Abstract

Background

Uterine fibroids cause heavy prolonged bleeding, pain, pressure symptoms and subfertility. The traditional method of treatment has been surgery as medical therapies have not proven effective. Uterine artery embolization has been reported to be an effective and safe alternative to treat fibroids in women not desiring future fertility. There is a significant body of evidence that is based on case controlled studies and case reports. This is an update of the review previously published in 2012.

Objectives

To review the benefits and risks of uterine artery embolization (UAE) versus other medical or surgical interventions for symptomatic uterine fibroids.

Search methods

We searched sources including the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE and trial registries. The search was last conducted in April 2014. We contacted authors of eligible randomised controlled trials to request unpublished data.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of UAE versus any medical or surgical therapy for symptomatic uterine fibroids. The primary outcomes of the review were patient satisfaction and live birth rate (among women seeking live birth).

Data collection and analysis

Two of the authors (AS and JKG) independently selected studies, assessed quality and extracted data. Evidence quality was assessed using GRADE methods.

Main results

Seven RCTs with 793 women were included in this review. Three trials compared UAE with abdominal hysterectomy, two trials compared UAE with myomectomy, and two trials compared UAE with either type of surgery (53 hysterectomies and 62 myomectomies).

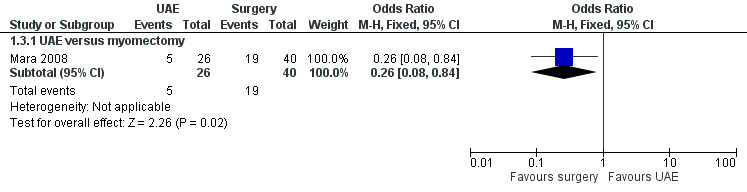

With regard to patient satisfaction rates, our findings were consistent with satisfaction rates being up to 41% lower or up to 48% higher with UAE compared to surgery within 24 months of having the procedure (odds ratio (OR) 0.94; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.59 to 1.48, 6 trials, 640 women, I2 = 5%, moderate quality evidence). Findings were also inconclusive at five years of follow‐up (OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.80, 2 trials, 295 women, I2 = 0%, moderate quality evidence). There was some indication that UAE may be associated with less favourable fertility outcomes than myomectomy, but it was very low quality evidence from a subgroup of a single study and should be regarded with extreme caution (live birth: OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.84; pregnancy: OR 0.29; 95% CI 0.10 to 0.85, 1 study, 66 women).

Similarly, for several safety outcomes our findings showed evidence of a substantially higher risk of adverse events in either arm or of no difference between the groups. This applied to intra‐procedural complications (OR 0.91; 95% CI 0.42 to 1.97, 4 trials, 452 women, I2 = 40%, low quality evidence), major complications within one year (OR 0.65; 95% CI 0.33 to 1.26, 5 trials, 611 women, I2 = 4%, moderate quality evidence) and major complications within five years (OR 0.56; CI 0.27 to 1.18, 2 trials, 268 women). However, the rate of minor complications within one year was higher in the UAE group (OR 1.99; CI 1.41 to 2.81, 6 trials, 735 women, I2 = 0%, moderate quality evidence) and two trials found a higher minor complication rate in the UAE group at up to five years (OR 2.93; CI 1.73 to 4.93, 2 trials, 268 women).

UAE was associated with a higher rate of further surgical interventions (re‐interventions within 2 years: OR 3.72; 95% CI 2.28 to 6.04, 6 trials, 732 women, I2 = 45%, moderate quality evidence; within 5 years: OR 5.79; 95% CI 2.65 to 12.65, 2 trials, 289 women, I2 = 65%). If we assumed that 7% of women will require further surgery within two years of hysterectomy or myomectomy, between 15% and 32% will require further surgery within two years of UAE.

The evidence suggested that women in the UAE group were less likely to require a blood transfusion than women receiving surgery (OR 0.07; 95% CI 0.01 to 0.52, 2 trials, 277 women, I2 = 0%). UAE was also associated with a shorter procedural time (two studies), shorter length of hospital stay (seven studies) and faster resumption of usual activities (six studies) in all studies that measured these outcomes; however, most of these data could not be pooled due to heterogeneity between the studies.

The quality of the evidence varied, and was very low for live birth, moderate for satisfaction ratings, and moderate for most safety outcomes. The main limitations in the evidence were serious imprecision due to wide confidence intervals, failure to clearly report methods, and lack of blinding for subjective outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

When we compared patient satisfaction rates at up to two years following UAE versus surgery (myomectomy or hysterectomy) our findings are that there is no evidence of a difference between the interventions. Findings at five year follow‐up were similarly inconclusive. There was very low quality evidence to suggest that myomectomy may be associated with better fertility outcomes than UAE, but this information was only available from a selected subgroup in one small trial.

We found no clear evidence of a difference between UAE and surgery in the risk of major complications, but UAE was associated with a higher rate of minor complications and an increased likelihood of requiring surgical intervention within two to five years of the initial procedure. If we assume that 7% of women will require further surgery within two years of hysterectomy or myomectomy, between 15% and 32% will require further surgery within two years of UAE. This increase in the surgical re‐intervention rate may balance out any initial cost advantage of UAE. Thus although UAE is a safe, minimally invasive alternative to surgery, patient selection and counselling are paramount due to the much higher risk of requiring further surgical intervention.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Embolization, Therapeutic; Embolization, Therapeutic/methods; Hysterectomy; Leiomyoma; Leiomyoma/blood supply; Leiomyoma/therapy; Length of Stay; Patient Satisfaction; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Uterine Artery Embolization; Uterine Artery Embolization/adverse effects; Uterine Artery Embolization/methods; Uterine Neoplasms; Uterine Neoplasms/blood supply; Uterine Neoplasms/therapy

Plain language summary

Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids

Review question

Is uterine artery embolization a safe and effective alternative treatment in women with symptomatic fibroids?

Background

Uterine fibroids (benign tumours) can cause varied symptoms such as heavy bleeding, pain and reduced likelihood of pregnancy. Surgery (hysterectomy or myomectomy) has traditionally been the main treatment option but it carries a risk of complications. Uterine artery embolization (UAE) is a newer treatment option which blocks the blood supply to the womb and thus shrinks the fibroids and reduces their effects. The evidence was current to April 2014.

Study characteristics

There were seven studies included in the review (793 participants). Three of these compared UAE with hysterectomy, two studies compared UAE with myomectomy, and another two with hysterectomy or myomectomy. The studies differed in their outcomes and length of follow‐up.

Key results

With regard to patient satisfaction rates, our findings were consistent with satisfaction rates being up to 41% lower or up to 48% higher with UAE compared to surgery within 24 months of having the procedure. Findings on satisfaction rates were also inconclusive at five years of follow‐up.

There was very low quality evidence to suggest that fertility outcomes (live birth and pregnancy) may be better after myomectomy than after UAE, but this evidence was based on a small selected subgroup and should be regarded with extreme caution. The UAE group had a shorter hospital stay and a more rapid return to daily activities. With regards to safety, the evidence on major complications was inconclusive and consistent with benefit or harm, or no difference, from either intervention. However, the risk of minor complications was higher after UAE. Moreover, there was a higher likelihood of needing another surgical intervention after UAE, at two year and at five year follow‐up. If we assumed that 7% of women will require further surgery within two years of hysterectomy or myomectomy, between 15% and 32% will require further surgery within two years of UAE. Therefore, it appears that while UAE is a safe option with an earlier initial recovery, it does carry a higher risk of minor complications and the need for further surgery later on.

