Abstract

PURPOSE

Childhood cancer survivors are at increased risk for underinsurance and health insurance–related financial burden. Interventions targeting health insurance literacy (HIL) to improve the ability to understand and use health insurance are needed.

METHODS

We codeveloped a four-session health insurance navigation tools (HINT) intervention, delivered synchronously by a patient navigator, and a corresponding booklet. We conducted a randomized pilot trial with survivors from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study comparing HINT with enhanced usual care (EUC; booklet). We assessed feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy (HIL, primary outcome; knowledge and confidence with health insurance terms and activity) on a 5-month survey and exit interviews.

RESULTS

Among 231 invited, 82 (32.5%) survivors enrolled (53.7% female; median age 39 years, 75.6% had employer-sponsored insurance). Baseline HIL scores were low (mean = 28.5; 16-64; lower scores better); many lacked knowledge of Affordable Care Act (ACA) provisions. 80.5% completed four HINT sessions, and 93.9% completed the follow-up survey. Participants rated HINT’s helpfulness a mean of 8.9 (0-10). Exit interviews confirmed HINT’s acceptability, specifically its virtual and personalized delivery and helpfulness in building confidence in understanding one’s coverage. Compared with EUC, HINT significantly improved HIL (effect size = 0.94. P < .001), ACA provisions knowledge (effect size = 0.73, P = .003), psychological financial hardship (effect size = 0.64, P < .006), and health insurance satisfaction (effect size = 0.55, P = .03).

CONCLUSION

Results support the feasibility and acceptability of a virtual health insurance navigation program targeted for childhood survivors to improve HIL. Randomized trials to assess the efficacy and sustainability of health insurance navigation on HIL and financial burden are needed.

BACKGROUND

Fortunately, over 85% of children diagnosed with cancer will become 5-year survivors. However, these survivors are at increased risk for early, high cumulative burden of chronic health conditions and shortened life spans. Thus, it is not surprising that adult survivors of childhood cancer face high levels of financial hardship that is exacerbated by the complexity of navigating and managing health care and insurance in the United States. Survivors require ongoing medical care to monitor and treat late effects, which include new cancers, cardiac complications, reproductive issues, cognitive deficits, liver dysfunction, and other physical and psychosocial sequelae.1–11 Ongoing medical treatment and surveillance, with access to quality health care and insurance coverage, are critical.

Long-term childhood survivors are less likely to be insured and more likely to experience underinsurance than their siblings.12 They also have lower coverage expectations and have more difficulties understanding how to use their coverage.4 Compared with siblings, childhood survivors are more likely to demonstrate psychological financial burden (worry about being unable to pay for a needed treatment, worry they would not be able to afford to fill a prescription), material financial burden (percentage of income on out-of-pocket medical costs, problems paying medical bills, money borrowed because of medical expenses), and behavioral financial burden (deferring care or skipping a test, treatment, or follow-up).4,13–16 Finally, using National Health Interview Survey data to compare adult survivors of childhood cancer to adults in the US general population without cancer, significantly more childhood survivors reported being uninsured, and experiencing behavioral and material financial burden (delaying medical care, needing but not getting medical care, and having trouble paying medical bills).17

Low health insurance literacy (HIL)—the degree to which individuals have reduced knowledge, ability, and confidence to find and evaluate information about health plans, select the best plan for their own financial and health circumstances, and use the plan once enrolled—likely exacerbates the access to care and financial burden faced by survivors.18 HIL is necessary to help childhood cancer survivors manage health care costs and obtain appropriate survivorship care,19,20 and literacy is crucial for patients to manage the complex, evolving health insurance system.21,22 Studies have demonstrated that cancer survivors, and those in the general population, with low HIL report financial hardship and skipped care, including cancer survivorship care, more than individuals with high HIL.19,23–25 Thus, HIL should be a primary target for interventions.

Informed by Levy and Meltzer’s (2001) model40 of the relationship between health insurance and health and Andersen and Aday’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use, we designed a health insurance navigation intervention targeting long-term childhood cancer survivors’ health care and medical needs through improving their health HIL and corresponding financial hardship. Although interventions have sought to address the financial needs of survivors of adult-onset cancers, to our knowledge, none to date have targeted survivors of childhood cancer HIL and resultant financial hardship.26 We report on the intervention development and randomized pilot trial results of a health insurance navigation tools (HINT) program.

METHODS

Study Overview

This multiphase trial was conducted within the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). CCSS is a National Cancer Institute (NCI)–funded multi-institutional study of individuals who were diagnosed before age 21 years at one of 31 institutions in the United States with leukemia, CNS malignancies, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, soft tissue sarcoma, or bone cancer and survived at least 5 years. The Massachusetts General Hospital and St Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Review Boards approved all study procedures. We consented participants before their participation in study activities (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04520061).

Design

In accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) stage model for behavioral intervention development,27 our team previously documented the need and interest for a health insurance intervention for long-term childhood survivors (Stage 0).12–17,28–32 Stage I involved program creation and preliminary testing; in Stage IA, we developed and refined the intervention (four sessions and a corresponding booklet) by interviewing survivors and experts and conducting an open pilot trial with eight survivors.

Stage IB was a pilot randomized controlled trial in which participants were randomly assigned to receive the HINT intervention, which consisted of four biweekly Zoom sessions with a patient navigator and the HINT booklet or the HINT booklet only (enhanced usual care [EUC]). After Stage IB, intervention participants were invited to complete exit interviews, aimed to assess participants’ (1) satisfaction with the intervention, (2) recommendations for intervention delivery, and (3) recommendations for modifications on overall session topics and intervention content. Interviews were 20 minutes, administered via videoconferencing (Zoom). The exit interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using NVivo qualitative software. Content analyses were conducted and reviewed by coinvestigators.

Intervention Development and Description (Stage IA)

The proposed content was informed by previous research findings indicating that childhood survivors were underinsured, experienced financial burden, and lacked knowledge about health insurance–related policies, including the Affordable Care Act (ACA), that could enable them to obtain lower-cost coverage and preventive services without cost-sharing.12–14,16 We conducted in-depth interviews with 18 experts (eg, clinicians, advocates, and financial navigators) and 11 survivors from the CCSS cohort to obtain recommendations for developing the HINT intervention’s structure, modality, and content. Survivors confirmed the proposed individual session format, as privacy was prioritized over a group shared experience. Virtual delivery of four sessions was confirmed as a method to enhance accessibility and engagement.

