Abstract

Insurer or self-insured employer’s plans are increasingly using copay accumulator, copay maximizer, and alternative funding programs (AFPs) to reduce plan spending on high-priced prescriptions. These programs differ in their structure and impact on patient affordability but typically decrease the insurer or self-insured employer’s financial responsibility for high-priced drugs and increase the complexity of specialty medication access for patients. The aim of this primer is to describe the structure of copay accumulator, copay maximizer, and AFPs to improve understanding of these cost-shifting strategies and help clinicians and patients navigate medication access and affordability issues to minimize treatment delays or non-initiation.

In recent years, the rising cost of prescription drugs has become a significant concern for many insurers, employers, patients, and health care providers. By 2021, specialty medications (italicized words are defined in the Glossary) accounted for less than 20% of retail prescriptions and 10% of nonretail prescriptions yet equated to 42% to 70% of spending.1 To promote cost-effective medication use, insurance plans and self-insured employers (hereafter called insurers) are tasked with developing cost containment strategies while promoting optimal medication outcomes. These utilization management strategies are often effective in minimizing prescription costs but can create barriers for patients to receive appropriate therapies.2-4 Common tools to contain prescription costs include the use of prior authorizations (PAs) before covering a medication, restricted or tiered formularies, step therapy requirements, and setting quantity limits.5,6 Tiered formularies are particularly useful tools for plans to steer patients toward the use of the drug that is the best value when there are multiple treatment options. For example, a plan may place a generic drug on a low cost-sharing tier and a similar brand-name drug on a high cost-sharing tier. Alternatively, plans may make some high-priced drugs more expensive to their enrollees by placing them on high cost-sharing tiers even when lower-priced alternatives are unavailable.

For patients with commercial insurance, pharmaceutical manufacturers may use copay support and other patient assistance programs to reduce cost-sharing requirements for patients, effectively bypassing formulary designs imposed by plans. This form of manufacturer assistance may benefit individual patients, but it undermines the actuarial structure of the insurance plan and can increase prescription drug spending on brand-name drugs and health insurance costs to insurance beneficiaries more broadly.7 This is one reason that manufacturer coupons and direct copayment support are explicitly disallowed in the Medicare Part D program.8

Recently, insurers have implemented new strategies to reduce prescription spending by shifting costs away from the insurer to other stakeholders, including patients, manufacturers (who set the initial drug price), and, in some cases, charitable foundations that provide copayment assistance funds for qualifying patients. Insurance cost-shifting initiatives through copay accumulators, copay maximizers, and alternative funding programs (AFPs) are now common among commercial insurance plans. As of 2022, it is estimated that 39% of commercially insured beneficiaries were enrolled in plans with copay accumulators, 41% with copay maximizers, and 12% with AFPs.9-11 These cost-shifting programs have created new barriers that patients and the care team must navigate to ensure timely access to treatment. This primer describes the structure and impact of copay accumulators, copay maximizers, and AFPs on commercially insured patients and includes insights from health system pharmacists on how care teams can assist patients in navigating these programs to ensure timely medication access and initiation. A patient case is used throughout to apply the different programs to practice. For simplicity, the examples do not account for the use of additional medications or other health services that would affect a patient meeting their deductible or maximum annual out-of-pocket (OOP) costs limit.

Patient Case for Copay Adjustment Programs

J.W. is a 34-year-old patient with a history of moderate to severe Crohn disease. After undergoing multiple small bowel resections, J.W. presents to the clinic for further management of recurrent disease and is prescribed a specialty medication with a list price of $2,000 per month. J.W. has commercial insurance with an annual deductible of $4,000, a maximum annual OOP limit of $8,000, and a monthly insurance premium of $250. After his deductible is met, J.W. is responsible for 40% of the drug’s price (plan pays 60%). J.W. learns that he can apply for manufacturer copay funds for his specialty medication of up to $8,000 for the year, with $0 OOP for these fills.

TRADITIONAL PLAN

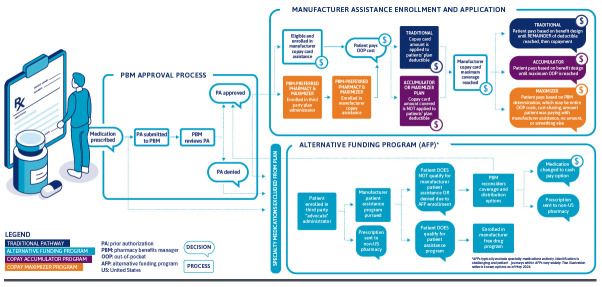

Plan Overview. When a pharmacy receives a prescription for a medication, a claim is sent to the patient’s insurance (if applicable), which alerts the pharmacy if a PA is required. If the PA is approved, the patient’s OOP costs are set based on their plan benefit design (Figure 1). Commercially insured patients may request a copay card from the manufacturer, if available and eligible, to offset high OOP costs, which are common for specialty medications. The copay card is processed by the pharmacy, and the final OOP cost is calculated based on the amount noted on the manufacturer copay card. Traditionally, the amount covered by the copay card would be applied to the patient’s deductible and annual maximum OOP cost. The copay card is used until the maximum allowable amount of funds, determined by the manufacturer, has been reached. Once copay card funds are exhausted, a patient must pay their plan’s set cost-sharing amount (any remaining deductible and/or copayments or coinsurance up to the OOP maximum).

