Abstract

Skin pigmentation is negatively associated with circulating vitamin D (VD) concentration. Therefore, genetic factors involved in skin pigmentation could influence the risk of vitamin D deficiency (VDD). We evaluated the impact genetic variants related to skin pigmentation on VD in Mexican population. This cross-sectional analysis included 848 individuals from the Health Worker Cohort Study (ratio males to females ~ 1:3). Eight genetic variants: rs16891982 (SLC45A2), rs12203592 (IRF4), rs1042602 and rs1126809 (TYR), rs1800404 (OCA2), rs12913832 (HERC2), rs1426654 (SLC24A5), and rs2240751 (MFSD12); involved in skin pigmentation were genotyped. Skin pigmentation was assessed by self-report. Linear and logistic regression were used to assess the association between the variants of interest and VD and VDD, as appropriate. In our study, eight genetic variants were associated with skin pigmentation. A genetic risk score built with the variants rs1426654 and rs224075 was associated with lower VD levels (β = − 1.38, 95% CI − 2.59, − 0.17, p = 0.025). Nevertheless, when examining gene–gene interactions, we observed that rs2240751 × rs12203592 were associated with VD levels (P interaction = 0.021). Whereas rs2240751 × rs12913832 (P interaction = 0.0001) were associated with VDD. Our results suggest that skin pigmentation-related gene variants are associated with lower VD levels in Mexican population. These results underscore the importance of considering genetic interactions when assessing the impact of genetic polymorphisms on VD levels.

Keywords: 25-hydroxivitamin D, Skin pigmentation, Vitamin D deficiency, Genetic variants, Gene–gene interaction, Vitamin D

Subject terms: Calcium and vitamin D, Metabolism, Genome-wide association studies

Introduction

Vitamin D (VD) is a fat-soluble nutrient that not only plays a crucial role in maintaining bone health but has also been associated with supporting immune function and reducing the risk of several chronic conditions1–3. Sunlight exposure remains the primary factor for VD synthesis in human skin. Nonetheless, various factors, including sunscreen use, skin pigmentation, length of daylight, season of the year, latitude and age, can affect the production of cutaneous VD4. Melanin absorbs and scatters Ultraviolet Radiation B (UVR-B), which leads to a less efficient conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol into pre-vitamin D3. Consequently, individuals with darker skin pigmentation will experience a slower rate of VD synthesis than those with lighter skin pigmentation5. Skin pigmentation is a complex trait influenced by multiple genes, exhibiting variation inter and intra populations6. Several genes associated with skin pigmentation, such as SLC45A2, SLC24A5, GRM5/TYR, MFSD12, IRF4, HERC2, and TYR/OCA2, have been identified through Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) in diverse populations7,8. In Latin Americans, significant interactions between Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) in genes SLC45A2, SLC24A5, HERC2/OCA2, and TYR/GRM5 have been identified to play a significant role in skin pigmentation9.

Variants involved in different aspects of skin pigmentation, such as rs7565264 (MLPH), rs10932949 (PAX3) and rs9328451 (BLOC1S5), showed a significant association with 25- hydroxyvitamin D levels (25(OH)D) in Europeans10. In addition, Saternus et al.11, presented evidence about genetic variants, in 11 genes, affecting serum 25(OH)D levels, including exocyst complex component 2 (EXOC2), tyrosinase -related protein type 1 (TYRP1). More recently, in African Americans (AAs), the variant, rs2675345 near SLC24A5, showed a strong association with skin pigmentation. The authors generated a Genetic Score using the top three associated SNVs, rs2470102 (SLC24A5), rs16891982 (SLC45A2) and rs1800404 (OCA2) which was significantly associated with vitamin D deficiency (VDD)12. A study in Denmark found that genetic variants in pigment-related SNVs have stronger association with UVB-induced of 25(OH)D increase than skin pigmentation13.

Despite that Mexico is in the intertropical convergence zone with a vast area of high sun exposure, VDD remains a major public health problem14–16. The high prevalence of VDD in Mexico raises questions regarding the role of skin pigmentation on this condition. In a previous study, we identified an association between higher skin pigmentation and lower VD levels. Additionally, we observed an interaction between skin pigmentation and the variant rs3819817-T in the Histidine Ammonia-Lyase gene17. However, how genetic variants affect skin pigmentation and as a consequence, serum 25(OH) D levels has not been explored in Mexican-Mestizo individuals. In the present work we conducted a study to evaluate association between genetic variants and skin pigmentation and the effect of those variants on VD levels and VDD in Mexican-mestizo population.

Methods

Study population

The present study included 850 participants aged 18 to 92 years (ratio males to females ~ 1:3), a subsample from the Health Worker Cohort Study (HWCS) conducted in Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico. Only individuals born in Mexico, whose parents and grandparents identified themselves as Mexican mestizos were included in the study. The HWCS aimed to investigate various aspects of health and health-related behaviors. The details about this cohort have been previously reported18. In general, we included individuals with information from 2010 and 2012, for whom we had access to data on skin pigmentation, serum 25(OH)D concentrations and DNA samples (n = 848).

25 hydroxyvitamin D levels

Serum 25(OH)D concentration was assessed using the LIAISON® 25OH Vitamin D Total Assay (DiaSorin kit) with intra- and inter-assay variation coefficients < 10%19. The VDD definition, as established in previous studies, was set at levels below 20 ng/mL16,20.

Skin pigmentation self-report Fitzpatrick skin phototype

Participants were asked to self-report their skin type using the Fitzpatrick Skin Type Classification Scale, which consists of four categories: Type I-II (very fair-fair), type III (medium), Type IV (olive), Type V-VI (brown-dark brown or black)21. This adaptation aimed to better reflect the constitutive skin color of individuals in our population, while excluding extreme categories that were absent (Type I and Type VI). It's important to note that while the Fitzpatrick scale primarily assesses the response of skin to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) and includes tanning ability as a factor, our study focused solely on categorizing individuals based on their constitutive skin color, without considering tanning abilities or the skin's response to UVR.

Skin pigmentation related-genes polymorphisms

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes using the Puregene Blood Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SNVs were considered for genotyping based on the results of the Consortium for the Analysis of the Diversity and Evolution of Latin America (CANDELA)9. Eight SNVs: rs16891982 (SLC45A2), rs12203592 (IRF4), rs1042602 and rs1126809 (TYR), rs1800404 (OCA2), rs12913832 (HERC2), rs1426654 (SLC24A5), and rs2240751 (MFSD12); were selected for genotyping based on them meeting the three established criteria: (a) SNV previously reported with strong association with skin pigmentation, (b) SNV possess an effect on gene expression in the skin reported in The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project22, and (c) SNV have been reported in association with serum vitamin D levels. The remaining SNPs were not selected because they did not meet the three previously established criteria. Genotyping was performed using predesigned TaqMan SNP Genotyping assays (Applied Biosystems, Massachusetts, MA, USA) in a QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Massachusetts, MA, USA). The automatic variant call was carried out with the Sequence Detection System (SDS) software, version 2.2.1.

