Abstract

Importance

Bovine mastitis, predominantly associated with gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus, poses a significant threat to dairy cows, leading to a decline in milk quality and volume with substantial economic implications.

Objective

This study investigated the incidence, virulence, and antibiotic resistance of S. aureus associated with mastitis in dairy cows.

Methods

Fifty milk-productive cows underwent a subclinical mastitis diagnosis, and the S. aureus strains were isolated. Genomic DNA extraction, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis were performed, supplemented by including 124 S. aureus genomes from cows with subclinical mastitis to enhance the overall analysis.

Results

The results revealed a 42% prevalence of subclinical mastitis among the cows tested. Genomic analysis identified 26 sequence types (STs) for all isolates, with Mexican STs belonging primarily to CC1 and CC97. The analyzed genomes exhibited multidrug resistance to phenicol, fluoroquinolone, tetracycline, and cephalosporine, which are commonly used as the first line of treatment. Furthermore, a similar genomic virulence repertoire was observed across the genomes, encompassing the genes related to invasion, survival, pathogenesis, and iron uptake. In particular, the toxic shock syndrome toxin (tss-1) was found predominantly in the genomes isolated in this study, posing potential health risks, particularly in children.

Conclusion and Relevance

These findings underscore the broad capacity for antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity by S. aureus, compromising the integrity of milk and dairy products. The study emphasizes the need to evaluate the effectiveness of antibiotics in combating S. aureus infections.

Keywords: S. aureus, bovine mastitis, virulence factors, multi-resistant genes, genomics

INTRODUCTION

The dairy industry has significant global importance, given its impact on the economy, food safety, and poverty reduction [1]. In Mexico, the livestock industry, including milk production, plays a vital economic role, contributing approximately 55% to the gross domestic product (GDP). The Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografia (INEGI) reported that 45.3% of bovine production is allocated to raising calves or milk production [2]. Despite the challenges posed by the emergence of lifestyles favoring plant-based milk consumption, cow milk production in Mexico has exhibited positive growth, showing an upward trend from 2019 to 2022, reaching 13,279 million liters [3].

Udder health is of paramount concern in the dairy industry owing to the high susceptibility of the mammary gland to microbial infections, leading to bovine mastitis. This condition results from the prevalence of various microorganisms in the milk production chain, encompassing the field environment and milking process [4]. Mastitis is an inflammatory process in the udder resulting from an immunological response. It can be categorized as clinical or subclinical. Clinical mastitis is characterized by a sudden inflammatory reaction, presenting as redness and swelling in the mammary gland. In addition, clinical mastitis can compromise milk quality and adversely impact reproductive efficiency in cows [5,6]. Subclinical mastitis may be present without visible manifestations in the udder or milk but can contribute to a gradual reduction in milk production over time [7]. The main causative agents of mastitis include Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter aerogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus uberis, and Staphylococcus aureus. Among these, S. uberis and S. aureus are the most significant pathogens associated with mammary gland inflammation [8].

S. aureus is one of the most prevalent causative agents of mastitis worldwide, with isolation frequencies ranging from 7.4% to 24.1% [4,8]. A notable characteristic contributing to the prevalence of S. aureus in the udder is its capacity for biofilm formation during bovine mastitis. This ability facilitates long-term establishment, impacting the efficacy of antimicrobials [9]. The main therapy for subclinical mastitis is antibiotics. On the other hand, numerous studies have reported resistance profiles in S. aureus strains isolated from bovine mastitis, encompassing antibiotics such as ampicillin, amoxicillin, tetracycline, penicillin, and gentamicin [10]. Strains exhibiting this resistance phenotype are designated as methicillin (oxacillin)-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [11]. These organisms often display resistance to first-choice antimicrobial agents and aminoglycosides, macrolides, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolones, indicating that the multidrug resistance pattern was likely conferred by a multitude of different virulence factors [12].

The advent of bioinformatics tools and the availability of genomic sequences in public repositories enable comprehensive studies and comparisons of the genomic aspects related to the basic biology of epidemiologically significant bacteria, such as S. aureus. Owing to the substantial relevance of this pathogen in the dairy industry, this study examined the prevalence, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance genes in S. aureus strains associated with bovine mastitis within dairy herds in the central area of Sinaloa, Mexico. This investigation aims to provide invaluable insights into the status of S. aureus, allowing the implementation of effective measures to mitigate the negative impact on animal health and microbiological contamination in the dairy industry.

METHODS

Mastitis diagnosis and sample collection

A subclinical mastitis diagnosis was conducted on dairy cows from a local farm in the Central Valley of Culiacan, Sinaloa, Mexico, using the Commercial California Mastitis Test (CMT, Sanfer, Mexico), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, milk samples from each mammary quarter (50 cows) were placed aseptically in separate wells of a plastic paddle and mixed with surfactant (sodium lauryl sulfate) and colorant (bromocresol blue) reagents. The plate underwent gentle rotation to develop the reaction. The degree of mastitis was determined by a visual examination, considering grume, clot, or gel formation, as well as any color changes in the sample. The scores were assigned as follows: N (negative reaction), T (positive weak color changes and small grume presence), 1 (viscous mixture without gel), 2 (immediate gel formation), and 3 (strong gel production).