HINT was designed to provide a supportive, individualized approach, and sessions were structured according to the NCI 5As model of brief counseling with key informational content provided.33 Sessions provided psychoeducation about health insurance policy and coverage in the context of patients’ survivorship care, with a focus on overcoming barriers to insurance access and use. Sessions one and two included information on the ACA, prevention guidelines, and coverage models, and include strategies to identify types of coverage needed. Sessions three and four included training and support for survivors to empower them to challenge coverage denials, seek lower-cost alternatives, and discuss out-of-pocket costs.

We conducted open pilot sessions with eight insured survivors from the CCSS who had access to a wireless device. The pilot confirmed that education was needed on appeals, cost management strategies, health insurance–related legislation, and long-term follow up care. Pilot participants confirmed participant preferences for the individualized nature of the intervention as well as the interest in cost and planning with an acknowledgment that these topics were stressful. The HINT intervention content is outlined in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

For this pilot study, one navigator was recruited from outside our institution and was an integral part of developing the intervention. This navigator completed several trainings from organizations including Triage Cancer and the Association of Community Cancer Centers on insurance, financial resources, and survivorship. This individual also had nearly 10 years of experience working as a patient navigator in clinical cancer settings for a large advocacy organization, during which they provided patients with cancer health insurance navigation and addressed financial concerns. The navigator presently participates in regular trainings to stay informed of any changes to health insurance policy.

Randomized Pilot Trial (Stage IB)

Recruitment and Procedures

Survivors who had health insurance, were at least age 18 years, were able to provide informed consent, had access to the Internet, and did not participate in an earlier phase of this study were eligible. Participants were randomly selected, stratified by state Medicaid expansion status, and recruited from August 2020 to July 2021 via a combined outreach of emails, mails, and phone calls. Participants completed an online screening survey, consent form, and baseline survey via research electronic data capture. Participants were then randomly assigned to the intervention arm or EUC and were sent an online survey at 5-month follow-up; participants were remunerated $20 in US dollars for each survey.

Measures

Sociodemographic and Treatment Information

Sociodemographic and health insurance information (eg, policy holder, satisfaction, and annual deductible) were collected at the baseline survey. Cancer and medical history data were obtained through CCSS medical records data (eg, cancer diagnosis, age at diagnosis, cancer treatment, and chronic health conditions).34

Primary Outcomes

Feasibility

Enrollment and retention were tracked, including the number of eligible survivors enrolled, the number of sessions completed, and the percentage of follow-up surveys completed.

Acceptability

The follow-up survey assessed satisfaction with navigation services including communication with the navigator, sessions (scheduling, length, and number), the handbook, Zoom, visuals, and program quality (excellent, good, average, poor, and very poor). Participants rated likelihood of recommending the program to other survivors of childhood cancer (definitely would, probably would, neutral, probably would not, and definitely would not recommend program) and program helpfulness (1-10; 1 = least helpful and 10 = most helpful).

Preliminary Efficacy

HIL (primary outcome) was measured by using 16 items denoting confidence in understanding insurance terms (eg, deductible, copayments, and coinsurance) and performing health insurance–related activities (eg, figuring out copayments, finding an in-network doctor), with a 4-category Likert scale ranging from 16 to 64 (higher scores denoting lower literacy).22,35

Familiarity with health insurance–related policy was assessed by using a four-point scale of familiarity (very, somewhat, not too, and not at all familiar) for the ACA, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Family Medical Leave Act, Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines.

Awareness of key ACA provisions included six questions regarding protections such as no annual/lifetime limits, dependent coverage through age 26 years, preventive care coverage, appeals, preexisting conditions coverage, and subsidies for premiums with participants reporting yes, no, and don’t know, coded as yes versus no/don’t know.

Health insurance coverage satisfaction was measured by using a one-item rating (excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor).

Behavioral financial hardship was a composite of nine items regarding cost-worries leading to skipping medical care (ie, putting off/postponing preventive care, dental care, or vision care, and skipping a test or treatment recommended by a provider).

Psychological financial hardship was a composite of six questions about worries paying medical care, insurance expenses, and lack of insurance coverage for certain services.36

Statistical Analyses

We examined sociodemographic, medical history, insurance, and financial-related characteristics at baseline between the HINT intervention and the EUC arm using chi-square and t-tests. We report descriptive statistics on intervention feasibility (percent of survivors enrolled/sessions completed/follow-up surveys completed), acceptability (satisfaction and perceived support), and efficacy (eg, HIL and ACA familiarity). We performed chi-square and t-tests to compare end-of-treatment changes in preliminary efficacy outcomes between the two groups; Cohen’s d was used to estimate effect size differences. Multivariable linear regressions were conducted to examine changes in the preliminary efficacy outcomes between the two intervention groups, adjusting for age, sex, and Medicaid expansion state.

