Abstract

For agricultural safety and sustainability, instead of synthetic fertilizers the eco-friendly and inexpensive biological applications include members of plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) genera, Pseudomonas spp. will be an excellent alternative option to bioinoculants as they do not threaten the soil biota. The effect of phosphate solubilizing bacteria (PSB) Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MK 764942.1) on groundnuts’ growth and yield parameters was studied under field conditions. The strain was combined with a single super phosphate and tested in different combinations for yield improvement. Integration of bacterial strain with P fertilizer gave significantly higher pod yield ranging from 7.36 to 13.18% compared to plots where sole inorganic fertilizers were applied. Similarly, the combined application of PSB and inorganic P fertilizer significantly influenced plant height and number of branches compared to sole. However, a higher influence of phosphorous application (both PSB and P fertilizer) observed both nodule dry weight and number of nodules. Combined with single super phosphate (100% P) topped in providing better yield attributing characters (pod yield, haulm yield, biomass yield, 1000 kernel weight, and shelling percentage) in groundnut. Higher oil content was also recorded with plants treated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa combined with single super phosphate (SSP) (100% P). Nutrients like nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P), and potassium (K) concentrations were positively influenced in shoot and kernel by combined application. In contrast, Ca, Mg, and S were found to be least influenced by variations of Phosphorous. Plants treated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and lower doses of SSP (75% P) recorded higher shoot and kernel P. We found that co-inoculation with PSB and SSP could be an auspicious substitute for utilizing P fertilizer in enhancing yield and protecting nutrient concentrations in groundnut cultivation. Therefore, PSB can be a good substitute for bio-fertilizers to promote agricultural sustainability.

Keywords: Groundnut, PSB, Yield, Synthetic fertilizer, Nutrient, Stress resistance

Introduction

The current global food demand and the increasing prevalence of biotic and abiotic environmental stress pose a significant challenge to world agricultural production. In this context, the production of additional food crops for sustainable food security in the future is crucial. Arachis hypogaea L., commonly known as groundnut, is a globally significant leguminous crop that is cultivated annually for food and oil purposes. It is a vital source of income for farmers across the world. Recent surveys indicate that groundnuts are among the top-ranked crops, with over 100 countries cultivating this oilseed in tropical and subtropical regions. (Desmae et al. 2019; Ojiewo et al. 2020; Puppala et al. 2023; Huang et al. 2023). These crops are also known as peanut, monkey-nut, earthnut, and goobers. The wide range of environmental stress (abiotic and biotic) is highly encountered in groundnut agriculture for yield reduction (Belayneh and Chondie 2022). Therefore, to avail enough food sources farmers now hugely utilize synthetic fertilizers and pesticides to protect the plants and for more food production (Puppala et al. 2023). Synthetic fertilizers have been shown to harm the environment, soil quality, plant growth, and human health. To counter these harmful effects, plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) have been introduced as a biofertilizer to promote agriculture and ensure food security (Daniel et al. 2022). In this study, we have focused on using PGPR genera (Pseudomonas) to boost groundnut production. These bacteria are naturally found in the rhizosphere and within the plant’s body, making them an ideal biofertilizer. The top groundnut-producing countries, including India, China, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan, Burma, and the United States of America, can benefit from this approach. Groundnuts are an excellent source of dietary minerals, fiber, vitamins, and bioactive compounds, with seeds containing 35–60% oil and 22–30% protein. Therefore, they can provide essential nutrients for household nutrition (Desmae et al. 2019).

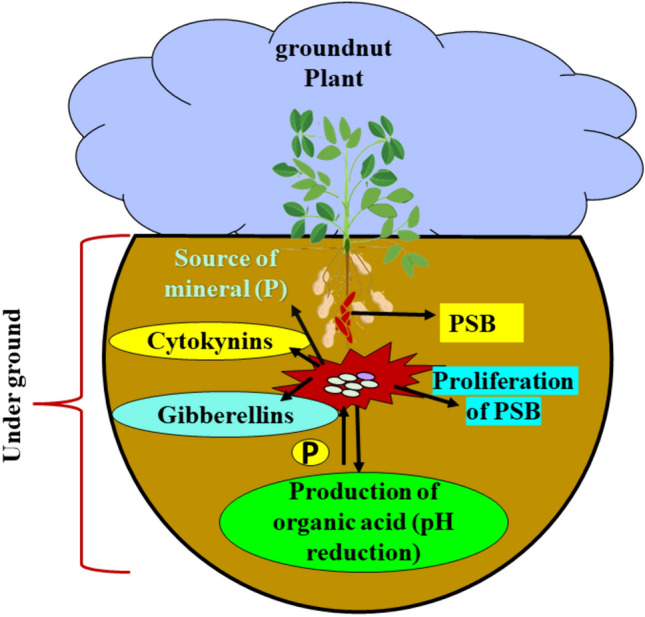

In recent years, various studies have been reported on PSB (Phosphorus solubilizing bacteria) characteristics and mechanisms of phosphorus solubilization processes. PSB are beneficial bacteria that make inorganic phosphorus available to plants. Rhizosphere microorganisms’ P-solubilization ability is crucial for plant phosphate nutrition. Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Rhizobium strains efficiently solubilize phosphate through organic acid production (Janati et al. 2023). Acid phosphatases play a vital role in organic phosphorus mineralization in soil. This observation suggests that PSB inoculation can positively impact plant growth by improving root development, enhancing mineral uptake, and promoting a healthier water relationship in plants (Long and Wasaki 2023). Moreover, PSB has been found to produce growth-promoting substances that can potentially boost crop growth. This highlights the potential benefits of PSB inoculation to improve plant health and productivity. In 2023, Long and Wasaki reported that PSB is an effective inorganic source of phosphates for plant uptake with low-cost farming value. The solubilization process of PSB is encountered as one of the most important traits associated with plant nutrition. According to recent reports, PSB can increase the phosphate in soil without disturbing the biochemical composition (Timofeeva et al. 2022). The presence of microorganisms in soil can decompose the organic matter and transform it into plant nutrition for sufficient crop yields. Phosphorus (P) is one of the essential macronutrients that helps in plant growth, and it is mainly present in unavailable forms in agricultural soil (Djuuna et al. 2022). The process of solubilizing PSB in soil is a highly effective method for producing free orthophosphate that plays a crucial role in the soil phosphorus cycle for promoting plant growth and yield (Li et al. 2023). The microflora containing PSBs like Escherichia species, Bacillus species, Pseudomonas species, and Rhizobium species are widely available in soil phosphate (Fig. 1) (Pradhan et al. 2017; Tian et al. 2021). Among them, Pseudomonas stands out as the most important and favored bioinoculant for promoting plant growth and controlling phytopathogenic and disease management of plants (Sah et al. 2021). Pseudomonas spp. not only solubilize phosphorus and potassium but also fix atmospheric nitrogen and help generate phytohormones, volatile organic compounds, lytic enzymes, secondary metabolites, and antibiotics during plant stress conditions (Mehmood et al. 2023). Previous research by Pradhan et al. has established a strong correlation between bacteria and soluble phosphates as a source of carbon for plant roots (Pradhan et al. 2017). Furthermore, PSB has been used as a biofertilizer to produce several crops such as cotton, maize, sunflower, rice, and faba, as Fahde et al. (2023) highlighted.

Fig. 1.

