Abstract

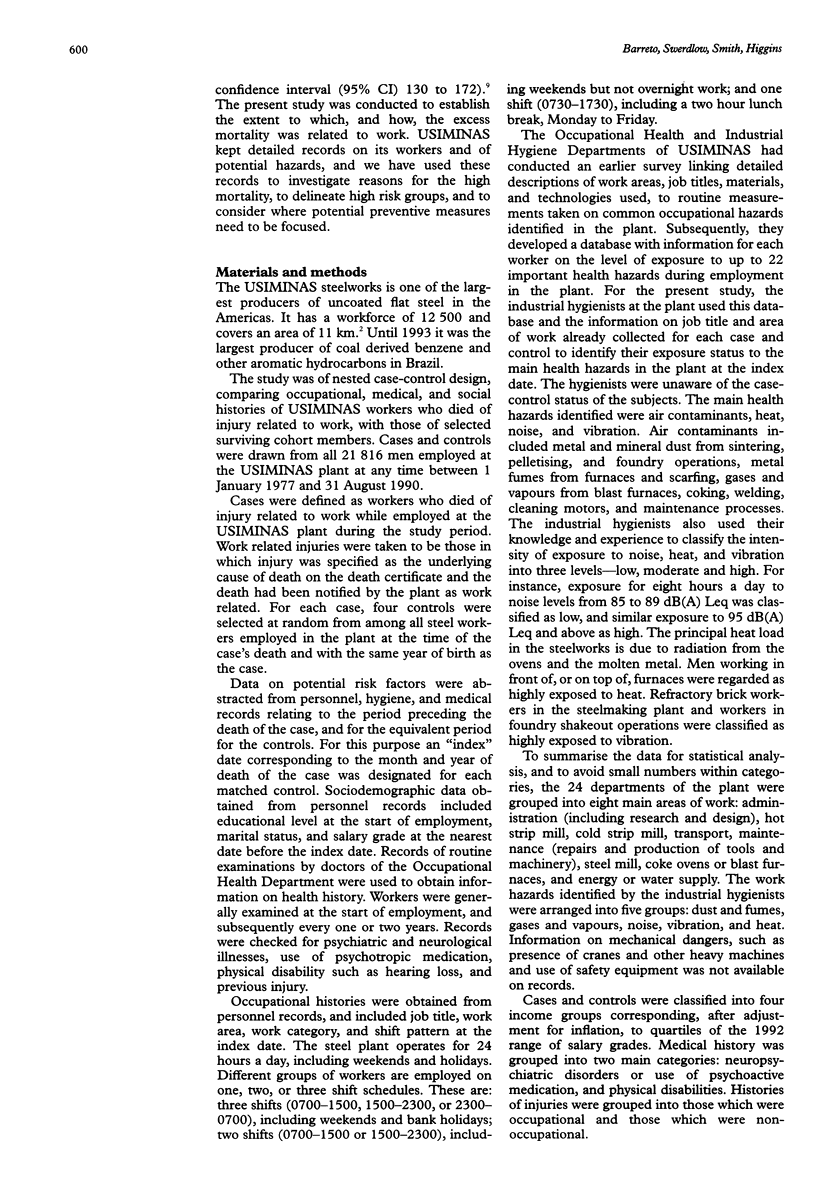

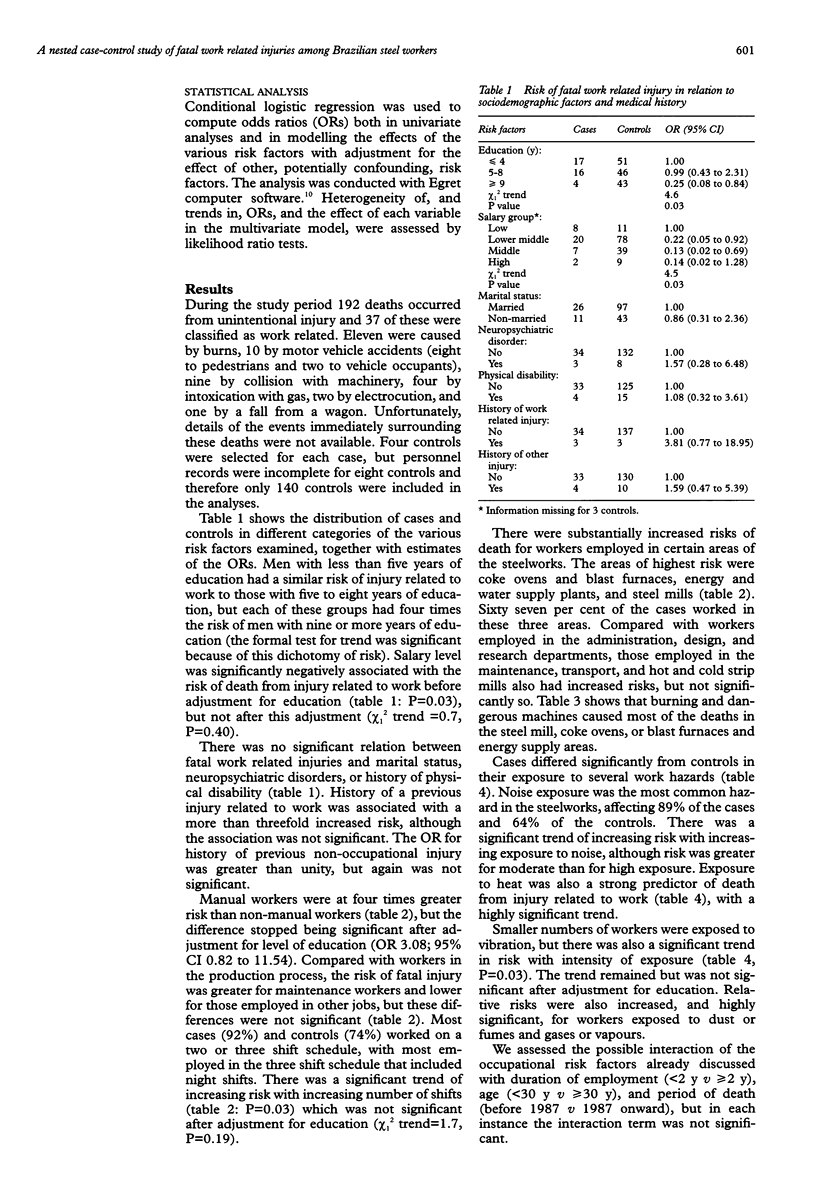

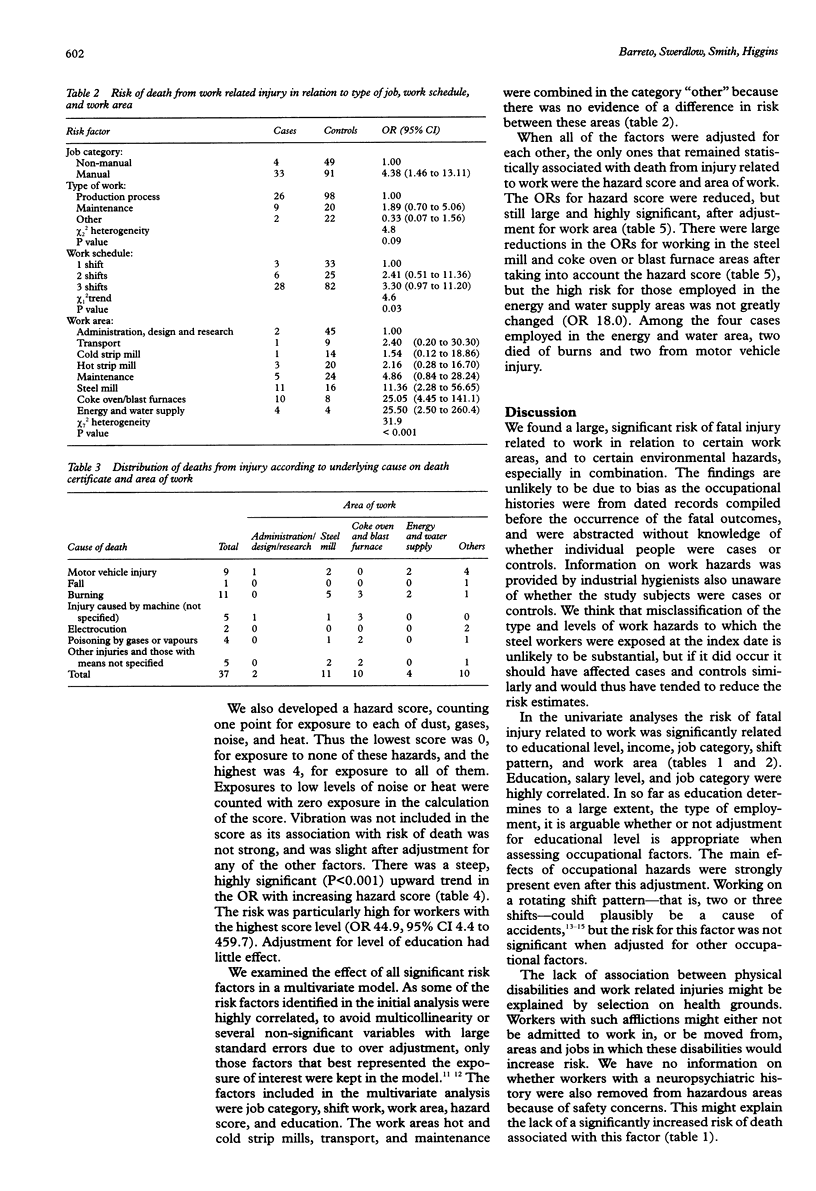

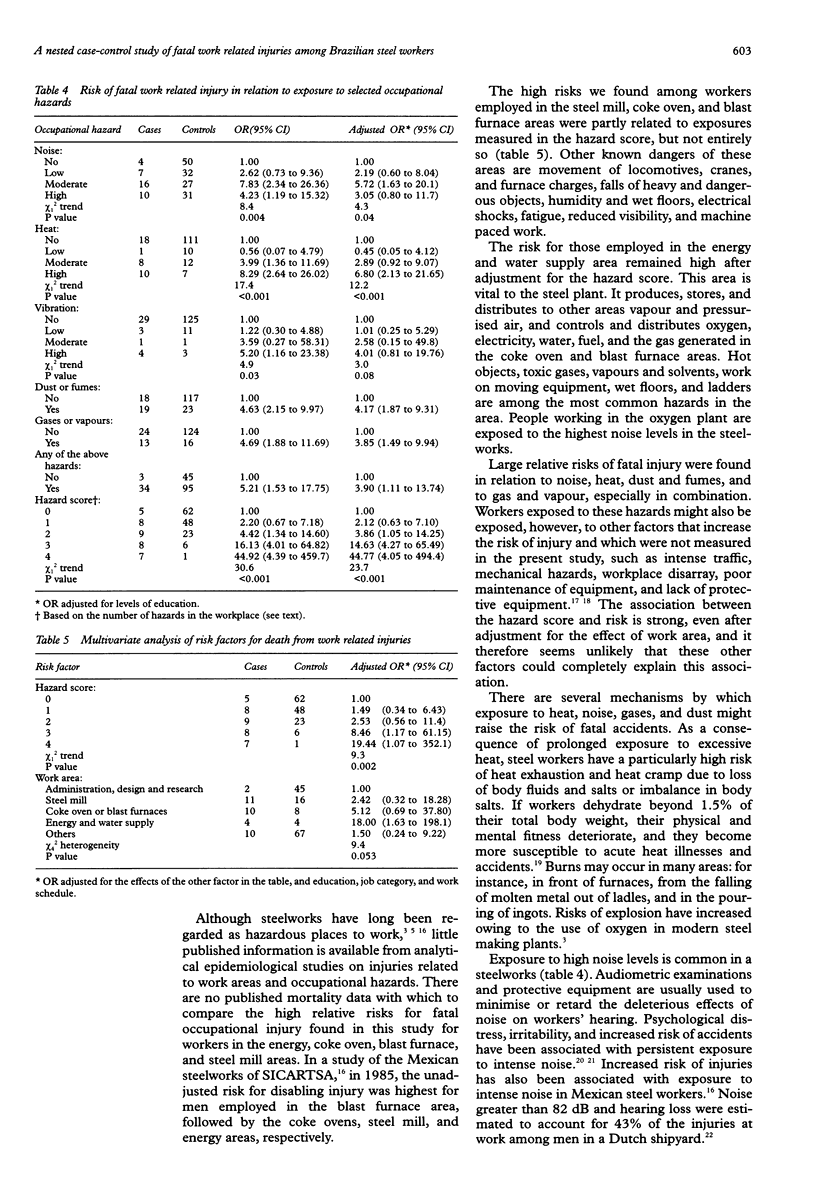

OBJECTIVES: To estimate the relative risk of death from work related injury in a steelworks, associated with exposure to various occupational hazards, sociodemographic factors, and medical history. MATERIAL AND METHODS: The study was a nested case-control design. It was based on a cohort of men employed in the steel plant of USIMINAS, Brazil between January 1977 and August 1990, who were followed up to November 1992. The cases were defined as all workers in the cohort who died from injury in the study period and whose death had been notified to the Brazilian Ministry of Labour as being related to work. Four controls per case, matched to cases on year of birth, were randomly selected from among workers employed in the plant at the time of death of the matching case. Data on potential risk factors for occupational injury were extracted from company records; for the controls these data were abstracted for the period preceding the death of the matching case. RESULTS: There were 37 deaths related to work injuries during the study period. Four surviving workers were selected as controls for each case, but for eight the personnel records were incomplete, leaving 140 controls in all. Significantly increased risk of fatal injury related to work was