Abstract

Background:

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are among the leading causes of morbidity in the population. In low- and medium-income countries like India, there is a wide treatment gap for SUD. A multicentric study on the care pathways for SUD in India can help to understand service provision, service utilization, and challenges to improve existing SUD care in India.

Aim:

We aimed to map pathways to care in SUD. We compared the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients who first consulted specialized services versus other medical services.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study of consecutive, consenting adults (18–65 years) with SUD registered to each of the nine participating addiction treatment services distributed across five Indian regions. We adapted the World Health Organization’s pathway encounter form.

Results:

Of the 998 participants, 98% were males, 49.4% were rural, and 20% were indigenous population. Addiction services dominated initial (50%) and subsequent (60%) healthcare contacts. One in five contacted private for-profit healthcare. Primary care contact was rare (5/998). Diverse approaches included traditional healers (4–6%) and self-medication (2–8%). There was a 3-year delay in first contact; younger, educated individuals with opioid dependence preferred specialized services.

Conclusion:

There is a need to strengthen public healthcare infrastructure and delivery systems and integrate SUD treatment into public healthcare.

Keywords: Addiction treatment services, lower- and middle-income countries, mental health services, pathways to care (PTC), substance use disorders

INTRODUCTION

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are among the leading causes of morbidity in the 10–50 years age group.[1] Despite the high prevalence and morbidity, help-seeking for SUD is limited due to factors like stigma, low perceived need, poor awareness, and restricted accessibility, availability, and affordability of right-based, quality services.

Pathway to care (PTC) is the ‘sequence of contacts with individuals and organizations prompted by the distressed person’s efforts, and those of his or her significant others, to seek help as well as the help supplied in response to such efforts’.[2] Goldberg and Huxley proposed a framework for PTCs of patients with mental illness in the industrialized countries.[3] However, the World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborative Pathways Study revealed that in contrast to High-income countries (HICs), care pathways in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) like India differ significantly.[4,5]

The WHO Pathways Study and similar pioneering studies did not focus on SUD exclusively, yet they indicated the heterogeneous help-seeking patterns for SUD. A qualitative study in the United States identified pathways ranging from natural ‘recovery’ to utilization of in-patient and out-patient services for SUD treatment.[6] In 1999, a study revealed that British general physicians could diagnose only half of their patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD).[7] Hence, they needed training to assess and manage AUD cases. To overcome the treatment gap, Public Health England proposed ‘everybody’s job’ and ‘no wrong door’ to bring patients with SUD for treatment.[8] Mental healthcare and SUD care in HIC are generally medicalized or under judicial supervision.[9,10] While HICs aim for universal coverage, LMICs are facing socioeconomic, political, and cultural challenges.[11]

According to the National Mental Health survey, the treatment gap for AUD was up to 85% in India.[12] The National Drug Use Survey 2019 shared similar concerns.[13] India has a mixed healthcare system, with private sectors catering to nearly 70% of outpatient-based healthcare in India.[14] Although public healthcare is organized hierarchically, in practice, there are no restrictions over referral to the higher levels. A recent report highlighted disparities and differences between states in access, cost, quality of care, and health outcomes.[15] Historically, SUD treatment was separated from mainstream healthcare. The “Scheme for Prevention of Alcoholism and Substance (Drugs) Abuse” aimed to deliver treatment and rehabilitation for SUD by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). The “Drug De-addiction Programme” envisions delivering medical treatment for SUD through the public healthcare system, structurally separated from routine healthcare.[16] Finally, there is minimum access to harm reduction services.[17] Although, the Addiction Treatment Facility scheme integrated SUD treatment with routine public healthcare, its uptake, acceptability, and sustainability are not assessed.[18] The contribution of the private healthcare sector to SUD treatment in India has not been systematically studied. An isolated study shows that private healthcare has a significant stake in AUD treatment.[19] The complexities and challenges in the framework of the SUD service delivery in India present a unique opportunity to explore the characteristics of treatment-seeking in SUD.

Indian studies exploring the PTC in SUD showed psychiatric or addiction-related consultations were the first major contact for patients with SUD attending a tertiary center for treatment.[20,21,22,23] There are variations in help-seeking across treatment settings, the nature of the substance used, and places of study.[22,24,25,26] One study in southern India showed most patients with AUD followed an indirect pathway to reach psychiatric care; most of them were referred by medical practitioners.[24] A study on a predominantly alcohol-using population shows a long duration of untreated illness, help-seeking from faith healers, and poor illness awareness in both tribal and nontribal patients.[25] The community care center-based studies found a smaller percentage of patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) visited the community addiction treatment centers directly.[20,27] Patients with cannabis and OUDs usually start their consultation from psychiatric or addiction treatment setups. Still, the time lag between the onset of dependence and treatment-seeking is longer in natural opioid use.[22,27,28] These studies are from a single center, have fewer subjects, and include a specific SUD. The vast socioeconomic, cultural, and substance-related diversities across India emphasize a need to examine the pathways to SUD care with robust methodology. This can provide insights into the service provisions and service utilization, which can help us to improve the existing addiction treatment services.

Our study aimed to describe the PTC for patients with SUD who consulted (at least once) at a specialized addiction or mental health treatment facility. We also compared how the clinical and demographic characteristics differed between patients who first consulted mental health/addiction services and those who consulted other medical services.

METHODOLOGY

Design: We conducted a multicenter cross-sectional assessment of persons who sought help for SUD from any of the study sites during the study period.

