Abstract

Novel alkyl zinc complexes supported by acetamidate/thioacetamidate heteroscorpionate ligands have been successfully synthesized and characterized. These complexes exhibited different coordination modes depending on the electronic and steric effects of the acetamidate/thioacetamidate moiety. Their catalytic activity has been tested toward the hydroelementation reactions of alkynyl alcohol/acid substrates, affording the corresponding enol ether/unsaturated lactone products under mild reaction conditions. Kinetic studies have been performed and confirmed that reactions are first-order in [catalyst] and zero-order in [alkynyl substrate]. DFT calculations supported a reaction mechanism through the formation of the catalytically active species, an alkoxide-zinc intermediate, by a protonolysis reaction of the Zn–alkyl bond with the alcohol group of the substrate. Based on the experimental and theoretical results, a catalytic cycle has been proposed.

Short abstract

Zinc-catalyzed hydroelementation of alkynyl alcohols and alkynyl acids.

Introduction

Oxygen-containing heterocycles have garnered considerable interest from both the scientific and synthetic communities due to their wide presence in natural products and bioactive scaffolds. Because of this, diverse strategies have been developed for their synthesis such as reductive etherification,1 Oxa-Michael addition,2 transition metal-catalyzed π-allyl cation-based transformation,3 Ag-catalyzed nucleophilic substitution,4 hetero Diels–Alder, and hydroalkoxylation/carboxylation of alkene derivatives.5

In recent years, the hydrofunctionalization of alkynes has been a very interesting and effective route for the design and synthesis of functionalized heterocycles with a complete atom-economical and step-economical strategy under mild reaction conditions.6 In this regard, hydroalkoxylation of alkynes has provided reliable routes to produce oxygen-bearing heterocycles.7 Initially, hydroalkoxylation of alkenes was widely explored for the synthesis of saturated heterocycles.8 However, using alkyne substrates instead of alkenes offers wider synthetic possibilities due to the possibility of accessing and isolating the reactive “enol ether” intermediates, which have been reported to participate in different cascade processes.9 According to the Baldwin’s rules, the hydroalkoxylation reaction can potentially lead to the formation of the exo- and/or endo-heterocycles.10 The regioselectivity of the process has been found to be dependent on the metal used, the length of the hydrocarbon chain linking the alcohol and alkyne moieties, and whether the alkyne functionality is terminal or internal.8b,11

In recent decades, an extensive library of catalysts based on metal complexes has been published for this transformation. Transition metal compounds comprising iridium,12 rhodium,13 gold,14 palladium,15 ruthenium,16 silver,17 platinum,5a,18 iron,19 and copper20 have shown to catalyze this reaction efficiently via a metal–alkynyl species by selectively activating the alkyne moiety of the substrate. In addition, s-block and rare-earth complexes have also proven to be highly active for this transformation.21,22 However, in this case, the reaction proceeds via the formation of a metal–alkoxide intermediate, which is generated by activating the hydroxyl group of the alkynol substrate.

Despite progress in this field, the majority of hydroalkoxylation processes are catalyzed by highly expensive and less abundant metals. Therefore, the use of nonprecious metals has become highly desirable in terms of sustainability and environmental criteria.23,24 Although zinc has been widely studied for the synthesis of compounds by C–N and C–O bond formation reactions,25 there are scarce examples for the intramolecular hydroalkoxylation of alkynols. Recently, our research group has reported the first zinc catalysts for the hydroalkoxylation of different aromatic and aliphatic alkynyl alcohols, achieving high conversions under mild reaction conditions and 100% selectivity toward the cyclized exo-product (Scheme 1a).26

Scheme 1. (a) Previous Zinc-Catalyzed Hydroalkoxylation of Alkynol Substrates and (b) This work: Zinc-Catalyzed Hydroelementation of Alkynol/Alkynoic Substrates.

On the other hand, the hydrocarboxylation of alkynyl acid substrates has been less studied than their hydroalkoxylation analogs. This reaction yields various types of unsaturated lactones, which are prevalent structural motifs in natural and bioactive products, as well as useful compounds for the pharmaceutical and fragrance industries.27 Numerous transition metal catalysts have been reported for this process, especially iridium,28 rhodium,29 palladium,30 silver,31 and gold.32 The cycloisomerization reaction entails the π-activation of the C=C bond within the alkynoic acid. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no precedents employing zinc catalysts for this reaction. Recently, Higashida et al. reported a series of gold–zinc catalysts for the 7-exo-dig hydrocarboxylation of nonactivated internal alkynes featuring flexible linker chains to produce ε-exo-alkylidene ε-lactones. The proximity between the gold and zinc sites was found crucial for high catalytic activity and cooperativity through a dual activation of the alkyne with a cationic gold atom and the carboxylic acid with a basic zinc salt.32b

Herein, we report the intramolecular hydroelementation reaction of a wide range of alkynyl alcohols and acid substrates catalyzed by novel acetamidate/thioacetamidate zinc complexes, becoming the first zinc catalysts reported for the cycloisomerization of alkynoic substrates. Kinetic and mechanistic studies have been performed for the hydroalkoxylation process, pointing to a mechanism through the activation of the substrate by the oxidizing element and the formation of a metal–alkoxide intermediate. The activation parameters have also been calculated and showed to be lower than those reported for previously used scorpionate zinc catalysts.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Structural Characterization

Heteroscorpionate acetamidate and thioacetamidate ligands have been thoroughly investigated and coordinated to a diverse range of metals (aluminum, rare-earth metals) due to their great versatility in their coordination mode.33 These ligands contain two Lewis basic coordinating groups (N and O/S centers), and this makes them of great interest in synthetic chemistry.33 Drawing upon this, we have now focused on the preparation of alkyl zinc complexes 1–5 by a reaction of the corresponding protonated acetamidate or thioacetamidate heteroscorpionate precursor [bpzpamH (L1), bpzfamH (L2), (S)-bpzmpamH (L3), bpzptamH (L4), and bpzatamH (L5)] with ZnEt2 in a 1:1 molar ratio in toluene at room temperature for 2 h. This reaction resulted in the formation of mononuclear ethyl zinc complexes [Zn(Et)(κ3-bpzpam)] (1), [Zn(Et)(κ3-bpzfam)] (2), [Zn(Et)(κ3-(S)-bpzmpam)] (3), [Zn(Et)(κ3-bpzptam)] (4), and [Zn(Et)(κ3-bpzatam)] (5) with vigorous elimination of ethane (Scheme 2). Complexes 1–5 are white solids and were obtained in excellent yields after the appropriate workup procedure. These compounds were obtained as achiral complexes except for compound 3, which was isolated as an enantiomerically enriched compound. These complexes have shown to be stable against temperature and when they are exposed to air in solid state for several days.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Zinc Complexes 1–5.