Other covariates

Demographic information, medication use, calcium supplementation, hormone replacement therapy, and lifestyle factors like dietary intake, physical activity, and smoking status were collected through a self-report questionnaire.

Trained nurses performed anthropometric and clinic measurements using standardized procedures (with a kappa value ranging from 0.84 to 0.90), as previously described18. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight by height squared (kg/m2) and classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations23.

VD intake and alcohol intake were obtained using a validated semiquantitative frequency questionnaire. VD intake was calculated based on the data obtained from the questionnaire and utilizing food composition tables compiled by the National Institute of Public Health18. Subsequently, both VD intake and alcohol intake were categorized into tertiles. Smoking status was classified as never, former, or current. Leisure-time physical activity (PA) was calculated using data from a previously validated PA questionnaire and categorized according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria24. Season of blood collection was defined as spring (March, April, May), summer (June, July, August), autumn (September, October, November), and winter (December, January, February), serving as a proxy for sun exposure.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the overall characteristics of the study population. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was computed to calculate the adjusted relative risk ratios (ARRR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) to determine the associations between SNVs and skin pigmentation. This model was adjusted by age and sex. The adjustments for multiple tests were made using the Bonferroni correction method (P value for Bonferroni correction = 0.05/8 = < 0.0063). Additionally, it's important to note that we have decided not to adjust for multiple testing in the gene–gene interaction analysis. Given the exploratory nature of these analyses and the need for larger sample sizes to detect significant effects in gene–gene interactions, we believe that applying a strict Bonferroni correction may overly penalize our ability to detect potentially meaningful associations. Therefore, we have chosen not to implement a Bonferroni correction specifically for the gene–gene interaction tests. This decision is in line with current practices in the field and aims to balance the risk of Type I and Type II errors in the context of our study design.

A weighted genetic risk score (GRS) was computed to examine the cumulative effect of the SNVs. The weighted GRS was calculated by multiplying the number of risk alleles of each SNV (0, 1, or 2), by the weight assigned to that SNV, derived from a logistic regression of the association between skin pigmentation and the variants rs2240751 and rs1426654. The sum was then taken across the two SNVs. We divided the continuous GRS into tertiles and compared the risk between them. Additionally, we constructed a GSR using the eight genetic variants previously linked to skin pigmentation. The model used for GRS construction was adjusted for age and sex, and estimators were obtained under an additive model. Alleles were weighted according to the estimated coefficients from logistic regression with skin pigmentation, grouping categories III-VI and category I-II as reference. Specifically, a weight of 0 was assigned for the wild-type allele, the coefficient for the heterozygous genotype was used as a weight, and for the homozygous genotype for the mutated allele, the weight was double the coefficient. This yielded a GRS ranging from − 4.87 to 3.38. Subsequently, we divided the GRS into quartiles due to sample size considerations.

The GSR presented here were derived from our dataset. Additionally, we used betas coefficients from the CANDELA study9 to estimate an additional weighted genetic risk score following the same procedures (GRS − 14.35 to 5.44). Subsequently, we divided the GRS into quartiles, Supplementary Table 1 online shows the mean and number (N) of individuals in each category derived from the quartiles for each estimated genetic risk score. It is important to note that all three GRS were standardized (individual value − mean/standard deviation) to make them more comparable and evaluated with both 25-(OH)D levels and VDD, with the unit of change defined as one standard deviation.

Linear and logistic regression analyses were performed as appropriate to assess the association between SNVs/GRS and VD levels and VDD. These models were adjusted for age, sex, VD intake, physical activity, smoking status, blood collection season, BMI categories, and alcohol consumption.

To assess the gene–gene interaction, a multiplicative interaction term (SNV × SNV) was included in the statistical model. The significance of the interaction effect was evaluated using Wald test.

All statistical significance parameters were initially set at a P value < 0.05. However, it's important to note that adjustments for multiple testing were applied differently across analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA v14.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX).

Ethics approval

The research was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with the relevant guidelines and ethical regulations in research involving human participants.

Informed consent statement

All participants in the study provided written informed consent.

Results

Characteristics of participants

The study sample comprised 848 participants (201 males and 647 females, ratio approximately 1:3) with a median age of 53 (P25–P75: 43–63) years. The Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants stratified by sex. Overall, most participants, regardless of sex, had overweight-obesity, were physically inactive, and had a high prevalence of VDD. Additionally, around 65% of participants identified themselves as having skin pigmentation type IV (olive) according to the Fitzpatrick Skin Type Classification.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of study population.

| Parameter | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 848 | n = 201 | n = 647 | |

| Age (years)a | 53 (43–62) | 51 (42–59) | 53 (43–62) |

| BMI (kg/m)a | 26.5 (23.9–29.3) | 26.3 (24.0–28.7) | 26.5 (23.9–29.4) |

| Overweight, % | 42.6 | 47.3 | 41.1 |

| Obesity, % | 21.7 | 17.9 | 22.9 |

| Body fat proportiona | 42.2 (35.1–47.4) | 31.3 (28.3–34.2) | 44.5 (40.4–48.8) |

| Leisure time physical activity (hour/week)a | 1.5 (0.4–3.5) | 1.5 (0.4–4.3) | 1.5 (0.3–3.5) |

| Active (≥ 150 min/week), % | 34.8 | 37.3 | 34.0 |

| Smoking status, % | |||

| Current, % | 11.4 | 19.4 | 9.0 |

| Past, % | 27.6 | 41.8 | 23.2 |

| 25-hydroxivitamin D (ng/mL)a | 21.6 (17.1–25.6) | 21.9 (18.6–27.0) | 21.3 (16.8–25.0) |

| Vitamin D deficiency, % | 41.4 | 36.3 | 43.0 |

| VDBP ( µmol/l)a | 272.9 (233.9–317.3) | 266.1 (229.7–306.2) | 275.1 (237.1–319.5) |

| Vitamin D intake (UI/day)a | 149.2 (89.9–254.8) | 145.6 (79.5–251.5) | 150.5 (91.8–256.1) |

| Blood collection season, % | |||

| Winter, % | 14.0 | 15.9 | 13.5 |

| Spring, % | 51.3 | 50.8 | 51.5 |

| Summer, % | 23.4 | 21.4 | 24.0 |

| Autumn; % | 11.3 | 11.9 | 11.1 |

| Alcohol (g/day)a | 0.8 (0.2–3.7) | 4.5 (0.8–10.3) | 0.8 (0.04–2.3) |

| Skin type I-II, % | 15.5 | 15.4 | 15.5 |

| Skin type III, % | 12.5 | 12.4 | 12.5 |

| Skin type IV, % | 65.1 | 64.2 | 65.4 |

| Skin type V-VI, % | 6.7 | 8.0 | 6.5 |

aMedian (P25-P75).