PSB growth and their role in soil: Ability of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (PSB) to enhance the plant growth of groundnut. The inoculation of PSB in plant roots releases phosphorus (P) and minerals, which help to improve plant growth and produce more yield

Groundnuts have great economic and social importance worldwide, but the rapid alteration of environmental stresses decreases their productivity. Farmers now randomly use large amounts of fertilizers and pesticides for better groundnut yields. Groundnut is a legume species and it is associated with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. In the microbial cellular process, nitrogen fixation is possessed by nitrogenase and this enzyme converts the atmospheric nitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3) (Frezarin et al. 2023). Groundnut is a source of protein, essential fatty acids, and other biologically active compounds. It is also rich in minerals (K, Na, Ca, Mn, Fe, and Zn) and biologically active compounds (arginine, resveratrol, phytosterols, and flavonoids) (Prodic et al. 2023). Previous research reported that Azotobacter, Azospirillum, Phosphobacteria, and Rhizobium are used as biofertilizers to improve groundnut yielding. (Mathivanan and Jayaraman 2019). Peanut seedlings are extremely vulnerable to soil-borne fungal pathogens, particularly Aspergillus niger and Sclerotium rolfsii. However, our study presents an effective solution for healthy groundnut cultivation by utilizing phosphate-solubilizing bacteria as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR).

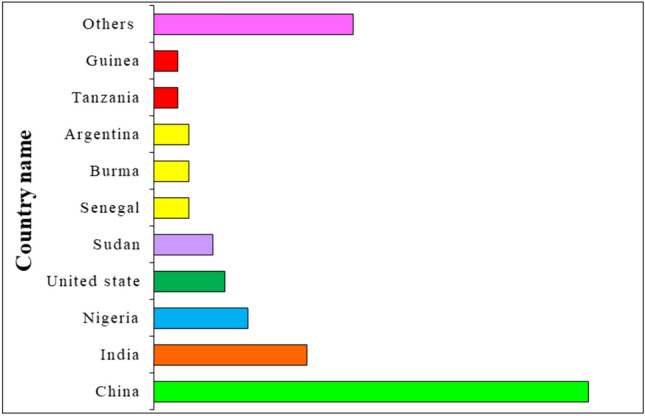

Potassium (K) is an incredibly vital and abundant macro element that plays a crucial role in plant nutrition. Deficiency or excess concentration of this nutrient can lead to various diseases in plants, as reported by Kumar et al. (2020). International research has shown that foliar application of boron during flowering and pod formation stages can improve groundnut quality and production, as Kondapalli et al. (2015) noted. Previous studies by Chaudhary et al. (2019) also reported that potassium application in groundnut cultivation can improve the growth and quality of the crop. Groundnut production is massive, with annual cultivation of approximately 46 million tons globally, as reported by http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home. China and India are the largest producers of groundnuts, accounting for 50% of global production (Fig. 2). In 2022, China cultivated approximately 18.33 million metric tons, while India produced 83.69 lakh tons, as noted by Huang et al. (2023). In India, groundnut cultivation mainly depends on rainfall, with 70% of the area and 75% of the production coming from states like Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Odisha, according to Oteng-Frimpong et al. (2021). Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh are the biggest contributors to groundnut cultivation and productivity, as reported by Das et al. (2023). Groundnut is grown in kharif, rabi, and rabi-summer seasons over 2.43 lakh hectares, producing 3.98 lakh tones of groundnut in 1639 kg ha−1, according to Misra et al. (2022). Groundnut is rich in fat, protein, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals and is generally grown under acid soils. India has a total of 30 percent of acid soil land, as reported by Ojiewo et al. (2020) and Sadeghi et al. (2023).

Fig. 2.

Total production of groundnut in different countries in percentage. More than 100 countries are growing groundnut, and India is placed in second position after China in groundnut production

Acidic soil is prevalent in numerous regions across the globe, including several states in India, China, the United States, West Africa, Sudan, and Nigeria. It is imperative to acknowledge the high acidity levels in the soil, as it can significantly impact the flora, fauna, and agricultural production in these areas. It is crucial for stakeholders in these regions to be cognizant of this fact and take necessary actions to mitigate the adverse effects of acidic soil, such as soil amendment and crop rotation and by default, groundnut cultivation acquires highly weathered acidic land patterns. The physical and morphology of acid lateritic soils (Alfisol) are advantageous for groundnut farming but the chemical characteristics (low uptake of micro and macronutrients) are the main barrier to groundnut production due to fixation. (Andrews et al. 2021). The soil acidity decreases the availability of plant nutrients, by depending on the H+ and Al3+ ions activities in the soil solution. According to Goyal and Habtewold (2023), soil acidity has harmful effects on symbiotic rhizobia and legumes resulting in poor nodulation and nitrogen fixation. The detrimental effect of symbiotic N2 fixation in legumes can be attributed to the poor and very limited supply of P, Ca, and Mo (Johan et al. 2021). ‘P’ is the primary requirement for seed formation and extensively deposited in plants’ parts like seeds (Tariq et al. 2022). It develops disease resistance activity in plants and tolerance towards abiotic stress. Moreover, the fruits, vegetables, and grains quality and biological N2 fixation is highly dependent on P and it is vital for nodule formation (Aasfar et al. 2021). P limitation affects the growth and yield of crops severely. In the present context, we have targeted to boost groundnut yield while maintaining the soil’s quality and fertility. Here, we have reported the effect of inoculation of PSB with SSP for better plant growth and yield potential, which contributes to environmental sustainability towards smart agriculture.

Materials and methods

Field experimentation

A Field experiment was conducted repeatedly for two rabi seasons (2021–22 and 2022–23) with groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L. cv. Debi), in the field of Centurion University of Technology and Management, Bhubaneswar. The experimental field had high temperatures in summer, low temperatures during the winter, and a medium rainy season. All the experimental data were collected for two consecutive years.

Analysis of P fractionation in soil

In this experiment, we analyzed the P fraction of soil by using Hedley’s sequential P fractionation method. This method is widely used to determine soil P fractionation (Liu et al. 2022). 0.5 g soil was initially extracted and kept in a 50-mL centrifuge tube. Extraction was done by taking approximately 5 cm2 of anion-exchange sap (Selemion TM ion exchangeable sap) and 30 mL distilled water. secondly, 30 mL 0.5 M NaHCO3, then 30 mL 0.1 M NaOH, and the last was 20 mL 1 M HCl in sequence. Each solution was mixed at 120 rpm at 25 °C for 16 h. The sap was settled inside the tube and for the separation of the supernatant and soil, the soil suspension was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 20 min. For the P extraction, the sap was transferred into 20 mL 0.5 M HCl containing tube and mixed at 120 rpm at 25 °C for 2 h. To get total P, 5 ml of the Sodium hydrogen carbonate (NaHCO3) extract was mixed with 10 mL 0.9 M H2SO4 and 0.5 g (NH4)2S2O8 was autoclaved at 120 °C for 60 min. To determine the P concentrations of all extracts and the digested solution, we utilized the molybdenum blue method, a reliable and widely accepted technique. (Murphy and Riley 1962).

Application of fertilizers

The treatments were uniformly administered with chemical fertilizers: urea for N (20 kg ha−1) and Muriate of Potash (MOP) for K2O (40 kg ha−1). In addition, P2O5 was applied at a rate of 40 kg ha−1 as single superphosphate (SSP) according to the treatment schedule.