FIGURE 1.

Determining Patient Costs by Insurance Plan’s Cost-Shifting Strategy

Case Example: Traditional Plan

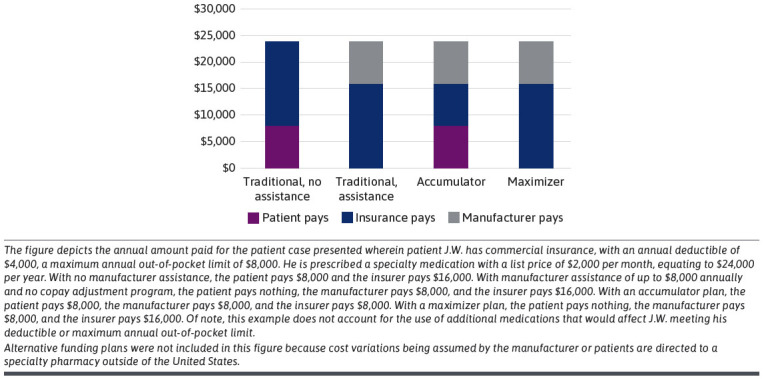

No manufacturer assistance. J.W. fills his medication each month without manufacturer copay assistance, paying $2,000 per fill for the first 2 months of treatment (until reaching his prespecified deductible) and $800 per month thereafter (40% of the drug’s price) until reaching the $8,000 OOP maximum (Table 1). Under this arrangement, the insurer pays $16,000 and the patient pays $8,000 for 12 months of treatment (Figure 2).

TABLE 1.

Patient Case Cost Breakdown by Cost-Shifting Strategy

| Insurance type | Month | Manufacturer pays | Insurance pays | Patient pays a | Maximum out-of-pocket remaining ($8,000 max) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional, no manufacturer assistance | January | $0 | $0 | $2,000 | $6,000 |

| February | $0 | $0 | $2,000 | $4,000 | |

| March | $0 | $1,200 | $800 | $3,200 | |

| April | $0 | $1,200 | $800 | $2,400 | |

| May | $0 | $1,200 | $800 | $1,600 | |

| June | $0 | $1,200 | $800 | $800 | |

| July | $0 | $1,200 | $800 | $0 | |

| August | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| September | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| October | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| November | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| December | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| Total | $0 | $16,000 | $8,000 | — | |

| Traditional, with manufacturer assistance | January | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | $6,000 |

| February | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | $4,000 | |

| March | $800 | $1,200 | $0 | $3,200 | |

| April | $800 | $1,200 | $0 | $2,400 | |

| May | $800 | $1,200 | $0 | $1,600 | |

| June | $800 | $1,200 | $0 | $800 | |

| July | $800 | $1,200 | $0 | $0 | |

| August | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| September | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| October | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| November | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| December | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| Total | $8,000 | $16,000 | $0 | — | |

| Copay accumulator program | January | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | $8,000 |

| February | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| March | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| April | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| May | $0 | $0 | $2,000 | $6,000 | |

| June | $0 | $0 | $2,000 | $4,000 | |

| July | $0 | $1,200 | $800 | $3,200 | |

| August | $0 | $1,200 | $800 | $2,400 | |

| September | $0 | $1,200 | $800 | $1,600 | |

| October | $0 | $1,200 | $800 | $800 | |

| November | $0 | $1,200 | $800 | $0 | |

| December | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | |

| Total | $8,000 | $8,000 | $8,000 | — | |

| Copay maximizer program | January | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | $8,000 |

| February | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| March | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| April | $2,000 | $0 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| May | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| June | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| July | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| August | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| September | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| October | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| November | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| December | $0 | $2,000 | $0 | $8,000 | |

| Total | $8,000 | $16,000 | $0 | — |

Alternative funding plans were not included in this table because cost variations being assumed by the manufacturer or patients are directed to a specialty pharmacy outside of the United States.

a Commercial insurance with an annual deductible of $4,000, a maximum annual out-of-pocket limit of $8,000. After his deductible is met, the patient is responsible for 40% of the drug’s price (plan pays 60%).

FIGURE 2.

Patient Case Scenario: Amount Paid by Entity for Each Cost-Shifting Strategy

Manufacturer assistance. J.W. obtains a manufacturer copay card with $8,000 of funds available for the year. Because J.W. has an OOP maximum of $8,000, he pays only the amount dictated by the copay card ($0 per month) because the patient has adequate funds available on his copay card that can cover the OOP maximum (Table 1). The manufacturer pays $8,000, the insurer pays $16,000, and the patient pays $0 (Figure 2).

