Abstract

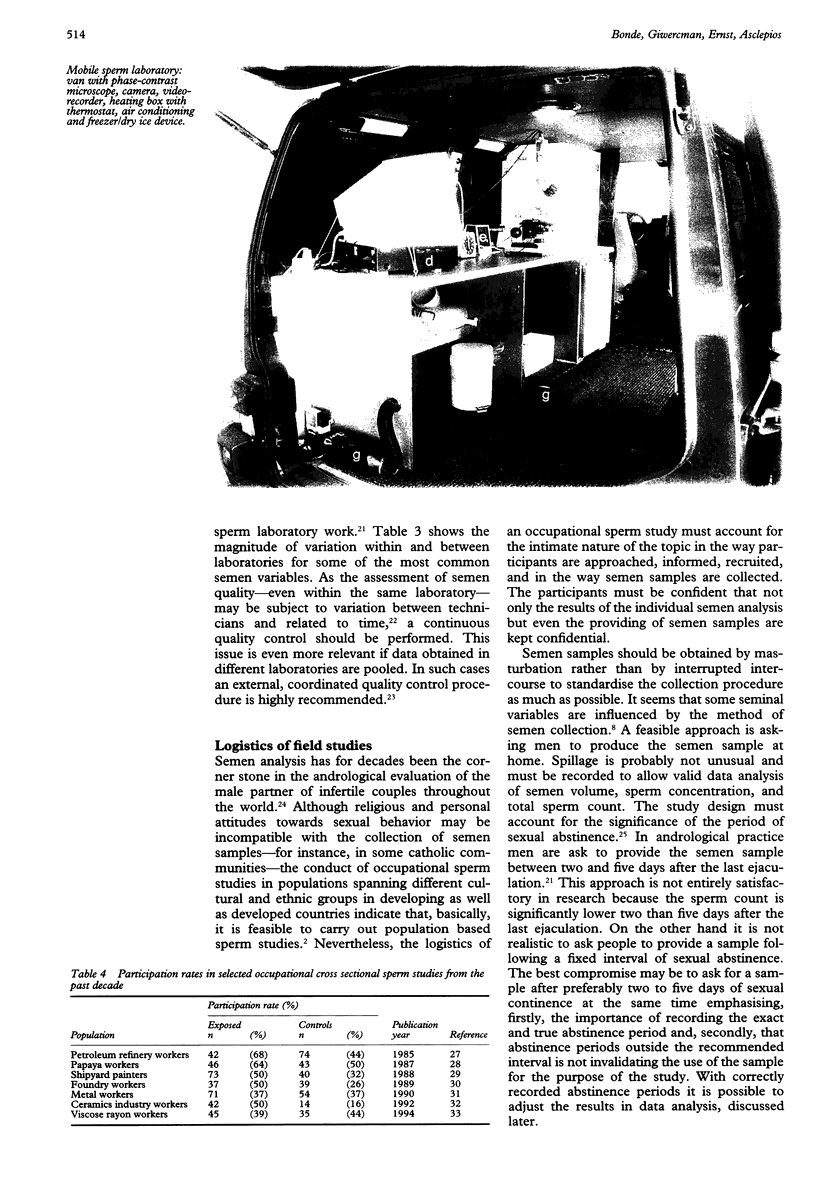

Malfunction of the male reproductive system might be a sensitive marker of environmental hazards, the effects of which may extend beyond reproductive function. The testis is more vulnerable to heat and ionising radiation than any other organ of the body and several xenobiotics are known to disrupt spermatogenesis after low level exposure. Studies of environmental impact on human health are often most informative and accurate when carried out in the workplace where exposures can be high and easy to document. Semen analysis provides readily obtainable information on testicular function. The main advantages in comparison with functional measures such as fertility rates and time taken to conceive are the possibilities to examine men independently of marriage and pregnancy, to find changes of fecundity with different exposures within the same person and to detect adverse effects when no alteration of fertility is yet taking place. In the implementation of an occupational sperm study considerable attention must be paid to logistic issues. A mobile laboratory unit for initial semen preparation and processing may in some situations increase worker compliance and the quality of sperm cell motility. The cross sectional design which has been used in almost all male reproductive studies so far has several severe limitations including selection bias because of differential participation, difficulties in defining a suitable reference group, and lack of information about the time dimension of the cause-effect relation. The longitudinal design deals adequately with most of these constraints. Semen samples are collected before, during, and possibly after exposure to the risk factor of interest and causal inferences are based upon change of semen variables within a man over time rather than upon differences between men. The logistics of the longitudinal study may benefit from pre-employment health examinations to enrol newly hired workers and require fewer participants to obtain comparable statistical power. In conclusion, andrological methods and epidemiological designs are available for the implementation of valid studies concerned with environmental impact on human testicular function. Occupational sperm studies should probably not be the first choice when the objective is initial screening of environmental impact on fertility but should be implemented when their is a need to corroborate or refuse earlier evidence that specific exposures have impact on testicular function.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arumugam K., Omar S. Z. The use of the semen analysis in predicting fertility outcome. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992 May;32(2):154–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1992.tb01929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahamondes L., Alma F. A., Faúndes A., Vera S. Score prognosis for the infertile couple based on historical factors and sperm analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1994 Sep;46(3):311–315. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(94)90411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonde J. P. Semen quality and sex hormones among mild steel and stainless steel welders: a cross sectional study. Br J Ind Med. 1990 Aug;47(8):508–514. doi: 10.1136/oem.47.8.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonde J. P. Semen quality and sex hormones among mild steel and stainless steel welders: a cross sectional study. Br J Ind Med. 1990 Aug;47(8):508–514. doi: 10.1136/oem.47.8.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonde J. P. Semen quality in welders before and after three weeks of non-exposure. Br J Ind Med. 1990 Aug;47(8):515–518. doi: 10.1136/oem.47.8.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonde J. P. Semen quality in welders exposed to radiant heat. Br J Ind Med. 1992 Jan;49(1):5–10. doi: 10.1136/oem.49.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper T. G., Neuwinger J., Bahrs S., Nieschlag E. Internal quality control of semen analysis. Fertil Steril. 1992 Jul;58(1):172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figà-Talamanca I., Dell'Orco V., Pupi A., Dondero F., Gandini L., Lenzi A., Lombardo F., Scavalli P., Mancini G. Fertility and semen quality of workers exposed to high temperatures in the ceramics industry. Reprod Toxicol. 1992;6(6):517–523. