Abstract

The development of nanomaterials incorporating organic components holds significant importance in addressing the efficient removal of metal ions through adsorption. Hence, in this study, a novel MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base nanocomposite was successfully synthesized by crosslinking MnFe2O4 nanoparticles with functionalized chitosan using a novel Schiff base. The Schiff base was created through the condensation reaction between 2-aminophenol and terephthalaldehyde. Comprehensive characterization of the synthesized nanocomposite was performed through FT-IR, XRD, SEM, and VSM analyses, revealing a less crystalline arrangement compared to pure chitosan, a rough and non-uniform surface morphology, and a reduced magnetization value of 30 emu/g. Furthermore, the synthesized MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base nanocomposite was working as an adsorbent for the effective disposal of Zn(II) ions from aqueous solutions. The synthesized nanocomposite exhibited a maximum sorption capacity of 289.86 mg/g for Zn(II) ions. Additionally, the results indicated that the removal of Zn(II) ions by the synthesized nanocomposite was a spontaneous, chemical, and endothermic process, aligning well with the Langmuir isotherm as well as the pseudo-second-order model. Furthermore, at pH 7.5, with a contact duration of 100 min and a temperature of 328 K, the fabricated nanocomposite reached its maximum sorption capacity for Zn(II) ions. The results of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of the newly synthesized MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base nanocomposite in removing Zn(II) ions from aqueous media. The novel synthesis approach and the high adsorption capacity of 289.86 mg/g underscore the potential of this composite for practical applications in industrial wastewater treatment. The dual removal mechanism involving electrostatic attraction and complexation processes further enhances its utility, making it a valuable contribution to the field of environmental remediation.

Keywords: Adsorption, MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base nanocomposite, Zn(II) ions

Subject terms: Pollution remediation, Nanoparticle synthesis

Introduction

Eliminating toxic heavy metals from liquid streams poses a significant challenge for industries that release effluents containing such metals1–3. Zinc is a crucial element, yet its presence in the air, water, and food must adhere to specified tolerance limits. Exceeding these limits could pose harm to both humans and animals4,5. Numerous sectors, particularly those involved in electroplating, battery manufacturing, pigment production, and ammunition manufacturing, consistently discharge Zn(II) ions into their wastewater6–10. Despite Zn(II) having a d10 electronic configuration, which indeed makes it relatively stable, its presence in excessive amounts can lead to significant environmental and health issues. Excessive consumption of Zn(II) ions may result in respiratory impairment, marked by heightened respiratory activities such as increased breathing rate, frequency and volume of ventilation, coughing, and a reduction in oxygen elimination efficiency. Additionally, Zn(II) ions can bioaccumulate in aquatic organisms, leading to toxic effects throughout the food chain and potentially affecting human health. Therefore, considering Zn(II) as a pollutant is justified due to its potential to cause harm when present in high concentrations in the environment, even though it is essential in trace amounts for biological systems11,12. Numerous methods have been implemented to eliminate metal ions through various treatment procedures. Current treatment processes include oxidation/reduction, precipitation, coagulation, electrochemical, membrane filtration, reverse osmosis, and adsorption13–19. Every technique has its pros and cons, but adsorption methods present the most straightforward approach for generating the highest quality of treated water. Also, adsorption can be applied to a wide range of metal ions, making it a versatile method for metal removal. Adsorption processes are generally straightforward, requiring less complex equipment and operational procedures20. The development of nanomaterials incorporating organic components holds significant importance as adsorbents in addressing the removal of metal ions through complex formation and/or electrostatic attraction21–23. Recently, modified chitosan compounds, such as chitosan-cellulose composite, CaCO3/chitosan composite, Fe3O4/chitosan composite, chitosan/TiO2 composite, MoS2/chitosan composite, and graphene/chitosan composite, were utilized as adsorbents for the disposal of heavy metals24–28. Despite the plethora of existing studies on the removal of metal ions, the development of novel adsorbents remains crucial. This study introduces a MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base nanocomposite, synthesized through a unique condensation reaction between 2-aminophenol and terephthalaldehyde. This new material offers enhanced adsorption capacity and a versatile removal mechanism (electrostatic attraction and complex formation), providing a significant improvement over previously reported adsorbents. Consequently, the innovative aspect of this research comes through the formation of a new Schiff base and loading it on chitosan and manganese ferrite nanoparticles, to form a novel nanocomposite that works as an adsorbent with the ability to get rid of Zn(II) ions by electrostatic attraction and complex formation through the hydroxyl (OH) as well as imine (C=N) groups. Also, the effects of pH, contact time, temperature, and concentration on the removal of Zn(II) ions by the synthesized nanocomposite were considered.

Experimental

Materials

Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), 2-aminophenol (C6H7NO), acetic acid (CH3COOH), terephthalaldehyde (C8H6O2), hydrochloric acid (HCl), zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O), and chitosan ((C6H11NO4)n), were of analytical grade (purity = 99.99%) and underwent no extra refining.

Synthesis of MnFe2O4/Schiff base/chitosan composite

Synthesis of chitosan beads

The chitosan chemical solution is prepared via dissolving 6 g of chitosan flakes in 350 mL of 2.5% acetic acid. Then, the previous solution is added part by part to 350 mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide solution with continuous stirring for an hour. The chitosan beads formed were isolated and thoroughly washed well several times using methanol and distilled water.

