Abstract

Latent membrane protein 2B (LMP2B) is expressed during latent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, but little is known about its role. The goal of this study was to determine whether an LMP2B homologue is conserved in the rhesus monkey lymphocryptovirus (LCV). Both rhesus LCV LMP2A and LMP2B genes were cloned and sequenced. The rhesus LCV LMP2B gene is positionally conserved, and the EBNA-2 responsiveness and the bidirectional nature of the LMP1-LMP2B promoter have also been functionally conserved. However, this region of the genome encoding the LMP1, LMP1-LMP2B promoter, and LMP2B first exon demonstrates the most dramatic nucleotide sequence divergence between human and nonhuman LCV observed to date. Evolution of the rhesus LCV LMP2B promoter and transcript despite the dynamic nature of this genomic region reflects strong selective pressure for a yet-to-be-identified LMP2B function.

Latent membrane protein 2B (LMP2B) is one of the three membrane proteins expressed during latent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection (for a review, see reference 17). LMP2B is also expressed in EBV-related malignancies (for reviews, see references 2 and 29), but the role of LMP2B in EBV infection and pathogenesis in vivo remains unknown. The LMP2B gene is closely related to the LMP2A gene. They share eight of nine exons and are identical except for their unique first exons (20, 28). Whereas the first exon of LMP2A encodes a 119-amino-acid cytoplasmic domain, the LMP2B first exon is noncoding. LMP2B translation initiates from an ATG codon at the beginning of the second exon. Thus, LMP2B is essentially a deletion mutant of LMP2A consisting of the last 379 amino acids encoded in the common second through ninth exons. Since the LMP2B gene is located immediately upstream of the LMP1 gene and is transcribed in the opposite direction as LMP1, this region serves as a bidirectional promoter for both LMP1 and LMP2B (19, 28).

To date, reports of significant functional activity for the LMP2 proteins have been limited to LMP2A and the presence of the unique LMP2A first exon. Tyrosine residues in the LMP2A first exon are important for interaction with and constitutive phosphorylation by syk and lyn protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) (8, 24). B cells immortalized with LMP2A-deleted EBV are more sensitive to B-cell receptor cross-linking and induction of lytic cycle infection (24, 25). Since B-cell receptor activation and src kinase activation can induce EBV reactivation (4, 30), the interaction of LMP2A with these PTKs is likely to be important for inhibiting lytic cycle reactivation and maintaining latent infection in EBV-infected cells. Neither LMP2 gene is required for EBV-induced B-cell immortalization in vitro, indicating that the LMP2A interaction with src kinases is not required for growth transformation (22, 23). As LMP2B lacks the amino terminal cytoplasmic domain, LMP2B is unlikely to interact with PTKs and to have similar effects on B-cell receptor signal transduction.

The lack of obvious functional activity, the noncoding nature of the first exon, and the unusual bidirectional nature of the LMP2B promoter raise the possibility that the evolution of LMP2B might have been a fortuitous event. Other herpesviruses that naturally infect Old World nonhuman primates have evolved similarly and are classified in the same lymphocryptovirus (LCV) subgroup as EBV (for reviews, see references 1 and 5). These simian LCVs have similar B-cell immortalizing properties in vitro and similar pathogenesis in vivo as EBV (10, 26). Studies from our laboratory and others indicate that homologues for latent infection nuclear proteins (EBNA-LP, -1, -2, -3A, -3B, and -3C) and membrane proteins (LMP1 and LMP2A) have been conserved in baboon and rhesus LCVs (6, 7, 15, 21, 32). Interestingly, there was no evidence for an LMP2B transcript on Northern blots of RNA from baboon LCV-infected cells probed with a baboon LCV LMP2A cDNA probe (6). To test whether the LMP2B gene was an unusual evolutionary event restricted to EBV, we examined whether the rhesus LCV encoded both LMP2A and LMP2B homologues.

LMP2A is positionally and structurally conserved in rhesus LCV.

