Abstract

Study Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Objective

To evaluate the cross-cultural adaptability and internal consistency of the Chinese version of the Quality-of-Life Profile for Spine Deformities (QLPSD) questionnaire in mainland China.

Methods

The original QLPSD was translated from Spanish into Chinese with proper cross-cultural adaptation based on the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guidelines. A total of 129 AIS patients referring to our institution from February 2021 to January 2022 were enrolled in this study. The effects of ceiling and floor were evaluated and the reliability was verified by examining the internal consistency (the Cronbach’s α coefficient). Interclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was used to test and retest reliability. The C-QLPSD dimensions were compared with the domains in Chinese version of 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and Scoliosis Research Society-22 (SRS-22) questionnaires using Pearson correlation coefficient to assess the concurrent validity.

Results

No significant floor and ceiling effects in C-QLPSD was observed. The total Cronbach’s α was estimated at .914, ranging from .768 in back pain dimensions to .862 in psychosocial function dimensions. The C-QLPSD dimensions indicated satisfactory test-retest reliability with ICC range of .784-.870. Construct validity analysis revealed that C-QLPSD was well correlated with SRS-22 and SF-36. The values of total correlation coefficient were calculated at -.924 and -.871, respectively, which were both statistically significant (P < .05).

Conclusion

The adapted Chinese version of QLPSD had good internal consistency and excellent test-retest reliability, which can be used to assess the outcome among Chinese-speaking patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.

Keywords: idiopathic scoliosis, quality of life profile for spine deformities, Chinese, reliability, validity

Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is the most common form of scoliosis, affecting 1-3% of children and adolescents aged 10-16 years. 1 Patients with AIS are influenced by body image concerns, mental well-being, back-related problems such as pain and stiffness, and social and psychological consequences, all of which can reduce quality of life.2,3 Therefore, to better understand the problems of this population and to improve their performance and quality of life, increasing attention has been paid to the subjective views of the patient about their own health-related quality of life using patient-reported outcome measures and questionnaires.4-7

The Quality of Life Profile for Spine Deformities (QLPSD), developed by Climent et al in Spain, was the first questionnaire specifically designed to assess quality of life in adolescents with spinal deformities. 8 In recent years, the original Spanish QLPSD has been cross-culturally adapted into English, 8 French, 9 German, 10 Persian 11 and Korean 12 versions and all have been shown to display good score distribution, excellent reliability, and construct validity. Thus far, the QLPSD has not been verified in Chinese culture. It has been recognized that cultural differences between nations may affect the cognitive processing of the items in the questionnaire. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to translate and cross-culturally adapt the QLPSD into a simplified Chinese version (C-QLPSD) and to analyze its reliability and validation in Chinese adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis.

Methods and Materials

Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation

The translation process was carried out according to the guideline issued by the American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) Outcomes committee and outlined by Beaton et al. 13 Two native Chinese translators independently translated the original Spanish QLPSD into Chinese. After comparing the two translators’ versions, discrepancies were identified and reconciled by consensus. Backward translations were separately made by two native Spanish translators without healthcare background and they had no reference to the original QLPSD. The back-translators were neither aware nor informed of the outcome measurement in this study. The prefinal version of the C-QLPSD was a consensus reached by an expert committee with three bilingual experts and three orthopedic surgeons. Afterwards, this prefinal version was given to 40 Chinese-speaking patients with AIS to test its acceptability. Their feedback was collected to develop the final version of the C-QLPSD, which was subjected to further psychometric testing.

