Abstract

Previously it was reported that the 16-amino-acid (aa) C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) transmembrane protein Pr15E is cleaved off during virus synthesis, yielding the mature, fusion active transmembrane protein p15E and the 16-aa peptide (R peptide or p2E). It remains to be elucidated how the R peptide impairs fusion activity of the uncleaved Pr15E. The R peptide from MoMLV was analyzed by Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunostained with antiserum against the synthetic 16-aa R peptide. The R peptide resolved with an apparent molecular mass of 7 kDa and not the 4 kDa seen with the corresponding synthetic peptide. The 7-kDa R peptide was found to be membrane bound in MoMLV-infected NIH 3T3 cells, showing that cleavage of the 7-kDa R-peptide tail must occur before or during budding of progeny virions, in which only small amounts of the 7-kDa R peptide were found. The 7-kDa R peptide was palmitoylated since it could be labeled with [3H]palmitic acid, which explains its membrane association, slower migration on gels, and high sensitivity in immunoblotting. The present results are in contrast to previous findings showing equimolar amounts of R peptide and p15E in virions. The discrepancy, however, can be explained by the presence of nonpalmitoylated R peptide in virions, which were poorly detected by immunoblotting. A mechanistic model is proposed. The uncleaved R peptide can, due to its lipid modification, control the conformation of the ectodomain of the transmembrane protein and thereby govern membrane fusion.

The envelope proteins of retroviruses are important for the viral entry and subsequent delivery of viral RNA into the host cells. In the ecotropic Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV), the envelope precursor protein gPr80env is proteolytically cleaved into two subunits, surface protein (SU) and transmembrane protein (TM), by a cellular protease (45). The SU is involved in receptor recognition and binding (3), whereas the TM is responsible for the fusion between viral and cellular membranes (16). In MoMLV, SU is a 70-kDa glycoprotein (gp70) and TM is a 17-kDa polypeptide, Pr15E. Further processing of the Pr15E by a viral protease, at the moment of budding or in virions, reveals a 15-kDa protein, p15E (or p12E), and a 16-amino-acid (aa) oligopeptide, the R peptide (or p2E) (12, 36), which in virions ends up in a 1:1 ratio to p15E (14).

Truncation of the full R peptide renders the Env complex highly fusogenic, resulting in massive syncytium formation in NIH 3T3 cells (28, 29). The R peptide thus appears to act as a safety catch preventing premature fusion, but it is not known how it acts.

Lipid modification by palmitic acid (S-acylation being prevalent) has been reported for a number of viral and cellular membrane proteins (7, 31, 43). Palmitoylation of proteins has been shown to play a considerable role, especially in protein-protein interactions such as signal transduction between G-protein-coupled receptors and G proteins in eukaryotic cells (23). Reversible palmitoylation due to the unstable esterification of cysteine thiol groups by palmitic acid may be regulated, unlike N-myristylation, which is a “permanent” modification (30). The covalent fatty acid binding to carbon chains facilitates plasma membrane localization (6). Additionally, it has a significant function in assembly and release of virus particles (18). A recent study has shown that palmitoylation of human thyrotropin receptor enhances the rate of intracellular trafficking of the receptor (39). Finally, the issue of whether fatty acid modification is important in catalyzing the fusogenic abilities of influenza A virus hemagglutinin (HA) has been discussed (24, 27).

Lately, it has been noted that palmitoylation of viral envelope proteins (retroviruses, adenoviruses, togaviruses, and paramyxoviruses) usually takes place at cysteine residues located within the transmembrane domain or in the cytoplasmic tail close to this domain (13, 15, 34, 41, 48). The thioester linkage of fatty acids to a number of viral membrane glycoproteins (vesicular stomatitis virus G, Sindbis virus E1, and influenza A virus HA) is a posttranslational event that takes place in the cis or medial Golgi after exit from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and after oligomerization but prior to acquisition of endo H (endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase H) resistance (5, 42). Studies have verified that a number of envelope proteins from retroviruses are palmitoylated, e.g., Pr15E of Friend murine leukemia virus, gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), gp65 of spleen focus-forming virus and gp35 of Rous sarcoma virus (11, 38, 46, 48).

In the present study, we have resolved the R peptide by tricine-sodium-dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Tricine-SDS-PAGE) and visualized it by immunoblotting with an antibody raised against a synthetic R peptide. The R peptide was observed in the host cell, where it was membrane bound and palmitoylated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

NIH 3T3 cells, obtained as a generous gift from B. M. Willumsen, University of Copenhagen, were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, nonessential amino acids, penicillin, and streptomycin. MoMLV (an ecotropic MLV) was obtained from Research Resources, National Cancer Institute (NCI), Bethesda, Md. MoMLV-containing medium was collected from chronically infected cultures of NIH 3T3 with a titer corresponding to ca. 106 PFU per ml.

Membrane preparations from infected NIH 3T3 cells.

Membrane fragments from infected NIH 3T3 cells were made according to the method of Maeda et al. (Method Three [20]). Briefly, cells were homogenized in hypotonic buffer, and membranes were collected on 41% sucrose by centrifugation at 45,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C in a Beckman SW60 swinging-bucket rotor. The protein concentration of the membrane preparations dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was adjusted to ca. 0.32 μg/ml as determined by use of the Micro BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Chemical cross-linking.