Synthesis of Schiff base

(E)-4-((2-hydroxyphenylimino)methyl)benzaldehyde Schiff base was synthesized as displayed in Fig. 1. In this regard, 50 mL of a methanolic solution of 2-aminophenol (3.64 g) was added to 50 mL of a methanolic solution of terephthalaldehyde (4.47 g). Then, the mixture was refluxed for 5 h in the presence of a few drops of acetic acid. The resulting solution was then cooled and poured onto crushed ice, and the resulting yellow precipitate was separated, recrystallized with water, and dried in the air.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite.

Synthesis of chitosan/Schiff base composite

Chitosan is cross-linked with Schiff base as displayed in Fig. 1. In this regard, 3 g of chitosan beads was immersed in 60 mL of methanol. Also, 3 g of the produced Schiff base was dissolved in 60 mL of methanol. Besides, the Schiff base solution was added to the chitosan then the mixture was stirred for 5 h. The Schiff base/chitosan composite obtained was isolated, thoroughly washed well several times with methanol and distilled water, and then dried in the air.

Synthesis of MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite

MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were produced following the methodology outlined in our earlier research29. Subsequently, the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles underwent modification using a Schiff base/chitosan composite, as depicted in Fig. 1. For this process, 3 g of the Schiff base/chitosan composite was dissolved in 150 mL of a 2.5% acetic acid solution. Following this, 3 g of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were introduced, and the resulting blend was stirred for 5 h. Finally, the resulting MnFe2O4/Schiff base/chitosan composite was separated, washed well several times with methanol and distilled water, and dried in the air.

Instrumentation

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the synthesized nanocomposite was conducted utilizing a Shimadzu XRD-6000 diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (wavelength of 0.154 nm). The detection of the functional groups in both chitosan and modified chitosan was performed using a Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Frontier). The surface morphology of pure chitosan and its modified form was examined through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Hitachi SU8220 instrument. The magnetic properties of the fabricated nanocomposite were explored at 25 °C using a MPMS-XL-7 vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). The pH of the metal ion solutions was determined using a 3510 Complete Jenway pH meter. The concentration of Zn(II) ions was quantified through an AA-6300 Shimadzu atomic absorption spectrophotometer. The morphology of the synthesized nanocomposite was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL JEM 2100F instrument, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan). The BET surface area of the synthesized nanocomposite was determined using an N2 gas sorption analyzer (Quantachrome, Model: TouchWin, Graz, Austria).

Removal of Zn(II) ions from aqueous media

Experiments on adsorption concerning pH (ranging from 2.5 to 7.5) involved mixing 50 mg of the composite with 100 mL of a 150 mg/L solution of Zn(II) ions for 180 min utilizing a magnetic stirrer. Similarly, experiments exploring the impact of contact time (ranging from 20 to 140 min) were conducted under the previously described conditions at pH 7.5. Temperature-related adsorption experiments (ranging from 298 to 328 K) were carried out following the aforementioned procedure at pH 7.5 and 100 min. Additionally, experiments examining the initial concentration of Zn(II) ions (ranging from 50 to 250 mg/L) were performed under the previously specified conditions at pH 7.5, 100 min, and 328 K.

The amount of Zn(II) ions adsorbed by the fabricated nanocomposite (Q, mg/g) was calculated through Eq. (1)30–34.

| 1 |

M (g) represents the amount of adsorbent used, while V (L) denotes the volume of the Zn(II) solution.

The percentage removal of Zn(II) ions with the prepared composite (% R) was determined using Eq. 230–34.

| 2 |

Ce represents the equilibrium concentration of Zn(II) ions (mg/L), while Ci denotes the initial concentration of Zn(II) ions (mg/L).

Results and discussion

Examination of the MgFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) was utilized to reveal the structural characteristics and crystalline size of chitosan, MnFe2O4 nanoparticles, and MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite, as displayed in Fig. 2A–C, respectively. The sorption capacity of a sorbent is significantly influenced by its crystal assembly. The XRD diffraction shape of pure chitosan flakes exhibited prominent peaks at 2Ɵ = 9.9° and 22.5°, signifying the establishment of inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds facilitated by the existence of amino (NH2) groups, which is consistent with the known crystal structure of chitosan. Peaks at 2Ɵ = 18.17°, 30.03°, 35.49°, 37.07°, 43.16°, 53.54°, 57.11°, 62.87°, 71.27°, 74.22°, 75.15°, and 79.26° corresponded to the (111), (220), (311), (222), (400), (442), (511), (440), (620), (533), (622), and (444) Miller planes of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles, respectively, as identified by JCPDS No. 38-043029. Similarly, the distinctive diffraction peaks of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were observed in the MnFe2O4/Schiff base/chitosan composite pattern. This investigation found that chitosan modified with Schiff base exhibited various aromatic side groups in its chemical composition, indicating that altering replacement groups in the chitosan molecule could modulate crystallinity. As a result, the modified chitosan demonstrated a less crystalline arrangement compared to pure chitosan.

Figure 2.