Bio-inoculation of PSB (Phosphate solubilizing bacteria)

Phosphate solubilizing bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MK 764942.1) are bioinoculants applied for seed inoculation and used as carrier-based biofertilizers in soil. PSB (phosphate solubilizing bacteria) containing soil samples were collected from the experimental fields of Centurion University of Management and Technology, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India and then brought to the laboratory in sterile polythene bags. Then, tentative PSB were isolated using the method of Glick et al. (1995). Colonies of different morphologies were picked up and purified. A total of 195 rhizobacterial isolates were obtained. Among them PSB were identified after morphological, biochemical and 16 s rRNA sequencing. Then, the above accession number was obtained after being submitted to NCBI. The identified strain was sub-cultured and stored in deep freeze (− 20 °C) for future use.

Formulation of biofertilizer

Nutrient broth containing two strains grown at 28 °C and 120 rpm for 72 h. The culture was grown to achieve optical densities of 0.9 (108–109 CFU ml−1) at 620 nm wavelength. Then the biofertilizers are formulated by mixing sterilized lignite, CaCO3, and gum acacia with broth. The biofertilizer with solid carrier-based (1 kg) contains lignite—640 g, CaCO3—160 g, gum acacia A nutrient broth comprising two different strains was cultured at 28 °C and 120 rpm for 72 h. The culture was allowed to progress to an optical density of 0.9 (108–109 CFU ml−1) at a wavelength of 620 nm. The resultant biofertilizers were formulated by blending sterilized lignite, CaCO3, and gum acacia with the broth—20 g, and cultured broth—200 ml. During the sowing period, biofertilizers were applied according to the requirements of treatments.

Seed inoculation

Two strains were initially chosen and grown in nutrient broth at 28 °C and 120 rpm for 72 h. The culture’s optical densities were 0.9 (108–109 CFU ml−1) at a wavelength of 620 nm. The broths were then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm, and the settled pellets were washed three times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). After that, they were dissolved in the phosphate buffer, and the cell count was 3.0 × 108 CFU ml−1. According to Bechtaoui et al. (2021), Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L. cv. Tag 24) seeds were surface sterilized with 1% NaOCl for 6 min. After that, they were washed with sterile distilled water six times for 15–20 min each time. The sterilized seeds were then soaked in a phosphate buffer solution for 2 h. Finally, the coated seeds were sown in the field as per the treatment schedule.

Harvesting of groundnut

The plant growth was maintained for 110 days till maturity and then harvested from the field. From each plot, ten (10) groundnut plants were taken at 45 DAS to measure the dry weight and nodule number (Bi and Zhou 2021). During the harvesting period, differently treated groundnut plants were collected by moistening the rhizosphere and taken out with the help of a spade. The whole root and adhered soil were loosened in a bucket of water to protect the roots, then washed thoroughly and dried out.

Different plant parts, like stems and legumes, were taken separately, labeled, and air-dried in a hot air oven. Then the constant weight of the dried samples was taken and recorded. Each sample was ground separately and used for different analyses.

Detail data of experiments and treatment of groundnut

We have conducted the field trial with the groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) variety Debi. The experiment had treated with six (6) treatments (T1—Control, T2– Pseudomonas aeruginosa, T3—100% P as SSP, T4—75% P as SSP, T5—75% P as SSP + Pseudomonas aeruginosa, T6—100% P as SSP + Pseudomonas aeruginosa and three (3) replications. Plots were designed according to Randomized block design (RBD). The net plot area was 5 m × 2.2 m.

The Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains were compared individually and in combination with 100% P as SSP. The initial properties of the soil of the experimental site were strongly acidic in reaction (pH- 4.18). The organic carbon content of the soil was 0.38 percent. Inorganic P fractions, which include Ca–P and non-occluded Al–P and Fe–P, were 40.25 and 400.69 mg kg−1 respectively.

Analysis of plant samples

The processed plant sample contained nitrogen, which was determined using the Kjeldahl digestion method, as described by Wright and Wilkinson (1993). The phosphorous concentration was measured using the vanadomalayaites method at 470 nm. The potassium concentration was measured using a flame photometer. The sulfur concentration of the plant sample was analysed using a spectrophotometer at 410 nm (Jackson 1975). The EDTA titration method measured Ca and Mg concentrations (Page et al. 1982).

The oil content of the kernel

Oil content was estimated by following the Solvent extraction method using the Soxhlet apparatus as described in the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Chosen by random selection, Kernels were washed with distilled water, oven-dried at 60 °C to constant weight, and crushed with a mortar–pestle. Five (5) grams of such crushed material were used for analyse oil percentage.

Plants height and number of branches

To accurately determine the growth of the plants, we selected 10 plants from each plot and carefully measured their height and the number of branches. The height of each plant was measured with precision in centimetres (cm) from the ground level to the tip of the leaf. The average height of the 10 plants was then taken as the height of the plant for each treatment. This process allowed us to collect reliable data that will help us make informed decisions about the growth of these plants.

Total pods number of plant

To determine the average number of pods per plant, a total count of pods from ten sample plants was taken and then divided by the number of plants. This method provides an efficient and accurate way to evaluate the pod yield of a crop.

Pod yield per plant

Each treated plot of harvested pods was dried and then shaded for 72 h. After this process, dry weight was taken in a weighing balance (ton ha−1).

Biological yield

After maturity of 110 days, the groundnut crop was harvested and plants were allowed to be sundried for 2–3 days. An electronic balance measured both weights of the stalk with pods and the biomass was calculated by taking weight (ton ha−1).

Haulm yield

After groundnut harvesting, the pods were separated from the sundried plants. Then, plants were sundried for a further 2–3 days, and after the drying process, stalk weight was taken as ton ha−1 through the balance machine.

Plants kernel weight (1000)

The mass of one hundred kernels was determined using an electronic balance. Subsequently, this value was multiplied by ten to obtain the thousand kernel weight, and the resulting value was expressed in grams. The shelling percentage may be obtained by dividing the kernel weight by the total weight of pods and subsequently multiplying by one hundred. (Shelling (%) = Kernel weight/Total weight of pods * 100).

Statistical analysis

The data collected in this study was obtained from at least three independent experiments. The mean values are provided, along with standard errors, to help identify any differences in the mean among the treatments. To analyze the data, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS (12.0 Inc., USA), which allowed for the determination of the least significant difference (LSD) for the significant data. Finally, the means were interpreted by Duncan’s multiple range tests (DMRT) to help identify any key differences among the treatments.

Result

The field experiment data with groundnut cv. Debi was conducted in rabi seasons of two consecutive years, i.e., 2021–22 and 2022–23, in the agronomy field at Centurion University Technology and Management, Bhubaneswar, in randomized block design. The PSB strain was compared in sole and in integration with graded doses (75 and 100%) of inorganic P fertilizer, i.e., Single Super Phosphate, about growth promotion in groundnut. Seed bacterization and inorganic P fertilizer significantly increased plant height and number of branches in groundnut. The data were collected to evaluate the efficiency of the two selected PSB strains in improving soil P status and crop P uptake in field conditions. The strain Pseudomonas aeruginosa was compared sole and combined with graded doses of P. The soil was strongly acidic in the reaction (pH 4.18) and before the experiment, the soil’s P values (T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6) were 2.32, 1.84, 3.38, 4.19, 3.86, and 2.41 mg/kg−1, respectively. After the experiment, the P values of the soils of different treatments were evaluated. The P values of T1 were 1.93, T2 was 30.25, T3 was 28.16, T4 was 45.56, T5 was 36.05, and T6 was 52.45 mg/kg−1, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Soil P fractions (mg/kg–1 soil) of before and after the experiment

| Treatments | P value of soil (before experiment) (mg/kg–1) | P value of soil (after experiment) (mg/kg–1) |

|---|---|---|

| T1 (Control) | 2.32 ± 0.003d | 1.93 ± 0.012a |

| T2 (P. aeruginosa) | 1.84 ± 0.006a | 30.25 ± 0.002b |

| T3 (100% P as SSP) | 3.38 ± 0.002b | 28.16 ± 0.005a |

| T4 (75% P as SSP) | 4.19 ± 0.015a | 45.56 ± 0.001c |

| T5 (75% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 3.86 ± 0.005c | 36.05 ± 0.015c |

| T6 (100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 2.41 ± 0.002a | 52.45 ± 0.001b |

