Abstract

Childhood externalizing psychopathology is heterogeneous. Symptom variability in conduct disorder (CD), oppositional-defiant disorder (ODD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and callous-unemotional (CU) traits designate different subgroups of children with externalizing problems who have specific treatment needs. However, CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits are highly comorbid. Studies need to generate insights into shared versus unique risk mechanisms, including through use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). In this study, we tested whether symptoms of CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits were best represented within a bifactor framework, simultaneously modeling shared (i.e., general externalizing problems) and unique (i.e., symptom-specific) variance, or through a four-correlated factor or second-order factor model. Participants (N=11,878; age, M = 9 years old) were from the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study. We used questionnaire and fMRI data (emotional N-Back task) from the baseline assessment. A bifactor model specifying a general externalizing and specific CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits factors demonstrated the best fit. The four-correlated and second-order factor models both fit the data well and were retained for analyses. Across models, reduced right amygdala activity to fearful faces was associated with more general externalizing problems and reduced dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activity to fearful faces was associated with higher CU traits. ADHD scores were related to greater right nucleus accumbens activation to fearful and happy faces. Results give insights into risk mechanisms underlying comorbidity and heterogeneity within externalizing psychopathology.

Keywords: attention-deficit/hyperactivity, callous-unemotional traits, emotion processing, functional magnetic resonance imaging, oppositional-defiance

General Scientific Summary

Decreased amygdala reactivity to fearful emotion faces may represent a general neural risk marker for externalizing psychopathology. Decreased dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reactivity to fearful faces may be a specific neural marker for callous-unemotional traits, while increased right nucleus accumbens activation to happy faces may relate specifically to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms, over and above externalizing psychopathology severity.

Symptoms of childhood conduct disorder (CD; i.e., aggression, serious rule violation), oppositional-defiance disorder (ODD; i.e., non-compliance), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; i.e., excessive inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity), and callous-unemotional (CU) traits (i.e., low empathy and guilt; Frick et al., 2014; Waller & Hyde, 2018) are common and comorbid features of externalizing psychopathology (Kahn et al., 2013; Waschbusch et al., 2020). Prior research often studied CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits separately in relation to risk for psychiatric disorders across the lifespan (Frick & Marsee, 2018; Orri et al., 2019; Wymbs et al., 2012). However, recent work emphasizes comorbidity among these constructs within dimensional frameworks (Krueger et al., 2021). Importantly, comorbidity is associated with poorer prognosis and treatment outcomes (Hawes et al., 2017; McMahon et al., 2010), especially for children with CU traits (Balia et al., 2018; Perlstein et al., 2023). Better knowledge of the shared and unique risk mechanisms underlying CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits can inform more effective universal and targeted treatment strategies.

CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits are associated with emotion processing difficulties, including perceiving, expressing, and regulating emotions (Da Fonseca et al., 2009; Hartmann & Schwenck, 2020; Morawetz et al., 2020). While CD, ODD, and ADHD symptoms are linked to broad difficulties in emotion recognition (Da Fonseca et al., 2009; Rehder et al., 2017; Schwenck et al., 2014; Staff et al., 2022), CU traits have been associated with more prominent difficulties recognizing expressions of distress (Marsh & Blair, 2008; Moore et al., 2019), including evidence that fearlessness is an important mechanism whereby CU traits escalate to more severe CD in late childhood (Fanti et al., 2023). Together, these emotion processing difficulties are thought to underlie harmful behavioral features associated with CD (e.g., hostile attribution bias), ODD (e.g., excessive reactivity to negative emotion cues), ADHD (e.g., general emotion dysregulation), and CU traits (e.g., lack of empathy, fearlessness). Thus, studies focused on the emotion processing difficulties associated with CD, ODD, ADHD, or CU traits can generate insights into treatment targets for children with externalizing psychopathology.

Studies have used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to understand the emotion processing difficulties associated with externalizing psychopathology (Ansari Nasab et al., 2022; Brotman et al., 2010; Umbach & Tottenham, 2021). Use of fMRI provides a biological lens to understand what is observable at the behavioral level, while characterizing risk mechanisms for different symptom profiles within the externalizing spectrum (Takamura & Hanakawa, 2017). For example, while 127 children aged 8–17 appeared indistinguishable based on behavioral task performance, fMRI data collected during an emotion processing task identified clinically distinct groups with ADHD versus bipolar disorder (Brotman et al., 2010). Likewise, among 80 children aged 2–3, neural activation to language differentiated children later diagnosed with autism compared to those with typical development (Eyler et al., 2012). Thus, fMRI has the potential to provide insights into distinct mechanisms underlying general externalizing problems, as well as the specific features of CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits.