XRD analysis of (A) chitosan, (B) MnFe2O4 nanoparticles, and (C) MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

Figure 3A–C displays the FTIR spectra of chitosan, chitosan/Schiff base, and MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite, respectively. The typical peaks of chitosan are positioned at 3570, 3259, 2971, 1680, 1464, 1304, 1237, 1045, and 795/cm. In addition, the absorption peak positioned at 3570/cm is owing to the asymmetric stretching vibration of the NH2 group and/or the stretching vibration of the OH group. The absorption peak positioned at 3259/cm is owing to the symmetric stretching vibration of the NH2 group. The absorption peak positioned at 2971/cm can be attributed to the stretching vibration of the aliphatic CH groups. The absorption peak positioned at 1680/cm is due to the bending vibration of the OH group. Besides, the absorption peak positioned at 1464/cm is attributed to the bending vibration of the CH group. The absorption peak positioned at 1304/cm is assigned to the stretching vibration of the C–N group. The absorption peak positioned at 1237/cm is attributed to the stretching vibration of the C–O group. The absorption peak positioned at 1045/cm is attributed to the stretching vibration of the C–C group. The absorption peak positioned at 795/cm is assigned to the glycosidic linkage between chitosan units. The obvious displacements of these characteristic peaks to the higher or lower wavenumbers reveal chemical associations of the chitosan/Schiff base with the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles. Besides, the peaks positioned at 1610 and 1605/cm is attributed to the stretching vibrations of the C=N group21–23. The peaks positioned at 535 and 434/cm can be assigned to the stretching vibration of the Fe–O and Mn–O groups of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles, respectively29.

Figure 3.

FTIR absorption spectra of (A) chitosan, (B) chitosan/Schiff base, and (C) MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Figure 4A–C displays the SEM images of pure chitosan, MnFe2O4 nanoparticles, and MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite, respectively. Pure chitosan displays an irregular surface marked by a unique crystalline structure. The MnFe2O4 nanoparticles exhibit a spherical shape. Conversely, the MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite reveals a notably distinct morphological structure, showcasing a rough, non-uniform, and irregular arrangement of the sorbent surface.

Figure 4.

SEM images of (A) chitosan, (B) MnFe2O4 nanoparticles, and (C) MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite.

Vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM)

Figure 5A, B displays the magnetization curves of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles in addition to the MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite, respectively. Hence, the magnetization of the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles as well as the MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite is 85 and 30 emu/g, respectively. The decrease in the magnetization of the MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite may be due to the crosslinking of chitosan/Schiff base and MnFe2O4 nanoparticles.

Figure 5.

Magnetization curves of (A) MnFe2O4 nanoparticles and (B) MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The TEM images of the MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base nanocomposite are presented in Fig. 6. The images reveal that the composite particles are predominantly spherical and well-dispersed with an average diameter of approximately 9.54 nm. This confirms the nanoscale size of the synthesized material, thereby justifying its classification as a nanocomposite.

Figure 6.

TEM images of MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite.

BET surface area analysis

The BET surface area of the MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base nanocomposite was found to be 70.32 m2/g, with a total pore volume of 0.1235 cm3/g and an average pore size of 3.58 nm. These values indicate a substantial surface area and porosity, which are crucial factors for enhancing adsorption performance. A higher surface area provides more active sites for the adsorption of Zn(II) ions, thereby improving the overall efficiency of the nanocomposite as an adsorbent.