Study setting: We approached ten public tertiary care medical or psychiatric centers with specialized addiction treatment facilities. Nine of these agreed to participate in the study. These institutes were chosen to capture the diversity across the country. There were two centers from North India (Chandigarh UT and Rohtak, Haryana), one from West India (Jodhpur, Rajasthan), one from Central India (Raipur, Chhattisgarh), four from East India (Bhubaneswar, Odisha; Patna, Bihar; Ranchi, Jharkhand; and Kalyani, West Bengal), and one from Northeast India (Tezpur, Assam). These centers provide healthcare to the neighboring states; hence, we expect wide sociodemographic, cultural, and substance use differences across sites. Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Assam have higher percentages of indigenous/tribal populations. The human development index (life expectancy, education, and per capita income) of Chandigarh and Haryana is higher than that of the rest of the areas.[29] The healthcare facilities and health outcomes vary across the sites. Alcohol is the most commonly used substance across the centers. Still, the centers in Chandigarh, Rohtak, and Tezpur cater to the states with the highest opioid use prevalence.[13] Including these centers can tap into the vast interregional differences in sociocultural aspects, substance use profiles, and healthcare infrastructure.

The institutional ethical committee of each institute approved the study protocol. The data collection was performed between April 2022 and February 2023, and study periods varied between each center due to the difference in time required to reach the critical number of samples.

Participants: We conducted a face-to-face interview with consecutive, consenting adult (18–65 years) patients with SUD registered to addiction treatment services. We excluded patients with only tobacco use disorder.

We excluded patients with dual diagnosis from the analysis, although they were included in the study. For the present report, we focused exclusively on the care-seeking pathways in patients with SUD. The reasons for preparing two reports for SUD and dual diagnosis are manyfold. First, care-seeking pathways differed significantly between these two groups. Combining these would have increased the heterogeneity and made the interpretation of our findings challenging. Second, healthcare contacts need to be redefined for patients with dual diagnosis. For instance, tertiary care mental health facilities with functional or structural (or both) integration of SUD treatment should be categorized as integrated care for the population with dual diagnosis. Integrated care would not have much relevance for patients with only SUD. Third, different care pathways have varied clinical/policy implications for patients with SUD and dual diagnosis.

A qualified psychiatrist diagnosed SUD, which was concurred by a consultant psychiatrist. See Supplementary Figure 1 (1.5MB, tif) for the detailed flowchart of the screening process.

Variables: Ours was an exploratory, descriptive study; hence, we had no dependent variables. We defined all public healthcare services per the national health policy (primary care, district hospital, emergency care) and specifically the addiction treatment services. The for-profit private healthcare was defined separately. We recorded not-for-profit NGO-based care as social care. We did not specify inpatient and outpatient services. We did not assess the direct or indirect treatment cost. Please see Supplementary Table 1 for the definition of specific healthcare services. In addition to routine healthcare, we included help-seeking from traditional healers, pharmacists, self-medication, and legally mandated treatment. To characterize our sample, we collected the demographic and clinical profiles of our study participants. Socioeconomic status was decided per the modified Kuppuswamy’s scale.[30] Rural versus urban distinction was made as per the 2011 census. The substance for which the patient sought index treatment was considered as the primary substance, and the rest of the substances were labeled as secondary substances. Health record was used for collecting information on medical illness. We examined whether any of these demographic and clinical characteristics were associated with a higher likelihood of help-seeking from mental health/addiction services versus general healthcare services.

Supplementary Table 1.

Glossary for the specific contacts of pathways to care for treatment of addictive disorders

| Nature of the Contact | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Addiction Treatment Services (SAT) | These are tertiary care centers funded by the federal government and are exclusively designated for the treatment of addictive disorders and their comorbidities. These centers have a multidisciplinary team of psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, nurses, and/or general internists. Outpatient and inpatient services are available at these healthcare services. Cenetrs from Chandigarh, Ranchi, and Tezpur are in this category. | |

| Mental Health Services with Specialized Addiction Treatment Services (MHSAT) | These centers are public-funded tertiary care general hospitals psychiatric units; these centers have specialized treatment facilities for addictive disorders and their comorbidities. They also have a multi-disciplinary clinical team. There are outpatient and inpatient services. The rest of the study sites represent this healthcare category. | |

| Public-funded Addiction Treatment Services (PFAT) | State-funded addiction clinics/opioid agonist treatment centers/detoxification centers can be co-located with district-level hospitals or structurally separate from other health services. They usually offer outpatient treatment. These health services may not have permanent psychiatrists. | |

| Mental Health Services (MHS) | These are public-funded psychiatric hospitals and medical colleges. Often, these centers lack specialty addiction services. | |

| Private Psychiatrist/Private addiction treatment center (PP/PAT) | Privately-funded, for-profit psychiatric clinic/psychiatric nursing home/addiction clinics/private psychiatry practitioners. The private addiction centers may or may not have accreditation. Private psychiatrists may not have adequate training to screen and treat people with SUD. | |

| Religious/Traditional Healers | Religious and native healing practices encompass various spiritual approaches. These practices are deeply rooted in the beliefs and traditions of various cultures and often involve rituals, ceremonies, and natural remedies. Some examples include faith healing, Ayurveda, etc., These practices may involve prayer, herbal remedies, rituals, etc., | |

| General Hospital | These are state-funded district-level hospitals providing secondary-level care. District hospitals may have psychiatrists but do not have a multidisciplinary team. Treatment is usually outpatient-based. | |

| Primary Health Centres | These outpatient-based healthcare services are at the block level (sub-district) and funded by the state. These do not have mental healthcare professionals. A doctor (with an undergraduate degree), nurse, and pharmacist are available at this level. There is no or minimal training for SUD screening and treatment at the undergraduate level in the Indian medical curriculum. | |

| Emergency Services | State-funded acute care services at the district hospital level. Undergraduate medical doctors are available at this level. | |

| Private Medical facilities | Are private for-profit enterprises involving general physicians and surgeons but not psychiatrists. | |

| Pharmacists | These are individual pharmacists who run local for-profit dispensaries. Many of them may not have formal pharmacy training. | |

| Social work | Not-for-profit NGOs operate integrated rehabilitation centers for addicts. They deliver psychosocial interventions, primarily by social workers. The federal government funds these centers. | |

| Self-medication | People with SUD can buy over-the-counter medications from local private pharmacies/drug stores. | |

| Criminal justice | The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act of India criminalizes drug use (and possession). The act has the provision of one-time immunity to people with SUD if they volunteer for treatment in a public-funded healthcare service. |

Tools: We used a semistructured proforma to record the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants.

