This cross-sectional study assesses sociodemographics, precipitating circumstances, and suicide mechanisms associated with documented mental health diagnosis among youths aged 10 to 24 years who died by suicide.

Key Points

Question

What characteristics of youth suicide decedents and suicide circumstances are associated with having a documented mental health diagnosis?

Findings

This cross-sectional study of 40 618 youth suicide decedents from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Violent Death Reporting System found 24 192 decedents (59.6%) had no previously documented mental health diagnosis and 19 027 (46.8%) died by firearm suicide. The odds of having a documented mental health diagnosis were lower among racially and ethnically minoritized youths and among youths who used firearms.

Meaning

These findings suggest that a critical need exists for comprehensive youth suicide prevention strategies, including early identification of mental health concerns, equitable access to mental health services, and universal lethal means counseling.

Abstract

Importance

Suicide is a leading cause of death among US youths, and mental health disorders are a known factor associated with increased suicide risk. Knowledge about potential sociodemographic differences in documented mental health diagnoses may guide prevention efforts.

Objective

To examine the association of documented mental health diagnosis with (1) sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, (2) precipitating circumstances, and (3) mechanism among youth suicide decedents.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective, cross-sectional study of youth suicide decedents aged 10 to 24 years used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Violent Death Reporting System from 2010 to 2021. Data analysis was conducted from January to November 2023.

Exposures

Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, precipitating circumstances, and suicide mechanism.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was previously documented presence of a mental health diagnosis. Associations were evaluated by multivariable logistic regression.

Results

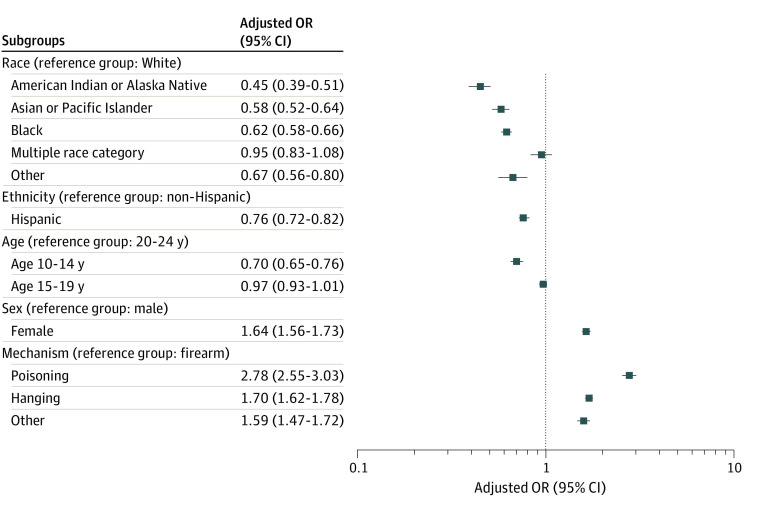

Among 40 618 youth suicide decedents (23 602 aged 20 to 24 years [58.1%]; 32 167 male [79.2%]; 1190 American Indian or Alaska Native [2.9%]; 1680 Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander [4.2%]; 5118 Black [12.7%]; 5334 Hispanic [13.2%]; 35 034 non-Hispanic; 30 756 White [76.1%]), 16 426 (40.4%) had a documented mental health diagnosis and 19 027 (46.8%) died by firearms. The adjusted odds of having a mental health diagnosis were lower among youths who were American Indian or Alaska Native (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.45; 95% CI, 0.39-0.51); Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander (aOR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.52-0.64); and Black (aOR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.58-0.66) compared with White youths; lower among Hispanic youths (aOR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.72-0.82) compared with non-Hispanic youths; lower among youths aged 10 to 14 years (aOR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.65-0.76) compared with youths aged 20 to 24 years; and higher for females (aOR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.56-1.73) than males. A mental health diagnosis was documented for 6308 of 19 027 youths who died by firearms (33.2%); 1691 of 2743 youths who died by poisonings (61.6%); 7017 of 15 331 youths who died by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (45.8%); and 1407 of 3181 youths who died by other mechanisms (44.2%). Compared with firearm suicides, the adjusted odds of having a documented mental health diagnosis were higher for suicides by poisoning (aOR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.62-1.78); hanging, strangulation, and suffocation (aOR, 2.78; 95% CI, 2.55-3.03); and other mechanisms (aOR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.47-1.72).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study, 3 of 5 youth suicide decedents did not have a documented preceding mental health diagnosis; the odds of having a mental health diagnosis were lower among racially and ethnically minoritized youths than White youths and among firearm suicides compared with other mechanisms. These findings underscore the need for equitable identification of mental health needs and universal lethal means counseling as strategies to prevent youth suicide.

Introduction

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for US youths aged 10 to 14 years and the third leading cause of death for youths aged 15 to 24 years, with nearly one-half due to firearms.1 From 2010 to 2021, 71 820 youths aged 10 to 24 years died by suicide with a near 50% increase in annual suicide rates over this period.1 Prior studies indicate that less than one-half of youths who die by suicide have a previously documented mental health (MH) problem or diagnosis.2,3 No studies utilizing recent data have examined whether documentation of prior MH diagnosis varies by sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

As youth suicide rates have increased, disparities have widened. Among racial and ethnic groups, American Indian and Alaska Native youths have the highest rate of suicide overall (41.9 per 100 000 youths in 2020) while the rate of suicide has risen the fastest among Black youths (6.9 per 100 000 youths in 2010 and 12.9 per 100 000 youths in 2020—an 87% increase).1,4 Racially and ethnically minoritized youths experience inequities in access to MH services, resulting in disparities in outcomes.5,6 These disparities persisted and widened after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought social isolation and stressors at home, decreased access to timely MH services, and increased access to firearms.7,8,9,10,11 During the first year of the pandemic, there were significantly more suicides than expected among male youths, children aged 5 to 12 years, youths aged 18 to 24 years, non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native youths, and Black youths, as well as more firearm suicides than expected.12

