Abstract

Objective

Pulp regeneration with bioactive dentin-pulp complex has been a research hotspot in recent years. Stem cell therapy provided an interest strategy to regenerate the dental-pulp complex. Hence, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of photosensitive gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) hydrogel encapsulating dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) for dental pulp regeneration in vitro.

Methods

First, the AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were prepared by lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethyl-benzoyl phosphinate (LAP) initiation via blue–light emitting diode light. The physical and chemical properties of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were comprehensively analysed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and mechanical characterisation, such as swelling ability, degradation properties, and AgNP release profile. Then, AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels encapsulated DPSCs were used to establish an AgNPs@GelMA biomimetic complex, further analysing its biocompatibility, antibacterial properties, and angiogenic capacity in vitro.

Results

The results indicated that GelMA hydrogels demontrated optimal characteristics with a monomer:LAP ratio of 16:1. The physico-chemical properties of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels did not change significantly after loading with AgNPs. There was no significant difference in AgNP release rate amongst different concentrations of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels. Fifty to 200 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels could disperse E faecalis biofilm and reduce its metabolic activity . Furthermore, cell proliferation was arrested in 100 and 200 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels. The inhibition of 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels on E faecalis biofilm was above 50%, and the cell viability of the hydrogels was higher than 90%. The angiogenesis assay indicated that AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels encapsulating DPSCs could induce the formation of capillary-like structures and express angiogenic markers CD31, vascular endothelial growth factor , and von willebrand factor (vWF) in vitro.

Conclusions

Results of this study indicate that 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels encapsulating DPSCs had significant antibacterial properties and angiogenic capacity, which could provide a significant experimental basis for the regeneration of the dentin-pulp complex.

Key words: Hydrogels, Dental pulp stem cells, Silver nanoparticles, Angiogenesis, Dental pulp regeneration

Introduction

According to the statistical data of the fourth national oral health epidemiological survey, in the past decade, the prevalence of dental caries in deciduous teeth and young permanent teeth has been increasing yearly in China.1 Dental caries, if left untreated, will expose the pulp tissue to the surrounding inflammatory microenvironment, causing pulpitis and pulp necrosis. The clinical standard care of pulpitis is root canal treatment, which removes the entire dental pulp and fills with materials to permanently eliminate infection.2 However, the pulpless tooth has no sensory, nutritional, defensive, and reparative functions as well as decreased mechanical properties. Moreover, nearly 36% of the pulpless teeth demonstrate periapical pathology,3 and their long-term prognosis is alos poor.4,5 Therefore, functional regeneration of dental pulp in the pulpless tooth has been of immnse interest to both researchers and clinicians.

In the past decade, with the rapid development of stem cells and tissue engineering technology, stem cell–based therapy has provided an attractive strategy for the regeneration of pulp-dentin complex in the pulpless tooth. Dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) possess mesenchymal stem cell–like properties and have advantages such as source-abundant, readily available, ethically uncontroversial, and low-immunogenicity characteristics.6, 7, 8 As for experiments in dental pulp regeneration in vivo, some studies have shown that DPSCs were able to differentiate into odontoblastlike and endotheliumlike cells to reconstruct the structure of the pulp-dentin complex.9, 10, 11 In addition, DPSCs had the ability to proliferate rapidly and maintain a good stemness, even if the culture medium without the addition of animal serum or exogenous growth factors in vitro.12,13 Thus, DPSCs can provide the required number of cells in the application of stem cell–based therapy for dental pulp regeneration in a short period of time. However, the root canal system presented an anatomically complex 3-dimensional (3D) structure; using DPSCs alone would be placed in a 2-dimensional (2D) growth microenvironment, which could not represent the actual microenvironment where transplanted cells resided in the injured site.14,15 Moreover, once the oral bacteria invaded the dentinal tubules and colonised to form biofilms, would present high resistance to irrigants and medicaments, such as sodium hypochlorite and calcium hydroxide, which might induce the failure of implanted stem cell proliferation and differentiation.16 Therefore, we attempted to apply appropriate biological materials and antimicrobial agents to create a suitable microenvironment for the growth, proliferation, and differentiation of DPSCs.

Gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) hydrogel, which was modified by grafting of methacrylic anhydride onto gelatin, had good biocompatibility and biodegradability as well as great mechanical properties. GelMA hydrogel also presented injectable and photosensitive characteristics and was widely used in the field of tissue engineering.17,18 In addition, the light cross-linking property of GelMA hydrogel enabled 3D loading of live cells, which could be used for constructing bionic tooth germ.19 Results of our previous study indicated that DPSCs had great survival and proliferation rate in GelMA hydrogel whether in vitro or in vivo. Meanwhile, transplanted DPSCs also had an effective differentiation capability in injured sites, which would promote the repair and regeneration of damaged tissue.6,20 Therefore, GelMA hydrogel could be used as an ideal scaffold material, encapsulating DPSCs for dental pulp regeneration.

