Abstract

Psoriasis is accepted as a chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated skin disease triggered by complex environmental and genetic factors. For a long time, disease recurrence, drug rejection, and high treatment costs have remained enormous challenges and burdens to patients and clinicians. Natural products with effective immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activities from medicinal plants have the potential to combat psoriasis and complications. Herein, an imiquimod (IMQ)-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis model is established in mice. The model mice are treated with 1% rutaecarpine (RUT) (external use) or the oral administration of RUT at different concentrations. Furthermore, high-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing is applied to analyze the changes in the diversity and composition of the gut microbiota. Based on the observation of mouse dorsal skin changes, RUT can protect against inflammation to improve psoriasis-like skin damage in mice. Additionally, RUT could suppress the expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-23, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-6, and IFN-α) within skin tissue samples. Concerning gut microbiota, we find obvious variations within the composition of gut microflora between IMQ-induced psoriasis mice and RUT-treated psoriasis mice. RUT effectively mediates the recovery of gut microbiota in mice induced by IMQ application. Psoriasis is linked to the production of several inflammatory cytokines and gut microbiome alterations. This research shows that RUT might restore gut microbiota homeostasis, reduce inflammatory cytokine production, and ameliorate psoriasis symptoms. In conclusion, the gut microbiota might be a therapeutic target or biomarker for psoriasis that aids in clinical diagnosis and therapy.

Keywords: psoriasis, rutaecarpine (RUT), inflammatory factor, gut microbiota

Introduction

Psoriasis is accepted as a chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated skin disease triggered by complex environmental and genetic factors. It is estimated to affect at least 200 million people globally [1]. Worse still, psoriasis greatly promotes the incidence rate of psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, obesity, depression, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and even carcinoma [ 2– 4]. Psoriasis is characterized by raised red scaly plaques caused by excessive keratinocyte proliferation and abnormal keratinocyte differentiation [5]. A previous study highlighted a strong link between excessive keratinocyte proliferation and increased infiltration of inflammatory cells. Specifically, this includes T lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (DCs) [6]. This whole process is intrinsically driven by inflammatory factors, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-17A, IL-22, IL-23, and IL-1β [ 7, 8]. Currently, psoriasis can be treated primarily through topical corticoids, vitamin D analogs, phototherapy, local treatment, and systemic drug treatment [ 5, 9]. However, these therapeutic methods may be accompanied by disease recurrence, drug rejection, and high costs [10]. Therefore, it is of great urgency to explore safer, cheaper, and more effective natural products with effective immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory activities from medicinal plants to battle psoriasis and associated consequences.

Rutaecarpine (RUT), an important bioactive alkaloid isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa, is a versatile natural Chinese herbal medicine [11]. RUT shows extensive pharmacological application in the improvement and treatment of inflammation, hyperlipidemia, immune response, allergic reactions, various cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, metabolic diseases, and even cancer [ 12, 13]. It has been shown that RUT intrinsically has anti-injury biological characteristics, which can help to inhibit inflammatory cell infiltration and improve inflammation and tissue proliferation [ 14– 16]. Evidently, RUT can reduce inflammatory reactions by inhibiting NF-κB transcription activity in bacterial lipoteichoic acid (LTA)-induced macrophages [17]. RUT can alleviate immune metabolism-related diseases (including atopic dermatitis and rhinitis) by inhibiting the biosynthesis of inflammatory factors (TNF-α and IL-4) within immunoglobulin E (IgE)-antigen complex-induced RBL2H3 cells [18]. Additionally, we have previously reported that RUT cream can reduce the release of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC)- and Th17-related factors through the NF-κB and TLR7 pathways, thereby reducing inflammation in serum and skin lesions and improving psoriatic dermatitis in mice [19] .

Recent studies on psoriasis-related microbiota have revealed a tight link between the intestinal microbiota and skin. The alterations within the gut microbiota composition facilitate the reproduction of bacteria, thus driving psoriasis progression [ 20 , 21]. Numerous studies have shown that damaged intestinal integrity and increased permeability contribute to several issues [ 22, 23]. These include imbalance in the intestinal environment and breakdown of the intestinal barrier, which lead to systemic inflammation. This inflammation, in turn, activates both local and systemic immune responses that can result in psoriasis. Additionally, this process releases various factors, such as TNF-α, IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 [20].

Herein, we established an imiquimod (IMQ)-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis model in mice. The mRNA expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines within skin tissues and the changes in gut microbiota diversity and composition of the model mice were examined after RUT treatment. This study revealed the role of RUT in mediating intestinal flora to improve psoriasis.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of experimental materials

RUT was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, USA). IMQ cream (5%, Aldara) was obtained from 3 M Pharmaceuticals (Saint Paul, USA). RUT cream (0.1%, 0.5%, and 1%) was supplied by the Department of Pharmacy, the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. Lanolin (Sinopharm, Shanghai, China) was used as the matrix excipients of the RUT creams.

Establishment of the psoriasis-like dermatitis mouse model

All experiments involving animals in this study were carried out in accordance with the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of the University of South China. Healthy male BALB/c mice aged 8 weeks ( n=48) were randomly assigned into 8 groups after being shaved to back skin: (i) the control group (serve as control for IMQ group), (ii) IMQ group, (iii) IMQ + Matrix excipient group (serve as control for IMQ+1% RUT group), (iv) IMQ+1% RUT group, (v) IMQ+phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) group (serve as control for IMQ+20/40/80 mg/kg/d RUT), (vi) IMQ+20 mg/kg/d RUT group, (vii) IMQ+40 mg/kg/d RUT group, and (viii) IMQ+80 mg/kg/d RUT group. Specifically, in the IMQ model, IMQ cream (80 mg, containing 5% IMQ) was applied topically to the shaved back skin of mice daily in the morning from day 1 to day 7 to develop a psoriasis-like dermatitis mouse model. Twelve hours after IMQ administration, 1% RUT cream was applied daily in the evening to the shaved back skin of mice from day 1 to day 7 (IMQ+1% RUT group) according to our prior research [19]. The IMQ+Matrix excipient group was given the blank excipient of the 1% RUT cream. Alternatively, model mice in the RUT oral gavage groups (IMQ+20 mg/kg/d RUT group, IMQ+40 mg/kg/d RUT group, and IMQ+80 mg/kg/d RUT group) received a different dose of RUT (20/40/80 mg/kg, i.g.) once per day from day 1 to day 7. The selection of oral gavage concentrations of RUT was modified based on previous studies [ 24– 26]. Model mice in the IMQ+PBS group were given the same volume of PBS. Twenty-four hours after the final administration of IMQ, the fecal samples, peripheral blood, and skin lesion tissue samples of mice were collected for PASI scoring and histological analysis; the mouse back skin was photographed, and the alterations in the mouse back skin within each group were recorded.

