Abstract

Bardet-Biedl Syndrome (BBS) is an autosomal recessive non-motile ciliopathy, caused by mutations in more than twenty genes. Their expression leads to the production of BBSome-building proteins or chaperon-like proteins supporting its structure. The prevalence of the disease is estimated at 1: 140,000 – 160,000 of life births. Its main clinical features are retinal dystrophy, polydactyly, obesity, cognitive impairment, hypogonadism, genitourinary malformations, and kidney disease. BBS is characterized by heterogeneous clinical manifestation and the variable onset of signs and symptoms. We present a case series of eight pediatric patients with BBS (6 boys and 2 girls) observed in one clinical center including two pairs of siblings. The patients’ age varies between 2 to 13 years (average age of diagnosis: 22 months). At presentation kidney disorders were observed in seven patients, polydactyly in six patients’ obesity, and psychomotor development delay in two patients. In two patients with kidney disorders, the genetic tests were ordered at the age of 1 and 6 months due to the presence of symptoms suggesting BBS and having an older sibling with the diagnosis of the syndrome. The mutations in the following genes were confirmed: BBS10, MKKS, BBS7/BBS10, BBS7, BBS9. All described patients developed symptoms related to the urinary system and kidney-function impairment. Other most common symptoms are polydactyly and obesity. In one patient the obesity class 3 was diagnosed with multiple metabolic disorders. In six patients the developmental delay was diagnosed. The retinopathy was observed only in one, the oldest patient. Despite having the same mutations (siblings) or having mutations in the same gene, the phenotypes of the patients are different. We aimed to addresses gaps in understanding BBS by comparing our data and existing literature through a narrative review. This research includes longitudinal data and explores genotype-phenotype correlations of children with BBS. BBS exhibits diverse clinical features and genetic mutations, making diagnosis challenging despite defined criteria. Same mutations can result in different phenotypes. Children with constellations of polydactyly and/or kidney disorders and/or early-onset obesity should be managed towards BBS. Early diagnosis is crucial for effective monitoring and intervention to manage the multisystemic dysfunctions associated with BBS.

Keywords: Bardet-Biedl syndrome, BBS, obesity, genetics, rare diseases

1. Introduction

Bardet-Biedl Syndrome (BBS) is an autosomal recessive disease, first described by the French physician Bardet in 1920 (1, 2). The prevalence of the disease is estimated at 1: 140,000 – 160,000 births. Currently, there are 24 genes mutations with a confirmed association with BBS phenotype. Their expression leads to the production of BBSome-building proteins (BBS1, BBS2, BBS4, BBS5, BBS7, BBS8, BBS9, BBS18 genes) or chaperon-like proteins supporting its structure (BBS6/MKKS, BBS12, BBS10 genes). BBSome is an octamer responsible for transport within the primary cilia, the dysfunction of which leads to the development of the symptoms (3–5). Based on BBS’s pathomechanism it is classified as a ciliopathy along with other conditions such as Alström’s and Meckel’s syndromes (6–8). Moreover, BBS can be attributed to the ever-expanding group of chaperonopathies - diseases caused by defects in chaperones or proteins resembling their structure (9).

BBS symptoms are divided into primary and secondary. A clinical diagnosis can be made in presence of 4 large symptoms or 3 large and 2 small symptoms (1). Nowadays, the clinical diagnosis should be confirmed with genetic tests. Due to the elevated risk of serious organ damage related to BBS, early diagnosis and monitoring of pediatric patients presenting symptoms of this disease is extremely important.

2. Methodology

2.1. Patients’ selection process and clinical assessment procedures

Patients included in this study are those with molecularly confirmed mutations in BBS-associated genes, identified through clinic’s record search. We gathered data from patients’ medical history to depict symptom development over the course of time and identify key features and trends. It is worth noting that all patients were referred to our clinic from different medical centers across Silesia. therefore, clinical assessment procedures varied prior to BBS diagnosis. Since the admission to the clinic and the diagnosis all the patients followed our assessment protocol, which included:

2.2. Genetic testing

Patients were diagnosed in different years via molecular tests available at the given time. P2, P3, P6 and P7 underwent genetic testing as part of nephronophthisis and ciliopathy studies conducted by Professor Hildebrandt in Boston. P1, P4, P5 and P8 were diagnosed in Genetic Clinic (Medical University of Silesia Hospital No.1, Zabrze) with methods presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Description of used methods in genetic testing among BBS patients.

| Patients’ ID | Genetic testing method |

|---|---|

| P1 | Sanger sequencing of BBS10, 2017 |

| P2 | NGS, 178 genes related to NPHP and ciliopathy, confirmation by Sanger sequencing, 2018 |

| P3 | NGS, 178 genes related to NPHP and ciliopathy, confirmation by Sanger sequencing, 2020 |

| P4 | WES, confirmation by Sanger sequencing, 2017 |

| P5 | Sibling of P4, Sanger sequencing of the target variant found previously in the sibling, 2021 |

| P6 | WES, confirmation by Sanger sequencing, 2020 |

| P7 | WES, analysis of 89 genes related to NPHP, confirmed via Sanger, 2015 |

| P8 | NGS, 16 genes related to Bardet-Biedl syndrome, confirmation by Sanger sequencing |

2.3. Literature review

We employed narrative approach for the literature review and aimed to encompass a comprehensive outline of genotype data pertinent to our patient cohort. Emphasis was placed on elucidating the diverse phenotypic manifestations linked to these genotypes. Special attention was dedicated to exploring the major symptoms and neurological abnormalities, especially their biological pathomechanism in BBS. This approach ensured a thorough understanding of the genotype-phenotype relationships relevant to our research objectives.

3. Description of the cases

In this article, we present eight pediatric patients with BBS with the confirmed mutation in BBS-related genes, observed in our clinical center. Each paragraph describes the patients in context of distinctive features of BBS.

