Abstract

Aims

The study aims to investigate exercise‐limiting factors in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) using combined stress echocardiography and cardiopulmonary exercise test.

Methods and results

A symptom‐limited ramp bicycle exercise test was performed in the semi‐supine position on a tilting dedicated ergometer. Echocardiographic images were obtained concurrently with gas exchange measurements along predefined stages of exercise. Oxygen extraction was calculated using the Fick equation at each activity level. Thirty‐six HCM patients (mean age 67 ± 6 years, 72% men, 18 obstructive HCM) were compared with age and sex‐matched 29 controls. At rest, compared with controls, E/E′ ratio (6.26 ± 2.3 vs. 14 ± 2.5, P < 0.001) and systolic pulmonary artery pressures (SPAP) (22.6 ± 3.4 vs. 34 ± 6.2 mmHg, P = 0.023) were increased. Along with the stages of exercise (unloaded; anaerobic threshold; peak), diastolic function worsened (E/e′ 8.9 ± 2.6 vs. 13.8 ± 3.6 P = 0.011; 9.4 ± 2.3 vs. 18.6 ± 3.3 P = 0.001; 8.7 ± 1.9 vs. 21.5 ± 4, P < 0.001), SPAP increased (23 ± 2.7 vs. 33 ± 4.4, P = 0.013; 26 ± 3.2 vs. 40 ± 2.9, P < 0.001; 26 ± 3.5 vs. 45 ± 7 mmHg, P < 0.001), and oxygen consumption (6.6 ± 1.7 vs. 6.8 ± 1.6, P = 0.86; 18.1 ± 2.2 vs. 14.6 ± 1.5, P = 0.008; 20.3 ± 3 vs. 15.1 ± 2.1 mL/kg/min, P = 0.01) was reduced. Oxygen pulse was blunted (6.3 ± 1.8 vs. 6.2 ± 1.9, P = 0.79; 10 ± 2.1 vs. 8.8 ± 1.6, P = 0.063; 12.2 ± 2 vs. 8.2 ± 2.3 mL/beat, P = 0.002) due to an insufficient increase in both stroke volume (92.3 ± 17 vs. 77.3 ± 14.5 P = 0.021; 101 ± 19.1 vs. 87.3 ± 15.7 P = 0.06; 96.5 ± 12.2 vs. 83.6 ± 16.1 mL, P = 0.034) and oxygen extraction (0.07 ± 0.03 vs. 0.07 ± 0.02, P = 0.47; 0.13 ± 0.02 vs. 0.10 ± 0.03, P = 0.013; 0.13 ± 0.03 vs. 0.11 ± 0.03, P = 0.03). Diastolic dysfunction, elevated SPAP, and the presence of atrial fibrillation were associated with reduced exercise capacity.

Conclusions

Both central and peripheral cardiovascular limitations are involved in exercise intolerance in HCM. Diastolic dysfunction seems to be the main driver for this limitation.

Keywords: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Exercise intolerance, Cardiopulmonary exercise test, Stress echocardiography

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is characterized by reduced exercise capacity. 1 Different contributors were suggested to explain the mechanism behind these findings including increased left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, diminished stroke volume (SV), diastolic dysfunction, and chronotropic incompetence. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 However, most studies were limited due to their retrospective design, lack of control groups, use of obsolete methods for cardiac output (CO) evaluation, non‐separation of obstructive [hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM)] from non‐obstructive HCM (HCMn) and the timing of acquisition of both exercise and post‐exercise haemodynamic and oxygen metabolism parameters. Furthermore, dynamic, exercise‐related changes in chamber size, systolic function, valvular function, and intra‐cavitary pressures, which can be derived from stress echocardiography (SE), 7 could be completed by oxygen metabolism parameters acquired from cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET). 8

In this study, we prospectively evaluated both HOCM and HCMn patients vs. controls using a combined SE with CPET to explore the effect of baseline structural differences and the interplay between cardiac and peripheral responses along pre‐defined stages of exertion.

Methods

Study population

HCM patients underwent a combined SE with CPET due to complaints of exercise intolerance at our centre. Diagnosis of HCM was made 1 based on prior echocardiography and was confirmed during baseline rest echocardiography. Patients in whom a LVOT gradient of >30 mmHg was shown either at rest or during exercise were defined as HOCM. 1

Patients were excluded from the analysis if they could not perform exercise adequately [i.e. could not reach respiratory exchange ratio (RER) > 1, n = 9] or if they had other important cardiac or respiratory limitations including: >mild aortic or tricuspid valvular disease (n = 5), peripheral vascular disease (n = 2), severe pulmonary disease (n = 1), and known infiltrative myocardial disease (e.g. amyloidosis) (n = 2). 9 Following the test, we also excluded patients who were limited due to a small breathing reserve (n = 1), leaving a total of 36 patients for the analysis (Supporting information, Figure S1 ).