Genetic association with skin pigmentation

In the whole sample, all SNVs were in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium, except the variant rs1426654 (p = 0.016). In agreement with other studies in Mexican-mestizos, this deviation from Hardy–Weinberg is an effect of mixed population25–27. The minor allele frequencies (MAFs) for the evaluated variants were: 0.224 for rs2240751-G, 0.050 for rs12203592-T, 0.172 for rs12913832-G, 0.57 for rs1426654-G, 0.190 for rs1042602-A, 0.486 for rs1800404-C, 0.322 for rs16891982-G, and 0.067 for rs1126809-A (Supplementary Table S2 online). Table 2 shows the genotype frequencies within each skin pigmentation category. We used multinomial regression models to explore the relationship between these variants and skin pigmentation, categorized into four levels ranging from lighter to darker. We observed significant associations between eight variants and skin categories I-II and V-VI, assessed under both additive and dominant models. Notably, variants rs2240751-G and rs1426654-G showed higher odds for darker pigmentation, while variants rs12203592-T, rs12913832-G, rs1042602-A, rs1800404-T, rs16891982-G, and rs1126809-A were associated with lower odds for darker skin pigmentation after adjusting for age and sex (Table 3).

Table 2.

Genotype frequencies of genetic variants by skin pigmentation type.

| Gene | SNV | Genotype | Skin type | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I-II, n = 131 | Type III, n = 106 | P value* | Type IV, n = 552 | P value* | Type V-VI, n = 59 | P value* | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| SLC45A2 | rs16891982 | CC | 22 | 16.9 | 41 | 39.4 | 280 | 51.6 | 41 | 70.7 | |||

| CG + GG | 108 | 83.1 | 63 | 60.6 | 0.0001 | 263 | 48.4 | 9.8 × 10–13 | 17 | 29.3 | 5.4 × 10–13 # | ||

| IRF4 | rs12203592 | CC | 109 | 83.2 | 90 | 85.7 | 504 | 92.3 | 58 | 98.3 | |||

| CT + TT | 22 | 16.8 | 15 | 14.3 | 0.5984 | 42 | 7.7 | 0.0014 | 1 | 1.7 | 0.0032# | ||

| TYR | rs1042602 | CC | 59 | 45.0 | 47 | 44.8 | 165 | 30.3 | 9 | 15.5 | |||

| CA + AA | 72 | 55.0 | 58 | 55.2 | 0.9662 | 380 | 69.7 | 0.001 | 49 | 84.5 | 0.0001# | ||

| TYR | rs1126809 | GG | 106 | 82.2 | 88 | 85.4 | 471 | 87.7 | 56 | 96.6 | |||

| GA + AA | 23 | 17.8 | 15 | 14.6 | 0.5042 | 66 | 12.3 | 0.0969 | 2 | 3.4 | 0.0075 | ||

| OCA2 | rs1800404 | CC | 14 | 10.7 | 16 | 15.2 | 159 | 29.2 | 18 | 31.0 | |||

| CT + TT | 117 | 89.3 | 89 | 84.8 | 0.2969 | 386 | 70.8 | 0.00001 | 40 | 69.0 | 0.0006# | ||

| HERC2 | rs12913832 | AA | 61 | 46.6 | 63 | 59.4 | 412 | 75.0 | 50 | 84.7 | |||

| AG + GG | 70 | 53.4 | 43 | 40.6 | 0.049 | 137 | 25.0 | 2.0 × 10–10 | 9 | 15.3 | 7.7 × 10−7# | ||

| SLC24A5 | rs1426654 | AA | 63 | 48.5 | 26 | 25.0 | 81 | 14.9 | 1 | 1.8 | |||

| AG + GG | 67 | 51.5 | 78 | 75.0 | 0.0002 | 464 | 85.1 | 4.4 × 10–17 | 56 | 98.2 | 5.8 × 10–10# | ||

| MFSD12 | rs2240751 | AA | 99 | 76.7 | 62 | 60.8 | 305 | 57.0 | 30 | 52.6 | |||

| AG + GG | 30 | 23.3 | 40 | 39.2 | 0.009 | 230 | 43.0 | 0.00004 | 27 | 47.4 | 0.001# | ||

*Type 1-II was considered as reference. The symbol # indicates which variants passed the Bonferroni multiple testing adjustment (p-value was < 0.0063).

Table 3.

Association between SNVs and skin pigmentation type.

| Gene | SNV | Model | Genotype | Type III vs Type I–II RRR (95%CI) |

P value |

Type IV vs Type I–II RRR (95%CI) |

P value | Type V–VI vs Type I–II RRR (95%CI) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLC45A2 | rs16891982 | Additive | 0.3 (0.44,1.62) | 2 × 10–8# | 0.16 (0.11,0.23) | 0# | 0.08 (0.04,0.14) | 1.1 × 10–15# | |

| Dominant | CC | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| CG + GG | 0.33 (0.18,0.60) | 0.0003# | 0.19 (0.12,0.31) | 3.4 × 10–11# | 0.08 (0.04,0.18) | 3.4 × 10–11# | |||

| IRF4 | rs12203592 | Additive | 0.85 (0.43,1.70) | 0.6506 | 0.43 (0.25,0.73) | 0.0018# | 0.09 (0.01,0.65) | 0.0177 | |

| Dominant | CC | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| CT + TT | 0.88 (0.43,1.81) | 0.7297 | 0.42 (0.24,0.73) | 0.0021# | 0.08 (0.01,0.64) | 0.0171 | |||

| TYR | rs1042602 | Additive | 1.01 (0.67,1.51) | 0.9584 | 0.61 (0.45,0.83) | 0.0019# | 0.29 (0.14,0.58) | 0.0005# | |

| Dominant | CC | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| CA + AA | 1.01 (0.60,1.69) | 0.9751 | 0.53 (0.36,0.79) | 0.0015# | 0.23 (0.10,0.50) | 0.0002# | |||

| TYR | rs1126809 | Additive | 0.84 (0.44,1.62) | 0.6056 | 0.68 (0.42,1.10) | 0.1157 | 0.18 (0.04,0.75) | 0.0193 | |

| Dominant | GG | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| GA + AA | 0.8 (0.39,1.62) | 0.5295 | 0.65 (0.39,1.09) | 0.1022 | 0.16 (0.04,0.72) | 0.0170 | |||

| OCA2 | rs1800404 | Additive | 0.73 (0.50,1.06) | 0.0954 | 0.44 (0.33,0.59) | 2.7 × 10–8# | 0.34 (0.21,0.53) | 2.8 × 10–6# | |

