Abstract

Background

Societal attitudes about end-of-life events are at odds with how, where, and when children die. In addition, parents’ ideas about what constitutes a “good death” in a pediatric intensive care unit vary widely.

Objective

To synthesize parents’ perspectives on end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit in order to define the characteristics of a good death in this setting from the perspectives of parents.

Methods

A concept analysis was conducted of parents’ views of a good death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Empirical studies of parents who had experienced their child’s death in the inpatient setting were identified through database searches.

Results

The concept analysis allowed the definition of antecedents, attributes, and consequences of a good death. Empirical referents and exemplar cases of care of a dying child in the pediatric intensive care unit serve to further operationalize the concept.

Conclusions

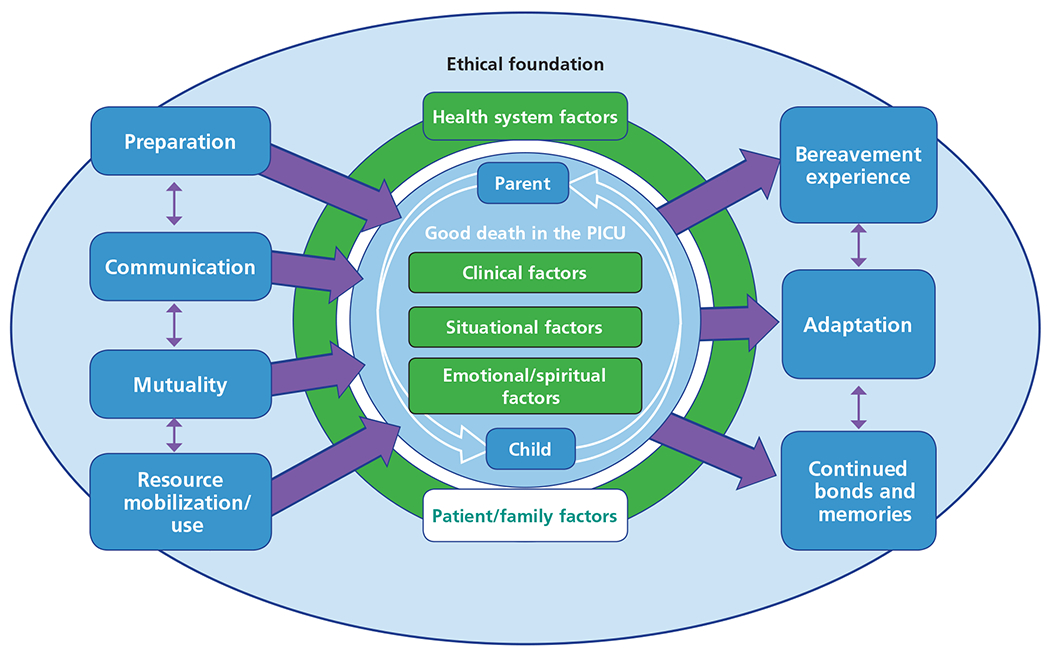

Conceptual knowledge of what constitutes a good death from a parent’s perspective may allow pediatric nurses to care for dying children in a way that promotes parents’ coping with bereavement and continued bonds and memories of the deceased child.The proposed conceptual model synthesizes characteristics of a good death into actionable attributes to guide bedside nursing care of the dying child.

Without doubt, the death of a child is a devastating event. Although pediatric mortality rates are low, most of these deaths in the developed world occur in pediatric intensive care units (PICUs).1–6 A child’s death can result from acute illness, chronic illness, or traumatic injury. Sudden or traumatic deaths require clinicians’ close attention to fast-evolving clinical symptoms as well as acknowledgment of families in crisis.7 Families of children with chronic, life-limiting illnesses live with the possibility of fatality for prolonged periods. These patients and their families build relationships with the health care team and have an opportunity to receive palliative care, yet this service remains underused in the PICU setting.7–9

The ability to achieve a meaningful death lies in the details of the experience. Most pediatric deaths follow a decision to limit or withdraw life-sustaining treatment, with a smaller number resulting from failed resuscitation or brain death.2–6,10 Limitation and/or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment often follows a prolonged hospital stay and a series of family meetings.10 Death typically occurs within a few hours after treatment withdrawal.10 What happens in the final hours of a child’s life encompasses a spectrum of unique experiences that require an individualized approach to bedside nursing care. Creating a “good death” experience that frames the end-of-life period in a way that builds memories and honors families’ ongoing love and connections is both possible and rewarding. The concept of a “good death” has gained attention and has been well explored in the literature on adult patients,11 but a critical gap remains in understanding the unique needs of pediatric patients and their families.

Pediatric nursing includes multidimensional caring for both the patient and the patient’s individually defined family, which may include parents, siblings, extended family, friends, and significant others. Nurses provide end-of-life care within these established therapeutic relationships with patients and their families and are afforded an unparalleled opportunity to facilitate a good death experience,12 including minimizing pain and other noxious symptoms and creating a caring environment for the dying child and the family. Relationship-centered care is particularly poignant during the family’s last moments with a child.

