Abstract

To understand the molecular determinants of measles virus (MV) virulence, we have used the SCID-hu thymus/liver xenograft model (SCID-hu thy/liv) in which in vivo MV virulence phenotypes are faithfully duplicated. Stromal epithelial and monocytic cells are infected by MV in thymus implants, and virulent strains induce massive thymocyte apoptosis, although thymocytes are not infected. To determine whether passage of an avirulent vaccine strain in human tissue increases virulence, we studied a virus isolated from thymic tissue 90 days after infection with the vaccine strain Moraten (pMor-1) and a virus isolated from an immunodeficient child with progressive vaccine-induced disease (Hu2). These viruses were compared to a minimally passaged wild-type Edmonston strain (Ed-wt) and the vaccine strain Moraten. pMor-1, Hu2, and Ed-wt displayed virulent phenotypes in thymic implants, with high levels of virus being detected by 3 days after infection (105.2, 102.8, and 103.4, respectively) and maximal levels being detected between 7 and 14 days after infection. In contrast, Moraten required over 14 days to grow to detectable levels. pMor-1 produced the highest levels of virus throughout infection, suggesting thymic adaptation of this strain. Similar to other virulent strains, Ed-wt, Hu2, and pMor-1 caused a decrease in the number of viable thymocytes as assessed by trypan blue exclusion and fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. Thymic architecture was also disrupted by these strains. Sequence analysis of the hemagglutinin (H) and matrix (M) genes showed no common changes in Hu2 and pMor-1. M sequences were identical in pMor-1 and Mor and varied in H at amino acid 469 (threonine to alanine), a position near the base of propeller 4 in the propeller blade/stem model of H structure. Further study will provide insights into the determinants of virulence.

Measles virus (MV) infects 30 million children and causes one million deaths worldwide each year as estimated by the World Health Organization (5). Despite its tremendous impact on public health, little is known about the regulation of MV growth or the determinants of virulence in vivo. To identify molecular determinants of MV growth in vivo, we previously employed a targeted molecular approach to examine the role of known noncoding regions and genes which have been postulated to be important for MV replication in vivo but are unnecessary for MV growth in Vero cells (26). The genetic characterization of isolates of live attenuated (LA) vaccine strains which appear to have reverted to a more virulent phenotype provides a second strategy for the identification of new determinants of MV growth in vivo. Such reversions might occur during prolonged replication of LA vaccines in human tissues.

The widely used LA vaccine strains Moraten and Schwarz were derived from the first licensed LA measles vaccine, Edmonston B, by further attenuation in chicken embryo cells at low temperature (7, 22). The Moraten and Schwarz strains are highly genetically related, reflecting their common ancestry and similar passage history, and they are safe and effective for most children (7, 21, 22). Their use has dramatically reduced the incidence of measles, from over 100 million cases in the prevaccine era to approximately 31 million cases in 1997 (5). However, fatal infections have been documented in immunodeficient children vaccinated with these strains (1, 12, 14, 15). The symptoms of infection occur many months after immunization, and the viruses isolated are similar to the original LA vaccine (1, 15), suggesting that in the absence of an effective host immune response, persistent infection with the vaccine strain can lead to fatal disease. Viruses isolated from these children could potentially represent virulent revertants of the original LA vaccine.

The growth of LA vaccines in an experimental model of human thymus engrafted in immunodeficient mice could also potentially result in readaptation and virulent reversion. In this model, human fetal thymus and liver are implanted under the renal capsule of a mouse with severe combined immune deficiency (SCID-hu thy/liv). Engraftment of these tissue fragments leads to the development of a structurally and functionally normal thymus, which can survive for up to 8 months (17). MV growth is restricted to engrafted human thymus, since murine cells are not productively infected by MV (29). The cell types infected by MV include thymic stromal epithelial cells, monocytes, and macrophages (2). Thymocytes are not infected, but MV replication within the implant leads to bystander thymocyte apoptosis (2).

In vivo virulence phenotypes are faithfully duplicated in the SCID-hu thy/liv model. Patient isolates grow to high titer within 7 days after infection, but LA vaccine strain growth is delayed (2). Little virus is detected after the first 2 weeks of LA vaccine infection, and large amounts of virus are produced by 1 month (2). Whether the virus growing at later times is a virulent revertant is unknown, but the absence of an effective antiviral B- or T-cell response in the SCID-hu thy/liv implant might allow prolonged LA MV replication, increasing the probability of isolating strains which grow efficiently in human cells, in a manner similar to that occurring in patients with immunodeficiency syndromes.

