Abstract

Background

The impact of recurrent angioedema can be severely debilitating and remains difficult to quantify. Several standardized patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), including the Angioedema Activity Score (AAS), Angioedema Quality of Life (AE-QoL) questionnaire, and Angioedema Control Test (AECT), have been developed and translated into different languages. However, these PROMs have yet to be validated in Chinese individuals, and their correlations in the Chinese population remain unknown.

Objective

Our aim was to validate the Chinese versions of the AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT and assess their intercorrelations.

Methods

A prospective cohort of 118 Chinese patients with recurrent angioedema at the Angioedema and Urticaria Centre of Reference and Excellence in Hong Kong completed the traditional Chinese versions of the AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT. We analyzed the reliability and validity of these PROMs and their correlations with each other as well as with generic PROMs.

Results

The Chinese AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.920, 0.976, and 0.832, respectively; McDonald ω = 0.972, 0.977, and 0.901, respectively). Confirmatory factor analysis for the AE-QoL questionnaire showed an acceptable fit with the 4-dimensional model (comparative fit index = 0.869; Tucker-Lewis index = 0.842). The AECT showed significant correlations with both the AAS and AE-QoL questionnaire (ρ = –0.750 and –0.456 respectively [both P < .05]). The AE-QoL questionnaire was moderately correlated with certain domains of generic PROMs such as the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: General Health, version 2.0, and the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, version 2 (all ρ < 0.60).

Conclusion

The Chinese AE-QoL questionnaire, AAS, and AECT are valid and reliable tools for use with Chinese patients. More validated tools should be made available to improve patient care and research for all patients with angioedema globally.

Key words: Angioedema, Chinese, chronic urticaria, hereditary angioedema, patient-reported outcome measures, validation

Introduction

Recurrent angioedema is characterized by recurring swelling of subcutaneous and submucosal tissues caused by increased vascular permeability and fluid accumulation in interstitial tissue. This can be mediated by bradykinin (eg, hereditary angioedema [HAE]) or mast cell mediators (eg, chronic spontaneous urticaria [CSU]).1 Regardless of its mechanism, recurrent angioedema can be severely debilitating and even life-threatening. Furthermore, unpredictability and fear of future attacks lead to severe impairments in health-related quality of life (HRQoL).2,3 As of now, there are no reliable biomarkers for measuring or monitoring disease activity, impact, or control. Patient-reported outcomes remain crucial and are recommended in angioedema guidelines.4,5 Different patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), such as the Angioedema Activity Score (AAS), the Angioedema Quality of Life (AE-QoL) questionnaire, and Angioedema Control Test (AECT), have been developed and validated to standardize disease assessment.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Currently, none of these have been validated for Chinese individuals, and their interrelationship in this population is unknown.3 To address this issue, we validated the Chinese versions of the AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT in a population of Chinese patients with CSU and HAE along with recurrent angioedema.

The traditional Chinese versions of the AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT were validated at the Immunology Clinics of Queen Mary Hospital/University of Hong Kong, which is the only accredited angioedema and urticaria center of reference and excellence in the territory.11,12 A total of 118 patients (95 with CSU and 23 with HAE) with recurrent angioedema participated; 91 (77.1%) were female, with median age of 50 years (range 21-89 years) (Table I). All of the patients with CSU had both angioedema and hives. No patients with acquired angioedema due to C1-inhibitor deficiency were included. Patients completed the Chinese AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT, as well as the Short Form 12-item Health Survey, version 2 (SF-12v2) and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: General Health, version 2.0 (WPAI-GH). In the SF-12v2, the 8 domains were categorized as either physical or mental health components.13 All patients provided informed consent. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Female sex, no. (%) | 91 (77.1) |

