Abstract

Background

In microvascular head and neck reconstruction, ischemia of the free flap tissue is inevitable during microsurgical anastomosis and may affect microvascular free flap perfusion, which is a prerequisite for flap viability and a parameter commonly used for flap monitoring. The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of the number of ischemia intervals and ischemia duration on flap perfusion.

Methods

Intraoperative and postoperative flap blood flow, hemoglobin concentration, and hemoglobin oxygen saturation at 2 and 8 mm tissue depths, as measured with the O2C tissue oxygen analysis system, were retrospectively analyzed for 330 patients who underwent microvascular head and neck reconstruction between 2011 and 2020. Perfusion values were compared between patients without (control patients) and with a second ischemia interval (early or late) and examined with regard to ischemia duration.

Results

Intraoperative and postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth were lower in patients with early second ischemia intervals than in control patients [102.0 arbitrary units (AU) vs 122.0 AU, P = .030; 107.0 AU vs 128.0 AU, P = .023]. Both differences persisted in multivariable analysis. Intraoperative and postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth correlated weakly negatively with ischemia duration in control patients (r = −.145, P = .020; r = −.124, P = .048). Both associations did not persist in multivariable analysis.

Conclusions

The observed decrease in microvascular flap blood flow after early second ischemia intervals may reflect ischemia-related vascular flap tissue damage and should be considered as a confounding variable in flap perfusion monitoring.

Keywords: free tissue flap, microsurgery, perfusion, ischemia, blood flow, oxygen saturation

Graphical abstract.

Introduction

Free tissue transfer with microvascular free flaps is a standard procedure for the reconstruction of complex head and neck defects providing both superior outcomes and high overall success rates.1-3 However, the process of free tissue transfer with microvascular free flaps involves an obligatory period of flap tissue ischemia due to the need for flap transfer and flap pedicle anastomosis on the recipient side.4-6

Flap tissue ischemia, defined as a state of inadequate blood supply to the flap tissue, is associated with hypoxia-related flap tissue changes such as vasoconstriction and capillary narrowing.5-7 The extent of these flap tissue changes depends on the duration of ischemia, and subsequent reperfusion after the completion of the anastomosis may result in either a flap tissue recovery with restoration of flap blood flow or an inflammatory-related ischemia/reperfusion injury without restoration of flap blood flow due to vascular thrombosis.5-10 An additional ischemia interval after the interruption of the initial reperfusion results in further injury to the flap tissue due to extended vascular thrombosis.5,10,11 This could be due to the surgeon temporarily releasing the vessel clamp on the arterial recipient vessel after arterial/before venous anastomosis to verify the patency of the arterial anastomosis by assessing venous outflow, which is discouraged by other surgeons to avoid an additional ischemia interval in view of further injury to the flap tissue, or the need for anastomosis revision with additional temporary clamping of the arterial recipient vessel after release of flap perfusion.5,10,11 Interestingly, some studies have found that a higher number of ischemia intervals and a longer duration of ischemia are associated with greater free flap tissue damage,4,8,11,12

Considering that decreased flap perfusion has been associated with flap failure, the reduction of microvascular free flap perfusion due to tissue damage resulting from a higher number of ischemia intervals and a longer duration of ischemia could contribute to higher flap failure.10,13-16 Furthermore, flap perfusion is used as a parameter for flap perfusion monitoring, and higher number of ischemia intervals and a longer duration of ischemia could be potential confounding variables.13-15 However, the influences of the number of ischemia intervals and the duration of ischemia on microvascular free flap perfusion have not been previously clarified.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the influences of the number of ischemia intervals and the duration of ischemia on microvascular free flap perfusion.

Methods

Study Population

The local ethics committee of the Medical Faculty RWTH Aachen University (EK 309—20) approved this retrospective study based on data collected for routine clinical purposes.

The study population consisted of 330 patients who underwent reconstruction with microvascular free flaps with a skin component in the head and neck region after malignant or nonmalignant diseases in our Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery between 2011 and 2020. The flap types used were radial free forearm flaps (RFFF), anterolateral thigh flaps (ALTF), or fibula free flaps (FFF). The patient exclusion criteria were incomplete data records and age under 18 years.

