Abstract

Background

The primary genetic risk factor for heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension is the presence of monoallelic mutations in the BMPR2 gene. The incomplete penetrance of BMPR2 mutations implies that additional triggers are necessary for pulmonary arterial hypertension occurrence. Pulmonary artery stenosis directly raises pulmonary artery pressure, and the redirection of blood flow to unobstructed arteries leads to endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling. We hypothesized that right pulmonary artery occlusion (RPAO) triggers pulmonary hypertension (PH) in rats with Bmpr2 mutations.

Methods and Results

Male and female rats with a 71 bp monoallelic deletion in exon 1 of Bmpr2 and their wild‐type siblings underwent acute and chronic RPAO. They were subjected to full high‐fidelity hemodynamic characterization. We also examined how chronic RPAO can mimic the pulmonary gene expression pattern associated with installed PH in unobstructed territories. RPAO induced precapillary PH in male and female rats, both acutely and chronically. Bmpr2 mutant and male rats manifested more severe PH compared with their counterparts. Although wild‐type rats adapted to RPAO, Bmpr2 mutant rats experienced heightened mortality. RPAO induced a decline in cardiac contractility index, particularly pronounced in male Bmpr2 rats. Chronic RPAO resulted in elevated pulmonary IL‐6 (interleukin‐6) expression and decreased Gdf2 expression (corrected P value<0.05 and log2 fold change>1). In this context, male rats expressed higher pulmonary levels of endothelin‐1 and IL‐6 than females.

Conclusions

Our novel 2‐hit rat model presents a promising avenue to explore the adaptation of the right ventricle and pulmonary vasculature to PH, shedding light on pertinent sex‐ and gene‐related effects.

Keywords: bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2, pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary artery occlusion, pulmonary hypertension

Subject Categories: Vascular Disease, Animal Models of Human Disease, Hemodynamics

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BMPR2

bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2

- CO

cardiac output

- IC

index of contractility

- LAP

left atrial pressure

- mPAP

mean pulmonary artery pressure

- MWT

medial wall thickness

- PAH

pulmonary arterial hypertension.

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- PP

pulse pressure

- RPA

right pulmonary artery

- RPAO

right pulmonary artery occlusion.

- WT

wild‐type

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

The induction of right pulmonary artery occlusion (RPAO) in rats results in patent precapillary pulmonary hypertension.

RPAO triggers more severe pulmonary hypertension in Bmpr2 mutant and male rats compared with their wild‐type and female counterparts.

Bmpr2 mutant rats exhibit poorer adaptation to RPAO, characterized by increased post‐RPAO mortality, reduced right ventricle contractility index, and diminished right ventricle hypertrophy alongside elevated pulmonary vascular resistance.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

RPAO‐induced pulmonary hypertension establishes a new, nontoxic, sex‐dependent model for precapillary pulmonary hypertension, unveiling a distinct phenotype in genetically predisposed rats.

Experimentally, Bmpr2 mutation impairs the right ventricular adaptation to increased afterload, echoing the poorer prognosis of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension with the mutation.

Dysregulated pulmonary expression of genes associated with the endothelin, prostacyclin, and BMP (bone morphogenetic protein) pathways in the unobstructed territories underscores the pathophysiological and preclinical relevance of this innovative rat model of PH.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a devastating condition characterized by progressive narrowing of the pulmonary blood vessels, leading to dysfunction of the right ventricle (RV) and death. 1 In cases of heritable PAH, approximately 70% of cases, as well as 15% to 40% of cases classified as idiopathic PAH, are associated with inherited autosomal dominant mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2) gene, making BMPR2 loss of function the primary genetic risk factor for PAH development. However, the fact that only about 20% of BMPR2 carriers actually develop PAH suggests that additional factors are necessary for the disease to manifest. 2 Interestingly, mice and rats with a single functional copy of the Bmpr2 gene (Bmpr2 +/−) exhibit no or minimal elevation of pulmonary artery pressures under normal conditions, 3 , 4 similar to most BMPR2 carriers. However, exposure to specific triggers such as serotonin, low‐grade inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide, or recombinant Ad5LO (adenovirus expressing 5‐lipoxygenase) is sufficient to cause pulmonary hypertension (PH) in these animals. 5 , 6 Furthermore, Bmpr2 mutations exacerbate late‐stage pulmonary vasculopathy and decrease survival rates in rats exposed to experimental PH induced by monocrotaline or hypoxia. In humans, triggers such as pregnancy 7 or exposure to amphetamines or amphetamine‐like drugs 8 , 9 may also lead to PAH in individuals with BMPR2 pathogenic variants.

Sexual dimorphism also plays a role in the development of PAH, with female individuals being approximately 4 times more likely to develop the condition than male individuals, depending on the underlying disease pathology. 10 Notably, in the context of BMPR2 loss of function, this sexual dimorphism is particularly pronounced, with a penetrance of approximately 42% in female individuals and 14% in male individuals. 11 Clinically, patients with PAH with BMPR2 pathogenic variants tend to experience early onset of the disease, have a poor prognosis, exhibit reduced vascular reactivity, have impaired right ventricular function, and show resistance to PAH‐specific therapies. 12

Pulmonary artery (PA) stenosis, whether congenital or acquired, can affect different levels of the pulmonary arterial tree, including the main, branched, lobar, segmental, or distal areas. 13 Significant stenosis of the lumen size in PA stenosis directly raises PA pressure, and the redirection of blood flow to unobstructed arteries can lead to endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling. 14 Consequently, this results in an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and the development of PH. 15

Based on this clinical observation, we hypothesized that right pulmonary artery occlusion (RPAO) could act as a trigger for the development of experimental PH in rats. Total occlusion is achieved by ligating the RPA. This method ensures a consistent reduction of approximately two thirds of the total pulmonary vasculature, independent of the initial size, sex, and genetic background of the animals. Eventually, we evaluated the effect of the loss of Bmpr2 on the RV and pulmonary vascular remodeling, resulting in differences in disease outcomes, hemodynamics, RV function, sex response, and the expression patterns of genes associated with PH in the lungs.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Statement for Animal Experiments

The rats were housed at the animal facility of the Faculty of Pharmacy of Chatenay‐Malabry, which holds a license from the French Ministry of Agriculture. All experiments were conducted in compliance with European Union regulations. The rats were maintained under stress‐free conditions, that is, unlimited food and water access, regular light cycles (12/12 hours), no forced exercise, and generally pathogen free. All animals received human care. The use of animals for scientific purposes in this study received approval from the French Minister of Higher Education, Research, and Innovation (APAFiS‐22 771). Throughout the experiment, ethical end points were established, including monitoring for difficulties in feeding and watering, distressing symptoms (such as dyspnea and self‐injurious behavior), persistent external abnormalities (such as diarrhea and bleeding) without signs of improvement, and rapid weight loss >20% within a short period of time. Every effort was made to minimize animal pain during the study.

Animal Model

Bmpr2 mutant rats were established using the zinc finger nuclease method. 3 We developed a strain with a monoallelic deletion of 71 bp in the first exon of Bmpr2 (Δ71 rats). As homozygous Bmpr2 mutations are embryonic lethal, breeding of Bmpr2 +/Δ71 rat was carried out by crossing Bmpr2 +/Δ71 rats with wild‐type (WT) rats (Sprague‐Dawley). Genotyping of the offspring was performed after weaning. The mutated Bmpr2 allele in the rats was identified by a polymerase chain reaction using primer pairs 5′‐AAGCTAGGTCCTCGCATCTG‐3′ and 5′‐TAGGGACGGGAAACTACACG‐3′. 3 The amplification conditions were 1 cycle of 5 seconds at 95 °C and 2 seconds at 62 °C; 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 95 °C, 30 seconds at 60 °C and 30 seconds at 72 °C; and 3 minutes at 72 °C.

Surgical Procedure

Rats were anesthetized with an Isoflurane Rodent Anesthesia system (Minerve, Esternay, France). They were placed in supine position, a tracheostomy was performed, and rats were then intubated through the tracheostomy with a 14G catheter allowing for controlled ventilation during the whole procedure (tidal volume: 5 mL, respiratory frequency: 70/minutes, inspiratory reserve volume/expiratory reserve volume: 1.2, small animal ventilator Model R415). Under general anesthesia a sternotomy was performed, and the precaval lumbar space was dissected, then the right PA was ligated (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Surgical procedure.

A, Anatomical view of rats, both before and after the induction of right pulmonary artery occlusion, in an open‐chest setting. B, The process of conducting right heart catheterization in rats during the initial acute experiment. In (C), the same procedure is depicted, with the addition of 2 Millar catheters directly inserted into the left atrium and the main pulmonary artery.

Experimental Design

Two acute and 1 chronic experiments were conducted on male and female Sprague‐Dawley rats, aged 6 months, both Bmpr2 mutant and WT, to delve into the effects of RPAO. The initial acute experiment sought to assess the impact of RPAO in rats, specifically focusing on 18 males (8 WT and 10 Bmpr2) and 14 females (8 WT and 6 Bmpr2 mutants). The second acute experiment aimed to validate the precapillary component by directly measuring left atrial pressure (LAP) and the mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) using high‐fidelity catheters. This allowed for a precise evaluation of PVR and involved 15 males (7 WT and 8 Bmpr2) and 14 females (8 WT and 6 Bmpr2).