We assessed the PTC by a semistructured interviewer-administered questionnaire based on the pathway encounter form developed for the WHO collaborative study.[4] This culture-neutral questionnaire was used for Indian patients with SUD with minor modifications, which we retained for this study.[20,27] The questionnaire records the nature of the treatment contacts, contact initiator, reasons for obtaining contacts, the interval between contacts, and treatment received.

All information was gathered by psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, and social workers, with at least 1 year of clinical experience in treating/helping people with SUD. The study investigators trained them.

All data were entered in real time on the Google form. AG and TM periodically checked for missing, incomplete, and incoherent entries, and such discrepancies were reported to the study sites for corrections.

Sample size: We did not perform power calculations because it was a descriptive and exploratory study. The collaborators in each center agreed to enrol at least 50 participants from each center or continue enrolment for three consecutive months. We included 998 enrolled participants in our final analysis, for whom at least one treatment contact detail was available.

Statistical analysis: We applied descriptive statistics for categorical and continuous variables. We used the Chi-square test for the comparison of categorical variables between the groups seeking psychiatric and addiction-related consultation (PAC) and those seeking other medical consultation (OMC) at the first contact. As the continuous variables were not normally distributed, we used the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test to compare continuous variables between PAC and OMC. The sociodemographic variables were available for 998 participants, while the clinical and contact-related variables were available for fewer subjects. We applied both descriptive and inferential statistics with the available data only as the dataset was unsuitable for data imputation. The total number of the populations is mentioned in the tables. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS-16 software.

RESULTS

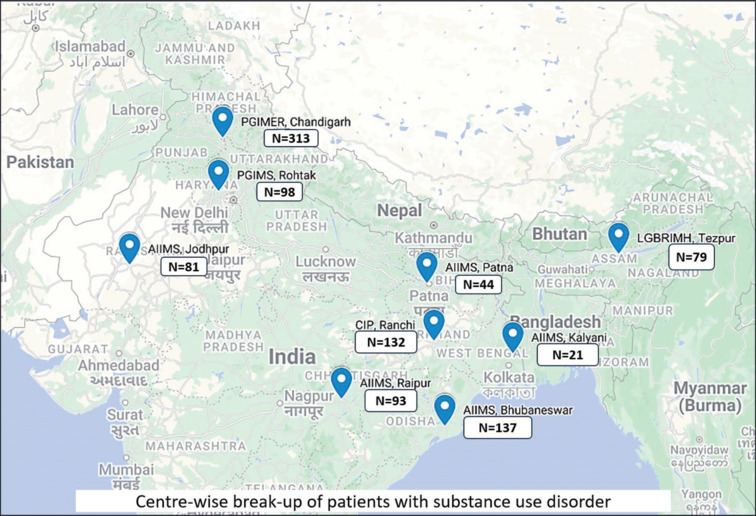

Three centers in north and western India enrolled 492 participants. Four centers of eastern India recruited 334 participants. The centers from central and northeastern India recruited 93 and 79 patients, respectively. Please see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Centrewise breakup of patients with SUD

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

The study population consisted of predominantly middle-aged (median: 32 years; IQR: 25–41 years) and men (98%) with intermediate-level education (median: 12 years; IQR: 8–15 years). The majority were married (60.5%), employed (81.9%), Hindu (75.4%), and nonindigenous (80.3%). Nearly half of the study population resided in rural areas (49.4%), and a similar proportion came from joint/extended families (50.2%).

The participants used substances for around 7 years (median: 84 months; IQR: 36–180 months) and were dependent for nearly 5 years (median: 60 months; IQR: 24–120). The first symptoms of SUD appeared around four and half years (median: 54 months; IQR: 24–180 months) before the index health contact. Around half of them were currently dependent on opioids (52.9%) and tobacco (52.8%); these were followed by alcohol (38.4%) and cannabis (17.1%) dependence. For details, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

| Variable | Median (Interquartile range)/n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Age in years (n=998) | 32 (Range: 25-41) | |

| Years of education (n=998) | 12 (Range: 8-15) | |

| Gender (n=998) | ||

| Male | 978 (98) | |

| Female | 13 (1.3) | |

| Others/Unknown | 7 (0.7) | |

| Indigenous population (n=998) | ||

| No | 801 (80.3) | |

| Yes | 151 (15.1) | |

| Not known | 46 (4.6) | |

| Marital status (n=998) | ||

| Married | 604 (60.5) | |

| Not married | 393 (39.4) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) | |

| Employment status (n=998) | ||

| Employed | 816 (81.9) | |

| Unemployed | 181 (18.1) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | |

| Locality (n=980) | ||

| Rural | 493 (49.4) | |

| Urban | 487 (48.8) | |

| Socioeconomic state (n=884) | ||

| Lower middle | 52 (5.9) | |

| Middle | 185 (20.9) | |

| Upper middle | 589 (66.6) | |

| Upper | 58 (6.6) | |

| Religion (n=998) | ||

| Hindu | 752 (75.4) | |

| Islam | 89 (8.9) | |

| Sikh | 128 (12.8) | |

| Others | 29 (2.9) | |

| Family type (n=998) | ||

| Nuclear | 487 (48.8) | |

| Joint/Extended | 501 (50.2) | |

| Others | 10 (1) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Duration of use (months) (n=984) | 84 (36-180) | |

| Duration of dependence (months) (n=968) | 60 (24-120) | |

| How long ago did the first symptoms appear (n=984) | 54 (24-120) | |

| Primary substance (n=998) | ||

| Opioids | 569 (57) | |

| Alcohol | 372 (37.3) | |

| Cannabis | 26 (2.6) | |

| Tobacco | 25 (2.5) | |

| Others | 6 (0.6) | |

| Profile of active dependence | ||

| Opioids dependence | 528 (52.9) | |

| Tobacco dependence | 526 (52.7) | |

| Alcohol dependence | 383 (38.4) | |

| Cannabis dependence | 171 (17.1) | |

| Number of substances to which patient was dependent in lifetime (n=982) | ||

| Single | 381 (38.8) | |

| Two | 466 (47.5) | |

| Three or more | 135 (13.7) | |

| Medical comorbidity and blood borne infections | ||

| Single med comorbidity | 134 (13.4) | |

| Multiple med comorbidity | 37 (3.7) | |

| HIV | 4 (0.4) | |

| HBV | 4 (0.4) | |

| HCV | 28 (2.8) | |

| Emergency reception visit (n=998) | ||

| Yes | 112 (11.2) | |

| No/Not known | 886 (88.8) | |

| Conflict with law (n=998) | ||

| Yes | 48 (4.8) | |

| No/Not known | 950 (95.2) | |

| First symptom | ||

| Compulsion | 573 (57.4) | |

| Tolerance | 202 (20.2) | |

| Withdrawal | 201 (20.1) | |

| Loss of control | 163 (16.3) | |

| Neglect | 16 (1.6) | |

| Use despite harm | 36 (3.6) |

Details of the PTC for SUDs

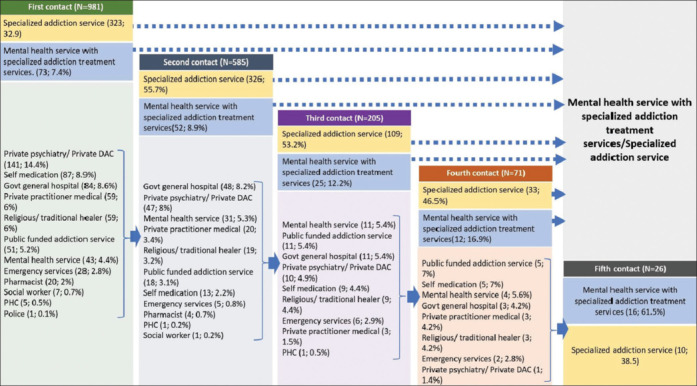

First contact: Among the 981 patients seeking first contact, a majority (32.9%) contacted specialized public-funded addiction treatment services (SAT), which was followed by a consultation with private psychiatrists/addiction-treatment centers (PP/PAT) (14.4%). Approximately 7.4%, 4.4%, and 5.2% of patients contacted mental health services with specialized addiction treatment facilities (MHSAT), mental health services (MHS), and public-funded addiction treatment services (PFAT), respectively. Other significant first contacts were self-medication (8.9%), public general hospitals (8.6%), private medical practitioners (6%), and traditional healers (6%). For details, see Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 2 (2.1MB, tif) .

Figure 2.

Pathway diagram for the patient population

The median interval between the first symptom and first contact was 151.6 weeks (IQR: 34.6–363.2 weeks). Relatives and friends (54.6%) and patients (29.2%) usually initiated the first contact. Withdrawal symptoms (56.4%) and use despite harm (15%) commonly led to the first contact. The majority of the patients received medications (78.9%), and 12.8% of the patients were referred to higher centers. For details, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Pathways to care related characteristics of the study sample

| Variable | Median (IQR)/n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| First contact (n=981) | ||

| Interval between first symptom and first contact (weeks) | 151.5 (34.6-363.2) | |

