Abstract

Lactones are cyclic esters with extensive applications in materials science, medicinal chemistry, and the food and perfume industries. Nature’s strategy for synthesis of the many lactones found in natural products always relies on a single type of retrosynthetic strategy, a C–O bond disconnection. Here we describe a set of laboratory-engineered enzymes that use a new-to-nature C–C bond-forming strategy to assemble diverse lactone structures. These engineered ‘carbene transferases’ catalyze intramolecular carbene insertions into benzylic or allylic C–H bonds, which allows for the synthesis of lactones with different ring sizes and ring scaffolds from simple starting materials. Starting from a serine-ligated cytochrome P450 variant previously engineered for other carbene transfer activities, directed evolution generated variant P411-LAS-5247, which exhibits high activity for constructing 5-membered ε-lactone, lactam, and cyclic ketone products (up to 5600 total turnovers (TTN) and >99% enantiomeric excess (e.e.)). Further engineering led to variants P411-LAS-5249 and P411-LAS-5264, which deliver 6-membered δ-lactones and 7-membered ε-lactones, respectively, overcoming the thermodynamically unfavorable ring strain associated with these products compared to the γ-lactones. This new carbene-transfer activity was further extended to the synthesis of complex lactone scaffolds based on fused, bridged, and spiro rings. The enzymatic platform developed here complements natural biosynthetic strategies for lactone assembly and expands the structural diversity of lactones accessible through C–H functionalization.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Lactones are ubiquitous in natural products1 and active pharmaceutical ingredients2 and serve as essential building blocks for fine chemicals and polyesters.1, 3–4 Intramolecular carbene C–H insertion, catalyzed by transition metals such as rhodium, iridium, and copper,5–9 has received significant attention for the synthesis of lactones. Based on a C–C bond disconnection strategy, this approach is simple, efficient, and exhibits high atom economy.10 Due to the thermodynamic stability of the intermediates and products, however, intramolecular C–H insertion has been mainly limited to the synthesis of five-membered γ-lactones (Figure 1A).5–9, 11–12 While a few catalytic systems have demonstrated the synthesis of four-membered β-lactones through favorable five-membered transition states, examples of lactones with different ring sizes are limited, and reactions with these molecules often proceed with poor regio- or enantio-selectivity and thus result in mixtures of lactone products.12–13 A general method for synthesis of chiral lactones with diverse ring sizes and structures using an intramolecular carbene C–H insertion strategy has yet to be demonstrated.

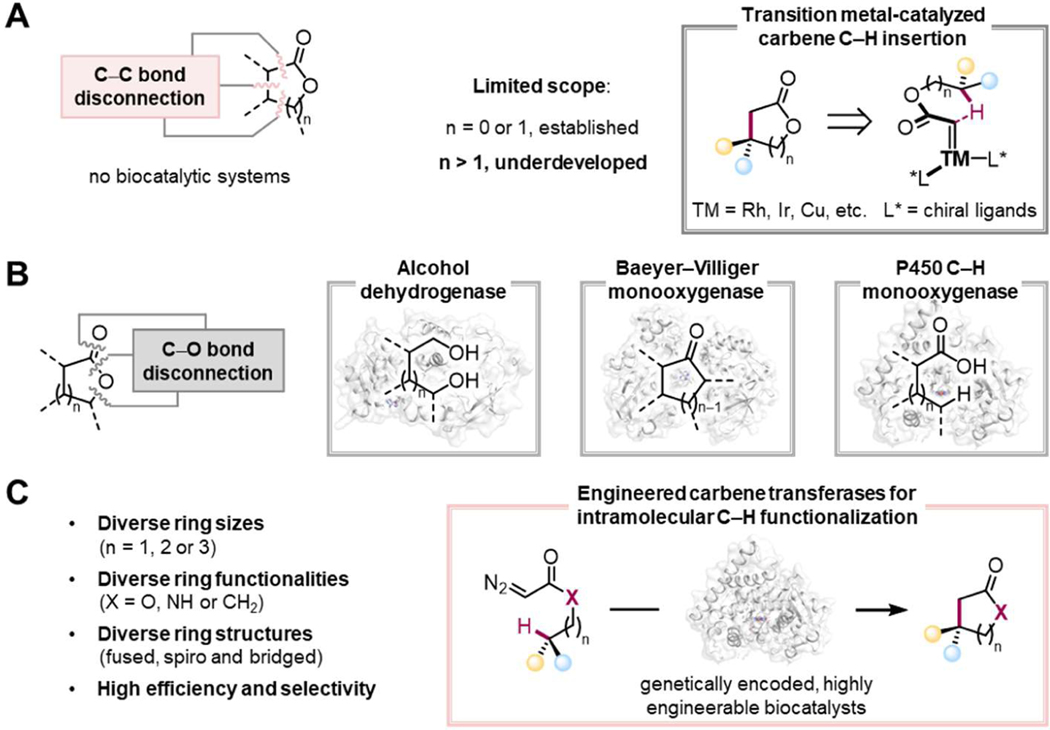

Figure 1.