Age and gender‐matched, phenotype‐negative patients who were referred for effort dyspnoea assessment during the study period were used as controls (n = 33). Of whom, 1 was excluded due to severely abnormal pulmonary function test and 3 were excluded due to abnormal rest echocardiography (i.e. reduced systolic function, >moderate valvular disease), leaving a total of 29 participants who served as controls (important baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 ). All study participants were ambulatory and clinically stable. The trial was approved by our local ethics committee, and all patients signed an informed consent.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics

| Controls n = 29 | HCM all n = 36 | HCMn n = 18 | HOCM n = 18 | P value, control vs. HCM all | P value, HCMn vs. HOCM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66 ± 6 | 67 ± 6 | 68 ± 8 | 67 ± 7 | 0.24 | 0.58 |

| Male, % | 74 | 72 | 70 | 73 | 0.41 | 0.17 |

| SBP, mmHg | 128 ± 8 | 125 ± 5 | 123 ± 7 | 127 ± 6 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 72 ± 5 | 63 ± 4 | 63 ± 4 | 63 ± 5 | 0.011 | 0.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.3 ± 4.1 | 26.8 ± 6.2 | 28.1 ± 6.8 | 25.8 ± 5.2 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| Hypertension, % | 42 | 39 | 36 | 42 | 0.45 | 0.14 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 22 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 0.16 | 0.63 |

| Hyperlipidemia, % | 58 | 45 | 44 | 45 | 0.12 | 0.87 |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 11 | 36 | 40 | 33 | <0.001 | 0.08 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.09 ± 0.22 | 1.03 ± 0.26 | 1.11 ± 0.45 | 0.97 ± 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.13 |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 14.4 ± 1.8 | 15.1 ± 2.0 | 15.6 ± 2.4 | 14.8 ± 2.6 | 0.35 | 0.19 |

| CAD, % | 24 | 17 | 22 | 13 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Beta‐blockers, % | 28 | 77 | 75 | 80 | <0.01 | 0.51 |

BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HCMn, non‐obstructive HCM; HOCM, obstructive HCM; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Study protocol

The study protocol included a combined SE with CPET and was previously described. 10

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

A symptom‐limited graded ramp bicycle exercise test was performed in the semi‐supine position on a tilting dedicated microprocessor controlled eddy current brake SE cycle ergometer (Ergoselect 1000 L, CareFusion, San Diego, CA, USA). We estimated the expected peak oxygen consumption (VO2 max) on the basis of the patient's age, sex, height, and weight. 8 We then calculated the work rate increment necessary to reach the patient's estimated VO2 max in 8 to 12 min.

The protocol included 3 min of unloaded pedalling, a symptom‐limited ramp graded exercise, and 2 min of recovery. Breath‐by‐breath minute ventilation, carbon dioxide production (VCO2), and oxygen consumption (VO2) were measured using a Medical Graphics metabolic cart (ZAN, nSpire Health Inc., Oberthulba, Germany). VO2 max was the highest averaged 30 s VO2 during exercise. Anaerobic threshold (AT) was determined manually using the modified V‐slope method. The RER was defined as the ratio between VCO2 and VO2 obtained from ventilatory expired gas analysis. 11 Patients were encouraged to continue baseline medical therapy.

In patients on beta‐blocker therapy, chronotropic incompetence was determined when <62% of heart rate (HR) reserve was used. 12

Stress echocardiography

Echocardiographic images were obtained concurrently with breath‐by‐breath gas exchange measurements in a continuous manner along predefined stages of exercise: rest, unloaded cycling, AT, and peak exercise. Rest stage images were taken before cycling. Each cycle of imaging included left ventricular end‐diastolic and end‐systolic volumes, SV, peak E‐ and A‐wave velocities, deceleration time, and septal e′ and lasted between 30 and 60 s. 7 LV end‐diastolic volume, end‐systolic volume, and ejection fraction (EF) were calculated according to the biplane ellipsoid apical 4 chamber area‐length method. Left atrial volume was calculated according to the biplane area‐length method. SV was calculated by multiplying the LVOT area at rest by the LV outflow tract velocity–time integral measured by pulsed‐wave Doppler during each activity level. In case of non‐laminar flow at the LVOT, we measured SV either at the right ventricular outflow tract or by subtracting systolic from diastolic LV volume. 7 LV mass was calculated using the linear method, cube formula 13 :

LV mass (g) = 0.8{1.04[([LVEDD + IVST + PWT]3 − LVEDD3)]} + 0.6, where IVST is interventricular septum thickness, LVEDD is LV end‐diastolic diameter and PWT is posterior wall thickness.

