Abstract

The study of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) has been commonly reported in the context of cancer immunology. MDSCs play a key role in cancer growth and progression by inhibiting both innate and adaptive immunity. In addition to the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs in cancer, a novel function of MDSCs as osteoclast precursors has recently been attracting attention. Because monocytic-MDSCs (M-MDSCs) are derived from the same myeloid lineage as macrophages, which are osteoclast progenitors, M-MDSCs can undergo differentiation into osteoclasts, contributing to bone destruction not only in the cancer microenvironment but also in inflammatory conditions including obesity and osteoarthritis. Herein, we present details of the technique to evaluate osteoclasts in vitro, as well as specific techniques to isolate M-MDSCs and identify them. This protocol can be easily adapted to isolate M-MDSCs from most pathologic conditions for easy evaluation.

1. Introduction

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells (IMCs) that have the ability to suppress immune activity (Gabrilovich & Nagaraj, 2009; Zhuang et al., 2012). Under normal conditions, IMCs in the bone marrow differentiate into mature macrophages, dendritic cells, and mature granulocytes, and the frequency of MDSCs in the peripheral blood is maintained low (Almand et al., 2001; Ost et al., 2016; Verschoor et al., 2013). On the other hand, in pathological conditions, including cancer and chronic infection, the differentiation of IMCs is partially blocked, resulting in the expansion of the MDSC population (Gabrilovich & Nagaraj, 2009).

MDSCs were first described by the expression of CD11b, and Gr-1 antibodies in tumor-bearing mice, and the cellular origin and nature of the cells have been controversial. MDSCs are divided into monocytic-MDSCs (M-MDSCs; CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6Chigh), and polymorphonuclear MDSCs (PMN-MDSCs; CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Clow) according to their phenotype, but M-MDSCs share common morphologic features with inflammatory monocytes and PMN-MDSCs with neutrophils (Bronte et al., 2016; Dolcetti et al., 2010; Ugel et al., 2012). Since it is difficult to define MDSCs based on phenotype alone, additional evaluation of T cell inhibitory function is essential to define MDSCs (Bronte et al., 2016).

Bone is a dynamic tissue where osteoclasts and osteoblasts work in concert to maintain skeletal integrity throughout the lifespan of the organism. Osteoclasts, which are large, multi-nucleated cells, are derived from the mononuclear lineage of hematopoietic cells and are responsible for bone resorption (Teitelbaum, 2000). In normal bone remodeling, monocytes and macrophages are the major precursors of osteoclasts (Udagawa et al., 1990). To differentiate osteoclast precursors into osteoclasts in vitro, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) are essential (Boyce, Rosenberg, de Papp, & Duong, 2012). RANKL and M-CSF trigger signaling pathways that lead to osteoclastogenesis, and various signaling mechanisms such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) production affect osteoclastogenesis (Boyce et al., 2012; Nakashima & Takayanagi, 2009). Osteoclasts actively synthesize and secrete lysosomal enzymes such as tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and cathepsin K into the bone resorption compartment (Vaananen, Zhao, Mulari, & Halleen, 2000). In this process, osteoclasts are involved in physiological bone remodeling and pathological bone loss (Chambers, 2000; Marino, Logan, Mellis, & Capulli, 2014). Therefore, assessing the osteoclast differentiation and bone destruction capacity of osteoclasts is essential to understand the mechanisms of bone homeostasis and disease (Atkins et al., 2001; McSheehy & Chambers, 1986).

As MDSCs are precursors of macrophages that differentiate into osteoclasts, and their numbers increase in the tumor microenvironment, there is growing evidence that MDSCs can function as osteoclast progenitors in cancer-associated bone destruction (Danilin et al., 2012; Edgington-Mitchell et al., 2015; Sawant et al., 2013; Zhuang et al., 2012). Moreover, several recent studies have reported that MDSCs can function as osteoclast precursors even in pathological conditions with complications related to bone destruction, including periodontitis and osteoarthritis (Kirkwood, Zhang, Thiyagarajan, Seldeen, & Troen, 2018; Kwack, Maglaras, Thiyagarajan, Zhang, & Kirkwood, 2021; Kwack et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2015, 2021). Based on these recent reports, it is clear that M-MDSCs represent a distinct osteoclast precursor population, and therefore targeting M-MDSCs may help to control MDSC-mediated bone-related diseases. Here, we detail a protocol for the isolation and identification of MDSCs and the evaluation of their osteoclastogenic potential. This approach should be adaptable when evaluating osteoclastogenesis in monocyte-derived cells, including M-MDSCs.

