Abstract

The de novo design of small molecule–binding proteins has seen exciting recent progress; however, high-affinity binding and tunable specificity typically require laborious screening and optimization after computational design. We developed a computational procedure to design a protein that recognizes a common pharmacophore in a series of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase–1 inhibitors. One of three designed proteins bound different inhibitors with affinities ranging from <5 nM to low micromolar. X-ray crystal structures confirmed the accuracy of the designed protein-drug interactions. Molecular dynamics simulations informed the role of water in binding. Binding free energy calculations performed directly on the designed models were in excellent agreement with the experimentally measured affinities. We conclude that de novo design of high-affinity small molecule–binding proteins with tuned interaction energies is feasible entirely from computation.

Molecular recognition underlies catalytic activity of enzymes and drives signaling of protein receptors. Although we have an advanced understanding of both protein design and molecular interactions, the rational design of de novo proteins that specifically bind small molecules with low nanomolar to picomolar affinity is a major challenge (1, 2) that has not been achieved in de novo proteins (3, 4) without experimental screening of large libraries of variants (5-7). Even with the application of recent advances in artificial intelligence to facilitate de novo design (8-10), it has been necessary to screen thousands of independent designs to discover binders with low-micromolar to high-nanomolar dissociation constants (Kd) directly from design algorithms (3, 11-14). Proteins with higher affinity are often desirable. Given the low success rate, screening large numbers of designs often relies on biotinylated or fluorescently labeled versions of their small-molecule targets, which restricts the region of the molecule available for binding. The cost of synthesizing thousands of genes and the necessity of synthetic chemistry for conjugation places a practical limitation on the access of these methods to many groups. Moreover, de novo design methods rely heavily on structural informatics to guide sampling of protein structure and sequence as well as scoring functions that rely on a mix of statistical and physical terms without explicit representation of dynamics, conformational entropy, or water (3-7). This dependence leaves open the fundamental question of whether our understanding is grounded in physical forces or limited exclusively to advanced pattern recognition (15). In this study, we asked whether adherence to simple rules based on physical principles might increase the success rate for designing drug-binding proteins and whether all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with explicit water might be able to recapitulate the experimentally determined binding affinities of high-affinity binders, starting with design models that come directly from computation.

Rationale for design of high-affinity drug-binding proteins

The recognition of polar groups presents a challenge in de novo design of binders because the polar groups must lose most or all of their highly favorable interactions with water molecules upon binding to the protein. To compensate for this loss in hydration, the polar chemical groups of the small molecule must form highly directional and distance-dependent hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions with atomic groups in the protein. These polar interactions are not only required for affinity, but they also provide the specificity of proteins for their substrates over other similarly shaped molecules.

We recently developed a design method known as Convergent Motifs for Binding Sites (COMBS) to enable sampling of only sequences and structures capable of forming such interactions prior to searching for less specific and directional, but energetically favorable, van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions that complete the binding site (3). To facilitate this process, COMBS uses van der Mers (v to search for preferred spatial positions w chemical groups can interact with an amino acid (3). vdMs are similar to rotamers (16), which define favorable positions to arrange an amino acid’s sidechain atoms relative to its backbone atoms. However, vdMs instead define favorable positions of an interacting chemical group fragment relative to a residue’s backbone atoms. Each amino acid type can adopt multiple rotamers, which are widely used in design algorithms to position sidechains onto preexisting backbones. In vdMs, we track the positions of chemical groups that can interact with a given type of amino acid. For example, a GlnCONH2 vdM consists of a glutamine residue that contacts a carboxamide group. Also like rotamers, vdMs can be clustered into similar groups with associated probabilities based on their occurrence in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The COMBS algorithm then finds multiple positions on a given protein backbone that can simultaneously form favorable van der Waals, aromatic, and/or hydrogen-bonded interactions with the chemical groups of a target small molecule. The remainder of the sequence is then filled in through flexible backbone sequence design.

COMBS showed promise in identifying protein backbones and creating sites capable of binding the drug apixaban. In previous work, we identified one protein that bound with Kd = 500 nM and a second with Kd = 5 mM after screening only six designed sequences (3). In the process, we learned lessons that could improve the use of COMBS in design pipelines. Firstly, during the final steps of sequence design and backbone optimization, sidechains were sometimes introduced that ultimately did not form their intended favorable vdMs. Structural analysis showed that they were not in optimal orientations to interact with the drug, and site-directed mutagenesis showed that they made small or no contributions to the free energy of binding. We reasoned that it should be possible to improve binding by using backbone ϕ- or y-dependent vdMs and alternating rounds of COMBS with Rosetta flexible-backbone sequence design. Secondly, binding affinity can be optimized by pre-organizing a receptor’s conformation so that it loses minimal conformational entropy upon binding. Originally, we analyzed preorganization using Rosetta ab initio folding; now we can more reliably determine whether the sequence adopted the desired reorganized structure using the AlphaFold2 program (17).

Another important feature is the need to consider the energetically unfavorable loss of hydrogen bonds between water molecules and both the drug as well as the protein’s binding site, which occurs when the drug binds the pocket. Although COMBS and other algorithms (12) consider the need to form hydrogen bonds to compensate for the loss of hydration, we strove to form a fuller set of compensatory ligand-protein hydrogen bonds to every buried polar atom. We sampled vdMs between the ligand and the first-shell amino acids, as well as vdMs between the first shell and a second shell of interacting residues, which also assures a favorable geometry for the residues directly contacting the ligand. We also opted to bias the orientation of the ligand such that formally charged groups were placed near the surface of the protein, thereby minimizing energic penalties due to Born solvation. We evaluated MD simulations and free energy calculations, which explicitly consider interactions with bulk and bound water molecules that are not fully considered in protein design algorithms, to assess the usefulness of physics-based methods for evaluating the affinity of the designs.