Quality of the evidence:

The quality of the evidence varied from very low for live birth, to moderate for satisfaction ratings and for most safety outcomes. The main limitations in the evidence were serious imprecision, failure to clearly report methods, and lack of blinding for subjective outcomes.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Uterine artery embolization (UAE) compared to surgery for symptomatic uterine fibroids.

| UAE compared to surgery for symptomatic uterine fibroids | ||||||

| Population: women with symptomatic uterine fibroids Intervention: UAE Comparison: surgery | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Surgery | UAE | |||||

| Satisfaction with treatment up to 24 months | 861 per 1000 | 853 per 1000 (785 to 901) | OR 0.94 (0.59 to 1.48) | 640 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1,2 | |

| Satisfaction with treatment at 5 years | 876 per 1000 | 864 per 1000 (761 to 927) | OR 0.90 (0.45 to 1.80) | 295 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Live birth ‐ UAE versus myomectomy | 475 per 1000 | 190 per 1000 (67 to 432) | OR 0.26 (0.08 to 0.84) | 66 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3,4 | |

| Adverse events: intra‐procedural complications | 63 per 1000 | 57 per 1000 (27 to 117) | OR 0.91 (0.42 to 1.97) | 452 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW5,6,7 | |

| Adverse events: minor post‐procedural complications within one year | 230 per 1000 | 373 per 1000 (296 to 456) | OR 1.99 (1.41 to 2.81) | 735 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1,2 | |

| Adverse events: major post‐procedural complications within one year | 69 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (24 to 85) | OR 0.65 (0.33 to 1.26) | 611 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1,5,7 | |

| Further interventions within 2 years | 71 per 1000 | 222 per 1000 (149 to 317) | OR 3.72 (2.28 to 6.04) | 732 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1,2,8 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Studies unblinded

2Two studies did not fully explain randomisation and allocation concealment, but quality not downgraded for this as their omission from analysis did not substantially change the findings

3 Wide confidence intervals compatible with substantial harm from UAE or with no effect

4Includes only those trial participants who wished to conceive (66/121)

5One study did not fully explain methods of randomisation and allocation concealment, but omission of this study did not substantially affect the findings

6Low event rate

7Wide confidence intervals compatible with substantial harm or benefit from either intervention, or with no effect

8Some statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 45%); quality not downgraded for this as direction of effect is consistent

Background

Description of the condition

Uterine fibroids (also called myomas) are the most commonly found gynaecological benign tumours. The precise factors governing their growth and regression are unknown, but fibroids grow in response to stimulation from sex steroid hormones. They are typically discovered in the late reproductive period and are present in up to 60% of women after the age of 40 years (Okolo 2008). Spontaneous regression occurs following menopause, probably as a result of the reduction in estrogen hormone production by the ovaries.

Complaints associated with fibroids, particularly heavy menstrual bleeding, affect quality of life and comprise a substantial societal burden, with a significant impact on health care use and costs (Cardozo 2012). In the UK, one million women annually seek help for heavy menstrual bleeding (NICE 2007) and reported treatment costs exceed £65m; an estimated 3.5 million work‐days are lost annually (Rahn 2011).

Fibroids can cause heavy and prolonged uterine bleeding, pain, pressure symptoms and subfertility, but rarely cause damage to adjacent organs. Asymptomatic fibroids can be discovered on routine pelvic examination and verified on ultrasound. Treatment of fibroids is generally reserved for those women who experience symptoms and for women planning to become pregnant who have large fibroids or fibroids that significantly distort the uterine cavity.

Description of the intervention

Currently available medical therapies for fibroids have not demonstrated long‐term efficacy. Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone analogues effectively reduce bleeding and decrease fibroid size but can only be used for a limited time because of their adverse effect on bone mass. Medical therapies for heavy menstrual bleeding, such as combined oral contraceptives, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and progestogens (including the Mirena intrauterine system), appear to be less effective in the presence of uterine fibroids although few studies have addressed this issue. There is recent evidence that selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs), namely ulipristal acetate, can be used to treat heavy menstrual bleeding in the short term and to reduce total fibroid volume in preparation for surgery (PEARL I; PEARL II). Surgical therapies for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding related to fibroids include hysteroscopic endometrial ablation, transcervical resection of submucous fibroid, laparoscopic myomectomy or myolysis, laparoscopic bipolar coagulation or dissection of uterine vessels (or both), myomectomy and hysterectomy.

It is not uncommon for women with symptomatic fibroids to have surgical treatment, accounting for between 30% to 70% of the approximately 600,000 hysterectomies performed in the US each year (Broder 2000; Lepine 1997). Other surgical procedures for fibroids are done less commonly, with approximately 35,000 abdominal or open myomectomies each year (NCHS 1998). As with all surgical procedures, hysterectomy and myomectomy are associated with complications. Hysterectomy has an approximately 3% incidence of major complications (Garry 2004), while the rate for myomectomy is less well defined. Myomectomy is associated with long‐term problems such as fibroid recurrence, adhesion formation, and the increased possibility of uterine rupture during pregnancy and vaginal delivery (Gehlbach 1993). There is a high need for effective non‐surgical therapies for uterine fibroids.

Uterine artery embolization (UAE) has established itself as a minimally invasive procedure for reducing symptoms from uterine fibroids. In the past, embolization was used to reduce pelvic pain and bleeding (Greenwood 1987). Only since 1995 has UAE been seen as a potential treatment for menorrhagia related to uterine fibroids (Goodwin 1997; Ravina 1997). Promising results have been obtained with regard to symptom relief but there is concern about post‐procedure pain, post‐embolization syndrome, infection, premature ovarian failure (POF), secondary amenorrhoea due to endometrial atrophy or intrauterine adhesions, and the unknown effect on conception and pregnancy (Khaund 2008).

UAE, like myomectomy, spares the uterus and carries an obvious appeal to women with large fibroids who are either subfertile or repeatedly miscarry. There are reports of live births following fibroid embolization. Potential complications following the procedure are ovarian failure due to impairment of ovarian blood flow and infection leading to fallopian tube damage with subsequent infertility. There has been a report of uterine rupture at childbirth following UAE. There is also the theoretical risk of an adverse effect on placental blood flow following UAE. In these circumstances, there is the possibility that the incidence of pregnancy complications such as preterm labour, intrauterine growth restriction and postpartum haemorrhage could be increased, and further data are awaited. Hence, the UAE procedure is suitable for women with fibroids who have completed their families and also for those wishing to conceive who have symptomatic fibroids (for example heavy menstrual bleeding) after careful and appropriate counselling.

UAE involves complete occlusion of both uterine arteries with particulate emboli, with the objective of causing ischaemic necrosis of the uterine fibroids but no permanent adverse effect on the otherwise normal uterus. This has been performed using general anaesthesia, conscious sedation, and epidural or spinal anaesthesia. Some practitioners administer prophylactic antibiotics. An angiography catheter is inserted directly into the woman's femoral artery and the contralateral uterine artery is then selectively catheterized. The catheter is manoeuvred to the opposite uterine artery (ipsilateral to the femoral puncture site) and the process repeated. The most commonly used agent for occlusion is polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), a non‐biodegradable agent available in a variety of sizes (normally 150 to 1000 microns for this procedure) which is suspended in a contrast solution. Occlusion (blockage) of the uterine vessels is confirmed by angiography (X‐ray dye test) and the catheter removed. The procedure takes between 45 and 135 minutes to complete and the woman is exposed to approximately 20 rads (20 cGy) of ionising radiation to the ovaries (Spies 1999). Women are observed for up to 24 hours post‐procedure and treated with narcotics for pain relief.

How the intervention might work

Successful UAE is meant to totally occlude both the uterine vessels. The normal myometrium (muscle of the womb) rapidly establishes a new blood supply through collateral vessels from the ovarian and vaginal circulations. However, fibroids appear to be supplied by end arteries without the collateral flow found in normal myometrium and, therefore, are preferentially affected by the occlusion. The reduction in blood supply results in a decrease in fibroid volume with resultant improvement in the woman's symptoms.

Why it is important to do this review

The UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends that UAE should be offered as a treatment choice in women presenting with heavy menstrual bleeding. NICE does not indicate a preference in subfertile women (NICE 2007). However, surgical treatment is often used for symptomatic women with fibroids. This is more true for women who have subfertility due to fibroids. All of the surgical procedures are associated with risks. UAE is being suggested as an alternative but is not without its own risks. Therefore, it is important to have the best available evidence to compare different types of interventions. The current state of the evidence reported in this review highlights the high level of uncertainty within the trials indicating that further high quality trials are required.