All echocardiographic measurements were performed using manual tracing. 13 We then analysed the echocardiographic data retrospectively at different exercise stages. Unloaded stage images were taken during unloaded exercise. AT and the HR at the AT were determined manually and retrospectively using the gas exchange measurements and the modified V‐slope method. 8 On the basis of the HR at the AT echocardiogram, data were analysed from the images captured immediately after reaching the HR at the AT. Peak exercise images were defined as those captured immediately after reaching RER > 1.05. 11 Arterio‐venous oxygen content (A − VO2) difference was calculated using the Fick equation as follows: (VO2)/(echocardiography − calculated CO) at each activity level. 14

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as frequency and percentage. Not following normal distribution, continuous variables were described as median and inter‐quartile range. In order to compare clinical, echocardiographic, and oxygen metabolism parameters in patients with and without HCM, the two groups were matched according to age and sex.

McNemar test was used to compare categorical variables between the matched groups and Wilcoxon test was performed to compare continuous variables.

To analyse the differences at the different stages of exercise, we used the repeated‐measures linear model analysis to define the within‐group effect for each parameter over time, the between group differences over time, and the group by time interactions. All statistical tests were two sided, and P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

In order to identify predictors of limited maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max<70% predicted 2 ), patients with limited VO2 max were compared with those without using Chi‐squared test or Fisher's exact test for the categorical variables and Mann–Whitney test for the continuous variables. Following univariate analysis, clinically significant variables associated with limited maximal oxygen consumption at a significance level of P < 0.1 were included in multivariable logistic regression. Backward method was applied using P > 0.1 at Wald test as criteria for variables' removal. This analysis was performed in the entire group and then separately in the HCM group.

SPSS software was used for all statistical analyses (IBM SPSS statistic for Windows, version 27, IBM corp., ARMONK, NY, USA, 2020).

Results

Our study group included 36 consecutive HCM patients. Mean age was 67 ± 6 years, 72% were men and 50% (n = 18) had HOCM. This group was compared with 29 age‐ and sex‐matched controls (Table 1 , 2 ). At baseline, compared with controls, HCM patients had higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) (11% vs. 36%, P < 0.001), increased LV mass index (95.3 ± 27.7 vs. 144.8 ± 26.6 g/m2, P < 0.001), increased LVOT gradient (11.4 ± 3.3 vs. 41.8 ± 9.8 mmHg, P < 0.001), worse diastolic function (E/E′ 6.26 ± 2.3 vs. 14 ± 2.5, P < 0.001), and increased systolic pulmonary artery pressure (SPAP) (22.6 ± 3.4 vs. 34 ± 6.2 mmHg, P = 0.023) (Table 1 , 2 ).

Table 2.

Baseline echocardiographic and CPET findings

| Controls n = 29 | HCM all n = 36 | HCMn n = 18 | HOCM n = 18 | P value, control vs. HCM all | P value, HCMn vs. HOCM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDV index, mL/m2 | 68.1 ± 11.9 | 63 ± 9.9 | 62 ± 10.2 | 63 ± 10.3 | 0.08 | 0.66 |

| ESV index, mL/m2 | 25 ± 8.5 | 20.9 ± 6.8 | 22.3 ± 7.8 | 20.4 ± 8 | 0.12 | 0.72 |

| Stroke volume, mL | 76.7 ± 9.5 | 78.3 ± 8.4 | 77.7 ± 8.9 | 79.1 ± 8.9 | 0.17 | 0.44 |

| Cardiac output, L/min | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 1.1 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 0.16 | 0.85 |

| LVEF, % | 61.7 ± 6.5 | 66.1 ± 5.9 | 66.5 ± 6.2 | 65.5 ± 6.3 | 0.1 | 0.37 |

| LVMI, g/m2 | 95.3 ± 27.7 | 144.8 ± 26.6 | 148.8 ± 28.6 | 139.9 ± 29.4 | <0.001 | 0.23 |