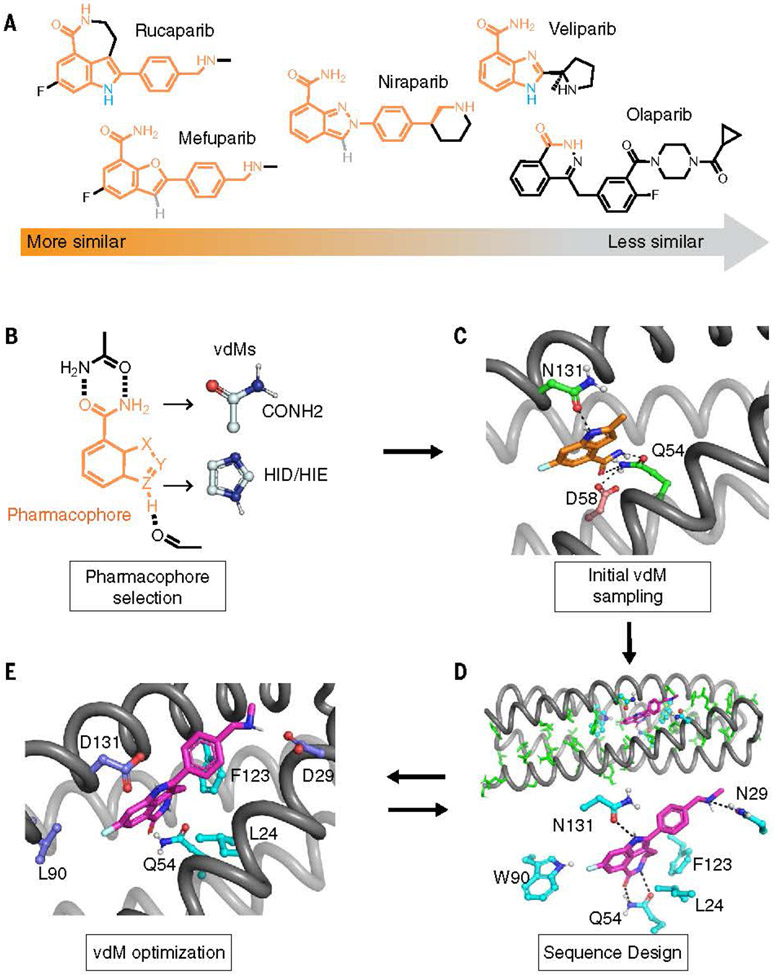

To demonstrate the utility of our refined methods, we chose to design binders of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (PARPi), a recently developed class of clinically useful anticancer drug (18). De novo–designed binders of PARPi drugs might serve as components in detectors, delivery agents, or detoxification agents for these cytotoxic drugs. The pre-dominant class of PARPi drugs share a tripartite pharmacophore consisting of a fused 5,6-bicyclic core, an amide, and a phenyl group bearing a positively charged alkylamine (Fig. 1A). We chose to target rucaparib, the most structurally complex of several related drugs, as our primary target (Fig. 1A), as well as a series PARPi analogs. By considering a series of drugs, we at once provide reagents that might be widely useful while simultaneously testing our understanding of the essential features required for binding.

Fig. 1.

Computational design of PARPi protein binders. (A) PARPi analogs. The shared chemical features are marked in orange. Olaparib is used as a negative control in the design and binding assay. (B to E) The overall design strategy. [(B) and (C)] We first defined the pharmacophore and used COMBS to sample vdMs on the selected protein backbones. At the outset of the design, we chose chemical groups that should form hydrogen bonds when the drug is bound to the binding site. These groups included rucaparib’s indole NH and carboxamide groups (marked in orange). The carboxamide group is present in our vdM library. However, there were relatively few examples of indole NH vdMs in the database, so we used imidazole as a proxy for the indole’s pyrole ring (in the vdMs, the oxygen is marked in red, and nitrogens are marked in blue). We then used COMBS to discover sidechains at different positions of a four-helix bundle template that could simultaneously form hydrogen bonds to the indole and carboxamide chemical groups of the drug. (The COMBS algorithm samples vdMs on a protein backbone and then performs superpositions of a ligand onto the chemical groups of the vdMs; next, COMBS finds all the vdMs with nearby chemical groups to each superposed ligand; and finally, COMBS computes a specific combination of vdMs for each ligand that optimizes a score, such as the vdM prevalence or cluster score.) We discovered a solution in which the carboxamide formed bidentate hydrogen bonds with sidechain of Q54, and the drug’s indole NH interacted with the N131 [in (C), carbon atoms of protein, green; those of rucaparib, orange]. A second-shell interaction to Q54 that was discovered by COMBS was D58 (carbon atoms, brown). (D) We applied flexible backbone sequence design with a custom Rosetta script while fixing the interactions selected from COMBS (rucaparib, purple). (E) We searched for vdMs again based on the design output from the previous sequence step (D). The slightly different (~ 1-Å Ca RMSD) backbone now preferred different vdMs at some locations (higher cluster scores), and these mutations were made. Three residues at 29, 90, and 131 (deep blue) were changed based on COMBS results. Single-letter abbreviations for the amino acid residues referenced throughout the paper are as follows: L, Leu; N, Asn; D, Asp; Q, Gln; W, Trp; F, Phe.