Complexes 1–5 were structurally characterized by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction analysis. 13C{1H} NMR spectroscopy has been a great tool to deduce how the acetamidate–thioacetamide moiety of the ligand is coordinated to the zinc atom. In this sense, and in contrast to aluminum analogs,33c,e acetamidate zinc complexes 1–3 exhibited a nitrogen coordination of the acetamidate moiety, as expected according to Pearson’s HSAB theory, in which the zinc atom displays an intermediate acidic hardness behavior.34 This was confirmed by the acetamidate carbon resonance, which exhibited a downfield shift compared to that of the neutral ligand (Table S1). On the other hand, thioacetamidate zinc complexes 4 and 5 showed two sets of signals for the thioacetamidate moiety in 13C{1H} NMR spectra. This represents a clear indication of the presence of two different isomers depending on the coordination mode of the thioacetamidate ligand (N or S) since both atoms display similar chemical hardness. The ratio of the isomer coordinated through the sulfur atom was found to be higher than that of its nitrogen counterpart for complex 5, as the resonance assigned to the thioacetamidate carbon shifted to a higher field than that of the neutral ligand. This observation was ascribed to the steric hindrance of the ligand, which was shown to be higher for the adamantyl moiety in complex 5 than its phenyl analog 4.

The 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra of zinc complexes 1,2, 4, and 5, which contain nonchiral ligands, displayed a single set of resonances for the H4, Me3, and Me5 pyrazole protons, and these data confirm the equivalence of the two pyrazole rings (Figures S1–S5). On the contrary, complex 3, which contains a stereogenic center in the heteroscorpionate ligand (S)-bpzmpam, revealed two different sets of signals for some of the protons and carbons at the 3, 4, and 5 positions of the pyrazole rings, indicating the nonequivalence between them (Figure S3). The spectroscopic data confirm a tetrahedral geometry around the zinc atom with the heteroscorpionate ligand linked in a monofacial tridentate form, κ3-NNN or κ3-NNS, and the ethyl ligand occupies the fourth position of the coordination sphere. 1H-NOESY-2D experiments enabled the clear assignment of all 1H resonances, while the assignment of the 13C{1H} NMR signals was accomplished using 1H–13C heteronuclear correlation (g-HSQC) experiments.

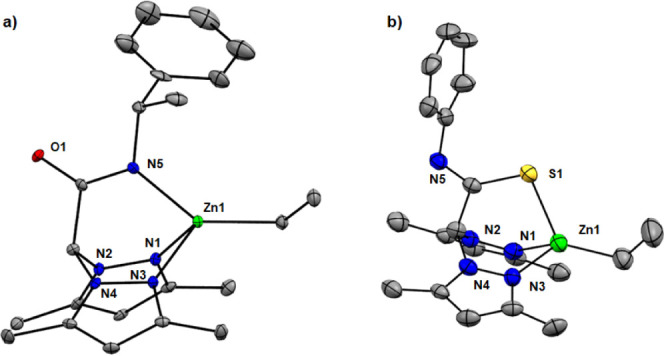

The crystal structures of compounds 3 and 4 (major isomer) were corroborated by X-ray diffraction studies (Figure 1), and these structures are consistent with the solution proposed structures inferred from the spectroscopic data. These compounds exhibited a mononuclear structure with the ligand coordinated to the metal center through the nitrogen atom from the acetamidate group, the two nitrogen atoms of the pyrazole rings in a κ3-NNN monofacial tridentate mode for complex 3 (Figure 1a), and the sulfur atom of the thiacetamidate moiety in a κ3-NNS coordination fashion for complex 4 (major isomer) (Figure 1b). In addition, an ethyl group is bonded to the zinc center in complexes 3 and 4 (major isomer), occupying the fourth vacancy and completing the coordination sphere around the zinc atom.

Figure 1.

ORTEP diagrams for compounds 3 (a) and 4 (major isomer) (b).

Selected bond distances and angles, and the crystallographic data are provided in Tables S3 and S4, respectively. The Zn–Cethyl [1.981(5) and 1.98(1) Å] and Zn–Npyrazole [2.072(7)–2.143(4) Å] bond distances are consistent with those previously reported for alkyl zinc scorpionate compounds.26,35 The bond length Zn(1)–N(5) in complex 3 of 2.002(4) Å is shorter than Zn(1)–N(1) and Zn(1)–N(3) bond lengths of 2.143(4) and 2.109(4) Å, respectively, from the pyridinic nitrogen of both pyrazole rings, confirming the anionic fashion of this bond. The bond distance O(1)–C(14) of 1.248(6) Å for complex 3 confirms the localization of the double bond in the acetamidate moiety in this bond, which is similar to the C=O double bond theoretical distance of 1.220 Å.36 On the other hand, the bond distance N(5)–C(12) of 1.28(1) Å in complex 4 (major isomer) is very similar to that found for N=C double bond of 1.279 Å.36 The geometry at both zinc atoms is a distorted tetrahedral, with the most significant distortion observed in the N(3)–Zn(1)–N(1) bond angles for complexes 3 and 4 (major isomer), with values of 84.2(2)° and 85.6(3)°, respectively. Additionally, the dihedral angle between the C(1)–Zn(1)–N(5) and N(3)–Zn(1)–N(1) planes is 86.5° for complex 3, and the dihedral angle between the C(19)–Zn(1)–S(1) and N(3)–Zn(1)–N(1) planes is 88.4° for complex 4 (major isomer), further confirming this distorted geometry.

Catalytic Hydroalkoxylation/Hydrocarboxylation Studies

Following our previous methodology,26 compounds 1–5 were evaluated as catalysts in the hydroelementation reaction of alkynyl alcohols and alkynyl acid substrates. Initially, a first screening to evaluate the catalytic activity of compounds 1–5 was performed for the intramolecular hydroalkoxylation of 2-ethynylbenzyl alcohol (6) (Table 1). The reactions were conducted in a J-Young NMR tube at 80 °C in toluene-d8, utilizing a catalyst loading of 2.5 mol % (Table 1, entries 1–5). Acetamidate compounds (1–3) showed to be slightly more active than thioacetamide complexes (4 and 5), with complex 1 being the most active, achieving 92% conversion after 5 h (Table 1, entry 1; Figure S6). In terms of selectivity, it is worth noting that all complexes were 100% selective toward the hydroalkoxylation of substrate 6, forming the exo-cyclic enol ether 7 with no evidence of the alternative 6-endo-cyclization. This result aligns well with previously reported findings for other zinc complexes.26

Table 1. Hydroalkoxylation/Cyclization Reaction of 2-Ethynylbenzyl Alcohol (6) by Catalysts 1–5a.

| entry | catalyst | conv. (%)b | TOF (h–1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 93 | 7.4 |

| 2 | 2 | 76 | 6.0 |

| 3 | 3 | 65 | 5.2 |

| 4 | 4 | 77 | 6.2 |

| 5 | 5 | 51 | 4.1 |

Reaction conditions: 0.5 mmol substrate, 0.0125 mmol catalyst, 0.6 mL toluene-d8, 80 °C, 5 h. Determined by 1H NMR.