PASI assessment

The PASI score was applied to evaluate skin inflammation severity. According to the clinical PASI score but adjusted for the mouse model, the affected skin area was not included within the overall score. Erythema and scale severity were assessed using a 5-point scale, where 0=no symptoms, 1=slight, 2=moderate, 3=marked, and 4=very marked.

H&E staining

After being fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), processed, and paraffin-embedded, tissues were sectioned (5 μm in thickness) and stained using H&E staining solution (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) as directed by the manufacturer. The stained sections were imaged using a BX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

IHC staining

To evaluate IL-23 and IL-17A expression levels, sections were incubated for 30 min with a blocking solution (3.75% BSA/5% goat serum; Zymed, Carlsbad, USA), followed by 2 h of incubation with anti-IL-23 (ab189300; Abcam, Cambridge, USA) or anti-IL-17 A (26163-1-AP; Proteintech, Wuhan, China) antibodies, and a 30-min incubation with a biotin-labelled secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) at 37°C, and then a 20-min incubation with HRP-labelled streptavidin (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Next, sections were subjected to counterstaining with hematoxylin (Beyotime) after incubation with freshly prepared DAB reagent (Beyotime). Finally, the BX51 microscope was employed to visualize the sections.

Western blot analysis

The skin tissues were lysed on ice using RIPA lysis buffer. A bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Beyotime) was utilized as per the manufacturer’s protocol to determine the protein concentration. All samples were adjusted to the same protein concentration by adding PBS, and then subjected to 6% or 10% SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were electroblotted from the gel onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. After being blocked for 1 h with 5% skim milk, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (1:1000) overnight at 4°C. Next, the membranes were washed thrice with TBST, followed by 1 h of incubation with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500; Abcam) at room temperature. Finally, an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Beyotime) was employed to develop the membranes, and protein bands were analyzed with a Tanon5500 automatic imaging system (Tanon, Shanghai, China).

16S rRNA gene sequencing and analysis

The fecal samples of mice in the control group (Class1), IMQ group (Class2), IMQ+Matrix excipient group (Class3), IMQ + 1% RUT group (Class4), IMQ+PBS group (Class5), and IMQ + 80 mg/kg/d RUT group (Class6) were harvested and kept at –80°C. The fecal genomic DNA extraction kit (dp328-02; Tiangen, Beijing, China) was applied according to the manufacturer’s protocol to extract DNA from 200 mg fecal samples. The concentration was detected using the dsDNA HS Assay Kit for Qubit (12640ES76; Yishen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and adaptor addition were carried out using phusion enzyme (K1031; ApexBio, Shanghai, China) and primers in the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene (341F 5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′ and 805R 5′-GACTACHVGGGTWTCTCATATCC-3′). The BMSX-200 kit (Baimag Biotechnology, Wuxi, China) was utilized to sort the magnetic beads. An Agarose Gel DNA Recovery Kit (dp209-03; Tiangen) was employed to conduct DNA recovery. The raw data were obtained by sequencing the samples using a NovaSeq 6000 PE250 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Next, following quality control of raw data using QIIME 2 (version 2020.2) and DADA2, clean data were obtained and utilized for future analysis [27]. By using QIIME2, the Silva-132-99 representative sequence database classifier was trained for species annotation and alignment of representative sequences for each operational taxonomic unit (OTU) sequence. Sequence data analysis was conducted using QIIME 2 (version 2020.2) and R software (version 4.0.2) [27]. The α-diversity indexes, including Chao1, ACE, Shannon, and Simpson evenness index, were calculated. Next, an OTU-based ranked abundance curve and an α-diversity-based dilution curve were drawn. Using R software (version 4.0.2), the histogram of relative species abundance (R ggplot2 package), the heatmap of genus abundance (R reshape2/ggplot2 package), the box plot of α-diversity difference (R phyloseq package), the principal component analysis (PCA) and nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on the Bray-Curtis distance (phyloseq/vegan package), and the phylogenetic diversity analysis based on the Wald test (R DESeq2 package) were drawn. R software (Venn diagram package) was employed to generate the list of OTUs owned by specimens or groups. Next, the jvenn ( http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/static/others/jvenn/example.html) web pages were applied to visualize common and specific OTUs across specimens or groups.

Statistical analysis

At least six replicates were set for each experiment. GraphPad software (GraphPad, San Diego, USA) was employed to process the data. All data are presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD). Before processing, all relevant data were examined for normal distribution and variance homogeneity. The Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized for data distribution analysis and the selection of statistical techniques (parametric or nonparametric). The Brown-Forsythe test was applied for the comparison of group variances. The Kruskal-Wallis test was utilized for nonparametric statistical analysis. Comparisons between groups were conducted using Student’s t test. If the data did not have equal variances and had a normal distribution, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett T3 was used to examine differences between two or more groups. A one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test was used when the variances of the data were equivalent. The significance level was set at P<0.05.