The milk from the positive quarters (T-3 mastitis grade) was collected in sterile flasks and transported to the National Laboratory for Research in Food Safety (LANIIA) under refrigerated conditions for further analysis.

Isolation and characterization of S. aureus strains

The culture conditions and S. aureus isolation protocols adhered to the guidelines outlined in NOM-210-SSA1-2014. Briefly, 25 mL of milk was added to 225 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and homogenized for 10 min. Subsequently, 0.1 mL of this mixture was spread over Baird–Parker agar plates (Becton Dickinson, France), ensuring an even distribution of the inoculum on the agar surface. The plates were held in place until the agar absorbed the inoculum and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Presumptive colonies indicative of S. aureus (typical black colonies surrounded by clear zones) were selected for the confirmatory tests. The identity of the putative S. aureus isolates was confirmed using coagulase, DNAse, and mannitol probes.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test

The antimicrobial profile of each S. aureus strain was determined using the disk diffusion protocol on Mueller–Hinton agar plates (DifcoTM) according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2012, 2018, 2019). Overnight cultures in trypticase-soy broth (TSB) (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.084, equivalent to a turbidity matching the 0.5 McFarland standard. Subsequently, sterile swabs impregnated with purified bacterial suspension were used to inoculate the Mueller–Hinton agar plates. After absorbing the inoculum, discs containing specific antibiotics were placed onto the plates to determine the susceptibility. After 24-h incubation at 37°C, clear halos were observed and processed using SCAN software (SCAN 1200, Interscience) to measure the size of the inhibition growth zones. Based on the halo size, the strains were categorized as sensitive (S), intermediate (I), or resistant (R) to the following antibiotics in accordance with the CLSI-M100-S21 criteria: penicillin (PE, 10 UI), oxacillin (OXA, 1 µg), chloramphenicol (C, 30 µg), erythromycin (E, 15 µg), gentamicin (GE, 10 µg), vancomycin (VA, 30 µg); sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SXT, 23.75 µg-1.25 µg), tetracycline (TE, 30 µg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 µg), rifampicin (RA, 5 µg), levofloxacin (LVX, 5 µg), and linezolid (LZD, 30 µg) [13]. The antibiotics were selected based on their common usage as veterinary drugs for bovine infections in the study region. Concurrently, a standard reference strain, S. aureus ATCC 25923, was used for quality control. All strains were tested in triplicate.

Genomic DNA extraction

Positive S. aureus isolates were cultivated overnight in TSB at 37°C. After incubation, bacterial cell suspensions were purified through centrifugation at 6,000 g for 10 min, and the resulting purified cell pellet was used for genomic DNA extraction. DNA extraction was performed using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue commercial kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA concentration was quantified using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop ND-2000c, Thermo Scientific, USA), and the DNA integrity was confirmed by electrophoresis in agarose gel.

A Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit was used to generate DNA libraries, and a MiSeq Reagent Kit was utilized to produce 2 × 150 bp paired-end read output with the MiSeq System (Illumina, Inc., USA). The DNA from three S. aureus strains was sequenced using the Illumina Miseq Platform at the Earlham Institute in Norwich, achieving an approximate 100× coverage.

Genomic sequencing and bioinformatics

The read quality was assessed using FastQC [14], and Trim Galore [15] was used to trim the reads, removing the first 20 bases and filtering when the average Phred score per base fell below 30. The paired option was specified during trimming. Clumpify was used to eliminate duplicate sequences from the reads using the dedupe option. The draft genomes, denoted with the prefix STA-LANIIA, were assembled de novo using the A5-miseq pipeline. The resulting draft genomes were reorientated with ABACAS using S. aureus NCTC 8325 (GCF_000013425.1) as the reference genome.

One hundred and twenty-four S. aureus genomes associated with mastitis were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Supplementary Table 1) as an international context and included in phylogenetic reconstruction and the detection of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes.

Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) was used for in silico typing to validate S. aureus taxonomy and determine sequence type (ST) and clonal complex groups. In addition, the PHYLOViZ Online tool was used to produce and visualize the spanning tree. ABRicate was used to identify the antibiotic resistance and virulence genes, considering the resistance database from Resfinder and the Virulence Finder Database (VFDB).