Participants

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Second Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University (No. 82002369). Patients diagnosed with AIS were consecutively recruited to the study from the Spine Clinic of Second Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University from February 2021 to January 2022. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age between 10 and 18 years, (2) radiographically confirmed diagnosis of idiopathic scoliosis, (3) brace treatment more than two months, (4) capable of reading and writing Chinese. The exclusion criteria were (1) who were unable to read Chinese, (2) presence of any cord and vertebra anomaly as demonstrated on a whole spine magnetic resonance imaging, (3) history of previous spinal surgery. The patients’ demographic data including age, gender, height, weight, Risser stage and Cobb angle of the major curve were collected in the Spine Clinic. Meanwhile, the C-QLPSD was first completed by the included participants. To explore the adaptation of the C-QLPSD, test–retest reliability assessment was conducted. The patients were instructed to complete an identical questionnaire a second time by email in 2 weeks’ time. The QLPSD originally consists of 21 items in 5 dimensions. Dimensions and number of items in them are as follows: psychosocial function (7), sleep disturbances (4), back pain (3), body image (4), and back flexibility (3). The items are rated on a typical five-level Likert scale ranging from 1 (i.e., “Strongly disagree”) to 5 (i.e., “Strongly agree”). The results are expressed as the sum or mean (total sum of the dimension divided by the number of items answered) for each dimension, and a higher score indicates a poorer quality of life.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University before initiation, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Parents or guardians of all participants were required to sign an informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Regarding content analysis, for each item in the questionnaire, the mean, standard deviation, and range were calculated to determine the distributions and floor and ceiling effects. The floor and ceiling effects were considered to be significant if more than 15% of the subjects achieved the minimum or maximum score, respectively. 14 The internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, and >.8 were considered as good internal consistency. 14 Test–retest reliability was measured by comparing responses to the first and second administrations of C-QLPSD. It was assessed by the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). An ICC value between .7 and .8 indicates good reliability, and more than .8 indicated excellent reliability. 15 Construct validity was evaluated through a principal component analysis (PCA) using varimax rotation. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity were conducted prior to running the analysis. Also, the five dimensions of C-QLPSD were compared with relevant dimensions from well validated Chinese version of 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) 16 and Scoliosis Research Society-22 (SRS-22) 17 questionnaires. They were sent to the patients with C-QLPSD concomitantly. Correlation was made using Pearson correlation coefficients. A Pearson correlation coefficient of more than .75 was considered excellent, .5 to .75 as good, .25 to .5 as fair, and less than .25 as poor. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Mean values were reported with standard deviation (SD), and ICC values were presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

From February 2021 to January 2022, a total of 129 participants who met the inclusion criteria accepted to participate the study. The patients’ population included 94 (72.9%) females and 35 (27.1%) males with a mean age of 14.1 ± 2.7 years (range: 10-18). Clinical characteristics and demographics of the included patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics and Demographics of the Included Participants.

| Characteristics | N, % or mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14.1 ± 2.7 |

| Range | 10-18 |

| Gender | |

| Female (%) | 94(72.9%) |

| Male (%) | 35(27.1%) |

| Height(cm) | 158.2 ± 11.8 |

| Range | 136.4-177.6 |

| Body weight(kg) | 44.3 ± 8.8 |

| Range | 28.7-58.5 |

| Risser stage (N) | 1(16), 2(28), 3(41), 4(21), 5(23) |

| Curve type (N) | Major thoracic (79), Double major (32), Thoracolumbar/lumbar (18) |

| Cobb angle of major curve (°) | 33.4 ± 5.3 |

| Time to complete C-QLPSD (minutes) | 3.0 ± 1.4 |

| SRS-22 | |

| Function/activity | 4.20 ± .63 |

| Pain | 4.11 ± .65 |

| Self-image/appearance | 3.69 ± .69 |

| Mental health | 4.01 ± .67 |

| Satisfaction | 3.92 ± .72 |

| SF-36 | |

| Physical functioning | 82.60 ± 11.93 |

| Role-physical | 75.78 ± 22.95 |

| Bodily pain | 79.20 ± 13.62 |

| General health perceptions | 74.12 ± 15.02 |

| Vitality | 70.54 ± 16.88 |

| Social functioning | 86.14 ± 19.15 |

| Role-emotional | 85.53 ± 17.60 |

| Mental health index | 77.52 ± 11.45 |

SRS-22, Scoliosis Research Society-22; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey.

Cross-Cultural Adaptation

There were no major language problems occurred in the forward and backward translations process. Some minor differences were found in some items due to the cultural diversity and then adapted cross-culturally, such as item 15, Me da vergüenza que me vean en bañador. Swimming is not popular in China and some children misunderstand this question and think that not wearing a swimsuit is because of shyness, not because of the back problems. Therefore, the item was adapted to be I am ashamed of being seen on my back (e.g. in a dance suit or swimsuit). All of the patients were able to complete the questionnaire properly within five minutes without any difficulties, which indicated that the C-QLPSD was well cross-cultural inherited and easy to be understood.