3.1. Major and minor symptoms of BBS in pediatric patients

In this paragraph, we present the symptoms of BBS as observed in our patient cohort, highlighting the most frequently occurring manifestations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Major and minor symptoms of the Bardet-Biedl syndrome, marked for each patient.

| Symptoms | Patient ID/ occurrence of the features in patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major features | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 |

| Retinal cone-rod dystrophy |

+ | |||||||

| Central obesity | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Postaxial polydactyly | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Cognitive impairment | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| Hypogonadism and genitourinary abnormalities1 | + | + | ||||||

| Kidney disease | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Minor features | ||||||||

| Neurologic abnormalities | + | + | + | |||||

| Olfactory abnormalities | ||||||||

| Oral/dental abnormalities | + | + | ||||||

| Cardiovascular and other thoraco-abdominal abnormalities | + | |||||||

| Gastrointestinal abnormalities | + | |||||||

| Endocrine/metabolic abnormalities2 | + | |||||||

P - patient; 1-8 - numbers of the patients; 1 - in males: cryptorchidism, short scrotum, micropenis, and low testicular volume, suggesting the possibility of infertility1; in women - anatomical anomalies found were hypoplastic or duplex uterus, hypoplastic fallopian tubes and/or ovaries, septate vagina, partial or complete vaginal atresia, absent vaginal and/or urethral orifices, hydrocolpos/hydrometrocolpos, persistent urogenital sinus, and vesicovaginal fistula; 2 - metabolic syndrome, subclinical hypothyroidism, type II diabetes (T2DM), polycystic ovary syndrome.

3.2. Genotypes

Exact variant details of mutations present in our cohort and their ClinVar interpretatoin are listed in table below (Table 3).

Table 3.

Presentation of genotypes of patients with BBS.

| Patient ID | Sex | Gene | Zygosity | Variant details | ClinVar interpretation | Current age |

Age of the patient at the time of diagnosis | Clinical reason for genetic testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Male | BBS10 | Homozygous | NM_024685.4 (BBS10):c.145C>T (p.Arg49Trp) | Pathogenic/ likely pathogenic |

10 years 11 months |

4 years 6 months | obesity, polydactyly, psychomotor delay |

| P2 | Female | MKKS | Homozygous | NM_018848.3 (MKKS):c.1436C>G(p.(Ser479*)) | Pathogenic | 5 years 3 months |

8 months | obesity, polydactyly, abnormal image of kidneys on ultrasound |

| P3 | Male | MKKS | Homozygous | NM_018848.3(MKKS):c.1436C>G(p.(Ser479*)) | Pathogenic | 3 years 4 months |

2 months | abnormal image of kidneys on ultrasound, CKD, polydactyly siblings with BBS |

| P4 | Male | BBS10 | Heterozygous | NM_024685.4 (BBS10):c.424G>A (p.Asp142Asn) | Benign/ Likely benign |

13 years 8 months |

6 years | obesity, polydactyly, psychomotor delay, ASD |

| BBS7 | Homozygous | NM_176824.3 (BBS7):c.1967_1968delinsC (p.Leu656Profs*18) | Pathogenic | |||||

| P5 | Male | BBS10 | Heterozygous | NM_024685.4 (BBS10):c.424G>A (p.Asp142Asn) | Benign/ likely benign |

2 years 11 months |

2 months | abnormal image of kidneys on ultrasound, polydactyly, siblings with BBS |

| BBS7 | Homozygous | NM_176824.3 (BBS7):c.1967_1968delinsC (p.Leu656Profs*18) | Pathogenic | |||||

| P6 | Male | BBS7 | Compound heterozygous | NM_176824.3 (BBS7): c.1967_1968delinsC(p.(Leu656Profs*18)) | Pathogenic | 4 years 7 months |

9 months | abnormal image of kidneys on ultrasound, CKD, polydactyly, |

| P7 | Male | BBS7 | Compound heterozygous | NM_176824.3 (BBS7): c.754G>T(p.(Asp252Tyr)) | no data given | 7 years 2 months |

1 month | abnormal image of kidneys on ultrasound |

| BBS7 | Compound heterozygous | NM_176824.3 (BBS7): c.1967T>C(p.(Leu656Pro)) | no data given | |||||

| BBS7 | Compound heterozygous | NM_176824.3 (BBS7): c.280A>C(p.(Thr94Pro)) | no data given | |||||

| P8 | Female | BBS9 | Homozygous | NM_001033604.2 (BBS9):c.1687C>T | Pathogenic | 4 years | 2 years 6 months |

abnormal image of kidneys on ultrasound, polydactyly |

(CKD, chronic kidney disease; ASD, autism spectrum disorder).

3.3. Kidney and urinary system

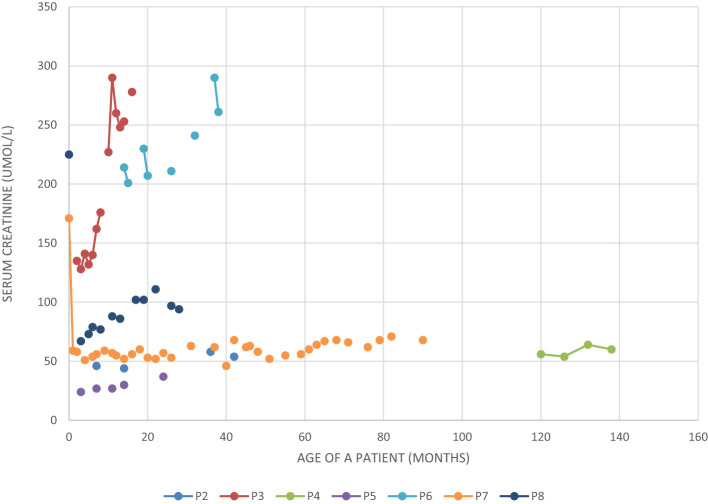

All the described patients developed symptoms related to the kidney and urinary system (Table 4). Patient P1 developed only kidney malformations. Seven patients (P2 – P8) developed both kidney malformations and chronic kidney disease (CKD), whereas in six of them those malformations were diagnosed prenatally (P2, P3, P5 – P8). Furthermore, laboratory tests showed increased serum creatinine levels in all our patients at some point of the disease duration, although chronic elevation was observed only in P3 and P6-P8 ( Figure 1 ). Patients P3 and P6 require regular dialysis and wait for kidney transplantation.

Table 4.