| Who initiated the first contact? | ||

| Relatives/friends | 536 (54.6) | |

| Patient self | 286 (29.2) | |

| Neighbors/relatives | 60 (6.1) | |

| Workmate/employers | 43 (4.4) | |

| Medical practitioners/mental health specialists | 39 (4) | |

| Others | 17 (1.7) | |

| What symptoms led to the first contact? | ||

| Withdrawal | 553 (56.4) | |

| Use despite harm | 147 (15) | |

| Loss of control | 72 (7.3) | |

| Aggression/self-harm/intoxication | 72 (7.3) | |

| Tolerance/Craving | 57 (5.8) | |

| Monetary problem/family issues/neglect | 40 (4.1) | |

| Others | 35 (3.5) | |

| Nature of treatment | ||

| Medication | 773 (78.9) | |

| No treatment/referral | 125 (12.8) | |

| Medical and Psychosocial | 38 (3.9) | |

| Psychosocial | 31 (3.2) | |

| Others | 14 (1.4) | |

| Second contact (n=585) | ||

| The first contact- second contact interval (Weeks) | 26 (3.2-77.9) | |

| Who initiated the second contact? | ||

| Relatives | 264 (45.1) | |

| Patient self | 181 (30.9) | |

| Medical practitioners/mental health specialists | 110 (18.7) | |

| Others | 30 (6) | |

| What symptoms led to the second contact? | ||

| Withdrawal | 331 (56.2) | |

| Use despite harm | 64 (11.3) | |

| Loss of control | 44 (7.5) | |

| Treatment failure/side effect/relapse | 34 (5.8) | |

| Aggression/self-harm/intoxication | 34 (5.8) | |

| Tolerance/Craving | 27 (4.6) | |

| Monetary problem/family issues/neglect | 15 (2.6) | |

| Others | 24 (5.9) | |

| Nature of treatment | ||

| Medication | 474 (79.4) | |

| Medical and psychosocial | 37 (6.2) | |

| No treatment/Referral | 28 (5.1) | |

| Psychosocial | 18 (3) | |

| Others/Unknown | 28 (5.1) | |

| Third contact (n=205) | ||

| The second contact- third contact interval (Weeks) | 26 (4.3-95) | |

| Who initiated the third contact? | ||

| Relatives | 85 (41.5) | |

| Patient self | 46 (22.4) | |

| Medical/Mental health practitioners | 34 (16.6) | |

| Self + relatives and friends | 33 (16.1) | |

| Workmates/employers | 4 (2) | |

| Others | 3 (1.5) | |

| What symptoms led to the third contact? | ||

| Withdrawal | 103 (50.2) | |

| Loss of control | 24 (11.7) | |

| Use despite harm | 17 (8.3) | |

| Aggression/self-harm/intoxication | 16 (8.3) | |

| Treatment failure/relapse | 16 (7.8) | |

| Craving/preoccupation/Money or family issues | 10 (4.9) | |

| Nonspecific/Others | 19 (9.3) | |

| Nature of treatment | ||

| Medication | 155 (76.4) | |

| Medical and psychosocial | 20 (9.9) | |

| No treatment/referral | 14 (6.9) | |

| Psychosocial | 5 (2.5) | |

| Others | 9 (4.4) | |

| Fourth contact (n=71) | ||

| The third contact- fourth contact interval (Weeks) | 26 (0.5-103) | |

| Who initiated the fourth contact? | ||

| Relatives | 21 (29.6) | |

| Patient self | 19 (26.8) | |

| Self + relative/friends | 16 (22.5) | |

| Mental health/medical professional | 12 (16.9) | |

| Others | 3 (4.2) | |

| What symptoms led to the fourth contact? | ||

| Withdrawal | 31 (44.3) | |

| Loss of control | 12 (17.1) | |

| Treatment failure | 9 (12.9) | |

| Use despite harm | 6 (8.6) | |

| Aggression | 6 (8.6) | |

| Others | 6 (8.6) | |

| Nature of treatment | ||

| Medication | 56 (80) | |

| Psychosocial with medication | 10 (14.3) | |

| Others | 5 (5.7) | |

| Fifth contact (n=26) | ||

| The fourth contact- fifth contact interval (weeks) | 8.6 (4-45) | |

| Who initiated the fifth contact? | ||

| Patient self | 8 (30.8) | |

| Relatives | 8 (30.8) | |

| Medical/mental health professional | 8 (30.8) | |

| Others | 2 (7.7) | |

| What symptoms led to the fifth contact? | ||

| Withdrawal | 8 (30.8) | |

| Treatment failure | 5 (19.2) | |

| Loss of control | 5 (19.2) | |

| Craving/use despite harm/aggression | 3 (11.4) | |

| Others | 5 (19.2) | |

| Nature of treatment at | ||

| Medication | 17 (65.4) | |

| Medical and psychosocial | 9 (34.6) |

Nature of second to fifth contacts

The number of patients reduced from 585 at the second contact to 26 at the fifth contact. A total of 326 (55.7%), 109 (53.2%), 33 (46.5%), and 10 (38.5%) patients took SAT consultation across the second to fifth consultations. The proportion of MHSAT consultations increased gradually from 52 (8.9%) at the second contact to 25 (12.2%), 12 (16.9%), and 16 (61.5%) in subsequent contacts. The MHS consultation proportion remained relatively constant, and patients seeking PFAT increased from 3.1% to 7% across second to fourth contacts. The proportion of PP/PAT consultation gradually reduced from 8% to 4.9% and 1.4% across second to fourth contacts. The percentage of patients seeking private medical consultation was 3.4%, 1.5%, and 4.2% in the second to fourth consultations. The percentage of patients taking self-medication gradually increased from 2.2% to 7% between the second and fourth contacts. In contrast, the proportion of patients seeking religious or traditional healing was relatively stable across the contacts (3.4% to 4.4%). For details, see Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 2 (2.1MB, tif) .

Treatment details of second to fifth contacts

The median time lag between a contact and its previous contact was around 26 weeks across second to fourth contacts, which reduced to 8.6 weeks in the fifth contact. The patient’s relatives initiated the contact in 45.1% of cases during the second contact, which reduced to around 30% of cases in fourth and fifth contacts, whereas 30.9%, 22.4%, 29.6%, and 30.8% of patients initiated the contact across second to fifth contacts. The proportion of referrals from medical or psychiatric professionals increased from around one-sixth of cases during the second to fourth contact to around one-third of cases in the fifth contact. Substance withdrawal remained the predominant complaint, followed by loss of control and use despite harm, which led to the consultation. The proportion of patients seeking treatment for previous treatment failure increased from 5.8% to 7.8%, 12.9%, and 19.2% across second to fifth contacts. The vast majority of patients, ranging between 79.8% (third contact) and 65.4% (fifth contact) received only pharmacotherapy. Mere 6.2%, 9.9%, 14.3%, and 34.6% of patients received psychosocial management along with medications across second to fifth contacts.

