Abstract

Objectives

Primaquine is essential for the radical cure of Plasmodium vivax malaria and must be metabolized into its bioactive metabolites. Accordingly, polymorphisms in primaquine-metabolizing enzymes can impact the treatment efficacy. This pioneering study explores the influence of monoamine oxidase-A (MAO-A) on primaquine metabolism and its impact on malaria relapses.

Methods

Samples from 205 patients with P. vivax malaria were retrospectively analysed by genotyping polymorphisms in MAO-A and cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) genes. We measured the primaquine and carboxyprimaquine blood levels in 100 subjects for whom blood samples were available on the third day of treatment. We also examined the relationship between the enzyme variants and P. vivax malaria relapses in a group of subjects with well-documented relapses.

Results

The median carboxyprimaquine level was significantly reduced in individuals carrying low-expression MAO-A alleles plus impaired CYP2D6. In addition, this group experienced significantly more P. vivax relapses. The low-expression MAO-A status was not associated with malaria relapses when CYP2D6 had normal activity. This suggests that the putative carboxyprimaquine contribution is irrelevant when the CYP2D6 pathway is fully active.

Conclusions

We found evidence that the low-expression MAO-A variants can potentiate the negative impact of impaired CYP2D6 activity, resulting in lower levels of carboxyprimaquine metabolite and multiple relapses. The findings support the hypothesis that carboxyprimaquine may be further metabolized through CYP-mediated pathways generating bioactive metabolites that act against the parasite.

Background

Plasmodium vivax is a widespread malaria species, contributing significantly to the overall malaria burden.1 The 8-aminoquinoline primaquine is a key drug used for the radical cure of P. vivax malaria, targeting latent hypnozoites in the liver.2 It is also recommended to interrupt Plasmodium falciparum transmission due to its activity against mature gametocytes.3 A major concern about the use of the 8-aminoquinolines such as primaquine or its synthetic analogue tafenoquine is related to the risk of oxidative haemolysis in individuals with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, which is estimated to affect around 8% of the population across P. vivax endemic countries.2

Primaquine is metabolized by two key enzymes in the liver, cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) and monoamine oxidase-A (MAO-A).4 Both the therapeutic efficacy and toxicity of primaquine (PQ) have been attributed to its hydroxylated metabolites (OH-PQm) produced mainly by CYP2D6.3–5 The oxidation and redox cycling of OH-PQm into its corresponding quinoneimine forms can produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and lead to parasite killing.6,7 MAO-A is implicated in the formation of the most predominant metabolite of primaquine, carboxyprimaquine.3,4,8 The oxidative deamination of primaquine through MAO-A pathway is responsible for its short elimination half-life (∼4–6 h).9 Albeit carboxyprimaquine does not show direct activity against the parasite, there is evidence that carboxyprimaquine may be metabolized through phase I CYP-mediated reactions with concomitant formation of hydroxylated and quinoneimine metabolites.9

The MAO-A proximal promotor sequence is polymorphic, containing a variable number of tandem repeat polymorphisms (uVNTR). It consists of a 30 bp sequence, present in 2–5 copies, which has been shown to influence transcription.10MAO-A is an X-linked gene, meaning that males are considered hemizygotes. While the role of X chromosome inactivation in regulating MAO-A levels remains uncertain, there is evidence of higher MAO-A activity in heterozygous individuals.11 The gene CYP2D6 is highly diverse, with over 150 defined alleles and a wide range of phenotypes, from complete dysfunction to ultrarapid metabolism. Previous studies have shown that low-activity CYP2D6 variants reduce the hypnozoitocidal efficacy of primaquine, resulting in repeated relapses in P. vivax malaria.3,12,13 Here, we interrogated to what extent MAO-A variants could contribute to the primaquine efficacy.