Presentation of symptoms of patients with BBS associated with kidney and urinary tract.

| Title 1 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset of kidney function impairment | 3 years | 2 years 8 months | 2 months | 10 years | 1 year 4 months | 1 year 3 months | 11 months | 3 months |

| CKD | Stage I | Stage II/III | Stage V | Stage I | Stage II | Stage V | Stage III | Stage IV |

| Prenatal ultrasound examination | dilated pelvicalyceal system | renal cysts | abnormal kidney structure with bilateral hydronephrosis | abnormal structure of the kidneys, bilateral hydronephrosis | dysplasia of both kidneys | fetal polycystic kidneys suspected | ||

| Kidney malformation (ultrasound examination) on diagnosis |

horseshoe kidney, periodic albuminuria | loss of cortico-medullary differentiation | dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system, (both kidneys), lack of corticomedullary differentiation, cyst in the right kidney | dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system (both kidneys), albuminuria | abnormal structure of both kidneys and dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system | left renal hypoplasia, loss of corticomedullary differentiation | Loss of corticomedullary differentiation, crossed renal ectopia | cysts in both kidneys |

| Others | hypertension | require regular dialysis, waiting for kidney transplantation | require regular dialysis, waiting for kidney transplantation | hypertension |

CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Figure 1.

Serum creatinine level in five patients with BBS and chronic kidney disease.

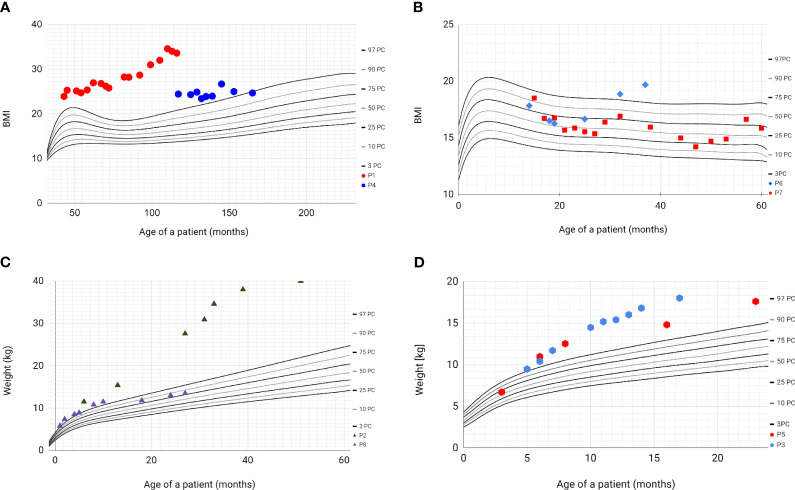

3.4. Obesity

All patients’ parents received dietary counselling and lifestyle intervention during each clinical encounter. Based on the history obtained from four patients (P1, P2, P3, P5), hyperphagia and a lack of satiety were observed. Over the course of the follow-up period, only one patient (P7) did not develop obesity, with the highest recorded BMI z-score reaching 0.55. Among these individuals, five had a notable increase in body weight ( Figure 2 ). In a solitary instance, represented by patients P4 and P8, a reduction in weight was observed. Notably, patient P1 was classified as having obesity class 3, denoted by a BMI z-score of 4.37, and additionally presented with multiple metabolic comorbidities, including metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), hypertension, insulin resistance, and dyslipidaemia.

Figure 2.

Percentile grids with BMI values and weight values of patients with BBS. Based on WHO Child Growth Standards 2007 WHO Reference. (A) - BMI values of patients P1 (red) and P4 (blue); (B) - BMI values of patients P6 (blue) and P7 (red); (C) - weight values of patients P2 (green) and P8 (purple); (D) - weight values of patients P3 (blue) and P5 (red).

Lipid metabolism disorders were confirmed by the results of laboratory tests, including those chronically elevated such as: concentration of total cholesterol (P1, P2, P7), triglycerides (P1, P2, P4, P6, P7), LDL cholesterol fraction (P1, P6). Patients also had elevated activity of alanine aminotransferase (P1) and aspartate aminotransferase (P6, P7).

3.5. Polydactyly

Postaxial polydactyly is one of the first symptoms noticed in infants with BBS. In our group, only two patients (P3 and P7) did not have additional toes or fingers. Polydactyly was treated surgically in each case.

3.6. Siblings

In our cohort there are two siblings (P2 and P3 - first pair of siblings; P4 and P5 - second pair of siblings).

The first siblings share the same mutation in MKKS gene. Although they share the same genotype, their phenotypes differ. The prenatal ultrasound examination was performed on both siblings (P2 and P3). Patient 2 had dilated pelvicalyceal system, whereas Patient 3 had kidney cysts. Furthermore, Patient 2 presents a slower progression of CKD compared to her brother ( Table 4 , Figure 1 ). Both live with obesity, but P2 shows a greater weight gain than her brother ( Figures 2C, D ) Furthermore, the girl (P2) is exhibiting age- appropriate intellectual development, attending a standard preschool program, while her younger brother (P3) presents with delayed psychomotor development. The polydactyly was present in both ( Table 5 ). At the moment, P2 presents only 3 large symptoms of BBS, whereas in her younger brother 5 of 6 large symptoms of BBS are observed ( Table 2 ).

Table 5.

Presentation of polydactyly in patients with BBS.

| Title 1 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessory VI toe (left foot) | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| Accessory VI toe (right foot) | + | + | + | |||||

| Accessory VI finger on a right hand | + | |||||||

| Accessory VI finger on a left hand | + | |||||||

| Underdeveloped accessory fingers | + | + |

The second siblings seem to be more difficult to compare due to the greater age difference between two brothers (in siblings 1 the age difference is 2 years, in siblings 2 – 11 years). However, both fulfil the clinical criteria of BBS without any doubt. The patients carry the same homozygous pathogenic mutation in the BBS7, as well heterozygous mutation in the BBS10 gene, identified as benign/likely benign.

The ultrasound examination performed on the older brother (P4) showed a slight asymmetry of the kidneys, enlargement of the pelvicalyceal system, while the prenatal ultra-sound of Patient 5 revealed abnormal kidney structure and enlarged pelvicalyceal system ( Table 4 ). They both developed CKD at various stages (P4 – CKD stage I, P5 – CKD stage II). Cognitive impairment was noted in both cases, with a delayed onset of speech observed in P5, and a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder in P4. Additionally, imaging studies confirmed the partial empty sella syndrome without clinical manifestations.