The chronic experiment aimed to decipher whether chronic RPAO induced installed PH in both WT and Bmpr2 mutant rats, while also considering the influence of sex. In this study, 10 males (5 WT, 5 Bmpr2) and 10 females (5 WT and 5 Bmpr2) underwent RPAO. Postsurgery, the chest was closed layer by layer, and the tracheostomy was sutured. Subsequently, all rats were awakened, stabilized, and were ultimately euthanized 4 weeks after the surgery to analyze the lasting impacts of RPAO. All measurements were analyzed blindly.

Hemodynamic Measurements

During acute experiments, we performed hemodynamic assessments on ventilated animals throughout the procedure, up to 30 minutes after ligation. The hemodynamic values reported are extracted from stabilized tracings recorded just before ligation, the “before RPAO” time point, and 30 minutes after ligation, the “after RPAO” time point. The delta form of the results corresponds to the following formula: the value of the parameter after RPAO minus the value of the parameter before RPAO. This mitigates the variability introduced by the variable baseline value.

In chronic experiments, we performed hemodynamic assessments on ventilated animals 4 weeks after ligation or sham procedures. The hemodynamic values reported are extracted from stabilized tracings recorded after catheters implantation.

In the first acute experiment, a fluid‐filled catheter was placed, through the jugular vein, inside the RV, and a high‐fidelity Millar catheter was placed in the RV through the fluid‐filled catheter to measure the right ventricle systolic pressure (RVSP), then a thermocouple microprobe was inserted the common carotid artery to reach the ascending aorta in order to measure the cardiac output (CO) using the thermodilution technique (Figure 1B). Measured hemodynamic parameters including RVSP, RV diastolic pressure, the index of contractility (IC) (Max dP/dt divided by the RV pressure (P) at the time of Max dP/dt), and total pulmonary resistance were estimated based on the formula RVSP/CO.

In the second acute experiment, as well as in the chronic experiment a Millar catheter was added and placed in the pulmonary artery trunk, and another was placed directly in the left atrium, in order to measure the mean LAP (Figure 1C). Measured hemodynamic parameters included RVSP, RV diastolic pressure, the IC, mPAP, systolic PAP, diastolic PAP, mean LAP, and CO. PVR was calculated based on the formula (mPAP‐mean LAP/CO). Stroke volume (SV) was calculated based on the formula (CO/heart rate [HR]), pulse pressure (PP) was calculated based on the formula (systolic PAP − diastolic PAP), PA stiffness was calculated based on the formula (PP/SV).

Echocardiographic Measurement

Rats were evaluated by transthoracic echocardiography (Vivid E9, GE Healthcare) by using a high‐frequency transducer. Evaluation was performed before the surgery under general anesthesia and spontaneous breathing to confirm the absence of PH, and before hemodynamic measurements in the chronic RPAO experiment to evaluate the severity of PH. RV evaluation included tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, and PA acceleration time.

Evaluation of Right Ventricle Hypertrophy and Collection of Tissue

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (2 L/min O2/3% isoflurane; Minerve, Esternay, France). Following exsanguination, the upper left lung was distended by infusion of formalin via the trachea and then embedded in paraffin. The noninflated lower left lung was snap‐frozen in liquid nitrogen and used for protein and RNA quantification. For Fulton's index of RV hypertrophy, the ratio of the right ventricular weight to left ventricular plus septal weight (RV/left ventricle+septal weight) was calculated.

We also calculated the left lung weight/right lung weight ratio. This ratio is calculated post‐end point, at the time of animal euthanasia for organ sampling. The left lung is susceptible to overflow‐induced edema after RPAO, leading to an increase in its wet weight. In contrast, the right lung is not exposed to overflow or overflow‐induced edema. Thus, its weight is expected to remain relatively unchanged. In cases of overflow‐induced edema in the left lung, the ratio increases.

Pulmonary Artery Morphometric Analysis

Hematoxylin‐eosin saffron staining was carried out on 5 μm thick paraffin‐embedded lung sections using standard procedures. The assessment focused on pulmonary arteries ranging from 50 to 100 to <50 μm in diameter, with arterial wall thickness measured at ×400 magnification. In each rat, a minimum of 10 randomly selected circular or oval‐shaped blood vessels were measured. The percentage medial wall thickness (MWT, in %) of the arteries was computed using the formula: MWT = [(external diameter − internal diameter)/external diameter] × 100. The internal diameter was defined as the luminal diameter of the vessel, and the external diameter was determined as the total diameter of the vessel.

Quantitative Real‐Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Array

Total RNA was extracted from frozen rat lung tissue using RNEasy Mini kit 74106 obtained from Qiagen with DNAse digestion. RNA quantity and quality were assessed using the Nanodrop‐ND‐1000 (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). One microgram of total RNA was reverse‐transcripted using a QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA; cat. no. 205311). Gene expression of endothelin, nitric oxide, and prostacyclin signaling pathways and markers associated with PAH were determined using a SignArray96 (Reference numbers: PZ65A1R1‐F, Anygenes, Paris, France) (Table S1), on a StepOne + Real‐Time Polymerase Chain Reaction System (Life Technologies). Polymerase chain reaction amplification was conducted following cycling conditions: preincubation at 95 °C for 10 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 10 seconds at 95 °C, 20 seconds at 60 °C, and 1 seconds at 72 °C. The mRNA expression for each gene was normalized using the housekeeping gene transcripts of actin beta, whose expression was more stable across experimental groups than other housekeeping genes (Table S2 and Figure 2).

Figure 2. Average expression stability values (M statistic) of remaining control genes estimated by the geNorm algorithm.

The lower the M factor, the more stable is the housekeeping gene indicated in the x axis.

Statistical Analysis

For all descriptive analyses, measurements have been summarized by their mean, SD (with an asterisk indicating if the normality of the distribution is not assumed thanks to the Shapiro–Wilk test), and their median (range) [first and third quartiles]. If the normality of the distribution is verified in all comparison groups, the Student or Welch t test is used—regardless of homoscedasticity. Otherwise, the U Mann–Whitney test was preferred. Post‐RPAO versus pre‐RPAO data were summarized with their distribution's statistics of the calculated difference (delta) and compared with paired t test (if the normality was assumed) or a nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. Categorical variables (sex, gene, sham versus ligated) are described by their counts and percentages.

For the acute RPAO study, a 1‐way t test on measurements deltas was used. The impact of sex and genes on delta measurements was estimated through linear regression models, adding an interaction parameter if type III ANOVA had previously detected a significant interaction between these 2 factors. For the chronic RPAO study, the impact of sex, genes, and group (sham versus ligated) was also estimated in the same multivariate linear model, including order 1 interaction terms, if any had been detected between 2 factors. Boxplots were generated to illustrate the results.

Before starting real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis, the average M statistic was calculated for the different housekeeping genes thanks to the geNorm method (Table S2 and Figure 2). To visualize the genes ΔCT (the difference in threshold cycle (CT) values between the target gene and the housekeeping reference gene) according to sex, gene, and group, a Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction 3 was performed and illustrated on its 2 first dimensions. Then, for each gene, the impact of these 3 factors on ΔCT was estimated through multivariate linear regression models (with no interaction). P values were corrected with the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure on each factor. Finally, genes' expressions were graphically illustrated thanks to volcano plot.

The level of significance was set at a 5% alpha‐risk, and consequently, 95% CIs were calculated. All the statistical analyses, tables, and graphs were made with R (v4.1.2), using ‘ggplot2,’ ‘ctrlGene,’ ‘pcr,’ and ‘umap’ libraries.

Results

Acute RPAO Induces Acute PH

Tables S3 and S4 contain comprehensive data for all measured parameters, along with their respective modelizations.

We analyzed the effects of the acute RPAO in male and female rats, in the WT or Bmpr2 mutant background. At the same age (between 4 and 5 months), males weighed more than females (610.85±12.62 versus 328.21±9.88 g respectively, P<0.001) and were larger (28.05±0.34 versus 24.96±0.41 cm respectively, P<0.001). There was no influence of the genetic status on the weight and height of the animals (Tables S3 and S4). To mitigate the impact of weight and height on the analyzed parameters, we opted to present them in delta form (post RPAO–pre RPAO).

Acute RPAO was associated with a significant rise in RVSP (mean difference [95% CI]: +19.82±6.17 mm Hg, P<0.001) and a fall in CO (−30.57±17.29 mL/min, P<0.001), in cardiac index (−1.12±0.71 mL/min per cm, P<0.001), in SV (−0.15±0.08 mL, P<0.001), in the IC (−19.31±17.23 s−1), and in mean systemic arterial pressure (−20.79±18.43 mm Hg, P<0.001). At the same time, there was a significant increase in RVSP/CO (0.42±0.22 mm Hg/min per mL, P<0.001) (Table 1; Tables S3 and S4).

Table 1.