Patient Perspective. Financial strain can occur for patients with high-deductible traditional health plans who either exhaust the maximum allowable amount on a manufacturer copay card before meeting their deductible or do not have access to or enroll in a manufacturer copay card. High-deductible plans (ie, deductible of at least $1,400 for individuals and $2,800 for families) are common among patients on high-cost drugs—a survey of 600 patients by the Arthritis Foundation found that 41% were enrolled in high-deductible plans.12 Since 2015, the average deductible of popular insurance plans offering mid-range coverage has doubled from $2,556 up to $5,338 in 2023.13-15 High-deductible plans may be more attractive to patients and employers because of the lower monthly premiums; however, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) allows these plans to set a patient’s deductible equal to their OOP maximum (ACA limits the amount that people must pay for health care every year), which was up to $9,100 for an individual in 2023.13,16 Furthermore, it is currently projected that the ACA maximum OOP limit is growing faster (122%) than wages and salaries (83% growth).16 The average deductible amount for 2023 is much higher at smaller firms ($2,434) compared with larger firms ($1,478).17 Patients who use specialty medications are more likely to face the full amount of their plan’s deductible and may be limited in their ability to afford their treatments.

COPAY ACCUMULATOR PROGRAMS

Program Overview. Copay accumulators are programs used by insurance plans to help manage costs by redirecting manufacturer copay assistance funds from the patient to the insurance plan.7,18 In these programs, commercially insured patients are allowed to use copay assistance from manufacturers, but the amount paid by manufacturers when patients use copay cards does not apply to patient deductibles or OOP maximums set by the health plan (Figure 1). Once a patient has exhausted copay assistance funds, they remain responsible for their entire deductible (minus the cost-sharing amount set by manufacturers for patients using the card) and cost sharing up to their original OOP maximum. Thus, insurance plan spending in this scenario is reduced by the amount of manufacturer copay assistance, as well as the patient’s full deductible payment and additional cost sharing until the OOP maximum is met.

Case Example: Copay Accumulator Program. J.W. obtains the same manufacturer copay card with $8,000 of available funds, which covers the full price of the medication for the first 4 fills (Table 1). After the copay card funds are exhausted (4 months), J.W. must pay the $2,000 copay per month without manufacturer assistance until his $4,000 deductible is met, then 40% of the $2,000 copay ($800) until his $8,000 maximum OOP is reached (Table 1). The manufacturer pays $8,000, the insurer pays $8,000, and the patient pays $8,000 in this example (Figure 2).

Patient Perspective. Copay accumulator programs allow patients to have low OOP cost until the funds available on the copay card are exhausted. Any manufacturer-paid amounts are not counted toward patient OOP spending. Once copay card funds have been depleted, patients are responsible for the entire deductible and cost-sharing amount based on a plan’s benefit design. The patient’s OOP responsibility drastically increases from the typical manufacturer copay amount of $0 or $5 per fill to hundreds or thousands of dollars per fill until the maximum OOP amount is met. This is particularly challenging for patients with high-deductible plans. The inability to afford medications may lead to missed doses, discontinuation, or therapy abandonment.19

COPAY MAXIMIZER PROGRAMS

Program Overview. Copay maximizer programs enable insurance companies to “maximize” available manufacturer-supplied copay cards and minimize patient OOP costs. Insurance plans using maximizer programs require patients to enroll with a third party for specified medications prior to filling them at the pharmacy. The third-party calculates the maximum amount of manufacturer copay assistance throughout the year and advises that the plan set a patient’s monthly copay to use the maximum amount of manufacturer copay assistance.20 This copay may be divided evenly throughout the year, or the plan may set higher copays at the beginning of the year to exhaust the funds from the manufacturer in fewer medication fills. Under copay maximizer programs, copay support supplied by the manufacturer does not apply toward the patient’s deductible or OOP maximum. Once all manufacturer assistance is exhausted, the maximizer program manually adjusts the patient’s copay to an amount determined by the pharmacy benefits manager. This amount is often set at the same amount that the patient was paying with manufacturer assistance, though it is possible that it could be set higher or lower, depending on the plan or pharmacy benefits manager (Figure 1). If the plan does not appropriately adjust the copay amount, the patient may end up with unexpected high OOP costs or the pharmacy may need to contact the plan to advise them to adjust the copay amount.