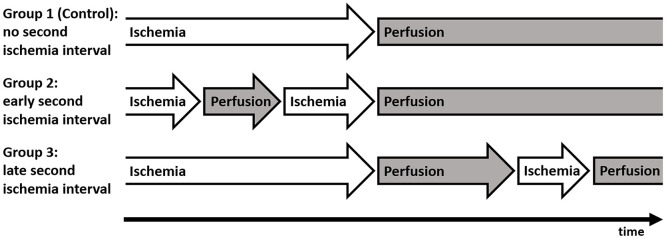

The number of ischemia intervals (ie, the presence of a second ischemia interval) was assessed by the number of flap reperfusion interruptions during the anastomosis procedure (Figure 1). Cases in which the vessel clamp on the arterial recipient vessel was not temporarily released after arterial/before venous anastomosis to verify the patency of the arterial anastomosis by assessing venous outflow, and no intraoperative anastomosis revision was performed with additional temporary clamping of the arterial recipient vessel after release of flap perfusion, were grouped as control patients without a second ischemia interval. Cases in which the vessel clamp on the arterial recipient vessel was temporarily released after arterial/before venous anastomosis to verify the patency of the arterial anastomosis by assessing venous outflow, but no intraoperative anastomosis revision was performed with additional temporary clamping of the arterial recipient vessel after release of flap perfusion, were grouped as patients with an early second ischemia interval. Cases in which the vessel clamp on the arterial recipient vessel was not temporarily released after arterial/before venous anastomosis to verify the patency of the arterial anastomosis by assessing venous outflow, but an intraoperative anastomosis revision was performed with additional temporary clamping of the arterial recipient vessel after release of flap perfusion, were grouped as patients with a late second ischemia interval. Cases with both temporary release of the arterial recipient vessel clamp during the anastomosis procedure and intraoperative anastomosis revision with additional temporary clamping of the arterial recipient vessel after release of flap perfusion were excluded. The duration of the ischemia interval was defined as the total time of absent flap perfusion.

Figure 1.

Study groups.

Patients were categorized into groups according to the presence of a second ischemia interval. Group 1 (Control): patients without a second ischemia interval; group 2: patients with an early second ischemia interval (cases in which the vessel clamp on the arterial recipient vessel was temporarily released after arterial/before venous anastomosis to verify the patency of the arterial anastomosis by assessing venous outflow); group 3: patients with a late second ischemia interval (cases in which intraoperative anastomosis revision was performed with additional temporary clamping of the arterial recipient vessel after release of flap perfusion).

Comorbidities were defined as per discipline-specific guidelines, and smoking status was defined as actual or past daily smoking for a period of at least 6 months. 17 A patient’s prior neck dissection or irradiation status was designated as positive if the patient had undergone anatomic dissection of the recipient vessel in the setting of neck dissection or irradiation to the recipient vessel area in the setting of neck irradiation. The duration of surgery was defined as the time between the first incision and the last suture. Flap revision was designated as positive if the patient had surgical revision of the anastomosis with return to the operating room, and flap success was designated as negative if the patient had the flap removed owing to flap necrosis.

All operations were conducted under general anesthesia. Arterial anastomoses were performed in an end-to-end fashion and venous anastomoses were performed in an end-to-side or end-to-end fashion. At least until the next morning, patients remained in the intensive care unit postoperatively with invasive mechanical ventilation, analgosedation, invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, and blood pressure regulation by central venous norepinephrine administration as needed (target systolic pressure above 125 mmHg).

Flap Perfusion Measurement Data

Flap perfusion data were based on measurements with the O2C tissue oxygen analysis system (O2C Oxygen-to-see; LEA Medizintechnik) described in previous studies.13,15,18 The measurement of flap blood flow [arbitrary units (AU)] was based on laser Doppler spectroscopy (830 nm; 30 mW), and flap blood flow was calculated by analyzing the Doppler shift of laser light due to the movement of erythrocytes in the blood vessels as the product of erythrocyte quantity and velocity.13,19 The measurement of hemoglobin concentration (AU) and that of hemoglobin oxygen saturation (%) were based on white light spectroscopy (500-800 nm; 50 W), and hemoglobin concentration was calculated by analyzing the sum of light absorption and hemoglobin oxygen saturation was calculated by analyzing the change in light color compared to spectra with known oxygen saturation.13,19 Measurements were performed for 10 seconds (with a lead time of 4 seconds) with ambient light compensation control at 2 and 8 mm tissue depths, which represent different tissue layers and their vasculature of the skin and have been shown to be of interest for postoperative monitoring of microvascular free flaps with the O2C tissue analysis system.13,15 The measurements were performed intraoperatively (after the release of the anastomosis in the operating room) and postoperatively (on the first postoperative morning in the intensive care unit), with the probe placed centrally on the dried skin portion of the flap in a sterile sheath.

Statistical Analysis

The patients were divided into groups according to the presence of a second ischemia interval, that is, control patients without a second ischemia interval and patients with a second ischemia interval (these patients were further subdivided into patients with an early second ischemia interval and patients with a late second ischemia interval). Patients were also divided into 2 groups according to their American Society of Anesthesiologists score (ASA; ASA >2 or ASA ≤2). Group differences in clinical parameters were analyzed using the chi-squared test, Fisher exact test, or Freeman Halton test for categorical data and the Mann-Whitney test for metric data. Group differences in perfusion measures were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test and using multiple linear regression models if significant differences existed between groups, adjusting for ischemia duration, flap type, mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg), and administered catecholamine dose (µg/minute per kg). Correlations between perfusion measures and ischemia duration were analyzed using the Spearman correlation coefficient and using multiple linear regressions models if significant correlations were present, adjusting for flap type, mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg), and administered catecholamine dose (µg/minute per kg) separately for each group. Values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 28 (SPSS; IBM).