Results

RUT ameliorated skin damage in IMQ-induced psoriasis-like mice

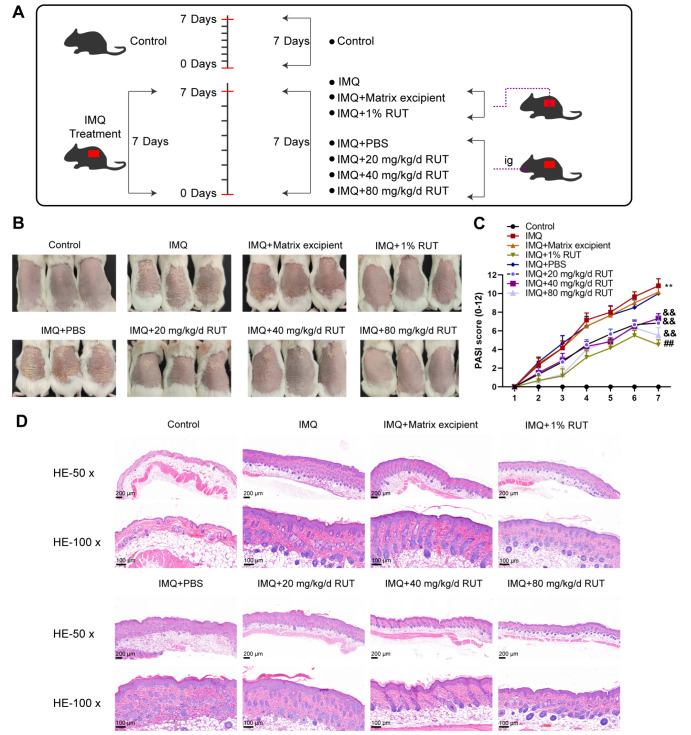

To verify the therapeutic effect of RUT on IMQ-induced psoriasis mice, 1% RUT or orally-administered different concentrations of RUT was applied to the mice for 7 consecutive days ( Figure 1A). Specifically, mice were grouped into control, IMQ+Matrix excipient, IMQ+1% RUT, IMQ+PBS, IMQ+20 mg/kg/d RUT, IMQ+40 mg/kg/d RUT, and IMQ+80 mg/kg/d RUT groups. The morphological changes of IMQ-induced psoriatic dermatitis in mice were observed and assessed by PASI score; mouse dorsal skin was evaluated from the aspect of erythema, scale, and skin thickness. As shown by the phenotype results, IMQ-induced psoriatic mice exhibited reddened skin and serious wrinkles and scales; 1% RUT application effectively improved the erythema and epidermal scale on the back skin of IMQ-induced psoriasis-like model mice ( Figure 1B). Additionally, RUT by oral administration exerted therapeutic effects on erythema and scaling on mouse dorsal skin in a dose-dependent manner. The above results showed that both external use (application) and intragastric administration of RUT could efficiently reduce the PASI score of IMQ-induced mice; 1% RUT application and 80 mg/kg/d RUT oral administration showed the best effect on reducing the PASI score of IMQ-induced mice, with no significant difference ( Figure 1C). According to H&E staining results of skin tissue sections, mice in the IMQ group, IMQ+Matrix excipient group, and IMQ+PBS group showed epidermal acanthosis, elongated rete ridges, inflammatory cell infiltration in the superficial dermis, spongy edema, vascular dilation, and increased hair follicles. However, 1% RUT application effectively reduced epidermal cell proliferation and inflammatory cell infiltration, while oral administration of RUT improved tissue proliferation and inflammatory cell infiltration in mouse skin in a dose-dependent manner ( Figure 1D).

Figure 1 .

Rutaecarpine (RUT) ameliorated imiquimod (IMQ)-induced psoriasis-like skin damage in mice

(A) Schematic diagram of model establishment and RUT administration. (B) Mice were grouped into control, IMQ, IMQ+Matrix excipient, IMQ+1% RUT, IMQ+oral phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 20/40/80 mg/kg/d RUT groups; the appearance of the dorsal skin was examined. (C) The psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score evaluations. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for pathological changes (50×, 100×). Data are presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. Scale bar: 100 or 200 μm. n=6, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to the control group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 compared to the IMQ+matrix excipient group; &&P<0.01 compared to the IMQ+PBS excipient group.