The putative LMP2A first exon was sequenced from the previously published rhesus LCV DNA fragment, RE1 (7). The sequence of a potential LMP2A ninth exon was derived from a 2.5-kb BamHI DNA fragment (CD1PR1) which was subcloned from a rhesus LCV cosmid clone (RcosCD1) by cross-hybridization with an EBV LMP2A cDNA probe. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR amplification with a 5′ primer in the LMP2A first exon and a 3′ primer in the putative LMP2A ninth exon revealed a 1.9-kb product from rhesus LCV-infected B-cell RNA. The nucleotide sequence of the 1.9-kb RT-PCR product from four independent clones confirmed that the transcript was homologous to the baboon LCV and EBV LMP2A transcripts (62 and 66% nucleotide homology, respectively; Fig. 1A).

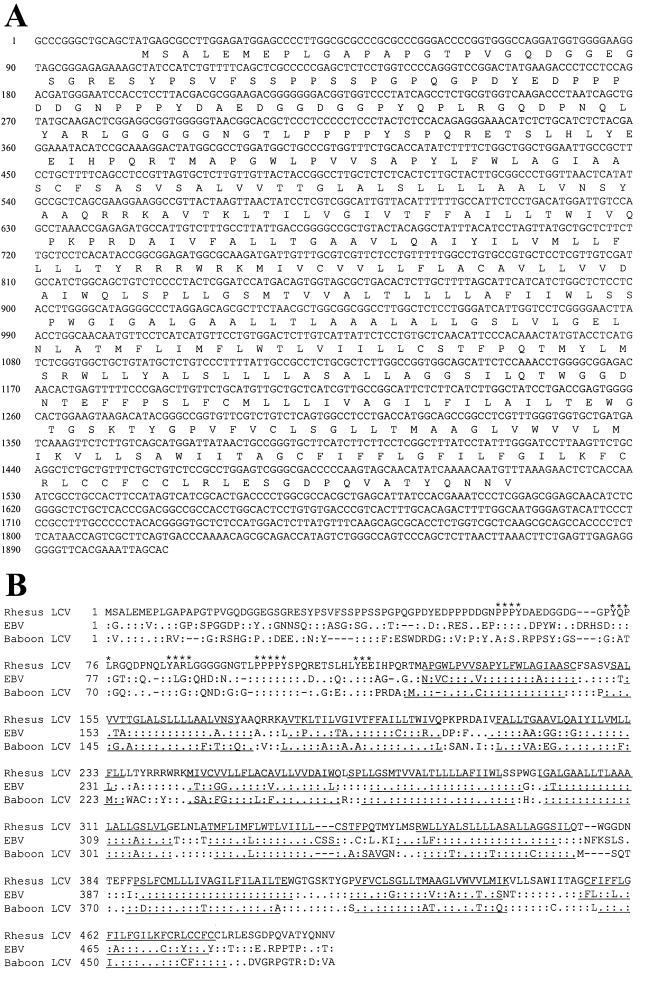

FIG. 1.

(A) Nucleotide and amino acid sequence of the rhesus LCV LMP2A cDNA. RT-PCR was done with 5′ primer E1A (5′-GGAATCCACCTCCTTACG-3′) and 3′ primer E9 (5′-GTGCTAATTTCGTGAACCCC-3′). The sequence was derived from both strands from four independent clones (GenBank accession no. AF148640). (B) Comparison of rhesus LCV, EBV, and baboon LCV LMP2A protein sequences. :, amino acid identity; ., amino acid similarity. The hydrophobic transmembrane domains (underlined) were identified with the SOSUI program (3a). Phosphotyrosine motifs already reported to be involved in the function of EBV LMP2A (ITAM, PPPY motif, YEE motif) are starred.

Translation of the rhesus LCV LMP2A cDNA revealed an open reading frame encoding 495 amino acids with 57% amino acid identity to the baboon LCV and EBV LMP2A (Fig. 1B). The 12 transmembrane domains are well conserved. The amino-terminal cytoplasmic domain encoded by the LMP2A first exon and deduced from genomic DNA and multiple RT-PCR clones is more divergent (38% amino acid identity to baboon LCV and EBV LMP2A). However, important tyrosine residues are conserved in rhesus LCV LMP2A with an ITAM-like motif (Y73 and Y85), a conserved tyrosine residue at position 113, and two PPPY motifs (positions 59 to 62 and 99 to 102) (Fig. 1B). Conservation of these motifs is consistent with an important role for LMP2A interaction with src kinases in the pathogenesis of human and nonhuman LCV infection.

