Abstract

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) has been used safely and effectively in patients with gastric cancer. Our aim was to evaluate the short-term outcomes of total gastrectomy (TG) versus distal gastrectomy (DG) for gastric cancer under ERAS. A prospectively collected database of 1349 patients with gastric cancer who underwent TG or DG between January 2016 and September 2022 was retrospectively analyzed. Propensity score matching analysis was used at a ratio of 1:1 to reduce confounding effects, and perioperative clinical outcomes were compared between the two groups. The primary outcome was overall postoperative complications (POCs). Secondary outcomes comprised time to bowel function recovery, postoperative hospital stay, mortality, and 30-day readmission rate. Of 1349 identified patients, 296 (21.9%) experienced overall POCs. Before matching, multivariable analysis revealed that age, body mass index, diabetes, operation time, and extent of gastrectomy were independent risk factors for overall POCs. After matching, each group comprised 495 patients, and no significant differences were observed between the groups for all parameters except tumor location. Compared with TG, DG was associated with significantly earlier days to first flatus and to eating a soft diet, and shorter postoperative hospital stay (P < 0.05). The incidence of overall- and severe POCs (Clavien–Dindo grade ≥ IIIa) in the TG group was significantly higher vs. the DG group (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the number of days to eating a liquid diet, or mortality and 30-day readmission rates between the groups (P > 0.05). In the subgroup analysis for middle-third gastric cancer, the TG group experienced higher rates of overall- and severe POCs, with a longer postoperative hospital stay. Compared with DG, patients who underwent TG had higher POC rates, slower recovery of bowel function, and longer duration of hospitalization under ERAS. Therefore, caution is needed when initiating early feeding for patients who undergo TG.

Subject terms: Diseases, Gastroenterology, Oncology, Signs and symptoms

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths globally1,2. More than 1 million people were newly diagnosed, with 0.769 million deaths, in 20201,2. Currently, radical gastrectomy provides a considerable survival benefit and is the most effective treatment for gastric cancer. However, the procedure is associated with major stress to the body and significant postoperative morbidity3–5. Not surprisingly, it is important to reduce the surgical stress, which is believed to improve clinical outcomes6.

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) comprises a series of multidisciplinary evidence-based techniques for perioperative care that aim to alleviate the stress response and accelerate postoperative recovery7,8. Several studies have demonstrated that the implementation of ERAS programs in gastrectomy can shorten the time to early ambulation, improve recovery of gut function, and reduce the length of hospital stay without increasing readmission and postoperative complications (POCs) rates9–13. The ERAS protocol is strongly recommended for the perioperative management of gastric cancer in the sixth edition of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines14. The perioperative ERAS clinical practice guideline is similar, regardless of the extent of resection. However, compared with total gastrectomy (TG), distal gastrectomy (DG) is associated with significantly shorter operative time, less operative blood loss, faster recovery, fewer POCs, shorter hospitalization stay, and better quality of life15–20. Hence, we investigated the differences in short-term outcomes between TG and DG for gastric cancer under ERAS.

Methods

Patients

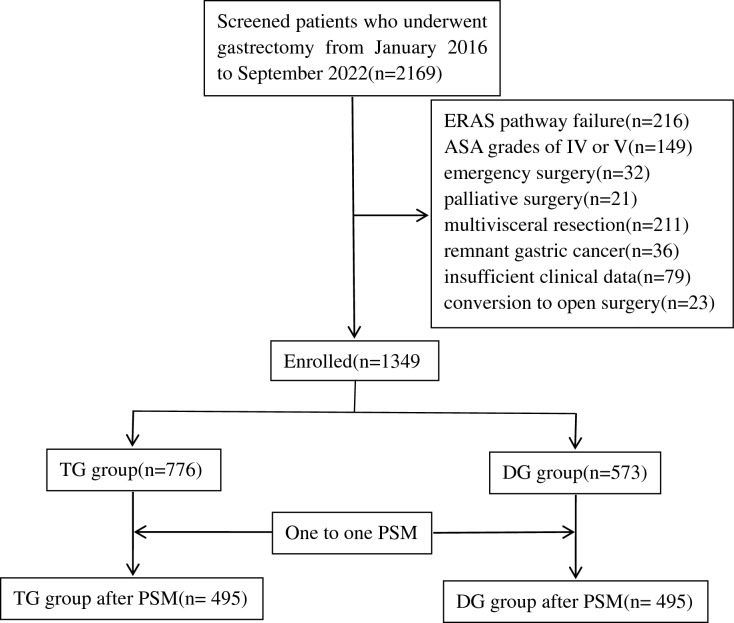

A prospective database of gastric cancer cases from Fujian Cancer Hospital was retrospectively reviewed. From January 2016 to September 2022, 1349 patients who underwent TG or DG were enrolled in our study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age between 18 and 75 years, (2) pathologically-confirmed diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma, (3) elective TG or DG performed with curative intent, and (4) compliance with over 80% of the ERAS elements; lower compliance was considered ERAS pathway failure21. The ERAS pathway is shown in Table 1. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) American Society of Anesthesiologists grade IV or V, (2) emergency surgery owing to complications (bleeding, obstruction, or perforation), (3) palliative surgery, (4) multivisceral resection, (5) remnant gastric cancer, (6) insufficient clinical data for analysis, (7) conversion to open surgery, and (8) robotic gastrectomy. The study flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

ERAS protocol for gastrectomy.

