Abstract

Incomplete neurological awakening manifested as aberrant patterns of electroencephalography (EEG) at emergence may be responsible for an unresponsive patient in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). We describe a case of an individual who remained unresponsive but awake in the PACU. Retrospective, intraoperative EEG analysis showed low alpha power and a sudden shift from deep delta to arousal preextubation. We explored parallels with diminished motivation disorders and anesthesia-induced sleep paralysis due to imbalances in anesthetic drug sensitivity between brain regions. Our findings highlight the relevance of end-anesthesia EEG patterns in diagnosing delayed awakening.

An unresponsive patient in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) poses a challenging situation for any anesthesiologist, especially when the patient appears to be hemodynamically stable. It is essential to promptly exclude life-threatening and reversible causes of unresponsiveness, insufficient neurological recovery, and potential drug overdose.1,2 Rare causes, such as genetic-based variation in anesthetic sensitivity3 and disorders of reduced motivation can be considered subsequently.4–6 However, little is known about the role of pathological electroencephalogram (EEG) patterns in neurological awakening.

We describe the case of an individual enrolled in the AlphaMax study who remained unresponsive but awake for an extended period in the PACU.7 The AlphaMax study (a prospective randomized controlled trial) involved adults over 60 years scheduled to undergo surgery. Participants were randomized to EEG-guided dose titration (alpha maximization) or standard fentanyl-desflurane anesthesia. A second arm of the study randomized participants to receive propofol before emergence or volatile anesthetic. The primary aim of the study was to determine if either of these interventions improved cognitive outcomes postoperatively.

The study was approved by the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee (17/NTA/56). The patient gave written informed consent for participation in the study and for the publication of this case report. This article adheres to the applicable EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research) guidelines.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 78-year-old female, American Society of Anesthesiologists grade 2, underwent laminar decompression under general anesthesia. She had controlled essential hypertension and quit smoking 25 years ago. Her regular medications included simvastatin, quinapril, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol, and aspirin, with reported sulfonamide and penicillin allergies. She had no prior anesthesia complications. Preoperative reports of blood urea nitrogen, serum electrolytes, and an electrocardiogram (ECG) were normal. Intraoperative monitoring included continuous ECG, noninvasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, capnography, and peripheral temperature measurements. After preoxygenation, tracheal intubation was facilitated with fentanyl, propofol, and rocuronium. Anesthesia was performed as per the AlphaMax study protocol,7 and the frontal EEG was recorded for future analysis. She was randomized into the control group for alpha maximization and to receive a rapid infusion (40 mL/h, 193 mg over 29 minutes) of propofol near the end of the surgery. A dose of 40 mL/h was selected to achieve an effect-site concentration of 1 to 2 µg/mL and a total dose of 1 to 3 mg/kg, consistent with effective doses in prior pediatric studies.7 Her intraoperative course was uneventful. The surgery lasted 140 minutes. After neuromuscular blockade reversal, she opened her eyes to loud, repeated commands and demonstrated purposeful motor activity (coughing, arm movement). She was then extubated in the operating room and transferred to the PACU.

However, she failed to respond to verbal cues in the PACU, but her vital signs remained stable, with a heart rate of 65 beats per minute, blood pressure of 122/68 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 98% while receiving supplemental oxygen at 4 L/min. Neuromuscular function was assessed using the train of four ratio, which was greater than 0.9. After ensuring that her airway, breathing, and circulation were intact, a detailed neurological examination was conducted, along with laboratory tests to check for electrolyte and blood sugar concentrations. The neurological examination revealed no focal deficits, rigidity, or abnormal posturing. Her pupils were reactive to light, but with a glassy-eyed stare. She remained unresponsive to noxious stimuli and did not resist eye-opening. Oxygen was supplemented via nasal prongs at 2 L/min, as per PACU protocol, since her room air saturation was between 92% and 94%, and airway assist maneuvers were met with resistance. Her ventilatory rate remained constant at 8 to 10 breaths per minute. Intravenous naloxone was administered. A computed tomography scan was in the process of being initiated. The anesthetic chart and preoperative assessment were reviewed to rule out drug interactions, concomitant medical pathology, and prior psychiatric illness. She had no history of sleep issues, sleepwalking, psychiatric medication use, or anxiety. Neurologically, she had been symptom-free for years, with a past bout of vertigo and a singular episode of syncope. The differential diagnoses, investigations, and treatment pathways for postoperative unresponsiveness are displayed in Tables 1 and 2. After 90 minutes in the PACU, she gradually responded to her caregiver. Over the next half an hour, she continued to be more responsive and was transferred out of the PACU when she was considered adequately awake.