For details, see Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with the PAC versus OMC groups

The PAC group was younger (PAC 33.4 ± 11.9 years, OMC 39.8 ± 11.5 years, U = 82213, df 820, P < .001) and more educated (PAC-11.1 ± 4.4 years, OMC-10 ± 4.4 years, U = 50843, df 818, P < .001). Indigenous (χ2 = 4.6; P = 0.03), single (χ2 = 20.1; P < .001), and urban (χ2 = 8.3; P = .004) participants were more likely to seek PAC. The OMC group had a longer duration of substance use (U = 78635, df = 812, P < .001) and dependence (U = 76644, df = 790, P < .001). The OMC group had a significantly higher prevalence of AUD (71.4%), whereas the PAC group had a higher OUD prevalence (65.3%) (χ2 = 121; P < .001). The patients with medical comorbidities (χ2 = 50.3; P < .001), substance withdrawal (χ2 = 31.6; P < .001), loss of control (χ2 = 12.6; P = .001), and use of substances despite harmful consequences (χ2 = 28.2; P < .001) were more likely to obtain OMC, whereas those initially presenting with compulsion to use substances (χ2 = 14; P < .001) had higher likelihood for PAC. For further details, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between psychiatric/addiction service consultation and other medical consultation in first contact

| Parameter | Psychiatric/Addiction related consultation (PAC) (Mean±SD) (n=631) | Other medical consultation (OMC) (Mean±SD) (n=196) | U/χ2/F | df | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||||||||

| Age in years (n=822) | 33.4±11.9 | 39.8±11.5 | 82213 | 820 | <.001 | |||||

| Education in years (n=820) | 11.1±4.4 | 10±4.4 | 50842.5 | 818 | 0.001 | |||||

| Gender (n=827) | ||||||||||

| Male | 622 (98.6) | 190 (97) | 6.4 | 2 | 0.051 | |||||

| Female | 7 (1.1) | 4 (2) | ||||||||

| Others | 2 (0.3) | 2 (1) | ||||||||

| Indigenous population (n=827) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 96 (15.2) | 18 (9.2) | 4.6 | 1 | 0.03 | |||||

| No/Not known | 535 (84.8) | 178 (90.8) | ||||||||

| Marital status (n=827) | ||||||||||

| Married | 364 (57.7) | 148 (75.5) | 20.1 | 1 | <.001 | |||||

| Not married | 267 (41.7) | 48 (24.5) | ||||||||

| Occupation (n=827) | ||||||||||

| UE/unskilled/household/semiskilled | 257 (40.7) | 81 (41.3) | 0.02 | 1 | 0.88 | |||||

| Others | 374 (59.3) | 115 (58.7) | ||||||||

| Socioeconomic status (n=730) | ||||||||||

| Lower-middle | 30 (5.5) | 14 (7.8) | 2.05 | 3 | 0.56 | |||||

| Middle | 114 (20.7) | 32 (17.8) | ||||||||

| Upper-middle | 367 (66.7) | 123 (68.3) | ||||||||

| Upper | 39 (7.1) | 11 (6.1) | ||||||||

| Locality (n=811) | ||||||||||

| Rural | 295 (47.5) | 113 (59.5) | 8.3 | 1 | 0.004 | |||||

| Urban | 326 (52.5) | 77 (40.5) | ||||||||

| Clinical variables | ||||||||||

| Duration of use in months (n=814) | 118.1±117.6 | 170.6±118.5 | 78635 | 812 | <.001 | |||||

| Duration of dependence in months (n=792) | 81.1±93.1 | 112.1±84.5 | 76644 | 790 | <.001 | |||||

| Primary substance (n=827) | ||||||||||

| Alcohol | 176 (27.9) | 140 (71.4)† | 121 | 2 | <.001 | |||||

| Opioid | 412 (65.3)* | 47 (24) | ||||||||

| Others | 43 (6.8) | 9 (4.6) | ||||||||

| Secondary substance (n=504) | ||||||||||

| Tobacco | 255 (66.4) | 101 (84.2)‡ | 15.3 | 3 | 0.002 | |||||

| Cannabis | 79 (20.6)§ | 9 (7.5) | ||||||||

| Alcohol | 37 (9.6) | 6 (5) | ||||||||

| Others | 13 (3.4) | 4 (3.3) | ||||||||

| Medical comorbidity (n=827) | ||||||||||

| Absent | 552 (87.5) | 128 (65.3) | 50.3 | 1 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Present | 79 (12.5) | 92 (34.7) | ||||||||

| HCV seropositivity (n=827) | ||||||||||

| Absent | 613 (97.1) | 193 (98.5) | 1.1 | 1 | 0.44 | |||||

| Present | 18 (2.9) | 3 (1.5) | ||||||||

| First symptom profile | ||||||||||

| Compulsion (n=808) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 381 (61.7) | 88 (46.3) | 14 | 1 | <.001 | |||||

| No | 237 (38.3) | 102 (53.7) | ||||||||

| Tolerance (n=808) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 125 (20.2) | 48 (25.3) | 2.2 | 1 | 0.14 | |||||

| No | 493 (79.8) | 142 (74.7) | ||||||||

| Withdrawal (n=808) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 101 (16.3) | 67 (35.3) | 31.6 | 1 | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 517 (83.7) | 123 (64.7) | ||||||||

| Loss of control (n=808) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 83 (13.4) | 46 (24.2) | 12.6 | 1 | 0.001 | |||||

| No | 535 (86.6) | 144 (75.8) | ||||||||

| Neglect (n=808) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 9 (1.5) | 6 (3.2) | 2.3 | 1 | 0.13 | |||||

| No | 609 (98.5) | 184 (96.8) | ||||||||

| Use despite harm (n=808) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 12 (1.9) | 20 (10.5) | 28.2 | 1 | <.001 | |||||

| No | 606 (98.1) | 170 (89.5) | ||||||||

| How long ago did the first contact occur (weeks) (n=800) | 55.9±102.2 | 166.3±220.7 | 86087 | 798 | <.001 | |||||

| First Symptom first contact interval (weeks) (n=798) | 283.8±397.7 | 308.7±368.3 | 59801 | 796 | 0.56 |

*Standardised adjusted residual=10. †Standardised adjusted residual=11. ‡Standardised adjusted residual=3.7. §Standardised adjusted residual=3.3

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first multisite study from an LMIC to examine the PTC for people with SUD. We strategically chose our study sites to represent the diversity of the country’s demographic, socioeconomic, and health indicators and substance use patterns. This added to the generalizability of our study results.

