“People need to know about their genes and be aware of diseases that may occur”; “the more information available the more informed choices are.” These positive comments on the value of genetic testing came from two visitors to a drop-in “gene shop” which gave information about genetics at Manchester airport, funded as part of the Euroscreen 2 project with staff from the Royal Manchester Children's Hospital Trust.1 They were typical of the visitors who were enthusiastic about testing for themselves and their partners. The Genetic Interest Group, many of whose members come from families affected by genetic disorders, is similarly enthusiastic arguing that “genetic services offer people the potential to acquire information about their genetic make up [which] although it might be bad news, at least allows them to plan out their lives and make informed reproductive decisions.”2 For those who are aware that they are at risk, a genetic test for a specific disorder may well be empowering—it will provide either reassurance or confirmation of that risk. But what would knowledge of their own genetic make up mean for the general population?

The attraction of genetic testing for the health service is the ability to predict; as the Advisory Council on Genetic Testing put it, to “foretell the future with scientific confidence.”3 The possibilities of preventing the onset of a genetic disease and of developing drugs tailored to the individual's genome are promising; at the moment, though, the ability to detect a disorder is outstripping the development of effective treatment. The problems of making a diagnosis, in a currently healthy person, of high risk for a disease that cannot be prevented and may even be untreatable are recognised in the present system. Information, counselling, and support are offered before the individual can decide to be tested, and uptake has been lower than anticipated. For example, only 10-15% of people at risk of Huntington's disease have sought testing, which has been available since 1987. Before testing was offered, most family members at risk had said they would want to be tested.4,5 It is unlikely that the present support system would, or could, be maintained once testing for more disorders becomes routine. Individuals may find out about their own genome without recourse to the health service by commercial testing bought over the counter, by mail order, or via the internet. Although guidelines have been issued by the Advisory Council on Genetic Testing, there are no enforceable controls over who is using the test or for what purpose.3 For instance, parents may test their children for cystic fibrosis or pregnant women test themselves. The Genetic Interest Group has said that the UK Clinical Genetics Society's report on testing children was “overly preoccupied with psychological considerations, and the harm that knowledge of genetic disorders can cause within families.”6 However, parents with a family history of a disorder are in a different position from people who might seek testing for themselves or a child “just to make sure everything is all right” without detailed knowledge of what a positive test result would mean.

Summary points

Knowledge of their own genome imposes a new responsibility on individuals

Increasing individuals' knowledge of their own genome will increase the demands on the health service for information, advice, and treatment

Access to genetic tests should not be routine where there are no clear benefits to those who receive a positive result

Patients' rights to confidentiality and genetic privacy can conflict with the rights of family members and the demands of insurers and employers

An emphasis on genetic factors in multifactorial conditions may divert attention from health improvements that can be made through social and economic action

The views of those with genetic conditions or disabilities should be considered

At risk status

One area of knowledge that people will gain from genetic testing is of risk factors for common multifactorial diseases. The public is already aware of risk factors for, say, coronary heart disease, which might include their family history, but genetic information pinpoints individual rather than group risk and tends to be seen as particularly accurate and determining.7 In practice, the more tests the individual undergoes the more likely it is that some results will be false negatives or false positives. For example, if five tests are given, each of which produces results that are 90% accurate, the probability that they will all give accurate results is just below 60%.8

If a genetic risk is identified, the result puts a new responsibility on individuals, and research has shown that people react in different ways. A study of families affected by Duchenne muscular dystrophy found that one family defined its at risk status as totally discrediting, the other as carrying no stigma at all.9 A neonatal screening programme in Sweden for α1 antitrypsin deficiency aimed to protect babies with the disorder (1 in 2000 births) by advising parents not to smoke because it would increase the risk of lung disease in their babies.10 The test was carried out routinely at the same time as the Guthrie test, without prior information for parents. After the test parents of affected babies were given information on the disorder; but rather than reducing their smoking the parents smoked more than before. These parents had been told that their child had an invisible vulnerability for which there was no definitive treatment, and they reacted with anger and distress.11 This research resulted in a decision to delay screening in Sweden until children were of school age and to consult with and inform the parents when starting screening. There have been many other examples of screening programmes with unintended and undesirable consequences, the best known of which is the sickle cell programme in the United States.12