The thiol-cleavable cross-linking reagent, DSP (dithiobis[succinimidylpropionate]) was obtained from Pierce. Cross-linking was performed in 25-μl aliquots, containing membranes. DSP was used at 0.05 to 1 mM and incubated 1 h on ice and 15 min at room temperature (RT). Tris base was added to give a 50 mM final concentration and, after an additional 15 min at RT, a gel loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; 2.5 mM EDTA; 2% SDS; 5% glycerol; 20 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) was added. The samples were then boiled for 5 min at 100°C. Nonreduced samples were neither boiled nor supplied with DTT.

Detection of viral proteins.

Virus samples were concentrated from 1.5 ml of supernatant obtained from subconfluent infected NIH 3T3 cells grown for 20 h in 8.8-cm2 dishes (Nunc/Life Technologies, Copenhagen, Denmark). The supernatant was centrifuged through a 10% sucrose cushion in a microcentrifuge for 1 h at 4°C, 30,000 × g. The pellet was then lysed in gel loading buffer. Cell lysates were prepared from the same dish as was the virus by adding 200 μl of lysis buffer (250 mM NaCl; 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 5 mM EDTA; 1% NP-40; 1% SDS; 100 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride per ml). Lysates (40 μl) were mixed with gel loading buffer and boiled as described above.

Protein separation was done by Tricine-SDS-PAGE. The gels were essentially made according to the method of Schägger and von Jagow (32). The gels consisted of a stacking gel (4% acrylamide [acrylamide-bisacrylamide, 29:1]), a “spacer” gel (10% acrylamide) and a separating gel (16.5% acrylamide). The separating dimensions were 4 by 10 by 0.15 cm. The specific MoMLV Env proteins were detected by immunoblotting on Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

The R peptide was detected by using a 1:500 dilution of rabbit polyclonal anti-R-peptide serum raised against a synthetic R peptide (NH2-V-L-T-Q-Q-Y-H-Q-L-K-P-I-E-Y-E-P-COOH; 1.986 kDa). The gp70, as well as Pr15E and p15E, was detected with antiserum kindly donated by B. A. Nexø and Alan Rein, respectively. The secondary antibody was horseradish peroxidase-conjugated swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and used at dilutions of 1:1,500. Positive bands were visualized with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Amersham) and Cronex 4 X-ray films (Dupont-NEN, Boston, Mass.).

Radioactive labeling with palmitic acid.

Subconfluent cell layers in 8.8-cm2 dishes were rinsed twice with DMEM and supplemented with 19 MBq of [3H]palmitic acid (1,900 Bq/pmol; DuPont-NEN). The duration of the incorporation was 4.5 h at 37°C, whereby an uptake of ca. 80% was obtained. The monolayers were then washed twice with DMEM for 5 min and once for 5 min with PBS (supplemented with bovine serum albumin [essentially fatty acid-free] from Sigma, St. Louis, Mo., at 2 mg/ml) and hereafter solubilized in lysis buffer. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C and at 10,000 × g. The samples were immunoprecipitated with the anti-R-peptide, and the immunocomplexes were captured on protein G-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow beads (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, and the immunocomplexes were released by using gel loading buffer at 100°C.

The immunoprecipitated samples for two-dimensional (2D) electrophoresis were solubilized and denatured in 50 μl of 9.8 M urea (molecular biology grade; Appligene); 2% ampholines, pH 5 to 8 (Ampholine, 40% [wt/vol]; LKB, Bromma, Sweden); 4% NP-40; and 100 mM DTT. The samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min prior to loading.

2D-gel PAGE.

Isoelectric focusing gels were prepared in glass capillaries with dimensions of 7.3 by 0.1 cm. Gel mixtures were essentially prepared as described by O’Farrell (26) and Ames and Nikaido (1). The mixtures consisted of 2.87 g of urea; 0.67 ml of 30% acrylamide; 0.88 ml of H2O; 0.379 ml of ampholines, pH 3.5 to 9.5 (Ampholine, 0.4 g/ml; Pharmacia Biotech); 1.01 ml of 10% NP-40; 8 μl of TEMED (N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylene diamine); and 8 μl of 10% ammonium persulfate. The capillaries were applied onto the Mini 2D Electrophoresis Cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) and the samples were loaded with a 15-μl overlay (8 M urea; 1% ampholines, pH 5 to 8; 5% NP-40; 10 mM DTT). Running conditions were 15 min at 400 V and then 3.5 h at 750 V, with 45 mM NaOH as the upper buffer and 3.5 mM ortho-phosphoric acid as the lower buffer.

After the isoelectric focusing was completed, the tube gels were extruded by connecting them to a tube gel ejector (Bio-Rad). (An empty tube gel was sliced in pieces of 1 cm and suspended in 20 mM KCl overnight, followed by pH measurements.) The tube gels were equilibrated for 10 min in 150 μl of 2× gel loading buffer at RT. Afterwards the buffer was removed completely from the gels to prevent further sample diffusion. The tube gels were then placed in the second-dimension gel (Tricine-SDS-PAGE), with the same composition as mentioned above. The running conditions were 30 mA/gel. The radioactive protein gels were treated with sodium salicylate (8) for 30 min, dried, and fluorographed by using Hyperfilm ECL (Amersham), with exposure times of ca. 1 week.

Analysis of fatty acids by TLC.