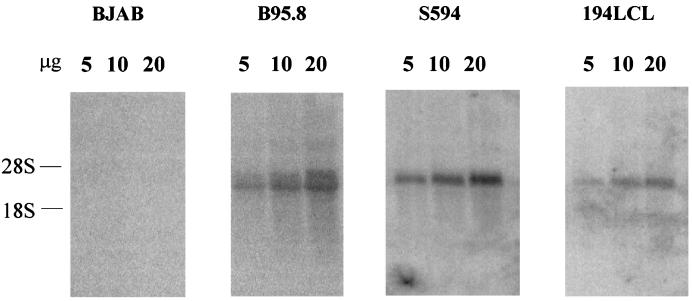

Rhesus LCV LMP2A cDNA was used as a probe to detect LMP2A and potential LMP2B transcripts on Northern blots with RNA from rhesus LCV-infected B cells (Fig. 2). Whereas the EBV LMP2A cDNA detected both LMP2A and LMP2B transcripts of 2.3 and 2 kb, respectively, in EBV-infected B-cell RNA (B95-8 [28]), the rhesus LCV LMP2A cDNA detected only one 2.2-kb band in rhesus LCV-infected B-cell RNA (194LCL). Similarly, the baboon LCV LMP2A cDNA detected only a single band in blots with baboon LCV-infected B-cell RNA as previously reported (S594 [6]). The detection of only a single band on Northern blots may be consistent with similarly sized LMP2A and LMP2B transcripts, lower abundance of LMP2B transcripts, or a lack of LMP2B transcripts in the simian LCV-infected B cells.

FIG. 2.

LMP2A and LMP2B expression on Northern blot of EBV-, baboon LCV-, and rhesus LCV-infected cell RNA. Total RNA (5, 10, or 20 μg) from EBV-negative cells (BJAB) and from cells infected with EBV (B95.8), baboon LCV (S594), and rhesus LCV (194LCL) were hybridized with EBV LMP2A cDNA, baboon LCV LMP2A cDNA, and rhesus LCV LMP2A cDNA. Migration of 28S and 18S rRNAs are shown.

LMP2B first exon is positionally conserved despite divergence between rhesus LCV and EBV LMP1-LMP2B promoter regions.

To test whether a rhesus LCV LMP2B first exon was positionally conserved, we cloned and sequenced 563 bases of the LMP1 upstream region (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, the rhesus LCV LMP1 promoter is not well conserved with the EBV LMP1 promoter (27% nucleotide homology). This is significantly different from other latent infection promoters from rhesus and baboon LCVs (Table 1). Despite the poor sequence homology, RBP-Jκ/CBF-1 (12, 13) and PU.1/Spi1 (16, 18) binding sites important for LMP1 transcriptional regulation have been conserved (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the rhesus LCV LMP1 promoter contains only one RBP-Jκ/CBF-1 binding site, compared to two in EBV, and both the RBP-Jκ/CBF-1 and PU.1/Spi1 binding sites are located on the opposite strand as compared to the EBV LMP1 promoter. These findings suggest that despite the high degree of genetic evolution in this region, there is strong selective pressure for conserving important transcriptional regulatory motifs.