The concept of a good death, as defined by parents themselves, remains unexplored in the literature. Studies of parents’ perceptions of care at the end of their child’s life lend themselves to developing clear notions of what does and does not constitute a good death experience in the PICU. The objective of this article is to define a “good death” in the PICU from parents’ perspectives. Such a definition may provide insight to guide best practices in the care of dying children in the PICU.

Methods

Concept Analysis

This article uses Walker and Avant’s method of concept analysis.13 The process includes the following 8 steps: (1) select a concept; (2) determine aims/purposes of analysis; (3) identify uses of the concept; (4) determine defining attributes; (5) construct a model case; (6) construct borderline, related, and contrary cases; (7) identify antecedents and consequences; (8) define empirical referents. The concept of a good death in the PICU for the dying child was initially selected. The aim of the concept analysis was to define what constitutes a good death for the dying patient in the PICU from the perspective of parents.

Literature Search

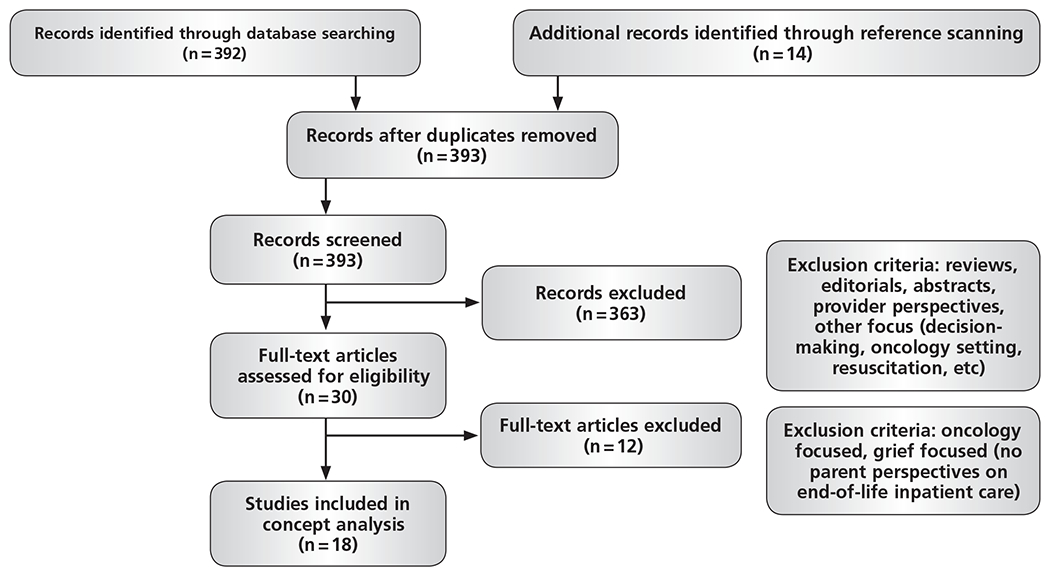

In order to identify uses of the concept of a good death in the PICU for a dying child, the first author (E.G.B.) undertook a literature search. Article searches were conducted in PubMed and CINAHL to identify nursing research on perspectives on end-of-life care. Studies about sociocultural perspectives on death were gathered from Google Scholar and PubMed. The searches focused on full-text, peer-reviewed, English-language articles published from 1998 to 2018. Combinations of several search terms were used. The terms end of life care, terminal care, and good death were used to obtain general perspectives on end of life. The terms pediatric intensive care, parent, and parent perspective were added to gather bereaved parents’ perspectives on their child’s end-of-life care. Abstracts, case narratives, and articles about euthanasia or assisted suicide were excluded. References of retained full-text articles were also searched (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) search strategy diagram.

Results

We classified uses of the concept of a good death into 2 categories: sociocultural perspectives on death and parents’ perspectives on end-of-life care.

Sociocultural Perspectives on Death

In Western culture, death has become medicalized, with more than half of all deaths occurring in hospitals, nursing homes, or other medical facilities.1,14 Because of advances in health care and the pervasiveness of technology, death often follows a delicate balance between prolonging life-sustaining interventions and allowing the end of life to occur.14,15

The former Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) defined a good death as “one that is free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers; in general accord with patients’ and families’ wishes; and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards.”16(p24) The assumptions underlying many of these traits, however, is that death follows a full and complete life.