Infected NIH 3T3 cells were labeled with [3H]palmitic acid, immunoprecipitated, and run on 2D gels as described above. The R peptide was localized by fluorography, and the spots were then excised and washed with distilled water to remove the scintillator. The spots were hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl at 110°C overnight. The lipid portion was extracted with hexane and then dried by a gentle N2 stream. Dried samples were redissolved in 40 μl of hexane and applied onto an RP-18 thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate (Merck, Mannheim, Germany), with acetonitrile-glacial acetic acid (1:1) as the solvent system. Fractions were scraped off the plate, and β-emissions were counted in a scintillation counter. [3H]palmitic acid and [3H]myristic acid (DuPont-NEN) were used as the standards.

Analysis of hydroxylamine stability of palmitic acid-labeled proteins.

Gels were sliced, and the slices were swelled in water. They were washed overnight at RT in 500 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and subsequently washed overnight in 500 μl of 1 M NH2OH-HCl at pH 7.5. For each slice, the radioactivity remaining in the gel and in the hydroxylamine wash was determined with a beta-counter.

RESULTS

Detection of the R peptide.

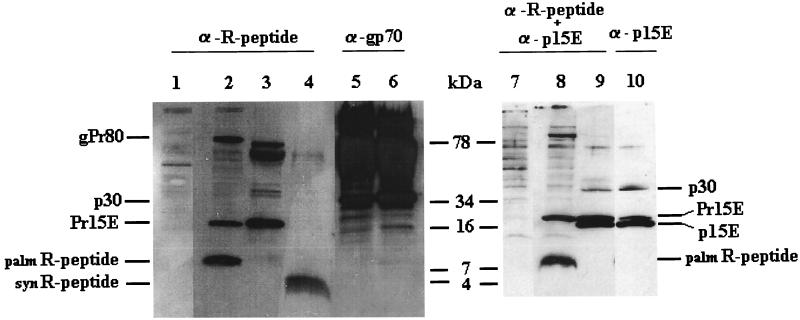

In Fig. 1 (lanes 3, 9, and 10) it can be seen that the antiserum raised against the synthetic R peptide is specific, since it recognizes Pr15E but not p15E. With 5 μg of synthetic R peptide a weak, broad band at an apparent size of 4 kDa was observed (Fig. 1, lane 4), which is designated as the synR peptide. This amount was the detection limit for synR peptide (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Identification of the R peptide in cell lysates and virus pellets. Proteins in cell lysates and virus pellets were analyzed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted as described in Materials and Methods with anti-R peptide, anti-gp70, and anti-p15E by using the ECL detection system. Lanes: 1, NIH lysate; 2, infected NIH lysate; 3, MoMLV; 4, synthetic R peptide (5 μg); 5, infected NIH lysate; 6, MoMLV; 7, NIH lysate; 8, infected NIH lysate; 9 and 10, MoMLV obtained from the NCI (10 μg).

The difference in the observed and expected migration lengths of the synthetic peptide can be explained by the Tricine gel system, where Tricine is used as a trailing ion. This gel system separates proteins of less than 20 kDa from the bulk SDS and thereby causes the small peptides to resolve in accordance with their own composition, i.e., by their charge and not by the size and charge of the peptide-SDS micelle (32).

It is surprising that the antiserum recognized an intense band with an apparent size of 7 kDa in infected cells (and not in uninfected cells) (see Fig. 1, lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8). This band was not p15E, as seen from the lanes stained with a mixture of anti-R and anti-p15E. The band is designated the palmR peptide. In virions produced by these infected cells (collected over a period of 20 h) no palmR peptide was observed (compare lanes 2 and 3). This was not due to low virus production, as seen in Fig. 1, lanes 5 and 6, where the samples were immunostained with anti-gp70. An approximately 60-fold-higher virus amount was necessary in order to observe palmR peptide in virions (data not shown). We also analyzed 1 mg (protein amount) of MoMLV obtained from the NCI, and we did not observe palmR peptide (data not shown). In neither case was a band corresponding to synR peptide seen.

The envelope proteins were previously found in a 1:4 ratio to Gag proteins (14). According to the molecular masses, approximately 0.5% of the virion protein is therefore R peptide. With a detection level of the synthetic R peptide of approximately 5 μg, it is thus necessary to add approximately 1 mg of virion protein to a gel for its detection.

The sensitivities of the synR peptide and palmR peptide are apparently very different. The nature of palmR peptide found in cells was examined further. If, as the results indicate, the palmR peptide is a form of the R peptide, a co- or posttranslational modification of the cellular R peptide must occur.

The palmR peptide is membrane associated.