Results

Patient Characteristics

The study population consisted of 330 patients [254 control patients without a second ischemia interval and 76 patients with a second ischemia interval (55 patients with an early second ischemia interval and 21 patients with a late second ischemia interval); Table 1]. The groups of control patients and patients with a second ischemia interval did not differ in terms of their clinical characteristics (all P > .05). In addition, the groups of control patients and patients with an early second ischemia interval did not differ in terms of their clinical characteristics (all P > .05). The groups of control patients and patients with a late second ischemia interval did only differ in terms of the arterial anastomosis recipient vessel and duration of surgery (P < .001 and P = .001).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Outcomes.

| Variable | Control (n = 254) | SI (n = 76) | Early SI (n = 55) | Late SI (n = 21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n) | ||||

| Male | 132 (52.0%) | 36 (47.4%) | 29 (52.7%) | 7 (33.3%) |

| Female | 122 (48.0%) | 40 (52.6%) | 26 (47.3%) | 14 (66.7%) |

| Age (y) | 64.0 (16.0) | 62.5 (19.0) | 61.0 (20.0) | 65.0 (15.0) |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 24.2 (6.0) | 24.6 (6.4) | 24.8 (7.8) | 24.3 (6.5) |

| ASA (n) | ||||

| 1 + 2 | 137 (53.9%) | 36 (47.4%) | 26 (47.3%) | 10 (47.6%) |

| 3 + 4 | 117 (46.1%) | 40 (52.6%) | 29 (52.7%) | 11 (52.4%) |

| Flap type (n) | ||||

| RFFF | 127 (50.0%) | 29 (38.2%) | 23 (41.8%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| ALTF | 93 (36.6%) | 38 (50.0%) | 28 (50.9%) | 10 (47.6%) |

| FFF | 34 (13.4%) | 9 (11.8%) | 4 (7.3%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| Flap location (n) | ||||

| Tongue | 37 (14.6%) | 8 (10.5%) | 8 (14.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Floor of mouth | 52 (20.5%) | 18 (23.7%) | 13 (23.6%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| Mandible | 71 (28.0%) | 18 (23.7%) | 10 (18.2%) | 8 (38.1%) |

| Maxilla + hard palate | 26 (10.2%) | 14 (18.4%) | 10 (18.2%) | 4 (19.0%) |

| Cheek | 19 (7.5%) | 6 (7.9%) | 5 (9.1%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Soft palate | 12 (4.7%) | 3 (3.9%) | 2 (3.6%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Extraoral | 37 (14.6%) | 9 (11.8%) | 7 (12.7%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Arterial anastomosis recipient vessel (n)*** | ||||

| ECA | 13 (5.1%) | 9 (11.8%) | 4 (7.3%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| FAA | 104 (40.9%) | 29 (38.2%) | 21 (38.2%) | 8 (38.1%) |

| LIA | 14 (5.5%) | 6 (7.9%) | 2 (3.6%) | 4 (19.0%) |

| STA | 123 (48.4%) | 32 (42.1%) | 28 (50.9%) | 4 (19.0%) |

| Surgery duration (min)*** | 545.0 (154.0) | 555.5 (149.0) | 540.0 (123.0) | 643.0 (216.0) |

| Flap ischemia duration (min) | 106.5 (34.0) | 103.5 (38.0) | 103.0 (36.0) | 110.0 (38.0) |

| Diabetes (n) | ||||

| No | 213 (83.9%) | 69 (90.8%) | 50 (90.9%) | 19 (90.5%) |

| Yes | 41 (16.1%) | 7 (9.2%) | 5 (9.1%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Arterial hypertension (n) | ||||

| No | 161 (63.4%) | 53 (69.7%) | 40 (72.7%) | 13 (61.9%) |

| Yes | 93 (36.6%) | 23 (30.3%) | 15 (27.3%) | 8 (38.1%) |

| Smoking status (n) | ||||

| No | 153 (60.2%) | 49 (64.5%) | 34 (61.8%) | 15 (71.4%) |

| Yes | 101 (39.8%) | 27 (35.5%) | 21 (38.2%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| Prior neck dissection (n) | ||||

| No | 204 (80.3%) | 59 (77.6%) | 44 (80.0%) | 15 (71.4%) |

| Yes | 50 (19.7%) | 17 (22.4%) | 11 (20.0%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| Prior neck irradiation (n) | ||||

| No | 222 (87.4%) | 66 (86.8%) | 50 (90.9%) | 16 (76.2%) |

| Yes | 32 (12.6%) | 10 (13.2%) | 5 (9.1%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| Flap survival (n) | ||||

| No | 4 (1.6%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Yes | 250 (98.4%) | 75 (98.7%) | 54 (98.2%) | 21 (100.0%) |

| Flap revision (n) | ||||

| No | 239 (94.1%) | 75 (98.7%) | 54 (98.2%) | 21 (100.0%) |

| Yes | 15 (5.9%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Parameters are indicated as numbers (with percentage) for categorical data (sex, ASA, flap type, flap location, arterial anastomosis recipient vessel, diabetes, arterial hypertension, smoking status, prior neck dissection, prior neck irradiation, flap survival, flap revision) or median (with interquartile range) for metric data (age, BMI, surgery duration, flap ischemia duration); separately described for patients without a second ischemia interval (Control), patients with a second ischemia interval (SI); subdivided into patients with an early second ischemia interval (early SI) and patients with a late second ischemia interval (late SI); P values corresponding to testing for differences between groups (SI, early SI, and late SI vs Control) with chi-squared test (sex, ASA, flap type, arterial hypertension, smoking status, prior neck dissection), Fisher’s exact test (diabetes, prior neck irradiation, flap survival, flap revision), and Freeman Halton test (flap location, arterial anastomosis recipient vessel) for categorical data and Mann-Whitney test (age, BMI, surgery duration, flap ischemia duration) for metric data.