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(92)90036-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson A., Hedner P., Schütz A., Skerfving S. Occupational lead exposure and pituitary function. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1989;61(4):277–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00381426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine D. S., Macleod I. C., Templeton A. A., Masterton A., Taylor A. A prospective clinical study of the relationship between the computer-assisted assessment of human semen quality and the achievement of pregnancy in vivo. Hum Reprod. 1994 Dec;9(12):2324–2334. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L., Petty C. S., Neaves W. B. Influence of age on sperm production and testicular weights in men. J Reprod Fertil. 1984 Jan;70(1):211–218. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger T. F., Menkveld R., Stander F. S., Lombard C. J., Van der Merwe J. P., van Zyl J. A., Smith K. Sperm morphologic features as a prognostic factor in in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1986 Dec;46(6):1118–1123. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)49891-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. J., Brown M. H., Bell M., Shue F., Greenberg G. N., Bordson B. L. Air-conditioned environments do not prevent deterioration of human semen quality during the summer. Fertil Steril. 1992 May;57(5):1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. J., Mathew R. M., Brown M. H., Hurtt M. E., Bentley K. S., Mohr K. L., Working P. K. Computer-assisted semen analysis: results vary across technicians who prepare videotapes. Fertil Steril. 1989 Oct;52(4):673–677. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60985-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. J., Symons M. J., Balogh S. A., Arndt D. M., Kaswandik N. T., Gentile J. W. A method for monitoring the fertility of workers. 1. Method and pilot studies. J Occup Med. 1980 Dec;22(12):781–791. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198012000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. J., Symons M. J., Balogh S. A., Milby T. H., Whorton M. D. A method for monitoring the fertility of workers. 2. Validation of the method among workers exposed to dibromochloropropane. J Occup Med. 1981 Mar;23(3):183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACLEOD J. Semen quality in 1000 men of known fertility and in 800 cases of infertile marriage. Fertil Steril. 1951 Mar-Apr;2(2):115–139. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)30482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod J., Wang Y. Male fertility potential in terms of semen quality: a review of the past, a study of the present. Fertil Steril. 1979 Feb;31(2):103–116. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)43808-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod I. C., Irvine D. S. The predictive value of computer-assisted semen analysis in the context of a donor insemination programme. Hum Reprod. 1995 Mar;10(3):580–586. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makler A., Zaidise I., Paldi E., Brandes J. M. Factors affecting sperm motility. I. In vitro change in motility with time after ejaculation. Fertil Steril. 1979 Feb;31(2):147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)43815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meistrich M. L. Effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy on spermatogenesis. Eur Urol. 1993;23(1):136–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittwoch U. Sex determination and sex reversal: genotype, phenotype, dogma and semantics. Hum Genet. 1992 Jul;89(5):467–479. doi: 10.1007/BF00219168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negro-Vilar A. Stress and other environmental factors affecting fertility in men and women: overview. Environ Health Perspect. 1993 Jul;101 (Suppl 2):59–64. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101s259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwinger J., Behre H. M., Nieschlag E. External quality control in the andrology laboratory: an experimental multicenter trial. Fertil Steril. 1990 Aug;54(2):308–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paston M. J., Sarkar S., Oates R. P., Badawy S. Z. Computer-aided semen analysis variables as predictors of male fertility potential. Arch Androl. 