Case Example: Copay Maximizer Program. J.W. is informed that he must enroll in a third-party program to assist him with affording his medications. After providing his financial information, the third-party program helps him obtain a manufacturer copay card. The maximum allowable copay assistance from the manufacturer is $8,000, and J.W. pays $0 using the copay card. After 4 fills of the medication ($2,000 each), the copay card funds are exhausted. The third-party program then manually adjusts the patient’s OOP cost for the remaining copays and communicates to the pharmacy that J.W.’s OOP cost for the specialty medication should remain $0 (Table 1). The manufacturer pays $8,000, the insurer pays $16,000, and the patient pays $0 OOP in this example (Figure 2). However, none of the funds paid by the manufacturer are used to reduce plan deductibles or OOP limits that would be paid by J.W. for other services used during the plan year.

Patient Perspective. Patients enrolled in maximizer programs may face delays to accessing medication due to the additional step of enrolling in a third-party program. Additionally, high OOP costs and patient confusion can occur if the third-party program does not correctly manipulate the copay to a lower amount determined by the plan once copay funds are depleted. Adequate coordination among the maximizer program, the third party, and the specialty pharmacy must occur once manufacturer funds are exhausted. Many times, an override (to adjust the copay amount) must be requested by the pharmacy, leading to delayed medication access and/or billing issues for the patient. As with copay accumulator programs, copay maximizer programs do not count copay assistance toward the patient’s deductible, so although the patient may have no financial burden related to the drug, there may still be significant OOP implications for paying for other health care services.

ALTERNATIVE FUNDING PROGRAMS

Program Overview. AFPs are typically used by “self-funded” employer plans seeking to shift costs of specialty medications away from the insurance plan and employer. AFPs carve out all specialty medications as “nonessential”; therefore, patients do not have coverage for specialty drugs under their insurance benefits. In these cases, patients appear to be underinsured instead of uninsured because they have prescription coverage, but it excludes specialty drugs specified by the AFP. AFPs vary in the process by which they attempt to secure financial assistance for the cost of the medication. Most often, when a patient attempts to fill a specialty medication, the provider’s office may receive a denial (typically after submitting a PA) stating the prescribed medication is not covered. The denial letter typically does not provide a list of preferred alternatives or may indicate all specialty medications are excluded from the patient’s plan with no path to approval (ie, appeal). In doing so, the plan participant appears underinsured for specialty medications. Patients are then required to either pay the full cost of the medication or use a third-party “advocate” administrator program that seeks to obtain free medication most often through manufacturer patient assistance programs or through international (non-United States [US]-based pharmacies) (Figure 1). Patient assistance programs typically set income criteria to ensure resources are reserved for patients demonstrating a financial need. If the patient does not meet income guidelines or is denied because the manufacturer identifies their enrollment in an AFP (increasingly common), the insurance may then reconsider and approve the PA request, send the referral to an international pharmacy or attempt to have the medication changed to a cash pay option. Patients may also appeal to their human resources department to have the medication covered. If the patient is successful in obtaining manufacturer patient assistance program approval through the AFP, the AFP charges the employer an estimated fee of 30% based on the estimated “savings” from not paying for the medication.11,21

Case Example: Alternative Funding Program. J.W. starts a new job with new prescription drug benefits. J.W.’s prescriber submits a PA request to his new insurance plan for the medication he has been maintained on over the last 6 months. J.W. and his prescriber’s clinic receive a denial letter stating medication coverage is denied with no formulary alternative options listed. J.W.’s clinic pharmacist calls the phone number on the letter to clarify the appeal process and is told this plan does not cover any specialty medications; however, the plan uses a third-party “advocate” group to assist patients with accessing medications. Meanwhile, J.W. receives a phone call from the “advocate” group, which assures him that he will still be able to receive his medication at no cost from the drug’s manufacturer. For the next several weeks, J.W. communicates with the “advocate” group to supply his financial information and complete necessary forms to submit a patient assistance program application to the manufacturer. Simultaneously, his provider’s office facilitates obtaining temporary supply from the manufacturer to prevent a lapse in therapy. Several weeks later, J.W. receives a letter in the mail from the patient assistance program stating his request for free drug is denied because he is financially overqualified. J.W. contacts the clinic panicked and confused, and the clinic pharmacist calls the advocate group to discuss reconsideration of coverage. The next few weeks consist of multiple phone calls, emails, and escalations from the clinic to the “advocate” group before the medication is approved. Upon approval, the clinic is notified that a prescription must be sent to a Canadian pharmacy to be covered. The Canadian pharmacy is not an option to choose in the electronic medical record, so the prescriber must print, manually sign, and fax the prescription, potentially leading to future transmission errors and delays. Unfortunately, it takes several additional weeks before the pharmacy fills and internationally ships the medication. Knowing the reauthorization process each year will follow the same pattern and timeline if J.W.’s employer continues to contract with an AFP, J.W. is encouraged by his team to discuss his experience with his human resources department and encourage them to switch to a plan that does not involve an AFP.

