Significance

Low socioeconomic status (SES) is a risk factor for poor health outcomes in a wide variety of health contexts, including hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) in cancer, where immune-reconstituting cells are transferred from a healthy donor to a cancer patient recipient. We now find that the cell donor’s SES affects the HCT recipient’s health outcomes. This implies that SES-related health disparities are “transplantable” through the transfer of hematopoietic stem cells and can persist even when those cells engraft in a new host. This highlights the critical need for public health interventions targeting those living in socioeconomically disadvantaged environments as a means for preventing health disparities.

Keywords: socioeconomic status, health outcomes, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, social determinants of health, disparities

Abstract

Low socioeconomic status (SES) is a risk factor for mortality and immune dysfunction across a wide range of diseases, including cancer. However, cancer is distinct in the use of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) as a treatment for hematologic malignancies to transfer healthy hematopoietic cells from one person to another. This raises the question of whether social disadvantage of an HCT cell donor, as assessed by low SES, might impact the subsequent health outcomes of the HCT recipient. To evaluate the cellular transplantability of SES-associated health risk, we analyzed the health outcomes of 2,005 HCT recipients who were transplanted for hematologic malignancy at 125 United States transplant centers and tested whether their outcomes differed as a function of their cell donor’s SES (controlling for other known HCT-related risk factors). Recipients transplanted with cells from donors in the lowest quartile of SES experienced a 9.7% reduction in overall survival (P = 0.001) and 6.6% increase in treatment-related mortality within 3 y (P = 0.008) compared to those transplanted from donors in the highest SES quartile. These results are consistent with previous research linking socioeconomic disadvantage to altered immune cell function and hematopoiesis, and they reveal an unanticipated persistence of those effects after cells are transferred into a new host environment. These SES-related disparities in health outcomes underscore the need to map the biological mechanisms involved in the social determinants of health and develop interventions to block those effects and enhance the health of both HCT donors and recipients.

Social disadvantage, as indicated by low socioeconomic status (SES), is associated with poorer disease outcomes in a wide variety of diseases (1), including cancer (2). Multiple mechanisms contribute to these effects, including variations in environmental toxin and microbial exposures, health care access and quality, health literacy, and health-related behaviors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and diet. Low SES is also associated with elevated biological stress responses in the sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis that can compromise multiple physiological systems throughout the body, including the immune system (3, 4). However, it is difficult to disentangle the contributions of these multiple mechanisms as they are generally correlated in the human social ecology.

One way to identify the effects of specific cellular mechanisms is to examine treatment protocols in which those cells are selectively transferred into a patient for therapeutic purposes. In the context of cancer, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is often used to treat patients with high-risk or relapsed hematological malignancies. This procedure involves mobilizing white blood cell pools that are enriched for hematopoietic stem cells from a healthy blood donor and transplanting those cells into a cancer patient to reconstitute the immune system following high-intensity chemotherapy. Allogeneic HCT can successfully restore immune function in many cancer patients, but this procedure also carries significant risks for morbidity and mortality, which are not proportionally shared across patients. Among cancer patients receiving HCTs, those living in low SES environments experience increased mortality following HCT (5, 6). This disparity is not fully explained by race (5), insurance status (7), or access to care (8), and some research suggests that sympathetic nervous system–mediated alterations in hematopoietic cell function, gene regulation, and immune system biology may contribute to these differential outcomes (3, 9–12). In existing observational studies, however, it is difficult to distinguish the effects of SES-associated neuroimmune interactions from other SES-associated factors that also affect the patient (e.g., healthcare, behavior, environmental exposures, etc.).

