Abstract

Background

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) courses with inflammation and cognitive decline. Apolipoproteins have emerged as novel target compounds related to inflammatory processes and cognition.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed on abstinent AUD patients with at least 1 month of abstinence (n = 33; 72.7% men) and healthy controls (n = 34; 47.1% men). A battery of plasma apolipoproteins (APOAI, APOAII, APOB, APOCII, APOE, APOJ, and APOM), plasma inflammatory markers (LPS, LBP), and their influence on cognition and presence of the disorder were investigated.

Results

Higher levels of plasma APOAI, APOB, APOE, and APOJ, as well as the proinflammatory LPS, were observed in the AUD group, irrespective of sex, whereas APOM levels were lower vs controls. Hierarchical logistic regression analyses, adjusting for covariates (age, sex, education), associated APOM with the absence of cognitive impairment in AUD and identified APOAI and APOM as strong predictors of the presence or absence of the disorder, respectively. APOAI and APOM did not correlate with alcohol abuse variables or liver status markers, but they showed an opposite profile in their associations with LPS (positive for APOAI; negative for APOM) and cognition (negative for APOAI; positive for APOM) in the entire sample.

Conclusions

The HDL constituents APOAI and APOM were differentially regulated in the plasma of AUD patients compared with controls, playing divergent roles in the disorder identification and associations with inflammation and cognitive decline.

Keywords: Apolipoprotein, ApoE4, cognition, HDL, LPS

Significance Statement.

Cognitive impairment is a common feature among alcohol use disorder (AUD)-diagnosed individuals, ranging from absent to severe cognitive deterioration. Early identification of vulnerable patients with cognitive impairment attending an alcohol detoxification program would help the clinicians to provide them with proper assistance, since the diagnostic procedures for cognitive impairment rely on resource-intensive neuropsychological evaluations, often leading to delays in patient categorization and intervention. Our pilot study investigates peripheral biomarkers associated with diagnosis and associated cognitive impairment by understanding the relationship between plasma apolipoproteins, inflammation and cognitive decline in AUD. We showed elevated APOAI and decreased APOM plasma levels associated with inflammation and cognitive deterioration in patients, helping to identify the presence/absence of the disorder and cognitive status. Our study offers a preliminary quantifiable biological approach to support neuropsychological assessment and diagnostic procedures, since we identified plasma APOAI and APOM as potential biomarkers for AUD and related cognitive decline.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) and Cognitive Function

AUD is associated with health systems burden, with prevalent cognitive impairment affecting memory, attention, executive function, or visuospatial abilities (Perry, 2016; Aharonovich et al., 2018; Visontay et al., 2021; Ramos et al., 2022). The degree of severity ranges from absent to severe cognitive deterioration (Hayes et al., 2016). Early identification of cognitively impaired patients in alcohol detoxification programs would help the clinicians provide them with proper assistance. Current diagnostic procedures for cognitive impairment involve neuropsychological evaluations, but they entail a high healthcare burden, with limited availability of professionals and delay in categorization of patients. Objective diagnostic procedures based on biomarkers related to AUD and cognitive impairment could supplement clinical practices. This approach may aid in timely referral of patients during detoxification programs and potentially lead to the discovery of new therapeutic strategies.

Advances in Biomarker Research

Biological factors related to impaired cognition in AUD are still largely unknown. Alcohol abuse induces neuroinflammation, contributing to cognitive and emotional alterations (Spear, 2018). Exploring the microbiota-gut-brain axis and alcohol-induced inflammation offers new avenues for identifying potential biomarkers of cognitive decline in AUD (Orio et al., 2019; Rodriguez-Gonzalez et al., 2020; Escudero et al., 2023). Our previous studies showed that elevations in proinflammatory molecules in peripheral blood mononuclear cells or plasma of women binge drinkers were associated with worse scores in cognitive flexibility and episodic memory (Orio et al., 2018). Specifically, elevated endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) plasma levels were negatively correlated with scores on delayed recall (Orio et al., 2018). Recent studies highlight the potential of peripheral cytokines and inflammatory-related molecules as biomarkers of alcohol consumption or cognitive impairment in AUD patients (García-Marchena et al., 2020; Requena-Ocaña et al., 2022; Escudero et al., 2023). However, identifying reliable peripheral biomarkers for detecting cognitive impairment in AUD remains a scientific challenge.

Apolipoproteins have emerged as novel target molecules related to inflammatory processes and cognition. APOE is the most studied in the context of alcohol abuse (Downer et al., 2014; Slayday et al., 2021), since the isoform APOE4 appears to have a role in neuroinflammation (Kloske and Wilcock, 2020; Duro et al., 2022) and cognitive impairment (reviewed in Parhizkar et al., 2022). Recently, we observed that AUD patients carrying the APOE4 isoform exhibited higher levels of plasma Reelin (a protein that shares receptors with APOE4) and more severe cognitive impairment (Escudero et al., 2023). There are other plasma apolipoproteins, such as APOAI, APOB, APOCIII, APOE, APOH, APOM, or APOJ that emerge as interesting candidates in this field. Some of them fluctuate in plasma from mid-life and have been related to mild cognitive impairment in old individuals (Song et al., 2012; Muenchhoff et al., 2017) and/or associated with Alzheimer´s disease or dementia (Reynolds et al., 2010; Koch et al., 2018; Chan et al., 2020; Zuin et al., 2021; Xin et al., 2022).

Possible Explaining Mechanisms

Alcohol abuse triggers peripheral inflammation by disrupting the gut barrier (leaky gut), leading to the translocation of bacterial LPS from Gram-negative bacteria to the bloodstream in preclinical models (Antón et al., 2018a, 2018b) and in alcohol-dependent individuals (Keshavarzian et al., 2009; Leclercq et al., 2012; Bala et al., 2014). LPS translocation has been linked to inflammation and activation of the innate immune system, which are closely related to neuroinflammation and behavioral alterations (Dantzer et al., 2008; Alfonso-Loeches et al., 2010; Pascual et al., 2011, 2014; Crews et al., 2013; Leclercq et al., 2014; Sayd et al., 2015; Antón et al., 2017; Erickson et al., 2019). The alcohol-induced neuroinflammatory effects are enhanced by external administration of LPS in mice (Qin et al., 2008). LPS is transported in blood by the Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein (LBP) (Opal et al., 1999), which transfers it to its receptor or into lipoproteins (Levels et al., 2005). Apolipoproteins, natural components of lipoproteins, are related to inflammation (Castellani et al., 1997; Berbée et al., 2005; Mousa et al., 2023) and cognition (Lewis et al., 2010; Koch et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2020; Romagnoli et al., 2021), including APOE4 (Kloske and Wilcock, 2020; Duro et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022).

Increasing evidence suggests that some apolipoproteins may be involved in the detoxification of bacterial LPS, acting as part of the innate immune system (Berbée et al., 2005; Smoak et al., 2010). We observed that APOAI was elevated in plasma and formed aggregates with LPS components within the brain in preclinical models of alcohol abuse, potentially participating in neuroinflammation (Orio et al., 2023; López-Valencia et al., 2024).

Hypothesis

This pilot investigation aims to explore possible associations among apolipoproteins, inflammation, and cognitive decline in AUD patients. Existing literature suggests that alcohol-induced inflammation is negatively associated with cognition, and some apolipoproteins, such as APOE4, may serve as biomarkers for alcohol-induced neuroinflammation and cognitive decline. Emerging evidence suggests that other apolipoproteins may be related to inflammation and modulate cognition in other pathologies, although the direction of influence, if any, is not clear. In the field of alcohol abuse, the relationships among inflammation, apolipoproteins, and cognition are highly unexplored.

We hypothesized that (1) apolipoproteins (APO: AI, AII, B, CII, E, J, and M) and inflammatory markers (LPS, LBP) in plasma are differently regulated in AUD vs controls, while considering sex as a variable; (2) these parameters are associated with the cognitive status of AUD patients or the presence of the disorder. We hypothesized a negative association between inflammation and cognition, but the direction may be different (positive/negative) for each apolipoprotein according to the literature, sometimes controversial (Vuilleumier et al., 2013), and controlling for age, sex, and education as covariates; (3) apolipoproteins related to AUD are associated with alcohol-induced inflammation. We searched for plasma biomarkers of cognitive impairment in AUD patients undergoing an alcohol detoxification program and, ultimately, those that could potentially identify the disorder.

METHODS

Study Participants

A total of 76 participants (Caucasian) were initially recruited: (1) the AUD group (n = 39 from an outpatient alcohol program at Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre in Madrid, Spain) (see supplementary Methods 1.1); (2) the control group (n = 37 healthy controls). The final sample (33 AUD and 34 controls) is reported in supplementary Methods 1.2, Figure S1. The AUD group underwent both pharmacological and psychological interventions as part of the alcohol program.