RESULTS

Enrollment and Feasibility

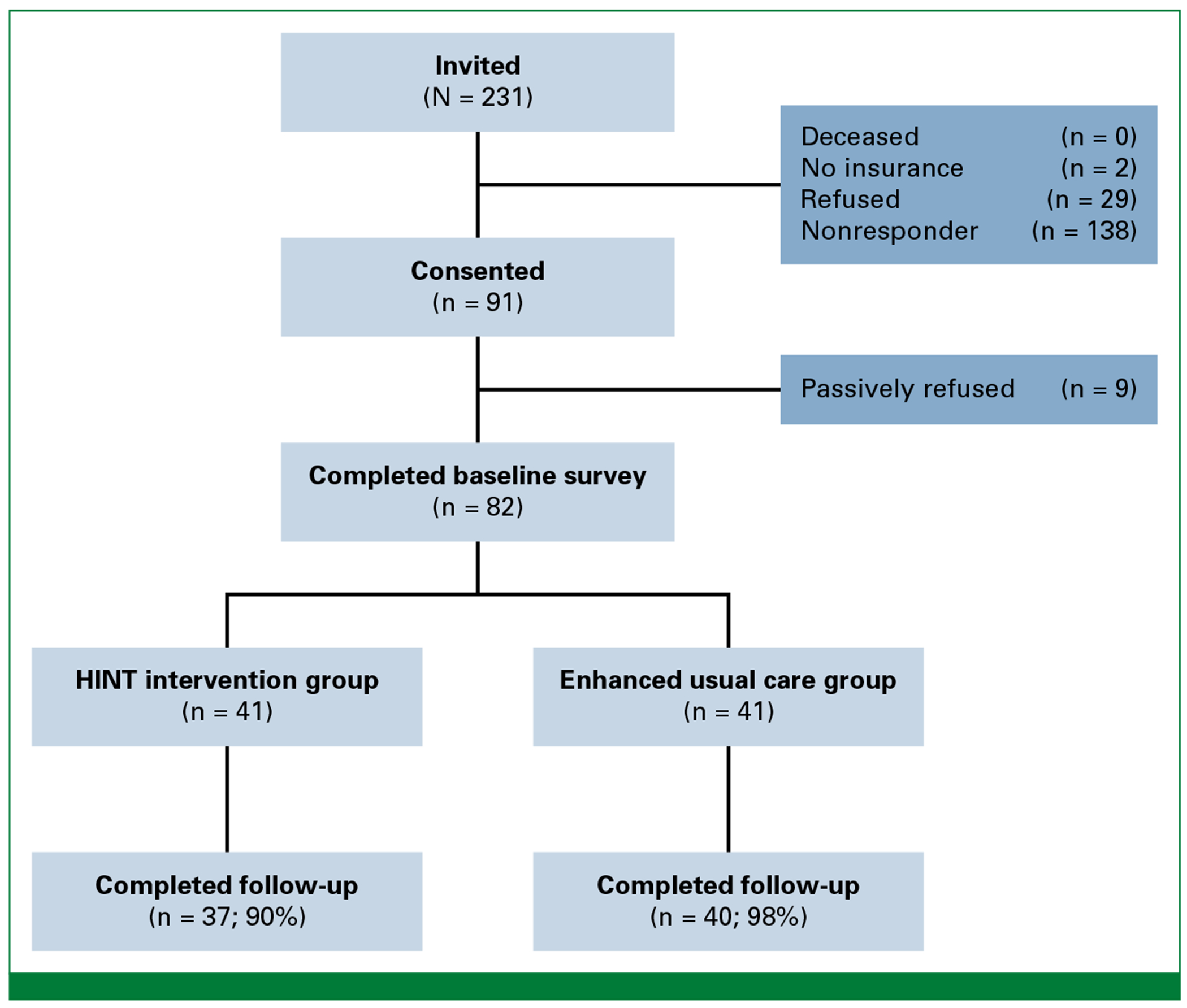

We invited 231 CCSS patients to participate in the HINT program (Fig 1). Among those invited, 91 consented and 82 participants completed the baseline survey (90.1%) over a 10-month recruitment period. Over half (53.7%) were female, and 86.6% were White, 4.9% Hispanic, 4.9% Asian American Pacific Islander, 6.1% Black, and 52.4% were younger than 40 years. Most participants were employed full-time or part-time at baseline (75.0%), had insurance through an employer (75.6%), and were their own policy holder (73.2%). Less than half (42.6%) of participants were from a non-expansion state. Participants rated their insurance as very good (27.5%) or good (37.5%). The intervention and control arms did not differ on any baseline characteristics (Tables 1 and 2). Most (93.9%) completed the 5-month follow-up survey.

FIG 1.

CONSORT diagram. HINT, health insurance navigation tools.

TABLE 1.

Childhood Cancer Survivor Baseline Diagnosis, Treatment, and Sociodemographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Intervention (n = 41) | Control (n = 41) |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Sex assigned at birth | ||

| Male | 21 (51.2) | 17 (41.5) |

| Female | 20 (48.8) | 24 (58.5) |

| Current age, years | ||

| 26-39 | 22 (54.7) | 21 (51.2) |

| 40-54 | 14 (34.2) | 15 (36.6) |

| 55-66 | 5 (12.2) | 5 (12.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 2 (4.9) |

| Black | 3 (7.3) | 2 (4.9) |

| Hispanic | 2 (4.9) | 2 (4.9) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 36 (87.8) | 35 (85.4) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | ||

| 0-4 | 12 (29.3) | 13 (31.7) |

| 5-9 | 11 (26.8) | 11 (26.8) |

| 10-14 | 11 (26.8) | 8 (19.5) |

| 15-20 | 7 (17.1) | 9 (22.0) |

| Original cancer diagnosis | ||

| Leukemia | 12 (29.3) | 11 (26.8) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 5 (12.2) | 2 (4.9) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 5 (12.2) | 5 (12.2) |

| Wilms tumor | 5 (12.2) | 4 (9.8) |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 1 (2.4) | 4 (9.8) |

| Bone cancer | 6 (14.6) | 7 (17.1) |

| Central nervous system tumor | 5 (12.2) | 7 (17.1) |

| Neuroblastoma | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.4) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 27 (65.9) | 27 (65.9) |

| Never married | 9 (22.0) | 10 (24.4) |

| Divorce/separated | 5 (12.2) | 4 (9.8) |

| Education | ||

| High school diploma/GEDb or less | 3 (7.3) | 1 (2.4) |

| Some college or technical school | 11 (26.8) | 11 (26.8) |

| College graduate or higher | 27 (65.9) | 29 (70.7) |

| Health and cancer treatment information | ||

| Any severe/life-threatening chronic condition (grade 3 or 4) | ||

| Yes | 16 (39.0) | 16 (39.0) |

| No | 25 (61.0) | 25 (61.0) |

| History of subsequent malignant neoplasm | ||

| Yes | 2 (4.9) | 3 (7.3) |

| No | 39 (95.1) | 38 (92.7) |

| Recurrence of primary cancer | ||

| Yes | 5 (12.2) | 4 (9.8) |

| No | 36 (87.8) | 37 (90.2) |

| Radiation therapy for treatment of primary cancera | ||

| Yes | 17 (47.2) | 15 (36.6) |

| No | 19 (52.8) | 26 (63.4) |

| Chemotherapy for treatment of primary cancera | ||

| Yes | 31 (86.1) | 34 (82.9) |

| No | 5 (13.9) | 7 (17.1) |

| Surgery for treatment of primary cancera | ||

| Yes | 24 (66.7) | 33 (80.5) |

| No | 12 (33.3) | 8 (19.5) |

| Anthracycline treatmenta | ||

| Yes | 22 (61.1) | 24 (58.4) |

| No | 14 (38.9) | 17 (41.5) |

| Alkylating agent treatmenta | ||

| Yes | 20 (55.6) | 25 (61.0) |

| No | 15 (41.7) | 16 (39.0) |

| Unknown | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) |

Missing data.