Objectives

To review the benefits and risks of uterine artery embolization (UAE) versus other medical or surgical interventions for symptomatic uterine fibroids.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of uterine artery embolization versus other interventions.

Types of participants

Women with symptomatic uterine fibroids, with either subjective or objective symptoms (expected to be predominantly heavy menstrual bleeding with or without intermenstrual bleeding, but also including pain and bulk‐related symptoms), or both.

Types of interventions

Bilateral UAE using permanent embolic material versus any other surgical intervention as a primary treatment for symptomatic fibroids, for example myomectomy or hysterectomy. UAE was evaluated as a single therapy, not combined with surgery.

We excluded trials of the occlusion of uterine arteries by any means other than embolization.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Patient satisfaction (up to 24 months and at five years)

Live birth (in comparisons of UAE versus uterine‐sparing procedures only)

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events: immediate complications (intra‐procedural complications, need for blood transfusion); early and late post‐procedural complications (minor and major)

Further interventions

Unscheduled readmission rates

Cost (duration of procedure, length of hospital stay, resumption of normal activities)

Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels post‐procedure (as an indication of ovarian failure)

Fibroid recurrence rate (in comparisons of UAE versus uterine‐sparing procedures only)

Pregnancy (in comparisons of UAE versus uterine‐sparing procedures only)

Health‐related quality of life

Search methods for identification of studies

All eligible studies since the previous version of this review in 2012 were identified by a predefined search strategy that was applied in electronic databases, handsearching, reference lists and contacting authors.

Electronic searches

We searched for all relevant published and unpublished RCTs without language restriction and in consultation with the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator.

Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Specialised Register of controlled trials (inception to 17 April 2014).

Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (inception to 17 April 2014).

Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily Update and Ovid MEDLINE(R) (1950 to 17 April 2014).

Ovid EMBASE (1 January 2010 to 17 April 2014). EMBASE was only searched four years back as the UK Cochrane Centre had handsearched EMBASE to this point and these trials are already in CENTRAL.

Ovid PsycINFO (inception to 17 April 2014).

EBSCO CINAHL (inception to 17 April 2014).

metaRegister of Controlled Trials (http://controlled‐trials.com/mrct/).

Trial registers for ongoing and registered trials: ClinicalTrials.gov, a service of the US National Institutes of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home), World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search portal (www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) (inception to 17 April 2014).

The Cochrane Library (www.cochrane.org/index.htm) for the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (inception to 17 April 2014).

The MEDLINE search was combined with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials which appears in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.0.2, chapter 6, 6.4.11). The EMBASE search was combined with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (see www.sign.ac.uk/mehodology/filters.html#random).

The detailed search strategies are presented in: Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6 and Appendix 7.

Searching other resources

Literature was also identified by requesting reference lists from interventional radiologists known to perform the procedure (identified by membership in a professional society of interventional radiologists) and authors of papers identified via other searches. The citation lists of relevant publications, review articles and included studies were also searched. We contacted authors of published and unpublished trials for additional information when necessary. There was no language restriction.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (AS and JKG) independently reviewed all the studies retrieved by the search for compliance with the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (AS and JKG) independently assessed study characteristics and methodological details of all included studies and extracted information using a pre‐designed data collection tool. Differences in opinion were resolved by consultation with a third review author (MAL). Where additional information on trial methodology or the original trial data were required, corresponding authors were contacted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (AS and JKG) independently assessed study characteristics and methodological details of included studies using data extraction forms to assess the risk of bias in the included studies. Differences in opinion were to be resolved by consultation with a third review author (MAL).

The included studies were assessed for risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) to assess: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, providers and outcome assessors; completeness of outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other potential sources of bias. Two authors (AS and JKG) independently assessed these six domains, with any disagreements resolved by consensus or by discussion with a third author. The conclusions were presented in the 'Risk of bias' table and incorporated into the interpretation of the review findings by means of sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, the results were presented as Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

For continuous data, the mean difference (MD) and 95% CI was used if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measured the same outcome but used different scales, but this was not required.

Unit of analysis issues

Data were analysed per woman randomised.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, levels of attrition were noted.

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out on an intention‐to‐treat basis as far as possible, that is we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. Otherwise, only the available data were analysed and the denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing. For dichotomous outcomes all randomised women were included but for continuous outcomes such as satisfaction rates we only used data that were presented by the trial authors.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a meaningful summary. Following meta‐analysis, statistical heterogeneity between the results of different studies was examined graphically by inspecting the scatter in the data points on the graphs and the overlap in their CIs and, more formally, by checking the results of the Chi2 tests. If we identified substantial heterogeneity we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty in detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, we aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and being alert for duplication of data. If there were 10 or more studies in an analysis, we planned to use a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies).

Data synthesis

Where appropriate, we pooled data from the primary studies using the Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model in the RevMan 5 software.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If heterogeneity was present, we examined clinical considerations which theoretically could lead to heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were planned for the primary outcomes to determine whether the conclusions were robust to arbitrary decisions made regarding the eligibility and analysis of the included studies. These analyses included consideration of whether conclusions would have differed if:

eligibility was restricted to published studies;

eligibility was restricted to studies without high risk of bias;

a random‐effects model had been adopted.

Overall quality of the body of evidence: summary of findings table

We prepared a summary of findings table using Guideline Development Tool software. This table evaluated the overall quality of the body of evidence for the main review outcomes using GRADE criteria (study limitations that is risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). Judgements about evidence quality (high, moderate or low) were justified, documented and incorporated into the reporting of results for each outcome. The outcomes evaluated using GRADE criteria were: satisfaction with treatment up to 24 months and 5 years, live birth rate, intra‐procedural adverse events, minor post‐procedural adverse events, major post‐procedural adverse events within one year, and further interventions within two years). See Table 1.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The search strategy identified 62 potentially relevant citations. Twelve of the 62 citations met the inclusion criteria of the review and were retrieved in full. These 12 citations originated from seven randomised trials, namely EMMY 2010; FUME 2012; Jun 2012; Mara 2008; Pinto 2003; REST 2011; Ruuskanen 2010. The most recent publications have been used as the primary reference for each study as they give the long‐term follow‐up results.

Included studies

Seven studies were included in the review. See the table Characteristics of included studies.

Study design: all seven studies were RCTs.

Participants: all women (n = 793) in the included studies had symptomatic fibroids that justified surgical treatment. Four studies (EMMY 2010; FUME 2012; Pinto 2003; Ruuskanen 2010) excluded women who desired future pregnancies. The Jun 2012 study did not specify the fertility plans of its participants even though the majority of women underwent myomectomy in the surgical arm. The Mara 2008 study included premenopausal women with fibroids who had unfinished reproductive plans. The size of the fibroids was a limiting factor in two studies (larger than 10 cm in Pinto 2003 and 12 cm in Mara 2008). All studies except Pinto 2003 specifically excluded women with submucosal fibroids and pedunculated subserosal fibroids, as at that time both of these were thought to be a contraindication for UAE.

Interventions: three studies compared UAE versus hysterectomy (EMMY 2010; Pinto 2003; Ruuskanen 2010). Two studies (Jun 2012; REST 2011) compared UAE with hysterectomy or myomectomy. In this study the type of surgery (hysterectomy or myomectomy) was the choice of the participant, depending on whether she wished to retain her uterus for fertility or other reasons: 8/51 women opted for myomectomy in the REST 2011 study and 53/62 in the Jun 2012 study. Two studies compared UAE with myomectomy (FUME 2012; Mara 2008). In FUME 2012 six women in the UAE group had a hysterectomy, two had a myomectomy and one a repeat embolization; in the myomectomy group two were converted to hysterectomy and one had a hysterectomy seven months later.