RUT downregulated inflammatory cytokines in IMQ-induced psoriasis-like mice

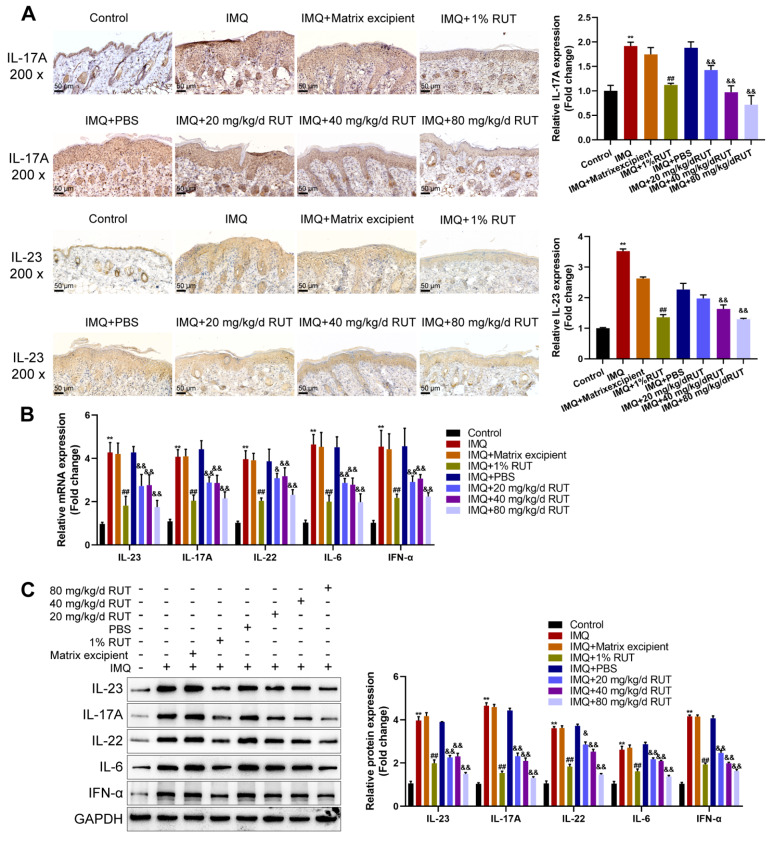

According to IHC staining, the levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-23 and IL-17A) were remarkably elevated in the IMQ group and the IMQ+Matrix excipient group compared with the normal control group, and were effectively inhibited after 1% RUT applcation; compared with those in the IMQ+PBS group, IL-23 and IL-17A levels were dramatically decreased with the increase in oral RUT concentration ( Figure 2A). Furthermore, the mRNA expressions of proinflammatory factors (IL-23, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-6, and IFN-α) within the skin lesions was detected by qRT-PCR. The mRNA expression levels of the above cytokines were remarkably elevated within the IMQ group, IMQ+Matrix excipient group, and IMQ+PBS group compared to the normal control; no obvious variation was found among these groups. Both 1% RUT application and oral administration of RUT could effectively suppress the mRNA expression levels of these proinflammatory factors; among different concentrations of oral RUT, 80 mg/kg/d RUT exhibited the most significant inhibitory effect on the above cytokines ( Figure 2B). Furthermore, similar results were obtained in the western blot analysis results. The protein levels of IL-23, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-6, and IFN-α were notably increased within the lesions in the IMQ modelling groups; both 1% RUT for external use and different concentrations of RUT for oral use effectively reduced the protein levels of these above cytokines. Among all oral RUT groups, 80 mg/kg/d RUT showed the best inhibitory effect, but the protein levels of these cytokines were still increased compared with those of the normal control ( Figure 2C). Taken together, both external and internal administration of RUT improved the inflammatory response of IMQ-induced psoriatic lesions in mice, as manifested by the decreased expression levels of proinflammatory factors (IL-23, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-6, and IFN-α).

Figure 2 .

RUT downregulated inflammatory cytokines in IMQ-induced psoriasis-like mice

(A) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays (left) and corresponding quantitative analysis (right) were performed to measure the levels of IL-23 and IL-17A in skin tissues from different groups (200×). Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) qRT-PCR was used to analyze the mRNA expressions of inflammatory cytokines (IL-23, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-6, and IFN-α) in skin tissues. (C) Western blot analysis was used to detect the protein levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-23, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-6, and IFN-α). Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments. n=6, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to the control group; #P<0.05, ## P<0.01 compared to the IMQ+Matrix excipient group; & P<0.05, &&P<0.01 compared to the IMQ+PBS excipient group.

RUT affected the diversity of gut microbiota in psoriasis-like mice

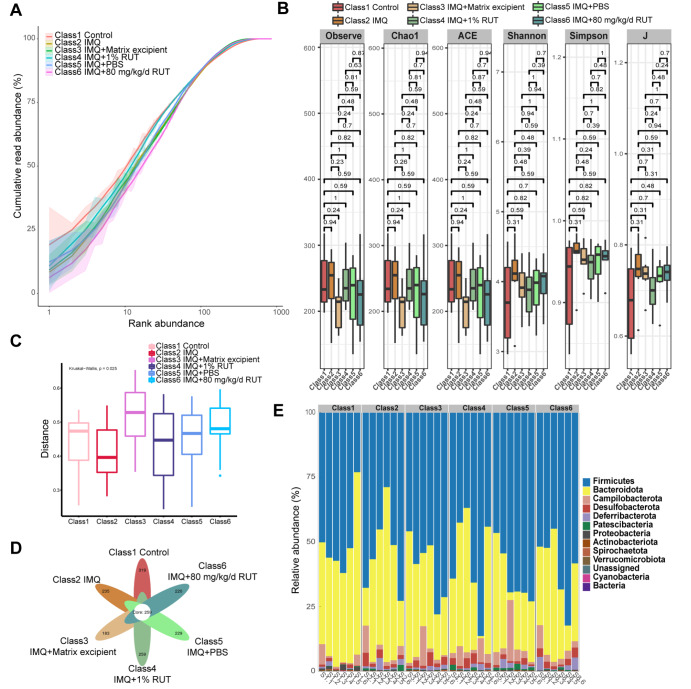

First, according to the H&E staining results of intestinal tissues, IMQ and RUT had no effect on intestinal permeability ( Supplementary Figure S1). The pathological results of intestinal tissues showed no obvious shortening or deletion of the colonic recess, no increase in inflammatory cells in the mucosa, and no obvious inflammatory infiltration in any group of mice. Then, to explore the effect of RUT on the gut microflora of psoriasis-like mice, fecal samples from mice in different groups (control group, IMQ group, IMQ+Matrix excipient group, IMQ+1% RUT group, IMQ+PBS group, and IMQ+80 mg/kg/d RUT group) were collected for 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The diversity and composition of mouse gut microflora were analyzed. As shown by the abundance curve, the read-length abundance of each sample increased rapidly as the sequencing depth increased and then plateaued. These results indicated a sufficient sequencing depth ( Figure 3A). According to the results of the alpha-diversity index analysis of intestinal microbiota, no significant difference in α-diversity was observed among groups ( Figure 3B). The β-diversity showed significant differences among the groups ( Figure 3C). According to the Venn diagram, 578, 494, 442, 518, 488, and 479 microbiota were annotated in the control group, IMQ group, IMQ+matrix excipient group, IMQ+1% RUT group, IMQ+PBS group, and IMQ+80 mg/kg/d RUT group, respectively; among these groups, 259 common OTUs were identified; and there were 259 (44.81%‒58.6%) overlapping OTUs among samples in the above six groups ( Figure 3D). Furthermore, the relative abundance of intestinal microbiota was annotated at the phylum level, including Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Campilobacterota, Desulfobacterota, Deferribacterota, Patescibacteria, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Spirochaeta, Verrucomicrobiota, and Cyanobacteria ( Figure 3E).

Figure 3 .

RUT affected the diversity of the gut microbiota in psoriasis-like dermatitis mice

(A) The rank abundance curve was used to evaluate sequencing depth. (B,C) The α-diversity and β-diversity analysis of gut microbiota was performed. (D) Venn diagram showing changes in the number of gut microbiota. (E) The relative abundance of gut microbiota at the phylum level. n=6.

