Abstract

The mouse p19Arf protein has both p53-dependent and p53-independent tumor-suppressive activities. Arf triggers sumoylation of many cellular proteins, including Mdm2 and nucleophosmin (NPM/B23), with which p19Arf physically interacts in vivo, and this occurs equally well in cells expressing or lacking functional p53. In an Arf-null NIH 3T3 cell derivative (MT-Arf cells) engineered to reexpress an Arf transgene driven by a zinc-inducible metallothionein promoter, sumoylation of endogenous Mdm2 and NPM proteins was initiated as p19Arf was induced and was observed before p53-dependent cell cycle arrest. Predominately nucleoplasmic molecules visualized by immunofluorescence with antibodies to small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) 1 localized to nucleoli as p19Arf accumulated there. Two Arf mutants, one of which binds to Mdm2 and NPM but is excluded from nucleoli and the other of which enters nucleoli but is handicapped in binding to Mdm2 and NPM, were defective in inducing sumoylation of these two target proteins and did not localize bulk sumoylated molecules to nucleoli. The CELO adenovirus protein, Gam1, which inhibits the SUMO activating enzyme (E1) and leads to down-regulation of the SUMO conjugating enzyme (E2/Ubc9), had no overt effect on the ability of p19Arf to activate p53 or the p53-responsive genes encoding Mdm2 and p21Cip1, despite the fact that Arf-induced sumoylation of Mdm2 was blocked. Reduction of Ubc9 levels with short hairpin RNAs rendered similar results. We suggest that Arf's p53-independent effects on gene expression and tumor suppression might depend on Arf-induced sumoylation.

Keywords: Gam1, Ubc9

The mouse Ink4a-Arf locus encodes two tumor-suppressor proteins, p16Ink4a and p19Arf (p14ARF in humans) that increase the growth-suppressive activities of the retinoblastomafamily proteins (Rb, p107, and p130) and the p53 transcription factor, respectively (1–3). By inhibiting Cdk4 and Cdk6, p16Ink4a helps to maintain Rb-family proteins in their active hypophosphorylated state, thereby inhibiting an E2F-dependent transcriptional program that is required for cellular DNA replication. In contrast, p19Arf antagonizes the p53 negative regulator Mdm2 (Hdm2 in humans) to trigger a p53 transcriptional response that can lead to proliferative arrest or apoptosis (4). Expression of Ink4a and Arf is regulated by distinct promoters upstream of alternative first exons whose products are spliced to a common second exon translated in alternative reading frames (from which Arf gets its name) (2). The two genes are induced by different stress signals and can be separately mutated or silenced in tumor cells (4).

Arf is activated by abnormally elevated and sustained mitogenic signals triggered by oncogenes but not by physiologic signaling thresholds conveyed by their appropriately regulated protooncogenic counterparts (4). For example, Arf is not induced by Myc or Ras during normal cell-cycle progression, but it is transcribed when such signals are constitutively enforced through Myc translocation or oncogenic Ras mutation. By activating p53, Arf serves to eliminate cells sustaining such mutations. However, Arf is not directly induced by DNA damage signals that trigger p53 activity through other signal-transduction pathways (3), although its loss can modify the damage response (5). In this sense, Arf serves as a fuse that gates mitogenic current, preventing abnormal cell proliferation in response to oncogene activation.

Although it is generally accepted that much of Arf's tumor-suppressor activity is mediated through p53, Arf also has p53-independent functions. Enforced expression of p19Arf can arrest the proliferation of p53-null cells, although much less efficiently than in cells that retain WT p53 (6). Primary mouse fibroblasts and B lymphocytes lacking both Arf and p53 grow faster in culture than do cells lacking only one of the two genes (3, 7), and mice lacking Arf, Mdm2, and p53 are much more prone to developing cancer than are mice lacking Mdm2 and p53 (8). Arf inhibits ribosomal RNA processing (9), interacts with topoisomerase I (10), and mediates p53-independent effects on gene expression by negatively regulating other transcription factors such as Btk coactivators (11), E2Fs (12–15), Myc (16, 17), and NFκB (18). These p53-independent activities of Arf are relatively poorly understood.

