Abstract

BACKGROUND

Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) is a leading cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality, but there are no therapeutic targets and modalities to prevent ALD-related liver fibrosis. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) α and δ play a key role in lipid metabolism and intestinal barrier homeostasis, which are major contributors to the pathological progression of ALD. Meanwhile, elafibranor (EFN), which is a dual PPARα and PPARδ agonist, has reached a phase III clinical trial for the treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and primary biliary cholangitis. However, the benefits of EFN for ALD treatment is unknown.

AIM

To evaluate the inhibitory effects of EFN on liver fibrosis and gut-intestinal barrier dysfunction in an ALD mouse model.

METHODS

ALD-related liver fibrosis was induced in female C57BL/6J mice by feeding a 2.5% ethanol (EtOH)-containing Lieber-DeCarli liquid diet and intraperitoneally injecting carbon tetrachloride thrice weekly (1 mL/kg) for 8 weeks. EFN (3 and 10 mg/kg/day) was orally administered during the experimental period. Histological and molecular analyses were performed to assess the effect of EFN on steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and intestinal barrier integrity. The EFN effects on HepG2 lipotoxicity and Caco-2 barrier function were evaluated by cell-based assays.

RESULTS

The hepatic steatosis, apoptosis, and fibrosis in the ALD mice model were significantly attenuated by EFN treatment. EFN promoted lipolysis and β-oxidation and enhanced autophagic and antioxidant capacities in EtOH-stimulated HepG2 cells, primarily through PPARα activation. Moreover, EFN inhibited the Kupffer cell-mediated inflammatory response, with blunted hepatic exposure to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and toll like receptor 4 (TLR4)/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling. EFN improved intestinal hyperpermeability by restoring tight junction proteins and autophagy and by inhibiting apoptosis and proinflammatory responses. The protective effect on intestinal barrier function in the EtOH-stimulated Caco-2 cells was predominantly mediated by PPARδ activation.

CONCLUSION

EFN reduced ALD-related fibrosis by inhibiting lipid accumulation and apoptosis, enhancing hepatocyte autophagic and antioxidant capacities, and suppressing LPS/TLR4/NF-κB-mediated inflammatory responses by restoring intestinal barrier function.

Keywords: Liver fibrosis, Ethanol, Gut barrier function, Apoptosis, Autophagy, Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor

Core Tip: Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) α and δ play a key role in lipid metabolism and intestinal barrier homeostasis, which are major contributors to alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) pathogenesis. This study elucidates the preventive effect of elafibranor, a dual PPARα/δ agonist from ALD-related liver fibrosis induced by ethanol plus carbon tetrachloride in mice. This effect is involved in multifaceted regulatory functions: (1) Suppression of lipid accumulation and improvement of autophagy in hepatocytes, which reduced apoptosis and enhanced antioxidant activities; and (2) Inhibition of toll like receptor 4 pathway with blockade of hepatic influx of lipopolysaccharide by repairing intestinal barrier integrity. This regimen represents a potential strategy against ALD-related liver fibrosis.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD), which is a notorious harmful consequence of excessive alcohol consumption, places an enormous burden worldwide[1-4]. ALD represents a spectrum of liver injury, ranging from hepatic steatosis to more advanced stages with fibrosis progression, including steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma[1-4]. Currently, approximately 25% of cirrhosis-related mortality worldwide are causally related with alcohol consumption[1-4]. Therefore, identification of therapeutic targets and modalities to prevent ALD-related liver fibrosis is urgent.

ALD causes liver fibrosis through a multifaceted mechanism, which includes lipid accumulation, apoptosis, and proinflammatory response. In the process of ethanol (EtOH) metabolism, EtOH and acetaldehyde are continuously oxidized by alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase, respectively, to generate large amounts of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide[5,6]. These changes shift liver metabolism toward the reductive synthesis of lipids[5,6]. Moreover, excessive EtOH consumption augments the activity of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c, which is the master regulator of fatty acid synthesis, and dampens the activity of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) α, which controls fatty acid breakdown[5-8]. Consequently, fatty acids, which are esterified into triglycerides (TGs), accumulate in hepatocytes as lipid droplets[5-8].

The gut–liver crosstalk is also functionally involved in the pathophysiology of ALD[4-6,9,10]. Excessive alcohol consumption compromises the integrity of the intestinal barrier by disrupting tight junctions, resulting in the transfer of gut-derived lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to liver tissue; thereafter, LPS is recognized by toll like receptor 4 (TLR4), which is expressed on the liver parenchyma and innate immune cells[9-11]. The LPS/TLR4 axis triggers the downstream activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), which is a master regulator of the proinflammatory response in ALD[9-11].

PPARα and PPARδ have been known to represent promising therapeutic targets in chronic liver disease, including ALD[12,13]. PPARα is abundantly expressed in metabolically active tissues, such as the liver, heart, kidneys, and in-testines. As described above, PPARα activation is functionally associated with the pathways of hepatic lipid metabolism, including fatty acid oxidation, elongation, and desaturation and TG synthesis and breakdown[8]. Moreover, PPARα plays a key role in protecting against oxidative stress by increasing the expression of antioxidant enzymes[14,15]. Therefore, PPARα is a potential target for detoxifying EtOH-induced hepatotoxicity, thereby, preventing ALD progression. Meanwhile, PPARδ has been implicated in lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis in various organs, including the liver[16]. In a recent animal study on metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) models, PPARδ was shown to reduce hepatic steatosis through autophagy-mediated fatty acid oxidation[17]. Moreover, because of its intestinal expression, PPARδ activation can increase the proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells and suppress macrophage-derived inflammation[18]. Consistently, another study found that a selective PPARδ agonist attenuated EtOH-induced liver injury and improved gut barrier function in mice[19]. However, the efficacy of each monoagonist of PPARα or PPARδ alone in inhibiting liver fibrosis development in ALD appears to be limited.

Elafibranor (EFN), which is a dual PPARα/PPARδ agonist, has been developed reached a phase III clinical trial for MASH[20]. Although EFN demonstrated a modest effect on the histological resolution of MASH, it had no beneficial effect on fibrosis[20]. Meanwhile, a recent phase III clinical trial on primary biliary cholangitis has shown that EFN treatment resulted in significantly greater improvements in the relevant biochemical indicators of cholestasis[21]. However, the effect of EFN on ALD-related fibrosis remains unclear. In the current study, we sought to elucidate the benefits of EFN-mediated dual activation of PPARα/PPARδ on ALD-related liver fibrosis, particularly its the effects on lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and intestinal barrier function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and compounds

Ten-week-old female and male C57BL/6J mice (CLEA Japan, Osaka, Japan) were caged with free access to food and water, under controlled temperature (23 ± 3 °C) and humidity (50% ± 20%) and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. This study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Nara Medical University (No. 13130) and was performed in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council. EFN (code name GFT505) was purchased from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, United States). GW7647 and GSK3787 (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) were used as selective antagonists of PPARα and PPARδ, respectively.

In vivo experimental protocol

Female mice (n = 40) were randomly divided into four experimental groups (n = 10 each) and underwent treatment for 8 weeks (Figure 1A). The control group was fed a non-EtOH normal liquid diet (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, United States) and received intraperitoneal injections of corn oil (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) three times weekly. Lactose hydrate (FUJIFILM, Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) was administered as the vehicle for EFN. The three ALD mice groups were fed a 2.5% (v/v) EtOH-containing Lieber–DeCarli liquid diet (research diets); received intraperitoneal injection of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) (FUJIFILM, Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) three times a week (1 mL/kg); and received daily gavage of either: (1) Lactose hydrate as the vehicle; (2) Low dose EFN (3 mg/kg); or (3) High dose EFN (10 mg/kg)[22]. Additionally, male mice (n = 24) were randomly divided into four experimental groups (n = 6 each) and underwent treatment similar to female mice. After 8 weeks of experimental intervention, mice were anesthetized by intravenous injection of 150 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital and euthanized. Blood was drawn from the aorta, and the liver and ileum were removed immediately after sacrifice.

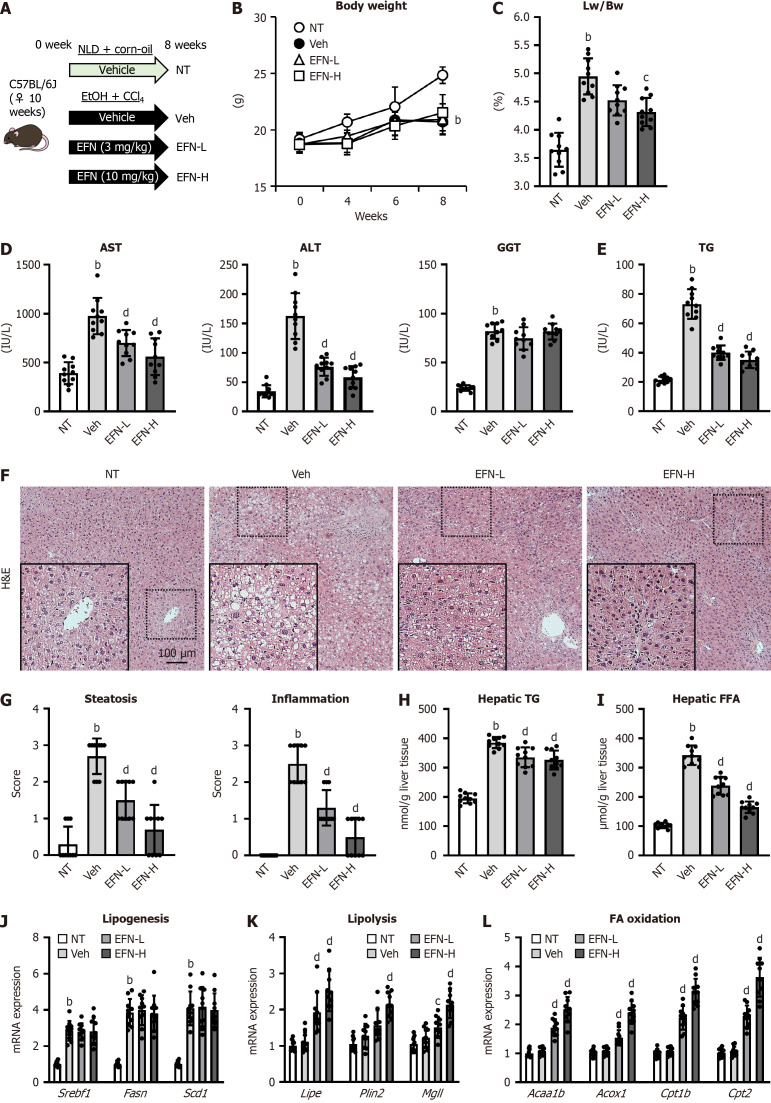

Figure 1.