| Dominant | CC | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| CT + TT | 0.68 (0.32,1.48) | 0.3346 | 0.29 (0.16,0.52) | 4 × 10–5# | 0.26 (0.12,0.58) | 0.0009# | |||

| HERC2 | rs12913832 | Additive | 0.65 (0.43,0.97) | 0.0372 | 0.33 (0.24,0.46) | 1.6 × 10–11# | 0.18 (0.09,0.37) | 3.9 × 10–6# | |

| Dominant | AA | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| AG + GG | 0.61 (0.36,1.03) | 0.0650 | 0.29 (0.20,0.43) | 8.4 × 10–10# | 0.16 (0.07,0.35) | 4.5 × 10–6# | |||

| SLC24A5 | rs1426654 | Additive | 1.94 (1.33,2.83) | 0.0005# | 3.24 (2.41,4.36) | 6.7 × 10–15# | 9.31 (5.30,16.34) | 8.2 × 10–15# | |

| Dominant | AA | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| AG + GG | 2.74 (1.56,4.81) | 0.0005# | 5.38 (3.54,8.18) | 2.9 × 10–15# | 52.82 (7.09,393.34) | 0.0001# | |||

| MFSD12 | rs2240751 | Additive | 1.79 (1.10,2.90) | 0.0188 | 1.95 (1.33,2.86) | 0.0006# | 2.19 (1.27,3.80) | 0.0050# | |

| Dominant | AA | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| AG + GG | 2.11 (1.19,3.74) | 0.0102 | 2.49 (1.60,3.87) | 0.0001# | 2.95 (1.52,5.73) | 0.0013# |

Models adjusted by age (years) and sex. The symbol # indicates which variants passed the Bonferroni multiple testing adjustment (p-value was < 0.0063).

RRR: Relative Risk Ratio.

Genetic association with 25(OH)D levels and Vitamin D deficiency

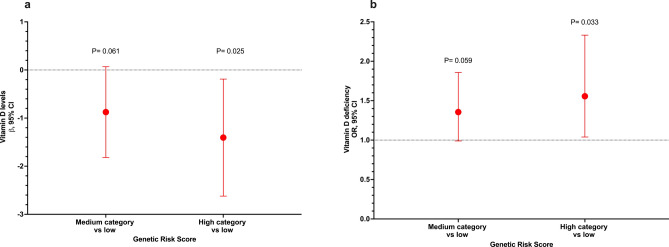

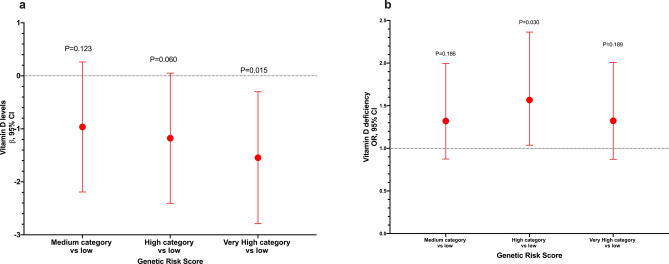

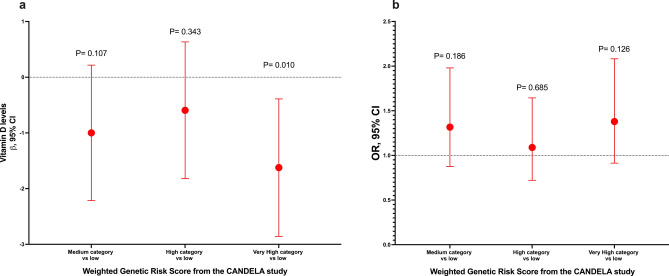

No significant differences in VD levels or prevalence of VDD were observed between the different genotypes of the analyzed variants (Supplementary Table S3 online). Furthermore, after adjusting for potential confounders, we did not observe any association between the SNVs and VD levels or VDD (Supplementary Table S4 online). Afterward, we selected the two variants associated with darker skin pigmentation and constructed a GRS. Interestingly, we observed an association between the highest category of the GRS and lower VD levels (β = − 1.38, 95% CI − 2.59, − 0.17, P = 0.025) and increased odds of VDD (OR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.04–2.32, P = 0.033) when compared to the lowest category of the GRS (Fig. 1). Additionally, with the GRS comprising the eight genetic variants, we observed a similar association for VD levels (very high category vs low: β = − 1.54, 95% CI − 2.79, − 0.30, P = 0.015), while the association for VDD was not statistically significant (very high category vs low: OR = 1.32, 95% CI 0.87–2.01, P = 0.189) (Fig. 2). However, we observed an association for high category vs low: OR = 1.57, 95%CI 2.36–1.04, P = 0.030. Based on the weighted GRS derived from the CANDELA study, we observed a significant association with VD levels (very high category vs low: β = − 1.62, 95% CI − 2.85, − 0.38, P = 0.010). However, the association with VDD did not reach statistical significance (very high category vs low: OR = 1.38, 95% CI 0.91–2.08, P = 0.126) (Fig. 3). When stratified into quintiles, we found significant associations both for vitamin D levels (β = − 1.72, 95% CI − 3.12, − 0.33, p = 0.016) and for VDD (very high category vs very low: OR = 1.60, 95% CI 1.01–2.54, p = 0.047). However, it is noteworthy that the odds ratios for the middle quintile categories of VDD exhibit greater inconsistency (data not shown). The Supplementary Table S5 presents associations between standardized GRS and 25(OH)D levels, as well as VDD. GRS 2, constructed with all 8 variants weighted using coefficients estimated from our data, showed a significant association with lower 25(OH)D levels (β = − 0.20, 95% CI − 0.38, − 0.04, P = 0.017). Additionally, GRS 3 also demonstrated a significant association with lower 25(OH)D levels (β = − 0.54, 95% CI − 0.98, − 0.10, P = 0.017). However, GRS 1 did not show a statistically significant association with either outcome. Associations with VDD were not statistically significant across any GRS categories (Supplementary Table S5 online).

Figure 1.