Demand and access

These examples are of programmes testing for one specific condition, but what about the impact of knowledge of risk factors for a range of different kinds of disorder? The health service will have to cope with the demands of a public that has received different kinds of genetic information.13 Patients may have been tested positively for carrier status for a recessive condition or have risk figures for susceptibility to certain forms of cancer and negative results for some single gene disorders. Whether individuals have bought tests for themselves or been tested through the health service they will require information, advice, and follow up treatment, and in the British system patients are likely to go first to their general practitioners.13 The ability of individuals to follow health and lifestyle advice will be affected by their financial status and their work and family responsibilities. People who have used commercial over the counter or mail order tests could generate a disproportionate workload for the NHS. Individuals, including children, will present who would not have been tested for the specific condition in the NHS or who would have decided not to be tested if they had received pretest counselling. Even those with favourable results may seek a second opinion from a trusted source. The publicity given to commercial tests, through advertising and media reports, could generate additional demands for the same facilities to be available to all, rather than used only in specific clinical contexts.

There is an argument for not allowing easy access to genetic tests where no treatment has been proved effective, providing that the restrictions are not financial and do not differentially affect particular ethnic or social groups. Where there is treatment available, take-up rates can be maximised, as in the case of newborn screening for phenylketonuria in Europe.14 Few parents refuse the test; it is routine; no particular action is required from the parent, nor is informed consent sought. A screening programme for Duchenne muscular dystrophy among newborn boys offered genetic counselling to parents of affected boys and avoided the usual delays in diagnosis. It was found that the high uptake of 94% could be reduced by requiring a more active choice on their part, such as having to post back a card before the analysis of the blood spot would be undertaken.15,16 For cystic fibrosis carrier testing, take-up rates varied from 9% to 70% among patients, depending on how the test was offered.17 Checks on access might also include information on the possibility of stigmatisation, of discrimination in employment and life insurance, and on the implications of genetic information for other family members.18,19 The ease with which take-up rates can be raised or lowered shows that it is difficult to measure public demand accurately.

Targeting resources

Should resources be devoted to individuals knowing about their own genome, as opposed to targeted testing for specific diseases among people known to be at risk? Critics argue that focusing on individual genetic susceptibilities may detract from programmes to tackle social and environmental factors. These factors affect health, but society lacks the political will to tackle them effectively. Abby Lippman writes: “conditions of society such as poverty, racial bias, gender discrimination and lack of political power are among the well-documented non-genetic risks to health that create 'susceptibilities'. Why not call these factors 'markers' and label them for intervention? Why not seek to change employment, income support, housing and taxation policies ... instead of—or at least in addition to—lobbying for 'lifestyle' modifications?”20

Some advocates of disability rights also argue that their lives would be enhanced by environmental and social changes rather than by the new genetics, which “discriminates against and devalues disabled individuals.”21 Those who identify with deaf culture, for example, may be reluctant to take part in linkage analysis studies on genes affecting hearing since they do not see deafness as an undesirable condition.22 However, one writer who is profoundly deaf acknowledges the right to say “no” to genetic technology but argues that those who refuse a cure or improvement to their condition do not have a right “to demand that society pay for the resulting costs of the choice.”23 In this view people have a duty to know about their own genome and to act on the information.

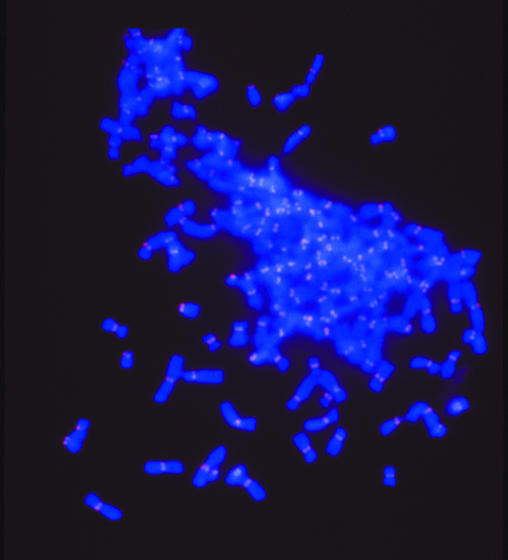

Figure.