| Age (y), median (min-max) | 50 (21-89) |

| Han Chinese ethnicity, no. (%) | 116 (98.3) |

| Diagnosis | |

| CSU, no. (%) | 95 (80.5) |

| Both angioedema and hives | 95 (100.0) |

| Angioedema only | 0 (0.0) |

| HAE due to C1-inhibitor deficiency, no. (%) | 23 (19.5) |

| Type I | 20 (87.0) |

| Type II | 3 (13.0) |

| Acquired angioedema due to C1-inhibitor deficiency, no. (%) | 0 (0.0) |

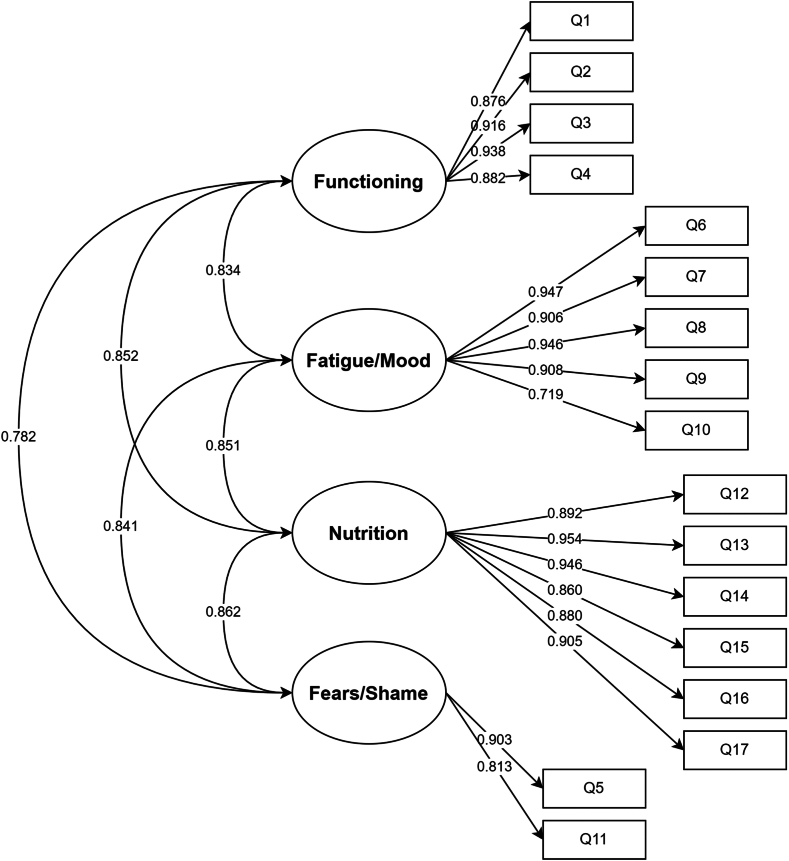

Structured translations with cognitive debriefings, followed by assessment of internal consistency, construct/convergent validity, and Spearman correlation between the Chinese AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT were performed (Fig 1 and see the Supplementary Methods in the Online Repository at www.jaci-global.org).

Fig 1.

Factor structure of the Chinese AE-QoL questionnaire.

Results and discussion

The Chinese AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT demonstrated excellent reliability, with Cronbach α and McDonald ω values of 0.920, 0.976, and 0.832 and 0.972, 0.977, and 0.901, respectively (Table II). The AE-QoL questionnaire, as assessed by confirmatory factor analysis, showed construct validity, with an acceptable fit with the 4-dimensional model: comparative fit index = 0.869; Tucker-Lewis index = 0.842; and root mean square error of approximation = 0.164 (95% CI = 0.144-0.184). The factor loadings of all items were greater than 0.40 (Fig 1). The AAS and AE-QoL questionnaire demonstrated convergent validity, as demonstrated by strong, statistically significant correlation with question 1 of the AECT (ρ = –0.991; P < .001) for the former and question 2 of the AECT (ρ = –0.633; P < .001) for the latter.

Table II.