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria included age ≥18 to 65 years old. In patients, AUD diagnosis was conducted by expert clinicians based on DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2014). Abstinence, at least 4 weeks to minimize the potential influence of recent alcohol use (Escudero et al., 2023), was monitored through exhaled breath control.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included psychiatric comorbidity, assessed by the Spanish version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Ferrando et al., 1998) and DSM-5 (APA, 2014); a history of abuse or dependence to other drugs except tobacco (including alcohol in the control group); chronic medical conditions; infectious diseases (e.g., HIV and/or acute hepatitis); liver diseases (chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, or liver cancer); and chronic use of anti-inflammatory medication. More details in supplementary Methods 1.2.

This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (Madrid, Spain) (Nº CEIm: 19/002) and was conducted in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent, and data were kept anonymous and confidential through coding.

Neuropsychological and Clinical Assessment

All participants were assessed by a cognitive screening test specifically validated for AUD: Test of Detection of Cognitive Impairment in Alcoholism (TEDCA) (Jurado-Barba et al., 2017). Cognitive impairment was determined based on the general cognitive functioning (GCF) score (cut-off point ≤ 10.5) (supplementary Methods 1.3; supplementary Table 1 for details).

Patients and controls were assessed for depressive and anxiety symptomatology (in absence of a psychiatric diagnosis), using The Beck Depression Inventory-II and Beck Anxiety Inventory, respectively (supplementary Methods 1.4.).

Sample Collection and Processing

Blood (20 mL) was collected in the morning (8:00–9:00 am) by nurse personnel after a fasting period of 8–12 hours. The blood was drawn by venipuncture into BD vacutainer tubes containing K2-EDTA anticoagulant (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Plasma was obtained by centrifugation at 1800 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C following our previous studies (Escudero et al., 2023). All samples were coded anonymously and stored at −80°C until immunoassay analysis.

Alcohol Abuse Variables and Liver Status Parameters

A semi-structured interview was administered to both groups to obtain data regarding their alcohol consumption history and the use or abuse of other substances. Patients were asked questions about the type of beverage consumed, quantity, time of abstinence, etc. The liver status of the AUD group was checked by analysis of plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin, which are commonly used in clinical practice. When liver damage was suspected, patients underwent liver ultrasound examinations in the Digestive Department (supplementary Methods 1.5). No liver analyses were conducted in the control group, assuming a sample of healthy controls.

Multiplex Immunoassay Technology and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Plasma concentrations of apolipoproteins were measured using MAGPIX multiplexed immunoassay platform (Luminex Corporation). LPS and LBP were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay commercial kits, following the manufacturer’s instructions (for details, see supplementary Methods 1.6).

Statistical Analyses

Frequency and descriptive statistics were presented as percentages [N (%)] or means with SDs [mean (SD)]. Outliers were identified using the Grubb test. Sociodemographic differences between the AUD and control groups were examined using Fisher exact test, chi-square test, or Student t test. Two-way ANCOVAs, considering group and sex as factors, were applied to analyze plasma biological markers and cognition, controlling for age and/or education. Hierarchical logistic regression models, adjusting for significant (age, P < .05) or marginally significant (sex and education, P = .050 and P = .053, respectively) covariates, assessed the biomarkers’ contribution to explain GCF deficit or AUD presence (supplementary Methods 1.7), alongside receiving operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Pearson correlation analyses with 1% false discovery rate (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) were conducted to explore associations between apolipoproteins with inflammation, alcohol abuse, or liver variables. Results were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 and SPSS 25.0,with a significance threshold set at P < .05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Sample

Table 1 shows sociodemographic variables for the AUD and control groups, emotional symptomatology and pharmacological treatments. Both groups had similar BMI but differed significantly in age (P = .000). Sex approached statistical significance (P = .05). Although the AUD group showed trends of lower education levels and higher unemployment rates, these differences were not statistically significant (Table 1). Tobacco consumption did not differ between groups. Disulfiram was the most frequently used psychiatric medication, followed by antidepressants, whereas none of the control group received psychiatric medication. Some patients presented psychological symptomatology, including minimal depressive symptoms and mild anxiety, with minimum scores in controls. Statistically significant differences in depressive (P = .001) and anxious symptoms (P = .006) were observed between groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

| Variable | AUD (n = 33) | Control (n = 34) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [mean, (SD)] | y | 49.36 (7.41) | 37.41 (12.61) | .000 a |

| BMI [mean, (SD)] | kg/m2 | 26.44 (4.84) | 24.44 (3.90) | .066a |

| Sex [N, (%)] | Women | 9 (27.3) | 18 (52.9) | .050b |

| Men | 24 (72.7) | 16 (47.1) | ||

| Education [N, (%)] | Basic (no and yes high school degree) | 12 (36.4) | 5 (14.7) | .053b |

| Higher (college degree) | 21 (63.6) | 29 (85.3) | ||

| Current work status [N, (%)] | Employed | 26 (78.8) | 32 (94.1) | .083b |

| Unemployed | 7 (21.2) | 2 (5.9) | ||

| Current smoking status [N, (%)] | Yes | 20 (60.6) | 16 (47.1) | .337c |

| Former | 5 (15.2) | 4 (11.8) | ||

| No | 8 (24.2) | 14 (41.2) | ||

| Psychiatric medication use [N, (%)] | Antidepressants | 16 (48.5) | No use | — |

| Anxiolytics | 7 (21.2) | No use | — | |

| Anticonvulsants | 14 (42.4) | No use | — | |

| Antipsychotics | 4 (12.1) | No use | — | |

| Disulfiram | 29 (87.9) | No use | — | |

| Emotional symptomatology [mean (SD)] | Depressive (BDI-II) | 11.61 (10.53) | 4.76 (3.51) | .001 a |

| Anxious (BAI) | 11.21 (13.57) | 4.09 (3.13) | .006 a | |

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; BMI, body mass index.

Anthropometric measures assessed: weight, height, and body mass index (BMI represent weight in kg/height squared). Data are expressed as mean (SD). The significant values (P < .05) are denoted by bold entries in the table.

a Student t test.

b Fisher exact test.

c Chi-square test.

The alcohol abuse outcomes and liver status markers in the AUD group are shown in Table 2. In the control group, the number of standard drinking units (SDU) per month was 7.50 ± 6.02 (mean ± SD). The liver status fell within normal ranges, according to European standards.

Table 2.

Alcohol Abuse Outcomes and Liver Status in the AUD Group

| Alcohol abuse variables [mean, (SD)] N = 33 |

Duration of alcohol abuse since last relapse (weeks) | 37.67 (19.28) | |

| Age of first alcohol consumption (years old) | 15.12 (3.72) | ||

| Age of problematic drinking initiation (years old) | 29.91 (11.22) | ||

| Duration of abstinence since last consumption at recruitment (days) | 44.94 (16.45) | ||

| SDU per month | 24.88 (13.02) | ||

| Liver status markers [mean, (SD)] N = 30–33 |

ALT (U/L) (n = 33) | 32.42 (26.36) | |

| AST (U/L) (n = 33) | 30.09 (26.24) | ||

| GGT (U/L) (n = 32) | 54.78 (59.05) | ||

| ALP (U/L) (n = 30) | 81.03 (23.28) | ||

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) (n = 31) | 0.57 (0.37) | ||

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; AUD, alcohol use disorder; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; SDU, standard drinking units.

The duration of alcohol abuse variable refers to the length of time the patient has been consuming alcohol since their last relapse. Standard drinking units stands for volume of alcohol in liters times the percentage of alcohol contained in the beverage times 0.8 (because 1 mL of alcohol contains 0.785 g of alcohol). The European reference values (inner and upper limits) for each parameter (IU/L) are: ALT: 5–45; AST: 5–33; GGT: 8–61; ALP: 40–130; bilirubin: 0.2–1.0. Data (n = 30–33) are expressed as mean (SD).