Methods

Samples from 205 subjects infected by P. vivax were retrospectively analysed. The first part included 100 subjects from Boa Vista, Roraima State, who were mostly involved in gold mining activities and had a high risk of infection by Plasmodium spp. Their blood levels of primaquine and carboxyprimaquine were measured on the third day of treatment. We also evaluated the association between the enzymatic variants and relapses in 105 subjects residing in areas with unstable transmission or no active malaria transmission: Souza in Minas Gerais State (n = 16), Cuiabá in Mato Grosso State (n = 40) and Porto Velho in Rondônia State (n = 49). Most samples were from cross-sectional studies, except for Porto Velho, which also included samples from a drug efficacy study. The study areas and participants have been described previously14–16 and are described in the Supplementary Data. The ethical and methodological aspects of the study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Research Involving Human Subjects of Institute René Rachou/Fiocruz (report no. 2.803.756). All participants signed a written informed consent form, and the next of kin, caretakers or guardians signed on behalf of minors/children enrolled in the study.

Most participants were adults with a median age of 34 years (IQR, 25–46); none reported antimalarial use in the preceding 30 days or a history of chronic conditions (such as severe cardiac, hepatic or renal disorders). All patients were treated with a combination of a schizonticidal drug such as chloroquine (total dose of 25 mg/kg over 3 days) and primaquine (total dose of 3.5 mg/kg over 7 days).

The number of P. vivax malaria episodes for each participant was obtained from the Epidemiological Surveillance System for Malaria (SIVEP-Malaria). P. vivax recurrence was defined as a new episode diagnosed microscopically, occurring within an interval ranging from 29 to 180 days after the initial episode. For participants of the drug efficacy trial, parasite relapses were assayed within 63 days of follow-up.

The uVNTR polymorphism in MAO-A was genotyped by conventional PCR followed by fragment analysis with 1 bp precision through capillary electrophoresis.10 Heterozygous women carrying both high- and low-expression MAO-A alleles were classified as extensive metabolizers. CYP2D6 polymorphisms (C1584G, C100T, C1023T, G1846A, C2580T, G2988A, G3183A, G4180C and 2615_2617delAAG) and the copy number of the gene were assayed by qPCR.13 These are common genetic variants in Brazilians associated with reduced drug metabolism.

Primaquine and carboxyprimaquine were quantified on the third day of treatment using a reversed-phase HPLC system with a diode array detector (Flexar System—Perkin Elmer Inc., Boston, MA, USA). The measurement involved liquid–liquid extraction from blood spots on filter paper, following the protocol previously described.17

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All tests were two-sided, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

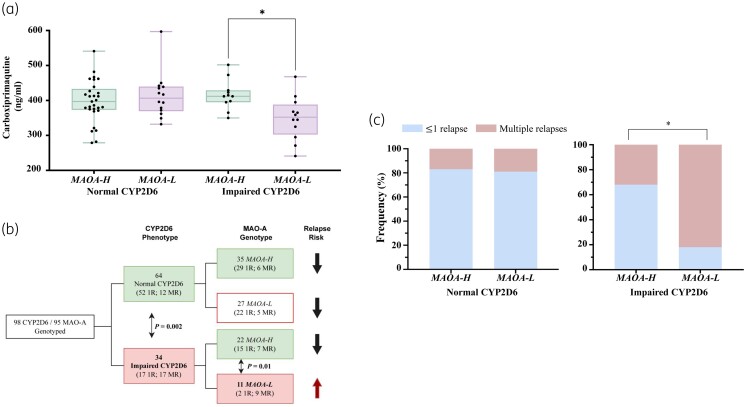

Initially, we measured the primaquine and carboxyprimaquine blood levels in 100 subjects for whom blood samples were available on the third day of treatment. Among them, 30% had impaired CYP2D6 activity inferred from genotype data (AS ≤ 1.0), and 31% carried low-expression MAO-A variants. No differences in primaquine levels were documented between high- and low-expression MAO-A variants [median = 179.0 ng/mL (IQR = 146.0, 232.0) and 188.0 ng/mL (119.0, 217.5), respectively, P = 0.907] in the context of impaired CYP2D6 activity (Figure S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). Interestingly, the median carboxyprimaquine level was significantly reduced in the specific group of subjects carrying low-expression/activity alleles in both MAO-A and CYP2D6 (P = 0.034) (Figure 1a). These results point to a potential gene–gene interaction where the status of the MAO-A promoter region is critical, prompting the working hypothesis of a nuclear receptor-mediated mechanism.18

Figure 1.