Prior to pursuing the genetic characterization of potential virulent revertants, we investigated whether such phenotypic reversion occurs. In these studies, we have characterized an MV strain recovered after prolonged growth of Moraten in a thy/liv implant (pMor-1 [passaged Moraten]) and have investigated whether Hu2, an MV strain isolated from a child with congenital immunodeficiency who died of disseminated measles after immunization with the Schwarz vaccine (12), has enhanced virulence in thy/liv implants. Both strains showed increased virulence in the thy/liv model. The identification of genetically related strains that differ in virulence provides a basis for the elucidation of sequences that govern MV virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

Stocks of MV strains Ed-wt, Moraten, and Hu2 were prepared and subjected to titer determination in Vero cells (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, Va.). Ed-wt is a minimally passaged derivative of the original Edmonston isolate (less than 15 passages in human kidney and Vero cells). Moraten and Schwarz (from which Hu2 was derived) were obtained by growth of the original Edmonston isolate in human kidney and amnion cells for more than 50 passages (Edmonston-Enders strain) followed by further passage in chicken embryo intra-amniotic cavity and fibroblasts (20). After its original isolation, Hu2 was passaged in Vero cells (19). These strains were propagated in Vero cells for one or two passages prior to use in these experiments.

pMor-1 was obtained by coculturing B95-8 marmoset B lymphoblastoid cells (ATCC) in complete RPMI (10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, 12.5 mM HEPES, 50 μg of gentamicin per ml [Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.]) with a homogenate prepared from a single thy/liv implant harvested 90 days after infection with a Vero-passaged Moraten strain. B95-8 cells were selected for isolation since in vivo virulence is preserved after growth on these cells while passage through Vero cells results in a loss of virus pathogenicity in vivo (25). Infected B95-8 cells were maintained in complete RPMI until syncytium formation, indicative of MV cytopathic effect, was observed. The virus titer of this primary stock was determined by syncytial assay. Serial dilutions of the primary stock were made in complete RPMI. Dilutions were incubated with 105 B95-8 cells in triplicate in 96-well plates for three days at 37°C. The 50% tissue culture infective dose per milliliter was calculated by the Karber method (11).

A stock of pMor-1 for use in thy/liv infections was prepared in fresh human cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs) from births that were not complicated by perinatal or prenatal infection. CBMCs were purified by density gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.). The cells were maintained at a density of 5 × 106 to 1 × 107 cells/ml in complete RPMI containing 5 μg of phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml with a daily change of medium. Infected CBMCs were harvested at the time of maximal cytopathic effect, lysed by two freeze-thaw cycles, and centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. The virus titer of the supernatant fluid was determined by measurement of the 50% tissue culture infective dose per milliliter on B95-8 cells as described above and by measurement of plaque formation on Vero cells.

Infection of thy/liv implants.

thy/liv implants were engrafted under the renal capsule of male homozygous CB-17 scid/scid mice as previously described (17). For infection, the mice were anesthetized with Metofane, the left kidney was dissected, and each implant was inoculated directly with 1,000 PFU of virus. At the time of inoculation, implants were of variable size, but this difference was not greater than twofold by visual inspection. At harvest, the mice were sacrificed and the left kidney was removed en bloc. Implants were divided into thirds for plaque assay, cell counts, and histologic testing. For the plaque assay and cell counts, the implants were dissected away from the underlying kidney. For histologic analysis, the kidney tissue was not removed.

Virus growth in thy/liv implants.

MV growth was assessed by a plaque assay of thy/liv homogenates on the day of harvest, as previously described (26). Infected Vero cell monolayers were stained directly with neutral red or fixed with 9% formaldehyde–phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained with 1% crystal violet. Student’s t test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences in virus titers (StatView software; SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

Virus growth in cell lines.

B95-8 and Vero cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1. Virus growth was assessed by measurement of plaque formation on Vero cell monolayers. Each sample was assayed in triplicate, and virus production was recorded as the average of these three values.

Thymocyte cell number and fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis.

Thymocyte viability was assessed by using a suspension of thymocytes obtained by disrupting one-third of each implant gently between two glass slides into PBS–2% fetal calf serum. Debris was removed by filtration through a 30-μm-pore-size nylon filter (SpectraMesh; Spectrum, Houston, Tex.). Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion and by analysis of forward- and side-scatter patterns in flow cytometry with FACSCaliber instrumentation (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.) and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Thymus histology.