Enforced expression of p14ARF in human cells promotes sumoylation of several cotransfected cellular proteins, including Hdm2 (19, 20), the Werner helicase (WRN) (21), and the transcription factors E2F-1 and HIF-1α (22). Covalent addition of the small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMO-1, SUMO-2, and SUMO-3) to the ε-amino groups of certain lysine residues in protein substrates is carried out by a single E1 enzyme (the SUMO-1-activating enzyme 1/2 heterodimer also known as Aos1/Uba2) and a single E2 enzyme (Ubc9) in a process analogous to ubiquitination (23–25). Before conjugation, SUMO isoforms must be cleaved by a SUMO-specific protease to generate a C-terminal diglycine motif. Processed SUMO can then be activated in an ATP-dependent manner to form a thioester bond between SUMO and the catalytic cysteine of the E1. The E1 mediates SUMO transfer to a cysteine residue in Ubc9, after which one of several E3s can interact with both Ubc9 and protein substrates to accelerate the rate and magnitude of their sumoylation (26–28). Mammalian protein inhibitor of activated signal transducer and activator of transcription (PIAS) proteins appear to act as SUMO E3 ligases for LEF1, p53, and c-Jun, whereas the nucleoporin RanBP2 facilitates sumoylation of RanGAP1, Sp100, histone deacetylase (HDAC) 4, and Mdm2 (24, 25, 28). SUMO-specific proteases serve a dual role in the SUMO cascade, being required not only for initial SUMO processing but also for cleaving ligated SUMO from protein substrates (29–31). Unlike ubiquitin, SUMO-1 does not polymerize, so the formation of “ladders” of modified proteins is presumed to represent monosumoylation of multiple lysines. However, SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 have internal SUMO modification sites that allow formation of polymeric chains.

Effects of sumoylation are highly diverse and can influence protein transport, modulation of gene expression (usually, but not always, down-regulation), ubiquitination, DNA repair, and centromeric chromatid cohesion (24, 25, 32, 33). Here, we propose that the p53-independent tumor-suppressive effects of p19Arf may be mediated by its ability to enhance sumoylation of a diverse group of protein targets.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Culture Conditions. Human 293T cells, mouse NIH 3T3 fibroblasts, and zinc-inducible metallothionein promoter-containing (MT)-Arf cells (11) were cultured in DMEM (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% FCS (HyClone), 4 mM glutamine, and 100 units each of penicillin and streptomycin. Primary mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) of various genotypes (8) were cultured as described in ref. 34.

Expression Vectors. cDNAs encoding C-terminally processed forms of SUMO were amplified by reverse transcription and PCR using 1 μg of RNA template from 293T cells, Moloney murine leukemia virus RT (Invitrogen), and HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with the following primers: SUMO-1 (sense), 5′-gcgggatcctctgaccaggaggcaaaaccttcaactg-3′; (antisense), 5′-gcgctcgagctaaccccccgtttgttcctgataaac-3′; SUMO-2 (sense), 5′-gcgggatccgccgacgaaaagcccaaggaaggagtc-3′; (antisense), 5′-gcgctcgagctaacctcccgtctgctgttggaacac-3′; SUMO-3 (sense), 5′-gcgggatcctccgaggagaagcccaaggagggtgtg-3′; (antisense), 5′-gcgctcgagctaacctcccgtctgctgctggaacac-3′. Products cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega) were isolated with BamHI and XhoI and cloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) harboring an engineered His6 tag constructed by insertion of the following annealed oligonucleotides into the pcDNA3 KpnI and XhoI sites: (sense), 5′-cgccaccatggctcatcatcatcctcatcatggtg-3′ and (antisense) 5′-gatccaccatgatgatgatgatgatgagccatggtggcggtac-3′. pcDNA3-His6 SUMO-1 was digested with KpnI, blunted with DNA polymerase II Klenow fragment, and digested with XhoI to release the fragment encoding His6-SUMO-1. This fragment was ligated into a murine stem cell virus (MSCV)-internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-GFP vector (8) that had been digested with EcoRI, blunted as above, and digested with XhoI. pcDNA3-HA-Arf (HA, hemagglutinin) and pcDNA-Mdm2 were made previously (35). DNA fragments encoding HA-Arf, HA-Arf Δ2–14, and HA-Arf Δ26–37 (36) were isolated from pSRa-MSV-TKneo (37) by digestion with EcoRI and were recloned into the EcoRI sites of pcDNA3 and MSCV-IRES-PURO (8). pSG9M-myc-Gam1 and pSG9M-myc-Gam1 mutant (258L, 265A) (38) were used for transfection. The cDNAs were amplified by PCR with the following primers: (sense), 5′-tttgatatcatggaacaaaaactcatctc-3′; (antisense), 5′-tttctcgagttacagagaatggtagg-3′. After digestion with EcoRV and XhoI, purified fragments were recloned into the SnaBI and XhoI sites of MSCV-IRES-PURO. Cells infected with MSCV-IRES-PURO viruses were not selected in puromycin. Ubc9 short hairpin RNA was generated from the following annealed primers: (sense), 5′-gatccccgggaaggaggcttgttcaattcaagagattgaacaagcctccttc-3′; (antisense), 5′-agcttttccaaaaagggaaggaggcttgttcaatctcttgaattgaacaagc-3′. These annealed primers were inserted into the BglII and HindIII sites of pSUPER.retro.puro (Oligoengine, Seattle).

