs, we planned to use funnel plots to assess for the potential existence of small study bias. There are a number of explanations for the asymmetry of a funnel plot (Sterne 2001) and we planned to carefully interpret results (Lau 2006).

Data synthesis

We summarised data statistically if they were available, sufficiently similar and of sufficient quality. We performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines referenced in the newest version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

The table of comparisons was divided into all possible outcomes (e.g. all‐cause mortality, disease specific death). It was not possible to subdivide into different dosages within the outcome subgroups as these data were not available.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

No further subgroup analyses were performed.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors on the effect estimates.

Restricting the analysis to published studies.

Restricting the analysis taking account of risk of bias, as specified above.

Restricting the analysis to very long or large studies in order to establish how much they dominated the results.

Restricting the analysis to studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), country.

We planned to test the robustness of the results by repeating the analysis using different measures of effect estimates (relative risk, odds ratio etc.) and different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models).

Results

Description of studies

For details see Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

Our search identified a total of 3281 references. We excluded 2477 references because they were on a different topic, 42 were conducted on healthy volunteers or animals and 381 were not randomised controlled trials. A further 198 studies were excluded as they used non‐clinical outcomes, eight used intravenous medications and 91 used non‐eligible populations, controls or interventions. The remaining 84 abstracts were reviewed for duplication and 29 separate trials were identified. We obtained full text papers for these 29 trials. Of these, 20 were excluded (11 because the follow‐up was less than 12 months, five did not have eligible controls, two did not collect information about diabetes status, one was observational and one excluded patients on insulin). One ongoing trial was identified (SPS3 2011) leaving eight included studies. There were 35 references identified in the search referring to these eight included studies. For details please see Figure 1.

Included studies

We identified a total of eight completed randomised trials which met the inclusion criteria (AAASPS 2003; CAPRIE 1996; CATS 1988; CHARISMA 2002; CURE 1998; Park 2010; PRoFESS 2008; TASS 1989). The oldest study was completed in 1988 (CATS 1988) and the most recent study was completed in 2010 (Park 2010). A total of 21,379 patients with diabetes participated in the eight studies. The mean duration of follow‐up was 913 days (range 365 days to 2373 days).

Three of the included studies investigated ticlopidine (AAASPS 2003; CATS 1988; TASS 1989). Ticlopidine was compared to aspirin in two trials: AAASPS 2003 which included African American participants with a recent history of stroke, and TASS 1989 which included patients with a neurological deficit. The third study (CATS 1988) compared ticlopidine to placebo in patients with a thromboembolic stroke.

Five included studies investigated clopidogrel. One study compared clopidogrel to aspirin in 3866 diabetes patients with ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction or peripheral arterial disease (CAPRIE 1996). The PRoFESS 2008 study compared clopidogrel to aspirin and dipyridamole in 20,332 patients with ischaemic stroke, of which 5473 patients had diabetes. The remaining three studies compared clopidogrel and aspirin to aspirin alone in a total of 10,099 patients with diabetes; of whom 6555 patients had multiple risk factors for coronary artery disease (CHARISMA 2002), 2840 patients had unstable angina (CURE 1998) and 704 patients had undergone insertion of drug eluding stents 12 months prior (Park 2010).

All trials investigating clopidogrel used a dose of 75 mg daily and all ticlopidine trials used a dose of 250 mg twice daily. The dose of aspirin ranged from 75 mg daily to 650 mg twice daily. All trials recorded all‐cause mortality, vascular mortality, myocardial infarction and stroke except two (Park 2010; PRoFESS 2008). Only three trials contributed to the main primary outcome as diabetes data were not available for the other five trials. See Characteristics of included studies for details of each trial.

The CAPRIE 1996 trial classified patients as having diabetes if defined as such by the investigator. No other studies provided information on how the diagnosis of diabetes was made for patients classified with diabetes.

Excluded studies

The full text of 21 potential studies was reviewed and excluded from this study. Further information is available in Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias assessment is demonstrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

All included studies used and reported an appropriate method of randomisation, most commonly computer generated randomisation.

Allocation

Seven of the eight trials used and reported appropriate methods of allocation concealment. Park 2010 was an open label trial with study participants and investigators aware of the treatment assignments.

Blinding

All of the included trials were double‐blinded, except for the Park 2010 trial in which patients were asked at every visit which medication they were taking. Outcomes were assessed as per standard criteria; however, the assessors knew which medication patients were taking and thus outcome assessment was not blinded either.

Incomplete outcome data

The number of participants lost to follow‐up in the CHARISMA trial was not reported (CHARISMA 2002). All other trials reported their loss to follow‐up rate. There was a similar withdrawal rate ‐ approximately 20% ‐ in three trials (AAASPS 2003; CAPRIE 1996; CHARISMA 2002). The withdrawal rate of Park 2010 was not clearly reported, although it appeared to be over half of the patients. The withdrawal rate in CURE 1998 was also very high (approximately 45%).

Selective reporting

The five most recent trials have available published protocols or registered trial documents. The oldest three trials (CAPRIE 1996; CATS 1988; TASS 1989), do not have previously published protocols with outcomes and so risk of selective reporting is unknown.

Other potential sources of bias

All trials except Park 2010 received funding from the pharmaceutical companies who developed and sold adenosine‐diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists. The role of the pharmaceutical funding for the AAASPS 2003 trial was reported to be limited to supplying medications only.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Unpublished data were sought from all trials, however, additional unpublished information was only provided by the CATS trial. The results presented are derived from data extracted from three trials (CATS 1988; PRoFESS 2008; TASS 1989) including unpublished data provided for the CATS trial. No specific data on patients with diabetes were available for any of the other trials. For details see Appendix 3.