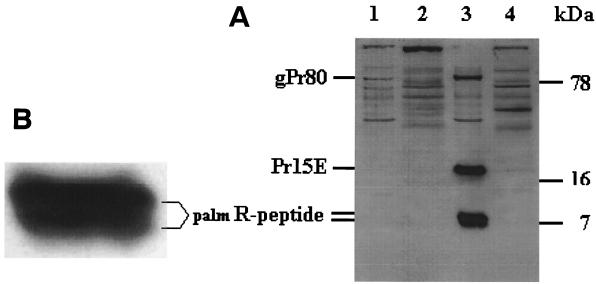

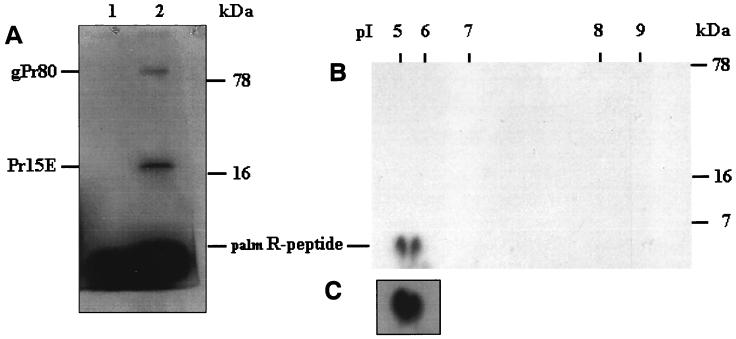

The cellular localization of the palmR peptide was investigated, in order to get insight into its nature. In Fig. 2A, the results from a subcellular fractionation of infected NIH 3T3 cells are shown. palmR peptide was found exclusively in the membrane fraction together with the transmembrane protein, Pr15E (compare lanes 3 and 4). This is surprising since the R peptide of MoMLV was found by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis to be hydrophilic (14). It should be noted that the broad palmR-peptide band consisted of two close bands, seen more clearly in Fig. 2B (a magnification of the palmR-peptide bands in Fig. 2A, lane 3). This doublet is striking since the R peptide has been found in virions in two variants (p2E and p2E*) by Henderson et al. (14), who suggested these to be genetic variants.

FIG. 2.

Subcellular fractionation of infected NIH 3T3 cells. Sucrose gradient fractionation was done on cell homogenates, followed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-R peptide by using the ECL detection system. (A) Lanes: 1, NIH membrane; 2, NIH cytoplasm; 3, infected NIH membrane; 4, infected NIH cytoplasm. Equalized cytoplasm and membrane amounts were added. (B) Magnification of the R peptide resolved in Fig. 2A, lane 3.

Cross-linking studies on membrane fragments, isolated from infected NIH 3T3 cells, were performed with the lipid soluble homobifunctional chemical cross-linker DSP (Fig. 3). At concentrations of >0.5 mM, nearly complete cross-linking of the palmR-peptide band and Pr15E to complexes of high molecular mass was observed. Since DSP does not act on soluble proteins (40), the cross-linkage of the palmR peptide indicates that it is located in or close to the membrane, a finding in agreement with its membrane copurification. The 50-kDa band seen at 0.05 mM DSP is possibly the Pr15E trimer.

FIG. 3.

Cross-linking with DSP of membrane fragments from infected NIH 3T3 cells. Membrane fragments were isolated, followed by cross-linking with DSP in the noted concentrations. Samples treated with DTT cleaving the disulphide bond in the cross-linker are indicated (+). The samples were electrophoresed and immunoblotted with anti-R peptide by using the ECL detection system.

The palmR peptide is palmitoylated.

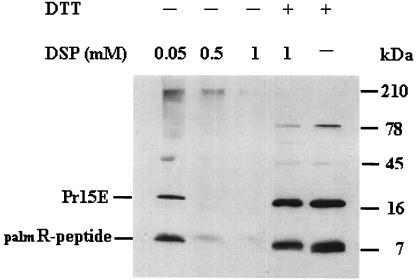

Labeling of the MoMLV envelope protein with [3H]palmitic acid resulted in bands corresponding to the envelope precursor gPr80env and Pr15E (Fig. 4A). A band most likely corresponding to the palmR peptide was also seen, but it was unfortunately partly covered by free palmitic acid or lipids containing palmitic acid (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 1 and 2). Further separation was necessary.

FIG. 4.

Labeling of the R peptide by [3H]palmitic acid. (A) Labeled cell lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-R peptide subjected to gel loading buffer containing DTT prior to Tricine-SDS-PAGE. Lanes: 1, NIH lysate; 2, infected NIH lysate. (B) Labeled infected NIH 3T3 cell lysate immunoprecipitated with anti-R peptide before isoelectric focusing and subsequent Tricine-SDS-PAGE. The preparation of the isoelectrical focusing gel is described in Materials and Methods. (C) Similar experiment to that described for panel B (only the lower left quadrant is shown).

From the sequence, the R peptide has an estimated pI of 5.35, whereas the pKa for palmitic acid is 4.9 (22). Labeled samples were separated by 2D-gel electrophoresis. As shown in Fig. 4B, 2D gels of palmitic acid-labeled infected cells resulted in two closely localized spots at the expected pI of between 5 and 6 and an apparent molecular mass of 7 kDa, which demonstrated that the R peptide was labeled by [3H]palmitic acid. In Fig. 4C, the results from a similar labeling experiment illustrate, in a more pronounced manner, that the left spot ran slower in the second dimension than the right one, corresponding to the doublet seen in Fig. 2B. Pr15E and gPr80env were not detectable in Fig. 4B, presumably because the detection limit is higher in the 2D gel than in the 1D gel (Fig. 4A).

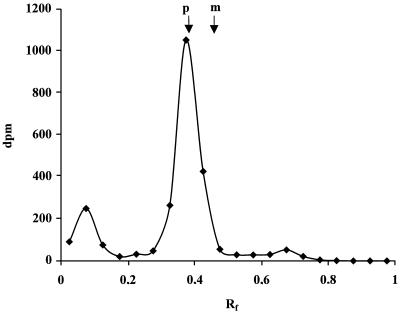

Identification of the label incorporated into palmR peptide as palmitic acid.