How death is perceived within a society is culturally constructed and may vary according to a variety of factors.14 The globalization of society has led to multicultural populations with various perspectives and needs at the end of life, including different communication and language practices, decisionmaking styles, and information preferences.14,17 Despite an emphasis on the persistence of autonomy and increased conversation about end-of-life wishes and advance directives, these options remain inconsistently used in inpatient care.14,18,19

Common themes regarding a “good death,” “dignified death,” and “dying well” for an adult include lack of physical suffering, respecting the patient’s wishes, and a sense of completion of life.11,15,20–24 Bereaved family members and patients with terminal illnesses express a need for clear communication, pain and symptom management, and logistic, emotional, and spiritual preparation for death.22 Some authors describe a dignified death as a death free of interventions such as hospital codes or cardiopulmonary resuscitation.15

Some conclusions drawn from this body of work, particularly the ability to achieve a sense of closure or completion and a desire to minimize the use of technological interventions, may not be as readily applicable or desirable in the death of a child.15,22 Many of these conclusions hinge on the assumption that the dying person is an adult who has lived a complete life and whose wishes are well established. This is not likely true in the pediatric population, which has historically been excluded from these types of studies. Further discussion is warranted regarding how best to achieve a good death for a child in the PICU.25

Parents’ Perspectives on End-of-Life Care

The death of a child adds complexity to notions of dying well, but the idea of a good death for a child is a burgeoning topic in the literature.25 Central to the concept of a good death for a child is the overarching theme of being a good parent—that is, doing what is best for the child and ensuring that he or she feels loved, especially at the end of life.26,27 The parent-child relationship is central to parents’ perceptions of their child’s end-of-life care.27,28 Because the idea of being a “good parent” is highly subjective, the child’s well-being is situated within multiple levels of individual, social, and cultural influences on parents and clinicians. The relationship between parent and nurse, in particular, contributes significantly to the critically ill child’s care in the PICU. A relationship characterized by mutuality, in which nurses and parents contribute synergistically to patient care, is key.29 Mutuality allows nurses to develop an intimate understanding of the individualized needs of patients and families. Mutuality benefits both parent and nurse by facilitating reciprocal trust and role satisfaction in the shared goal of promoting the critically ill child’s well-being.29

It is essential to establish an ethical framework in which the child, the parents, and the interprofessional team continuously identify and discuss shared goals of care within the context of sociocultural and familial preferences.29,30 Providing care to pediatric patients at the end of life is fraught with complicated and ethically challenging decisions. It may be difficult for clinicians to know which ethical principles (eg, autonomy, beneficence/maleficence, justice) to prioritize or how to consider and weigh input from all relevant parties in making end-of-life decisions.31 Parents, too, are stressed in trying to make decisions that balance easing the suffering of their child and potentially hastening death.26,27,31 Moreover, goals of care may be unclear because of lack of information disclosure, and parents and clinicians may simply not know what “the right thing to do” is in the given situation.26,27,30,31 With many variations of the outcomes of such decisions, ideally the health care team should inform, support, and counsel families throughout and following their child’s death. The interprofessional health care team can problem-solve as necessary using ethics consultations and family meetings when possible. The parent-child relationship and an ethical framework thereby underlie all aspects of the concept of a good death in the PICU.

Because of the profound and enduring nature of parents’ grief, integrating their perspectives into the definition of a good death in the PICU is imperative. Beyond foundational aspects of end-of-life care, including the parent-child relationship and an ethical basis for working with grieving families, several factors emerge as key attributes of a good death in the PICU. The issues parents cite as most important while their child is dying in the PICU can be classified into 3 categories: clinical, situational, and emotional and/or spiritual factors.

Clinical Factors.

Clinical factors include compassionate staff attitudes, accessible communication, and optimal bedside care. Compassion may manifest as thoughtful gestures and genuine emotional responses to the death of the child, as well as a sense of engagement with the child’s life and personhood.32–37 Reminders of the child’s likes and dislikes and continued dialogue with the child are especially helpful when a child is sedated and ventilated or otherwise nonverbal.34–38 Parents value honest information free of medical jargon, with repetition as necessary.32,38–40 The sheer number of staff members involved in PICU settings creates challenges in communication and can add burden to an already challenging time.33,34 Parents have described the difficulties associated with gathering and interpreting information from multiple providers.32,41 Parents feel relief when they perceive that the care provided to their dying child is thorough, values the child’s humanity, and ensures his or her comfort.42,43 Having a sense that a team is working with parents toward the ultimate shared goal of attentive and loving care for the dying child is a source of comfort for parents.

Situational Factors.

Typically, the main focus in the PICU is saving lives through the most intensive means available. These means, including interventions such as invasive monitoring, central vascular access, and mechanical ventilation, and drastic changes in physical appearance contribute to a stressful setting in which to be a parent, especially the parent of a child who is dying.44 Environmental considerations, such as proximity to and physical connection with the child, are a critical component of the parent-child relationship, and parents often want the option to be present during end-of-life care.35,36,44–47 Pragmatic supports, such as space and time, are needed to allow parents to remain at the bedside to the extent desired.34,48 Processes in the PICU can be modified to maintain the parental role, such as by including parents in bedside rounds and physical care.32,33,38,47 The constant observation and monitoring necessary for intensive care also interrupts the parent-child relationship. Parents who are not afforded the time or space to be alone with their child before, during, or after the death may feel unable to freely express acute grief reactions during their last moments with their child.38,46 Creating an environment that reflects the significance of the child’s life and death through strategies such as dimming lights, silencing monitors, and allowing privacy can benefit the grieving family.34,45,48

Emotional and/or Spiritual Factors.