RUT affected the composition and abundance of the gut microbiota of psoriasis-like mice

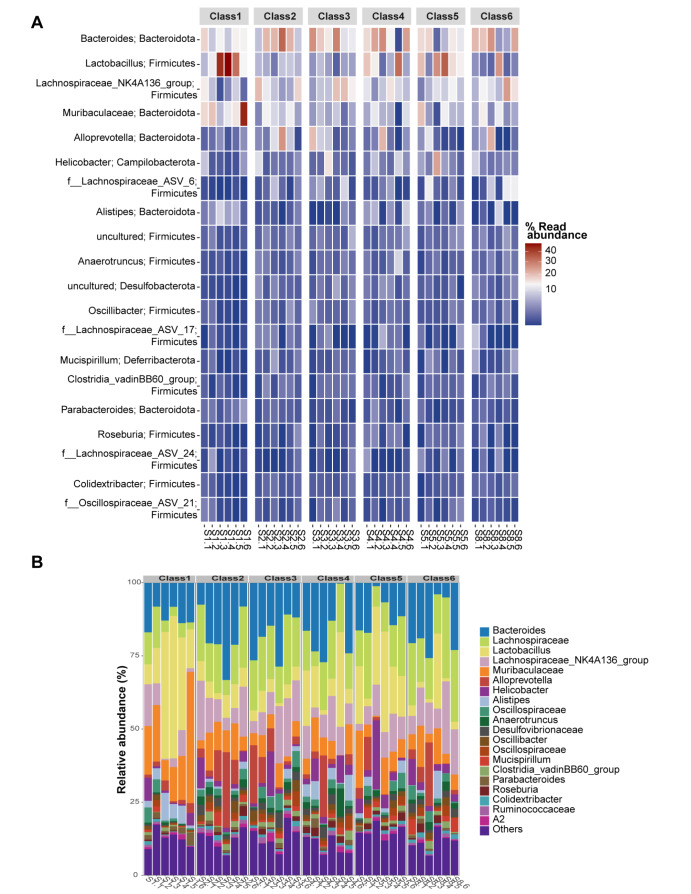

By analyzing the diversity of intestinal microbiota in each group, we subsequently tested the relative abundance of intestinal microbiota. The heatmap of the top 20 genera-phylum gut microbiota in different samples/groups is displayed. They primarily belong to Bacteroides, Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Firmicutes, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Firmicutes, Alloprevotella, Bacteroidota, Alloprevotella, Bacteroidota, and Helicobacterota (Campilobacterota) ( Figure 4A). Additionally, the relative abundance of gut microflora was annotated at the genus level; Bacteroides, Lachnospiraceae Lactobacillus, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, Muribaculaceae, Alloprevotella, Helicobacter, Alistipes, Oscillospiraceae, Anaerotruncus, Desulfovibrionaceae, Oscillibacter, Oscillospiraceae, Mucispirillum, Clostridia vadinBB60_group, Parabacteroides Roseburia, Colidextribacter, Ruminococcaceae, A2, and others are shown ( Figure 4B). From the above findings, IMQ decreased but RUT intervention efficiently increased the intestinal microbiota diversity within IMQ-induced psoriasis mice.

Figure 4 .

RUT affected the composition and abundance of the gut microbiota

(A) Heatmap analysis showing the relative abundance of the top 20 genera-phylum gut microbiota in different samples/groups. (B) Relative abundance of gut microbiota at the genus level. n=6.

RUT altered the gut microbiota structure within psoriasis-like mice

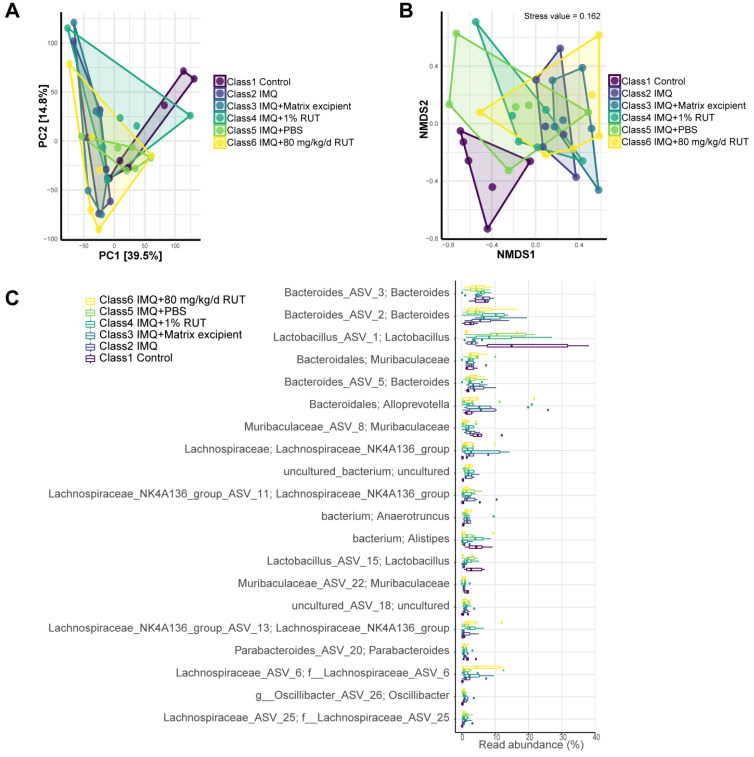

Next, the intestinal microbiota diversity was analyzed using PCA. The PCA results revealed that PC1 is 39.5% and PC2 is 14.8%, which indicated that RUT explained 54.3% of the difference in microbiota composition ( Figure 5A). According to the NMDS analysis results, the stress value is 0.162 (less than 0.2), indicating significant differences between groups ( Figure 5B). Changes within the intestinal microbiota abundance are shown at the genus level. Compared to the IMQ model group, the abundance of beneficial bacteria (including Lactobacillus, Alistipes and Muribaculaceae) was higher in the normal control, IMQ+1% RUT, and IMQ+PBS groups; however, Helicobacter abundance was relatively high in the IMQ+1% RUT, IMQ+PBS, and IMQ+80 mg/kg/d RUT groups ( Figure 5C and Table 1). According to the results, compared to the normal control, beneficial bacteria (such as Lactobacillus, Alistipes, and Murbaculaceae) showed decreased abundance, and other pathogenic bacteria showed increased abundance in the IMQ group ( Figure 5C and Table 2). Relative to the IMQ+Matrix excipient group, the IMQ+1% RUT group exhibited increase in beneficial bacteria abundance (such as Lactobacillus, Alistipes, and Muriaculaceae) ( Figure 5C and Table 2). Compared with the IMQ+PBS group, the IMQ+80 mg/kg/d RUT group exhibited a decreased abundance of beneficial bacteria (such as Lactobacillus and Alistipes) and an increased abundance of other pathogenic bacteria ( Figure 5C). Taken together, 1% RUT external application may exert better effects than 80 mg/kg/d RUT oral application on the homeostasis of gut microbiota in IMQ model mice.

Figure 5 .