RESULTS

Mastitis-associated S. aureus isolates and antimicrobial profile

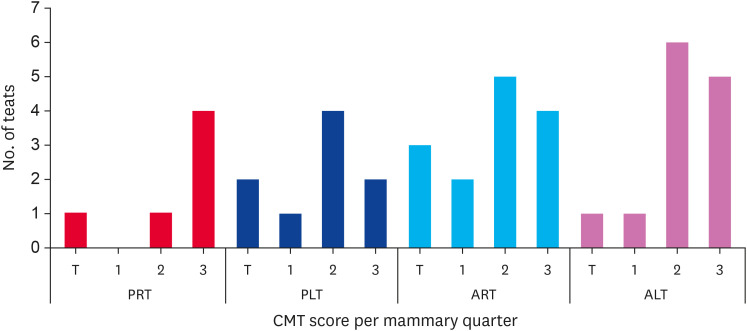

Of 50 productive cows subjected to a subclinical mastitis diagnosis, 21 (equivalent to 42 mammary quarters) tested positive, indicating an overall prevalence of 42% (Fig. 1). Most subclinical cases were identified in the preceding quarters (64.3%), with the left anterior quarter exhibiting a higher incidence within categories 2 and 3 of the California tests. The posterior quarters showed fewer cases, with the posterior right quarter displaying the lowest incidence of mastitis at 14.3%.

Fig. 1. Level of subclinical mastitis per mammary quarter. The bars indicate the number of mammary rooms diagnosed with subclinical mastitis according to the CMT for the different levels of the test (T, 1, 2, and 3). Quarter mammary: PRT, PLT, ART, and ALT.

PRT, posterior right teat; PLT, posterior left teat; ART, anterior right teat; ALT, anterior left teat; CMT, California Mastitis Test.

Twenty-four putative S. aureus isolates were obtained using preliminary bacterial identification protocols, including colony morphology, color, and size diameter. Subsequent confirmation through biochemical characteristics, coagulase, DNase, and mannitol-positive probes validated the identity of all strains as S. aureus.

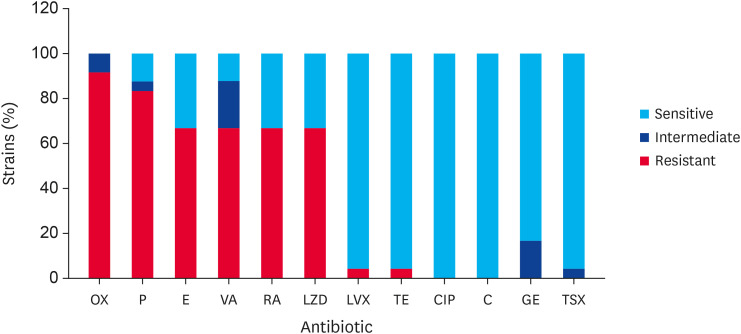

In vitro antimicrobial resistance of S. aureus

Among the 24 strains of S. aureus isolated from cow udders, a substantial proportion exhibited antimicrobial resistance. Specifically, 91.6% (22/24) displayed resistance to oxacillin, and 83.3% (20/24) exhibited resistance to penicillin. Furthermore, 66.6% (16/24) of the strains were resistant to erythromycin, vancomycin, rifampicin, and linezolid. In contrast, only 8.33% (2/24) and 4.16% (1/24) were resistant to levofloxacin and tetracycline, respectively. All strains (100%) were susceptible to chloramphenicol and ciprofloxacin (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Antimicrobial susceptibility of the S. aureus strains isolated from cows exhibiting mastitis. OX, P, E, VA, RA, LZD, LVX, TE, CIP, C, GE, TSX.

OX, oxacillin; P, penicillin; E, erythromycin; VA, vancomycin; RA, rifampin; LZD, linezolid; LVX, levofloxacin; TE, tetracycline; CIP, ciprofloxacin; C, chloramphenicol; GE, gentamicin; TSX, trimetropine-sulfamethoxazole.

ST prevalence and clonal complex associated with mastitis

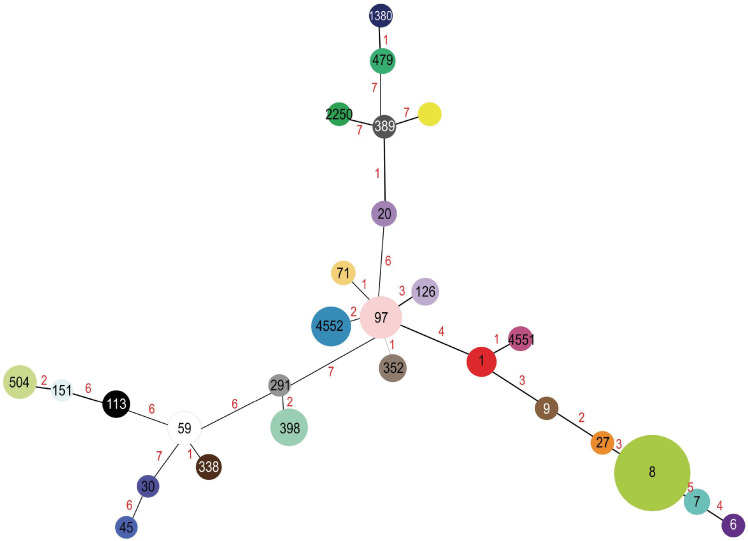

Analysis of the 127 S. aureus genomes revealed 26 different STs (Fig. 3). The most prevalent were ST8 and ST97, constituting 24.4% (31 genomes) and 8.6% (11 genomes), respectively. In addition, clonal complexes (CC) 1, 5, 8, 30, 45, and 97 were identified. CC97 emerged as the largest, encompassing five different STs (ST71, ST97, ST126, ST352, and ST4552), followed by CC1 associated with three STs (ST1, ST9, and ST4551).