Hemodynamic Parameters Before and After RPAO Across All Groups

| Variable | Pre‐RPAO | Post‐RPAO | Delta variable | N | P value of the delta | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RVSP, mm Hg | 32.41±3.51 | 52.23±5.78* | 19.82 (6.17) | 46 | <0.001 | Paired t test |

| CO, mL/min | 106.84±14.49* | 76.60±17.97 | −30.24 (19.4) | 46 | <0.001 | Paired t test |

| Cardiac index, mL/min per cm | 110.75 (87.6; 167.5) [103.05–125.68] | 89.5 (69.3; 145.6) [84.72–104.85] | −17 (−69.7; 11) [−25.57 to −11.95] | 46 | <0.001 | Wilcoxon paired signed rank test |

| SV, mL | 0.41±0.08 | 0.26±0.07 | −0.15 (0.08) | 46 | <0.001 | Paired t test |

| Index of contractility, s−1 | 3.94±0.44* | 2.82±0.62 | −1.12 (0.71) | 46 | <0.001 | Paired t test |

| Mean arterial pressure, mm Hg | 101.73±14.23 | 80.93±20.58 | −20.79 (18.43) | 32 | <0.001 | Paired t test |

| RVSP/CO, mm Hg.min per mL | 0.31 (0.21; 0.4) [0.28–0.34] | 0.72 (0.42; 1.21) [0.54–0.88] | 0.38 (0.1; 0.84) [0.24–0.58] | 46 | <0.001 | Wilcoxon paired signed rank test |

| Mean pulmonary arterial pressure, mm Hg | 24.37±3.70 | 37.37±4.64 | 12.99 (4.71) | 14 | <0.001 | Paired t test |

| PP, mm Hg | 12.90±4.05 | 23.63±6.64 | 10.73 (7.7) | 14 | <0.001 | Paired t test |

| Pulmonary artery stiffness (PP/SV), mm Hg/mL | 31.16±10.97 | 91.25±41.70* | 60.09 (41.03) | 14 | <0.001 | Paired t test |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance, mm Hg.min per mL | 0.21 (0.12; 0.27) [0.17–0.22] | 0.42 (0.31; 0.94) [0.33–0.52] | 0.24 (0.12; 0.73) [0.16–0.3] | 14 | <0.001 | Wilcoxon paired signed rank test |

| Left atrial pressure, mm Hg | 3.80±1.19 | 3.44±1.64 | −0.36 (1.67) | 14 | 0.430 | Paired t test |

| Right ventricular end‐diastolic pressure, mm Hg | 2.78±1.69 | 3.50±2.03 | 0.71 (1.94) | 46 | 0.016 | Paired t test |

The hemodynamic effect of acute RPAO in rats is presented in delta form (post RPAO–pre RPAO), in order to mitigate the effect of weight and size. CO indicates cardiac output; PP, pulse pressure; RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; and SV, stroke volume. £: mean ± SD, $: median (min;max) [Q1–Q3].

Distribution not Gaussian.

Then, we directly measured the PAP and the LAP with high‐fidelity catheters to determine whether acute PH was of precapillary or postcapillary origin in a second series of experiments.

We found that the mPAP was increased (+12.99±4.71 mm Hg, P<0.001), as well as the PP (+10.73±7.70 mm Hg, P < 0.001), the PA stiffness (PP/SV) (+60.09±41.03 mm Hg/mL, P<0.001), and the PVR (+0.27±0.16 mm Hg/min per mL, P<0.001). At the same time, there was no change in the LAP, signaling the precapillary origin of the acute RPAO‐induced PH (Table 1; Tables S3 and S4). Right ventricular end‐diastolic pressure remained consistently below the defined threshold indicative of RV dysfunction 3 (Table 1).

Bmpr2 Mutant Rats Have More Severe PH After Acute RPAO

Bmpr2 mutant rats had a significant majorization in the delta of RVSP (+7.7 [4.97–10.44] mm Hg, P<0.001) and RVSP/CO (+0.25 [0.15–0.35] mm Hg/min per mL, P<0.001) compared with WT. This was associated with a significant further decrease in the delta of CO (−24.3 [−31.34 to −17.26] mL/min, P<0.001) and SV (−0.07 [−0.1 to −0.03] mL, P<0.001). Males exhibited a notable decrease in SV compared with females (−0.05 [−0.009 to −0.01] mL, P=0.013). The IC was lower in male Bmpr2 mutant rats as compared with female Bmpr2 mutant rats (−18.64 [−35.89 to −1.39] s−1, P=0.040) (Figure 3 and Table 2).

Figure 3. Hemodynamic effect of acute RPAO.

The hemodynamic effects of acute RPAO in rats are presented in delta form (post RPAO–pre RPAO), in order to mitigate the effect of weight and size. A, Right ventricular systolic pressure. B, Cardiac output. C, Stroke volume. D, Index of contractility. E, RVSP/CO ratio. F, Left lung weight/right lung weight ratio. Descriptive statistics and modelizations are available in Table 2 and Tables S3 and S4. A–E: Female (F), WT N=8, Bmpr2 N=6; male (M), WT N=15, Bmpr2 N=17. F: Female (F), WT N=8, Bmpr2 N=6; male (M), WT N=7, Bmpr2 N=7. CO indicates cardiac output; IC, index of contractility; LLW/RLW, left lung weight/right lung weight ratio; RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; SV, stroke volume; and WT, wild type.

Table 2.

Modelization of the Acute Hemodynamic Effects of RPAO Depicted in Figure 3

| Variable | Baseline level | Class level | Delta RVSP, mm Hg | Delta CO, mL/min | Delta SV, mL | Delta IC, s−1 | Delta RVSP/CO, mm Hg/min per mL | LLW/RLW | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | |||

| Sex |

F N=14 |

M N=32a |

−1.24 [−4.21 to 1.73] | 0.418 | −3.93 [−11.57 to 3.72] | 0.320 | −0.05 [−0.009 to −0.01] | 0.013 | 9.01 [−2.69 to 20.7] | 0.139 | 0.03 [−0.08 to 0.14] | 0.593 | 0.00 [−0.07 to 0.08] | 0.923 |

| Gene |

WT N=23b |

Bmpr2 N=23c |

7.7 [4.97 to 10.44] | <0.001 | −24.3 [−31.34 to −17.26] | <0.001 | −0.07 [−0.1 to −0.03] | <0.001 | −7.27 [−21.69 to 7.16] | 0.329 | 0.25 [0.15 to 0.35] | <0.001 | 0.31 [0.23 to 0.38] | <0.001 |

| Sex:Gene |

M, Bmpr2 N=17 |

−18.64 [−35.89 to −1.39] | 0.040 | |||||||||||

The hemodynamic effect of acute RPAO in rats is presented in delta form (post RPAO–pre RPAO), in order to mitigate the effect of weight and size. CO indicates cardiac output; IC, index of contractility; LLW/RLW, ratio of left lung weight to right lung weight; Mean diff., mean difference; RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; and SV, stroke volume. RVSP, CO, SV, IC, RVSP/CO: female (F), WT N=8, Bmpr2 N=6; male (M), WT N=15, Bmpr2 N=17. LLW/RLW: female (F), WT N=8, Bmpr2 N=6; male (M), WT N=7, Bmpr2 N=7, a N=14, b N=15, c N=13. Specifically for the LLW/RLW parameter, the number of rats per group differs from all other parameters and is denoted by a, b, and c.

The RPAO resulted in the swelling of the left lung (subjected to overflow), whereas the right lung (no longer perfused) remained unaffected. To standardize and quantify this observation across rats, we calculated the ratio of left lung weight to right lung weight. The ratio was significantly higher in Bmpr2 mutant rats (Figure 3 and Table 2). Because we exclusively used Bmpr2 +/− animals and WT without spontaneous PH, and considering that the RV cannot hypertrophy within such a brief period, the Fulton index, a marker of RV hypertrophy, remains equivalent across all groups (Tables S3 and S4).

In the second series of experiments aimed at distinguishing between the precapillary and postcapillary origins of PH, we exclusively employed male subjects. This decision was based on the absence of a discernible sex‐related effect of acute RPAO, except for SV (which decreased in males but not in females) (Figure 3, Table 2). In this series, the delta of PVR, PP, PA stiffness, and mPAP was more pronounced in Bmpr2 mutant rats compared with WT rats (0.22 [0.09–0.34] mm Hg/min per mL, P=0.005; +9.91 [3.66–16.15] mm Hg, P=0.009; +59.33 [29.76–88.9] mm Hg/mL, P=0.002; +7.03 [3.79–10.27] mm Hg, P=0.001, respectively) (Figure 4, Table 3, and Tables S3 and S4). The mean LAP was not affected by the genetic status of the animals (Figure 5 and Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 4. Acute assessment of the effect of RPAO in WT and Bmpr2 rats.

Delta of (A) PVR, (B) PP, (C) PA stiffness, and (D) mPAP. Descriptive statistics and modelizations are available in Table 3, Tables S3 and S4. Only male rats were used in this analysis. WT N=7, Bmpr2 N=7. mPAP indicates mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PA, pulmonary artery; PP, pulse pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; and WT, wild type.

Table 3.

Modelization of the Acute Hemodynamic Effects of RPAO Depicted in Figure 4

| Variable | Baseline level | Class level | Delta PVR, mm Hg/min mL | Delta PP, mm Hg | Delta PA stiffness, mm Hg/mL | Delta mPAP, mm Hg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | |||

| Gene |

WT N=7 |

Bmpr2 N=7 |

0.22 [0.09–0.34] | 0.005 | 9.91 [3.66–16.15] | 0.009 | 59.33 [29.76–88.9] | 0.002 | 7.03 [3.79–10.27] | 0.001 |

The hemodynamic effect of acute RPAO in rats is presented in delta form (post RPA–pre RPAO), in order to mitigate the effect of weight and size. Mean diff. indicates mean difference; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PA stiffness, pulmonary artery stiffness; PP, pulse pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; and RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion.