Primary outcomes

Mortality

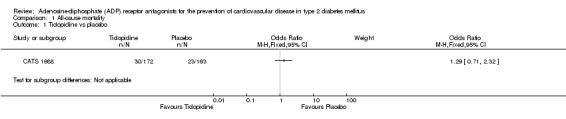

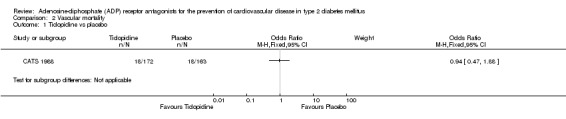

All‐cause mortality and vascular mortality data were only available for one trial (CATS 1988). This trial included 335 patients with diabetes (1.5% of the total diabetes participants included in this review). In this trial, when compared to placebo, ticlopidine was noted to have no significant effect on all‐cause mortality (30/172 (17.4%) versus 23/163 (14.1%); OR 1.29 (95% CI 0.71 to 2.32) (Analysis 1.1) or vascular mortality (18/172 (10.5%) versus 18/163 (11%); OR 0.94 (95% CI 0.47 to 1.88) (Analysis 2.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All‐cause mortality, Outcome 1 Ticlopidine vs placebo.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vascular mortality, Outcome 1 Ticlopidine vs placebo.

Cardiovascular events

Fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction

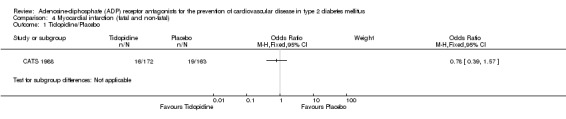

Data for combined fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction were only available for one trial (CATS 1988). Ticlopidine was not noted to have any statistically significant effect on reducing this outcome when compared to placebo (16/172 (9.3%) versus 19/163 (11.7%); OR 0.78 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.57) (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Myocardial infarction (fatal and non‐ fatal), Outcome 1 Ticlopidine/Placebo.

Fatal and non‐fatal stroke

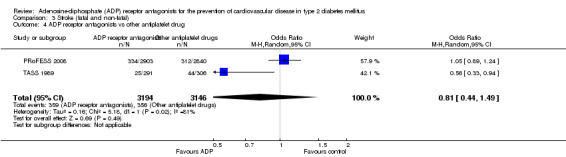

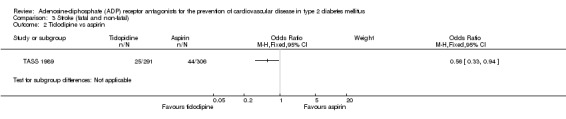

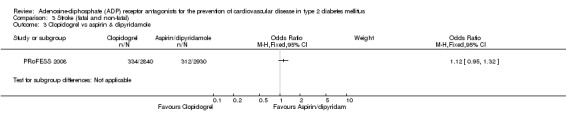

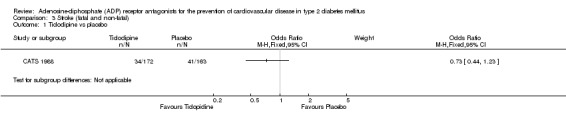

Data for the outcome fatal or non‐fatal stroke were available from two trials (30% of the total diabetes participants), comparing ADP receptor antagonists with other antiplatelet drugs (PRoFESS 2008; TASS 1989). These two trials were statistically heterogeneous (I2 = 81%) and a random‐effects model was used for pooling. Overall, in the pooled analysis there was no statistically significant reduction in the combination of fatal and non‐fatal stroke ((359/3194 (11.2%) versus 356/3146 (11.3%); OR 0.81 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.49)) for ADP receptor antagonists versus other antiplatelet drugs (Analysis 3.4). In the study comparing ticlopidine with aspirin (TASS 1989) a reduction in fatal and non‐fatal stroke was demonstrated with the use of ticlopidine (25/291 (0.9%) versus 44/306 (0.14%) for aspirin; OR 0.56 (95% CI 0.33 to 0.94) (Analysis 3.2). There was no significant reduction in fatal and non‐fatal strokes in diabetes patients when clopidogrel was compared to aspirin combined with dipyramidole (334/2840 (0.12%) versus 312/2903 (0.11%); OR 1.12 (95% CI 0.05 to 1.32)) (PRoFESS 2008; Analysis 3.3).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal), Outcome 4 ADP receptor antagonists vs other antiplatelet drug.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal), Outcome 2 Ticlodipine vs aspirin.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal), Outcome 3 Clopidogrel vs aspirin & dipyridamole.

Peripheral vascular disease

No data were available from any of the trials on the reduction of peripheral vascular disease.

Secondary outcomes

Published or unpublished data on safety and adverse events, health‐related quality of life specifically for patients with diabetes and costs were not available for any of the trials.

Discussion

This systematic review summarises the available data from eight eligible studies on the effect of adenosine‐diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists on mortality and cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes.

Summary of main results

Available data did not demonstrate a significant benefit of ADP receptor antagonists over placebo or other antiplatelet drugs in reducing all‐cause mortality, vascular mortality, stroke or myocardial infarction. Ticlopidine was demonstrated to reduce combined fatal and non‐fatal strokes when compared to aspirin in one trial (Analysis 3.2).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

For most studies, data for patients with diabetes were incomplete. Although eight trials comparing ADP receptor antagonists with other antiplatelet drugs or placebo were eligible for inclusion, only three provided data on patients with diabetes (CATS 1988; PRoFESS 2008; TASS 1989) and only one CATS 1988 provided data on more than one outcome for patients with diabetes. Authors of all eight trials were contacted, one author provided information (CATS 1988), the author of one study declined to provide information (AAASPS 2003), one author did not have any further data (PRoFESS 2008) and the authors of the five remaining studies did not respond to two requests (CAPRIE 1996; CHARISMA 2002; CURE 1998; Park 2010; TASS 1989).

All trials reported on safety and adverse outcomes for all included patients; however, none of the trials reported on adverse outcomes for patients with diabetes separately. For all patients, all four trials comparing ADP receptor antagonists with aspirin noted slightly lower bleeding rates for clopidogrel and ticlopidine compared to aspirin or aspirin and dipyridamole in combination (AAASPS 2003; CAPRIE 1996; PRoFESS 2008; TASS 1989). However, these trials used higher doses of aspirin than are commonly prescribed today. The trial comparing ticlopidine to placebo noted one serious bleeding event in the placebo group compared with two serious bleeding events in the ticlopidine group (CATS 1988). The three trials which compared dual aspirin and clopidogrel therapy to aspirin alone all noted increased bleeding risk with dual therapy (CHARISMA 2002; CURE 1998; Park 2010). A Cochrane review comparing dual therapy of clopidogrel and aspirin to aspirin alone noted there would be an additional six major bleeds per 1000 people treated (Squizzato 2011).