General education development.

TABLE 2.

Participant Baseline Financial and Health Insurance Characteristics

| Characteristic | Intervention (n = 41) | Control (n = 41) |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Employmenta | ||

| Full-time or part-time | 28 (70.0) | 32 (80.0) |

| Caring for home or family | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.0) |

| Unable to work (illness or disability) | 5 (12.5) | 1 (2.5) |

| Retired, student, other | 3 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) |

| Unemployed | 3 (7.5) | 2 (5.0) |

| Household income (USD)a | ||

| <$50,000 | 9 (23.1) | 8 (20.0) |

| $50,000-$99,999 | 16 (41.0) | 13 (32.5) |

| $100,000-$149,999 | 9 (23.1) | 6 (15.0) |

| ≥$150,000 | 5 (12.8) | 13 (32.5) |

| Health insurance coverageb | ||

| Employer-sponsored | 30 (73.2) | 32 (78.1) |

| Individual insurance | 1 (2.4) | 5 (12.2) |

| Medicare | 3 (7.3) | 1 (2.4) |

| Medicaid/state public insurance | 5 (12.2) | 2 (4.9) |

| Medicaid expansion state | ||

| Yes | 23 (56.1) | 24 (58.5) |

| No | 18 (43.9) | 17 (41.5) |

| Primary insurance policy holder | ||

| You (self) | 32 (78.1) | 28 (68.3) |

| Spouse/partner | 7 (17.1) | 12 (29.3) |

| Parent | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.4) |

| How many people (including you) are covered on your current health insurance plan? | ||

| 1 | 17 (41.5) | 16 (39.0) |

| 2 | 6 (14.6) | 5 (12.2) |

| 3 | 8 (19.5) | 8 (19.5) |

| 4 or more | 10 (24.4) | 12 (29.3) |

| Overall, how would you rate your current health insurance coverage? | ||

| Excellent | 5 (12.5) | 9 (22.5) |

| Very good | 8 (20.0) | 14 (35.0) |

| Good | 17 (42.5) | 13 (32.5) |

| Fair/poor | 10 (25.0) | 4 (10.0) |

| Don’t know | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) |

| Do you currently have insurance that covers most/some/none of medical care? | ||

| Most | 30 (73.2) | 37 (90.2) |

| Some | 8 (19.5) | 4 (10.0) |

| None | 3 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) |

Abbreviation: USD, US dollars.

Missing data.

Participants could select more than one response.