Identification of the fatty acid incorporation into proteins is important, since [3H]palmitic acid can be converted into other fatty acid species of different chain lengths or saturations before it is attached to the acyl protein (32). We used a reversed-phase TLC assay. The palmR peptide from Fig. 4B was analyzed. In Fig. 5, the radioactivity from the hydrolyzed peptide is shown. Standards of palmitic and myristic acid peaked at Rf values of 0.38 and 0.47, respectively. This result thus shows that the majority of the label was incorporated into the palmR peptide as a palmitoyl group. (The small peak at Rf 0.1 might represent large lipids, e.g., polyisoprenoids known to carry sugars for the membrane-associated synthesis of glycoproteins.) When the two palmR-peptide spots from Fig. 4B were analyzed individually, the same results were obtained (data not shown). The finding that palmitic acid could be recovered shows that it was added by acylation and not subjected to interconversion to other fatty acids or to amino acids.

FIG. 5.

TLC analysis of the [3H]palmitic acid-labeled R peptide of MoMLV. As described in Materials and Methods, fatty acids from hydrolyzed labeled R peptide from infected NIH 3T3 cells were analyzed on an RP-18 TLC plate. Fractions were scraped off the plate, and each fraction was counted. The disintegrations per minute (dpm) were plotted against the Rf, which was defined as the distance from the origin to the fractions relative to the corresponding distance of the front (16 cm). The arrows indicate the relative migration of the two standards: [3H]palmitic acid (p) and [3H]myristic acid (m).

Palmitoylation of Pr15E and gPr80env observed in reducing gels is not bound by thioacylation.

The R peptide does not contain cysteine but does contain lysine, threonine, and tyrosine, to which palmitic acid could be coupled by an amide or oxy-ester bond. If palmitic acid is bound to the R peptide before cleavage, then Pr15E and possibly also gPr80env are labeled on the R-peptide tail. Palmitic acid is, however, also known to be bound to a cysteine residue in the membrane-spanning domain of p15E (48). Cysteine-bound palmitic acid was excluded in the experiment shown in Fig. 4, since DTT was used to reduce the samples. Furthermore, thio-ester bonds are labile, whereas amide and oxy-ester bonds are stabile in hydroxylamine at neutral pH (44). The gPr80env and Pr15E bands from Fig. 4A were cut out and treated with hydroxylamine. The remaining radioactivity levels in gPr80env and Pr15E were 451 and 661 dpm, respectively, compared to 218 and 92 dpm in the corresponding controls at the same locations of labeled uninfected cells. Fewer than 20 dpm were observed in the hydroxylamine washes. Thus, more than 95% of the radioactivity in the two proteins was stable in hydroxylamine, which shows that the radioactivity observed in Fig. 4A was not thio-ester bound. It should be noted that the observed label could be added through metabolic conversions, though this is unlikely since the label on the R peptide is bound by acylation.

DISCUSSION

Altogether, the results show that the palmR-peptide band is a derivative of the R peptide. It is detected by R-specific antiserum (recognizing Pr15E but not p15E), and it is present in infected cells. In virions it is also present, but only in small amounts. It resolves into two very close bands which have also been observed by HPLC analysis of MoMLV R peptide (designated p2E and p2E*, with the latter containing an extra alanine) (14). The palmR peptide must be a derivative, since it runs more slowly in gels than does the synthetic R peptide. It is palmitoylated, which explains its membrane association and its slower gel migration.

The different sensitivities in immunoblotting of the palmitoylated and synthetic R peptides can be explained by the different binding properties to nitrocellulose. In contrast to Pr15E, the R peptide is hydrophilic, as seen by its weak binding to hydrophobic (reversed-phase C18) columns (14). Binding of proteins to nitrocellulose occurs mainly by hydrophobic interactions and can be weak, especially for small peptides (25). Binding of the native hydrophilic R peptide is therefore expected to be weak. Palmitoylation of the hydrophilic R peptide will presumably create a strong hydrophobic binding and give a higher sensitivity.

Since we did not observe native R peptide in virions, immunoblotting onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (generally used for peptide mapping) was compared to that of nitrocellulose. In virus preparations, a band below the palmR peptide band was observed on the PVDF membrane (results not shown).

Which amino acid(s) in the R peptide the palmitic acid is linked to remains to be elucidated. In the absence of cysteines the fatty acid must either be bound by an ester linkage to threonine or tyrosine or by an amide linkage to lysine (35) (or if it is added after cleavage possibly to the terminal amino group). The palmitoylation of lysine has been proposed for the early region 1B 176R protein of human adenovirus type 5 (21).

A general consensus signal, specifying the site of palmitoylation, is not known. For proteins belonging to the Ras family, it has been suggested that a cysteine followed by two aliphatic residues could function as the signal for palmitoylation (37). In Pr15E Friend murine leukemia virus, palmitoylation was demonstrated to occur on Cys-606 (corresponding to cysteine 630 in MoMLV), located close to the transmembrane domain (48), which actually is followed by isoleucine and leucine. Aliphatic amino acids in the R peptide are neighboring both the lysine and threonine, which together with a bound fatty acid will make up a strong hydrophobic domain. It should be mentioned that the shown non-S acylation on Pr15E and gPr80env does not exclude the possibility that thio-esterification also occurs on Pr15E (48).