None of the included trials reviewed peripheral vascular disease as a cardiovascular endpoint. No trial used standard diagnostic criteria to diagnose diabetes and none of the trials separated patients into type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

There are no trials specifically designed to look at the efficacy and safety of ADP receptor antagonists for patients with type 2 diabetes. Patients with diabetes have different metabolism and platelet function to patients without diabetes which predisposes them to cardiovascular disease (Angiolillo 2009) and this may change the efficacy and safety of ADP receptor antagonists.

The use of ADP receptor antagonists in diabetes patients is based on evidence for their use from the analysis of patients with and without diabetes. Many major guidelines now recommend the use of clopidogrel in certain situations. For example, the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines recommend clopidogrel for 12 months in all patients with unstable angina or non‐ST elevated myocardial infarction with a six month mortality risk of greater than 1.5% (NICE 2010), based on the CURE trial findings. As a result, many patients with diabetes are being prescribed ADP receptor antagonists and newer ADP receptor antagonists are now compared to clopidogrel rather than to other antiplatelet agents despite there being limited evidence for patients with diabetes.

The intention of this review was to assess the use of ADP receptor antagonists in primary and secondary prevention. However, all of the trials except one (CHARISMA 2002) enrolled patients who had previous cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events. ADP receptor antagonists in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in high risk vascular patients was investigated by the CHARISMA trial, however, outcome data for patients with diabetes were unavailable from this trial.

Quality of the evidence

Overall the methodological quality of the eight included trials was high. All of the trials except one (Park 2010) were double‐blind. The majority of the studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies.

Most studies reported composite end points as well as individual outcome events. A specific analysis of diabetes patients of the CAPRIE 1996 trial only reported a composite end point of vascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke and rehospitalisation for bleeding or ischaemia (Bhatt 2002). From a clinical perspective, reporting of composite endpoints is less useful as clinicians are unable to provide relevant information to patients, for example, the patient's risk of death.

Potential biases in the review process

It is possible that we have missed trials through the search strategy despite three databases being searched and relevant review articles being handsearched. Of the included trials, unpublished diabetes‐specific data were provided by only one trial and this may have introduced bias into the review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The largest meta‐analysis of antiplatelet therapy versus control was done by the Antithrombotic Trialists Collaboration (Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration 2002). This meta‐analysis reviewed all antiplatelet agents including aspirin and failed to show a statistically significant reduction in risk of serious vascular events in patients with diabetes.

There are two Cochrane reviews on ADP receptor antagonists which differ from our review as they are not limited to patients with diabetes. One review included all patients with previous clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis of the cerebral, coronary or peripheral circulation and assessed the composite end point of stroke, myocardial infarction or vascular death. This review noted that ADP receptor antagonists modestly reduced the odds of a serious vascular event when compared to aspirin. The result just reached statistical significance (11.6% versus 12.5%, OR 0.92 (0.85 to 0.99)) and the authors concluded that ADP receptor antagonists were at least as effective as aspirin, possibly more so (Sudlow 2009). A different Cochrane review of clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone included all patients with known cardiovascular disease or at high risk of atherothrombotic disease. The authors concluded that in patients with acute non‐ST coronary syndromes the benefits of clopidogrel plus aspirin outweighed the harms (Squizzato 2011).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The role of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists in patients with diabetes is unclear. The use of ADP receptors for prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes needs to be guided by evidence available from analysis done on all patients, including those with and without diabetes. Current available evidence analysed in previous Cochrane reviews suggests ADP receptor antagonists were at least as effective as aspirin, possibly more so in preventing cardiovascular disease in secondary prevention (Sudlow 2009) and that in acute non‐ST coronary syndromes the benefits of clopidogrel and aspirin outweighed the harms (Squizzato 2011). Another factor to take into account is the cost of ADP receptor antagonists which in many countries is significantly higher than aspirin.

Implications for research.

All future trials should separately report outcome data for patients with diabetes to allow for development of clinical guidelines for this specific patient population. Any previously conducted trial should make diabetes specific data available for analysis regardless of outcomes. Improved identification and thorough analysis of subgroups of diabetes patients in large primary and secondary prevention trials would provide a more solid evidence base for recommendations for primary and secondary prevention in diabetes patients.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2005 Review first published: Issue 11, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 May 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sarah Thorning for her assistance with the search strategy and finding the full text for some of the trials.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Search terms and databases |

| Unless otherwise stated, search terms are free text terms. Abbreviations: '$': stands for any character; '?': substitutes one or no character; adj: adjacent (i.e. number of words within range of search term); exp: exploded MeSH; MeSH: medical subject heading (MEDLINE medical index term); pt: publication type; sh: MeSH; tw: text word. |

| The Cochrane Library |

| #1 MeSH descriptor Diabetes mellitus, type 2 explode all trees #2 (obes* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #3 (MODY in All Text or NIDDM in All Text or TDM2 in All Text or TD2 in All Text) #4 ( (non in All Text and insulin* in All Text and depend* in All Text) or (noninsulin* in All Text and depend* in All Text) or (non in All Text and insulindepend* in All Text) or noninsulindepend* in All Text) #5 (typ? in All Text and (2 in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #6 (typ? in All Text and (II in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #7 (non in All Text and (keto* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #8 (nonketo* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #9 (adult* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #10 (matur* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #11 (late in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #12 (slow in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #13 (stabl* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #14 (insulin* in All Text and (defic* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #15 (plurimetabolic in All Text and syndrom* in All Text) #16 (pluri in All Text and metabolic in All Text and syndrom* in All Text) #17 (typ?2 in All Text near/3 diabet* in All Text) #18 (keto in All Text and (resist* in All Text near/3 diabet* in All Text) ) #19 (non in All Text and (keto* in All Text near/3 diabet* in All Text) ) #20 (nonketo* in All Text near/3 diabet* in All Text) #21 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20) #22 MeSH descriptor Ticlopidine explode all trees #23 (ticlopidin* in All Text or clopidogrel in All Text or prasugrel in All Text or ticagrelor in All Text) #24 (ticlodone in All Text or ticlodix in All Text or ticlid in All Text) #25 (#22 or #23 or #24) #26 (#21 and #25) |