2. Materials

2.1. Common disposables (see Note 1)

15 mL Centrifuge Tubes (#430053, Corning)

Petri Dish 60 × 15 mm (#351007, Corning)

0.5 mL Centrifuge Tubes (#AB0350, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

1.5 mL Microcentrifuge Tubes (#69715, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

70 μm Cell Strainer (#431751, Corning)

96 well plate, U bottom (#353077, Corning)

Round-Bottom Polystyrene Tubes with Caps, 5 mL (FASC tube, #38007, Falcon)

Osteo Assay Surface (#3987, Corning)

24-well plate (#3526, Corning)

48-well plate (#3548, Corning)

2.2. Common reagents

RPMI 1640 medium (#10-040-CV, Corning)

MEM alpha media (#12571063, Gibco)

Fetal Bovine Serum (#26140087, Gibco)

Phosphate buffered saline (#10010-023, Gibco)

Penicillin-Streptomycin (#15140148, Gibco)

ACK lysis buffer (#A1049201, Gibco)

FcR Blocking Reagent (#130-092-575, Miltenyi Biotec)

Flow cytometry Staining Buffer (#00-4222-26, Invitrogen)

CD11b-APC (#130-113-231, Miltenyi Biotec)

Ly6C-FITC (#130-111-915, Miltenyi Biotec)

Ly6G-PE (#130-102-392, Miltenyi Biotec)

Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Isolation Kit (#130-094-538, Miltenyi Biotec)

CD3 MicroBead Kit (#130-094-973, Miltenyi Biotec)

CellTrace Violet Cell Proliferation Kit (#C34571, Invitrogen)

Dynabeads Mouse T-Activator CD3/CD28 (#11452D, Gibco)

CD3-APC (#130-109-838, Miltenyi Biotec)

CD4-PE-Cyanine7 (#15370880, eBioscience)

CD8-APC-Vio770 (#130-120-806, Miltenyi Biotec)

Monocyte colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF, #416-ML-010, R&D Systems)

RANKL (#462-TEC-010, R&D Systems)

0.2 M Sodium Acetate solution (#A13184, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

0.2 M Acetic Acid solution (#ACS003-78, BDH labs)

0.3 M Sodium Tartrate (#S-8640, Sigma)

Naphthol AS-MX phosphate disodium salt (#N-5000, Sigma)

FastRed Violet LB salt (#F-3381, Sigma)

15% Ehrlich’s hematoxylin (#26753-01, EMS)

Paraformaldehyde (#J19943-K2, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

Ethanol (#T038181000, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

2.3. Common equipment

TC20 Automated Cell Counter (Bio-Rad)

Humidified incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2)

Centrifuge (capable of spinning 15 mL conical tubes, 5 mL FACS tubes, and 96 well plates)

BD LSRFortessa Cell Analyzer (BD Biosciences)

BD FACSAria Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences)

AutoMACS pro separator (Miltenyi Biotec)

Water bath (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

Image J analysis software

Flowjo v10.9 software

3. Methods

3.1. Isolation of M-MDSCs (see Note 2)

Sacrifice the mouse and disinfect the mouse body surface with 70% ethanol (see Note 3)

Cut the ankle part and dislocate the femur neck to separate the hind limbs of the mouse and cleanly remove the skin and muscles. Separate the femur and tibia by cutting the knee part

Remove both ends of the femur and tibia to expose the bone marrow cavity. Flush the bone marrow using 0.5 mL RPMI 1640 medium (Corning) in a 29-gauge syringe and collect it in a 6 cm Petri dish (see Note 4)

The obtained cell solution is filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer into 15 mL centrifuge tube.

Centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C and discard supernatant

Resuspend the cell pellet with 2 mL of ACK lysis buffer (Gibco) to remove red blood cells, place on ice for 5 min

Add 3 mL of RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Discard supernatant

3.1.1. Using BD FACSAria cell sorter

Resuspend cell pellet in 1 mL of buffer

Take 1 × 106 cells/well in a total 15–18 wells in a 24-well plate

Centrifuge at 1200 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C and discard supernatant

Add 50 μL of FcR Blocking Reagent cocktail (1 μL FcR blocking Reagent, 49 μL staining buffer, Miltenyi Biotec), mix well, and incubate for 10 min on ice

Add anti-CD11b antibody conjugated with APC (Miltenyi Biotec), anti-Ly6C antibody conjugated with FITC (Miltenyi Biotec), and anti-Ly6G antibody conjugated with PE (Miltenyi Biotec), mix well, and incubate for 30 min on ice (4 °C)

Wash cells three times with 5 mL of buffer and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

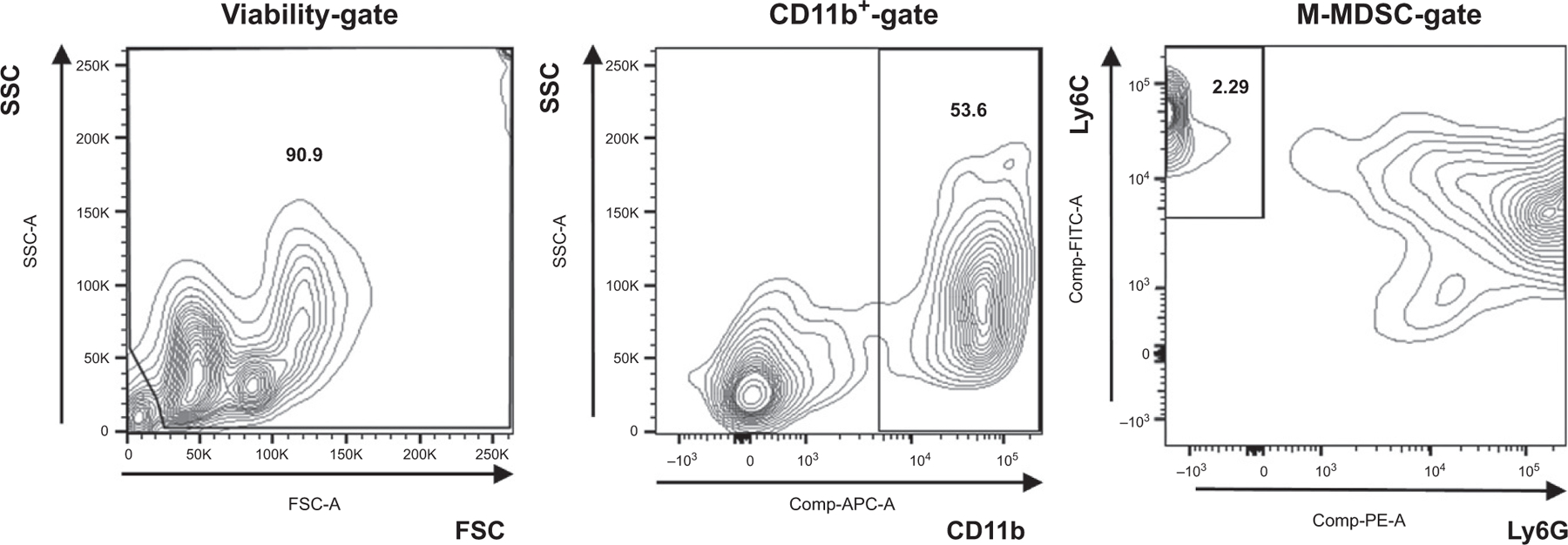

Resuspend the cell pellet with 3 mL of buffer then sorted for CD11b +Ly6G–Ly6Chigh cells using a FACSAria Cell Sorter (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1:

Gating strategy used in cell sorter.

