Abstract

The innate immune response of Drosophila melanogaster is governed by a complex set of signaling pathways that trigger antimicrobial peptide (AMP) production, phagocytosis, melanization, and encapsulation. Although immune responses against both bacteria and fungi have been demonstrated in Drosophila, identification of an antiviral response has yet to be found. To investigate what responses Drosophila mounts against a viral infection, we have developed an in vivo Drosophila X virus (DXV)-based screening system that identifies altered sensitivity to viral infection by using DXV's anoxia-induced death pathology. Using this system to screen flies with mutations in genes with known or suggested immune activity, we identified the Toll pathway as a vital part of the Drosophila antiviral response. Inactivation of this pathway instigated a rapid onset of anoxia induced death in infected flies and increases in viral titers compared to those in WT flies. Although constitutive activation of the pathway resulted in similar rapid onset of anoxia sensitivity, it also resulted in decreased viral titer. Additionally, AMP genes were induced in response to viral infection similar to levels observed during Escherichia coli infection. However, enhanced expression of single AMPs did not alter resistance to viral infection or viral titer levels, suggesting that the main antiviral response is cellular rather than humoral. Our results show that the Toll pathway is required for efficient inhibition of DXV replication in Drosophila. Additionally, our results demonstrate the validity of using a genetic approach to identify genes and pathways used in viral innate immune responses in Drosophila.

Keywords: Drosophila X virus, innate immunity, virus, Dif

The innate immune system plays an important role in immune responses against multiple pathogens in various species. In mammalian systems, the innate immune system provides the first line of defense against pathogens before activation of acquired immune responses. In insects, the entire immune system is innate and has been shown to respond to bacteria, fungi, parasites, and, as our results show, viruses. Because of the striking homology between the Drosophila and mammalian innate immune systems, one example being the Toll pathway, Drosophila has become the model system of choice for the study of innate immune responses.

Because of the nonvariable nature of innate immune responses, activation primarily occurs by recognition of distinct pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are shared by multiple pathogens (1). In mammalian systems, multiple Toll-like receptors (TLRs) have been found that activate the immune response via detection of a range of PAMPs including: lipopoly-saccharide (TLR4), lipoproteins (TLR2), dsRNA (TLR3), flagellin (TLR5), CpG DNA (TLR9), and various antiviral compounds (TLR7) (2, 3). In addition to these PAMPs, TLRs can also be activated by recognition of “self” patterns normally present inside of cells such as heat shock proteins and uric acid (4, 5). When activated, these TLRs are involved in the expression of inflammatory cytokines and costimulatory molecules that activate the adaptive immune system (3). In contrast, of the 10 TLRs identified in Drosophila melanogaster, only one has been definitively identified as playing a role in innate immunity. Additionally, unlike the limited PAMP sets recognized by each mammalian TLR, this one Drosophila Toll is able to respond to bacterial, fungal, and viral infections (6). Drosophila mounts an immune response against these pathogens through the use of both humoral and cellular responses. The identified humoral response in Drosophila consists primarily of the Toll pathway and the IMD pathway, which regulate antimicrobial peptide (AMP) expression in the fat body, a flattened tissue in the fly abdomen that is functionally equivalent to the mammalian liver (7, 8).

The Toll pathway is activated by Gram+ bacterial and fungal infections via binding of PAMPs to peptidoglycan receptor proteins (PGRPs) (-SA,-SD) and Gram- binding proteins (1, 3, 9, 10). This binding initiates a serine protease cascade that cleaves Spätzle, the ligand of the Toll transmembrane receptor protein (10, 11). Once this cleaved form of Spätzle is bound, Toll signaling directs the phosphorylation and degradation of Cactus, an IκB-like protein that inhibits the NF-κB like transcription factors Dorsal and Dif (12). Destruction of Cactus allows translocation of these transcription factors to the nucleus, causing a rapid increase in expression of multiple AMPs (11-13). The Toll pathway also plays an important role in both maternal effect embryonic patterning and larval hematopoiesis (14, 15). This hematopoietic developmental effect may be significant for immune responses as hemocytes mediate nearly all cellular immune responses, including phagocytosis, melanization, and encapsulation, and also signal the fat body to initiate AMP production during infection.