Drug blood levels and frequency of P. vivax malaria relapses according to MAO-A and CYP2D6 status. (a) Association between carboxyprimaquine blood levels and genetic status of CYP2D6 and MAO-A. Carboxyprimaquine was measured on Day 3 after the initiation of treatment in blood samples collected from participants from Boa Vista, Roraima State. The enzyme activity of MAO-A and CYP2D6 was inferred as follows: normal CYP2D6, normal/ultrarapid metabolizers (AS > 1·0); impaired CYP2D6, poor/intermediate metabolizers (AS ≤ 1·0); MAOA-H, MAO-A high expression; MAOA-L, MAO-A low expression. (b) Flowchart representing the number of individuals successfully genotyped in this study. For relapse analysis, we analysed individuals living in areas of unstable or without active transmission and subjects followed up for 2 months as part of a drug efficacy trial. (c) Frequency of malaria relapses among groups of individuals according to CYP2D6 and MAO-A activity status. ≤1R, non- or single relapse; MR, multiple relapses. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

We additionally examined the relationship between the enzyme variants and P. vivax malaria relapses in a group of 105 individuals with well-documented relapses. Among them, 35% had impaired CYP2D6 activity (AS ≤ 1), and 38% of subjects carried the low-expression MAO-A variants (Table S1). In terms of therapy efficacy, impaired CYP2D6 activity was associated with multiple relapse episodes of P. vivax, when compared with the group of extensive/ultra-rapid CYP2D6 metabolizers [50% (17 out of 34) versus 19% (12 out of 64), P = 0.002] (Figure 1b), confirming the well-established importance of CYP2D6 activity and primaquine performance.

We next investigated whether the lower levels of carboxyprimaquine observed among patients carrying low-expression MAO-A alleles plus impaired CYP2D6 would impact primaquine efficacy. This group, in fact, experienced significantly more P. vivax relapses (P = 0.010) (Figure 1c), a relatively surprising observation, as carboxyprimaquine is generally considered pharmacologically inactive in malaria therapy. The low-expression MAO-A status was not associated with malaria relapses when CYP2D6 had normal activity (P > 0.999), suggesting that the putative carboxyprimaquine contribution is essentially irrelevant when the CYP2D6 pathway is fully active.