3.1.2. Using myeloid-derived suppressor cell isolation kit (Miltenyi biotech)

Resuspend cell pellet in 350 μL of buffer

Add 50 μL of FcR Blocking Reagent cocktail (1 μL FcR blocking Reagent, 49 μL staining buffer), mix well, and incubate for 10 min on ice

Add 100 μL of Anti-Ly-6G-Biotin, mix well, and incubate for 10 min on ice

Wash cells using 5 mL of buffer and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Aspirate supernatant completely and resuspend cell pellet in 800 μL of buffer

Add 200 μL of Anti-Biotin MicroBeads, mix well, and incubate for 15 min on ice

Wash cells using 10–20 mL of buffer and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Aspirate supernatant completely and resuspend cell pellet in 500 μL of buffer

Collect unlabeled cells (Ly-6G-cell fraction) using LS Column or autoMACS Pro Separator

Centrifuge cell suspension at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Aspirate supernatant completely and resuspend cell pellet in 400 μL of buffer

Add 100 μL of Anti-Gr-1-Biotin, mix well, and incubate for 10 min on ice

Wash cells using 5 mL of buffer and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Aspirate supernatant completely and resuspend cell pellet in 900 μL of buffer

Add 100 μL of Streptavidin MicroBeads, mix well, and incubate for 15 min on ice (see Note 5)

Wash cells using 10–20 mL of buffer and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Aspirate supernatant completely and resuspend cell pellet in 500 μL of buffer

Collect magnetically labeled cells (Gr-1dimLy-6G-cell fraction) using LS Column or autoMACS Pro Separator

3.2. Identification of M-MDSCs by T cell proliferation assay (see Note 6)

Euthanize the mouse and aseptically remove the spleen to obtain splenocytes

Place the spleen on a 70 μm mesh filter (Corning) and mince under 3 mL of RPMI culture medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and remove the filter and the remaining spleen tissue

Put the culture medium that has passes through the filter into 15 mL centrifuge tube, wash with 2 mL of fresh culture solution, and put it in the 15 mL centrifuge tube

Centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C and discard supernatant

Resuspend the cell pellet with 2 mL of ACK lysis buffer to remove red blood cells, place on ice for 5 min

Add 3 mL of RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Aspirate supernatant completely and resuspend cell pellet in 100 μL of buffer per 107 cells

Add 10 μL of CD3-Biotin (Miltenyi Biotec) per 107 cells, mix well, and incubate on ice for 10 min

Wash cells with 2 mL of buffer and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Aspirate supernatant completely and resuspend cell pellet in 80 μL of buffer per 107 cells

Add 20 μL of Anti-Biotin MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) per 107 cells, mix well, and incubate on ice for 15 min

Wash cells with 2 mL of buffer and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Aspirate supernatant completely and resuspend cell pellet in 500 μL of buffer

Separate CD3+ T cells using LD Columns or autoMACS Separator

Centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Aspirate supernatant completely and resuspend cell pellet in 999 μL of PBS

Add 1 μL of CellTrace stock solution in DMSO to label the CD3+ T cells with CellTrace Violet (CTV) (see Note 7 and 8)

Incubate the cell in a 37 °C water bath for 20 min

Add 20 mL of culture media and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C to remove any remaining unbound dye

- Perform in 96-well U-bottom assay plates (Corning) and include the following groups (Table 1) (see Note 9)

- Unstained control group; only responder T cells not stained with CTV are included

- Unstimulated control group; only CTV-stained responder T cells were included

- Stimulated group; CTV-stained responder T cells stimulated with Anti-CD3/28 Ab

- Stimulated group with M-MDSC (responder T cells: M-MDSCs ratio =2:1)

- Stimulated group with M-MDSC (responder T cells: M-MDSCs ratio = 1:1)

- Stimulated group with M-MDSC (responder T cells: M-MDSCs ratio = 1:2)

Incubate the plate in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator for 3 days

Centrifuge the plate at 1200 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C and remove the supernatant

Add 200 μL of buffer to each well, resuspend the cell by pipetting

Transfer the resuspended cells to a FACS tube

Centrifuge the plate at 1200 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C and remove the supernatant

Add 50 μL of FcR Blocking Reagent cocktail (1 μL FcR blocking Reagent, 49 μL staining buffer), mix well, and incubate for 10 min on ice

Add anti-CD3 antibody conjugated with APC (Miltenyi Biotec), anti-CD4 antibody conjugated with PE-Cy7 (eBioscience), anti-CD8 antibody conjugated with APC-Vio770 (Miltenyi Biotec), mix well, and incubate for 30 min on ice

Wash cells using 5 mL of buffer and centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C

Read on the flow cytometer and analyze with FlowJo software (Fig. 2)

Table 1.