4. Discussion and literature review

BBS is a rare disease; hence, the existing literature may be lacking a thorough picture of this syndrome. Scarce data on the subject makes it difficult to precisely identify gaps in our knowledge. We believe this study can aid this effort as our cohort comprises early-diagnosed children. Although some of the patients share the same genotype, theirs phenotypes vary. Throughout this paper, we compare and investigate those differences. Moreover, our data provides useful insight into mutation-symptom correlation as our cohort represents some unique genetic mosaic incorporating, benign, recessive and pathogenic genes. We gathered longitudinal data on the BBS development in our patients using both prospective and retrospective methods, and we synthesize approaches from different medical faculties. Additionally, we decided to delve into the relationship between phenotype and genotype in BBS, as this topic is currently being explored by other authors as well (10).

We focused on the primary BBS symptoms. The first ones noted based in patients’ history were polydactyly and urinary system disorders. However, these symptoms did not serve as a basis for initiating early diagnosis. The key features that guided physicians toward a BBS diagnosis were polydactyly (in anamnesis), obesity and kidney disease. Regarding the most frequently occurring BBS features, we noted: retinitis pigmentosa (1 patient), obesity (6 patients), kidney disease (8 patients), and developmental delay (6 patients), thus making these features the main topic of this section.

We also observed a few minor features in our patients. Neurological abnormalities were present in three patients (P1, P4, P8). Given their frequent association with cognitive impairment and the abundance of available research data, we summarized these findings in the discussion section. In two patients (P6 and P8) we identified oral abnormalities in the form of micrognathism (P6) and hypoplastic teeth (P8). Furthermore, among the eldest patients, we identified gastrointestinal abnormalities (gastroesophageal reflux disease in P4) and metabolic disturbances (metabolic-associated liver disease, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome in P1). Due to the limited occurrence of these features in only a few patients, we have decided not to elaborate on them further.

4.1. Diagnostic process

According to literature the typical age of the BBS diagnosis varies from 8 to 9 years among pediatric population (11). However, the age of the child at the time of diagnosis may depend on the clinical vigilance of the healthcare provider as well as the main or leading feature of the BBS. The initial symptoms of this syndrome may manifest considerably earlier. Notably, in our study, the average age at which BBS was diagnosed was 22 months [range: 1 month to 6 years], a significantly earlier age, owing to the collaborative efforts of an experienced interdisciplinary team. Numerous prenatal changes can be observed in fetuses with BBS. Among the most frequently described are hyperechogenic kidneys, polydactyly, enlarged kidneys, renal cysts, hydronephrosis and hydrometrocolpos (12–22). However, there is no consensus on which of these features is the most characteristic of BBS.

In a study conducted by Simonini et al., 94.7% of patients with ciliopathies exhibited hyperechoic kidneys, while in fetuses with BBS, the primary renal abnormality was often hydronephrosis. According to this study, genitourinary abnormalities appear to dominate in cases of BBS. Additionally, authors reported that the presence of large hyperechoic kidneys, mimicking sonographic features of infantile polycystic kidney, is a suggestive sign of BBS, a finding also noted by Mary and others (13, 21). When considering only ultrasound (US) detection in fetuses with enlarged and/or renal cysts, the recognition of BBS ranges from 0.3% to 12% (21). In our cohort, kidneys anomalies were present in 6 patients during the prenatal US.

Current literature highlights that the majority of limb abnormalities can be effectively identified in the early stages of pregnancy. This detection of limb abnormalities holds significant clinical importance, given their frequent association with serious underlying disorders, a risk that may be further elevated in fetuses presenting with concurrent abnormalities (12). None of our patients has the prenatal diagnosis of polydactyly.

The most prevalent symptoms detected in our patient cohort at the time of diagnosis included kidney disease, which was present in all individuals, and polydactyly (observed in 6 patients). Subsequently, during follow-up, nearly all patients exhibited excessive body weight and experienced delays in intellectual development (6 out of 8). Additionally, our study revealed that initial symptoms present before BBS diagnosis, such as prenatal manifestations of kidneys and urinary system defects and postnatal occurrences of polydactyly, were observed. It is noteworthy, however, that only a minority of our patients received a diagnosis at such an early stage.

The diagnostic process was significantly shorter among siblings. Based on first siblings’ family history, polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease (ADTKD) could have been easily excluded, which limited differentiation for the P3. In second siblings, P5 was diagnosed at the age of 4 months according to prenatal US and older brother with BBS. Within our cohort, all patients received BBS confirmation through genetic testing, yet two of them (P2 and P7) did not meet the clinical diagnostic criteria. Nonetheless, this does not preclude the possibility of new symptoms being observed in them in the future. It is possible that P2 and P7 may not exhibit the full BBS phenotype, necessitating a revision of their diagnosis.

4.2. Genotype-phenotype association

Bardet-Biedl syndrome is a complex multifactorial disease, which is clearly visible in our cases presentations. The occurrence and severity of symptoms differ based on the developed phenotype which is associated with each mutation. Most of our patients’ phenotype corresponds with their genotype according to the literature ( Table 6 ) (3). In P1, with the mutation in BBS10, retinopathy manifested early and more metabolic abnormalities were observed compared to other patients. Both patients with mutations in the BBS7 (P4, P5, P6) and BBS9 (P8) exhibited a high penetrance of renal anomalies and CKD, characteristics associated with these respective genotypes in the literature. Given the young age of the patients, determining the occurrence of other mutation-associated symptoms requires longer observation.

Table 6.