| Medline |

| 1 exp Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/ 2 exp Insulin Resistance/ 3 exp Glucose Intolerance/ 4 exp Metabolic Syndrome X/ 5 (impaired glucos$ toleranc$ or glucos$ intoleranc$ or insulin resistan$).tw,ot. 6 (obes$ adj3 diabet$).tw,ot. 7 (MODY or NIDDM or T2DM or T2D).tw,ot. 8 (non insulin$ depend$ or noninsulin$ depend$ or noninsulin?depend$ or non insulin?depend$).tw,ot. 9 ((typ? 2 or typ? II or typ?2 or typ?II) adj3 diabet$).tw,ot. 10 ((keto?resist$ or non?keto$) adj6 diabet$).tw,ot. 11 (((late or adult$ or matur$ or slow or stabl$) adj3 onset) and diabet$).tw,ot. 12 metabolic syndrom*.tw,ot. 13 or/1‐12 14 exp Diabetes Insipidus/ 15 diabet$ insipidus.tw,ot. 16 14 or 15 17 13 not 16 18 exp Ticlopidine/ 19 (ticlopidin* or clopidogrel or prasugrel).tw,ot. 20 (ADP adj3 receptor antagonist*).tw,ot. 21 (ticlodone or ticlodix or ticlid).tw,ot. 22 or/18‐21 23 17 and 22 24 randomized controlled trial.pt. 25 controlled clinical trial.pt. 26 randomi?ed.ab. 27 placebo.ab. 28 drug therapy.fs. 29 randomly.ab. 30 trial.ab. 31 groups.ab. 32 or/24‐31 33 Meta‐analysis.pt. 34 exp Technology Assessment, Biomedical/ 35 exp Meta‐analysis/ 36 exp Meta‐analysis as topic/ 37 hta.tw,ot. 38 (health technology adj6 assessment$).tw,ot. 39 (meta analy$ or metaanaly$ or meta?analy$).tw,ot. 40 ((review$ or search$) adj10 (literature$ or medical database$ or medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane or cinahl or psycinfo or psyclit or healthstar or biosis or current content$ or systemat$)).tw,ot. 41 or/33‐40 42 32 or 41 43 (comment or editorial or historical‐article).pt. 44 42 not 43 45 23 and 44 |

| Embase |

| 1 exp Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/ 2 exp Insulin Resistance/ 3 (MODY or NIDDM or T2D or T2DM).tw,ot. 4 ((typ? 2 or typ? II or typ?II or typ?2) adj3 diabet*).tw,ot. 5 (obes* adj3 diabet*).tw,ot. 6 (non insulin* depend* or non insulin?depend* or noninsulin* depend* or noninsulin?depend*).tw,ot. 7 ((keto?resist* or non?keto*) adj3 diabet*).tw,ot. 8 ((adult* or matur* or late or slow or stabl*) adj3 diabet*).tw,ot. 9 (insulin* defic* adj3 relativ*).tw,ot. 10 (insulin* resistanc* or impaired glucos* toleranc* or glucos* intoleranc*).tw,ot. 11 or/1‐10 12 exp Diabetes Insipidus/ 13 diabet* insipidus.tw,ot. 14 12 or 13 15 11 not 14 16 exp ticlopidine/ 17 exp clopidogrel/ 18 exp prasugrel/ 19 exp ticagrelor/ 20 (ADP adj3 receptor antagonist*).tw,ot. 21 (ticlopidin* or clopidogrel or prasugrel or ticagrelor).tw,ot. 22 (ticlodone or ticlodix or ticlid).tw,ot. 23 or/16‐22 24 15 and 23 25 exp Randomized Controlled Trial/ 26 exp Controlled Clinical Trial/ 27 exp Clinical Trial/ 28 exp Comparative Study/ 29 exp Drug comparison/ 30 exp Randomization/ 31 exp Crossover procedure/ 32 exp Double blind procedure/ 33 exp Single blind procedure/ 34 exp Placebo/ 35 exp Prospective Study/ 36 ((clinical or control$ or comparativ$ or placebo$ or prospectiv$ or randomi?ed) adj3 (trial$ or stud$)).ab,ti. 37 (random$ adj6 (allocat$ or assign$ or basis or order$)).ab,ti. 38 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj6 (blind$ or mask$)).ab,ti. 39 (cross over or crossover).ab,ti. 40 or/25‐39 41 exp meta analysis/ 42 (metaanaly$ or meta analy$ or meta?analy$).ab,ti,ot. 43 ((review$ or search$) adj10 (literature$ or medical database$ or medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane or cinahl or psycinfo or psyclit or healthstar or biosis or current content$ or systematic$)).ab,ti,ot. 44 exp Literature/ 45 exp Biomedical Technology Assessment/ 46 hta.tw,ot. 47 (health technology adj6 assessment$).tw,ot. 48 or/41‐47 49 40 or 48 50 (comment or editorial or historical‐article).pt. 51 49 not 50 52 24 and 51 53 review.pt. 54 52 not 53 |

Appendix 2. Baseline characteristics

|

Study ID Characteristic |

AAASPS | CAPRIE | CATS | CHARISMA | CURE | Park | PRoFESS | TASS |

| Intervention(s) and control(s) | I: Ticlopidine 250 mg bd C: Aspirin 325 mg bd |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily C: Aspirin 325 mg daily |

I: Ticlopidine 250 mg bd C: Placebo |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily C: Aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 to 300 mg daily C: Aspirin 75 to 300 mg daily |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 100 to 200 mg daily C(d): Aspirin 100 to 200 mg daily |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily C: Aspirin / dipyridamole 25 mg / 200 mg bd |