TIM YEN

Hela cell

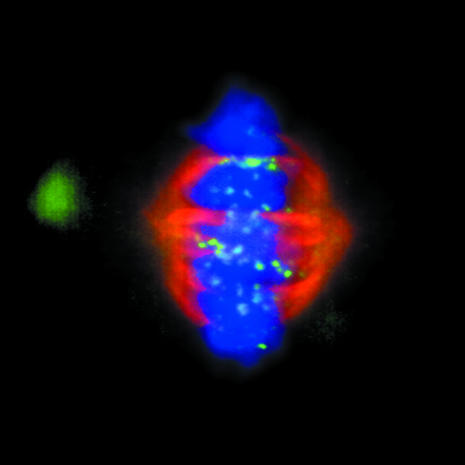

Figure.

GORDON CHAN PHD/TIM YEN

Cell where chromosome segregation is disrupted

Figure.

GORDON CHAN PHD/TIM YEN

Normal metaphase cell

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Levitt M. The gene shop: evaluation of a public education facility. Preston: University of Central Lancashire; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Genetic Interest Group. The present organisation of genetic services in the United Kingdom. London: GIG; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Advisory Council on Genetic Testing. Code of practice and guidance on human genetic testing services supplied direct to the public. London: Health Departments of the United Kingdom; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke A. The genetic testing of children. In: Harper PS, Clarke AJ, editors. Genetics, society and clinical practice. Oxford: Bios; 1997. pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball D, Tyler A, Harper P. Predictive testing of adults and children. In: Clarke A, editor. Genetic counselling: practice and principles. London: Routledge; 1994. pp. 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalby S. GIG reposnse to the UK Clinical Genetics Society report “The genetic testing of children” [letter] J Med Genet. 1995;32:490–491. doi: 10.1136/jmg.32.6.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelkin D, Lindee MS. The DNA mystique. The gene as cultural icon. New York: Freeman; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs; American Medical Association. Multiplex genetic testing. Hastings Center Report. 1998;28:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsons E, Atkinson P. Lay constructions of genetic risk. Sociology of Health and Medicine. 1992;14:437–455. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNeil TF, Sveger T, Thelin T. Psychosocial effects of screening for somatic risk: the Swedish alpha 1-antitrypsin experience. Thorax. 1988;43:505–507. doi: 10.1136/thx.43.7.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thelin T, McNeil TF, Aspegren-Jansson E, Sveger T. Psychological consequences of neonatal screening for alpha 1-antitripsin deficiency. Parental reactions ot the first news of their infants' deficiency. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1985;74:787–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1985.tb10032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradby H. Genetics and racism. In: Marteau T, Richards M, editors. The troubled helix. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 295–316. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lenaghan J. Brave new NHS? The impact of the new genetics on the health service. London: Institute for Public Policy Research; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chadwick R, ten Have H, Husted J, Levitt M, McGleenan T, Shickle D, et al. Genetic screening and ethics: European perspectives. J Med Philos. 1998;23:255–273. doi: 10.1076/jmep.23.3.255.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke A. Newborn screening. In: Harper PS, Clarke AJ, editors. Genetics, society and clinical practice. Oxford: Bios; 1997. pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsons E, Bradley D, Clarke A. Disclosure of Duchenne muscular dystrophy after newborn screening. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:550–553. doi: 10.1136/adc.74.6.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bekker H, Modell M, Denniss G, Silver A, Mathew C, Bobrow M, et al. Uptake of cystic fibrosis testing in primary care: supply push or demand pull? BMJ. 1993;306:1584–1586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6892.1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genetic Interest Group. Confidentiality and medical genetics. London: GIG; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Genetic screening: ethical issues. London: Nuffield Council on Bioethics; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lippman A. Led (astray) by genetic maps: the cartology of the human genome and health care. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:1469–1476. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90049-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchanan A. Choosing who will be disabled: genetic intervention and the morality of inclusion. Social Philosophy and Policy Foundation. 1996;113:18–46. doi: 10.1017/s0265052500003447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grundfast K, Rosen J. Ethical and cultural considerations in research on hereditary deafness. Molecular Biol Genet. 1992;25:973–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tucker B. Deaf American Monograph. 1993. Deafness: 1993-2013: the dilemma; p. 43. :163-5. [Google Scholar]