Score Distribution

The distribution of scores for 5-dimension questionnaire was demonstrated in Table 2. The ceiling and the floor effects (<15%) for all dimensions were not observed. Item analysis proved the internal homogeneity of the construct as no item had an item-total correlation <.20. The values of skewness and kurtosis were <1.92 for each dimension, showing that all items had a normal distribution.

Table 2.

Score Distribution of the C-QLPSD.

| C-QLPSD dimension | Number of items | Mean (SD) | Range | Value of skewness | Value of kurtosis | Ceiling (%) | Floor (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 21 | 54.21(8.57) | 34-71 | −.132 | −.623 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychosocial function | 7 | 16.61(3.88) | 8-25 | −.141 | −.478 | 0 | 0 |

| Sleep disturbance | 4 | 9.04(2.25) | 4-15 | .126 | −.254 | 1.55 | 0 |

| Back pain | 3 | 5.73(1.32) | 3-8 | −.154 | −.675 | 4.65 | 0 |

| Body image | 4 | 15.27(2.14) | 9-20 | −.543 | .500 | 0 | .78 |

| Back flexibility | 3 | 7.48(1.56) | 3-11 | −.463 | .719 | 2.33 | 0 |

C-QLPSD, Chinese version of the Quality of Life Profile for Spine Deformities.

Reliability

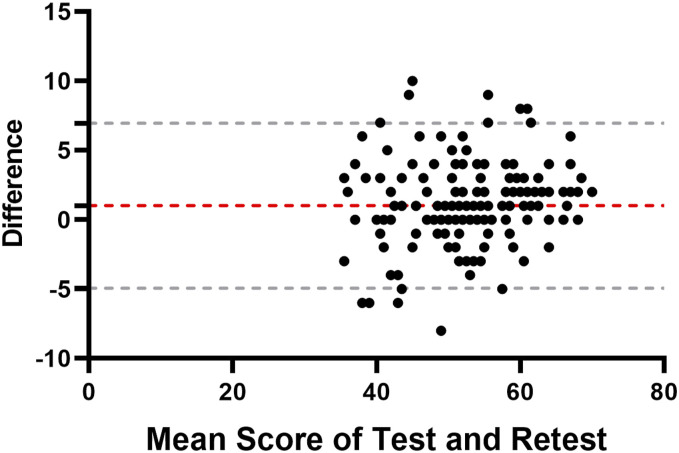

The internal consistency of the C-QLPSD was good with a Cronbach’s alpha of .914. The Cronbach’s alpha remained to be >.75 when each dimension was analyzed. There were strong correlations between each item and its corresponding dimension significantly. All participants completed the questionnaire a second time 7 to 14 days after the first evaluation. The test-retest reliability of C-QLPSD was also excellent. The total score of the questionnaire was 54.21 ± 8.57 in the first test and 52.62 ± 8.06 in the second test. The overall C-QLPSD and all dimensions scored good or excellent with ICC ranging from .784-.919 (Table 3). Bland and Altman plots for the two tests revealed no systematic bias, indicating good test-retest agreement and reproducibility of C-QLPSD (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Internal Consistency and Test-Retest Reliability of the Chinese Version of The Quality of Life Profile for Spine Deformities.

| Dimensions | Cronbach’s α | ICC (CIs range) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | .914 | .919(.865-.951) |

| Psychosocial function | .862 | .786(.705-.846) |

| Sleep disturbance | .844 | .814(.746-.865) |

| Back pain | .768 | .803(.730-.858) |

| Body image | .824 | .784(.630-.867) |

| Back flexibility | .799 | .870(.820-.906) |

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; CIs, confidence intervals.

Figure 1.

The Bland–Altman plot for test–retest agreement of the C-QLPSD. The grey dashed line indicates the 95% (±1.96 standard deviation) limits of agreement.