One way to assess the specific contribution of SES-related alterations in immune cell function would be to examine how the SES of a hematopoietic cell donor affects the health outcomes of an HCT recipient. The HCT matching system largely disassociates the SES of the cell donor with the SES of the cell recipient, leaving the transferred hematopoietic cell pool as the only common feature. To the extent that the SES of an HCT donor affects the treatment outcomes of an HCT recipient, the mechanism of that transmitted risk can only involve the transplanted cell pool. The present analyses thus examined whether the SES of an HCT cell donor might affect the treatment outcomes of an HCT recipient (over and above the recipient’s SES and other known clinical or demographic determinants of recipient outcomes) and assessed whether SES-associated health risk was transferrable through the transplanted hematopoietic cell pool.

Results

We identified 2,005 donor–recipient pairs from 125 transplant centers in the United States through their enrollment in the Center for International Bone Marrow Treatment and Research (CIBMTR) who met the selection criteria in Fig. 1. Median recipient age at transplantation was 51 y (range 1 to 77 y), 92% were White, and 44% were female. Acute myelogenous leukemia (55%) was the most common diagnosis, followed by myelodysplastic syndrome (22%). Median donor age at the time of donation was 34 y (range 18 to 62 y), 84% of donors were White, and 44% were female. Median posttransplant follow-up was 120 mo (range 4 to 219 mo; Table 1). SI Appendix, Table S1 cross-classifies transplant characteristics by donor and recipient SES quartiles and includes additional transplant characteristics. Donor CMV status and recipient HCT comorbidity index (HCT-CI), both of which have been associated with HCT outcomes (13, 14), differed across both donor and recipient SES quartiles. Primary analyses utilizing a continuous (standardized) SES disadvantage composite score ranged from −2.6 to 3.9 for donors and −3.3 to 4.4 for recipients. Higher (positive) composite scores were indicative of lower SES or greater socioeconomic disadvantage. Donor and recipient SES composite scores were weakly positively correlated (r = 0.09, P < 0.001) and neither donor (r = 0.03, P = 0.182) nor recipient (r = 0.02, P = 0.335) SES composite scores were significantly correlated with CD34+ cell dose, which is an indicator of hematopoietic cell concentration within the transferred cell pool and has been associated with HCT outcomes (15).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram. Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CML, cytomegalovirus; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; NMDP, National Marrow Donor Program.

Table 1.

Hematopoietic cell transplantation recipient and donor characteristics

| Characteristic | Recipient (%) | Donor (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 2,005 | 2,005 |

| No. of centers | 125 | NA |

| Age—no. (%) | ||

| Median age (min-max) | 51 (1 to 77) | 34 (18 to 62) |

| <18 | 56 (3) | 0 |

| 18 to 39 | 539 (27) | 1,396 (70) |

| 40 to 49 | 377 (19) | 447 (22) |

| 50+ | 1,033 (52) | 162 (8) |

| Donor–recipient sex match—no. (%) | ||

| Male–Male | 762 (38) | |

| Female–Male | 352 (18) | |

| Male–Female | 527 (26) | |

| Female–Female | 364 (18) | |

| Race/Ethnicity—no. (%) | ||

| White | 1,837 (92) | 1,688 (84) |

| Non-White | 127 (6) | 291 (15) |

| Unknown | 41 (2) | 26 (1) |

| Donor–recipient cytomegalovirus status—no. (%) | ||

| +/+ | 381 (19) | |

| −/+ | 710 (35) | |

| +/− | 183 (9) | |

| −/− | 520 (26) | |

| Unknown | 211 (11) | |

| Karnofsky/lansky performance score—no. (%) | ||

| 90 to 100 | 1,214 (61) | |

| <90 | 694 (35) | |

| Unknown | 97 (5) | |

| HCT-CI score—no. (%) | ||

| 0 to 2 | 455 (23) | |

| 3+ | 337 (17) | |

| Unknown | 1,213 (60) | |

| Disease—no. (%) | ||

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 1,095 (55) | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 330 (16) | |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 146 (7) | |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 434 (22) | |

| Year of Transplant—no. (%) | ||

| 2000 to 2007 | 1,181 (59) | |

| 2008 to 2013 | 824 (41) | |

| Follow-up in months—median (range) | 120 (4 to 219) |

Abbreviations: HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index.