Removal of Zn(II) ions from aqueous media

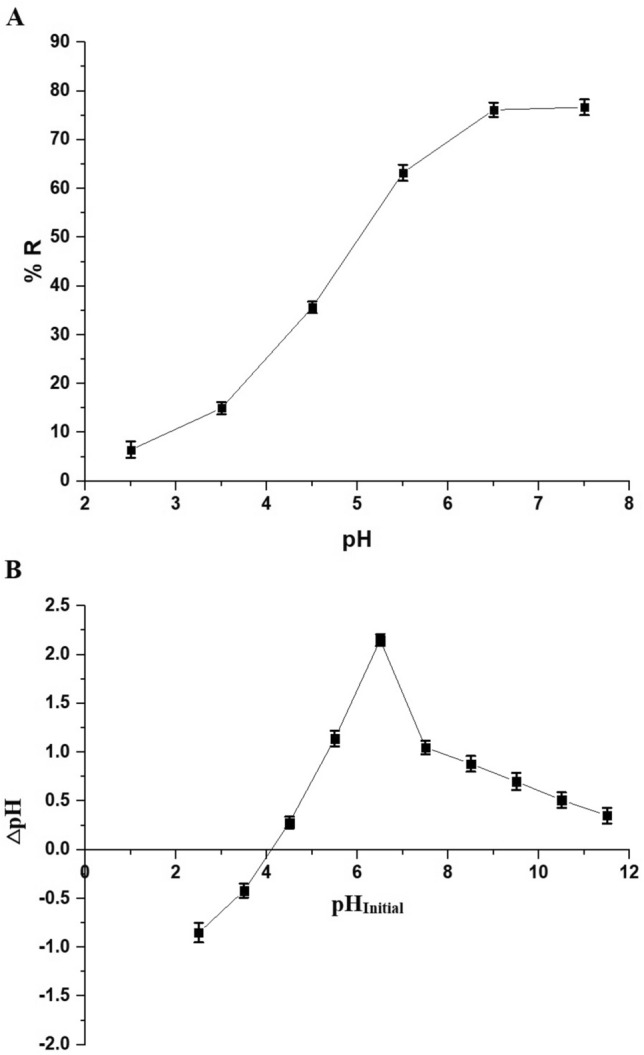

Effect of pH

As shown in Fig. 7A, the Zn(II) ion removal percentage increased from 6.45 to 76.65% as the pH was raised from 2.5 to 7.5. This variation can be attributed to the point of zero charge (pHPZC) of the MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite, which is 4.09, as illustrated in Fig. 7B. MnFe2O4 nanoparticles exhibit unique magnetic and surface properties that facilitate the attraction of H+ and OH− ions. This attraction can be explained through the interaction between the magnetic nanoparticles and the charged species in the solution. The MnFe2O4 surface can become charged depending on the pH of the solution, influencing its interaction with H+ and OH− ions. At lower pH values, the surface of MnFe2O4 can become positively charged, attracting OH- ions due to electrostatic forces. Conversely, at higher pH values, the surface can acquire a negative charge, attracting H+ ions. Additionally, the presence of functional groups such as hydroxyl (–OH) on the Schiff base-chitosan matrix further enhances the interaction with H+ and OH- ions. If the pH was below 4.09, a decrease in the removal percentage of Zn(II) ions occurred due to the electrostatic repulsion between the positively charged composite surface and Zn(II) ions, as depicted in Fig. 8. Conversely, at pH values above 4.09, an increase in the removal percentage of Zn(II) ions was observed due to electrostatic attraction between the negatively charged composite surface and Zn(II) ions, along with complexation, as indicated in Fig. 8.

Figure 7.

(A) Impact of pH on the Zn(II) ion removal efficiency by the synthesized nanocomposite. (B) Point of zero charge of the synthesized nanocomposite.

Figure 8.

Removal mechanism of Zn(II) ions using the synthesized nanocomposite.

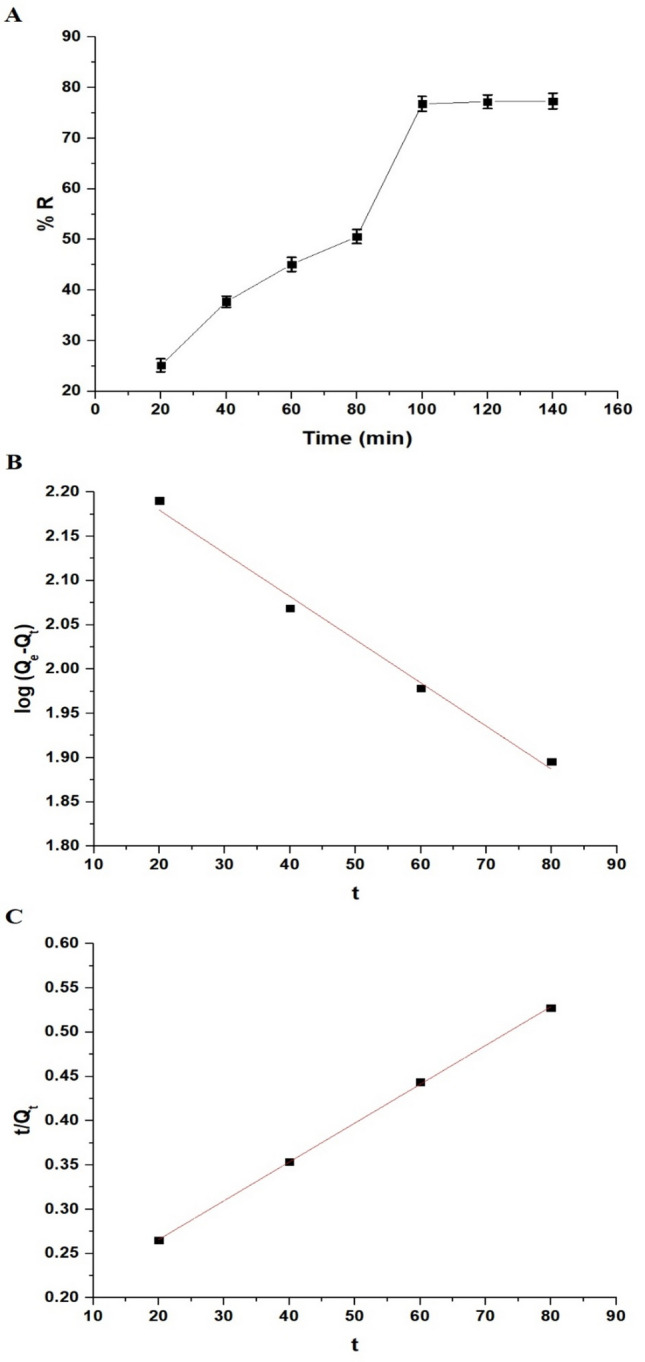

Effect of time

The data in Fig. 9A indicates that the Zn(II) ion elimination percentage rose from 25.15 to 76.79% as the elimination time progressed from 20 to 100 min. Additionally, the elimination percentage of Zn(II) ions showed a nearly constant trend when the time extended from 100 to 140 min, attributed to the complete incorporation of active centers.