For histologic analysis, one-third of each implant with underlying kidney was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde–PBS for 24 to 72 h and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm) were cut from paraffin blocks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Light microscopy and photomicrography were performed with Nikon Eclipse instrumentation.

Sequence analysis of pMor-1.

RNA was prepared by the guanidinium thiocyanate technique from a Vero cell monolayer infected with pMor-1. cDNAs of MV matrix (M) and hemagglutinin (H) mRNAs were synthesized with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and amplified by PCR. Amplified fragments were sequenced directly in both directions by the Sanger technique with primers spaced at 400- to 500-base intervals as previously described (19). H amino acid sequences were aligned by using CLUSTALW (5a) and BOXSHADE (7a) programs.

RESULTS

Isolation of a virulent vaccine-derived MV strain from a thy/liv implant.

thy/liv implants infected with attenuated vaccine strain Moraten were assessed for 90 days after infection. Replicating virus first emerged from Moraten-infected implants after 7 to 21 days (2). At 7 and 14 days postinfection, virus growth was detectable in a few implants, but by 21 days, virus was detected in all infected implants (data not shown) and virus titers increased through 35 days (2). A single implant was harvested 90 days after infection, and no infectious virus was detectable by plaque assay after incubation for 5 days (data not shown), but longer cocultivation with B95-8 cells eventually resulted in virus isolation (pMor-1) as described below. Trypan blue exclusion demonstrated that a large number of thymocytes were present through 35 days after infection with Moraten, when large amounts of virus were produced (2). However, between 35 and 90 days after infection, the numbers of viable thymocytes decreased 100-fold (data not shown).

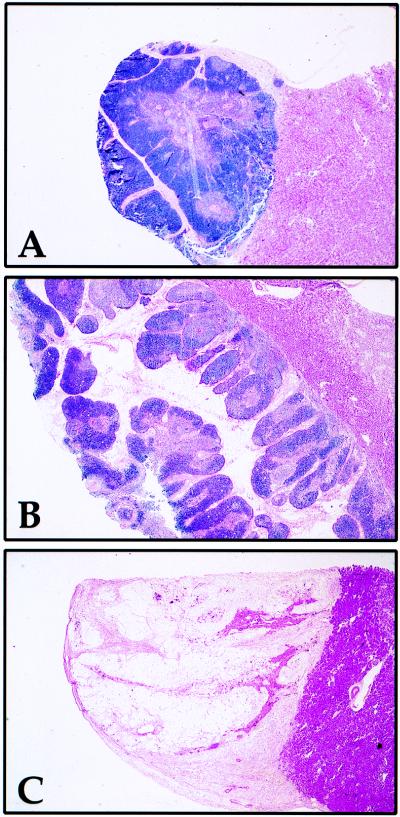

Histologic analysis demonstrated that the architecture of Moraten-infected implants was undisturbed and comparable to that of mock-infected implants 35 days after infection (Fig. 1A and B). The extent of thymic lobulation in these two implants was within the normal range of histologic variation for thy/liv implants. No evidence of viral cytopathic effect was seen at high magnification (data not shown). In contrast, by 90 days postinfection, the Moraten-infected implant sampled was hypocellular (Fig. 1C), suggesting the emergence of a more virulent strain of Moraten capable of causing thymic damage, although normal implant involution could not be excluded. To investigate the presence of a more virulent strain, a portion of this implant was cocultured with B95-8 cells, and MV cytopathic effect was evident after 30 days (four blind passages).

FIG. 1.

Histology of SCID-hu thy/liv implant 90 days after infection with the Moraten vaccine strain of MV. One-third of each implant was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde–PBS. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Attached murine renal tissue lies below thymus implants. The morphology of mock-infected implants consists of individual lobes separated by fibrous stroma with densely cellular cortex surrounding a less cellular medullary zone containing Hassal’s corpuscles. (A) Mock-infected implant 35 days after infection. (B) Moraten-infected implant 35 days after infection. (C) Moraten-infected implant 90 days after infection. Magnification, ×23.

We have observed an increase in virus production 35 days after Moraten infection in six implants in two separate experiments (Fig. 2) (2), suggesting that many passaged Moraten strains could potentially be recovered. To date we have attempted to isolate virus from a single Moraten-infected implant harvested after 90 days. This virus was designated pMor-1 (for passaged Moraten-1).