Specialized addiction treatment (SAT) and mental health services with specialized addiction treatment services (MHSAT) dominated all the contacts. Only five cases in the first contact used primary care, whereas a mere 4–8% of patients across the contacts used public secondary-level healthcare (e.g., district hospitals). Given half of our study population was from rural areas, the scant contact with primary and secondary care was striking. A substantial minority sought help from traditional healers and used over-the-counter (OTC) self-medications. The first healthcare contact occurred around 3 years after the appearance of the first symptom. The gaps between contacts were more than 6 months.

These findings suggest an overt reliance on specialized healthcare services and private medical care in Indian patients. In the background of an estimated 77% deficit of psychiatrists and below 50% coverage of the district mental health program, excessive emphasis on specialized addiction services is worrisome.[12] The treatment gap of 75%–85% cannot be bridged until SUD care is integrated into primary and general healthcare. The Ayushman Bharat scheme aims to integrate noncommunicable disease (NCD) screening and treatment into primary care.[31] If brought under the broad NCD screening and treatment framework, integrating SUD treatment into primary care seems plausible.

In our sample, private healthcare contact for SUD treatment is much less (4% to 8% across contacts) than for general healthcare. Almost half of our sample resided in a rural area, where urban private mental healthcare is difficult to access. Private healthcare in India is six times costlier than public healthcare.[32] Scant health insurance coverage (~15% of the population), exclusion of SUD from many insurance schemes,[33] and economic constraints limit the affordability of private addiction care. Low interest in private addiction care emphasizes an urgent need for universal health insurance and the inclusion of SUD treatment.

Easy accessibility and availability may increase the importance of traditional healers for patients with mental illness,[25,33,34] which was not seen in our sample. The studies on the care pathways of SUD patients consistently show that, in contrast to those with mental illness, fewer SUD cases seek treatment from traditional healers.[20,25] This highlights the possibility of different care pathways in psychiatric disorders and SUD. More than half of the first contacts were initiated by the patient’s relatives, reflecting the importance of family in the Indian context. Besides, the self-initiated treatment-seeking increased steadily across subsequent visits. This showed initial treatment engagement might improve the patient’s motivation for treatment. A related finding was minimal referral from the healthcare services. This may be due to limited knowledge and opportunity to link care to higher services.[15]

Younger and more educated people (“proxy” of awareness) were more likely to consult with addiction/mental health services. A similar result was found in another study in North India, where younger, more educated population with less duration of heroin use tended to visit the tertiary level deaddiction care. In contrast, the older, less educated patients with longer use of natural opioids preferred visiting the community outreach clinic of the same tertiary care hospital.[28] The association of the indigenous population and first PAC contact could have resulted from the proximity and better access of some of our study sites to the tribal population. Substance withdrawals and medical comorbidities direct the first contact to medical services. This indicates that physical complaints drive patients to nonmental healthcare contacts. The overrepresentation of OUD in PAC indicates opioid agonist treatment availability in these centers.

Although there were diverse sites, some (e.g. Chandigarh) overrepresented the sample. Moreover, the regional representation was skewed toward northern and eastern regions, with no sites from southern India. All our study sites were specialized mental health and addiction services. Participants contacting this level of healthcare might differ from those who would never reach tertiary care. This must be considered while generalizing our results to PTC in persons with SUD. Although we have quantitative estimates of PTC for SUD, our study does not inform the reasons for choice, preferences, quality, and satisfaction with healthcare contacts, and we could not avoid the recall bias for our study as some participants forgot some of their earlier contact details. Finally, our sample had male dominance, which might reflect the less treatment-seeking or a lesser SUD prevalence among Indian women.[13] Nevertheless, our results might not apply to women with SUD.

Our study showed the need to strengthen the public healthcare infrastructure and health delivery system and integrate SUD treatment into the public healthcare sectors to ensure accessible, affordable, and effective SUD treatment. Our results have also demonstrated the need to strengthen the referrals within healthcare systems for a seamless SUD care continuum.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Study flow diagram

Details of the care pathways across the contacts

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the staff across the centers, who helped in the data collection, and logistics.