Because the outcome is unpredictable and highly patient/medication dependent, it is unclear in AFPs how much each stakeholder pays. If the AFP is successful in enrolling the patient in the manufacturer’s patient assistance program, the manufacturer pays the full cost of the medication, the patient pays nothing, and the AFP charges the employer a fee based on the amount of manufacturer funds obtained. Therefore, AFPs are incentivized to identify and enroll as many patients as possible in manufacturer patient assistance programs to increase their fees.

Patient Perspective. AFPs can add significant confusion, stress, and medication access delays. The AFP process begins with the patient receiving a denial of their medication with no clear path forward. They are told the only way to access this medication is by enrolling with a third-party advocate for assistance. To comply with the advocate’s process of enrolling in a patient assistance program, patients must agree to share their financial and private health information with this external group. Patients are often confused by this process as the details were not made clear when they originally enrolled in their health plan. This multistep process can take months, and patients may ultimately be forced to switch to an alternate medication entirely (if available) or forgo treatment owing to the complexity and burden of this process.

Implications of Cost-Shifting Strategies

As the prevalence of cost-shifting programs increases, manufacturers have responded by decreasing or eliminating the amount of copay assistance available to patients whose plans use accumulators, maximizers, or AFPs. Several manufacturers specifically outline these adjustments in the Terms and Conditions section for their copay assistance program. For example, if a copayment accumulator or maximizer program is identified for products in Janssen’s anti-inflammatory portfolio, the available copay funds drop from $20,000 to $6,000 annually.22,23 Additionally, some manufacturers have implemented strategies to prevent insurance plans from determining who provided payment for a medication so that copay funds may count toward a patient’s maximum OOP even if a plan uses accumulators or maximizers to try to manage prescription drug spending. For example, funds from debit cards issued directly to patients and rebate programs are not accessible to the insurance plan. This can reduce potential insurer savings from adopting cost-shifting strategies.

Some manufacturers and patient assistance programs have stopped providing assistance to patients who have been identified as having an AFP. AFPs help patients appear underinsured so they may obtain assistance from manufacturers’ charitable free drug programs, which reduces available funds for patients who are truly uninsured or underinsured and challenges their sustainability.

Each of the 3 cost-shifting strategies has significant implications for patients, prescribers, manufacturers, and insurers. One shared characteristic of these strategies is that they can be challenging to identify by patients at the time of benefit enrollment. The terms “accumulator,” “maximizer,” and “AFP” are often avoided when describing plan benefits. Thus, even if patients and their care team were more aware of these benefit designs, they may not have the option to avoid plans that place specialty drugs under these arrangements.

Recognizing the potential high costs to consumers imposed by copay accumulator programs upon the exhaustion of manufacturer copay assistance, many state legislators have attempted to block their use, with 16 states and 1 US territory enacting laws requiring manufacturer assistance be applied toward deductibles and 6 more prohibiting copay accumulator programs when no generic alternatives exist.13 Bipartisan legislation was introduced in Congress in November 2021 (“Help Ensure Lower Patient Copays Act,” HR 5801) that would prohibit copay accumulator programs in individual and employer insurance plans, but it has not been passed. Federal legislation or regulatory policies will be needed to make a significant impact, as self-funded plans are generally exempt from state insurance mandates owing to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act.13

Evidence related to the effects of copay accumulator programs is limited, including their impacts on patient medication use and on patient, plan, and enrollee/employer spending. Two recent analyses found evidence to suggest that copay accumulator programs are associated with lower medication adherence and persistence. For example, in one study researchers observed higher medication adherence and persistence in states that banned copay accumulator programs compared with states that allowed such programs.24 Another study evaluated the impact of copay accumulator programs on usage patterns of autoimmune specialty drugs before and after implementation of copay accumulator programs, finding lower fill rates, higher discontinuation, and lower adherence for patients after copay accumulators were implemented.25

Copay accumulator programs clearly help reduce pharmacy spending for insurers. Therefore, some may argue that without these programs, costs would be shifted to patients through higher premiums. One recent analysis demonstrated that copay accumulator adjustment bans have not changed average premiums.26 However, state analyses of proposed fiscal impact for legislation requiring copay support to count toward patient deductibles and OOP maximums have indicated that such legislation would increase health care spending and insurance premiums in the short run.27-29 It is important to note, however, that such estimates may not consider potential long-run savings for improving patient health through increased medication access and improved adherence.

Acknowledging the potential for treatment disruption for patients in high-deductible plans whose OOP costs increase after manufacturer assistance is exhausted, many insurers have chosen to use maximizer rather than accumulator programs. Legislation to date has not targeted copayment maximizer programs. Maximizer programs attempt to maintain low OOP costs for patients using copayment assistance while extracting the full amount of manufacturer assistance, reducing plan spending. Maximizer programs and AFPs can increase workload for the health care team as they help to navigate medication access by assisting patients with enrolling in third-party programs. Despite the additional efforts and potential delays, these programs do not result in the same potential increases in OOP spending when compared with copayment accumulator programs and are thus not as financially burdensome for consumers.