Vector Transduction and Protein Detection. Cotransfection of expression plasmids into 293T cells was performed by using FuGENE 6 (Roche, Indianapolis) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mouse cells were infected at >90% efficiency with MSCV-IRES-GFP or MSCV-IRES-PURO vectors encoding genes of interest under control of the MSCV promoter. Cells harvested 3 days later were resuspended in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors; proteins in centrifuged lysates were quantified by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce), electrophoretically separated on polyacrylamide gels containing SDS, transferred to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes (Millipore), and detected, all as described in ref. 37, with 5C3 mAb to p19Arf (39), Mdm2 (mAb 2A10), NPM (32-5200, Zymed), Myc tagged-Gam1 (MAb 9E10), p53 (FL-393), p21Cip1 (C-19), and Ubc9 (H-81) (the latter three from Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For purification of His6-tagged sumoylated proteins, 10% of a trypsinized cell suspension was taken for direct protein immunoblotting. The remaining cells were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 8 M urea, and His6-tagged proteins recovered with nickel beads (Qiagen) were eluted with imidazole, diluted with sample buffer, and separated on gels containing SDS as described in ref. 37. After transfer to membranes, proteins were immunoblotted with antibodies to SUMO-1 (33-2400, Zymed), Mdm2, and NPM.

Results

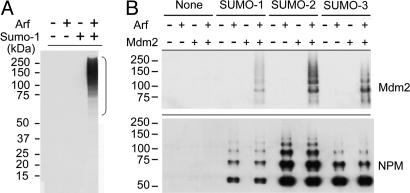

Sumoylation Induced by Mouse p19Arf. Plasmids encoding p19Arf and His6-SUMO-1 were cotransfected into human 293T cells, and His-tagged proteins recovered on nickel beads in the presence of 8 M urea were electrophoretically separated on denaturing gels. Immunoblotting with antibodies to SUMO-1 revealed that introduction of p19Arf greatly increased net protein sumoylation (Fig. 1A). 293T cells do not express active p53 and do not undergo cell cycle arrest when transfected with p19Arf, implying that neither p53 nor perturbations in cell-cycle progression are essential for this process. Immunoblotting of recovered His-tagged proteins with antibodies to Mdm2 and NPM, two proteins that physically interact with p19Arf, demonstrated that both could be multisumoylated, regardless of which SUMO isoform was used (Fig. 1B). The mobilities and spacing of these protein species, particularly obvious for NPM (unmodified molecular mass = 37 kDa), and the similar ladders obtained by using SUMO-1, SUMO-2, and SUMO-3 argue for sumoylation at multiple sites. Although sumoylated lysine residues often are found within ψKXE consensus sequences, where ψ is an aliphatic residue (26, 31), mutation of three such consensus sequences in NPM (lysines 24, 32, and 54) alone or in combination did not eliminate sumoylation (data not shown), consistent with studies performed elsewhere with p14ARF and WRN (21). Cotransfection of p19Arf together with His6-SUMO-1 and expression plasmids encoding a number of other proteins that do not bind directly to p19Arf failed to show sumoylation of two other nucleolar proteins (ribosomal protein L7 and fibrillarin), three other known SUMO targets (HDAC-1 and HDAC-2, and Ran-GAP1), or p53 (negative data not shown). Although p53 was previously reported to undergo p14ARF-dependent sumoylation, this required cointroduction of Mdm2, which can bind to both p14ARF and p53 simultaneously (20). Therefore, it appears that a physical interaction between p19Arf and selected target proteins is necessary for their efficient sumoylation.

Fig. 1.

Arf-induced sumoylation of Mdm2, NPM, and other cellular proteins. (A) After cotransfection of expression plasmids encoding p19Arf and His6-SUMO-1 into 293T cells (as indicated at the top), proteins from cell lysates affinity-purified on nickel resin in buffer containing 8 M urea were electrophoretically separated on denaturing gels containing SDS and were immunoblotted with antibody to SUMO-1. The positions of marker proteins of known molecular masses (kDa) are indicated on the left of A (and, similarly, in subsequent figures). The bracket indicates the positions of sumoylated proteins. (B) Proteins from cells cotransfected with the indicated expression plasmids (top) were resolved as above and were blotted with antibodies to Mdm2 (Upper) and NPM (Lower). Based on mass, the fastest-migrating NPM species appears to represent the monosumoylated form.

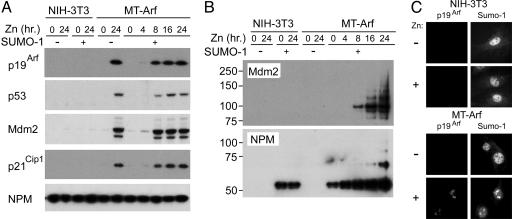

Timing of Arf-Induced Sumoylation and Localization of Sumoylated Molecules to Nucleoli. We next studied Arf-induced sumoylation of Mdm2 and NPM in MT-Arf cells, an Arf-null NIH 3T3 cell derivative into which we had previously introduced an integrated Arf transgene regulated by the zinc-inducible metallothionein promoter (11). MT-Arf cells infected with a retrovirus encoding processed His6-SUMO-1 were treated 3 days later with 80 μM zinc for various periods, and cellular proteins were separated on denaturing gels and immunoblotted with antibodies to p19Arf, p53, and to both Mdm2 and p21, which are encoded by canonical p53-responsive genes (Fig. 2A). Importantly, the levels of p19Arf expressed in induced MT-Arf cells approximate those observed in primary MEFs undergoing replicative senescence. Arf was first detected after 4 h of zinc treatment and achieved high levels by 8 h, well before most MT-Arf cells exited the cell cycle (at 20–24 h; refs. 9 and 11). As expected, p53 was stabilized, and Mdm2 and p21Cip1 were induced with similar kinetics (Fig. 2 A).