The present results give some insights into the formation and fate of the palmitoylated R peptide. The finding that Pr15E and gPr80env also were palmitoylated on other atoms than sulfur suggests that the R-peptide palmitoylation occurs before gPr80env and Pr15E cleavage. Based on cell fractionation of Semliki Forest virus-infected BHK cells, Berger and Schmidt (4) have proposed that the fatty acyltransferase is located in the ER. Since gPr80env is cleaved in the cis compartment of the Golgi (10), the finding of labeled gPr80env suggests a lipid modification in the ER or Golgi. More data is needed, however, in order to show whether all R-peptide palmitoylation occurs before cleavage and whether all Pr15E and gPr80env molecules are palmitoylated on their R peptides.

Pr15E has been shown by pulse-labeling to have a turnover time in cells of ca. 1 h (12), with which the present intensities of Pr15E in cells and virions agree (Fig. 1 and calculations not shown). It has previously been suggested that the R cleavage occurs after budding (14); however, the present results show that the R peptide at least in the palmitoylated form is cleaved before budding.

Since both p15E and R peptide (irrespective of its form) are created by a cleavage of Pr15E, their total amounts must equal (assuming no degradation), which has been shown to be true in virions (14). However, this does not appear to be the case in cells, where only minute amounts of p15E are present (Fig. 1 and reference 12). In the present study, we looked at the situation after 20 h of virus production. The cellular Pr15E amount was lower than the viral Pr15E amount, which again only comprised approximately one-tenth of the viral p15E amount (Fig. 1 and reference 12). The cellular (palmitoylated) R peptide has an intensity approximately equal to that of the cellular Pr15E (Fig. 1). According to the relative amounts discussed above, the cellular R peptide apparently only comprises a small percentage of the viral p15E and thus viral (unpalmitoylated) R peptide.

It is interesting that the cellular p15E has a much lower intensity than the cellular palmitoylated R peptide (Fig. 1). This difference shows that p15E after the cleavage in cells is rapidly moved to the virions, whereas the palmitoylated R peptide remains in cells, a finding which indicates that it possibly has a function there. However, the results do not show whether (i) only a fraction of the Pr15E is cleaved in the cell (represented by the cellular palmitoylated R peptide) or (ii) all Pr15E is cleaved in the cell. In the first case, the palmitoylated R peptide is accumulated (dead end) in cells, whereas in the second case it slowly would move to the virions with approximately the same turnover time as that for the cellular Pr15E. In the latter case, a depalmitoylation of R peptide during entry into virions must occur.

A transient existence of the palmitoylated form was suggested by others (32a). MoMLV was propagated in SC-1 cells. MoMLV from these cells showed considerable amounts of the 7-kDa R peptide; these amounts decreased after prolonged incubation.

The membrane association of the palmitoylated R peptide is presumably important for its function. Since the palmitoylated R peptide was seen in cells but basically not in virions, it apparently operates before or during budding. Palmitoylated R peptide may thus function as a transport signal or in the control of conformational changes or the budding process.

Transport signal.

The apparent palmitoylation at an early point after Env synthesis fits with the transport signal model, thus bringing the Env complex to the plasma membrane. If so, the R peptide is not needed after virus budding. Late, the sorting in polarized epithelial cells of HIV-1 and MoMLV was investigated (19). To confer polarized basolateral budding in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells, at least one crucial membrane-proximal intracytoplasmic tyrosine residue, Tyr-622 (residue 6 in the R peptide), in MoMLV was needed. If this tyrosine is palmitoylated then lipid modification appears to have a role in compartmentalization.

Control of conformational changes.

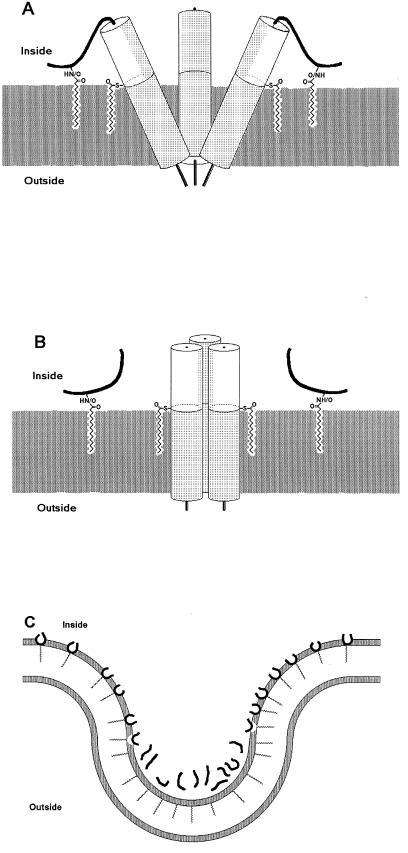

A palmitoylated R tail of Pr15E will most likely attach to the membrane as the free palmitoylated peptide does. It might thus tilt the Pr15E molecule in the membrane, whereby it consequently can control the conformation of the Pr15E trimer (9) on the outside of the membrane. After cleavage, p15E can erect into its fusogenic form. As such it can act as a safety catch, which is in agreement with previous results (28, 29) showing that R-truncated Pr15E is fusogenic. The model for this is shown in Fig. 6A and B.

