Mechanical ventilation is a common lifesaving treatment in ICUs.1 The interaction between patient and ventilator is complex and influenced by various factors, including patient-related factors (eg, effort, demand, and breathing time) and ventilator-related factors (eg, trigger, flow, and volumes). Achieving an optimal patient-ventilator interaction requires diligent investigation and coordination among all of these variables. Patient-ventilator asynchronies, defined as a mismatch between the patient’s demand and the ventilator’s delivery during any phase, are prevalent but often underdiagnosed.2

Liu et al3 in an international prospective observational trial based on a survey of ICU professionals aimed to identify areas for further training and to evaluate factors influencing the ventilator waveform interpretation skills of ICU professionals. Years of ICU experience, profession (with respiratory therapists exhibiting the highest proficiency), highest educational attainment, workplace setting (especially teaching hospitals), and prior training in ventilator waveform interpretation were all correlated with the ability to correctly identify patient-ventilator asynchronies depicted in ventilator waveforms.

Ventilator waveforms provide valuable information on respiratory physiology and patient-ventilator interaction essential for detecting and addressing asynchronies. However, not all professional backgrounds were adept at recognizing certain types of patient-ventilator asynchronies.4-6 Notably, in the survey conducted by Liu et al,3 identifying asynchronies related to triggers, particularly reverse trigger, proved to be challenging. The study underscores the importance of training in accurate waveform interpretation and the adoption of standardized terminology.

One of the pitfalls in the identification of asynchronies is their taxonomy. Mireles-Cabodevila et al7 pointed out that a systematic method is necessary to assess patient-ventilator interactions and a standard nomenclature, not only to ensure that we communicate our findings in a clear and consistent manner but also that our diagnosis and treatment are accurate. Unfortunately, we lack a unified taxonomy.

On the other hand, visual assessment of ventilator waveforms at the bedside may result in an underestimation of patient-ventilator asynchronies due to physicians’ inability to continuously monitor waveforms in real time and insufficient training.8-10 The study’s findings suggest the need for narrowed training and educational programs to broaden ICU staff members’ expertise with ventilator waveforms, hence enhancing patient safety and comfort during mechanical ventilation. A key concern is whether bedside observation alone is suitable for diagnosis or if additional guidance or automated models are required. Recently, Ramírez et al11 demonstrated that a 36-h training program significantly enhanced professionals’ capacity to recognize and treat patient-ventilator asynchronies. Continuous monitoring systems have the potential to strengthen diagnosis. Blanch et al12 advocated the use of continuous monitoring systems to identify ineffective efforts to trigger the ventilator in mechanically ventilated patients, with equivalent accuracy to experienced clinicians. As shown by Pham et al,10 the ability to detect asynchronies, particularly reverse triggering, has significant clinical implications, providing real-time feedback to clinicians. Continuous measurement of reverse triggering assists in optimizing ventilator settings, minimizing sedative requirements, and enhancing patient outcomes.13 Accurate detection of reverse triggering allows clinicians to adjust therapies to mitigate complications such as breath-stacking and diaphragm damage. Recently, de Haro et al14 proposed leveraging existing technologies and using artificial intelligence software to continually identify and properly categorize asynchronies, which are currently underdiagnosed as flow starvation.

Previous research pointed out patient-ventilator asychrony is associated with extended mechanical ventilation, as well as prolonged ICU and hospital length of stay,15,16 whereas the association with mortality is not well established. Double triggering (DT) and flow starvation have been associated with higher incidence of dyspnea and neurocognitive alterations.17,18 However, recent studies suggest that all patient-ventilator asynchronies are not necessarily related to poor outcomes, showing how the asynchrony index may be an important vital sign19 or a high number of clusters of DT and ineffective efforts may be associated with a higher likelihood of ICU survival.20 For example, DT is a potential injurious asynchrony due to breath-stacking and increased strain and stress21 as flow starvation or asynchronies are related with a high inspiratory effort that can be associated with lung injury14 or severe dyspnea.22 On the other hand, reverse triggering with a very low effort could be beneficial as it can provide diaphragmatic training. It is crucial to recognize patient-ventilator asynchronies, particularly those that may be more detrimental, and prioritize efforts to address them.