T cell proliferation assay setup guide-components included in wells for each group.

| Responder T cells (1 × 106 cell/mL) | M-MDSCs (2 × 106 cells/mL) | Responder T cell: M-MDSC ratio | Anti-CD3/CD28 Ab | α-MEM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 100 μL (unstained control) | – | 1:0 | 150 μL | |

| B | 100 μL (unstı`mulated control) | – | 1:0 | 150 μL | |

| C | 100 μL | – | 1:0 | 30 μL | 120 μL |

| D | 100 μL | 25 μL | 2:1 | 30 μL | 95 μL |

| E | 100 μL | 50 μL | 1:1 | 30 μL | 70 μL |

| F | 100 μL | 100 μL | 1:2 | 30 μL | 20 μL |

FIG. 2:

T cell proliferation assay. (A) Analysis of CellTrace Violet stained CD4+ T cell inhibition assay according to M-MDSCs. (B) Analysis of CellTrace Violet stained CD8+ T cell inhibition assay according to M-MDSCs.

3.3. Differentiation of M-MDSCs into osteoclasts

Seed the isolated M-MDSCs in a 48-well plate (2.5 × 105 cells/well, Corning) in the presence of monocyte colony-stimulating factor (25 ng/mL, R&D Systems) in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (see Note 10)

Plates are incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 4 days

After 4 days, the culture medium containing M-CSF and RANKL (50 ng/mL, R&D Systems) is replaced to differentiate into osteoclasts

After adding the culture medium containing M-CSF and RANKL, large, multinucleated osteoclasts begin to appear 2 days after and become abundant within 6 days

3.4. Assessment of osteoclastogenesis of M-MSDCs

3.4.1. TRAP staining

On the 4th day (if separated by FACS)/6th day (if separated by isolation kit) after adding the differentiation culture medium, aspirate the medium in the 48-well plate (Corning, see Note 11 and 12)

Wash the wells with PBS buffer solution for three times

Add fixative (1% paraformaldehyde, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for fixing cells to each well at room temperature for 5–15 min

Aspirate the fixative and wash the wells with PBS buffer solution for three times

Prepare TRAP staining solution (pH 5.0)

Mix 5 mL of 0.1 M Acetate buffer, 1 mL of 0.3 M Sodium tartrate, 3.89 mL of D.D·W, 10 μL of Triton X-100, and 1 mg of Naphthol AS-MX phosphate

Incubate at 37 °C water bath for 20 min

Add 3 mg of Fast Red Violet LB salt

Add 200 μL/well of TRAP staining solution to the fixed cells

Incubate at 37 °C for 10 min (see Note 13)

Remove the TRAP staining solution and wash the well with PBS buffer solution for three times

Add 200 μL of 15% Ehrlich’s hematoxylin and incubate at room temperature for 2 min

Wash the wells with PBS buffer solution and add 70% ethanol

Invert the wells to dry and observe under a light microscope (Fig. 3A) (see Note 14)

FIG. 3:

In vitro osteoclastogenesis assessment. (A) TRAP staining of M-MDSCs isolated using isolation kit cultured in culture medium containing M-CSF only (left) and containing M-CSF and RANKL (mid). TRAP staining of M-MDSCs isolated using FACS cultured in containing M-CSF and RANKL (right). (B) Pit assay for isolated M-MDSCs cultured in culture medium containing M-CSF and RANKL; resorbed areas are shown in white.

3.4.2. In vitro bone resorption or “pit” assay

Prepare the isolated M-MDSC as a single cell suspension in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin

Seed the cells in a 24-well plate (2.5 × 105 cells/well, Corning) to begin the differentiation process (see Note 15)

Plates are incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in the presence of M-CSF (25 ng/mL) for 4 days

After 4 days, the culture medium containing M-CSF and RANKL (50 ng/mL) is replaced to differentiate into osteoclasts

Plates are incubated in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C for additional 7–9 days with medium change every 2 days

After a total of 11–13 days of incubation, aspirate the medium and add 10% bleach solution to analyze the surface for pit formation