Elafibranor on steatohepatitis and lipid accumulation in the alcohol-associated liver disease mice. A: In vivo experimental design; B: Changes in the body weights during the experimental period (n = 10); C: Liver/body weight at the end of experiment (n = 10); D: Serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase and gamma glutamyl transferase (n = 10); E: Serum triglyceride level (n = 10); F: Representative microphotographs of hematoxylin and eosin of the livers in the experimental mice; G: Hepatic pathological scores for steatosis and inflammation. Localized magnified images in the lower left corner of each picture (n = 10); H: Hepatic triglyceride content; I: Hepatic free fatty acid concentration (n = 10); J-L: Hepatic mRNA level of the markers related to lipogenesis (J), lipolysis (K), fatty acid oxidation (L) (n = 10). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Quantitative values are indicated as fold changes to the values of non-therapeutic group. Data are the mean ± SD. bP < 0.01 vs non-therapeutic group; cP < 0.05 vs vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; dP < 0.01 vs vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group, significant difference between groups by Student’s t-test. NT: Non-therapeutic group; Veh: Vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; EFN-L: Elafiblanor (3 mg/kg/day)-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; EFN-H: Elafibranor (10 mg/kg/day)-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; NLD: Normal liquid diet; EtOH: Ethanol; CCL4: Carbon tetrachloride; EFN: Elafiblanor; Lw: Liver weight; Bw: Body weight; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; GGT: Gamma glutamyl transferase; TG: Triglyceride; H&E: Hematoxylin and eosin; FFA: Free fatty acid; FA: Fatty acid.

Cell culture

The human hepatocellular cell line HepG2 and the human activated hepatic stellate cell (HSC) line LX-2 were obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (Osaka, Japan) and Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany), respectively. The human intestinal epithelial cell line Caco-2 was purchased from Riken BRC (Ibaraki, Japan). The cells were suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Nacalai tesque), which was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 25 mmol/L glucose and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 air environment. All assays for the Caco-2 cells were performed after 10-20 passages. Depending on each assay, the cells were incubated with EtOH (0-50 mmol/L), EFN (0-30 μM), GW7647 (10 μM), and GSK3787 (10 μM).

Biochemical analysis

Serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) were measured using Mouse enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for each enzyme (Abcam).

Histological and immunohistochemical analyses

Paraffin sections (4 μm) of mouse liver and ileum tissues were prepared with hematoxylin and eosin staining and Sirius-Red staining. Two pathologists independently evaluated liver pathology scores by randomly magnifying 10 fields from each slide by 400 × according to previously reported criteria[23]. Cell apoptosis in liver sections was measured by the TdT-mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) assay using an in situ apoptosis detection kit (Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemical detection of Ki67, α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), and F4/80 (Supplementary Table 1) was performed on paraffin liver sections (4 μm), and subsequent sections were exposed to HRP-antibody colored with DAB. Paraffin ileum sections (4 μm) were prepared for immunofluorescence, incubated with primary antibody overnight, followed by the secondary antibody, and then mounted with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. The primary antibodies included zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), occludin, and claudin-2 (Supplementary Table 1). The secondary antibodies included Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Semiquantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ software version 64 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States).

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from mouse liver and ileum tissue specimens and whole cell lysates using Trizol kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc, St. Louis, MO, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The RNA was cleaned using the QiagenRNeasy miniRNA cleanup kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States). The concentration of total RNA was performed by measuring the absorbance of RNA sample solutions at 260 nm by using a NanoDrop ND-1000 UV-Vis (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total RNA (1.0 μg) was reverse transcribed using iScript cDNA reverse transcription kits (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed using the Fast Start Universal SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed using Applied Biosystems® 7500 Real-Time PCR Systems (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with corresponding primers (Supplementary Table 2). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was simultaneously assayed as a loading control. Data was analyzed using a 2-ΔΔCT method.

Western blotting

According to the standard protocol, proteins were isolated from the mouse liver and ileum tissues in RIPA lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) plus Halt™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The protein concentrations were measured by Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and normalized to 2.5 μg/μL. Protein samples were separated by sodium-dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transferred to an Invitrolon™ polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After sealing with 5% skimmed milk, the membranes were successively incubated overnight at 4 °C with diluted primary antibodies, including LC3, IκBα, p-NFκB, NF-κB, Bcl-2, and Mcl-1 (Supplementary Table 1). The next day, the membrane was washed and incubated with Amersham ECL IgG and HRP-linked F(ab)2 fragment (1:5000, Cytiva, Tokyo, Japan) as secondary antibodies. Chemiluminescence was detected using a Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States) with Bright™ CL1500 Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software version 64 (NIH).

TG and free fatty acid concentrations

The TG content in mouse serum, liver tissue, and cultured HepG2 was measured using Triglyceride-Glo™ Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, United States), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The free fatty acid content in mouse liver tissue was determined using the Free Fatty Acid Assay Kit (Abcam), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein content was normalized using Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cleaved caspase-3 levels and caspase-3/7 activity

To assess in vivo cell apoptosis, the cleaved caspase-3 concentrations in mouse liver and ileum tissues were measured using the Cleaved-Caspase-3 (D175) ELISA Kit (Raybiotech, Norcross, GA, United States), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein content was normalized using Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In vitro apoptosis in the HepG2 and Caco-2 cells (1 × 106 cells) was determined using the Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay System (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Superoxide dismutase 1 and catalase levels

The levels of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) and catalase (CAT) in mouse liver tissue were measured using a Mouse Superoxide Dismutase 1 ELISA Kit (Abcam) and a Mouse Catalase ELISA Kit (CUSABIO, Houston, TX, United States), respectively, following the manufacturers’ instructions. Both enzyme levels were also determined in the cultured HepG2 cells using the Human Superoxide Dismutase 1 ELISA Kit and Human Catalase ELISA Kit (Abcam), respectively, following the manufacturers’ instructions.

Hydroxyproline and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 levels and matrix metalloproteinase activity

The mouse liver tissue concentrations of hydroxyproline and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1) and activity of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2, MMP9, and MMP13 were assessed using a Hydroxyproline Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego), Mouse TIMP1 ELISA Kit (Abcam) and SensoLyte 490 MMP2, MMP9, and MMP-13 Assay Kits (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA, United States), respectively, following the manufacturers’ instructions.

Fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran intestinal permeability assay

The intestinal permeability was assessed by the in vivo fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran permeability assay using additional experimental mice groups (n = 10 for each group)[24]. After a 12-hour fast, the mice were administered a dose of FITC-dextran (4 kDa) (Sigma-Aldrich) (600 mg/kg) dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline by oral cannulation. Then, 2.5 hours after FITC–dextran administration, approximately 200 μL of blood was drawn via the portal vein and centrifuged for 15 minutes at 3500 × g at 4 °C. The plasma FITC-dextran concentrations were assessed in a plate reader with an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and an emission wavelength of 520 nm.

Cell viability and proliferation assays

HepG2 or LX-2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well) with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 24 hours. Thereafter, the cells were exposed with/without EtOH (50 mmol/L) and in different concentrations of EFN (0-30 μM). Cell viability was determined using WST-8 Assay Kit (Abcam), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Transepithelial electrical resistance

To evaluate the epithelial barrier function in Caco-2 cells, transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured using a Millicell-ERS device (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, United States), as previously described[25]. The result was multiplied by the effective membrane area to obtain the final TEER value. The electrical resistance was expressed in units of Ω/cm2 using the surface area of the Trans-well insert.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed with a 2-sided Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance, followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test, as appropriate using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, United States). Statistical significance was defined as a P < 0.05. Additional methods can be found online in the Supplementary material.

RESULTS

Effect of EFN on the activation of hepatic PPARα/δ signaling in the ALD mice

Figure 1A displays the in vivo study design to assess the effects of EFN on EtOH + CCl4-induced ALD-related liver injury in mice. Initially, we verified the effect of EFN on the activation of PPARα and PPARδ signaling in the liver and intestinal tissues of ALD mice. In the ALD mice, the hepatic expression of PPARA was decreased and treatment with EFN increased its expression (Supplementary Figure 1A). PPARα plays a key role in the regulation of lipid metabolism in the liver of ALD by phospholipase A2 (PLA2)/cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 pathway[26]. Consistently, treatment with EFN increased the hepatic level of PLA2 and COX-2 in parallel with increased hepatic PPARA expression in the ALD mice (Supplementary Figure 1B). Meanwhile, the hepatic expression of PPARD was also decreased in the ALD mice but treatment with EFN did not alter the hepatic expression of PPARD as well as its target gene, Cyp2b10 (Supplementary Figure 1C and D)[27].

EFN reduced steatohepatitis and lipid accumulation in the ALD mice

Compared with the control female mice, the ALD mice demonstrated inhibited body weight gain, and treatment with both low and high doses of EFN did not significantly alter the body weight loss in the ALD mice (Figure 1B). Meanwhile, the ALD mice showed marked hepatomegaly, which was attenuated by treatment with high-dose EFN (Figure 1C). The serum levels of AST, ALT, and GGT were markedly elevated in the ALD mice, and treatment with EFN significantly reduced the levels of AST and ALT but did not affect the GGT level (Figure 1D). As shown in Figure 1E, the ALD mice exhibited hypertriglyceridemia, which was suppressed by EFN treatment. Histological analysis revealed hepatic steatosis and necroinflammation in the ALD mice, and these histological changes were attenuated by EFN treatment (Figure 1F and G). In accordance with the attenuation of hepatic steatosis, EFN treatment significantly reduced the hepatic levels of TG and free fatty acid (Figure 1H and I). These inhibitory effects of EFN on steatohepatitis were also observed in male mice as well as female mice (Supplementary Figure 2A-D).