The child’s death affects all domains of parents’ well-being, including biopsychosocial dimensions.28,49,50 The death of a child substantially alters parents’ identity, daily life, and relationships. Allocating time to identify and attempt to accommodate families’ individualized needs for support is complex and requires an unassuming team approach.51 Supportive care can be tailored to each family’s unique needs by asking open-ended questions and explaining the roles of various resources such as social workers, child life services, ethics consultation services, and chaplains.

Parents and children seek emotional support from a spectrum of sources, including friends, family, and the hospital staff.39,47 Compassion—demonstrated through body language, caring presence, and emotional expression—helps express humanity and foster a therapeutic connection between the family and the health care team.32,52,53 Nurses can serve as liaisons to help connect parents with hospital resources to meet their spiritual and emotional needs.52,54 Most parents who are offered consultation with a spiritual leader during their child’s final PICU stay feel that this was beneficial, and access to community clergy with whom the parents have an established relationship can prove especially meaningful.39,54 Emotional support is also provided through practical assistance, including referrals to resources to help with the logistic aspects of death, such as notifying family members and assisting with funeral arrangements.51,52

Determining Defining Attributes

After exploring uses of the concept of a good death, we sought to determine key attributes, or defining characteristics. To accomplish this, the first author (E.G.B.) compiled lists of frequently mentioned and highly relevant attributes from the literature and then sorted these attributes into distinct categories. The categories, as mentioned above, consisted of clinical, situational, and emotional and/or spiritual aspects. The key attributes of a good death in the PICU as derived from this analysis are addressed in the following paragraphs.

Clinical.

A good death in the PICU involves optimal clinical care, including compassionate and trustworthy staff members who communicate in an accessible and honest way to provide care that accounts for the child’s value as a person, ensure that the child is free of pain and suffering, and verify that all practical treatment options have been exhausted.

Situational.

A good death in the PICU occurs in an environment in which parents’ and families’ practical needs are met, parent-child connections are facilitated, and time and effort are dedicated to creating space and memories that reflect the significance of the child’s life and death.

Emotional and/or Spiritual.

A good death in the PICU encompasses the emotional and spiritual needs of children and their families, including support and guidance from various sources for restructuring family roles and recognition of individualized familial needs.

Exemplar Cases

To further illustrate what does and does not constitute the concept, exemplar cases are presented in Table 1.13 The model case contains the attributes of the concept, thus providing an exemplar of how a good death in the PICU might proceed.13 Borderline, related, and contrary cases are described to further distinguish the defining attributes of the concept.

Table 1.

Exemplar cases: model case, borderline case, related case, and contrary case

| Type of case | Case description | Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Model (contains all key attributes of the concept) | Michelle, 9, was in the PICU for the fourth time this year, as was typical for her. Michelle had spinal muscular atrophy, and as her condition progressed, her parents, Roger and Kathy, and the health care team had frequent discussions about care preferences and prognosis. Over the course of this hospitalization, Michelle experienced worsening respiratory distress despite increased ventilator settings. Her physical function had declined to the point that she would require permanent ventilation, along with complete technological dependence. After a series of team meetings, Michelle’s parents and providers decided it was best to withdraw life-sustaining treatments to prevent prolonged suffering. The primary nurse, Suzanne, and charge nurse, Matt, worked together with Roger and Kathy to create a plan that incorporated their wishes. A CD with Michelle’s favorite music was made, and a priest from their local church performed last rites. The nurses obtained food vouchers from social workers and discussed with Roger and Kathy what sounds and sights to expect during the dying process. The nurses helped Kathy and Roger contact relatives and friends close to Michelle. Suzanne administered pain medications and solicited Kathy and Roger’s input as to whether they thought Michelle seemed comfortable. Michelle was positioned so that her mother could lie in the bed beside her, and her father sat in a large chair next to the bed, holding his wife’s and daughter’s hands. Suzanne gave Kathy some tissues after wiping a tear away from her own eye. After the ventilator was disconnected, the nurses silenced the monitors, dimmed the overhead lights, and closed the door. Suzanne sat vigil outside the room watching the vital signs on a remote monitor. When the clinical team returned to the room to pronounce the death, the group said a prayer, and the parents were given private time with Michelle. After time had passed, a hospital chaplain gave Roger and Kathy resources about local grief support groups as well as morticians to contact later, and a book about grief and loss. The nurses asked Roger and Kathy for contact information to connect them with hospital bereavement programs, as well as to send a card from the unit staff. | A good death was achieved in this case. As Roger and Kathy had been to the PICU multiple times, rapport had been established among the team and family, and a series of team/family meetings facilitated ethical concordance. Suzanne and Matt formed a bond with Roger and Kathy and incorporated their input into Michelle’s care management, helping them to retain desired aspects of their parental role. Further, the nurses worked closely with the parents and health care team to create a favorable death context while preparing Roger and Kathy, and used hospital resources to enable a peaceful end-of-life experience on a spiritual and situational level. Suzanne’s tearful yet reserved reaction to Michelle’s death validated her humanity and compassion, and the promise of follow-up contact demonstrated empathetic care as well. The realization of all these elements simultaneously fostered a good death in the PICU for Michelle. |