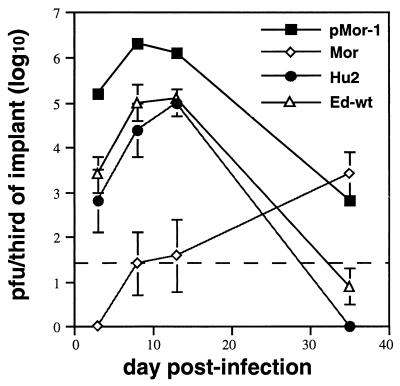

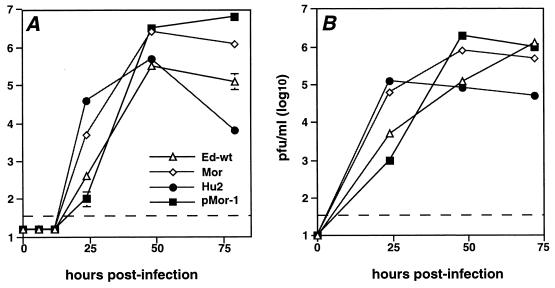

FIG. 2.

Growth of pMor, Hu2, Ed-wt, and Moraten strains of MV in thy/liv implants. Implants were infected with 103 PFU of virus. Datum points represent geometric mean titer of virus recovered from three implants. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Points without error bars have standard error bars smaller than the symbol.

Growth of vaccine-derived MV strains in SCID-hu thy/liv implants.

To assess whether the vaccine-derived strains pMor-1 and Hu2 have virulent phenotypes in vivo, the growth of these strains in thy/liv implants was compared to that of Moraten and Ed-wt. Low levels of virus were detected 14 days after infection in Moraten-infected implants (Fig. 2), but virus production increased from 14 to 28 days as observed previously (2). Ed-wt grew more rapidly, producing 100-fold more virus 3 days after infection (P = 0.001) and reaching peak levels that were approximately 1,000-fold greater than those of Moraten between 7 and 14 days after infection (P = 0.01). After 14 days of infection, Ed-wt virus production declined, presumably due to the virus-induced death of susceptible cells. The kinetics of replication of vaccine-derived virus strains pMor-1 and Hu2 were similar to that of Ed-wt, with virus being detected by 3 days and peak virus production 7 to 14 days after infection. thy/liv implants infected with Hu2 and Ed-wt produced similar amounts of virus. pMor-1-infected implants produced 10- to 100-fold more virus than did Hu2- and Ed-wt-infected implants (P = 0.04 and 0.03, respectively) and 10,000-fold more virus than did Moraten-infected implants (P = 0.02) in the first 14 days after infection. It is unlikely that this difference in virus production was due to implant variability, since implant sizes varied at most twofold. Similar to other virulent viruses (2, 26), pMor-1 and Hu2 replication declined after 14 days.

Effect of vaccine-derived strains on implant thymocytes.

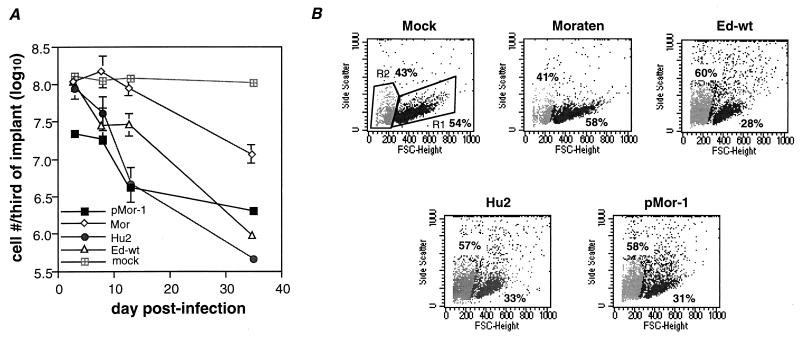

To investigate the effect of infection with the vaccine-derived strains on thymocyte survival, thymus cells were collected at various times after infection. Viability was assessed by light microscopy with trypan blue exclusion and by flow cytometry with forward- and side-scatter analysis. Fourteen days after infection, numbers of viable cells declined 5-fold in Ed-wt-infected implants, 10-fold in pMor-1-infected implants, and 30-fold in Hu2-infected implants (Fig. 3A). Forward- and side-scatter plots showed a reduction of events in the mononuclear cell region and an increase in cell debris in implants infected with these three MV strains (Fig. 3B). In contrast, 14 days after Moraten infection, the number of viable thymocytes had not decreased significantly and cell populations in forward- and side-scatter plots were comparable to those for mock-infected implants (Fig. 3). Between 14 and 35 days after infection, thymocyte numbers continued to decline in Ed-wt, Hu2, and pMor-1-infected implants. Thymocyte numbers in Moraten-infected implants also began to decline at this time (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Effect of MV growth on numbers of viable thymocytes in SCID-hy thy/liv implants. (A) Viable thymocytes assessed by trypan blue exclusion. For infected implants, points represent the geometric means of data from implants which were used in the calculation of geometric mean titers in Fig. 2. A single mock infected implant was harvested at each time point for comparison. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of cells harvested from disrupted thy/liv implants 14 days after infection. Viable thymus cells are found in gate R1. Dead cells and debris are located in gate R2. Percentages indicate region statistics (percentage of total events) for each gate. Data from a single representative implant for each virus are shown.