At present, the to control of bacterial infection is the main reason for to induce the root canal treatment failure. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), a broad-spectrum bactericide, had strong bactericidal effects on fungi and viruses.21,22 AgNPs possessed high affinity with microorganisms due to the electrostatic attraction between the negative charge of the bacteria membrane and the positive charge of the AgNPs. After subsequent penetration, AgNPs locally release Ag+ ions to induce antibacterial effects in bacterial death.23,24 Furthermore, AgNPs had significant antimicrobial activities at low concentrations and would not readily develop bacterial resistance.25,26 In addition, although AgNPs were toxic to bacteria, but had nearly no dangerous to mammalian cells.27 Therefore, AgNPs could be applied for the treatment of irreversible pulpitis and secondary root canal infection as its broad-spectrum antibacterial properties and good cytocompatibility.

In this study, we attempted to prepare and evaluate a new type of AgNPs@GelMA antibacterial hydrogel via photo-cross-linking with blue–light emitting diode (LED). Then, we chose this AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel to 3D-encapsulate DPSCs and further analysed its compatibility, antibacterial properties, and angiogenesis in vitro, which might provide the theoretical and experimental basis for clinical transformation of pulp-dentin complex regeneration of pulpless teeth.

Materials and methods

The preparation of GelMA hydrogel

The synthesis of GelMA macromer and hydrogels is shown in Figure S1. As previously reported,6 lyophilised GelMA and blue light initiator, lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethyl-benzoyl phosphinate (LAP), were dissolved in phosphate balanced solution (PBS) at 50 ℃ at various proportions (4:1, 8:1, and 16:1 w/w respectively) to obtain a clear and transparent solution. The mixture solution was then transferred into polytetrafluoroethylene shape molds and cross-linked to obtain GelMA hydrogel blocks under a blue-LED light source (420–515 nm, 1000–1200 mW/cm2, 20 mm distance). These cross-linked GelMA hydrogel blocks were used in the further analyses.

In this study, the GelMA hydrogel was constructed using UV-light initiation in the control group. Briefly, the GelMA powder was completely dissolved in PBS at 50 ℃ (w/v), and 0.5 g/mL of Irgacure 2959 was added to obtain a 10% GelMA solution. Finally, the mixture was initiated by UV-light (365 nm, 1000–1200 mW/cm2, 20 mm distance) to form the control hydrogel blocks.

The detection of AgNPs cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity of AgNPs was evaluated by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. Briefly, the DPSCs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) suspensions were seeded in 96-well plates (3 × 103 cells/well), respectively. After 24 hours, culture medium was replaced with the fresh culture medium which supplemented with AgNPs at gradient concentrations (12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 600, and 800 μg/mL). Further, 24-hour and 72-hour cytotoxicity was assessed via CCK-8 kit (Dojindo Molecular Technologies). Finally, optical density (OD) of the samples was detected by an absorbance microplate reader at 450 nm (Varioskan LUX, Thermo Fisher).

DPSCs were obtained, characterised, and cultured as previously described.6 HUVECs were purchased from ATCC and cultured as previously described.28

The preparation of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels

To construct AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels, 0.01 g/mL of AgNPs solution was dispersed in GelMA/LAP solution (16:1, w/w) at different ratios (1:50–1:400, v/v). Then, the mixture solution was poured into shape moulds and cross-linked by blue-LED light.

The characteristics of GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels

The physical and chemical properties of GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were evaluated by the detection of scanning electron microscopy (SEM), mechanical characteristic, swelling ability, and degradation analysis. The morphology and pore structure of GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were evaluated by SEM (H-7500, Hitachi). The rheological property of GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels was analysed by a DHR-1 rheometer (TA Instruments). The storage modulus (G′) of GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels was detected in the oscillatory mode with a parallel configuration (8 mm in diameter) at 37 °C. The gap was set as 1.0 mm between 2 plates. The storage modulus (G′) and the loss modulus (G′′) of GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were tested by dynamic frequency sweep test with a frequency range of 0.01–10 Hz and a fixed strain of 0.1%. The swelling and degradation properties of GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were investigated by conventional gravimetric method, as previously described.6

The release profile of AgNPs

The release properties of AgNPs from AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels in vitro were evaluated as the previously described.29 Briefly, 100 μL of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels was immersed in 300 μL of PBS and further oscillated in the shaker at 37 °C, 180 rpm. At established time points (1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 days), the supernatants were collected and the AgNP concentrations were quantified by an absorbance microplate reader (Varioskan LUX, Thermo Fisher) at 412 nm.