The IMD pathway is activated in a similar fashion to the Toll pathway. It is believed that the IMD pathway is triggered by interaction between the Gram- bacteria PAMP diaminopimelic acid peptidoglycan and the PGRP-LC transmembrane receptor (10, 16). Imd, a death domain adaptor protein with significant similarities to the mammalian Receptor Interaction Protein, is then recruited by and binds to dFadd (17, 18). dFadd interacts with the caspase Dredd, which in turn associates with and is thought to cleave phosphorylated Relish, a bipartite NF-κB-type transcription factor (18-20). Relish is phosphorylated by the Drosophila IκB kinase complex, which is activated by the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase Tak1 in an Imd-dependent manner (21-24). The cleaved N-terminal domain of Relish then translocates to the nucleus, where it regulates the transcription of various immune response-related genes (20).

Inactivation of either these pathways results in increased susceptibility to select microorganisms. Inactivation of the Toll pathway, for example, eliminates induction of the antifungal peptide Drosomycin and increases susceptibility to fungal and Gram+ infections. However, these flies are able to induce the antibacterial peptide Diptericin normally and can resist Gram- infections (12, 25-27).

In addition to bacterial and fungal pathogens, multiple viruses that infect Drosophila have been identified. Drosophila C virus, for instance, has been studied, and its pathogenesis has been examined in depth (28). Another virus, Drosophila X virus (DXV), is a member of the Birnavirus family and has an icosahedral nucleocapsid and bisegmented dsRNA genome (Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Despite extensive research into DXV's genome, many of its pathological effects in Drosophila have yet to be thoroughly defined (29, 30). Infection was shown to induce anoxia sensitivity and eventual death, but the specific cause was unknown (30).

In our studies, we have developed several assays to identify mutant lines with altered sensitivity to DXV infection. Additionally, we find that the Toll pathway is an essential component of viral resistance in flies. Dif1 mutants, which do not have a functional Toll pathway, develop higher DXV titers and succumb to death by anoxia more rapidly then WT flies. Tl10b, a Toll gain-of-function mutant, succumbs to similar early onset death but has a reduced DXV titer. These results provide an example of an identified Drosophila innate immune related pathway playing a role in viral susceptibility. Our results suggest that the Toll pathway is able to reduce replication of DXV and possibly other viral pathogens. Further characterization of this pathway in relation to viral resistance should yield insight into this branch of the innate immune response in Drosophila.

Materials and Methods

Fly Rearing. All flies used were 3- to 5-day-old adults reared at 22°C on standard yeast/agar media. OregonR flies were used as WT. Fly lines were obtained from D. Ferrandon (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Strasbourg), B. Lemaitre (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Gif-sur-Yvette, France), K. Anderson (Sloan-Kettering Institute, New York), and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center.

Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time PCR. RNA was isolated from adult flies by homogenizing flies in STAT-60 buffer according to the manufacturer's protocol (Isotex Diagnostics). Quantitatitive RT-PCR was then performed by using a PE Biosystems 5700 GeneAmp Sequence detection system and Invitrogen LUX Primers. Specific LUX primers were designed against DXV strand B and used to quantify relative viral titer. LUX primer sets were also designed to measure AMP gene expression. Ribosomal protein 49 was used as a control in all experiments.

The following primers were used: for DXV, left primer, GGAGTTGAAGCCACGGTTTG, right primer, GACGATCTTGCCAGTTGGCTCATCG[FAM]C; for AttacinA, left primer, CACCAGATCCTAATCGTGGCCCTGG[FAM]G, right primer, ACGCGAATGGGTCCTGTTGT; for Cecropin A1, left primer, TTTCGTCGCTCTCATTCTGG, right primer, GACAATCCCACCCAGCTTCCCGATTG[FAM]C; for Defensin, left primer, CCACATGCGACCTACTCTCCA, right primer, GACAAGAACGCAGACGGCCTTG[FAM]C; for Diptericin, left primer, TTTGCAGTCCAGGGTCACCA, right primer, CACGAGCCTCCATTCAGTCCAATCTCG[FAM]G; for Drosocin, left primer, GTGAGGCGCGAGGCACT, left primer, CACCTGGATGGCAGCTTGAGTCAGG[FAM]G; for Drosomycin, left primer, ATCCTGAAGTGCTGGTGCGAAGGA[FAM]G, right primer, ACGTTCATGCTAATTGCTCATGG; for Metchni-kowan, left primer, CAGTGCTGGCAGAGCCTCAT, right primer, CAACCATAAATTGGACCCGGTCTTGG[FAM]TG; for rp49, left primer, CACGATAGCATACAGGCCCAAGATCG[FAM]G, right primer, GCCATTTGTGCGACAGCTTAG. All primers are listed in 5′ to 3′ orientation.