Outcomes: the primary outcomes were patient satisfaction and live birth. Six studies reported on patient satisfaction with treatment up to 24 months (EMMY 2010; Jun 2012; Mara 2008; Pinto 2003; REST 2011; Ruuskanen 2010) and two studies (EMMY 2010; REST 2011) also reported this at five years. Mara 2008 was the only study designed to report on live birth. Another study (REST 2011) reported the reproductive outcome of the small number of women who opted for myomectomy (8/51), but this was not intended as an outcome measure and has not been included in the meta‐analysis.

Secondary outcome measures were adverse events (intra‐procedural, minor and major post‐procedural complications); further interventions; unscheduled readmission rates; cost effectiveness; FSH levels post‐procedure, fibroid recurrence rate, pregnancy and health‐related quality of life. Six studies (EMMY 2010; Jun 2012; Mara 2008; Pinto 2003; REST 2011; Ruuskanen 2010) reported on adverse events, unscheduled visits, resumption of normal activities and length of hospital stay. The safety outcomes in Pinto 2003, namely intra‐procedural, minor and major post‐procedural complications, need for blood transfusion and unscheduled visits, were analysed by treatment received and have been excluded from the analysis for this review. Six studies (EMMY 2010; FUME 2012; Jun 2012; Mara 2008; REST 2011; Ruuskanen 2010) reported on further interventions within two years. Two of these studies ( EMMY 2010; REST 2011) reported the same outcome within five years. Unscheduled readmission rates within four to six weeks were reported by two studies (EMMY 2010; Mara 2008).

Cost effectiveness was analysed by looking at the duration of the procedure, length of hospital stay and resumption of normal activities. Two studies (EMMY 2010; Mara 2008) reported on the time taken to carry out the procedure. The length of hospital stay was reported by all of the seven studies (EMMY 2010; FUME 2012; Jun 2012; Mara 2008; Pinto 2003; REST 2011; Ruuskanen 2010). Five of these also reported on the time taken to resume normal activities (EMMY 2010; Jun 2012; Mara 2008; REST 2011; Ruuskanen 2010).

Ovarian failure was assessed by the FSH levels post‐procedure. Mara 2008 was the only study to report this within six months. EMMY 2010 and REST 2011 assessed long‐term ovarian failure by reporting this at two year follow‐up.

Mara 2008 was the only study designed to look at the impact of the two procedures on fertility (pregnancy and live birth rates). It was also the only study which reported on recurrence of fibroids within two years. The REST 2011 trial reported the reproductive outcome of the small number of women who opted for myomectomy (8/51) but this was not intended as an outcome measure.

FUME 2012 and Jun 2012 reported on health‐related quality of life.

The time of follow‐up was longest in EMMY 2010 and REST 2011, with results published after five years. FUME 2012 reported outcomes at one year and Ruuskanen 2010 at two years. The duration of follow‐up in Pinto 2003 was intended to be two years but the published results only reported six months of follow‐up. We contacted the principal author and were informed that they were unable to continue with the follow‐up for two years as initially intended (Pinto 2003). The mean follow‐up in Mara 2008 was 24.9 months. Jun 2012 reported the health‐related quality of life scores at six month follow up but the rate of complications was reported up to a maximum of 42 months.

Excluded studies

All case series, review articles, letters, editorials and case reports were excluded. Only one RCT was excluded. The Hald 2007 trial of 66 women compared clinical outcomes at six months after treatment with bilateral laparoscopic occlusion of the uterine artery versus uterine leiomyoma embolization. As this trial compared two similar methods of uterine artery occlusion (that is either by embolic or direct occlusion of the uterine arteries) it was not deemed eligible for this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

Risk of selection bias related to random sequence generation was low in six of the included studies. All used a computer‐generated sequence. One study did not clearly report the method of sequence generation used and was rated at unclear risk (Ruuskanen 2010).

Allocation concealment

Risk of selection bias related to allocation concealment was low in five of the studies. They used remote randomisation (EMMY 2010; REST 2011), consecutively numbered opaque, sealed envelopes (FUME 2012; Pinto 2003) or computer randomisation at the point of study entry (Mara 2008). Two studies did not clearly report the method of allocation concealment used and were rated at unclear risk (Jun 2012; Ruuskanen 2010).

Blinding

No blinding was possible in any of the trials as one of the treatment arms included surgery, that is hysterectomy or myomectomy. Therefore, risk of bias was high in all trials for subjective outcomes (such as satisfaction rates) and unclear for other outcomes such as complications and re‐intervention. It was possible that participant blinding might affect the number of readmissions in the immediate post‐operative period as often women are asked to report back with trivial symptoms if they have undergone any relatively new procedure.

Incomplete outcome data

Incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed with an intention‐to‐treat analysis in four trials (EMMY 2010; Mara 2008; REST 2011; Ruuskanen 2010) and their risk of attrition bias was low. In one study (Pinto 2003) intention‐to‐treat analysis was only used to evaluate efficiency. This trial also allowed women to change their allocated intervention. That is, three women assigned to the hysterectomy group underwent UAE and, therefore, the effectiveness and safety parameters were calculated on the actual treatment received (treatment received analysis). The risk of attrition bias was high in this study. Hence, for the review, data from the Pinto trial (Pinto 2003) presented by intention‐to‐treat analysis only have been used. Also the length of follow‐up was meant to be 24 months but the published results were for six months only. We contacted the authors of this trial for the long‐term data and they sent us their 12 month unpublished data, which we could not use for this review because the mean data were incomplete.

The risk of attrition bias in FUME 2012 was high as 23% of women randomised to UAE and 27% of those randomised to myomectomy were excluded from the analysis. The risk of attrition bias in Jun 2012 was low as only two women were lost to follow‐up. Also, in Mara 2008 the existing reproductive results could have been partially influenced by the short duration of the follow‐up.

Selective reporting

There was no indication of selective reporting in any of the included studies and their risk of bias was low. All expected outcomes were reported in all studies.

Other potential sources of bias

No other potential sources of bias were identified in any of the included studies. The findings on quality of life in FUME 2012 differed according to whether change scores or end scores were used, apparently due to non‐statistically significant baseline differences between the groups; results for both measures were reported in the review.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

1. Patient satisfaction

UAE versus any type of surgery

All but one study reported this outcome. Satisfaction rates were measured by asking women whether they would undergo the same treatment again (EMMY 2010; Jun 2012; Pinto 2003; REST 2011; Ruuskanen 2010) or whether they obtained symptom relief (Mara 2008). Jun 2012 did not specify the criteria for measuring the satisfaction rate.

The evidence was inconclusive as CIs were consistent with satisfaction rates, being up to 41% lower or up to 48% higher with UAE compared to surgery within 12 to 24 months of having the procedure (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.48, 6 trials, 640 women, I2 = 5%, moderate quality evidence) (Analysis 1.1, Figure 3). Findings were also inconclusive at five years of follow‐up (OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.80, 2 trials, 295 women, I2 = 0%, moderate grade evidence) (Analysis 1.2, Figure 4). No meaningful heterogeneity was detected.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 1 Satisfaction with treatment up to 24 months.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 UAE versus surgery, outcome: 1.1 Satisfaction with treatment up to 24 months.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 2 Satisfaction with treatment at 5 years.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 UAE versus surgery, outcome: 1.2 Satisfaction with treatment at 5 years.

UAE versus specific types of surgery

Analyses were stratified by type of surgery.

At 12 to 24 months the findings were similarly inconclusive in comparisons of UAE versus hysterectomy (OR 0.63; 95% CI 0.30 to 1.32, 3 trials, 266 women) (EMMY 2010; Pinto 2003; Ruuskanen 2010), versus either hysterectomy or myomectomy (OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.15, 2 trials, 264 women) (Jun 2012; REST 2011) and versus myomectomy (OR 1.05; 95% CI 0.33 to 3.36, 1 trial, 110 women) (Mara 2008). At five years the findings remained inconclusive in comparisons of UAE versus hysterectomy (OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.29 to 1.78, 1 trial, 156 women) (EMMY 2010) and versus either hysterectomy or myomectomy (OR 1.25; 95% CI 0.42 to 3.67, 1 trial, 139 women) (REST 2011).