(A) Small-molecule transition-metal-catalyzed intramolecular C–H insertion, which typically produces five-membered lactones. (B) Nature employs C‒O disconnections for the construction of lactones. (C) This work: a biocatalytic platform enables access to diverse lactones via intramolecular carbene transfer reactions. R, organic groups; TM, transition metal.

Nature does not employ C–C bond disconnection strategies to biosynthesize lactones; instead, C–O bond disconnection strategies are universally used, including Baeyer–Villiger oxidation,14 oxidative lactonization of diols,15 C–H hydroxylation of fatty acids followed by lactonization,16 and reductive cyclization of keto-esters (Figure 1B).17 Though these routes produce lactones with diverse structures and ring sizes, the C–O bond disconnection is a limitation that restricts retrosynthetic versatility and broader synthetic applications. This limitation inspired us to add the chemists’ C–C bond disconnection approach to nature’s biocatalytic repertoire by engineering enzymes to perform intramolecular lactone cyclization via C–H insertion and using the macromolecular enzyme scaffold to impart desired regio- and enantioselectivities unavailable to small-molecule catalysts.

Over the past decade, various hemeproteins have been repurposed to perform abiological carbene- and nitrene-transfer reactions.18–22 Enzymes containing a heme prosthetic group have been engineered to activate a carbene or nitrene precursor and subsequently control the highly reactive carbene/nitrene intermediate to target specific bonds, including C–H, heteroatom– H, and unsaturated C–C bonds. Motivated by these precedents, we aimed to develop a biocatalytic intramolecular carbene C– H insertion strategy for lactone synthesis (Figure 1C). Several challenges must be overcome to realize this goal. First, the enzymes must bind the carbene intermediates and orient them for carbene insertion into desired C–H bonds. Second, the enzymes need to stabilize intermediates with varied ring strains to give lactone products of different sizes. Third, because the stereoconfiguration of the reaction intermediates is influenced by the size of the ring, the enzymes must precisely control the stereoconfiguration of different ring intermediates to achieve stereoselectivity. We proposed that such an enzymatic platform could be generated by directed evolution, and with further evolution, the enzymes could accept a greater diversity of substrates to synthesize other cyclic structures, such as lactams and cyclic ketones important in a broad range of pharmaceutical intermediates.

Results and discussion

Enzymatic γ-lactone synthesis: initial screening, directed evolution, and substrate scope.

We initiated this investigation by focusing on the intramolecular carbene C–H insertion reaction of diazo compound 1a to form γ-lactone 2a, shown in Figure 2. γ-Lactones are the preferred products of intramolecular carbene C–H insertion with small-molecule transition metal catalysts.23–24 We proposed to start with a biocatalytic system for γ-lactones and then move on to more challenging targets. To this end, we surveyed an in-house collection of over one hundred cytochrome P450 and P411 (P450 with an axial serine ligand) variants, previously engineered for carbene and nitrene transfer, in the form of whole Escherichia coli cells. Most of the hemeproteins exhibited no measurable activity for the desired carbene C–H insertion transformation; the diazo substrate 1a was nonetheless fully consumed to give a mixture of unwanted products from carbene O–H insertion with water, carbene dimerization, and cycloaddition between carbene dimers and the diazo substrate. However, P411 variant C10, known for its promiscuous activities in other carbene-transfer reactions such as internal alkyne cyclopropenation25 and lactone-carbene C–H insertion,26 was effective in producing the γ-lactone product 2a (7% yield, Figure 2A). We thus used C10 as the starting template for engineering a set of lactone synthase enzymes (LAS).