De novo design of high-affinity drug-binding proteins

We used a recursive version of the COMBS algorithm to design rucaparib-binding sites in a family of mathematically generated four-helix bundle proteins. The key binding residues were introduced by using vdMs to identify multiple positions on a given protein backbone that could simultaneously interact favorably with the chemical groups of a target small molecule (Fig. 1, B and C) (materials and methods). Although vdMs are derived from statistics of sidechain and mainchain interactions with one another in the PDB, they can be used to identify binding-site residues capable of forming hydrogen bonds and aromatic interactions with diverse small molecules in much the same way that natural proteins bind a wide variety of small molecules by using a set of 20 amino acids. Although the energetics of these interactions can vary depending on the specific small molecule bound, the fundamental geometries required to achieve binding often remain relatively constant (19). Thus, a common set of vdMs should serve to bind a wide range of compounds. We targeted three chemical groups in rucaparib’s structure: the indole NH and the C=O and NH2 groups of its carboxamide (Fig. 1C). Additionally, COMBS identified Asp58 as a second-shell interaction to the carboxamide of rucaparib (Fig. 1C). It is important to design binding interactions with these groups with sub-Ångstrom accuracy to engender specificity and a favorable free energy of association. Next, the remainder of the sequence was designed by using Rosetta flexible backbone design (Fig. 1D) (3, 20) while retaining the identity of the keystone residues (identified in the COMBS step). The mainchain moved 1-Å root mean square deviation (RMSD) during this step (fig. S1), so a second round of vdM sampling was performed on the relaxed backbone. This procedure identified three mutants involving drug-contacting residues, including N29D, W90L, and N131D (Fig. 1E). A second round of flexible backbone sequence design with this backbone and the newly fixed vdMs resulted in converged sequence-structure combinations (Figs. 1E and 2, A and B), as a third round of COMBS showed that the vdMs were now optimal. The final designs included numerous CH-p and hydrophobic interactions interspersed with specific polar interactions, including four hydrogen bonds (a H-bond donor to the drug’s carboxamide oxygen as well as three H-bond acceptors to the drug’s carboxamide NH, indole NH, and charged ammonium group), as well as second-shell interactions. (Fig. 2C and fig. S2).

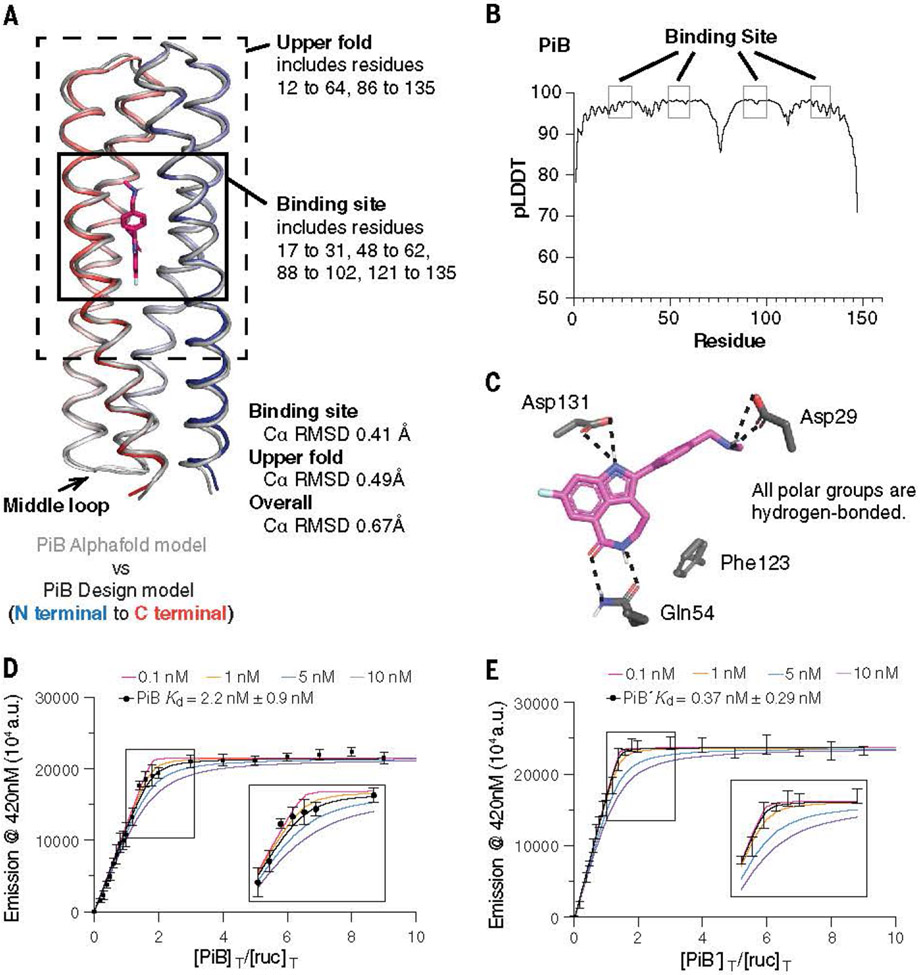

Fig. 2.