Fig. 3. S. aureus associated with mastitis spanning tree. The colored circles represent different STs, and their sizes are proportional to the number of genomes included. The black numbers represent the STs, and the red numbers indicate the allelic difference among connected STs.

The clonal complexes detected in this study exhibited up to three allele differences among STs within specific CCs (highlighted by red numbers in Fig. 1). The Mexican S. aureus isolates were a part of CC97 and CC1, with ST4552 and ST4551, respectively. Furthermore, no clonal complex was identified for the Mexican genomes belonging to ST133.

Phylogenetic inference

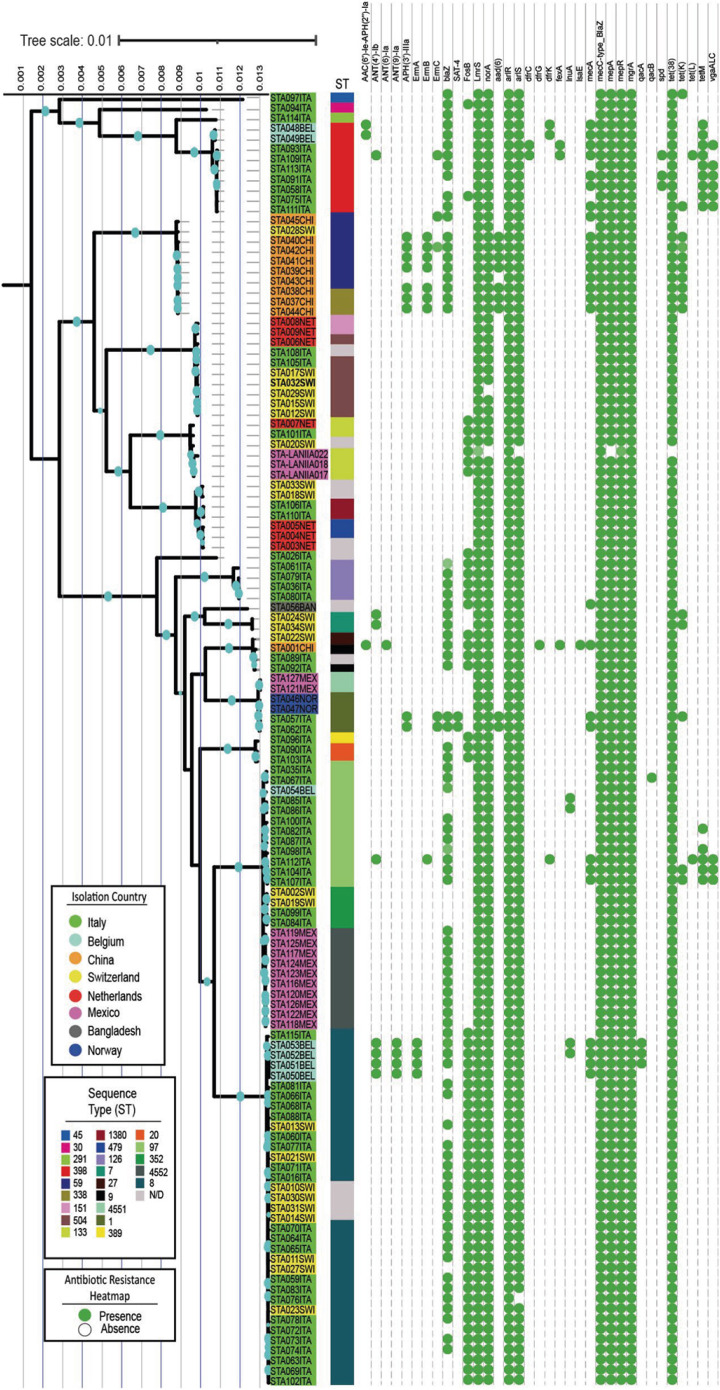

A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed to provide an international context for understanding the relationships and biological diversity of mastitis-causing S. aureus (Figs. 4 and 5). The genomes in the tree tended to align based on their predicted STs. On the other hand, a heterogeneous distribution was observed among the isolates from the eight countries of origin analyzed.