I: Ticlopidine 250 mg bd C: Aspirin 650 mg bd |

| Participating population | Patients with cerebral infarcts | Patients with vascular disease | Patients with thrombo‐embolic strokes | High‐risk vascular patients | Patients with acute coronary syndrome | Patients with drug eluding stents | Patients with ischaemic strokes | Patients with ischaemic neurological events |

| Country | USA | 16 countries | USA, Canada | 32 countries | 28 countries | South Korea | 35 countries | USA, Canada |

| Setting | Hospital and community | Hospital and community | Hospital inpatients | Hospital | Hospital | Inpatients and community | Hospital and community | Hospital and community |

| Sex [female%] | I: 54.5 C: 52.4 |

I: 28 C: 28 |

I: 40 C: 37 |

I: 29.7 C: 29.8 |

I: 38.7 C: 38.3 |

I: 30.0 C: 30.6 |

I: 36.0 C: 35.9 |

I: 36 C: 35 |

| Age [mean years (SD)] | I: 60.9 (10.7) C: 61.6 (10.4) |

I: 62.5 (11.1) C: 62.5 (11.1) |

I: 66 C: 65 |

Median I: 64.0 C: 64.0 |

I: 64.2 (11.3) C: 64.2 (11.3) |

I: 62 (9.8) C: 61.9 (9.9) |

I: 66.2 (8.5) C: 66.1 (8.6) |

I: 62.7 (9.4) C: 63.2 (9.3) |

| HbA1c [mean % (SD)] | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| BMI [mean kg/m2 (SD)] | I: 29.9 (7.1) C: 30.0 (6.8) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | I: 26.8 (5.0) C: 26.8 (5.0) |

‐ |

| Ethnic groups [%] | I: African American C: African American |

‐ | Caucasian I: 73% C: 71% |

White I: 80.4% C: 79.9% |

‐ | ‐ | White / European I: 57.3% C: 57.7% |

White I: 80% C: 81% |

| Duration of follow‐up (mean) | I: 710 days C: 716 days |

I: 1.91 years C: 1.91 years |

I: 17 months C: 19 months |

Median I: 28 months C: 28 months |

I: 12 months C: 12 months |

I: 19.2 months C: 19.2 months |

I: 2.5 years C: 2.5 years |

I: 778 days C: 858 days |

|

Footnotes "‐" denotes not reported Abbreviations: bd: twice daily; BMI: body mass index; C: control; C(d): intervention (diabetes patients); C(t): intervention (all patients); HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin A1c; I: intervention; I(d): intervention (diabetes patients); I(t): intervention (all patients); SD: standard deviation | ||||||||

Appendix 3. Study outcomes

|

Study ID Characteristic |

AAASPS | CAPRIE | CATS | CHARISMA | CURE | Park | PRoFESS | TASS |

| Intervention(s) and control(s) | I: Ticlopidine 250 mg bd C: Aspirin 325 mg bd |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily C: Aspirin 325 mg daily |

I: Ticlopidine 250 mg bd C: Placebo |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily C: Aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 to 300 mg daily C: Aspirin 75 to 300 mg daily |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 100 to 200 mg daily C(d): Aspirin 100 to 200 mg daily |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily C: Aspirin / dipyridamole 25 mg / 200 mg bd |

I: Ticlopidine 250 mg bd C: Aspirin 650 mg bd |

| All‐cause mortality | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 45 C(t): 40 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 560 C(t): 571 |

I(d): 30 C(d): 23 I(t): 66 C(t): 65 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 371 C(t): 374 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 359 C(t): 390 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 20 C(t): 13 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 756 C(t): 739 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 175 C(t): 196 |

| Vascular mortality | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 18 C(t): 18 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 350 C(t): 378 |

I(d): 18 C(d): 18 I(t): 35 C(t): 43 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 238 C(t): 229 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 318 C(t): 345 |

‐ | ‐ | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 120 C(t): 116 |

| Myocardial infarction (fatal) | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 1 C(t): 0 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 53 C(t): 75 |

I(d): 13 C(d): 10 I(t): 21 C(t): 22 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 21 C(t): 14 |

| Myocardial infarction (non‐fatal) | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 8 C(t): 8 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 255 C(t): 301 |

I(d): 3 C(d): 9 I(t): 11 C(t): 15 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 146 C(t): 155 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Myocardial infarction (fatal and non‐fatal) | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 9 C(t): 8 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 308 C(t): 376 |

I(d): 16 C(d): 19 I(t): 32 C(t): 37 |

‐ | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 324 C(t): 419 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 10 C(t): 7 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 197 C(t): 178 |

‐ |

| Stroke (fatal) | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 4 C(t): 2 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 37 C(t): 42 |

I(d): 6 C(d): 9 I(t): 14 C(t): 17 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 16 C(t): 23 |

| Stroke (non‐fatal) | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 102 C(t): 84 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 472 C(t): 504 |

I(d): 28 C(d): 32 I(t): 67 C(t): 86 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 150 C(t): 189 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 156 C(t): 189 |

| Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal) | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 106 C(t): 86 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 509 C(t): 546 |

I(d): 34 C(d): 41 I(t): 81 C(t): 103 |

‐ | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 75 C(t): 87 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 9 C(t): 4 |

I(d): 334 C(d): 312 I(t): 862 C(t): 879 |

I(d): 25 C(d): 44 I(t): 172 C(t): 212 |

|

Footnotes "‐" denotes not reported Abbreviations: bd: twice daily; C: control; C(d): intervention (diabetes patients); C(t): intervention (all patients); I: intervention; I(d): intervention (diabetes patients); I(t): intervention (all patients) | ||||||||

Appendix 4. Adverse events

|

Study ID Characteristic |

AAASPS | CAPRIE | CATS | CHARISMA | CURE | Park | PRoFESS | TASS |

| Intervention(s) and control(s) | I: Ticlopidine 250 mg bd C: Aspirin 325 mg bd |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily C: Aspirin 325 mg daily |

I: Ticlopidine 250 mg bd C: Placebo |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily C: Aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 to 300 mg daily C: Aspirin 75 to 300 mg daily |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 100 to 200 mg daily C(d): Aspirin 100 to 200 mg daily |

I: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily C: Aspirin / dipyridamole 25 mg / 200 mg bd |

I: Ticlopidine 250 mg bd C: Aspirin 650 mg bd |

| Serious adverse events (including bleeding) | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 270 C(t): 262 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 360 C(t): 409 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 43 C(t): 15 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 373 C(t): 426 |

‐ |

| Serious bleeding | I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 10 C(t): 19 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 77 C(t): 109 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 2 C(t): 1 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 130 C(t): 104 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 231 C(t): 169 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 3 C(t): 1 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 116 C(t): 128 |

I(d): ‐ C(d): ‐ I(t): 137 C(t): 152 |

|

Footnotes "‐" denotes not reported Abbreviations: bd: twice daily; C: control; C(d): intervention (diabetes patients); C(t): intervention (all patients); I: intervention; I(d): intervention (diabetes patients); I(t): intervention (all patients) | ||||||||

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. All‐cause mortality.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ticlopidine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Comparison 2. Vascular mortality.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ticlopidine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Comparison 3. Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ticlodipine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Ticlodipine vs aspirin | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 Clopidogrel vs aspirin & dipyridamole | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4 ADP receptor antagonists vs other antiplatelet drug | 2 | 6340 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.44, 1.49] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal), Outcome 1 Ticlodipine vs placebo.