| IVS, mm | 9.7 ± 2.3 | 17.6 ± 2.9 | 17.2 ± 3.4 | 18.1 ± 3.5 | <0.001 | 0.14 |

| LVOT gradient, mm/Hg | 11.4 ± 3.3 | 41.8 ± 9.8 | 21.6 ± 12.8 | 58.6 ± 13.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| >mild MR, % | 0 | 28 | 0 | 28 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| LAVI, mL/m2 | 23.2 ± 7.0 | 41.3 ± 12.8 | 44.3 ± 13.8 | 38.4 ± 13.9 | 0.011 | 0.13 |

| E wave, m/s | 0.57 ± 0.11 | 0.91 ± 0.43 | 0.94 ± 0.82 | 0.86 ± 0.69 | 0.12 | 0.64 |

| A wave, m/s | 0.51 ± 0.19 | 0.56 ± 0.37 | 0.57 ± 0.42 | 0.56 ± 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.9 |

| E wave DT, m/s | 198 ± 65 | 201 ± 59 | 207 ± 64 | 195 ± 66 | 0.35 | 0.28 |

| E′. cm/s | 9.1 ± 2.7 | 6.5 ± 3.1 | 6.3 ± 4.1 | 6.8 ± 4 | 0.13 | 0.47 |

| E/E′ ratio | 6.26 ± 2.3 | 14 ± 2.5 | 14.92 ± 3.9 | 12.64 ± 4.7 | <0.001 | 0.26 |

| S′, cm/s | 9.3 ± 1.9 | 6.1 ± 2.0 | 7.1 ± 2.3 | 5.3 ± 2.3 | 0.16 | 0.09 |

| SPAP, mmHg | 22.6 ± 3.4 | 34 ± 6.2 | 34 ± 8.5 | 33.8 ± 7.6 | 0.023 | 0.28 |

| FVC, L | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 0.59 | 0.71 |

| FVC, % predicted | 89.1 ± 15.5 | 84.3 ± 16.0 | 85.3 ± 17.1 | 83.8 ± 17 | 0.13 | 0.21 |

| FEV1, L/s | 3.1 ± 1 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 1.5 | 0.49 | 0.52 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 92 ± 14.6 | 90.1 ± 13.8 | 91 ± 14.4 | 89.3 ± 14.9 | 0.43 | 0.39 |

| FEV1/FVC | 90.1 ± 5.8 | 92.5 ± 6.1 | 92.2 ± 7.1 | 92 ± 7.3 | 0.28 | 0.91 |

| VO2/kg/min | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 0.33 | 1 |

| RER | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 0.78 ± 0.08 | 0.77 ± 0.08 | 0.82 | 0.61 |

| AV difference, L/L | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

A, mitral late flow wave; AV difference, arterio‐venous oxygen extraction; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test; DT, deceleration time; E, mitral early flow wave; E′, mean mitral annulus tissue velocity; EDV, end‐diastolic volume; ESV, end‐systolic volume; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, functional vital capacity; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HCMn, non‐obstructive HCM; HOCM, obstructive HCM; IVS, interventricular septum; LAVI, left atria volume index LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; MR, mitral regurgitation; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; S′, lateral tricuspid valve tissue velocity; SPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure; VO2, oxygen consumption.