AFPs are entirely unique from accumulators and maximizers by the nature of carving out all specialty medications and charging fees to the self-funded plans when patients use their services. The use of AFPs by employers has increased from 6% (2021) to 14% (2022).11 AFPs are attractive for self-funded plans because employers collect premiums directly from employees and keep any money remaining if the annual health care spending remains lower than anticipated.30,31 By contracting with an AFP, employers are told their employees will still have access to high-cost medications through manufacturer PAPs, at little to no cost to the employer or patient/employee.32 From an employer perspective, AFPs are marketed as a means to mitigate the rise in health care costs associated with specialty medication without impacting the patient/employee’s care. However, the true benefit for plans that use AFPs is unknown because the fees charged to the plan may also be high and dependent on how much manufacturer assistance is obtained. Several ethical and legal considerations of these programs have also been proposed, including Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 and Internal Revenue Service compliance issues.32-34 There is also significant concern that AFPs divert the limited manufacturer charitable resources from their intended recipients—patients who are truly uninsured or underinsured.32,33

A recent survey of employers and insurance plans revealed that 68% do not believe AFPs are a sustainable solution.21 Another survey of 50 employers cited that only 30% of respondents felt knowledgeable about AFPs, 20% were actively monitoring the performance of AFPs, and 68% were concerned about the possible diversion of resources intended for patients with a true need.21 However, 40% agreed that AFPs provide a viable option for employers attempting to control health care spending.

Unfortunately, the AFP model uses loopholes to obtain free medication from the manufacturer originally intended to help some of the most financially vulnerable patients.9,10 The future of AFPs is unclear; however, there is growing concern that AFP administrative barriers are not sustainable, may lead to significant delays for patients receiving the therapies they require, or may prevent them from accessing treatment altogether.32,35 In May 2023, the pharmaceutical company AbbVie filed a lawsuit against Payer Matrix, an AFP, citing that they exploited AbbVie’s charitable assistance program; the results of this suit are pending.36 Additionally, the legality and safety of sourcing medications from non-US pharmacies is unclear. With limited, if any, benefits and significant risks and downstream challenges associated with AFPs, patients, payers, care providers, and manufacturers are aligned in their concern about the growth and use of AFPs.

Recommendations for the Care Team

The care team plays an important role in helping patients access prescribed therapies. Specialty medications are often prescribed for chronic conditions that can have significant morbidity and mortality consequences if left untreated. We provide recommendations for patient education and care team actions to assist care teams and patients navigating these cost-shifting strategies in Table 2. These include calculating the range of costs that a patient may face, depending on coverage, encouraging patients to carefully review benefit design of plans that are available to them, to advise patients to contact the care team if costs are higher than expected or coverage is denied.

TABLE 2.

Recommendations to Care Teams to Navigate Cost-Shifting Strategies

| Patient education | |

|---|---|

| Provide a patient-level explanation of copay accumulator programs, copay maximizer programs, and AFPs |

|

| Provide educational resources |

|

| Set medication access timeline expectations |

|

| Encourage patients to understand benefits design at enrollment |

|

| Care team action | |

| Calculate and communicate patient cost of therapy with and without manufacturer assistance |

|

| Quickly respond to denials |

|

| Identify AFP enrollment |

|

| Coordinate care and communication |

|

| Care team action | |

| Remain current on legislation status related to these programs |

|

AFP = alternative funding program; OOP = out-of-pocket; PA = prior authorization; PAP = patient assistance program.

LIMITATIONS

This commentary was a multisite effort using perspectives from specialty pharmacists practicing in various clinical areas, including oncology, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, cystic fibrosis, and rheumatology, and health policy researchers with expertise in insurance benefit design. There is a paucity of data currently published on these programs; therefore, some of these statements are based on clinical experience. All patient cases represent actual cases experienced by one of the authors. Comprehensive research evaluating the impact of these programs on the health, well-being, and subsequent health care utilization and cost of affected benefits enrollees is required to provide data to help guide programs/policies.

Conclusions

High-cost specialty therapies present affordability challenges for insurance plans and patients who are both trying to mitigate rising costs. Copay accumulators, copay maximizers, and AFPs are increasingly common in insurance benefit designs, particularly for high-priced specialty medications. These cost-shifting programs increase administrative workload for care teams and may limit patient access to medications. Many manufacturers have also reduced or eliminated patient assistance through copayment assistance or charitable funds for patients on plans using accumulators, maximizers, of AFPs. Specialty pharmacists, prescribers of specialty medications, and patients must be able to recognize and navigate these programs to ensure timely access to needed specialty medications. Insurers and employers should consider the risks and potential benefits of copay accumulator and maximizer programs and should clearly communicate the use of such programs in their benefit design during the plan’s open enrollment period. They should also be aware of the increased complexity that they introduce for some patients, including challenges with medication adherence for accumulator programs following exhaustion of manufacturer copay support. Furthermore, insurers and employers should re-evaluate AFPs given the potential for delays or non-initiation of drugs carved out under these programs.