2. Live birth

UAE versus myomectomy

Live birth was calculated from the limited cohort of participants who tried to conceive in one study of UAE versus myomectomy (Mara 2008): 26 women after UAE and 40 after myomectomy. The evidence suggested that UAE may be associated with a lower live birth rate than surgery (OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.84, 1 trial, 66 women, very low quality evidence) (Analysis 1.3, Figure 5), but CIs were also assiciated with no meaningful difference between the interventions. This finding should be regarded with extreme caution as it was based on a subgroup analysis of those stating a desire to conceive.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 3 Live birth.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 UAE versus surgery, outcome: 1.3 Live birth.

Although REST 2011 was not specifically designed to compare UAE versus myomectomy, this study reported fertility outcomes in a comparison between the UAE arm and a subgroup of eight women in the surgical arm (8/51) who opted for myomectomy rather than hysterectomy. There were four births in the UAE group (4/106) and two in the myomectomy group (2/8). These data were not included in analysis due to the strong risk of selection bias.

Secondary outcomes

1. Adverse events

UAE versus any type of surgery

All seven studies reported complications, at varying time points. The data from Pinto 2003 were not included in the analysis as the study did not utilise the intention‐to‐treat principle to report safety and complications.

When studies were pooled, the findings were inconclusive. CIs suggested substantially higher rates of complications in either arm, or no difference between the groups in the rate of intra‐procedural complications (OR 0.91; 95% CI 0.42 to 1.97, 4 trials, 452 women, I2 = 40%, low quality evidence) (Analysis 1.4), major complications within one year (OR 0.65; 95% CI 0.33 to 1.26, 5 trials, 611 women, I2 = 4%, moderate quality evidence) (Analysis 1.7) or major complications within five years (OR 0.56; CI 0.27 to 1.18, 2 trials, 268 women) (Analysis 1.9).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 4 Adverse events: intraprocedural complications.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 7 Adverse events: major postprocedural complications within one year.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 9 Adverse events: major postprocedural complications.

However, the rate of minor complications within one year was higher in the UAE group (OR 1.99; CI 1.41 to 2.81, 6 trials, 735 women, I2 = 0%, moderate quality evidence) (Analysis 1.6). Longer‐term minor complications were reported in three trials at differing periods of follow‐up. One found no difference between the groups in minor complications at one month to two years (OR 1.82; 95% CI 0.56 to 5.94, 1 trial, 120 women) (Analysis 1.8). The other two trials (of UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy) found a higher minor complication rate in the UAE group up to five years (OR 2.93; CI 1.73 to 4.93, 2 trials, 268 women) (Analysis 1.8).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 6 Adverse events: minor postprocedural complications.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 8 Adverse events: later minor postprocedural complications.

The evidence suggested that women in the UAE group were less likely to require a blood transfusion than women receiving surgery (OR 0.07; 95% CI 0.01 to 0.52, 2 trials, 277 women, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 5 Adverse events: Need for blood transfusion.

UAE versus specific types of surgery

Analyses were stratified by type of surgery.

In comparisons of UAE versus hysterectomy, there was no evidence of a difference between the groups in the rate of intra‐procedural complications, blood transfusions or major complications within one year. However, there were more minor complications in the UAE group than in the hysterectomy group within one year (OR 2.12; 95% CI 1.13 to 3.96, 2 trials, 211 women, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.6). In the comparison of UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy (Jun 2012; REST 2011) there were more minor complications within five years (OR 2.93; CI 1.73 to 4.93, 268 women) (Analysis 1.8). There was no evidence of a difference regarding major complications at one or five years (Analysis 1.7, Analysis 1.9). In comparisons of UAE versus myomectomy, there was no conclusive evidence of a difference between UAE and myomectomy in the rate of intra‐procedural complications (Analysis 1.4), the rate of any complications within the first month (Analysis 1.6) or for up to two years (Analysis 1.8).

A wide CI also made it difficult to draw conclusive evidence with regard to the need for blood transfusion in comparisons of UAE and myomectomy (OR 0.21; 95% CI 0.01 to 4.47, 121 women) (Analysis 1.5).

2. Further interventions

UAE versus any type of surgery

Five studies reported the rate of further interventions within two years, and two studies reported the rate after five years of follow‐up (EMMY 2010; REST 2011). When the studies were pooled there was a higher likelihood of requiring further surgical intervention in women undergoing UAE, both within two years (OR 3.72; 95% CI 2.28 to 6.04, 6 trials, 732 women, I2 = 45%, moderate quality evidence) (Analysis 1.10, Figure 6) and at five years (OR 5.79; 95% CI 2.65 to 12.65, 2 trials, 289 women, I2 = 65%) (Analysis 1.11).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 10 Further interventions within 2 years.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 UAE versus surgery, outcome: 1.10 Further interventions within 2 years.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 11 Further interventions within 5 years.

UAE versus specific types of surgery

Analyses were stratified by type of surgery. In comparisons of UAE versus hysterectomy, further interventions were more likely in the UAE group than in the surgical group within two years (OR 2.99; 95% CI 1.31 to 6.80, 2 trials, 209 women) (EMMY 2010; Ruuskanen 2010) and at five years (OR 3.43; 95% CI 1.41 to 8.30, 1 trial, 145 women) (EMMY 2010). In the comparison of UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy (Jun 2012; REST 2011), further interventions were also more likely in the UAE group than in the surgical group within two years (OR 2.83; 95% CI 1.29 to 6.24, 281 women) and at five years (OR 20.34; 95% CI 2.68 to 154.59, 144 women). Similarly, in the comparison of UAE versus myomectomy (FUME 2012; Mara 2008) further interventions were more likely in the UAE group than in the surgical group within two years (OR 6.89; 95% CI 2.60 to 18.27, 242 women).

3. Unscheduled visits and readmissions

UAE versus any type of surgery

Three studies reported this outcome. Data from Pinto 2003 were excluded. There was a higher rate of unscheduled visits or readmissions within 4 to 6 weeks in the UAE group (OR 2.74; 95% CI 1.42 to 5.26, 2 trials, 278 women, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 12 Unscheduled readmission rate within 4‐6 weeks.

UAE versus specific types of surgery

Analyses were stratified by type of surgery. In comparisons of UAE versus hysterectomy, unscheduled visits or readmissions within six weeks were more likely in the UAE group than in the surgical group (OR 2.79; 95% CI 1.41 to 5.49, 1 trial, 157 women) (EMMY 2010). In the comparison of UAE versus myomectomy (Mara 2008) CIs were extremely wide and suggested higher or lower rates of unscheduled visits or readmissions within four weeks in either group, or no difference between the groups (OR 2.21; 95% CI 0.20 to 25.09, 121 women).

4. Cost

The duration of the procedure, length of hospital stay and resumption of normal activities were used as surrogate markers for cost.

Duration of procedure

UAE versus any type of surgery

Two studies reported this outcome. They were not pooled due to highly significant statistical heterogeneity (P < 0.00001) attributable to the differing types of surgery used.

UAE versus specific types of surgery

Analyses were stratified by type of surgery (Analysis 1.13). In a comparison of UAE versus hysterectomy (EMMY 2010), the duration of the procedure was shorter in the UAE group (MD ‐16.40 min, 95% CI ‐26.04 to ‐6.76, 1 trial, 156 women) (EMMY 2010). In the comparison of UAE versus myomectomy (Mara 2008) the duration of the procedure was also shorter in the UAE group but with a more marked difference (MD ‐49.70 min, 95% CI ‐58.76 to ‐40.64, 121 women).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 13 Cost: duration of procedure (minutes).

Length of hospital stay

UAE versus any type of surgery

All studies reported this outcome. They were not pooled due to highly significant statistical heterogeneity (P < 0.00001) attributable to the differing types of surgery used.