Internal consistency of the Chinese AE-QoL questionnaire, AECT, and AAS

| PROM | Cronbach α | McDonald ω |

|---|---|---|

| AAS | 0.920 | 0.972 |

| AECT | 0.832 | 0.901 |

| AE-QoL questionnaire domains | ||

| Functioning | 0.945 | 0.945 |

| Fatigue/mood | 0.945 | 0.952 |

| Fears/shame | 0.965 | 0.965 |

| Nutrition | 0.848 | 0.849 |

| AE-QoL questionnaire total | 0.976 | 0.977 |

The correlation of the AAS and the AECT was strong and significant (ρ = –0.750; P < .001), whereas there was no correlation with the AE-QoL questionnaire (ρ = 0.276; P < .05 [Table III]). The correlation of the AE-QoL questionnaire and the AECT was moderate and significant (ρ = –0.45; P < .05).

Table III.

Spearman correlation between the Chinese AE-QoL questionnaire, AECT, and AAS

| PROM | AE-QoL questionnaire | AAS | AECT |

|---|---|---|---|

| AE-QoL questionnaire | — | 0.276 | –0.456∗ |

| AAS | 0.276 | — | –0.750∗∗∗ |

| AECT | –0.456∗ | –0.750∗∗∗ | — |

P < .05

P < .001.

The Spearman correlation between the AE-QoL and the 2 generic PROMs (the SF-12v2 and WPAI-GH) is shown in Table IV. Among the physical health components, only role limitations due to physical health demonstrated a moderate negative correlation with the AE-QoL questionnaire (ρ = –0.427). Two mental health components, namely, vitality and social functioning, demonstrated moderate negative correlations with the AE-QoL questionnaire (in the case of vitality, ρ = –0.486; in the case of social functioning, ρ = –0.556). In contrast, 3 of the 4 scales of the WPAI-GH exhibited a weak-to-moderate positive correlation with AE-QoL questionnaire as follows: presenteeism (ρ = 0.355), loss of work productivity (ρ = 0.364), and activity impairment (ρ = 0.416).

Table IV.

Spearman correlation of the Chinese AE-QoL questionnaire with the SF-12v2 and WPAI-GH

| Component | Spearman ρ | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Components of the SF-12v2 | ||

| Physical health components | ||

| Physical functioning | –0.365 | .087 |

| Role limitations due to physical health | –0.427 | .042 |

| Pain | –0.129 | .559 |

| General health | 0.004 | .987 |

| Mental health components | ||

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 0.026 | .908 |

| Vitality | –0.486 | .019 |

| Emotional well-being | –0.330 | .125 |

| Social functioning | –0.556 | .006 |

| Components of the WPAI-GH | ||

| Absenteeism | 0.156 | .176 |

| Presenteeism | 0.355 | .002 |

| Work productivity loss | 0.364 | .001 |

| Activity impairment | 0.416 | <.001 |

Boldface denotes correlations reaching statistical significance.

Both mast cell– and bradykinin-mediated angioedema can profoundly affect patients’ physical and psychosocial well-being.14, 15, 16 As Chinese is the world’s most widely spoken native language, availability of validated Chinese PROMs will be crucial to benefit more patients with angioedema and clinical research in Chinese-speaking regions. PROMs that have been structurally translated and validated across different languages would also enable cross-cultural and ethnic comparisons of angioedema outcomes, which would benefit the entire global angioedema community.

Consistent with the findings of previous studies in other populations, we demonstrated that all 3 angioedema PROMs and their subscales showed excellent reliability.17,18 Although the Chinese AECT was significantly correlated with both the AAS and the AE-QoL questionnaire, there was no significant correlation between the AAS and the AE-QoL questionnaire. This may be due to the difference between each PROM’s measurement period (4-weeks for the AECT and the AE-QoL questionnaire vs daily for the AAS). Another explanation may be that HRQoL (measured by the AE-QoL questionnaire) is more affected by parameters outside symptomatology and function (measured by the AAS). Factors such as stress and anxiety in anticipation of future attacks (as well as their psychosocial consequences), individual perception of disease, side effects, and cost of medications have been shown to affect HRQoL but may not be adequately captured by the AAS alone.14,19, 20, 21, 22 Indeed, these 3 distinct PROMs aim to assess different, albeit related, concepts. Therefore, we advocate simultaneous use of the 3 PROMS to better reflect the overall disease burden.