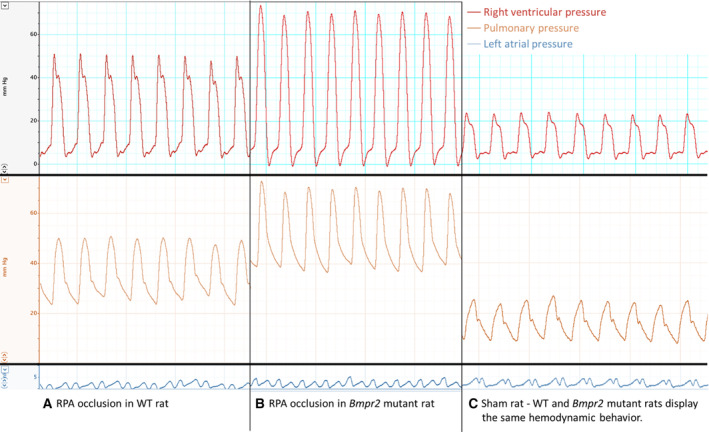

Figure 5. Representative pressure tracings.

From top to bottom, representative pressure tracings of RVP, PAP, and LAP (A–C). Representative pressure tracings of RVP, PAP, and LAP in WT rats after RPA occlusion (A), in Bmpr2 mutant rats after RPA occlusion (B), and in sham‐operated rats (C). LAP indicates left atrial pressure; PAP, pulmonary arterial pressure; RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; RVP, right ventricular pressure; and WT, wild type.

Chronic RPAO Induces Installed PH, With Gene and Sex Effects

Tables S5 and S6 contain comprehensive data for all measured parameters, along with their respective modelizations.

In this series of experiments, rats were analyzed 4 weeks postsurgery to investigate the long‐term effects of RPAO.

Because the groups were not paired in those experiments, we present absolute values of the parameters, in males and females, with WT or Bmpr2 +/− genetic background.

The RVSP was higher in males compared with females (+5.17 [0.82–9.53] mm Hg, P=0.026), and in animals with chronic RPAO (+11.33 [6.12–16.54] mm Hg, P<0.001). Among rats with chronic RPAO, both males and Bmpr2 +/− rats exhibited a significant additional increase in RVSP (+14.56 [8.49–20.64] mm Hg, P<0.001 and +13.35 [7.27–19.42] mm Hg, P<0.001 respectively) (Figure 6A, Table 4, and Figure 5).

Figure 6. Hemodynamic effect of chronic RPAO.

Absolute values of the parameters, in males and females, with WT or Bmpr2 +/− genetic background are presented. A, Right ventricular systolic pressure. B, Mean pulmonary artery pressure. C, Cardiac output. D, RVSP/CO ratio. E, Index of contractility. F, Stroke volume. G, Pulmonary vascular resistance. H, Pulse pressure. I, PA stiffness. J, Heart rate. Descriptive statistics and modelizations are available in Table 4, and Tables S5 and S6. Sham: Female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=4; RPAO: female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5. CO indicates cardiac output; HR, heart rate; IC, index of contractility; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PA, pulmonary artery; PP, pulse pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; SV, stroke volume; and WT, wild type.

Table 4.

Modelization of the Chronic Hemodynamic Effects of RPAO Depicted in Figure 6

| Variable | Baseline level | Class level | RVSP, mm Hg | mPAP, mm Hg | CO, mL | RVSP/CO, mm Hg/min per mL | IC, s−1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | |||

| Sex |

F N=20 |

M N=19 |

5.17 [0.82 to 9.53] | 0.026 | 4.53 [1.01 to 8.05] | 0.017 | 32.46 [27.27 to 37.65] | <0.001 | 0 [−0.03 to 0.03] | 0.991 | 39.06 [3.61 to 74.5] | 0.038 |

| Gene |

WT N=20 |

Bmpr2 N=19 |

−0.31 [−4.67 to 4.05] | 0.890 | 2.07 [−1.46 to 5.59] | 0.258 | −15.79 [−20.98 to −10.6] | <0.001 | 0.02 [−0.02 to 0.07] | 0.319 | 0.3 [−35.14 to 35.74] | 0.987 |

| Experiment (Exp) |

Sham N=19 |

RPAO N=20 |

11.33 [6.12 to 16.54] | <0.001 | 17.71 [13.5 to 21.93] | <0.001 | −41.69 [−46.88 to −36.5] | <0.001 | 0.26 [0.21 to 0.3] | <0.001 | −21.37 [−46.79 to 4.05] | 0.109 |

| Sex:Exp |

M, RPAO N=10 |

14.56 [8.49 to 20.64] | <0.001 | 7.93 [3.02 to 12.84] | 0.003 | |||||||

| Gene:Exp | Bmpr2, RPAO N=10 | 13.35 [7.27 to 19.42] | <0.001 | 6.18 [1.27 to 11.09] | 0.019 | 0.19 [0.13 to 0.25] | <0.001 | |||||

| Sex:Gene |

M, Bmpr2 N=10 |

−55.81 [−106.65 to −4.97] | 0.039 | |||||||||

| Variable | Baseline level | Class level | SV, mL | PVR, mm Hg/min per mL | PP, mm Hg | PA stiffness, mm Hg/mL | HR, bpm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | |||

| Sex |

F N=20 |

M N=19 |

0.13 [0.1 to 0.16] | <0.001 | 0.01 [−0.02 to 0.04] | 0.485 | −0.48 [−5.68 to 4.71] | 0.856 | 2.61 [−7.36 to 12.58] | 0.611 | −11.41 [−27.95 to 5.13] | 0.186 |

| Gene |

WT N=20 |

Bmpr2 N=19 |

−0.03 [−0.06 to 0] | 0.057 | 0.02 [−0.02 to 0.06] | 0.399 | −0.02 [−5.22 to 5.18] | 0.994 | 3.21 [−11.09 to 17.5] | 0.663 | −6.43 [−22.98 to 10.11] | 0.451 |

|

Experiment (Exp) |

Sham N=19 |

RPAO N=10 |

−0.23 [−0.26 to −0.2] | <0.001 | 0.23 [0.19 to 0.27] | <0.001 | 4.48 [−1.73 to 10.7] | 0.167 | 49.56 [35.65 to 63.46] | <0.001 | 46.69 [26.9 to 66.48] | <0.001 |

| Gene:Exp | Bmpr2, RPAO N=10 | 0.12 [0.06 to 0.19] | <0.001 | 11.43 [4.18 to 18.68] | 0.004 | 32.89 [12.94 to 52.83] | 0.003 | −29.1 [−52.17 to −6.04] | 0.019 | |||

| Sex:Exp |

M, RPAO N=10 |

13.67 [6.42 to 20.92] | <0.001 | 25.04 [1.97 to 48.11] | 0.041 | |||||||

CO indicates cardiac output; HR, heart rate; IC, index of contractility; Mean diff., mean difference; mPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PA stiffness, pulmonary artery stiffness (PP/SV); PP, pulse pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; SV, stroke volume; and WT, wild type. Sham: female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=4; RPAO: female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5.

The mPAP was higher in males compared with females (+4.53 [1.01–8.05] mm Hg, P=0.017) and in animals with chronic RPAO (+17.71 [13.5–21.93] mm Hg, P<0.001). Among rats with chronic RPAO, both males and Bmpr2 +/− rats exhibited a significant additional increase in mPAP (+7.93 [3.02–12.84] mm Hg, P=0.003 and +6.18 [1.27–11.09] mm Hg, P=0.019 respectively) (Figure 6B and Table 4, and Figure 5). At the same time, there was no change in the LAP (Tables S5 and S6 and Figure 5).

The CO was higher in males compared with females (+32.46 [27.27–37.65] mL/min, P<0.001) and decreased in animals with chronic RPAO (−41.69 [−46.88 to −36.5] mL/min, P<0.001) or Bmpr2 +/− genetic background (−15.79 [−20.98 to −10.6] mL, P<0.01) (Figure 6C and Table 4).

RVSP/CO was higher in rats with chronic RPAO compared with shams (+0.26 [0.21–0.3] mm Hg/min per mL, P<0.001). Bmpr2 mutant animals with RPAO had an additional increase in RVSP/CO compared with WT (+0.19 [0.13–0.25] mm Hg/min per mL, P<0.001) (Figure 6D and Table 4).

The IC was higher in males compared with females (+39.06 [3.61–74.5] s−1, P=0.038) but lower in male Bmpr2 mutants compared with their female counterparts (−55.81 [−106.65 to −4.97] s−1, P=0.039). The IC was decreased in animals with chronic RPAO (−21.37 [−46.79 to 4.05] s−1, P=0.109) (Figure 6E and Table 4).

The SV was higher in males compared with females (+0.13 [0.1–0.16] mL, P<0.001) and decreased in animals with chronic RPAO (−0.23 [−0.26 to −0.2] mL, P<0.001) (Figure 6F and Table 4).

Consistently, PVR paralleled RVSP/CO variations. PVR was higher in rats with chronic RPAO compared with shams (+0.23 [0.19–0.27] mm Hg/min per mL, P<0.001). Bmpr2 +/− animals with RPAO had an additional increase in PVR compared with WT (+0.12 [0.06–0.19] mm Hg/min per mL, P<0.001) (Figure 6G and Table 4).