Despite shifting patterns of MH service use and increased firearm accessibility, few studies have evaluated which population subgroups are most likely to have a known MH diagnosis prior to youth suicide. Early identification and documentation of an MH disorder, a known factor associated with increased risk of suicide, may facilitate timely targeted suicide prevention efforts and access to MH services.13,14 In the context of increased firearm access, identification of these intervenable characteristics is vitally important for suicide prevention. Therefore, our objective was to examine the association of sociodemographic characteristics, suicide mechanism, clinical characteristics, and precipitating circumstances with having a documented MH diagnosis among youth suicide decedents.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

This retrospective, cross-sectional study was determined exempt from human participants research and the requirement of informed consent by the institutional review board of Emory University and followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.15 The study population included US youths aged 10 to 24 years that died by suicide between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2021. We used mortality data from the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) Restricted Access Database. NVDRS is a state-based surveillance system that collects data on all violent deaths including suicide, homicide, legal intervention death, unintentional firearm death, and death of undetermined intent that might have been caused by violence.16 Data are collected from 3 required data sources: death certificates, coroner and medical examiner records, and law enforcement reports.16 We included data from all available states and territories that contribute data to NVDRS, which increased from 16 states in 2010 to 49 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico in 2021 (eTable in Supplement 1).17 At the time of the analysis, NVDRS data were available through 2021.

Suicide cases were determined based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) cause of death codes (X60-X84, Y87.0, and U03) and/or based on evidence from source documents, with the final manner of death assigned by trained NVDRS abstractors.16 Suicide was assigned if death resulted from use of force against oneself and a collection of evidence indicated that use of force was intentional.16,18

Study Measures

The primary outcome was the presence of a previously documented MH diagnosis among youth suicide decedents. To identify this outcome, we utilized the MH problem variable defined by NVDRS as (1) the decedent has a current MH diagnosis as categorized by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5), not including from alcohol or other substance dependence, or (2) source documents (death certificate, coroner or medical examiner report, and police report) list the decedent as being treated for an MH problem, potentially from family member report or current prescription.18

Sociodemographic characteristics included race (American Indian or Alaskan Native; Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander; Black; White; multiple race category, and other [defined as any race not otherwise specified] or unspecified), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), age group (10-14 years, 15-19 years, and 20-24 years), and sex (female and male). Race and ethnicity were reported from combined raw data available from source documents (including death certificates, coroner and medical examiner records, and law enforcement reports) and verified by NVDRS investigator teams. Acknowledging race and ethnicity are social constructs, and racially and ethnically minoritized populations often have inequitable access to MH services, race and ethnicity were included as covariates in the analyses.19,20

Clinical characteristics included MH variables such as depressed mood, suicidality (suicide disclosure, history of nonsuicidal self-harm or self-injury, history of suicidal thoughts, or attempts), and substance misuse (alcohol and/or substance abuse). These MH characteristics were considered separate from a documented MH diagnosis. Decedents were categorized as having depressed mood if the they were perceived by themselves or others as depressed at the time of death; the definition does not require a clinical diagnosis of depression or that depression directly contributed to death.18

Precipitating circumstances were identified per coroner or medical examiner and law enforcement reports as having contributed to suicide death. Decedents could have multiple precipitating circumstances. We included precipitating circumstances regarding interpersonal problems, other life stressors (such as criminal, civil legal, school, or financial) and recent crises (defined as within 2 weeks prior to death).

Suicide mechanisms were defined as firearms; poisonings; hanging, strangulation, or suffocation; and other (which included motor vehicle, falls, and sharp or blunt instruments). Location of suicide was categorized as home, other, or unknown.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted descriptive analysis with counts and frequencies of suicide deaths by sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, precipitating circumstances, location, and mechanism. We performed χ2 tests of proportions to assess differences in the proportion of suicide decedents with and without a documented MH diagnosis by sociodemographics, mechanism, and location. We used multivariable logistic regression to determine sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, precipitating factors, and mechanisms associated with the presence of a documented MH diagnosis. We constructed a model using the full cohort and then performed stratified analysis by age group. All models were adjusted for race, ethnicity, sex, and age group. Results were reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% CIs. All hypothesis testing was 2-sided, with statistical significance set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Data analysis was conducted from January to November 2023.

Results

Characteristics of Study Sample

We identified 40 618 suicide decedents aged 10 to 24 years (23 602 aged 20 to 24 years [58.1%]; 32 167 male [79.2%]; 1190 American Indian or Alaska Native [2.9%]; 1680 Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander [4.2%]; 5118 Black [12.7%]; 30 756 White [76.1%]; 1017 multiple race category [2.5%]; 673 other or unspecified race [1.7%]; 184 unknown race [0.5%]); 5334 Hispanic [13.2%]; and 35 034 non-Hispanic [86.8%]). Most suicides occurred at home (25 174 [64.8%]) (Table 1). The most common precipitating circumstances were intimate partner problems (10249 [25.2%]) and family relationship problems (4462 [13.3%]) (Table 2).