FIG. 6.

Models for the function of the palmitoylated R peptide. (A and B) Conformational control through the membrane (dark gray) of the p15E trimer. (A) Before cleavage the membrane-linked R peptide (bold line) is thought to tilt Pr15E, which upon cleavage can rise. The cylinders represent α-helical domains with hydrophobic faces in light gray. Both the palmitic acid at Cys-597 and the one at the R peptide are shown. (B) After cleavage the rise of the p15E molecules might be energized by the binding of the hydrophobic faces to each other. (C) Membrane curvature control during virion budding. The hydrophobic part of the membrane with its polar sides (gray) is shown. At the brim of the place of budding, the membrane curves outward, which might be helped by a high head-to-tail ratio of the palmitoylated R peptide. In the virions, the curvature is inward, showing why a high head-to-tail ratio is disadvantageous and explaining the need for depalmitoylation of the R peptide.

In order to tilt Pr15E in the membrane, the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of p15E need to be rigid, which fits with the suggestions that the domains are α-helical (47). The cytoplasmic α-helix is amphiphatic, with hydrophobic faces (47), which can bind the p15E molecules together and thus erect them. Chimeras in which the cytoplasmic tail of the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) transmembrane protein was replaced by the MoMLV cytoplasmic tail in the entire form or the R-truncated form were made (47). The R-peptide tail was then able to inhibit SIV propagation in HeLa T4 cells. This ability could be due to its palmitoylation (Fig. 6A and B), which would be independent of the virus (e.g., SIV), but not of the cell type used for virus propagation.

Control in the budding process.