PP was increased in male and Bmpr2 +/− rats with chronic RPAO (+13.67 [6.42–20.92] mm Hg, P<0.001 and 11.43 [4.18–18.68] mm Hg, P<0.004) compared with female and WT rats with chronic RPAO respectively (Figure 6H and Table 4). PA stiffness was higher in rats with chronic RPAO compared with shams (+49.56 [35.65–63.46] mm Hg/min per mL, P<0.001). Bmpr2 +/− animals with RPAO had an additional increase in PA stiffness compared with WT (+32.89 [12.94–52.83] mm Hg/min per mL, P=0.003) (Figure 6I and Table 4).

HR was higher in rats with chronic RPAO compared with shams (+46.69 [26.9–66.48] bpm, P<0.001) with an additional effect in males compared with females (+25.04 [1.97–48.11] bpm, P=0.041), whereas Bmpr2 +/− animals had a lower HR increase compared with WT (−29.1 [−52.17 to −6.04] bpm, P=0.019) (Figure 6J and Table 4).

With regard to echocardiographic parameters, the PA acceleration time inversely correlates with PVR, and the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion is a useful measure of RV function. The PA acceleration time was lower in males compared with females −2.66 [−5.06 to −0.27] ms, P=0.036 and lower in Bmpr2 mutants as compared with WT (−2.63 [−5.03 to −0.24] ms, P=0.038). Chronic RPAO was associated with a drop in PA acceleration time compared with sham (−12.47 [−14.87 to −10.08] ms, P<0.001) (Figure 7 and Table 5). The tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion was decreased in rats with chronic RPAO compared with shams (−1.13 [−1.44 to −0.82] mm, P<0.001) with an additional effect in Bmpr2 rats compared with WT (−0.66 [−1.11 to −0.21] mm, P=0.006) (Figure 7 and Table 5).

Figure 7. Echocardiographic assessment in WT, Bmpr2 rats with and without RPAO.

A, Pulmonary acceleration time. B, Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion. Descriptive statistics and modelizations are available in Table 5, Tables S5 and S6. Sham: Female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=4; RPAO: female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5. PAAT, pulmonary acceleration time; RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; and WT, wild type.

Table 5.

Modelization of the Chronic Effects of RPAO on Echocardiographic Parameters Depicted in Figure 7

| Variable | Baseline level | Class level | PAAT, ms | TAPSE, mm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | |||

| Sex |

F N=20 |

M N=19 |

−2.66 [−5.06 to −0.27] | 0.036 | −0.07 [−0.29 to 0.15] | 0.544 |

| Gene |

WT N=20 |

Bmpr2 N=19 |

−2.63 [−5.03 to −0.24] | 0.038 | −0.1 [−0.42 to 0.22] | 0.546 |

| Experiment (Exp) |

Sham N=19 |

RPAO N=20 |

−12.47 [−14.87 to −10.08] | <0.001 | −1.13 [−1.44 to −0.82] | <0.001 |

| Gene:Exp | Bmpr2, RPAO N=10 | −0.66 [−1.11 to −0.21] | 0.006 | |||

Mean diff. indicates mean difference; PAAT, pulmonary acceleration time; RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; and TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion. SHAM: female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=4; RPAO: female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5.

Finally, we analyzed morphometric parameters of RV and pulmonary vascular remodeling. The RV thickness was higher in males compared with females (+301.26 [134.26–468.26] μm, P<0.001) and increased after RPAO (+350.78 [151.04–550.52] μm, P=0.002). Among rats with chronic RPAO, males exhibited a significant additional increase in RV thickness (+347.53 [114.66–580.4] μm, P=0.006), whereas Bmpr2 +/− animals had a lower RV thickness increase compared with WT (−277.86 [−510.73 to −44.99] μm, P=0.026) (Figure 8A and Table 6). Even after normalizing RV thickness for the height of the animals, our results remained consistent (Figure 8B and Table 6, and Tables S5 and S6).

Figure 8. Gene, sex, and RPAO effect on right ventricle and pulmonary vascular remodeling in the nonobstructed territories.

A, RV thickness. B, RV thickness normalized relative to the size of the animal. C, Fulton index. D, Medial wall thickness of pulmonary arteries with an external diameter <50μm. E, MWT of PA with an external diameter between 50 and 100 μm. F, Pictures of distal pulmonary microvessels of male rats, illustrating the increase in MWT caused by RPAO and the interaction between RPAO and Bmpr2 mutation. Scale bar: 50μm. Descriptive statistics and modelizations are available in Table 6, Tables S5 and S6. Sham: Female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=4; RPAO: Female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5. LV, left ventricular; MWT, medial wall thickness; PA, pulmonary artery; RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; RV, right ventricular; and WT, wild type.

Table 6.

Modelization of the Chronic Effects of RPAO on Morphological Parameters Depicted in Figure 8

| Variable | Baseline level | Class level | RV thickness, μm | RV thickness/height, μm/cm | Fulton index (RV/[LV+septal weight]) | MWT (%) (PA diameter <50 μm) | MWT (%) (PA diameter between 50 and 100 μm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | Mean diff. [95% CI] | P value | |||

| Sex |

F N=20 |

M N=19 |

301.26 [134.26 to 468.26] | 0.001 | 8.48 [2.28 to 14.69] | 0.011 | 0.01 [−0.01 to 0.04] | 0.309 | 2.9 [0.9 to 4.9] | 0.007 | 0 [−0.02 to 0.03] | 0.832 |

| Gene |

WT N=20 |

Bmpr2 N=19 |

12.01 [−154.99 to 179.01] | 0.889 | 0.56 [−5.64 to 6.76] | 0.861 | 0.01 [−0.02 to 0.04] | 0.573 | −0.39 [−3.26 to 2.48] | 0.790 | 0 [−0.04 to 0.04] | 0.962 |

| Experiment (Exp) |

Sham N=19 |

RPAO N=20 |

350.78 [151.04 to 550.52] | 0.002 | 13.2 [5.79 to 20.62] | 0.001 | 0.14 [0.11 to 0.16] | <0.001 | 10.06 [7.27 to 12.85] | <0.001 | 0.08 [0.04 to 0.11] | <0.001 |

| Sex:Exp |

M, RPAO N=10 |

347.53 [114.66 to 580.4] | 0.006 | 11.91 [3.27 to 20.56] | 0.011 | 0.1 [0.07 to 0.13] | <0.001 | |||||

| Gene:Exp | Bmpr2, RPAO N=10 | −277.86 [−510.73 to −44.99] | 0.026 | −10.13 [−18.78 to −1.48] | 0.028 | −0.05 [−0.08 to −0.02] | 0.005 | 11.97 [7.97 to 15.97] | <0.001 | 0.07 [0.02 to 0.12] | 0.007 | |

| Sex:Gene |

M, Bmpr2 N=9 |

−0.05 [−0.08 to −0.02] | 0.006 | |||||||||

LV indicates left ventricle; Mean diff., mean difference; MWT, medial wall thickness of pulmonary arteries; PA, pulmonary artery; RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; RV thickness, right ventricular thickness; and WT, wild type. Sham: female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=4; RPAO: female (F), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5; male (M), WT N=5, Bmpr2 N=5.

RPAO increased the Fulton index (+0.14 [0.11–0.16], P<0.001) with an additional effect in males compared with females (+0.10 [0.07–0.13], P<0.001), whereas Bmpr2 +/− animals had a lower increase of the Fulton index compared with WT (−0.05 [−0.08 to −0.02], P=0.005) (Figure 8C and Table 6, and Table S5 and S6).

The MWT in the nonobstructed territories quantifies the characteristic thickening of distal vessels in PH. The MWT for vessels with an external diameter <50 μm was higher in males compared with females (+2.90 [0.9–4.9] % P=0.007) and increased after RPAO as compared with sham (+10.06 [7.27–12.85] %, P<0.001), with an additional effect in Bmpr2 +/− rats (11.97 [7.97–15.97] %, P<0.001). For vessels with an internal diameter between 50 and 100 μm, MWT increased after RPAO as compared with sham (+0.08 [0.04–0.11] %, P<0.001), with an additional effect in Bmpr2 +/− rats (+0.07 [0.02–0.12] %, P=0.007) (Figure 8D, 8E, Table 6, and Tables S5 and S6).

RPAO Is Associated With Higher Mortality in Bmpr2 Mutant Rats

Across all experiments, no acute deaths were observed in WT rats after RPAO. In contrast, 29% of rats with Bmpr2 mutations died either during ligation or within minutes thereafter (P<0.001). This mortality effect is probably due to heart failure since Bmpr2‐deficient animals have a reduced ability to handle load stress, as previously described. 3

Chronic RPAO Is Associated With a Pulmonary Gene Expression Pattern Associated With Installed PAH in Unobstructed Territories, Exhibiting Sex Differences

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection analyses demonstrated that male and female rats differentially clustered according to this gene signature and shifted after RPAO (Figure 9A) according to the vectors depicted in Figure 9B.

Figure 9. UMAP analyses.

UMAP visualization of individuals in 2‐dimensional reduction unveiling distinct clusters for male and female rats based on the gene signature, and a notable shift occurred post‐RPAO (A). Link between genes' cycle threshold values and UMAP's dimensions illustrated by vectors of which coordinates are based on correlations coefficients (B). RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; UMAP Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction; and WT, wild type.