Effect of vaccine-derived MV strains on implant architecture.

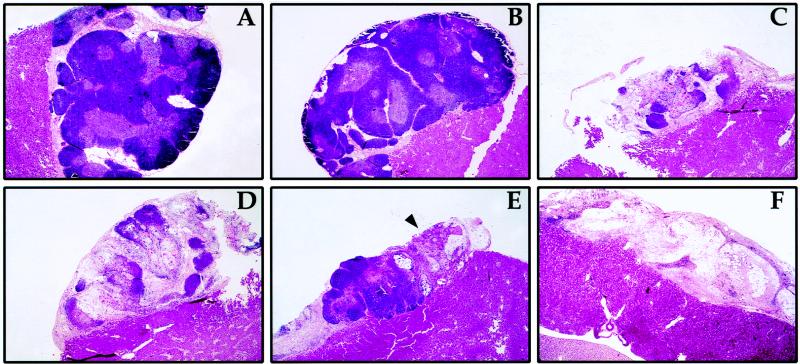

The replication of virulent MV strains results in implant hypocellularity with loss of medullary and cortical thymocytes due to virus-induced thymocyte apoptosis. To determine whether the replication of vaccine-derived strains induced similar disruption of implant architecture, the histologic appearance of infected implants was assessed by hematoxylin-and-eosin staining. Seven days after infection with Ed-wt, Hu2, and pMor-1, small foci of pyknotic thymocytes were observed (data not shown). Medullary zones of infected implants contained a larger number of pyknotic foci than did cortical zones. The architecture of mock- and Moraten-infected implants was preserved after 28 days, with densely cellular cortex and less cellular medullary zones characteristic of intact thymus (Fig. 4A and B). At higher magnification, a small number of pyknotic thymocytes were found in the medullary zone of one of three Moraten-infected implants. Pyknotic medullary thymocytes were not observed in mock-infected implants. Marked implant hypocellularity was found 14 days after infection with Ed-wt, Hu2, and pMor-1 (Fig. 4C to E). Loss of cortical and medullary thymocytes was observed, but Hassall’s corpuscles were still present. At 35 days after infection with pMor, implant architecture was entirely disrupted (Fig. 4F), with eosinophilic stroma and no evidence of Hassall’s corpuscles or cortical or medullary thymocytes. Ed-wt- and Hu2-infected implants had a similar appearance (data not shown). Moraten-infected implants were smaller than but morphologically similar to mock-infected implants (data not shown). In dual-label immunofluorescence experiments, MV antigens were found in stromal epithelial cells and monocytes in pMor-1-infected thy/liv implants (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Histology of SCID-hu thy/liv implants after infection with virulent revertants of MV vaccines. Implants were fixed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (A) Mock-infected implant 28 days after infection. (B) Moraten-infected implant 28 days after infection. (C) Ed-wt infected implant 14 days after infection. (D) Hu2-infected implant 14 days after infection. (E) pMor-infected implant 14 days after infection. The arrowhead indicates a region of hypocellular thymus. (F) pMor-infected implant 35 days after infection. Magnification, ×19.75.

Growth of vaccine-derived MV strains in cell lines.

To determine the characteristics of the growth of vaccine-derived MV strains in vitro, virus replication in Vero and B95-8 cells was studied. Hu2 and Vero-passaged Moraten strains produced 10 to 300 times more virus than did Ed-wt and pMor-1 24 h after infection of both cell types (Fig. 5A, B; P < 0.01 for all datum points). Virus production by all four strains was similar by 48 h after infection.

FIG. 5.

Growth of vaccine-derived MV strains in cell lines. Cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1. (A) Virus growth in Vero cells. (B) Virus growth in B95-8 cells. Each point is the geometric mean of results from duplicate wells. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Points without error bars have standard error bars smaller than the symbol. Data from one of two experiments is shown in each panel. The limit of detection of the plaque assay is indicated by the dashed line.