| Time point | Protocol |

|---|---|

| Preoperative |

1. Preadmission education and counseling 2. Routine nutritional screening, and significantly malnourished patients received individual nutritional support 3. No smoking or drinking, training of cardiopulmonary function if necessary 4. No preoperative mechanical bowel preparation 5. Fasting was limited to 2 h for fluid and 6 h for light meal intake Oral administration of 200 ml carbohydrate-rich solution 2 h before anesthesia |

| Operative |

6. Prophylactic use of antibiotics 0.5–1 h before the operation and subsequently every 3 h during the surgical operation 7. Optimize the anesthetic program 8. A multimodal, opioid-sparing, pain management plan should preferably be implemented 9. Monitor body temperature and maintain it at 36–37 °C via intraoperative warming 10. Practice protective lung ventilation 11. According to surgical conditions, try to use as few abdominal drains as possible 12. Nasogastric tube should not be used whenever possible 13. Implement target-directed fluid therapy |

| Postoperative |

Multimodal antiemetic prophylaxis is employed to reduce nausea and vomiting Start clear liquids on POD1. Gradually increase oral liquids intake on POD 2–3. Introduce a soft diet as tolerated on POD 4–6 until discharge 16. Early and progressive active ambulation from POD 1 17. Removal of urinary catheter on POD 1 18.Implement restrictive intravenous fluid administration 19. Sham feeding (chewing sugar-free gum for at least 10 min three to four times per day) 20. Provide health education before discharge |

POD postoperative day.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart of patients enrolled in this study. PSM propensity score matching.

Definitions and observation indices

Tumor location was defined in accordance with the Japanese definition of three regions of the stomach (upper-third, middle-third, and lower-third)14. In cases involving multiple gastric sections, the affected portions were documented in descending order by the level of involvement, with the portion containing the majority of the tumor listed first. Pathological staging was classified in accordance with the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System for gastric cancer22,23. POCs were recorded and graded in accordance with the Clavien–Dindo classification, a widely validated and accepted standardized method for assessing POCs in various surgical procedures24–26. In patients who experienced multiple complications, the stage was determined by the highest grade of POCs. All POCs were considered overall POCs (Clavien–Dindo grade I–V); grade ≥ III POCs were classified as severe POCs18,27. Bowel function recovery was assessed as the time to the first passage of flatus and the initiation of a soft diet28,29.

The primary outcome was POCs, with secondary outcomes of times to first flatus, first liquid intake, and first soft food intake, and nutritional markers (serum albumin and total protein) on postoperative day 7, postoperative hospital stay, and mortality and 30-day readmission rates.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 statistical software. All figures were created using GraphPad Prism version 8.0. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentages (%), and group comparisons were made using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables with normal distributions were described as mean ± standard deviation, non-normal distributions were reported as median (interquartile range), and group comparisons were performed using Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney U test. Multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was used to assess the independent risk factors for POCs, and the results were presented as odds with 95% confidence intervals. To minimize bias from baseline information and potential confounding factors, propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was performed to obtain matched data. The nearest neighbor matching algorithm was used without replacement for 1:1 matching, and the caliper was set at 0.1 standard deviations. A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

This study received approval from the ethics committee of Fujian Cancer Hospital, and all procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the institution. Consent was provided by all participants after they were fully informed of the study protocol.

Results

POCs and clinicopathological characteristics

A total of 1349 patients who underwent gastrectomy met the eligibility criteria. These patients are divided into a DG group (n = 776) and TG group (n = 573). The overall POCs rate was 21.9% (296/1349), and severe POCs occurred in 131/1349 patients (9.7%).

Risk factors associated with POCs

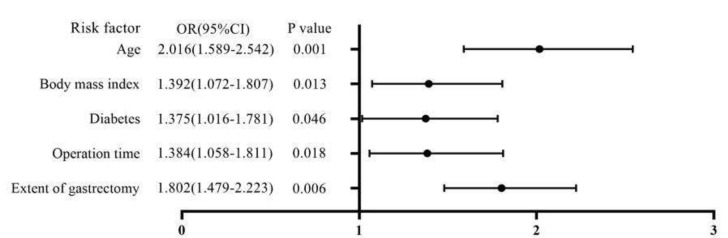

The POCs and clinicopathological factors are presented in Table 2. For the entire cohort, age, body mass index, diabetes, operation time, and extent of gastrectomy were significantly correlated with overall POCs (all, P < 0.05). Variables in the univariable analysis that showed statistical significance were included as covariates in the multivariable analysis. Age, body mass index, diabetes, operation time, and extent of gastrectomy were identified as independent risk factors for overall POCs in the multivariable analysis (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with or without POCs.

| Variable | With POCs (N = 296) | Without POCs (N = 1053) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.000 | ||

| < 65 | 142 | 629 | |

| ≥ 65 | 154 | 424 | |

| Gender | 0.482 | ||

| Male | 190 | 699 | |

| Female | 106 | 354 | |

| Education | 0.610 | ||

| < High school | 235 | 850 | |

| ≥ High school | 61 | 203 | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.343 | ||

| Married | 236 | 865 | |

| Spinsterhood/divorced/widowed | 60 | 188 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.014 | ||

| < 24 | 139 | 579 | |

| ≥ 24 | 157 | 474 | |

| Previous abdominal operation | 0.093 | ||

| Yes | 61 | 173 | |

| No | 235 | 880 | |

| Smoking history | 0.091 | ||

| Yes | 83 | 245 | |

| No | 213 | 808 | |

| Alcohol history | 0.251 | ||

| Yes | 91 | 288 | |

| No | 205 | 765 | |

| Diabetes | 0.006 | ||

| Yes | 75 | 191 | |

| No | 221 | 862 | |

| Hypertension | 0.159 | ||

| Yes | 88 | 270 | |

| No | 208 | 783 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.418 | ||

| Yes | 75 | 243 | |

| No | 221 | 810 | |

| Tumor location | 0.057 | ||

| Upper-third | 77 | 271 | |

| Middle-third | 108 | 315 | |

| Lower-third | 111 | 467 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.047 | ||