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Suicide Mechanisms by Documented Mental Health Diagnosis.

| Characteristic | Participants, No (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 40 618)a | Documented mental health diagnosis (n = 16 426)b,c,d | No documented mental health diagnosis (n = 24 192)b,c | |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1190 (2.9) | 333 (28.0) | 857 (72.0) |

| Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander | 1680 (4.2) | 591 (35.2) | 1089 (64.8) |

| Black | 5118 (12.7) | 1655 (32.3) | 3463 (67.7) |

| Multiple race category | 1017 (2.5) | 429 (42.2) | 588 (57.8) |

| White | 30 756 (76.1) | 13 153 (42.8) | 17 603 (57.2) |

| Other or unspecifiede | 673 (1.7) | 211 (31.4) | 462 (68.6) |

| Unknown | 184 (0.5) | 54 (29.3) | 130 (70.7) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 5334 (13.2) | 1959 (36.7) | 3375 (63.3) |

| Non-Hispanic | 35 034 (86.8) | 14 376 (41.0) | 20 658 (59.0) |

| Unknown | 250 (0.6) | 91 (36.4) | 159 (63.6) |

| Age group, y | |||

| 10-14 | 3171 (7.8) | 1150 (36.3) | 2021 (63.7) |

| 15-19 | 13 845 (34.1) | 5702 (41.2) | 8143 (58.8) |

| 20-24 | 23 602 (58.1) | 9574 (40.6) | 14 028 (59.4) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 32 167 (79.2) | 11 994 (37.3) | 20 173 (62.7) |

| Female | 8446 (20.8) | 4429 (52.4) | 4017 (47.6) |

| Unknown | 5 (<0.1) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) |

| Suicide method | |||

| Firearms | 19 027 (46.8) | 6308 (33.2) | 12 719 (66.8) |

| Poisoning | 2743 (6.8) | 1691 (61.6) | 1052 (38.4) |

| Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation | 15 331 (37.7) | 7017 (45.8) | 8314 (54.2) |

| Other | 3181 (7.8) | 1407 (44.2) | 1774 (55.8) |

| Unknown | 336 (0.8) | 3 (0.9) | 333 (99.1) |

| Location of injury | |||

| Home | 25 174 (64.8) | 11 076 (44.0) | 14 098 (56.0) |

| Other | 13 665 (35.2) | 5194 (38.0) | 8471 (62.0) |

| Unknown | 1779 (4.4) | 156 (8.8) | 1623 (91.2) |

Percentages by column.

Percentages by row.

P < .001 for all comparisons.

As reported in National Violent Death Reporting System data from coroner, medical examiner, or law enforcement reports.

Other included any race not otherwise specified. National Violent Death Reporting System follows US Department of Health and Human Services and Office of Management and Budget standards for race and ethnicity categorization.21

Table 2. Clinical Characteristics and Precipitating Circumstances by Documented Mental Health Diagnosis.

| Clinical characteristics | Participants, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 40 618) | Documented mental health diagnosis (n = 16 426)a | No documented mental health diagnosis (n = 24 192) | |

| Depressed mood | 11 644 (28.7) | 5879 (35.8) | 5765 (23.8) |

| Suicidality or self-harm | |||

| Suicide intent disclosure | 8948 (22.0) | 4518 (27.5) | 4430 (18.3) |

| Left suicide note | 11 521 (28.4) | 5358 (32.6) | 6163 (25.5) |

| History of nonsuicidal self-harm or self-injuryb | 499 (7.5) | 362 (13.9) | 137 (3.4) |

| History of suicidal thoughtsc | 10 554 (31.5) | 6650 (48.2) | 3904 (19.9) |

| History of suicide attempt | 7634 (18.8) | 5610 (34.2) | 2024 (8.4) |

| Substance problem | |||

| Alcohol abuse problem | 3560 (8.8) | 1908 (11.6) | 1652 (6.8) |

| Alcohol use in hours preceding deathd | 3786 (14.6) | 1614 (15.1) | 2172 (15.0) |

| Substance abuse problem | 6282 (15.5) | 3371 (20.5) | 2911 (12.0) |

| Substance caused death | 2545 (6.3) | 1611 (9.8) | 934 (3.9) |

| Precipitating circumstances | |||

| Interpersonal problem | |||

| Family relationship problemc | 4462 (13.3) | 2126 (15.4) | 2336 (11.9) |

| Other relationship problem | 2040 (5.0) | 882 (5.4) | 1158 (4.8) |

| Intimate partner problem | 10 249 (25.2) | 4026 (24.5) | 6223 (25.7) |

| Experienced interpersonal violence | 238 (0.6) | 111 (0.7) | 127 (0.5) |

| Perpetrator of interpersonal violence | 691 (1.7) | 240 (1.5) | 451 (1.9) |

| Abused as a child | 969 (2.4) | 687 (4.2) | 282 (1.2) |

| Other life stressors | |||

| Suicide of family member or friend | 1159 (2.9) | 587 (3.6) | 572 (2.4) |

| Disasterc | 363 (1.1) | 203 (1.5) | 160 (0.8) |

| Criminal problem | 2758 (6.8) | 1028 (6.3) | 1730 (7.2) |

| Civil legal problem | 553 (1.4) | 225 (1.4) | 328 (1.4) |

| School problem | 3340 (8.2) | 1553 (9.5) | 1787 (7.4) |

| Financial problem | 1287 (3.2) | 580 (3.5) | 707 (2.9) |

| Job problem | 2308 (5.7) | 1065 (6.5) | 1243 (5.1) |

| Death of family member or friend | 1557 (3.8) | 735 (4.5) | 822 (3.4) |

| Eviction or loss of home | 639 (1.6) | 283 (1.7) | 356 (1.5) |

| Crises within 2 wk prior to death | |||

| Any crises | 10 933 (26.9) | 4757 (29.0) | 6176 (25.5) |

| Alcohol problemc | 234 (0.7) | 129 (0.9) | 105 (0.5) |

| Substance abuse probleme | 309 (0.9) | 139 (1.0) | 170 (0.9) |

| Mental healthe | 495 (1.5) | 495 (3.6) | 0 |

| Family relationship problemc | 1450 (4.3) | 674 (4.9) | 776 (3.9) |

| School problemc | 733 (2.2) | 306 (2.2) | 427 (2.2) |

| Intimate partner problemc | 3893 (11.6) | 1619 (11.7) | 2274 (11.6) |

| Financial problemc | 152 (0.5) | 69 (0.5) | 83 (0.4) |

| Criminal legal problemc | 963 (2.9) | 338 (2.4) | 625 (3.2) |

| Civil legal problemc | 121 (0.4) | 48 (0.3) | 73 (0.4) |

| Job probleme | 497 (1.5) | 237 (1.7) | 260 (1.3) |

As reported in National Violent Death Reporting System data from coroner or medical examiner or law enforcement reports.