Histology. Five days after eclosion, flies were injected with DXV and kept at 25°C. Flies were fixed in a FAAG solution [80% ethanol/4% formaldehyde/5% acetic acid/1% glutaraldehyde (EM grade, 25%)], dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Staining of DXV was performed by application of primary antibody consisting of anti-DXV antiserum to sections at 1:1,000 dilution and left overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed in 1% PBSB and incubated in a 1:2,000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 2 h at 25°C. After washing in PBS, sections were stained with DAB peroxidase-based indirect detection protocol (31). TUNEL staining was performed with the Tdt-FragEL DNA Fragmentation Detection kit from Calbiochem as per the manual. Alternate sections of the fly stained with TUNEL were also immunostained against DXV.

Stress Experiments. Flies were exposed to heat (42°C), cold (4°C), or desiccation for 15 min at 3, 5, 7, and 10 days after infection. Assessment of survival was done 2 h after stress treatment.

Infection Method. For viral infection, flies were injected by using a Drummond Nanoject or WPI PicoPump with ≈30 nl of a 105-fold dilution of purified DXV. Purified DXV was generated from an initial stock provided by Peter Dobos (University of Guelph, Guelph, Canada). Bacterial infection was done with 30 nl of an overnight culture of Escherichia coli washed once and resuspended in PBS. Control injections were done with double-distilled H2O.

Anoxia Sensitivity Survival Assay. Anoxia sensitivity survival assaying was performed by a 15-min CO2 exposure in a sealed chamber. Flies were then assayed for survival 2 h after treatment. For genetic screening, flies were assayed at 3, 7, and 10 days after infection (dpi). For WT survival curves, flies were assayed every 24 hours after infection. Sample size was no fewer than 100 flies per line tested. Flies were transferred to new vials every 3 days.

Further Details. For further details, see Supporting Text, Figs. 6 and 7, and Table 1, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Results

DXV Infection in WT Drosophila. WT Drosophila infected with DXV die 20-25 dpi. It was previously noted that anoxia stress results in death at ≈7 dpi. We found that this anoxia phenotype could be used as a reproducible assay for rapid identification of mutations that influence the viral immune response. We initially generated survival curves for WT Drosophila mock injected, injected with distilled H2O, and injected with DXV (Fig. 1A). Flies injected with DXV displayed a dramatic increase in anoxia sensitivity induced death 6 dpi in comparison to the control groups. This increase in death was found to be anoxia specific and not the result of a general stress response, because DXV-infected Drosophila displayed no alteration in survival in response to heat, cold, or dehydration stresses over the course of 10 days (data not shown). The specific and reproducible nature of this assay allowed for its use in identifying mutant Drosophila lines with altered sensitivity to viral infection.

Fig. 1.

DXV pathology in Drosophila WT adults. (A) The anoxia sensitivity phenotype correlates with injection of DXV into WT flies, with a dramatic drop in survival at 6 dpi. More than 200 flies were used for each survival curve. Error bars show one standard deviation. (B) Viral titer, as measured by quantitative RT-PCR, shows a rapid increase in DXV. Each point represents a reaction from a pooled sample of 10 flies. Error bars show one standard deviation. (C) Immunostaining of DXV in sagittal sections of WT whole flies after injection with water or DXV. The head is oriented to the right. Immunostaining of H2O injection control shows no significant background. DXV infected samples show a steady spread of virus through entire WT organism over time. (D) DXV immunostaining and TUNEL staining of sagittal sections of a 7 dpi Drosophila showing cell death in the tissue where DXV antigens are detected. No TUNEL staining was observed in H2O-injected flies. Sections are ≈25 μm apart in the same organism.

To determine whether the antiviral response was inhibiting viral replication, reducing pathogenic effects, or both, we examined a time course of viral titer in WT flies. Because of technical limitations, we were unable to use plaque assays with DXV and S2 cells for viral titer measurements. As an alternate method, quantitative RT-PCR against a 62-bp region of DXV strand B was used for determination of relative titer increase. In WT Drosophila infected with DXV, viral titer was found to increase logarithmically before slowing to a near linear rate of increase (Fig. 1B). The timing of the increase in titer correlates with the increase in anoxia-induced death in infected WT flies.