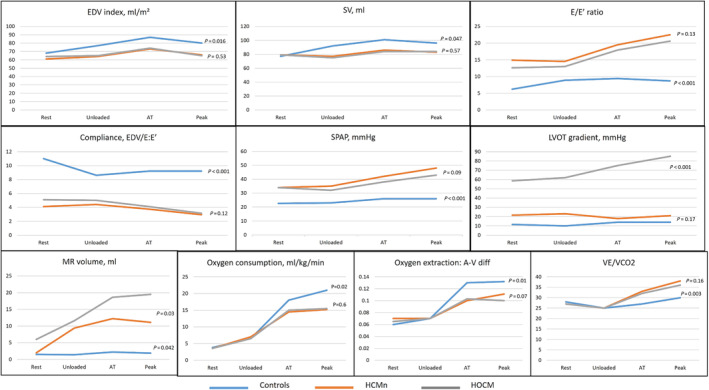

Along the stages of exercise (unloaded; AT; peak), diastolic function worsened (E/e′ 8.9 ± 2.6 vs. 13.8 ± 3.6 P = 0.011; 9.4 ± 2.3 vs. 18.6 ± 3.3 P = 0.001; 8.7 ± 1.9 vs. 21.5 ± 4, P < 0.001), SPAP increased (23 ± 2.7 vs. 33 ± 4.4, P = 0.013; 26 ± 3.2 vs. 40 ± 2.9, P < 0.001; 26 ± 3.5 vs. 45 ± 7 mmHg, P < 0.001), and CO did not increase sufficiently due to blunting of both SV (92.3 ± 17 vs. 77.3 ± 14.5 P = 0.021; 101 ± 19.1 vs. 87.3 ± 15.7 P = 0.06; 96.5 ± 12.2 vs. 83.6 ± 16.1 mL, P = 0.034) and HR (87 ± 10 vs. 83 ± 9, P = 0.3; 118 ± 17 vs. 97 ± 16, P = 0.014; 146 ± 18 vs. 113 ± 15 bpm, P = 0.003) (Figure 1 ). However, the vast majority (86%) of those with blunted HR response were on beta‐blockers, and after correction for beta‐blocker use, chronotropic incompetence was no longer demonstrated. Compared with controls, mitral regurgitation volume increased along the stages of exercise in the entire HCM group (1.4 ± 2 vs. 10.3 ± 4.1, P < 0.001; 2.2 ± 2.9 vs. 14.1 ± 6.6, P < 0.001; 1.9 ± 3.2 vs. 19.9 ± 7.5 mL, P < 0.001) and specifically among HOCM patients (9.4 ± 4.5 vs. 11.6 ± 5.2, P = 0.41, 12.2 ± 7.9 vs. 18.6 ± 8.3, P = 0.027; 11.1 ± 8.8 vs. 19.5 ± 5.4 mL, P = 0.001 in HCMn vs. HOCM, respectively).

Figure 1.

Echocardiographic and oxygen metabolism parameters at baseline, unloaded, anaerobic threshold (AT) and maximal effort in controls (blue), non‐obstructive (HCMn) (red) and obstructive hypertrophic (HOCM) (grey) cardiomyopathy patients. A‐V, arterio‐venous oxygen content difference; EDV, end‐diastolic volume; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; MR, mitral regurgitation; SPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure; SV, stroke volume; VE/VCO2, ratio of ventilation to CO2 production.

Compared with controls, oxygen consumption (6.6 ± 1.7 vs. 6.8 ± 1.6, P = 0.86; 18.1 ± 2.2 vs. 14.6 ± 1.5, P = 0.008; 20.3 ± 3 vs. 15.1 ± 2.1 mL/kg/min, P = 0.01) and oxygen pulse (6.3 ± 1.8 vs. 6.2 ± 1.9, P = 0.79; 10 ± 2.1 vs. 8.8 ± 1.6, P = 0.063; 12.2 ± 2 vs. 8.2 ± 2.3 mL/beat, P = 0.002) were reduced (Figure 1 ). Using Fick equation, it was demonstrated that oxygen pulse was blunted not only due to an insufficient increase in SV but also due to reduced oxygen extraction (0.07 ± 0.03 vs. 0.07 ± 0.02, P = 0.47; 0.13 ± 0.02 vs. 0.10 ± 0.03, P = 0.013; 0.13 ± 0.03 vs. 0.11 ± 0.03, P = 0.03, in the controls vs. HCM, respectively). Reduced ventilatory efficiency (peak VE/VCO2 30.3 ± 3.3 vs. 37.4 ± 4.6, respectively, P = 0.012) and reduced mechanical efficiency (slope of oxygen consumption/work rate 10.16 ± 0.44 vs. 9.26 ± 0.47, respectively, P = 0.009) were found (Figure 1 ).

Limited VO2 max was demonstrated in 20 patients (31%) in the entire cohort and in 16 patients (44%) in the HCM group. Parameters predicting limited maximal oxygen consumption in the entire cohort and in the HCM group are shown in Tables 3 and 4 .

Table 3.

Predictors of limited maximal oxygen consumption in all participants

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| First step | ||

| Age | 0.47–0.73 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.68–0.98 | <0.001 |

| CAD | 0.69–0.94 | 0.12 |

| CKD | 0.62–0.96 | 0.11 |

| AF | 0.55–0.88 | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.89–1.13 | 0.17 |

| IVS thickness | 0.61–0.90 | 0.013 |

| LVOT obstruction | 0.71–1.04 | 0.039 |

| E/E′ | 0.49–0.86 | <0.001 |

| SPAP | 0.56–0.94 | 0.016 |

| Last step | ||

| Age | 0.48–0.70 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.77–1.00 | 0.02 |

| AF | 0.57–0.85 | 0.014 |

| IVS thickness | 0.63–0.88 | 0.065 |

| E/E′ | 0.48–0.80 | 0.08 |

| SPAP | 0.60–0.94 | 0.031 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; FEV1/FVC, forced expiratory volume in 1 s/functional vital capacity; IVS, interventricular septum; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; SPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure.