Fig. 2.

Induction of sumoylation in inducible MT-Arf cells. (A) MT-Arf cells and parental Arf-null NIH 3T3 infected with a retroviral vector encoding His6-SUMO1 were induced with zinc sulfate for the times indicated at the top. Total cellular proteins separated on denaturing gels were transferred to a membrane and blotted with antibodies to the proteins indicated at the left. (B) Proteins in the same cell lysates adsorbed to nickel beads were recovered, separated on denaturing gels, and blotted with antibodies to Mdm2 (Upper) and NPM (Lower). NPM is basally monosumoylated in NIH 3T3 cells (left lanes). (C) Cells treated with zinc (or not) (indicated at left) to induce p19Arf (Lower) or not (Upper) were immunostained with antibodies to p19Arf and SUMO-1 as indicated at the top. Arf localized SUMO-1-stained molecules to nucleoli (Lower).

His-tagged proteins affinity-purified from the same cells under denaturing conditions in 8 M urea were separated and immunoblotted with antibodies to Mdm2 and NPM (Fig. 2B). Sumoylation of Mdm2 was detected as the protein was induced and increased throughout the duration of the experiment (Fig. 2B Upper), even though parallel increases in total Mdm2 protein were not seen at the later time points (Fig. 2 A). Although most Mdm2 protein migrated as a characteristic doublet, minor and more slowly migrating species (Figs. 2 A and 4B) corresponded in their mobilities to sumoylated forms. NPM, which is a very abundant nucleolar protein, was sumoylated in Arf-null NIH 3T3 cells, probably at only one site based on the apparent molecular mass of the single modified protein species. NPM monosumoylation was seen in uninduced MT-Arf cells, but NPM sumoylation increased after p19Arf induction, and multisumoylated species were detected at later times.

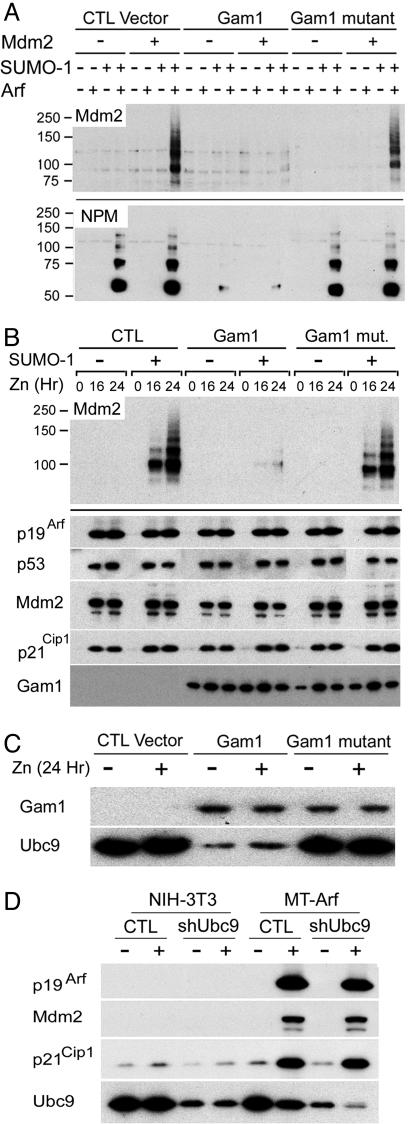

Fig. 4.

Reversal of Arf-induced sumoylation. (A) 293T cells were cotransfected with the combinations of expression vectors indicated at the top. Proteins adsorbed to nickel resin in 8 M urea were separated on denaturing gels and blotted with antibodies to Mdm2 (Upper) and NPM (Lower). (B) MT-Arf cells infected with a retroviral vector encoding His6-SUMO-1 together with an empty control retroviral vector (CTL), or those encoding either Gam1 or an inactive Gam1 mutant, were induced with zinc sulfate for the indicated times (top). Proteins purified on nickel beads were separated and blotted with antibodies to Mdm2 to reveal sumoylation. Total unfractionated proteins from the same cell lysates were blotted with antibodies to the proteins indicated at the left. (C) Cellular proteins harvested 24 h after zinc induction were separated on separate gels and immunoblotted with antibodies to Myc-tagged Gam1 and Ubc9. (D) NIH 3T3 and MT-Arf cells infected for 48 h with a retroviral vector encoding short hairpin RNA directed to Ubc9 or with an empty control vector (CTL) were induced with zinc sulfate for 16 h, and electrophoretically separated proteins (indicated on the left) were analyzed by immunoblotting as in B and C.