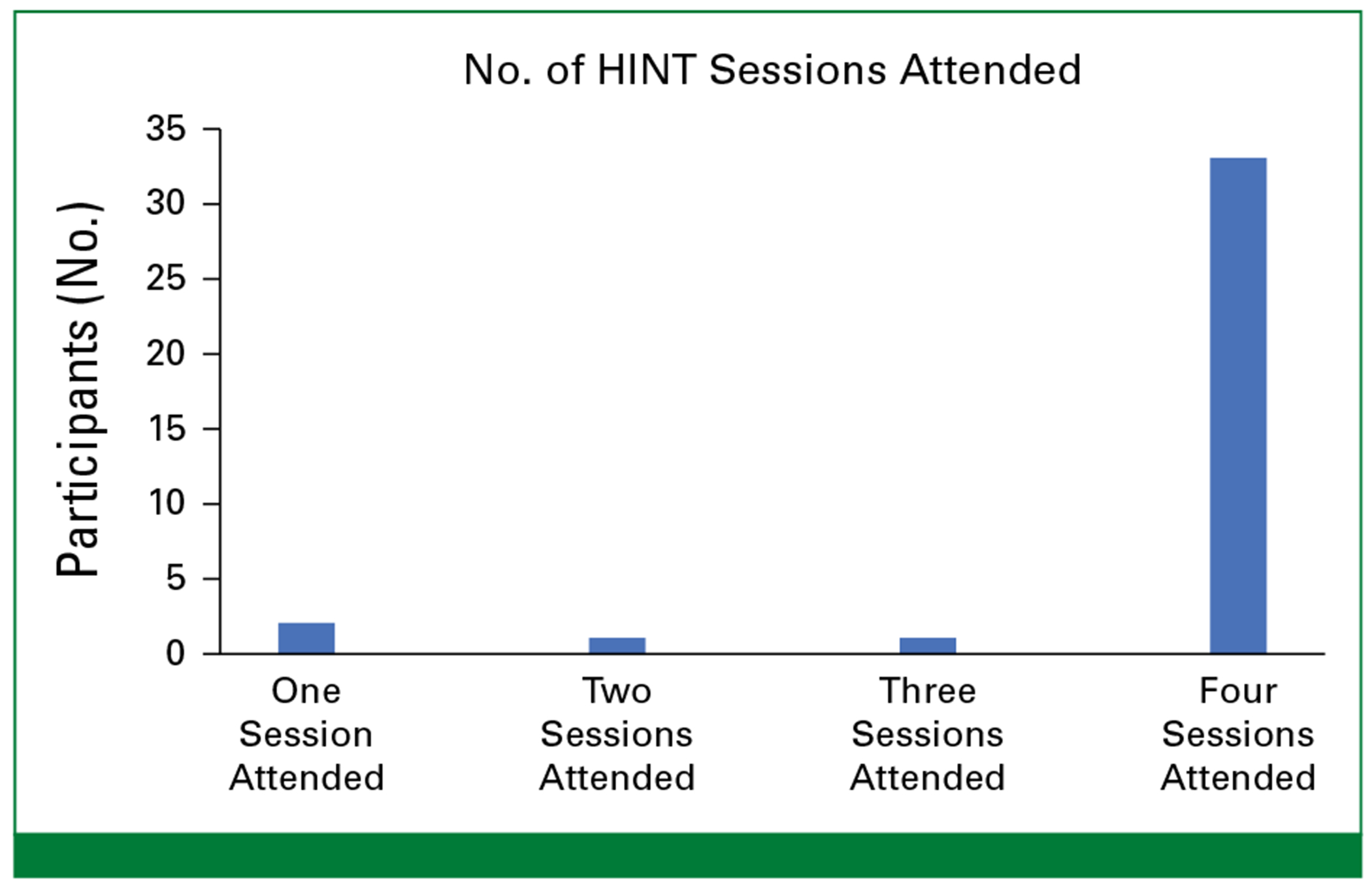

Acceptability

Of intervention participants, 80.5% completed all four sessions (Fig 2). Sessions were an average of 42.4 (standard deviation [SD] = 8.8) minutes. Satisfaction with the program was high, averaging 37.2 (range, 8-40, with higher scores better; Table 3). Most rated the program as meeting their needs (8.9 average of 10), and 65.7% would definitely recommend the program to other survivors. Intervention participants rated excellent for communication with the navigator (82.9%), Zoom format (77.1%), scheduling convenience (77.1%), overall program quality (74.3%), length of sessions (71.4%), number of sessions (68.6%), and booklet (60.0%).

FIG 2.

Health insurance navigation tools session attendance (n = 41).

TABLE 3.

Health Insurance Navigation Tools Intervention Feasibility and Acceptability (n = 41)

| Feasibility and Acceptability | n = 41 |

|---|---|

| Treatment engagement, mean (SD) | |

| Average session length (minutes) | 42.4 (8.8) |

| Acceptability, mean (SD) | |

| Program met needs for information on health insurancea | 8.9 (1.2) |

| Would you recommend the program?b,c No. (%) | |

| Definitely would recommend | 23 (65.7) |

| Probably would recommend | 7 (20.0) |

| Neutral | 5 (14.3) |

| Program quality (No., % rated excellent)d | |

| Communication with navigator | 29 (82.9) |

| Zoom format | 27 (77.1) |

| Ability to schedule sessions at convenient time | 27 (77.1) |

| Overall program quality | 26 (74.3) |

| Length of sessions | 25 (71.4) |

| No. of sessions | 24 (68.6) |

| Visuals including PowerPoints | 24 (68.6) |

| Booklet | 21 (60.0) |

Needs met range = 1-10; 1 = least helpful program you could imagine, and 10 = most helpful program you could imagine; higher is better.

n = 35.

Recommend = definitely would, probably would, neutral, probably would not, and definitely would not recommend program.

Program quality = excellent, good, average, poor, and very poor.

Baseline Health Literacy, Familiarity With Health Insurance–Related Policies and ACA Provisions, and Financial Burden.

The majority were confident about insurance terms including premium, deductible, and in-network provider (Appendix Tables A2–A4). Confidence in knowledge of health insurance activities was lower; 43.9% intervention and 46.3% control participants were confident in how to file an appeal; 58.5% intervention and 46.3% control participants were confident in knowledge of how to calculate a cost of an in-network service, and 43.9% intervention and 46.3% control participants were confident in knowledge of how to file an appeal.