associated with exposure to noise, heat, dust and fumes, gases and vapours, rotating shift work, being a manual worker, and working in the steel mill, coke ovens, blast furnaces, and energy and water supply areas. Risk of fatal injury related to work increased with intensity of exposure to noise (P (trend) = 0.004) and heat (P < 0.001), and increased greatly with a hazard score that combined information on noise, heat, dust, and gas exposure (P < 0.001). Number of years of schooling (P = 0.03) and salary level (P = 0.03) were both negatively associated with risk. In a multivariate analysis including all these significant factors, only hazard score and area of work remained associated with death from injury related to work. The highest risks were for men exposed to all four environmental hazards (odds ratio (OR) 19.4; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.1 to 352.1) and those working in the energy supply area (OR 18.0; 1.6 to 198.1). CONCLUSIONS: The study identified parts of the steelworks and types of hazard associated with greatly increased risk of fatal accident. Research and measures to prevent accidents need to concentrate on these areas and the people working in them. The use of a hazard score was successful in identifying high risk, and similar scoring might prove useful in other industrial situations.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barreto S. M., Swerdlow A. J., Smith P. G., Higgins C. D., Andrade A. Mortality from injuries and other causes in a cohort of 21,800 Brazilian steel workers. Occup Environ Med. 1996 May;53(5):343–350. doi: 10.1136/oem.53.5.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decoufle P., Wood D. J. Mortality patterns among workers in a gray iron foundry. Am J Epidemiol. 1979 Jun;109(6):667–675. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukes-Dobos F. N. Hazards of heat exposure. A review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1981 Jun;7(2):73–83. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan-Baum E., Miller B. A., Waxweiler R. J. Lung cancer and other mortality patterns among foundrymen. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1981;7 (Suppl 4):147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health. 1989 Mar;79(3):340–349. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjellberg A. Subjective, behavioral and psychophysiological effects of noise. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1990;16 (Suppl 1):29–38. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskela R. S., Hernberg S., Kärävä R., Järvinen E., Nurminen M. A mortality study of foundry workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1976;2 (Suppl 1):73–89. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J. W., Lundin F. E., Jr, Redmond C. K., Geiser P. B. Long-term mortality study of steelworkers. IV. Mortality by work area. J Occup Med. 1970 May;12(5):151–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed S., Rabinowitz S., Green M. S. Noise exposure, noise annoyance, use of hearing protection devices and distress among blue-collar workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1994 Aug;20(4):294–300. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll van Charante A. W., Mulder P. G. Perceptual acuity and the risk of industrial accidents. Am J Epidemiol. 1990 Apr;131(4):652–663. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppäläinen A. M. Neurophysiological findings among workers exposed to organic solvents. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1981;7 (Suppl 4):29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L., Folkard S., Poole C. J. Increased injuries on night shift. Lancet. 1994 Oct 22;344(8930):1137–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90636-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suruda A. J. Work-related deaths in construction painting. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1992 Feb;18(1):30–33. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lucca S. R., Mendes R. Epidemiologia dos acidentes do trabalho fatais em área metropolitana da região sudeste do Brasil, 1979-1989. Rev Saude Publica. 1993 Jun;27(3):168–176. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101993000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]