Assessing the computational model and experimental binding of PiB to rucaparib. (A) The AlphaFold2 model agreed with the designed PiB, with the binding site Ca RMSD of 0.41 Å, the upper fold Ca RMSD of 0.49 Å, and overall Ca RMSD of 0.67 Å. (B) The predicted local distance difference test scores (pLDDTs) concurred with the trend of RMSD difference of the design model. For example, the N terminal, C terminal, and the middle loop with low pLDDTs (<90) showed higher Ca RMSD. (C) The design model showing that the polar groups of rucaparib are all hydrogen bonded. (D and E) A fluorescence titration showed that PiB and PiB′ bind rucaparib with Kd < 5 nM. The fluorescence emission intensity at 420 nm of rucaparib (excitation wavelength, 355 nm) was measured after titrating aliquots of PiB (D) or PiB′ (E) to a final concentration indicated in the abscissa, in which [PIB]T/[ruc]T or [PIB′]T/[ruc]T refers to the ratio of the molar concentrations of PiB or PiB′ to rucaparib, respectively. The data are well described by a single-site protein-ligand binding model, and a nonlinear least-squares fit to the data returned Kd values of 2.2 ± 0.9 nM for PIB and 0.37 ± 0.29 nM for PiB′. Although the fitting error was relatively small, a sensitivity analysis in which the value of Kd was held constant at various values showed that the data for both proteins were fit within experimental error so long as the Kd was <5 nM. Therefore, although the most probable binding constants were 2 and 0.4 nM, respectively, we can confidently conclude that the values for PiB and PiB′ are <5 nM. The titration was carried out in buffer containing 50-mM Tris and 100-mM NaCl (pH 7.4). a.u., arbitrary units.

Throughout the design process, we ensured that the designs would also retain favorable interactions with most of the common pharmacophores of the three other drugs (materials and methods). However, we predicted that the protein would have lower affinity for niraparib and mefuparib because they lack the H-bonding group indole NH of rucaparib. Additionally, we expected veliparib to bind weakly because it lacks a hydrophobic phenyl group and the position of its charged ammonium group differs from that found in the other three drugs.

The final models were chosen based on multiple criteria: (i) Favorable vdMs (highest total vdM cluster scores); (ii) satisfaction of all potential buried H-bond donors and acceptors in the protein and ligand; (iii) low Rosetta energy (lowest 50 of the 1000 total designs); and (iv) avoidance of clashes with the three other PARP inhibitors, which show structural variability near the amine end of the molecule. Top-scoring designs selected for expression were designated PARPi binder (PiB) and its variant PiB′ (fig. S3 and table S1). PiB′ differs from PiB by the substitution of five solvent-exposed charged residues with alanine to encourage crystallization. The other two proteins chosen for expression (PiB-1 and PiB-2) were less closely related to PiB in structure (RMSD = 0.93 and 0.79 for PiB-1 and PiB-2 to PiB, respectively) and sequence (41 and 42% identity for PiB-1 and PiB-2 to PiB, respectively) (fig. S4). Circular dichroism spectroscopy showed that all four had substantial a-helical character (fig. S5). However, PiB-1 and PiB-2 failed to induce large changes in the fluorescence emission spectrum of rucaparib (fig. S6); therefore, we focused our efforts on PiB and PiB′ (figs. S7 to S11).

Spectral titrations showed that PiB and PiB′ bound the PARPi drugs with high affinity. Incubation of PiB with equimolar concentrations of rucaparib led to a marked blue shift and an increase in intensity of its fluorescence spectrum, as would be expected if its indole core were bound in a rigid, solvent-inaccessible site (figs. S6 and S7). Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of PiB showed that it folded into a well-defined structure and that the addition of a single equivalent of rucaparib led to a new set of peaks, which was consistent with a stoichiometric, specific complex (figs. S10 and S11). Fluorescently monitored titrations of protein into a solution of rucaparib showed that PiB and PiB′ bound with very low to subnanometer affinity (Figs. 2, D and E, and 3A). Even at the lowest experimentally feasible rucaparib concentration, the binding isotherms showed a linear increase in intensity with respect to protein concentration until a single equivalent was added, followed by an abrupt leveling at higher protein concentrations. This behavior is indicative of a dissociation constant that is much lower than the total rucaparib concentration. A nonlinear least-squares fit to the data returned a Kd of 2.2 nM for PiB and 0.37 nM. For PiB′, and a sensitivity analysis showed that the Kd was <5 nM for both proteins (Fig. 2, D and E). Achieving single-digit nanomolar to picomolar binding affinity for de novo– designed proteins has previously required extensive experimental optimization (5).