Validity

A group of orthopedic experts on spinal deformity management evaluated the content validity of the scale and agreed that the information derived from all items was adequate to assess quality of life of AIS patients. Therefore, no item was recommended to be added or removed.

The value of KMO test was .871 and the Bartlett’s test result was P < .000, indicating that the C-QLPSD could be performed by factor analyze for further analysis. PCA analysis suggested a 5-factor model, accounting for 65.62% of the total variance (37.20%, 9.42%, 7.23%, 6.42% and 5.36%, respectively). Figure 2 showed the scree plot of the eigenvalues. The factor structure was in accordance with the original questionnaire: the 1st factor (psychosocial function) included item 1 to 7; the 2nd factor (body image) included item 15 to 18; the 3rd factor (sleep disturbances) included item 8 to 11; the 4th factor (back flexibility) included item 19 to 21, and the 5th factor (back pain) included item 12 to 14. Detailed results are presented in Table 4.

Figure 2.

Scree plot to determine the number of factors to retain.

Table 4.

Principle Component Analysis for the Simplified Chinese Version of Quality of Life Profile for Spine Deformities.

| Items | Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 6 | .753 | ||||

| 1 | .750 | ||||

| 3 | .712 | ||||

| 5 | .699 | ||||

| 4 | .698 | ||||

| 7 | .680 | ||||

| 2 | .493 | ||||

| 17 | .795 | ||||

| 15 | .761 | ||||

| 18 | .708 | ||||

| 16 | .699 | ||||

| 10 | .794 | ||||

| 9 | .784 | ||||

| 8 | .714 | ||||

| 11 | .664 | ||||

| 19 | .846 | ||||

| 20 | .754 | ||||

| 21 | .727 | ||||

| 13 | .850 | ||||

| 12 | .696 | ||||

| 14 | .666 | ||||

Construct validity based on the comparison with SRS-22 and SF-36 was described in Table 5. The results revealed that C-QLPSD was well correlated with SRS-22 and SF-36. The values of total correlation coefficient were calculated at −.924 and −.871, respectively. Both correlations were statistically significant (P < .05). The Spearman correlations between the relevant SRS-20 domains and C-QLPSD dimensions ranged from -.805 to -.606 in psychosocial function, −.586 to −.287 in back pain, −.649 to −.427 in body image, −.632 to −.482 in back flexibility, and −.732 to −.458 in sleep disturbance. The Spearman correlations between the relevant SF-36 subscales and C-QLPSD dimensions ranged from −.693 to −.379 in psychosocial function, −.573 to −.314 in back pain, −.573 to −.343 in body image, −.487 to −.313 in back flexibility, and −.654 to −.354 in sleep disturbance. Overall, these results suggested satisfied divergent or discriminant validity for C-QLPSD.

Table 5.

Concurrent validity of C-QLPSD domains with relevant SF-36 and SRS-22 domains as determined by Pearson correlation coefficients.

| SF-36 domain | C-QLPSD domain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial function | Sleep disturbances | Back pain | Body image | Back flexibility | |

| Physical functioning | −.419 | −.413 | −.318 | −.343 | −.313 |

| Role-physical | −.573 | −.654 | −.549 | −.465 | −.419 |

| Bodily pain | −.379 | −.354 | −.314 | −.422 | −.325 |

| General health perceptions | −.693 | −.572 | −.470 | −.496 | −.439 |

| Vitality | -.634 | −.585 | −.386 | −.408 | −.432 |

| Social functioning | −.667 | −.646 | −.573 | −.519 | −.487 |

| Role-emotional | −.476 | −.445 | −.475 | −.453 | −.399 |

| Mental health index | −.540 | −.591 | −.406 | −.426 | −.412 |

| SRS-22 domain | |||||

| Function/activity | −.805 | −.732 | −.586 | −.649 | −.632 |

| Pain | −.657 | −.586 | −.461 | −.519 | −.490 |

| Self-image/appearance | −.689 | −.573 | −.501 | −.484 | −.500 |

| Mental health | −.634 | −.574 | −.486 | −.559 | −.496 |

| Satisfaction with management | −.606 | −.458 | −.287 | −.427 | −.482 |

SRS-22, Scoliosis Research Society-22; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; C-QLPSD, Chinese version of the Quality of Life Profile for Spine Deformities.