Comparison 4. Myocardial infarction (fatal and non‐ fatal).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ticlopidine/Placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

AAASPS 2003.

| Methods | RANDOMISED CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL, RANDOMISATION RATIO: 1:1, EQUIVALENCE DESIGN | |

| Participants |

INCLUSION CRITERIA: African American 29 to 85 years of age Non‐cardioembolic cerebral infarct Cerebral infarct 7 to 90 days prior CT or MRI consistent with occurrence of entry cerebral infarct (shows entry infarct, old infarct, or no infarct) Measurable neurological deficit that correlates with onset of entry cerebral infarct Able to follow an outpatient treatment program EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Transient ischaemic attack Subarachnoid haemorrhage Cardiac embolism Iatrogenic stroke Postoperative stroke within 30 days of operation Carotid endarterectomy as preventive treatment of entry cerebral infarct Mean arterial blood pressure > 130 mm Hg on 3 consecutive days Modified Barthel Index < 10 History of dementia or neurodegenerative disease Severe comorbid condition such as cancer that would limit survival during 2‐year follow‐up period Concurrent enrolment in another clinical trial Sensitivity or allergy to aspirin or ticlopidine Women of childbearing potential Peptic ulcer disease, active bleeding diathesis, lower gastrointestinal bleeding, platelet or other haematologic abnormality clinically active in the past year Haematuria Positive stool guaiac Prolonged prothrombin time or partial thromboplastin time Blood urea nitrogen > 40 mg %, Serum creatinine > 2.0 mg % Thrombocytopenia or neutropenia as defined by the lower limit of normal for the platelet count or white blood cell count ≥ 2 times the upper range of normal on liver function tests PARTICIPANTS: Total participants: 1809 (Aspirin: 907, Ticlodipine: 902) Diabetes participants: 738 (Aspirin: 379, Ticlodipine: 359) Total participants withdrawn or prematurely discontinuing study medication: 454 (Aspirin: 215, Ticlodipine: 239) Total participants lost to follow‐up: 68 (Aspirin: 31, Ticlodipine: 37) |

|

| Interventions |

INTERVENTION: Ticlopidine 250 mg twice daily and placebo CONTROL: Aspirin 325 mg twice daily and placebo NUMBER OF STUDY CENTRES: 62 COUNTRY/ LOCATION: United States of America SETTING: Hospital and community |

|

| Outcomes |

OUTCOMES(as documented in the published protocol): Composite endpoint of myocardial infarction, recurrent stroke and vascular death All cause mortality patients with diabetes: unknown All cause mortality all patients: Aspirin: 40, Ticlopidine: 45 Vascular mortality patients with diabetes: unknown Vascular mortality all patients: Aspirin:18, Ticlopidine: 18 Myocardial infarction patients with diabetes (fatal): unknown Myocardial infarction patients with diabetes (non‐fatal): unknown Myocardial infarction all patients (fatal): Aspirin: 0, Ticlopidine: 1 Myocardial infarction all patients (non‐fatal): Aspirin: 8, Ticlopidine: 8 Stroke patients with diabetes (fatal): unknown Stroke patients with diabetes (non‐fatal): unknown Stroke all patients (fatal): Aspirin: 2, Ticlopidine: 4 Stroke all patients (non‐fatal): Aspirin: 84, Ticlopidine: 102 Serious adverse event patients with diabetes: unknown Serious adverse event all patients: Aspirin: 262, Ticlopidine: 270 |

|

| Study details |

RUN‐IN PERIOD: None STUDY TERMINATED BEFORE REGULAR END: Yes ‐ at 6.5 years |

|

| Publication details |

LANGUAGE OF PUBLICATION: English COMMERCIAL FUNDING PUBLICATION STATUS: PEER REVIEW JOURNAL |

|

| Stated aim of study | "the primary hypothesis of this ... trial ... is that ticlopidine hydrochloride is more effective than aspirin in preventing the composite endpoints of recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and vascular death among middle‐aged and elderly African Americans with non‐cardioembolic ischemic stroke" | |

| Notes | Supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Medications and placebos were supplied by Roche Laboratories and Bayer Abbreviations: CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomisation algorithm developed by chief study statistician" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Local site personnel call the Automated Phone Registration System for AAASPS operated by the Moffitt Cancer Research Institute of the University of South Florida ... for allocation" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "all study personnel were masked (blinded) from treatment assignment with the exception of 1 study statistician who developed the randomization algorithm" "placebo tablets had identical physical properties" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 276 participants withdrew in the Ticlopidine group and 246 in the Aspirin group. Analysis was done on intention‐to‐treat basis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Outcomes reported as stated in the published protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | "Roche Laboratories and Bayer had no role beyond supplying study medications and placebos." |

CAPRIE 1996.