Table 1.

Causes for Delayed Arousal After Anesthesia

| Examples | Symptoms or diagnosed by | Management | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs | |||

| Pharmacokinetic | Drug dose: Opioids, neuromuscular blockers, and benzodiazepines. |

Pinpoint pupils, ventilatory rate, neuromuscular function monitoring: train of four ratio (TOFR) | Intravenous naloxone, neostigmine, and sugammadex flumazenil |

| Impaired transport or distribution, metabolism and elimination problems: •Hepatic failure •Renal failure •Hypothyroidism Hypothermia |

Preoperative investigations: Liver function test Renal function test Thyroid function test Core temperature |

Review history from the preoperative assessment, for example, age, weight, and comorbidities. | |

| Pharmacodynamic | Genetic variation | Cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) is involved in propofol metabolism.1 Prior history of delayed wake-up after surgery. | Modify the anesthetic plan in future surgeries. |

| Increased sensitivity due to age | |||

| Chronic pharmacotherapy and drug interactions | Benzodiazepines, barbiturates, anticholinergics, antidepressants, antipsychotics | Preoperative assessment review | |

| Metabolic causes | Hypoglycemia Hyperglycemia Hyponatremia Hypernatremia Acidosis |

Laboratory tests, ABG | Treat as recommended |

| Endocrine causes | Myxedema coma | Hypothermia, coma, bradycardia, hypercarbia and hyponatremia. Thyroid function test. Previous history of hypothyroidism2 |

Intravenous thyroxine |

| Surgery and anesthesia-related complications | Total spinal anesthesia Type of surgery |

Hypotension, dilated pupils | Reintubation, sedation surgical consult |

Abbreviations: ABG, arterial blood gas; PACU, postanesthesia care unit; TOFR, train of four ratio.

Table 2.

Neurological and Psychiatric Causes for Delayed Arousal After Anesthesia

| Examples | Symptoms or features used for diagnosis | Clinical features of our patient |

|---|---|---|

| Neurological causes | ||

| Stroke | ||

| 1. Brainstem stroke, for example, locked-in-syndrome (bilateral pontine lesions and destruction of pontine motor tracts). |

Paralysis of limbs and oral structures with retained alertness and cognitive abilities. Upward gaze and eye blinking are preserved and can be used to assess consciousness and cognition.14 |

Completely unresponsive to verbal commands Did not appear alert No upward gaze No eye blinking |

| 2. Frontal lobe stroke, for example, disorders of diminished motivation: akinetic mutism or abulia (unilateral or bilateral lesions of the superior mesial region of the frontal lobe). |

No attempt to communicate, a noncommunicative facial expression. Movements limited to eye tracking and arm and body movements for specific tasks. Intact brainstem reflexes. |

No arm and body movements. No eye tracking |

| 3. Global stroke, for example, isolated global aphasia (large ischemic or hemorrhagic injuries in the left frontal, temporal, and parietal areas). |

Alert but unable to communicate verbally, able to perform meaningful tasks | Not alert. No attempt to communicate |

| Seizure (nonconvulsive status epilepticus) | No clinical tonic-clonic convulsions. Usually, results from underlying hypoxic brain injury, post cardiac arrest. EEG evidence of uncontrolled seizure activity, prolonged periods of unresponsiveness or alertness alternating with stupor |

No seizure-like convulsions EEG was not done in PACU. No change in lack of response over time |

| Central anticholinergic syndrome (CAS) | Confusion, hallucination, dilated pupils, tachycardia, dry mouth. Managed with intravenous physostigmine |