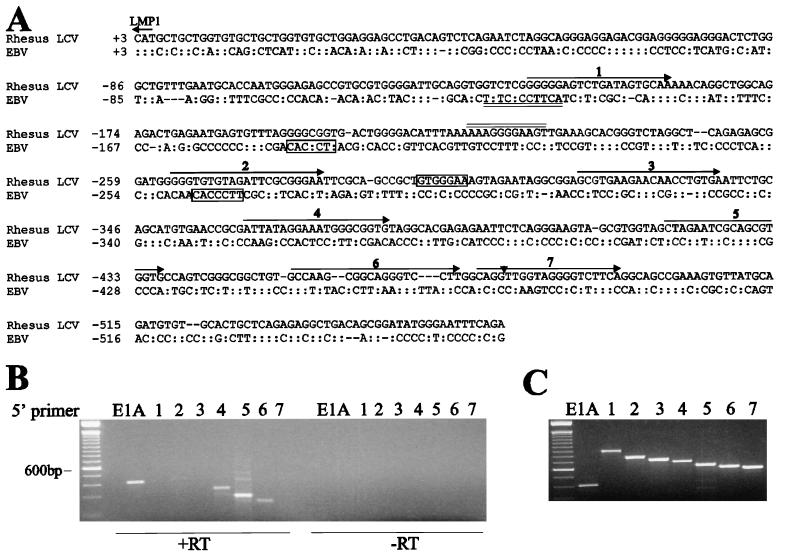

FIG. 3.

(A) Comparison of rhesus LCV and EBV LMP1 promoter sequences. The rhesus LCV LMP1 promoter was amplified with a 5′ primer Rh1 (5′-AACCAGACCTTGCCAC-3′) and a 3′ primer TR from the EBV sequence at nucleotide 170,012 (5′-TCTGAAATTCCCATATCCGC-3′) and both strands were sequenced from three independent clones (GenBank accession no. AF148641). PU.1/Spi1 (AAAGGGGAAGT) binding sites are double underlined and RBP-Jκ/CBF-1 binding sites are boxed. Note that PU.1/Spi1 and RBP-Jκ/CBF-1 sites within rhesus LCV LMP1 promoter are on the opposite DNA strand as compared to the EBV LMP1 promoter. Primers (1 to 7) used to amplify a rhesus LCV LMP2B transcript are indicated. The end of the rhesus LCV LMP2B first exon is denoted by an arrowhead. :, nucleotide identity. (B) LMP2A and LMP2B RT-PCR from rhesus LCV-infected cell RNA. RT-PCR amplification for LMP2B was done with E2r (5′-GTAACAATGCCGACGAGGAT-3′) and one of seven primers (1 to 7) covering the 500-bp upstream rhesus LCV LMP1 translational initiation site. RT-PCR amplification for LMP2A was done with primers E2r and E1A (5′-GGAATCCACCTCCTTACG-3′). No amplification is detected if no RT is added in the reaction (−RT). (C) Control PCR amplifications from a synthetic DNA amplicon or LMP2A cDNA clone. PCR was done with the same primers as described for panel B.

TABLE 1.

Homology between human and nonhuman LCV latent infection promoters

| Latent infection promoter | % Nucleotide homology with EBV

|

Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhesus LCV | Baboon LCV | ||

| LMP1-LMP2B | 27 | NDa | This report |

| LMP2A | 55 | 54 | 6, 31 |

| EBNA (Cp) | 66 | 64 | 9 |

| EBNA-1 (Qp) | 80 | 86 | 27 |

ND, not determined.

No obvious LMP2B TATA box was found in the LMP1 upstream region as is the case for EBV LMP2B. Therefore, we designed a series of primers in the LMP1 promoter region in order to identify potential rhesus LCV LMP2B transcripts by RT-PCR amplification. Seven primers (designated 1 to 7; Fig. 3A) were paired with a 3′ primer in the second exon of LMP2A (E2r) for RT-PCR amplification of RNA from rhesus LCV-infected B cells. As shown in Fig. 3B, an RT-PCR product was obtained when primers 4, 5, and 6 were paired with E2r. No product was detected in the absence of RT, and no product was obtained when primers 1, 2, 3, or 7 were paired with E2r even though these primer combinations were able to amplify a product from an artificial DNA construct (Fig. 3C). Sequencing of the RT-PCR products obtained with the primer pairs of 4, 5, and 6 with E2r confirmed that the splice donor site was at nucleotide −476 relative to the LMP1 translational initiation site and the splice acceptor site in the second exon was identical to LMP2A. Longer RT-PCR products (1.5 to 1.6 kb) were also obtained with primers 4, 5, and 6 with a 3′ primer in the LMP2A ninth exon, suggesting that the rhesus LCV LMP2B shares exons two through nine of LMP2A (data not shown). Finally, the RT-PCR results also suggest that the 5′ end of the LMP2B transcript is between primers 3 and 4, approximately −337 to −361 nucleotides upstream of the LMP1 translational initiation site. In that case, the LMP2B first exon (110 bp) should be shorter than the LMP2A first exon (350 bp), suggesting that the failure to detect an LMP2B transcript on Northern blots is due to a much lower level of expression for rhesus LCV LMP2B than for LMP2A.