UAE versus specific types of surgery

Analyses were stratified by type of surgery (Analysis 1.14). In the comparison of UAE versus hysterectomy, length of hospital stay was shorter in the UAE group in all three studies, with the MD ranging from 2.2 days (95% CI 1.6 to 2.8) in Ruuskanen 2010 to 4.14 days (95% CI 2.9 to 5.38) in Pinto 2003. These studies were not pooled due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 79%). In the comparison of UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy (Jun 2012; REST 2011) the length of hospital stay was also shorter in the UAE group: REST 2011 found a MD of 3.10 days (95% CI 2.55 to 3.65) and Jun 2012 found a MD of 3.4 days (95% CI 2.03 to 4.77). In the comparison of UAE versus myomectomy (FUME 2012; Mara 2008), length of hospital stay was also shorter in the UAE group: Mara 2008 found a MD of 1.10 days (95% CI 0.56 to 1.64) and FUME 2012 found a MD of 4 days (95% CI 3.03 to 4.97). These studies were not pooled due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 96%).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 14 Cost: length of hospital stay (days).

Time to resumption of normal activities

UAE versus any type of surgery

Six studies reported this outcome (Analysis 1.15) but the data from Pinto 2003 have been excluded from the analysis. The comparison of UAE versus myomectomy (Mara 2008) was not included in the pooled analysis as this resulted in highly significant statistical heterogeneity (P < 0.00001), explicable by the different type of surgery in this comparison. When the other four studies were analysed, the time to resumption of normal activities was shorter in the UAE group compared to any other surgical intervention (Analysis 1.15).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 15 Cost: resumption of normal activities (days).

UAE versus specific types of surgery

Analyses were stratified by type of surgery (Analysis 1.15). In the comparison of UAE versus hysterectomy, time to resumption of normal activities was shorter in the UAE group (MD ‐22.85 days; 95% CI ‐27.30 to ‐18.40, 2 trials, 188 women) (EMMY 2010; Ruuskanen 2010). Similarly, in the comparison of UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy (Jun 2012; REST 2011) the time to resumption of normal activities was shorter in the UAE group (MD ‐13.68 days; 95% CI ‐16.05 to ‐11.30, 220 women). In a comparison of UAE versus myomectomy (Mara 2008), time to resumption of normal activities was also shorter in the UAE group but the difference was less marked (MD ‐10.20 days; 95% CI ‐13.60, to ‐6.80, 121 women).

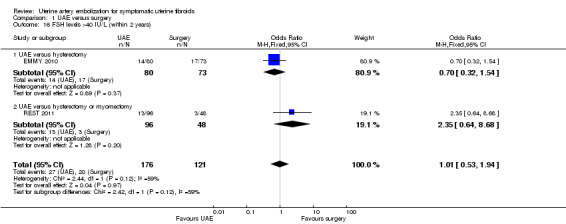

5. FSH levels as an indicator of ovarian failure

UAE versus any type of surgery

Three studies reported this outcome, using differing thresholds for the FSH level. In two studies, which reported the number of women with FSH levels over 40 IU/L within two years (EMMY 2010; REST 2011), there was no evidence of a difference between the groups (OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.53 to 1.94, 297 women) (Analysis 1.16). One study reporting the number of women with FSH over 10 IU/L within six months (Mara 2008) also found no conclusive evidence of a difference between the groups (OR 4.80; 95% CI 0.97 to 23.64, 120 women) (Analysis 1.17).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 16 FSH levels >40 IU/L (within 2 years).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 17 FSH levels >10 IU/L (within 6 months).

UAE versus specific types of surgery

Analyses were stratified by type of surgery. There was no significant difference between the groups for this outcome in individual comparisons of UAE versus hysterectomy (EMMY 2010), UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy (REST 2011) or UAE versus myomectomy (Mara 2008).

6. Fibroid recurrence rate

One of the studies comparing UAE versus myomectomy (Mara 2008) looked at the recurrence rate of fibroids within two years of follow‐up. There was inconclusive evidence of a difference between the groups as the CI was very wide (OR 1.32; 95% CI 0.38 to 4.57, 120 women) (Analysis 1.18).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 18 Fibroid recurrence within 2 years.

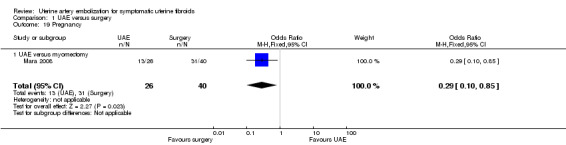

7. Pregnancy rate

One of the studies comparing UAE versus myomectomy (Mara 2008) reported this outcome. The pregnancy rate was calculated from the limited cohort of participants who tried to conceive (26 women after UAE and 40 after myomectomy). There were fewer pregnancies in the UAE group (OR 0.29; 95% CI 0.10 to 0.85, 66 women) (Analysis 1.19) but the CIs showed no evidence of a difference between the interventions. This finding should be regarded with extreme caution as it was based on a subgroup analysis of those stating a desire to conceive.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 UAE versus surgery, Outcome 19 Pregnancy.

Although REST 2011 was not specifically designed to compare UAE versus myomectomy, this study reported fertility outcomes in a comparison between the UAE arm and a subgroup of eight women in the surgical arm (8/51) who opted for myomectomy rather than hysterectomy. There were 10 pregnancies in the UAE group (10/106) and two in the myomectomy group (2/8). These data were not included in the analysis due to the strong risk of selection bias.

8. Health‐related quality of life

Three trials reported health‐related quality of life. The FUME 2012 study used the UFS‐QOL self‐administered questionnaire whilst the Medical Outcomes Study 36‐Item Short Form General Health Survey (SF‐36) was used in Jun 2012 and REST 2011. Both these measures use a 0 to 100 scale.

In FUME 2012, when the overall UFS‐QOL scores at one year follow‐up were compared, they were significantly higher in the myomectomy group than in the UAE group (MD ‐13.40; 95% CI ‐ 21.41 to ‐5.39, 122 women). However, the study authors noted that scores were (non‐significantly) lower at baseline in the UAE group. When mean changes in score from baseline were compared there was little clinically meaningful difference between the two groups (MD ‐7.60; 95% CI ‐17.55 to ‐2.35, 122 women). There was an improvement from baseline in overall quality of life in both groups.

Two trials (Jun 2012; REST 2011) reported SF‐36 quality of life (QoL) outcome measures at 6 and 12 months, respectively, on an 11 point score. Surgery was associated with a greater improvement in QoL at 1 year than UAE (MD 9.14; 95% CI 8.04 to 10.23, 281 women). This was of borderline clinical significance (the difference in QoL score seemed to be similar in both cases (7% versus 9%)).

Sensitivity analyses

Use of a random‐effects model did not materially change any of the effect estimates. There were insufficient studies to conduct other planned sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This Cochrane review summarises the current evidence on the effectiveness of UAE compared to surgery (hysterectomy or myomectomy) as a treatment option for symptomatic uterine fibroids. The evidence on satisfaction rates was inconclusive in spite of a higher rate of post‐procedural complications and further re‐interventions in the UAE arm of the studies. Our findings showed evidence of benefit or harm from either intervention, or of no difference between the interventions.

Mara 2008 was the only study which specifically looked at the impact of UAE versus myomectomy on fertility, an important parameter as both are uterine‐sparing procedures. The findings for live birth suggested a possible benefit from myomectomy. However, as noted above, this finding should be regarded with extreme caution as it was based on a subgroup analysis of those stating a desire to conceive, and the confidence intervals were evidence of no meaningful difference between the interventions.

UAE was advantageous over hysterectomy or myomectomy with regard to a shorter hospital stay, a quicker return to full activity, and reduced likelihood of a need for blood transfusion. However, UAE was associated with an increased short‐term (within one year) and up to five year risk of minor complications. Findings with regard to major complications were inconclusive.