Discussion

Accumulated evidence suggested that AIS patients had worse quality of life than those without AIS, which was not only caused by the disease itself, but also caused by extended period of brace treatment or surgery.18-20 China has the largest population in the world and the incidence of AIS is 2.52-6.15%.21,22 Therefore, specific self-reported questionnaires used to evaluate quality of life of AIS patients have drawn increasing attention among orthopedic surgeons in mainland China. QLPSD was the first multidimensional questionnaire specifically designed and tested to evaluate the quality of life of patients with spinal deformities. And it has been proved to be a reliable and valid instrument in several countries.8,10-12 In the current study, we successfully produced a Chinese version of QLPSD to test its reliability and validity for Chinese-speaking patients with AIS. To the best of our knowledge, this research was the first large-scale study of cross-cultural and linguistic adaptation and validation of the QLPSD performed in a Chinese population.

As reported by Terwee et al, a sample size of at least 100 patients was adequate for the assessment of internal consistency. 14 One hundred and twenty nine Chinese-speaking patients were recruited in this study.

The translation process went exceptionally well. We have modified some ambiguous words and misleading terms in accordance with Chinese tradition. After the adaptation, all participants correctly understood the questionnaire and completed it within 5 minutes, which revealed good acceptability of C-QLPSD. The Chinese version of the QLPSD did not exhibit floor or ceiling effects in any of the dimensions, suggesting a generally satisfactory reliability. Item analysis revealed that no item was redundant in that all items had an item-total score correlation >.20. The scores of each item were distributed in a normal distribution, indicating that each item measured the range of possible states of the relevant question.

With regard to test/retest reliability, all participants completed the first questionnaire in the outpatient clinic and after 7-14 days, completed the second questionnaire at home via email. The overall ICC of the C-QLPSD was .919, which was comparable to the values of the Spanish version (.91) and Persian version (.91) and a little higher than that of German version (.84) and Korean version (.815). All dimensions had good or excellent ICC scores, ranging from .784 to .870, demonstrating satisfactory or excellent test/retest reproducibility.

The Cronbach’s α coefficient obtained from the C-QLPSD was .914, showing that this translated version was reliable. This was in line with previously reported results by others. The Cronbach's α value for the Spanish and Persian versions was .88,8,11 for the German version .93, 10 for the English version .91, 23 for the Korean version .918, 12 which further confirmed the reliability of QLPSD. Compared with the original Spanish version, the Cronbach’s α value for each dimension was higher, ranging from .768 to .862.

In the analysis for convergent validity, the C-QLPSD total score correlated significantly with the SRS-22 overall score (r = −.924), indicating the high validity of the questionnaire. In particular, the C-QLPSD pain subscale correlated well with the SRS-22 pain subscale (r = −.586), and the body image subscales correlated with an r = −.484. This was in agreement with the results reported by Climent et al, who noted a significant correlation coefficient between the QLPSD total score and the SRS-22 total score of .84. 24 Park et al reported that the correlations between back pain domain of QLPSD and pain domain of the SRS-22 (r = −.751), and between body image domain of QLPSD and self-image/appearance domain of SRS-22 (r = −.764) were expected to be stronger than other functional domains of the SRS-22. 12 Corresponding well with these data, Matamalas et al found a correlation of r = −.76 between the QLPSD body image subscale and the SRS-22 self-image subscale. 25 In addition, our study also showed a strong relationship existed between the total C-QLPSD and SF-36 score (r = −.871), which has never reported before.

Although the results have confirmed the validity and reliability of C-QLPSD, there were still some potential limitations of this study. First, some authors would suggested that a sample size of at least 250 was required for stable correlation analysis. 10 The sample in the present study was limited in size and all the participants were recruited in a single institution, which might limit the variety in patient population. Second, participants included in our study all had mild scoliosis with a mean Cobb angle of 33.4° and received non-surgical treatment. Whether C-QLPSD could be applied in surgically treated individuals with severe scoliosis need to explore further. Third, most patients were female because the adolescent idiopathic scoliosis was a female-predominant disease.

