Abstract

We previously reported that Daudi cells, a Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line, were capable of supporting productive infection of hepatitis C virus (HCV). During continual cultivation after HCV infection, the culture became resistant to interferons (IFNs). This resistant cell line, coded as H-903, was used as host cells for replication of GB virus C (GBV-C), also known as hepatitis G virus. GBV-C RNA was detected in the culture by reverse transcription-PCR for more than 130 days after inoculation, while it was detected for 44 days but not later in the parental IFN-sensitive Daudi cells. Productive infection of GBV-C in the H-903 system was confirmed by serially inoculating supernatants from infected cultures into uninfected cells. The viral E2 antigen was detected by immunofluorescence in the cells inoculated with the fifth passage of GBV-C. The presumed capsid-coding region of the viral genome in the inoculum, in the serially passaged virus, or in the virus produced by a long-term culture was only 16 amino acids long, suggesting that the GBV-C with a short core sequence was replication competent.

GB virus C (GBV-C) (14), also called hepatitis G virus (7), was discovered during searches for etiologic agents of human non-A to non-E hepatitis. GBV-C produced persistent infection with viremia and could be transmitted by transfusion, but its pathogenic potential in liver disease is unclear at present (1).

GBV-C possessed a positive single-stranded RNA, approximately 9.4 kb, which contained a single long open reading frame of approximately 2,900 amino acids. Sequence analysis of the viral genome revealed that GBV-C was a member of the Flaviviridae family and that hepatitis C virus (HCV) was the closest known relative. However, in contrast to HCV, the core region at the N terminus of the GBV-C polyprotein was often too short to encode a core protein (15). It should, therefore, be determined whether GBV-C with such a small core protein could actually replicate.

In attempting to develop an in vitro culture system of GBV-C, we tested an interferon (IFN)-resistant Daudi cell line for its capacity for GBV-C replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

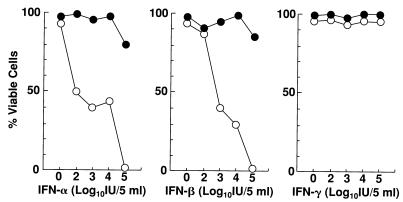

Daudi cells were originally purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). They are a nonproducer Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive cell line and are highly sensitive to IFN-α and IFN-β. During long-term cultivation after inoculation with HCV (9), the cells became resistant to IFNs (Fig. 1). This resistant culture, H-903, was used in the present study as host cells for GBV-C. HCV RNA was not detectable by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR in the cells at the time of use. The cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 8% fetal bovine serum and 1% kanamycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

FIG. 1.

The sensitivity of H-903 and Daudi ATCC cells to IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ. The cells were cultured for 2 weeks in the medium containing various concentrations of IFNs. The cell viability was determined by the dye exclusion test. ●, H-903 cells; ○, Daudi ATCC cells.

Virus.

Three human plasmas containing GBV-C (no. 53, 42, and 03) were used as inocula. They also contained HCV. The viruses in these plasmas had previously been examined for binding with antibodies by immunoprecipitation with anti-human immunoglobulins (3). In the test, 1 μl of each (undiluted) plasma was mixed with 100 μl of undiluted goat anti-human immunoglobulin (Cappel, Durham, N.C.), incubated at 4°C overnight, centrifuged at 680 × g for 15 min, and separated into supernatant and pellet. Both supernatant and pellet were diluted in 10-fold increments and tested for GBV-C or HCV RNA by RT-PCR. The ratio of GBV-C virions immunoprecipitated to those that were not was 1:1 for no. 53 and 03 and 10:1 for no. 42. The ratio of HCV virions immunoprecipitated to those that were not was 100:1 for no. 53 and 42 and 10:1 for no. 03. The RT-PCR titers of GBV-C by limiting dilution were 106/ml for no. 53 and 42 and 105/ml for no. 03. The titers of HCV were 105/ml for no. 53 and 42 and 104/ml for no. 03.