Data for this variable were collected starting November 1, 2020. During that time, the total number of decedents was 6659; 2605 had a documented mental health diagnosis and 4054 had no documented mental health diagnosis.

Data for these variables were collected starting August 1, 2013. During that time, the total number of decedents was 33 456; 13 805 had a documented mental health diagnosis and 19 651 had no documented mental health diagnosis.

Data for these variables were collected starting August 1, 2016. During that time, the total number of decedents was 25 994; 10 704 had a documented mental health diagnosis and 15 290 had no documented mental health diagnosis.

Data for these variables were collected starting July 1, 2013. During that time, the total number of decedents was 33 594; 13 858 had a documented mental health diagnosis and 19 736 had no documented mental health diagnosis.

Characteristics of Youths With and Without a Documented MH Diagnosis

Among youth suicide decedents, 16 426 (40.4%) had a documented MH diagnosis and 24 192 (59.6%) had no documented diagnosis. Across individual groups, White youths had the highest rate of MH diagnosis (13 153 youths [42.8%]) and American Indian or Alaska Native youths had the lowest rate (333 youths [28.0%]); among Hispanic youths, 1959 (36.7%) had an MH diagnosis. Slightly more than one-half of female youths had an MH diagnosis (4429 youths [52.4%]), compared with 11 994 male youths (37.3%) (Table 1). Compared with those without an MH diagnosis, decedents with an MH diagnosis had higher rates of depressed mood (5879 youths [35.8%] vs 5765 youths [23.8%]), suicidal intent disclosure (4518 youths [27.5%] vs 4430 youths [18.3%]), and history of suicidal thoughts (6650 youths [48.2%] vs 3904 youths [19.9%]). Table 2 shows the association of preceding MH diagnosis with suicidality and self-harm, substance problems, precipitating circumstances, and crisis within the 2 weeks prior to death.

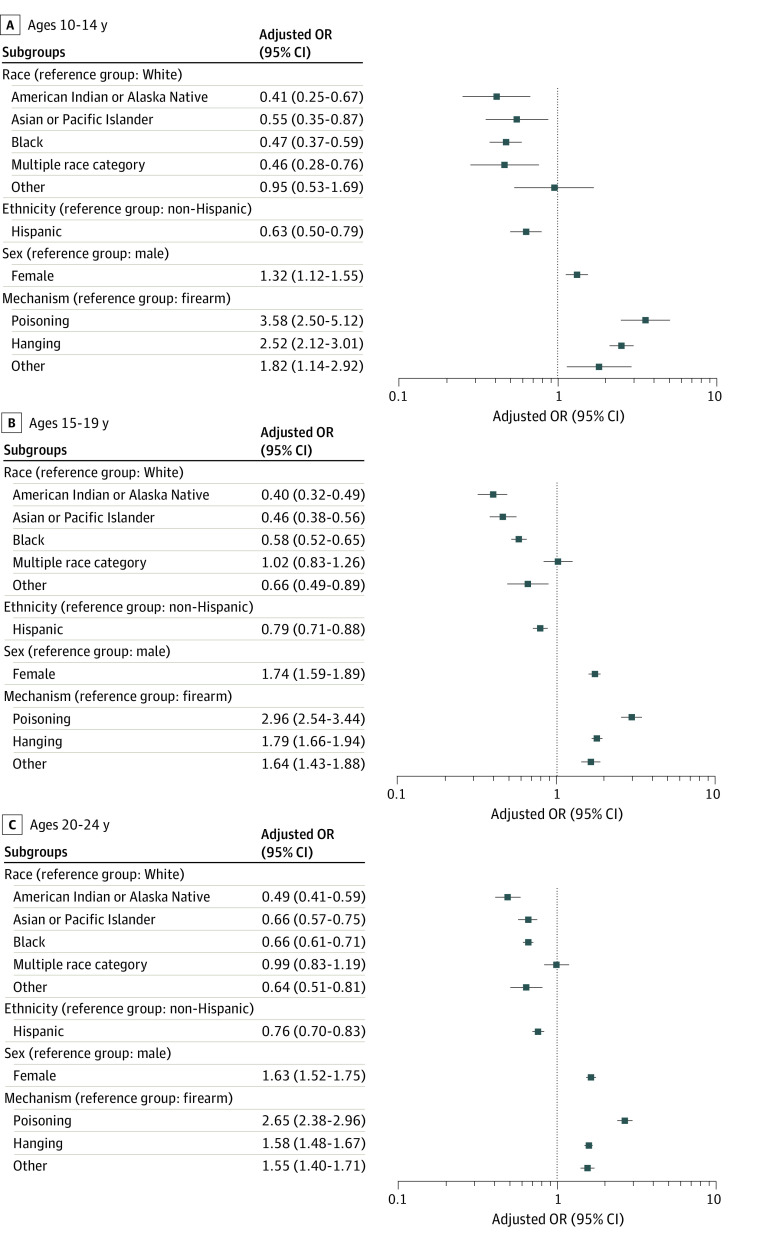

In comparison with White youths who died by suicide, there were lower adjusted odds of having a documented MH diagnosis among American Indian and Alaska Native youths (aOR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.39-0.51); Asian, Native, Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander youths (aOR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.52-0.64); and Black youths (aOR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.58-0.66) (Figure 1). The ORs by race tended to narrow as youths aged, such as among Black youths aged 10 to 14 years (aOR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.37-0.59), 15 to 19 years (aOR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.52-0.65), and 20 to 24 years (aOR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.61-0.71) (Figure 2). Compared with non-Hispanic youths, Hispanic youths had lower adjusted odds of having an MH diagnosis (aOR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.72-0.82) (Figure 1). Compared with youths aged 20 to 24 years, the adjusted odds were lower for youths aged 10 to 14 years (aOR 0.70, 95% CI, 0.65-0.76) but were not statistically different for youths aged 15 to 19 years (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.93-1.01). Females had higher adjusted odds (aOR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.56-1.73) of having a documented MH diagnosis compared with males .