Transcriptional regulation of the LMP1-LMP2B bidirectional promoter is conserved in rhesus LCV.

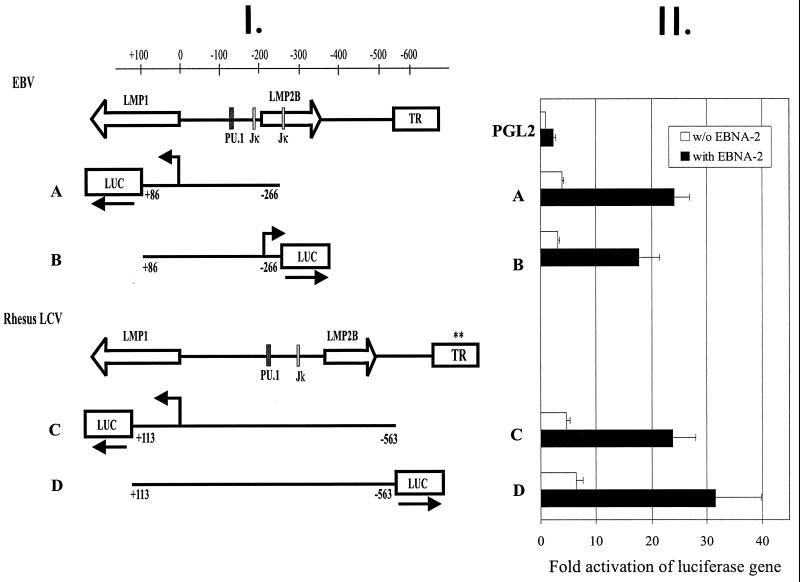

Reporter constructs were made to test whether the bidirectional nature and EBNA-2 responsiveness of the LMP1 promoter were functionally conserved in rhesus LCV. EBV and rhesus LCV DNA fragments containing the LMP1 promoter were cloned in either direction relative to a luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 4, panel I). Both EBV and rhesus LCV LMP1 promoters (parts A and C, open boxes; Fig. 4, panel II) showed three- to sixfold activation of the reporter gene relative to the luciferase gene alone (pGL2; Fig. 4, panel II) when transfected into EBV-negative human B lymphoma cells. When the promoter elements were cloned in the opposite orientation (parts B and D, open boxes; Fig. 4, panel II), similar levels of activity were detected, indicating that the EBV and rhesus LCV LMP1 promoters are bidirectional. To test whether EBNA-2 responsiveness had been conserved, promoter constructs were cotransfected with an EBV EBNA-2 expression construct. EBNA-2 cotransfection increased luciferase activity of the rhesus LCV promoter five- to sixfold in either the LMP1 or LMP2B orientation (Fig. 4, panel II, filled boxes). The level of LMP1-LMP2B promoter activity induced by EBNA-2 was comparable among the EBV and rhesus LCV promoters.

FIG. 4.

Promoter analysis of EBV and rhesus LCV LMP1 promoters. (Panel I) The LMP1 transcript, LMP2B transcript, PU.1/Spi1 and RBP-Jκ/CBF-1 binding sites, and terminal repeats (TR) from EBV and rhesus LCV are shown. Luciferase reporter constructs with EBV sequences (A and B) and rhesus LCV sequences (C and D) are shown. (Panel II) Promoter activity of luciferase reporter constructs in EBV-negative human B lymphoma cells in the absence (open bars) or presence (solid bars) of EBV EBNA-2 is shown. Luciferase activity was normalized for transfection efficiency by using a cotransfected simian virus 40 early promoter-driven β-galactosidase expression plasmid. Results are the averages of five independent assays, and the error bars represent the standard deviations.