Table 4.

Predictors of limited maximal oxygen consumption in the HCM group

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| First step | ||

| Age | 0.49–0.78 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.78–1.01 | 0.047 |

| CAD | 0.60–1.02 | 0.16 |

| CKD | 0.72–1.04 | 0.11 |

| AF | 0.59–0.90 | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.78–1.36 | 0.37 |

| IVS thickness | 0.59–0.94 | 0.002 |

| LVOT obstruction | 0.75–1.12 | 0.08 |

| E/E′ | 0.52–0.87 | <0.001 |

| SPAP | 0.59–0.98 | 0.002 |

| Last step | ||

| Age | 0.50–0.82 | 0.021 |

| AF | 0.66–0.91 | 0.09 |

| E/E′ | 0.48–0.89 | 0.027 |

| SPAP | 0.69–0.97 | 0.038 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; FEV1/FVC, forced expiratory volume in 1 s/functional vital capacity; IVS, interventricular septum; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; SPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure.

Discussion

HCM patients are often restricted from sport participation due to concerns regarding heightened risk, 9 , 15 but also suffer from exercise intolerance. In this study, we demonstrated that exercise limitation in HCM is influenced by central and peripheral cardiovascular factors. To do that, we used a combined SE with CPET and examined respiratory, oxygen metabolism, and haemodynamic responses along predefined stages of exercise. Our findings show that oxygen consumption limitation in HCM was affected by different and interacting factors, both central and peripheral.

Diastolic dysfunction

The inability to increase SV was demonstrated early (i.e. at the unloaded phase) and was probably caused by the incapacity of the stiffed ventricle to accommodate the increased venous return from the exercising muscles and is emphasized by the left ventricular reduced compliance shown here.

We found that LVOT obstruction played a lesser role in the blunted SV increase along the stage of exercise, a finding that also corresponds with previous publications. 2 , 3 Nevertheless, compared with the HOCM group, our group of HCMn was found to have an increased LV thickness and worse diastolic function, a factor that might have affected these results.

Notably, microvascular ischaemia was previously demonstrated in HCM 16 , 17 and was found to be directly correlated with both diastolic dysfunction and increased LV mass and therefore could also potentially play a role in the observed blunted SV rise in these patients.

Atrial fibrillation

Irregular heart rhythm disrupts LV filling but may also represent the extreme of diastolic dysfunction. Myocardial fibrosis is common in HCM and may induce atrial stiffening and atrial ectopy, which may culminate to AF. 18 , 19 Recent studies have repeatedly demonstrated the importance of AF in predicting exercise incapacity and clinical outcomes in HCM, which was sometimes stronger than the presence of LVOT obstruction. 20 , 21 Notably, AF was numerically more prevalent in our non‐obstructive HCM group, a factor which may further emphasize the importance of diastolic dysfunction and not necessarily LVOT obstruction as a predictor of exercise intolerance in HCM.

Peripheral oxygen extraction

Oxygen pulse is considered as ‘SV equivalent’ during CPET study. However, as we were able to directly measure SV response along the CPET, we used the Fick equation to examine peripheral oxygen extraction and demonstrated that oxygen pulse limitation was affected not only by the inappropriate increase in SV but also by the inability of peripheral muscles to extract oxygen during exercise. These findings are in line with the reduced mechanical efficiency (i.e. O2 consumption/work load) shown in our study which was also demonstrated by Jones et al. 22 and could be explained by either peripheral myopathy (as a part of HCM manifestation 23 ) or by the deconditioning caused by long‐standing avoidance from exercise in these patients. 24

Furthermore, a ‘flattening’ (i.e. incapacity to appropriately increase oxygen consumption to the level of exercise) of oxygen consumption along the stages of graded exercise was demonstrated. This ‘flattening’ was repeatedly shown to be associated with high‐risk features and worse prognosis. 8 , 25 As shown here, it is the result of multiple contributors to effort intolerance including blunted stroke volume response and worse diastolic function, but also the incapacity of the exercising muscles to appropriately extract oxygen from the blood and corresponds with the decreased mechanical efficiency shown here.