To examine tissue specificity of a DXV infection, we examined paraffin tissue sections of DXV-infected WT Drosophila with an anti-DXV polyclonal antibody, which recognizes DXV's capsid proteins (Fig. 5). We observed initial punctate staining at 4 dpi followed by rapid viral spread throughout the organism by 7 dpi (Fig. 1C). As with viral titer levels, we found that increased viral dispersal correlates with the onset of anoxia-induced death. We also find that cell death observed with TUNEL assay occurs in the same location where DXV staining is observed (Fig. 1D). It appears that some selectivity may occur during the initial stages of DXV infection, but by the time that anoxia-induced death occurs, the virus has pervaded multiple tissues, and it is not clear whether infection of a specific tissue is the cause of this increased anoxia-induced death.

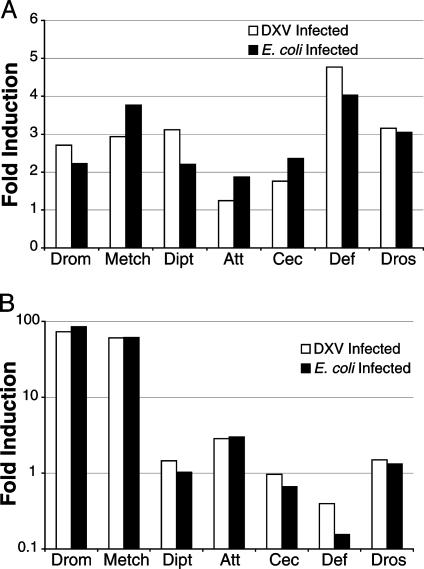

Antimicrobial Peptide Effects on Viral Resistance. Previous work has shown that AMP gene expression is increased in response to bacterial and fungal infections in Drosophila. This expression depends on activation of the Toll and/or IMD pathways, so AMP expression has been used as a means to determine whether these pathways are activated during infection. To determine whether DXV infection induces expression of known Drosophila AMPs, we examined the expression levels of seven Drosophila AMPs by RT-PCR at 2 and 24 h after viral infection. We used E. coli infection, a known activator of the Toll and IMD pathways, as a control to compare the levels of AMP gene expression in viral infection to those found in a Gram- bacterial infection. Wounding controls were used for baseline levels of AMP expression. We found that both DXV and E. coli infection induce similar expression levels of the Toll and IMD pathway target genes at both time points (Fig. 2). This finding suggests that the Toll and IMD signaling pathways are both activated in response to viral infection.

Fig. 2.

AMP expression levels in DXV-infected flies measured by quantitative RT-PCR. (A) Two hours after DXV injection. (B) Twenty-four hours after DXV injection. No significant difference between the DXV- and E. coli-infected groups exists, with even the greatest difference being under a 1-fold alteration. Data are representative of three experiments.

Because of this up-regulation of AMP expression during viral infection, we wanted to determine whether AMPs were acting as effectors in an antiviral response. To do this, we examined the effect of constitutive expression of various singly expressed AMPs in an immunodeficient background (32). Flies of this genotype were generated through the use of the UAS-Gal4 system in an IMD and Toll pathway deficient background (imd;spz) (33). Two fly lines deficient in both the Toll and IMD pathways, one containing the daughterless Gal4 driver (imd; daGal4 spz) and one containing a UAS-promoted AMP (UAS-AMP imd; UAS-AMP spz), were crossed to generate flies in which the UAS-promoted AMP is driven by the daughterless Gal4 driver. The daughterless Gal4 driver expresses GAL4 constitutively in all tissues. Attacin, Cecropin, Defensin, Diptericin, Drosomycin, Drosocin, and Metch-nikowin UAS promoted fly lines were all tested (32). Offspring were infected with DXV and assayed for anoxia survival at 3, 7, and 10 dpi. Of the seven AMPs analyzed in triplicate, <10% difference (≤10%) from the DXV effect on the imd;spz parental lines was observed (Fig. 6). Additionally, viral titer measurements in these flies were similar to those observed in WT flies. These findings indicate that expression of any of these AMPs alone is not sufficient to confer viral resistance in Drosophila.