Virus inoculation.

One milliliter of the suspension containing 5 × 105 cells was mixed with 100 μl of each inoculum and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After being washed, the cells were suspended in 5 ml of the medium and cultured at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator. After 1 week of culture, cells were subcultured twice a week with a split ratio of 1:3. Cell suspensions were harvested at intervals during the culture period, and 250 μl of the cell and medium mixture was tested for the presence of viral RNA by RT-PCR.

RT-PCR.

RNA extraction, RT, and a two-step PCR with nested primers for detection of the GBV-C and HCV genomes were carried out as described in a previous report (10). The primers were synthesized on the basis of the published sequence of GBV-C (database accession no. U36380). To detect the 5′ noncoding-short core-E1 region of the GBV-C genome, we used primer sets G5 (5′-CCCACGTACGGTCCACGTCG-3′; nucleotide numbers 304 to 323) and G18 (5′-CTGGGCGGCGGACTTGCCGGG-3′; nucleotide numbers 770 to 749) as an external pair and G6 (5′-CGAGTTGACAAGGACCAGTG-3′; nucleotide numbers 361 to 380) and G17 (5′-CAAACCCGCCTGATACAGTGG-3′; nucleotide numbers 740 to 719) as an internal pair. Primers sets for detection of the NS3 region were A (5′-ATCCGGCGGTGCGGAAAGGG-3′; nucleotide numbers 3228 to 3248) and D (5′-CTTGGGTTAAGGGCCCCCAC-3′; nucleotide numbers 3443 to 3413) as an external pair and B (5′-GTCACAAAGGCTGCCTTGAC-3′; nucleotide numbers 3258 to 3278) and C (5′-ATGGTTCGGGAAGAAGCCCC-3′; nucleotide numbers 3403 to 3383) as an internal pair. Detection of the negative strand of GBV-C RNA was carried out with primers for the NS3 region of the viral genome by rTth-based RT-PCR with thermostable rTth reverse transcriptase (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.), according to the method described by Laskus et al. (6). The HCV genome was detected by RT-PCR amplification of the 5′ noncoding region (nucleotide numbers 63 to 301) as previously described (8). RT-PCR products were subcloned into pBluescript SK(+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and sequenced by using an ABI 373A sequencer with a Taq dye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer).

Immunofluorescence.

Immunofluorescence was performed by an indirect method by using a mouse monoclonal antibody against GBV-C E2 protein, which was kindly supplied by I. A. Mushawar of Abbott Diagnostics (Chicago, Ill.). Following fixation with cold acetone for 3 min, cells were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with the anti-GBV-C E2 purified immunoglobulin G solution at a concentration of 7 μg/ml. After being washed, cells were incubated for 1 h with a 1:100 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

RESULTS

Figure 1 compares the sensitivity of H-903 and parental Daudi ATCC cells to IFNs. Five milliliters of the suspension containing 5 × 105 cells was cultured in the absence or presence of IFN-α, IFN-β, or IFN-γ at a concentration of 102, 103, 104, or 105 IU/5 ml. After 2 weeks of culture, viable cells were counted by dye exclusion. While all of the Daudi ATCC cells were killed at a concentration of 105 IU/5 ml of IFN-α or IFN-β, more than 80% of the H-903 cells survived. IFN-γ did not affect the viability of either group of cells. As the HCV infection of the Daudi cells induced the production of IFNs and partial cell killing (9), it was considered that the H-903 cells were mutant cells which survived the endogenously induced IFNs. Expression of the EBV antigen in both cell lines was tested by immunofluorescence with anti-EBV gp250/350 antibody (Biodesign, Huntington Beach, Calif.). There were more antigen-positive cells in H-903 cells than in the parental Daudi ATCC cells.