Next, we evaluated the effect of EFN on lipid metabolism in the liver of the ALD mice. EFN did not change the hepatic mRNA levels of the lipogenesis-related markers, including Srebf1, Fasn, and Scd1 (Figure 1J). Meanwhile, treatment with EFN significantly increased the hepatic expressions of the markers related with lipolysis (i.e., Lipe, Plin2, and Mgll) and fatty acid oxidation (i.e., Acaa1b, Acox1, Cpt1b, and Cpt2) (Figure 1K and L).

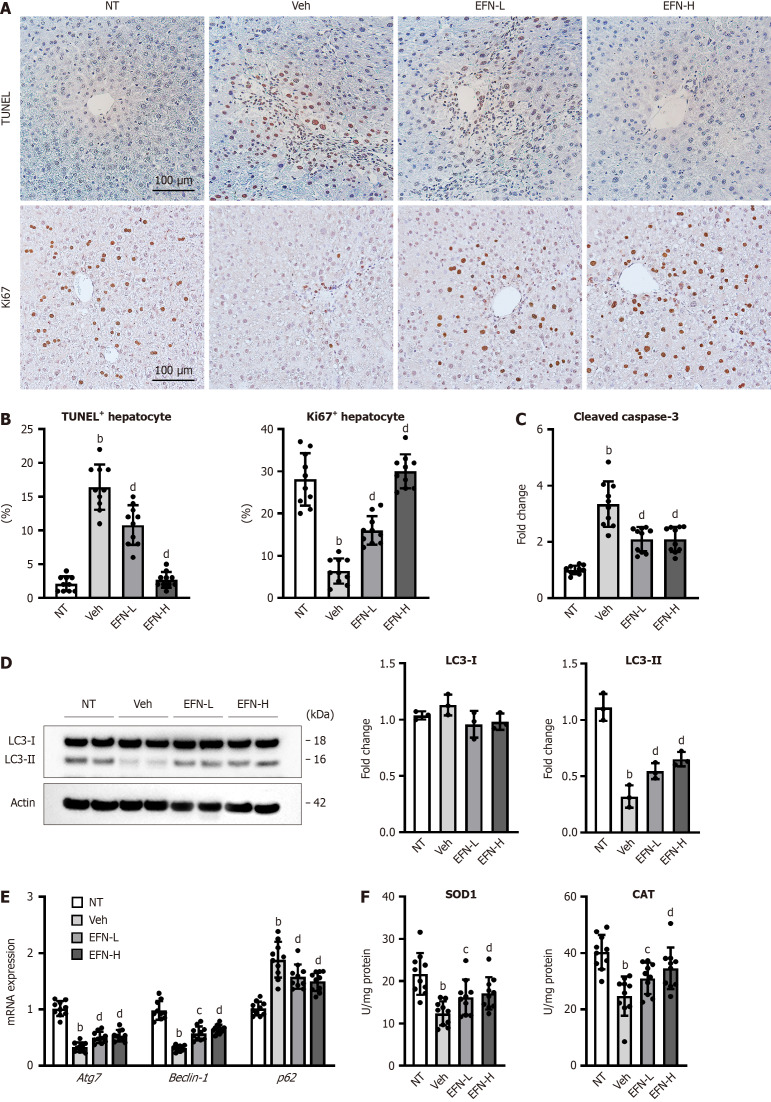

EFN suppressed hepatocyte apoptosis by improving autophagy and antioxidant activity in the ALD mice

We next assessed the effect of EFN on hepatocyte cell death in the ALD mice. In accordance with the progression of steatosis and necroinflammation, the number of TUNEL-positive apoptotic hepatocytes were higher, whereas the number of Ki67-positive proliferative hepatocytes were lower in the ALD mice than in the control mice (Figure 2A and B). EFN treatment significantly decreased the apoptosis and increased hepatocyte proliferation in the ALD mice (Figure 2A and B). Reflecting hepatocyte apoptosis, the level of cleaved caspase-3 in the liver tissue increased in the ALD mice, and this was suppressed by EFN treatment (Figure 2C). The autophagy-related markers, including hepatic LC3-II levels, and the expression of Atg7 and Beclin-1 were decreased in the ALD mice, indicating that EtOH + CCl4 administration impaired autophagy in mice (Figure 2D and E). To support this inference, the ALD mice showed an increase in the hepatic expression of p62, which is a predictor of autophagy flux and is inversely correlated with autophagy activity (Figure 2E). Treatment with EFN induced the upregulation of LC3-II, Atg7, and Beclin-1 and downregulation of p62 (Figure 2D and E). Moreover, EFN treatment increased the hepatic levels of antioxidant markers, including SOD1 and CAT, in the ALD mice (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

Elafibranor on hepatocyte cell death, autophagy and oxidative stress in the alcohol-associated liver disease mice. A: Representative microphotographs of TdT-mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) and Ki67 staining of the livers in the experimental mice; B: Quantification of TUNEL-positive hepatocytes and Ki67-positive hepatocytes in high-power field (n = 10); C: Cleaved caspase-3 level in the liver tissue (n = 10); D: Western blot for LC3-1 and 2 protein level in the liver tissue. Actin was used as an internal control (n = 3); E: Hepatic mRNA level of the markers related to autophagy (n = 10); F: Hepatic level of antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase 1 and catalase (n = 10). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (E and F). Quantitative values are indicated as fold changes to the values of non-therapeutic group (C-E). Data are the mean ± SD. bP < 0.01 vs non-therapeutic group; cP < 0.05 vs vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; dP < 0.01 vs vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group, significant difference between groups by Student’s t-test. NT: Non-therapeutic group; Veh: Vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; EFN-L: Elafiblanor (3 mg/kg/day)-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; EFN-H: Elafibranor (10 mg/kg/day)-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; TUNEL: TdT-mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling; SOD: Superoxide dismutase; CAT: Catalase.