Genetic Screen for Antiviral Immune Response Genes. To identify genes important for an antiviral response in Drosophila, we used anoxia-induced death to screen a collection of mutant Drosophila lines. All screened lines were known to be or predicted to be important in immune responses against bacteria or fungi (Table 1). Because of various genetic backgrounds and lack of parental stocks for many of these lines, intragroup comparisons were performed to quantify the severity of viral susceptibility of the screened lines. Lines that were outside of one standard deviation from the average survival at two or more time points were selected as having significantly altered sensitivity to viral infection. Five lines were found to have increased resistance to viral infection (Fig. 7). Only the Dif1 and Tl10b mutant lines were found to be more susceptible to DXV infection. It is important to note that relE20 flies, a null mutant for the NF-κB in the IMD pathway, displayed no significant alteration in its resistance to viral pathogenic effects and had viral titers similar to those observed in WT flies (Fig. 3). These results suggest that, although the Toll and IMD pathways are activated by viral infection, only the activity of the Toll pathway imparts specific resistance against DXV.

Fig. 3.

Increased susceptibility of Toll and Dif mutant fly lines. Dif1 lacks the ability to activate the Toll pathway. Tl10b is a constitutively active mutant of the Toll pathway. relE20 is a mutant in the IMD pathway. All measurements normalized to H2O-injected samples of the same mutant Drosophila line. Only Dif1 and Tl10b lines have significant alteration in survival, defined as two (or more) time points being outside of one standard deviation of the screened lines average survival (gray region). relE20 displays average survival. The 7-day time point increase in relE20 survival is due to base line effects from the wounding controls.

Toll Pathway Mutants Are More Sensitive to Viral Infection. To confirm that the Toll pathway was involved in an antiviral response, we examined Dif1, a loss of function mutant in an NF-κB-like transcription factor in the Toll pathway. As noted above, we find that the mutant line succumbs to anoxia induced death ≈48 h earlier than WT Drosophila (Fig. 3). In addition, viral titer levels were found to be ≈40 times higher than that observed in WT flies at 3 dpi. This increased viral titer correlates to a 5-dpi titer in WT Drosophila, the time point at which the main spike in anoxia induced death is observed. This finding suggests that Dif plays a role in an antiviral response that both inhibits viral replication and limits the pathogenic effects of infection.

To determine whether constitutive activation of the Toll pathway would confer increased resistance to DXV infection, we examined the Tl10b gain of function mutant fly line. Contrary to expectations, the Tl10b line also demonstrated early onset of anoxia sensitivity similar to that of the Dif1 line (Fig. 3). In addition, we find that these flies have viral load ≈50% that of WT flies at the same time point. This decreased viral titer suggests that the constitutive activation of the Toll pathway is able to retard viral replication but is not able to affect the overall outcome of DXV infection. This finding suggests that DXV titer may be partially independent of the pathogenic effects of infection.

Discussion

Use of DXV Infection for the Identification of Antiviral Response Genes. Our goal was to develop a model system for the genetic study of the antiviral innate immune response using the genetically tractable D. melanogaster. We find that injection of DXV, a dsRNA birnavirus, establishes an infection in Drosophila that causes anoxia sensitivity and death. Our examinations of this phenotype defined the time point and virus dosage levels required for reproducible use for a genetic screen. We found that over the course of infection there is a correlation between viral titer increase and sensitivity to anoxia.

Using immunohistology and TUNEL staining in DXV-infected WT Drosophila, we observed the viral progression and associated cellular death. It has been proposed that selective tissue infiltration by DXV may be the cause of the anoxia phenotype observed in infected flies (30). Although previous examinations indicate some tissue selectivity for the trachea and fat body that may be occurring early in infection, virus proliferation occurs so rapidly that it is not clear whether this specificity is the underlying cause of anoxia sensitivity (27). In the future, examination of our resistant mutant lines may shed more light on this.

We believe these results qualify DXV infection as a viable screening method for several reasons. First, the anoxia-based screening is consistent, easily performed, and rapid. Second, the time period between initial infection and anoxia sensitivity onset allows for assessment of immune system compromise severity. Third, the ability to accurately measure viral titer levels in vivo allow for determination of whether viral replication in mutants correlates with the pathogenic effects. Lastly, the ability to immunostain sections of animals for viral spread allows for localized tissue effects to be identified in tested mutant lines.

Using this system, we have demonstrated a previously undescribed role for the Toll pathway during an antiviral response. Anoxia-induced death experiments indicate that activation of the Toll pathway, but not its AMP effectors, is required for viral resistance. As a consequence of inactivation of the Toll pathway, viral titer and death by anoxia sensitivity increase dramatically. Additionally, because of the homology between the mammalian and Drosophila Toll pathways, this system may eventually identify novel genes important in innate antiviral immunity.