The cytocompatibility of GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels

The cytocompatibility of GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels was analysed by the CCK-8 and live/dead assays with DPSCs and HUVECs separately. DPSCs or HUVECs (5 × 105 cell/mL) were resuspended in GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA gel solutions at density. Then, 50 μL/well cellular gel solution was plated into the 96-well plates and photo-cross-linked via blue-LED light. To determine cell proliferation, at designed time points, 10% CCK-8 solution was added into the 96-well plates and the OD values at 450 nm were measured with an absorbance microplate reader. To assess cell viability, live/dead viability/cytotoxicity kit (Invitrogen) was used. At predetermined time points, the samples were photographed using fluorescence microscope (Axiovert A1, Carl Zeiss) and the percentage of live cells was quantified using Image J. All tests were performed in triplicate with 4 parallel samples.

The antibacterial properties of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels

The antibacterial properties of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were systematically assessed with 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT), SEM, live/dead, and colony-forming unit (CFU) assays. Briefly, E faecalis (ATCC 29212) was cultured in brain-heart infusion (BHI; OXOID) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and inoculated into 48-well plates at a density of 1 × 107 CFU/mL to form overnight biofilm. AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were placed into 48-well plates to incubate with biofilm for another 48 hours. In addition, 2% (v/v) chlorhexidine solution (CHX) was used as a positive control. MTT assay was used to evaluate the metabolic activity of E faecalis biofilm and SEM was employed to analyse the morphology and structure of biofilm.30

Moreover, the bacteria viability of E faecalis biofilm was evaluated by the BacLight live/dead bacterial viability kit (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer's instruction. As for the CFU assay, the E faecalis biofilm was sonicated and gradient diluted, and then the bacterial suspension was plated onto BHI agar plates to incubate for 24 hours. Finally, the CFU was observed and pictured by light microscopy (TS100, Nikon).

The vessel formation of DPSCs in AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels

The vessel formation of DPSCs in AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels was evaluated.7,8 After 2 and 7 days’ induction, the cells’ cytoskeleton and nuclei were treated with Phalloidin-TRITC (1:200) and 4,6-diamidino-2- phenylindole, respectively. Meanwhile, on day 7, the cells were immunofluorescent-stained with the primary antibodies CD31 (1:200, Abcam, GBR), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (1:300, Affinity), and von Willebrand factor (vWF; 1:250, Abcam, GBR). The pictures were taken using a fluorescence microscope, and the tube length and number of junctions were calculated using GraphPad Prism 6.0.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS 19.0. The data in each group were expressed as mean ± SD (n ≥ 3). The comparison of 2 groups used the Student t test. Three or more groups were compared using 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey test or Dunnett post hoc test. The test level α = 0.05, P < .05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

Results

The properties of GelMA hydrogels via blue-LED light

According to Figure S2, compared to the control group using DPSCs cultured in normal culture medium from day 1 to day 5, the results of CCK-8 and live/dead assays suggested that the proliferation of DPSCs was not affected by UV irradiation with a wavelength of 365 nm, 60 sseconds, 20 mW/cm2 (UV group). However, the viability of DPSCs was moderately and severely inhibited by pure UV initiator Irgacure 2959 (Irgacure 2959 group) and Irgacure 2959 with UV irradiation (photoinitiation group), respectively. There was a significant difference between the control and Irgacure 2959 groups as well as between the control and photoinitiation groups.

As shown in Figure 1, the SEM data indicated that GelMA hydrogels, whether initiated by UV light (control group) or cross-linked by blue-LED light (GelMA:LAP groups including GelMA:LAP 4:1, GelMA:LAP 8:1, and GelMA:LAP 16:1), both had 3D pore structures (Figure 1A). Furthermore, the pore sizes were not different between the control and GelMA:LAP groups (Figure 1B). Meanwhile, the other physicochemical properties (eg, swelling ability, mechanical characteristics, and degradability in vitro) of hydrogels in GelMA:LAP groups had shown similar results to those in the control group (Figure 1C–E).

Fig. 1.

The physicochemical properties of gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) hydrogels cross-linked by blue–light emitting diode light. A, The morphology of GelMA hydrogels. B, The pore size of GelMA hydrogels. C, The swelling ratio of GelMA hydrogels. D, The mechanical properties of GelMA hydrogels. E, The degradability of GelMA hydrogels.