Plasma Apolipoprotein Levels

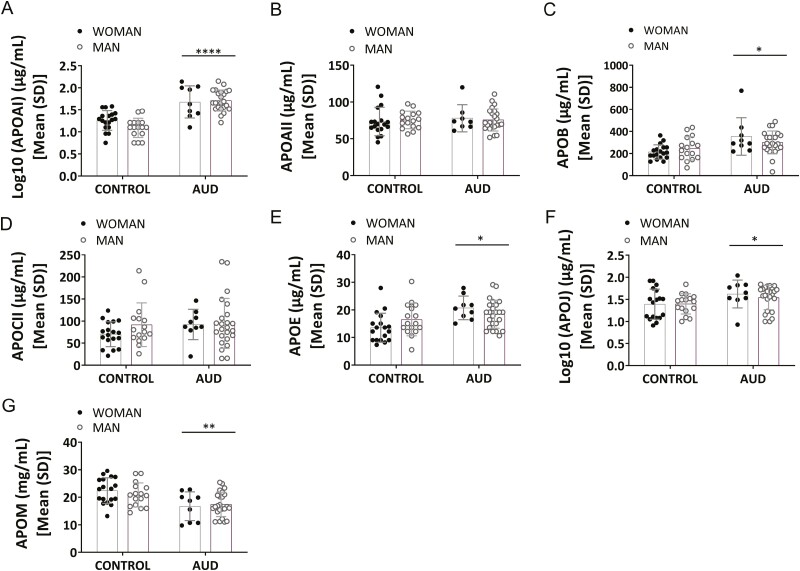

Figure 1 shows plasma apolipoproteins (APOAI, APOAII, APOB, APOCII, APOE, APOJ, APOM) in the AUD and control groups disaggregated by sex. The 2-way ANCOVAs with group and sex as factors, controlling for age, indicated a group effect in plasma APOAI, APOB, APOE, and APOJ [Figure 1A, log10(APOAI): F(1,61) = 48.20, P = .000, η2 = 0.44 (to be noted a substantial magnitude of effect)] [Figure 1C, APOB: F(1,62) = 6.41, P = .014, η2 = 0.09] [Figure 1E, APOE: F(1,62) = 4.31, P = .042, η2 = 0.06] [Figure 1F, log10(APOJ): F(1,62) = 6.75, P = .012, η2 = 0.10], with higher levels in the AUD group. Plasma APOM showed an inverse profile to other apolipoproteins, showing a significant group effect, with lower levels in the AUD patients compared with the control participants (Figure 1G, APOM: [F(1,62) = 10.06; P = .002; η2 = 0.14]). There was no effect of sex for any of the apolipoproteins (P > .05). Total apolipoprotein levels for each group are reported in supplementary Results 2.1 and supplementary Table 3. Age did not modulate these results for apolipoproteins (P > .05), except for APOCII [Figure 1D; F(1,62) = 5.88; P = .018, η2 = 0.09], but there was no group effect for APOAII (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Analysis of plasma apolipoproteins (APO) in the alcohol use disorder (AUD) and control groups: (A) log10 (APOAI), (B) APOAII, (C) APOB, (D) APOCII, (E) APOE, (F) log10 (APOJ), and (G) APOM. Results are presented as mean (SD). Two-way ANCOVAs (group and sex), controlling for age, were conducted. n = 32–33 (AUD group); n = 34 (control group). Overall effect of group is indicated by *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, and ****P < .0001.

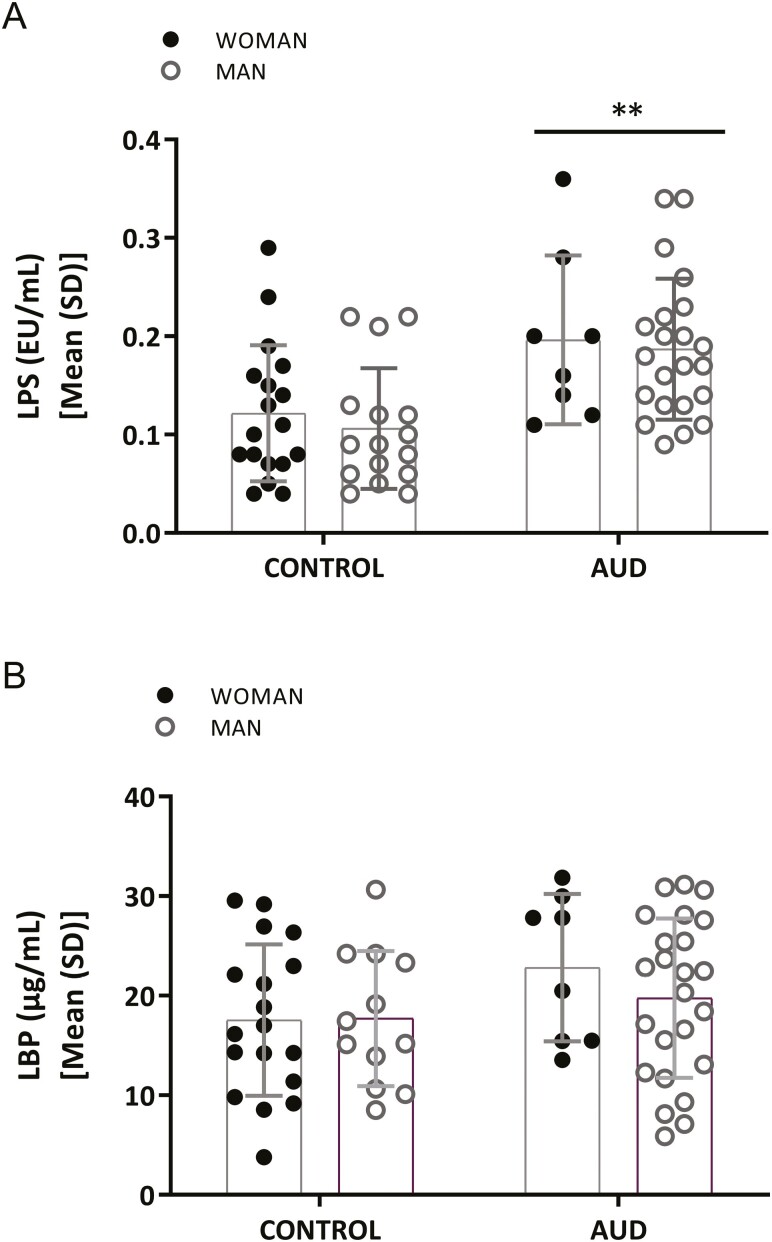

Plasma Inflammatory Parameter Levels

Figure 2 displays plasma inflammatory parameters (LPS, LBP) in the AUD and control groups, divided by sex. Two-way ANCOVAs with group and sex as factors and controlling for age revealed a group effect in plasma LPS [F(1,59) = 11.36, P = .001, η2 = 0.16], disregarding sex, with higher levels in AUD patients than in controls (Figure 2A). LBP data showed no significant group differences, and no sex effect was found either (Figure 2B). Total levels in each group without division by sex are reported in supplementary Results 2.1 and supplementary Table 3.

Figure 2.

Analysis of plasma inflammatory parameters in the alcohol use disorder (AUD) and control groups: (A) LPS, (B) LBP. Results are presented as mean (SD). Two-way ANCOVAs (group and sex), controlling for age, were conducted. n = 30–32 (AUD group); n = 34 (control group). Overall effect of group is indicated by *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, and ****P < .0001.

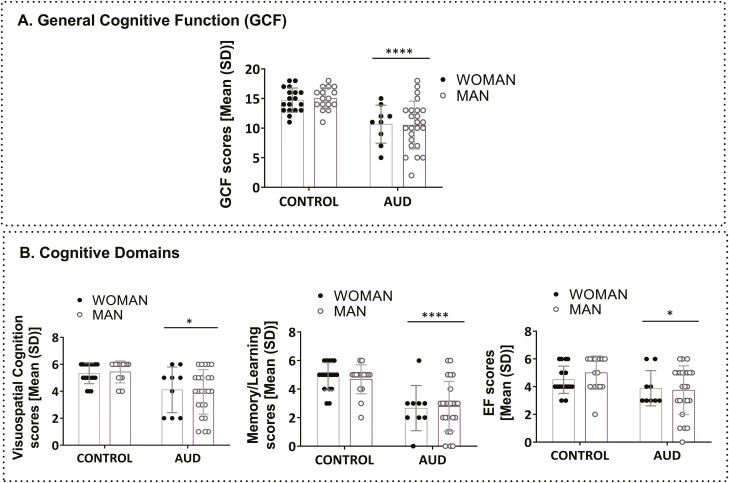

Neuropsychological Data

Figure 3 illustrates cognitive data in AUD and control groups. Two-way ANCOVAS, with age and education as covariates, revealed a group effect in GCF (Figure 3A; GCF: F(1,61) = 15.06, P = .000, η2 = 0.20). The AUD group showed a GCF deficit in 45.5% of the AUD sample (cut-off point ≤ 10.5). Lower scores also were found in all cognitive subdomains (Figure 3B; left panel: visuospatial cognition: F(1,61) = 6.58, P = .013, η2 = 0.44; middle panel: memory/learning: F(1,61) = 16.57, P = .000, η2 = 0.21; and right panel: EF: F(1,61) = 5.62, P = .021, η2 = 0.08) for the AUD group, since memory/learning was the most affected subdomain.