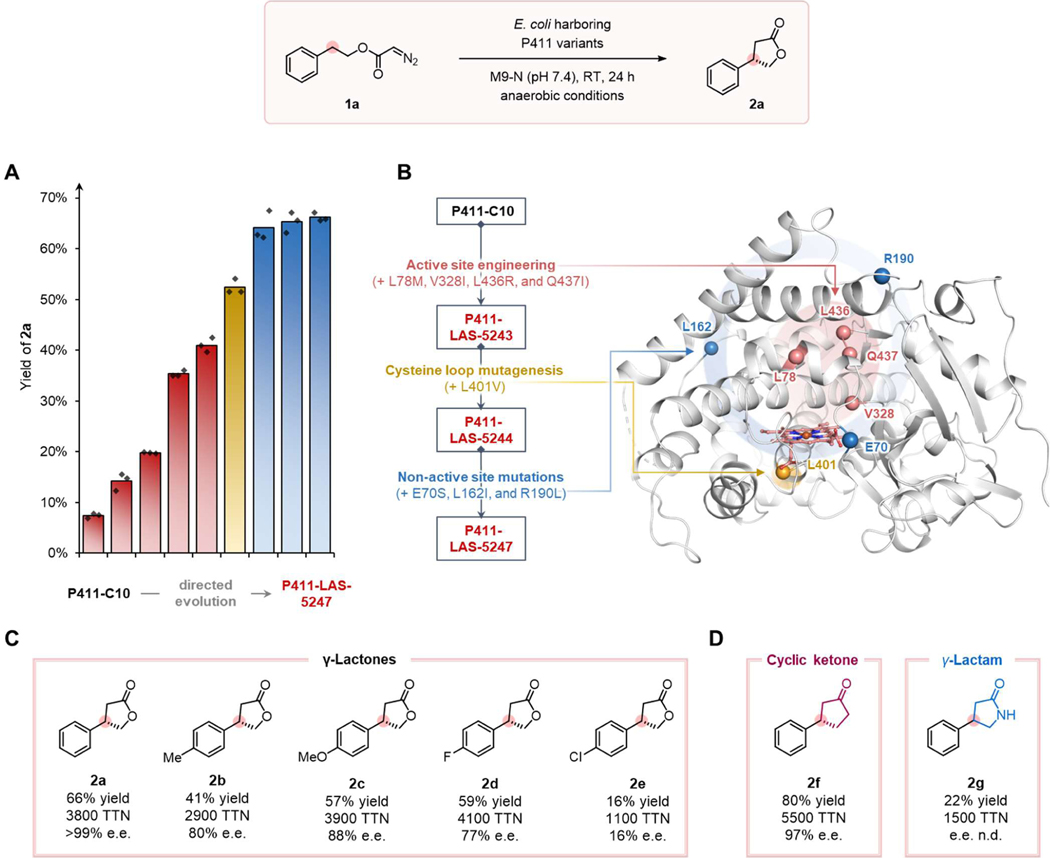

Figure 2. Directed evolution and substrate-scope study for γ-lactone synthesis.

Reaction conditions: 2.5 mM 1, E. coli whole cells harboring P411 variants (OD600 = 2.5) in M9-N aqueous buffer (pH 7.4), 1.25% v/v acetonitrile (co-solvent), room temperature, anaerobic conditions, 24 h. (A) Directed evolution culminating in P411-LAS-5247. Reactions were performed in triplicate (n = 3). Yields reported are based on calibrated HPLC traces and are the means of three independent experiments. (B) Evolutionary trajectory of P411-LAS-5247 from P411-C10 and locations of beneficial mutations in protein structure based on a close variant E10 (PDB ID: 5UCW). (C) Scope of γ-lactones using P411-LAS-5247. (D) Synthesis of a 5-membered cyclic ketone and a γ-lactam using P411-LAS-5247.

To enhance catalytic efficiency, we performed directed evolution by targeting active-site residues for site-saturation mutagenesis (SSM). Sequential rounds of mutagenesis and screening identified variant P411-LAS-5243 with four beneficial mutations (Q437I, V328I, L78M, and L436R) that collectively increase TTN fivefold, providing 2a in 41% yield (Figures 2A and 2B). Site-saturation mutagenesis of the cysteine loop uncovered mutation L401V in variant P411-LAS-5244, which improved the yield to 52% (Figures 2A and 2B). When exhaustive examination of other active-site residues did not result in further activity enhancement, we selected several non-active-site residues, known to contribute to P450’s dynamics with native substrates bound, for saturation mutagenesis.27–28 Library screening led to three additional beneficial mutations (L162I, R190L, and E70S) in final variant P411-LAS-5247, with 3850 total turnovers and 66% yield for product 2a (Figures 2A and 2B). The evolved enzyme displayed near-perfect stereo-control with >99% enantiopurity for product 2a.

We investigated the activity of P411-LAS-5247 against an array of diazo compounds for the synthesis of γ-lactones via intramolecular carbene insertion into benzylic C–H bonds (Figure 1C). A variety of γ-lactones were synthesized with excellent TTNs and enantioselectivities (up to 3800 TTN and >99% e.e., Figure 2C). Substrates bearing diverse substituents on the phenyl ring, electron-neutral (1a and 1b, Figure 2), -rich (1c, Figure 2), or -deficient (1d and 1e, Figure 2), are all compatible with this biotransformation. Notably, 2e can serve as a synthetic intermediate for the antispasmodic drug baclofen.10 In addition to diazoacetate substrates, we also tested diazoketone 1f and diazoamide 1g, which upon cyclization form non-lactone products. These substrates proceeded smoothly with P411-LAS-5247 to furnish cyclic ketone 2f and γ-lactam 2g with excellent TTNs (up to 5500 TTN, Figure 2D). It is worth noting that the lactam product was obtained without any additional protection-deprotection steps on the nitrogen, underscoring the ability of the enzyme to work with substrates having active functional groups. The absolute stereochemistry for enzymatic product 2c was assigned as S by comparing the elution order of the two enantiomers with a literature report29 (see SI for details). The other γ-lactones 2 were assigned by analogy.

Expansion of the enzymatic platform for δ- and ε-lactone synthesis.