Figure 9.

(A) Effect of time on the elimination percentage of Zn(II) ions by the synthesized nanocomposite. (B) The pseudo-first-order and (C) pseudo-second-order kinetic models.

To comprehend sorption kinetics, an analysis of the experimental sorption data was conducted employing two kinetic models: the pseudo-first-order model (represented by Eq. 3) and the pseudo-second-order model (expressed by Eq. 4)22,29.

| 3 |

| 4 |

Qt demonstrates the quantity of Zn(II) ions eliminated at time t (mg/g) whereas Qe indicates the quantity of Zn(II) ions eliminated at equilibrium (mg/g). In addition, K1 describes the rate constant of the pseudo-first-order (1/min) whereas K2 describes the rate constant of the pseudo-second-order (g/mg·min). In addition, Fig. 9B, C shows the pseudo-first-order in addition to the pseudo-second-order models, respectively. Besides, Table 1 provides the constant values for the two kinetic models. Analysis of Table 1 demonstrates that the R2 value regarding the pseudo-second-order kinetic model is higher than that of the pseudo-first-order kinetic model. Moreover, in the pseudo-second-order model, the calculated sorption capacity is more closely aligned with the experimental sorption capacity (QExp) than in the pseudo-first-order model. Therefore, the sorption of Zn(II) ions is better described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for Zn(II) ion elimination by the synthesized nanocomposite.

| QExp (mg/g) | Pseudo-first-order | Pseudo-Second-order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 (1/min) | Q (mg/g) | R2 | K2 (g/mg min) | Q (mg/g) | R2 | |

| 230.36 | 0.01122 | 189.17 | 0.9877 | 0.00011 | 228.31 | 0.9963 |

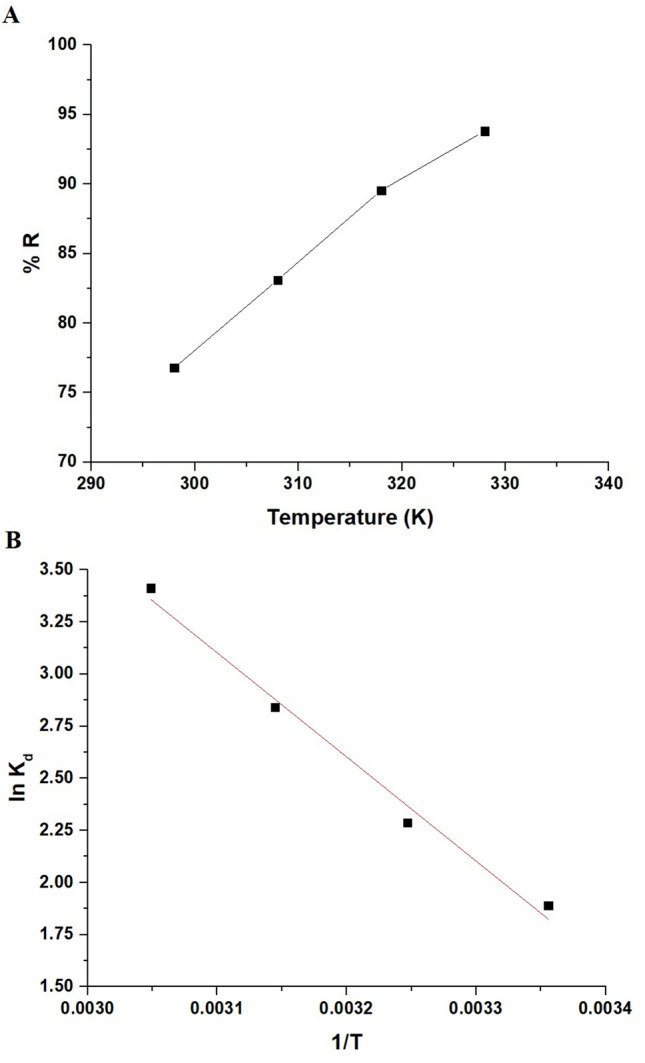

Effect of temperature

As demonstrated in Fig. 10A, the Zn(II) ion elimination percentage elevated from 76.79 to 93.81% as the temperature expanded from 298 to 328 K. The sorption process of Zn(II) ions is temperature-dependent and involves various thermodynamic constants. Thermodynamic parameters, including enthalpy change (ΔHo), Gibbs free energy change (ΔGo), and entropy change (ΔSo), were utilized to evaluate the thermodynamic feasibility of the sorption process. These constants were estimated through Eqs. (5, 6, and 7)22,29.

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

Figure 10.

(A) Influence of temperature on the Zn(II) ion elimination percentage by the synthesized nanocomposite. (B) Plot of ln Kd versus 1/T (B).