TOF = (mol of product/mol of cat. × time).

After having optimized the reaction conditions for the hydroalkoxylation of 2-ethynylbenzyl alcohol (6), we investigated the substrate scope and studied the cyclization of different aliphatic alkynyl alcohols and acids (Table 2, entries 1–8; Figures S7–S11). These substrates proved to be more challenging than compound 6. Thus, harsher reaction conditions were employed, increasing the catalyst loading and reaction temperature. As it can be observed, there is a strong dependence between the conversion and the structure for these substrates, since they are not aligned to form the cyclized product. These results evidence the influence of the Thorpe–Ingold effect37,38 of the geminal substituents with respect to the alcohol/carboxylic acid group and the electronic effects of the aromatic substituents in the hydroelementation reaction of these substrates. In terms of selectivity, it is worth noting that only the hydroalkoxylation of 4-pentynol (8) afforded the formation of both cyclization products, the exo-furane 8′ and endo-2-pyrene 8″ derivatives in a 67:33 ratio. All other substrates were 100% selective toward the formation of the exo-cyclic product. In the hydrocarboxylation of substrates 10 and 11, unsaturated exo-lactones 10′ and 11′ were obtained. Lactone 11′ was obtained in a lower yield than its 10′ analogs, due to the lower stability of the 6-membered ring in comparison to the 5-membered one.

Table 2. Cyclization Reaction of Alkynyl Alcohols/Carboxylic Acids Catalyzed by Compound 1a.

Reaction conditions: 0.5 mmol substrate, 0.025 mmol catalyst, 0.6 mL toluene-d8, 90 °C, 16 h.

Determined by 1H NMR.

Selectivity to the exo-product.

TOF = (mol of product/mol of cat. × time).

Finally, to demonstrate the functional group tolerance of complex 1, the catalytic cyclization of some internal alkyne derivatives was evaluated (Table 2, entries 5–8; Figures S12–S14). As can be observed, catalyst 1 proved to be very efficient in the catalytic intramolecular hydroalkoxylation of SiMe3-substituted substrates 12 and 13, achieving conversion rates of 88%. It is also noteworthy that the desired cyclized products 12′ and 13′ were obtained with high selectivity despite the formation of the corresponding SiMe3-protected starting materials and SiMe3-deprotected products. The substitution of the trimethylsilyl moiety for a phenyl group in the alkyne function (substrate 14) led to a significant decrease in the conversion rate (42%) compared to 13, consistent with the previously reported one.22f,h On the other hand, the cyclization of the internal alkynyl acid 15 using compound 1 as a catalyst was also successful, achieving a conversion similar to that obtained for the analogous nonterminal substrate 11.

Kinetic and Mechanistic Studies

Kinetic studies were performed using 2-ethynylbenzyl alcohol (6) as a substrate and alkyl zinc complex 1 as a catalyst. The essays were performed in a J-Young NMR tube at 80 °C in toluene-d8 and the reaction was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure S17). The order of the reaction with respect to substrate 6 was studied first, and this intramolecular hydroalkoxylation reaction was carried out at four different concentrations of alkynyl alcohol 6 (0.035–0.600 M), while maintaining a constant catalyst 1 concentration of 0.007 M. The linear correlation between [6] and time indicated that the reaction is zero-order with respect to the substrate concentration (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Plot of [6] versus reaction time for the hydroalkoxylation of 6 catalyzed by catalyst 1 at various initial concentrations of 6.

To determine the order with respect to zinc compound 1, the same procedure was followed, and the cyclization reaction of substrate 6 was carried out at four different concentrations of complex 1 (0.007–0.035 M), while maintaining a constant concentration of substrate 6 of 0.600 M (Figure S18). As it can be observed, as the catalyst concentration increases, so does the reaction rate for the hydroalkoxylation process. The plot of kobs versus [1] displayed a strong linear fit, suggesting that the reactions follow first-order kinetics with respect to catalyst concentration (Figure 3a). This result was further supported by plotting log [1] against log kobs, revealing a slope of 1.101 (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Plot of kobs versus [1] for the hydroalkoxylation of 6. (b) Plot of log kobs versus log [1].

Having established the equation rate for the hydroalkoxylation process and the order with respect to substrate 6 and catalyst 1, a kinetic study at variable temperatures was conducted to determine the activation parameters. Reactions were performed at four temperatures ranging from 60 to 90 °C, and their progress was monitored by using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Linear plots in all cases supported that reactions proceeded with zero-order kinetics with respect to the concentration of substrate 6 (Figure 4). Standard Arrhenius and Eyring plots were utilized to calculate the activation parameters (Figures S19 and S20, respectively). The activation energy (Ea), enthalpy (ΔH⧧), and entropy (ΔS⧧) were determined to be 24.5(±0.2) kcal/mol, 23.8(±0.2) kcal/mol, and −12.5(±0.2) eu, respectively. The values of Ea and ΔH⧧ for catalyst 1 closely resemble those reported previously for other scorpionate zinc complexes.26

Figure 4.

Plot of substrate consumption over time during the hydroalkoxylation of 6 by catalyst 1 at varying temperatures.

With the aim of obtaining a better understanding of the hydroalkoxylation mechanism, the stoichiometric reaction of complex 1 with 2-ethynylbenzyl alcohol (6) was explored. Interestingly, and in contrast to what was previously observed with other scorpionate zinc complexes,26 the latter reaction afforded a mixture of unidentified reaction intermediates and exo-cyclic product 7 even under mild conditions. This result prompted the investigation of the mechanism in more detail. To this end, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed at the dispersion-corrected PCM-(toluene)-B3LYP-D3/def2-SVP level (see computational details in the Supporting Information). The overall free energy profiles for the catalytic alkyne hydroalkoxylation are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Gibbs free energy profile (in kcal/mol) for zinc-catalyzed hydroalkoxylation of 6. Computed at the PCM-(toluene)-B3LYP-D3/def2-SVP level. Black lines represent the more plausible catalytic route. Blue lines represent alternative reaction paths to the catalytic cycle that are not favorable.

As depicted in Figure 5, this reaction initiates with the deprotonation of the alkyne or the hydroxyl group of substrate 6 via alkane elimination, forming the corresponding alkynyl (INT-A) or the alkoxide intermediate (INT-A′). Notably, the formation of the alkoxide intermediate is slightly more exergonic (approximately 4.2 kcal/mol) than that of the alternative alkynyl activation. Subsequently, a concerted coupling reaction between the alkyne group and the Zn–O moiety occurs via the transition state TS1-A′ (ΔG⧧ = 20.9 kcal/mol), which is kinetically more favored over the alternative nucleophilic attack of the hydroxyl on the alkynyl–Zn bond. In addition, the latter pathway via transition state TS1-A appears unfeasible due to its much higher computed barrier (ΔG⧧ = 48.9 kcal/mol). Therefore, the catalytic cycle operates through the formation of the alkoxide intermediate (INT-A′) to yield the cyclized product (INT-B′), releasing 16.4 kcal/mol (compared to INT-A′). The cyclization step possibly serves as the rate-determining step along this pathway.