Each value represents the mean of three replicates standard error (SE). Means were compared using ANOVA

Data followed by the same letters in a row are not significantly different at the level of P > 0.05

a, b, c, d Significant differences at the level of P > 0.05, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT)

Role of PSB inoculation on yield and attributes of groundnut

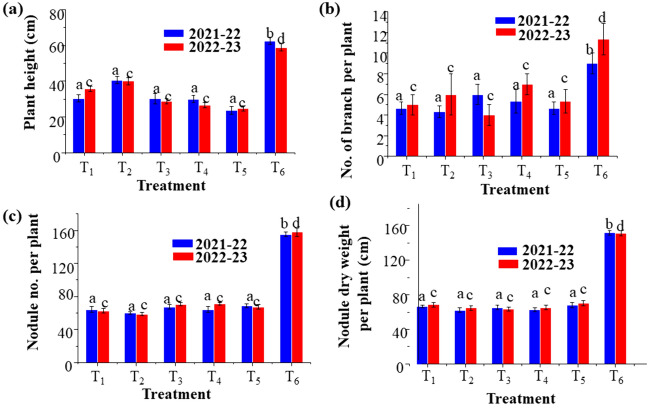

Plant height and number of branches

In season 1(2021–22) and season 2 (2022–23) plant height and number of branches were averaged over 10 plants in each replication. In Fig. 3a, T6 (treatment 6) shows the highest plant height, 62 cm for season 1 and 59 cm for season 2. The number of branches observed as 9 and 11 cm were maximum in treatment T6—100% P as SSP + Pseudomonas aeruginosa for seasons 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 3b). Crops grown in control plots recorded the lowest height at 23.6 and 25 cm in T5 and the lowest number of branches in T2 and T3 (4.3 and 4 cm) for both seasons. Combined inoculation of P fertilizer (SSP) with strain significantly increased plant height and number of branches per plant. However, no significant variation was found among the treatments where either PSB or P fertilizer (SSP) was applied in the sole application of biofertilizers.

Fig. 3.

Effect of application of PSB strains on the plant: PSB strains on (a) height (b) per plant in groundnut (c) Effect of application of PSB strains (nodule number per plant) and (d) nodule dry weight in groundnut) for the year 2021–22 and 2022–23. (T1—Control, T2—PSB: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, T3—100% P as SSP, T4—75% P as SSP, T5—75% P as SSP + PSB: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, T6—100% P as SSP + PSB: Pseudomonas aeruginosa)

Number of nodules and nodule dry weight per plant

And nodule dry weight was calculated 45 days after sowing by taking an average of 10 plants in each replication. The nodule number and data are presented in Fig. 3c, d. In both seasons, the maximum nodules number (155 and 158 mg) and dry weight (152 and 151 mg) were observed in T6, where the plots received 100% P as single super phosphate (SSP) with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. We observed the lowest nodule number (60 and 58 mg) in T2 and nodule dry weight (62 and 63 mg) in T2 and T3 of both seasons. Applying inorganic P fertilizer and P solubilizing bacteria significantly influenced nodule number and dry weight.

Total number of pods, pod, haulm, and biomass yield

A fully matured 110-day-old groundnut crop from season 1 and season 2 was harvested and data was recorded in Tables 2 and 3. Maximum pod yield was 2.768 t ha−1 for season 1 whereas 3.138 t ha−1 for season 2 in T6, and haulm yield was 7.106 t ha−1 and 6.246 t ha−1 were recorded for both seasons in treatment T6—100% P as SSP + Pseudomonas aeruginosa while the maximum number of pods (30.2 and 28.2) and biomass yield (9.743 t ha−1and 8.943 t ha−1) recorded in T6 for season 1 and season 2 respectively. Results also revealed yield parameters almost at par when both the strains were applied in combination with an inorganic P source (75 or 100% SSP).

Table 2.

Effect of PSB on groundnut yielding (2021–22)

| Treatments | Total no. of pods | Haulm yield (t ha−1) | Pod yield (t ha−1) | Biomass yield (t ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (Control) | 20.6 ± 0.531d | 2.737 ± 0.039c | 2.499 ± 0.387e | 4.361 ± 0.226c |

| T2 (P. aeruginosa) | 23.4 ± 0.225c | 4.593 ± 0.004b | 1.993 ± 0.152 cd | 6.782 ± 0.015b |

| T3 (100% P as SSP) | 18.3 ± 1.003c | 3.995 ± 0.013b | 2.220 ± 0.179d | 5.942 ± 0.216b |

| T4 (75% P as SSP) | 23.1 ± 1.312ab | 5.679 ± 0.221a | 2.122 ± 0.242ab | 5.897 ± 0.132a |

| T5 (75% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 24.0 ± 1.270b | 4.978 ± 0.023b | 2.298 ± 0.202bcd | 6.406 ± 0.256b |

| T6 (100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 30.2 ± 1.521ab | 7.106 ± 0.103a | 2.768 ± 0.215ab | 9.743 ± 0.563a |

Each value represents the mean of three replicates standard error (SE). Means were compared using ANOVA

Data followed by the same letters in a row are not significantly different at the level of P > 0.05

a, b, c, d, e Significant differences at the level of P > 0.05, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT)

Table 3.

Effect of PSB on groundnut yielding (2022–23)

| Treatments | Total no. of pods | Haulm yield (t ha−1) | Pod yield (t ha−1) | Biomass yield (t ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (Control) | 18.6 ± 0.651d | 2.937 ± 0.079c | 1.799 ± 0.317e | 4.481 ± 0.106c |

| T2 (P. aeruginosa) | 20.4 ± 0.425c | 4.093 ± 0.014b | 2.123 ± 0.052 cd | 6.212 ± 0.041b |

| T3 (100% P as SSP) | 20.3 ± 1.013c | 4.029 ± 0.002b | 2.200 ± 0.079d | 6.142 ± 0.086b |

| T4 (75% P as SSP) | 26.1 ± 1.812ab | 5.879 ± 0.230a | 2.592 ± 0.162ab | 8.487 ± 0.332a |

| T5 (75% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 24.0 ± 1.400b | 4.088 ± 0.017b | 2.348 ± 0.192bcd | 6.436 ± 0.206b |

| T6 (100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 28.2 ± 1.504b | 6.246 ± 1.027ab | 3.138 ± 0.178a | 8.943 ± 1.006b |

Each value represents the mean of three replicates standard error (SE). Means were compared using ANOVA

Data followed by the same letters in a row are not significantly different at the level of P > 0.05

a, b, c, d, e Significant differences at the level of P > 0.05, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT)

1000 seed mass, shelling percentage, and oil content of the groundnut kernel and enzymatic analysis

After groundnut harvesting, the mass value of 1000 kernels were recorded in two seasons and multiplied by 10 to get the data of 1000 kernels (Tables 4 and 5). We have analysed the highest seed mass (1000 kernel) weight (352.63 and 326.47 g), shelling percentage (79.14%), and oil content (46.723%) in the treatment T6—100% P as SSP + Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The control plot recorded the lowest 1000 kernel weight (197.92 g), shelling percentage (80.42 and 72.21%), and oil content (47.113 and 41.627%) for both seasons in T1, respectively. The weight of 1000 kernels were found at par in plots treated with either of the two PSB strains and 100% P as SSP. However, in the case of shelling percentage and oil content in the kernel, no significant differences were found among the treatments where PSB and P fertilizers were applied combined.