Association between the genetic risk score of skin pigmentation-related gene variants and VD levels and vitamin deficiency. (a) Genetic risk score with VD levels. (b) Genetic risk score with VDD. Models adjusted for age (years), sex, BMI categories, blood season collection, VD intake (tertiles), physical activity (inactive, active), smoking status, and alcohol intake (tertiles). GRS was estimated using the variants rs2240751 (MFSD12) and rs1426654 (SLC24A5). GRS categories were defined by tertiles. Category low was the reference category in both analyses.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity analysis: Association between the genetic risk score of skin pigmentation-related gene variants and VD levels and vitamin deficiency. (a) Genetic risk score with VD levels. (b) Genetic risk score with VDD. Models adjusted for age (years), sex, BMI categories, blood season collection, VD intake (tertiles), physical activity (inactive, active), smoking status, and alcohol intake (tertiles). GRS was estimated using eight variants. GRS categories were defined by quartiles. Category low was the reference category in both analyses.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis: Association between the weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) from the CANDELA study of skin pigmentation-related gene variants and VD levels and VDD. (a) Genetic risk score with VD levels. (b) Genetic risk score with VDD. Models adjusted for age (years), sex, BMI categories, blood season collection, VD intake (tertiles), physical activity (inactive, active), smoking status, and alcohol intake (tertiles). The wGRS was estimated using eight variants derived from the CANDELA study. GRS categories were defined by quartiles. Category low was the reference category in both analyses.

Interaction between skin pigmentation related-genes polymorphisms and 25(OH)D levels

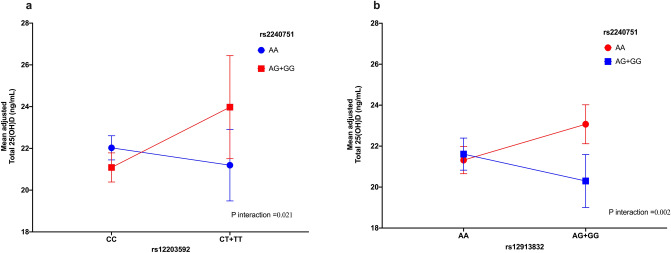

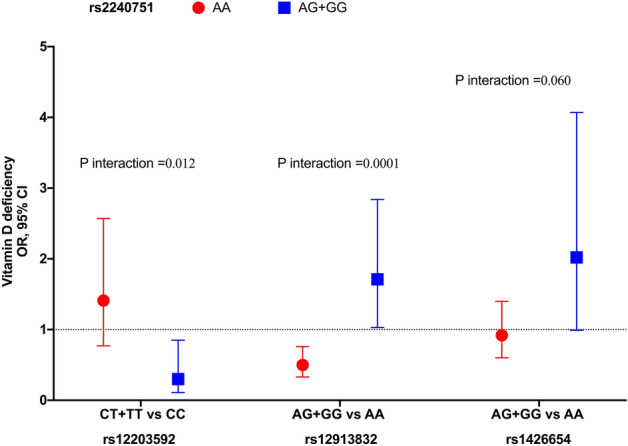

We observed an interaction between the variants rs2240751 × rs12203592 and rs2240751 × rs12913832 with VD levels (Fig. 4a and b) and VDD (Fig. 5) (Supplementary Table S6 online). Individuals carrying at least one copy of the G allele of the variant rs2240751 and at least one copy of the T allele of the variant rs12203592 showed, on average, an increase of 2.91 ng/ml (β = 2.94, 95% CI 0.37, 5.51) and 70% (OR = 0.30, 95% CI 0.11–0.85) lower odds for VDD. However, for individuals homozygous for the A allele of the variant rs2240751 and at least one copy of the T allele of the variant rs12203592, no significant association was observed (β = − 0.83, 95%CI − 2.64, 0.98; OR = 1.41, 95%CI 0.77–2.59, for VD levels and VDD, respectively) (Figs. 4a and 5).

Figure 4.

Skin pigmentation related-genes variants interactions with vitamin D levels. (a) Interaction rs2240751 × rs12203592. (b) rs2240751 × rs12913832. Models adjusted for age (years), sex, BMI categories, blood season collection, vitamin D intake (tertiles), physical activity (inactive, active), smoking status, and alcohol intake (tertiles).

Figure 5.

Skin pigmentation related-genes variants interactions with VDD. Models adjusted for age (years), sex, BMI categories, blood season collection, VD intake (tertiles), physical activity (inactive, active), smoking status, and alcohol intake (tertiles).

In contrast, individuals carrying at least one copy of the G allele of variant rs2240751 and at least one copy of the G allele of variant rs12913832 had a decrease on average, of 1.27 ng/ml (β = − 1.27, 95%CI − 2.79, 0.24) and 71% (OR: 1.71, 95%CI 1.03–2.84) higher odds of having VDD than individuals carrying the wild-type allele rs12913832-A (Figs. 4b and 5). However, individuals carrying at least one copy of the A allele of variant rs2240751 and at least one copy of the G allele of variant rs12913832 had, on average, an increase of 1.75 ng/ml (β = 1.75, 95%CI 0.58, 2.91) and 50% (OR: 0.50, 95%CI 0.33–0.76) lower odds for VDD than individuals carrying the wild-type allele rs12913832-A (Fig. 5).

Additionally, we observed a borderline interaction of rs2240751 × rs1426654 (p interaction = 0.060) with VDD (Fig. 5). The association of this interaction was similar to what was observed with the GRS. Individuals carrying at least one copy of the G allele of variant rs2240751 and at least one copy of the G allele of variant rs1426654 had two times higher odds for VDD (OR = 2.02, 95% CI 0.99–4.07) than individuals carrying the wild-type allele rs1426654-A (P = 0.051). However, for individuals carrying the wild-type A allele of variant rs2240751 and at least one copy of the G allele vs. AA of variant rs1426654, no statistically significant association was observed (OR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.60–1.40) (Fig. 5). Non-significant interactions between on VD levels are shown in Supplementary Figs. S1–S3 online.

Discussion

Skin pigmentation is a complex trait determined by the type, amount, and distribution of melanin produced in the epidermis by specialized organelles known as melanosomes28. Several candidate genes with a role in human skin color have been identified that affected skin pigmentation which may be partially driven by pleiotropic effects. Recent research has extended the hypotheses that the evolution of genetic skin pigmentation has driven changes in VD levels, emerging of interest in the linking. Based on the large Latin American populations (CANDELA) study9, we analyzed eight genetic variants associated with skin pigmentation in the Mexican-mestizo population. Our analysis revealed significant associations with seven variants, underscoring their importance in determining skin pigmentation in this population. These findings shed light on the genetic factors contributing to the diverse range of skin tones observed among Mexican-mestizo individuals. Our study supports the association of the variants rs1042602-A and rs1126809-A in the TYR gene which result in non-synonymous substitutions p.S192Y and p.R402Q, respectively, have been associated with lighter skin phototype9,29.

Additionally, rs16891982-G and OCA2-rs1800404-C were also associated with lighter skin. In this regard, the membrane transport proteins SLC24A5, SLC45A2, and OCA2 have been implicated in modulating melanosomal pH. The missense variant rs16891982 in SLC45A2 replaces a leucine for a phenylalanine in residue 374. This alteration is believed to accelerate the proteasomal degradation of this transporter, without altering its localization, disturbing the deacidification of melanosomes and impairing melanin synthesis30. The variant rs1800404 in OCA2 is a synonymous variant at codon 335, which codifies for alanine31. Pathogenic variants in this gene are the cause albinism oculocutaneous type II the most common form of albinism32. The C allele of this variant has been associated with darker skin, interestingly in our study population the proportion of CC homozygous increased from the skin pigmentation type I-II to the type IV, concurring with the reported association33.