However, the integration of monitoring and training in modern ICUs should not solely rely on gadgets but also on the knowledge of clinicians and must be tailored to individual patient needs.23 Emphasizing the mechanisms leading to patient-ventilator asynchronies may help us comprehend the underlying processes and devise more tailored treatment strategies.24,25

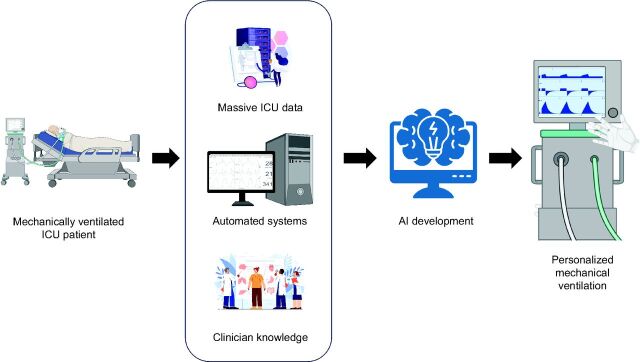

Given what we have learned so far, we must inquire how shall asynchronies manifest themselves in the not too distant future? One potential future impact is the development of more sophisticated ventilator algorithms and technologies to better detect and manage asynchronies. By using sophisticated algorithms, ventilator settings can be dynamically adjusted, enhancing patient-ventilator synchronization and decreasing difficulties. Moreover, the amalgamation of artificial intelligence and machine learning may enable ventilators to perform customized adjustments according to patient-specific respiratory patterns, hence boosting efficiency26,27 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Critically ill patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation in the ICU produce massive clinical data, along with physiological and biological signals such as ventilator waveforms. Achieving personalized mechanical ventilation and patient care requires the integration of vast clinical data with signals and clinicians’ expertise. This integration encompasses the development of automated systems and the utilization of artificial intelligence to enhance the ability of clinicians to detect discrepancies.

Another aspect is the increased focus on patient-centered care. Asynchronies often result in patient discomfort and anxiety, leading to poorer outcomes. In the future, there may be a shift toward ventilator designs that prioritize patient comfort and autonomy. Furthermore, asynchronies highlight the value of multidisciplinary collaboration in critical care. Future health care professional training programs might employ a more holistic approach, encouraging physicians to collaborate closely with respiratory therapists and engineers to optimize mechanical ventilation strategies.28 Dealing with asynchronies in mechanical ventilation will spur innovation in ventilator technology, promote patient-centered care, and encourage interdisciplinary collaboration. These advances hold promise for improving patient outcomes and altering the future of critical care. In line with recent research findings, it is plausible that the data available in today’s medicine can be transformed into tomorrow’s medicine with the appropriate tools.29

Footnotes

Dr Blanch is inventor of a US patent owned by Consorci Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí: “Method and system for managed related patient parameters provided by a monitoring device”, US Patent No. 12/538,940. Dr Blanch owns stock options of BetterCare, a research and development spinoff of Consorci Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí.