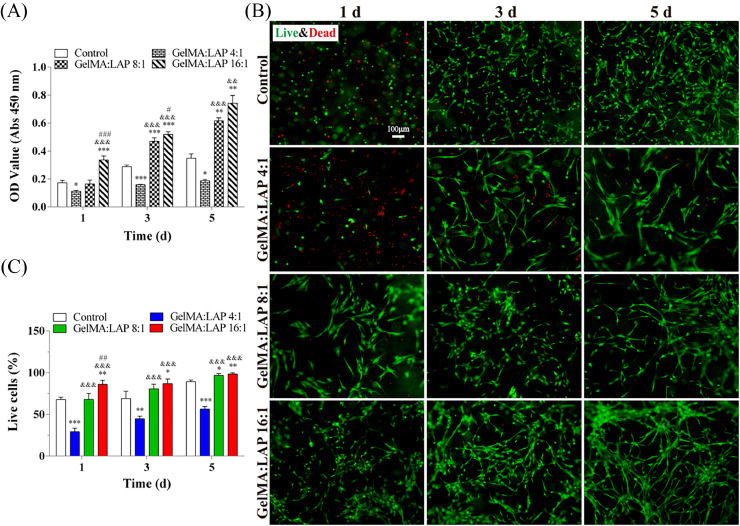

Moreover, the results of GelMA hydrogel cytocompatibility are shown in Figure 2; the order of DPSCs’ viability in GelMA hydrogels was GelMA:LAP 16:1 groupGelMA:LAP 8:1 groupcontrol groupGelMA:LAP 4:1 group. There was a significant difference between the GelMA:LAP 16:1 and control groups as well as between the GelMA:LAP 8:1 and control groups. In addition, the GelMA:LAP 4:1 group had a negative effect on DPSC growth compared to that of the control group (Figure 2A). The results of live/dead assay indicated that DPSCs had great proliferation in GelMA:LAP 16:1 and GelMA:LAP 8:1 groups from day 1 to day 5 (Figure 2B). The number of live cells was the highest in the GelMA:LAP 16:1 group, and the difference was statistically significant between the GelMA:LAP 16:1 and control groups (Figure 2C). Therefore, the 16:1 ratio of GelMA:LAP was chosen to construct the GelMA hydrogel via blue-LED light in the following experiments.

Fig. 2.

The biocompatibility of gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) hydrogels cross-linked by blue–light emitting diode light. A, Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. B, Live/dead staining. C, Quantitative measurements of the live cells. *P < .05, ⁎⁎P < .01, ⁎⁎⁎P < .001 vs the control group. &P < .05, &&P < .01, &&&P < .001 vs the GelMA:LAP 4:1 group. #P < .05, ##P < .01, ###P < .001 vs the GelMA:LAP 8:1 group. LAP, lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethyl-benzoyl phosphinate.

The detection of AgNPs cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity of AgNPs co-cultured with DPSCs and HUVECs was evaluated by CCK-8 assay (Figure 3A and B). Following 24-hour culture, the cell viability of DPSCs and HUVECs decreased, as the concentration of AgNPs was ≥100 μg/mL. The difference had obvious significance compared to that of the control group, whereas there was no significant difference between the control and the experimental groups when the concentration of AgNPs was ≤600 μg/mL and ≤200 μg/mL at 72 hours for DPSCs and HUVECs, respectively. Results indicated that the tolerance of HUVECs to AgNPs was worse than that of DPSCs and the cytotoxicity of AgNPs weakened with the culture time, but the high concentration of AgNPs had a serious effect on cell viability and the cell proliferation was difficult to recover.

Fig. 3.

The cytotoxicity and release profile of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). The cytotoxicity of AgNPs at different concentrations to dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) (A) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (B). *P < .05, ⁎⁎P < .01, ⁎⁎⁎P < .001 vs the control group. C, Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-vis) absorption spectra and the standard curve of AgNPs. D, The release profile of AgNPs from AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels in 9 days.

The release profile of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels via blue-LED light

In this study, the absorption peak of AgNPs’ suspension was detected at 412 nm by an absorbance microplate reader (Varioskan LUX, Thermo Fisher; Figure 3C). The cumulative release of AgNPs from the different concentrations of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels showed a similar trend with time. The rapid release of AgNPs from AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels existed on day 1; the release amounts of AgNPs from 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 mg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were 0.43 ± 0.05, 2.22 ± 1.35, 3.91 ± 2.11, and 15.80 ± 2.16 μg/mL, respectively. The release rate of AgNPs from AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels gradually slowed down on day 3, and the AgNP release reached a plateau on day 5. The final cumulative release amounts of AgNPs from 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 mg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were 2.63 ± 0.61, 5.34 ± 1.11, 8.43 ± 0.48, and 21.18 ± 2.52 μg/mL, respectively. The results indicated that the release rates of AgNPs from AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels were not significantly different amongst the groups, and the final cumulative release of AgNPs was positively correlated with the amount of original loading (Figure 3D).

The antibacterial property of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels via blue-LED light

Considering that AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels had the characteristics of sustained-release AgNPs, the biosafety concentrations of AgNPs (25 and 50 μg/mL) and the potential cytotoxicity concentrations of AgNPs (100 and 200 μg/mL) were selected to clarify its antibacterial effect and biocompatibility. As shown in Figure 4A, the morphology of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels was a short cylinder with a diameter of 7 mm and a height of 3 mm, and the colour gradually became darker with the increase of AgNP concentration. The metabolic activity of E faecalis biofilm was measured by MTT assay (Figure 4B). The results showed that 25 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA had no notable effect on the metabolic activity of E faecalis biofilm, whereas 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels could significantly inhibit the biofilm activity of E faecalis. Moreover, there was no significant difference between the positive control group (2% CHX solution) and 100 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel as well as 200 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel. However, the effect of antibiofilm viability existed obviously significant difference between the 2% CHX solution and 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel.