With the biocatalytic C–H insertion strategy established for γ-lactone synthesis, we sought to extend it to δ-lactones. We chose to test diazo 3b, which has one additional carbon compared to substrate 1a, toward the synthesis of 4b (Figure 3C). Conventional dirhodium catalysts catalyze the conversion of 3 into γ-lactones as the sole products through carbene insertion into homobenzylic C–H bonds.30–31 We were thus curious whether the enzymes would exhibit different regioselectivity for C–H insertion. Screening the P411-LAS-5247 lineage against substrate 3b, we found that P411-LAS-5244 exhibited high efficiency for the formation of δ-lactone 4b as the exclusive C–H insertion product (48% yield, 3600 TTN, and 90% e.e., Figure 3C). These results show that this biocatalytic platform features a different site preference from the rhodium system – the hemeprotein carbene transferases discriminate C–H bonds based on bond strength, while the geometric distance of the C–H bonds to the carbene center plays a more important role in the regio-selectivity of rhodium catalysts.

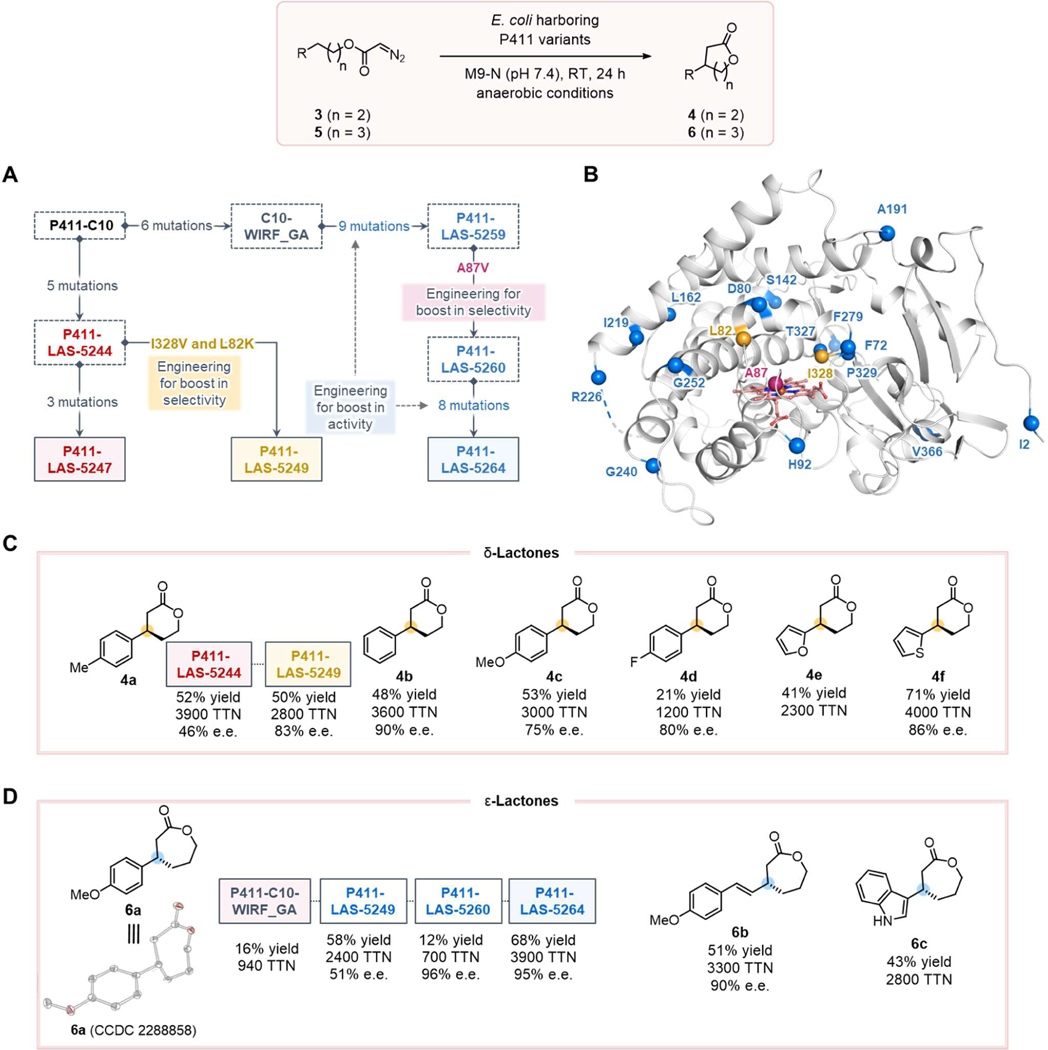

Figure 3. Directed evolution and substrate-scope study for δ- and ε-lactone synthesis.

Reaction conditions: 2.5 mM 3 or 5, E. coli whole cells harboring P411 variants (OD600 = 2.5) in M9-N aqueous buffer (pH 7.4), 1.25% v/v acetonitrile (co-solvent), room temperature, anaerobic conditions, 24 h. Reactions were performed in triplicate (n = 3). Yields reported are based on calibrated HPLC traces and are the means of three independent experiments. (A) Evolutionary trajectories of lactone synthases P411-LAS-5247, P411-LAS-5249, and P411-LAS-5264 from P411-C10. (B) Locations of beneficial mutations in the protein structure based on a close variant E10 (PDB ID: 5UCW); (C) Scope of δ-lactones using P411-LAS-5249. (D) Scope of ε-lactones using P411-LAS-5264. aP411-LAS-5244 was used. bP411-LAS-5249 was used.