Figure 3.

Analysis of cognitive performance in the alcohol use disorder (AUD) and control groups: (A) general cognitive functioning (GCF), (B) cognitive domains: visuospatial cognition, memory/learning, EF. Results are presented as mean (SD). Two-way ANCOVAs (group and sex), controlling for age and education, were conducted. n = 33 (AUD group); n = 34 (control group). Overall effect of group is indicated by *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, and ****P < .0001. Abbreviations: EF, executive function; Visuospatial, visuospatial cognition.

Contribution of Apolipoproteins and Inflammation to AUD-Induced Cognitive Impairment

Hierarchical logistic regression models were used to determine the biomarkers’ contribution to explaining the GCF deficit. The analysis used a 2-block approach: (block 1) included mandatory covariates: age, sex, and education; (block 2) added significant biomarkers identified through Pearson correlation analyses.

Pearson Correlation Analyses

Negative correlations with GCF were found in patients for APOE [(r = −0.61, P = .000, q = 0.00) and LPS (r = −0.66, P = .000, q = 0.000)], whereas APOM showed a positive association (r = 0.63, P = .000, q = 0.00). These analyses allowed us to depict the biomarkers to be introduced in block 2 and provided insight into their directional associations (positive or negative). Other parameters did not show significant associations (P > .05) (Pearson correlation analyses, after false discovery rate 1% adjustment; see supplementary Results 2.2; supplementary Table 4).

Hierarchical Logistic Regression Model

We introduced significant biomarkers (APOE, APOM, LPS) found in block 2 after introducing all covariates (age, sex, education) in block 1. Only APOM showed significance up to the final model (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.660; Hosmer and Lemeshow = 0.889). The equation results were [−0.140 × age] + [0.907 × sex] + [2.768 × education] + [−0.782 × APOM]. APOM was significant (P = .012), with an OR = 0.458 showing an inverse association. Specifically, the risk of GCF deficit in the AUD group decreased by 54.2% [(e0.782 × 1-1) × 100] for each increased unit of APOM, after controlling for covariates. Therefore, higher plasma APOM levels identified the absence of cognitive impairment in the AUD group. Results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Logistic Regression Model Showing the Association Between Biomarkers (Apolipoproteins and Inflammatory Markers) With GCF Deficit

| Variables entered | B | SE | Wald | OR (95 % CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.14 | 0.19 | 1.64 | 0.87 (0.70–1.08) | .20 |

| Sex | 0.91 | 1.71 | 0.28 | 2.48 (0.09–70.23) | .59 |

| Education | 2.77 | 1.72 | 2.59 | 15.92 (0.55–461.97) | .11 |

| APOM | −0.78 | 0.31 | 6.38 | 0.46 (0.25–0.84) | .01 |

Abbreviations: B, coefficient; CI, confidence interval; GCF, general cognitive functioning; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error; Wald, Wald test.

Hierarchical logistic regression model included APOE, APOM, and LPS, controlled by age, sex, and educational level. Table shows final model (step 1), with APOM showing significance. The significant values (P < .05) are denoted by bold entries in the table.

Identifying AUD Presence

We used hierarchical logistic regression models to address whether plasma apolipoproteins and/or inflammatory markers could identify the presence of AUD. Block 1 introduced covariates age, sex, and education as control factors, and block 2 introduced only significant biomarkers that showed an effect of group in the ANCOVAs previously performed (see Figure 1).

Among all significant biomarkers differentially regulated in AUD (APOAI, APOB, APOE, APOJ, APOM, LPS; Figures 1 and 2), only APOAI and APOM showed significance up to the final model (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.899; Hosmer and Lemeshow = 0.959). The resulting equation was [0.171 × age] + [0.743 × sex] + [2.629 × education] + [0.336 × APOAI] + [−0.621 × APOM]. APOAI had an OR = 1.399, meaning that for each increased unit of this biomarker, the risk of AUD increased 39.9% [(e0.399 × 1–1) × 100], after controlling for covariates. For APOM (OR = 0.537), the risk of the disorder decreased by 46.3% [(e0.621 × 1–1) × 100] for each unit of increase after controlling for covariates. The possible contribution of age to the disorder’s presence is not ruled out (P = .05), with a lower risk percentage (18.6% [(e0.171 × 1−1) x 100]). Results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Logistic Regression Model Showing the Association Between Biomarkers (Apolipoproteins and Inflammatory Markers) and Presence of AUD

| Variables entered | B | SE | Wald | OR (95 % CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.17 | 0.09 | 3.92 | 1.19 (1.00–1.40) | .05 |

| Sex | 0.74 | 1.50 | 0.24 | 2.10 (0.11–40.09) | .62 |

| Education | 2.63 | 2.13 | 1.53 | 13.86 (0.21–896.84) | .22 |

| APOAI | 0.34 | 0.16 | 4.43 | 1.40 (1.02–1.91) | .03 |

| APOM | −0.62 | 0.31 | 3.97 | 0.53 (0.29–0.99) | .04 |

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; B, coefficient; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error; Wald, Wald test.

Hierarchical logistic regression model included APOAI, APOB, APOE, APOJ, APOM, and LPS, controlled by age, sex, and educational level. Table shows final model (step 2), with APOAI and APOM showing significance. The significant values (P < .05) are denoted by bold entries in the table.

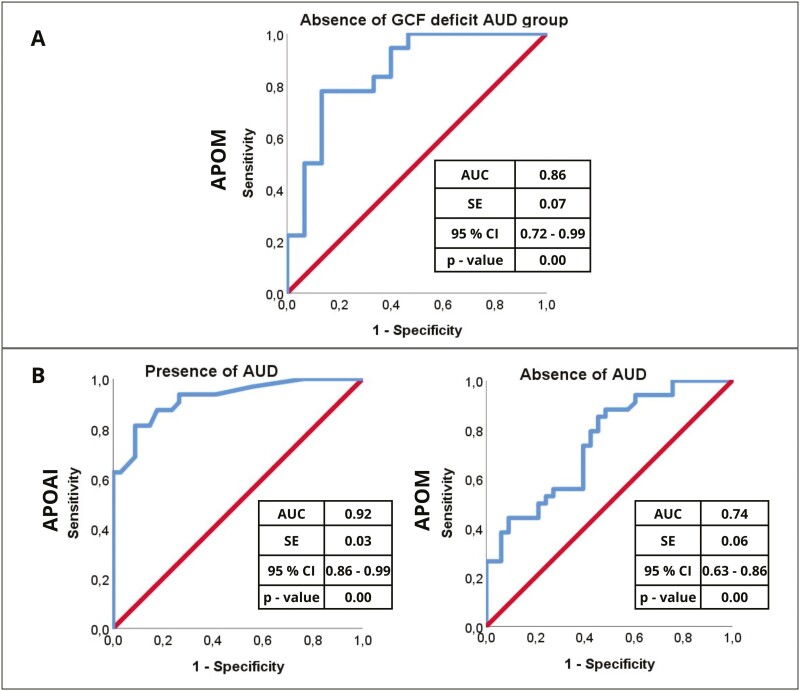

ROC Analysis of the Association Between Biomarkers and Cognition or Identification of the Disorder

An ROC curve was performed for APOM in the AUD group to elucidate the absence of GCF deficit (Figure 4A). The area under the curve for APOM was 0.86 (95% CI = 0.72 to 0.99), suggesting a robust ability of plasma APOM to predict the absence of cognitive impairment. Similarly, ROC curves were performed for APOAI and APOM (Figure 4B) to explain the presence (APOAI) or absence (APOM) of AUD, respectively. The area under the curve for APOAI was 0.92 (95% CI = 0.86 to 0.99) (Figure 4B, left panel) and 0.74 for APOM (95% CI = 0.63 to 0.86) (Figure B, right panel). This suggests that APOAI may have a robust discriminatory power in distinguishing patients with AUD from controls.

Figure 4.

ROC analysis for hierarchical logistic regression models. (A) General cognitive functioning (GCF) deficit as a dependent variable in the alcohol use disorder (AUD) group. (B) Presence of AUD as a dependent variable in the entire sample. The graph shows the trade-off between sensitivity (y-axis) and 1-specificity (x-axis). Both axes of the graph include values between 0 and1 (0% to 100%). The line drawn from point 0.0 to point 1.0 is called the reference diagonal, or the line of non-discrimination. Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval.