Using volcano plot analysis, we discerned genes exhibiting differential expression in the lungs of both sham‐operated rats and those with RPAO. The Htr1a, Tph2, Gdf2, Edn2, and Fbln2 genes had a corrected P value<0.05 and a log2 fold change <−1 (downregulated in RPAO) (Figure 10A, Table 7, and Table S7). The Il6 gene had a corrected P value<0.05 and a log2 fold change >1 (upregulated in RPAO) (Figure 10A, Table 7, and Table S7). In the gray zone, with a corrected P value<0.05 and a log2 fold change <0 and <−1 (modestly but significantly downregulated in RPAO), were the Endrb, Gng10, Gnb5, Spr, Rora, and Alox5 genes (Figure 10A, Table 7, and Table S7).

Figure 10. Volcano plot analyses.

Differential gene expression in the pulmonary unobstructed territories of rats with chronic RPAO compared with sham‐operated rats (A). Differential gene expression in the lungs of male rats compared with female rats (B). Upregulations are reported on the right and downregulations on the left. RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion;

Table 7.

Statistically Significant Differential Gene Expression in the Pulmonary Unobstructed Territories of Rats With Chronic RPAO Compared With Sham‐Operated Rats, Male Compared With Female Rats, and Bmpr2 Mutated Compared With WT Rats

| RPAO vs sham | Male vs female | Bmpr2 vs WT | Modulations and significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edn1 ↑ | Bcar3 ↑ | Fbln2↓ | |

| Edn2 ↓* | Ece1 ↑ | Ptgir ↑ | |

| Edn3 ↓ | Edn1 ↑* | Downregulated ↓ | |

| Ednrb ↓* | Edn2 ↑ | Upregulated ↑ | |

| Adra1a ↓ | Ednrb ↑ | Significant after correction* | |

| Bcl2 ↓ | Ptgs2 ↑ | log2 FC>|1| | |

| Bcl2l1 ↓ | Ptk2b ↑ | ||

| Bmp10 ↓ | Il6 ↑* | ||

| Fbln2 ↓* | Il6r ↑ | ||

| Gdf2 ↓* | Cyb5b ↑ | ||

| Htr1a ↓* | Cyb5r3 ↑ | ||

| Il6 ↑* | Nos1 ↑ | ||

| Il6r ↓ | Nos2 ↑ | ||

| Kdr ↓ | Gnb4 ↓* | ||

| Mrtfa ↓ | |||

| Prdm16 ↓ | |||

| Tph2 ↓* | |||

| Cyb5b ↓ | |||

| Cyb5r3 ↓ | |||

| Nos1 ↑ | |||

| Rora ↓* | |||

| Spr ↓* | |||

| Alox5 ↓* | |||

| Gnb5 ↓* | |||

| Gng10 ↓* | |||

| Gng3 ↓ | |||

| Tbxas1 ↑ |

Full gene expression analysis in Table S7.

The names of genes whose differential expression is statistically significant after correction (corrected p‐value) are highlighted.

RPAO, right pulmonary artery occlusion; and WT, wild type.

We also discerned genes exhibiting differential expression in the lungs of males and females. The Il6 and the Edn1 genes had a corrected P value<0.05 and a log2 fold change >1 (upregulated in males) (Figure 10B, Table 7 and Table S7). In the gray zone, with a corrected P value<0.05 and a log2 fold change <0 and <−1 (modestly but significantly downregulated in males), was the Gnb4 gene (Figure 10B, Table 7, and Table S7).

Our analysis lacked sufficient power to identify genes modulated by the Bmpr2 mutation or by the RPAO:gene, RPAO:sex, or gene:sex interactions.

Discussion

We developed a new experimental PH model and demonstrated that RPAO initiates the onset of PH in rats with and without Bmpr2 mutations.

Intriguingly, RPAO induced precapillary PH not only in Bmpr2‐mutated rats but also in WT animals, thus establishing this procedure as a novel rat model for PH. RPAO induced acute PH at ligation, corroborating previous human findings showing that occlusion greater than 30% consistently increases mPAP in patients with pulmonary embolism and no previous cardiopulmonary disease; the severity of PH in chronic thromboembolic PH also being influenced by the degree of vascular obstruction, which generally exceeds 40% of the pulmonary vascular bed in the majority of cases. 16 , 17 Notably, acute RPAO unveiled sex‐ and Bmpr2‐dependent pulmonary vascular and RV response to the sudden rise in PVR, likely stemming from preexisting disparities in pulmonary vascular and RV structure and function. Chronic RPAO, on the other hand, allowed us to demonstrate both sex‐ and Bmpr2‐dependent pulmonary vascular and RV remodeling and adaptation to PH over time. Indeed, the absence of reported preoperative differences in RVSP between the mutated group and the WT group does not necessarily implies a similar pulmonary vascular state. For instance, patients with normal resting pulmonary hemodynamics may still experience a decreased PVR due to early and unrecognized precapillary pulmonary vascular involvement. In clinical practice, this condition may be revealed by documenting an abnormal mPAP/CO relationship during stress tests, especially during exercise. These findings are known to contribute significantly to the identification of early pulmonary vascular diseases, 18 , 19 including in adults carrying a BMPR2 mutation. 12 Such insights may have prognostic implications. 20 Similarly, in our study, the increased stress placed on the RV during acute and chronic RPAO may well have unmasked impaired pulmonary vascular reserve in the mutated group despite normal preoperative hemodynamics.

RPAO triggered more severe acute and chronic PH in males and Bmpr2 mutant rats compared with their female and WT counterparts. Moreover, Bmpr2 mutant rats exhibited poorer adaptation to RPAO, characterized by increased post‐RPAO mortality, reduced RV IC, and diminished adaptive RV hypertrophy alongside elevated PVR.

Although PAH is more prevalent in women, an interesting paradox emerges as men often face a worse prognosis. 21 , 22 , 23 The intricacies behind this disparate outcome remain partially veiled, with 1 plausible explanation rooted in the realm of RV function. Notably, Jacobs et al. unearthed that, during transplant evaluations, women exhibited superior RV function compared with men. Despite similar hemodynamic parameters, this advantage extended to a more favorable response to medical interventions. 24 Further reinforcing this sex‐based divergence, Tello et al. highlighted that women boast enhanced RV contractility and RV‐PA coupling, with a lower RV mass index when juxtaposed with their male counterparts. 25 When translating these observations into experimental PH, female subjects outshine males regarding RV function. A higher cardiac index evidences this better RV function, reduced cardiac hypertrophy, and the beneficial influence of estrogen receptors α and β agonists, particularly through estrogen receptor‐α stimulation. 26 Alternatively, our study revealed distinct clustering patterns of males and females based on a PH‐associated gene signature before and after RPAO. Half of the genes showing differential expression between male and female rats (7 out of 14) were associated with the endothelin pathway, underscoring its significance in the sex differences observed. Notably, genes such as Edn1, Edn2, Ednrb, Ece1, Bcar3, Ptgs2, and Ptk2b were overexpressed in males compared with females. Ptgs2 is one of the immediate genes upregulated by endothelin‐1and play a role in the endothelin‐mediated signaling pathways affecting cardiac and vascular function. 27 The activation of Ptk2b and other protein tyrosine kinases by endothelin‐1 is part of broader signaling mechanisms that regulate cellular responses such as growth, differentiation, and vasoconstriction. 28 Finally, the p130Cas/BCAR3 cascade regulates adhesion and spreading of glomerular mesangial cell in response to endothelin‐1. 29 Our study highlights the pivotal role of the endothelin pathway in driving male susceptibility to PH, particularly through genes such as Edn1, Ptgs2, and Ptk2b. These genes are instrumental in regulating crucial cellular processes including growth, vasoconstriction, and cellular adhesion, which contribute to pulmonary vascular dysfunction. Furthermore, the MWT for vessels with an external diameter of less than 50 μm demonstrated a notable disparity, with males displaying higher values than females. This underscores the presence of sex‐related structural differences in the pulmonary vascular bed.

To explain why the mutation doesn't always manifest in symptoms, the PAH community adopted the “multiple‐hit hypothesis.” This theory suggests that the development of pulmonary vascular disease begins with BMPR2 mutations interacting with 1 or more initial triggers. Inflammation, recognized as a central element in PAH development, 30 led some researchers to propose that BMPR2 mutations and inflammation work together to trigger the disease's clinical symptoms. Studies conducted both in vitro and in vivo demonstrated a disrupted feedback loop between IL‐6 (interleukin‐6, a key proinflammatory cytokine) and BMPR‐II signaling. This indicates that a significant effect of BMPR2 mutations could be the inadequate regulation of cytokines, making individuals more susceptible to an inflammatory secondary trigger. 31 In our study, Il6 emerged as the gene most notably overexpressed in the lungs affected by high flow and high pressure in unobstructed areas compared with sham controls. Additionally, IL‐6 can induce the expression of vascular endothelial hgrowth factor, a critical agent in angiogenesis, across various cell types. This suggests a potential role for IL‐6 in linking vascular proliferation and repair processes. 32 Moreover, Il6 overexpression discriminated rats with spontaneous PH in Bmpr2‐mutated rats. 3 This finding supports the hypothesis that RPAO‐induced Il6 overexpression may act as a key trigger in precipitating PH under conditions of Bmpr2 dysfunction.