Moreover, the calculations reveal the release of a slight amount of free energy after a second substrate molecule coordinates to the metal center, forming INT-C′. Finally, an exergonic proton transfer (ΔG = −13.0 kcal/mol) from the hydroxyl group of the coordinated substrate to the cyclized product is observed via transition state TS2-C′. The cyclized product is then removed, and a new substrate molecule is incorporated, restoring the alkoxide intermediate INT-A′.

Conclusions

Novel zinc acetamide/thioacetamidate scorpionate compounds were synthesized and characterized. These complexes were evaluated as catalysts in the cyclization reaction of alkynyl alcohol/acid substrates, achieving good conversions under milder reaction conditions and catalyst loadings lower than those reported previously. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this represents the first use of zinc catalysts for the hydroalkoxylation of nonterminal alkynyl alcohols and the hydrocarboxylation of alkynyl acid substrates. The cyclization process has shown to be fully selective toward the exo-product in most of the cases. Kinetic studies have shown a zero-order dependence on substrate concentration and first-order dependence with respect to catalyst concentration. Finally, DFT calculations agree with the formation of an alkoxide intermediate as the catalytically active species and have pointed to the C≡C bond insertion to the alkoxide intermediate as the rate-determining step of the reaction. Additional investigations are underway to broaden the range of substrates in intermolecular hydroalkoxylation/hydrocarboxylation processes.

Experimental Section

All handling of air- and moisture-sensitive compounds was conducted under dry nitrogen using either a Braun Labmaster glovebox or standard Schlenk line techniques. NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Ascend TM-500 spectrometer and referenced to the residual deuterated solvent. Elemental analyses were performed using a PerkinElmer 2400 CHN analyzer. Solvents were predried over sodium wire (toluene, THF, n-hexane) and distilled under nitrogen from sodium (toluene, THF) or sodium–potassium alloy (n-hexane). Deuterated solvents were stored over activated 4 Å molecular sieves and degassed by several freeze–thaw cycles. 2-Ethynylbenzyl alcohol (6), 4-pentynol (8), 5-hexynol (9), 5-(trimethylsilyl)-4-pentynol (10), 5-pentenoic acid (11), and 5-hexenoic acid (12) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Substrates (2-((trimethylsilyl)ethynyl)phenyl)methanol (13), (2-(phenylethynyl)phenyl)methanol (14), and 6-bromo-5-hexynoic acid (15) were synthesized as previously described in the literature.22f,39 All other reagents were procured from standard commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Safety statements: No uncommon hazards are noted.

Synthesis of [Zn(Et)(κ3-bpzpam)] (1)

In a 100 mL Schlenk tube, bpzpamH (L1) (0.50 g, 1.55 mmol) was dissolved in dry toluene (25 mL) and cooled to −50 °C. Then, a solution of ZnEt2 (1 M in n-hexane, 1.55 mL, 1.55 mmol) was added, and the mixture was allowed to warm up and stirred for 1 h. After that time, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was washed with n-hexane to afford complex 1 as a white solid. Yield: 0.61 g (95%). Anal. Calcd for C20H25N5OZn: C, 57.6; H, 6.1; N, 16.8. Found: C, 57.8; H, 6.3; N, 16.4. 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): δ 8.18 (d, JHH = 7.0 Hz, 2H, oH-Ar), 7.34 (m, JHH = 7.0 Hz, 2H, mH-Ar), 6.98 (t, JHH = 7.0 Hz, 1H, pH-Ar), 6.74 (s, 1H, CH), 5.22 (s, 2H, H4), 1.99 (s, 6H, Me3), 1.82 (t, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 3H, ZnCH2CH3), 1.79 (s, 6H, Me5), 1.10 (m, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 2H, ZnCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): 164.6 (NCO), 149.8; 140.6 (C3, C5), 147.9 (Ci-Ar), 128.1 (Cm-Ar), 124.4 (Cp-NAr), 122.4 (C°-NAr), 106.1 (C4), 71.1 (CH), 13.5 (ZnCH2CH3), 12.3 (Me3), 10.0 (Me5), 1.4 (ZnCH2CH3).

Synthesis of [Zn(Et)(κ3-bpzfam)] (2)

The synthesis of 2 was performed by following the same procedure as that for compound 1, using bpzfamH (L2) (0.50 g, 1.22 mmol) and ZnEt2 (1 M in n-hexane, 1.22 mL, 1.22 mmol). Compound 2 was isolated as a white solid. Yield: 0.55 g (90%). Anal. Calcd for C27H29N5OZn: C, 64.2; H, 5.8; N, 13.9. Found: C, 64.3; H, 5.9; N, 13.7 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): δ 8.32–7.00 (m, 7H, Ar-Flu), 6.67 (s, 1H, CH), 5.21 (s, 2H, H4), 3.56 (s, 2H, CH2-Flu), 1.96 (s, 6H, Me3), 1.86 (t, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 3H, ZnCH2CH3), 1.77 (s, 6H, Me5), 1.04 (m, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 2H, ZnCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): 164.5 (NCO), 149.5; 140.9 (C3, C5), 129.9–119.9 (Ar-Flu), 106.2 (C4), 71.2 (CH), 36.8 (CH2-Flu), 13.0 (ZnCH2CH3), 12.5 (Me3), 10.0 (Me5), −2.0 (ZnCH2CH3).

Synthesis of [Zn(Et)(κ3-(S)-bpzmpam)] (3)

The synthesis of 3 was conducted by following the same procedure as that for compound 1 using (S)-bpzmpamH (L3) (0.50 g, 1.42 mmol) and ZnEt2 (1 M in n-hexane, 1.42 mL, 1.42 mmol). Compound 3 was isolated as a white solid. Yield: 0.59 g (94%). Anal. Calcd for C22H29N5OZn: C, 59.4; H, 6.6; N, 15.7. Found: C, 59.6; H, 6.8; N, 15.4 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): δ 7.49 (d, JHH = 7.0 Hz, 2H, oH-Ar), 7.20 (m, JHH = 7.0 Hz, 2H, mH-Ar), 7.02 (t, JHH = 7.0 Hz, 1H, pH-Ar), 6.99 (brs, 1H, CH), 5.74 (m, 1H, CHMePh), 5.25; 5.22 (s, 2H, H4,4′), 2.07; 2.06 (s, 6H, Me3,3′), 1.75 (brs, 3H, CHMePh), 1.70 (t, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 3H, ZnCH2CH3), 1.65; 1.62 (s, 6H, Me5,5′), 0.65 (m, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 2H, ZnCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): 165.8 (NCO), 149.0; 148.8; 148.2; 140,8; 140.6 (C3,3′,5,5′ and Ci-Ar), 127.9 (Cm-Ar), 126.6 (Cp-Ar), 125.8 (C°-Ar), 105.9; 105.8 (C4,4′), 70.0 (CH), 52.0 (CHMePh), 24.0 (CHMePh), 13.5 (ZnCH2CH3), 12.3; 12.2 (Me3,3′), 10.1; 10.0 (Me5,5′), −1.8 (ZnCH2CH3).