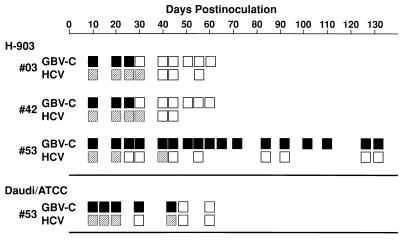

The H-903 cells were examined for suitability for GBV-C replication. Figure 2 shows detection of viral RNA by RT-PCR in the samples obtained at intervals from the cultures inoculated with plasma no. 53, 42, or 03. In cultures inoculated with plasma no. 03 or 42, the GBV-C genome was detected for 25 days but not later. In the culture inoculated with plasma no. 53, the GBV-C genome persisted for up to 130 days. Plasma no. 53 and 42 contained larger amounts of GBV-C virions than plasma no. 03 (106/ml versus 105/ml), and plasma no. 53 and 03 contained antibody-free virions in a higher proportion than plasma no. 42 (10:1 versus 1:1) (see Materials and Methods) (3). Therefore, plasma no. 53 must have contained a higher amount of GBV-C virions which were free from antibodies than plasma no. 42 and 03. This may be responsible for the phenomenon that only plasma no. 53 was able to establish the infection. HCV, which was mostly present as an immunocomplex in all of these inocula, became undetectable on day 41 for plasma no. 03 and 42 and on day 45 for plasma no. 53. It never became positive later. When plasma no. 53 was inoculated into parental IFN-sensitive Daudi ATCC cells, GBV-C RNA remained for only 44 days, suggesting that H-903 cells supported GBV-C replication more consistently than Daudi ATCC cells. The experiment with plasma no. 53 was repeated with the H-903 cells. GBV-C RNA was again detected in the cells for up to 250 days. The cells harvested on days 127, 132, and 250 were positive for the negative strand of GBV-C RNA, as determined by rTth-based RT-PCR, which was reportedly strand specific (6). Detection of GBV-C RNA in the culture supernatant was intermittent. The titer of the GBV-C genome in the supernatant harvested on day 48 was 102/ml by endpoint dilution RT-PCR. HCV RNA was not detectable in the samples taken later than 50 days postinoculation.

FIG. 2.

Detection of GBV-C RNA and HCV RNA in the cell supernatant mixtures harvested at intervals from the cultures inoculated with plasma no. 53, 42, or 03. The GBV-C genomes were detected by RT-PCR with the nested primer pairs A and D and B and C for detection of the NS3 region of the viral genome. For HCV, the 5′ noncoding region (nucleotide numbers 63 to 301) was detected. ■, positive for the GBV-C genome; ▨, positive for the HCV genome; □, negative for either the GBV-C or HCV genome.

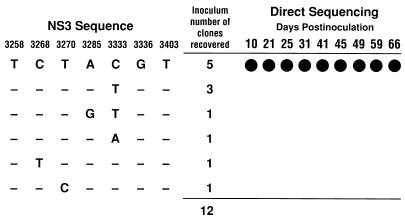

Our previous study revealed that only specific subsets of HCV in the inoculum could replicate well in the lymphocyte cell lines HPBMa10-2 and Daudi (8). To know if a similar phenomenon was observed for GBV-C, we examined sequences of the NS3 region of the viral genome recovered at various times from the infected H-903 culture. Inoculum no. 53, which was able to persist in the culture, was subjected to RT-PCR. Among 12 RT-PCR-amplified clones examined, 6 different clones were detected. We examined the samples from the cell culture by direct sequencing, which was supposed to detect the major sequence in the sample. As shown in Fig. 3, the sequence present as a majority in the inoculum but not others persisted in the cell culture.

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence of the GBV-C NS3 region (nucleotide numbers 3258 to 3403) recovered from inoculum no. 53 and from the infected H-903 cells. Nucleotides which showed sequence variabilities are shown. Dashes (left side of the panel) indicate nucleotides identical to those shown at the top. Solid circles (right side of the panel) indicate the sequence detected by direct sequencing in the samples collected at various times from the H-903 culture.