Donor SES and HCT Outcomes.

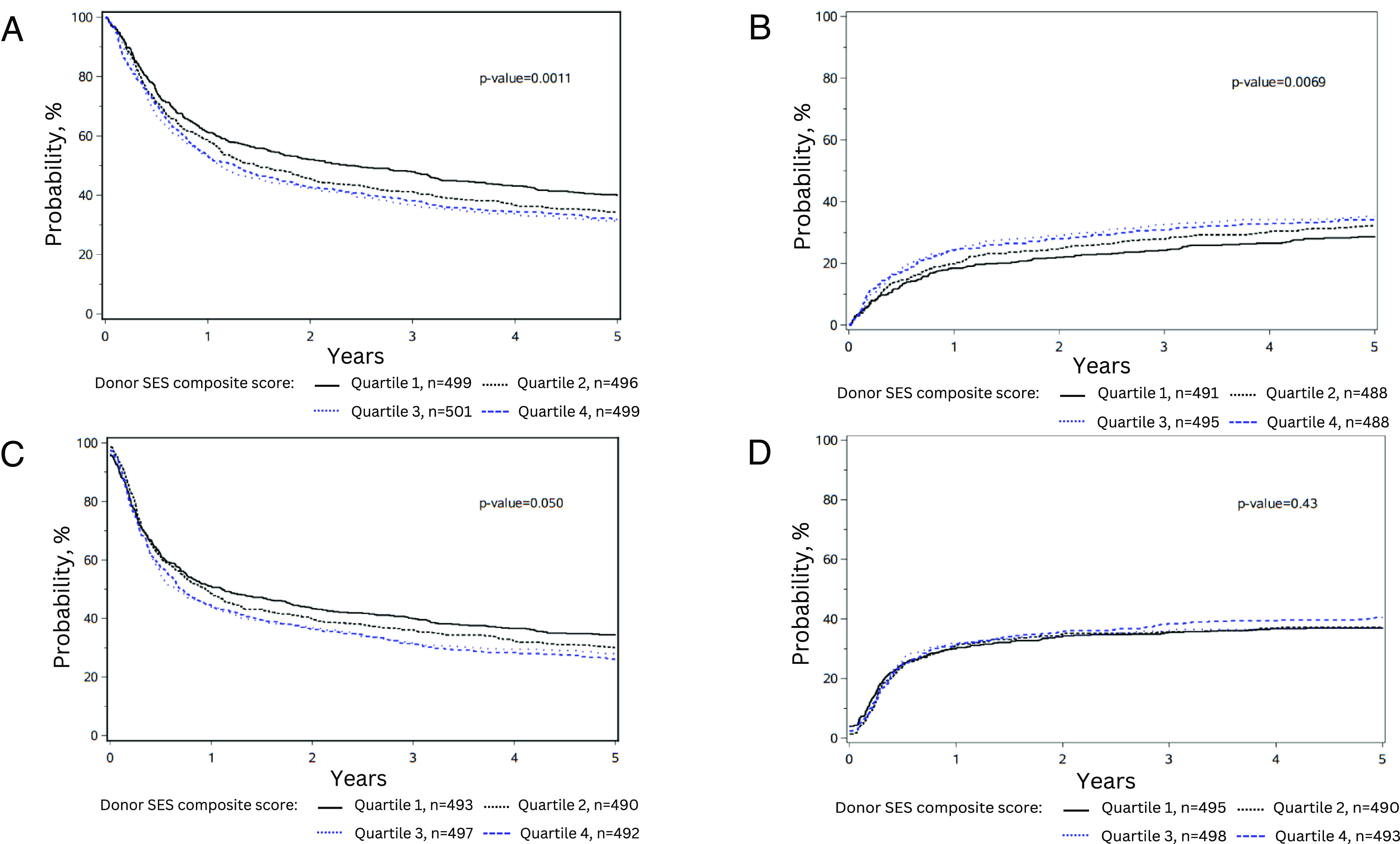

In multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models, the donor SES disadvantage score was associated with increased risk of posttransplant mortality for the recipient [Overall Survival (OS): HR 1.09 per SD from the mean SES composite score, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.14, P < 0.001]. When categorized into quartiles for interpretation, SES quartiles were also significantly associated with recipient OS (P = 0.001), such that recipients receiving transplants from donors in the two lowest SES quartiles experienced inferior survival compared to those receiving transplants from donors in the highest SES quartile (Quartile 1: HR 1.28, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.47, P < 0.001; Quartile 2: HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.41, P < 0.001; Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S2). At 3 y, OS was 38.2% among individuals receiving cells from donors in the quartile of greatest socioeconomic disadvantage, whereas it was 47.9% among those receiving cells from donors in the quartile with the highest SES, representing a 9.7% difference (P = 0.001). Donor SES composite score was also significantly associated with treatment-related mortality (TRM; continuous SES: HR 1.09 per SD from the mean SES composite, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.17, P = 0.006; quartile-split: P = 0.007). Recipients transplanted with cells from donors in the two lowest SES quartiles experienced increased risk for TRM compared to those transplanted with cells from donors in the highest SES quartile (Quartile 1: HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.71, P = 0.003; Quartile 2: HR 1.30, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.57, P = 0.008; Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Table S3). At 3 y, TRM was 30.8% among individuals receiving cells from donors in the quartile of the lowest SES and it was 24.2% among those receiving cells from donors in the quartile with the highest SES, representing a 6.6% difference (P = 0.008).

Fig. 2.

Differences in (A) Overall survival, (B) Treatment-related mortality, (C) Disease-free survival, and (D) relapse stratified by donor SES quartiles. All plots adjusted for relevant clinical and demographic variables shown in Table 1 and SI Appendix, Table S1.