Table 4.

Effect of PSB (1000 kernel weight, oil content shelling) of groundnut yielding (2021–22)

| Treatments | 1000 kernel wt (g) | Shelling percentage (%) | Oil content in kernel (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (Control) | 207.92 ± 5.949f | 71.21 ± 0.371c | 40.967 ± 1.964c |

| T2 (P. aeruginosa) | 254.62 ± 1.678e | 74.35 ± 0.267b | 41.993 ± 0.507b |

| T3 (100% P as SSP) | 294.31 ± 2.307e | 76.16 ± 0.560b | 42.350 ± 0.665b |

| T4 (75% P as SSP) | 252.38 ± 1.670 cd | 74.46 ± 0.465b | 42.435 ± 0.032b |

| T5 (75% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 241.55 ± 4.218d | 72.65 ± 0.553b | 43.592 ± 0.133b |

| T6 (100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 352.63 ± 3.223ab | 80.42 ± 2.506a | 47.113 ± 0.904a |

Each value represents the mean of three replicates standard error (SE). Means were compared using ANOVA

Data followed by the same letters in a row are not significantly different at the level of P > 0.05

a, b, c, d, e, f Significant differences at the level of P > 0.05, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT)

Table 5.

Effect of PSB (1000 kernel weight, oil content shelling) of groundnut yielding (2022–23)

| Treatments | 1000 kernel wt (g) | Shelling percentage (%) | Oil content in kernel (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (Control) | 197.92 ± 6.049f | 72.21 ± 0.731c | 41.627 ± 0.564c |

| T2 (P. aeruginosa) | 231.63 ± 1.870e | 74.85 ± 0.167b | 42.563 ± 0.415b |

| T3 (100% P as SSP) | 236.41 ± 2.440e | 74.46 ± 0.830b | 42.560 ± 0.267b |

| T4 (75% P as SSP) | 256.78 ± 1.700 cd | 75.86 ± 0.815b | 43.670 ± 0.011b |

| T5 (75% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 248.65 ± 3.248d | 75.25 ± 0.745b | 42.672 ± 0.683b |

| T6 (100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 326.47 ± 2.147ab | 79.14 ± 1.196a | 46.723 ± 0.550a |

Each value represents the mean of three replicates standard error (SE). Means were compared using ANOVA

Data followed by the same letters in a row are not significantly different at the level of P > 0.05

a, b, c, d, e, f Significant differences at the level of P > 0.05, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT)

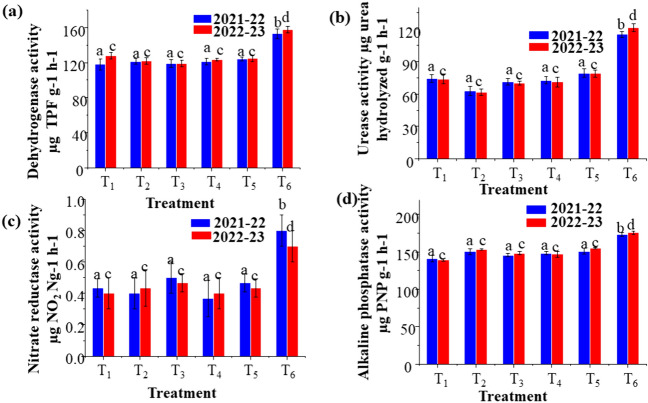

The maximum enzymatic activity is shown in T6 for both seasons 1 and 2. The maximum dehydrogenase was 153 and 158, urease was 115 and 121 whereas, nitrate reductase Activity was 0.8 and 0.7, alkaline phosphatase activity was 173 and 176 higher in treatment 6 (T6.) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Enzymatic activity of T1–T6: a dehydrogenase activity, b urease activity, c nitrate reductase activity, d alkaline phosphatase activity for the year 2021–22 and 2022–23. (T1—Control, T2—PSB: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, T3—100% P as SSP, T4—75% P as SSP, T5—75% P as SSP + PSB: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, T6—100% P as SSP + PSB: Pseudomonas aeruginosa)

Effect of PSB inoculation on nutrient concentrations of shoot and kernel

Bio inoculation with the two PSB strains positively influenced N and P concentration in the shoot and kernel. Tables 6 and 7 showed the plots treated with T6—100% P as SSP + Pseudomonas aeruginosa recorded maximum shoot N concentration (1.970 and 1.980%) for both seasons. The lowest shoot N (1.408 and 1.590%)in T5 and T1 and kernel N (4.106 and 3.556%) in T1 were found with crops grown in the control plot. Maximum shoot P (0.389 and 0.397%) and kernel P (0.592 and 0.612%) were recorded for season 1 and season 2 in the treatment T6—75% P as SSP + Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Crops grown on the control plot recorded the lowest shoot P (0.171 and 0.111%) in both T4 and kernel P (0.264 and 0.257%) in Treatment 1 and 4 for both seasons(Tables 6 and 7; Fig. 5).

Table 6.

Effect of PSB on nutrient (N, P) concentrations in groundnut (2021–22)

| Treatments | Shoot N (%) | Kernel N (%) | Shoot P (%) | Kernel P (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (Control) | 1.772 ± 0.005d | 3.569 ± 0.008c | 0.211 ± 0.008c | 0.264 ± 0.007d |

| T2 (P. aeruginosa) | 1.688 ± 0.007c | 3.627 ± 0.006b | 0.185 ± 0.006bc | 0.414 ± 0.004c |

| T3 (100% P as SSP) | 1.56 ± 0.011c | 3.676 ± 0.004b | 0.210 ± 0.004bc | 0.374 ± 0.012c |

| T4 (75% P as SSP) | 1.598 ± 0.012c | 3.794 ± 0.005b | 0.171 ± 0.003b | 0.367 ± 0.003bc |

| T5 (75% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 1.408 ± 0.004c | 3.798 ± 0.005b | 0.238 ± 0.006b | 0.423 ± 0.004bc |

| T6 (100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 1.970 ± 0.020b | 4.106 ± 0.008a | 0.389 ± 0.023a | 0.592 ± 0.014a |

Each value represents the mean of three replicates standard error (SE). Means were compared using ANOVA

Data followed by the same letters in a row are not significantly different at the level of P > 0.05

a, b, c, d significant differences at the level of P > 0.05, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT)

Table 7.

Effect of PSB on nutrient (N, P) concentrations in groundnut (2022–23)

| Treatments | Shoot N (%) | Kernel N (%) | Shoot P (%) | Kernel P (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (Control) | 1.590 ± 0.010d | 3.556 ± 0.007c | 0.111 ± 0.005c | 0.257 ± 0.007d |

| T2 (P. aeruginosa) | 1.758 ± 0.005c | 3.782 ± 0.006b | 0.194 ± 0.003bc | 0.405 ± 0.004c |

| T3 (100% P as SSP) | 1.755 ± 0.003c | 3.780 ± 0.008b | 0.187 ± 0.002bc | 0.389 ± 0.012c |

| T4 (75% P as SSP) | 1.790 ± 0.008c | 3.800 ± 0.005b | 0.111 ± 0.003b | 0.257 ± 0.003bc |

| T5 (75% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 1.788 ± 0.006c | 3.798 ± 0.003b | 0.224 ± 0.003b | 0.453 ± 0.004bc |

| T6 (100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) | 1.980 ± 0.020b | 3.956 ± 0.004a | 0.397 ± 0.015a | 0.612 ± 0.014a |

Each value represents the mean of three replicates standard error (SE). Means were compared using ANOVA

Data followed by the same letters in a row are not significantly different at the level of P > 0.05

a, b, c, d Significant differences at the level of P > 0.05, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT)

Fig. 5.