On the other hand, genetic variants rs12203592-T and rs12913832-G involved in melanocyte development, were also associated with lighter skin in the Mexican population. The derived T allele of the rs12203592 in IRF4 reduces the ability of TFAP2A to bind to the intronic enhancer of IRF4, suppressing its expression and therefore, impairing the cooperative induction of TYR34. Whereas the rs12913832 in HERC2 is part of an enhancer involved in the recruitment of transcription factors promoting OCA2 expression. The G allele of this variant reduces the binding of the transcription factors and decreases OCA2 expression35. Thus, the genetic changes produce the impairment of melanin synthesis and result in a lighter phenotype.

In contrast, two of the eight SNPs investigated, rs1426654-G and rs2240751-G, were found to be correlated with darker skin. It has been proposed that rs1426654 was driven independently after the divergence of Europeans and Asians, resulting in reduced levels of heterozygosity in Europe, but not East Asia, and high allele frequency differences between modern populations36,37. Although the rs1426654-G light skin allele is almost fixed in Europe and associated with a lighter skin phototype in Africans and other Latin American populations, e.g., Brazil9,38, a possible hypothesis is that the SLC24A5 promotes a wide gamut of moderately pigmented phenotypes in the Mexican population as a way could influence cutaneous VD synthesis.

So far, the reports have shown that the variant rs2240751 in the MFSD12 gene is common only in East Asians and Native Americans. Adhikari et al. reported that the MFSD12 region shows significant evidence of selection in East Asians (dated after their split from Europeans) and that the frequency of the Y182H variant correlates with the intensity of solar radiation9. Recently, other variants of MFSD12 have been shown to impact skin pigmentation in Africans39, these variants are not in linkage disequilibrium with the variant analyzed in this study, which could suggest that they could also have a relevant role in skin pigmentation in our population. This study highlights the crucial role of noncoding and coding variants in determining human skin color and underscores the importance of studying Latin American populations with high levels of genetic and phenotypic variation.

At present, information on the relationship between skin color polymorphisms and VD is scarce. VD is a hormone pleiotropic, synthesized 80% endogenously in the keratinocytes after UVB light40. The importance of cutaneous vitamin D synthesis sparked a process of human evolution due to the need for its synthesis in geographic regions with lower levels of UVB radiation. Furthermore, VD status also depends on the surface of the skin exposed, for example, darker-skinned individuals require more time of sun exposure compared to light-skinned populations. This is due to the amount of epidermal melanin that obstructs the UVR-B. Given the limited current understanding of the relationship between skin color polymorphisms and VD, our study provides valuable insights into this complex interplay. By elucidating the impact of genetic variants associated with skin pigmentation on VD levels, we contribute to a deeper understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying VD synthesis and its potential implications for human health.

In our study, a genetic risk score was constructed using MFSD12-rs2240751 and SLC24A5-rs1426654, suggesting that gene–gene interactions impact VD levels and VDD. Similarly, Batai et al. reported a GSR where the genetic variant rs2675345, close to SLC24A5, was strongly associated with skin pigmentation and VDD in African Americans12. Further, a recent study showed that a decreased VD availability with increasing degrees of skin pigmentations is associated with reduced microvascular endothelial function in healthy young adults and may predispose darkly pigmented individuals to an increased risk of endothelial dysfunction41. In addition, we created a weighted genetic risk score using all eight genetic variants (and divided it into quartiles) and observed similar trends with serum VD levels. However, the association did not persist with VDD. One possible explanation for this discrepancy could be the size of the sample. Larger sample sizes are typically needed to detect associations with binary outcomes such as VDD compared to continuous outcomes like serum VD levels. Further investigation with larger cohorts may help elucidate the relationship between the GRS and VDD.

Gene–gene interactions have for a long time been postulated to make an important contribution to the determination of human complex traits42. Skin pigmentation plays a crucial role in the response to UV exposure and the efficient synthesis of VD43–45. Hence, it seems that the influence of gene–gene interactions should be considered a remarkable factor contributing to the serum VD levels in the Mexican mestizo population. We observed interactions of the rs2240751 in MFSD12 with two SNVs, the rs12203592 in IRF4, and the rs12913832 in HERC2. In addition, a borderline interaction between rs2240751 in MFSD12 and rs1426654 in SLC24A5, highlighting the complexity of these phenotypes. Building upon these findings, a study in Australian population identified an interaction between the genetic variants rs12203592 and rs12913832 in -IRF4 and HERC2, respectively, affecting serum VD levels46. However, no interaction was observed between rs12203592 in IRF4 and rs12913832 in HERC2 in our cohort.

Darker skin provides excellent natural protection against UV-induced damage due to increased melanin production and protection from folate degradation, whereas lighter skin synthesizes VD more efficiently upon UV exposure47. We found that the variant associated with dark skin in MFSD12 on a genetic background of HERC2 related to light skin affects VD levels, a significant interaction that would withstand adjustment for multiple testing if applied. Specifically, individuals with HERC2 light skin alleles (AG + GG) and genotype AA of rs2240751 of MFSD12, compared to those with AA-HERC2, showed higher average levels of VD. In comparison, those with genotype AG + GG of rs2240751 of MFSD12 and genotype AG + GG of rs12913832 of HERC2 showed lower average levels of VD than those with genotype AA of rs12913832 of HERC2. These findings suggest a complex gene–gene interaction between MFSD12 and HERC2 in determining VD levels, which could have important implications for understanding the variability in VD levels in populations with different skin genotypes. Furthermore, it's noteworthy that although information on the relationship between genetic variants associated with skin pigmentation and VD levels is currently limited, recent studies have revealed that VD availability varies with different degrees of skin pigmentation11,12,17,43, highlighting the importance of investigating such gene–gene interactions in the context of public health. Despite the limited exploration of gene–gene interaction involving genetic variants related to pigmentation, and their role in vitamin D levels in the scientific literature, our study suggests that this phenomenon could be participating in the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Mexican-Mestizo population. Studying genetics and biology of skin pigmentation not only helps deepen our understanding of human evolution, but could also offer insight into possible causes and treatments for other diseases where skin pigmentation is involved, such as melanoma and albinism48. However, additional studies in the Mexican population are required to delve into the complex relationship between skin pigmentation genetics and VD metabolism to validate and expand this hypothesis. These additional investigations will provide a solid foundation for developing more effective management strategies.