Having identified P411-LAS-5244 as a potent enzyme for δ-lactone formation, we further investigated the substrate scope. When challenged with other substrates bearing substituents on the phenyl ring, P411-LAS-5244 demonstrated high activity, but its enantioselectivity was greatly diminished (e.g., 46% e.e. for product 4a, Figure 3C). We elected to continue directed evolution of this highly active variant, focusing on improving enantioselectivity. Two active-site mutations, I328V and L82K, were identified that boosted enantioselectivity to 83% e.e. for 4a while maintaining activity. The resulting variant, P411-LAS-5249, was revealed to deliver δ-lactone products bearing diverse functional groups with high efficiency and enantioselectivities (up to 2800 TTN, and 86% e.e., Figure 3C). The absolute stereochemistry for enzymatic product 4b was assigned as R by comparing the elution order of the two enantiomers with a literature report32 (see SI for details). The other δ-lactones 4 were assigned by analogy.

By recognizing the site preference in this enzymatic C–H insertion system, we then asked whether 7-membered ε-lactones could be accessed with an appropriate diazo substrate (e.g., the transformation of 5a into 6a, Figure 3D). 7-Membered lactones are generally much more difficult to assemble compared to 5- or 6-membered lactones due to the higher enthalpy and entropy costs of cyclization.23–24 The P411-LAS-5247 and P411-LAS-5249 lineages, unfortunately, only displayed minimal or no activity toward the formation of ε-lactone 6a. We therefore screened a large collection of enzyme variants, all engineered from the initial C10 parent, for ε-lactone formation from 5a. A variant previously evolved for internal alkyne cyclopropenation, C10-WIRF_GA (Figure 3A, and SI, Table S5),25 exhibited promising activity (16% yield, 940 TTN, Figure 3D).

Directed evolution of C10-WIRF_GA introduced nine new mutations and yielded an efficient variant, P411-LAS-5259, for the synthesis of ε-lactone 6a (58% yield and 2400 TTN, Figures 3A and 3D), but with unsatisfactory enantioselectivity (51% e.e.). A single amino acid mutation at residue 87 dramatically boosted the selectivity to 96% e.e. (Figures 3A and 3D), which highlights the crucial role of this residue in controlling the orientation of carbene intermediates in the protein active site.22, 33–34 This mutation caused the activity to drop by nearly fivefold, however (Figure 3D). Further evolution was performed to recover the activity (Figures 3A and 3D), leading to a new variant P411-LAS-5264 with high activity and enantioselectivity toward the synthesis of 6a (68% yield, 3900 TTN, and 95% e.e., Figures 3A and 3D). Beyond model substrate 5a, P411-LAS-5264 also accepts structurally diverse and challenging substrates, such as 5b and 5c, for carbene insertion at an allylic site or a benzylic site of an unprotected indole, affording the corresponding ε-lactone products 6b and 6c with up to 3300 TTN and 90% e.e. (Figure 3D). The absolute stereochemistry for enzymatic product 6a was assigned as S through X-ray crystallography (SI, Figure S3). The other ε-lactone 6 were assigned by analogy.

Complex lactone synthesis through enzymatic carbene C–H insertion.

We were also interested in the synthesis of more complex ring scaffolds. The large collection of P411 enzyme variants derived from C10 provides a biocatalyst pool with which to quickly search for variants capable of catalyzing desired C–H insertions. Interestingly, when paired with different substrates, different enzymes displayed unique stereo- and regio-selectivities to afford lactone products with high structural complexity. For instance, variant P411-LAS-5265 (SI, Table S5) efficiently converted substrates 7a and 7b, derived from indane, into γ- and δ-lactones 8a and 8b in a fused ring scaffold (Figures 4A and 4B), which represents a C–H functionalization onto an existing ring with high activity and stereoselectivity. The reaction of 7a was scaled up and the product isolated to afford 69 mg of 7b with 76% yield, demonstrating that the synthesis of these complex rings is feasible at small scale. Racemic substrates 7c and 7d could be utilized by variants P411-LAS-5259 and P411-LAS-5257 (SI, Table S5), respectively, to target tertiary benzylic C–H bonds for carbene insertion and give the 6-membered spiro-lactone products, 8c and 8d, with up to 2500 TTN (Figures 4C and 4D).