Donor SES was significantly associated with recipient disease-free survival (DFS; continuous SES, HR 1.07 per SD from the mean SES composite score, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.12, P = 0.012; quartile-split: P = 0.05), and individuals receiving stem cells from donors in the lowest SES quartile showed inferior DFS compared to donors from the highest SES quartile (HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.35, P = 0.014, Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Table S4). Models for OS, TRM, and DFS were minimally changed when stratified for HCT-CI and adjusted for the proportion of donors living in rural settings (SI Appendix, Tables S2–S4). Donor SES composite score was not significantly associated with cancer relapse (Fig. 2D), acute graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD), or chronic GVHD (SI Appendix, Tables S5–S7). In this sample, the recipient’s SES composite score was not significantly associated with any of the clinical outcomes analyzed (SI Appendix, Supplemental Figure).

Discussion

These results show that SES-associated health risk can be transferred from one individual to another through the process of HCT, highlighting the key role of immune cell biology in mediating SES-related health disparities in the context of cancer. These findings provide a pathway for investigation into the cellular mechanisms of SES-associated health risks. These findings also support the need for further public policy and clinical interventions to mitigate the impact of social disadvantage on immune system function and health outcomes for HCT recipients and donors, as well as others whose immune system function and health may be compromised by the cellular impacts of low SES.

Here, lower SES among HCT donors was associated with significantly worse OS as well as increased TRM among transplant recipients. These effects were independent of recipient demographic, disease, and treatment characteristics, as well as recipient SES. These findings from the CIBMTR, the largest global repository of donor/recipient HCT data, not only confirm the notion that the biological impact of socioeconomic adversity penetrates molecular and cellular functioning (3, 8, 10, 11), but that it is transferrable, with an influence sufficiently durable and robust to affect critical long-term health outcomes. It is possible that this occurs at the level of the hematopoietic stem cell, as previous research has demonstrated stress-related alterations in stem cell function that affect hematopoiesis, promote myeloid differentiation, and enhance inflammatory biology (4, 16). This prior research aligns with our findings of increased TRM, which typically occurs concurrently with myeloid recovery after transplant. We found no association between donor SES and relapse or GVHD, suggesting that the significant outcomes herein are not lymphocyte driven (17–21). Future research is required to identify the biological mechanisms of transferred SES-related risk in the context of HCT to define intervention strategies aimed at abrogating those risks and ensuring health equity for all HCT donors and recipients.