Synthesis of [Zn(Et)(κ3-bpzptam)] (4)

The synthesis of 4 was conducted by following the same procedure as that for compound 1 using bpzptamH (L4) (0.50 g, 1.48 mmol) and ZnEt2 (1 M in n-hexane, 1.48 mL, 1.48 mmol). Compound 4 was isolated as a white solid. Yield: 0.61 g (95%). Anal. Calcd for C20H25N5SZn: C, 55.5; H, 5.8; N, 16.2. Found: C, 55.7; H, 5.9; N, 16.0 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): Major isomer (κ3-NNS): δ 7.40 (d, JHH = 7.0 Hz, 2H, oH-Ar), 7.22 (m, JHH = 7.0 Hz, 2H, mH-Ar), 7.01 (s, 1H, CH), 6.95 (t, JHH = 7.0 Hz, 1H, pH-Ar), 5.31 (s, 2H, H4), 2.05 (s, 6H, Me3), 1.86 (s, 6H, Me5), 1.84 (t, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 3H, ZnCH2CH3), 1.00 (m, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 2H, ZnCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): 171.7 (NCS), 149.9; 141.1 (C3, C5), 151.8 (Ci-Ar), 128.8 (Cm-Ar), 123.9 (Cp-NAr), 122.3 (C°-NAr), 106.6 (C4), 74.3 (CH), 13.9 (ZnCH2CH3), 12.9 (Me3), 10.6 (Me5), −1.2 (ZnCH2CH3). Minor isomer (κ3-NNN): δ 7.66 (d, JHH = 8.5 Hz, 2H, oH-Ar), 7.54 (s, 1H, CH), 7.23 (m, JHH = 8.5 Hz, 2H, mH-Ar), 6.95 (t, JHH = 8.5 Hz, 1H, pH-Ar), 5.26 (s, 2H, H4), 1.97 (s, 6H, Me3), 1.94 (s, 6H, Me5), 1.65 (t, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 3H, ZnCH2CH3), 0.85 (m, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 2H, ZnCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): 187.2 (NCS), 149.9; 141.8 (C3, C5), 150.1 (Ci-Ar), 128.6 (Cm-Ar), 125.0 (Cp-Ar), 124.6 (C°-Ar), 105.4 (C4), 77.5 (CH), 13.5 (ZnCH2CH3), 12.8 (Me3), 10.7 (Me5), −2.7 (ZnCH2CH3).

Synthesis of [Zn(Et)(κ3-bpzatam)] (5)

The synthesis of 5 was performed by following the same procedure as that for compound 1 using bpzatamH (L5) (0.50 g, 1.26 mmol) and ZnEt2 (1 M in n-hexane, 1.26 mL, 1.26 mmol). Compound 5 was isolated as a white solid. Yield: 0.53 g (85%). Anal. Calcd for C24H35N5SZn: C, 58.7; H, 7.2; N, 14.3. Found: C, 58.9; H, 7.5; N, 14.0. Major isomer (κ3-NNS): 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): δ 6.83 (s, 1H, CH), 5.31 (s, 2H, H4), 2.51 (brs, 6H, CH2a), 2.07 (m, 3H, CHb), 2.04 (s, 6H, Me3), 1.90 (t, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 3H, ZnCH2CH3), 1.88 (s, 6H, Me5), 1.69 (m, 6H, CH2c), 1.03 (m, JHH = 8.1 Hz, 2H, ZnCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): 164.1 (NCS), 149.0; 140.5 (C3, C5), 106.0 (C4), 76.0 (CH), 57.0–30.1 (Ad), 13.7 (ZnCH2CH3), 12.6 (Me3), 10.4 (Me5), −1.6 (ZnCH2CH3). Minor isomer (κ3-NNN): 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): δ 7.00 (s, 1H, CH), 5.46; 5.24 (s, 2H, H4,4′), 2.78; 2.60; 2.51 (brs, 6H, CH2a), 2.07 (s, 3H, CHb), 2.04 (s, 6H, Me3), 1.94 (s, 6H, Me5), 1.83 (m, 3H, ZnCH2CH3), 1.72–1.50 (m, 6H, CH2c), 0.91 (m, 2H, ZnCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, C6D6, 297 K): 184.9 (NCS), 149.0; 141.1 (C3, C5), 106.2 (C4,4′), 79.7 (CH), 58.4–29.0 (Ad), 13.3 (ZnCH2CH3), 12.4 (Me3), 10.8 (Me5), 1.3 (ZnCH2CH3).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación/Agencia Estatal de Investigación, Spain (Grants PID2020-117788RB-100/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, RED2022-134287-T), Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha through “Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER)” (Grant SBPLY/21/180501/000132), Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha through “Fondo Social Europeo Plus (FSE+)” (Grant SBPLY/22/180502/000056), and Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha (Grant 2021-GRIN-31240).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c00832.