In the previous version of this review, the authors concluded that the women opting for UAE should be counselled about a higher surgical intervention rate in the longer term. This is supported by the five year follow‐up data from the EMMY and REST trials. There is a five‐fold increase in the likelihood of needing further intervention after UAE. Although UAE initially appears to be a cost effective alternative to hysterectomy, the long‐term follow‐up at five years shows that this advantage is lost due to a subsequent higher rate of re‐intervention (EMMY 2010; REST 2011). Surgery was also associated with a slight improvement in quality of life compared to UAE but this might not be clinically meaningful.

See also 'Summary of findings' table 3.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This Cochrane review was performed according to the current standards of The Cochrane Collaboration and the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group. Applicability and completeness of this review reflect the study characteristics and completeness by which they were reported. Even though the primary outcome measures differed for different trials, they collected similar outcome data, which made this review possible. Given that UAE is a uterine‐sparing procedure, there was only one trial comparing it with another uterine‐sparing procedure (myomectomy) that reported on fertility and pregnancy outcomes.

Current findings apply to women similar to the populations of the included studies: premenopausal women with menorrhagia caused by uterine fibroids, confirmed either by ultrasonography or MRI, and fit to undergo surgical treatment. Review findings apply to the time frame of six months to five years after the intervention.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence had a wide range and was very low for live birth, moderate for satisfaction ratings, and moderate for most safety outcomes. The main limitations in the evidence were serious imprecision due to wide confidence intervals, failure to clearly report methods, and lack of blinding for subjective outcomes. There was only one trial subgroup which examined fertility outcomes, and this limits the possibility of drawing any conclusions regarding the effects of UAE on fertility and pregnancy. Overall, the imprecision of the findings meant that few firm conclusions could be drawn.

A detection bias may be present for subjective outcomes as blinding was not performed. Participant blinding may not be feasible due to ethical issues, and blinding of the physician is not practical. It is possible that participant blinding might have affected the number of readmissions in the immediate post‐operative period as often women are asked to report back with trivial symptoms if they have undergone any relatively new procedure. The most important consideration was study power. The RCTs were all limited by relatively small samples. Power issues underline the importance of meta‐analysis.

Potential biases in the review process

The strength of this review lies in the application of Cochrane methodology. An extensive literature search was applied, therefore we believe that the likelihood is quite high that all relevant studies were identified.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The findings of this review are in keeping with the results of the systematic review commissioned by NICE (Coleman 2004). This review was based on one RCT (Pinto 2003), two comparative studies, one patient questionnaire survey, and 32 papers from 25 case series. The review concluded that there was a reduction in mean uterine volume of 26% to 59% and fibroid volume of 40% to 75% in the first six months following UAE. In studies with longer follow‐up, this was shown to continue in most women. The review quoted the clinical success rate, that is improvement of symptoms, mainly menorrhagia, to be in the range of 60% to 90%.

The findings are further supported by another large cohort study (HOPEFUL 2007). This was a multi‐centre retrospective study comparing the experiences of two representative cohorts of women who received one of two alternative treatments for symptomatic fibroids from the mid‐1990s (hysterectomy, N = 459; UAE, N = 649). More women in the hysterectomy cohort reported relief from fibroid symptoms (95% versus 85%, P < 0.0001) but only 85% would recommend the treatment to a friend compared with 91% in the UAE arm. There was a 23% (95% CI 19% to 27%) chance of requiring further treatment for fibroids after UAE at a mean follow‐up of 4.6 years, which is similar to the findings of the current review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

When we compared patient satisfaction rates at up to two years following UAE versus surgery (myomectomy or hysterectomy), our findings were evidence of substantial benefit or harm from either intervention, or of no difference between them. Findings at five year follow‐up were similarly inconclusive. There was very low quality evidence to suggest that myomectomy may be associated with better fertility outcomes than UAE, but this information was only available from a selected subgroup in one small trial and should be regarded with extreme caution.

We found no clear indication of a difference between UAE and surgery in the risk of major complications, but UAE was associated with a higher rate of minor complications and an increased likelihood of requiring surgical intervention within two to five years of the initial procedure. If we assume that 7% of women will require further surgery within two years of hysterectomy or myomectomy, between 15% and 32% will require further surgery within two years of UAE. This increase in the surgical re‐intervention rate may balance out any initial cost advantage of UAE. Thus although UAE is a safe, minimally invasive alternative to surgery, patient selection and counselling is paramount due to the much higher risk of requiring further surgical intervention.

Implications for research.

Although we have some long term follow‐up studies comparing UAE with hysterectomy, there is a continued need for further larger randomised controlled trials assessing fertility outcomes of UAE in women with symptomatic fibroids, that is by comparing UAE with myomectomy. The FEMME study (UK) is currently ongoing and we await the results.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 November 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The conclusions of the review have not changed. |

| 11 November 2014 | New search has been performed | One small study by Jun et al 2012 added to the review. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2005 Review first published: Issue 1, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 July 2012 | Amended | New study added ‐ Fume 2012. Conclusions not changed. |

| 8 March 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | All analyses now combined (UAE versus any surgery) and stratified by type of surgery. |

| 8 March 2012 | New search has been performed | Review updated with long term 5 year follow‐up reported by the REST group and EMMY groups. Ruuskanen 2010 and Manyonda 2012 added to the review. |

| 19 March 2009 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 14 November 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Review Group in Auckland.

We would also like to thank the corresponding authors Ms Isabel Pinto and Ms Lilian Murray who took time to respond to our request for further information.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MDSG search string

Keywords CONTAINS "fibroids" or "Leiomyoma" or "myoma" or "uterine fibroids" or "uterine leiomyomas" or "uterine myomas" or Title CONTAINS "fibroids" or "Leiomyoma" or "myoma" or "uterine fibroids" or "uterine leiomyomas" or "uterine myomas"

AND

Keywords CONTAINS "uterine artery embolization" or "UAE" or Title CONTAINS "uterine artery embolization" or "UAE"

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

The MEDLINE database was searched using the following subject headings and keywords:

1 exp Embolization, Therapeutic/ (23874) 2 (uter$ arter$ adj3 emboli#ation$).tw. (999) 3 UAE.tw. (1663) 4 (fibroid$ adj3 emboli#ation$).tw. (257) 5 or/1‐4 (25336) 6 exp leiomyoma/ or exp myoma/ (17581) 7 (leiomyoma$ or myoma$).tw. (13026) 8 fibro$.tw. (359782) 9 hysteromyom$.tw. (49) 10 or/6‐9 (376897) 11 5 and 10 (1409) 12 randomised controlled trial.pt. (321305) 13 controlled clinical trial.pt. (83863) 14 randomized.ab. (236535) 15 placebo.tw. (137888) 16 clinical trials as topic.sh. (159162) 17 randomly.ab. (173282) 18 trial.ti. (101540) 19 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (52610) 20 or/12‐19 (787118) 21 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (3709121) 22 20 not 21 (726837) 23 11 and 22 (117)

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

The EMBASE database was searched using the following subject headings and keywords:

1 exp Uterine Artery Embolization/ (1317) 2 (uter$ arter$ adj3 emboli#ation$).tw. (1313) 3 UAE.tw. (2164) 4 (fibroid$ adj3 emboli#ation$).tw. (371) 5 or/1‐4 (3507) 6 exp benign uterus tumor/ or exp leiomyoma/ or exp uterus myoma/ (18702) 7 (leiomyoma$ or myoma$).tw. (14385) 8 fibro$.tw. (389052) 9 hysteromyom$.tw. (78) 10 or/6‐9 (407253) 11 5 and 10 (1300) 12 Clinical Trial/ (820351) 13 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (291727) 14 exp randomization/ (54876) 15 Single Blind Procedure/ (14365) 16 Double Blind Procedure/ (101449) 17 Crossover Procedure/ (31081) 18 Placebo/ (186763) 19 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (65701) 20 Rct.tw. (7913) 21 random allocation.tw. (1060) 22 randomly allocated.tw. (15732) 23 allocated randomly.tw. (1715) 24 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (688) 25 Single blind$.tw. (11180) 26 Double blind$.tw. (118790) 27 (treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (249) 28 placebo$.tw. (160855) 29 prospective study/ (175478) 30 or/12‐29 (1153000) 31 case study/ (13675) 32 case report.tw. (209434) 33 abstract report/ or letter/ (797863) 34 or/31‐33 (1016890) 35 30 not 34 (1119551) 36 11 and 35 (251)