| < 5 | 144 | 581 | |

| ≥ 5 | 152 | 472 | |

| ASA-classification | 0.078 | ||

| ASA I | 198 | 770 | |

| ASA II | 63 | 194 | |

| ASA III | 35 | 89 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.297 | ||

| Yes | 86 | 274 | |

| No | 210 | 779 | |

| Preoperative hemoglobin, g/L, mean (SD) | 127.6 ± 19.3 | 126.2 ± 17.8 | 0.234 |

| Preoperative WBC, × 109/L, mean (SD) | 6.6 ± 1.9 | 6.7 ± 2.0 | 0.488 |

| Preoperative albumin, g/L, median (IQR) | 37.9 (35.0, 43.2) | 38.0 (34.9,43.6) | 0.462 |

| Preoperative BUN, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 0.545 |

| Preoperative total bilirubin, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 13.7 ± 4.2 | 13.6 ± 4.1 | 0.717 |

| Operation method | 0.131 | ||

| Laparoscopy | 145 | 568 | |

| Open | 151 | 485 | |

| Operation time (h) | 0.012 | ||

| < 4 | 174 | 702 | |

| ≥ 4 | 122 | 351 | |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 0.157 | ||

| < 200 | 124 | 490 | |

| ≥ 200 | 172 | 563 | |

| Histological type | 0.732 | ||

| Well/moderately | 68 | 252 | |

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 228 | 801 | |

| Extent of gastrectomy | 0.000 | ||

| DG | 137 | 628 | |

| TG | 159 | 425 | |

| Extent of lymph node dissection | 0.596 | ||

| Less than D2 | 49 | 161 | |

| D2 or more | 247 | 892 | |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 0.246 | ||

| Yes | 64 | 196 | |

| No | 232 | 857 | |

| Type of reconstruction | 0.785 | ||

| Roux-en-Y | 209 | 764 | |

| Billroth II | 29 | 100 | |

| Billroth II with Braun anastomosis | 58 | 189 | |

| Reconstruction method | 0.588 | ||

| Intracorporeal | 33 | 106 | |

| Extracorporeal | 263 | 947 | |

| Number of excised lymph nodes, median (IQR) | 33 (24, 42) | 31 (23, 40) | 0.068 |

| pTNM stagea | 0.104 | ||

| I | 68 | 244 | |

| II | 64 | 173 | |

| III | 164 | 636 | |

POCs postoperative complications, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range, WBC white blood cell count, BUN blood urea nitrogen, TG total gastrectomy, DG distal gastrectomy.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients before and after matching

Age, hypertension, tumor location, preoperative albumin, operation method, operation time, and number of excised lymph nodes differed significantly between the DG group and TG group in the unmatched analysis. After 1:1 PSM, 495 pairs of patients were successfully matched. All baseline characteristics except tumor location were well-balanced between the groups after matching (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical characteristics between the DG group and TG group before and after propensity score matching.

| Variable | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DG group (N = 765) | TG group (N = 584) | P value | DG group (N = 495) | TG group (N = 495) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.011 | 0.201 | ||||

| < 65 | 460 | 311 | 284 | 264 | ||

| ≥ 65 | 305 | 273 | 211 | 231 | ||

| Gender | 0.551 | 0.893 | ||||

| Male | 499 | 390 | 330 | 332 | ||

| Female | 266 | 194 | 165 | 163 | ||

| Education | 0.286 | 0.262 | ||||

| < High school | 623 | 462 | 405 | 391 | ||

| ≥ High school | 142 | 122 | 90 | 104 | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.708 | 0.631 | ||||

| Married | 637 | 474 | 395 | 401 | ||

| Spinsterhood/divorced/widowed | 138 | 110 | 100 | 94 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.521 | 0.849 | ||||

| < 24 | 413 | 305 | 261 | 258 | ||

| ≥ 24 | 352 | 279 | 234 | 237 | ||

| Previous abdominal operation | 0.207 | 0.416 | ||||

| Yes | 124 | 110 | 88 | 98 | ||

| No | 641 | 474 | 407 | 397 | ||

| Smoking history | 0.305 | 0.770 | ||||

| Yes | 178 | 150 | 123 | 127 | ||

| No | 587 | 434 | 372 | 368 | ||

| Alcohol history | 0.387 | 0.358 | ||||

| Yes | 222 | 157 | 146 | 133 | ||

| No | 543 | 427 | 349 | 362 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.503 | 0.270 | ||||

| Yes | 146 | 120 | 94 | 108 | ||

| No | 619 | 464 | 401 | 387 | ||

| Hypertension | 0.034 | 0.199 | ||||

| Yes | 186 | 172 | 126 | 144 | ||

| No | 579 | 412 | 369 | 351 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 0.342 | 0.229 | ||||

| Yes | 173 | 145 | 107 | 123 | ||

| No | 592 | 439 | 388 | 372 | ||

| Tumor location | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Upper-third | 0 | 348 | 0 | 287 | ||

| Middle-third | 187 | 236 | 112 | 208 | ||

| Lower-third | 578 | 0 | 383 | 0 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.518 | 0.278 | ||||

| < 5 | 417 | 308 | 276 | 259 | ||

| ≥ 5 | 348 | 276 | 219 | 236 | ||

| ASA-classification | 0.375 | 0.315 | ||||

| ASA I | 559 | 409 | 361 | 344 | ||

| ASA II | 142 | 115 | 94 | 98 | ||

| ASA III | 64 | 60 | 40 | 53 | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.311 | 0.722 | ||||