Sequencing of pMor-1 M and H genes.

Previously reported sequence analysis of Hu2 demonstrated nucleotide substitutions resulting in significant amino acid changes in the M and H proteins compared to Schwarz (6, 19). Therefore, the M and H genes of pMor-1 were sequenced to assess whether similar changes were associated with phenotypic change. Direct sequencing of amplified products from RT-PCR indicated no nucleotide changes in the M gene and a single nucleotide substitution (A to G) at nucleotide 427 in the H gene, resulting in a change from a threonine to an alanine at residue 469, that was not present in Hu2 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide substitutions in vaccine and vaccine-derived strains in comparison with Ed-wta

DISCUSSION

To determine whether in vivo passage of vaccine strains of MV alters their virulence and to begin to elucidate the determinants of MV growth and virulence in vivo, we have studied the growth of vaccine-derived virus strains pMor-1 and Hu2 in thy/liv implants. These viruses had lost the attenuated Moraten phenotype and grew with kinetics similar to Ed-wt, the minimally passaged parent of the Moraten and Schwarz vaccine strains. thy/liv implant infection with pMor-1 and Hu2 resulted in high levels of virus production, suggesting that prolonged growth of live attenuated MV vaccine in human tissue selects for a virus adapted to grow in human tissues in vivo. Our data suggest that the adverse outcomes associated with immunization of patients suffering from congenital and acquired immunodeficiency syndromes are due to the emergence of an MV strain with increased virulence in a host unable to mount a sufficient immune response to clear the originally inoculated vaccine virus. This situation is mimicked in the SCID-hu mouse. Sequence analyses of pMor-1 H and M and other isolates derived from immunodeficient patients demonstrate that these human tissue-passaged vaccine isolates are highly related to parent vaccine strains (1, 15).

Implants infected with pMor-1 produced higher levels of virus than did those infected with Ed-wt and Hu2. The difference in the level of virus production might be a consequence of adaptation to growth in thymus by pMor-1 and/or the different passage history of these three strains. To prevent the attenuation which occurs after passage in Vero cells (25), pMor-1 was grown in B95-8 cells and human CBMCs while Hu2 and Ed-wt were obtained as Vero-passaged isolates. The effect of passage on virus virulence in the SCID-hu thy/liv model is not yet definitively known. We have observed a variable effect of Vero passage on MV growth in SCID-hu thy/liv implants. A minimally passaged patient isolate (Chi-89) produced peak levels of virus (105.5 PFU/third of implant) 3 days after infection, similar to pMor-1 (2), while a molecular clone prepared from the original Edmonston isolate after many passages in Vero cells grew more slowly (peak on day 7) (26).

Models for studying the virulence of this human pathogen are limited. MV RNA and proteins are present following infection of transgenic mice expressing CD46; however, replicating virus has not been recovered (4, 16, 18). Monkeys are susceptible to MV and develop viremia, disease, and immune responses similar to infected humans (13, 27); however, minimal viremia occurs in monkeys infected with vaccine virus isolates derived from immunodeficient children with progressive disease (3). Therefore, immunocompetent monkeys do not appear to discriminate differences in virulence as effectively as the SCID-hu thy/liv model does. The SCID-hu thy/liv implant is particularly suitable for the study of MV virulence, since it can discriminate such differences and can be used to isolate closely related, phenotypically different strains.

Infection of implants with pMor-1, Hu2, and Ed-wt resulted in high levels of thymocyte death and disruption of implant architecture. Interestingly, the level of virus production in thy/liv implants did not correlate precisely with the kinetics of thymocyte death. pMor-1 produced more virus than Hu2 and Ed-wt in the first 7 days of infection, but the rate of thymocyte loss was equivalent in implants infected with these three strains. These data suggest that factors other than the level of viral replication play a role in MV-induced thymocyte death, as was suggested by growth of a recombinant mutant strain which fails to express the V nonstructural protein. Implants infected with this strain produced large amounts of virus, but minimal thymocyte death occurred (26).

The rates of growth of vaccine-derived strains in cell culture were different from those observed in thy/liv implants. Hu2 and Moraten grew faster than pMor-1 and Ed-wt did. These growth kinetics appear to reflect the adaptation of these strains to tissue culture cells, since Hu2 and Moraten have been more extensively passaged in Vero cells than pMor-1 and Ed-wt.