Abbreviations: ALTF, anterolateral thigh flap; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists score; BMI, body mass index; ECA, external carotid artery; FAA, facial artery; FFF, fibula free flap; LIA, lingual artery; RFFF, radial free forearm flap; STA, superior thyroid artery.

P < .05 SI versus Control. **P < .05 early SI versus Control. ***P < .05 late SI versus Control.

Patient Outcomes

The groups of control patients and patients with a second ischemia interval did not differ in terms of their clinical outcomes (all P > .05; Table 1). In addition, the groups of control patients and patients with an early second ischemia interval did not differ in terms of their clinical outcomes (all P > .05), for example, flap success (flap failure in patients with an early second ischemia interval: 1 ALTF; flap failure in control patients: 1 RFFF, 1 ALTF, and 2 FFFs; P = 1.000) and flap revision (flap revisions in patients with an early second ischemia interval: 1 ALTF; flap revisions in control patients: 8 RFFFs, 2 ALTFs, and 5 FFFs; P = .321; Table 1). In addition, the groups of control patients and patients with a late second ischemia interval did not differ in terms of their clinical outcomes (no flap failure in patients with a late second ischemia interval; flap failure in control patients: 1 RFFF, 1 ALTF, and 2 FFFs; P = 1.000) and flap revision (no flap revision in patients with a late second ischemia interval; flap revisions in control patients: 8 RFFFs, 2 ALTFs, and 5 FFFs; P = .614; Table 1).

Comparison of Flap Perfusion Parameters Between Number of Ischemia Intervals

The postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm of tissue depth was lower in the patients with a second ischemia interval than in control patients (108.5 AU vs 128.0 AU, P = .038; Table 2 and Figure 2). The difference persisted in the multivariable testing (P = .043). In the multivariable testing, mean arterial blood pressure was a control variable with significant effect on postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth (P = .034; higher values were associated with higher flap blood flow). No other differences that persisted in the multivariable testing were found between the 2 groups with regard to flap perfusion parameters (ie, flap blood flow, hemoglobin concentration, and hemoglobin oxygen saturation; all P > .05).

Table 2.

Flap Perfusion Parameter Comparison Between Number of Ischemia Intervals.

| Variable | Control | SI | Early SI | Late SI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 254) | (n = 76) | P value | (n = 55) | P value | (n = 21) | P value | |

| Intraoperative measurement | |||||||

| 8 mm tissue depth | |||||||

| FLOW (AU) | 122.0 (81.3) | 101.0 (58.5) | .032 | 102.0 (53.0) | .030 * | 97.0 (69.5) | .460 |

| HB (AU) | 39.0 (19.0) | 38.0 (16.0) | .690 | 36.0 (18.0) | .535 | 39.0 (12.0) | .814 |

| SO2 (%) | 68.0 (31.3) | 69.0 (34.0) | .816 | 69.0 (36.0) | .554 | 70.0 (33.5) | .596 |

| 2 mm tissue depth | |||||||

| FLOW (AU) | 24.0 (28.0) | 23.0 (23.8) | .086 | 23.0 (22.0) | .094 | 23.0 (34.5) | .482 |

| HB (AU) | 68.0 (23.3) | 63.5 (27.5) | .140 | 63.0 (28.0) | .109 | 68.0 (26.5) | .745 |

| SO2 (%) | 73.0 (34.0) | 68.0 (38.5) | .460 | 67.0 (37.0) | .556 | 73.0 (43.5) | .597 |

| Postoperative measurement | |||||||

| 8 mm tissue depth | |||||||

| FLOW (AU) | 128.0 (78.5) | 108.5 (64.5) | .038 * | 107.0 (56.0) | .023 * | 118.0 (95.5) | .676 |

| HB (AU) | 37.0 (14.0) | 33.0 (15.5) | .031 | 32.0 (15.0) | .012 | 37.0 (17.5) | .859 |

| SO2 (%) | 60.0 (34.0) | 65.0 (31.5) | .752 | 63.0 (31.0) | .751 | 71.0 (35.0) | .229 |

| 2 mm tissue depth | |||||||

| FLOW (AU) | 31.0 (36.0) | 28.0 (31.3) | .465 | 26.0 (25.0) | .154 | 35.0 (44.5) | .356 |

| HB (AU) | 59.5 (27.3) | 52.5 (23.0) | .013 | 50.0 (26.0) | .002 * | 58.0 (17.5) | .974 |

| SO2 (%) | 63.0 (35.0) | 61.5 (33.5) | .508 | 60.0 (34.0) | .270 | 65.0 (40.0) | .609 |

Parameters are indicated as median (with interquartile range) for intraoperative and postoperative measurement [separately described for patients without a second ischemia interval (Control) and patients with a second ischemia interval (SI); subdivided into patients with an early second ischemia interval (early SI) and patients with a late second ischemia interval (late SI); P values corresponding to testing for differences between groups (SI, early SI, and late SI vs Control) with Mann-Whitney test; significant P values are bold [*P < .05 on adjustment for ischemia duration, flap type, mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg) and administered catecholamine dose (µg/minute per kg) in multiple regression analysis].