Genotype-phenotype association.

| Mutated gene | Literature findings | Patient’s symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| BBS6/MKKS |

|

P2: obesity, polydactyly, CKD stage II/III, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia |

| P3: obesity, polydactyly, CKD stage V, psychomotor delay, cryptorchidism | ||

| BBS7 | P4: obesity (in the past), polydactyly, CKD stage I, psychomotor delay, ASD, hypertriglyceridemia, astigmatism, myopia | |

| P5: obesity, polydactyly, CKD stage II, psychomotor delay, micropenis, , astigmatism, myopia | ||

| P6: obesity, polydactyly, CKD stage V, psychomotor delay, micrognathism, hypertriglyceridemia | ||

| P7: CKD stage III, psychomotor delay, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia astigmatism, myopia | ||

| BBS9 |

|

P8: obesity (in the past), polydactyly, CKD stage IV, hypertension, hypoplastic teeth |

| BBS10 |

|

P1: retinal cone-rod dystrophy, obesity, polydactyly, CKD stage I, psychomotor delay, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease, hypertension, insulin resistance hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridaemia |

MCH receptor, melanin-concentrating hormone receptors; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ASD, atrial septal defect; T2D, type 2 diabetes mellitus, BMI, body mass index.

4.3. Kidneys and urinary system

All of the described patients developed symptoms related to the kidney and urinary system, and, it is worth noting that it may result from the close collaboration between endocrinologists and nephrologists in our medical center, enhancing our vigilance in diagnosing patients with BBS.

Kidney malfunctions and malformations are the major causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with BBS, however, their severity varies depending on the mutation variant (28). In our cohort, renal impairment is associated with higher number of hospitalizations compared to the other consequences of BBS. In the case of renal phenotypes, confirming complete concordance with previously described mutations proves challenging. Two patients with CKD stage V harbor mutations in the MKKS/BBS6 and BBS7 genes. Mutations in these genes have also been documented in other patients with varying (milder) degrees of renal disease. This observation leads to the hypothesis that not only mutations in specific genes may be associated with these phenotypes but the combination of those mutations and environmental factors. According to Zacchia et al. patients with BBS can be divided into two groups based on the kidney disease occurrence. The first includes patients with kidney and urinary tract malformations diagnosed in early childhood, while the second comprises adult patients with no clear onset symptoms suggesting CKD (29, 30). Confirmation of this hypothesis requires longer-term observation of our patients. However, even now, we can distinguish two groups in our study: patients with rapidly progressing CKD (P2, P3, P5, P6, P7, P8) and those with slowly progressing renal impairment (P1 and P4). In contrast, Cognard et al. suggest that the kidney malfunction in BBS is caused by age-related decreasing of glomeruli function rather than early-onset glomerulopathy. Moreover, the results of animal studies showed that the tissue-specific BBS10 mutation, confined within the renal epithelium, did not result in renal abnormalities. In 3-month-old mice without obesity, inactivation of BBS10 had no major effect on renal function (31). This allows us to formulate an additional hypothesis regarding the influence of certain BBS features on others. Our findings may suggest such relationship in our patients. However, we cannot confirm the existence of this dependency, given the influence of factors such as frequent preschool-age infections, which also exacerbated the underlying condition. Given the rarity of the disease and the lack of long-term studies, it is difficult to clearly identify risk factors for the progression of kidney disease in patients with BBS. The conclusions drawn by the researchers emphasize the importance and the need for long-term follow-up of patients with this disease.

4.4. Obesity

Central obesity occurs in 89% of patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome (1). According to Pomeroy et al. infants delivered at term may not exceed the weight of 4000g, however, in more than half obesity may appear even before the age of two and increased weight gain is particularly evident in the preschool age (26). These observations align with the circumstances of our cases. The birth weights of our patients ranged from 3234 to 3850g. Consistently to the data presented in Figure 2 , excessive body weight was also evident in patients during early childhood.

Obesity is one of the main therapeutic challenges while handling patients with BBS. Those individuals have deficits in the melanocortin-related signaling pathway, responsible for the feeling of satiety, which leads to increased food intake, a phenomenon that was observed in four of our patients as hyperphagia. A hypothesis regarding the aetiology of obesity in individuals with BBS centers on the compromised membrane expression of the leptin receptor (LepRB) within hypothalamic cells. Leptin, exerts its effects by binding to its receptor in the brain, ultimately leading to reduced food intake and heightened energy expenditure. Genetic modifications affecting LepRB can potentially enhance signaling pathways associated with the onset of obesity (32, 33). Given the cause of obesity in BBS, setmelanotide seems to be a good therapeutic option. It is a melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) agonist that was initially meant for the treatment of some forms of monogenic obesity. In 2022y it was approved in therapy of BBS as well, based on the results of clinical trial in this matter (34–36). Recent findings of the phase 3 clinical trial suggest that patients diagnosed with BBS experienced a substantial reduction in both weight and BMI z-score after one year of treatment with setmelanotide. Specifically, there was a notable decrease in weight, ranging as high as -7.6% change from baseline in patients aged 18 years and older as well as significant reduction in the BMI z-score by -0.75 points from baseline in patients below the age of 18 (37). We aspire to incorporate this treatment into our treatment regimen for P1, considering the limited efficacy of behavioral interventions in addressing his obesity and its associated complications. The rest of our obese patients are not qualified for setmelanotide treatment due to their young age and/or severe CKD.

Other evidence suggests that the BBSome plays a pivotal role in influencing the sensitivity of neuronal responses to bone morphogenetic protein 8B (BMB-8B). The potential mechanism linking the BBS1 gene to the development of obesity is further substantiated by the observation of impaired central BMP-8B responsiveness in mice harboring a single missense mutation in the BBS1 gene (38).

Increased adipogenesis may be caused by the dysfunction of primary cilia which is crucial in pre-adipocyte differentiation. Marion et al. discovered the occurrence of transient ciliary formation carrying Wnt and Hh receptors during adipogenesis. Inhibition of BBS10 and BBS12 expression weakens ciliogenesis and activates the GSK3 and PPARγ related proadipogenic pathways. Additionally, these studies showed increased fat accumulation and higher leptin levels in adipocytes derived from skin fibroblasts of BBS patients compared to the control sample (39). This data may account for the limited effectiveness of interventions in patient P1, who, despite several years of treatment, did not achieve significant improvement.