As expected, worse scores on the AE-QoL questionnaire were correlated with the presenteeism, work productivity loss, and activity impairment components of the WPAI-GH. However, there was no significant correlation with absenteeism. As the WPAI-GH is a generic PROM that measures only a relatively short period (the past week), it may miss patients who do not experience severe attacks (leading to absenteeism) in the past week. Similarly, the AE-QoL questionnaire was also correlated with several components of the SF-12v2, namely, role limitations due to physical health, vitality, and social functioning, but not with the remaining components. Again, this reflects the fact that the AE-QoL questionnaire is likely more specific for patients with angioedema and captures disease-specific factors affecting HRQoL that are missed by generic PROMs.

Future studies to further refine the use of the Chinese versions of AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT are under way. Utilizing the same questionnaires in the same individual will also help eliminate individual bias. Therefore, it will be interesting to see whether longitudinal changes in symptomatology or treatment are reflected in serial assessments conducted by using these new translated PROMs in Chinese patients. Furthermore, although we validated the AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT among native Chinese in Hong Kong, further studies are required to investigate whether the findings remain consistent with those for other Chinese patients from different regions (such as Mainland China, Taiwan, and other Chinese-speaking countries).

This study has some limitations. Patients with uncommon angioedema presentations, such as CSU with angioedema but no hives or acquired angioedema due to C1-inhibitor deficiency, were not included in this study.23 Also, patients with less severe disease might not be referred and thus not reach our services. We were unable to perform a subgroup analysis owing to the relatively small size of the sample of patients with HAE in our study. Future studies will be of use to further investigate the psychometric properties of these Chinese PROMs among different subgroups of patients with angioedema.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the Chinese AAS, AE-QoL questionnaire, and AECT are valid and reliable tools for use with Chinese patients with angioedema. We recommend that more validated tools be made available to improve patient care and research for all angioedema patients globally.

Disclosure statement

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: M. Maurer reports serving as a speaker and/or advisor for and/or having received research funding from Allakos, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Astria, Bayer, BioCryst, Celldex, Celltrion, CSL Behring, Evommune, GSK, Ipsen, Kalvista, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Menarini, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Moxie, Noucor, Novartis, Pharvaris, Sanofi/Regeneron, Septerna, Takeda, Teva, Third HarmonicBio, ValenzaBio, Yuhan Corporation, and Zurabio outside the present work. K. Weller reports being a speaker and/or advisor for and/or having received research funding from Biocryst, CSL Behring, MOXIE, Novartis, Sanofi, Takeda, and Uriach outside the present work. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project benefited from the global network of angioedema centers of reference and Excellence (https://acare-network.com/) and urticaria centers of reference and excellence (www.ga2len-ucare.com).