Most p19Arf in cells resides within high-molecular-mass complexes within the nucleolus (2), where many additional Arf-interacting proteins reside (40). Immunofluorescence analyses performed with antibodies to p19Arf and SUMO-1 revealed that although most of the SUMO-1 signal was dispersed throughout the nucleoplasm in WT MEFs (data not shown) or in NIH 3T3 cells that lack the Arf gene, induction and nucleolar accumulation of p19Arf in MT-Arf cells localized SUMO-1-containing molecules to nucleoli (Fig. 2C).

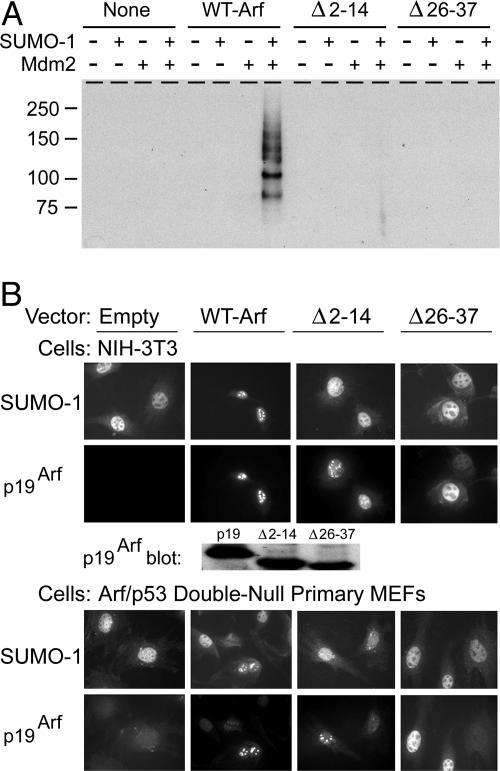

Arf Mutants Defective for Sumoylation. We next studied the effects of two previously characterized hypomorphic p19Arf mutants. The first deletion mutant (Δ2–14) lacks the 13 residues downstream of the initiator methionine, is defective in binding to both Mdm2 and NPM, and is degraded more rapidly than WT p19Arf (36, 37). The second deletion mutant (Δ26–37) is able to interact with both Mdm2 and NPM in vitro but is unable to enter the nucleolus efficiently, although its stability is not highly compromised (36, 37). When introduced by transient transfection into 293T cells, these two Arf mutants were defective in inducing sumoylation of Mdm2 (Fig. 3A) and NPM (data not shown). Immunofluorescence studies using retroviral vector-infected NIH 3T3 cells confirmed that Arf (Δ26–37) was excluded from nucleoli, whereas Arf (Δ2–14), although still accumulating there, did not efficiently localize SUMO-1-conjugated molecules to nucleoli (Fig. 3B Top), even though the different Arf proteins were expressed at nearly equivalent levels (see p19Arf blot). We obtained similar results with primary MEFs lacking both Arf and p53 (Fig. 3B Bottom). Taken together, we conclude that (i) p19Arf induces sumoylation of proteins with which it physically interacts, (ii) Arf induces widespread sumoylation of nucleolar proteins, and (iii) Arf-induced sumoylation does not require p53 or Mdm2.

Fig. 3.

Two Arf mutants do not induce sumoylation. (A) Lysates of 293T cells cotransfected with the indicated combinations of vectors encoding different Arf protein variants (see text), SUMO-1, and Mdm2 were affinity-purified on nickel beads, separated on denaturing gels, and immunoblotted with antibody to Mdm2. (B) Cells infected with vectors encoding SUMO-1 and a control vector (empty), WT Arf, Arf Δ2–14, or Arf Δ26–37 (indicated at the top) were immunostained with antibodies to SUMO-1 or p19Arf (indicated at the left). Similar levels of WT and mutant Arf proteins were expressed as documented by a representative immunoblot.

Inhibition of Sumoylation Does Not Overtly Affect Arf-Mdm2-p53 Signaling. The avian adenovirus CELO encodes Gam1, a protein that interferes with the activity of the SUMO-1 activating enzyme, leads to the degradation of Ubc9, and inhibits the SUMO pathway in mammalian cells (38). Given the ability of p19Arf to stimulate sumoylation of selected proteins with which it interacts, we reasoned that Gam1 would function “upstream” of p19Arf to block its effects on protein sumoylation. Myc-tagged versions of WT Gam1 and a defective Gam1 mutant used as a control were expressed in 293T cells (Fig. 4A). Expression of Gam1 in the presence or absence of plasmids encoding His6-SUMO1, p19Arf, and Mdm2 demonstrated that Gam1, but not the defective Gam1 mutant, blocked sumoylation of Mdm2 (Fig. 4A Upper). Sumoylation of the endogenous NPM protein also was triggered by p19Arf, and again, Gam1, but not the Gam1 mutant, inhibited NPM sumoylation (Fig. 4A Lower). Only WT Gam1 reduced Ubc9 expression, even though it and the mutant form were expressed at equivalent levels (data not shown and Fig. 4C).