Growth of groundnut under different treatments: Growth of groundnut cv. Debi due to application of PSB strains (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) a T1 is the control plant, whereas the T2 plant was developed by adding Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PSB), b 100% P as SSP (Single Super Phosphate), c T1 is the control plant where T4 was developed with (75% P as SSP + Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PSB), d T1 is the control plant where T5 was developed with 75% P as SSP (Single Super Phosphate), e T1 is the control plant where T5 was developed with 100% P as SSP + Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Correlation network analysis between soil properties, oil content, and P (Phosphorus) accumulation

Phosphate solubilizing bacteria (PSB) are crucial to enhancing groundnut productivity by improving soil quality and facilitating its transformation. Such microbes not only assimilate phosphorus but also cause a large amount of soluble phosphate to be released over their requirements. In this experiment, we have analyzed that PSB strain enhances pod yield, haulm yield, and nutrient(Nitrogen and Phosphate) uptake in groundnuts over control (Tables 2, 3 and 4, 5). Here, we have observed that SSP + P. aeruginosa treatment (T6) increased groundnut yield second-fold than the other treatments and increased pod yields from 2.5 t/ha in control to 2.8 t /ha in T6 for season 2021–22. Similarly, for 2022–23, pod yields increased from 1.8 t/ha in control to 3.1 t /ha in T6. After applying PSB in the field, the oil content of ground nut also increased from other treatments. Here, we have found that the oil content of control (T1) was 40.9%, while Treatment 6 (T6) was 47.1%. These studies have shown that biofertilizers, when combined with organic sources increase the essential nutrient level in the soil post-harvest. The phosphorus (P) content was 2.41 mg/kg–1 before the experiment, and after groundnut harvesting, the P content was 52.5 mg/kg–1, which increased in T6 with the use of 100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa (Table 1).

Principal component (PCA) analysis of treatments

PCA is a statistical technique that identifies significant characteristics of a dataset. This method reduces data dimension by transforming variables into new principal components and retaining total variation using fewer components. In a study on peanut ecotypes, PCA extracted normalized principal component scores from a correlation matrix using average values. Principal component scores with eigenvalues > 1 were selected. Here the higher eigenvalues were considered as the best grown treatments. We observed that only one treatment (T6) showed more than 1 eigenvalue. The principal component analysis (PCA) results showed that the total variation exhibited by PC 1 and PC 2 was 91.57 and 5.54%, respectively (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Biplot PCA (principal component analysis) of groundnut (Plant height, Nodule dry weight, Nodule number per plant, and the number of branches) with six treatments for two seasons (Year 2021–2022 and 2022–2023). The first and second components account for 91.57 and 5.54% of the variation, respectively. Eigenvector plots can be interpreted as follows: (‘T’/Red dot indicates first season experiment and ‘t’/ black dot indicates second season experiment). In both seasons, T6 showed higher plant growth than the other treatments

Discussion

Phosphorus is crucial for metabolic processes in legume crops, including shoot organs, energy generation, nucleic acid synthesis, photosynthesis, and respiration (Singh et al. 2022). Phosphorus is present in soil as primary P minerals like apatite and secondary clay minerals such as calcium, iron, and aluminum phosphates. These minerals help maintain phosphorus buildup and availability via desorption and dissolution processes (Mitran and Mani 2017). In this experiment, we have analyzed two seasons (2021–22 and 2022–23) to confirm the results. Earlier, Ghadamgahi et al. (2022) reported that Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) that is a potential strain for biofertilizer production. Here, we have applied 100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa as biofertilizer and the field experiment revealed the increased haulm yield, pod yield biomass yield, and total number of pods (Tables 2 and 3). Oil content in the kernel and shelling percentage were recorded with the combined application of PSB and SSP compared to the sole application of 100% P as SSP + Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Previously, Verma et al. (2014) reported that the integrated application of organics and fertilizers has increased the 1000-grain weight by enhancing flowering and seed formation. 1000 grain weight was significantly higher in treatment 6 (T6) with 100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa. similarly, Li et al. (2017) reported that using PSB (Phosphate Solubilizing Bacterial) increases maize growth and enhances yielding. After inoculation with PSB, earlier wheat also showed increased plant growth and nutrient uptake under field conditions (Viruel et al. 2014). In the present study, we found both strains comparatively efficient in solubilizing P in soil and increasing plant and crop-yielding P content. However, no significant variation was observed among the plots imposed with inorganic and biofertilization in nodule number and dry weight. The untreated control plot was determined as the lowest nodule nos. and was also significantly inferior compared to treated plots. In chickpeas and other pulses also noticed enhancement in nodulation in inoculation of P solubilizers, along with the application of P fertilizers (Bilal et al. 2021).

Due to low pH, P fixation could be termed as a characteristic feature of the experimental site. Owing to the acid soil chemistry applied P fertilizers would have got fixed and plants are unable to utilize the phosphate in these bound forms (Wang et al. 2020). Hence, the combined application of P solubilizing bacteria and a single super phosphate could have offered more soluble P to groundnut plants for uptake and growth promotion in contrast to the sole application of either PSB or inorganic P fertilizer. P-solubilizing bacteria can drag the soluble or available P from organic and mineral sources (Wan et al. 2020). Previously, Phosphate solubilization was reported to increase crop yield in field conditions (Timofeeva et al. 2022). Due to enzymatic activity, these PSBs are found to mineralize insoluble phosphates into soluble forms. Earlier, it was reported that PSB-produced organic acids like malic, succinic, fumaric, citric, tartaric acid, and alpha-ketoglutaric acid increase the grain quality and the total yield (Chen et al. 2023a, b). Similarly, in this experiment, we have reported T6 with 100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa produces healthy groundnut plants with enhancing yield. After harvesting the groundnut, the soil also maintains its nutrients and quality. The present study shows that both strains (75% P as SSP + P. Aeruginosa and 100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa) are comparatively efficient in solubilizing P in soil and increasing plant and crop yielding. However, no significant variation was observed among the plots imposed with inorganic and biofertilization in nodule number and dry weight. The untreated control plot was determined as the lowest nodule nos. and was significantly inferior compared to treated plots. Earlier Wang et al. (2021) reported microbial biomass increased enzyme activities in agricultural farming. In this experiment, we also encountered enzymatic activity such as (a) Dehydrogenase activity, (b) Urease activity, (c) Nitrate reductase Activity, (d) Alkaline phosphatase activity was improved in Treatment 6 (T6) by applying 100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa. Khatkar et al. (2007) also observed yield improvement with microbial inoclulation of urdbean seeds. Here, we have also analyzed that after harvesting groundnut (T6 in both seasons), P availability improves in the soil. Similarly, in 2022, Adnan et al. (2022) reported that inoculation (PSB) effectively improved wheat growth, P nutrition, and soil acidification.

According to the PCA analysis, PC1 (91.57%) was positively associated with plant growth. High PC1 values are considered good growth and yield under normal conditions with 100% P as SSP + P. aeruginosa. PC2 showed 5.54% of the variation (total growth variation). The results showed that T6 was closely located to the best growth parameters with high PC1 as compared to PC2 values. These findings are similar to Zeng et al. (2020), who found that lower PC2 and higher PC1 scores had good growth and yields.