SES and other social determinants affect health outcomes through activation of multiple biological pathways (22), including early-life SES-related biological insults that affect later-life health outcomes (3). The present data suggest that such effects can not only persist throughout the lifespan but be transplanted into a new host. Although the biological mechanisms of these effects remain to be determined, previous research on recipients’ pretransplant blood samples has found that SES- and stress-associated myeloid- and inflammation-related transcriptome signatures can predict HCT-related clinical outcomes (9, 10). Moreover, the hematopoietic stem cell niche receives neurological input (23), suggesting the potential for pharmacological interventions to disrupt the neurobiological pathways through which SES exerts detrimental effects on hematopoietic or stem cell function (e.g., using beta-adrenergic antagonists) (24). These implications extend beyond HCT recipients and could benefit any individuals living in poverty or experiencing conditions of social disadvantage. Recognizing SES as a biological predictor, akin to clinical vital signs, could open opportunities for earlier interventions aimed at improving health outcomes and reducing health disparities.

The current data did not show a significant association between recipient SES and HCT outcomes, in contrast to previously published work (5, 6). This difference may be due to a combination of factors in the current study including use of a more comprehensive SES measure and a smaller recipient sample size. As such, the current data may indicate a stronger clinical influence of donor SES as compared to that of the recipient. These donor SES-related effects are similar in scale to practice-changing findings, including the heightened risk of nonrelapse mortality observed in haploidentical transplantation when compared to matched-sibling HCT (25), as well as the elevated overall mortality linked to peripheral blood vs. bone marrow as a stem cell source in pediatric acute leukemia transplants (26).

These results are subject to several limitations. Assessment of causality is limited by the retrospective and cross-sectional nature of the current cohort. These results require further validation in more diverse and contemporary patient cohorts. The present study cohort lacks racial diversity, which is a known limitation of the HCT donor registry; however, initiatives are underway to enhance racial diversity in the donor pool. Data on donor health comorbidities were unavailable, which may correlate with SES; however, donors undergo extensive health screening prior to donation to ensure fitness to donate and minimize risk to the recipient. Despite our compelling findings, the use of ZIP code as the geographically based SES indicator may reduce the overall resolution of the data. However, these findings are consistent with work from Diez-Roux et al. noting that an individual’s specific geographic location may not be as impactful as the ecosystem they live within (27, 28), such that ZIP code may be a more potent social determinant of health than more specific geospatial data. Further validation using different geography levels, alternate measures of SES, or even consideration of environmental exposures will be important. Our findings may also raise concerns that certain donors will be considered less favorable based on their socioeconomic disadvantage; however, there is no benefit to serving as a HCT donor—it is an altruistic act, which may be associated with pain or missed workdays. The overarching goal of HCT is to cure disease; it is important to protect individuals who are socioeconomically disadvantaged from donating if they are not the optimal donor and to select the best available donor for recipients to increase their likelihood of survival.

Despite these limitations, the present data suggest that the biological impact of social disadvantage may alter hematopoietic cell function in ways that persist following transplantation into a new host. These results show a deep cellular penetrance of socioeconomic adversity and underscore the need for additional interventions to mitigate social health disparities. As further research defines the specific molecular mechanisms underlying these cell-transplantable health disparities, new pharmacologic interventions may also be deployed to mitigate the immunobiological health risks associated with low SES for cancer patients, HCT donors, and all who bear the health burdens of socioeconomic disadvantage.