The strengths of this study include the incorporation of genetic variants reported in Latin-American population, the inclusion of various potential confounders in the analyses, and the use of reliable and validated measurement methods for data collection. Limitations of the study include the sample size (n = 848 individuals) and reliance on self-report information for skin pigmentation. Unfortunately, there was a shortage of male participants, constraining the exploration of sex interactions. Previous studies have indicated sex interactions, suggesting that sex hormones may modify genetic effects on skin pigmentation12,49. The cross-sectional design of our study limited the ability to establish definitive causal relationships between the investigated variables. While it's true that genotypes occurred prior to skin pigmentation phenotype and vitamin D levels, the lack of complete knowledge about the function of genetic variants can hinder the identification of causality. It's important to acknowledge that the complexity of the interaction between multiple genetic variants can also influence the ability to identify clear causal relationships. In this regard, genomic studies of the past two decades have revealed that the genetic plethora of skin pigmentation gene variants is vast, and many combinations of multiple variant genes have contributed to the complex pattern of skin pigmentation phenotypes and genotypes observed today50. Therefore, while our study provides a robust platform for exploring associations between genetic variants and skin pigmentation phenotypes, further research is needed to fully understand the underlying genetic basis and complex interactions that determine these phenotypes. It is conceivable that more significant interactions, particularly when evaluating categorized or dichotomous variables, were not detected due to the limited sample size. Additionally, the absence of ancestry data for adjusting potential population stratification is acknowledged. While efforts were made to adjust for various confounders, it is important to recognize the possibility of residual confounding factors not accounted for in our analyses. However, it is crucial to emphasize that the data are derived from a state in the central region of the country. Addressing these limitations is essential for refining the understanding of genetic complexity related to skin pigmentation and VD synthesis, and future research should consider these factors for a more comprehensive analysis.

In conclusion, our findings reveal a significant association between genetic variants related to skin pigmentation and VD levels in Mexican population. Although individual variants did not directly correlate with VD levels or deficiency, our research uncovered gene–gene interactions that play a crucial role in modulating VD levels and susceptibility to VDD. These results underscore the complexity of genetic factors influencing VD levels and suggest that the interaction between genetic polymorphisms related to skin pigmentation may modulate the risk of VDD in Mexican-Mestizo population. Genetic information related to skin pigmentation could be crucial when assessing individual risk of VDD and designing prevention and treatment strategies. However, further research is needed to validate and expand these findings, and better understand the underlying mechanisms of these genetic interactions in the regulation of VD levels.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff and participants of the HWSC study for their important contributions. The authors would like to thank the Chemist Mariela Esparza and MD, PhD Mara Medeiros for vitamin D measurement.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and Investigation: B.R.-P. and R.V.-C.; Writing- original draft preparation: B.R.-P., R.V.-C., and P.L-M..; Data Analysis: B.R.-P.; Writing—review and editing: B.R.-P., A.H.-B., P.L.-M., A.B.-C., N.P., E.D.-G., J.S., and R.V.-C.; Investigation and Resources; E.D.-G.; Data Curation and Collection: E.D.-G. and J.S.; Funding acquisition: R.V.-C and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica (INMEGEN), grant number 399–07/2019/I. A.B.-C. is the recipient of a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencia y Tecnología (CONAHCYT-Estancia Posdoctoral de Incidencia Inicial 2022 with CVU 508876). The Health Workers Cohort Study was supported by: Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Grant numbers: 7876, 87783, 262233, 26267M, SALUD-2010-01-139796, SALUD-2011-01-161930, CB-2013-01-221628, INFR-2016-01-270405, and Ciencia de Frontera CF-2019-102962).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository at 10.5281/zenodo.12707833.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-68437-0.

References

- 1.Bikle, D. D. Vitamin D regulation of immune function. Vitam. Horm.86, 1–21 (2011). 10.1016/B978-0-12-386960-9.00001-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Álvarez-Mercado, A. I., Mesa, M. D. & Gil, Á. Vitamin D: Role in chronic and acute diseases. Encycl. Hum. Nutr.10.1016/B978-0-12-821848-8.00101-3 (2023). 10.1016/B978-0-12-821848-8.00101-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang, H. et al. Vitamin D and chronic diseases. Aging Dis.8, 346–353 (2017). 10.14336/AD.2016.1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wacker, M. & Holick, M. F. Sunlight and vitamin D: A global perspective for health. Dermatoendocrinol.5, 51–108 (2013). 10.4161/derm.24494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libon, F., Cavalier, E. & Nikkels, A. F. Skin color is relevant to vitamin D synthesis. Dermatology227(3), 250–254 (2013). 10.1159/000354750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frisancho, A. R., Wainwright, R. & Way, A. Heritability and components of phenotypic expression in skin reflectance of Mestizos from the Peruvian lowlands. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.55, 203–208 (1981). 10.1002/ajpa.1330550207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lona-Durazo, F. et al. Meta-analysis of GWA studies provides new insights on the genetic architecture of skin pigmentation in recently admixed populations. BMC Genet.20, 59 (2019). 10.1186/s12863-019-0765-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerstenblith, M. R., Shi, J. & Landi, M. T. Genome-wide association studies of pigmentation and skin cancer: A review and meta-analysis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res.23, 587–606 (2010). 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00730.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adhikari, K. et al. A GWAS in Latin Americans highlights the convergent evolution of lighter skin pigmentation in Eurasia. Nat. Commun.10.1038/s41467-018-08147-0 (2019). 10.1038/s41467-018-08147-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossberg, W. et al. Human pigmentation, cutaneous vitamin d synthesis and evolution: Variants of genes (SNPs) involved in skin pigmentation are associated with 25(OH)D serum concentration. Anticancer Res.36, 1429–1437 (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saternus, R. et al. A closer look at evolution: Variants (SNPs) of genes involved in skin pigmentation, including EXOC2, TYR, TYRP1, and DCT, are associated with 25(OH)D serum concentration. Endocrinology156, 39–47 (2015). 10.1210/en.2014-1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batai, K. et al. Genetic loci associated with skin pigmentation in African Americans and their effects on vitamin D deficiency. PLoS Genet.17, e1009319 (2021). 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Datta, P. et al. Pigment genes not skin pigmentation affect UVB-induced vitamin D. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci.10.1039/C8PP00320C (2019). 10.1039/C8PP00320C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martínez-Zavala, N. et al. Vitamin D deficiency in Mexicans have a high prevalence: A cross-sectional analysis of the patients from the Centro Médico Nacional 20 de Noviembre. Arch. Osteoporos.15, 88 (2020). 10.1007/s11657-020-00765-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Contreras-Manzano, A., Villalpando, S. & Robledo-Pérez, R. Vitamin D status by sociodemographic factors and body mass index in Mexican women at reproductive age. Salud Publica Mex.10.21149/8080 (2017). 10.21149/8080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrillo-Vega, M. F., García-Peña, C., Gutiérrez-Robledo, L. M. & Pérez-Zepeda, M. U. Vitamin D deficiency in older adults and its associated factors: A cross-sectional analysis of the Mexican Health and Aging Study. Arch. Osteoporos.10.1007/s11657-016-0297-9 (2017). 10.1007/s11657-016-0297-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivera-Paredez, B. et al. The role of single nucleotide variant rs3819817 of the Histidine Ammonia-Lyase gene and 25-Hydroxyvitamin D on bone mineral density, adiposity markers, and skin pigmentation, Mexican population. J. Endocrinol. Invest.46, 1911–1921 (2023). 10.1007/s40618-023-02051-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denova-Gutiérrez, E. et al. Health workers cohort study: Methods and study design. Salud Publica Mex.58, 708–716 (2016). 10.21149/spm.v58i6.8299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman, J., Wilson, K., Spears, R., Shalhoub, V. & Sibley, P. Performance evaluation of four 25-hydroxyvitamin D assays to measure 25-hydroxyvitamin D2. Clin. Biochem.48, 1097–1104 (2015). 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holick, M. F. et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.10.1210/jc.2011-0385 (2011). 10.1210/jc.2011-0385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzpatrick, T. B. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch. Dermatol.10.1001/archderm.1988.01670060015008 (1988). 10.1001/archderm.1988.01670060015008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. https://gtexportal.org/home/.