Fig. 4.

The morphology and antimicrobial performance of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels. A, The morphology of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels in general. B, The effect of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels on the metabolic activity of E faecalis biofilm was analysed by 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT) assay. ⁎⁎P < .01, ⁎⁎⁎P < .001 vs the negative control group (gelatin methacrylate [GelMA] group). ##P < .01, ###P < .001 vs the positive control group (2% chlorhexidine (CHX) group). C, The dispersion effect of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels on E faecalis biofilm was evaluated by scanning electron microscopy. D, The effect of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels on the bacteria viability of E faecalis biofilm was detected by live/dead assay. E, Colony-forming unit of E faecalis biofilm.

The surface morphology of E faecalis biofilm was characterised by SEM (Figure 4C). The results indicated that 25 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel had no significant dispersion effect on E faecalis biofilm. However, the biofilm thickness of E faecalis was decreased by 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels. In addition, the effect of 100 and 200 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels on the dispersion of E faecalis biofilm was stronger than that of 2% CHX solution. The trend of the biofilm characterisation was similar to that of the MTT assay.

Moreover, the live/dead staining and CFU assay results showed that the total live bacteria and CFU numbers both obviously decreased with the increase of AgNP concentration from 50 to 200 μg/mL in AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels compared to that of the control group (GelMA group). The results indicated that 50 to 200 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels had a significant inhibition effect on the bacterial viability of E faecalis biofilm (Figure 4D and E).

An ideal antibacterial hydrogel should have the capability to inhibit bacterial activity as well as to disperse the bacterial biofilms. Therefore, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels was used for further determination of its physicochemical properties and biocompatibility.

The properties of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels via blue-LED light

As for the characterisation of physicochemical properties of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels (Figure 5), results indicated that AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels had porous structures. Meanwhile, the pore size of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels had no significant difference compared to that of the pure GelMA hydrogel. Moreover, the swelling properties, the elasticity, and the degradation properties were also not significantly different between the pure GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels. Therefore, the microstructure and physicochemical properties of GelMA hydrogel were not obviously affected by encapsulating AgNPs, suggesting that AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels also had great physicochemical properties.

Fig. 5.

The physicochemical properties of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels. A, The morphology of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels. B, The pore size of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels. C, The swelling ratio of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels. D, The mechanical properties of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels. E, The degradability of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels.

As shown in Figure 6 and S3, the cytocompatibility of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels co-cultured with DPSCs and HUVECs was analysed by CCK-8 and live/dead assays. Results indicated that no toxicity existed in 50 μg/mL of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel co-cultured with DPSCs or HUVECs, whereas cell proliferation was obviously prohibited in 100 and 200 μg/mL of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels (Figure 6A and S3A). The DPSCs had prolonged morphology and the HUVECs formed the tubes in 50 μg/mL of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel as well as in the pure GelMA hydrogel (Figure 6B and S3B). Moreover, the number of live cells was not significantly different between the pure GelMA and 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels (Figure 6C and S3C).

Fig. 6.

The biocompatibility of AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels with dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs). A, Live/dead staining. B, Quantitative measurements of the live cells. C, Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. *P < .05, ⁎⁎P < .01, ⁎⁎⁎P < .001 vs the gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) group. &P < .05, &&P < .01, &&&P < .001 vs the 50 μg/mL silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) group. #P < .05, ##P < .01, ###P < .001 vs the 100 μg/mL AgNPs group.

In addition, Figure S4 shows that 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel had great cytocompatibility to DPSCs as well as HUVECs. Compared to 2% CHX solution, the inhibition rate of E faecalis biofilm was 51.34% ± 2.58% in 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel. Therefore, after comprehensive comparison, 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA antibacterial hydrogel, with better biological safety, was selected for vessel formation study.

The vessel formation property of DPSCs loaded with AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels via blue-LED light

Figure S5 shows that, after induction, DPSCs possessed significant tube formation properties, which was similar to that of HUVECs. Meanwhile, AgNPs had no disadvantage in the tube formation of DPSCs (Figure 7A) and the tubule length and number of junctions were not different between the GelMA and AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels (Figure 7B and C). Moreover, 7 days after induction, 3D networks existed in AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel, resembling the capillary structures (Figure 7D). Furthermore, the angiogenic markers CD31, VEGF, and vWF were also positively expressed in DPSCs which were co-cultured with AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel for 7 days’ induction (Figure 7e).

Fig. 7.