Incubate the plate at room temperature for 5 min and aspirate the bleach solution

Wash twice with distilled water and dry at room temperature for 3–5h

Observe under microscope at 100× magnification (Fig. 3B) (see Note 16)

5. Concluding remarks

M-MDSCs can act as precursors of osteoclasts in the inflammatory environment as well as in the tumor microenvironment. It has been found that M-MDSCs are differentiated into osteoclasts and are involved in bone destruction in osteoarthritis and periodontitis (Kirkwood et al., 2018; Kwack et al., 2021, 2022; Zhang et al., 2015, 2021), and there is a possibility that M-MDSCs are involved in bone-related diseases that have not yet been identified. Studying M-MDSCs as novel osteoclast progenitors and evaluating osteoclast ability will serve as a platform for testing novel therapeutic approaches targeting M-MDSCs in bone-destroying diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants, R01DE028258 and R01DE032310 (to K.L.K.), and by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, NRF-2021R1A6A3A03044546 (to K.H.K.).

Footnotes

Catalog number and suppliers are provided as reference, but equivalent products can be purchased from various suppliers and used for experimentation

The gold standard for cell separation is the method using Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS). FACS has the advantage of being able to process millions of cells and isolate highly purified subpopulations. However, it requires expensive machinery and has the disadvantage of being relatively time consuming. Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS) is also used to isolate specific cell populations using surface markers, but it requires less equipment and takes less time than FACS. However, it lacks sensitivity and is not easily compatible with multiple marker profile compared to FACS (Sutermaster & Darling, 2019).

Refer to your institution’s specific regulations for protocols regarding animal experiment. All animal experiments in this paper were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University at Buffalo and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals

If bone marrow cells do not flow out easily, there is another method using a centrifuge. After cutting both end of the bone, place it in a 0.5 mL microfuge tube with a hole in the bottom, and place this tube in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 10 min. Resuspend the cell pellet in 5 mL of RPMI 1640 culture medium

All antibodies and Microbeads except buffer are provided in the isolation kit

Remember that it is difficult to define MDSCs based on phenotype alone, so evaluation of T cell inhibitory functions is essential

CellTrace stock solution and DMSO are included in the CTV cell proliferation kit. Fresh vial of CTV should be used for each experiment

Since a non-staining control is required, stain the cells except for the non-staining control

Each group should be assayed at least in triplicate

If you want to compare M-MDSCs from groups with different conditions, you typically need 3–4 replicates for the same group

The time to differentiate into osteoclasts may vary depending on the origin of the isolated cells, so careful observation is required to find an appropriate time. Even if the cells have the same origin, they may differ depending on the cell separation method. In the case of M-MDSCs, a total of 8 days when isolated by FACS and a total of 10 days when isolated by an isolation kit were appropriate.

Since the PMN-MDSC (CD11b+Ly6ClowLy6G+) population does not differentiate into osteoclast (data not shown), even if some mixed populations exist during the M-MDSC isolation process, the experimental results are not significantly affected.

The staining time to obtain adequate TRAP staining is usually between 10 and 60 min, but more than 60 min may be required. To avoid overstaining, carefully monitor the degree of staining with the staining time

Mature osteoclasts were analyzed using Image J program, and were determined to be TRAP-positive cells with 3 or more nuclei and a diameter of 50 μm or more

The 24 well Corning Osteo Assay Plate is no longer in production. It can be replaced with a 96 well Corning Osteo Assay Plate (#3988) or other company products