No clinical features of CAS |

| Psychiatric causes | ||

| Conversion disorder | Unresponsiveness, apparent coma Emotional precipitant before onset, history of similar presentations |

No history of emotional precipitant |

| Catatonia Mood disorders, schizophrenia Medical causes (SDH, HIV and encephalopathy) |

Muscular rigidity, immobility, echopraxia and echolalia, mutism, staring, and repeated movements, may be unresponsive. Preserved brainstem reflexes. Trial of intravenous benzodiazepines |

No consistent neurological signs. |

| Sleep paralysis Narcolepsy, prior episodes of sleep paralysis |

Glassy-eyed stare, unresponsive to verbal commands or noxious stimuli, no mechanical airway obstruction. Trial of intravenous physostigmine.15 | No history of narcolepsy or previous episode of sleep paralysis. Matching clinical presentation of our case report. |

| Malingering Intentional creation of symptoms for secondary gain. |

Inconsistencies in behavior, avoidance of noxious stimuli, previous history of malingering | Consistent unresponsiveness |

Abbreviations: DDM, disorders of diminished motivation; EEG, electroencephalography; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PACU, postanesthesia care unit; SDH, subdural hematoma.

Following up with her the next day, she recounted the episode in the PACU, claiming to have been awake the whole time but unable to move or speak. She recalled people trying to open her eyes and thinking she needed to inform the study coordinator about this incident. She did not seem upset or adversely affected by the experience.

Her postoperative course was complicated by a chest infection for which she had an extended stay in the hospital. We followed up 1 and 2 years later to ask about the same hospital visit. She failed to remember anything from the PACU, but she mentioned having an out-of-body experience at some point after her surgery. “I remember dreaming I was in a white or bright room, and I was floating in the room and looking down on my body. I thought I was going to die. I was not frightened, and the dream was not unpleasant.”

A retrospective analysis of her intraoperative EEG and drug concentrations was performed to explain the PACU presentation (Analysis details, Supplemental Digital Content 1: Supplemental Document 1, http://links.lww.com/AACR/A528). Her desflurane, fentanyl, and propofol concentrations immediately before extubation were below sedative levels (fentanyl: 0.8 ng/mL, desflurane estimated effect-site concentration: 0.2%, propofol: 1 µg/mL). Propofol administered at the end had been stopped 8 minutes before extubation.