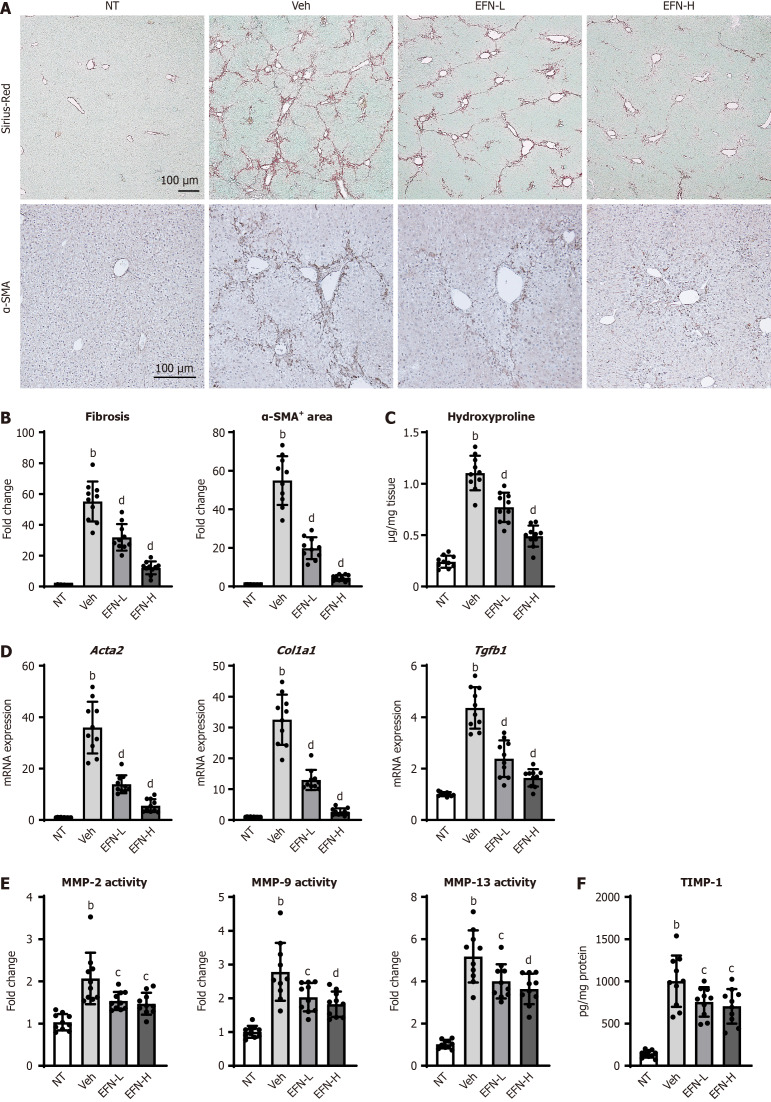

EFN exerted an antifibrotic effect in the ALD mice

The ALD mice exhibited fibrotic livers as identified by Sirius-Red staining of liver sections (Figure 3A). Treatment with EFN markedly reduced hepatic fibrosis at both doses (3 and 10 mg/kg), as well as the number of α-SMA+ myofibroblasts, which was increased in ALD mice (Figure 3A and B). Semiquantitative analysis showed that the degree of liver fibrosis and HSC expansion was reduced to less than 50% after treatment with EFN, especially at a high dose (Figure 3B). Similar to what was observed in the effect on steatohepatitis, the inhibition of fibrosis by EFN was observed not only in female mice but also in male mice (Supplementary Figure 3A and B). In accordance with these changes in the histological features, EFN treatment reduced the hepatic content of hydroxyproline in the ALD mice (Figure 3C). Moreover, the ALD mice had increased hepatic mRNA expressions of profibrotic genes (i.e., Acta2, Col1a1, and Tgfb1), and this effect was suppressed by EFN treatment (Figure 3D). We also assessed the activity of MMPs in regulating extracellular matrix homeostasis. As shown in Figure 3E, the ALD mice exhibited increased activity of hepatic MMP2, MMP9, and MMP13, and this effect was reduced by EFN treatment. These effects of EFN on MMP activity were associated with a decrease in hepatic TIMP-1 levels (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Elafibranor on hepatic fibrosis development in the alcohol-associated liver disease mice. A: Representative microphotographs of sirius-red and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) staining of the livers in the experimental mice; B: Quantification of sirius-red stained fibrotic area and α-SMA-positive area in high-power field (n = 10); C: Hepatic concentration of hydroxyproline (n = 10); D: Hepatic mRNA level of profibrotic markers (n = 10); E: Hepatic activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-2, MMP-9, and MMP-13 (n = 10); F: Hepatic level of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (n = 10). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (D). Quantitative values are indicated as fold changes to the values of non-therapeutic group (B, D and E). Data are the mean ± SD. bP < 0.01 vs non-therapeutic group; cP < 0.05 vs vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; dP < 0.01 vs vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group, significant difference between groups by Student’s t-test. NT: Non-therapeutic group; Veh: Vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; EFN-L: Elafiblanor (3 mg/kg/day)-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; EFN-H: Elafibranor (10 mg/kg/day)-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin; MMP: Matrix metalloproteinases; TIMP1: Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1.

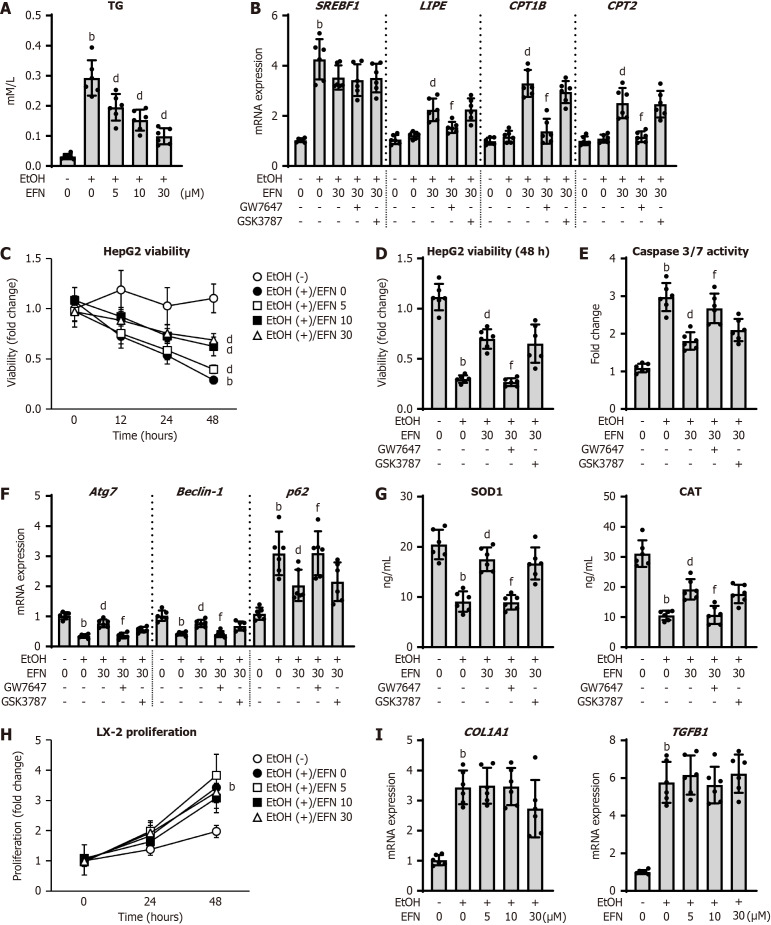

EFN protected against EtOH-stimulated steatosis and apoptosis in HepG2 cells but did not directly affect LX-2 cells

Following the ameliorative effect of EFN on alcoholic liver injury in mice, we analyzed its effects on hepatocytes and activated HSCs using HepG2 and LX-2 cells. EtOH exposure increased the TG levels in HepG2 cells, and EFN effectively suppressed this effect in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4A). Regarding the markers of lipid metabolism, EFN did not change the mRNA expression of SREBF1, but it increased those of LIPE, CPT1B, and CPT2 in the EtOH-exposed HepG2 cells (Figure 4B). Interestingly, the effect of EFN on lipid accumulation was negated by pretreatment with GW7647 but was not changed by GSK3787 (Figure 4B), suggesting that this effect was mainly mediated by PPARα activation. As shown in Figure 4C-E, EFN dose-dependently suppressed the decline in cell viability and increased caspase-3/7 activity in EtOH-stimulated HepG2 cells. We also found that EFN improved autophagic activity, as indicated by the upregulation of Atg7 and Beclin-1 and the downregulation of p62 in the EtOH-stimulated HepG2 cells (Figure 4F). Moreover, EFN treatment increased the production of antioxidant markers in HepG2 cells (Figure 4G). These effects on cell survival, autophagy, and oxidative stress were predominantly inhibited by pretreatment with GW7647 (Figure 4D-G). In contrast, EFN did not affect cell proliferation or profibrogenic activity in the EtOH-stimulated LX-2 cells (Figure 4H and I).

Figure 4.

Elafibranor on the ethanol-stimulated human hepatocytes and human hepatic stellate cells. A: Intracellular triglyceride content in HepG2 cells (n = 6); B: Intracellular mRNA level of the markers related to lipid metabolism in HepG2 cells (n = 6); C: Chronological change in HepG2 cell viability by treatment with ethanol (EtOH) and/or elafibtanor (EFN) (n = 6); D: Effect of a selective antagonists of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)α (GW7647) or PPARδ (GSK3787) on EtOH and EFN-treated HepG2 cell viability (incubation for 48 hours) (n = 6); E: Intracellular caspase 3/7 activity in HepG2 cells (n = 6); F: Intracellular mRNA level of the markers related to autophagy in HepG2 cells (n = 6); G: Intracellular levels of superoxide dismutase 1 and catalase in HepG2 cells (n = 6). HepG2 cells were incubated with (A and C) EtOH (0 or 50 mmol/L) and EFN (0, 5, 10, 30 μM) for 24 hours (A) or 0, 12, 24, and 48 hours (C), EtOH (0 or 50 mmol/L) and EFN (0 or 30 μM) for 48 hour following pretreatment with GW7647 (10 μM) or GSK3787 (10 μM) for 6 hours (B, D-G); H: Chronological change in LX-2 cell proliferation by treatment with EtOH and/or EFN (n = 6); I: Intracellular mRNA level of the profibrotic markers in LX-2 cells (n = 6). LX-2 cells were incubated with EtOH (0 or 50 mmol/L) and EFN (0, 5, 10, and 30 μM) for 0, 24, 48 hours (H) or 24 hours (I). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (B, F and I). Quantitative values are indicated as fold changes to the values of EtOH (-)/EFN (0 μM)-treated group (B-F, H and I). Data are the mean ± SD. bP < 0.01 vs ethanol (-)/elafibtanor (0 μM)-treated group; dP < 0.01 vs ethanol (+)/elafibtanor (0 μM)-treated group; fP < 0.01 vs ethanol (+)/elafibtanor (30 μM)-treated group. EtOH: Ethanol; EFN: Elafibtanor; SOD: Superoxide dismutase; CAT: Catalase; TG: Triglyceride.

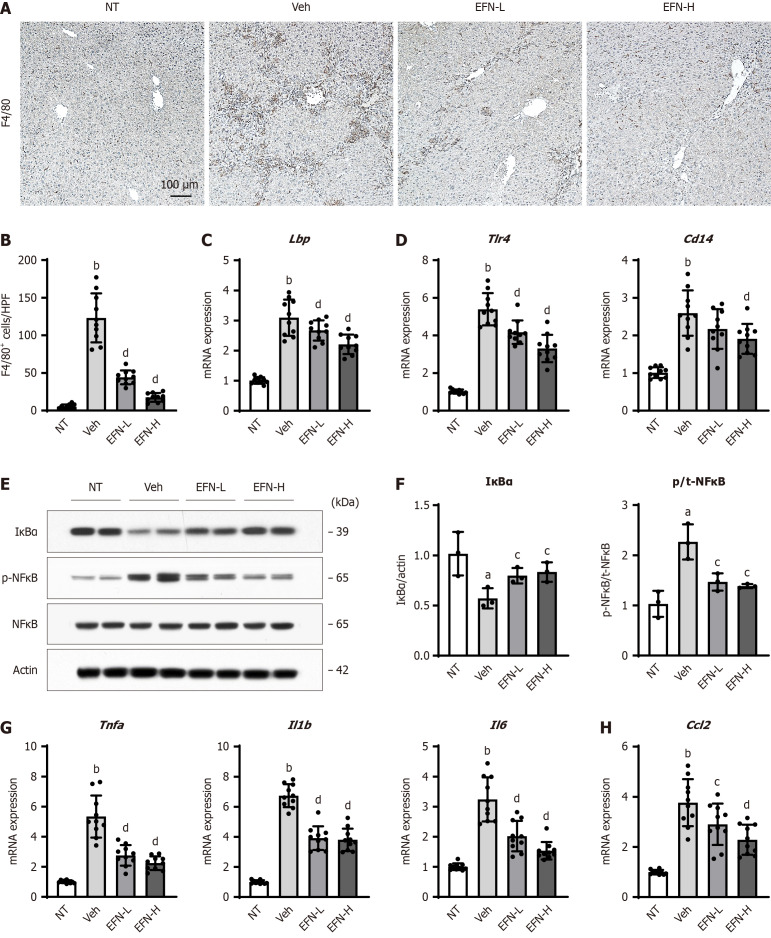

EFN inhibited macrophage activation and TLR4/NF-κB signaling in the liver of ALD mice

The inflammatory status in the ALD mice liver was examined based on the EFN-induced improvement in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. F4/80+ macrophages infiltration was observed in the liver of the ALD mice, which was attenuated by EFN treatment (Figure 5A and B). In the pathogenesis of ALD progression, the LPS/TLR4 pathway plays a key role in the hepatic activation of macrophages[9-11]. As shown in Figure 5C and D, the ALD mice showed an increase in hepatic mRNA levels of LPS-binding protein (Lbp), a reactant that mediates innate immune responses triggered by LPS, and Tlr4 and its coreceptor Cd14, which can recognize LPS. Notably, the upregulation of these genes was significantly suppressed by EFN treatment (Figure 5C and D).