The extent of hyperplasia and hypertrophy within adipose tissue is age-dependent and exhibits fluctuations over the lifespan. Notably, there is a rapid occurrence of hyperplasia and hypertrophy during early childhood (0–2 years) and adolescence (12– 18 years). However, as demonstrated in longitudinal and cross-sectional investigations conducted by Knittle et al. and other researchers, there tends to be a relative stabilization of hyperplasia during adulthood (40, 41). This may offer some hope for mitigating adult weight gain in patients. A healthier metabolic profile is indicated by the presence of numerous smaller adipocytes, which correlates with heightened insulin sensitivity, reduced levels of inflammation, and diminished ectopic lipid accumulation (42–44). Conversely, extreme states of hypertrophic obesity are marked by diminished hyperplasia and augmented hypertrophic expansion, thereby exacerbating the onset of obesity-related comorbidities (45). We are concerned about the emergence of such effects in our patients. Combined with the lack of satiety as described earlier, it can lead to the rapid development of complications such as type II diabetes, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease.

4.5. Retinal code-rode dystrophy

The most frequently presented symptom of BBS is retinal cone-rod dystrophy, but other dysfunctions are also described such as nyctalopia, which is usually evident by age 7 to 8 (25). Due to the young age of our patients, the examination revealed the presence of visual impairments, primarily myopia and astigmatism. Dystrophy was observed only in P1. Gradual decline in peripheral vision, diminished color discrimination, and deterioration of visual acuity are observable as the condition progresses. In most cases, individuals reach the status of legal blindness during their second or third decade of life (5, 46). Additional ocular phenotypes documented in the literature encompass central cone-rod dystrophy, widespread severe retinal dystrophy, and choroidal dystrophy (25). Initial assessment might pose challenges due to cognitive impairment (diagnosed in 66% of cases) and the age- related lack of compliance in patients. These factors influence parental observations during our patients’ ophthalmological examinations. Clinicians should also consider the possibility of an inverse relationship, i.e. developmental delay as a result of the visual impairment (1).

4.6. Cognitive impairment and neurological abnormalities

Findings regarding cognitive performance in individuals diagnosed BBS vary considerably. For instance, among 21 children who were examined, three demonstrated unimpaired IQ, eleven exhibited intellectual disabilities, and ten had mild intellectual impairments (47). Research conducted on a group of adult patients (n = 34, aged 17–53 years) revealed that 26% of them had intellectual disabilities, with one patient even exhibiting an IQ above 120 (48). In a group of our patients, psychomotor delay was observed in six of them. Primarily, it pertained to speech delay (P1, P3, P5, P6,P7) and muscle hypotonia (P3, P6, P7). Additionally, limited studies conducted thus far have documented anxiety, decreased social dominance, and deficiencies in associative learning in BBS2 and 4 knockout mice. These effects are partially attributed to impaired neurogenesis (49–51).

In the research conducted by Rodig and others BBS6/MKKS and BBS8/TTC8 knockout mice exhibited decreased anxiety levels. Furthermore, they observed reductions in social behavior and alterations in communication. The genotype did not impact learning skills (52). In more recent findings, a mouse model for Ccdc28b, a modifier of BBS, was found to exhibit characteristics associated with obsessive-compulsive behavior and mild social behavior alterations (53).

In our patient cohort, autistic behaviors were observed in two individuals (P1 and P4), encompassing restricted eye contact, speech delay, motor stereotypies and aggressive tendencies. There are several human studies involving patients with BBS, which provide evidence of autistic behavior in this population. A study conducted by Kerr and colleagues revealed autistic traits in 77% of the participants under investigation (54). In a study on BBS patients aged between 2 and 61 years, 80% of participants have shown social deficits (55). Barnett and colleagues’ report similarly noted that externalizing behaviors like aggression were infrequently observed in a group of 21 children diagnosed with BBS. However, issues with social behavior were prevalent. It is worth noting that hearing abnormalities were observed in 2 of our patients (P1 and P6), potentially leading to erroneous conclusions regarding the presence of speech delays and autistic traits, solely arising from hearing impairment. Nonetheless, it remains unclear whether social difficulties in human patients are primarily attributed to the ciliopathy itself or if they are secondary consequences resulting from sensory deficits or social ostracism.

5. Conclusions

Bardet-Biedl syndrome encompasses a wide range of clinical features, even within patients who share the same genetic mutations. Common features of BBS may not be considered out of the ordinary nowadays, therefore postponing the diagnosis. Recognizing these diverse clinical presentations is crucial. The constellation of symptoms such as polydactyly and/or kidney disorders and/or early-onset obesity, if present, should trigger the clinicians’ vigilance and consideration of the BBS diagnosis. In some cases, the presence of an affected older sibling can be a key diagnostic indicator, emphasizing the importance of a comprehensive family medical history in diagnosis. We identified mutations in various BBS-related genes, highlighting the genetic complexity of the condition. Furthermore, it revealed that even siblings with identical mutations may have distinct clinical presentations. Our findings stress the importance of early diagnosis and comprehensive care in managing BBS. Despite differences in symptoms presentations, all BBS genotypes lead to disability and multi-systemic dysfunctions. Early diagnosis allows for timely monitoring of patients’ condition, enabling interventions that can prevent or mitigate potential ramifications. Understanding the intricate clinical manifestations and genetic diversity in BBS is essential for better supporting individuals with this rare genetic condition and improving their outcomes.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical University of Silesia in Katowice (BNW/NWN/0052/KB/88/24, 16.04.2024).

Author contributions

MN-C: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Conceptualization. MC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. AT: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation. FH: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. TK: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. KD: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. KL: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SS: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. MS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization. AZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Forsythe E, Beales PL. Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. (2013) 21:8–13. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. U.S. National Library of Medicine . Bardet-Biedl Syndrome: Medlineplus Genetics. MedlinePlus (2020). Available online at: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/bardet-biedl-syndrome/#frequency (Accessed January 27, 2022).