Methods

Population.

All patients enrolled in the CIBMTR with acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome that underwent their first allogeneic 8/8 HLA-matched unrelated peripheral blood stem cell HCT between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2013, were eligible for inclusion in the study. HCT recipients were required to have accompanying donor demographic data available, and both recipients and donors were required to have documented residence in the United States (US) at the time of hematopoietic cell donation or transplantation, with a documented ZIP code available for geocoding and characterization of neighborhood SES. Donor and recipient race and ethnicity were self-identified. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. All donors and recipients included in this analysis provided informed consent permitting the use of their data for research. The study protocol was approved by the National Marrow Donor Program Institutional Review Board. Protected Health Information used in the performance of such research is collected and maintained in CIBMTR’s capacity as a Public Health Authority under the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

Geocoding and Census Population Data Assignment.

Donor and recipient residential addresses were geocoded in ArcGIS and assigned to 2000 or 2010 ZIP Code Tabulation Areas (ZCTA) based on the year of donation (donor) or transplant (recipient). Given the length of the study period (2000 to 2013), various census data products, including 2000 decennial census and American Community Survey (ACS) 5-y estimates, were used to best align with donation/transplant years. Individuals with a donation or transplant year of 2007 onward were assigned to 2010 ZCTAs and ACS 5-y data; earlier years were assigned to 2000 ZCTAs and 2000 decennial population data. The study population was further classified based on population density (rural vs. urban). Geographic codes and population data assignments were used to construct neighborhood-level SES variables for HCT donors and recipients. Neighborhood-level data were obtained from census tables downloaded from the IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System (29) and used to abstract SES measures of household income (Consumer Price Index-adjusted median household income), poverty (percent of families whose income in the past 12 mo is below the poverty level), education (percent of the population ≥25 y of age without high school education), housing (percent of occupied housing units that are renter-occupied), and employment (percent of unemployed civilians ≥16 y of age in the labor force) for donors and recipients (Table 2). These measures were selected based on an understanding of the core components of SES (income, education, and employment) (30) and a recognition of the growing importance of housing as a social determinant of health, while seeking a parsimonious set of neighborhood factors to enhance interpretation and clinical relevance. These five measures are strongly correlated. No single measure of SES is a complete representation of an individual’s status; thus, to address the multidimensionality of this construct, using methods previously described (31), a SES composite score was computed using principal component analysis. The first leading principal component was very close to the equally weighted average of the five standardized SES variables. For ease of interpretation, the equally weighted average of the five components, with each having a mean of 0 and a SD of 1, was adopted as the SES composite score. Separate SES composite scores were defined for donors and recipients, respectively. A higher standardized SES composite score is indicative of greater socioeconomic disadvantage.

Table 2.

Socioeconomic variables included in SES composite score

| (-) CPI-adjusted median household income (in 2015 inflation-adjusted dollars) |

| Percent of families whose income in the past 12 mo is below poverty level |

| Percent of population 25 y and over without high school education |

| Percent of occupied housing units that are renter-occupied |

| Percent of unemployed civilian 16 y and over in labor force |

Abbreviations: CPI, consumer price index; SES, socioeconomic status; ZCTA, ZIP code tabulation area.

All variables coded for donor and recipient based on the ZIP code tabulation (ZCTA) geographic area. Median household income sign-inverted to align with directionality of other variables.

Outcomes.

HCT recipient clinical outcomes were examined, including OS, DFS, relapse, TRM, grade 2 to 4 and grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD, and chronic GVHD. Additional clinical variables for use as covariates included recipient and donor age, sex, race, sex match, race match, recipient SES composite score, and CMV serostatus; recipient hematologic malignancy diagnosis, Karnofsky Performance Status, HCT Comorbidity Index score (32), disease status at the time of transplant, interval from diagnosis to HCT, transplant conditioning intensity (myeloablative, reduced intensity, or nonmyeloablative), use of total body irradiation in conditioning, year of HCT, transplant center, infused CD34+ cell dose, use of antithymocyte globulin or alemtuzumab, and GVHD prophylaxis.