T denotes the elimination temperature (K), and R is the universal gas constant (KJ/molK). Besides, the distribution coefficient (L/g) is denoted as Kd. Figure 10B illustrates the graph of lnKd versus 1/T, with the thermodynamic constants detailed in Table 2. Examining Table 2 reveals that the negative values of ΔGo signify the spontaneity of the Zn(II) sorption onto the MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite. Furthermore, the positive sign and magnitude of ΔHo suggest a chemisorptive and endothermic elimination process. In addition, the positive ΔSo value indicates an increased level of irregularity at the interface between the solution and the adsorbent.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic parameters for Zn(II) ion elimination using the synthesized nanocomposite.

| △Ho (KJ/mol) |

△So (KJ/molK) |

△Go (KJ/mol) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | 308 | 318 | 328 | ||

| 41.75 | 0.1553 | − 46.29 | − 47.85 | − 49.39 | − 50.95 |

Effect of concentration

As demonstrated in Fig. 11A, the percentage of Zn(II) ion elimination decreased from 97.50 to 56.89% as the concentration increased from 50 to 250 mg/L. To comprehend sorption equilibrium, an analysis of the experimental sorption data was conducted employing two equilibrium isotherms: the Langmuir isotherm (represented by Eq. 8) and the Freundlich isotherm (expressed by Eq. 9)22,29.

| 8 |

| 9 |

where, 1/n denotes the non-uniformity constant while KL denotes the Langmuir equilibrium constant (L/mg). In addition, KF denotes the Freundlich equilibrium constant (mg/g)(L/mg)1/n while Qmax denotes the Langmuir uppermost adsorption capacity (mg/g). Besides, Eq. (10) can be utilized to compute Qmax through the application of the Freundlich isotherm22,29.

| 10 |

Figure 11.

(A) Impact of concentration on the Zn(II) ion elimination percentage by the synthesized nanocomposite. (B) The Langmuir and (C) Freundlich isotherm.

Figure 11B, C illustrates the Langmuir in addition to the Freundlich isotherms, respectively. Also, the constant values for the two equilibrium isotherms were recorded in Table 3. As indicated in Table 3, the R2 value regarding the Langmuir equilibrium isotherm outperforms that of the Freundlich equilibrium isotherm. Thus, it can be concluded that the sorption of Zn(II) ions adheres to the Langmuir isotherm. This confirmation suggests that the adsorbent surface is homogeneous, with all adsorption sites being identical.

Table 3.

Constants of equilibrium for Zn(II) ion elimination using the synthesized nanocomposite.

| Langmuir | Freundlich | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qmax (mg/g) | KL (L/mg) | R2 | Qmax (mg/g) | KF (mg/g)(L/mg)1/n | 1/n | R2 |

| 289.86 | 0.5838 | 0.9995 | 359.71 | 121.61 | 0.2164 | 0.6299 |

The sorption capacity of the MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite in this study is contrasted with the values reported in Table 4 from the literature35–39. Notably, the uptake capacity of the synthesized nanocomposite exceeds that of the mainstream of the adsorbents mentioned in the literature. Consequently, this cost-effective and easily preparable composite can serve as a suitable alternative to more expensive adsorbents for the effective removal of Zn(II) ions.

Table 4.

Comparison of the uptake capacity of different sorbents with that of MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite towards Zn(II) ions.

| Adsorbent | Qmax (mg/g) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| CuMgAl-layered double hydroxides/montmorillonite nanocomposite | 154.21 | 35 |

| Silica/1-hydroxy-2-acetonaphthone nanocomposite | 45.126 | 23 |

| Montmorillonite | 9.664 | 36 |

| Guanyl-modified cellulose | 68.52 | 37 |

| Modified magnetic chitosan | 35.30 | 38 |

| Zeolite | 42.017 | 39 |

| MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base composite | 289.86 | This work |

Conclusions

A novel nanocomposite of MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base was facilely fabricated by crosslinking MnFe2O4 nanoparticles with modified chitosan using a novel Schiff base. The Schiff base was prepared through a condensation reaction involving 2-aminophenol and terephthalaldehyde. The characterization of the synthesized nanocomposite was accomplished using VSM, SEM, XRD, and FT-IR tools. Additionally, the synthesized MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base nanocomposite served as an efficient adsorbent for removing Zn(II) ions from aqueous media through complexation and electrostatic attraction processes. The greatest sorption capacity of the nanocomposite for Zn(II) ions was 289.86 mg/g. Notably, the adsorption capacity of this nanocomposite is significantly higher compared to other conventional adsorbents, highlighting its superior efficiency. Also, the results showed that the removal of Zn(II) ions by the nanocomposite was chemical and matched well with the Langmuir isotherm and pseudo-second-order model. The high adsorption capacity, coupled with the dual removal mechanism involving electrostatic attraction and complexation processes, underscores the potential of this composite for practical applications in industrial wastewater treatment. The positive enthalpy change (ΔHo) and negative Gibbs free energy change (ΔGo) indicate that the adsorption process is both endothermic and spontaneous. Furthermore, the composite’s high BET surface area and porosity significantly enhance its adsorption performance, making it a valuable contribution to the field of environmental remediation. The promising results of this study suggest several avenues for future research. Future work could explore the regeneration and reuse of the MnFe2O4/chitosan/Schiff base nanocomposite to enhance its economic feasibility and sustainability. Additionally, investigating the composite's performance in real industrial wastewater, which contains multiple pollutants, would provide insights into its practical applications. Scaling up the synthesis process and evaluating the long-term stability and effectiveness of the nanocomposite under various environmental conditions would also be beneficial. Moreover, modifications to the composite to target other heavy metals and organic pollutants could expand its utility in diverse environmental remediation scenarios.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Shaqra University for supporting this work.