Abbreviations: AU, arbitrary units; FLOW, blood flow; HB, hemoglobin concentration; SO2, hemoglobin oxygen saturation.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative blood flow.

Box plot for intraoperative blood flow [AU; separately shown for 8 mm tissue depth (left) and 2 mm tissue depth (right)] for patients without a second ischemia interval (Control) and patients with a second ischemia interval (SI); subdivided into patients with an early second ischemia interval (early SI) and patients with a late second ischemia interval (late SI); P values corresponding to testing for differences between groups (SI, early SI, and late SI vs Control) with Mann-Whitney test; significant P values are bold [*P < .05 on adjustment for ischemia duration, flap type, mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg), and administered catecholamine dose (µg/minute per kg) in multiple regression analysis]. Abbreviation: AU, arbitrary units.

The intraoperative and postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm of tissue depth were lower in the patients with an early second ischemia interval than in control patients (102.0 AU vs 122.0 AU, P = .030; and 107.0 AU vs 128.0 AU, P = .023, respectively; Table 2 and Figures 2 and 3). These differences persisted in the multivariable testing (P = .044 and P = .017, respectively). In the multivariable testing, mean arterial blood pressure was a control variable with significant effect on postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth (P = .048; higher values were associated with higher flap blood flow). Furthermore, the postoperative hemoglobin concentration at 2 mm tissue depth was lower in the patients with an early second ischemia interval than in control patients (50.0 AU vs 59.5 AU, P = .002; Table 2). The difference persisted in the multivariable testing (P = .008). In the multivariable testing, flap type was a control variable with significant effect on postoperative hemoglobin concentration (P < .001, RFFF and FFF were associated with higher hemoglobin concentration). No other differences that persisted in multivariable testing were found between the 2 groups with regard to flap perfusion parameters (all P > .05).

Figure 3.

Postoperative blood flow.

Box plot for postoperative blood flow [AU; separately shown for 8 mm tissue depth (left) and 2 mm tissue depth (right)] for patients without a second ischemia interval (Control) and patients with a second ischemia interval (SI); subdivided into patients with an early second ischemia interval (early SI) and patients with a late second ischemia interval (late SI); P values corresponding to testing for differences between groups (SI, early SI, and late SI vs Control) with Mann-Whitney test; significant P values are bold [*P < .05 on adjustment for ischemia duration, flap type, mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg) and administered catecholamine dose (µg/minute per kg) in multiple regression analysis]. Abbreviation: AU, arbitrary units.

No differences in flap perfusion parameters were found between patients with a late second ischemia interval and control patients (all P > .05).

Correlation of Flap Perfusion Parameters With Ischemia Duration

The intraoperative and postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth was negatively correlated with ischemia duration in patients without a second ischemia interval (r = −.145, P = .020; r = −.124, P = .048; Table 3). These associations did not persist in the multivariable testing (P = .092 and P = .344). In the multivariable testing, mean arterial blood pressure was a control variable with significant effect on postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth (P = .020; higher values were associated with higher flap blood flow).

Table 3.

Flap Perfusion Parameter Correlation With Flap Ischemia Duration.

| Variable | Control (n = 254) | SI (n = 76) | Early SI (n = 55) | Late SI (n = 21) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | |

| Intraoperative measurement | ||||||||

| 8 mm tissue depth | ||||||||

| FLOW (AU) | −.145 | .020* | .001 | .995 | −.033 | .811 | .142 | .540 |

| HB (AU) | .106 | .091 | −.138 | .234 | −.054 | .693 | −.342 | .129 |

| SO2 (%) | −.030 | .631 | .017 | .885 | .022 | .876 | −.021 | .929 |

| 2 mm tissue depth | ||||||||

| FLOW (AU) | −.074 | .243 | −.034 | .770 | −.024 | .864 | −.035 | .880 |

| HB (AU) | .023 | .712 | −.072 | .534 | −.119 | .386 | −.031 | .894 |

| SO2 (%) | −.010 | .874 | .240 | .037 * | .296 | .028 * | .098 | .672 |

| Postoperative measurement | ||||||||

| 8 mm tissue depth | ||||||||

| FLOW (AU) | −.124 | .048 * | .067 | .565 | .112 | .417 | −.040 | .865 |

| HB (AU) | .055 | .385 | −.039 | .737 | −.039 | .779 | −.089 | .701 |

| SO2 (%) | −.047 | .459 | .044 | .706 | .021 | .882 | .113 | .627 |

| 2 mm tissue depth | ||||||||

| FLOW (AU) | −.084 | .180 | −.018 | .881 | −.007 | .960 | −.062 | .788 |

| HB (AU) | .036 | .563 | −.012 | .915 | −.081 | .556 | .058 | .804 |

| SO2 (%) | .011 | .863 | .262 | .022 * | .254 | .062 | .276 | .225 |

Parameters are indicated as Spearman correlation coefficient [r; separately described for patients without a second ischemia interval (Control) and patients with a second ischemia interval (SI); subdivided into patients with an early second ischemia interval (early SI) and patients with a late second ischemia interval (late SI); P values corresponding to calculation of Spearman correlation coefficient; significant P values are bold [*P > .05 on adjustment flap type, mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg), and administered catecholamine dose (µg/minute per kg) in multiple regression analysis].