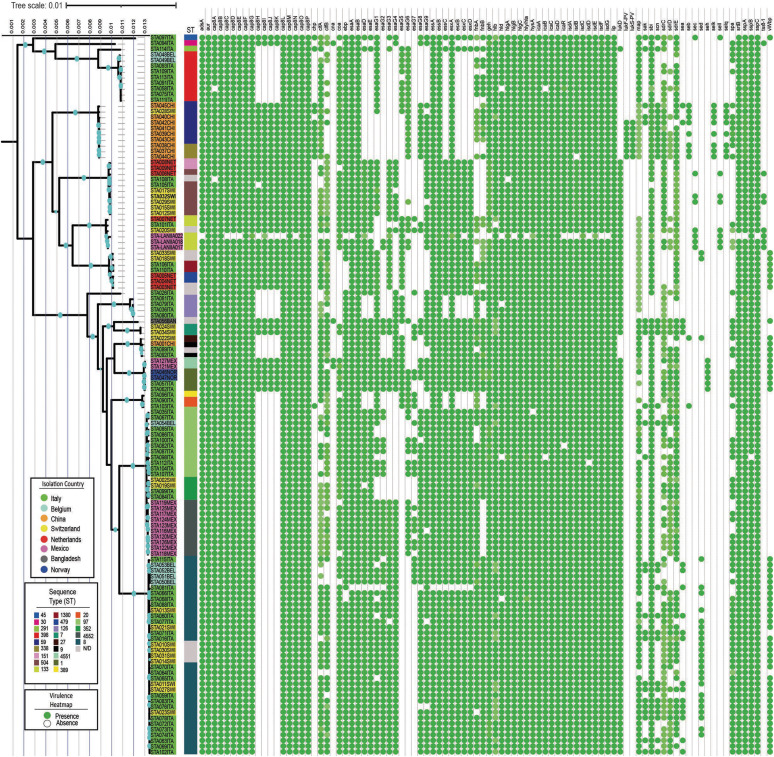

Fig. 4. S. aureus phylogenetic tree coupled to a presence/absence antibiotic resistance heatmap. Blued dots on branches represent a bootstrap higher than 85. Name shading indicate the isolation country, and the colorful column shows ST for each isolate. The green dots indicate the gene presence, while the absence of green dots indicates the opposite.

Fig. 5. S. aureus phylogenetic tree coupled to a presence/absence virulence heatmap. The blue dots on the branches represent a bootstrap higher than 85. Name shading indicate the isolation country, and the colorful column shows the ST for each isolate. The green dots indicate gene presence, while the absence of green dots indicates the opposite.

The genomes from Italy (highlighted in green in Fig. 4) were well-distributed among the three major clades in the phylogenetic tree. In contrast, the Mexican genomes (highlighted in pink in Fig. 4) were located primarily in clades 2 and 3, displaying a polyphyletic grouping. Furthermore, the Mexican isolates demonstrated a close phylogenetic relationship with the strains from Italy, Switzerland, and Norway.

Antibiotic resistance and virulence genes profile

An analysis of the antibiotic-resistance genes within the 127 examined genomes revealed a notable conserved block (Fig. 4). This conservative block encompassed genes, such as LmrS, norA, alrR, alrS, mecC, mepA, mgrA, and tet (38), associated with multidrug resistance to fluoroquinolones, phenicols, tetracycline, and cephalosporins. On the other hand, specific resistance markers were identified for certain ST groups, such as tetM for ST398 and FosB for ST133. Geographically specific genes were also observed, e.g., the genomes from Belgium in clade 2 with ST8 harbored ANT(4’)-lb, ANT(9)-la, and ErmA, while the Chinese genomes presented APH(3’)-llla, ErmB, and blaZ. In particular, the Mexican strains did not exhibit different genetic contents beyond the conservative block of resistance markers.

Similarly, the virulence gene profile of the S. aureus genomes revealed a well-conserved pattern (Fig. 5), encompassing the genes associated with immune system evasion (adsA), prevention of phagocytosis (operon capA-P), assembly of the type VII secretion system (T7SS), biofilm formation (icaA-D), iron uptake (isdA-G), hemolysin (hlgA-C), and V8 protease (sspA). Only the Mexican genomes carried the toxic shock syndrome toxin (tsst-1) associated with Staphylococcal pathogenicity island 1 (SaPI) and the enterotoxin gene sec, responsible for food poisoning. Members of ST8 possessed the vwbp gene associated with coagulase production for bacterial dissemination in thrombotic lesions. In addition, 66% of the isolates (84) associated with multiple ST groups (ST291, ST398, ST151, ST9, ST389, ST20, ST97, ST352, ST4552, and ST8) lacked the cap8H-K genes. Moreover, ST398, ST59, and ST388 lacked the esaD-E genes in their genomic repertoire.

DISCUSSION

In Mexico, approximately 2,300 antibiotics are authorized for veterinary use in cattle. Antibiotic selection depends on the bovine characteristics (weight, age, and number of services), veterinarian’s expertise, and antibiogram results in mastitis-affected cows [16].