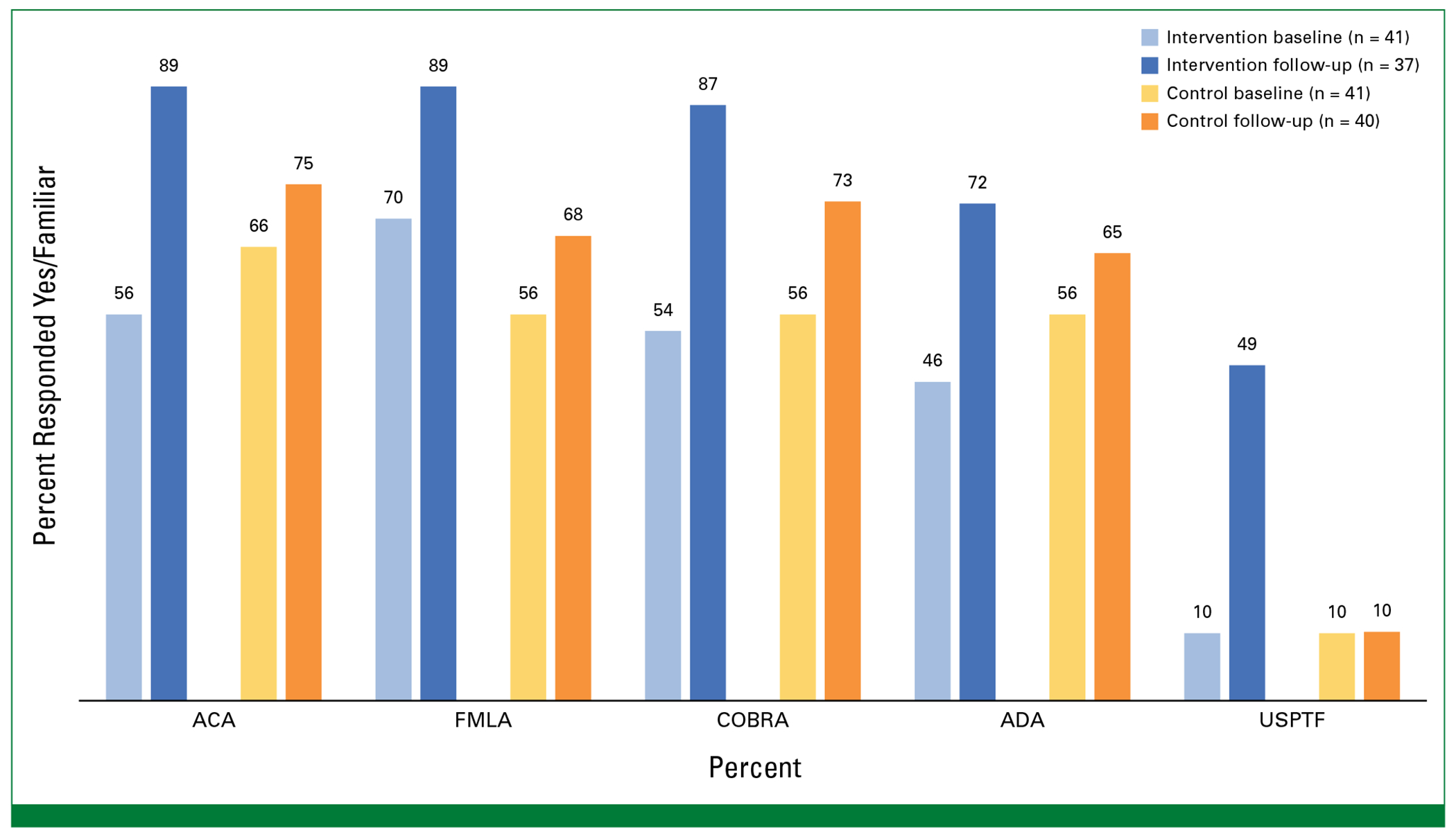

HIL scores were low to moderate (mean 28.5, SD = 9.0; range, 16-60). In terms of health insurance–related policies, 61.0% were familiar with the ACA and 51.2% with the ADA; only 9.8% were familiar with USPSTF recommendations. In terms of knowledge of ACA provisions, only 46.3% of intervention and 52.5% of control participants knew that there was required coverage for preventive care, and only 19.5% of intervention and 29.3% of control participants knew that there were no annual or lifetime limits. 25.0% of intervention and 20.0% of control participants endorsed worry that they would not be able to pay for medical bills, and 37.5% of intervention and 17.1% of control participants endorsed worry that they would need some health care services that were not covered.

Preliminary Efficacy

HINT significantly improved HIL, familiarity with health insurance reform, knowledge of ACA provisions, psychological financial hardship, and health insurance satisfaction compared with EUC at 5-month follow-up; effect sizes ranged from 0.55 to 0.94 (Table 4). HIL improved on average −9.1 for intervention participants compared with −1.8 for EUC (multivariable adjusted model difference −7.6 [95% CI, −4.11 to −11.1]; P < .001). HINT participants reported improvements in knowledge of coinsurance, copayment, and covered services; confidence improved in reported knowledge of health insurance activities, including figuring out how to file an appeal, if a service is covered by plan, what counts as preventive care services, and which medications are covered (Appendix Table A2). ACA provisions knowledge scores significantly improved from 1.2 ([95% CI, 0.4 to 2.0]; P < .001; Appendix Table A3). Intervention participants also reported significantly higher satisfaction with their insurance at follow-up compared with EUC (−0.57 [95% CI, −0.5 to −1.1]; P = .03). Psychological hardship (Appendix Table A4) significantly improved for intervention versus EUC participants (−0.9 [95% CI −1.6 to −0.3]; P < .006), but behavioral financial hardship did not. Familiarity with the ACA improved from 56.1% to 89.2% for intervention participants and from 65.9% to 75.0% for control participants. Familiarity with the USPSTF improved from 9.8% to 48.7% for intervention participants and remained similar at 9.8% to 10.0% for control participants (Fig 3).

TABLE 4.

Primary and Secondary Outcome Comparisons Between Health Insurance Navigation Tools Treatment Arms

| Primary and Secondary Outcomes | Intervention | Control | Effect Size (95% CI)b | Multivariable Regressionc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (n = 41) | FU (n = 37) | Changea | BL (n = 41) | FU (n = 40) | Changea | Coefficient and 95% CI | P | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Health insurance literacyd | 29.2 (9.7) | 19.8 (5.1) | −9.1 (7.6) | 27.8 (8.3) | 26.1 (7.7) | −1.8 (7.9) | 0.94 (0.47 to 1.41) | −7.6 (−4.1 to −11.1) | <.001 |

| Satisfaction with health insurance coveragee | 2.8 (1.0) | 2.2 (1.1) | −0.7 (1.2) | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.3 (1.1) | −0.1 (1.0) | 0.55 (0.09 to 0.99) | −0.57 (−0.5 to −1.1) | .03 |

| Psychological financial hardshipf | 1.7 (2.2) | 1.2 (1.9) | −0.7 (1.6) | 1.0 (1.6) | 1.2 (1.9) | 0.2 (1.2) | 0.64 (0.18 to 1.10) | −0.9 (−1.6 to −0.3) | <.006 |

| Behavioral financial hardshipg | 1.8 (2.5) | 1.3 (2.2) | −0.7 (1.7) | 1.8 (2.3) | 1.3 (2.0) | −0.5 (2.2) | 0.10 (−0.33 to 0.55) | −0.2 (−1.0 to 0.7) | .73 |

| ACA provisionsh | 3.2 (1.7) | 5.1 (1.2) | −1.7 (1.7) | 3.6 (1.4) | 4.0 (1.6) | −0.5 (1.6) | 0.73 (0.26 to 1.19) | −1.2 (0.4 to 2.0) | .003 |

Abbreviations: ACA, Affordable Care Act; BL, baseline; FU, follow-up.

Mean change calculated among sample with complete data.

Effect sizes calculated from Cohen’s d statistic.

Multivariable regression adjusted for sex, age, and Medicaid expansion status.

Health insurance literacy range = 16-64; lower scores are better.

Satisfaction with current health insurance coverage rating = 1 = excellent, to 5 = poor; lower scores are better.

Psychological financial hardship range = 0-6; lower scores are better.

Behavioral financial hardship range = 0-8; lower scores are better.

ACA provisions range = 0-6; higher scores are better.

FIG 3.

Familiarity with health care legislation. ACA, Affordable Care Act; ADA, Americans with Disabilities Act; FMLA, Family Medical Leave Act; COBRA, Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act; USPTF, US Preventive Task Force.

Participant Perspectives on Feasibility and Acceptability: Postintervention Exit Interviews

Twenty-four intervention participants (58.5% participation rate) completed exit interviews regarding their experiences and perceived acceptability of HINT. They expressed satisfaction with the length of sessions and the individual, virtual format of delivery and enjoyed HINT’s structure, convenience, relevance, and personal touch. Participants felt the personal connection with the navigator helped to increase their comfort with discussing sensitive topics. One participant noted, “You feel like you know a little bit more about who you’re talking to. And I think it probably helps you be able to open up more to someone.”