Abbreviations: AU, arbitrary units; FLOW, blood flow; HB, hemoglobin concentration; SO2, hemoglobin oxygen saturation.

Additional correlations that were observed between the flap perfusion parameters and the ischemia duration did also not persist in multivariable testing (Table 3).

Discussion

This study investigated the influences of the number of ischemia intervals and the duration of ischemia on microvascular free flap perfusion in the head and neck region, as flap tissue ischemia is an obligatory component of microvascular free tissue transfer due to the need for flap relocation and anastomosis.4-6 Although flap perfusion is critical for flap viability and survival and is used as a parameter for flap monitoring, it remains unknown whether the number of ischemia intervals and the duration of ischemia influence microvascular free flap perfusion.13-15,19-21 Such information may improve the understanding of microvascular free flap perfusion in general, provide potential guidance for controlling the number of ischemia intervals and the ischemia duration, and support the accurate interpretation of flap perfusion measurements in the context of flap monitoring.

In this study, patients with a second ischemia interval were further subdivided into patients with an early second ischemia interval (cases in which the vessel clamp on the arterial recipient vessel was temporarily and shortly released after arterial/before venous anastomosis to verify the patency of the arterial anastomosis by assessing venous outflow) or a late second ischemia interval (cases in which intraoperative anastomosis revision was performed with additional temporary clamping of the arterial recipient vessel after prolonged release of flap perfusion) to account for the influence of the time between the first and second ischemia intervals on the extent of ischemia-related vascular flap tissue changes.22,23 This study did not investigate the influences of the number of ischemia intervals and ischemia duration on flap survival nor determined flap perfusion cutoff values to predict flap survival, since previous studies have already addressed both topics and furthermore multiple potential confounding variables related to flap success were not covered by the data set of this study.12,13,15,24,25

This study showed that microvascular free flap perfusion, in terms of flap blood flow, was affected by the number of ischemia intervals, as intraoperative and postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth were lower in patients with a second ischemia interval than in control patients without a second ischemia interval. This may be attributed to vascular flap tissue injuries in the form of thrombotic vessel occlusions associated with a second ischemia interval.5,10,11 However, these differences compared with control patients without a second ischemia interval were observed only in patients with an early second ischemia interval and not in patients with a late second ischemia interval, which is consistent with the observation that a short time interval of between the first and the second ischemia interval and, consequently, a shorter period of reperfusion between both actually increases the extent of ischemia-related vascular flap tissue changes.22,23 In this context, the higher vulnerability of the flap to an early second ischemia interval may be due to less advanced recovery of the flap tissue from ischemia-related vascular tissue changes induced by reperfusion after the first ischemia interval.5,6,10 Interestingly, the intraoperative and postoperative hemoglobin oxygen saturation values at 8 mm tissue depth did not differ between both groups. This was unexpected in view of the dependence of hemoglobin oxygen saturation on blood flow in free flap perfusion and the lower flap blood flow in patients with an early second ischemia interval.13,26 Methodically, the measured hemoglobin oxygen saturation primarily reflects the oxygen saturation of hemoglobin in the capillary venous vasculature after oxygen extraction from the blood. 15 Therefore, similar hemoglobin oxygen saturations might reflect lower oxygen extraction by the flap tissue in patients with an early second ischemia interval, possibly due to an ischemia-related partial shutdown of the microcirculation. 5 With regard to a possible confounding effect of the ischemia duration, because the extent of ischemia-related flap tissue changes is related to ischemia duration, and the flap type, because ischemia susceptibility is related to the tissue metabolic rate and, thus, a higher ischemia susceptibility of the ALT with its high amount of muscle tissue can be presumed, it should be taken into account that the groups of patients with an early second ischemia interval and control patients without a second ischemia interval did not differ in terms of ischemia duration and flap type and that the differences in intraoperative and postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth between both groups persisted on adjustment for ischemia duration and flap type as well as for presumed factors affecting flap perfusion (ie, mean arterial blood pressure and catecholamine dose administered).5,6,8,27

Interestingly, the excluded patients who had both temporary release of the arterial recipient vessel clamp during the anastomosis procedure, that is, an early ischemia interval, and intraoperative anastomosis revision with additional temporary clamping of the arterial recipient vessel after release of flap perfusion, that is, a late ischemia interval, showed the absolute lowest postoperative blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth [9.5 AU (Mann-Whitney test P = .047 vs control patients)].