Statistical Analysis.

Survival analyses were performed to assess the association between the standardized donor SES composite score (a continuous score that was also categorized into quartiles for interpretation) and recipient clinical outcomes, including OS, DFS, relapse, TRM, acute and chronic GVHD. Disease progression, recurrence, or death from any cause were considered as DFS events. Cox proportional hazards models (33) were used to adjust for relevant patient-, disease-, and transplantation-related covariates as listed in Table 1. The proportional hazards assumption for Cox models was tested by adding a time-dependent covariate for each risk factor and each outcome. Covariates violating the proportional hazards assumption were adjusted via stratification in the Cox regression models. A backward stepwise variable selection procedure was performed to identify adjusted covariates with a P < 0.05 for retention in each model. Donor–recipient race match and recipient SES composite score were adjusted by forcing them into all the models. Interactions between the donor SES and adjusted covariates were examined and no significant interactions were detected. The center effect was adjusted as clusters using a GEE approach for all the endpoints. Relative risks were expressed as hazard ratios. The adjusted cumulative incidences for TRM (or relapse) were estimated by treating relapse (or TRM) as competing risks. Patients with missing information for a particular endpoint or an adjusted covariate in the model were excluded from the model. To adjust for multiple testing, the significance level for pairwise comparison of donor SES was P < 0.05/6 = 0.0083. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the National Cancer Institute of the NIH (R01 CA23856).