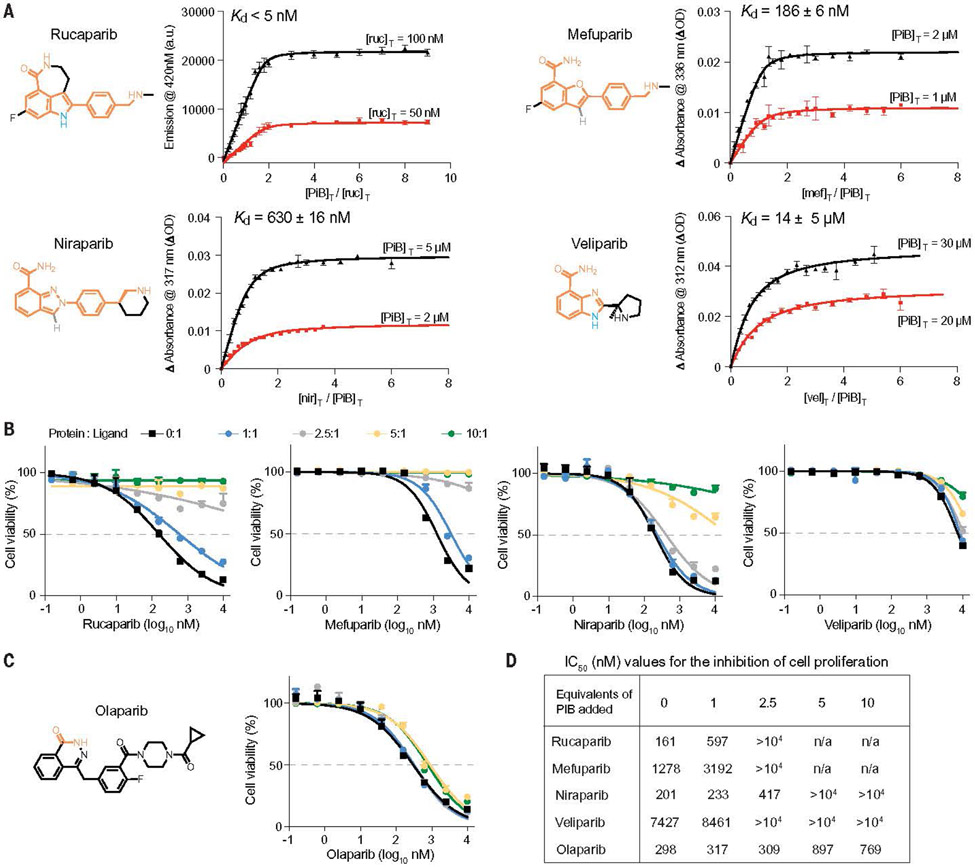

Fig. 3.

Spectral titrations and cell viability assay of PiB with PARPi. (A) The Kd values of various drugs for PiB as obtained from a global fit of a single-site binding model to the fluorescence or absorbance changes as a function of the concentration of PiB or drugs. The indicated wavelengths for the titration were chosen to maximize the difference in absorption for the free versus bound drug. (B) Growth assays in DLD-1 BRCA2-mutated cells showed that PiB alleviates the effects of rucaparib, mefuparib, niraparib, and veliparib toxicity in a dose-dependent manner. The PARP inhibitors were preincubated with PiB in media at room temperature for 5 min at multiple concentration ratios (protein:ligand) of 0:1, 1:1, 2.5:1, 5:1, and 10:1. (C) Cell viability assay as in Fig. 3B showing that PiB had no effect on the olaparib dose response. (D) Table showing IC50 values for the inhibition of cell proliferation by PARPi drugs in the presence of increasing mole ratios of added PiB protein.

Ultraviolet-visible absorption titrations showed that PiB and PiB′ also bound to the remaining ligands with affinities that grew increasingly weaker as the drugs’ structures diverged from rucaparib (Fig. 3A and fig. S12). PiB retained submicromolar affinity for mefuparib (Kd = 190 and 350 nM for PiB and PiB′, respectively) and niraparib (Kd = 600 and 550 nM). The corresponding Kd values of PiB and PiB′ were 14 and 24 mM, respectively, for the structurally divergent drug veliparib, and no binding was detected for the most divergent drug, Olaparib (fig. S13). This observed trend in binding affinity matched the order expected from the structural differences mentioned previously.

We next examined the in vitro stability and potency of PiB and PiB′ in serum and cellular assays. PiB and PiB′ were highly stable in human serum, as are other de novo proteins designed for medical applications (figs. S14 and S15) (3, 21). PARPi drugs potently inhibit the viability of cells with certain DNA repair deficiencies including loss-of-function mutations in BRCA2 (18). To determine whether PiB and PiB′ could attenuate the lethal effects of PARPi drugs, we measured their effects on the growth of BRCA2-mutated DLD-1 cells and SUM149 cells (22). Dose-response curves were first established in the absence of PiB, then the titration was repeated with PiB or PiB′ at varying protein/drug ratios for each PARPi drug concentration. The addition of a single equivalent of PiB or PiB′ resulted in a fourfold increase in the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value for rucaparib. Thus, PiB competes effectively for binding of rucaparib to human PARP1, an enzyme reported to bind rucaparib with a Kd of 0.1 to 1 nM in biochemical assays (23, 24) (Fig. 3, A, B, and D, and figs. S16 to S18). The potencies of PiB and PiB′ in the cellular assay were similar and decreased in the progression of rucaparib to mefuparib and niraparib to veliparib, which was in good agreement with the spectroscopic assays (Fig. 3, B and D, and figs. S16 to S18). Moreover, PiB and PiB′ did not appreciably change the cellular response to olaparib (Fig. 3, C and D, and figs. S16 to S18), which agreed with spectroscopic data that indicated that PiB and PiB′ do not bind this drug.