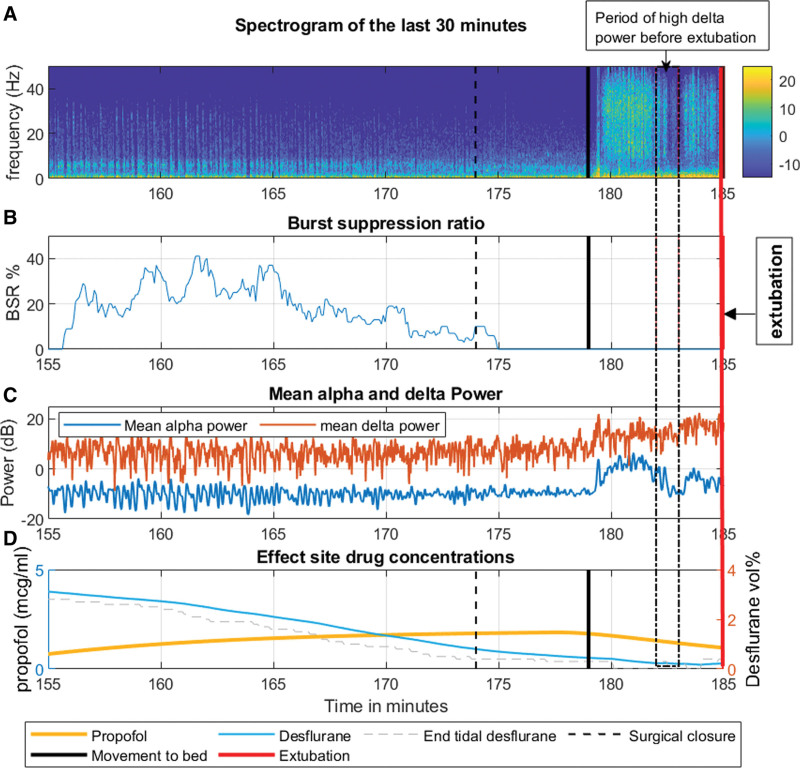

The Figure displays noteworthy features of her intraoperative EEG in the last 30 minutes (155–185 minutes). These include a consistently low alpha power, burst suppression 10 minutes before extubation, and a constant delta power from 155 to 179 minutes despite decreasing drug concentrations. Although the EEG beyond 179 minutes had electromyography activity, we identified intermittent periods without muscular activity-related noise, characterized by delta waves whose power was unchanged (or even increased) from the previous 30 minutes (Supplemental Digital Content 2: Supplemental Figures 1–3, http://links.lww.com/AACR/A529, provide a look at delta power over a 1-minute segment during this period).

Figure.

Interesting features of the patients intraoperative EEG and drug concentrations during the last 30 minutes. A: Spectrogram for the last 30 min of the case (155–185 min). The spectrogram was computed using the multitaper method in the Chronux toolbox, and the resulting spectrum was converted to decibels (dB). B: Burst suppression ratio, recorded directly from the Entropy module. C: Alpha power is in blue and delta power is in red. There was no decrease in the delta power in the last 5 min. D: Propofol and desflurane effect-site concentration after fast infusion of propofol at the end of the surgery. Propofol effect-site concentrations were calculated based on a 2-compartment model and desflurane concentrations were calculated from end-tidal measurements assuming a rate constant keo =0.0048/s (Supplemental Digital Content, Supplemental Document 1, http://links.lww.com/AACR/A528, provides details regarding EEG preprocessing, analysis, and calculation of effect-site drug concentrations). Vertical lines indicate major intraoperative events. 173 min: surgical closure, 179 min: shift to bed, 185 min: extubation.

DISCUSSION

Our patient’s clinical presentation suggested a neurological or psychiatric cause. The possibility of a cerebral cortical or pontine stroke was considered. However, a thorough clinical examination did not support this. A frontal lobe stroke typically involves impaired eye tracking and intact arm movements, which were not observed in our patient. Additionally, characteristics of locked-in syndrome, such as preserved upward gaze and eye blinking, did not align with our patient’s glassy-eyed unresponsiveness. The absence of prior psychiatric history made conditions like catatonia, conversion disorder, and malingering unlikely. Without an EEG in the PACU at the time of the unresponsive episode, it is difficult to rule out conditions like nonconvulsive status epilepticus and reach an unequivocal diagnosis. We suggest that a mechanism analogous to sleep paralysis is the best explanation for this presentation because she had postoperative recall of the events, indicating complete awareness while unresponsive, and abrupt arousal from an EEG pattern that resembled deep sleep (see Table 2).

The distinctive feature of this case is the explicit recall and awareness during the period of motor unresponsiveness. In classically described sleep paralysis, sudden wakefulness occurs coincident with ongoing muscle paralysis.8 Two case reports have documented instances of sleep paralysis occurring postanesthesia. However, neither of these studies described the intraoperative and emergence EEG.5,9 The paralysis is caused by pontine and medullary suppression of skeletal muscle tone via inhibition of motor neurons through neurotransmitters gamma-amino-butyric acid (GABA) and glycine.10 The postsynaptic GABA type A receptor is a major molecular target of many anesthetics and may be a point of convergence between natural sleep and anesthesia mechanisms, as described by Franks and Zacharia.11 In our case, it would seem plausible that the general anesthetic drugs may have caused a disproportionate GABAergic brainstem inhibition of volitional motor responses for at least an hour after the return of consciousness; a chemically induced sleep paralysis, albeit without the commonly reported distressing hallucinatory component.