The pit area can be quantified using the Image J program

Disclosures

K.H.K., L.Z., and K.L.K. have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Almand B, Clark JI, Nikitina E, van Beynen J, English NR, Knight SC, et al. (2001). Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: A mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. Journal of Immunology, 166(1), 678–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins GJ, Bouralexis S, Haynes DR, Graves SE, Geary SM, Evdokiou A, et al. (2001). Osteoprotegerin inhibits osteoclast formation and bone resorbing activity in giant cell tumors of bone. Bone, 28(4), 370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce BF, Rosenberg E, de Papp AE, & Duong LT (2012). The osteoclast, bone remodelling and treatment of metabolic bone disease. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 42(12), 1332–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte V, Brandau S, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Frey AB, Greten TF, et al. (2016). Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nature Communications, 7, 12150. 10.1038/ncomms12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers TJ (2000). Regulation of the differentiation and function of osteoclasts. The Journal of Pathology, 192(1), 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilin S, Merkel AR, Johnson JR, Johnson RW, Edwards JR, & Sterling JA (2012). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells expand during breast cancer progression and promote tumor-induced bone destruction. Oncoimmunology, 1(9), 1484–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcetti L, Peranzoni E, Ugel S, Marigo I, Gomez AF, Mesa C, et al. (2010). Hierarchy of immunosuppressive strength among myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets is determined by GM-CSF. European Journal of Immunology, 40(1), 22–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgington-Mitchell LE, Rautela J, Duivenvoorden HM, Jayatilleke KM, van der Linden WA, Verdoes M, et al. (2015). Cysteine cathepsin activity suppresses osteoclastogenesis of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in breast cancer. Oncotarget, 6(29), 27008–27022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich DI, & Nagaraj S (2009). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology, 9(3), 162–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood KL, Zhang LX, Thiyagarajan R, Seldeen KL, & Troen BR (2018). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells at the intersection of inflammaging and bone fragility. Immunological Investigations, 47(8), 844–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwack KH, Maglaras V, Thiyagarajan R, Zhang LX, & Kirkwood KL (2021). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in obesity-associated periodontal disease: A conceptual model. Periodontology 2000, 87(1), 268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwack KH, Zhang L, Sohn J, Maglaras V, Thiyagarajan R, & Kirkwood KL (2022). Novel Preosteoclast populations in obesity-associated periodontal disease. Journal of Dental Research, 101(3), 348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino S, Logan JG, Mellis D, & Capulli M (2014). Generation and culture of osteoclasts. Bonekey Reports, 3, 570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSheehy PM, & Chambers TJ (1986). Osteoblastic cells mediate osteoclastic responsiveness to parathyroid hormone. Endocrinology, 118(2), 824–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima T, & Takayanagi H (2009). Osteoclasts and the immune system. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism, 27(5), 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ost M, Singh A, Peschel A, Mehling R, Rieber N, & Hartl D (2016). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in bacterial infections. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 6, 37. 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawant A, Deshane J, Jules J, Lee CM, Harris BA, Feng X, et al. (2013). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells function as novel osteoclast progenitors enhancing bone loss in breast cancer. Cancer Research, 73(2), 672–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutermaster BA, & Darling EM (2019). Considerations for high-yield, high-throughput cell enrichment: Fluorescence versus magnetic sorting. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum SL (2000). Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science, 289(5484), 1504–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Akatsu T, Tanaka H, Sasaki T, Nishihara T, et al. (1990). Origin of osteoclasts: Mature monocytes and macrophages are capable of differentiating into osteoclasts under a suitable microenvironment prepared by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 87(18), 7260–7264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugel S, Peranzoni E, Desantis G, Chioda M, Walter S, Weinschenk T, et al. (2012). Immune tolerance to tumor antigens occurs in a specialized environment of the spleen. Cell Reports, 2(3), 628–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaananen HK, Zhao H, Mulari M, & Halleen JM (2000). The cell biology of osteoclast function. Journal of Cell Science, 113(Pt. 3), 377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschoor CP, Johnstone J, Millar J, Dorrington MG, Habibagahi M, Lelic A, et al. (2013). Blood CD33(+)HLA-DR(−) myeloid-derived suppressor cells are increased with age and a history of cancer. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 93(4), 633–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Huang YF, Wang S, Fu R, Guo CH, Wang HY, et al. (2015). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells contribute to bone erosion in collagen-induced arthritis by differentiating to osteoclasts. Journal of Autoimmunity, 65, 82–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LX, Kirkwood CL, Sohn J, Lau A, Bayers-Thering M, Bali SK, et al. (2021). Expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells contributes to metabolic osteoarthritis through subchondral bone remodeling. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 23(1), 287. 10.1186/s13075-021-02663-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang J, Zhang J, Lwin ST, Edwards JR, Edwards CM, Mundy GR, et al. (2012). Osteoclasts in multiple myeloma are derived from Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells. PLoS One, 7(11), e48871. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]