We have previously demonstrated that expression of the C gene, V gene, and 5′ noncoding region of the F gene is required for efficient MV growth in the thy/liv implant (26). The isolation of a virulent virus after prolonged growth in human tissue will allow us to identify additional determinants of virulence. The molecular basis of pMor-1 and Hu2 virulence is unknown. The single nucleotide change in the pMor H gene is predicted to result in the substitution of an alanine for a threonine which is conserved in the H genes of over 140 different measles strains listed in GenBank. A change at position 469 (also an alanine) was found in only one other MV strain, Philadelphia 26. This site could potentially interact with the MV receptor CD46, since it is predicted to lie in a β-sheet on the external surface of H, according to a predicted structure derived by sequence alignment and molecular modeling (9). Amino acid residues nearby are required for various H protein functions. A tyrosine (Y) nearby at position 481 is critical for the binding of MV Edmonston H to CD46 (8). Y481 and an additional amino acid (valine at position 451) are also important for downregulation of CD46 expression, hemadsorption, and HeLa cell fusion (10).

Virulence determinants may also lie in regions other than the H and M genes. Sequence changes in H, P/C/V, and L have been detected in an MV strain that lost its pathogenicity in cynomolgus monkeys after passage in Vero cells (25), and sequences within L are important for the attenuation of the paramyxoviruses respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus 3 (23, 24, 28). Continued investigation with the SCID-hu thy/liv model and sequence characterization of phenotypically different, genetically related strains will improve our understanding of the molecular basis of MV virulence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael McChesney, Paul Rota, Bettina Bankamp, and Andy Golden for helpful discussion and suggestions.

This work was supported by research grants from the World Health Organization (D.E.G.); grants R01AI23047 (D.E.G.), T32AI07417 (A.V.), and T32AI07541 (A.V.) from the National Institutes of Health; and a grant from The Wellcome Trust (B.K.R.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Angel J B, Walpita P, Lerch R A, Sidhu M S, Masurekar M, DeLellis R A, Noble J T, Snydman D R, Udem S A. Vaccine-associated measles pneumonitis in an adult with AIDS. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:104–106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-2-199807150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auwaerter P G, Kaneshima H, McCune J M, Wiegand G, Griffin D E. Measles virus infection of thymic epithelium in the SCID-hu mouse leads to thymocyte apoptosis. J Virol. 1996;70:3734–3740. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3734-3740.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auwaerter, P. G., P. A. Rota, W. R. Elkins, R. J. Adams, T. DeLozier, Y. Shi, W. J. Bellini, B. R. Murphy, and D. E. Griffin. Measles virus infection in rhesus macaques: Altered immune responses and comparison of the virulence of six different virus strains. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Blixenkrone-Moller M, Bernard A, Bencsik A, Sixt N, Diamond L E, Logan J S, Wild T F. Role of CD46 in measles virus infection in CD46 transgenic mice. Virology. 1998;249:238–248. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward global measles control and regional elimination, 1990–1997. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1998;47:1049–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.CLUSTALW software. 25 June 1999, revision date. [Online.] http://dot.imgen.bcm.tmc.edu:9331/multi-align/multi-align/html. Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex. 29 July 1999, last date accessed.

- 6.Curran M D, Rima B K. Nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the matrix protein of a recent measles virus isolate. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2407–11. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-9-2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilleman M, Buynak E, Weibel R, Stokes J, Whitman J, Leagus M. Development and evaluation of the Moraten measles vaccine. JAMA. 1968;206:587–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Hofman, K., and M. Buron. 17 July 1999, revision date. BOXSHADE, version 3.21. [Online.] http://www.isrec.isb-sib.ch/software/BOX_form.html. 29 July 1999, last date accessed.