Structural and mutational validation of designs

The crystallographic structures of PiB′ were solved in the absence and presence of the four active compounds at 1.3- to 1.6-Å resolution (table S2). The protein’s conformation was in excellent agreement with the predicted Alpha Fold2 model, particularly near the binding site [a carbon (Ca) RMSD of the 60 surrounding residues was 0.2 to 0.5 Å] (Figs. 2A and 4, A and B; fig. S19; and table. S3). A similar degree of agreement (<0.5 Å RMSD) was observed comparing the experimental structure and the designed model. An important aspect of the design was that the binding site should be preorganized. Indeed, the binding pocket of PiB′ was nearly identical between the experimentally determined drug-free and drug-bound structures (0.2 to 0.5 Å Ca RMSD) (Fig. 4, B and C, and fig. S20). Moreover, the sidechains interacted precisely as predicted in the design of the rucaparib complex (Fig. 4B and fig. S20): Asp29 made a direct H-bonded salt bridge to the drug’s charged ammonium group; rucaparib’s carboxamide formed a two-coordinate hydrogen bond with Gln54, which in turn was stabilized by a second-shell network of H-bonds predicted in the design; and Asp131 formed a solvent-mediated H-bond to rucaparib’s indole NH group (Fig. 4B and fig. S20). A search of water-mediated Asp sidechains with related indole and imidazole sidechains showed that this bridging interaction is frequently found in the PDB (fig. S21).

Fig. 4.

The structure of drug-bound PiB′ agrees with the design. (A) The design model agreed well with the rucaparib-bound PiB′ crystal structure, with the binding site Ca RMSD range between 0.38 and 0.46 Å for the three monomers in the asymmetric unit. (B) The binding site of PiB′. A 2mFo-DFc composite omit map contoured at 1.6 s. The map was generated from a model that omitted coordinates of rucaparib. Overlay of the design (gray) and the structure (protein, orange; rucaparib, pink). The sidechains of the binding pocket in rucaparib-bound PiB′ agreed with the design. Asp131 interacts with the indole NH through a bridging water as in MD simulations. (C) The structure of drug-free PiB′ shows a preorganized open pocket filled with multiple waters, which are displaced in the drug-bound conformation. (D) Reversal of the three designed substitutions from the vdM optimization procedure led to lower binding affinity (higher Kd) for rucaparib by fluorescence emission titrations. (E) Alanine mutations of the direct binding residues decreased binding affinity confirmed by fluorescence emission titrations

The structures of mefuparib and niraprib bound to PiB′ showed a similar set of interactions as rucaparib did when bound to PiB′ (fig. S22). However, their aromatic five-membered azole rings lacked a H-bonding group to interact with Asp131, explaining their decreased affinity for the protein. As expected from its divergent compare their structural dynamics on this time scale. The simulations were performed on the designed models (instead of the crystallographic structures) to assess the use of MD as a predictor of experimental success. The protein backbone conformations were very stable for all four complexes. However, rucaparib’s designed binding pose was stable only in PiB and PiB′ (fig. S25A) (because PiB and PiB′ behave similarly in MD, we only discuss PiB): it retained its bivalent hydrogen bonding interaction to Gln54 (Fig. 5A), and Asp29 and Asp131 showed stable interactions with rucaparib’s indole NH and ammonium groups through direct and water-mediated hydrogen bonds, respectively (Fig. 5A). By contrast, PiB-1 and PiB-2 simulations deviated from rucaparib’s designed pose, and their key buried H bonds to Gln54 were broken within 50 ns in each of three independent calculations (fig. S25). Moreover, PiB shielded the apolar atoms in rucaparib more efficiently than PiB-1 and PiB-2, as determined from solvent-accessible surface area calculations within individual MD trajectories (fig. S26). Furthermore, MD simulations of PiB in complex with niraparib, veliparib, and mefuparib showed similar binding-site conformational stability as PiB-rucaparib over 2 ms (Fig. 5A and fig. S27). MD can thus help rationalize how interactions contribute to stability in predicted complexes and may be a useful tool in design. We next turned to alchemical and physical pathway methods to determine whether these methods could predict the absolute binding free energies for PiB and PiB′ directly from MD simulations, using the computational designs (rather than experimental structures) as the starting models. The alchemical transfer method (26, 27) was carried out by one of the authors who had no knowledge of the experimental results. This method has been shown to be comparable to other alchemical methodologies, such as Schrodinger’s Free Energy Perturbation plus (FEP+) (26) or Amber’s thermodynamic integration (27), given comparable sampling of the configurational space. An initial absolute binding free energy calculation was used to evaluate the energetic contributions of the fused-ring cores of the drugs and to ensure convergence of the calculations. An additional relative binding free energy calculation was performed to transform each core into the target ligand to estimate the contribution from noncore regions (fig. S28). Universally, the alchemical transfer method tended to overestimate the binding energy, possibly owing to having two sets of restraint potentials. However, this procedure correctly predicted the relative affinities of the four ligands (table S4).