Glossary

All definitions are adapted from the AMCP Managed Care Glossary, available at https://www.amcp.org/about/managed-care-pharmacy-101/managed-care-glossary

Adherence: The ability to take a medication or comply with a treatment protocol according to the prescriber’s instructions.

Commercial insurer: Health insurance provided, managed, and administered by a private company rather than the government.

Copay support (cards or coupons): Discount cards provided by pharmaceutical manufacturers to reduce patient cost share for prescription drugs, typically for a specified period of time.

Cost-sharing: A payment method in which a person is required to pay some portion of the costs associated with health care services/products.

Deductible: A fixed amount that an insured person must pay out-of-pocket before health care benefits become payable. Usually expressed in terms of an annual amount.

Medicare Part D: The outpatient prescription drug benefit for the Medicare program.

Out-of-pocket costs: The portion of payments for covered health services required to be paid by the member, including, copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles.

Patient assistance programs: Manufacturer-sponsored programs that provide financial assistance or free drug product (through donations) to low-income individuals to augment any existing prescription drug coverage.

Persistence: The act of taking a medication for the prescribed duration of time. Measured as the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy.

Premiums: The amount paid by the covered member, or on behalf of the covered member, to a health insurance carrier for providing coverage under a contract.

Prior authorization: A type of utilization management that requires health plan approval for members taking certain drugs for a claim to be covered under the terms of the medical or pharmacy benefit. Prior authorization promotes the use of medications that are safe, effective, and provide the greatest value.

Step therapy: A type of utilization management that requires the use of a safe, lower-cost drug first before a second drug that is usually more expensive is approved under the terms of the medical or pharmacy benefit; may be administered through a prior authorization.

Specialty medications: Any high-cost medication, including injectables, infused products, oral agents, or inhaled medications, which require unique storage/shipment and additional education and support from a health care professional. Specialty drugs offer treatment for serious, chronic, and life-threatening diseases and are covered under pharmacy or medical benefits. “Specialty Drug” does not have a unified regulatory definition.

Tiered formularies: A pharmacy benefit design that financially rewards patients for using generic and preferred drugs by requiring progressively higher copayments for progressively higher tiers.

Quantity limits: A type of utilization management that limits the amount of medication dispensed per fill to reduce waste and overuse.

REFERENCES

- 1.ASPE. Trends in Prescription Drug Spending, 2016-2021. Published 2022. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/88c547c976e915fc31fe2c6903ac0bc9/sdp-trends-prescription-drug-spending.pdf

- 2.Lenahan KL, Nichols DE, Gertler RM, Chambers JD.. Variation in use and content of prescription drug step therapy protocols, within and across health plans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(11):1749-57. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi DK, Cohen NA, Choden T, Cohen RD, Rubin DT.. Delays in therapy associated with current prior authorization process for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29(10):1658-61. doi:10.1093/ibd/izad012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah NB, Zuckerman AD, Hosteng KR, et al. . Insurance approval delay of biologic therapy dose escalation associated with disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68(12):4331-8. doi:10.1007/s10620-023-08098-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werble C. Formularies are tools used by purchasers to limit drug coverage based on favorable clinical performance and relative cost. Health Affairs. Published 2017. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20171409.000177/full/hpb_2017_09_14_formularies-1687871374910.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resneck JS Jr. Refocusing medication prior authorization on its intended purpose. JAMA. 2020;323(8):703-4. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuckerman AD, Schneider MP, Dusetzina SB.. Health insurer strategies to reduce specialty drug spending-copayment adjustment and alternative funding programs. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(7):635-6. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews M. Why Can’t Medicare Patients Use Drugmakers’ Discount Coupons? NPR. Published 2018. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/05/09/609150868/why-cant-medicare-patients-use-drugmakers-discount-coupon [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fein AJ. Copay Accumulator and Maximizer Update: Adoption Plateaus as Insurers Battle Patients Over Copay Support. Drug Channels. Published 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.drugchannels.net/2023/02/copay-accumulator-and-maximizer-update.html#:~:text=For [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pharmaceutical Strategies Group. 2023 Trends in Specialty Drug Benefits Report. Published 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.psgconsults.com/blog/psg-releases-highly-anticipated-trends-in-specialty-drug-benefits-report

- 11.Fein AJ. Employers Expand Use of Alternative Funding Programs—But Sustainability in Doubt as Loopholes Close. Drug Channels. Published 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.drugchannels.net/2023/05/employers-expand-use-of-alternative.html [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arthritis Foundation. Accumulator Adjustment Programs. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.arthritis.org/advocate/issue-briefs/accumulator-adjustment-programs