RUT altered the structure of the gut microbiota

(A) Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to analyze the diversity of gut microbiota. (B) Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was used to analyze the differences between groups. (C) The abundance of gut microbiota changes is shown at the species level. n=6.

Table 1 Comparison of the abundance of dominant bacteria in different groups with that in Class2 (IMQ group)

|

Species_Genus |

Class2 vs |

||||

|

Class1 |

Class3 |

Class4 |

Class5 |

Class6 |

|

|

Bacteroides |

– |

ns |

ns |

– |

ns |

|

Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group |

– |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

|

Lactobacillus |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

|

Muribaculaceae |

+ |

– |

– |

ns |

ns |

|

Helicobacter |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Alloprevotella |

– |

ns |

– |

– |

– |

|

Oscillibacter |

– |

ns |

– |

– |

– |

|

Anaerotruncus |

– |

ns |

ns |

– |

ns |

|

Clostridia_vadinBB60_group |

– |

+ |

– |

ns |

ns |

|

Alistipes |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

Class1: control group; Class2: IMQ group; Class3: IMQ+Matrix excipient group; Class4: IMQ+1% RUT group; Class5: IMQ+PBS group; Class6: IMQ+80 mg/kg/d RUT group; ns: no significance; +: upregulated; –: downregulated.

Table 2 Comparison of the abundance of dominant bacteria among different control groups

|

Species_Genus |

Class2 vs Class1 |

Class4 vs Class3 |

Class6 vs Class5 |

|

Bacteroides |

+ |

ns |

+ |

|

Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group |

+ |

– |

+ |

|

Lactobacillus |

– |

+ |

– |

|

Muribaculaceae |

– |

+ |

ns |

|

Helicobacter |

+ |

+ |

– |

|

Alloprevotella |

+ |

– |

+ |

|

Oscillibacter |

+ |

– |

+ |

|

Anaerotruncus |

+ |

ns |

+ |

|

Clostridia_vadinBB60_group |

+ |

– |

ns |

|

Alistipes |

– |

+ |

_ |

Class1: control group; Class2: IMQ group; Class3: IMQ+Matrix excipient group; Class4: IMQ+1% RUT group; Class5: IMQ+PBS group; Class6: IMQ+80 mg/kg/d RUT group; ns: no significance; +: upregulated; –: downregulated.

Discussion

Psoriasis is a multifactorial chronic and relapsing immune-mediated disease that can activate the immune system through toll-like receptor 7/8 (TLR 7/8) [28]. Psoriasis is characterized by dendritic cell and inflammatory cell infiltration within the epidermis/dermis, aberrant keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation, and the release of various inflammatory cytokines by Th17 cells, Th1 cells, and keratinocytes [29]. Psoriasis pathogenesis is intrinsically associated with the abnormal immune response activated by the ecological imbalance of gut microbiota [30]. As pointed out previously, healthy gut microbiota can protect the skin, while deregulated gut microbiota can deteriorate psoriasis symptoms [31]. Our previous research showed that RUT can alleviate IMQ-induced psoriasis-like inflammation [19]. Nevertheless, the RUT mechanism within the gut microbiota remains unclear. Herein, based on the observation of mouse dorsal skin changes, RUT can protect against inflammation to improve psoriasis-like skin damage in mice. Additionally, RUT could repress the expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-23, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-6, and IFN-α) within skin tissue samples and effectively mediate the recovery of gut microbiota in IMQ-induced mice.

Accumulating studies have shown that dysregulated gut microbiota triggers T-cell differentiation; the overactivation of Treg/Th17 cells regulates the immune response by releasing various inflammatory factors (IL-23, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-6, and IFN-α), thereby contributing to psoriasis progression [ 32– 34]. Herein, RUT was shown to effectively inhibit the release of proinflammatory factors in IMQ-induced psoriasis mice. It has been previously reported that the gut microbiota exerts a critical effect on abnormal immune responses [35]. The imbalance of gut microbiota may influence the onset and recurrence of psoriasis [ 36, 37]. This interaction between gut microbes could be closely linked to physiological shifts and immune metabolism in psoriasis patients. Moreover, the spectrum of gut microbiota detected in psoriasis has been found to be similar to that of inflammatory bowel disease [38]. Cohort studies revealed notable differences in gut microbiota between psoriasis patients and healthy controls [ 37, 39, 40]. Specifically, psoriasis patients had lower bacterial diversity and abundance. They also showed an increase in Firmicutes and a decrease in Bacteroidetes. Consistent findings were observed in this study. IMQ-induced psoriasis mice were treated with external and oral RUT, and their gut microflora was then analyzed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis. Significant variations were observed within the composition of gut microflora between IMQ-induced psoriasis mice and RUT-treated psoriasis mice. The changes in Bacteroides, Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Firmicutes, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Firmicutes, Alloprevotella, Bacteroidota, Alloprevotella, Bacteroidota, and Helicobacter, Campilobacterota may be involved in psoriasis treatment. Additionally, compared with that in the IMQ + Matrix excipient group, mouse gut microbiota from the IMQ + 1% RUT group were characterized by an increase in beneficial bacteria (such as Lachnospiracea, Alistipes, and Murbaculacea).

It has been proven that Lactobacillus and its family members play crucial roles in psoriasis. A high Lactobacillus reuteri abundance within the microbiota protects mice against psoriasis-like inflammation [41]. Oral administration of Lactobacillus pentosus GMNL-77 effectively reduced the mRNA expressions of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-23/IL-17A axis-related factors, such as IL-23, IL-17A/F, and IL-22 in the skin of IMQ-induced mice [42]. Additionally, pentosus GMNL-77 significantly alleviated psoriasis symptoms by reducing erythema and scaling. Alistipes have been found to increase in many pathological processes, which are anti-inflammatory in multiple diseases, including colitis, cancer immunotherapy, and cardiovascular diseases [ 43 – 45]. Furthermore, Alistipes have been noticeably increased in treated psoriasis patients [37]. Murbaculaceae, which is widely present in the main gut microbiota of healthy intestines, is positively correlated with the immune response. Murbaculaceae family members can interact with innate and adaptive immune responses through IgA coating [ 46, 47]. In this study, RUT demonstrated a potential therapeutic effect on psoriasis-like dermatitis in mice by modulating the gut microbiota. Specifically, RUT enhanced the abundance of key bacterial taxa, including Lactobacillus, Alistipes, and Muriaculaceae. This microbial modulation was associated with a mitigation of the hyperactivated inflammatory state characteristic of psoriatic dermatitis, subsequently alleviating cutaneous lesion symptoms.