- 8.Hsu E C, Sarangi F, Iorio C, Sidhu M S, Udem S A, Dillehay D L, Xu W, Rota P A, Bellini W J, Richardson C D. A single amino acid change in the hemagglutinin protein of measles virus determines its ability to bind CD46 and reveals another receptor on marmoset B cells. J Virol. 1998;72:2905–2916. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2905-2916.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langedijk J P M, Daus F J, van Oirschot J T. Sequence and structure alignment of paramyxoviridae attachment proteins and discovery of enzymatic activity for a morbillivirus hemagglutinin. J Virol. 1997;71:6155–6167. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6155-6167.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lecouturier V, Fayolle J, Caballero M, Carabana J, Celma M L, Fernandez-Munoz R, Wild T F, Buckland R. Identification of two amino acids in the hemagglutinin glycoprotein of measles virus (MV) that govern hemadsorption, HeLa cell fusion, and CD46 downregulation: phenotypic markers that differentiate vaccine and wild-type MV strains. J Virol. 1996;70:4200–4204. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4200-4204.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lennette E H, Schmidt N J. Diagnostic procedures for viral and rickettsial infections. New York, N.Y: American Public Health Association; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mawhinney H, Allen I V, Beare J M, Bridges J M, Connolly J H, Haire M, Nevin N C, Neill D W, Hobbs J R. Dysgammaglobulinemia complicated by disseminated measles. Br Med J. 1971;2:380–381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5758.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McChesney M B, Miller C J, Rota P A, Zhu Y D, Antipa L, Lerche N W, Ahmed R, Bellini W J. Experimental measles. I. Pathogenesis in the normal and the immunized host. Virology. 1997;233:74–84. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitus A, Holloway A, Evans A E, Enders J F. Attenuated measles vaccine in children with acute leukemia. Am J Dis Child. 1962;103:413–418. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1962.02080020425051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monafo W J, Haslam D B, Roberts R L, Zaki S R, Bellini W J, Coffin C M. Disseminated measles infection after vaccination in a child with a congenital immunodeficiency. J Pediatr. 1994;124:273–276. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mrkic B, Pavlovic J, Rulicke T, Volpe P, Buchholz C J, Hourcade D, Atkinson J P, Aguzzi A, Cattaneo R. Measles virus spread and pathogenesis in genetically modified mice. J Virol. 1998;72:7420–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7420-7427.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Namikawa R, Weilbaecher K N, Kaneshima H, Yee E J, McCune J M. Long-term human hematopoiesis in the SCID-hu mouse. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1055–1063. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rall G F, Manchester M, Daniels L R, Callahan E M, Belman A R, Oldstone M B A. A transgenic mouse model for measles virus infection of the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4659–4663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rima B K, Earle J A, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Liebert U G, Carstens C, Carabana J, Caballero M, Celma M L, Fernandez-Munoz R. Sequence divergence of measles virus haemagglutinin during natural evolution and adaptation to cell culture. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:97–106. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-1-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rota J S, Wang Z D, Rota P A, Bellini W J. Comparison of sequences of the H, F, and N coding genes of measles virus vaccine strains. Virus Res. 1994;31:317–330. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarz A, et al. Extensive clinical evaluations of highly attenuated live measles vaccine. JAMA. 1967;199:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarz A. Immunization against measles: development and evaluation of a highly attenuated live measles vaccine. Ann Paediatr. 1964;202:241–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skiadopoulos M H, Durbin A P, Tatem J M, Wu S L, Paschalis M, Tao T, Collins P L, Murphy B R. Three amino acid substitutions in the L protein of the human parainfluenza virus type 3 cp45 live attenuated vaccine candidate contribute to its temperature-sensitive and attenuation phenotypes. J Virol. 1998;72:1762–1768. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1762-1768.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skiadopoulos M H, Surman S, Tatem J M, Paschalis M, Wu S L, Udem S A, Durbin A P, Collins P L, Murphy B R. Identification of mutations contributing to the temperature-sensitive, cold-adapted, and attenuation phenotypes of the live-attenuated cold-passage 45 (cp45) human parainfluenza virus 3 candidate vaccine. J Virol. 1999;73:1374–1381. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1374-1381.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeda M, Kato A, Kobune F, Sakata H, Li Y, Shioda T, Sakai Y, Asakawa M, Nagai Y. Measles virus attenuation associated with transcriptional impediment and a few amino acid changes in the polymerase and accessory proteins. J Virol. 1998;72:8690–8696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8690-8696.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valsamakis A, Schneider H, Auwaerter P G, Kaneshima H, Billeter M A, Griffin D E. Recombinant measles viruses with mutations in the C, V, or F gene have altered growth phenotypes in vivo. J Virol. 1998;72:7754–61. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7754-7761.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Binnendijk R S, van der Heijden R W J, Osterhaus A D M E. Monkeys in measles research. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;191:135–148. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78621-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitehead S S, Firestone C Y, Karron R A, Crowe J E, Jr, Elkins W R, Collins P L, Murphy B R. Addition of a missense mutation present in the L gene of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) cpts530/1030 to RSV vaccine candidate cpts248/404 increases its attenuation and temperature sensitivity. J Virol. 1999;73:871–877. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.871-877.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanagi Y, Hu H L, Seya T, Yoshikura H. Measles virus infects mouse fibroblast cell lines, but its multiplication is severely restricted in the absence of CD46. Arch Virol. 1994;138:39–53. doi: 10.1007/BF01310037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]