| Yes | 196 | 164 | 133 | 138 | ||

| No | 569 | 420 | 362 | 357 | ||

| Preoperative hemoglobin, g/L, mean (SD) | 126.7 ± 18.6 | 126.2 ± 17.5 | 0.616 | 127.4 ± 18.5 | 126.6 ± 17.7 | 0.491 |

| Preoperative WBC, × 109/L (median [IQR]) | 6.7 ± 1.9 | 6.6 ± 2.0 | 0.842 | 6.7 ± 2.0 | 6.6 ± 1.9 | 0.817 |

| Preoperative albumin, g/L, median (IQR) | 37.8 (34.5, 43.2) | 38.3 (35.4, 43.5) | 0.036 | 38.2(35.3,43.2) | 38.0(35.0,43.2) | 0.980 |

| BUN, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 0.758 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 6.1 ± 1.0 | 0.638 |

| Preoperative total bilirubin, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 13.6 ± 4.2 | 13.5 ± 4.1 | 0.886 | 13.5 ± 4.1 | 13.6 ± 4.1 | 0.538 |

| Operation method | 0.040 | 0.144 | ||||

| Laparoscopy | 423 | 290 | 267 | 244 | ||

| Open | 342 | 294 | 228 | 251 | ||

| Operation time (min) | 0.047 | 0.166 | ||||

| < 4 | 514 | 362 | 324 | 303 | ||

| ≥ 4 | 251 | 222 | 171 | 192 | ||

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 0.279 | 0.898 | ||||

| < 200 | 358 | 256 | 226 | 224 | ||

| ≥ 200 | 407 | 328 | 269 | 271 | ||

| Histological type | 0.399 | 0.258 | ||||

| Well/moderately | 188 | 132 | 122 | 107 | ||

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 577 | 452 | 373 | 388 | ||

| Extent of lymph node dissection | 0.553 | 0.932 | ||||

| Less than D2 | 123 | 87 | 83 | 82 | ||

| D2 or more | 642 | 497 | 412 | 413 | ||

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 0.146 | 0.268 | ||||

| Yes | 137 | 123 | 93 | 107 | ||

| No | 628 | 461 | 402 | 388 | ||

| Reconstruction method | 0.610 | 0.761 | ||||

| Intracorporeal | 76 | 63 | 53 | 56 | ||

| Extracorporeal | 689 | 521 | 442 | 439 | ||

| Number of excised lymph nodes, median (IQR) | 30 (22, 38) | 33 (25, 43) | 0.000 | 33 (26, 40) | 33 (25, 41) | 0.743 |

| pTNM stagea | 0.144 | 0.120 | ||||

| I | 174 | 138 | 128 | 111 | ||

| II | 148 | 89 | 98 | 83 | ||

| III | 443 | 357 | 269 | 301 | ||

PSM propensity score matching, TG total gastrectomy, DG distal gastrectomy, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range, WBC white blood cell count, BUN blood urea nitrogen.

aIn accordance with the Eighth American Joint Committee on Cancer classification.

Postoperative outcomes

Compared with the TG group, patients in the DG group had significantly earlier days to first flatus and eating a soft diet, and shorter postoperative hospital stays (P < 0.05). Compared with the DG group, the TG group had higher rates of overall POCs and severe POCs (P < 0.05). In contrast, no significant differences were identified between the groups for the number of days to eating a liquid diet, mortality rate, nutritional markers on postoperative day 7 and the rate of readmission owing to complications within 30 days after discharge (P > 0.05). Table 4 summarizes the postoperative outcomes.

Table 4.

Comparison of postoperative outcomes after matching.

| Variable | DG group (n = 495) | TG group (n = 495) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days of first flatust, days, mean (SD) | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 0.007 |

| Days of eating a liquid diet, days, mean (SD) | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.097 |

| Days of eating a soft diet, days, mean (SD) | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 0.000 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, days, mean (SD) | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 8.8 ± 0.9 | 0.000 |

| Overall POCs | 0.000 | ||

| Yes | 114 | 165 | |

| No | 382 | 330 | |

| Severe POCs | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 35 | 67 | |

| No | 460 | 428 | |

| Mortality | 0.478 | ||

| Yes | 3 | 5 | |

| No | 492 | 490 | |

| Readmissiona | 0.390 | ||

| Yes | 15 | 20 | |

| No | 480 | 475 | |

| Total protein postoperative day 7, g/L, median (IQR) | 67.3 (62.4, 73.3) | 66.1 (61.3, 71.1) | 0.052 |

| Albumin on postoperative day 7, g/L, median (IQR) | 39.5 (35.7, 45.8) | 38.6 (35.6, 43.5) | 0.058 |

TG total gastrectomy, DG distal gastrectomy, SD standard deviation, POCs postoperative complications.

aReadmission owing to complications within 30 days after discharge.

Subgroup analysis

Table 5 shows that, compared with the DG group, the TG group experienced higher rates of overall POCs and severe POCs, as well as longer postoperative hospital stays in all subgroups (P < 0.05).

Table 5.