These studies show that the LMP2B transcript, the bidirectional nature of the LMP1-LMP2B promoter, and the EBNA-2 responsiveness of the bidirectional LMP1-LMP2B promoter have been conserved in the rhesus LCV. This end of the LCV genome is highly divergent at the nucleotide level from the terminal repeat, through the LMP2B first exon-promoter (27% homology), LMP1 gene (29%), and LMP2A first exon (38%). The conservation of the rhesus LCV LMP2B promoter and transcript, despite the dynamic nature of this genomic region, reflects strong selective pressure for an important but yet-to-be-identified LMP2B function. Since LMP2B is a deletion mutant of LMP2A, it is possible that LMP2B may act to modulate LMP2A function in some manner. However, in vitro studies to date have revealed no evidence for an LMP2B regulatory effect on LMP2A function. In vivo studies with an LMP2B deleted virus may be required to reveal important LMP2B functions. Homologues for all of the EBV genes expressed during latent infection have now been identified in the rhesus LCV, including EBNA-1, -2, -3A, -3B, -3C, -LP, LMP1, LMP2A, LMP2B, and EBERs (3, 7, 11, 14, 15). These molecular studies add further support to and highlight the potential utility of rhesus LCV as an important animal model for EBV infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the Public Health Service (CA68051 and CA65319). P.R. was a fellow of the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ablashi D V, Gerber P, Easton J. Oncogenic herpesviruses of nonhuman primates. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 1979;2:229–241. doi: 10.1016/0147-9571(79)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambinder R F, Mann R B. Detection and characterization of Epstein-Barr virus in clinical specimens. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:239–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake N W, Moghaddam A, Rao P, Kaur A, Glickman R, Cho Y-G, Marchini A, Haigh T, Johnson R P, Rickinson A B, Wang F. Inhibition of antigen presentation by the glycine/alanine repeat domain is not conserved in simian homologues of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. J Virol. 1999;73:7381–7389. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7381-7389.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Classification and Secondary Structure Prediction of Membrane Proteins Website. 19 September 1998, revision date. [Online.] SOSUI software, version 1.0. Department of Biotechnology, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Tokyo, Japan. http://www.tuat.ac.jp/∼mitaku/adv_sosui/. [9 August 1999, date last accessed.]

- 4.Daibata M, Humphreys R E, Takada K, Sairenji T. Activation of latent EBV via anti-IgG-triggered, second messenger pathways in the Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line Akata. J Immunol. 1990;144:4788–4793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank A, Andiman W A, Miller G. Epstein-Barr virus and nonhuman primates: natural and experimental infection. Adv Cancer Res. 1976;23:171–201. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franken M, Annis B, Ali A N, Wang F. 5′ Coding and regulatory region sequence divergence with conserved function of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A homolog in herpesvirus papio. J Virol. 1995;69:8011–8019. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8011-8019.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franken M, Devergne O, Rosenzweig M, Annis B, Kieff E, Wang F. Comparative analysis identifies conserved tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3 binding sites in the human and simian Epstein-Barr virus oncogene LMP1. J Virol. 1996;70:7819–7826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7819-7826.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fruehling S, Swart R, Dolwick K M, Kremmer E, Longnecker R. Tyrosine 112 of latent membrane protein 2A is essential for protein tyrosine kinase loading and regulation of Epstein-Barr virus latency. J Virol. 1998;72:7796–7806. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7796-7806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuentes-Panana E M, Swaminathan S, Ling P D. Transcriptional activation signals found in the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latency C promoter are conserved in the latency C promoter sequences from baboon and rhesus monkey EBV-like lymphocryptoviruses (cercopithicine herpesviruses 12 and 15) J Virol. 1999;73:826–833. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.826-833.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerber P, Kalter S S, Schidlovsky G, Peterson W D, Jr, Daniel M D. Biologic and antigenic characteristics of Epstein-Barr virus-related herpesviruses of chimpanzees and baboons. Int J Cancer. 1977;20:448–459. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910200318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordadze, A., and P. Ling. Rhesus LCV EBNA-2 and EBNA-LP sequences. Unpublished data.