Figure 5.

Elafibranor on Kupffer cell-mediated inflammatory response in the alcohol-associated liver disease mice. A: Representative microphotographs of F4/80 staining of the livers in the experimental mice; B: Quantification of F4/80-positive cells in high-power field (n = 10); C and D: Hepatic mRNA level of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (C), toll like receptor 4 and CD14 (D) (n = 10); E: Western blot for the protein expression of IκBα, p-nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) and NF-κB in the liver tissue. Actin was used as an internal control; F: Quantification of the protein level of IκBα and the ratio of NF-κB phosphorylation based on western blotting (n = 10); G and H: Hepatic mRNA level of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin 1β (Il1b), and Il6 (G), and Ccl2 (H) (n = 10). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (C, D, G and H). Quantitative values are indicated as fold changes to the values of non-therapeutic group. Data are the mean ± SD. aP < 0.05 vs non-therapeutic group; bP < 0.01 vs non-therapeutic group; cP < 0.05 vs vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; dP < 0.01 vs vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group, significant difference between groups by Student’s t-test. NT: Non-therapeutic group; Veh: Vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; EFN-L: Elafiblanor (3 mg/kg/day)-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; EFN-H: Elafibranor (10 mg/kg/day)-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa B; Lbp: Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein; TLR: Toll like receptor; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; IL: Interleukin.

In ALD mice, these increased mRNA expression levels were accompanied by decreased IκBα protein levels and augmented phosphorylation of NF-κB, indicating IκBα degradation and NF-κB phosphorylation (Figure 5E and F). EFN treatment attenuated the TLR4-mediated activation of NF-κB in the ALD mice, consistent with the reduced hepatic overload of LPS (Figure 5E and F). Consequently, EFN treatment reduced the hepatic expression of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha (Tnfa), interleukin-6 (Il6), and Il1b and the chemokine Ccl2, which were increased in the ALD mice (Figure 5G and H).

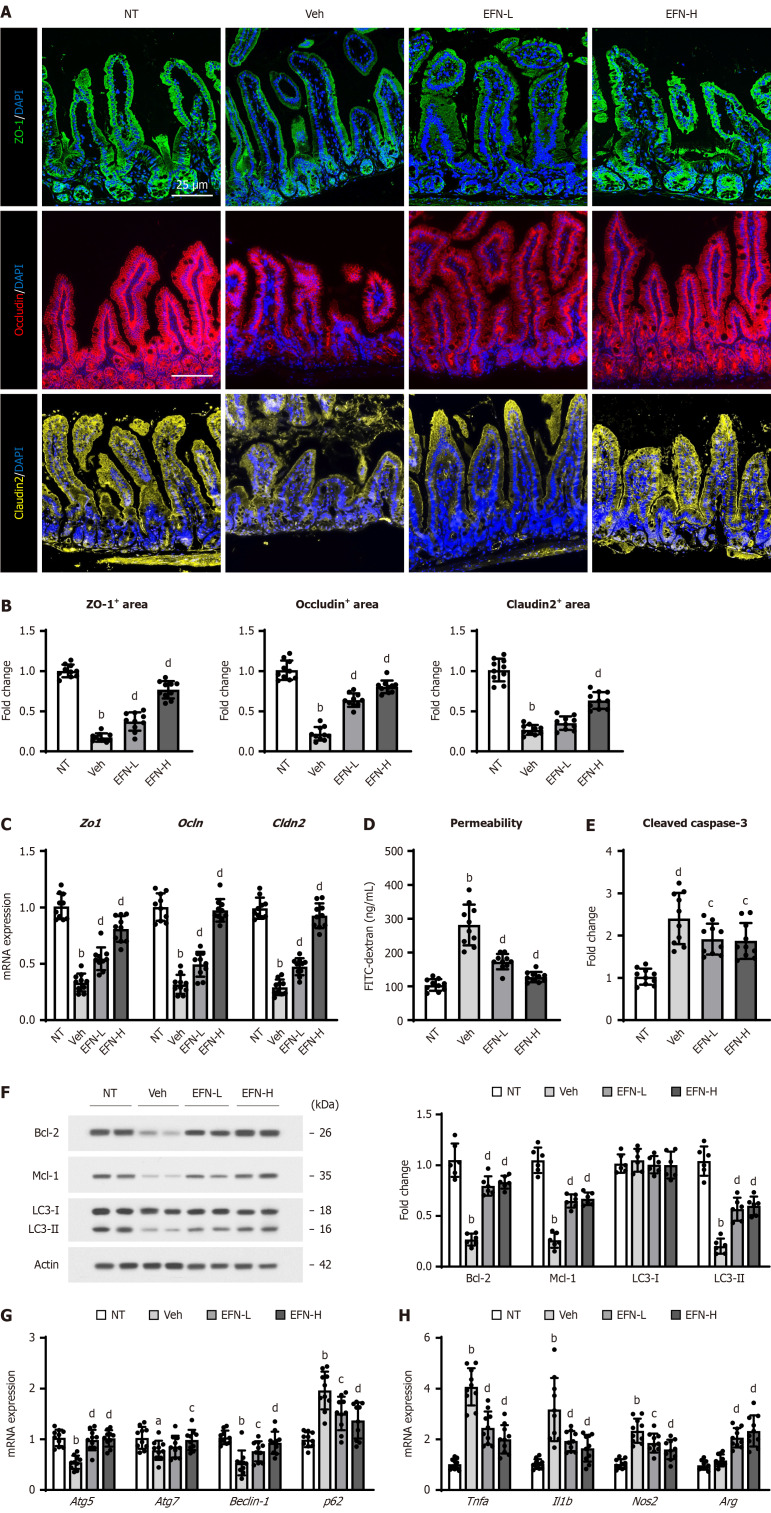

EFN protected the gut barrier integrity and restored intestinal autophagic activity in the ALD mice

Given that EFN reduced the hepatic Lbp expression (Figure 5C), we focused on the effect of EFN on intestinal barrier integrity related to LPS influx into the liver. Intestinal PPARA and PPARD expressions were decreased in the ALD mice, and treatment with EFN did not alter the intestinal expression of PPARA but increased that of PPARD (Supplementary Figure 4A and B). Next, we validated the selected gene expression which is related to PPARδ-mediated gut barrier homeostasis[19]. In the ALD mice, intestinal expression of Ftcd and Sox9 that are involved in reducing tight junction proteins (TJPs), increasing inflammation, and inhibiting proliferation of epithelial cells were increased, and those of Dhrs9, FoxM1, S100G, and Mgl2 that promote gut barrier function and have anti-inflammatory properties, were decreased (Supplementary Figure 4C and D). Notably, these changes in gene expression in ALD mice were significantly attenuated by treatment with EFN (Supplementary Figure 4C and D). Figure 6A displays a marked decrease in the intestinal expression of TJPs, including ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-2, in the ALD mice. Quantitative analysis revealed a reduced TJP expression to less than 25% in the ALD mice, compared with that in the control mice (Figure 6B). Notably, treatment with EFN effectively suppressed the loss of TJP expression in the ALD mice (Figure 6A and B). Consistently, the intestinal mRNA levels of Zo1, Ocln, and Cldn2 in the ALD mice were decreased by EFN treatment (Figure 6C). Along with the decrease in TJP expression, plasma levels of FITC-dextran, which leaked from the intestinal tract into the portal vein, were elevated in the ALD mice (Figure 6D). In accordance with the restoration of TJP expression, EFN treatment inhibited the leak of FITC-dextran from the intestine, as indicated by the decrease in its portal levels (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Elafibranor on intestinal barrier function in the alcohol-associated liver disease mice. A: Representative microphotographs of ileum sections immunofluorescent stained with tight junction proteins (TJPs) including zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), occludin and claudin-2; B: Quantitation of ZO-1, occludin and claudin-2 immunopositive area in high-power field (n = 10); C: Intestinal mRNA levels of TJPs (n = 10); D: Blood levels of fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran (4 kDa) 4 hours after oral administration (n = 3); E: Cleaved caspase-3 level in the ileum tissue (n = 10); F: Western blot for the protein expression of Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and LC3-1 and 2 in the ileum tissue. Actin was used as an internal control; G and H: Intestinal mRNA level of the markers related to autophagy (G) and macrophage activation (H) (n = 10). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (C, G, and H). Quantitative values are indicated as fold changes to the values of non-therapeutic group (B, C, E-H). Data are the mean ± SD. aP < 0.05 vs non-therapeutic group; bP < 0.01 vs non-therapeutic group; cP < 0.05 vs vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; dP < 0.01 vs vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group, significant difference between groups by Student’s t-test. NT: Non-therapeutic group; Veh: Vehicle-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; EFN-L: Elafiblanor (3 mg/kg/day)-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; EFN-H: Elafibranor (10 mg/kg/day)-treated alcohol-associated liver disease group; ZO-1: Zonula occludens-1; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; IL: Interleukin; FITC: Fluorescein isothiocyanate.