Subgroup analyses of postoperative outcomes between the DG group and TG group.

| Patients | Overall POCs | Severe POCs | Hospital stay(days) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | P value | No. | P value | P value | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| < 65 | DG | 284 | 58 | 0.004 | 21 | 0.024 | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 0.001 |

| TG | 264 | 82 | 35 | 8.8 ± 0.9 | ||||

| ≥ 65 | DG | 211 | 56 | 0.034 | 14 | 0.013 | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 0.005 |

| TG | 231 | 83 | 32 | 8.8 ± 1.0 | ||||

| Operation method | ||||||||

| Laparoscopy | DG | 267 | 61 | 0.034 | 18 | 0.022 | 8.6 ± 0.8 | 0.015 |

| TG | 244 | 76 | 31 | 8.8 ± 0.9 | ||||

| Open | DG | 228 | 53 | 0.003 | 17 | 0.016 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 0.000 |

| TG | 251 | 89 | 36 | 8.8 ± 1.0 | ||||

| Tumor location | ||||||||

| Upper-third | DG | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| TG | 287 | 80 | 39 | 8.8 ± 0.9 | ||||

| Middle-third | DG | 112 | 18 | 0.000 | 6 | 0.025 | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 0.002 |

| TG | 208 | 85 | 28 | 8.8 ± 0.8 | ||||

| Lower-third | DG | 383 | 96 | – | 29 | – | 8.5 ± 0.8 | – |

| TG | 0 | – | – | – | ||||

TG total gastrectomy, DG distal gastrectomy, POCs postoperative complications.

Discussion

Despite remarkable advancements in perioperative care, and surgical and anesthetic procedures, gastrectomy is still associated with a high percentage of POCs. In this study, of the 1349 enrolled patients, 296 (21.9%) had POCs, and 131 (9.7%) had severe POCs. POCs rates varied widely in previous studies. Kurokawa et al.30 demonstrated that the POCs incidence was 12.2% in 1456 patients with pT2–T4 gastric cancer. Liu et al.31 reported a POCs rate of 27.8% after gastric cancer resection. Kurita et al.32 showed that the overall morbidity rate in the DG population was 18.3%. Goglia et al.33 reported an overall POCs rate of 33.0%, with 17.0% of the patients having a complication classified as Clavien–Dindo grade ≥ III. The reasons for this variability in POCs rates may be differences in the definitions of POCs, type of gastrectomy, ethnic group, clinicopathological characteristics, and surgeons’ experience.

POCs are a crucial aspect in evaluating the safety and technical viability of an operation. Undoubtedly, POCs can seriously prolong postoperative recovery, increase length of hospital stay and costs, delay the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy, and affect patients’ quality of life34. Moreover, POCs adversely influence recurrence and long-term survival, even if the tumor is resected curatively26,27,35–38. Given the high incidence and considerable impact of POCs, we evaluated POCs as the primary outcome in this study. Multivariate analysis revealed that TG was an independent risk factor for overall POCs, consistent with findings in previous studies35,39,40.

In our study, differences were observed between the DG and TG groups for age, hypertension, tumor location, preoperative albumin, operation method, operation time, and number of excised lymph nodes, before matching. In previous studies, age, preoperative albumin, operation method, and operation time were identified as factors influencing the postoperative recovery time of patients with gastric cancer35,41–44. We used PSM analysis to minimize selection bias and confounding, in this study. After PSM, the baseline characteristics were comparable between the two groups, except for tumor location. Because we performed DG and TG for patients with lower-third and upper-third gastric cancer, respectively, it was not possible to perform PSM analysis for tumor location. In this study, higher rates of both overall- and severe POCs were observed in the TG group compared with the DG group. Additionally, we found that DG patients experienced a significantly earlier onset of first flatus, started eating a soft diet sooner, and had shorter postoperative hospital stays compared with the TG group. These findings are attributed to the fact that the DG group experienced an earlier onset of first flatus, leading to a shorter time required to transition from a liquid diet to a soft diet.

With rapid advancements in laparoscopic instruments and techniques over the past decade, laparoscopic surgery has been widely adopted for the treatment of both early and advanced gastric cancer45–48. The scope of resection is no longer limited to DG49–51. Compared with open surgery, the laparoscopic approach offers several notable advantages, namely faster recovery, less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay, and comparable long-term oncological outcomes52–54. In this study, compared with the DG group, the TG group was consistently associated with a higher rate of overall POCs and longer postoperative hospital stay in the subgroup analyses based on the operation method.

Owing to small stomach volume, malabsorption, increased catabolism resulting from surgical stress, reduced physical activity, and other factors, many patients who undergo gastrectomy experience deficiencies in iron and/or vitamin B12, and malnutrition55–57. Previous retrospective studies have shown that DG is associated with better postoperative nutritional status compared with TG58–60. In this study, although total protein and albumin levels were lower in the TG group compared with the DG group, the differences were not statistically significant. This can be attributed to the fact that this study focused on short-term outcomes (to postoperative day 7). The human body has a certain amount of nutritional reserves, particularly in the liver and muscle tissues, which can sustain serum albumin and total protein levels for a short time after surgery. During the initial postoperative period, patients typically receive adequate perioperative nutritional support, which helps maintain a relatively stable nutritional status in the short-term and potentially masks early nutritional deficiencies.

While consensus guidelines for ERAS in gastrectomy patients were issued by the ERAS Society in 2014, ongoing debate and challenges persist in clinical surgical practice61. A multicenter study performed in Western populations revealed only moderate compliance with the ERAS protocols62. One possible reason is that the application of ERAS programs does not distinguish between TG and DG.

Compared with DG, TG remains a more challenging procedure owing to its higher technical complexity and the trauma associated with the excision of a greater number of lymph nodes and more tissue. This results in a postoperative inflammatory response, and occasional damage to blood vessels could lead to an increased risk of intra-abdominal bleeding after surgery18,63. Additionally, esophagojejunal anastomosis is a crucial step in TG. Reconstruction of the digestive tract in TG is performed in a limited operating space and involves deep anastomosis; therefore TG is more complex and challenging compared with the gastrojejunal anastomosis in DG. This is particularly true in patients with large amounts of visceral fat. Excessive pulling and tension on the anastomosis can lead to tearing and bleeding of the serosa64–66.