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Lima H., Zheng J., Wong D., Waserman S., Sussman G.L. Pathophysiology of bradykinin and histamine mediated angioedema. Front Allergy. 2023;4 doi: 10.3389/falgy.2023.1263432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong J.C.Y., Li P.H. Large-bowel obstruction from hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:e41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm2303943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honda D., Li P.H., Jindal A.K., Katelaris C.H., Zhi Y.X., Thong B.Y., Longhurst H.J. Uncovering the true burden of hereditary angioedema due to C1-inhibitor deficiency: A focus on the Asia-Pacific region. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;153:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2023.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maurer M., Magerl M., Betschel S., Aberer W., Ansotegui I.J., Aygoren-Pursun E., et al. The international WAO/EAACI guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema-the 2021 revision and update. Allergy. 2022;77:1961–1990. doi: 10.1111/all.15214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li P.H., Au E.Y.L., Cheong S.-L., Chung L., Fan K.I., Ho M.H.K., et al. Hong Kong-Macau severe hives and angioedema referral pathway. Front Allergy. 2023;4 doi: 10.3389/falgy.2023.1290021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weller K., Groffik A., Magerl M., Tohme N., Martus P., Krause K., et al. Development and construct validation of the angioedema quality of life questionnaire. Allergy. 2012;67:1289–1298. doi: 10.1111/all.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weller K., Magerl M., Peveling-Oberhag A., Martus P., Staubach P., Maurer M. The Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE-QoL) - assessment of sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2016;71:1203–1209. doi: 10.1111/all.12900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weller K., Donoso T., Magerl M., Aygoren-Pursun E., Staubach P., Martinez-Saguer I., et al. Validation of the Angioedema Control Test (AECT)-a patient-reported outcome instrument for assessing angioedema control. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:2050–2057.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weller K., Donoso T., Magerl M., Aygoren-Pursun E., Staubach P., Martinez-Saguer I., et al. Development of the Angioedema Control Test-a patient-reported outcome measure that assesses disease control in patients with recurrent angioedema. Allergy. 2020;75:1165–1177. doi: 10.1111/all.14144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weller K., Groffik A., Magerl M., Tohme N., Martus P., Krause K., et al. Development, validation, and initial results of the Angioedema Activity Score. Allergy. 2013;68:1185–1192. doi: 10.1111/all.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maurer M., Aberer W., Agondi R., Al-Ahmad M., Al-Nesf M.A., Ansotegui I., et al. Definition, aims, and implementation of GA(2) LEN/HAEi angioedema centers of reference and excellence. Allergy. 2020;75:2115–2123. doi: 10.1111/all.14293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maurer M., Metz M., Bindslev-Jensen C., Bousquet J., Canonica G.W., Church M.K., et al. Definition, aims, and implementation of GA(2) LEN urticaria centers of reference and excellence. Allergy. 2016;71:1210–1218. doi: 10.1111/all.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam C.L., Tse E.Y., Gandek B. Is the standard SF-12 health survey valid and equivalent for a Chinese population? Qual Life Res. 2005;14:539–547. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0704-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fouche A.S., Saunders E.F., Craig T. Depression and anxiety in patients with hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savarese L., Bova M., Maiello A., Petraroli A., Mormile I., Cancian M., et al. Psychological processes in the experience of hereditary angioedema in adult patients: an observational study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:23. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01643-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goncalo M., Gimenez-Arnau A., Al-Ahmad M., Ben-Shoshan M., Bernstein J.A., Ensina L.F., et al. The global burden of chronic urticaria for the patient and society. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:226–236. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morioke S., Takahagi S., Kawano R., Fukunaga A., Harada S., Ohsawa I., et al. A validation study of the Japanese version of the Angioedema Activity Score (AAS) and the Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE-QoL) Allergol Int. 2021;70:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanya M., Watt M., Shahraz S., Kosmas C.E., Rhoten S., Costa-Cabral S., et al. Content validation and psychometric evaluation of the Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire for hereditary angioedema. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2023;7:33. doi: 10.1186/s41687-023-00576-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong J.C.Y., Chiang V., Lam K., Tung E., Au E.Y.L., Lau C.S., Li P.H. Prospective study on the efficacy and impact of cascade screening and evaluation of hereditary angioedema (CaSE-HAE) J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:2896–2903.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong J.C.Y., Chiang V., Lam D.L.Y., Lee E., Lam K., Au E.Y.L., Li P.H. Long-term prophylaxis for hereditary angioedema: initial experiences with garadacimab and lanadelumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol Glob. 2023;2 doi: 10.1016/j.jacig.2023.100166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castaldo A.J., Jervelund C., Corcoran D., Boysen H.B., Christiansen S.C., Zuraw B.L. Assessing the cost and quality-of-life impact of on-demand-only medications for adults with hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2021;42:108–117. doi: 10.2500/aap.2021.42.200127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen E.R., Aagaard L., Bygum A. Real-life experience with long-term prophylactic C1 inhibitor concentrate treatment of patients with hereditary angioedema: Effectiveness and cost. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116:476–477. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kan A.K.C., Wong T.T.H., Chiang V., Lau C.S., Li P.H. Chronic spontaneous urticaria in Hong Kong: clinical characteristics, real-world practice and implications for COVID-19 vaccination. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2023;15:32. doi: 10.4168/aair.2023.15.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.