Exploring Possible Mechanisms

As previously explained, we found changes in plasma APOAI, APOB, APOE, APOJ, and APOM compared with the control group. We found that APOM was associated with impaired cognition in patients and that increased APOAI along with decreased APOM levels in plasma identified the presence of the disorder (with a possible contribution of age). In this section, we conduct a preliminary exploration of the factors that may be associated with the observed changes in APOAI and APOM levels in plasma.

Alcohol Abuse Variables

The alcohol abuse outcomes in the AUD group are shown in Table 2. No significant correlations were observed between significant apolipoproteins and these alcohol variables (Pearson correlations; P > .05; data not shown).

Liver Status

The liver status markers in the AUD group are shown in Table 2. No significant correlations between significant apolipoproteins and liver parameters were found (Pearson correlation P > .05; data not shown).

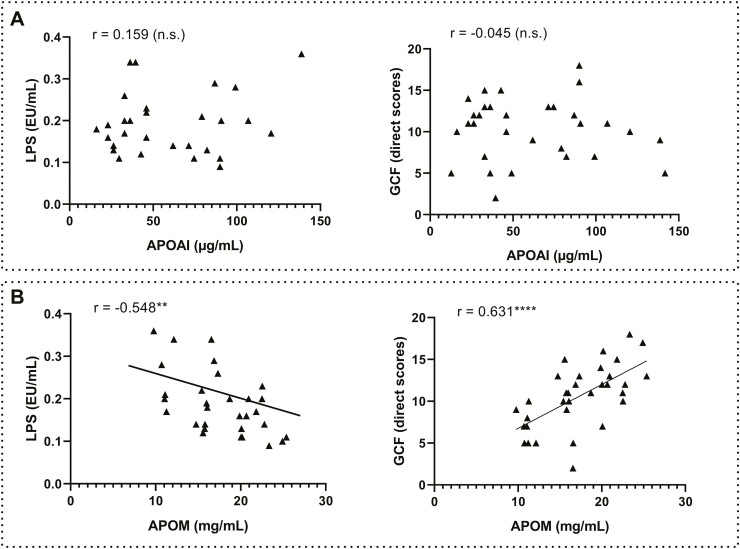

Pro-inflammatory State

We found modest and opposite associations between selected apolipoproteins and LPS (Pearson correlation analysis) and no associations with LBP (P > .05; data not shown). APOAI was not associated with LPS (r = 0.159, P = .410, n.s.) or cognition (r = −0.045, P = .808, n.s.) in the AUD group (Figure 5A), and only APOM was negatively (associated with LPS r = −0,548, P = .002) and positively associated with cognition (r = 0.631, P = .000) in the AUD group (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Correlations between plasma apolipoproteins APOAI/APOM with inflammation and cognition in the alcohol use disorder (AUD) group. (A) APOAI with LPS (left) and general cognitive functioning (GCF) scores (right). (B) APOM with LPS (left) and GCF scores (right). Significantly different: **P < .01; ****P < .0001. Abbreviation: n.s., nonsignificant.

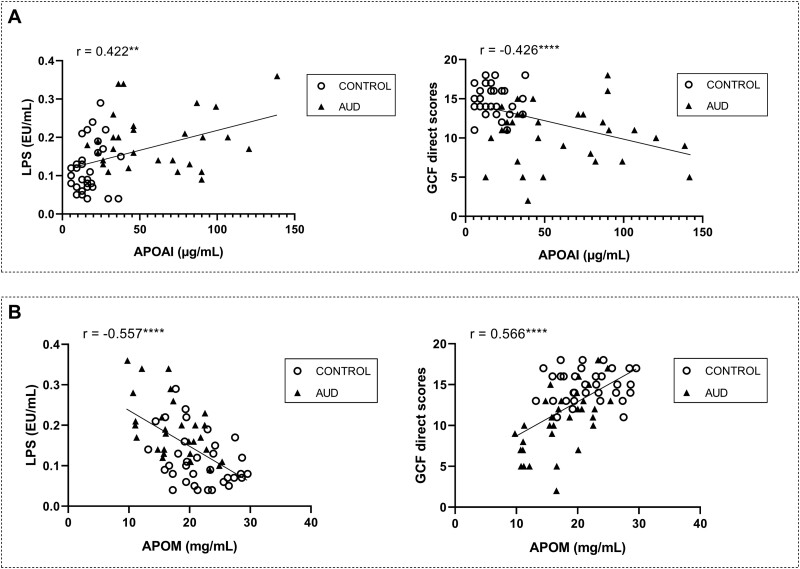

We investigated this mechanism also in the entire sample. We found that APOAI correlated positively with LPS (r = 0.422, P = .001) and negatively with cognition (r = −0.426, P = .000) in the entire sample (Figure 6A) and opposite associations were found for APOM both with LPS (negative, r = −0.426, P = .000) and cognition (positive, r = 0.566, P = .000) (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Correlations between plasma apolipoproteins APOAI/APOM with inflammation and cognition in the entire sample (alcohol use disorder [AUD] and control groups). (A) APOAI with LPS (left) and general cognitive functioning (GCF) scores (right). (B) APOM with LPS (left) and GCF scores (right). Significantly different: **P < .01; ****P < .0001.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed blood apolipoproteins and inflammatory markers in AUD patients, their association with cognitive impairment and their potential for disorder identification. We found higher LPS, APOAI, APOB, APOE, and APOJ and lower APOM plasma levels in AUD patients compared with controls, with no sexual differences. LPS and APOE correlated with impaired cognition and APOM with better performance in the AUD group, with APOM maintaining significance in hierarchical logistic models. APOAI and APOM were indicative of the disorder’s presence and absence, respectively (with a possible influence of age), and they diverged also in their associations with LPS and cognition in the entire sample. Whereas APOAI correlated positively with LPS and negatively with GCF, APOM showed the opposite trends.

Apolipoproteins and Inflammatory Markers in AUD vs Controls

We observed changes in components of high-density lipoproteins (HDL: APOAI, APOE, and APOM) and low-density lipoproteins (LDL: APOB), together with APOJ, in AUD patients during abstinence. No sexual differences were found. APOAI levels were remarkably different between the AUD and control groups (η2 = 0.44). APOCII levels were age-influenced in both groups, aligning with previous reports (Sakurabayashi et al., 2001; Muenchhoff et al., 2017). Elevated APOB levels have been described in drinkers (Yin et al., 2011), and we recently found higher APOJ levels in abstinent AUD patients (Escudero et al., 2023).

We found higher LPS plasma levels in the AUD group, as suggested by animal (Crews et al., 2013; Antón et al., 2017) and human (Bala et al., 2014; Antón et al., 2018a, 2018b; Orio et al., 2018) studies. No changes were observed in plasma LBP, a protein known for transferring or neutralizing LPS among lipoprotein subclasses (Wurfel et al., 1994; Levels et al., 2005), and no sex differences were found.

Contribution of Apolipoprotein Profile to Cognitive Decline and Identification of the Disorder

Despite initial associations between cognition and LPS, APOE (negative) and APOM (positive), hierarchical analyses revealed APOM as the only apolipoprotein inversely related with cognitive decline in the AUD group, adjusting for sex, age, and education. The role of LPS (reviewed in Brown et al., 2024) and APOE, specifically ApoE-ε4 (Kloske and Wilcock, 2020; Dilliott et al., 2021), in cognition has been documented. Our previous findings highlighted the detrimental impact of APOE4 plasma expression on memory/learning in a similar AUD cohort (Escudero et al., 2023), consistent with reports suggesting that the blood pool of some apolipoproteins (i.e., APOE, APOAI) influence cognitive performance (Lewis et al., 2010; Lane-Donovan et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2022). Interestingly, APOM was the only apolipoprotein reduced in patients, since the rest of apolipoproteins were upregulated in plasma. Although research on APOM remains limited, our results may align with studies showing low APOM levels in Alzheimer´s disease patients (Khoonsari et al., 2016; Xin et al., 2022).

Despite the significant plasma APOAI elevations in patients vs controls, with a relevant magnitude of the effect, we did not find associations with cognition in our AUD sample, being this apolipoprotein one of the most robust candidates proposed for cognition association (Kawano et al., 1995; Lefterov et a., 2010; Lewis et al., 2010).

APOAI and APOM serve as potential AUD biomarkers. Elevated plasma APOAI and decreased APOM levels would explain the presence of AUD disorder, potentially influenced by age, a covariate approaching significance in the final statistical model. Age-related effects on apolipoprotein expression were observed in very old individuals, with abnormal levels during senescence (Song et al., 2012). However, how these apolipoproteins differ with age is unclear (Muenchhoff et al., 2017), as some exhibit nonlinear, inverse trends or weak correlations with age (Song et al., 2012). The divergent roles of APOAI and APOM in AUD identification deserve further investigation.