Intraoperatively, our patient displayed features consistent with a “frail brain” phenotype, marked by an inability to generate frontal alpha power—a sign of heightened susceptibility to burst suppression.12 This group of patients is believed to have an increased sensitivity to anesthesia medication, which was confirmed in this case by the EEG burst suppression induced by the modest propofol infusion on top of waning desflurane concentrations. This was followed by an arousal from a delta-dominant EEG pattern. This abrupt transition from deep sedation is distinctive of atypical presentations in the PACU in adults and is associated with a greater risk of delirium and postoperative pain.13

In situations similar to our case, clinicians should adopt a stepwise approach as described by Thomas et al,2 ruling out life-threatening and reversible causes of unconsciousness, followed by consideration of the rare ones. Frontal EEG monitoring can aid in detecting unusual EEG patterns at emergence. An abrupt emergence pattern from high delta power may be associated with subsequent aberrant motor responses. Early intraoperative identification of unique EEG patterns may help predict an atypical postoperative course.

DISCLOSURES

Name: Antara Banerji, MBBS, MD.

Contribution: This author helped to analyze EEG data, create figures and tables, write and revise the article.

Name: Jamie W. Sleigh, MBChB, FANZCA, MD.

Contribution: This author helped to revise critically, proofread, and edit the article.

Name: Jonathan Termaat, BNurs.

Contribution: This author helped to collect data, follow up with the patient, write the relevant clinical findings, and review the article.

Name: Logan J. Voss, PhD.

Contribution: This author helped to write, proofread, and edit the article.

This manuscript was handled by: Bobbie Jean Sweitzer, MD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding: The AlphaMax study was funded by a project Grant from the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (17/009). This study was also awarded a grant from the Shrimpton Fund (University of Auckland School of Medicine Foundation). Departmental support was also provided.

Prior presentations: Euroanaesthesia 2023, Glasgow. Poster presentation.

Clinical Trial Registry: Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ID: 12617001354370) on September 27, 2017.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cascella M, Bimonte S, Di Napoli R. Delayed emergence from anesthesia: what we know and how we act. Local Reg Anesth. 2020;13:195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas E, Martin F, Pollard B. Delayed recovery of consciousness after general anaesthesia. BJA Educ. 2020;20:173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yonekura H, Murayama N, Yamazaki H, Sobue K. A case of delayed emergence after propofol anesthesia: genetic analysis. A A Case Rep. 2016;7:243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albrecht RFI, Wagner IV, SR, Leicht CH, Lanier WL. Factitious disorder as a cause of failure to Awaken after general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyun DM, Han JW, Kim YM, Kim JS. A Sleep paralysis after total knee replacement and arthroplasty – a low dose midazolam recovered mental status: case report. Asia Pac J Health Sci. 2019;6:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee IO, Kim IH, Park JH, Park JY, Park YC. Transient akinetic mutism following general anesthesia: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 1999;36:360–364. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaskell A, Pullon R, Hight D, et al. Modulation of frontal EEG alpha oscillations during maintenance and emergence phases of general anaesthesia to improve early neurocognitive recovery in older patients: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahlitz M, Parkes JD. Sleep paralysis. Lancet (London, England). 1993;341:406–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spector M, Bourke DL. Anesthesia, sleep paralysis, and physostigmine. Anesthesiology. 1977;46:296–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jalal B, Ramachandran VS. Sleep paralysis, “the ghostly bedroom intruder” and out-of-body experiences: the role of mirror neurons. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017;11:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franks NP, Zecharia AY. Sleep and general anesthesia. Canadian J Anaesth. 2011;58:139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao YR, Kahali P, Houle TT, et al. Low frontal alpha power is associated with the propensity for burst suppression: an electroencephalogram phenotype for a “vulnerable brain.” Anesth Analg. 2020;131:1529–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hesse S, Kreuzer M, Hight D, et al. Association of electroencephalogram trajectories during emergence from anaesthesia with delirium in the postanaesthesia care unit: an early sign of postoperative complications. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:622–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jc H, Ta S. Assessment of the Awake but Unresponsive Patient. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;5:227–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tzabazis A, Miller C, Dobrow MF, Zheng K, Brock-Utne JG. Delayed emergence after anesthesia. J Clin Anesth. 2015;27:353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.