The extent of gastrectomy for resectable gastric cancer depends on the comprehensive consideration of tumor size, location, clinical stage, surgeons’ experience, and the distance from the proximal resection margin. Currently, consensus on the optimal extent of gastrectomy (total or subtotal) for middle-third gastric cancer is yet to be established67. Therefore, we performed subgroup analyses for middle-third gastric cancer. The results showed that the TG group experienced a higher rate of overall POCs and longer postoperative hospital stay, compared with the DG group. Similar results have been reported in previous studies that showed that DG is superior to TG when evaluating intraoperative and short-term outcomes17,65,66. Moreover, previous studies suggested that TG had a detrimental impact on patients’ long-term health-related quality of life and was associated with more post-gastrectomy symptoms at one or all time points, compared with DG19,20. We consider that DG is safe and reasonable for middle-third gastric cancer under the precondition of negative proximal resection margins.

There are several limitations in our study. First, compared with TG, DG for middle-third gastric cancer was associated with better short-term outcomes. However, comparisons of long-term survival rates, cancer recurrence rates, loss of body weight, physical activity, and quality of life were lacking. Second, although this study was performed at a high-volume center, this was s a single-center study comparing TG and DG, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, a large multicenter approach is necessary for further validation of our results. Finally, robotic computer-assisted platforms for gastric cancer were introduced at our institution in 2020, but only a small percentage of patients have been able to undergo robotic surgery owing to the high cost. Surgeons’ experience is an independent risk factor for POCs68. To reduce the occurrence of POCs that result from a lack of experience, surgeons should consider selecting patients who are in good health, during the surgeons’ initial stages of learning robotic gastrectomy. The exclusion criteria in this study included patients who had undergone robotic gastrectomy to mitigate bias in the study. However, it is important to note that this exclusion could potentially limit the generalizability of the study’s findings.

In conclusion, despite similar mortality and readmission rates compared with TG, DG offers the advantages of quicker bowel function recovery, fewer POCs, and a shorter hospital stay under ERAS. The ERAS guidelines for gastrectomy recommend an early postoperative oral diet regardless of the extent of gastric resection. However, it may be advisable to restart oral nutrition cautiously and gradually increase intake for patients who have undergone TG.

Acknowledgements

The authors express our gratitude to the patients, their families, and all the researchers involved in this study, for their valuable contribution and participation. They thank Jane Charbonneau, DVM, from Liwen Bianji (Edanz) (www.liwenbianji.cn) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Author contributions

M.F.Y. and Y.M.L. designed the study. M.F.Y., Z.Y.L, Y.P.X., H.Z.Z., Y.Z.P., and C.K.Y. collected and analyzed the data. Z.M.L. and Z.Y.L. wrote the manuscript. M.F.Y. and Z.Y.L. reviewed the manuscript. C.K.Y. and Y.M.L. prepared the figures. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Startup Fund for scientific research, Fujian Medical University (Grant Numbers: 2022QH1158, 2020QH1226) and the Fujian Cancer Hospital Project (Grant Number: 2024YN01) and was sponsored by the Fujian Provincial Health Technology Project (Grant Number: 2022TG016).

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zhenmeng Lin, Mingfang Yan and Zhaoyan Lin.

Contributor Information

Yangming Li, Email: lym@fjzlhospital.com.

Chunkang Yang, Email: chuck330@163.com.