The angiogenic capacity of AgNPs@GelMA co-cultured with dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs). A, The angiogenic potential of AgNPs@GelMA co-cultured with DPSCs for 2 days. B, Measurement of tubule length. C, Analysis of number of junctions. D, The tube formation of AgNPs@GelMA co-cultured with DPSCs for 7 days. E, The expression of angiogenic markers cluster of differentiation-31 (CD31), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and von willebrand factor (vWF) of AgNPs@GelMA co-cultured with DPSCs for 7 days.

Discussion

In this study, GelMA hydrogel had the capability to 3D-encapsulate DPSCs due to its cross-linking property. However, the photoinitiator that was used to initiate GelMA monomer gelation could produce a large number of free radicals to damage the cell membranes or drive the cell cycle into G0 phase.31 Therefore, an appropriate photoinitiator was very important in the construction of GelMA hydrogel carrying DPSCs to guarantee cells’ 3D growth and proliferation. Irgacure 2959, which was the commonly used photoinitiator, had poor water solubility and was oxygen-sensitive for photo-cross-linking. Meanwhile, the initiation of UV light carried a potential risk for damaging the cellular DNA.29 In our study, results also indicated that Irgacure 2959 had poor cytocompatibility as well as obvious toxicity to DPSCs (Figure S2). LAP, a low-toxicity initiator, had been widely used to initiate gelation to obtain the cell-laden hydrogels with high cell viability.32,33 In our study, a series of GelMA hydrogels was cross-linked by LAP initiation via blue-LED light, and the hydrogels had great physical and chemical properties and good cytocompatibility. As the ratio of GelMA:LAP was 16:1, the hydrogel had the best characteristics, indicating that this hydrogel was suitable for carrying the active factors or live cells, such as DPSCs (Figure 1 and 2).

AgNPs had strong antibacterial activity due to their greater surface area and smaller particle diameter.34,35 However, AgNPs tended to spontaneously agglomerate and settle to result in lower antibacterial efficacy at the solution environment.36 In this study, the AgNPs@GelMA antibacterial hydrogels were prepared by mixing AgNP powder directly with GelMA monomer. These hydrogels not only reduced the agglomerating probability of AgNPs but also enhanced AgNPs’ sustained release, which prolongs antibacterial time (Figure 3). Moreover, the addition of AgNPs did not affect the physical and chemical properties of hydrogels, and the AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels also had a porous structure and great mechanical characteristics, which was the same as that of the GelMA hydrogel (Figure 5).

E faecalis, a G+ and facultative anaerobic bacteria, had been found to possess high reinfection (up to 24%–77%) after root canal therapy and was a major pathogen of refractory and secondary root canal infections.37 AgNPs had broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, and 94 ppm AgNP solution had a stronger effect than that of 2% CHX on the dispersion of E faecalis biofilm.38 Moreover, the addition of AgNPs to the root canal sealants could effectively inhibit the formation of bacterial biofilm, thereby reducing the risk of secondary infection in the root canal system.39 In our study, AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels from 50 to 200 μg/mL had excellently antibacterial activity as well as good dispersing effects on E faecalis biofilm (Figure 4), which could be applied in root canal therapy and avoid secondary infection.

However, the results of cytocompatibility testing indicated that 100 and 200 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels had toxic effects on the survival and proliferation of DPSCs and HUVECs, whereas there was no difference between the 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA and GelMA hydrogels (Figure 6 and S3). Meanwhile, DPSCs had the ability to secrete a variety of pro-angiogenic growth factors (eg, VEGF, stromal cell derived factor-1α and platelet-derived growth factor-BB), promoted the formation of new vessel structures, and played an important role in dental pulp tissue engineering.8,40,41 In addition, 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel encapsulating DPSCs was induced by EBM-2 to form many vessel-like structures and positively express endothelial cell–related markers such as CD31, VEGF, and vWF (Figure 7). Therefore, 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel including DPSCs was a bioactive compound, had great antibacterial property and good angiogenic activity, and was suitable for the repair and regeneration of dental pulp tissue.

Conclusions

In this study, we first prepared the AgNPs@GelMA hydrogels by LAP initiation via blue-LED light and 3D-encapsulated DPSCs to establish AgNPs@GelMA biomimetic complex and further analysed its antibacterial property and angiogenic capacity in vitro. Our research indicated that 50 μg/mL AgNPs@GelMA hydrogel encapsulating DPSCs had great antibacterial property and angiogenic capacity and could provide theoretical support and an experimental basis for its clinical translation for dentin-pulp complex regeneration.