To analyze the mechanism underlying the improvement of intestinal permeability, we further evaluated the effect of EFN on apoptosis and inflammation in the intestines of the ALD mice. As shown in Figure 6E, the level of cleaved caspase-3 was elevated, indicating promoted apoptosis in the intestine of the ALD mice. Concomitantly, the intestinal expressions of the antiapoptotic markers Bcl-2 and Mcl-1 decreased (Figure 6F). We found that the promotion of epithelial apoptosis was accompanied by autophagy dysfunction, as indicated by the downregulation of LC3-II; decrease in Atg5, Atg7, and Beclin-1; and increase in p62 mRNA expressions in the intestine of the ALD mice (Figure 6F and G). Remarkably, EFN treatment suppressed this impaired autophagy-induced epithelial apoptosis (Figure 6E-G). Moreover, treatment with EFN decreased the expression of the M1 macrophage markers Tnfa, Il1b, and Nos2 and increased the expression of the M2 macrophage marker Arg in the intestine of the ALD mice (Figure 6H).

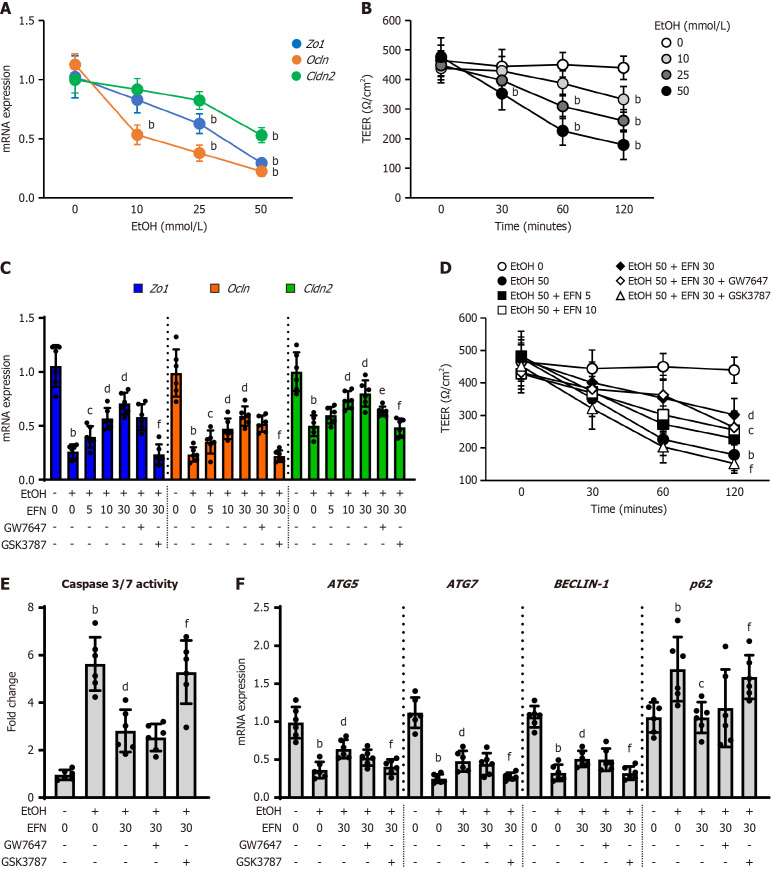

EFN directly improved EtOH-stimulated apoptosis and permeability in Caco-2 cells

We further investigated the direct effects of EFN on intestinal barrier function using Caco-2 human intestinal cells. EtOH stimulation dose-dependently deprived the Caco-2 cells of TJP expression and the results showed that EtOH stimulation at 50 mmol/L induced the greatest decrease in TJP expression (Figure 7A). Consequently, TEER, which is a vital indicator of epithelial cellular barrier integrity, was decreased by EtOH stimulation (Figure 7B). Treatment with EFN dose-dependently restored TJP expression and attenuated the TEER decline in the EtOH (50 mmol/L)-stimulated Caco-2 cells (Figure 7C and D). These effects of EFN on intestinal barrier function were inhibited by GW7647 and GSK3787 at a significantly stronger degree by the latter (Figure 7C and D). These results suggested that the effect of EFN on intestinal barrier function appeared to be predominantly mediated by PPARδ activation rather than by PPARα activation. Reflecting the effect on the ALD mice, EFN significantly reduced caspase-3/7 activity, which was elevated after EtOH stimulation of the Caco-2 cells (Figure 7E). This antiapoptotic effect of EFN was accompanied by an improvement in autophagic activity, as indicated by the increased expressions of ATG5, ATG7, and BECLIN-1 and the decreased expression of p62 (Figure 7F). Consistent with its action on intestinal barrier function, EFN was suggested to exert its effects mainly through PPARδ agonism.

Figure 7.

Elafibranor on the ethanol-stimulated human intestinal epithelial cells. A: Intracellular mRNA levels of tight junction proteins (TJPs) including zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), Ocln, and Cldn2 in ethanol (EtOH)-stimulated Caco-2 cells (n = 6); B: Integrity of the epithelial cellular barrier in EtOH-stimulated Caco-2 cells determined as transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) (n = 6). Cells were incubated with different concentration of EtOH (0, 10, 25, and 50 mmol/L) for 120 minutes (A) and 0, 30, 60, and 120 minutes (B); C: Effect of elafibranor (EFN) on the TJPs mRNA expression in the EtOH-stimulated Caco-2 cells (n = 6); D: Effect of EFN on the TEER in the EtOH-stimulated Caco-2 cells (n = 6). Cells were incubated with EtOH (0 or 50 mmol/L) and EFN (0, 5, 10, 30 μM) for 120 minutes (C) or 0, 30, 60, and 120 minutes (D) following pretreatment with GW7647 (10 μM) or GSK3787 (10 μM) for 15 minutes; E: Effect of EFN on the intracellular caspase 3/7 activity in the EtOH-stimulated Caco-2 cells (n = 6); F: Effect of EFN on mRNA expression of the markers related to autophagy in the EtOH-stimulated Caco-2 cells (n = 6). Cells were incubated with EtOH (0 or 50 mmol/L) and EFN (0 or 30 μM) for 48 hours following pretreatment with a peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)α antagonist, GW7647 (10 μM) or a PPARδ antagonist, GSK3787 (10 μM) for 6 hours (E and F). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (A, C, and F). Quantitative values are indicated as fold changes to the values of EtOH (-)/EFN (0 μM)-treated group (A, C, E, and F). Data are the mean ± SD. bP < 0.01 vs ethanol (-)/elafibranor (0 μM)-treated group; cP < 0.05 vs ethanol (+)/elafibranor (0 μM)-treated group; dP < 0.01 vs ethanol (+)/elafibranor (0 μM)-treated group; eP < 0.05 vs ethanol (+)/elafibranor (30 μM)-treated group; fP < 0.01 vs ethanol (+)/elafibranor (30 μM)-treated group. EtOH: Ethanol; EFN: Elafibtanor; TEER: Transepithelial electrical resistance; ZO-1: Zonula occludens-1.

DISCUSSION

ALD is based on two conditions, including hepatic injury and addictive disorder. Alcohol cessation is the cornerstone of treatment and should be recommended to all patients with ALD. In fact, abstinence from excessive alcohol consumption has been shown to improve clinical outcomes and prognosis, even in patients with ALD-related liver cirrhosis[28-30]. However, for most patients who seek treatment, considering sobriety as an acceptable, desirable, or realistic treatment goal is difficult[28-30]. The present study demonstrated that EFN, which is a dual PPARα/PPARδ agonist, effectively prevented hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in an EtOH + CCl4-induced ALD mice model. We determined the following multifaceted underlying mechanism that was mediated by PPARα/PPARδ activation: (1) Suppression of lipid accumulation and improvement of autophagy in hepatocytes, which reduced apoptosis and enhanced antioxidant activities; and (2) Blockade of hepatic influx of LPS by repairing intestinal barrier integrity.

In response to alcohol abuse, lipid accumulation in hepatocytes is the initial stage of ALD[4-8]. Excessive alcohol intake increases the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in hepatocytes and impairs mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation, resulting in lipid accumulation[4-8,31]. Our gene expression analysis suggested that the inhibitory effect of EFN on lipid accumulation was based on the augmentation of lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation rather than on the inhibition of lipogenesis. Moreover, several studies have shown that autophagy protects the liver from alcohol-induced injury[32,33]. Autophagy is known to promote cell survival by supplying nutrients during starvation and by selectively scavenging damaged organelles, such as mitochondria[34]. Proper autophagy, such as mitophagy and lipid autophagy, assists in improving alcohol-induced liver dysfunction, which leads to apoptosis secondary to damaged mitochondria and reactive oxygen species accumulation in hepatocytes[29,35]. In the current study, EFN treatment attenuated hepatocyte apoptosis, with improved autophagy and enhanced antioxidant capacity, in accordance with reduced lipid accumulation in the liver of the ALD mice. Notably, the cell-based assay elucidated that these effects on EtOH-exposed HepG2 cells were predominantly mediated by PPARα activation. Downregulation and/or dysfunction of PPARα is involved in the development of ALD[36]. Kong et al[37] reported that pharmacological activation of PPARα attenuated steatohepatitis by increasing lipid oxidation and downregulating proinflammatory factors in ALD models. In addition, the hepatic expression and transcriptional activity of PPARα are closely associated with the induction of autophagy by directly increasing the expression of several autophagy genes, such as LC3B[38]. Moreover, a recent animal study has shown that PPARα activation reversed murine alcoholic liver injury and increased the levels of antioxidant enzymes, including CAT and SOD1[39,40]. We used HepG2 cells as the hepatocyte-like cells for in vitro study. HepG2 cells are used to identify the effects of alcohol on human hepatocyte-like cells due to the expression of ADH4, which metabolizes EtOH[41-43]. Moreover, HepG2 cells have been used to evaluate the PPAR-mediated pharmacological effect (including EFN) against hepatocyte injury[44-46]. Therefore, there are no major obstacles to the use of HepG2 cells as human hepatocyte-like cells in the present study. On the other hand, since HepG2 cells are essentially a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, analysis of the effects of EFN using primary cultured hepatocytes would be an issue for future study.