Conclusion

In recent research, plant scientists, agronomists, and agro-industries use microbial solubilization of P and SSP. Bacterial P solubilization has multiple biotechnological applications that provide efficacious products and is applied for interacting with plant microbes and P in the agricultural field. Previously researchers documented the effects of PSB on root growth and availability of P in the rhizosphere. Rhizosphere microbes play a vital role in transforming, mobilizing, and solubilizing nutrients from limited nutrient pools and crop plants’ successful uptake of required nutrients. Hence, beneficial plant–microbe interaction is the major determinant of sustainable agricultural production. In conclusion, the PSB strain with SSP showed higher efficiency in enhancing pod quality and yield in groundnut cultivation. Hence, appropriate formulation with these PSB strains would be potential phosphorus biofertilizers for sustaining groundnut production. Previously, various researchers reported on the PSB effect and their benefits for agriculture, but those results are not very effective for groundnut farming. In this regard, our experiment benefits groundnut plants and increases soil fertility and phosphate for plant nutrition in the local field.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Centurion University of Technology and Management, Bhubaneswar, India for providing the necessary support to complete this manuscript.

Author contributions

MDM, RKS and NT conceived the manuscript. MDM created figures, and tables and wrote the manuscript with the help of RKS and NT.

Data availability

The findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ranjan Kumar Sahoo, Email: ranjan.sahoo@cutm.ac.in.

Narendra Tuteja, Email: narendratuteja@gmail.com.

References

- Aasfar A, Bargaz A, Yaakoubi K, Hilali A, Bennis I, Zeroual Y, MeftahKadmiri I (2021) Nitrogen fixing azotobacter species as potential soil biological enhancers for crop nutrition and yield stability. Front Microbiol 12:628379–628398 10.3389/fmicb.2021.628379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M, Fahad S, Saleem MH et al (2022) Comparative efficacy of phosphorous supplements with phosphate solubilizing bacteria for optimizing wheat yield in calcareous soils. Sci Rep 12:11997 10.1038/s41598-022-16035-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews EM, Kassama S, Smith EE, Brown PH, Khalsa SDS (2021) A review of potassium-rich crop residues used as organic matter amendments in tree crop agroecosystems. Agriculture 11(7):580–603 10.3390/agriculture11070580 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtaoui N, Rabiu MK, Raklami A, Oufdou K, Hafidi M, Jemo M (2021) Phosphate-dependent regulation of growth and stresses management in plants. Front Plant Sci 12:679916–679936 10.3389/fpls.2021.679916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belayneh DB, Chondie YG (2022) Participatory variety selection of groundnut (Arachishypogaea L.) in Taricha Zuriya district of Dawuro Zone, southern Ethiopia. Heliyon 8:e09011 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y, Zhou H (2021) Changes in peanut canopy structure and photosynthetic characteristics induced by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in a nutrient-poor environment. Sci Rep 11:14832–14842 10.1038/s41598-021-94092-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal S, Hazafa A, Ashraf I, Alamri S, Siddiqui MH, Ramzan A, Qamar N, Sher F, Naeem M (2021) Comparative effect of inoculation of phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria and phosphorus as sustainable fertilizer on yield and quality of mung bean (Vignaradiata L.). Plants 10:2079–2086 10.3390/plants10102079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary PB, Chaudhary Shah SK, MG, Patel JK and Chaudhary KV, (2019) Effect of potassium on growth, yield and quality of groundnut (Arachishypogaea L.) grown in loamy sand soil. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 8(9):2723–2731 10.20546/ijcmas.2019.809.313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Yu F, Kang J, Li Q, Warusawitharana HK, Li B (2023a) Quality chemistry, physiological functions, and health benefits of organic acids from tea (Camelliasinensis). Molecules 28(5):2339 10.3390/molecules28052339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Gao J, Chen H, Zhang Z, Huang J, Lv L, Tan J, Jiang X (2023b) The role of long-term mineral and manure fertilization on P species accumulation and phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms in paddy red soils. SOIL 9:101–116 10.5194/soil-9-101-2023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel AI, Fadaka AO, Gokul A, Bakare OO, Aina O, Fisher S, Burt AF, Mavumengwana V, Keyster M, Klein A (2022) Biofertilizer: the future of food security and food safety. Microorganisms 10(6):1220 10.3390/microorganisms10061220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A, Kumar S, Ganga Rao NVPR (2023) Potential for increasing groundnut production in Tanzania by enhancing technical efficiency: a stochastic meta-frontier analysis. Front Sustain Food Syst 7:1027270–1027282 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1027270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desmae H, Janila P, Okori P, Pandey MK, Motagi BN, Monyo E, Mponda O, Okello D, Sako D, Echeckwu C, Oteng-Frimpong R, Miningou A, Ojiewo C, Varshney RK (2019) Genetics, genomics and breeding of groundnut (Arachishypogaea L.). Plant Breed 138(4):425–444 10.1111/pbr.12645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djuuna IAF, Prabawardani S, Massora M (2022) Population distribution of phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms in agricultural soil. Microbes and environments 37(1):ME21041 10.1264/jsme2.ME21041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahde S, Boughribil S, Sijilmassi B, Amri A (2023) Rhizobia: a promising source of plant growth-promoting molecules and their non-legume interactions: examining applications and mechanisms. Agriculture 13(7):1279 10.3390/agriculture13071279 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frezarin ET, Santos CHB, Sales LR, dos Santos RM, de Carvalho LAL, Rigobelo EC (2023) Promotion of peanut (Arachishypogaea L.) growth by plant growth-promoting microorganisms. Microbiol Res 14:316–332 10.3390/microbiolres14010025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghadamgahi F, Tarighi S, Taheri P, Saripella GV, Anzalone A, Kalyandurg PB, Catara V, Ortiz R, Vetukuri RR (2022) Plant growth-promoting activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa FG106 and its ability to act as a biocontrol agent against potato. Tomato Taro Pathog Biol (basel) 11(1):140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick BR, Karaturovic DM, Newell PC (1995) A novel procedure for rapid isolation of plant growth promoting pseudomonads can. J Microbiol 41:533–536 [Google Scholar]

- Goyal RK, Habtewold JZ (2023) Evaluation of legume–rhizobial symbiotic interactions beyond nitrogen fixation that help the host survival and diversification in hostile environments. Microorganisms 11:1454–1470 10.3390/microorganisms11061454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R, Li H, Gao C, Yu W, Zhang S (2023) Advances in omics research on peanut response to biotic stresses. Front Plant Sci 14:1101994 10.3389/fpls.2023.1101994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson ML (1975) Soil chemical analysis. Prentice Hall of India Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi [Google Scholar]

- Janati W, Bouabid R, Mikou K, Ghadraoui LE, Errachidi F (2023) Phosphate solubilizing bacteria from soils with varying environmental conditions: occurrence and function. PLoS ONE 18(12):e0289127 10.1371/journal.pone.0289127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johan PD, Ahmed OH, Omar L, Hasbullah NA (2021) Phosphorus transformation in soils following co-application of charcoal and wood ash. Agronomy 11:2010–2035 10.3390/agronomy11102010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khatkar R, Abraham T, Joseph AS (2007) Effect of bio fertilizers and sulphur levels on growth and yield of black gram (Vignamungo L.). Legume Res 30(3):233–234 [Google Scholar]