Participants were grateful for HINT, identifying that it filled gaps in health insurance knowledge. Specifically, many felt HINT helped them identify resources and solutions for common insurance-related obstacles, even when they perceived themselves as knowledgeable before participating. Most concluded that they did not need to make changes to their current insurance plans; indeed, many remarked how they were pleased with what their current plan had to offer. Yet, HINT led them to delve into their current insurance plans, to reflect on what they have and what is missing. HINT gave participants a sense of confidence in their own skills to engage in conversations surrounding health care coverage. Several identified a sense of empowerment and insight regarding approaches for engaging in conversations about their health care. One participant remarked, “I feel more comfortable with terms if I did have to call the insurance company, then I feel like I could at least hang in the conversation with them when they start using all these terms.”

DISCUSSION

Access to and utilization of quality health insurance is critical for survivors of childhood cancer who are at high risk for morbidity, mortality, and financial burden. We developed and pilot-tested a health insurance navigation intervention, HINT, which, to our knowledge, is the first intervention developed to target childhood cancer survivors’ HIL with the goal of ameliorating financial burden and improving health care access. Our findings demonstrated promising feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy, compared with EUC. The virtual program, with individual support, demonstrated high participation and engagement; HINT engagement rates were higher than previously reported programs targeting insurance and financial need among patients with cancer.26

HINT significantly increased survivors’ HIL, which is a crucial skill to understanding and navigating complex health systems. It is notable that the HINT intervention content was aligned with participants’ baseline reported gaps in knowledge and confidence, such as understanding the definitions of coinsurance and out-of-pocket maximums and low confidence in understanding what services were covered by their plan, in- and out-of-network costs, and filing an appeal. These were the reported aspects of HIL that improved. Overall, our findings of increased familiarity with the ACA as well as knowledge of ACA provisions suggest that survivors who participated in the HINT intervention may be better positioned to leverage these protections. These findings are particularly important as our earlier work found that childhood cancer survivors reported very low awareness of the ACA and other health insurance–related policies.15

HINT improved survivors’ satisfaction with their health insurance coverage. Previous research found that survivors reported being satisfied with their coverage, even if there were clear indications of underinsurance,13 as they often felt fortunate to just have coverage. However, exit interview results indicated that survivors’ improved perceptions of their coverage were not because of simply settling for having coverage but rather attributed to how HINT helped them better understand their benefits and, additionally, how to use their plan benefits.

The HINT program also significantly decreased participants’ psychological financial hardship, such as worries about losing insurance coverage and related health care costs. Patient-reported psychological financial hardship or the stress surrounding health care–related out-of-pocket costs may be affected by the nontransparent nature of health services billing and health insurance coverage structures.25,37–39 Our findings suggest that educating cancer survivors about their health insurance, including how out-of-pocket costs work, may remove some of the mystery surrounding their medical bills and thus lower their stress levels.

Although conducted within a national cohort with promising study findings, study limitations should be acknowledged. Our results assess the feasibility of a study protocol and not a practice implementation. Notably, behavioral financial hardship—such as not skipping medical care because of costs—did not improve at the 5-month follow-up; this is perhaps because of a need for longer-term follow-up to show an effect. Second, there was limited racial and ethnic minority representation, and the efficacy of HINT in underrepresented survivors needs to be validated in future trials. Finally, participants were relatively well educated, but despite this, the significance and need for navigation was underscored by low HIL scores.

In summary, HINT program feasibility, engagement, and satisfaction was high. Findings indicated that HINT improved HIL, knowledge of ACA provisions, worries about financial issues, and satisfaction with insurance coverage. Together, these findings demonstrate that HINT is a promising program that engages long-term survivors of childhood cancer in learning about health insurance and how to navigate health care. Future inquiry should assess the long-term effectiveness of HIL interventions at altering health service utilization (eg, ameliorating behavioral financial hardship and material financial hardship).18

Supplementary Material

CONTEXT.

Key Objective

Childhood cancer survivors are at increased risk for underinsurance and health insurance–related financial burden. This pilot randomized controlled trial sought to investigate the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the health insurance navigation tools (HINT) intervention designed to aid childhood cancer survivors navigate their health insurance.

Knowledge Generated

Among a population of adult survivors of childhood cancer, we found that baseline health literacy was low and many lacked knowledge of Affordable Care Act (ACA) provisions. The HINT intervention, consisting of four biweekly virtual navigation sessions and an educational book, resulted in improved health literacy, knowledge, or ACA provisions, reduced measures of psychological financial burden, and improved satisfaction with health insurance compared with the educational booklet alone (enhanced standard care). The intervention was found to be feasible and acceptable, supporting further evaluation in larger trials.

Relevance

Adult survivors of childhood cancer can face substantial health related financial burdens. This study demonstrates the potential of a scalable and acceptable educational intervention that demonstrated preliminary efficacy across important metric, demonstrating a need for further testing of implementation and impact.

SUPPORT

Supported by the American Cancer Society (132688-RSGI-18-135-01-CPHPS) and National Cancer Institute (CA55727, G.T.A., Principal Investigator). Support to St Jude Children’s Research Hospital also provided by the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant (CA21765, C. Roberts, Principal Investigator) and the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the ASCO Annual Meeting in Chicago, IL, June 3-7, 2022: A health insurance navigation intervention tools (HINT) for survivors of childhood cancer: randomized pilot trial results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.

AUTHORS– DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at DOI https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.23.00680.