- 3. Niederlova V, Modrak M, Tsyklauri O, Huranova M, Stepanek O. Meta-analysis of genotype-phenotype associations in Bardet-Biedl syndrome uncovers differences among causative genes. Hum Mutat. (2019) 40:2068–87. doi: 10.1002/humu.23862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Florea L, Caba L, Gorduza EV. Bardet-Biedl syndrome-multiple kaleidoscope images: insight into mechanisms of genotype-phenotype correlations. Genes (Basel). (2021) 12. doi: 10.3390/genes12091353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weihbrecht K, Goar WA, Pak T, Garrison JE, DeLuca AP, Stone EM, et al. Keeping an eye on Bardet-Biedl syndrome: A comprehensive review of the role of Bardet-Biedl syndrome genes in the eye. Med Res Arch. (2017) 5. doi: 10.18103/mra.v5i9.1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reiter JF, Leroux MR. Genes and molecular pathways underpinning ciliopathies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2017) 18:533–47. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wójcicka K, Pac- Kożuchowska E. Occurrence of metabolic syndrome among children with the selected genetic disorder. Pediatr Endocrinol. (2013) 4. doi: 10.18544/EP-01.12.04.1468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wheway G, Nazlamova L, Hancock JT. Signaling through the primary cilium. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2018) 6:8. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Álvarez-Satta M, Castro-Sánchez S, Valverde D. Bardet-Biedl syndrome as a chaperonopathy: dissecting the major role of chaperonin-like BBS proteins (BBS6-BBS10-BBS12). Front Mol Biosci. (2017) 4:55. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2017.00055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deveault C, Billingsley G, Duncan JL, Bin J, Theal R, Vincent A, et al. BBS genotype-phenotype assessment of a multiethnic patient cohort calls for a revision of the disease definition. Hum Mutat. (2011) 32:610–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.21480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beales PL, Elcioglu N, Woolf AS, Parker D, Flinter FA. New criteria for improved diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome: results of a population survey. J Med Genet. (1999) 36):437–46. doi: 10.1136/jmg.36.6.437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meyer JR, Krentz AD, Berg RL, Richardson JG, Pomeroy J, Hebbring SJ, et al. Kidney failure in Bardet–Biedl syndrome. Clin Genet. (2022) 101:429–41. doi: 10.1111/cge.14119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Simonini C, Floeck A, Strizek B, Mueller A, Gembruch U, Geipel A. Fetal ciliopathies: a retrospective observational single-center study. Arch Gy-necol Obstet. (2022) 306:71–83. doi: 10.1007/s00404-021-06265-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simonini C, Fröschen E-M, Nadal J, Strizek B, Berg C, Geipel A, et al. Prenatal ultrasound in fetuses with polycystic kidney appearance - expanding the diagnostic algorithm. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2023) 308:1287–300. doi: 10.1007/s00404-022-06814-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vila Real D, Nogueira R, Sá J, Godinho C. Prenatal diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome: a multidisciplinary approach. BMJ Case Rep. (2021) 14. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-238445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ashkinadze E, Rosen T, Brooks SS, Katsanis N, Davis EE. Combining fetal sonography with genetic and allele pathogenicity studies to secure a neonatal diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Clin Genet. (2013) 83:553–9. doi: 10.1111/cge.12022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dar P, Sachs GS, Carter SM, Ferreira JC, Nitowsky HM, Gross SJ. Prenatal diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome by targeted second-trimester sonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. (2001) 17:354–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2001.00253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jing X-Y, Jiang F, Li D-Z. Unmasking a recessive allele by a deletion: Early prenatal diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome in a Chinese family. Congenit Anom (Kyoto). (2021) 61:138–9. doi: 10.1111/cga.12413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li Q-Y, Huang L-Y, Li D-Z. Early prenatal detection of Bardet-Biedl syndrome in a case with postaxial polydactyly and hyperechoic kidneys confirmed by next generation sequencing. Congenit Anom (Kyoto). (2019) 59:142–4. doi: 10.1111/cga.12306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ma G-C, Lim ZW, Lee M-H, Chang S-P, Chang T-Y, Chen M. Fetal ascites in third trimester as novel prenatal finding in Bardet-Biedl syndrome and subsequent unaffected live birth assisted by preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. (2023) 61:649–51. doi: 10.1002/uog.26114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mary L, Chennen K, Stoetzel C, Antin M, Leuvrey A, Nourisson E, et al. Bardet-Biedl syndrome: Antenatal presentation of forty-five fetuses with biallelic pathogenic variants in known Bardet-Biedl syndrome genes. Clin Genet. (2019) 95:384–97. doi: 10.1111/cge.13500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parlakgumus A, Yalcinkaya C, Kilicdag E. Prenatal diagnosis of McKusick-Kaufman/Bardet-Biedl syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. (2011) 2011. doi: 10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang Q, Nishimura D, Vogel T, Shao J, Swiderski R, Yin T, et al. BBS7 is required for BBSome formation and its absence in mice results in Bardet-Biedl syndrome phenotypes and selective abnormalities in membrane protein trafficking. J Cell Sci. (2013) 126:2372–80. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeziorny K, Antosik K, Jakiel P, Młynarski W, Borowiec M, Zmysłowska A. Next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome-new variants and relationship with hyperglycemia and insulin re-sistance. Genes (Basel). (2020) 11:1283. doi: 10.3390/genes11111283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Denniston AK, Beales PL, Tomlins PJ, Good P, Langford M, Foggensteiner L, et al. Evaluation of visual function and needs in adult patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Retina. (2014) 34:2282–9. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pomeroy J, Krentz AD, Richardson JG, Berg RL, VanWormer JJ, Haws RM. Bardet-Biedl syndrome: Weight pat-terns and genetics in a rare obesity syndrome. Pediatr Obes. (2021) 16:e12703. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feuillan PP, Ng D, Han JC, Sapp JC, Wetsch K, Spaulding E, et al. Patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome have hyperleptinemia suggestive of leptin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2011) 96:E528–35. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zacchia M, Di Iorio V, Trepiccione F, Caterino M, Capasso G. The kidney in Bardet-Biedl syndrome: possible pathogenesis of urine concentrating defect. Kidney Dis (Basel). (2017) 3:57–65. doi: 10.1159/000475500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zacchia M, Del Blanco FDV, Torella A, Raucci R, Blasio G, Onore ME, et al. Urine concentrating defect as presenting sign of progressive renal failure in Bardet-Biedl syndrome patients. Clin Kidney J. (2021) 14:1545–51. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfaa182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zacchia M, Capolongo G, Trepiccione F, Marion V. Impact of local and systemic factors on kidney dysfunction in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Kidney Blood Press Res. (2017) 42:784–93. doi: 10.1159/000484301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cognard N, Scerbo MJ, Obringer C, Yu X, Costa F, Haser E, et al. Comparing the Bbs10 complete knockout phenotype with a specific renal epithelial knockout one highlights the link between renal defects and systemic inactivation in mice. Cilia. (2015) 4:10. doi: 10.1186/s13630-015-0019-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guo D-F, Cui H, Zhang Q, Morgan DA, Thedens DR, Nishimura D, et al. The BBSome controls energy homeostasis by mediating the transport of the leptin receptor to the plasma membrane. PloS Genet. (2016) 12:e1005890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rouabhi M, Guo DF, Morgan DA, Zhu Z, López M, Zingman L, et al. BBSome ablation in SF1 neurons causes obesity without comorbidities. Mol Metab. (2021) 48:101211. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Our Pipeline - Rhythm Pharmaceuticals (2022). Available online at: https://www.rhythmtx.com/ourpipeline/#:~:text=Rhythm's%20Pipeline,deficits%20in%20the%20MC4R%20pathway.