- 12.Grossman S R, Johannsen E, Tong X, Yalamanchili R, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 transactivator is directed to response elements by the J kappa recombination signal binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7568–7572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henkel T, Ling P D, Hayward S D, Peterson M G. Mediation of Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2 transactivation by recombination signal-binding protein J kappa. Science. 1994;265:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.8016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang, H., and F. Wang. Rhesus LCV EBERs sequence. Unpublished data.

- 15.Jiang, H., and F. Wang. Rhesus LCV EBNA-3A, -3B, -3C sequence. Unpublished data.

- 16.Johannsen E, Koh E, Mosialos G, Tong X, Kieff E, Grossman S R. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 transactivation of the latent membrane protein 1 promoter is mediated by J kappa and PU.1. J Virol. 1995;69:253–262. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.253-262.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication. In: Knipe D, Fields B, Howley P, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Raven Press; 1996. pp. 2343–2396. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laux G, Adam B, Strobl L J, Moreau-Gachelin F. The Spi-1/PU.1 and Spi-B ets family transcription factors and the recombination signal binding protein RBP-J kappa interact with an Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 responsive cis-element. EMBO J. 1994;13:5624–5632. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laux G, Economou A, Farrell P J. The terminal protein gene 2 of Epstein-Barr virus is transcribed from a bidirectional latent promoter region. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:3079–3084. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-11-3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laux G, Perricaudet M, Farrell P J. A spliced Epstein-Barr virus gene expressed in immortalized lymphocytes is created by circularization of the linear viral genome. EMBO J. 1988;7:769–774. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02874.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ling P D, Ryon J J, Hayward S D. EBNA-2 of herpesvirus papio diverges significantly from the type A and type B EBNA-2 proteins of Epstein-Barr virus but retains an efficient transactivation domain with a conserved hydrophobic motif. J Virol. 1993;67:2990–3003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.2990-3003.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longnecker R, Miller C L, Miao X-Q, Marchini A, Kieff E. The only domain which distinguishes Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A (LMP2A) from LMP2B is dispensable for lymphocyte infection and growth transformation in vitro; LMP2A is therefore nonessential. J Virol. 1992;66:6461–6469. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6461-6469.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longnecker R, Miller C L, Tomkinson B, Miao X-Q, Kieff E. Deletion of DNA encoding the first five transmembrane domains of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane proteins 2A and 2B. J Virol. 1993;67:5068–5074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.5068-5074.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller C L, Burkhardt A L, Lee J H, Stealey B, Longnecker R, Bolen J B, Kieff E. Integral membrane protein 2 of Epstein-Barr virus regulates reactivation from latency through dominant negative effects on protein-tyrosine kinases. Immunity. 1995;2:155–166. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(95)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller C L, Lee J H, Kieff E, Longnecker R. An integral membrane protein (LMP2) blocks reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency following surface immunoglobulin crosslinking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:772–776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moghaddam A, Rosenzweig M, Lee-Parritz D, Annis B, Johnson R P, Wang F. An animal model for acute and persistent Epstein-Barr virus infection. Science. 1997;276:2030–2033. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruf I K, Moghaddam A, Wang F, Sample J. Mechanisms that regulate Epstein-Barr virus EBNA-1 gene transcription during restricted latency are conserved among lymphocryptoviruses of Old World primates. J Virol. 1999;73:1980–1989. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1980-1989.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sample J, Liebowitz D, Kieff E. Two related Epstein-Barr virus membrane proteins are encoded by separate genes. J Virol. 1989;63:933–937. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.933-937.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorley-Lawson D A, Miyashita E M, Khan G. Epstein-Barr virus and the B cell: that’s all it takes. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:204–208. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(96)90020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tovey M G, Lenoir G, Begon-Lours J. Activation of latent Epstein-Barr virus by antibody to human IgM. Nature. 1978;276:270–272. doi: 10.1038/276270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, F. Rhesus LCV LMP2-A promoter sequence. Unpublished data.

- 32.Yates J L, Camiolo S M, Ali S, Ying A. Comparison of the EBNA1 proteins of Epstein-Barr virus and herpesvirus papio in sequence and function. Virology. 1996;222:1–13. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]