Discussion of Possible Mechanisms

The changes in plasma apolipoprotein levels during early AUD abstinence can be discussed from various perspectives.

Firstly, plasma apolipoprotein levels might relate to alcohol consumption variables. Wilkens and colleagues found a link between total APOAI and alcohol consumption in older adults, and associations between HDL subspecies lacking or containing APOC3, APOE, or APOJ and alcohol intake (Wilkens et al., 2023). Liappas et al. (2007) found APOE serum levels correlated with alcohol consumption during the previous year of alcohol abuse. However, in our study, plasma apolipoproteins did not correlate with alcohol consumption variables.

Secondly, excessive alcohol intake induces fatty liver, enhancing lipogenesis and lipid hyperaccumulation (Osna et al., 2017). APOB and APOM are linked to fatty liver recovery or fibrosis, although APOM’s role remains controversial (Tahara et al., 1999; Hajny and Christoffersen, 2017; Chen and Hu, 2020). However, our study examines the relationship between plasma apolipoproteins, inflammation, and cognition in abstinent AUD patients without major liver disease. In our sample, AUD patients’ liver parameters were within normal ranges, and we found no associations between apolipoproteins and liver markers, suggesting that observed alterations likely did not reflect significant liver damage. Accordingly, evidence suggests higher APOAI and II in alcoholic patients without liver damage or mild steatosis compared with controls (Marth et al., 1982; Duhamel et al., 1984).

Thirly, apolipoprotein levels may be related to the inflammatory state in alcohol abuse, contributing to cognitive and emotional alterations (Orio et al., 2018; Spear, 2018). Patients with high plasma LPS had higher APOAI and lower APOM levels, and all these changes correlate with poorer cognition. These associations were significant in the entire sample, but the effect of APOAI was lost in the AUD group alone, possibly due to the limited sample size. The positive LPS-APOAI association could be related to APOAI’s ability to bind LPS and neutralize its inflammatory actions (Li, Dong and Wu, 2008). APOAI has anti-inflammatory properties during LPS-induced endotoxemia (Yan et al., 2006; Vuilleumier et al., 2013). It would be plausible to hypothesize that plasma levels of APOAI are elevated in AUD, where systemic LPS and proinflammatory environment are high, as a compensatory mechanism to mitigate LPS response. However, despite its generally accepted anti-inflammatory properties, APOAI can become dysfunctional or even proinflammatory during chronic systemic inflammation (Vuilleumier et al., 2013). We have recently demonstrated that APOAI may facilitate the transport of LPS to brain (López-Valencia et al., 2024), suggesting deleterious effects. The role of APOAI in cognition remains unclear. APOAI downregulation/deficiency has been associated with cognitive deficits (Kawano et al., 1995; Lefterov et a., 2010), whereas overexpression has been linked to preserved cognitive function (Lewis et al., 2010), contrasting with our data. However, plasma APOAI has recently been identified as a biomarker for AD diagnosis (Niu et al., 2024), so its overexpression in AUD may indicate high inflammation and cognitive deficits.

Instead, APOM maintained a significant negative correlation with LPS in both the entire sample and the AUD group alone. APOM’s anti-inflammatory properties have been described in knockout mice (Shi et al., 2020), since APOM binds LPS to facilitate its neutralization and clearance (Mousa et al., 2023). APOM is considered a negative acute response protein, with decreased serum levels observed during LPS administration in preclinical models and during infection and inflammation in humans (Feingold et al., 2008), aligning with our findings.

Interestingly, both APOM and APOAI are major components of HDL (Phillips, 2013; Hajny andChristoffersen, 2017). Alterations in HDL-associated proteins have been described in infection and inflammation contexts, suggesting a decreased ability of HDL to protect against lipid peroxidation (reviewed in Khovidhunkit et al., 2000). However, the effects of endotoxin and cytokines on lipoproteins can be both detrimental and beneficial (Hardardóttir et al., 1994).

Limitations and Conclusions

These preliminary results are limited by a small sample size, which restricts their generalizability. Confirming and strengthening these findings in a larger sample is crucial. The small sample size affects the inclusion of variables in statistical analysis, making only large differences significant. Nonetheless, we adjusted for significant (age, P < .05) or marginally significant (sex and education, P = .050 and P = .053, respectively) covariates and included significant biomarkers for the hierarchical analyses. Despite the small sample size, we found considerable effects in the expression of some apolipoproteins.

Other limitations of the study include (1) the high co-occurrence of AUD with other psychiatric disorders, so the cohort of patients in this study may not be fully representative; (2) associations between biological parameters and cognition do not imply causality, so caution may be taken in the extrapolation of results; (3) more precise liver damage evaluation using Magnetic Resonance Imaging Proton Density Fat Fraction (MRI-PDFF) instead of ultrasound or computed axial tomography (CAT) scans for exclusion criteria.

Despite these limitations, key strengths of the study include the homogeneity of sample regarding the abstinence period of recruitment, the use of comprehensive protocols for diagnosis and evaluation, and the rigorous inclusion-exclusion criteria. This study analyzes a wide spectrum of biomarkers that may have contrasting effects (i.e., anti- or pro-inflammatory actions) and controls for important confounded variables, enhancing the translational value of the findings.

Conclusions: (1) several apolipoproteins and inflammatory markers (LPS) are altered in the plasma of AUD patients during early abstinence, independent of sex; (2) key HDL components APOAI and APOM are differentially regulated in AUD patients compared with controls, playing divergent roles in disorder identification; and (3) APOM inversely correlates with inflammation and may serve as a biomarker for AUD-related cognitive impairment. Understanding these peripheral biomarkers in AUD could facilitate early diagnosis and monitorization of disease progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Ricardo Olmos for statistical support and the nurses Yolanda Guerrero Roldán, Nazaret Sáiz Briones, and Pilar de la Cruz González for their help with blood extractions.

Contributor Information

Berta Escudero, Instituto de investigación Sanitaria Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (imas12), Madrid, Spain; Department of Psychobiology and Behavioral Sciences Methods, Faculty of Psychology, Complutense University of Madrid, Pozuelo de Alarcón, Spain.

Leticia López-Valencia, Instituto de investigación Sanitaria Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (imas12), Madrid, Spain; Department of Psychobiology and Behavioral Sciences Methods, Faculty of Psychology, Complutense University of Madrid, Pozuelo de Alarcón, Spain.

Francisco Arias Horcajadas, Instituto de investigación Sanitaria Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (imas12), Madrid, Spain; Riapad: Research Network in Primary Care in Addictions, Spain.

Laura Orio, Instituto de investigación Sanitaria Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (imas12), Madrid, Spain; Department of Psychobiology and Behavioral Sciences Methods, Faculty of Psychology, Complutense University of Madrid, Pozuelo de Alarcón, Spain; Riapad: Research Network in Primary Care in Addictions, Spain.

Funding

This work was supported by FEDER (European Union) / Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MICINN), Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI), Spain (grant ref.. PID2021-127256OB-I00 and RTI2018-099535-B-I00) to L.O. B.E. and L.L.V. are recipients of predoctoral contracts FPU18/01575 and PRE2019-087771, respectively. L.O. and F.A. are members of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III RICORS-RIAPAd, Grants RD21/0009/0027 and RD21/009/0007 [European Union—NextGenerationEU; Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional FEDER; Mecanismo para la Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia (MRTR)].

Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Availability

Data in the manuscript are freely available upon request to the corresponding author (lorio@psi.ucm.es).

Author Contributions

Berta Escudero (Conceptualization [Equal], Data curation [Lead], Formal analysis [Lead], Investigation [Lead], Methodology [Equal], Writing—original draft [Equal], Writing—review and editing [Equal]), Leticia López-Valencia (Investigation [Supporting], Methodology [Supporting]), Francisco Arias (Conceptualization [Supporting], Investigation [Supporting], Methodology [Equal], Resources [Equal], Supervision [Supporting]), and Laura Orio (Conceptualization [Lead], Funding acquisition [Lead], Methodology [Supporting], Project administration [Lead], Resources [Equal], Supervision [Lead], Writing—original draft [Equal], Writing—review and editing [Lead]).