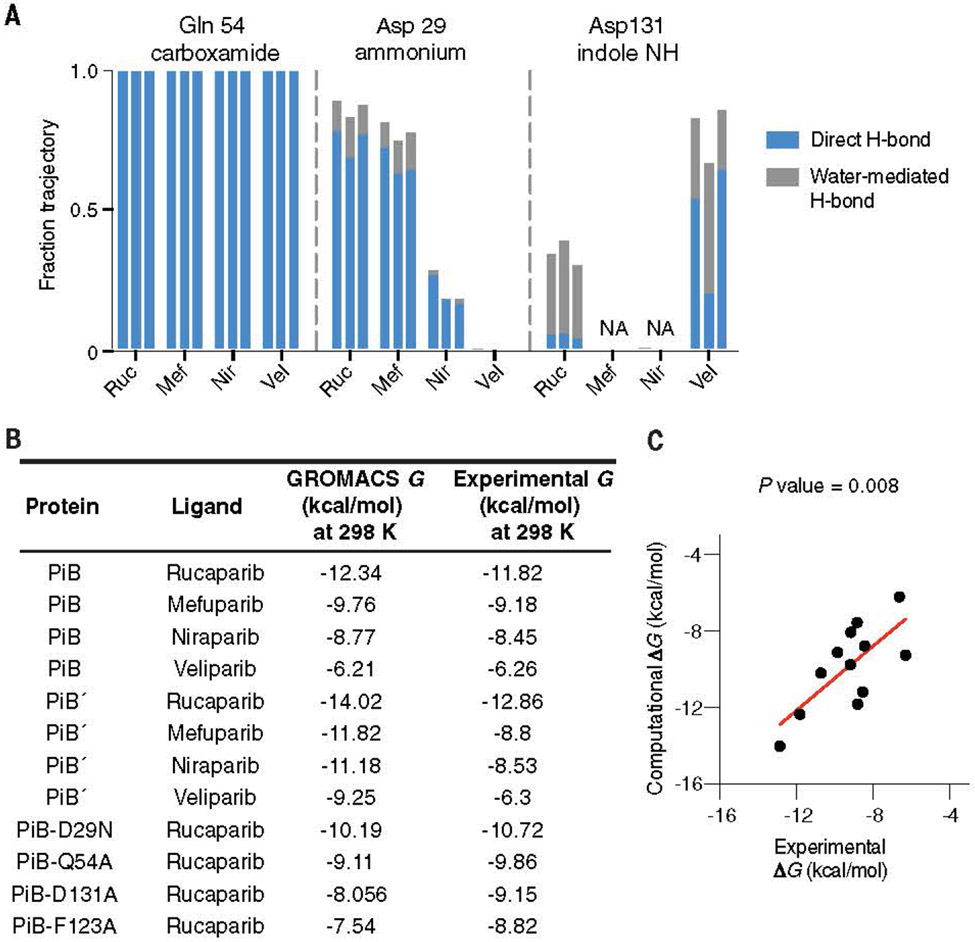

Fig. 5.

The MD simulations of PiB, PiB′, and mutants. (A) By using unbiased MD simulations in Amber, we calculated (in triplicate) the frequency with which the intermolecular hydrogen bonds formed between the protein scaffold and the bound drug molecule. PiB was found to form a hydrogen bond between Gln54 and the targeted drug carboxamide in 100% of all simulations for each drug complex. The charged ammonium groups of rucaparib and mefuparib interacted with Asp29 through a combination of direct and water-mediated hydrogen bonds, totaling to more than half of the full simulation time, which contrasts niraparib and veliparib’s inabilities to form equivalent hydrogen bonds (owing to changes in chemical structure around the ammonium tail of the ligand). In a small fraction of each rucaparib and veliparib trajectory, Asp131 engaged in water-mediated hydrogen bonds to the drugs. (B) By using biased simulations in GROMACS, we calculated the binding free energy (DG) for each ligand and found that ranked affinity for each drug was consistent with experimental results. (C) Comparison of DG from the GROMACS calculation with the experimental value from spectral titrations

We next used potential of mean force calculations, an orthogonal physical-pathway methodology (28), to compute absolute binding energies (figs. S29 to S33), and the results were in remarkably good agreement with those of the experiment (Fig. 5, B and C, and table. S5). The RMS error between the predicted and experimental values is 1.3 kcal/mol, and the correct rank order of affinities was observed. This error was close to the experimental error in the measurement of Kd for rucaparib. We also obtained very good agreement between computation and experimental results for a set of four mutants of PiB (Fig. 5, B and C, and table S5). This agreement bodes well for the use of alchemical and physical pathway–based binding free energy calculations to evaluate potential binding energies of de novo small-molecule binding proteins.

Discussion

In this study, we used structural bioinformatics to drive the de novo design of a high-affinity drug-binding protein. Molecular dynamics simulations accurately captured the trend in binding affinity for the series of drugs and predicted the role of water in binding. Our results portend a future in which artificial intelligence–enabled sampling of conformational and sequence spaces are seamlessly interfaced with physics-based models to design proteins and biomimetic polymers with precisely predefined binding affinity, specificity, and, given the intimate relation between binding and catalysis, catalytic properties. To achieve binding of complex polar molecules, sampling favorable geometries for ligand-protein interactions is essential. In this work, vdMs and COMBS were key to this achievement. Although they were used in conjunction with Rosetta sequence design, they could be easily adapted to improve sampling and/or scoring of a variety of recently developed protein-design algorithms based on diffusion models (3, 8-10). MD simulations of de novo proteins have only been occasionally used to provide insight into de novo protein design (29-33). However, by using this method, we were able to differentiate successful versus unsuccessful designs, suggesting that it should be helpful for prioritizing designs. Although we ran simulations for 2 ms, their essential features could be gleaned after 100 ns, suggesting that simulations on this timescale should be useful. Free energy calculations have not previously been applied to designed proteins. Although they are more computationally intensive and require more user-specified parameters, we obtained excellent quantitative agreement between computed and experimentally measured binding free energies using only the designed models as the input structures. These data demonstrate the possibility of designing proteins with high affinity (Kd < 5 nM) to small molecules by using fully rational criteria for design and “physics-based” force fields to evaluate the complexes.