The synthesis of complexes 1–5, catalytic intramolecular hydroalkoxylation, spectra of 1H and 13C{1H} NMR for complexes 1–5, kinetic measurements and representative kinetic plots, and X-ray crystallographic data for compounds 3 and 4 (major isomer) (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Fu J.; Vaughn Z.; Nolting A. F.; Gao Q.; Yang D.; Schuster C. H.; Kalyani D. Diastereoselective reductive etherification via high-throughput experimentation: Access to pharmaceutically relevant alkyl ethers. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 13454. 10.1021/acs.joc.3c00822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gharpure S. J.; Prasad J. V. K. Stereoselective synthesis of C-substituted morpholine derivatives using reductive etherification reaction: Total synthesis of chelonin C. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 10325. 10.1021/jo201975b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Xu T.; Chen K.; Zhu H. Y.; Hao W. J.; Tu S. J.; Jiang B. Yb(OTf)3-catalyzed alkyne-carbonyl metathesis-oxa-Michael addition relay for diastereoselective synthesis of functionalized naphtho[2,1-b]furans. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 2414. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c00613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang Y.; Du D. M. Recent Advances in organocatalytic asymmetric oxa-Michael addition triggered cascade reactions. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 3266. 10.1039/D0QO00631A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zheng X.; Chen J.; Li Z.; Zhong L.; Zhan R.; Huang H. Organocatalytic oxa-Michael/Michael addition/deformylation cascade reaction of 3-formylchromone with p-quinol: Synthesis of the furanochromanone skeleton. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 4402. 10.1002/adsc.202201145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang Y.; Zhang W. Y.; You S. L. Ketones and aldehydes as O-nucleophiles in iridium-catalyzed intramolecular asymmetric allylic substitution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2228. 10.1021/jacs.8b13182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fernandes R. A.; Nallasivam J. L. Catalytic allylic functionalization via π-allyl palladium chemistry. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 8647. 10.1039/C9OB01725A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Weibel J. M.; Blanc A.; Pale P. Ag-mediated reactions: Coupling and heterocyclization reactions. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 3149. 10.1021/cr078365q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Poola S.; Shaik M. S.; Sudileti M.; Yakkate S.; Nalluri V.; Chippada A.; Cirandur S. R. Nano CuO–Ag-catalyzed synthesis of some novel pyrano[2,3-d] pyrimidine derivatives and evaluation of their bioactivity. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2020, 67, 805. 10.1002/jccs.201900256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhou Y.; Xu X.; Sun H.; Tao G.; Chang X.-Y.; Xing X.; Chen B.; Xu C. Development of highly efficient platinum catalysts for hydroalkoxylation and hydroamination of unactivated alkenes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1. 10.1002/ejic.201901016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rocard L.; Chen D.; Stadler A.; Zhang H.; Gil R.; Bezzenine S.; Hannedouche J. Earth-abundant 3d transition metal catalysts for hydroalkoxylation and hydroamination of unactivated alkenes. Catalysts 2021, 11, 674. 10.3390/catal11060674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kennemur J. L.; Maji R.; Scharf M. J.; List B. Catalytic asymmetric hydroalkoxylation of C-C multiple bonds. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 14649. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cadierno V. Metal-catalyzed hydrofunctionalization reactions of haloalkynes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, (1–12), 886. 10.1002/ejic.201901016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Cheng Z.; Guo J.; Lu Z. Recent advances in metal-catalysed asymmetric sequential double hydrofunctionalization of alkynes. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 2229. 10.1039/D0CC00068J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nanda S. K. Metal-Free Intramolecular Hydroalkoxylation of Alkyne: Recent Advances. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 8511. 10.1002/slct.202102426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Nanda S. K.; Mallik R. Transition metal-catalyzed hydroalkoxylation of alkynes: An overview. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 15571. 10.1002/chem.202102194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Rodriguez-Ruiz V.; Carlino R.; Bezzenine-Lafollée S.; Gil R.; Prim D.; Schulz E.; Hannedouche J. Recent developments in alkene hydro-functionalisation promoted by homogeneous catalysts based on earth abundant elements: Formation of C–N, C–O and C–P bond. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 12029. 10.1039/C5DT00280J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Abbiati G.; Beccalli E. M.; Rossi E.. Groups 9 and 10 Metals-catalyzed O–H bond addition to unsaturated molecules. In Hydrofunctionalization. Springer: 2013, 231–290.. [Google Scholar]