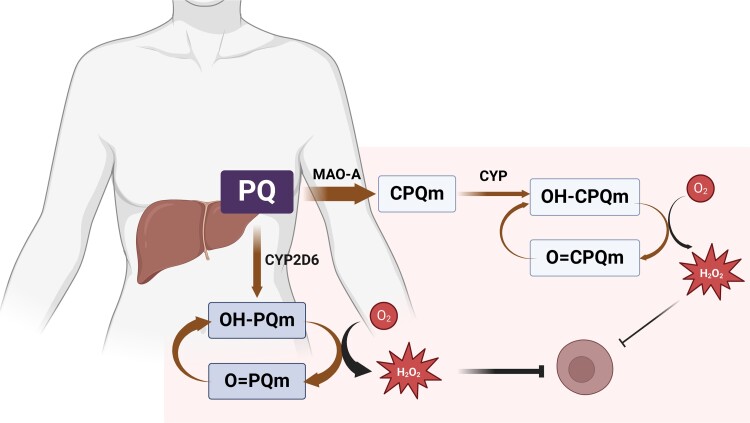

For the moment, we propose as a hypothesis that carboxyprimaquine does have a role of protection by producing its own set of quinoneimines that kill the parasite through redox cycling and oxidative damage, ultimately impacting the drug’s anti-hypnozoite activity (Figure 2). The first evidence for hydroxylation of carboxyprimaquine followed by the formation of quinoneimines came from in vitro analysis using primary human hepatocytes.19 More recently, the presence of these compounds was confirmed by in vivo phenotyping of primaquine metabolites in plasma and urine from healthy human volunteers.9 Carboxyprimaquine metabolite production is smaller, but this is likely to be partially offset by a more extensive exposure, primarily considering carboxyprimaquine longer elimination half-life (∼15 h). Thus, less MAO-A activity would lead to a decreased rate of metabolite production and, hence, decreased protection. Nevertheless, this effect is likely to be secondary in the presence of fully active CYP2D6 activity, with primaquine metabolism through the MAO-A pathway alone not sufficient to produce enough active metabolites for effective protection against the parasite and prevent P. vivax relapses.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism of action of primaquine and carboxyprimaquine against liver hypnozoites. Primaquine (PQ) is metabolized into hydroxylated PQ metabolites (OH-PQm) by CYP2D6. OH-PQm undergoes spontaneous oxidation to quinoneimines (O = PQm) with concomitant generation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Primaquine is converted to carboxyprimaquine, the most abundant plasma metabolite, mainly by MAO-A. Carboxyprimaquine produces its own set of quinoneimines that kill the parasite through redox cycling and oxidative damage. Created with BioRender.com. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Our study has two main limitations. First, we could evaluate only a few subjects with altered activity of both enzymes (n = 11). A larger study is necessary to further elucidate the relationships between the spectrum of enzyme activities and relapses in P. vivax malaria. Second, we could not follow a standard approach related to the time of blood collection after drug intake, which may have contributed to the high variability observed in drug blood levels among subjects. Nonetheless, carboxyprimaquine level measurements should be less affected due to its longer elimination half-life.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we present data supporting the potential importance of MAO-A promoter polymorphism as a factor to be considered, in addition to the well-established importance of CYP2D6 pharmacogenetics in primaquine efficacy. Our findings can have a significant impact on malaria epidemiology, considering that approximately 35% of subjects may show low expression of MAO-A or impaired CYP2D6.2,10 Finally, it remains to be evaluated how individuals with genetic deficiency of G6PD can be affected by these enzyme variants concerning the risk of haemolytic toxicity of primaquine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study. The authors thank Renata de Barros Ramos Rosa, Viviane Cristina Fernandes dos Santos from FIOCRUZ-MG and the Program for Technological Development in Tools for Health-PDTISFIOCRUZ for the use of the Sanger Sequencing Facility (RPT01E) and Real-Time PCR Facility (RPT09D) at René Rachou Institute. M.C.S.B.P. thanks René Rachou Institute for scholarship support. M.C.S.B.P., D.F.R. and Y.E.A.R.S. thank the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES) for scholarship support (Finance Code 001) and the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde do Instituto René Rachou. M.C.S.B.P. and Y.E.A.R.S. thank the Programa PrInt-Fiocruz-CAPES for scholarship support.

Contributor Information

Maria Carolina Silva De Barros Puça, Molecular Biology and Malaria Immunology Research Group, Instituto René Rachou, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Danielle Fonseca Rodrigues, Molecular Biology and Malaria Immunology Research Group, Instituto René Rachou, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Yanka Evellyn Alves Rodrigues Salazar, Molecular Biology and Malaria Immunology Research Group, Instituto René Rachou, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Jaime Louzada, Universidade Federal de Roraima, Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazil.

Cor Jesus Fernandes Fontes, Universidade Federal do Mato Grosso, Faculdade de Medicina, Departamento de Medicina Interna, Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil.

André Daher, Vice Presidency of Research and Biological Collections, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Dhélio Batista Pereira, Centro de Pesquisa em Medicina Tropical de Rondônia, CEPEM, Porto Velho, Rondônia, Brazil.

José Luiz Fernandes Vieira, Universidade Federal do Pará, Faculdade de Farmácia, Laboratório de Toxicologia, Belém, Pará, Brazil.

Luzia Helena Carvalho, Molecular Biology and Malaria Immunology Research Group, Instituto René Rachou, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Cristiana Ferreira Alves de Brito, Molecular Biology and Malaria Immunology Research Group, Instituto René Rachou, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

José Pedro Gil, Department of Microbiology, Tumor and Cell biology, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden.

Tais Nobrega de Sousa, Molecular Biology and Malaria Immunology Research Group, Instituto René Rachou, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Department of Microbiology, Tumor and Cell biology, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Swedish Research Council Grant (Grant ref. 200075/2022-5). T.N.S., L.H.C. and C.F.A.B. are CNPq Research Productivity fellows. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Transparency declarations

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: T.N.S. Formal analysis: M.C.S.B.P., C.F.A.B., T.N.S. and J.P.G. Funding acquisition: T.N.S. and C.F.A.B. Investigation: T.N.S., C.F.A.B. and J.P.G. Resources: C.F.A.B., J.L.F.V., D.B.P., J.L., A.d., L.H.C. and T.N.S. Methodology: M.C.S.B.P., D.F.R., Y.E.A.R.S and J.L.F.V. Writing—original draft: M.C.S.B.P. and T.N.S. Writing—review and editing: T.N.S., M.C.S.B.P., C.F.A.B. and J.P.G.