Author contributions

Zahrah Alhalili (methodology (equal)), conceptualization (equal), and (writing—review and editing (equal); Ehab A. Abdelrahman (methodology (equal)), conceptualization (equal), and (writing—review and editing (equal).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zahrah Alhalili, Email: zalholaili@su.edu.sa.

Ehab A. Abdelrahman, Email: EAAAhmed@imamu.edu.sa

References

- 1.Yu, T. et al. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Tourmaline for heavy metals removal in wastewater treatment : A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.131, 44–53 (2024). 10.1016/j.jiec.2023.10.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ugwu, D. I. & Conradie, J. The use of bidentate ligands for heavy metal removal from contaminated water. Environ. Adv.15, 100460 (2024). 10.1016/j.envadv.2023.100460 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Syeda, H. I., Muthukumaran, S. & Baskaran, K. Polyglutamic acid and its derivatives as multi-functional biopolymers for the removal of heavy metals from water: A review. J. Water Process Eng.56, 104367 (2023). 10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.104367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubilay, Ş, Gürkan, R., Savran, A. & Şahan, T. Removal of Cu(II), Zn(II) and Co(II) ions from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto natural bentonite. Adsorption13, 41–51 (2007). 10.1007/s10450-007-9003-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Najafi, F. Removal of zinc(II) ion by graphene oxide (GO) and functionalized graphene oxide–glycine (GO–G) as adsorbents from aqueous solution: Kinetics studies. Int. Nano Lett.5, 171–178 (2015). 10.1007/s40089-015-0151-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naveen Chandra Joshi, B. S. & Rawat Prashant Semwal, N. K. Effective removal of highly toxic Pb2+ and Cd2+ ions using reduced graphene oxide, polythiophene, and silica-based nanocomposite. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol.45, 58–67 (2022). 10.1080/01932691.2022.2127752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naveen Chandra Joshi, P. G. A mini review on heavy metal contamination in vegetable crops. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.2023, 85 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshi, N. C. Synthesis of r-GO/PANI/ZnO based material and its application in the treatment of wastewater containing Cd2+ and Cr6+ ions. Sep. Sci. Technol.57, 2420–2431 (2022). 10.1080/01496395.2022.2069042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi, N. C. Highly efficient removal of Pb2+ and Cu2+ ions using r-GO/PPY/SiO2 based nanosorbent. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.2022, 859 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naveen, C. J., Sanjay, U., Niraj, K. & Chatana, S. A. J. Synthesis and photocatalytic activity of highly efficient NiFe2O4/r-GO based photocatalyst. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol.45, 768–779 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Mijalli, S. H. Bioadsorptive removal of the pollutant Zn(II) from wastewater by delftia tsuruhatensis biomass. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci.2022, 18–21 (2022). 10.1155/2022/4316954 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro, D. et al. Chemical modification of agro-industrial waste-based bioadsorbents for enhanced removal of Zn(II) ions from aqueous solutions. Mater. Basel14, 2134 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao, J., Ji, L., Li, C., Hu, C. & Wu, K. Rapid, efficient and economic removal of organic dyes and heavy metals from wastewater by zinc-induced in-situ reduction and precipitation of graphene oxide. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng.88, 137–145 (2018). 10.1016/j.jtice.2018.03.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang, X. et al. Sustainable and reagent-free cathodic precipitation for high-efficiency removal of heavy metals from soil leachate. Environ. Pollut.320, 121002 (2023). 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skotta, A. et al. Suspended matter and heavy metals (Cu and Zn) removal from water by coagulation/flocculation process using a new Bio-flocculant: Lepidium sativum. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng.145, 104792 (2023). 10.1016/j.jtice.2023.104792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, J. G. et al. Ion-exchangeable and sorptive reinforced membranes for efficient electrochemical removal of heavy metal ions in wastewater. J. Clean. Prod.438, 140779 (2024). 10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiang, H., Min, X., Tang, C. J., Sillanpää, M. & Zhao, F. Recent advances in membrane filtration for heavy metal removal from wastewater: A mini review. J. Water Process Eng.49, 103023 (2022). 10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.103023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pezeshki, H., Hashemi, M. & Rajabi, S. Removal of arsenic as a potentially toxic element from drinking water by filtration: A mini review of nanofiltration and reverse osmosis techniques. Heliyon9, e14246 (2023). 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdelrahman, E. A. et al. Remarkable removal of Pb(II) Ions from aqueous media using facilely synthesized sodium manganese silicate hydroxide hydrate/manganese silicate as a novel nanocomposite. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater.10.1007/s10904-023-02895-3 (2023). 10.1007/s10904-023-02895-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, Y. et al. Synthesis and adsorption performance of three-dimensional gels assembled by carbon nanomaterials for heavy metal removal from water: A review. Sci. Total Environ.852, 158201 (2022). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdelrahman, E. A. et al. Modification of hydroxysodalite nanoparticles by (3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane and isatoic anhydride as a novel composite for efficient sorption of Cu(II) ions from aqueous media. Silicon10.1007/s12633-023-02743-6 (2023). 10.1007/s12633-023-02743-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shafeeq, K. et al. Functionalization of calcium silicate/sodium calcium silicate nanostructures with chitosan and chitosan/glutaraldehyde as novel nanocomposites for the efficient adsorption of Cd (II) and Cu (II) ions from aqueous solutions. Silicon10.1007/s12633-023-02793-w (2023). 10.1007/s12633-023-02793-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Wasidi, A. S., Naglah, A. M., Saad, F. A. & Abdelrahman, E. A. Modification of silica nanoparticles with 1-hydroxy-2-acetonaphthone as a novel composite for the efficient removal of Ni(II), Cu(II), Zn(II), and Hg(II) ions from aqueous media. Arab. J. Chem.15, 104010 (2022). 10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kausar, A. et al. Chitosan-cellulose composite for the adsorptive removal of anionic dyes: Experimental and theoretically approach. J. Mol. Liq.391, 123347 (2023). 10.1016/j.molliq.2023.123347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassan, S. S. M., El-Aziz, M. E. A., Fayez, A. E. S., Kamel, A. H. & Youssef, A. M. Synthesis and characterization of bio-nanocomposite based on chitosan and CaCO3 nanoparticles for heavy metals removal. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.255, 128007 (2024). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharifi, M. J., Nouralishahi, A. & Hallajisani, A. Fe3O4-chitosan nanocomposite as a magnetic biosorbent for removal of nickel and cobalt heavy metals from polluted water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.248, 125984 (2023). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Razzaz, A., Ghorban, S., Hosayni, L., Irani, M. & Aliabadi, M. Chitosan nanofibers functionalized by TiO2 nanoparticles for the removal of heavy metal ions. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng.58, 333–343 (2016). 10.1016/j.jtice.2015.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Risha Achaiah, I. et al. Efficient removal of metal ions from aqueous solutions using MoS2 functionalized chitosan Schiff base incorporated with Fe3O4 nanoparticle. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.248, 125976 (2023). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alhalili, Z. & Abdelrahman, E. A. Facile synthesis and characterization of manganese ferrite nanoparticles for the successful removal of safranine T dye from aqueous solutions. Inorganics12, 30 (2024). 10.3390/inorganics12010030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma, A., Mangla, D., Shehnaz, D. & Chaudhry, S. A. Recent advances in magnetic composites as adsorbents for wastewater remediation. J. Environ. Manage.306, 114483 (2022). 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sajid, M., Sharma, A., Choudhry, A. & Chaudhry, S. A. Synthesis, characterization and potential application of functionalised binary metallic sulphide for water reclamation. Colloids Surfaces C Environ. Asp.1, 100011 (2023). 10.1016/j.colsuc.2023.100011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma, A., Mangla, D., Choudhry, A., Sajid, M. & Ali Chaudhry, S. Facile synthesis, physico-chemical studies of Ocimum sanctum magnetic nanocomposite and its adsorptive application against Methylene blue. J. Mol. Liq.362, 119752 (2022). 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sajid, M., Sharma, A. & Chaudhry, S. A. Environmental remediation through bimetallic sulphide-derived adsorbents: Prospects and progress. Chem. Eng. Res. Des.203, 651–662 (2024). 10.1016/j.cherd.2024.01.052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma, A., Choudhry, A., Mangla, B. & Chaudhry, S. A. Sustainable and efficient removal of cationic and neutral dyes from aqueous solution using nano-engineered CuFe2O4/Peanut shell magnetic composite. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy10.1007/s10098-023-02666-1 (2023). 10.1007/s10098-023-02666-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alnasrawi, F. A., Mohammed, A. A. & Al-Musawi, T. J. Synthesis, characterization and adsorptive performance of CuMgAl-layered double hydroxides/montmorillonite nanocomposite for the removal of Zn(II) ions. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag.19, 100771 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen, C., Liu, H., Chen, T., Chen, D. & Frost, R. L. An insight into the removal of Pb(II), Cu(II), Co(II), Cd(II), Zn(II), Ag(I), Hg(I), Cr(VI) by Na(I)-montmorillonite and Ca(II)-montmorillonite. Appl. Clay Sci.118, 239–247 (2015). 10.1016/j.clay.2015.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kenawy, I. M., Hafez, M. A. H., Ismail, M. A. & Hashem, M. A. Adsorption of Cu(II), Cd(II), Hg(II), Pb(II) and Zn(II) from aqueous single metal solutions by guanyl-modified cellulose. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.107, 1538–1549 (2018). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monier, M. & Abdel-Latif, D. A. Preparation of cross-linked magnetic chitosan-phenylthiourea resin for adsorption of Hg(II), Cd(II) and Zn(II) ions from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater.209–210, 240–249 (2012). 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joseph, I. V., Tosheva, L. & Doyle, A. M. Simultaneous removal of Cd(II), Co(II), Cu(II), Pb(II), and Zn(II) ions from aqueous solutions via adsorption on FAU-type zeolites prepared from coal fly ash. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.8, 103895 (2020). 10.1016/j.jece.2020.103895 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.