Different studies contributed to the delineation of effort intolerance in HCM, but were limited for different reasons. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 22 , 26 , 27 We have tried to overcome these limitations with the use of combined CPET and SE along predefined stages of exercise conducted in patients and controls of similar age and sex. This combined method allowed us to carefully investigate the effect of different stages of exercise on oxygen metabolism, haemodynamic, and anatomic parameters in HCM.

Our results shed light on potential therapeutics in HCM. First, recent studies on type 2 sodium‐glucose transporter inhibitors (SGLT2i) demonstrated these drugs efficacy in heart failure with preserved EF (HFpEF). 28 , 29 As HCM represents the ‘extreme’ of HFpEF, SGLT2i may show effectiveness in this arena. Second, there is a growing notion that restoring sinus rhythm in AF patients should be aggressively pursuit. 30 , 31 Our results, showing that AF played an important role in exercise limitation in HCM, correspond with these findings and may emphasize the importance of reducing AF burden in HCM.

Our study has a few limitations: first, this is a single‐centre study. However, most studies investigating effort intolerance in HCM had the same limitation. Second, it incorporates a relatively small group of participants (a fact which may have influenced our inability to demonstrate the specific effect of LVOT obstruction on the results). Nevertheless, a similar limitation was present in other trials in this arena and we did show the importance of other parameters on effort intolerance in this group of patients. Third, haemodynamics were not invasively measured. However, our use of echocardiography allowed us to not only report CO and intracardiac pressures but also to examine diastolic function, chamber volumes, and LVOT gradients along the different stages of exercise.

In conclusion, we used a comprehensive protocol to examine characteristics of effort intolerance in HCM and found that dynamic changes in diastolic function, pulmonary hypertension, and peripheral limitation play an important role in exercise incapacity in these patients.

Funding

No.

Conflict of interest

No.

Supporting information

Figure S1: HCM patients in whom other significant cardiovascular or pulmonary limiting pathologies were identified were excluded from the study.

CPET – cardiopulmonary exercise test; SE – stress echocardiography; SPAP – systolic pulmonary artery pressure; EDV – end diastolic volume; SV – stroke volume; LVOT – left ventricular outflow tract; MR – mitral regurgitation; A‐V diff – arterio‐venous oxygen content difference; VE/VCO2 – ratio of ventilation to CO2 production. RER – respiratory exchange ratio, PVD – peripheral vascular disease.