References

- Aharonovich E, Campbell ANC, Shulman M, Hu MC, Kyle T, Winhusen T, Nunes EV (2018) Neurocognitive profiling of adult treatment seekers enrolled in a clinical trial of a web-delivered intervention for substance use disorders. J Addict Med 12:99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso-Loeches S, Pascual-Lucas M, Blanco AM, Sanchez-Vera I, Guerri C (2010) Pivotal role of TLR4 receptors in alcohol-induced neuroinflammation and brain damage. J Neurosci 30:8285–8295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American PsychiatricAssociation (APA) (2014) Manual Diagnóstico Y Estadístico De Los Trastornos Mentales DSM-5. 5a. ed. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Antón M, Alén F, Gómez de Heras R, Serrano A, Pavón FJ, Leza JC, García-Bueno B, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Orio L (2017) Oleoylethanolamide prevents neuroimmune HMGB1/TLR4/NF-kB danger signaling in rat frontal cortex and depressive-like behavior induced by ethanol binge administration. Addict Biol 22:724–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antón M, Rodríguez-González A, Ballesta A, González N, Del Pozo A, de Fonseca FR, Gómez-Lus ML, Leza JC, García-Bueno B, Caso JR, Orio L (2018a) Alcohol binge disrupts the rat intestinal barrier: the partial protective role of oleoylethanolamide. Br J Pharmacol 175:4464–4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antón M, Rodríguez-González A, Rodríguez-Rojo IC, Pastor A, Correas A, Serrano A, Ballesta A, Alén F, Gómez de Heras R, de la Torre R, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Orio L (2018b) Increased plasma oleoylethanolamide and palmitoleoylethanolamide levels correlate with inflammatory changes in alcohol binge drinkers: the case of HMGB1 in women. Addict Biol 23:1242–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bala S, Marcos M, Gattu A, Catalano D, Szabo G (2014) Acute binge drinking increases serum endotoxin and bacterial DNA levels in healthy individuals. PLoS One 9:e96864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berbée JF, Havekes LM, Rensen PC (2005) Apolipoproteins modulate the inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide. J Endotoxin Res 11:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GC, Heneka MT (2024) The endotoxin hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 19:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani LW, Navab M, Van Lenten BJ, Hedrick CC, Hama SY, Goto AM, Fogelman AM, Lusis AJ (1997) Overexpression of apolipoprotein AII in transgenic mice converts high density lipoproteins to pro inflammatory particles. J Clin Invest 100:464–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HC, Ke LY, Lu HT, Weng SF, Chan HC, Law SH, Lin IL, Chang CF, Lu YH, Chen CH, Chu CS (2020) An increased plasma level of ApoCIII-rich electronegative high-density lipoprotein may contribute to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Biomedicines 8:542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Hu M (2020) The apoM-S1P axis in hepatic diseases. Clin Chim Acta 511:235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Qin L, Sheedy D, Vetreno RP, Zou J (2013) High mobility group box 1/Toll-like receptor danger signaling increases brain neuro immune activation in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry 73:602–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW (2008) From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 9:46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilliott AA, et al. ; ONDRI Investigators (2021) Association of apolipoprotein E variation with cognitive impairment across multiple neurodegenerative diagnoses. Neurobiol Aging 105:378.e1–378.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downer B, Zanjani F, Fardo DW (2014) The relationship between midlife and late life alcohol consumption, APOE e4 and the decline in learning and memory among older adults. Alcohol Alcohol 49:17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhamel G, Nalpas B, Goldstein S, Laplaud PM, Berthelot P, Chapman MJ (1984) Plasma lipoprotein and apolipoprotein profile in alcoholic patients with and without liver disease: on the relative roles of alcohol and liver injury. Hepatology 4:577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duro MV, Ebright B, Yassine HN (2022) Lipids and brain inflammation in APOE4-associated dementia. Curr Opin Lipidol 33:16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson EK, Grantham EK, Warden AS, Harris RA (2019) Neuroimmune signaling in alcohol use disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 177:34–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudero B, Moya M, López-Valencia L, Arias F, Orio L (2023) Reelin plasma levels identify cognitive decline in alcohol use disorder patients during early abstinence: the influence of APOE4 expression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 26:545–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold KR, Shigenaga JK, Chui LG, Moser A, Khovidhunkit W, Grunfeld C (2008) Infection and inflammation decrease apolipoprotein M expression. Atherosclerosis 199:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando L, Bobes J, Gibert M, Soto M, Soto O. (1998). M.I.N.I. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Versión en español 5.0.0.DSM-IV. Madrid: Instituto IAP. [Google Scholar]