Figure 1. Multivariable Model for Sociodemographic Characteristics and Suicide Mechanisms Associated With Having a Documented Mental Health Diagnosis.

Logistic regression model with adjusted odds ratio adjusting for race, ethnicity, sex, and age. Pacific Islander included Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Other race included any race not otherwise specified or unspecified race. Hanging included strangulation or suffocation. OR indicates odds ratio.

Figure 2. Multivariable Model for Sociodemographic Characteristics and Suicide Mechanism Associated With Having a Documented Mental Health Diagnosis Stratified by Age.

Logistic regression model with adjusted odds ratio adjusting for race, ethnicity, and sex. Pacific Islander included Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Other race included any race not otherwise specified or unspecified race. Hanging included strangulation or suffocation. OR indicates odds ratio.

There were higher adjusted odds of having a documented MH diagnosis among youths with depressed mood (aOR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.67-1.83), with each suicidality or self-harm characteristic, and with substance abuse (aOR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.76-1.97) when compared with youths without those characteristics (Table 3). Youths had higher odds of having a documented MH diagnosis if they had family relationship problems (aOR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.29-1.47) or experienced child abuse (aOR, 3.39; 95% CI, 2.93-3.91) compared with youths without those precipitating circumstances. Youths with intimate partner problems had lower odds of having a documented MH diagnosis (aOR, 0.90, 95% CI, 0.86- 0.94) than youths without intimate partner violence problems.

Table 3. Multivariable Model for Clinical Characteristics and Precipitating Circumstances Associated With Having a Documented Mental Health Diagnosis.

| Clinical characteristics | Having a documented mental health diagnosis, aOR (95% CI)a,b | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Depressed mood | 1.75 (1.67-1.83) | <.001 |

| Suicidality or self-harm | ||

| Suicide intent disclosure | 1.68 (1.60-1.76) | <.001 |

| Left suicide note | 1.31 (1.25-1.37) | <.001 |

| History of nonsuicidal self-harm or self-injury | 3.96 (3.20-4.89) | <.001 |

| History of suicidal thoughts | 3.68 (3.51-3.87) | <.001 |

| History of suicide attempt | 5.37 (5.07-5.69) | <.001 |

| Substance problem | ||

| Alcohol | 1.82 (1.70-1.96) | <.001 |

| Alcohol use in hours preceding death | 0.89 (0.83- 0.96) | .002 |

| Substance abuse | 1.86 (1.76-1.97) | <.001 |

| Substance-caused death | 2.28 (2.10-2.49) | <.001 |

| Precipitating circumstances | ||

| Interpersonal problem | ||

| Family relationship problem | 1.37 (1.29-1.47) | <.001 |

| Other relationship problem | 1.11 (1.01-1.21) | .03 |

| Intimate partner problem | 0.90 (0.86-0.94) | <.001 |

| Experienced interpersonal violence | 1.11 (0.85-1.44) | .45 |

| Perpetrator of interpersonal violence | 0.87 (0.74-1.02) | .09 |

| Abused as a child | 3.39 (2.93-3.91) | <.001 |

| Other life stressors | ||

| Suicide of family member or friend | 1.47 (1.30-1.65) | <.001 |

| Disaster | 1.80 (1.45-2.23) | <.001 |

| Criminal problem | 0.93 (0.86-1.01) | .07 |

| Civil legal problem | 1.00 (0.84-1.19) | .99 |

| School problem | 1.40 (1.30-1.51) | <.001 |

| Financial problem | 1.20 (1.07-1.34) | .002 |

| Job problem | 1.29 (1.19-1.41) | <.001 |

| Death of family member or friend | 1.33 (1.20-1.47) | <.001 |

| Eviction or loss of home | 1.15 (0.98-1.35) | .01 |

| Crisis within 2 wk prior to death | ||

| Any crises | 1.18 (1.13-1.24) | <.001 |

| Alcohol problem | 1.71 (1.32-2.22) | <.001 |

| Substance abuse problem | 1.13 (0.90-1.43) | .28 |

| Mental health | NA | NA |

| Family relationship problem | 1.29 (1.15-1.43) | <.001 |

| School problem | 1.06 (0.91-1.24) | .456 |

| Intimate partner problem | 0.98 (0.92-1.05) | .60 |

| Financial problem | 1.19 (0.86-1.64) | .30 |

| Criminal legal problem | 0.83 (0.72-0.95) | .006 |

| Civil legal problem | 0.92 (0.64-1.34) | .67 |

| Job problem | 1.33 (1.11-1.59) | .002 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Adjusting for race, ethnicity, age, and sex.

As reported in National Violent Death Reporting System data from coroner or medical examiner or law enforcement reports.

Mechanism

An MH diagnosis was documented for 6308 of 19 027 youths who died by firearms (33.2%); 1691 of 2743 youths who died by poisonings (61.6%); 7017 of 15 331 youths who died by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (44.2%); and 1407 of 3181 youths who died by other mechanisms (44.8%). Among decedents with a documented MH diagnosis, the most common mechanism was hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (7017 decedents [42.7%]). Among decedents without a documented MH diagnosis, the most common mechanism was firearms (12 719 decedents [52.6%]). Among all decedents, 19 027 [46.8%] died by firearms. In the multivariable model, compared with youths who died by firearms, youths who died by poisonings (aOR, 2.78; 95% CI, 2.55-3.03); hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (aOR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.62-1.78); and other mechanisms (aOR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.47-1.72) had higher adjusted odds of having a documented MH diagnosis (Figure 1). Likewise, within each age group stratum, youths who died by poisonings and hanging, strangulation, or suffocation had higher adjusted odds of having a documented MH diagnosis compared with those who died by firearms.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of youth suicides across the US that utilized the most recently available NVDRS data, we found that approximately 3 of 5 youth suicide decedents did not have a documented MH diagnosis. Racially and ethnically minoritized, male, and younger youths were less likely to have a documented MH diagnosis prior to suicide death than White, female, and older youths, respectively. Furthermore, youths who used a firearm, the mechanism with the highest case fatality rate,22,23 were far less likely to have a documented MH diagnosis.