The palmitoylated R peptide can possibly control budding by creating membrane curvature. Seen from the cytoplasm, budding needs an outward membrane curvature at the brim of the site of budding. As an amphophilic molecule the palmitoylated R peptide has a high head group area (17) compared to the hydrophobic tail (the palmitic acid), presumably generating outward curvature of the membrane. Later, during budding, the membrane curvature reverses, where a high head group area is a disadvantage, thus explaining a depalmitoylation of the R peptide. This model is shown in Fig. 6C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames G F-L, Nikaido K. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of membrane proteins. Biochemistry. 1976;15:616–623. doi: 10.1021/bi00648a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen K B, Nexø B A. Entry of murine retrovirus into mouse fibroblasts. Virology. 1983;125:85–98. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battini J-L, Heard J M, Danos O. Receptor choice determinants in the envelope glycoproteins of amphotropic, xenotropic, and polytropic murine leukemia viruses. J Virol. 1992;66:1468–1475. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1468-1475.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger M, Schmidt M F G. Protein fatty acyltransferase is located in the rough endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett. 1985;187:289–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonatti S, Migliaccio G, Simons K. Palmitoylation of viral membrane glycoproteins takes place after exit from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:12590–12595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadwallader K A, Paterson H, Macdonald S G, Hancock J F. N-terminally myristoylated Ras proteins require palmitoylation or a polybasic domain for plasma membrane localization. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4722–4730. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casey P J. Protein lipidation in cell signaling. Science. 1995;268:221–224. doi: 10.1126/science.7716512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamberlain J P. Fluorographic detection of radioactivity in polyacrylamide gels with the water-soluble fluor, sodium salicylate. Anal Biochem. 1979;98:132–135. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90716-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fass D, Harrison S C, Kim P S. Retrovirus envelope domain at 1.7 Å resolution. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:465–469. doi: 10.1038/nsb0596-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitting T, Kabat D. Evidence for a glycoprotein “signal” involved in transport between subcellular organelles. Two membrane glycoproteins encoded by murine leukemia virus reach the cell surface at different rates. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:14011–14017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebhardt A, Bosch J V, Ziemiecki A, Friis R R. Rous sarcoma virus p19 and gp35 can be chemically crosslinked to high molecular weight complexes. J Mol Biol. 1984;174:297–317. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green N, Shinnick T M, Witte O, Ponticelli A, Sutcliffe J G, Lerner R A. Sequence-specific antibodies show that maturation of Moloney leukemia virus envelope protein involves removal of a COOH-terminal peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6023–6027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hausmann J, Ortmann D, Witt E, Veit M, Seidel W. Adenovirus death protein, a transmembrane protein encoded in the E3 region, is palmitoylated at the cytoplasmic tail. Virology. 1998;244:343–351. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson L E, Sowder R, Copeland T D, Smythers G, Oroszlan S. Quantitative separation of murine leukemia virus protein by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography reveals newly described gag and env cleavage products. J Virol. 1984;52:492–500. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.2.492-500.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hensel J, Hintz M, Karas M, Linder D, Stahl B, Geyer R. Localization of the palmitoylation site in the transmembrane protein p12E of Friend murine leukemia virus. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232:373–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.373zz.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter E, Swanstrom R. Retrovirus envelope glycoproteins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;157:187–253. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75218-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Israelachvili J N, Marcelja S, Horn R G. Physical principles in membrane organization. Q Rev Biophys. 1980;13:121–160. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500001645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivanova L, Schlesinger M J. Site-directed mutations in the Sindbis virus E2 glycoprotein identify palmitoylation sites and affect virus budding. J Virol. 1993;67:2546–2551. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2546-2551.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lodge R, Delamarre L, Lalonde J-P, Alvarado J, Sanders D A, Dokhélar M-C, Cohen E A, Lemay G. Two distinct oncornaviruses harbor an intracytoplasmic tyrosine-based basolateral targeting signal in their viral envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1997;71:5696–5702. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5696-5702.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maeda T, Balakrishnan K, Mehdi S Q. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of plasma membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;731:115–120. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(83)90404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGlade C J, Tremblay M L, Yee S-P, Ross R, Branton P E. Acylation of the 176R (19-kilodalton) early region 1B protein of human adenovirus type 5. J Virol. 1987;61:3227–3234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3227-3234.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran J B, Burczynski F J, Cheek R F, Bopp T, Forker E L. Protein binding of palmitate measured by transmembrane diffusion through polyethylene. Anal Biochem. 1987;167:394–399. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mumby S M. Reversible palmitoylation of signaling proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naeve C W, Williams D. Fatty acids on the A/Japan/305/57 influenza virus hemagglutinin have a role in membrane fusion. EMBO J. 1990;9:3857–3866. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nyholm L, Ramlau J. Nitrocellulose membranes as solid phase in immunoblotting. In: Bjerrum O J, Heegaard N H H, editors. Handbook of immunoblotting of proteins. Vol. 1. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1988. pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Farrell P H. High-resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Philipp H C, Schroth B, Veit M, Krumbiegel M, Herrmann A, Schmidt M F G. Assessment of fusogenic properties of influenza virus hemagglutinin deacylated by site-directed mutagenesis and hydroxylamine treatment. Virology. 1995;210:20–28. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ragheb J A, Anderson W F. pH-independent murine leukemia virus ecotropic envelope-mediated cell fusion: implications for the role of the R peptide and p12E TM in viral entry. J Virol. 1994;68:3220–3231. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3220-3231.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rein A, Mirro J, Haynes J G, Ernst S M, Nagashima K. Function of the cytoplasmic domain of a retroviral transmembrane protein: p15E-p2E cleavage activates the membrane fusion capability of the murine leukemia virus Env protein. J Virol. 1994;68:1773–1781. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1773-1781.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Resh M D. Myristylation and palmitoylation of Src family members: the fats of the matter. Cell. 1994;76:411–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Resh M D. Regulation of cellular signalling by fatty acid acylation and prenylation of signal transduction proteins. Cell Signal. 1996;8:403–412. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Schmidt G, Willemann S. M.S. thesis. Copenhagen, Denmark: Royal Danish School of Pharmacy; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt M F G. The transfer of myristic and other fatty acids on lipid and viral protein acceptors in cultured cells infected with Semliki forest virus and influenza virus. EMBO J. 1984;3:2295–2300. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt M, Schmidt M F G, Rott R. Chemical identification of cysteine as palmitoylation site in a transmembrane protein (Semliki forest virus E1) J Biol Chem. 1988;263:18635–18639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt M F G. Fatty acylation of proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;988:411–426. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(89)90013-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schultz A, Rein A. Maturation of murine leukemia virus Env proteins in the absence of other viral proteins. Virology. 1985;145:335–339. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sefton B M, Buss J E. The covalent modification of eukaryotic proteins with lipid. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:1449–1453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.6.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srinivas R V, Compans R W. Membrane association and defective transport of spleen focus-forming virus glycoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:14718–14724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka K, Nagayama Y, Nishihara E, Namba H, Yamashita S, Niwa M. Palmitoylation of human thyrotropin receptor: slower intracellular trafficking of the palmitoylation-defective mutant. Endocrinology. 1998;139:803–806. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.2.5911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tezapsidis N, Li H-C, Ripellino J A, Efthimiopoulos S, Vassilacopoulou D, Sambamurti K, Toneff T, Yasothornsrikul S, Hook V Y H, Robakis N K. Release of nontransmembrane full-length Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein from lumenar surface of chromaffin granule membranes. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1274–1282. doi: 10.1021/bi9714159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veit M, Schmidt F G, Rott R. Different palmitoylation of paramyxovirus glycoproteins. Virology. 1989;168:173–176. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90417-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veit M, Schmidt M F G. Timing of palmitoylation of influenza virus hemagglutinin. FEBS Lett. 1993;336:243–247. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80812-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veit M, Reverey H, Schmidt M F G. Cytoplasmic tail length influences fatty acid selection for acylation of viral glycoproteins. Biochem J. 1996;318:163–172. doi: 10.1042/bj3180163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veit M, Schmidt M F G. Membrane targeting via protein palmitoylation. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;88:227–239. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-487-9:227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witte O N, Wirth D F. Structure of the murine leukemia virus envelope glycoprotein precursor. J Virol. 1979;29:735–743. doi: 10.1128/jvi.29.2.735-743.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang C, Spies C P, Compans R W. The human and simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein transmembrane subunits are palmitoylated. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9871–9875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang C, Compans R W. Analysis of the cell fusion activities of chimeric simian immunodeficiency virus-murine leukemia virus envelope proteins: inhibitory effects of the R-peptide. J Virol. 1996;70:248–254. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.248-254.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang C, Compans R W. Palmitoylation of the murine leukemia virus envelope glycoprotein transmembrane subunits. Virology. 1996;221:87–97. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]