Rucaparib binds to the human PARP1 enzyme with a Kd ranging from 0.1 to 1 nM depending on the experimental conditions (23, 24), which is close to the range observed for PiB and PiB′. Ligand efficiency is often used as a guiding rule in drug discovery to determine whether the affinity of a molecule of a given size is within a range typically seen in highly optimized small-molecule drugs and natural organic ligands for proteins (34, 35). As ligands become larger, they have more opportunities to form favorable interactions with their target proteins. Thus, the maximal affinity possible roughly scales with the size of a small molecule, and the ligand efficiency is defined as the free energy of binding (1 M standard state) divided by the number of heavy atoms in the ligand. Most drugs have ligand efficiency of around 0.3 kcal/ (mol × heavy atom count) (34, 35), although higher values are observed for highly optimized drugs such as rucaparib, which has a ligand efficiency of 0.5 kcal/(mol × heavy atom count). The ligand efficiency of a drug is similarly a good measure of how well optimized a de novo protein is for binding to a small molecule. The 0.5 kcal/(mol × heavy atom count) ligand efficiency of PiB is a considerable improvement over the 0.21 to 0.26 ligand efficiency of the first COMBS-designed apixaban binders, which demonstrates the importance of incorporating the design principles discussed above. With these and similar refinements, it should be increasingly possible to design high-affinity small molecule–binding proteins with predicable binding energetics for a variety of practical applications in sensing and pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the DeGrado lab for useful discussions and G. Meigs from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for helping with data collection.

Funding:

W.F.D. acknowledges research support from grants from the National Institutes of Health (2R35GM122603) and the National Science Foundation (grant NSF 2108660 and 2306190 NSF MCB BSF). N.F.P. acknowledges support from the NIH (R00GM135519). A.A. acknowledges research support from SPARC. We collected x-ray data on beamline 8.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source, which is supported by the DOE Office of Science User Facility under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231. Beamline 8.3.1 is also supported in part by the ALS-ENABLE program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant P30 GM124169-01.

Footnotes

Competing interests: A.A. is a cofounder of Tango Therapeutics, Azkarra Therapeutics, Ovibio Corporation, and Kytarro; a member of the board of Cytomx and Cambridge Science Corporation; a member of the scientific advisory boards of Genentech, GLAdiator, Circle, Bluestar, Earli, Ambagon, Phoenix Molecular Designs, Yingli, ProRavel, Oric, Hap10, and Trial Library; a consultant for SPARC, ProLynx, Novartis, and GSK; and holds patents on the use of PARPi held jointly with AstraZeneca from which he has benefited financially (and may do so in the future).

Data and materials availability: Coordinates and structure files have been deposited to the PDB with accession codes: 8TN1 (drug-free PiB′), 8TN6 (rucaparib-bound PiB′), 8TNB (mefuparib-bound PiB), 8TNC (niraparib-bound PiB′), and 8TND (veliparib-bound PiB′). Computational code and design scripts are available in the supplementary materials and at Zenodo (36). All other relevant data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Schreier B, Stumpp C, Wiesner S, Höcker B, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 106, 18491–18496 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang W, Lai L, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 45, 67–73 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polizzi NF, DeGrado WF, Science 369, 1227–1233 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas F et al. , ACS Synth. Biol 7, 1808–1816 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tinberg CE et al. , Nature 501, 212–216 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dou J et al. , Protein Sci. 26, 2426–2437 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dou J et al. , Nature 561, 485–491 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson JL et al. , Nature 620, 1089–1100 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingraham JB et al. , Nature 623, 1070–1078 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dauparas J et al. , Science 378, 49–56 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishna R et al. , bioRxiv, 2023.10.09.561603 [Preprint] (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee GR et al. , bioRxiv, 2023.11.01.565201 [Preprint] (2023). http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2023.11.01.565201 [Google Scholar]

- 13.An L et al. , bioRxiv, 2023.12.20.572602 [Preprint] (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dauparas J et al. , bioRxiv, 2023.12.22.573103 [Preprint] (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gainza P et al. , Nat. Methods 17, 184–192 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapovalov MV, Dunbrack RL Jr., Structure 19, 844–858 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jumper J et al. , Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lord CJ, Ashworth A, Science 355, 1152–1158 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koehl A, Jagota M, Erdmann-Pham DD, Fung A, Song YS, Pac. Symp. Biocomput 27, 22–33 (2022). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann SI, Nayak A, Gassner GT, Therien MJ, DeGrado WF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 143, 252–259 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva D-A et al. , Nature 565, 186–191 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hucl T et al. , Cancer Res. 68, 5023–5030 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudolph J, Roberts G, Luger K, Nat. Commun 12, 736 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas HD et al. , Mol. Cancer Ther 6, 945–956 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fersht A, Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science: A Guide to Enzyme Catalysis and Protein Folding (Macmillan, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L et al. , J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 2695–2703 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee T-S et al. , J. Chem. Inf. Model 60, 5595–5623 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chipot C, Annu. Rev. Biophys 52, 113–138 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barros EP et al. , J. Chem. Theory Comput 15, 5703–5715 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ulas G, Lemmin T, Wu Y, Gassner GT, DeGrado WF, Nat. Chem 8, 354–359 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gill M, McCully ME, Protein Eng. Des. Sel 32, 317–329 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chevalier A et al. , Nature 550, 74–79 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Childers MC, Daggett V, Mol. Syst. Des. Eng 2, 9–33 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hopkins AL, Keserü GM, Leeson PD, Rees DC, Reynolds CH, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 13, 105–121 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuntz ID, Chen K, Sharp KA, Kollman PA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 96, 9997–10002 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu L, Zenodo (2024). https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.10653015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.