| Borderline (contains some but not all key attributes of the concept) | Kelly is taking care of a long-term PICU patient with a diagnosis of metastasized neuroblastoma for whom a planned withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment is scheduled this afternoon. She calls a chaplain to the room, and staff members from throughout the unit stop by the patient’s room to say a last goodbye. After she shares a close moment with the patient and family and ensures that pain medications have been effective, Kelly steps out of the room as the patient is weaned off of mechanical ventilation. The patient’s mother calls for Kelly, distraught from hearing her son’s rattled breathing. Following the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, Kelly quickly and stoically gathers supplies for postmortem care. She keeps the supplies just outside the room. However, the parents and other family have not yet left the patient care area and see these supplies. When asked what they are, Kelly does not know what to say. | This would constitute a borderline case, as situational factors have not been met. Though Kelly was helpful in mobilizing supports for the psychosocial elements of the death, she did not prepare the mother for the sights and sounds of the dying process. Further, the family was not granted time, privacy, or emotional space for acute grief responses; thus a key element of a good death is lacking. |

| Related (contains elements that resemble key attributes but that differ upon close examination) | A family that recently immigrated from Turkey is making decisions about their son’s life support. They do not speak English, and the hospital’s interpreter has limited availability. Although a family meeting is scheduled, the patient codes before the meeting. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation is initiated while his extended family is rushed out of the room. His parents stand a few feet from the bedside while the child is successfully resuscitated. At the family meeting the following afternoon, the parents are very concerned about why their family was removed from his bedside. Although the interprofessional team addresses this concern, other cultural and religious considerations are not discussed. When the patient dies, the family’s religious practices, including active prayer rituals, are not accommodated by the interprofessional staff. | Despite attempts to communicate and provide care in a compassionate way, key attributes of a good death were more challenging to actualize because of language and cultural barriers. It is important to use psychosocial care providers, such as interpreters, social workers, child life specialists, and chaplains to try to conduct a comprehensive assessment of families’ needs during their child’s death. |

| Contrary (lacks any key attributes of the concept) | A family of a child who has never been hospitalized experiences a traumatic accident. The interprofessional staff works diligently to resuscitate the child and medically manage her care. She becomes very swollen and has many medical devices. She has bruises from multiple venipunctures and an intraosseous catheter. Her chest is bruised from compressions. Her face appears to be in a constant grimace, and she cannot move because of paralytic medications used to maintain her intubation status. The clinical team and parents are aware of her fatal prognosis. Nurses, respiratory therapists, and physicians come in and out of the room every few minutes to document and assess her status. Few acknowledge the parents, who sit quietly and occasionally hold their daughter’s hand. When she dies, a nurse and a physician are in the room, silently documenting at separate computers. | No ethical framework was established for working with parents of children who are seriously or critically ill. Further, the team failed to consider the parent-child relationship or psycho-social needs. Thus, the key attributes of a good death in the PICU became difficult to achieve. The parents were not prepared for the sights and sounds of the PICU or their child’s appearance. Care of the dying child was managed solely on the basis of clinicians’ input without a holistic care management plan. From a clinical/staff standpoint, suboptimal pain and symptom management adversely affected parents’ perceptions of care at the end of life. The clinical staff seemed rushed and did not emotionally acknowledge the gravity of the family’s scenario, thereby disenfranchising their suffering and failing to achieve mutuality. Failure to meet situational needs, for example, by intruding upon a family’s privacy during and after the death, may have stifled immediate emotional grief responses. Without the actualization of the key attributes of a good death, including clinical, situational, and emotional factors, parents’ and consequently families’ bereavement process and adaptation may suffer in the long term. |

Abbreviation: PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

Antecedents

The parent perspectives and exemplar cases suggest necessary conditions—termed antecedents in concept analysis—that must be met in order to achieve a good death in the PICU.13 These antecedents are preparation, mutuality, communication, and resource mobilization or use. Although there are bidirectional relationships between the antecedents, each can be defined independently. Preparation is the ongoing process of updating parents about what to expect before, during, and after the dying process. How much a parent wants to know about his or her child’s clinical presentation is highly variable. Therefore, parents’ goals and intimate knowledge of their child must be incorporated into the plan of care before the active dying phase.29 Mutuality is an important precept for a good death because it involves respecting and taking into account the preferences and goals of parents during extremely challenging circumstances in their lives. Mutuality is defined as a relationship between nurse and parent in which each individual provides unique, synchronous input for the benefit of the child.29 Mutuality is aided by effective communication. The amount and clarity of information communicated to parents are critical to their experience through all stages of end-of-life care.34,40,41 Sharing information that fosters questions, is understandable to parents, and includes repetition as needed is important. On the other hand, there may be times when parents request no further discussion of end-of-life issues. The trajectory of illness and precipitating circumstances may affect a good death for the dying child in the PICU. Efforts by diverse professionals to support the multifaceted needs of dying children and their parents allows optimization of care in each of the domains of a good death.