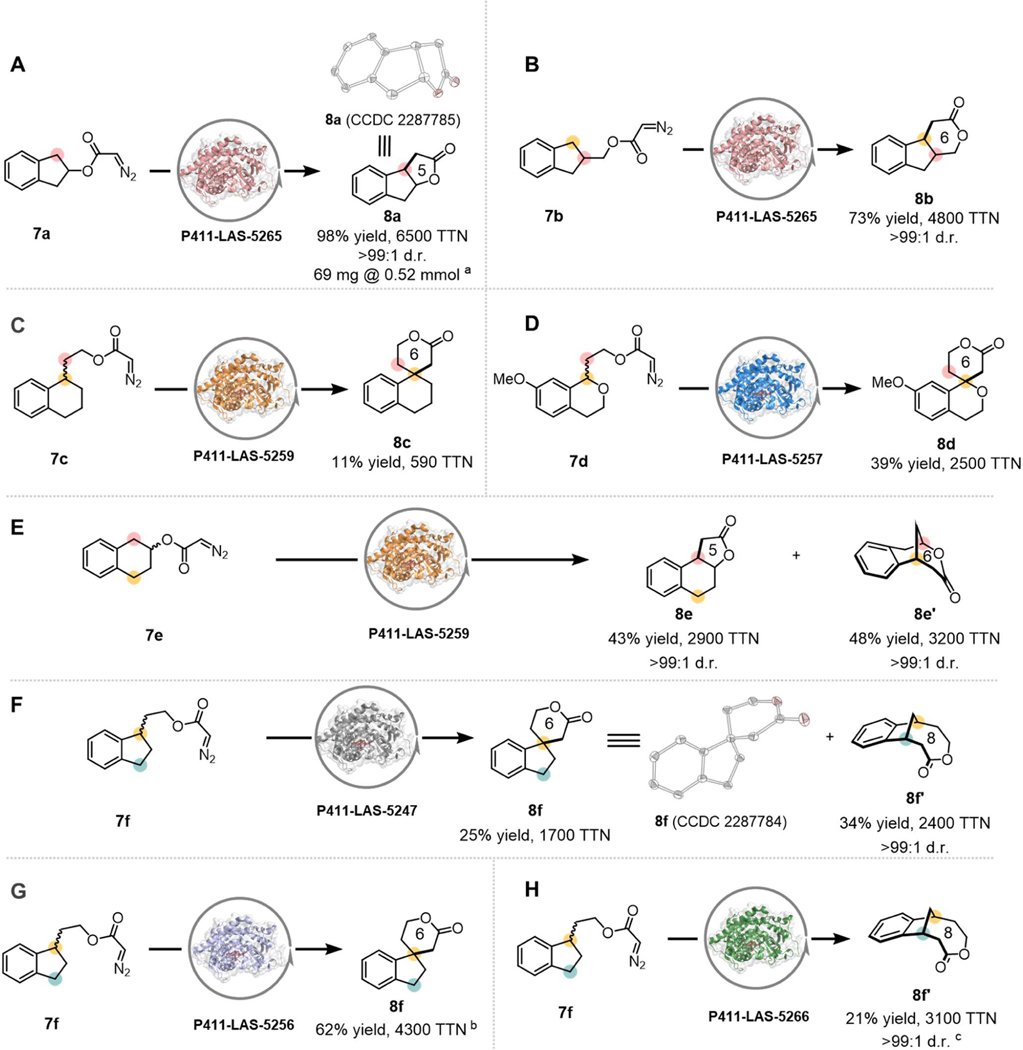

Figure 4. Enzymatic synthesis of complex lactones.

Reaction condition: 2.5 mM 3, E. coli whole cells harboring P411 variants (OD600 = 2.5) in M9-N aqueous buffer (pH 7.4), 1.25% v/v acetonitrile (co-solvent), room temperature, anaerobic conditions, 48 h. Yields reported are based on calibrated HPLC traces and are the means of three independent experiments. Enzymatic synthesis of (A and B) fused lactones, (C and D) spiro lactones, (E) fused- and bridged-lactones. (F) Parallel kinetic resolution toward 8f and 8f’catalyzed by P411-LAS-0003 from racemic diazo 7f. (G) Specific synthesis of spiro lactone 8f catalyzed by P411-LAS-0011 from racemic diazo 7f. (H) Specific synthesis of bridged-lactone 8f catalyzed by P411-LAS-0012 from racemic diazo 7f. a76% isolated yield. b8% yield, 530 TTN for product 8f’. c8f was not detected.

The biocatalysts could also discriminate the enantiomers of racemic substrates to give different product outcomes. Racemic substrate 7e, bearing two distinct sets of benzylic C–H bonds, was transformed by enzyme P411-LAS-5259 into two lactone products, a fused γ-lactone (8e) and a bridged δ-lactone (8e’) with high efficiency and selectivity (Figure 4E). Similarly, spiro δ-lactone (8f) and bridged 8-membered ζ-lactones (8f’) were observed as the products of racemic substrate 7f using enzyme P411-LAS-5247 (Figure 4F). Given that the enzyme’s active site is a chiral environment, we rationalized that the two enantiomers of the racemic substrates could bind in the active site with different orientations, which enables carbene insertion into geometrically distinct C–H bonds. This process represents a parallel kinetic resolution (PKR),35–36 which requires the catalyst to distinguish the substrate enantiomers and proceed with each enantiomer through different reaction pathways.37 To further verify the PKR process, we used the enantiopure starting materials of 7f for the biotransformation: P411-LAS-5247 specifically converted (R)-7f to spiro-lactone 8f and (S)-7f to bridged-lactone 8f’ with high TTNs and selectivities (SI, Figure S2), suggesting that P411-LAS-5247 can differentiate between the two enantiomers and perform a parallel kinetic resolution. We also identified another two variants, P411-LAS-5256 and P411-LAS-5266 (SI, Table S5), which converted racemic 7f to spiro-lactone 8f and bridged-lactone 8f’, respectively, exhibiting simple product specificity (Figures 4G and 4H). Notably, we found that P411-LAS-5256 converted both (R)- and (S)-7f into 8f, while P411-LAS-5266 selectively transformed only (S)-7f into 8f’ (SI, Figures S2).