- Kondapalli R, Naga Jyoti Ch, Singh BJ, Dawson J, Krupakar A (2015) Growth of groundnut (Arachishypogaea L.) and its yield as influenced by foliar spray of boron along with rhizobium inoculation. Indian J Dryland Agric Res 30(1):60–63 10.5958/2231-6701.2015.00009.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Kumar T, Singh S, Tuteja N, Prasad R, Singh J (2020) Potassium: a key modulator for cell homeostasis. J Biotechnol 324:198–210 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu X, Hao T, Chen S (2017) Colonization and maize growth promotion induced by phosphate solubilizing bacterial isolates. Int J Mol Sci 18(7):1253. 10.3390/ijms18071253 10.3390/ijms18071253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhu H, Li H, Zhang Y, Xu S, Cai S, Sulaiman AA, Kuzyakov A, Rengel Z, Zhang D (2023) Dynamics of root–microbe interactions governing crop phosphorus acquisition after straw amendment. Soil Biol Biochem 181:109039 10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Hosseini Bai S, Wang J, Hu D, Wu R, Zhang W, Zhang M (2022) Strain klebsiella ZP-2 inoculation activating soil nutrient supply and altering soil phosphorus cycling. J Soils Sediments 22:2146–2157 10.1007/s11368-022-03221-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long H, Wasaki J (2023) Effects of Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria on soil phosphorus fractions and supply to maize seedlings grown in lateritic red earths and cinnamon soils. Microbes Environ 38(2):ME22075 10.1264/jsme2.ME22075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathivanan J, Jayaraman P (2019) Enhancement of growth and yield of Arachishypogeae L. using different biofertil. Int Lett Nat Sci 14:1–9 [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood N, Saeed M, Zafarullah S, Hyder S, Rizvi ZF, Gondal AS, Jamil N, Iqbal R, Ali B, Ercisli S, Kupe M (2023) Multifaceted impacts of plant-beneficial pseudomonas spp. in managing various plant diseases and crop yield improvement. ACS Omega 8(25):22296–22315 10.1021/acsomega.3c00870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra S, Rayaguru K, Dash SK, Mohanty S, Panigrahi C (2022) Efficacy of microwave irradiation in enhancing the shelf life of groundnut (Arachishypogaea L.). J Stored Prod Res 97:101957 10.1016/j.jspr.2022.101957 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitran T, Mani PK (2017) Effect of organic amendments on rice yield trend, phosphorus use efficiency, uptake, and apparent balance in soil under long-term rice-wheat rotation. J Plant Nutr 40(9):1312–1322 10.1080/01904167.2016.1267205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JAMES, Riley JP (1962) A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal Chim Acta 27:31–36. 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)88444-5 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)88444-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ojiewo CO, Janila P, Bhatnagar-Mathur P et al (2020) Advances in crop improvement and delivery research for nutritional quality and health benefits of groundnut (Arachishypogaea L.). Front Plant Sci 11:29 10.3389/fpls.2020.00029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oteng-Frimpong R, Kassim YB, Puozaa DK, Nboyine JA, Issah A-R, Rasheed MA, Adjebeng-Danquah J, Kusi F (2021) Characterization of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) test locations using representative testing environments with farmer-preferred traits. Front Plant Sci 12:637860. 10.3389/fpls.2021.637860 10.3389/fpls.2021.637860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page AL, Miller RH and Keeny DR (1982) Methods of soil and plant analysis, part-2, 2nd Edn. No (9) Part in the series, American Society of Agronomy, Inc. Soil Science Society of American Journal. Madison, Wisconsin, U.S.A.

- Pradhan M, Sahoo RK, Pradhan C, Tuteja N, Mohanty S (2017) Contribution of native phosphorous-solubilizing bacteria of acid soils on phosphorous acquisition in peanut (Arachishypogaea L.). Protoplasma 254(6):2225–2236 10.1007/s00709-017-1112-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodic I, KrstićRistivojević M, Smiljanić K (2023) Antioxidant properties of protein-rich plant foods in gastrointestinal digestion—peanuts as our antioxidant friend or foe in allergies. Antioxidants 12(4):886 10.3390/antiox12040886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puppala N, Nayak SN, Sanz-Saez A, Chen C, Devi MJ, Nivedita N, Bao Y, He G, Traore SM, Wright DA, Pandey MK, Vinay Sharma (2023) Sustaining yield and nutritional quality of peanuts in harsh environments: physiological and molecular basis of drought and heat stress tolerance. Front Genet 14:1121462 10.3389/fgene.2023.1121462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi S, Petermann BJ, Brevik SJJ, EC, Gedeon C, (2023) Predicting microbial responses to changes in soil physical and chemical properties under different land management. Appl Soil Ecol 188:104878 10.1016/j.apsoil.2023.104878 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sah S, Krishnani S, Singh R (2021) Pseudomonas mediated nutritional and growth promotional activities for sustainable food security. Curr Res Microb Sci 2:100084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Bhatt R, S DS, et al (2022) Integrated use of phosphorus, farmyard manure and biofertilizer improves the yield and phosphorus uptake of black gram in silt loam soil. PLoS ONE 17(4):e0266753 10.1371/journal.pone.0266753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Tariq MR, Shaheen F, Mustafa S, Ali S, Fatima A, Shafiq M, Safdar W, Sheas MN, Hameed A, Nasir MA (2022) Phosphate solubilizing microorganisms isolated from medicinal plants improve growth of mint. Peer J 10:e13782–e13794 10.7717/peerj.13782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Ge F, Zhang D, Deng S, Liu X (2021) Roles of phosphate solubilizing microorganisms from managing soil phosphorus deficiency to mediating biogeochemical p cycle. Biology 10(2):158 10.3390/biology10020158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timofeeva A, Galyamova M, Sedykh S (2022) Prospects for using phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms as natural fertilizers in agriculture. Plants 11:2119–2142 10.3390/plants11162119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma G, Kumawat N, Morya J (2014) Nutrient management in mung bean [Vignaradiate (L.) Wilczek] for higher production and productivity under semi-arid tract of central India. Int J Curr Microbial App Sci 6(7):488–493 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.607.058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viruel E, Erazzu LE, Calsina LM, Ferrero MA, Lucca ME, Sineriz F (2014) Inoculation of maize with phosphate solubilizing bacteria: effect on plant growth and yield. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 14(4):819–831 [Google Scholar]

- Wan W, Qin Y, Wu H, Zuo W, He H, Tan J, Wang Y, He D (2020) Isolation and characterization of phosphorus solubilizing bacteria with multiple phosphorus sources utilizing capability and their potential for lead immobilization in soil. Front Microbiol 11:752–768 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Yang Z, Kong Y, Li X, Li W, Du H, Zhang C (2020) GmPAP12 Is required for nodule development and nitrogen fixation under phosphorus starvation in soybeans. Front Plant Sci 11:450–462 10.3389/fpls.2020.00450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Kaur M, Zhang P, Li J, Xu M (2021) Effect of different agricultural farming practices on microbial biomass and enzyme activities of celery growing field soil. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(23):12862 10.3390/ijerph182312862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright WD, Wilkinson DR (1993) Automated Micro-Kjeldahl nitrogen determination: A method. Am Environ Lab 5:30–33 [Google Scholar]

- Zeng R, Chen L, Wang X, Cao J, Li X, Xu X, Xia Q, Chen T, Zhang L (2020) Effect of waterlogging stress on dry matter accumulation, photosynthesis characteristics, yield, and yield components in three different ecotypes of peanut (Arachishypogaea L.). Agronomy 10(9):1244 10.3390/agronomy10091244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.