Appendix 4. CENTRAL search strategy

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, 4th Quarter 2011, and again most recently on 17 April 2014. The CENTRAL database was searched using the following subject headings and keywords:

1 exp Embolization, Therapeutic/ (380) 2 (uter$ arter$ adj3 emboli#ation$).tw. (63) 3 UAE.tw. (221) 4 (fibroid$ adj3 emboli#ation$).tw. (15) 5 or/1‐4 (584) 6 exp leiomyoma/ or exp myoma/ (346) 7 (leiomyoma$ or myoma$).tw. (340) 8 fibro$.tw. (5954) 9 hysteromyom$.tw. (15) 10 or/6‐9 (6297) 11 5 and 10 (67)

Appendix 5. PsycINFO search strategy

The PsycINF0 database was searched using the following subject headings and keywords:

1 (uter$ adj3 emboli?ation$).tw. (2) 2 UAE.tw. (133) 3 (fibroid$ adj3 emboli?ation$).tw. (0) 4 or/1‐3 (135) 5 (leiomyoma$ or myoma$).tw. (28) 6 fibro$.tw. (4305) 7 hysteromyom$.tw. (2) 8 or/5‐7 (4331) 9 4 and 8 (0)

Appendix 6. CINAHL search strategy

| # | Query | Results |

| S27 | S11 AND S25 | 57 |

| S26 | S11 AND S25 | 94 |

| S25 | S12 OR S13 or S14 or S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 | 883,706 |

| S24 | TX allocat* random* | 3,869 |

| S23 | (MH "Quantitative Studies") | 11,815 |

| S22 | (MH "Placebos") | 8,705 |

| S21 | TX placebo* | 31,365 |

| S20 | TX random* allocat* | 3,869 |

| S19 | (MH "Random Assignment") | 37,008 |

| S18 | TX randomi* control* trial* | 71,284 |

| S17 | TX ( (singl* n1 blind*) or (singl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (doubl* n1 blind*) or (doubl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (tripl* n1 blind*) or (tripl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (trebl* n1 blind*) or (trebl* n1 mask*) ) | 710,423 |

| S16 | TX ( (trebl* n1 blind*) or (trebl* n1 mask*) ) | 104 |

| S15 | TX ( (trebl* n1 blind*) or (trebl* n1 mask*) ) | 0 |

| S14 | TX clinic* n1 trial* | 162,339 |

| S13 | PT Clinical trial | 75,742 |

| S12 | (MH "Clinical Trials+") | 173,495 |

| S11 | S5 AND S10 | 407 |

| S10 | S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 | 2,290 |

| S9 | TX fibroid* | 820 |

| S8 | TX hysteromyom* | 3 |

| S7 | TX (leiomyoma* or myoma*) | 2,132 |

| S6 | (MM "Myoma") | 59 |

| S5 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 | 3,231 |

| S4 | TX (fibroid* N3 emboli?ation*) | 132 |

| S3 | TX UAE | 541 |

| S2 | TX (uter* arter* N3 emboli?ation*) | 450 |

| S1 | (MM "Uterine Artery Embolization"# OR #MM "Embolization, Therapeutic"# | 2,634 |

Appendix 7. Clinical trials registries: International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov

'uterine artery embolization' AND 'fibroid*'

Clinicaltrials.gov: (22)

ICTRP: (1)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. UAE versus surgery.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Satisfaction with treatment up to 24 months | 6 | 640 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.59, 1.48] |

| 1.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 3 | 266 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.30, 1.32] |

| 1.2 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy | 2 | 264 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.64, 2.58] |

| 1.3 UAE versus myomectomy | 1 | 110 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.33, 3.36] |

| 2 Satisfaction with treatment at 5 years | 2 | 295 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.45, 1.80] |

| 2.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 1 | 156 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.29, 1.78] |

| 2.2 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy | 1 | 139 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.42, 3.67] |

| 3 Live birth | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 UAE versus myomectomy | 1 | 66 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.26 [0.08, 0.84] |

| 4 Adverse events: intraprocedural complications | 4 | 452 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.42, 1.97] |

| 4.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 2 | 209 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.44, 3.44] |

| 4.2 UAE versus myomectomy | 2 | 243 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.18, 2.03] |

| 5 Adverse events: Need for blood transfusion | 2 | 277 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.01, 0.52] |

| 5.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 1 | 156 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [0.00, 0.67] |

| 5.2 UAE versus myomectomy | 1 | 121 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.01, 4.47] |

| 6 Adverse events: minor postprocedural complications | 6 | 735 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.99 [1.41, 2.81] |

| 6.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 2 | 211 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.12 [1.13, 3.96] |

| 6.2 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy | 2 | 281 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.51 [1.49, 4.23] |

| 6.3 UAE versus myomectomy | 2 | 243 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.62, 2.44] |

| 7 Adverse events: major postprocedural complications within one year | 5 | 611 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.33, 1.26] |

| 7.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 2 | 211 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.22, 4.58] |

| 7.2 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy | 1 | 157 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.30, 1.74] |

| 7.3 UAE versus myomectomy | 2 | 243 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.06, 1.50] |

| 8 Adverse events: later minor postprocedural complications | 3 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy (to 5 years) | 2 | 268 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.93 [1.73, 4.93] |

| 8.2 UAE versus myomectomy (1 month‐2 years) | 1 | 120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.82 [0.56, 5.94] |

| 9 Adverse events: major postprocedural complications | 3 | 388 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.27, 1.18] |

| 9.1 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy (to 5 years) | 2 | 268 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.27, 1.18] |

| 9.2 UAE versus myomectomy (1 month‐2 years) | 1 | 120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Further interventions within 2 years | 6 | 732 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.72 [2.28, 6.04] |

| 10.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 2 | 209 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.99 [1.31, 6.80] |

| 10.2 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy | 2 | 281 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.83 [1.29, 6.24] |

| 10.3 UAE versus myomectomy | 2 | 242 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.89 [2.60, 18.27] |

| 11 Further interventions within 5 years | 2 | 289 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.79 [2.65, 12.65] |

| 11.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 1 | 145 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.43 [1.41, 8.30] |

| 11.2 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy | 1 | 144 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 20.34 [2.68, 154.59] |

| 12 Unscheduled readmission rate within 4‐6 weeks | 2 | 278 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.05, 0.22] |

| 12.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 1 | 157 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.23 [0.09, 0.38] |

| 12.2 UAE versus myomectomy | 1 | 121 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.04, 0.07] |

| 13 Cost: duration of procedure (minutes) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 13.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 1 | 156 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐16.40 [‐26.04, ‐6.76] |

| 13.2 UAE versus myomectomy | 1 | 121 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐49.7 [‐58.76, ‐40.64] |

| 14 Cost: length of hospital stay (days) | 7 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 14.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 14.2 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 14.3 UAE versus myomectomy | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 15 Cost: resumption of normal activities (days) | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 15.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 2 | 188 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐22.85 [‐27.30, ‐18.40] |

| 15.2 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy | 2 | 220 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐13.68 [‐16.05, ‐11.30] |

| 15.3 UAE versus myomectomy | 1 | 121 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐10.20 [‐13.60, ‐6.80] |

| 16 FSH levels >40 IU/L (within 2 years) | 2 | 297 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.53, 1.94] |

| 16.1 UAE versus hysterectomy | 1 | 153 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.32, 1.54] |

| 16.2 UAE versus hysterectomy or myomectomy | 1 | 144 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.35 [0.64, 8.68] |

| 17 FSH levels >10 IU/L (within 6 months) | 1 | 120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.8 [0.97, 23.64] |

| 17.1 UAE versus myomectomy | 1 | 120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.8 [0.97, 23.64] |

| 18 Fibroid recurrence within 2 years | 1 | 120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.38, 4.57] |