- a Ge S.; Cao W.; Kang E.; Hu B.; Zhang H.; Su Z.; Liu X.; Feng X. Bimetallic catalytic asymmetric tandem reaction of β-alkynyl ketones to synthesize 6,6-spiroketals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4017–4021. 10.1002/anie.201812842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li D. Y.; Chen H. J.; Liu P. N. Tunable cascade reactions of alkynols with alkynes under combined Sc(OTf)3 and rhodium catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 373. 10.1002/anie.201508914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J. E. Rules for ring closure. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1976, 18, 734. 10.1039/c39760000734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Cheng Z.; Guo J.; Lu Z. Recent advances in metal-catalysed asymmetric sequential double hydrofunctionalization of alkynes. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 2229. 10.1039/D0CC00068J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bruneau C.Group 8 metals-catalyzed O–H bond addition to unsaturated molecules. In Hydrofunctionalization. Springer: 2011, 203–230.. [Google Scholar]; c Hintermann L. Recent developments in metal-catalyzed additions of oxygen nucleophiles to alkenes and alkynes. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2010, 31, 123. 10.1007/978-3-642-12073-2_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Messerle B. A.; Vuong K. Q. Rhodium- and iridium-catalyzed double hydroalkoxylation of alkynes, an efficient method for the synthesis of O,O-acetals: catalytic and mechanistic studies. Organometallics 2007, 26, 3031. 10.1021/om061106r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Chin C. S.; Won G.; Chong D.; Kim M.; Lee H. Carbon-carbon bond formation involving reactions of alkynes with group 9 metals (Ir, Rh, Co): preparation of conjugated olefins. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 218. 10.1021/ar000090c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Genin E.; Antoniotti S.; Michelet V.; Genêt J. P. An Ir(I)-catalyzed exo-selective tandem cycloisomerization/hydroalkoxylation of bis-homopropargylic alcohols at room temperature. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4949. 10.1002/anie.200501150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Man B. Y. W.; Bhadbhade M.; Messerle B. A. Rhodium(I) complexes bearing N-donor ligands: Catalytic activity towards intramolecular cyclization of alkynoic acids and ligand lability. New J. Chem. 2011, 35, 1730. 10.1039/c1nj20094a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Liu Z.; Breit B. Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective intermolecular hydroalkoxylation of allenes and alkynes with alcohols: Synthesis of branched allylic ethers. Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 8580. 10.1002/ange.201603538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kondo M.; Kochi T.; Kakiuchi F. Rhodium-catalyzed anti-Markovnikov intermolecular hydroalkoxylation of terminal acetylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 32. 10.1021/ja1097385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Veenboer R. M. P.; Dupuy S.; Nolan S. P. Stereoselective gold(I)-catalyzed intermolecular hydroalkoxlation of alkynes. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 1330. 10.1021/cs501976s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Soklou K. E.; Marzag H.; Bouillon J. P.; Marchivie M.; Routier S.; Plé K. Gold(I)-catalyzed intramolecular hydroamination and hydroalkoxylation of alkynes: access to original heterospirocycles. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 5973. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zi W.; Toste F. D. Gold(I)-catalyzed enantioselective desymmetrization of 1,3-diols through intramolecular hydroalkoxylation of allenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 14447. 10.1002/anie.201508331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gligorich K. M.; Schultz M. J.; Sigman M. S. Palladium(II)-catalyzed aerobic hydroalkoxylation of styrenes containing a phenol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2794. 10.1021/ja0585533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Patil N. T.; Lutete L. M.; Wu H.; Pahadi N. K.; Gridnev I. D.; Yamamoto Y. Palladium-catalyzed intramolecular asymmetric hydroamination, hydroalkoxylation, and hydrocarbonation of alkynes. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 4270. 10.1021/jo0603835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Oe Y.; Ohta T.; Ito Y. Ruthenium-catalyzed addition reaction of alcohols across olefins. Synlett 2005, 1, 179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Iio K.; Sachimori S.; Watanabe T.; Fuwa H. Ruthenium-catalyzed intramolecular double hydroalkoxylation of internal alkynes. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 7851. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X. F.; Guo X. Y.; Gu Z. Y.; Wei L. S.; Liu L. L.; Mo D. L.; Pan C. X.; Su G. F. Silver(I)-catalyzed selective hydroalkoxylation of C2-alkynyl quinazolinones to synthesize quinazolinone-fused eight-membered N,O-heterocycles. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 2055. 10.1039/D0QO00437E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costello J. P.; Ferreira E. M. Regioselectivity influences in platinum-catalyzed intramolecular alkyne O-H and N-H additions. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9934. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bridge B. J.; Boyle P. D.; Blacquiere J. M. Endo-selective iron catalysts for intramolecular alkyne hydrofunctionalization. Organometallics 2020, 39, 2570. 10.1021/acs.organomet.0c00307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Greenhalgh M. D.; Jones A. S.; Thomas S. P. Iron-catalysed hydrofunctionalisation of alkenes and alkynes. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 190. 10.1002/cctc.201402693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Komeyama K.; Morimoto T.; Nakayama Y.; Takaki K. Cationic iron-catalyzed intramolecular hydroalkoxylation of unactivated olefins. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 3259. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.; Berhane I. A.; Chemler S. R. Copper-catalyzed enantioselective hydroalkoxylation of alkenols for the synthesis of cyclic ethers. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 7409. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairley M.; Davin L.; Hernán-Gómez A.; García-Álvarez J.; O’Hara C. T.; Hevia E. S-block cooperative catalysis: Alkali metal magnesiate-catalysed cyclisation of alkynols. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 5821. 10.1039/C9SC01598A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Martínez J.; Otero A.; Lara-Sánchez A.; Castro-Osma J. A.; Fernández-Baeza J.; Sánchez-Barba L. F.; Rodríguez A. M. Heteroscorpionate rare-earth catalysts for the hydroalkoxylation/cyclization of alkynyl alcohols. Organometallics 2016, 35, 1802. 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zhou B.; Li L.; Liu X.; Tan T. D.; Liu J.; Ye L. W. Yttrium-catalyzed tandem intermolecular hydroalkoxylation/claisen rearrangement. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 10149. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b01612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wobser S. D.; Marks T. J. Organothorium-catalyzed hydroalkoxylation/cyclization of alkynyl alcohols. scope, mechanism, and ancillary ligand effects. Organometallics 2013, 32, 2517. 10.1021/om300881b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Seo S.; Marks T. J. Lanthanide-catalyst-mediated tandem double intramolecular hydroalkoxylation/cyclization of dialkynyl dialcohols: Scope and mechanism. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 5148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Weiss C. J.; Marks T. J. Organo-f-element catalysts for efficient and highly selective hydroalkoxylation and hydrothiolation. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 6576. 10.1039/c003089a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Seo S.; Yu X.; Marks T. J. Intramolecular hydroalkoxylation/cyclization of alkynyl alcohols mediated by lanthanide catalysts. scope and reaction mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 263. 10.1021/ja8072462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Yu X.; Seo S. Y.; Marks T. J. Effective, selective hydroalkoxylation/cyclization of alkynyl and allenyl alcohols mediated by lanthanide catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 7244. 10.1021/ja071707p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Brinkmann C.; Barrett A. G. M.; Hill M. S.; Procopiou P. A.; Reid S. Alkaline earth catalysis of alkynyl alcohol hydroalkoxylation/cyclization. Organometallics 2012, 31, 7287. 10.1021/om3008663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enthaler S. Rise of the zinc age in homogeneous catalysis?. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 150. 10.1021/cs300685q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tzouras N. V.; Stamatopoulos I. K.; Papastavrou A. T.; Liori A. A.; Vougioukalakis G. C. Sustainable metal catalysis in CH activation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 343, 25. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Colonna P.; Bezzenine S.; Gil R.; Hannedouche J. Alkene hydroamination via earth-abundant transition metal (iron, cobalt, copper and zinc) catalysis: A mechanistic overview. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 1550. 10.1002/adsc.201901157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b López L. A.; González J. Zinc-catalyzed transformation of carbon dioxide. Zinc catalysis: Applications in organic synthesis. Wiley 2015, 149. 10.1002/9783527675944.ch7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Sahoo R. K.; Patro A. G.; Sarkar N.; Nembenna S. Zinc catalyzed hydroelementation (HE; E = B, C, N, and O) of carbodiimides: Intermediates isolation and mechanistic insights. Organometallics 2023, 42, 1746. 10.1021/acs.organomet.2c00610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz-Martínez F.; Fernández-Baeza J.; Sánchez-Barba L. F.; Rodríguez A. M.; Castro-Osma J. A.; Lara-Sánchez A. Zinc-catalyzed hydroalkoxylation/cyclization of alkynyl alcohols. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 5322. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c00309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Syed N.; Singh S.; Chaturvedi S.; Nannaware A. D.; Khare S. K.; Rout P. K. Production of lactones for flavoring and pharmacological purposes from unsaturated lipids: An industrial perspective. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2023, 63, 10047. 