Conversely, fibulin‐2 (FBLN2) is the gene most significantly downregulated in unobstructed areas compared with sham controls. FBLN2, an extracellular matrix protein, 33 belongs to a 7‐member family of extracellular glycoproteins. FBLN2 serves as a scaffold protein in the extracellular matrix by binding to various ligands, including type IV collagen, aggrecan, and versican. 34 FBLN2 and FBLN5 have been shown recently to cooperate in forming the internal lamina of blood vessels. 35 Furthermore, and consistent with a role of FBLN2 in PAH, a rare variant analysis of 4241 PAH cases from an international consortium recently implicated FBLN2 rare variants in PAH. 36 However, the exact contribution of FBLN2 in vascular cell reprogramming and consequent PH development remains enigmatic. The decrease in FBLN2 expression induced by RPAO may also play a role in the complex multihit mechanism underlying PH development in animals with Bmpr2 mutations.

Patients with PAH and BMPR2 mutations present at a younger age with more severe disease and are at increased risk of death, and death or transplantation, compared with those without BMPR2 mutation. 37 Considering that the predominant portion of the excess risk linked to a BMPR2 mutation is ascribed to a diminished cardiac index during diagnosis, the impaired adaptation of the RV to heightened afterload in those with BMPR2 mutations emerges as a crucial factor, as indicated by previous preclinical studies. Transgenic mouse models with and without RV expression of mutant Bmpr2, along with a model inducing RV hypertrophy (PA banding), were used to demonstrate that the expression of mutant Bmpr2 in the RV correlates with compromised RV hypertrophic responses and diminished hemodynamic compensation in the face of load stress, 38 thereby reinforcing and aligning with the findings observed in our rat study.

Actually, we previously demonstrated that in the absence of load stress and spontaneous PH, Bmpr2 mutant rats already show intrinsic RV dysfunction, highlighted by decreases in CO, RV cardiomyocyte size, and action potential duration; decreases in active tension development and sensitivity to Ca2+ in skinned RV cardiomyocytes; and reduced [Ca2+]i transients, SR Ca2+ load, and cell shortening. 3 Those asymptomatic features at baseline can compromise RV adaptation to increased afterload. Within the pulmonary context, our previous study highlighted several noteworthy aspects in Bmpr2 mutant rats. These encompassed distal muscularization, diminished endothelium‐dependent relaxation, perivascular matrix remodeling, decreased microvascular density, and inflammation, all evident before the physiological onset of PH. 3 These asymptomatic features can potentially exacerbate both acute hemodynamic response and chronic remodeling of the pulmonary arterial system within the realm of pulmonary arterial stress induced by RPAO.

Studies have suggested that high pulmonary vascular stiffness (low pulmonary arterial compliance) is an important predictor of poor survival in PAH. 39 , 40 The predominant theory suggests that vascular remodeling induces a persistent stiffening of the pulmonary tree, subsequently causing an increase in right ventricular afterload. However, recent studies have advanced the concept that vascular stiffening and extracellular matrix remodeling are early and potent pathogenic triggers in PAH. 41 Importantly, these events occur at time points preceding the typical manifestation of hemodynamic and histologic evidence of PAH or medial thickening. 41 Computational studies have also established that proximal arterial stiffness influences wall shear. 42 Our study demonstrates that acute and chronic RPAO contribute to increased PA stiffness. Moreover, Bmpr2 mutations exacerbate this stiffness, potentially contributing to the deterioration of the cardiopulmonary function observed in Bmpr2 mutant rats.

Lastly, increased HR is the primary mechanism for patients with ventricular dysfunction to augment pulmonary blood flow. 43 However, HR response in PAH is variable, and chronotropic incompetence can occur in advanced PAH. 43 Chronic RPAO‐induced PH was associated with increased HR, but this chronotropic response was almost abolished in Bmpr2 mutant rats. This suggests that Bmpr2 mutant rats display an altered RV adaptation to increased afterload characterized by a poorer hypertrophic and chronotropic response to PH. However, the lower CO in Bmpr2‐mutated animals can be related to this lower HR, which warrants further discussion. In patients with idiopathic PAH, it has been shown that RV myocardial oxygen consumption is markedly increased and is positively related to both RVSP and HR, which are its primary determinants. 44 In Bmpr2‐mutated animals subjected to substantial increases in RVSP, the absence of HR elevation in response to the decreased SV may appear detrimental to CO preservation at rest. However, this could be viewed as beneficial from an integrated thermodynamic perspective. This phenomenon may mitigate excessive elevation in the rate‐pressure product (RVSP×HR) and, consequently, RV myocardial oxygen consumption. Notably, supporting this hypothesis, the absence of HR elevation has been shown to be beneficial as it is associated with a more favorable prognosis than cases where HR is elevated in patients with idiopathic PAH. 45 Additionally, it may be hypothesized that the lack of HR increase relatively preserves diastolic duration, which then underscores the dependence of right coronary filling on diastolic time during chronic PH states. Although right coronary filling takes place in both systole and diastole in normotensive states, this dependence is due to the fact that systolic pulmonary artery pressure may then approach systemic levels, mimicking the dependence of left coronary filling on diastolic time. 46

Rat models of severe PH commonly rely on monocrotaline injection, an endothelial toxin from the pyrrolizidine alkaloid family, or the combined use of sugen and hypoxia. Monocrotaline injection, although effective, presents challenges such as dose‐dependent toxicity with high fatality rates and inflammatory responses. Rats exposed to monocrotaline also exhibit various complications, including pulmonary interstitial edema, hepatic veno‐occlusive disease, renal toxicity, myocarditis, and a postcapillary component linked to coronary toxicity. 47 On the other hand, the sugen hypoxia model is categorized as group 3 PH, lacking a faithful recapitulation of the pathophysiology seen in isolated precapillary PH. Notably, both models require the administration of toxic substances, raising concerns about potential uncontrolled side effects. In this context, we introduce a novel experimental PH model that mirrors the hemodynamic characteristics observed in our patients. Importantly, this model eliminates the need for toxic exposure, mitigating the risks associated with toxic metabolites and offering a more controlled and reliable experimental setup. Moreover, dysregulated pulmonary expression of genes associated with pathways known to be dysregulated in PAH, that is, the endothelin (Edn1, Edn2), prostacyclin (Gnb4, Gnb5, and Gng10), and BMP pathways (Gdf2) underscores the pathophysiological and preclinical significance of this innovative rat model of PH. 48 , 49

Limitations

In our earlier investigation of the model, 3 our Bmpr2 mutant rats (Bmpr2 +/Δ71Ex1 ) exhibited age‐dependent spontaneous PH characterized by a relatively low penetrance (16% at 6 months and 27% at 1 year). However, in the current series, spontaneous PH was conspicuously absent. Although we cannot dismiss the possibility of environmental changes and microbiota alterations within our rat line or a generational loss of the pulmonary hypertensive phenotype, our findings underscore the persistence of intrinsic vascular and cardiac abnormalities even in the absence of spontaneous PH, predisposing the animal to challenge‐induced PH.

The existing literature encompasses diverse rodent models exhibiting BMPR2 deficiency with mutations at different loci, 50 raising concerns about the generalizability of our findings to other models of Bmpr2 mutations. Nevertheless, CRISPR‐mediated Bmpr2 point mutation (Bmpr2 +/44insG ) has been recently shown to exacerbate late pulmonary vasculopathy and reduce survival in rats with monocrotaline‐induced severe PH. 51 Notably, no discernible functional or structural disparities were observed compared with the WT rats at baseline, extending even to 6 months of age. Moreover, the occurrence of exercise‐induced PH in asymptomatic BMPR2 mutation carriers across different families suggests a shared susceptibility to challenge‐induced PH in varied contexts of Bmpr2 mutation. 52

The observed disparity in the chronotropic response within our model, contingent upon sex and Bmpr2 dependence, might be attributed to a variable sensitivity to anesthesia across conditions. This aspect necessitates further exploration in future research endeavors.

Strengths

The RPAO model outperforms other models of pulmonary artery banding that display variability in surgical procedures, particularly regarding the consistency of the pulmonary artery constriction. To address this, the authors must check and provide quantitative data, such as a transbanding gradient measurement, to confirm uniformity of constriction across all subjects. This RPAO model eliminates variability in surgical procedures, as there are no degrees of constriction; instead, a uniform and robust full ligation of the RPA is employed, amputating the same proportion of the pulmonary vasculature regardless of the animals' age, sex, size, weight, or genetic background. There is no flow in the obstructed territories and high flow and high pressure in the unobstructed territories. In addition, this model increases RV afterload and constrains the left pulmonary vasculature, which receives the entire cardiac output. In contrast, the pulmonary artery banding model only constrains the RV.

Conclusions

The induction of right pulmonary artery occlusion in rats results in the development of patent precapillary PH. RPAO triggers more severe PH in Bmpr2 mutant and male rats, highlighting the influence of genetic and sex factors. The study further reveals that Bmpr2 mutant rats display poorer adaptation to RPAO, evidenced by increased post‐RPAO mortality, reduced RV contractility index, and a diminished hypertrophic and chronotropic response to PH. This RPAO‐induced PH model stands out as a groundbreaking, nontoxic, sex‐dependent representation of precapillary PH. Our novel 2‐hit rat model presents a promising avenue for assessing the RV and pulmonary vascular adaptation to PH and the impact of genetic abnormalities (such as loss‐of‐function mutations in BMPR2 but also in TBX4, SOX17, EIF2AK4, or KCNK3).