The Toll Pathway Plays a Vital Role in the Antiviral Innate Immune Response in Drosophila. The humoral immune response of Drosophila has been extensively studied as a model for innate immune signaling in mammals (34). Current models involve the parallel IMD and Toll pathways. Both pathways result in production of large quantities of secreted AMPs via the activation of NF-κB-related transcription factors as well as signaling for the activation of cellular responses (6, 35, 36). Although evidence exists that some AMPs may play an antiviral role in mammals, most of the characterized Drosophila AMPs work by membrane disruption, and it was not known whether they affected viruses (38, 39). Our examinations of AMP expression in DXV-infected Drosophila show an increase in expression of AMPs comparable to that found during an E. coli infection of WT flies. It has been previously shown that transgenic expression of single AMPs can rescue survival in immune compromised Drosophila (32). To examine whether this was true for viral resistance, anoxia DXV infection experiments were performed on Drosophila lines that constitutively expressed a single AMP in all tissues. We found that, contrary to what has been found during fungal and bacterial infection, constitutive expression of a single AMP provides no resistance to viral infection or decrease in viral titer. These results concur with known AMP action mechanisms of membrane disruption because viruses lack the cellular membrane structure necessary for these AMPs to be effective. Additionally, viral capsid diversity provides no known conserved target for AMPs to work on across a broad viral range. However, the increase in AMP expression does show that the IMD and Toll pathways are both activated by DXV infection. This finding suggests that, if AMPs play a role in an antiviral response, they are most likely playing an indirect role.

In our experiments, we screened a collection of fly lines mutant in genes predicted or identified as active in the Drosophila immune responses against bacteria or fungi. Dif1 and Tl10b mutant fly lines were both identified as being significantly more sensitive to viral infection than other lines examined. Additionally, the relE20 mutants had no effect on sensitivity to viral infection or viral titer levels. These results indicate that although both the IMD and Toll pathways are activated during viral infection, only the Toll pathway plays a role in viral resistance.

Our experiments also indicate that viral titer levels in the Dif1 and Tl10b mutant fly lines diverge from levels observed in the WT flies. Dif1 flies have increased viral titer early during infection compared to WT, which directly correlates to the observed increase in anoxia-induced death in this line. However, Tl10b flies have decreased viral titer compared to WT. Because of the lack of direct antiviral effects provided by single AMPs, we believe that these changes occur because of an alteration of the cellular response in Toll pathway mutants.

The Toll pathway plays a role in the proliferation of hemocytes, which are the effectors of the cellular immune response in Drosophila (15). Hemocytes play a critical part in the immune response in flies via phagocytosis and signaling to the fat body (39). The importance of these blood cells in fighting infection is visible when phagocytosis is blocked or in mutants that lack blood cells (40, 41). Hemocytes also play a role in surveillance of healthy and damaged basement membranes and encapsulate and destroy aberrant tissue (8). Previous observations show that cells undergoing normal apoptosis are recognized by hemocytes through Croquemort, a CD36-like receptor, and that hemocytes are able to act as a correctional mechanism when apoptosis goes wrong (42). It has been suggested that cells that do not undergo proper apoptosis are recognized as aberrant. Additionally, it has been shown in Lepidoptera that hemocytes are able to recognize virally infected cells (43). We therefore theorize that virally infected cells, which may be displaying characteristics of damaged cells as well as undergoing abnormal apoptosis, are recognized as aberrant and targeted by the hemocytes for phagocytosis and destruction (Fig. 4). Cells which are not recognized by hemocytes as aberrant and rupture due to viral replication would also release internal cellular compounds, such as endogenous DNA, into the hemocoel of the fly. In both Drosophila and mammals, materials of this type have been shown to instigate immune responses. Undigested endogenous DNA in caspase and DNase mutant Drosophila lines has been previously noted to cause multiple immunostimulatory responses, among them melanotic encapsulation of self tissue and constitutive Diptericin expression (44-47). Uric acid, produced during the catabolism of purines, is present at high concentration in cytosol and has been shown to enhance CD8+ T cell responses in mammalian systems (5). Our AMP profile data from 24 hours after infection shows that, of the AMPs whose expression is altered in comparison to E. coli infection, Diptericin is shifted upwards compared to levels observed in the Gram- bacterial infection expression profile. Diptericin expression is used as a flag for activation of the IMD pathway, and this activation by undigested endogenous DNA may account for the pathway's activation during viral infection without a corresponding role in viral resistance. Additionally, this finding suggests that the IMD pathway plays little to no role in stimulating the cellular response during viral infection. These observations suggest that the decreased viral titer in Tl10b flies is a result of their increased hemocyte number and increased cellular immune response. Increased sensitivity to anoxia is most likely due to an inability, even in this highly activated immune state, to prevent destruction of select tissues that cause the anoxia sensitivity phenotype.