In some studies, a PPARα agonist was shown to ameliorate alcoholic liver injury, but its effect on liver fibrosis is unknown or limited. Our findings demonstrated a marked inhibitory effect of EFN on liver fibrosis in the ALD mice. EFN did not show a direct effect on LX-2 cells, which are activated HSCs, but it inhibited hepatic LPS/TLR4 pathway and proinflammatory response, which both play crucial roles in the development of ALD-related fibrosis. Therefore, we focused on the effect of EFN on intestinal barrier function, which functionally regulates LPS influx to the liver. We and another group have reported that EtOH + CCl4-treated ALD mice showed intestinal barrier disruption and downregulation of intestinal TJPs, including ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-2[25,47,48]. EFN effectively restored the expression of TJPs, resulting in reduced intestinal permeability and hepatic LPS influx in the ALD mice. Moreover, we confirmed the protective effect of EFN on intestinal barrier function in EtOH-exposed Caco-2 cells. A previous report showed that EFN restored intestinal integrity in a mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; this may be relevant to the findings of the present study[46]. Moreover, a recent animal study has demonstrated that EFN increased the Beclin-1 and LC3-II levels and autophagy flux and decreased the p62 and caspase levels in the gut of a different ALD model[49]. Interestingly, in our study, the effects of EFN on intestinal barrier function were mainly mediated by PPARδ activation. Several mechanisms are involved in the regulatory effect of PPARδ activation on intestinal barrier function. PPARδ activation can suppress macrophage-driven inflammation by downregulating the intestinal expressions of proinflammatory mediators, including monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and IL-1β, and upregulating the expression of various anti-inflammatory genes[19]. Furthermore, PPARδ activation was reported to augment antiapoptotic pathways in intestinal epithelial cells[49] and was suggested to enhance autophagy by increasing Beclin-1 and LC3II expressions in several types of cells[50]. These findings supported our results on the prevention of intestinal barrier disruption through EFN-mediated PPARδ activation.

Our findings showed that EFN could affect hepatocytes and intestinal epithelial cells by activating PPARα and PPARδ, respectively. However, some studies have reported that PPARα activation affects intestinal epithelial cells[51,52]. PPARα activation ameliorated chemical-induced colitis and enhanced intestinal barrier function in a rodent model of inflammatory bowel disease[51]. In Caco-2 cells, treatment with the PPARα activator fenofibrate protected barrier function, attenuated junctional flexure, and increased Claudin-1 expression after exposure to high glucose levels or inflammatory cytokines[52]. Meanwhile, PPARδ has also been implicated in lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis in the liver[53]. Recent clinical studies demonstrated that treatment with PPARδ agonists reduced the hepatic fat content in overweight patients with mixed dyslipidemia[54,55]. Likewise, Tong et al[17] reported that the pharmacological and genetic activation of PPARδ had a beneficial effect in attenuating hepatic steatosis by activating autophagy in the hepatocytes of obese mice. Despite this reported evidence, our in vitro study on EtOH-stimulated HepG2 or Caco-2 cells suggested that the effects of PPARα on intestinal barrier function and PPARδ on hepatocytes were limited. However, the effectiveness of EFN might have differed, depending on the experimental model; we did not identify the mechanism for the imbalanced effect of EFN. Therefore, further studies using different ALD models are needed to focus on the EFN-mediated effects of PPARα on the intestine and of PPARδ on hepatocytes.

In addition to the aforementioned limitation, the role of EFN in bile acid metabolism was not fully examined in the current study. A PPARα agonist was reported to inhibit the expression of farnesoid X receptor target genes, thereby, reducing hepatic bile acid levels[56]. Furthermore, a PPARδ agonist was found to reduce bile acid accumulation in the liver and small intestine, leading to attenuated EtOH-induced liver disease in mice[19]. Because the regulation of bile acid is closely associated with both lipid metabolism and intestinal barrier homeostasis, further analysis of the relationship between the EFN effect on bile acid metabolism and its ameliorative effect on alcoholic liver injury using the present model would be important. Second, our results showed that EFN suppressed the LPS/TLR4 signaling in the liver tissue of ALD mice, but the status of TLR4 activation were not specifically evaluated at the macrophage level. It has been recognized that LPS/TLR4 pathway also plays a key role in HSC activation[57]. Thus, further studies are needed to prove that the reduction of LPS influx into the liver by EFN mainly affects the activation of macrophages, including analysis of macrophages and HSCs isolated from experimental mouse models.

Third, we found that EFN had a preventive effect on ALD alongside EtOH + CCl4 exposure. In practice, however, pharmacologic treatment is usually given when liver fibrosis has already developed. Thus, further investigation is needed using a model of drug administration at the stage of advanced cirrhosis.

CONCLUSION

Taken together, EFN appeared to prevent the development of liver fibrosis in EtOH + CCl4-induced ALD mice. Notably, EFN can exert dual pharmacological actions by activating PPARα, which mediated the inhibition of lipid accumulation and apoptosis and the enhanced autophagic activity and antioxidative capacity of hepatocytes, and PPARδ, which mediated the protection of intestinal barrier function, resulting in suppression of the LPS/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in the liver. Although the safety of EFN has been proven in clinical trials on primary biliary cholangitis, our results suggested that this drug may eventually emerge as a viable treatment option for ALD.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional review board of Nara Medical University, Kashihara, Japan (authorization numbers: 13130).

Institutional animal care and use committee statement: All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

ARRIVE guidelines statement: The authors have read the ARRIVE guidelines, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade B, Grade C, Grade C

Novelty: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Feng X; Pavlidis TE; Zhang XF S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zheng XM

Contributor Information

Aritoshi Koizumi, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Kosuke Kaji, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan. kajik@naramed-u.ac.jp.