Erez, Y. , Ghantous, E. , Shetrit, A. , Zamanzadeh, R. S. , Zahler, D. , Granot, Y. , Sapir, O. R. , Laufer Perl, M. , Banai, S. , Topilsky, Y. , and Havakuk, O. (2024) Exercise limitation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: combined stress echocardiography and cardiopulmonary exercise test. ESC Heart Failure, 11: 2287–2294. 10.1002/ehf2.14776.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Ommen SR, Mital S, Burke MA, Day SM, Deswal A, Elliott P, et al. 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:e159‐e240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chikamori T, Counihan PJ, Doi YL, Takata J, Stewart JT, Frenneaux MP, et al. Mechanisms of exercise limitation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;19:507‐512. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(10)80262-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Le VV, Perez MV, Wheeler MT, Myers J, Schnittger I, Ashley EA. Mechanisms of exercise intolerance in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J 2009;158:e27‐e34. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mizukoshi K, Suzuki K, Yoneyama K, Kamijima R, Kou S, Takai M, et al. Early diastolic function during exertion influences exercise intolerance in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Echocardiogr 2013;11:9‐17. doi: 10.1007/s12574-012-0150-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Efthimiadis GK, Giannakoulas G, Parcharidou DG, Pagourelias ED, Kouidi EJ, Spanos G, et al. Chronotropic incompetence and its relation to exercise intolerance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2011;153:179‐184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Achim A, Serban AM, Mot SDC, Leibundgut G, Marc M, Sigwart U. Alcohol septal ablation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: for which patients? ESC Heart Fail 2023;10:1570‐1579. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.14272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lancellotti P, Pellikka PA, Budts W, Chaudhry FA, Donal E, Dulgheru R, et al. The clinical use of stress echocardiography in non‐ischaemic heart disease: recommendations from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;17:1191‐1229. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jew190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guazzi M, Arena R, Halle M, Piepoli MF, Myers J, Lavie CJ. 2016 focused update: clinical recommendations for cardiopulmonary exercise testing data assessment in specific patient populations. Eur Heart J 2018;39:1144‐1161. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Authors/Task Force members , Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, Borggrefe M, Cecchi F, et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2733‐2779. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shimiaie J, Sherez J, Aviram G, Megidish R, Viskin S, Halkin A, et al. Determinants of effort intolerance in patients with heart failure: combined echocardiography and cardiopulmonary stress protocol. JACC: Heart Fail 2015;3:803‐814. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guazzi M, Adams V, Conraads V, Halle M, Mezzani A, Vanhees L, et al. EACPR/AHA scientific statement. Clinical recommendations for cardiopulmonary exercise testing data assessment in specific patient populations. Circulation 2012;126:2261‐2274. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826fb946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khan MN, Pothier CE, Lauer MS. Chronotropic incompetence as a predictor of death among patients with normal electrograms taking beta blockers (metoprolol or atenolol). Am J Cardiol 2005;96:1328‐1333. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18:1440‐1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Effect of endurance training on the determinants of peak exercise oxygen consumption in elderly patients with stable compensated heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:120‐128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maron BJ, Desai MY, Nishimura RA, Spirito P, Rakowski H, Towbin JA, et al. Diagnosis and evaluation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: JACC state‐of‐the‐art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:372‐389. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maron MS, Olivotto I, Maron BJ, Prasad SK, Cecchi F, Udelson JE, et al. The case for myocardial ischemia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:866‐875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Achim A, Savaria BU, Buja LM. Commentary on the enigma of small vessel disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: is invasive assessment of microvascular resistance a novel independent predictor of prognosis? Cardiovasc Pathol 2022;60:107448. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2022.107448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kurt M, Wang J, Torre‐Amione G, Nagueh SF. Left atrial function in diastolic heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:10‐15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.813071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chan RH, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Pencina MJ, Assenza GE, Haas T, et al. Prognostic value of quantitative contrast‐enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2014;130:484‐495. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Masri A, Pierson LM, Smedira NG, Agarwal S, Lytle BW, Naji P, et al. Predictors of long‐term outcomes in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy undergoing cardiopulmonary stress testing and echocardiography. Am Heart J 2015;169:684‐692.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peteiro J, Bouzas‐Mosquera A, Fernandez X, Monserrat L, Pazos P, Estevez‐Loureiro R, et al. Prognostic value of exercise echocardiography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2012;25:182‐189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jones S, Elliott PM, Sharma S, McKenna WJ, Whipp BJ. Cardiopulmonary responses to exercise in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart 1998;80:60‐67. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.1.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Caforio AL, Rossi B, Risaliti R, Siciliano G, Marchetti A, Angelini C, et al. Type 1 fiber abnormalities in skeletal muscle of patients with hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy: evidence of subclinical myogenic myopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989;14:1464‐1473. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90383-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Snir AW, Connelly KA, Goodman JM, Dorian D, Dorian P. Exercise in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: restrict or rethink. Am J Physiol‐Heart Circ Physiol 2021;320:H2101‐H2111. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00850.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guazzi M, Adams V, Conraads V, Halle M, Mezzani A, Vanhees L, et al. EACPR/AHA joint scientific statement. Clinical recommendations for cardiopulmonary exercise testing data assessment in specific patient populations. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2917‐2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dumont CA, Monserrat L, Peteiro J, Soler R, Rodriguez E, Bouzas A, et al. Relation of left ventricular chamber stiffness at rest to exercise capacity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1454‐1457. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lafitte S, Reant P, Touche C, Pillois X, Dijos M, Arsac F, et al. Paradoxical response to exercise in asymptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a new description of outflow tract obstruction dynamics. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:842‐850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Bocchi E, Böhm M, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2021;385:1451‐1461. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Claggett B, De Boer RA, DeMets D, Hernandez AF, et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2022;387:1089‐1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marrouche NF, Brachmann J, Andresen D, Siebels J, Boersma L, Jordaens L, et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2018;378:417‐427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sohns C, Fox H, Marrouche NF, Crijns HJGM, Costard‐Jaeckle A, Bergau L, et al. Catheter ablation in end‐stage heart failure with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1380‐1389. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2306037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: HCM patients in whom other significant cardiovascular or pulmonary limiting pathologies were identified were excluded from the study.

CPET – cardiopulmonary exercise test; SE – stress echocardiography; SPAP – systolic pulmonary artery pressure; EDV – end diastolic volume; SV – stroke volume; LVOT – left ventricular outflow tract; MR – mitral regurgitation; A‐V diff – arterio‐venous oxygen content difference; VE/VCO2 – ratio of ventilation to CO2 production. RER – respiratory exchange ratio, PVD – peripheral vascular disease.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.