| Methods | RANDOMISED CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL, RANDOMISATION RATIO: 1:1, EQUIVALENCE DESIGN | |

| Participants |

INCLUSION CRITERIA: Ischaemic stroke: (including retinal and lacunar infarction) ≥ 1 week and ≤ 6 months and neurological signs persisting ≥ 1 week from stroke onset and CT or MRI ruling out haemorrhage or non‐relevant disease MI: Onset ≤ 35 days before randomisation and two of: Characteristic ischaemic pain for ≥ 20 min Elevation of CK, CK‐MB, LDH, or AST to 2 times upper limit of laboratory normal with no other explanation Development of new ≥ 40 Q waves in at least two adjacent ECG leads or new dominant R wave in V1 (R ≥ 1 mm > S in V1) Atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease: Intermittent claudication (WHO: leg pain on walking, disappearing in < 10 min on standing) of presumed atherosclerotic origin; and ankle/arm systolic BP ratio ≤ 0·85 in either leg at rest (two assessments on separate days); or history of intermittent claudication with previous leg amputation, reconstructive surgery, or angioplasty with no persisting complications from intervention EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Age < 21 years Severe cerebral deficit likely to lead to patient being bedridden or demented Carotid endarterectomy after qualifying stroke Qualifying stroke induced by carotid endarterectomy or angiography Patient unlikely to be discharged alive after qualifying event Severe comorbidity likely to limit patient's life expectancy to less than 3 years Uncontrolled hypertension Scheduled for major surgery Contraindications to study drugs Severe renal or hepatic insufficiency Haemostatic disorder or systemic bleeding History of haemostatic disorder or systemic bleeding History of thrombocytopenia or neutropenia History of drug‐induced haematologic or hepatic abnormalities Known to have abnormal WBC, differential, or platelet count Anticipated requirement for long‐term anticoagulants, non‐study antiplatelet drugs or NSAIDs affecting platelet function History of aspirin sensitivity Women of childbearing age not using reliable contraception Currently receiving investigation drug Previously entered in other clopidogrel studies Geographic or other factors making study participation impractical CO‐MEDICATIONS: Antiplatelet or anticoagulation drugs were discontinued before randomisation. Patients with anticipated need for long term anticoagulation or NSAIDs were excluded. Concomitant medications were recorded. PARTICIPANTS: Total participants: 19,185 (Aspirin: 9546, Clopidogrel: 9553) [86 did not receive medication, Aspirin 40, Clopidogrel 46] Diabetes participants: 3866 (Aspirin: 20% of total group, Clopidogrel: 20% of total group) Total participants withdrawn or prematurely discontinuing study medication: 4059 (Aspirin: 21.1%, Clopidogrel: 21.3%) Total participants lost to follow‐up: 42 (Aspirin: 20, Clopidogrel: 22) |

|

| Interventions |

INTERVENTION: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and placebo CONTROL: Aspirin 325 mg daily and placebo NUMBER OF STUDY CENTRES: 384 centres COUNTRY/ LOCATION: 16 countries SETTING: Hospital and community |

|

| Outcomes |

OUTCOMES (as stated in the publication): Non‐fatal Ischaemic Stroke: acute neurological event with focal signs for ≥ 24 hrs; if new location without evidence of intracranial haemorrhage; if worsening of previous event, must have lasted > 1 week, or more than 24 hrs if accompanied by appropriate CT or MRI findings Non‐fatal MI: same as inclusion criteria Non‐fatal primary intracranial haemorrhage: Intracerebral haemorrhage (including intracranial and subarachnoid), and subdural haematoma documented by appropriate neuroimaging investigations. Non‐fatal leg amputation: Only if above the ankle and not done for trauma or cancer. Fatal events: Ischaemic stroke (within 28 days of onset of symptoms/signs), MI (within 28 days of onset of symptoms signs), haemorrhage, other vascular causes (deaths that were not clearly non‐vascular and did not meet other criteria) or non‐vascular causes All cause mortality patients with diabetes: unknown All cause mortality all patients: Aspirin: 571, Clopidogrel: 560 Vascular mortality patients with diabetes: unknown Vascular mortality all patients: Aspirin: 378, Clopidogrel: 350 Myocardial infarction patients with diabetes (fatal): unknown Myocardial infarction patients with diabetes (non‐fatal): unknown Myocardial infarction all patients (fatal): Aspirin: 75, Clopidogrel: 53 Myocardial infarction all patients (non‐fatal): Aspirin: 301, Clopidogrel: 255 Stroke patients with diabetes (fatal): unknown Stroke patients with diabetes (non‐fatal): unknown Stroke all patients (fatal): Aspirin: 42, Clopidogrel: 37 Stroke all patients (non‐fatal): Aspirin: 504, Clopidogrel: 472 Serious adverse event patients with diabetes: unknown Serious adverse event all patients: Aspirin: 409, Clopidogrel: 360 |

|

| Study details |

RUN‐IN PERIOD: No STUDY TERMINATED BEFORE REGULAR END: No (recruitment completed early but follow‐up remained at one year post recruitment completion) |

|

| Publication details |

LANGUAGE OF PUBLICATION: English COMMERCIAL FUNDING PUBLICATION STATUS: PEER REVIEW JOURNAL |

|

| Stated aim of study | “to assess the potential benefit of clopidogrel, compared with aspirin, in reducing the risk of ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or vascular death in patients with recent ischaemic stroke, recent myocardial infarction or peripheral arterial disease” | |

| Notes | This study was funded by Sanofi and Bristol‐Myers Squibb Abbreviations: AST aspartate aminotransferase; BP: blood pressure; CK: creatine kinase; CK‐MB: creatine kinase myocardial band; CT: computed tomography; ECG: electrocardiogram; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; MI: myocardial infarction; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; WBC: white blood cells; WHO: World Health Organisation |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “The Independent Statistical Centre provided computer‐generated .... with random allocation” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “The Independent Statistical Centre provided computer‐generated .... with random allocation” |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "These [Medication] supplies were in the form of blister packs containing either 75 mg tablets of clopidogrel plus aspirin placebo tablets or 325 mg aspirin tablets plus clopidogrel placebo tablets, such blister packs being indistinguishable from one another " |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | “19,185 patients ... were randomised”; “46 patients in clopidogrel group and 40 in aspirin group never took any study drug”; “42 patients lost to follow‐up ... included in the analysis” “4059 patients discontinued study drug early...., 21.3% in clopidogrel and 21.1% in the aspirin group. Reasons for stopping study drug early were similar in the two groups”. Comment: equal loss in both groups, included in analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Registration of trial or prior protocol publication unavailable. Outcomes stated in publication document reported |

| Other bias | High risk | "This study was funded by Sanofi and Bristol‐Myers Squibb" |

CATS 1988.