Consequences

In Walker and Avant’s method of concept analysis, the outcomes of the concept are termed consequences.13 Parents’ bereavement experience depends on the key attributes of a good death. In psychosocial science, bereavement or grief has been conceptualized as a nonlinear progression through unstructured stages, including reaction, reconstruction, and reorientation.55,56 For parents in particular, this process may involve coping with acute and long-standing grief, restructuring their own identities and partnership, and reexamining relationships, including with their deceased child, other family members, and their social network.28,55–58 The nature of grief is not straight-forward. Those who grieve often oscillate between coping with and avoiding feelings of grief.59 As parents continue to make meaning of the death by reliving its circumstances, clinical and situational aspects of the care their child received, such as pain management and staff compassion, become particularly pertinent. Adaptation in this case is the ability to reconstruct the life narrative to incorporate the loss and to continue to meet life’s requirements, such as parenting, working, and self-care.56 This process allows for continued bonds and memories, in which parents remember and treasure the time they spent with their deceased child. Spiritually and emotionally engaging with families to create memories of the child’s life and death through tangible mementos, such as handprints, hospital bracelets, and photographs, can help validate the ongoing connections with the deceased child.37,48,58 In facilitating the bereavement process, adaptation, and continued bonds of parents, the key attributes of a good death support the well-being of the family as well.

Patient and/or family and systems factors may affect the ability to achieve a good death in the PICU. The illness trajectory—that is, sudden or acute versus chronic or progressive—has considerable implications for the antecedents of a good death. For families of children with life-limiting illnesses, the prospect of death has permeated their lives for years; thus the death is characteristically different from a death that follows a more sudden or acute diagnosis.8 The various perspectives and experiences of families of dying children should inform the interprofessional team’s provision of end-of-life care to families. Considerations on the parent or family level such as family dynamics and previous experience with death, health literacy, demographics, and language barriers may interfere with the ability to facilitate a good death.60,61 Hospital- and PICU-level factors beyond the individual patient’s environment such as nurse staffing ratio, unit acuity, available resources, staff support, and clinician education most likely have an impact as well.62 A conceptual model relating these factors, antecedents, and consequences to the attributes of a good death in the PICU is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of relationship of antecedents and consequences to attributes of a good death in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

Empirical Referents

The final step in concept analysis involves defining the empirical referents, or ways in which the concept under study is operationalized within research.13 Studies of the end of life in the PICU have used a variety of methods, both qualitative and quantitative, each with unique benefits and disadvantages. Examples of empirical referents are summarized in Table 2. Future research investigating care of dying PICU patients should comprehensively describe and measure nursing care processes, including assessment, documentation, and interventions undertaken during the period of active dying.

Table 2.

Empirical referents: how studies of end of life in the pediatric intensive care unit have operationalized the concept of a “good death”

| Type of technique | Experience of end-of-life care | Quality of end-of-life care | Outcomes of end-of-life care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Interviews | Interviews, parent participation in instrument development | Interviews, open-ended surveys |

| Qualitative | Surveys | Standardized instruments | Standardized measures of depression, anxiety, grief or complicated grief, coping |

Discussion

Parents who suffer the loss of a child experience unique, long-standing, and multifaceted grief.58 This concept analysis derived the key attributes of a good death in the PICU from parents’ perspectives using existing data from qualitative and quantitative studies. A supportive environment built on ethical concordance and centered around the parent-child relationship can foster compassionate caregiving to achieve the characteristics of a good death. Antecedents of a good death in the PICU include communication, preparation, mutuality, and resource mobilization.

A good death in the PICU influences the bereavement process, adaptation, and continued bonds and memories, which may evolve over time in keeping with the oscillatory nature of grief.59 A good death in the PICU is therefore defined as one in which the dying child receives optimal clinical care from a compassionate, respectful, and communicative multidisciplinary staff, and patient and family situational and psychosocial-spiritual needs are identified and met. These antecedents, attributes, and consequences are contextually dependent on other influencing factors, such as patient and family factors, as well as health systems factors.

This concept analysis was limited in a few key ways. First, the literature review was conducted by a single reviewer (E.G.B.), but with consensus from all the other authors. Second, given that the search was limited to nursing literature, relevant publications outside of the field may not have been included. Finally, the conceptual model itself requires validation in future research.