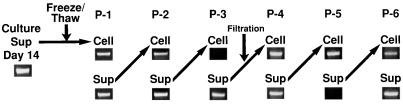

In order to determine whether the system is productive for infectious GBV-C, we examined cell-free virus transmission. The supernatant was collected from an infected H-903 culture 2 weeks after inoculation with plasma no. 53 and then was frozen at −80°C to destroy the viable cells. After thawing, 3 ml of the supernatant was mixed with 2 ml of a suspension containing 5 × 105 fresh uninfected H-903 cells, and the mixture was cultured for 1 week. This procedure was repeated five more times by omitting the freezing process. At the fourth passage, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter. One-week-old cultures were tested for the presence of GBV-C RNA by RT-PCR with nested primers detecting the NS3 or the 5′ noncoding-core-E1 region. As shown in Fig. 4, GBV-C in the supernatants could be transmitted serially to the uninfected cells, i.e., the infected H-903 cells released the infectious GBV-C virions into the medium.

FIG. 4.

Serial passages of GBV-C in H-903 cells. The supernatant collected from the infected H-903 culture on day 14 was freeze-thawed and inoculated into fresh uninfected cells. After 1 week of culture, the supernatant was again inoculated into uninfected cells. This procedure was repeated five times. The presence of GBV-C RNA in the cells and supernatants was examined by RT-PCR detecting the NS3 region with the nested primer pairs A and D and B and C or the 5′ noncoding-core-E1 region with the nested primer pairs G5 and G18 and G6 and G17. The supernatant was freeze-thawed before P-1 and filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter before P-4. P, passage; Sup, supernatant.

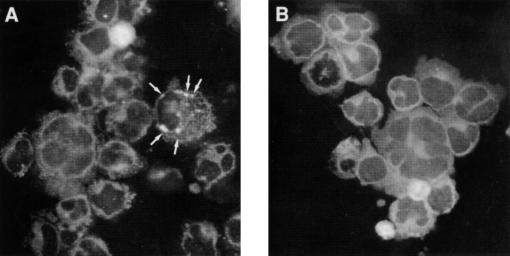

The H-903 cells infected with the fifth passage of GBV-C were examined for the presence of the viral antigen by immunofluorescence with a mouse monoclonal anti-GBV-C E2 antibody. Positive reactions were observed in approximately 5% of the cells. The immunofluorescent staining was granular and located in the perinuclear region of the cytoplasm (Fig. 5). It was interesting to note that the localization of the GBV-C E2 antigen was different from that of the HCV envelope or core antigen observed in a previous study (11). While GBV-C E2 antigens were detected perinuclearly, the HCV antigens had been found in the periphery of the cytoplasm.

FIG. 5.

Indirect immunofluorescent staining with a mouse monoclonal antibody to GBV-C E2 protein. (A) Positive reactions (arrows) in a H-903 cell infected with the fifth passage of the virus; (B) lack of reaction without the antibody.

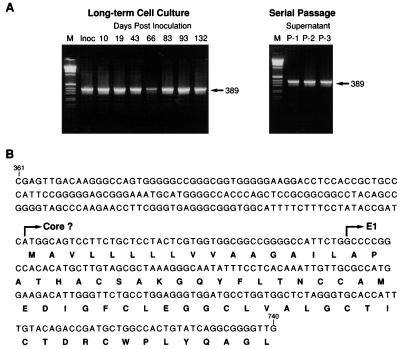

The size and nucleotide sequence of the 5′ noncoding-core-E1 region of GBV-C were reported to be quite variable among the isolates. Using primers detecting this region, we compared the size of the RT-PCR signals detected for inoculum plasma no. 53 with those for the samples taken on days 10, 19, 43, 66, 83, 93, and 132 from the infected H-903 culture. The signals for supernatants P-1, P-2, and P-3 from the serial passage experiment (shown in Fig. 4) were also examined. All of the RT-PCR products which were obtained by using primer pairs G5 and G18 and G6 and G17 had the same size (Fig. 6A). Sequencing of these products revealed that all of the recovered sequences were the same and that there were only 16 amino acids present between the conserved initiation codon for the polyprotein and the start of the E1 region (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