Author contributions

L.M.T., K.M.B., S.W.C., S.R.S., M.R.V., J.D.R., and J.M.K. designed research; L.M.T., K.M.B., S.W.C., S.R.S., M.R.V., J.D.R., and J.M.K. performed research; T.W., S.W.C., M.A.-J., E.W., and Y.Z. analyzed data; L.M.T. and J.M.K. obtained funding; and L.M.T., S.W.C., and J.M.K. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The CIBMTR supports accessibility of research in accord with the NIH’s Data Sharing Policy and the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Moonshot Public Access and Data Sharing Policy. Upon acceptance for publication, this dataset will be posted to the CIBMTR Publicly Available data repository found at: https://cibmtr.org/CIBMTR/Resources/Publicly-Available-Datasets# (34).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Dubay L. C., Lebrun L. A., Health, behavior, and health care disparities: Disentangling the effects of income and race in the United States. Int. J. Health Serv. 42, 607–625 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hastert T. A., Beresford S. A., Sheppard L., White E., Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality by area-level socioeconomic status: A multilevel analysis. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 69, 168–176 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller G. E., et al. , Low early-life social class leaves a biological residue manifested by decreased glucocorticoid and increased proinflammatory signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14716–14721 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell N. D., et al. , Social stress up-regulates inflammatory gene expression in the leukocyte transcriptome via beta-adrenergic induction of myelopoiesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 16574–16579 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker K. S., et al. , Race and socioeconomic status influence outcomes of unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 15, 1543–1554 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silla L., et al. , Patient socioeconomic status as a prognostic factor for allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transpl. 43, 571–577 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holm L. V., et al. , Social inequality in cancer rehabilitation: A population-based cohort study. Acta Oncol. 52, 410–422 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu D. I., et al. , Effect of race and socioeconomic status on surgical margins and biochemical outcomes in an equal-access health care setting: Results from the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital (SEARCH) database. Cancer 118, 4999–5007 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight J. M., et al. , Molecular correlates of socioeconomic status and clinical outcomes following hematopoietic cell transplantation for leukemia. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 3, pkz073 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight J. M., et al. , Low socioeconomic status, adverse gene expression profiles, and clinical outcomes in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 22, 69–78 (2015), 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-15-1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen E., et al. , Genome-wide transcriptional profiling linked to social class in asthma. Thorax 64, 38–43 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acabchuk R. L., Kamath J., Salamone J. D., Johnson B. T., Stress and chronic illness: The inflammatory pathway. Soc. Sci. Med. 185, 166–170 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorror M. L., et al. , Hematopoietic cell transplantation specific comorbidity index as an outcome predictor for patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first remission: Combined FHCRC and MDACC experiences. Blood 110, 4606–4613 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ljungman P., et al. , Donor cytomegalovirus status influences the outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplant: A study by the European group for blood and marrow transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 59, 473–481 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gauntner T. D., et al. , Association of CD34 cell dose with 5-year overall survival after peripheral blood allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults with hematologic malignancies. Transplant. Cell Ther. 28, 88–95 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKim D. B., et al. , Social stress mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells to establish persistent splenic myelopoiesis. Cell Rep. 25, 2552–2562.e2553 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L., Chu J., Yu J., Wei W., Cellular and molecular mechanisms in graft-versus-host disease. J. Leukocyte Biol. 99, 279–287 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swann J. B., Smyth M. J., Immune surveillance of tumors. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1137–1146 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Koning C., et al. , CD4+ T-cell reconstitution predicts survival outcomes after acute graft-versus-host-disease: A dual-center validation. Blood 137, 848–855 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Roessel I., et al. , Early CD4+ T cell reconstitution as predictor of outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cytotherapy 22, 503–510 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Admiraal R., et al. , Association between anti-thymocyte globulin exposure and CD4+ immune reconstitution in paediatric haemopoietic cell transplantation: A multicentre, retrospective pharmacodynamic cohort analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2, e194-203 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crimmins E. M., Seeman T. E., Integrating biology into the study of health disparities. Popul. Dev. Rev. 30, 89–107 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao X., et al. , Nociceptive nerves regulate haematopoietic stem cell mobilization. Nature 589, 591–596 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight J., et al. , Propranolol inhibits stress-related gene expression profiles associated with adverse clinical outcomes in autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 24, S253–S254 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meybodi M. A., et al. , HLA-haploidentical vs matched-sibling hematopoietic cell transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 3, 2581–2585 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keesler D. A., et al. , Bone marrow versus peripheral blood from unrelated donors for children and adolescents with acute leukemia. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. J. Am. Soc. Blood Marrow Transpl. 24, 2487–2492 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diez Roux A. V., Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am. J. Public Health 91, 1783–1789 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofelmann D. A., Diez-Roux A. V., Antunes J. L., Peres M. A., Perceived neighborhood problems: Multilevel analysis to evaluate psychometric properties in a Southern adult Brazilian population. BMC Public Health 13, 1085 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manson S., Schroeder J., Van Riper D., Ruggles S., IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 14.0 [Database] (IPUMS, Minneapolis, MN), 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winkleby M. A., Jatulis D. E., Frank E., Fortmann S. P., Socioeconomic status and health: How education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Public Health 82, 816–820 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abraham I. E., et al. , Structural racism is a mediator of disparities in acute myeloid leukemia outcomes. Blood 139, 2212–2226 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorror M. L., et al. , Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: A new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood 106, 2912–2919 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox R. D., Regression analysis and life tables. J. R. Statist. Soc. B 34, 187–220 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turcotte L. M., Knight J. M., Dataset for paper “The health risk of social disadvantage is transplantable into a new host.” CIBMTR Publicly Available Datasets. https://cibmtr.org/CIBMTR/Resources/Publicly-Available-Datasets#. Deposited 14 June 2024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The CIBMTR supports accessibility of research in accord with the NIH’s Data Sharing Policy and the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Moonshot Public Access and Data Sharing Policy. Upon acceptance for publication, this dataset will be posted to the CIBMTR Publicly Available data repository found at: https://cibmtr.org/CIBMTR/Resources/Publicly-Available-Datasets# (34).