Sources of Funding

Dr Perros received funding from the French National Research Agency (Agence Nationale de la Recherche, Grant ANR‐20‐CE14‐0006) and from INSERM (International Research Project (IRP): Paris—Porto Pulmonary Hypertension Collaborative Laboratory (3PH)). Dr Grynblat is supported by Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Poste d'accueil INSERM), and a scholarship from the French Pediatric Society. Dr Todesco is supported by ADETEC (association chirurgicale pour le développement et l'amélioration des techniques de dépistage et de traitements des maladies cardio‐vasculaires).

Disclosures

D. Bonnet reports grants and consulting fees from Janssen and Novartis; and participation on the advisory board for Lupin, outside the submitted work. M. Humbert and D. Montani have relationships with drug companies, including Actelion, Bayer, GSK, Novartis, and Pfizer. In addition to being investigators in trials involving these companies, other relationships include consultancy services and memberships to scientific advisory boards outside the submitted work. S. Malekzadeh‐Milani reports grants from Acte. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S7

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Alban Todesco, Julien Grynblat, David Boulate, and Frédéric Perros participated in the design of the study. Alban Todesco, Julien Grynblat, Frédéric Perros, Kouamé F. Akoumia, Damien Bonnet, David Montani, Sophie‐Guiti Malekzadeh‐Milani, Carine Vastel‐Amzallag, Mathilde Méot, and Maria‐Rosa Ghigna participated in acquisition of the data. Alban Todesco, Frédéric Perros, Stéphane Morisset, and Julien Grynblat participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors reviewed the article.

A. Todesco and J. Grynblat are co‐first authors.

This article was sent to Sébastien Bonnet, PhD, Guest Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.124.034621

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 21.

K. F. Akoumia and D. Bonnet are co‐second authors.

D. Boulate and F. Perros are co‐last authors.

References

- 1. Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, Badagliacca R, Berger RMF, Brida M, Ghofrani A, Gibbs JSR, Grünig E, Hassoun PM, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3618–3731. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guignabert C, Bailly S, Humbert M. Restoring BMPRII functions in pulmonary arterial hypertension: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2017;21:181–190. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2017.1275567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hautefort A, Mendes‐Ferreira P, Sabourin J, Manaud G, Bertero T, Rucker‐Martin C, Riou M, Adão R, Manoury B, Antigny F, et al. Bmpr2 mutant rats develop pulmonary and cardiac characteristics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2019;139:932–948. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soon E, Crosby A, Southwood M, Yang P, Tajsic T, Toshner M, Lamb J, Treacy C, Toshner R, Sheares K, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II deficiency and increased inflammatory cytokine production. A gateway to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:859–872. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1509OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Song JJ, Celeste AJ, Kong FM, Jirtle RL, Rosen V, Thies RS. Bone morphogenetic protein‐9 binds to liver cells and stimulates proliferation. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4293–4297. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tian W, Jiang X, Sung YK, Shuffle E, Wu TH, Kao PN, Zaiman A, Erzurum SC, Lee PJ, Trow TK, et al. Phenotypically silent bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 mutations predispose rats to inflammation‐induced pulmonary arterial hypertension by enhancing the risk for neointimal transformation. Circulation. 2019;140:1409–1425. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Limoges M, Langleben D, Fox BD, Shear R, Wieczorek P, Rudski LG, Hassan A, Seager MJ, Westcott JY, Elliott CG, et al. Pregnancy as a possible trigger for heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2016;6:381–383. doi: 10.1086/686993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abramowicz MJ, van Haecke P, Demedts M, Delcroix M. Primary pulmonary hypertension after amfepramone (diethylpropion) with BMPR2 mutation. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:560–562. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00095303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jaliawala HA, Parmar M, Summers K, Bernardo RJ. A second hit? Pulmonary arterial hypertension, BMPR2 mutation, and exposure to prescription amphetamines. Pulm Circ. 2022;12:e12053. doi: 10.1002/pul2.12053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mair KM, Johansen AKZ, Wright AF, Wallace E, MacLean MR. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: basis of sex differences in incidence and treatment response. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:567–579. doi: 10.1111/bph.12281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Larkin EK, Newman JH, Austin ED, Hemnes AR, Wheeler L, Robbins IM, West JD, Phillips JA, Hamid R, Loyd JE, et al. Longitudinal analysis casts doubt on the presence of genetic anticipation in heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:892–896. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0886OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Montani D, Girerd B, Jaïs X, Laveneziana P, Lau EMT, Bouchachi A, Hascoet S, Tcherakian C, Bouvaist H, Parent F, et al. Screening for pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults carrying a BMPR2 mutation. Eur Respir J. 2021;58:2004229. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04229-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Castañer E, Gallardo X, Rimola J, Pallardó Y, Mata JM, Perendreu J, Armengol M, Ballabriga S, Pallisa E, Speckles P, et al. Congenital and acquired pulmonary artery anomalies in the adult: radiologic overview. Radiographics. 2006;26:349–371. doi: 10.1148/rg.262055092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Razavi H, Stewart SE, Xu C, Sawada H, Zarafshar SY, Taylor CA, Feinstein JA, Huang Y, Rogers EM, Reddy VM, et al. Chronic effects of pulmonary artery stenosis on hemodynamic and structural development of the lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;304:L17–L28. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00412.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bergersen L, Gauvreau K, Justino H, Nugent A, Rome J, Kreutzer J, Ringel R, Vincent R, Lock JE, Jenkins KJ, et al. Randomized trial of cutting balloon compared with high‐pressure angioplasty for the treatment of resistant pulmonary artery stenosis. Circulation. 2011;124:2388–2396. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.018200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dartevelle P, Fadel E, Mussot S, Chapelier A, Hervé P, de Perrot M, Lehoux P, Simonneau G, Sitbon O, Parent F, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:637–648. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00079704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McIntyre KM, Sasahara AA. The hemodynamic response to pulmonary embolism in patients without prior cardiopulmonary disease. Am J Cardiol. 1971;28:288–294. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(71)90116-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Herve P, Lau EM, Sitbon O, Savale L, Montani D, Godinas L, Bourdin A, Weatherald J, Jaïs X, Parent F, et al. Criteria for diagnosis of exercise pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:728–737. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00021915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeder K, Banfi C, Steinrisser‐Allex G, Maron BA, Humbert M, Lewis GD, Kovacs G, Widimsky J, Steinberger S, Kovacs K, et al. Diagnostic, prognostic and differential‐diagnostic relevance of pulmonary haemodynamic parameters during exercise: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2022;60:2103181. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03181-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Douschan P, Avian A, Foris V, Sassmann T, Bachmaier G, Rosenstock P, Dabizzi RP, Mayer E, Klepetko W, Lang I, et al. Prognostic value of exercise as compared to resting pulmonary hypertension in patients with normal or mildly elevated pulmonary arterial pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206:1418–1423. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202112-2856LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg‐Maitland M, Frantz RP, Foreman AJ, Coffey CS, Frost AE, Barst RJ, Elliott CG, McGoon MD, et al. Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long‐Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation. 2010;122:164–172. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.898122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoeper MM, Huscher D, Ghofrani HA, Delcroix M, Distler O, Schweiger C, Ulrich S, Grunig E, Staehler G, Lange TJ, et al. Elderly patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the COMPERA registry. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:871–880. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, Bertocchi M, Habib G, Gressin V, Yaici A, Weitzenblum E, Cordier JF, Chabot F, et al. Survival in patients with idiopathic, familial, and anorexigen‐associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Circulation. 2010;122:156–163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.911818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jacobs W, van de Veerdonk MC, Trip P, de Man F, Heymans MW, Marcus JT, Oosterveer F, Westerhof N, Vonk‐Noordegraaf A, Boonstra A, et al. The right ventricle explains sex differences in survival in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2014;145:1230–1236. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tello K, Richter MJ, Yogeswaran A, Ghofrani HA, Naeije R, Vanderpool R, Seeger W, Rosenkranz S, Gall H. Sex differences in right ventricular‐pulmonary arterial coupling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1042–1046. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0807LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frump AL, Goss KN, Vayl A, Albrecht M, Fisher A, Tursunova R, Meza AZ, Brittain EL, Lahm T, Friedberg MK, et al. Estradiol improves right ventricular function in rats with severe angioproliferative pulmonary hypertension: effects of endogenous and exogenous sex hormones. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L873–L890. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00006.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giraldo A, Barrett OPT, Tindall MJ, Fuller SJ, Amirak E, Bhattacharya BS, O'Neill SC, Kentish JC, Avkiran M. Feedback regulation by Atf3 in the endothelin‐1‐responsive transcriptome of cardiomyocytes: Egr1 is a principal Atf3 target. Biochem J. 2012;444:343–355. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Simonson MS, Wang Y, Herman WH. Ca2+ channels mediate protein tyrosine kinase activation by endothelin‐1. Am J Phys. 1996;270:F790–F797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rufanova VA, Alexanian A, Wakatsuki T, Lerner A, Sorokin A. Pyk2 mediates endothelin‐1 signaling via p130Cas/BCAR3 cascade and regulates human glomerular mesangial cell adhesion and spreading. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:45–56. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Perros F, Humbert M, Dorfmüller P. Smouldering fire or conflagration? An illustrated update on the concept of inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2021;30:210161. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0161-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perros F, Bonnet S. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II and inflammation are bringing old concepts into the new pulmonary arterial hypertension world. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:777–779. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1115ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cohen T, Nahari D, Cerem LW, Neufeld G, Levi BZ. Interleukin 6 induces the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:736–741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]