As parents strive to make meaning of their loss, they will replay the circumstances surrounding their child’s death throughout their lifetime. Pediatric nurses play a critical role in promoting parents’ transition to their individualized grief processes. Bedside nurses should therefore be attuned to the clinical, situational, and emotional and/or spiritual needs of their patients and families during the end-of-life period. Acknowledging facilitators and barriers related to high-quality end-of-life care is important in improving PICU nursing practice at the end of life.62,63 Staffing models should account for the emotional involvement, time, and attention required to care for dying children and their families.63 Additionally, nurses should be aware of resources available to support parents’ needs, as well as their own. Mentorship for new nurses and bereavement support for clinicians and families are also necessary to improve care for dying children.63 Regardless of illness trajectory, all children who die in the PICU deserve well-planned, compassionate nursing care that facilitates a good death experience for the child and family.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was performed at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

Ms Broden is supported by the Rita and Alex Hillman Foundation.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth G. Broden, doctoral student, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, and a registered nurse, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Janet Deatrick, professor emerita, Department of Family and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

Connie Ulrich, professor, Department of Biobehavioral Health, School of Nursing, and a professor of bioethics, School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Martha A.Q. Curley, Ruth M. Colket Endowed Chair in Pediatric Nursing, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and a professor, Department of Family and Community Health, School of Nursing and Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying cause of death, 1999-2017. CDC WONDER online database. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Accessed July 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns JP, Sellers DE, Meyer EC, Lewis-Newby M, Truog RD. Epidemiology of death in the PICU at five U.S. teaching hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(9):2101–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meert KL, Keele L, Morrison W, et al. End-of-life practices among tertiary care pediatric intensive care units in the United States: a multicenter study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(7):e231–e238. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kipper DJ, Piva JP, Garcia PC, et al. Evolution of the medical practices and modes of death on pediatric intensive care units in southern Brazil. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(3):258–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sands R, Manning JC, Vyas H, Rashid A. Characteristics of deaths in paediatric intensive care: a 10-year study. Nurs Crit Care. 2009;14(5):235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stark Z, Hynson J, Forrester M. Discussing withholding and withdrawing of life-sustaining medical treatment in paediatric inpatients: audit of current practice. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44(7-8):399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Truog RD, Christ G, Browning DM, Meyer EC. Sudden traumatic death in children: “We did everything, but your child didn’t survive.” JAMA. 2006;295(22):2646–2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mooney-Doyle K, Deatrick JA. Parenting in the face of childhood life-threatening conditions: the ordinary in the context of the extraordinary. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(3):187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutmer JE, Humphrey L, Kempton TM, Moore-Clingenpeel M, Ayad O. Screening criteria improve access to palliative care in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(8):e335–e342. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oberender F, Tibballs J. Withdrawal of life-support in paediatric intensive care—a study of time intervals between discussion, decision and death. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier EA, Gallegos JV, Montross-Thomas LP, Depp CA, Irwin SA, Jeste DV. Defining a good death (successful dying): literature review and a call for research and public dialogue. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(4):261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bloomer MJ, Endacott R, Copnell B, O’Connor M. ‘Something normal in a very, very abnormal environment’—nursing work to honour the life of dying infants and children in neonatal and paediatric intensive care in Australia. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2016;33:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker L, Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walter T. Historical and cultural variants on the good death. BMJ. 2003;327(7408):218–220.12881270 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardozo M. What is a good death? Issues to examine in critical care. Br J Nurs. 2005;14(20):1056–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine Committee on Care at the End of Life. A profile of death and dying in America. In: Field MJ, Cassel CK, eds. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1997. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK233601/. Accessed January 25, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma RK, Dy SM. Cross-cultural communication and use of the family meeting in palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28(6):437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silveira MJ, Kim SYH, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teno JM, Gruneir A, Schwartz Z, Nanda A, Wetle T Association between advance directives and quality of end-of-life care: a national study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker CA, Wright G, Schmit K. Perceptions of dying well and distressing death by acute care nurses. Appl Nurs Res. 2017. ;33:149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beckstrand RL, Callister LC, Kirchhoff KT Providing a “good death”: critical care nurses’ suggestions for improving end-of-life care. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15(1):38–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeBaron VT, Cooke A, Resmini J, et al. Clergy views on a good versus a poor death: ministry to the terminally ill. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(12):1000–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, McIntyre LM, Tulsky JA. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(10):825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bratcher JR. How do critical care nurses define a “good death” in the intensive care unit? Crit Care Nurs Q. 2010;33(1):87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaune L, Newman C. In search of a good death: can children with life threatening illness and their families experience a good death? BMJ. 2003;327(7408):222–223. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5979–5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.October TW, Fisher KR, Feudtner C, Hinds PS. The parent perspective: “being a good parent” when making critical decisions in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(4):291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheeler I. Parental bereavement: the crisis of meaning. Death Stud. 2001;25(1):51–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curley MAQ. Mutuality: an expression of nursing presence. J Pediatr Nurs. 1997;12(4):208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Committee on Bioethics. Guidelines on forgoing life-sustaining medical treatment. Pediatrics. 1994;93(3):532–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feudtner C, Nathanson PG. Pediatric palliative care and pediatric medical ethics: opportunities and challenges. Pediatrics. 2014;133(suppl 1):S1–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooten D, Youngblut JM, Seagrave L, et al. Parent’s perceptions of health care providers actions around child ICU death: what helped, what did not. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(1):40–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer E, Ritholz MD, Burns JP, Truog RD. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: parents’ priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meert K, Briller SH, Schim SM, Thurston C, Kabel A. Examining the needs of bereaved parents in the pediatric intensive care unit: a qualitative study. Death Stud. 2009;33(8):712–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butler AE, Hall H, Copnell B. Becoming a team: the nature of the parent-healthcare provider relationship when a child is dying in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;40:e26–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butler AE, Copnell B, Hall H. “Some were certainly better than others”—bereaved parents’ judgements of healthcare providers in the paediatric intensive care unit: a grounded theory study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;45:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macdonald ME, Liben S, Carnevale FA, et al. Parental perspectives on hospital staff members’ acts of kindness and commemoration after a child’s death. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):884–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGraw SA,Truog RD, Solomon MZ, Cohen-Bearak A, Sellers DE, Meyer EC. “I was able to still be her mom”—parenting at end of life in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13(6):e350–e356. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31825b5607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer E, Burns JP, Griffith JL, Truog RD. Parental perspectives on end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meert K, Eggly S, Pollack M, et al. Parents’ perspectives on physician-parent communication near the time of a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(1):2–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellali T, Papadatou D. Parental grief following the brain death of a child: does consent or refusal to organ donation affect their grief? Death Stud. 2006;30(10):883–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Field M, Behrman RE. When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hinds PS, Schum L, Baker JN, Wolfe J. Key factors affecting dying children and their families. J Palliat Med. 2005; 8(suppl 1):S70–S78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balluffi A, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, Tucker M, Dominguez T, Helfaer M. Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5(6):547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Falkenburg JL,Tibboel D, Ganzevoort RR, Gischler S, Hagoort J, van Dijk M. Parental physical proximity in end-of-life care in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(5):e212–e217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meert K, Briller SH, Schim SM, Thurston CS. Exploring parents’ environmental needs at the time of a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(6):623–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macnab A, Northway T, Ryall K, Scott D, Straw G. Death and bereavement in a paediatric intensive care unit: parental perceptions of staff support. Paediatr Child Health. 2003;8(6):357–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilmer MJ, Foster T, Bell C, Mulder J, Carter B. Parental perceptions of care of children at end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2012;30(1):53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lannen P, Wolfe J, Prigerson H, Onelov E, Kreicbergs U. Unresolved grief in a national sample of bereaved parents: impaired mental and physical health 4 to 9 years later. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(36):5870–5876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenberg AR, Baker KS, Syrjala K, Wolfe J. Systematic review of psychosocial morbidities among bereaved parents of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(4):503–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brooten D, Youngblut JM, Charles D, Roche R, Hidalgo I, Malkawi F Death rituals reported by white, black, and Hispanic parents following the ICU death of an infant or child. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(2):132–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meert K, Thurston CS, Briller SH.The spiritual needs of parents at the time of their child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit and during bereavement: a qualitative study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(4):420–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Widger K, Picot C. Parents’ perceptions of the quality of pediatric and perinatal end-of-life care. Pediatr Nurs. 2008;34(1):53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson MR, Thiel MM, Backus MM, Meyer EC. Matters of spirituality at the end of life in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e719–e729. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neimeyer RA, Klass D, Dennis MR. A social constructionist account of grief: loss and the narration of meaning. Death Stud. 2014;38(8):485–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neimeyer RA, Prigerson H, Davies B. Mourning and meaning. Am Behav Sci. 2002;46(2):235–251. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bergstraesser E, Inglin S, Hornung R, Landolt MA. Dyadic coping of parents after the death of a child. Death Stud. 2015;39(1-5):128–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arnold J, Gemma PB. The continuing process of parental grief. Death Stud. 2008;32(7):658–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud. 1999;23(3):197–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keele L, Meert KL, Berg RA, et al. Limiting and withdrawing life support in the PICU: for whom are these options discussed? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(2):110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McKinley D, Blackford J. Nurses’ experiences of caring for culturally and linguistically diverse families when their child dies. Int J Nurs Pract. 2001;7(4):251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stayer D, Lockhart JS. Living with dying in the pediatric intensive care unit: a nursing perspective. Am J Crit Care. 2016;25(4):350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Broden EG, Uveges MK. Applications of grief and bereavement theory for critical care nurses. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2018;29(3):354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]