Conflict of interest

None disclosed.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Yan He, Yanni Zhang, and Fengting Hu performed the majority of experiments and analysed the data. Haichao Xu and Na Dong collected the data and performed statistical analysis. Min Chen and Zhiqiang Lin cultured E faecalis. Chen Zhang and Yunfan Hu cultured HUVECs. Ben Wang and Yejian Li cultured DPSCs. Youjian Peng revised the manuscript. Qingsong Ye, Yan He, and Lihua Luo designed and coordinated the research. Lihua Luo wrote the paper. Yan He, Yanni Zhang, and Fengting Hu contributed equally to this work. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LGF21H140007, Zhejiang Province Program of the Medical and Health Science and Technology under Grant No. 2022KY218, Wenzhou Basic Research Project under Grant No. H20220010, and the Stomatological School of Wenzhou Medical University Grant KYQD2023007.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.identj.2024.01.017.

Contributor Information

Qingsong Ye, Email: qingsongye@whu.edu.cn.

Lihua Luo, Email: luolihua81@126.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- 1.Gao Y, Hu T, Zhou X, et al. Dental caries in Chinese elderly people: findings from the 4th National Oral Health Survey. Chin J Dent Res. 2018;21(3):213–220. doi: 10.3290/j.cjdr.a41077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leon-Lopez M, Cabanillas-Balsera D, Martin-Gonzalez J, Montero-Miralles P, Sauco-Marquez JJ, Segura-Egea JJ. Prevalence of root canal treatment worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J. 2022;55(11):1105–1127. doi: 10.1111/iej.13822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pak JG, Fayazi S, White SN. Prevalence of periapical radiolucency and root canal treatment: a systematic review of cross-sectional studies. J Endod. 2012;38(9):1170–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angelopoulos I, Trigo C, Ortuzar MI, Cuenca J, Brizuela C, Khoury M. Delivery of affordable and scalable encapsulated allogenic/autologous mesenchymal stem cells in coagulated platelet poor plasma for dental pulp regeneration. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):435. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02118-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel JC, Cai J, Yin GB, Alex W. Root canal filled versus non-root canal filled teeth: a retrospective comparison of survival times. J Public Health Dent. 2005;65 doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2005.tb02792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo L, He Y, Jin L, et al. Application of bioactive hydrogels combined with dental pulp stem cells for the repair of large gap peripheral nerve injuries. Bioact Mater. 2021;6(3):638–654. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo L, Zhu Q, Li Y, et al. Application of thermosensitive-hydrogel combined with dental pulp stem cells on the injured fallopian tube mucosa in an animal model. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1062646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo L, Xing Z, Liao X, et al. Dental pulp stem cells-based therapy for the oviduct injury via immunomodulation and angiogenesis in vivo. Cell Prolif. 2022;55(10):e13293. doi: 10.1111/cpr.13293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu X, Liang C, Gao X, et al. Adipose tissue-derived microvascular fragments as vascularization units for dental pulp regeneration. J Endod. 2021;47(7):1092–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2021.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou T, Rong M, Wang Z, et al. Conditioned medium derived from 3D tooth germs: a novel cocktail for stem cell priming and early in vivo pulp regeneration. Cell Prolif. 2021;54(11):e13129. doi: 10.1111/cpr.13129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janebodin K, Chavanachat R, Hays A, Reyes Gil M. Silencing VEGFR-2 hampers odontoblastic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.665886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zainal Ariffin SH, Kermani S, Zainol Abidin IZ, et al. Differentiation of dental pulp stem cells into neuron-like cells in serum-free medium. Stem Cells Int. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/250740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piva E, Tarle SA, Nor JE, et al. Dental pulp tissue regeneration using dental pulp stem cells isolated and expanded in human serum. J Endod. 2017;43(4):568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Souza AG, Silva IBB, Campos-Fernandez E, et al. Comparative assay of 2D and 3D cell culture models: proliferation, gene expression and anticancer drug response. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24(15):1689–1694. doi: 10.2174/1381612824666180404152304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edmondson R, Broglie JJ, Adcock AF, Yang L. Three-dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell-based biosensors. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2014;12(4):207–218. doi: 10.1089/adt.2014.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghasemi N, Behnezhad M, Asgharzadeh M, Zeinalzadeh E, Kafil HS. Antibacterial properties of aloe vera on intracanal medicaments against enterococcus faecalis biofilm at different stages of development. Int J Dent. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8855277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu W, Wang T, Wang Y, et al. An injectable platform of engineered cartilage gel and gelatin methacrylate to promote cartilage regeneration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.884036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan Y, Chen L, Shi Z, Chen J. Micro/nanoarchitectonics of 3D printed scaffolds with excellent biocompatibility prepared using femtosecond laser two-photon polymerization for tissue engineering applications. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2022;12(3) doi: 10.3390/nano12030391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Man K, Barroso IA, Brunet MY, et al. Controlled release of epigenetically-enhanced extracellular vesicles from a GelMA/nanoclay composite hydrogel to promote bone repair. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2) doi: 10.3390/ijms23020832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S, Luo L, He Y, et al. Dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes alleviate cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion injury through suppressing inflammatory response. Cell Prolif. 