Fig. 4.

Model for Drosophila antiviral response. 1, Virus enters system and infects the cell. 2, Virus replication. 3, Lysis of infected cell, releasing internal cellular compounds and virus. 4, Released materials activate the IMD and Toll humoral immune pathways and cause local activation of the cellular response. 5, Global activation of hemocytes via Toll pathway signaling. 6, Activated hemocytes signal to the fat body enhancing Toll and IMD pathways activation. 7, Hemocytes recognize aberrant infected cells and engulf and eliminate these cells. Activated hemocytes then enforce stringent recognition of aberrant tissue and destroy infected cells more efficiently. Green arrows indicate signaling to activate the humoral response. Blue arrows indicate signaling to activate the cellular response.

We theorize that the required activation of the Toll pathway for antiviral immunity may be occurring via cellular debris released during cell rupture due to viral replication. Internal compounds may initiate a chain of events that results in Toll pathway activation, similar to the activation of the IMD pathway by endogenous DNA. This may be occurring in a fashion analogous to the activity of cytokines in mammals with hemocytes releasing a signal which activates the Toll pathway.

The possibility of this antiviral response of the Toll pathway in Drosophila is another example of the means by which the innate immune system is able to respond to diverse pathogens. Using this genetically tractable animal, with its sophisticated blood cell-dependent innate immune system, the possibilities for increasing our understanding of viral pathogenesis are tremendous. The possibility to identify host genes by forward screening is also feasible.

Conclusions

We have found that the Toll pathway is specifically required for the inhibition of DXV replication and spread during infection in Drosophila. This represents the identification of a Drosophila innate immune pathway having a role in viral resistance. Our results also demonstrate the ongoing competition between virus replication, the host immune response, and the effects of this competition over the course of an infection. Together, this evidence provides the initial insights into the antiviral response of the Drosophila innate immune system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Savage, G. H. Edwards, I. Bhansaly, and D. Levy for technical assistance. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health and University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute Start-Up Funds.

Author contributions: R.A.Z. and L.P.W. designed research; R.A.Z. performed research; R.A.Z. and V.N.V. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; R.A.Z. analyzed data; R.A.Z. wrote the paper; and M.N. screened flies and collected data.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; AMP, antimicrobial peptide; DXV, Drosophila X virus; dpi, days postinfection.

References

- 1.Medzhitov, R. & Janeway, C. A., Jr. (1997) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 9, 4-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aderem, A. & Ulevitch, R. J. (2000) Nature 406, 782-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akira, S., Takeda, K. & Kaisho, T. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 675-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akira, S. (2003) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15, 5-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi, Y., Evans, J. E. & Rock, K. L. (2003) Nature 425, 516-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Gregorio, E., Spellman, P. T., Rubin, G. M. & Lemaitre, B. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12590-12595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizki, T. M. (1978) in The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila, eds. Ashburner, M. & Wright, T. R. F. (Academic, New York), pp. 561-599.

- 8.Rizki, T. M. & Rizki, R. M. (1984) in Insect Ultrastrucure, eds. King, R. C. & Akai, H. H. (Plenum, New York), pp. 579-604.