Despite older literature that demonstrated that many youths who die by suicide have not received adequate MH screening and services, it appears that challenges persist in the identification of youths at risk even amid the current growing MH crisis. In this updated evaluation of suicide decedents within NVDRS, which captures the largest proportion to date (56.6% of US youth suicide decedents1), rates of documented MH diagnoses did not improve substantially from prior studies. From 2003 to 2012, only 34.6% of youth suicide decedents aged 5 to 11 years and 34.8% of youth suicide decedents aged 12 to 14 years had a documented known MH problem.3,24 Similarly, from 2013 to 2018, only 42.1% of youth suicide decedents aged 10 to 19 years had a known MH condition.2 This low rate of documented MH diagnosis among youth suicide decedents may reflect inadequate detection of MH needs, the impulsive nature of suicidal acts, increased access to more lethal means such as firearms, or alternative risk factors such as increased stressful life circumstances.9,25,26

We found significant racial and ethnic disparities in MH diagnoses among youths who died by suicide. This is consistent with prior literature6 that found only approximately 35% of Black youths had a documented current MH problem prior to death across age groups. Missed MH diagnosis among racially and ethnically minoritized youths who die by suicide may result from inequitable access to MH screening and diagnosis.19 On the other hand, racially and ethnically minoritized youths might have lower rates of MH diagnoses because they experienced other factors associated with increased risk of suicide besides MH conditions, including structural racism, discrimination, exposure to adverse childhood experiences, poverty, and lack of opportunity in certain neighborhoods.27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 To counter these risk factors, suicide prevention efforts for racially and ethnically minoritized youths should include trauma-informed, culturally sensitive MH services, increased diversity in the MH workforce, and investments in school-based MH services, where Black youths are more likely than White youths to receive care.19,35 Such efforts could incorporate preventive interventions, grounded in cognitive-behavioral therapy, developed to counter stressors associated with systemic racism.6,36 Suicide prevention programming delivered in nontraditional community settings by individuals with lived experience may garner more receptivity and trust among Black youths than prevention efforts delivered in traditional health care settings.32,37,38,39,40

We found significant age differences in rates of MH diagnosis, with lower odds of having an MH diagnosis prior to suicide among youths aged 10 to 14 years compared with those aged 20 to 24 years. This finding is particularly notable because suicide rates have risen to become the second leading cause of death in youths aged 10 to 14 years.1 Among even younger children, during the first year of COVID-19 pandemic, non-Hispanic White 5- to 12-year-olds had a 31% increase in suicides over the expected number.12 Prior work suggests that suicide vulnerability may progress developmentally, from an impulsive response among younger children to a response to depressed mood or emotional distress during adolescence and adulthood.3,24 Suicide prevention strategies for young children in primary care and community settings should focus on fostering resilience, promoting peer and family connectedness, and empowering children with strategies to cope with stress and adversity.14

Regarding suicide mechanism, firearms were the most commonly utilized method among youths in our study, which differs from previous NVDRS work in which hanging, strangulation, and suffocation was the most common method among youths.2,3 This difference could be due to increased availability and accessibility of firearms over the course of our study period or inclusion of youths aged 20 to 24 years.9,25 Recent studies also demonstrate increased use of firearms as suicide mechanism.12 Similar to a prior study,2 we found that decedents without a documented MH diagnosis were far more likely to utilize a firearm than those with a documented MH diagnosis. Furthermore, in one study,41 24% of teens and young adults spent less than 5 minutes between the decision to attempt suicide and the actual attempt. These impulsive attempts were more likely among those involved in a physical altercation and less likely among those who were depressed.41 This finding speaks to the need for universal lethal means counseling, delivered in community and school settings, regardless of whether youths have a known MH diagnosis. Teens should be involved in conversations about the risks of firearms given that many can easily access firearms.42,43 Among US teens, 44.2% perceived that they could access a firearm, while 20.2% perceived they could access a firearm within less than 5 minutes.42

Suicide prevention strategies are needed for the estimated 22.6 million US children living in households with firearms, of whom 4.5 million are exposed to firearms stored loaded and unlocked.44 More than 75% of guns used in youth suicide are owned by a family member, most commonly parents,45 and the presence of a firearm in the home is associated with an increased risk of youth suicide.46,47,48 This risk can be mitigated with secure firearm storage, including storing all guns locked, unloaded, with ammunition stored locked and in a separate location.46 Likewise, support and passage of state child access protection (CAP) laws, specifically negligence CAP laws, effectively reduce youth firearm suicide rates.49,50

Youths with depressed mood and suicidality characteristics, similar to prior literature,2 had higher odds of having a documented MH diagnosis. However, in our study, no MH diagnosis was documented in about one-half of youths noted to be depressed (at the time of or in the weeks leading up to death) or who had previously disclosed suicide intent within the month prior to death. Both nonsuicidal self-injury and previous suicide attempt are predictors of suicide among adolescents.16,51,52,53 However, at least 1 in 4 decedents with a history of nonsuicidal self-injury and 1 in 4 with a prior suicide attempt had no documented MH diagnosis. These youths presumably were not connected to MH services. Thus, attention is needed to increase accessibility of MH screening, diagnosis, and treatment in both primary care and specialty MH settings.