- 35. Büscher AK, Cetiner M, Büscher R, Wingen A-M, Hauffa BP, Hoyer PF. Obesity in patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome: influence of appetite-regulating hormones. Pediatr Nephrol. (2012) 27:2065–71. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2220-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Out Of Rhythm: Setmelanotide Lacks Proper Placebo Controls And Has Plenty Of Adverse Events (NASDAQ:RYTM) (2022). Available online at: https://seekingalpha.com/article/4303725-out-of-rhythm-setmelanotide-lacks-proper-place-bo-controls-and-plenty-of-adverse-events.

- 37. Haqq AM, Chung WK, Dollfus H, Haws RM, Martos-Moreno GÁ, Poitou C, et al. Efficacy and safety of setmelanotide, a melanocortin-4 receptor agonist, in patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome and Alström syndrome: A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, place-bo-controlled, phase 3 trial with an openLabel period. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2022) 10:859–68. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00277-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rial-Pensado E, Freire-Agulleiro O, Ríos M, Guo DF, Contreras C, Seoane-Collazo P, et al. Obesity induces resistance to central action of BMP8B through a mechanism involving the BBSome. Mol Metab. (2022) 59:101465. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marion V, Stoetzel C, Schlicht D, Messaddeq N, Koch M, Flori E, et al. Transient ciliogenesis involving Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins is a funda-mental characteristic of adipogenic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2009) 106:1820–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812518106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Knittle JL, Timmers K, Ginsberg-Fellner F, Brown RE, Katz DP. The growth of adipose tissue in children and adolescents. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of adipose cell number and size. J Clin Invest. (1979) 63:239–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI109422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sakers A, De Siqueira MK, Seale P, Villanueva CJ. Adipose-tissue plasticity in health and disease. Cell. (2022) 185:419–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Strissel KJ, Stancheva Z, Miyoshi H, Perfield JW, DeFuria J, Jick Z, et al. Adipocyte death, adipose tissue remodeling, and obesity complications. Diabetes. (2007) 56:2910–8. doi: 10.2337/db07-0769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nishimura S, Manabe I, Nagasaki M, Seo K, Yamashita H, Hosoya Y, et al. In vivo imaging in mice reveals local cell dynamics and inflammation in obese adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. (2008) 118:JCI33328. doi: 10.1172/JCI33328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weyer C, Foley JE, Bogardus C, Tataranni PA, Pratley RE. Enlarged subcutaneous abdominal adipocyte size, but not obesity itself, predicts type II diabetes independent of insulin resistance. Diabetologia. (2000) 43:1498–506. doi: 10.1007/s001250051537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jo J, Gavrilova O, Pack S, Jou W, Mullen S, Sumner AE, et al. Hypertrophy and/or hyper-plasia: dynamics of adipose tissue growth. PloS Comput Biol. (2009) 5:e1000324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Forsyth RL, Gunay-Aygun M. Bardet-Biedl syndrome overview. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle: (2003). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1363/. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barnett S, Reilly S, Carr L, Ojo I, Beales PL, Charman T. Behavioural phenotype of Bardet-Biedl syndrome. J Med Genet. (2002) 39:e76. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.11.e76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bennouna-Greene V, Kremer S, Stoetzel C, Christmann D, Schuster C, Durand M, et al. Hippocampal dysgenesis and variable neuropsychiatric phenotypes in patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome underline complex CNS impact of primary cilia. Clin Genet. (2011) 80:523–31. doi: 10.1111/j.13990004.2010.01541.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Eichers ER, Abd-El-Barr MM, Paylor R, Lewis RA, Bi W, Lin X, et al. Phenotypic characterization of Bbs4 null mice reveals age-dependent penetrance and variable expressivity. Hum Genet. (2006) 120:211–26. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0197-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fath MA, Mullins RF, Searby C, Nishimura DY, Wei J, Rahmouni K, et al. Mkks-null mice have a phenotype resembling Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. (2005) 14:1109–18. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nishimura DY, Fath M, Mullins RF, Searby C, Andrews M, Davis R, et al. Bbs2-null mice have neurosensory deficits, a defect in social dominance, and retinopathy associated with mislocalization of rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2004) 101:16588–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405496101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rödig N, Sellmann K, dos Santos Guilherme M, Nguyen VTT, Cleppien D, Stroh A, et al. Behavioral phenotyping of bbs6 and bbs8 knockout mice reveals major alterations in communication and anxiety. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:14506. doi: 10.3390/ijms232314506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pak TK, Carter CS, Zhang Q, Huang SC, Searby C, Hsu Y, et al. A mouse model of Bardet-Biedl Syndrome has impaired fear memory, which is rescued by lithium treatment. PLoS Genet. (2021) 17:e1009484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kerr EN, Bhan A, Heon E. Exploration of the cognitive, adaptive and behavioral functioning of patients affected with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Clin Genet. (2016) 89:426–33. doi: 10.1111/cge.12614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brinckman DD, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Blumhorst C, Biesecker LG, Sapp JC, Johnston JJ, et al. Cognitive, sensory, and psychosocial characteristics in patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. (2013) 161A:2964–71. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]