| Methods | RANDOMISED CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL, RANDOMISATION RATIO: 1:1, EQUIVALENCE DESIGN | |

| Participants |

INCLUSION CRITERIA: Thromboemoblic stroke 1 week to 4 months prior to entry into study Diagnosis based on clinical assessment and history Neurological deficit had to be persistent at time of entry into study CT scan excluded haemorrhagic stroke or other intracerebral pathology EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Cardioembolic strokes (defined as two of AF, sick sinus syndrome, seizure at onset, involvement in more than one vascular territory) Bedridden or dementia Life‐limiting illness Contraindications to ticlopidine (hepatic or renal insufficiency, haemostatic disorder, thrombocytopenia, history of drug‐induced haematologic abnormalities) Significant laboratory test abnormalities Carotid endarterectomy prior to randomisation Stroke due to carotid endarterectomy Long term anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy required History of drug or alcohol abuse Inclusion in another trial PARTICIPANTS: Total participants: 1053 (Ticlodipine: 525, Placebo: 528) Diabetes participants: 335 (Ticlodipine: 172, Placebo: 163) Total participants withdrawn or prematurely discontinuing study medication: 402 (Ticlodipine: 238, Placebo: 164) Total participants lost to follow‐up: 4 (Ticlodipine: 3, Placebo: 1) |

|

| Interventions |

INTERVENTION: Ticlopidine 250 mg twice daily CONTROL: Placebo NUMBER OF STUDY CENTRES: 25 COUNTRY/ LOCATION: USA and Canada SETTING: Hospital inpatient |

|

| Outcomes |

OUTCOMES (as reported in published protocol): Non‐fatal stroke: Diagnosis based on clinical assessment and history Duration of > 24 hours if in new location or > 1 week if worsening of previous deficit unless accompanied by new CT finding CT scan excluded haemorrhagic stroke or other intracerebral pathology Non‐fatal myocardial infarction: At least two of: a) typical symptoms of pain b) compatible ECG changes or positive pyrophosphate radionuclide scan c) appropriate serum enzyme changes (peak value > twice upper limit of normal) Vascular death: New cerebral infarction Myocardial infarction Sudden death Congestive heart failure All cause mortality patients with diabetes: 30 ticlopidine, 23 placebo All cause mortality all patients: 66 ticlopidine, 65 placebo Vascular mortality patients with diabetes with diabetes: 18 ticlopidine, 18 placebo Vascular mortality all patients: 35 ticlopidine, 43 placebo Myocardial infarction patients with diabetes (fatal): 13 ticlopidine, 10 placebo Myocardial infarction patients with diabetes (non‐fatal): 3 ticlopidine, 9 placebo Myocardial infarction all patients (fatal): 21 ticlopidine, 22 placebo Myocardial infarction all patients (non‐fatal): 11 ticlopidine, 15 placebo Stroke patients with diabetes (fatal): 6 ticlopidine, 9 placebo Stroke patients with diabetes (non‐fatal): 28 ticlopidine, 32 placebo Stroke all patients (fatal): 14 ticlopidine, 17 placebo Stroke all patients (non‐fatal): 67 ticlopidine, 86 placebo Serious adverse event patients with diabetes: unknown Serious adverse event all patients: 43 ticlopidine, 15 placebo |

|

| Study details |

RUN‐IN PERIOD: No STUDY TERMINATED BEFORE REGULAR END: No |

|

| Publication details |

LANGUAGE OF PUBLICATION: English COMMERCIAL FUNDING PUBLICATION STATUS: PEER REVIEW JOURNAL |

|

| Stated aim of study | “to assess the effect of ticlopidine (250 mg twice daily) in reducing the rate of subsequent occurrence of stroke, myocardial infarction, or vascular death in patients who have had a recent thromboembolic stroke" | |

| Notes | This study was funded by Syntax Research (USA) Inc and Sanofi, France Abbreviations: AF: atrial fibrillation; CT: computed tomography; ECG: electrocardiogram |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Prescribed randomisation arrangement generated separately for each clinical centre, 528 patients randomised to placebo, 525 to ticlopidine |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Only the safety committee knew the randomisation code for a particular centre |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Ticlopidine was supplied.... in plastic containers .... placebo tablets were identical in packaging and appearance |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 4 patients lost to follow‐up, 3 in ticlopidine group, 1 in placebo group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Registration of trial or prior protocol publication unavailable. Outcomes stated in publication document reported |

| Other bias | High risk | Funded by pharmaceutical company |

CHARISMA 2002.

| Methods | RANDOMISED CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL, RANDOMISATION RATIO: 1:1, EQUIVALENCE DESIGN | |

| Participants |

INCLUSION CRITERIA: High risk primary prevention: 2 major risk factors or 3 minor risk factors or 1 major and 2 minor risk factors. Major risk factors: Diabetes mellitus (on drug therapy) Diabetic neuropathy ABI < 0.9 Asymptomatic carotid stenosis ≥ 70% Carotid plaque evidence by intima‐media thickness Minor risk factors: Systolic BP ≥ 150 mm Hg despite therapy for 3 months Primary hypercholesterolaemia Current smoker > 15 cigarettes per day Male ≥ 65 years, female ≥ 70 years Coronary artery disease: 1 of: Stable angina with document multivessel coronary disease History of multivessel CABG History of multivessel PCI Previous MI Cerebrovascular disease: previous ischaemic stroke or TIA Peripheral arterial disease: intermittent claudication with ABI ≤ 0.85 or intermittent claudication with previous intervention EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Chronic oral antithrombotic medications (warfarin, high dose aspirin, NSAIDs) Requiring prolonged clopidogrel therapy CO‐MEDICATIONS: Concurrent oral antithrombotic therapy not permitted. Other standard therapy at the discretion of clinicians. PARTICIPANTS: Total participants: 15,603 (Clopidogrel: 7802, Placebo: 7801) Diabetes participants: 6556 (Clopidogrel: 3304, Placebo: 3252) Total participants withdrawn or prematurely discontinuing study medication: Clopidogrel: 20.4%, Placebo: 18.2% Total participants lost to follow‐up: unknown |

|

| Interventions |

INTERVENTION: Clopidogrel 75 mg daily and aspirin 75 mg to 162 mg daily CONTROL: Placebo and aspirin 75 mg to 162 mg daily NUMBER OF STUDY CENTRES: 768 COUNTRY/ LOCATION: 32 countries SETTING: Hospital |

|

| Outcomes |