- 23.WHO (World Health Organization). WHO obesity and overweight fact sheet no 311. Obes. Oveweight Fact Sheet (2013).

- 24.Who, W. H. O. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health (World Heal Organ, 2010). 10.1080/11026480410034349. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerra-García, M. T. et al. The −514C>T polymorphism in the LIPC gene modifies type 2 diabetes risk through modulation of HDL-cholesterol levels in Mexicans. J. Endocrinol. Investig.44, 557–565 (2021). 10.1007/s40618-020-01346-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng, H. W., Chen, W. M. & Recker, R. R. Population admixture: Detection by Hardy-Weinberg test and its quantitative effects on linkage-disequilibrium methods for localizing genes underlying complex traits. Genetics157, 885–897 (2001). 10.1093/genetics/157.2.885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conomos, M. P. et al. Genetic diversity and association studies in US Hispanic/Latino populations: Applications in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am. J. Hum. Genet.98, 165–184 (2016). 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rocha, J. The evolutionary history of human skin pigmentation. J. Mol. Evol.88, 77–87 (2020). 10.1007/s00239-019-09902-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, Y. Association of pigmentation related-genes polymorphisms and geographic environmental variables in the Chinese population. Hereditas158, 24 (2021). 10.1186/s41065-021-00189-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le, L. et al. SLC45A2 protein stability and regulation of melanosome pH determine melanocyte pigmentation. Mol. Biol. Cell31, 2687–2702 (2020). 10.1091/mbc.E20-03-0200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Information, N. C. for B. rs1800404-dbSNP Short Genetic Variations. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs1800404#variant_details (2022).

- 32.Gardner, J. M. et al. The mouse pink-eyed dilution gene: Association with human Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Science257, 1121–1124 (1992). 10.1126/science.257.5073.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crawford, N. G. et al. Loci associated with skin pigmentation identified in African populations. Science10.1126/science.aan8433 (2017). 10.1126/science.aan8433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Praetorius, C. et al. A polymorphism in IRF4 affects human pigmentation through a tyrosinase-dependent MITF/TFAP2A pathway. Cell155, 1022–1033 (2013). 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Visser, M., Kayser, M. & Palstra, R.-J. HERC2 rs12913832 modulates human pigmentation by attenuating chromatin-loop formation between a long-range enhancer and the OCA2 promoter. Genome Res.22, 446–455 (2012). 10.1101/gr.128652.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norton, H. L. et al. Genetic evidence for the convergent evolution of light skin in Europeans and East Asians. Mol. Biol. Evol.24, 710–722 (2007). 10.1093/molbev/msl203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamason, R. L. et al. SLC24A5, a putative cation exchanger, affects pigmentation in zebrafish and humans. Science310, 1782–1786 (2005). 10.1126/science.1116238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reis, L. B. et al. Skin pigmentation polymorphisms associated with increased risk of melanoma in a case-control sample from southern Brazil. BMC Cancer20, 1069 (2020). 10.1186/s12885-020-07485-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng, Y. et al. Integrative functional genomic analyses identify genetic variants influencing skin pigmentation in Africans. Nat. Genet.56, 258–272 (2024). 10.1038/s41588-023-01626-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meza-Meza, M. R., Ruiz-Ballesteros, A. I. & de la Cruz-Mosso, U. Functional effects of vitamin D: From nutrient to immunomodulator. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.62, 3042–3062 (2022). 10.1080/10408398.2020.1862753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolf, S. T., Dillon, G. A., Alexander, L. M., Jablonski, N. G. & Kenney, W. L. Skin pigmentation is negatively associated with circulating vitamin D concentration and cutaneous microvascular endothelial function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.323, 490–498 (2022). 10.1152/ajpheart.00309.2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Branicki, W., Brudnik, U. & Wojas-Pelc, A. Interactions between HERC2, OCA2 and MC1R may influence human pigmentation phenotype. Ann. Hum. Genet.73, 160–170 (2009). 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00504.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holick, M. Vitamina D deficiency. N Engl J Med357, 266–281 (2007). 10.1056/NEJMra070553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sturm, R. A. Molecular genetics of human pigmentation diversity. Hum. Mol. Genet.18, R9–R17 (2009). 10.1093/hmg/ddp003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sturm, R. A. & Duffy, D. L. Human pigmentation genes under environmental selection. Genome Biol.13, 248 (2012). 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucock, M. D. et al. Biophysical evidence to support and extend the vitamin D-folate hypothesis as a paradigm for the evolution of human skin pigmentation. Am. J. Hum. Biol. Off. J. Hum. Biol. Counc.34, e23667 (2022). 10.1002/ajhb.23667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brenner, M. & Hearing, V. J. The protective role of melanin against UV damage in human skin. Photochem. Photobiol.84, 539–549 (2008). 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00226.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Unravelling the molecular mechanisms of skin color diversity in Africans. Nat. Genet.56, 200–201 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Natale, C. A. et al. Sex steroids regulate skin pigmentation through nonclassical membrane-bound receptors. elife10.7554/eLife.15104 (2016). 10.7554/eLife.15104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu, J., Bitsue, H. K. & Yang, Z. Skin colour: A window into human phenotypic evolution and environmental adaptation. Mol. Ecol.33, e17369. 10.1111/mec.17369 (2024). 10.1111/mec.17369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository at 10.5281/zenodo.12707833.