Family relationship and intimate partner problems were the most common circumstances experienced by youth decedents overall. Previous youth suicide studies have found higher rates of family and friend relationship problems among younger youths, while intimate partner problems were more prevalent in older age groups.2,3,24 Promoting connectedness and strengthening relationships among youths and parents or caregivers can protect against youth suicide.24,54 The Surgeon General 2021 call to action for suicide prevention40 delineates exemplars of evidence-based programs (eg, Sources of Strength and Good Behavior Game) that enhance social connectedness within families, school, and communities, including peer norm programs and community engagement activities.55,56

For precipitating circumstances among youth decedents in our study, the likelihood of having a documented MH diagnosis varied across family and life stressors, with no significant difference in the likelihood of having an MH diagnosis for any of the individual crisis variables. This speaks to youths’ challenges with adapting to family or life stressors and acute crisis regardless of the presence of an MH disorder. Additionally, teaching coping skills and increasing family and societal supports could prevent precipitating life circumstances.

Limitations

There are limitations with this study. First, NVDRS is not a representative national sample because various states began contributing data during different years. However, NVDRS capture rates of youth suicide deaths in the Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System have increased from 28.0% in 2010 to 87.4% in 2021.1 Second, documentation of an MH diagnosis was defined by source records (ie, coroner, medical examiner, or law enforcement) and family member accounts; some decedents may have had an MH diagnosis that was unknown, undiagnosed, or unreported. However, utilization of these source records increases the likelihood of detecting MH diagnoses relative to administrative datasets that rely solely on billing diagnosis codes. Third, we could not conduct analyses using sexual orientation and gender identity variables due to a substantial degree of missingness. Fourth, the study was limited to analyses of quantitative data fields in NVDRS; incident narratives from law enforcement, coroner, and medical examiner reports were not examined for this study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, most youth suicide decedents in this detailed, recent national sample did not have a documented MH diagnosis, signaling inadequate detection of MH needs. Youths who died by firearm suicide, the most common mechanism, had the lowest rate of documented MH diagnosis, highlighting the importance of universal lethal means counseling and CAP laws to increase barriers to firearm access. Social inequities may contribute to differences in MH diagnoses prior to suicide among racially and ethnically minoritized youths. These findings underscore the critical need to increase equitable access to MH screening, diagnosis, and treatment for all youths. Given the low rates of MH diagnoses among youth suicide decedents, prevention efforts must also address family and life stressors in tandem with MH risk factors. Both increased identification of unmet MH needs and universal, community-based approaches are needed to prevent youth suicide.

eTable. Availability of State, Territory, and Jurisdiction Data for NVDRS Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) and Restricted Access Database (RAD)

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Accessed August 16, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leadingcauses.html

- 2.Rice K, Brown M, Nataraj N, Xu L. Circumstances contributing to suicide among U.S. adolescents aged 10-19 years with and without a known mental health condition: national violent death reporting system, 2013-2018. J Adolesc Health. 2023;72(4):519-525. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheftall AH, Asti L, Horowitz LM, et al. Suicide in elementary school-aged children and early adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4):e20160436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mascia J, Pierce O. Youth gun suicide is rising, particularly among children of color. The Trace. Published February 24, 2022. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www.thetrace.org/2022/02/firearm-suicide-rate-cdc-data-teen-mental-health-research/

- 5.Triplett NS, Luo M, Nguyen JK, Sievert K. Social determinants and treatment of mental disorders among children: analysis of data from the national survey of children’s health. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(8):922-925. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheftall AH, Vakil F, Ruch DA, Boyd RC, Lindsey MA, Bridge JA. Black youth suicide: investigation of current trends and precipitating circumstances. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61(5):662-675. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones SE, Ethier KA, Hertz M, et al. Mental health, suicidality, and connectedness among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic - adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January-June 2021. MMWR Suppl. 2022;71(3):16-21. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffmann JA, Duffy SJ. Supporting youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(12):1485-1487. doi: 10.1111/acem.14398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller M, Zhang W, Azrael D. Firearm purchasing during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the 2021 national firearms survey. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(2):219-225. doi: 10.7326/M21-3423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokol RL, Marineau L, Zimmerman MA, Rupp LA, Cunningham RM, Carter PM. Why some parents made firearms more accessible during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a national study. J Behav Med. 2021;44(6):867-873. doi: 10.1007/s10865-021-00243-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yard E, Radhakrishnan L, Ballesteros MF, et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12-25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, January 2019-May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(24):888-894. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bridge JA, Ruch DA, Sheftall AH, et al. Youth suicide during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2023;151(3):e2022058375. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-058375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gili M, Castellví P, Vives M, et al. Mental disorders as risk factors for suicidal behavior in young people: a meta-analysis and systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:152-162. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horowitz L, Tipton MV, Pao M. Primary and secondary prevention of youth suicide. Pediatrics. 2020;145(suppl 2):S195-S203. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2056H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field N, Cohen T, Struelens MJ, et al. Strengthening the reporting of molecular epidemiology for infectious diseases (STROME-ID): an extension of the STROBE statement. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):341-352. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70324-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu GS, Nguyen BL, Lyons BH, et al. Surveillance for violent deaths - national violent death reporting system, 48 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2023;72(5):1-38. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7205a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . About the national violent death reporting system. Accessed July 3, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nvdrs/about/index.html

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Violence Prevention . National Violent Death Reporting System web coding manual version 6.0. Updated January 18, 2022. Accessed June 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nvdrs/resources/nvdrsCodingManual.pdf