The highest resistance identified in the present study was to penicillin (83.3%) and oxacillin (91.6%). Worldwide, studies consistently report this resistance phenotype as the most commonly observed in strains of bovine origin [17,18]. In Mexico, penicillin resistance ranged from 36.8% (State of Mexico) [19] to 100% (Guanajuato) [20]. In the context of Sinaloa dairy farms, there is no fundamental evidence regarding the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of the S. aureus strains isolated from bovine mastitis. Therefore, understanding the presence of resistance and virulence genes in these strains scattered across the region is essential.

Staphylococci bacteria, known for their antibiotic resistance, are increasingly reported worldwide, specifically in the livestock sector, posing significant economic challenges [21]. The emergence of these multi-drug-resistant S. aureus strains (MDRSA) is linked to selective pressure from antimicrobial misuse. Nevertheless, the main contributions to the spread of antibiotic resistance are mobile genetic elements facilitating the horizontal transfer of multidrug resistance genes, undermining the effectiveness of mastitis therapeutics control [21].

Considering the importance of S. aureus in food production and the widespread availability of high-throughput genome sequencing technologies, databases now contain numerous genomes of these bacteria from diverse sources. This abundance of genomic information contributes to a better understanding of the genomic comprehension of host-pathogen interactions, which are crucial for developing a new generation of antimicrobial drugs [22]. DNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis were also conducted to identify genetic elements associated with multidrug resistance owing to the lack of resources on the genomic insights of S. aureus isolates in Sinaloa state.

The Mexican S. aureus isolates identified in this study belong to the CC97 complex, one of the top and largest clonal complexes responsible for bovine mastitis globally [23]. CC97 is prevalent in other American countries, including Chile [24] and Brazil [25]. Both in vitro and in silico analyses of CC97 isolates have indicated a heightened virulence potential, contributing to asymptomatic and persistent infections, posing a significant challenge in treating sick animals [26]. Furthermore, this study supports the observation that CC97 is distributed widely in European countries, such as Italy, Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium. In contrast, CC1, identified as one of the two predominant clonal complexes in Mexico, has been associated with a lower incidence of bovine mastitis outbreaks [27].

Antibiotic resistance presents a growing challenge in global livestock farming, particularly in developing countries, such as Mexico, where indiscriminate antimicrobial drug use is widespread [28]. The One Health approach becomes imperative to adhere to in response to this emerging issue. This approach underscores the health and well-being of animals as a fundamental axis to ensure human health, reducing the probability of transmitting zoonotic diseases to the population.

Genomic analysis in the present study revealed the presence of genes conferring multi-resistance to drug classes, including fluoroquinolones, phenicols, tetracycline, and cephalosporins. Reports from Mexico indicate the extensive use of cephalosporin and penicillin as the primary treatment against bovine mastitis [29]. Nevertheless, genomic and phenotypic analyses revealed resistance to these antibiotics, consistent with observations in various parts of the world. Detected genes, such as tetM, tet(38), blaZ, and LmrS, have been associated with reduced effectiveness of antimicrobial mastitis treatments [30]. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus, associated with the gene mecA, was detected in isolates from China, Italy, and Belgium but not in Mexican strains. MRSA has been detected globally, causing skin and soft tissue infections [31]. This highlights the connection between increasing resistance phenotypes and the overuse of specific antibiotics, emphasizing the potential development of resistance through the excessive use of certain antimicrobials.

The capsular polysaccharides serotype 8 (CP8) associated with S. aureus was found in all strains analyzed in this study. This complex, comprised of 16 cap genes, plays a crucial role in protecting the pathogen against phagocytosis by neutrophils [32]. In contrast, capsular serotype 5 (CP5) was not detected in any of the isolates in the present study, supporting the idea that CP8 is the most prevalent serotype in clinical isolates [33]. In particular, staphylococcal enterotoxin C was identified, contributing to mammary gland inflammatory reactions in bovines [34] and toxic shock syndrome affecting humans. These genes and their subsequent protein translation pose a significant risk to public health owing to their resistance to heat treatment, a standard method for pathogen reduction control in dairy-based products [35].

The analysis identified the crucial virulence markers essential for the pathogenesis process and infection in all isolates. For example, the mastitis biofilm cassette icaABCD, known for its pivotal role in the adhesion of S. aureus to the bovine mammary epithelium, was present in all isolates [36]. In addition, the iron-regulated surface determinant (isdA-G) genes, which are vital for iron acquisition by capturing heme from hemoglobin [37], were found in all genomes. Hemoglobin is the preferred source of iron for the bacterium during infections [38]. The serine protease Ssp (v8 protease) was vital in cleaving and degrading host proteins, promoting S. aureus virulence [39]. Moreover, genes encoding the T7SS were detected, highlighting its crucial role in S. aureus virulence, survival, and long-term persistence through protein translocation [40].