This study also showed that microvascular free flap perfusion was not affected by the duration of ischemia. The only association between flap perfusion and duration of ischemia in the form of a weak negative correlation between intraoperative and postoperative flap blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth and ischemia duration in control patients without a second ischemia interval in univariable analysis did not persist in the multivariable analysis with adjustment for the flap type as well as for presumed factors affecting flap perfusion (ie, mean arterial blood pressure and catecholamine dose administered). 27 The lack of associations between flap perfusion and duration of ischemia seems unexpected given the ischemia-related vascular flap tissue changes. 5 However, this may reflect that subsequent reperfusion after ischemia resulted in tissue recovery with restoration of flap blood flow; and it may be explained by the fact that the maximum ischemia duration of the patients included in this study was 3 hours, which was shown to be well tolerated by free flaps.4-6,10

Interestingly, in some of the multivariable testing, control variables with a significant effect on flap perfusion values were mean arterial blood pressure and flap type, which is consistent with differences in perfusion values between different flap types observed in previous studies and may reflect an influence of mean arterial blood pressure on flap perfusion.13,15,27

This study has limitations, such as the lack of preoperative reference values for flap perfusion before flap harvest. Further limitations arise from the measurement method; a moist environment may complicate the measurement procedure, and differences in skin temperature between patients affecting skin perfusion cannot be excluded, both of which may hamper patient comparisons.28,29 However, the flaps were cleaned and dried before every measurement. Nevertheless, as a limitation of the study, differences in skin temperature between patients with possible influence on perfusion measurements cannot be excluded. In addition, it cannot be excluded that patients differed in terms of vascular anatomy of the cervical vasculature (eg, vessel diameter) and flap anatomy (eg, flap size and pedicle length, both of which may influence flap perfusion). Furthermore, possible confounding variables such as volume substitution were not considered. Another limitation is that the time interval between the final release of the anastomosis and the postoperative perfusion measurement was not standardized due to differences in the extent of surgery, which might affect comparability between patients. However, the time interval between the intraoperative and postoperative perfusion measurement did not differ between groups (control patients median 713.5 minutes), patients with SI median 680.0 minutes (Mann-Whitney test vs control patients P = .309), patients with early SI median 704.0 minutes (Mann-Whitney test vs control patients P = .827), patients with late SI median 654.0 minutes (Mann-Whitney test vs control patients P = .081). In general, although of interest, changes in flap perfusion beyond the short period studied here cannot be excluded, as the data are not available, and time between the first and second ischemia intervals were quite short compared with other studies.11,20,30

This study sheds light on microvascular free flap perfusion and demonstrates that an early second ischemia interval leads to decreased intraoperative and postoperative flap blood flow, which might reflect ischemia-related flap tissue damages.5,10,11 Indeed, among several factors (in addition to adequate flap perfusion) that are critical for flap survival, decreased flap perfusion has been linked to flap failure.13-16 Interestingly, in this study, failed flaps showed lower intraoperative blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth and tended to have a lower postoperative blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth compared to not failed flaps (intraoperative blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth 50.0 AU vs 117.0 AU, Mann-Whitney test P = .011; postoperative blood flow at 8 mm tissue depth 47.0 AU vs 125.0 AU, Mann-Whitney test P = .153). However, flap failure rates were indifferent between all groups categorized by the presence of a second ischemia interval in this study, which may be related to the setting of the second ischemia interval caused by arterial occlusion in all cases, which has been shown to have less impact on flap survival than a second ischemia interval caused by venous occlusion. 23

Since flap perfusion is used as a parameter for postoperative flap monitoring to early detect flap failure, with lower blood flow indicating vascular compromise, early second ischemia intervals should be considered as confounding variables, with lower flap blood flow values possibly due to second ischemia intervals rather than vascular compromise.13-15

In terms of clinical implications, this study argues for ensuring a longer reperfusion time after the first ischemia interval in cases with intended intraoperative anastomosis revision and for accounting for early second ischemia intervals in flap monitoring based on flap perfusion measurement.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that the timing of a second ischemia interval has an impact on microvascular free flap perfusion rather than the number of ischemia intervals or the duration of ischemia, as intraoperative and postoperative flap blood values were lower in patients with an early second ischemia interval than in control patients without a second ischemia interval. This may reflect ischemia-related vascular flap tissue damages. Early second ischemia intervals should be accounted for in flap perfusion monitoring.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: M.O. contributed to the study concept, study design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation, and manuscript editing; P.W. contributed to the study design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis and manuscript reviewing; M.H. contributed to the study design, quality control of data and algorithms, data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis, and manuscript reviewing; F.P. contributed to the study design, quality control of data and algorithms, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript reviewing; M.S.K. contributed to the study concept, study design, quality control of data and algorithms, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript reviewing; J.B. and F.H. contributed to the study concept, study design, quality control of data and algorithms, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript reviewing; A.M. contributed to the study concept, study design, quality control of data and algorithms, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript editing, and manuscript reviewing.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used during the current study are under further analysis and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for Publication: This article does not contain any individual person’s data in any form.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Study design and methodology were reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of RWTH Aachen University (EK 309—20). The local ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of RWTH Aachen University allowed us to waive informed consent for this human study. All methods were in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