- García-Marchena N, Maza-Quiroga R, Serrano A, Barrios V, Requena-Ocaña N, Suárez J, Chowen JA, Argente J, Rubio G, Torrens M, López-Gallardo M, Marco EM, Castilla-Ortega E, Santín LJ, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Pavón FJ, Araos P (2020) Abstinent patients with alcohol use disorders show an altered plasma cytokine profile: identification of both interleukin 6 and interleukin 17A as potential biomarkers of consumption and comorbid liver and pancreatic diseases. J Psychopharmacol 34:1250–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajny S, Christoffersen C (2017) A novel perspective on the ApoM-S1P axis, highlighting the metabolism of ApoM and its role in liver fibrosis and neuro inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 18:1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardardóttir I, Grünfeld C, Feingold KR (1994) Effects of endotoxin and cytokines on lipid metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol 5:207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes V, Demirkol A, Ridley N, Withall A, Draper B (2016) Alcohol-related cognitive impairment: current trends and future perspectives. Neurodegener Dis Manag 6:509–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado-Barba R, Martínez A, Sion A, Álvarez-Alonso MJ, Robles A, Quinto-Guillen R, Rubio G (2017) Development of a screening test for cognitive impairment in alcoholic population: TEDCA. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 45:201–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano M, Kawakami M, Otsuka M, Yashima H, Yaginuma T, Ueki A (1995) Marked decrease of plasma apolipoprotein AI and AII in Japanese patients with late-onset non-familial Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Chim Acta 239:209–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarzian A, Farhadi A, Forsyth CB, Rangan J, Jakate S, Shaikh M, Banan A, Fields JZ (2009) Evidence that chronic alcohol exposure promotes intestinal oxidative stress, intestinal hyperperme ability and endotoxemia prior to development of alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. J Hepatol 50:538–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoonsari PE, Häggmark A, Lönnberg M, Mikus M, Kilander L, Lannfelt L, Bergquist J, Ingelsson M, Nilsson P, Kultima K, Shevchenko G (2016) Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid proteome in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 11:e0150672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khovidhunkit W, Memon RA, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C (2000) Infection and inflammation-induced proatherogenic changes of lipoproteins. J Infect Dis 181:S462–S472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloske CM, Wilcock DM (2020) The important interface between apolipoprotein E and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Immunol 11:754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, DeKosky ST, Fitzpatrick AL, Furtado JD, Lopez OL, Kuller LH, Mackey RH, Hughes TM, Mukamal KJ, Jensen MK (2018) Apolipoproteins and Alzheimer’s pathophysiology. Alzheimers Dement (Amst,) 10:545–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane-Donovan C, Wong WM, Durakoglugil MS, Wasser CR, Jiang S, Xian X, Herz J (2016) Genetic restoration of plasma apoe improves cognition and partially restores synaptic defects in ApoE-Deficient mice. J Neurosci 36:10141–10150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq S, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Stärkel P, Jamar F, Mikolajczak M, Delzenne NM, de Timary P (2012) Role of intestinal permeability and inflammation in the biological and behavioral control of alcohol-dependent subjects. Brain Behav Immun 26:911–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq S, Matamoros S, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Jamar F, Stärkel P, Windey K, Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F, Verbeke K, de Timary P, Delzenne NM (2014) Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:E4485–E4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefterov I, Fitz NF, Cronican AA, Fogg A, Lefterov P, Kodali R, Wetzel R, Koldamova R (2010) Apolipoprotein A-I deficiency increases cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive deficits in APP/PS1ΔE9 mice. J Biol Chem 285:36945–36957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levels JH, Marquart JA, Abraham PR, van den Ende AE, Molhuizen HO, van Deventer SJ, Meijers JC (2005) Lipopolysaccharide is transferred from high-density to low-density lipoproteins by lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and phospholipid transfer protein. Infect Immun 73:2321–2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TL, Cao D, Lu H, Mans RA, Su YR, Jungbauer L, Linton MF, Fazio S, LaDu MJ, Li L (2010) Overexpression of human apolipoprotein A-I preserves cognitive function and attenuates neuroinflammation and cerebral amyloid angiopathy in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 285:36958–36968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Dong JB, Wu MP (2008) Human ApoA-I overexpression diminishes LPS-induced systemic inflammation and multiple organ damage in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 590:417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liappas IA, Nikolaou C, Michalopoulou M, Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas EO, Piperi C, Cambouri C, Soldatos CR (2007) Evaluation of apolipoprotein E (apoE) and lipoprotein profile in severe alcohol-dependent individuals. In Vivo 21:699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CC, et al. (2022) Peripheral apoE4 enhances Alzheimer’s pathology and impairs cognition by compromising cerebrovascular function. Nat Neurosci 25:1020–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Valencia L, Moya M, Escudero B, García-Bueno B, Orio L (2024) Bacterial lipopolysaccharide forms aggregates with apolipoproteins in male and female rat brains after ethanol binges. J Lipid Res 65:100509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marth E, Cazzolato G, Bittolo Bon G, Avogaro P, Kostner GM (1982) Serum concentrations of Lp(a) and other lipoprotein parameters in heavy alcohol consumers. Ann Nutr Metab 26:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousa H, Thanassoulas A, Zughaier SM (2023) ApoM binds endotoxin contributing to neutralization and clearance by High Density Lipoprotein. BiocheBiophys Rep 34:101445–101445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenchhoff J, Song F, Poljak A, Crawford JD, Mather KA, Kochan NA, Yang Z, Trollor JN, Reppermund S, Maston K, Theobald A, Kirchner-Adelhardt S, Kwok JB, Richmond RL, McEvoy M, Attia J, Schofield PW, Brodaty H, Sachdev PS (2017) Plasma apolipoproteins and physical and cognitive health in very old individuals. Neurobiol Aging 55:49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu X, Wang Y, Zhang X, Wang Y, Shao W, Chen L, Yang Z, Peng D (2024) Quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG), apolipoprotein A-I (APOA-I), and apolipoprotein epsilon 4 (APOE ɛ4) alleles for the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Sci 45:547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opal SM, Scannon PJ, Vincent JL, White M, Carroll SF, Palardy JE, Parejo NA, Pribble JP, Lemke JH (1999) Relationship between plasma levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS-binding protein in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. J Infect Dis 180:1584–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orio L, Antón M, Rodríguez-Rojo IC, Correas A, García-Bueno B, Corral M, de Fonseca FR, García-Moreno LM, Maestú F, Cadaveira F (2018) Young alcohol binge drinkers have elevated blood endotoxin, peripheral inflammation and low cortisol levels: neuropsychological correlations in women. Addict Biol 23:1130–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orio L, Alen F, Pavón FJ, Serrano A, García-Bueno B (2019) Oleoylethanolamide, neuroinflammation, and alcohol abuse. Front Mol Neurosci 11:490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orio L, López-Valencia L, Escudero B, Moya M, García-Bueno B (2023) Can bacterial products reach the brain after alcohol binge drinking? Alcohol 109:102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Osna NA, Donohue TM Jr, Kharbanda KK (2017) Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and current management. Alcohol Res 38:147–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parhizkar S, Holtzman DM (2022) APOE mediated neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Semin Immunol 59:101594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual M, Baliño P, Alfonso-Loeches S, Aragón CM, Guerri C (2011) Impact of TLR4 on behavioral and cognitive dysfunctions associated with alcohol-induced neuroinflammatory damage. Brain Behav Immun 25:S80–S91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual M, Pla A, Miñarro J, Guerri C (2014) Neuroimmune activation and myelin changes in adolescent rats exposed to high-dose alcohol and associated cognitive dysfunction: a review with reference to human adolescent drinking. Alcohol Alcohol 49:187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CJ (2016) Cognitive decline and recovery in alcohol abuse. J Mol Neurosci 60:383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MC (2013) New insights into the determination of HDL structure by apolipoproteins: thematic review series: high density lipoprotein structure, function, and metabolism. J Lipid Res 54:2034–2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, He J, Hanes RN, Pluzarev O, Hong JS, Crews FT (2008) Increased systemic and brain cytokine production and neuroinflammation by endotoxin following ethanol treatment. J Neuroinflammation 5:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A, Joshi RS, Szabo G (2022) Innate immune activation: parallels in alcohol use disorder and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Mol Neurosci 15:910298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Requena-Ocaña N, Flores-Lopez M, Papaseit E, García-Marchena N, Ruiz JJ, Ortega-Pinazo J, Serrano A, Pavón-Morón FJ, Farré M, Suarez J, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Araos P (2022) Vascular endothelial growth factor as a potential biomarker of Neuroinflammation and frontal cognitive impairment in patients with alcohol use disorder. Biomedicines 10:947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CA, Gatz M, Prince JA, Berg S, Pedersen NL (2010) Serum lipid levels and cognitive change in late life. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:501–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez A, Orio L (2020) Microbiota and alcohol use disorder: are psychobiotics a novel therapeutic strategy? Curr Pharm Des 26:2426–2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romagnoli T, Ortolani B, Sanz JM, Trentini A, Seripa D, Nora ED, Capatti E, Cervellati C, Passaro A, Zuliani G, Brombo G (2021) Serum Apo J as a potential marker of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia. J Neurol Sci 427:117537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurabayashi I, Saito Y, Kita T, Matsuzawa Y, Goto Y (2001) Reference intervals for serum apolipoproteins A-I, A-II, B, C-II, C-III, and E in healthy Japanese determined with a commercial immunoturbidimetric assay and effects of sex, age, smoking, drinking, and Lp(a) level. Clin Chim Acta 312:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayd A, Antón M, Alén F, Caso JR, Pavón J, Leza JC, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, García-Bueno B, Orio L (2015) Systemic administration of oleoylethanolamide protects from neuroinflammation and anhedonia induced by LPS in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 18:pyu111–pyu111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Liu H, Liu H, Yu Y, Zhang J, Li Y, Luo G, Zhang X, Xu N (2020) Increased expression levels of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute inflammatory apoM-/- mice. Mol Med Rep 22:3117–3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slayday RE, Gustavson DE, Elman JA, Beck A, McEvoy LK, Tu XM, Fang B, Hauger RL, Lyons MJ, McKenzie RE, Sanderson-Cimino ME, Xian H, Kremen WS, Franz CE (2021) Interaction between alcohol consumption and Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype with cognition in middle-aged men. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 27:56–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoak KA, Aloor JJ, Madenspacher J, Merrick BA, Collins JB, Zhu X, Cavigiolio G, Oda MN, Parks JS, Fessler MB (2010) Myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 couples reverse cholesterol transport to inflammation. Cell Metab 11:493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song F, Poljak A, Crawford J, Kochan NA, Wen W, Cameron B, Lux O, Brodaty H, Mather K, Smythe GA, Sachdev PS (2012) Plasma apolipoprotein levels are associated with cognitive status and decline in a community cohort of older individuals. PLoS One 7:e34078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP (2018) Effects of adolescent alcohol consumption on the brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 19:197–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara M, Matsumoto K, Nukiwa T, Nakamura T (1999) Hepatocyte growth factor leads to recovery from alcohol-induced fatty liver in rats. J Clin Invest 103:313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visontay R, Rao RT, Mewton L (2021) Alcohol use and dementia: new research directions. Curr Opin Psychiatry 34:165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier N, Dayer JM, von Eckardstein A, Roux-Lombard P (2013) Pro- or anti-inflammatory role of apolipoprotein A-1 in high-density lipoproteins? Swiss Med Wkly 143:w13781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens TL, Sørensen H, Jensen MK, Furtado JD, Dragsted LO, Mukamal KJ (2023) Associations between alcohol consumption and HDL subspecies defined by ApoC3, ApoE and ApoJ: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Curr Probl Cardiol 48:101395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurfel MM, Kunitake ST, Lichenstein H, Kane JP, Wright SD (1994) Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein is carried on lipoproteins and acts as a cofactor in the neutralization of LPS. J Exp Med 180:1025–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin JY, Huang X, Sun Y, Jiang HS, Fan J, Yu NW, Guo FQ, Ye F, Xiao J, Le WD, Yang SJ, Xiang Y (2022) Association Between Plasma Apolipoprotein M With Alzheimer’s Disease: a Cross-Sectional Pilot Study from China. Front Aging Neurosci 14:838223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YJ, Li Y, Lou B, Wu MP (2006) Beneficial effects of ApoA-I on LPS-induced acute lung injury and endotoxemia in mice. Life Sci 79:210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin RX, Li YY, Liu WY, Zhang L, Wu JZ (2011) Interactions of the apolipoprotein A5 gene polymorphisms and alcohol consumption on serum lipid levels. PLoS One 6:e17954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuin M, Cervellati C, Trentini A, Passaro A, Rosta V, Zimetti F, Zuliani G (2021) Association between Serum Concentrations of Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I) and Alzheimer’s Disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 11:984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data in the manuscript are freely available upon request to the corresponding author (lorio@psi.ucm.es).