- 19.Hoffmann JA, Alegría M, Alvarez K, et al. Disparities in pediatric mental and behavioral health conditions. Pediatrics. 2022;150(4):e2022058227. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-058227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright JL, Davis WS, Joseph MM, Ellison AM, Heard-Garris NJ, Johnson TL; AAP Board Committee on Equity . Eliminating race-based medicine. Pediatrics. 2022;150(1):e2022057998. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation . HHS implementation guidance on data collection standards for race, ethnicity, sex, primary language, and disability status. US Department of Health and Human Services. October 30, 2011. Accessed June 27, 2024. http://aspe.hhs.gov/datacncl/standards/ACA/4302/index.shtml

- 22.Conner A, Azrael D, Miller M. Suicide case-fatality rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: a nationwide population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(12):885-895. doi: 10.7326/M19-1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. The epidemiology of case fatality rates for suicide in the northeast. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(6):723-730. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruch DA, Heck KM, Sheftall AH, et al. Characteristics and precipitating circumstances of suicide among children aged 5 to 11 years in the United States, 2013-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2115683. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller M, Azrael D. Firearm storage in US households with children: findings from the 2021 national firearm survey. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2148823. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitney DG, Peterson MD. US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(4):389-391. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrett JT, Lee LK, Monuteaux MC, Farrell CA, Hoffmann JA, Fleegler EW. Association of county-level poverty and inequities with firearm-related mortality in US youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(2):e214822. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffmann JA, Farrell CA, Monuteaux MC, Fleegler EW, Lee LK. Association of pediatric suicide with county-level poverty in the United States, 2007-2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(3):287-294. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann JA, Attridge MM, Carroll MS, Simon NE, Beck AF, Alpern ER. Association of youth suicides and county-level mental health professional shortage areas in the US. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(1):71-80. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.4419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works - racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768-773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2025396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bommersbach T, Rhee TG, Jegede O, Rosenheck RA. Mental health problems of black and white children in a nationally representative epidemiologic survey. Psychiatry Res. 2023;321:115106. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fadus MC, Valadez EA, Bryant BE, et al. Racial Disparities in elementary school disciplinary actions: findings from the ABCD study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60(8):998-1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mekawi Y, Hyatt CS, Maples-Keller J, Carter S, Michopoulos V, Powers A. Racial discrimination predicts mental health outcomes beyond the role of personality traits in a community sample of African Americans. Clin Psychol Sci. 2021;9(2):183-196. doi: 10.1177/2167702620957318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell DW, Clavél FD, Cutrona CE, Abraham WT, Burzette RG. Neighborhood racial discrimination and the development of major depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127(2):150-159. doi: 10.1037/abn0000336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Health and Human Services . 2024 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention. Published April 15, 2024. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/programs/prevention-and-wellness/mental-health-substance-abuse/national-strategy-suicide-prevention/index.html [PubMed]

- 36.Robinson WL, Whipple CR, Jason LA, Flack CE. African American adolescent suicidal ideation and behavior: the role of racism and prevention. J Community Psychol. 2021;49(5):1282-1295. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheftall AH, Miller AB. Setting a ground zero research agenda for preventing Black youth suicide. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(9):890-892. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tolliver DG, Lee LK, Patterson EE, Monuteaux MC, Kistin CJ. Disparities in school referrals for agitation and aggression to the emergency department. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(4):598-605. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Education Development Center . Community-Led Suicide Prevention. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://communitysuicideprevention.org/

- 40.US Surgeon General, National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention . The surgeon general’s call to action to implement the national strategy for suicide prevention. 2021. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/sprc-call-to-action.pdf

- 41.Simon OR, Swann AC, Powell KE, Potter LB, Kresnow MJ, O’Carroll PW. Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;32(1)(suppl):49-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haasz M, Myers MG, Rowhani-Rahbar A, et al. Firearms availability among high-school age youth with recent depression or suicidality. Pediatrics. 2023;151(6):e2022059532. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-059532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCarthy V, Wright-Kelly E, Steinhart B, Haasz M, Ma M, Brooks-Russell A. Assessment of reported time to access a loaded gun among Colorado adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(5):543-545. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.0080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azrael D, Cohen J, Salhi C, Miller M. Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: results of a 2015 national survey. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):295-304. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barber C, Azrael D, Miller M, Hemenway D. Who owned the gun in firearm suicides of men, women, and youth in five US states? Prev Med. 2022;164:107066. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707-714. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.6.707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knopov A, Sherman RJ, Raifman JR, Larson E, Siegel MB. Household gun ownership and youth suicide rates at the state level, 2005-2015. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(3):335-342. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monuteaux MC, Azrael D, Miller M. Association of increased safe household firearm storage with firearm suicide and unintentional death among US youths. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(7):657-662. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Azad HA, Monuteaux MC, Rees CA, et al. Child access prevention firearm laws and firearm fatalities among children aged 0 to 14 years, 1991-2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):463-469. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kivisto AJ, Kivisto KL, Gurnell E, Phalen P, Ray B. Adolescent suicide, household firearm ownership, and the effects of child access prevention laws. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60(9):1096-1104. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, McKean AJ. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(11):1094-1100. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clarke S, Allerhand LA, Berk MS. Recent advances in understanding and managing self-harm in adolescents [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. F1000Res. 2019;8(F1000 Faculty Rev):1794. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.19868.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S, et al. Suicide After Deliberate Self-Harm in Adolescents and Young Adults. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173517. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Consoli A, Peyre H, Speranza M, et al. Suicidal behaviors in depressed adolescents: role of perceived relationships in the family. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2013;7(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-7-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Injury Prevention . Suicide prevention resource for action: a compilation of the best available evidence. 2022. Accessed June 27, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/124648

- 56.Wilcox HC, Kellam SG, Brown CH, et al. The impact of two universal randomized first- and second-grade classroom interventions on young adult suicide ideation and attempts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95(Suppl 1)(suppl 1):S60-S73. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Availability of State, Territory, and Jurisdiction Data for NVDRS Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) and Restricted Access Database (RAD)

Data Sharing Statement