References

- 1. Pattani KM, Byrne P, Boahene K, Richmon J. What makes a good flap go bad? A critical analysis of the literature of intraoperative factors related to free flap failure. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:717-723. doi: 10.1002/lary.20825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wong CH, Wei FC. Microsurgical free flap in head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck. 2010;32:1236-1245. doi: 10.1002/hed.21284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang KY, Lin YS, Chen LW, Yang KC, Huang WC, Liu WC. Risk of free flap failure in head and neck reconstruction: analysis of 21,548 cases from a nationwide database. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;84:S3-S6. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kerrigan CL, Zelt RG, Daniel RK. Secondary critical ischemia time of experimental skin flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:522-526. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198410000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carroll WR, Esclamado RM. Ischemia/reperfusion injury in microvascular surgery. Head Neck. 2000;22:700-713. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siemionow M, Arslan E. Ischemia/reperfusion injury: a review in relation to free tissue transfers. Microsurgery. 2004;24:468-475. doi: 10.1002/micr.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stotland MA, Kerrigan CL. The role of platelet-activating factor in musculocutaneous flap reperfusion injury. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1989-1999; discussion 2000-2001. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199706000-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morris SF, Pang CY, Zhong A, Boyd B, Forrest CR. Assessment of ischemia-induced reperfusion injury in the pig latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1162-1172. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199311000-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cha S, Schusterman MA, Cromeens DM. Thrombosis in an ischemia-reperfusion injury flap model: is vessel anastomosis a factor? J Reconstr Microsurg. 1996;12:27-29. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quinlan J. Anaesthesia for reconstructive surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care Med. 2006;7:31-35. doi: 10.1383/anes.2006.7.1.31 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Angel MF, Knight KR, Amiss LR, Morgan RF. Further investigation of secondary venous obstruction. Microsurgery. 1992;13:255-257. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920130512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ehrl D, Heidekrueger PI, Ninkovic M, Broer PN. Impact of duration of perioperative ischemia on outcomes of microsurgical reconstructions. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2018;34:321-326. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1621729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hölzle F, Loeffelbein DJ, Nolte D, Wolff KD. Free flap monitoring using simultaneous non-invasive laser Doppler flowmetry and tissue spectrophotometry. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2006;34:25-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2005.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abdel-Galil K, Mitchell D. Postoperative monitoring of microsurgical free tissue transfers for head and neck reconstruction: a systematic review of current techniques—part I. Non-invasive techniques. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:351-355. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hölzle F, Rau A, Loeffelbein DJ, Mücke T, Kesting MR, Wolff KD. Results of monitoring fasciocutaneous, myocutaneous, osteocutaneous and perforator flaps: 4-year experience with 166 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:21-28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sogorski A, Dostibegian M, Lehnhardt M, et al. Postoperative Remote Ischemic Conditioning (RIC) significantly improves entire flap microcirculation beyond 4 hours. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022;75:4003-4012. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2022.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Latza U, Hoffmann W, Terschüren C, et al. Rauchen als möglicher Confounder in epidemiologischen studien: standardisierung der erhebung, quantifizierung und analyse. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67:795-802. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mücke T, Rau A, Merezas A, et al. Changes of perfusion of microvascular free flaps in the head and neck: a prospective clinical study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52:810-815. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beckert S, Witte MB, Königsrainer A, Coerper S. The impact of the micro-lightguide O2C for the quantification of tissue ischemia in diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2863-2867. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mücke T, Wolff KD, Rau A, Kehl V, Mitchell DA, Steiner T. Autonomization of free flaps in the oral cavity: a prospective clinical study. Microsurgery. 2012;32:201-206. doi: 10.1002/micr.20984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Min SH, Choe SH, Kim WS, Ahn SH, Cho YJ. Effects of ischemic conditioning on head and neck free flap oxygenation: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2022;12:8130. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-12374-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Angel MF, Knight KR, Biavati MJ, et al. Timing relationships for secondary ischemia in rodents: the effect of arteriovenous obstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1991;7:335-337. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hauge EM, Balling E, Hartmund T, Hjortdal VE. Secondary ischemia caused by venous or arterial occlusion shows differential effects on myocutaneous island flap survival and muscle ATP levels. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:825-833. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199703000-00032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gürlek A, Schusterman MA, Evans GR, Gherardini G. Blood flow and microcirculatory changes in an ischemia-reperfusion injury model: experimental study in the rabbit. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1997;13:345-349. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang SY, Huang JJ, Tsao CK, et al. Does ischemia time affect the outcome of free fibula flaps for head and neck reconstruction? A review of 116 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1988-1995. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f448c8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hölzle F, Swaid S, Nolte D, Wolff KD. Nutritive perfusion at donor site after microvascular fibula transfer. Microsurgery. 2003;23:306-312. doi: 10.1002/micr.10143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Backer D, Foulon P. Minimizing catecholamines and optimizing perfusion. Crit Care. 2019;23:149. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2433-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hohlweg-Majert B, Ristow O, Gust K, Kehl V, Wolff KD, Pigorsch S. Impact of radiotherapy on microsurgical reconstruction of the head and neck. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1799-1811. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1263-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dornseifer U, Fichter AM, Von Isenburg S, Stergioula S, Rondak IC, Ninkovic M. Impact of active thermoregulation on the microcirculation of free flaps. Microsurgery. 2016;36:216-224. doi: 10.1002/micr.22523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Üstün GG, Aksu AE, Uzun H, Bitik O. The systematic review and meta-analysis of free flap safety in the elderly patients. Microsurgery. 2017;37:442-450. doi: 10.1002/micr.30156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]