References

- 1.Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71, 209–249 (2021). 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang, W. J. et al. Updates on global epidemiology, risk and prognostic factors of gastric cancer. World J. Gastroenterol.29, 2452–2468 (2023). 10.3748/wjg.v29.i16.2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosa, F. et al. The role of surgery in the management of gastric cancer: State of the art. Cancers14, 5542 (2022). 10.3390/cancers14225542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brisinda, G. et al. Postoperative mortality and morbidity after D2 lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer: A retrospective cohort study. World J. Gastroenterol.28, 381–398 (2022). 10.3748/wjg.v28.i3.381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coimbra, F. et al. Predicting overall and major postoperative morbidity in gastric cancer patients. J. Surg. Oncol.120, 1371–1378 (2019). 10.1002/jso.25743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisarska, M. et al. Laparoscopic gastrectomy with enhanced recovery after surgery protocol: Single-center experience. Med. Sci. Monit.23, 1421–1427 (2017). 10.12659/MSM.898848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fumagalli Romario, U. et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery in gastric cancer: Which are the main achievements from the Italian experience. Updates Surg.70, 257–264 (2018). 10.1007/s13304-018-0522-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosa, F. et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) versus standard recovery for gastric cancer patients: The evidences and the issues. Surg. Oncol.41, 101727 (2022). 10.1016/j.suronc.2022.101727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeong, O., Jang, A., Jung, M. R., Kang, J. H. & Ryu, S. Y. The benefits of enhanced recovery after surgery for gastric cancer: A large before-and-after propensity score matching study. Clin. Nutr.40, 2162–2168 (2021). 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, J. et al. Evaluation of the application of laparoscopy in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) for gastric cancer: A Chinese multicenter analysis. Ann. Transl. Med.8, 543 (2020). 10.21037/atm-20-2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roh, C. K., Son, S. Y., Lee, S. Y., Hur, H. & Han, S. U. Clinical pathway for enhanced recovery after surgery for gastric cancer: A prospective single-center phase II clinical trial for safety and efficacy. J. Surg. Oncol.121, 662–669 (2020). 10.1002/jso.25837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian, Y., Li, Q. & Pan, Y. Prospective study of the effect of ERAS on postoperative recovery and complications in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer Biol. Med.19, 1274–1281 (2021). 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2021.0108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao, S. M., Ma, H. L., Xu, R., Yang, C. & Ding, Z. Enhanced recovery after surgery protocol for elderly gastric cancer patients: A prospective study for safety and efficacy. Asian J. Surg.45, 2168–2171 (2022). 10.1016/j.asjsur.2021.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association jgca@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2021 (6th edition). Gastric Cancer26, 1–25 (2023). 10.1007/s10120-022-01331-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, K. et al. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A comparative study with laparoscopic distal gastrectomy at a high-volume center. Minim. Invas. Ther. Allied Technol.27, 164–170 (2018). 10.1080/13645706.2017.1350718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, W. J. et al. A propensity score-matched comparison of laparoscopic distal versus total gastrectomy for middle-third advanced gastric cancer. Int. J. Surg.60, 194–203 (2018). 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Jongh, C. et al. Distal versus total D2-gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A secondary analysis of surgical and oncological outcomes including quality of life in the multicenter randomized LOGICA-trial. J. Gastrointest. Surg.27, 1812–1824 (2023). 10.1007/s11605-023-05683-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, W. J. et al. Systematic assessment of complications after robotic-assisted total versus distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: A retrospective propensity score-matched study using Clavien–Dindo classification. Int. J. Surg.71, 140–148 (2019). 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi, M. et al. Quality of life after total vs distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction: Use of the postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale-45. World J. Gastroenterol.23, 2068–2076 (2017). 10.3748/wjg.v23.i11.2068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu, J. et al. Long-term health-related quality of life in patients with gastric cancer after total or distal gastrectomy: A propensity score-matched cohort study. Int. J. Surg.109(11), 3283–3293 (2023). 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lombardi, P. M. et al. ERAS pathway for gastric cancer surgery: Adherence, outcomes and prognostic factors for compliance in a Western centre. Updates Surg.73, 1857–1865 (2021). 10.1007/s13304-021-01093-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.In, H. et al. Validation of the 8th Edition of the AJCC TNM staging system for gastric cancer using the national cancer database. Ann. Surg. Oncol.24, 3683–3691 (2017). 10.1245/s10434-017-6078-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu, J. et al. The effectiveness of the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classification in the prognosis evaluation of gastric cancer patients: A comparative study between the 7th and 8th editions. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol.43, 2349–2356 (2017). 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hébert, M. et al. Standardizing postoperative complications-validating the Clavien–Dindo complications classification in cardiac surgery. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.33, 443–451 (2021). 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2020.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolliger, M. et al. Experiences with the standardized classification of surgical complications (Clavien–Dindo) in general surgery patients. Eur. Surg.50, 256–261 (2018). 10.1007/s10353-018-0551-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, S. S. et al. Impact of postoperative complication and completion of multimodality therapy on survival in patients undergoing gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer. J. Am. Coll. Surg.230, 912–924 (2020). 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Z. et al. Severity of complications and long-term survival after laparoscopic total gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for advanced gastric cancer: A propensity score-matched, case-control study. Int. J. Surg.54, 62–69 (2018). 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palumbo, V. et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery pathway in patients undergoing open radical cystectomy is safe and accelerates bowel function recovery. Urology115, 125–132 (2018). 10.1016/j.urology.2018.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, K. Y. et al. The effect of intraoperative fluid management according to stroke volume variation on postoperative bowel function recovery in colorectal cancer surgery. J. Clin. Med.10, 1857 (2021). 10.3390/jcm10091857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurokawa, Y. et al. Prognostic value of postoperative C-reactive protein elevation versus complication occurrence: A multicenter validation study. Gastric Cancer23, 937–943 (2020). 10.1007/s10120-020-01073-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, Z. J. et al. Postoperative decrease of serum albumin predicts short-term complications in patients undergoing gastric cancer resection. World J. Gastroenterol.23, 4978–4985 (2017). 10.3748/wjg.v23.i27.4978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurita, N. et al. Risk model for distal gastrectomy when treating gastric cancer on the basis of data from 33,917 Japanese patients collected using a nationwide web-based data entry system. Ann. Surg.262, 295–303 (2015). 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goglia, M. et al. Complication of gastric cancer surgery: A single centre experience. In Vivo37, 2166–2172 (2023). 10.21873/invivo.13315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanda, M. Preoperative predictors of postoperative complications after gastric cancer resection. Surg. Today50, 3–11 (2020). 10.1007/s00595-019-01877-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu, F. et al. Prognostic significance of postoperative complication after curative resection for patients with gastric cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther.16, 1611–1616 (2020). 