Norihisa Nishimura, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Shohei Asada, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Takuya Matsuda, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Misako Tanaka, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Nobuyuki Yorioka, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Yuki Tsuji, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Koh Kitagawa, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Shinya Sato, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Tadashi Namisaki, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Takemi Akahane, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Hitoshi Yoshiji, Department of Gastroenterology, Nara Medical University, Kashihara 634-8521, Japan.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Julien J, Ayer T, Bethea ED, Tapper EB, Chhatwal J. Projected prevalence and mortality associated with alcohol-related liver disease in the USA, 2019-40: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e316–e323. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asrani SK, Mellinger J, Arab JP, Shah VH. Reducing the Global Burden of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: A Blueprint for Action. Hepatology. 2021;73:2039–2050. doi: 10.1002/hep.31583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, Kamath PS. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol. 2023;79:516–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackowiak B, Fu Y, Maccioni L, Gao B. Alcohol-associated liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2024;134 doi: 10.1172/JCI176345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1572–1585. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu X, Fan X, Miyata T, Kim A, Cajigas-Du Ross CK, Ray S, Huang E, Taiwo M, Arya R, Wu J, Nagy LE. Recent Advances in Understanding of Pathogenesis of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2023;18:411–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-031521-030435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.You M, Fischer M, Deeg MA, Crabb DW. Ethanol induces fatty acid synthesis pathways by activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29342–29347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202411200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng FG, Zhang XN, Liu SX, Wang YR, Zeng T. Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α in the pathogenesis of ethanol-induced liver disease. Chem Biol Interact. 2020;327:109176. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szabo G, Bala S. Alcoholic liver disease and the gut-liver axis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1321–1329. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i11.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albillos A, de Gottardi A, Rescigno M. The gut-liver axis in liver disease: Pathophysiological basis for therapy. J Hepatol. 2020;72:558–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao R. Endotoxemia and gut barrier dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;50:638–644. doi: 10.1002/hep.23009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka N, Aoyama T, Kimura S, Gonzalez FJ. Targeting nuclear receptors for the treatment of fatty liver disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;179:142–157. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Königshofer P, Brusilovskaya K, Petrenko O, Hofer BS, Schwabl P, Trauner M, Reiberger T. Nuclear receptors in liver fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2021;1867:166235. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2021.166235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toyama T, Nakamura H, Harano Y, Yamauchi N, Morita A, Kirishima T, Minami M, Itoh Y, Okanoue T. PPARalpha ligands activate antioxidant enzymes and suppress hepatic fibrosis in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nan YM, Wang RQ, Fu N. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α, a potential therapeutic target for alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8055–8060. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magadum A, Engel FB. PPARβ/δ: Linking Metabolism to Regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19 doi: 10.3390/ijms19072013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong L, Wang L, Yao S, Jin L, Yang J, Zhang Y, Ning G, Zhang Z. PPARδ attenuates hepatic steatosis through autophagy-mediated fatty acid oxidation. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:197. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1458-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta RA, Wang D, Katkuri S, Wang H, Dey SK, DuBois RN. Activation of nuclear hormone receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-delta accelerates intestinal adenoma growth. Nat Med. 2004;10:245–247. doi: 10.1038/nm993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu H, Jiang L, Gao B, Gautam N, Alamoudi JA, Lang S, Wang Y, Duan Y, Alnouti Y, Cable EE, Schnabl B. The selective PPAR-delta agonist seladelpar reduces ethanol-induced liver disease by restoring gut barrier function and bile acid homeostasis in mice. Transl Res. 2021;227:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westerouen Van Meeteren MJ, Drenth JPH, Tjwa ETTL. Elafibranor: a potential drug for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2020;29:117–123. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2020.1668375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowdley KV, Bowlus CL, Levy C, Akarca US, Alvares-da-Silva MR, Andreone P, Arrese M, Corpechot C, Francque SM, Heneghan MA, Invernizzi P, Jones D, Kruger FC, Lawitz E, Mayo MJ, Shiffman ML, Swain MG, Valera JM, Vargas V, Vierling JM, Villamil A, Addy C, Dietrich J, Germain JM, Mazain S, Rafailovic D, Taddé B, Miller B, Shu J, Zein CO, Schattenberg JM ELATIVE Study Investigators’ Group; ELATIVE Study Investigators' Group. Efficacy and Safety of Elafibranor in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:795–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2306185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staels B, Rubenstrunk A, Noel B, Rigou G, Delataille P, Millatt LJ, Baron M, Lucas A, Tailleux A, Hum DW, Ratziu V, Cariou B, Hanf R. Hepatoprotective effects of the dual peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/delta agonist, GFT505, in rodent models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2013;58:1941–1952. doi: 10.1002/hep.26461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu JW, Wang H, Yan-Li J, Zhang C, Ning H, Li XY, Zhang H, Duan ZH, Zhao L, Wei W, Xu DX. Differential effects of pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate on TNF-alpha-mediated liver injury in two different models of fulminant hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2008;48:442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matheus VA, Monteiro L, Oliveira RB, Maschio DA, Collares-Buzato CB. Butyrate reduces high-fat diet-induced metabolic alterations, hepatic steatosis and pancreatic beta cell and intestinal barrier dysfunctions in prediabetic mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2017;242:1214–1226. doi: 10.1177/1535370217708188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shibamoto A, Kaji K, Nishimura N, Kubo T, Iwai S, Tomooka F, Suzuki J, Tsuji Y, Fujinaga Y, Kawaratani H, Namisaki T, Akahane T, Yoshiji H. Vitamin D deficiency exacerbates alcohol-related liver injury via gut barrier disruption and hepatic overload of endotoxin. J Nutr Biochem. 2023;122:109450. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2023.109450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Y, Denning KL, Lu Y. PPARα agonist WY-14,643 induces the PLA2/COX-2/ACOX1 pathway to enhance peroxisomal lipid metabolism and ameliorate alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;613:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.04.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koga T, Yao PL, Goudarzi M, Murray IA, Balandaram G, Gonzalez FJ, Perdew GH, Fornace AJ Jr, Peters JM. Regulation of Cytochrome P450 2B10 (CYP2B10) Expression in Liver by Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor-β/δ Modulation of SP1 Promoter Occupancy. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:25255–25263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.755447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabiee A, Mahmud N, Falker C, Garcia-Tsao G, Taddei T, Kaplan DE. Medications for alcohol use disorder improve survival in patients with hazardous drinking and alcohol-associated cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7 doi: 10.1097/HC9.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diaz LA, Winder GS, Leggio L, Bajaj JS, Bataller R, Arab JP. New insights into the molecular basis of alcohol abstinence and relapse in alcohol-associated liver disease. Hepatology. 2023 doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gratacós-Ginès J, Bruguera P, Pérez-Guasch M, López-Lazcano A, Borràs R, Hernández-Évole H, Pons-Cabrera MT, Lligoña A, Bataller R, Ginès P, López-Pelayo H, Pose E. Medications for alcohol use disorder promote abstinence in alcohol-associated cirrhosis: Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2024;79:368–379. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeon S, Carr R. Alcohol effects on hepatic lipid metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2020;61:470–479. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R119000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chao X, Wang S, Zhao K, Li Y, Williams JA, Li T, Chavan H, Krishnamurthy P, He XC, Li L, Ballabio A, Ni HM, Ding WX. Impaired TFEB-Mediated Lysosome Biogenesis and Autophagy Promote Chronic Ethanol-Induced Liver Injury and Steatosis in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:865–879.e12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babuta M, Furi I, Bala S, Bukong TN, Lowe P, Catalano D, Calenda C, Kodys K, Szabo G. Dysregulated Autophagy and Lysosome Function Are Linked to Exosome Production by Micro-RNA 155 in Alcoholic Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2019;70:2123–2141. doi: 10.1002/hep.30766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Picca A, Faitg J, Auwerx J, Ferrucci L, D'Amico D. Mitophagy in human health, ageing and disease. Nat Metab. 2023;5:2047–2061. doi: 10.1038/s42255-023-00930-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salete-Granado D, Carbonell C, Puertas-Miranda D, Vega-Rodríguez VJ, García-Macia M, Herrero AB, Marcos M. Autophagy, Oxidative Stress, and Alcoholic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Potential Clinical Applications. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023;12 doi: 10.3390/antiox12071425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakajima T, Kamijo Y, Tanaka N, Sugiyama E, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K, Fukushima Y, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Aoyama T. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha protects against alcohol-induced liver damage. Hepatology. 2004;40:972–980. doi: 10.1002/hep.20399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kong L, Ren W, Li W, Zhao S, Mi H, Wang R, Zhang Y, Wu W, Nan Y, Yu J. Activation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha ameliorates ethanol induced steatohepatitis in mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:246. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JM, Wagner M, Xiao R, Kim KH, Feng D, Lazar MA, Moore DD. Nutrient-sensing nuclear receptors coordinate autophagy. Nature. 2014;516:112–115. doi: 10.1038/nature13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue I, Goto S, Matsunaga T, Nakajima T, Awata T, Hokari S, Komoda T, Katayama S. The ligands/activators for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) and PPARgamma increase Cu2+,Zn2+-superoxide dismutase and decrease p22phox message expressions in primary endothelial cells. Metabolism. 2001;50:3–11. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.19415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yue R, Chen GY, Xie G, Hao L, Guo W, Sun X, Jia W, Zhang Q, Zhou Z, Zhong W. Activation of PPARα-catalase pathway reverses alcoholic liver injury via upregulating NAD synthesis and accelerating alcohol clearance. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;174:249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donohue TM, Osna NA, Clemens DL. Recombinant Hep G2 cells that express alcohol dehydrogenase and cytochrome P450 2E1 as a model of ethanol-elicited cytotoxicity. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pochareddy S, Edenberg HJ. Chronic alcohol exposure alters gene expression in HepG2 cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1021–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01677.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao L, Shan W, Zeng W, Hu Y, Wang G, Tian X, Zhang N, Shi X, Zhao Y, Ding C, Zhang F, Liu K, Yao J. Carnosic acid alleviates chronic alcoholic liver injury by regulating the SIRT1/ChREBP and SIRT1/p66shc pathways in rats. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016;60:1902–1911. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen WM, Shaw LH, Chang PJ, Tung SY, Chang TS, Shen CH, Hsieh YY, Wei KL. Hepatoprotective effect of resveratrol against ethanol-induced oxidative stress through induction of superoxide dismutase in vivo and in vitro. Exp Ther Med. 2016;11:1231–1238. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tao Z, Zhang L, Wu T, Fang X, Zhao L. Echinacoside ameliorates alcohol-induced oxidative stress and hepatic steatosis by affecting SREBP1c/FASN pathway via PPARα. Food Chem Toxicol. 2021;148:111956. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hakeem AN, Kamal MM, Tawfiq RA, Abdelrahman BA, Hammam OA, Elmazar MM, El-Khatib AS, Attia YM. Elafibranor modulates ileal macrophage polarization to restore intestinal integrity in NASH: Potential crosstalk between ileal IL-10/STAT3 and hepatic TLR4/NF-κB axes. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;157:114050. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inamura T, Miura S, Tsuzuki Y, Hara Y, Hokari R, Ogawa T, Teramoto K, Watanabe C, Kobayashi H, Nagata H, Ishii H. Alteration of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes and increased bacterial translocation in a murine model of cirrhosis. Immunol Lett. 2003;90:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fujimoto Y, Kaji K, Nishimura N, Enomoto M, Murata K, Takeda S, Takaya H, Kawaratani H, Moriya K, Namisaki T, Akahane T, Yoshiji H. Dual therapy with zinc acetate and rifaximin prevents from ethanol-induced liver fibrosis by maintaining intestinal barrier integrity. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:8323–8342. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i48.8323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li TH, Yang YY, Huang CC, Liu CW, Tsai HC, Lin MW, Tsai CY, Huang SF, Wang YW, Lee TY, Huang YH, Hou MC, Lin HC. Elafibranor interrupts adipose dysfunction-mediated gut and liver injury in mice with alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Sci (Lond) 2019;133:531–544. doi: 10.1042/CS20180873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gou Q, Jiang Y, Zhang R, Xu Y, Xu H, Zhang W, Shi J, Hou Y. PPARδ is a regulator of autophagy by its phosphorylation. Oncogene. 2020;39:4844–4853. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basso PJ, Sales-Campos H, Nardini V, Duarte-Silva M, Alves VBF, Bonfá G, Rodrigues CC, Ghirotto B, Chica JEL, Nomizo A, Cardoso CRB. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha Mediates the Beneficial Effects of Atorvastatin in Experimental Colitis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:618365. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.618365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crakes KR, Pires J, Quach N, Ellis-Reis RE, Greathouse R, Chittum KA, Steiner JM, Pesavento P, Marks SL, Dandekar S, Gilor C. Fenofibrate promotes PPARα-targeted recovery of the intestinal epithelial barrier at the host-microbe interface in dogs with diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13454. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92966-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu S, Hatano B, Zhao M, Yen CC, Kang K, Reilly SM, Gangl MR, Gorgun C, Balschi JA, Ntambi JM, Lee CH. Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor {delta}/{beta} in hepatic metabolic regulation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1237–1247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.138115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Risérus U, Sprecher D, Johnson T, Olson E, Hirschberg S, Liu A, Fang Z, Hegde P, Richards D, Sarov-Blat L, Strum JC, Basu S, Cheeseman J, Fielding BA, Humphreys SM, Danoff T, Moore NR, Murgatroyd P, O'Rahilly S, Sutton P, Willson T, Hassall D, Frayn KN, Karpe F. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)delta promotes reversal of multiple metabolic abnormalities, reduces oxidative stress, and increases fatty acid oxidation in moderately obese men. Diabetes. 2008;57:332–339. doi: 10.2337/db07-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bays HE, Schwartz S, Littlejohn T 3rd, Kerzner B, Krauss RM, Karpf DB, Choi YJ, Wang X, Naim S, Roberts BK. MBX-8025, a novel peroxisome proliferator receptor-delta agonist: lipid and other metabolic effects in dyslipidemic overweight patients treated with and without atorvastatin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2889–2897. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pineda Torra I, Claudel T, Duval C, Kosykh V, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Bile acids induce the expression of the human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha gene via activation of the farnesoid X receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:259–272. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, Schwabe RF. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.