Because Mdm2 is sumoylated in an Arf-dependent manner, these findings raised the question of whether Mdm2 sumoylation would alter the p53 transcriptional response in any significant way. To test this, we used retroviral vectors to introduce Gam1 or the defective Gam1 mutant into MT-Arf cells together with His6-SUMO-1 and then induced Arf 3 days later. Although Gam1, but not the Gam1 mutant, blocked Mdm2 sumoylation, p19Arf, p53, Mdm2, and p21Cip1 were induced to equivalent levels whether Gam1 was expressed or not (Fig. 4B). Gam1 and the defective Gam1 mutant were expressed at comparable levels (Fig. 4 B and C), but only WT Gam1 reduced the levels of Ubc9 (Fig. 4C). As an independent approach, we used short hairpin RNA to limit Ubc9 expression and Mdm2 sumoylation, and again observed no effects on the ability of p19Arf to trigger the expression of p53-responsive genes (Fig. 4D). Hence, Arf-induced sumoylation seems not to be a major regulator of this aspect of the p53 transcriptional program.

Discussion

Enforced expression of p19Arf can arrest proliferation of p53-null (6) and p53/Mdm2-null cells (8). Conversely, Arf inactivation in these cell types further accelerates the rate of their proliferation in culture and predisposes “triple knockout” mice lacking Arf, Mdm2, and p53 to much more rapid and extensive tumorigenesis than that in mice lacking Mdm2 and p53 (8). The demonstration that human and mouse Arf proteins induce sumoylation provides a tantalizing clue as to how p19Arf may mediate biological effects in the absence of Mdm2 and p53. Both human p14ARF and mouse p19Arf promote accumulation of SUMO-1-conjugated (H)Mdm2 (19, 20), and sequences in the Arf proteins that are required for their direct and efficient physical association with Mdm2 (residues 2–14 in p19Arf) also are necessary for sumoylation. The same residues mediate efficient binding to the abundant nucleolar protein NPM (37, 40), which also was not sumoylated in response to Arf Δ2–14. Arf induction did not trigger sumoylation of several other proteins to which p19Arf does not strongly bind, arguing for additional specificity. Overexpression of Arf can change the subcellular localization of Mdm2 by promoting its import into the nucleolus where most p19Arf protein accumulates (36). In MT-Arf cells, the accumulation of induced p19Arf in nucleoli resulted in an extensive redistribution of sumoylated molecules from the nucleoplasm to nucleoli. An Arf mutant lacking residues 26–37, which does not efficiently enter nucleoli but still binds to Mdm2 with high affinity, also was defective in Mdm2 sumoylation. Taken together, these results argue that Arf-induced sumoylation depends on a direct physical interaction of p19Arf with either Mdm2 or NPM, and that this process may preferentially occur in the nucleolus where the major pool of p19Arf resides.

Expression of Arf proteins protects p53 from Mdm2-mediated ubiquitination, leading to p53 stabilization and induction of p53-responsive genes. Introduction of the adenoviral Gam1 protein or of short hairpin RNA to Ubc9 into cells blocked the SUMO pathway and inhibited Arf-induced sumoylation of Mdm2 without affecting p53 stabilization or the induction of both Mdm2 and p21Cip1. Thus, sumoylation appears not to be required for activation of the p53 transcriptional program per se, although more subtle effects on gene expression cannot be precluded. Enforced expression of p19Arf in cells lacking functional p53 increased the sumoylation of endogenous target proteins such as NPM. In turn, Gam1-mediated inhibition of NPM sumoylation had no effect on Arf's ability to retard rRNA processing (M. Sugimoto, K.T., and C.J.S., unpublished data). Hence, putative biological effects of Arf-induced sumoylation must lie elsewhere. Because overexpression of Gam1 or interference with Ubc9 expression further inhibits cell-cycle progression and is ultimately toxic to cells, we were unable to determine whether p19Arf-mediated sumoylation contributes in any way to Arf's effects on proliferation.

Human p14ARF has been reported to bind to several other proteins, including the WRN helicase, E2F1, c-Myc, topoisomerase I, HIF-1α, the adenovirus E1A-regulated transcriptional repressor p120E4F, and the HIV Tat-binding protein 1 (12, 13, 16, 17, 21, 22, 41). With the exception of c-Myc, which has not been tested, these proteins can undergo sumoylation when cotransfected with p14ARF and His6-SUMO-1 into human tumor cell lines. Like ARF, transfected WRN predominantly localized to nucleoli, but unlike the observed increase in overall nucleolar SUMO-1 immunofluorescence signals observed after p19Arf induction in our studies, p14ARF overexpression redistributed the ectopically expressed WRN protein from nucleoli to other sites within the nucleus (21). This result suggests that p14ARF-induced sumoylation might regulate nucleolar export, rather than import, of certain modified target proteins, although an important caveat is that the achieved levels of p14ARF and WRN expression eclipsed those of normal cells.