Conclusion

QLPSD was successfully translated and cross-culturally adapted for use in China with adequate transcultural adaptation, reliability, and validity. Therefore, we recommend that the C-QLPSD can be widely used for assessing the effect of scoliosis on quality of life among Chinese-speaking adolescents in mainland China.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: MH, ZC and YY acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data. ZZ, JM and XH supported the analysis and interpretation of the data. MH, XZ and ZC drafted the manuscript. YM, ZZ and JZ designed and supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Yichen Meng https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3044-3913

Jianquan Zhao https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2847-952X

References

- 1.Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(2):165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng JC, Castelein RM, Chu WC, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuznia AL, Hernandez AK, Lee LU. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: common questions and answers. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(1):19-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma K, Lonner B, Hoashi JS, et al. Demographic factors affect scoliosis research society-22 performance in healthy adolescents: a comparative baseline for adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(24):2134-2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figueras C, Matamalas A, Pizones J, Moreno-Manzanaro L, Betegon J, Bago J. The relationship of kinesiophobia with pain and quality of life in idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021;46(21):1455-1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chau WW, Hung AL. Changes in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of a specific group of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) patients who came across both bracing and surgery. Indian J Orthop. 2021;55(4):925-930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cong H, Chen L, Shen J, et al. Is physical capacity correlated with health-related quality of life in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(6):6220-6227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Climent JM, Reig A, Sanchez J, Roda C. Construction and validation of a specific quality of life instrument for adolescents with spine deformities. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(18):2006-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pham VM, Houlliez A, Carpentier A, Herbaux B, Schill A, Thevenon A. Determination of the influence of the Cheneau brace on quality of life for adolescent with idiopathic scoliosis. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2008;51(13-8):9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulte TL, Thielsch MT, Gosheger G, Boertz P, Terheyden JH, Wetterkamp M. German validation of the quality of life profile for spinal disorders (QLPSD). Eur Spine J. 2018;27(1):83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rezaei Motlagh F, Kamali M, Babaee T. Persian adaptation of quality of life profile for spinal deformities questionnaire. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2018;31(1):177-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SH, Goh TS, Park YG, Kim DS, Lee JS. Validation of a Korean version of the quality-of-life profile for spine deformities (QLPSD) in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26(1):84-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186-3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren XS, Amick B, 3rd, Zhou L, Gandek B. Translation and psychometric evaluation of a Chinese version of the SF-36 Health Survey in the United States. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1129-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung KM, Senkoylu A, Alanay A, Genc Y, Lau S, Luk KD. Reliability and concurrent validity of the adapted Chinese version of Scoliosis Research Society-22 (SRS-22) questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(10):1141-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallant JN, Morgan CD, Stoklosa JB, Gannon SR, Shannon CN, Bonfield CM. Psychosocial difficulties in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: body image, eating behaviors, and mood disorders. World Neurosurg. 2018;116:421-432 e421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Essex R, Bruce G, Dibley M, Newton P, Dibley L. A systematic scoping review and textual narrative synthesis of long-term health-related quality of life outcomes for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2021;40:100844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroeder JE, Michaeli T, Luria M, Itshayek E, Kaplan L. Long-term effects on sexual function in women treated with scoliosis correction for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Global Spine J. 2022. DOI: 10.1177/21925682221079263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai Z, Wu R, Zheng S, Qiu Z, Wu K. Morphology and epidemiological study of idiopathic scoliosis among primary school students in Chaozhou, China. Environ Health Prev Med. 2021;26(1):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du Q, Zhou X, Negrini S, et al. Scoliosis epidemiology is not similar all over the world: a study from a scoliosis school screening on Chongming Island (China). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feise RJ, Donaldson S, Crowther ER, Menke JM, Wright JG. Construction and validation of the scoliosis quality of life index in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(11):1310-1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Climent JM, Bago J, Ey A, Perez-Grueso FJ, Izquierdo E. Validity of the Spanish version of the scoliosis research society-22 (SRS-22) patient questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(6):705-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matamalas A, Bago J, D'Agata E, Pellise F. Body image in idiopathic scoliosis: a comparison study of psychometric properties between four patient-reported outcome instruments. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]