Summary and conclusion

We have developed an enzymatic platform for asymmetric intramolecular carbene C–H transfer reactions, which enables straightforward construction of diverse lactone products with exceptional efficiency and selectivity. P450-derived carbene transferases were engineered for the selective functionalization of benzylic or allylic C–H bonds, allowing for the efficient assembly of an extensive array of benzylic and allylic lactones, including γ-, δ-, ε-lactones, as well as fused-, spiro-, and bridged-lactones. The new-to-nature C–C disconnection approach used by these carbene transferases serves as a valuable complement to the existing biotransformations based on C–O disconnections used by natural enzymes for lactone biosynthesis. In addition, many products demonstrated here, such as δ-, ε-, and more complex lactones, as well as unprotected lactams and indoles, have proven to be challenging targets for synthetic transition metal catalysts, but are now readily accessible using this biocatalytic strategy. This enzymatic platform enriches the disconnection strategies for biocatalytic lactone assembly while expanding the structural diversity of lactones accessible to synthetic chemistry. We anticipate the potential of hemeprotein carbene transferases will be further developed to access even broader classes of cyclic compounds, including lactones, lactams, and others, with applications in synthetic chemistry and drug discovery.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation Division of Molecular and Cellular Biosciences (MCB-2016137 to F.H.A). D.J.W. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1745301). R.M. acknowledges support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) Early Mobility Postdoctoral Fellowship (P2ELP2_195118). K.M.S. acknowledges support from NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (1F32GM145123-01A1). Y.Z. acknowledges support from the College of Chemistry at Nankai University. K.C. acknowledges support from the Resnick Sustainability Institute at Caltech and Life Sciences Research Foundation. We thank Dr. Michael K. Takase and Lawrence M. Henling for assistance with X-ray crystallographic data collection and Dr. Scott C. Virgil for the maintenance of the Caltech Center for Catalysis and Chemical Synthesis (3CS). We thank Dr. Mona Shahgoli for mass spectrometry assistance and Dr. David VanderVelde for the maintenance of the Caltech NMR facility. We also thank Dr. Sabine Brinkmann-Chen for the helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Full experimental details along with descriptions of ancillary experiments, are available within the Article and its Supporting Information. Crystallographic data for the structures 6a, 8a and 8f reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under the deposition numbers CCDC 2288858, 2287785 and 2287784, respectively. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.