10.1080/10408398.2022.2068124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sartori S. K.; Diaz M. A. N.; Diaz-Muñoz G. Lactones: classification, synthesis, biological activities, and industrial applications. Tetrahedron 2021, 84, 132001. 10.1016/j.tet.2021.132001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Janecki T.Natural lactones and lactams: synthesis, occurrence and biological activity; Wiley, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- a Huang Y.; Zhang X.; Dong X. Q.; Zhang X. Iridium-catalyzed cycloisomerization of alkynoic acids: Synthesis of unsaturated lactones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 782. 10.1002/adsc.201901322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Wathier M.; Love J. A. Hydroelementation of Unsaturated C–C Bonds Catalyzed by Metal Scorpionate Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, (5–16), 2391. 10.1002/ejic.201501272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Fernández D. F.; Rodrigues C. A. B.; Calvelo M.; GulíGulíAs M.; MascareñMascareñAs J. L.; López F. Iridium(I)-catalyzed intramolecular cycloisomerization of enynes: scope and mechanistic course. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 7397. 10.1021/acscatal.8b02139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Sim S. H.; Lee S. I.; Park J. H.; Chung Y. K. Iridium(I)-catalyzed cycloisomerization of cyclohexadienyl alkynes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 317. 10.1002/adsc.200900578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kawaguchi Y.; Yasuda S.; Mukai C. Construction of hexahydrophenanthrenes by rhodium(I)-catalyzed cycloisomerization of benzylallene-substituted internal alkynes through C–H activation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10473. 10.1002/anie.201605640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kawaguchi Y.; Yabushita K.; Mukai C. Rhodium(I)-catalyzed cycloisomerization of homopropargylallene-alkynes through C(sp3)–C(sp) bond activation. Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 4797. 10.1002/ange.201713096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ding L.; Deng Y. H.; Sun T. Y.; Wang D.; Wu Y. D.; Xia X. F. Palladium-catalyzed divergent cycloisomerization of 1,6-enynes controlled by functional groups for the synthesis of pyrroles, cyclopentenes, and tetrahydropyridines. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 4785. 10.1039/D1QO00581B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Xia X. F.; Liu X. J.; Tang G. W.; Wang D. Palladium-catalyzed cycloisomerization of 1,6-enynes using alkyl iodides as hydride source: A combined experimental and computational study. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 4033. 10.1002/adsc.201900554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Michelet V.; Toullec P. Y.; Genêt J. P. Cycloisomerization of 1,n-enynes: Challenging metal-catalyzed rearrangements and mechanistic insights. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4268. 10.1002/anie.200701589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Liang R.-X.; Song L. I.-J.; Lu J. I.-B.; Xu W.-Y.; Ding C.; Jia Y.-X. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective heteroarenyne cycloisomerization reaction. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 7488. 10.1002/ange.202014796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jong T. T.; Williard P. G.; Porwoll J. P. Total synthesis and x-ray structure determination of cyanobacterin. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 735. 10.1021/jo00178a042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Pale P.; Chuche J. Silver assisted heterocyclization of acetylenic compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 6447. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)96884-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Dalla V.; Pale P. Silver-catalyzed heterocyclization: First total synthesis of the naturally occurring cis 2-hexadecyl-3-hydroxy-4-methylene butyrolactone. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 3525. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)73226-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Marshall J. A.; Wolf M. A.; Wallace E. M. Synthetic routes to allenic acids and esters and their stereospecific conversion to butenolides. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 367. 10.1021/jo9618740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Dalla V.; Pale P. Silver-catalyzed cyclization of acetylenic alcohols and acids: a remarkable accelerating effect of a propargylic C-O bond. New J. Chem. 1999, 23, 803. 10.1039/a903587g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Bellina F.; Ciucci D.; Vergamini P.; Rossi R. Regioselective synthesis of natural and unnatural (Z)-3-(1-alkylidene)phthalides and 3-substituted isocoumarins starting from methyl 2-hydroxybenzoates. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 2533. 10.1016/S0040-4020(00)00125-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Yoshikawa T.; Shindo M. Stereoselective synthesis of (E)-2-en-4-ynoic acids with ynolates: catalytic conversion to tetronic acids and 2-pyrones. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 5378. 10.1021/ol902086t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Nolla-Saltiel R.; Robles-Marín E.; Porcel S. Silver(I) and gold(I)-promoted synthesis of alkylidene lactones and 2H-chromenes from salicylic and anthranilic acid derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 4484. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.06.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Barve I. J.; Thikekar T. U.; Sun C.-M. Silver(I)-catalyzed regioselective synthesis of triazole fused-1,5-benzoxazocinones. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2370. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Rawat V. K.; Higashida K.; Sawamura M. Use of imidazole[1,5-α]pyridine-3-ylidene as a platform for metal-imidazole cooperative catalysis: silver-catalyzed cyclization of alkyne-tethered carboxylic acids. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 1631. 10.1002/adsc.202001515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zuccarello G.; Escofet I.; Caniparoli U.; Echavarren A. M. New-generation ligand design for the gold-catalyzed asymmetric activation of alkynes. ChemPluschem 2021, 86, 1283. 10.1002/cplu.202100232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sato M.; Rawat V. K.; Higashida K.; Sawamura M. Gold-zinc cooperative catalysis for seven-exo-dig hydrocarboxylation of internal alkynes. Chem. – Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202301917 10.1002/chem.202301917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Dorel R.; Echavarren A. M. Gold(I)-catalyzed activation of alkynes for the construction of molecular complexity. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9028. 10.1021/cr500691k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lemière G.; Gandon V.; Agenet N.; Goddard J.-P.; Kozak A. D.; Aubert C.; Fensterbank L.; Malacria M. Gold(I)- and gold(III)-catalyzed cycloisomerization of allenynes: a remarkable halide effect. Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 7758. 10.1002/ange.200602189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gaona M. A.; De La Cruz-Martínez F.; Fernández-Baeza J.; Sánchez-Barba L. F.; Alonso-Moreno C.; Rodríguez A. M.; Rodríguez-Diéguez A.; Castro-Osma J. A.; Otero A.; Lara-Sánchez A. Synthesis of helical aluminium catalysts for cyclic carbonate formation. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 4218. 10.1039/C9DT00323A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Castro-Osma J. A.; Alonso-Moreno C.; Lara-Sánchez A.; Otero A.; Fernández-Baeza J.; Sánchez-Barba L. F.; Rodríguez A. M. Catalytic behaviour in the ring-opening polymerisation of organoaluminiums supported by bulky heteroscorpionate ligands. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 12388. 10.1039/C4DT03475A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Otero A.; Lara-Sánchez A.; Fernández-Baeza J.; Alonso-Moreno C.; Castro-Osma J. A.; Márquez-Segovia I.; Sánchez-Barba L. F.; Rodríguez A. M.; Garcia-Martinez J. C. Neutral and cationic aluminum complexes supported by acetamidate and thioacetamidate heteroscorpionate ligands as initiators for ring-opening polymerization of cyclic esters. Organometallics 2011, 30, 1507. 10.1021/om1010676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Otero A.; Fernández-Baeza J.; Lara-Sánchez A.; Alonso-Moreno C.; Márquez-Segovia I.; Sánchez-Barba L. F.; Rodríguez A. M. Ring-opening polymerization of cyclic esters by an enantiopure heteroscorpionate rare earth initiator. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2176. 10.1002/anie.200806202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Otero A.; Lara-Sánchez A.; Fernández-Baeza J.; Martínez-Caballero E.; Márquez-Segovia I.; Alonso-Moreno C.; Sánchez-Barba L. F.; Rodríguez A. M.; López -Solera I. New achiral and chiral NNE heteroscorpionate ligands. Synthesis of homoleptic lithium complexes as well as halide and alkyl scandium and yttrium complexes. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 930. 10.1039/B914966J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr R. G.; Pearson R. G. Absolute hardness: Companion parameter to absolute electronegativity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 7512. 10.1021/ja00364a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otero A.; Fernández-Baeza J.; Sánchez-Barba L. F.; Tejeda J.; Honrado M.; Garcés A.; Lara-Sánchez A.; Rodríguez A. M.; Chiral N N. Chiral N , N , O -Scorpionate Zinc Alkyls as Effective and Stereoselective Initiators for the Living ROP of Lactides. Organometallics 2012, 31, 4191. 10.1021/om300146n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen F. H.; Kennard O.; Watson D. G.; Brammer L.; Orpen A. G.; Taylor R. Tables of bond lengths determined by X-ray and neutron diffraction. Part 1. Bond lengths in organic compounds. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1987, 12, S1. 10.1039/p298700000s1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eliel E. L.; Wilen S. H.. Stereochemistry of organic compounds; Wiley, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby A. J. Effective molarities for intramolecular reactions. Adv. Phys. Org. Chem. 1980, 17, 183. 10.1016/S0065-3160(08)60129-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartak H.; Weibel J.-M.; Pale P. A mild access to γ- or δ-alkylidene lactones through gold catalysis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 6273. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.06.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.