- 13.Hengst S. Discriminatory Copay Policies Undermine Coverage for People with Chronic Illness. The AIDS Institute. Published 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://aidsinstitute.net/documents/TAI-Report-Copay-Accumulator-Adjustment-Programs-2023.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health & Human Services: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Plan Year 2023 Qualified Health Plan Choice and Premiums in HealthCare.gov Marketplaces. Published 2022. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/cciio/resources/data-resources/downloads/2023qhppremiumschoicereport.pdf

- 15.Avalere. Plans with More Restrictive Networks Comprise 73% of Exchange Market. Published 2017. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://avalere.com/press-releases/plans-with-more-restrictive-networks-comprise-73-of-exchange-market

- 16.Rae M, Amin K, Cox C.. ACA’s Maximum Out-of-Pocket Limit Is Growing Faster Than Wages. Peterson-KFF. Published 2022. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/aca-maximum-out-of-pocket-limit-is-growing-faster-than-wages/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.KFF. 2023 Employer Health Benefits Survey. Published 2023. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2023-summary-of-findings/

- 18.Fein AJ. Copay Accumulators: Costly Consequences of a New Cost-Shifting Pharmacy Benefit. Drug Channels. Published 2018. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.drugchannels.net/2018/05/copay-accumulators-costly-consequences.html [Google Scholar]

- 19.The IQVIQ Institute. Medicine Spending and Affordability in the U.S. Published 2020. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-spending-and-affordability-in-the-us

- 20.Fein AJ. Four Reasons Why PBMs Gain As Maximizers Overtake Copay Accumulators. Drug Channels. Published 2022. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/02/four-reasons-why-pbms-gain-as.html [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blum K. ‘Alternative’ Model For Patient Assistance Draws Stakeholder Ire. Specialty Pharmacy Continuum. Published 2023. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.specialtypharmacycontinuum.com/Policy/Article/12-23/Alternative-Model-For-Patient-Assistance-Draws-Stakeholder-Ire/72048 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Tremfya withMe Savings Program Overview. Published 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.tremfyawithme.com/sites/www.tremfyawithme-v1.com/files/TREMFYA-withMe_Savings-Program-Web-Flashcard.pdf

- 23.Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Stelara withMe Savings Program Overview. Published 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.stelarawithme.com/sites/www.stelarawithme.com/files/stelara-savings-program-overview.pdf

- 24.Sheinson D, Patel A, Wong W.. PA-37: Patient Liability and Treatment Adherence/Persistence Associated with State Bans on Copay Accumulator Programs. Acad 2023 Annu Res Meet. Published online 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherman BW, Epstein AJ, Meissner B, Mittal M.. Impact of a co-pay accumulator adjustment program on specialty drug adherence. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(7):335-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The AIDS Institute. Copay Assistance Does Not Increase Premiums. Published 2023. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.theaidsinstitute.org/copays/copay-assistance-does-not-increase-premiums#:~:text=The

- 27.California Health Benefits Review Program. California Assembly Bill 874: Out-of-pocket Expenses. Published 2023. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://www.chbrp.org/sites/default/files/bill-documents/AB874/AB%20874%20-%20FINAL%20DRAFT%20%20%281%29.pdf

- 28.AHIP. SB 184, PRESCRIPTION COST AMENDMENTS. Published 2023. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://www.urs.org/documents/byfilename/@Public%20Web%20Documents@URS@External@FiscalNotes@PEHP@2023@SB184@@application@pdf/

- 29.North Dakota Legislation. FISCAL NOTE HOUSE BILL NO. 1413. Published 2023. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://ndlegis.gov/assembly/68-2023/regular/fiscal-notes/23-0392-01000-fn.pdf

- 30.UnitedHealthcare. What If Your Health Plan Paid You? This Funding Model Is Giving Small Businesses a Lifeline. Philadelphia. Published 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.phillymag.com/sponsor-content/alternate-funding-health-plan/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Health Care Administrators Association. What is Self Funding? Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.hcaa.org/page/selffunding

- 32.Optum. Alternative funding: Real savings or real problems? Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.optum.com/business/insights/pharmacy-care-services/page.hub.alternative-funding-savings-problems.html

- 33.Karlin-Smith S. Patient-Doc Task Force Building Legal Case Against Alternative Funding Programs. Pink Sheet: Citeline Regulatory. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://pink.citeline.com/PS149294/Patient-Doc-Task-Force-Building-Legal-Case-Against-Alternative-Funding-Programs [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vivio Health. ERISA and IRS Compliance Related Issues for Alternative Funding Programs. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://viviohealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Compliance-Issues-with-Alternative-Funding-V1.01.pdf

- 35.Sadid S, Niles A.. Alternative Funding Programs Affect Our Most Vulnerable Patient Populations. Pharmacy Times. Published 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/alternative-funding-programs-affect-our-most-vulnerable-patient-populations [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aimed Alliance. AbbVie v. Payer Matrix, LLC. Published 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://aimedalliance.org/alternative-funding-programs-litigation/