It is worth mentioning that numerous studies have provided evidence for the existence of the gut–skin axis, which is dependent on the microbiome [48]. The gut–skin axis is the novel concept of the interaction between skin diseases and the microbiome through inflammatory mediators, metabolites, and the intestinal barrier [49]. The gut–skin axis is a bidirectional pathway connecting the gut and skin [50]. In this study, external administration of RUT may affect the diversity, composition, and abundance of the gut microbiota in psoriasis-like mice via the gut–skin axis. In addition, psoriasis-like mice may ingest RUT on their skin during grooming, affecting the gut microbiota.

Nevertheless, there are still some limitations in this study, which require further elaboration. We only revealed the alteration of gut microbiota in IMQ-induced mice by RUT but did not provide direct evidence to support a causal relationship between RUT and the gut microbiota. In future experiments, we may further confirm the effect of RUT on gut microbiota in IMQ-induced mice by conducting experiments such as depletion of gut microbiota with cocktail of antibiotics or fecal microbiota transplantation. Despite the best therapeutic effect of 80 mg/kg/d RUT (oral) on psoriasis-like dermatitis mice, the abundance of beneficial bacteria (Lachnospiraceae, Alistipes, and Muribaculaceae) was decreased. However, 1% RUT for external use could effectively increase the above beneficial bacteria. Hence, whether oral administration of an excessive dose of RUT exerts adverse effects on restoring gut microbiota disorders in psoriasis-like dermatitis mice needs further validation.

In summary, the occurrence of psoriasis is tightly related to the release of numerous proinflammatory cytokines and changes within the gut microbiota. The results of this study confirmed that RUT can restore gut microbiota homeostasis, inhibit excessive inflammatory cytokine production, and ultimately improve the pathological process of psoriasis. The gut microbiota may act as a therapeutic target or biomarker of psoriasis to play crucial roles in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of psoriasis.

Supporting information

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data is available at Acta Biochimica et Biphysica Sinica online.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the grant from the Natural Science Foundation of Changsha (No. kq2202410).