See the Original Study on Page 773

REFERENCES

- 1.Peñuelas O, Muriel A, Abraira V, Frutos-Vivar F, Mancebo J, Raymondos K, et al. Inter-country variability over time in the mortality of mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med 2020;46(3):444-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tobin MJ, Jubran A, Laghi F. Patient-ventilator interaction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163(5):1059-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu P, Lyu S, Mireles-Cabodevila E, Miller AG, Albuainain FA, Ibarra-Estrada M, et al. Survey of ventilator waveform interpretation among ICU professionals. Respir Care 2024:11677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correger E, Murias G, Chacon E, Estruga A, Sales B, Lopez-Aguilar J, et al. Interpretación de las curvas del respirador en pacientes con insuficiencia respiratoria aguda. Med Intensiva 2012;36(4):294-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chacón E, Estruga A, Murias G, Sales B, Montanya J, Lucangelo U, et al. Nurses’ detection of ineffective inspiratory efforts during mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care 2012;21(4):e89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mireles-Cabodevila E, de Abreu MG. Classification and quantification of patient-ventilator interactions: we need consensus! Respir Care 2022;67(5):620-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mireles-Cabodevila E, Siuba MT, Chatburn RL. A taxonomy for patient-ventilator interactions and a method to read ventilator waveforms. Respir Care 2022;67(1):129-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colombo D, Cammarota G, Alemani M, Carenzo L, Barra FL, Vaschetto R, et al. Efficacy of ventilator waveforms observation in detecting patient-ventilator asynchrony. Crit Care Med 2011;39(11):2452-2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akoumianaki E, Lyazidi A, Rey N, Matamis D, Perez-Martinez N, Giraud R, et al. Mechanical ventilation–induced reverse-triggered breaths: a frequently unrecognized form of neuromechanical coupling. Chest 2013;143(4):927-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pham T, Montanya J, Telias I, Piraino T, Magrans R, Coudroy R, et al. ; BEARDS study investigators. Automated detection and quantification of reverse triggering effort under mechanical ventilation. Crit Care 2021;25(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramírez II, Gutiérrez-Arias R, Damiani LF, Adasme RS, Arellano DH, Salinas FA, et al. Specific training improves the detection and management of patient-ventilator asynchrony. Respir Care 2024;69(2):166-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanch L, Sales B, Montanya J, Lucangelo U, Oscar GE, Villagra A, et al. Validation of the Better Care system to detect ineffective efforts during expiration in mechanically ventilated patients: a pilot study. Intensive Care Med 2012;38(5):772-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellado Artigas R, Damiani LF, Piraino T, Pham T, Chen L, Rauseo M, et al. Reverse triggering dyssynchrony 24 h after initiation of mechanical ventilation. Anesthesiology 2021;134(5):760-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Haro C, Santos-Pulpón V, Telías I, Xifra-Porxas A, Subirà C, Batlle M, et al. ; BEARDS study investigators. Flow starvation during square flow–assisted ventilation detected by supervised deep learning techniques. Crit Care 2024;28(1):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thille AW, Rodriguez P, Cabello B, Lellouche F, Brochard L. Patient-ventilator asynchrony during assisted mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med 2006;32(10):1515-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Wit M, Miller KB, Green DA, Ostman HE, Gennings C, Epstein SK. Ineffective triggering predicts increased duration of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2009;37(10):2740-2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt M, Banzett RB, Raux M, Morélot-Panzini C, Dangers L, Similowski T, et al. Unrecognized suffering in the ICU: addressing dyspnea in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med 2014;40(1):1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albaiceta GM, Brochard L, Dos Santos CC, Fernández R, Georgopoulos D, Girard T, et al. The central nervous system during lung injury and mechanical ventilation: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth 2021;127(4):648-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rué M, Andrinopoulou ER, Alvares D, Armero C, Forte A, Blanch L. Bayesian joint modeling of bivariate longitudinal and competing risks data: an application to study patient-ventilator asynchronies in critical care patients. Biom J 2017;59(6):1184-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magrans R, Ferreira F, Sarlabous L, López-Aguilar J, Gomà G, Fernandez-Gonzalo S, et al. ; ASYNICU group. The effect of clusters of double triggering and ineffective efforts in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2022;50(7):E619-e629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Haro C, López-Aguilar J, Magrans R, Montanya J, Fernández-Gonzalo S, Turon M, et al. ; Asynchronies in the Intensive Care Unit (ASYNICU) Group. Double cycling during mechanical ventilation: frequency, mechanisms, and physiologic implications. Crit Care Med 2018;46(9):1385-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demoule A, Decavele M, Antonelli M, Camporota L, Abroug F, Adler D, et al. Dyspnea in acutely ill mechanically ventilated adult patients: an ERS/ESICM statement. Intensive Care Med 2024;50(2):159-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esperanza JA, Sarlabous L, de Haro C, Magrans R, Lopez-Aguilar J, Blanch L. Monitoring asynchrony during invasive mechanical ventilation. Respir Care 2020;65(6):847-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subirà C, de Haro C, Magrans R, Fernández R, Blanch L. Minimizing asynchronies in mechanical ventilation: current and future trends. Respir Care 2018;63(4):464-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Haro C, Ochagavia A, López-Aguilar J, Fernandez-Gonzalo S, Navarra-Ventura G, Magrans R, et al. ; Asynchronies in the Intensive Care Unit (ASYNICU) Group. Patient-ventilator asynchronies during mechanical ventilation: current knowledge and research priorities. Intensive Care Med Exp 2019;7(Suppl 1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulqueeny Q, Redmond SJ, Tassaux D, Vignaux L, Jolliet P, Ceriana P, et al. Automated detection of asynchrony in patient-ventilator interaction. In: Proceedings of the 31st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society: Engineering the Future of Biomedicine, EMBC 2009. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, 2009:5324-5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakkes T, van Diepen A, De Bie A, Montenij L, Mojoli F, Bouwman A, et al. Automated detection and classification of patient–ventilator asynchrony by means of machine learning and simulated data. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2023;230:107333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maslove DM, Tang B, Shankar-Hari M, Lawler PR, Angus DC, Baillie JK, et al. Redefining critical illness. Nat Med 2022;28(6):1141-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halpern NA. Innovative designs for the smart ICU. Chest 2014;145(3):646-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]