Is Arf a component of a SUMO E3 ligase? For example, might p19Arf serve as a specificity factor that bridges Ubc9-containing complexes to Arf-binding proteins? Woods et al. (21) stated that robust SUMO-1 conjugation of WRN could be observed in an in vitro reconstitution reaction in the presence of the SUMO E1/E2 enzymes but indicated that addition of recombinant p14ARF had no effect, even at limiting concentrations of Ubc9 with which tagged p14ARF can coprecipitate when overexpressed (22). An inability to stimulate sumoylation in vitro with recombinant p14ARF may not be surprising given the fact that Arf proteins are highly basic, bind nonspecifically to many acidic proteins and to nucleic acids, and normally reside in “buffered” higher-molecular-mass complexes in living cells (40). Hence, a better approach might be to test native Arf protein complexes purified from mammalian cells for an associated E3 ligase activity when combined in vitro with the other purified components of the SUMO cascade. Because Gam1 interferes with SUMO E1 activity and lowers Ubc9 levels, p19Arf must function “downstream.” If p19Arf is a selectivity component of a SUMO E3 ligase, it should bind both to Ubc9 and to its protein targets. Thus, p19Arf would have no effect in modifying other nonassociating proteins such as RanGAP1 or HDACs, which are bona fide SUMO substrates but were unaffected by p19Arf in our studies. Such a model would also demand that any direct binding of p19Arf to target proteins such as Mdm2 or NPM on the one hand and to Ubc9 on the other would have to be mediated through separate binding motifs within Arf, a prediction that has not so far been rigorously tested. A conceptual complication is that the domains of mouse p19Arf that are required for Mdm2 binding reside completely within sequences encoded by exon 1 (36), whereas those in human p14ARF are encoded by segments within exons 1 and 2 (42). Alternatively, Arf-induced sumoylation might be mediated through an ability to inhibit a deconjugating SUMO protease. However, transfection of one such enzyme, SENP1, into cells prevented the sumoylation of Hdm2 even when cotransfected with p14ARF, implying that Arf does not inhibit the protease activity of SENP1 (20).

Mammalian transcription factors that control cell proliferation are sumoylated (23–25, 32), and the effects of Gam1 on sumoylation can increase the activity of several such factors (38). Gam1 reduces the sumoylation of HDAC1 without affecting its enzymatic activity (43), but HDAC1 recruitment to promoters is enhanced when histone H4 is sumoylated (44). Sumoylation of Elk-1 recruits suppressive HDAC activity to Elk-1-regulated promoters (45), and conversely, the SENP1 protease enhances androgen receptor-dependent transcription by desumoylation of HDAC1 (46). Observations that Arf binds to and/or negatively regulates transcription factors such as E2F-1 (12, 13), Myc (16, 17), and NFκB (18) raise the question of whether Arf-mediated sumoylation may account for any of these effects. In proteome-wide surveys in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, many functional categories of SUMO-modified proteins were detected, including those involved in transcription and chromatin remodeling, DNA repair, ribosome synthesis, metabolism, and various stress responses (47–50). It is, therefore, conceivable that sumoylation triggered by mouse p19Arf in S. cerevisiae might lead to phenotypes that would allow a further dissection of this process in a simple eukaryote that is highly amenable to genetic manipulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Masataka Sugimoto for performing rRNA processing experiments and all members of the Sherr–Roussel laboratory for critical advice and suggestions. This work was partially supported by Cancer Center Support Grant CA-21765 and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

Author contributions: C.J.S. designed research; K.T. performed research; K.T. and S.C. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; K.T., S.C., and C.J.S. analyzed data; and C.J.S. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: HDAC, histone deacetylase; NPM, nucleophosmin; WRN, Werner helicase; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; MSCV, murine stem cell virus; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier; MT, metallothionein promoter; MEF, mouse embryo fibroblast.