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_856_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tokunaga, M. et al. Impact of postoperative complications on survival outcomes in patients with gastric cancer: Exploratory analysis of a randomized controlled JCOG1001 trial. Gastric Cancer24, 214–223 (2021). 10.1007/s10120-020-01102-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakazawa, N. et al. Preoperative risk factors and prognostic impact of postoperative complications associated with total gastrectomy. Digestion103, 397–403 (2022). 10.1159/000525356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aurello, P. et al. Impact of anastomotic leakage on overall and disease-free survival after surgery for gastric carcinoma: A systematic review. Anticancer Res.40, 619–624 (2020). 10.21873/anticanres.13991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura, N. et al. Risk factors for overall complications and remote infection after gastrectomy in elderly gastric cancer patients. In Vivo35, 2917–2921 (2021). 10.21873/invivo.12582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujiya, K. et al. Preoperative risk factors for postoperative intra-abdominal infectious complication after gastrectomy for gastric cancer using a Japanese web-based nationwide database. Gastric Cancer24, 205–213 (2021). 10.1007/s10120-020-01083-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shao, J. et al. Factors influencing postoperative recovery time of patients with gastric cancer. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech.33, 370–374 (2023). 10.1097/SLE.0000000000001184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caruso, S. et al. Laparoscopic vs open gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer: A propensity score-matched retrospective case-control study. Curr. Oncol.29, 1840–1865 (2022). 10.3390/curroncol29030151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu, H. et al. Risk factors and prognostic impact of postoperative complications in patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Curr. Oncol.29, 6496–6507 (2022). 10.3390/curroncol29090511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang, W. Q. et al. Preoperative albumin levels predict prolonged postoperative ileus in gastrointestinal surgery. World J. Gastroenterol.26, 1185–1196 (2020). 10.3748/wjg.v26.i11.1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeong, S. A. et al. Comparing surgical and oncologic outcomes between laparoscopic gastrectomy and open gastrectomy in advanced gastric cancer with serosal invasion: A retrospective study with propensity score matching. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol.48, 1988–1993 (2022). 10.1016/j.ejso.2022.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, W., Huang, Z., Zhang, J. & Che, X. Long-term and short-term outcomes after laparoscopic versus open surgery for advanced gastric cancer: An updated meta-analysis. J. Minim. Access Surg.17, 423–434 (2021). 10.4103/jmas.JMAS_219_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khaled, I., Priego, P., Soliman, H., Faisal, M. & Saad Ahmed, I. Oncological outcomes of laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced gastric cancer: A retrospective multicenter study. World J. Surg. Oncol.19, 206 (2021). 10.1186/s12957-021-02322-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hyung, W. J. et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer: The KLASS-02-RCT randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol.38, 3304–3313 (2020). 10.1200/JCO.20.01210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Challine, A. et al. Postoperative outcomes after laparoscopic or open gastrectomy. A national cohort study of 10,343 patients. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol.47, 1985–1995 (2021). 10.1016/j.ejso.2021.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu, D. et al. Short-term outcomes and prognosis of laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy in elderly patients with stomach cancer. Surg. Endosc.34, 5428–5438 (2020). 10.1007/s00464-019-07338-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Illuminati, G. et al. Laparoscopy-assisted vs open total gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for advanced gastric cancer: Results of a retrospective, multicenter study. Updates Surg.75, 1645–1651 (2023). 10.1007/s13304-023-01476-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsui, R., Inaki, N. & Tsuji, T. Impact of laparoscopic gastrectomy on relapse-free survival for locally advanced gastric cancer patients with sarcopenia: A propensity score matching analysis. Surg. Endosc.36, 4721–4731 (2022). 10.1007/s00464-021-08812-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trastulli, S. et al. Laparoscopic compared with open D2 gastrectomy on perioperative and long-term, stage-stratified oncological outcomes for gastric cancer: A propensity score-matched analysis of the IMIGASTRIC database. Cancers13, 4526 (2021). 10.3390/cancers13184526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mao, X. Y. et al. Comparison of long-term oncologic outcomes laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy and open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Langenbecks Arch. Surg.406, 437–447 (2021). 10.1007/s00423-020-01996-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lim, C. H. et al. Anemia after gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: Long-term follow-up observational study. World J. Gastroenterol.18, 6114–6119 (2012). 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park, S. H. et al. Totally laparoscopic versus laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy: The KLASS-07, a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Surg.1, 10 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park, S. H. et al. Reappraisal of optimal reconstruction after distal gastrectomy—A study based on the KLASS-07 database. Int. J. Surg.110, 32–44 (2024). 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu, H. et al. Feasibility and nutritional impact of laparoscopic assisted tailored subtotal gastrectomy for middle-third gastric cancer. World J. Gastroenterol.26, 6837–6852 (2020). 10.3748/wjg.v26.i43.6837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Segami, K. et al. Risk factors for severe weight loss at 1 month after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Asian J. Surg.41, 349–355 (2018). 10.1016/j.asjsur.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakazono, M. et al. Comparison of the dietary intake loss between total and distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. In Vivo35, 2369–2377 (2021). 10.21873/invivo.12514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mortensen, K. et al. Consensus guidelines for enhanced recovery after gastrectomy: Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations. Br. J. Surg.101, 1209–1229 (2014). 10.1002/bjs.9582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gianotti, L. et al. Association between compliance to an enhanced recovery protocol and outcome after elective surgery for gastric cancer. Results from a western population-based prospective multicenter study. World J. Surg.43, 2490–2498 (2019). 10.1007/s00268-019-05068-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kawamura, H. et al. Anastomotic complications after laparoscopic total gastrectomy with esophagojejunostomy constructed by circular stapler (OrVil(™)) versus linear stapler (overlap method). Surg. Endosc.31, 5175–5182 (2017). 10.1007/s00464-017-5584-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Duan, W. et al. Semi-end-to-end esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy better reduces stricture and leakage than the conventional end-to-side procedure: A retrospective study. J. Surg. Oncol.116, 177–183 (2017). 10.1002/jso.24637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiang, Y. et al. Surgical and oncological outcomes of distal gastrectomy compared to total gastrectomy for middle-third gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol. Lett.24, 291 (2022). 10.3892/ol.2022.13411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li, Z., Bai, B., Xie, F. & Zhao, Q. Distal versus total gastrectomy for middle and lower-third gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg.53, 163–170 (2018). 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.03.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamamoto, M., Yamanaka, T., Baba, H., Kakeji, Y. & Maehara, Y. The postoperative recurrence and the occurrence of second primary carcinomas in patients with early gastric carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol.97, 231–235 (2008). 10.1002/jso.20946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li, Z. Y. et al. Comparison of the postoperative complications between robotic total and distal gastrectomies for gastric cancer using Clavien–Dindo classification: A propensity score-matched retrospective cohort study of 726 patients. Surg. Innov.29, 608–615 (2022). 10.1177/15533506211047011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.