- 9.Bischoff, V., Vignal, C., Boneca, I. G., Michel, T., Hoffmann, J. A. & Royet, J. (2004) Nat. Immunol. 5, 1175-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann, J. A. (2003) Nature 426, 33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber, A. N., Tauszig-Delamasure, S., Hoffmann, J. A., Lelievre, E., Gascan, H., Ray, K. P., Morse, M. A., Imler, J. L. & Gay, N. J. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4, 794-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemaitre, B., Nicolas, E., Michaut, L., Reichhart, J. M. & Hoffmann, J. A. (1996) Cell 86, 973-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ip, Y. T., Reach, M., Engstrom, Y., Kadalayil, L., Cai, H., Gonzalez-Crespo, S., Tatei, K. & Levine, M. (1993) Cell 75, 753-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morisalo, D. & Anderson, K. V. (1995) Annu. Rev. Genet. 29, 371-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiu, P., Pan, P. C. & Govind, S. (1998) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 125, 1909-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneko, T., Goldman, W. E., Mellroth, P., Steiner, H., Fukase, K., Kusumoto, S., Harley, W., Fox, A., Golenbock, D. & Silverman, N. (2004) Immunity 20, 637-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Georgel, P., Naitza, S., Kappler, C., Ferrandon, D., Zachary, D., Swimmer, C., Kopczynski, C., Duyk, G., Reichhart, J. M. & Hoffmann, J. A. (2001) Dev. Cell 1, 503-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naitza, S., Rosse, C., Kappler, C., Georgel, P., Belvin, M., Gubb, D., Camonis, J., Hoffmann, J. A. & Reichhart, J. M. (2002) Immunity 17, 575-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu, S. & Yang, X. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30761-30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoven, S., Silverman, N., Junell, A., Hedengren-Olcott, M., Erturk, D., Engstrom, Y., Maniatis, T. & Hultmark, D. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 5991-5996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu, Y., Wu, L. P. & Anderson, K. V. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 104-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rutschmann, S., Jung, A. C., Zhou, R., Silverman, N., Hoffmann, J. A. & Ferrandon, D. (2000) Nat. Immunol. 1, 342-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverman, N., Zhou, R., Stoven, S., Pandey, N., Hultmark, D. & Maniatis, T. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 2461-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vidal, S., Khush, R. S., Leulier, F., Tzou, P., Nakamura, M. & Lemaitre, B. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 1900-1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng, X., Khanuja, B. S. & Ip, Y. T. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 792-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutschmann, S., Jung, A. C., Hetru, C., Reichhart, J. M., Hoffmann, J. A. & Ferrandon, D. (2000) Immunity 12, 569-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tauszig-Delamasure, S., Bilak, H., Capovilla, M., Hoffmann, J. A. & Imler, J. L. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 91-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherry, S. & Perrimon, N. (2004) Nat. Immunol. 5, 81-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung, H. K., Kordyban, S., Cameron, L. & Dobos, P. (1996) Virology 225, 359-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teninges, D., Ohanessian, A., Richardmolard, C. & Contamine, D. (1979) J. Gen. Virol. 42, 241-254. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harlow, E. & Lane, D. (1999) in Using Antibodies, eds. Cuddihy, J. & Kuhlman, T. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY).

- 32.Tzou, P., Reichhart, J. M. & Lemaitre, B. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2152-2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brand, A. H. & Perrimon, N. (1993) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 118, 401-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khush, R. S., Leulier, F. & Lemaitre, B. (2001) Trends Immunol. 22, 260-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Gregorio, E., Spellman, P. T., Tzou, P., Rubin, G. M. & Lemaitre, B. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 2568-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irving, P., Troxler, L., Heuer, T. S., Belvin, M., Kopczynski, C., Reichhart, J. M., Hoffmann, J. A. & Hetru, C. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 15119-15124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bulet, P., Hetru, C., Dimarcq, J. L. & Hoffmann, D. (1999) Dev. Comp. Immunol. 23, 329-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meister, M., Hetru, C. & Hoffmann, J. A. (2000) Curr. Topics Microbiol. Immunol. 248, 17-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basset, A., Khush, R. S., Braun, A., Gardan, L., Boccard, F., Hoffmann, J. A. & Lemaitre, B. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 3376-3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun, A., Hoffmann, J. A. & Meister, M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 14337-14342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elrod-Erickson, M., Mishra, S. & Schneider, D. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 781-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Franc, N. C., Heitzler, P., Ezekowitz, R. A. & White, K. (1999) Science 284, 1991-1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trudeau, D., Washburn, J. O. & Volkman, L. E. (2001) J. Virol. 75, 996-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mukae, N., Yokoyama, H., Yokokura, T., Sakoyama, Y. & Nagata, S. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 2662-2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Napirei, M., Karsunky, H., Zevnik, B., Stephan, H., Mannherz, H. G. & Moroy, T. (2000) Nat. Genet 25, 177-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez, A., Oliver, H., Zou, H., Chen, P., Wang, X. & Abrams, J. M. (1999) Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 272-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song, Z., McCall, K. & Steller, H. (1997) Science 275, 536-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.