References

- 1.Serrano, M., Hannon, G. J. & Beach, D. (1993) Nature 366, 704–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quelle, D. E., Zindy, F., Ashmun, R. A. & Sherr, C. J. (1995) Cell 83, 993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamijo, T., Zindy, F., Roussel, M. F., Quelle, D. E., Downing, J. R., Ashmun, R. A., Grosveld, G. & Sherr, C. J. (1997) Cell 91, 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowe, S. W. & Sherr, C. J. (2003) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13, 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamijo, T., van de Kamp, E., Chong, M. J., Zindy, F., Diehl, A. J., Sherr, C. J. & McKinnon, P. (1999) Cancer Res. 59, 2464–2469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carnero, A., Hudson, J. D., Price, C. M. & Beach, D. H. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eischen, C. M., Weber, J. D., Roussel, M. F., Sherr, C. J. & Cleveland, J. L. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 2658–2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber, J. D., Jeffers, J. R., Rehg, J. E., Randle, D. H., Lozano, G., Roussel, M. F., Sherr, C. J. & Zambetti, G. P. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 2358–2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugimoto, M., Kuo, M. L., Roussel, M. F. & Sherr, C. J. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayrault, O., Andrique, L., Larsen, C. J. & Seite, P. (2004) Oncogene 23, 8097–8104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo, M.-L., Duncavage, E. J., Mathew, R., den Besten, W., Pie, D., Naeve, D., Yamamoto, T., Cheng, C., Sherr, C. J. & Roussel, M. F. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 1046–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martelli, F., Hamilton, T., Silver, D. P., Sharpless, N. E., Bardeesy, N., Rokas, M., DePinho, R. A., Livingston, D. M. & Grossman, S. R. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 4455–4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eymin, B., Karayan, L., Seite, P., Brambilla, C., Brambilla, E., Larsen, C. J. & Gazzeri, S. (2001) Oncogene 20, 1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Datta, A., Nag, A. & Raychaudhuri, P. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 8398–8408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aslanian, A., Iaquinta, P. J., Verona, R. & Lees, J. A. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 1413–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi, Y., Gregory, M. A., Li, Z., Brousal, J. P., West, K. & Hann, S. R. (2004) Nature 431, 712–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datta, A., Nag, A., Pan, W., Hay, N., Gartel, A. L., Colamonici, O., Mori, Y. & Raychaudhuri, P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36698–36707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocha, S., Campbell, K. J. & Perkins, N. D. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xirodimas, D. P., Chisholm, J., Desterro, J. M. S., Lane, D. P. & Hay, R. T. (2002) FEBS Lett. 528, 207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen, L. & Chen, J. (2003) Oncogene 22, 5348–5357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woods, Y. L., Xirodimas, D. P., Prescott, A. R., Sparks, A., Lane, D. P. & Saville, M. K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50157–50166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rizos, H., Woodruff, S. & Kelford, R. F. (2005) Cell Cycle 4, e39–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melchior, F. (2000) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 591–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, E. S. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 355–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilgarth, R. S., Murphy, L. A., Skaggs, H. S., Wilkerson, D. C., Xing, H. & Sarge, K. D. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 53899–53902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson, E. S. & Gupta, A. A. (2001) Cell 106, 735–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sachdev, S., Bruhn, L., Sieber, H., Pichler, A., Melchior, F. & Grosschedl, R. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 3088–3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotaja, N., Karvonen, U., Janne, O. A. & Palvimo, J. J. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5222–5234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hochstrasser, M. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, E153–E157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hay, R. T. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 332–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melchior, F., Schergaut, M. & Pichler, A. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gill, G. (2003) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13, 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bachant, J., Alcasabas, A., Blat, Y., Kleckner, N. & Elledge, S. J. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 1169–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zindy, F., Eischen, C. M., Randle, D. H., Kamijo, T., Cleveland, J. L., Sherr, C. J. & Roussel, M. F. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2424–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dang, J., Kuo, M.-L., Eischen, C. M., Stepanova, L., Sherr, C. J. & Roussel, M. F. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 1222–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber, J. D., Taylor, L. J., Roussel, M. F., Sherr, C. J. & Bar-Sagi, D. (1999) Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuo, M.-L., den Besten, W., Bertwistle, D., Roussel, M. F. & Sherr, C. J. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 1862–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boggio, R., Colombo, R., Hay, R. T., Draetta, G. F. & Chiocca, S. (2004) Mol. Cell 16, 549–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertwistle, D., Zindy, F., Sherr, C. J. & Roussel, M. F. (2004) Hybrid. Hybridomics 23, 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertwistle, D., Sugimoto, M. & Sherr, C. J. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 985–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karayan, L., Riou, J. F., Seite, P., Migeon, J., Cantereau, A. & Larsen, C. J. (2001) Oncogene 20, 836–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, Y., Xiong, Y. & Yarbrough, W. G. (1998) Cell 92, 725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colombo, R., Boggio, R., Seiser, C., Draetta, G. F. & Chiocca, S. (2002) EMBO Rep. 3, 1062–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiio, Y. & Eisenman, R. N. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13118–13120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang, S. H. & Sharrocks, A. D. (2004) Mol. Cell 13, 611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng, J., Wang, D., Wang, Z. & Yeh, E. T. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 6021–6028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou, W., Ryan, J. J. & Zhou, H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32262–32268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Panse, V. G., Hardeland, U., Werner, T., Kuster, B. & Hurt, E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 41346–41351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hannich, J. T., Lewis, A., Kroetz, M. B., Li, S.-J., Heide, H., Emili, A. & Hochstrasser, M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4102–4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wykoff, D. D. & O'Shea, E. K. (2005) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]