The supporting information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sartori SK; Diaz MAN; Diaz-Muñoz G. Lactones: Classification, Synthesis, Biological Activities, and Industrial Applications. Tetrahedron 2021, 84, 132001. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hur J; Jang J; Sim J. A Review of the Pharmacological Activities and Recent Synthetic Advances of gamma-Butyrolactones. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Delgove MAF; Elford MT; Bernaerts KV; Wildeman SMA Toward Upscaled Biocatalytic Preparation of Lactone Building Blocks for Polymer Applications. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018, 22, 803–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hollmann F; Kara S; Opperman DJ; Wang Y. Biocatalytic Synthesis of Lactones and Lactams. Asian J. Chem. 2018, 13, 3601–3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Doyle MP; Forbes DC Recent Advances in Asymmetric Catalytic Metal Carbene Transformations. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 911–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Davies HM; Manning JR Catalytic C–H Functionalization by Metal Carbenoid and Nitrenoid Insertion. Nature 2008, 451, 417–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Davies HML; Beckwith REJ Catalytic Enantioselective C–H Activation by Means of Metal-Carbenoid-Induced C–H Insertion. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2861–2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Santiago JV; Machado AH Enantioselective Carbenoid Insertion Into C(sp3)–H Bonds. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 882–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Doyle MP; Duffy R; Ratnikov M; Zhou L. Catalytic Carbene Insertion into C−H Bonds. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 704–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Doyle MP; Hu W. Enantioselective Carbon–Hydrogen Insertion is an Effective and Efficient Methodology for the Synthesis of (R)-(−)-Baclofen. Chirality 2002, 14, 169–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Doyle MP; Oeveren A. v.; Westrum LJ; Protopopova MN; Thomas W. Clayton J. Asymmetric Synthesis of Lactones with High Enantioselectivity by Intramolecular Carbon–Hydrogen Insertion Reactions of Alkyl Diazoacetates Catalyzed by Chiral Rhodium(II) Carboxamides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 8982–8984. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Doyle MP; Kalinin AV; Ene DG Chiral Catalyst Controlled Diastereoselection and Regioselection in Intramolecular Carbon-Hydrogen Insertion Reactions of Diazoacetates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 8837–8846. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Doyle MP; Protopopova MN Macrocyclic Lactones from Dirhodium(II)-Catalyzed Intramolecular Cyclopropanation and Carbon–Hydrogen Insertion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 7281–7282. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Fürst MJLJ; Gran-Scheuch A; Aalbers FS; Fraaije MW Baeyer–Villiger Monooxygenases: Tunable Oxidative Biocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 11207–11241. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Dong J; Fernández-Fueyo E; Hollmann F; Paul CE; Pesic M; Schmidt S; Wang Y; Younes S; Zhang W. Biocatalytic Oxidation Reactions: A Chemist’s Perspective. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 9238–9261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Manning J; Tavanti M; Porter JL; Kress N; De Visser SP; Turner NJ; Flitsch SL Regio- and Enantio-selective Chemoenzymatic C–H-Lactonization of Decanoic Acid to (S)-delta-Decalactone. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5668–5671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Borowiecki P; Telatycka N; Tataruch M; Żądło-Dobrowolska A; Reiter T; Schühle K; Heider J; Szaleniec M; Kroutil W. Biocatalytic Asymmetric Reduction of γ-Keto Esters to Access Optically Active γ-Aryl-γ-butyrolactones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 2012–2029. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Poulos TL Cytochrome P450 Flexibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 13121–13122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Brandenberg OF; Fasan R; Arnold FH Exploiting and Engineering Hemoproteins for Abiological Carbene and Nitrene Transfer Reactions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 47, 102–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kaur P; Tyagi V. Recent Advances in Iron-Catalyzed Chemical and Enzymatic Carbene-Transfer Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 877–905. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Yang Y; Arnold FH Navigating the Unnatural Reaction Space: Directed Evolution of Heme Proteins for Selective Carbene and Nitrene Transfer. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1209–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Chen K; Huang X; Kan SBJ; Zhang RK; Arnold FH Enzymatic Construction of Highly Strained Carbocycles. Science 2018, 360, 71–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Illuminati G; Mandolini L; Masci B. Ring-Closure Reactions. 9. Kinetics of Ring Formation From omicron- omega-Bromoalkoxy Phenoxides and omicron- omega-Bromoalkyl Phenoxides in the Range of 11- To 24-Membered Rings. A Comparison With Related Cyclization Series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 6308–6312. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Casadei MA; Galli C; Mandolini L. Ring-Closure Reactions. 22. Kinetics of Cyclization of Diethyl (omega-Bromoalkyl)Malonates in the Range of 4- To 21-Membered Rings. Role of Ring Strain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Chen K; Arnold FH Engineering Cytochrome P450s for Enantioselective Cyclopropenation of Internal Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6891–6895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Zhou AZ; Chen K; Arnold FH Enzymatic Lactone-Carbene C–H Insertion to Build Contiguous Chiral Centers. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5393–5398. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Roccatano D. Structure, Dynamics, and Function of the Monooxygenase P450BM3: Insights From Computer Simulations Studies. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 2015, 27, 273102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Chang YT; Loew GH Molecular Dynamics Simulations of P450BM3 Examination of Substrate-Induced Conformational Change. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1999, 16, 1189–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zhou Y; Guo S; Huang Q; Lang Q; Chen GQ; Zhang X. Facile Access to Chiral gamma-Butyrolactones via Rhodium-Catalysed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of gamma-Butenolides and gamma-Hydroxybutenolides. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 4888–4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Bode JW; Doyle MP; Protopopova MN; Zhou Q-L Intramolecular Regioselective Insertion into Unactivated Prochiral Carbon−Hydrogen Bonds with Diazoacetates of Primary Alcohols Catalyzed by Chiral Dirhodium(II) Carboxamidates. Highly Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Natural Lignan Lactones. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 9146–9155. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Doyle MP; Protopopova MN; Zhou Q-L; Bode JW; Simonsen SH; Lynch V. Optimization of Enantiocontrol for Carbon–Hydrogen Insertion with Chiral Dirhodium(II) Carboxamidates. Synthesis of Natural Dibenzylbutyrolactone Lignans from 3-Aryl-1-propyl Diazoacetates in High Optical Purity. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 6654–6655. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Wang Y; Hu X; Du H. Vicinal-Diamine-Based Chiral Chain Dienes as Ligands for Rhodium(I)-Catalyzed Highly Enantioselective Conjugated Additions. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5482–5485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Knight AM; Kan SBJ; Lewis RD; Brandenberg OF; Chen K; Arnold FH Diverse Engineered Heme Proteins Enable Stereodivergent Cyclopropanation of Unactivated Alkenes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 372–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Brandenberg OF; Prier CK; Chen K; Knight AM; Wu Z; Arnold FH Stereoselective Enzymatic Synthesis of Heteroatom-Substituted Cyclopropanes. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2629–2634. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Dehli JR; Gotor V. Parallel Kinetic Resolution of Racemic Mixtures: A New Strategy for the Preparation of Enantiopure Compounds? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2002, 31, 365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Eames J. Parallel Kinetic Resolutions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 885–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Mao R; Wackelin DJ; Jamieson CS; Rogge T; Gao S; Das A; Taylor DM; Houk KN; Arnold FH Enantio- and Diastereoenriched Enzymatic Synthesis of 1,2,3-Polysubstituted Cyclopropanes from (Z/E)-Trisubstituted Enol Acetates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 16176–16185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.