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to http://www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Elyse R. Park

Honoraria: UpToDate

Anne C. Kirchhoff

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Medtronic

Karen Donelan

Employment: Mass General Brigham

Tracy Battaglia

Employment: Boston University, Yale University

Research Funding: American Cancer Society, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (Inst), NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (Inst)

Alison A. Galbraith

Employment: Harvard Pilgrim Health Care/Point32 Health

Research Funding: Harvard Pilgrim Health Care

Karen A. Kuhlthau

Employment: Massachusetts General Hospital

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Johnson & Johnson, Abbott Laboratory, Amgen, Cardinal Health, CVS, Edwards Lifesciences, Lilly, Healthcare Services Group, Hologic, LabCorp, Medtronic, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Organon, Pfizer, Stryker

Research Funding: Merck

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with this article at DOI https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.23.00680.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman DL, Whitton J, Leisenring W, et al. : Subsequent neoplasms in 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: The childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:1083–1095, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reulen RC, Frobisher C, Winter DL, et al. : Long-term risks of subsequent primary neoplasms among survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 305:2311–2319, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen JH, Möller T, Anderson H, et al. : Lifelong cancer incidence in 47 697 patients treated for childhood cancer in the Nordic countries. J Natl Cancer Inst 101:806–813, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulrooney DA, Yeazel MW, Kawashima T, et al. : Cardiac outcomes in a cohort of adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: Retrospective analysis of the childhood cancer survivor study cohort. BMJ 339:b4606, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipshultz SE, Adams MJ, Colan SD, et al. : Long-term cardiovascular toxicity in children, adolescents, and young adults who receive cancer therapy: Pathophysiology, course, monitoring, management, prevention, and research directions: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 128:1927–1995, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Pal HJ, van Dalen EC, van Delden E, et al. : High risk of symptomatic cardiac events in childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 30:1429–1437, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Chen Y, et al. : Modifiable risk factors and major cardiac events among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 31:3673–3680, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green DM, Kawashima T, Stovall M, et al. : Fertility of male survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 28:332–339, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadan-Lottick NS, Zeltzer LK, Liu Q, et al. : Neurocognitive functioning in adult survivors of childhood non-central nervous system cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:881–893, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krull KR, Brinkman TM, Li C, et al. : Neurocognitive outcomes decades after treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the St Jude lifetime cohort study. J Clin Oncol 31:4407–4415, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ness KK, Krull KR, Jones KE, et al. : Physiologic frailty as a sign of accelerated aging among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the St Jude lifetime cohort study. J Clin Oncol 31:4496–4503, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park ER, Li FP, Liu Y, et al. : Health insurance coverage in survivors of childhood cancer: The childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 23:9187–9197, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park ER, Kirchhoff AC, Zallen JP, et al. : Childhood Cancer Survivor Study participants’ perceptions and knowledge of health insurance coverage: Implications for the Affordable Care Act. J Cancer Surviv 6:251–259, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchhoff AC, Kuhlthau K, Pajolek H, et al. : Employer-sponsored health insurance coverage limitations: Results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Support Care Cancer 21:377–383, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park ER, Kirchhoff AC, Perez GK, et al. : Childhood Cancer Survivor Study participants’ perceptions and understanding of the Affordable Care Act. J Clin Oncol 33:764–772, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nipp RD, Kirchhoff AC, Fair D, et al. : Financial burden in survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 35:3474–3481, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhlthau KA, Nipp RD, Shui A, et al. : Health insurance coverage, care accessibility and affordability for adult survivors of childhood cancer: A cross-sectional study of a nationally representative database. J Cancer Surviv 10:964–971, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khera N, Zhang N, Hilal T, et al. : Association of health insurance literacy with financial hardship in patients with cancer. JAMA Netw Open 5:e2223141, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagi BF, Luster JE, Scherer AM, et al. : Association of health insurance literacy with health care utilization: A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 37:375–389, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao J, Han X, Zheng Z, et al. : Is health insurance literacy associated with financial hardship among cancer survivors? Findings from a national sample in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr 3:pkz061, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin LT, Parker RM: Insurance expansion and health literacy. JAMA 306:874–875, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hero JO, Sinaiko AD, Kingsdale J, et al. : Decision-making experiences of consumers choosing individual-market health insurance plans. Health Aff 38:464–472, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters AR, Mann K, Warner EL, et al. : “I thought there would be more I understood”: Health insurance literacy among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 30:4457–4464, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edward JS, Rayens MK, Zheng X, et al. : The association of health insurance literacy and numeracy with financial toxicity and hardships among colorectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 29:5673–5680, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tipirneni R, Politi MC, Kullgren JT, et al. : Association between health insurance literacy and avoidance of health care services owing to cost. JAMA Netw Open 1:e184796, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith GL, Banegas MP, Acquati C, et al. : Navigating financial toxicity in patients with cancer: A multidisciplinary management approach. CA Cancer J Clin 72:437–453, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institute on Aging: NIH Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development. https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/dbsr/nih-stage-model-behavioral-intervention-development [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warner EL, Park ER, Stroup A, et al. : Childhood cancer survivors’ familiarity with and opinions of the patient protection and affordable care Act. JCO Oncol Pract 9:246–250, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirchhoff AC, Montenegro RE, Warner EL, et al. : Childhood cancer survivors’ primary care and follow-up experiences. Support Care Cancer 22:1629–1635, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirchhoff AC, Nipp R, Warner EL, et al. : “Job Lock” among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA Oncol 4:707–711, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park ER, Kirchhoff AC, Nipp RD, et al. : Assessing health insurance coverage characteristics and impact on health care cost, worry, and access: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA Intern Med 177:1855–1858, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nipp RD, Shui AM, Perez GK, et al. : Patterns in health care access and affordability among cancer survivors during implementation of the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Oncol 4:791–797, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, et al. : Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: An evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med 22:267–284, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.St Jude CCSS: Public Access Data Tables. https://ccss.stjude.org/public-access-data/public-access-data-tables.html [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinaiko AD, Hayes M, Kingsdale J, et al. : Understanding consumer experiences and insurance outcomes following plan disenrollment in the nongroup insurance market. Med Care Res Rev 79:36–45, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fair D, Park ER, Nipp RD, et al. : Material, behavioral, and psychological financial hardship among survivors of childhood cancer in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 127:3214–3222,2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan RO, Teal CR, Hasche JC, et al. : Does poorer familiarity with Medicare translate into worse access to health care? J Am Geriatr Soc 56:2053–2060, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piette JD, Heisler M.: The relationship between older adults’ knowledge of their drug coverage and medication cost problems: Knowledge of prescription drug coverage. J Am Geriatr Soc 54:91–96, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benedetti NJ, Fung V, Reed M, et al. : Office visit copayments: Patient knowledge, response, and communication with providers. Med Care 46:403–409, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levy H, Meltzer D. What Do We Really Know About Whether Health. https://web.stanford.edu/~jay/health_class/Readings/Lecture02/levy_meltzer.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with this article at DOI https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.23.00680.