The study noted a high prevalence of S. aureus strains associated with bovine mastitis in a milk production farm in Sinaloa. These isolated strains exhibited phenotypic and genomic multidrug resistance, compromising the effectiveness of commonly used antibiotics. Furthermore, all isolates revealed a diverse repertoire of virulence genes implicated in the bovine mastitis pathogenic process. In particular, the presence of toxic shock syndrome and enterotoxin C in the isolates from this study poses a significant risk to human health and the integrity of milk and dairy products. The authors recommend ongoing evaluations of antibiotic effectiveness and the implementation of pathogen reduction plans to minimize the risks associated with microbiological contamination, reducing the incidence of epidemiological outbreaks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank MC Arlet Guadalupe Cruz Calderon and MVZ Jesus Joel Freer Uriarte for their technical support.

The authors thank Coordinación General para el Fomento a la Investigación Científica e Innovación del Estado de Sinaloa (CONFIE) for financially supporting this research publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

- Conceptualization: Aguirre-Sánchez JR, Castro-Del Campo N, Castro-Del Campo N.

- Data curation: Medrano-Félix JA.

- Formal analysis: Aguirre-Sánchez JR.

- Funding acquisition: Castro-Del Campo N, Castro-Del Campo N.

- Methodology: Castro-Del Campo N, Medrano-Félix JA, Castro-Del Campo N.

- Project administration: Castro-Del Campo N.

- Resources: Castro-Del Campo N, Chaidez C.

- Writing - original draft: Aguirre-Sánchez JR.

- Writing - review & editing: Castro-Del Campo N, Chaidez C, Medrano-Félix JA, Castro-Del Campo N.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Additional S. aureus genomes used for this study

References

- 1.FAO. Portal lácteo [Internet] Rome: FAO; 2023. [Updated 2024]. [Accessed 2023 Nov 14]. https://www.fao.org/dairy-production-products/socio-economics/dairy-development/es/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.INEGI. Cuéntame de México [Internet] Aguascalientes: INEGI; 2019. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed 2023 Nov 14]. https://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/economia/primarias/gana/default.aspx?tema=e/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallegos-Daniel C, Taddei-Bringas C, González-Córdova AF. Panorama de la industria láctea en México. Estud Soc Rev Aliment Contemp y Desarro Reg. 2023;33(61) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarazona-Manrique LE, Villate-Hernández JR, Andrade-Becerra RJ. Bacterial and fungal infectious etiology causing mastitis in dairy cows in the highlands of Boyacá (Colombia) Rev Fac Med Vet Zootec. 2019;66(3):208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goulart DB, Mellata M. Escherichia coli mastitis in dairy cattle: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment challenges. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:928346. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.928346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan MZ, Khan A. Basic facts of mastitis in dairy animals: a review. Pak Vet J. 2006;26(4):204. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krebs I, Zhang Y, Wente N, Leimbach S, Krömker V. Bacteremia in severe mastitis of dairy cows. Microorganisms. 2023;11(7):1639. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11071639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cobirka M, Tancin V, Slama P. Epidemiology and classification of mastitis. Animals (Basel) 2020;10(12):2212. doi: 10.3390/ani10122212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedersen RR, Krömker V, Bjarnsholt T, Dahl-Pedersen K, Buhl R, Jørgensen E. Biofilm research in bovine mastitis. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:656810. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.656810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freitas CH, Mendes JF, Villarreal PV, Santos PR, Gonçalves CL, Gonzales HL, et al. Identification and antimicrobial suceptibility profile of bacteria causing bovine mastitis from dairy farms in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul. Braz J Biol. 2018;78(4):661–666. doi: 10.1590/1519-6984.170727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manjarrez López AM, Díaz Zarco S, Salazar García F, Valladares Carranza B, Gutiérrez Castillo A del C, Barbabosa Plliego A, et al. Staphylococcus aureus biotypes in cows presenting subclinical mastitis from family dairy herds in the Central-Eastern State of Mexico. Rev Mex De Cienc Pecu. 2012;3(2) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanderhaeghen W, Hermans K, Haesebrouck F, Butaye P. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in food production animals. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(5):606–625. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809991567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twentieth Informational Supplement. CLSI Doc M100-S20. Wayne: Clin Lab Stand Institute; 2010. p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data [Internet] [Updated 2010]. [Accessed 2023 Dec 8]. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc .

- 15.Krueger F. San Francisco: Altos Labs; 2015. Trim Galore. A Wrapper Tool Around Cutadapt FastQC to Consistently Apply Qual Adapt Trimming to FastQ Files; p. 517. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng WN, Han SG. Bovine mastitis: risk factors, therapeutic strategies, and alternative treatments: a review. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2020;33(11):1699–1713. doi: 10.5713/ajas.20.0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Oliveira AP, Watts JL, Salmon SA, Aarestrup FM. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis in Europe and the United States. J Dairy Sci. 2000;83(4):855–862. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar R, Yadav BR, Singh RS. Antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity factors in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from mastitic Sahiwal cattle. J Biosci. 2011;36(1):175–188. doi: 10.1007/s12038-011-9004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salgado-Ruiz TB, Rodríguez A, Gutiérrez D, Martínez B, García P, Espinoza-Ortega A, et al. Molecular characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus from small-scale dairy systems in the highlands of Central México. Dairy Sci Technol. 2015;95(2):181–196. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varela-Ortiz DF, Barboza-Corona JE, González-Marrero J, León-Galván MF, Valencia-Posadas M, Lechuga-Arana AA, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from subclinical bovine mastitis cases and in vitro efficacy of bacteriophage. Vet Res Commun. 2018;42(3):243–250. doi: 10.1007/s11259-018-9730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castellano González MJ, Perozo-Mena AJ. Mecanismos de resistencia a antibióticos β-lactámicos en Staphylococcus aureus . Kasmera. 2010;38(1):18–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dan M, Yehui W, Qingling M, Jun Q, Xingxing Z, Shuai M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance, virulence gene profile and molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from dairy cows in Xinjiang Province, northwest China. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;16:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dabul AN, Camargo IL. Clonal complexes of Staphylococcus aureus: all mixed and together. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2014;351(1):7–8. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith EM, Green LE, Medley GF, Bird HE, Fox LK, Schukken YH, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of intercontinental bovine Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(9):4737–4743. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4737-4743.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aires-de-Sousa M, Parente CE, Vieira-da-Motta O, Bonna IC, Silva DA, de Lencastre H. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from buffalo, bovine, ovine, and caprine milk samples collected in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(12):3845–3849. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00019-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guinane CM, Sturdevant DE, Herron-Olson L, Otto M, Smyth DS, Villaruz AE, et al. Pathogenomic analysis of the common bovine Staphylococcus aureus clone (ET3): emergence of a virulent subtype with potential risk to public health. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(2):205–213. doi: 10.1086/524689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoekstra J, Zomer AL, Rutten VP, Benedictus L, Stegeman A, Spaninks MP, et al. Genomic analysis of European bovine Staphylococcus aureus from clinical versus subclinical mastitis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):18172. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75179-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosain MZ, Kabir SM, Kamal MM. Antimicrobial uses for livestock production in developing countries. Vet World. 2021;14(1):210–221. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2021.210-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maradiaga M, Echeverry A, Miller MF, den Bakker HC, Nightingale K, Cook PW, et al. Characterization of antimicrobial resistant (AMR) Salmonella enterica isolates associated with cattle at harvest in Mexico. Meat Muscle Biol. 2019;3(1):63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molineri AI, Camussone C, Zbrun MV, Suárez Archilla G, Cristiani M, Neder V, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Vet Med. 2021;188:105261. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2021.105261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee AS, de Lencastre H, Garau J, Kluytmans J, Malhotra-Kumar S, Peschel A, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):18033. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohamed N, Timofeyeva Y, Jamrozy D, Rojas E, Hao L, Silmon de Monerri NC, et al. Molecular epidemiology and expression of capsular polysaccharides in Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates in the United States. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0208356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luong TT, Lee CY. Overproduction of type 8 capsular polysaccharide augments Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Infect Immun. 2002;70(7):3389–3395. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3389-3395.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang R, Cui J, Cui T, Guo H, Ono HK, Park CH, et al. Staphylococcal enterotoxin C is an important virulence factor for mastitis. Toxins (Basel) 2019;11(3):141. doi: 10.3390/toxins11030141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.G Abril A, G Villa T, Barros-Velázquez J, Cañas B, Sánchez-Pérez A, Calo-Mata P, et al. Staphylococcus aureus exotoxins and their detection in the dairy industry and mastitis. Toxins (Basel) 2020;12(9):537. doi: 10.3390/toxins12090537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ginestre M, Ávila Y, Valero K, Rivera J, Briñez W, Valeris R. Producción de biofilm y presencia de genes icaABCD en cepas de Staphylococcus aureus aisladas de leche cruda. Kasmera. 2017;45(2):79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurd AF, Garcia-Lara J, Rauter Y, Cartron M, Mohamed R, Foster SJ. The iron-regulated surface proteins IsdA, IsdB, and IsdH are not required for heme iron utilization in Staphylococcus aureus . FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;329(1):93–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammer ND, Skaar EP. Molecular mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus iron acquisition. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65(1):129–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gustafsson E, Oscarsson J. Maximal transcription of aur (aureolysin) and sspA (serine protease) in Staphylococcus aureus requires staphylococcal accessory regulator R (sarR) activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;284(2):158–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao Z, Casabona MG, Kneuper H, Chalmers JD, Palmer T. The type VII secretion system of Staphylococcus aureus secretes a nuclease toxin that targets competitor bacteria. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2(1):16183. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional S. aureus genomes used for this study