(A) Size of the RT-PCR products obtained with primer pairs G5 and G18 and G6 and G17, which detected the 5′ noncoding-core-E1 region of the GBV-C genome. The left side of the figure shows the data for inoculum plasma no. 53 and the samples taken from the infected continuous H-903 culture. The right side of the figure shows the data for the samples from the serial passages. (B) Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the PCR-amplified DNA. All the products from inoculum plasma no. 53, the infected H-903 culture, and the serial passages shown in panel A had the same sequence. M, size marker; Inoc, inoculum.

DISCUSSION

The Burkitt’s lymphoma-derived IFN-resistant Daudi cells, H-903, were able to support GBV-C replication; the viral genome persisted in the cells for up to 250 days. Productive infection of GBV-C in this system was demonstrated by serial inoculation of the culture supernatants to the uninfected cells. The level of the GBV-C replication in H-903 cells was comparable to that of HCV in lymphocytic cells (9); the titer of the GBV-C genome in the supernatants was 102/ml by endpoint dilution RT-PCR.

The IFN-resistant H-903 cells supported the replication of GBV-C better than the parental Daudi ATCC cells. As the difference could be due to different cellular responses to GBV-C infection in producing endogenous IFN, we tested by immunofluorescence the H-903 cells infected with GBV-C for the appearance of the IFN-inducible p44 protein which had previously been reported as a host response to IFN induced by HCV infection (12), and the cells were negative. Thus, we assume that unlike HCV, GBV-C is not an IFN inducer. The reason why H-903 cells could support GBV-C infection better than parental Daudi ATCC cells is not fully understood at the moment. It is possible that since the H-903 cells became more stable and resistant to various conditional stresses, including IFNs, this could have been an advantage for the survival of the virus.

The transient detection of HCV RNA in the H-903 culture was probably due to carried-over HCV because the immunoprecipitation indicated that HCV virions in plasma no. 53 were bound to antibodies, and such an immune complex was previously shown to be prevented from establishing the infection (4). It should be mentioned that previous studies showed that the antibody-bound HCV virions were adsorbed by Daudi cells but were unable to establish infection (13). When HPBMa10-2 cells (a human T-cell line) were used, only the antibody-free HCV virions were adsorbed by the cells; the antibody-bound HCV virions were not (4). In this connection, the GBV-C genomes in inoculum no. 03 and 42 which persisted in culture for about 25 days but not longer were probably carried-over genomes and not the ones which replicated.

Of interest, the GBV-C genome which persisted in the H-903 culture as well as the viral genome recovered from serial passages had only 16 amino acids in front of the hydrophobic leader sequence of the E1 region; it was not a sequence characteristic of the nucleocapsid protein of flaviviruses. The result suggested that the GBV-C, with such a short core sequence, was replication competent and infectious. However, it remains to be investigated whether GBV-C virions actually lacked the core protein or utilized a cellular protein or a core protein borrowed from other coexisting viruses.