2021;54(8):e13093. doi: 10.1111/cpr.13093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karageorgou D, Zygouri P, Tsakiridis T, et al. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles with high antibacterial activity using cell extracts of cyanobacterium Pseudanabaena/Limnothrix sp. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2022;12(13) doi: 10.3390/nano12132296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanmuganathan R, Brindhadevi K, Al-Ansari MM, Al-Humaid L, Barathi S, Lee J. In vitro investigation of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Gracilaria veruccosa - a seaweed against multidrug resistant Staphylococcusaureus. Environ Res. 2023;227 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.115782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song B, Zhang C, Zeng G, Gong J, Chang Y, Jiang Y. Antibacterial properties and mechanism of graphene oxide-silver nanocomposites as bactericidal agents for water disinfection. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016;604:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabaran AF, Matea CT, Mocan T, et al. Silver nanoparticles for the therapy of tuberculosis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:2231–2258. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S241183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thammawithan S, Talodthaisong C, Srichaiyapol O, Patramanon R, Hutchison JA, Kulchat S. Andrographolide stabilized-silver nanoparticles overcome ceftazidime-resistant Burkholderia pseudomallei: study of antimicrobial activity and mode of action. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):10701. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14550-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abo-Shama UH, El-Gendy H, Mousa WS, et al. Synergistic and antagonistic effects of metal nanoparticles in combination with antibiotics against some reference strains of pathogenic microorganisms. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:351–362. doi: 10.2147/idr.S234425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez-Duran F, Acosta-Torres LS, Serrano-Diaz PN, et al. Toxicity and antimicrobial effect of silver nanoparticles in swine sperms. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2020;66(4):281–289. doi: 10.1080/19396368.2020.1754962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Huang Y, He Y, et al. Myocardial protection by heparin-based coacervate of FGF10. Bioact Mater. 2021;6(7):1867–1877. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdelmoneim D, Porter G, Duncan W, et al. Three-dimensional evaluation of the cytotoxicity and antibacterial properties of alpha lipoic acid-capped silver nanoparticle constructs for oral applications. Nanomaterials. 2023;13(4) doi: 10.3390/nano13040705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia M, Zhuo N, Ren S, et al. Enterococcus faecalis rnc gene modulates its susceptibility to disinfection agents: a novel approach against biofilm. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):416. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02462-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fedorovich NE, Oudshoorn MH, van Geemen D, Hennink WE, Alblas J, Dhert WJ. The effect of photopolymerization on stem cells embedded in hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2009;30(3):344–353. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu H, Jazzmin C, Srikumar K, Xu C. Effects of Irgacure 2959 and lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate on cell viability, physical properties, and microstructure in 3D bioprinting of vascular-like constructs. Biomed Mater. 2020;15 doi: 10.1088/1748-605X/ab954e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasaki H, Rothrauff BB, Alexander PG, et al. In vitro repair of meniscal radial tear with hydrogels seeded with adipose stem cells and TGF-beta3. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(10):2402–2413. doi: 10.1177/0363546518782973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raza MA, Kanwal Z, Rauf A, Sabri AN, Riaz S, Naseem S. Size- and shape-dependent antibacterial studies of silver nanoparticles synthesized by wet chemical routes. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2016;6(4) doi: 10.3390/nano6040074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chellakannu M, Panneerselvam T, Rajeshkumar S. Kinetic study on the herbal synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its antioxidant and antibacterial effect against gastrointestinal pathogens. Int J Res Pharm Sci. 2018 doi: 10.26452/ijrps.v10i1.1817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin S, Xie M, Cao S, et al. Insight into the antibacterial resistance of graphdiyne functionalized by silver nanoparticles. Cell Prolif. 2022;55(5):e13236. doi: 10.1111/cpr.13236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stuart CH, Schwartz SA, Beeson TJ, Owatz CB. Enterococcus faecalis: its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retreatment. J Endod. 2006;32(2):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodrigues CT, de Andrade FB, de Vasconcelos L, et al. Antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles as a root canal irrigant against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm and infected dentinal tubules. Int Endod J. 2018;51(8):901–911. doi: 10.1111/iej.12904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baras BH, Melo MAS, Sun J, et al. Novel endodontic sealer with dual strategies of dimethylaminohexadecyl methacrylate and nanoparticles of silver to inhibit root canal biofilms. Dent Mater. 2019;35(8):1117–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Z, Warner KA, Mantesso A, Nor JE. PDGF-BB signaling via PDGFR-beta regulates the maturation of blood vessels generated upon vasculogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.977725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao X, Chen M, Zhang Y, et al. Platelet lysate promotes proliferation and angiogenic activity of dental pulp stem cells via store-operated Ca2+ entry. Nano TransMed. 2023;2(4) doi: 10.1016/j.ntm.2023.100021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.