Supplementary data

Figure S1 and Table S1 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. WHO . World Malaria Report. Geneva, Swiss: 2021. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2021

- 2. Baird JK, Battle KE, Howes RE. Primaquine ineligibility in anti-relapse therapy of Plasmodium vivax malaria: the problem of G6PD deficiency and cytochrome P-450 2D6 polymorphisms. Malar J 2018; 17: 42. 10.1186/s12936-018-2190-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pybus BS, Marcsisin SR, Jin Xet al. The metabolism of primaquine to its active metabolite is dependent on CYP 2D6. Malar J 2013; 12: 212. 10.1186/1475-2875-12-212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pybus BS, Sousa JC, Jin Xet al. CYP450 phenotyping and accurate mass identification of metabolites of the 8-aminoquinoline, anti-malarial drug primaquine. Malar J 2012; 11: 259. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zanger UM, Turpeinen M, Klein Ket al. Functional pharmacogenetics/genomics of human cytochromes P450 involved in drug biotransformation. Anal Bioanal Chem 2008; 392: 1093–108. 10.1007/s00216-008-2291-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vásquez-Vivar J, Augusto O. Hydroxylated metabolites of the antimalarial drug primaquine. Oxidation and redox cycling. J Biol Chem 1992; 267: 6848–54. 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)50504-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vásquez-Vivar J, Augusto O. Oxidative activity of primaquine metabolites on rat erythrocytes IN vitro and in vivo. Biochem Pharmacol 1994; 47: 309–16. 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90022-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Constantino L, Paixão P, Moreira Ret al. Metabolism of primaquine by liver homogenate fractions. Exp Toxicol Pathol 1999; 51: 299–303. 10.1016/S0940-2993(99)80010-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Avula B, Tekwani BL, Chaurasiya NDet al. Metabolism of primaquine in normal human volunteers: investigation of phase I and phase II metabolites from plasma and urine using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Malar J 2018; 17: 294. 10.1186/s12936-018-2433-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sabol SZ, Hu S, Hamer D. A functional polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase A gene promoter. Hum Genet 1998; 103: 273–9. 10.1007/s004390050816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsusue A, Kubo S, Ikeda Tet al. VNTR polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase A promoter region and cerebrospinal fluid catecholamine concentrations in forensic autopsy cases. Neurosci Lett 2019; 701: 71–6. 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bennett JW, Pybus BS, Yadava Aet al. Primaquine failure and cytochrome P-450 2D6 in Plasmodium vivax malaria. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1381–2. 10.1056/NEJMc1301936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Silvino ACR, Kano FS, Costa MAet al. Novel insights into Plasmodium vivax therapeutic failure: CYP2D6 activity and time of exposure to malaria modulate the risk of recurrence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64: e02056-19. 10.1128/AAC.02056-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ceravolo IP, Sanchez BAM, Sousa TNet al. Naturally acquired inhibitory antibodies to Plasmodium vivax Duffy binding protein are short-lived and allele-specific following a single malaria infection. Clin Exp Immunol 2009; 156: 502–10. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03931.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Silvino ACR, Costa GL, de Araújo FCFet al. Variation in human cytochrome P-450 drug-metabolism genes: a gateway to the understanding of Plasmodium vivax relapses. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0160172. 10.1371/journal.pone.0160172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Daher A, Aljayyoussi G, Pereira Det al. Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of chloroquine and artemisinin-based combination therapy with primaquine. Malar J 2019; 18: 325. 10.1186/s12936-019-2950-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salazar YEAR, Louzada J, Puça MCSdBet al. Delayed gametocyte clearance in Plasmodium vivax malaria is associated with polymorphisms in the cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2024; 68: e0120423. 10.1128/aac.01204-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen K. Organization of MAO A and MAO B promoters and regulation of gene expression. Neurotoxicology 2004; 25: 31–6. 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00113-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Avula B, Tekwani BL, Chaurasiya NDet al. Profiling primaquine metabolites in primary human hepatocytes using UHPLC-QTOF-MS with 13 C stable isotope labeling. J Mass Spectrom 2013; 48: 276–85. 10.1002/jms.3122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.