References

- 1.Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker JNWN. Psoriasis. Lancet. . 2021;397:1301–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng Z, Guo Q, Ma D, Wang X, Zhang C, Wang H, Zhang L, et al. Related risk factors and treatment management of psoriatic arthritis complicated with cardiovascular disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. . 2022;9:835439. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.835439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duvetorp A, Mrowietz U, Nilsson M, Seifert O. Sex and age influence the associated risk of depression in patients with psoriasis: a retrospective population study based on diagnosis and drug-use. Dermatology. . 2021;237:595–602. doi: 10.1159/000509732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trafford AM, Parisi R, Kontopantelis E, Griffiths CEM, Ashcroft DM. Association of psoriasis with the risk of developing or dying of cancer. JAMA Dermatol. . 2019;155:1390–1403. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. . 2019;20:1475. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajguru JP, Maya D, Kumar D, Suri P, Bhardwaj S, Patel ND. Update on psoriasis: a review. J Family Med Prim Care. . 2020;9:20–24. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_689_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ni X, Lai Y. Keratinocyte: a trigger or an executor of psoriasis? J Leukocyte Biol. . 2020;108:485–491. doi: 10.1002/JLB.5MR0120-439R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamanaka K, Yamamoto O, Honda T. Pathophysiology of psoriasis: a review. J Dermatol. . 2021;48:722–731. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid C, Griffiths CEM. Psoriasis and treatment: past, present and future aspects. Acta Derm Venerol. . 2020;100:70–80. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camela E, Potestio L, Fabbrocini G, Ruggiero A, Megna M. New frontiers in personalized medicine in psoriasis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. . 2022;22:1431–1433. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2022.2113872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Ge J, Zheng Q, Zhang J, Sun R, Liu R. Evodiamine and rutaecarpine from Tetradium ruticarpum in the treatment of liver diseases . Phytomedicine. . 2020;68:153180. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byun WS, Bae ES, Kim WK, Lee SK. Antitumor activity of rutaecarpine in human colorectal cancer cells by suppression of Wnt/β-Catenin signaling. J Nat Prod. . 2022;85:1407–1418. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.2c00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian K, Li J, Xu S. Rutaecarpine: a promising cardiovascular protective alkaloid from Evodia rutaecarpa (Wu Zhu Yu) . Pharmacol Res. . 2019;141:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia S, Hu C. Pharmacological effects of rutaecarpine as a cardiovascular protective agent. Molecules. . 2010;15:1873–1881. doi: 10.3390/molecules15031873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han M, Hu L, Chen Y. Rutaecarpine may improve neuronal injury, inhibits apoptosis, inflammation and oxidative stress by regulating the expression of ERK1/2 and Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in rats with cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Drug Des Devel Ther. . 2019;13:2923–2931. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S216156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai QY, Li WR, Wei JJ, Mi SQ, Wang NS. Antinociceptive activity of aqueous and alcohol extract of evodia rutaecarpa. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2014, 76: 235–239 . [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Jayakumar T, Yang CM, Yen TL, Hsu CY, Sheu JR, Hsia CW, Manubolu M, et al. Anti-Inflammatory mechanism of an alkaloid rutaecarpine in LTA-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells: pivotal role on NF-κB and ERK/p38 signaling molecules. Int J Mol Sci. . 2022;23:5889. doi: 10.3390/ijms23115889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z, Yang M, Peng Y, Gao M, Yang B. Rutaecarpine ameliorated sepsis-induced peritoneal resident macrophages apoptosis and inflammation responses. Life Sci. . 2019;228:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Zhang G, Chen M, Tong M, Zhao M, Tang F, Xiao R, et al. Rutaecarpine inhibited imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis via inhibiting the NF-κB and TLR7 pathways in mice. Biomed Pharmacother. . 2019;109:1876–1883. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okada K, Matsushima Y, Mizutani K, Yamanaka K. The role of gut microbiome in psoriasis: oral administration of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus danieliae exacerbates skin inflammation of imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis . Int J Mol Sci. . 2020;21:3303. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soare A, Weber S, Maul L, Rauber S, Gheorghiu AM, Luber M, Houssni I, et al. Cutting edge: homeostasis of innate lymphoid cells is imbalanced in psoriatic arthritis. J Immunol. . 2018;200:1249–1254. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells JM, Brummer RJ, Derrien M, MacDonald TT, Troost F, Cani PD, Theodorou V, et al. Homeostasis of the gut barrier and potential biomarkers. Am J Physiol Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. . 2017;312:G171–G193. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00048.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez-Lopez M, Iborra S, Conde-Garrosa R, Mastrangelo A, Danne C, Mann ER, Reid DM, et al. Microbiota sensing by mincle-syk axis in dendritic cells regulates interleukin-17 and -22 production and promotes intestinal barrier integrity. Immunity. . 2019;50:446–461.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang LY, Yeh SL, Hsu ST, Chen CH, Chen CC, Chuang CH. The anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of rutaecarpine on human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell line CE81T/VGH in vitro and in vivo . Int J Mol Sci. . 2022;23:2843. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Yan T, Sun D, Xie C, Wang T, Liu X, Wang J, et al. Rutaecarpine inhibits KEAP1-NRF2 interaction to activate NRF2 and ameliorate dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Free Radical Biol Med. . 2020;148:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu QN, Zhang D, Jin T, Wu Q, Liu J, Lu YF. Rutaecarpine effects on expression of hepatic phase-1, phase-2 metabolism and transporter genes as a basis of herb–drug interactions. J Ethnopharmacol. . 2013;147:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. . 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vičić M, Kaštelan M, Brajac I, Sotošek V, Massari LP. Current concepts of psoriasis immunopathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. . 2021;22:11574. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korman NJ. Management of psoriasis as a systemic disease: what is the evidence? Br J Dermatol. . 2020;182:840–848. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buhaș MC, Gavrilaș LI, Candrea R, Cătinean A, Mocan A, Miere D, Tătaru A. Gut microbiota in psoriasis. Nutrients. . 2022;14:2970. doi: 10.3390/nu14142970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Shi L, Sun T, Guo K, Geng S. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota and its correlation with dysregulation of cytokines in psoriasis patients. BMC Microbiol. . 2021;21:78. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02125-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamada N, Seo SU, Chen GY, Núñez G. Role of the gut microbiota in immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. . 2013;13:321–335. doi: 10.1038/nri3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muromoto R, Hirao T, Tawa K, Hirashima K, Kon S, Kitai Y, Matsuda T. IL-17A plays a central role in the expression of psoriasis signature genes through the induction of IκB-ζ in keratinocytes. Int Immunol. . 2016;28:443–452. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxw011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lochner M, Wang Z, Sparwasser T. The special relationship in the development and function of T helper 17 and regulatory T cells. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015, 136: 99–129 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly-Y M, Glickman JN, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. . 2013;341:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan LR, Zhao S, Zhu W, Wu L, Li J, Shen MX, Lei L, et al. The Akkermansia muciniphila is a gut microbiota signature in psoriasis . Exp Dermatol. . 2018;27:144–149. doi: 10.1111/exd.13463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Gomez J, Delgado S, Requena-Lopez S, Queiro-Silva R, Margolles A, Coto E, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in a cohort of patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. . 2019;181:1287–1295. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu Y, Lee CH, Chi CC. Association of psoriasis with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA Dermatol. . 2018;154:1417–1423. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen YJ, Ho HJ, Tseng CH, Lai ZL, Shieh JJ, Wu CY. Intestinal microbiota profiling and predicted metabolic dysregulation in psoriasis patients. Exp Dermatol. . 2018;27:1336–1343. doi: 10.1111/exd.13786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang HW, Yan D, Singh R, Liu J, Lu X, Ucmak D, Lee K, et al. Alteration of the cutaneous microbiome in psoriasis and potential role in Th17 polarization. Microbiome. . 2018;6:154. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0533-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen HL, Zeng YB, Zhang ZY, Kong CY, Zhang SL, Li ZM, Huang JT, et al. Gut and cutaneous microbiome featuring abundance of lactobacillus reuteri protected against psoriasis-like inflammation in mice. J Inflamm Res. . 2021:6175–6190. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S337031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen YH, Wu CS, Chao YH, Lin CC, Tsai HY, Li YR, Chen YZ, et al. Lactobacillus pentosus GMNL-77 inhibits skin lesions in imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mice. J Food Drug Anal. . 2017;25:559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dziarski R, Park SY, Kashyap DR, Dowd SE, Gupta D. Pglyrp-regulated gut microflora Prevotella falsenii, Parabacteroides distasonis and Bacteroides eggerthii enhance and Alistipes finegoldii attenuates colitis in mice. PLoS One. 2016, 11: e0146162 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Iida N, Dzutsev A, Stewart CA, Smith L, Bouladoux N, Weingarten RA, Molina DA, et al. Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science. . 2013;342:967–970. doi: 10.1126/science.1240527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshida N, Yamashita T, Hirata K. Gut microbiome and cardiovascular diseases. Diseases. . 2018;6:56. doi: 10.3390/diseases6030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hevia A, Milani C, Lopez P, Cuervo A, Arboleya S, Duranti S, Turroni F, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. mBio. 2014, 5: e01548–01514 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Moschen AR, Gerner RR, Wang J, Klepsch V, Adolph TE, Reider SJ, Hackl H, et al. Lipocalin 2 protects from inflammation and tumorigenesis associated with gut microbiota alterations. Cell Host Microbe. . 2016;19:455–469. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olejniczak-Staruch I, Ciążyńska M, Sobolewska-Sztychny D, Narbutt J, Skibińska M, Lesiak A. Alterations of the skin and gut microbiome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. . 2021;22:3998. doi: 10.3390/ijms22083998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sikora M, Stec A, Chrabaszcz M, Knot A, Waskiel-Burnat A, Rakowska A, Olszewska M, et al. Gut microbiome in psoriasis: an updated review. Pathogens. . 2020;9:463. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9060463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thye AYK, Bah YR, Law JWF, Tan LTH, He YW, Wong SH, Thurairajasingam S, et al. Gut-Skin axis: unravelling the connection between the gut microbiome and psoriasis. Biomedicines. . 2022;10:1037. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10051037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.