1994 Sep-Oct;33(2):93–99. doi: 10.3109/01485019408987809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procopé B. J. Effect of repeated increase of body temperature on human sperm cells. Int J Fertil. 1965 Oct-Dec;10(4):333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe J. M., Schrader S. M., Clapp D. E., Halperin W. E., Turner T. W., Hornung R. W. Semen quality in workers exposed to 2-ethoxyethanol. Br J Ind Med. 1989 Jun;46(6):399–406. doi: 10.1136/oem.46.6.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe J. M., Schrader S. M., Steenland K., Clapp D. E., Turner T., Hornung R. W. Semen quality in papaya workers with long term exposure to ethylene dibromide. Br J Ind Med. 1987 May;44(5):317–326. doi: 10.1136/oem.44.5.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehan N. Semen characteristics of fertile Pakistani men. J Pak Med Assoc. 1994 Mar;44(3):62–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehan N., Sobrero A. J., Fertig J. W. The semen of fertile men: statistical analysis of 1300 men. Fertil Steril. 1975 Jun;26(6):492–502. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)41169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. J., Wyrobek A. J., Ratcliffe J., Gordon L. A., Watchmaker G., Fox S. H., Moore D. H., 2nd, Hornung R. W. Sperm as an indicator of reproductive risk among petroleum refinery workers. Br J Ind Med. 1985 Feb;42(2):123–127. doi: 10.1136/oem.42.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker M. B., Samuels S. J., Perkins C., Lewis E. L., Katz D. F., Overstreet J. W. Prospective surveillance of semen quality in the workplace. J Occup Med. 1988 Apr;30(4):336–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader S. M., Chapin R. E., Clegg E. D., Davis R. O., Fourcroy J. L., Katz D. F., Rothmann S. A., Toth G., Turner T. W., Zinaman M. Laboratory methods for assessing human semen in epidemiologic studies: a consensus report. Reprod Toxicol. 1992;6(3):275–279. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(92)90184-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader S. M., Ratcliffe J. M., Turner T. W., Hornung R. W. The use of new field methods of semen analysis in the study of occupational hazards to reproduction: the example of ethylene dibromide. J Occup Med. 1987 Dec;29(12):963–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader S. M., Turner T. W., Breitenstein M. J., Simon S. D. Longitudinal study of semen quality of unexposed workers. I. Study overview. Reprod Toxicol. 1988;2(3-4):183–190. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(88)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D., Laplanche A., Jouannet P., David G. Within-subject variability of human semen in regard to sperm count, volume, total number of spermatozoa and length of abstinence. J Reprod Fertil. 1979 Nov;57(2):391–395. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0570391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe R. M., Skakkebaek N. E. Are oestrogens involved in falling sperm counts and disorders of the male reproductive tract? Lancet. 1993 May 29;341(8857):1392–1395. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90953-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoorne M., Comhaire F., De Bacquer D. Epidemiological study of the effects of carbon disulfide on male sexuality and reproduction. Arch Environ Health. 1994 Jul-Aug;49(4):273–278. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1994.9937479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoorne M., Vermeulen A., De Bacquer D. Epidemiological study of endocrinological effects of carbon disulfide. Arch Environ Health. 1993 Sep-Oct;48(5):370–375. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1993.9936730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vine M. F., Margolin B. H., Morrison H. I., Hulka B. S. Cigarette smoking and sperm density: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 1994 Jan;61(1):35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch L. S., Schrader S. M., Turner T. W., Cullen M. R. Effects of exposure to ethylene glycol ethers on shipyard painters: II. Male reproduction. Am J Ind Med. 1988;14(5):509–526. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700140503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann L., Isola J., Tuohimaa P. Prognostic variables in predicting pregnancy. A prospective follow up study of 907 couples with an infertility problem. Hum Reprod. 1994 Jun;9(6):1102–1108. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]