The GBV-C genome in the infected individual was much less heterogeneous than HCV. Nevertheless, a certain extent of heterogeneity was observed in the NS3 region. When the NS3 regions were sequenced and compared, GBV-C, which persisted in cell culture, was the one present as a majority in the inoculum. This is in contrast to HCV; HCV, which was present only as a minority, was able to replicate in the lymphocyte cell lines (8). This may suggest that GBV-C was essentially a lymphotropic virus. Actually, Fogeda et al. recently reported that human peripheral blood mononuclear cells could be infected with GBV-C (hepatitis G virus) (2). Transient persistence of the virus in MT-2 cells, a human T-cell line, has also been reported (5).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid to H.Y. from the Ministry of Health and Welfare for a comprehensive 10-year strategy for cancer control.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alter H L. The incidence of transfusion-associated hepatitis G virus infection and its relation to liver diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:747–754. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703133361102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fogeda M, Navas S, Martin J, Casqueiro M, Rodriguez E, Arocena C, Carreno V. In vitro infection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by GB virus C/hepatitis G virus. J Virol. 1999;73:4052–4061. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4052-4061.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hijikata M, Mishiro S. Circulating immune complexes that contain HCV but not GBV-C in co-infected hosts. Int Hepatol Commun. 1996;5:339–344. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hijikata M, Shimizu Y K, Kato H, Iwamoto A, Shih J W, Alter H J, Purcell R H, Yoshikura H. Equilibrium centrifugation studies of hepatitis C virus: evidence for circulating immune complexes. J Virol. 1993;67:1953–1958. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1953-1958.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikeda M, Sugiyama K, Mizutani T, Tanaka T, Tanaka K, Shimotohno K, Kato N. Hepatitis G virus replication in human cultured cells displaying susceptibility to hepatitis C virus infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:505–508. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laskus T, Radkowski M, Wang L F, Vargas H, Rakela J. Lack of evidence for hepatitis G virus replication in the livers of patients coinfected with hepatitis C and G viruses. J Virol. 1997;71:7804–7806. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7804-7806.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linnen J, Wages J, Zhang-Keck Z Y, Fry K E, Krawczynski K Z, Alter H J, Koonin E, Gallagher M, Alter M, Hadziyannis S, Karayiannis P, Fung K, Nakatsuji Y, Shih J W-K, Young L, Piatak M, Jr, Hoover C, Fernandez J, Chen S, Zou J C, Morris T, Hyams K C, Ismay S, Lifson J D, Hess G, Foung S H, Thomas H, Bradley D, Margolis H, Kim J P. Molecular cloning and disease association of hepatitis G virus: a transfusion-transmissible agent. Science. 1996;271:505–508. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakajima N, Hijikata M, Yoshikura H, Shimizu Y K. Characterization of long-term cultures of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 1996;70:3325–3329. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3325-3329.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimizu Y K, Yoshikura H. In-vitro systems for the detection of hepatitis C virus infection. Viral Hepatitis Rev. 1995;1:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu Y K, Purcell R H, Yoshikura H. Correlation between the infectivity of hepatitis C virus in vivo and its infectivity in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6037–6041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu Y K, Feinstone S M, Kohara M, Purcell R H, Yoshikura H. Hepatitis C virus: detection of intracellular virus particles by electron microscopy. Hepatology. 1996;23:205–209. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu Y K, Oomura M, Abe K, Uno M, Yamada E, Ono Y, Shikata T. Production of antibody associated with non-A, non-B hepatitis in a chimpanzee lymphoblastoid cell line established by in vitro transformation with Epstein-Barr virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2138–2142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.7.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu Y K, Igarashi H, Kiyohara T, Cabezon T, Farci P, Purcell R H, Yoshikura H. A hyperimmune serum against a synthetic peptide corresponding to the hypervariable region 1 of hepatitis C virus can prevent viral infection in cell culture. Virology. 1996;223:409–412. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simons J N, Leary T P, Dawson G J, Pilot-Matias T J, Muerhoff A S, Desai S M, Mushahwar I K. Isolation of novel virus-like sequences associated with human hepatitis. Nat Med. 1995;1:564–569. doi: 10.1038/nm0695-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simons J N, Desai S M, Schultz D E, Lemon S M, Mushahwar I K. Translation initiation in GB viruses A and C: evidence for internal ribosome entry and implications for genome organization. J Virol. 1996;70:6126–6135. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6126-6135.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]