REFERENCES

- 1.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Erratum. Lancet. 2020;396:1562. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogler LH, Cortes DE. Help-seeking pathways: A unifying concept in mental health care. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:554–61. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huxley P. Mental illness in the community: The Goldberg-Huxley model of the pathway to psychiatric care. Nord J Psychiatry. 1996;50(suppl 37):47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gater R, de Almeida e Sousa B, Barrientos G, Caraveo J, Chandrashekar CR, Dhadphale M, et al. The pathways to psychiatric care: A cross-cultural study. Psychol Med. 1991;21:761–74. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002239x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lilford P, Wickramaseckara Rajapakshe OB, Singh SP. A systematic review of care pathways for psychosis in low-and middle-income countries. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102237. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.SAMHSA Pathways to Healing and Recovery: Perspectives from Individuals with Histories of Alcohol and other Drug Problems. http://www.samhsa.gov. 2010 . Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/recovery_pathways_report.pdf . [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 06] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Commander MJ, Odell SO, Williams KJ, Sashidharan SP, Surtees PG. Pathways to care for alcohol use disorders. J Public Health Med. 1999;21:65–9. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/21.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health England . London, UK: PHE Publications; 2017. Better Care for people with co-occurring mental health and alcohol/drug use conditions. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a75b781ed915d6faf2b5276/Co-occurring_mental_health_and_alcohol_drug_use_conditions.pdf . [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 06] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson GK, Manion IG, Carter C. Pathways to care for youth with concurrent mental health and substance use disorders: Care for youth with concurrent mental health and Substance Use Disorders. Canadian Electronic Library; 2023 Available from: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1224873/pathways-to-care-for-youth-with-concurrent-mental-health-and-substance-use-disorders/1777951/ . [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 06] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gater R, Jordanova V, Maric N, Alikaj V, Bajs M, Cavic T, et al. Pathways to psychiatric care in Eastern Europe. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:529–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rathod S, Pinninti N, Irfan M, Gorczynski P, Rathod P, Gega L, et al. Mental health service provision in low- and middle-income countries. Health Serv Insights. 2017;10:1178632917694350. doi: 10.1177/1178632917694350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh LK, et al. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015–16: Prevalence, patterns and outcomes. Bengaluru National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, NIMHANS Publication No. 129. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambekar A, Agrawal A, Rao R, Mishra A, Khandelwal S, Chadda R, et al. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India; 2019. Magnitude of substance use in India. Available from: https://socialjustice.gov.in/writereaddata/UploadFile/Survey%20Report636935330086452652.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao N. Who is paying for India’s healthcare? 2018. Available from: https://thewire.in/health/who-is-paying-for-indias-healthcare . [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 06] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selvaraj S, Karan AK, Srivastava S, Bhan N, Mukhopadhyay I. India Health System Review. In: Mahal A, editor. New Delhi, India: World Health Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhawan A, Rao R, Ambekar A, Pusp A, Ray R. Treatment of substance use disorders through the government health facilities: Developments in the “Drug De-addiction Programme” of Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:380–4. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_19_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith MK, Solomon SS, Cummings DAT, Srikrishnan AK, Kumar MS, Vasudevan CK, et al. Overlap between harm reduction and HIV service utilisation among PWID in India: Implications for HIV combination prevention. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;57:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MoSJE) Addiction Treatment Facility: About the Scheme. 2020 Available from: https://atf-scheme.in/about-us.aspx . [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 06] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhawan A, Chopra A, Ray R. Preferences for treatment setting by substance users in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38:42–5. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.175105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balhara YPS, Prakash S, Gupta R. Pathways to care of alcohol -dependent patients: An exploratory study from a tertiary care substance use disorder treatment center. Int J High Risk Behav Addict. 2016;5:e30342. doi: 10.5812/ijhrba.30342. doi: 10.5812/ijhrba.30342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bansal SP, Sidana A, Mehta S. Pathways to care and reasons for treatment-seeking behavior in patients with opioid dependence syndrome: An exploratory study. J Ment Health Hum Behav. 2019;24:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parmar A, Gupta P, Bhad R. An exploratory study of clinical profile, stigma and pathways to care among primary cannabis use disorder patients in India. J Subst Use. 2022;27:74–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tripathi R, Singh S, Sarkar S, Lal R, Balhara YP. Pathway to care in co-occurring disorder and substance use disorder: An exploratory, cross-sectional study from India. Adv Dual Diagn. 2021;14:20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Somashekar VM, John S, Praharaj SK. Pathways to care in alcohol use disorders: A cross-sectional study from a tertiary hospital in South India. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2023:1–14. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2023.2189197. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2023.2189197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balan A, Kannekanti P, Khanra S. Pathways to care for substance use treatment among tribal patients at a psychiatric hospital: A comparative study. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2023;14:432–9. doi: 10.25259/JNRP_30_2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parmar A, Gupta P, Panda U, Bhad R. An observational study assessing the pathways to care among treatment seeking users of natural opiates. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2020;27:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhad R, Gupta R, Balhara YPS. A study of pathways to care among opioid dependent individuals seeking treatment at a community de-addiction clinic in India. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2020;19:490–502. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2018.1542528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bansal SP, Sidana A, Mehta S. Pathways traversed by patients with opioid dependence syndrome in two settings: An exploratory study. Ann Psychiatry. 2023;1:11–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Global Data Lab Subnational HDI (v7.0) 2021 Available from: https://globaldatalab.org/shdi/table/shdi/IND/ . [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 06] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wani RT. Socioeconomic status scales-modified Kuppuswamy and Udai Pareekh’s scale updated for 2019. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:1846–9. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_288_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare . New Delhi: NHSRC; 2018. AYUSHMAN BHARAT comprehensive primary health care through health and wellness centers operational guidelines. Available from: https://www.nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/Health_System_Stregthening/Comprehensive_primary_health_care/letter/Operational_Guidelines_For_CPHC.pdf . [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 06] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garg S, Tripathi N, Ranjan A, Bebarta KK. Comparing the average cost of outpatient care of public and for-profit private providers in India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:838. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06777-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MOSPI India - Social Consumption: Health, NSS 71st round: Jan - June 2014. Producer(s) National Sample Survey Office - M/o Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI), Government of India (GOI) 2019 Available from: https://microdata.gov.in/nada43/index.php/catalog/135 . [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 06] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thara R, Islam A, Padmavati R. Beliefs about mental illness: A study of a rural South-Indian community. Int J Ment Health. 1998;27:70–85. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study flow diagram

Details of the care pathways across the contacts