Emotion processing is underpinned by brain regions within the limbic system and prefrontal cortex (Pozzi et al., 2021). In particular, the fusiform gyrus, superior temporal gyrus (STG), amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), and insula are implicated in processing emotional faces (Adolphs, 2002). A subcortical network that includes the amygdala, fusiform gyrus, parahippocampus, periaqueductal gray (PAG), and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) has also been linked to emotion perception, generation, and reactivity (Morawetz et al., 2020). Finally, meta-analytic studies identified four regions – the amygdala, fusiform gyri, posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC) – as core neural structures implicated in implicit emotion processing (i.e., automatic processing and recognition [Gyurak et al., 2011; Pozzi et al., 2021]).

Prior fMRI studies of CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits report findings that are inconsistent in directionality when it comes to these emotion processing regions, especially in the context of social stimuli. CD and ODD have been linked to increased amygdala reactivity to fearful and angry faces, but not happy, sad, or neutral faces (Aggensteiner et al., 2022; Noordermeer et al., 2016) though in one case for CD, only after covarying for CU traits (Lozier et al., 2014). CU traits have been linked to reduced amygdala reactivity to fearful faces (Cardinale et al., 2019; Marsh et al., 2008; Viding et al., 2012), although this finding has not been consistently replicated (Berluti et al., 2023; Deming et al., 2022; Dotterer et al., 2020). Finally, ADHD symptoms were linked to heightened amygdala reactivity to emotional faces in one study (Brotman et al., 2010), but reduced amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli in another (Viering et al., 2022). Together, these mixed findings highlight complexity in the neural underpinnings of emotion processing difficulties among children with externalizing problems, which may be compounded when studies examine CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits as independent dimensions, rather than modeling their comorbidity (Brotman et al., 2010; Hartmann & Schwenck, 2020). Moreover, prior research has often used categorical analyses (e.g., case-control comparisons, Brotman et al., 2010; Hartmann & Schwenck, 2020), which contrasts with evidence that psychiatric phenomena exist on continua (Brandes et al., 2019; Caspi & Moffitt, 2018). To date, no studies have examined neural correlates of CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits by modeling both their heterogeneity and comorbidity within a dimensional framework. Lastly, prior fMRI studies have relied on small sample sizes, which limits reliability and validity of findings. Thus, future work is needed to examine associations in larger samples.

Factor analysis allows different hypotheses about brain-behavior relationships to be tested by comparing findings for superordinate/general and subordinate/specific symptom dimensions (i.e., factors) of externalizing psychopathology (Markon, 2019; McGrew, 2009). Common factor models include unidimensional (i.e., single construct), correlated-factor (multiple factors), second-order (i.e., a hierarchical model with subordinate factors), and bifactor models (simultaneous general and specific factors) (Dunn & McCray, 2020). Each model parses shared (i.e., comorbidity) and unique (i.e., heterogeneity) variance somewhat differently, with different implications for understanding brain-behavior associations. In a correlated-factor model, symptom-specific factors have unique variance and comorbidity is represented through their correlation (Markon, 2019). In second-order models, a hierarchical factor is directly defined by specific, subordinate factors (Markon, 2019). Finally, bifactor models simultaneously estimate variance explained by orthogonally-specified general and specific factors (i.e., shared variance is subsumed within the general factor) (Brown, 2015). Bifactor models are theoretically appealing for modeling shared versus unique variance (Zhang et al., 2021). However, bifactors models also estimate many parameters, increasing risk of model non-identification (Zhang et al., 2021) and overfit (Markon, 2019). To address these limitations, well-powered studies are needed that directly compare brain-behavior findings across different structural models within the childhood externalizing spectrum.

In the current paper, we tested the fit of competing structural models of externalizing psychopathology for CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits: a one-factor model, four-correlated factor model, second-order model, and bifactor model. We compared brain-behavior associations for the best-fitting models to isolate shared versus unique neural mechanisms. We focused on neural reactivity to fearful versus neutral faces and happy versus neutral faces within 10 regions of interest (ROIs) identified in prior meta-analytic studies of emotion processing (Morawetz et al., 2020; Pozzi et al., 2021): frontal pole, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), OFC, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), STG, fusiform gyrus, amygdala, parahippocampal gyrus, nucleus accumbens (NAc), and insula. We hypothesized that lower amygdala reactivity to fearful and happy faces would relate to general externalizing and specific CD and CU traits scores. We also hypothesized that ODD and ADHD would relate to increased amygdala activation to fearful versus neutral faces, but not happy versus neutral faces. As a test of sensitivity, we re-ran models to compare results for children meeting versus not meeting current/past diagnostic thresholds for a disruptive behavior disorder (DBD) diagnosis.

Methods

Participants

We used data from the 4.0 release of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development℠ Study (ABCD Study®) (https://abcdstudy.org/), which includes 11,878 children aged 9–10 (48% female; 57% Caucasian, 15% African American, 20% Hispanic, 8% other). Participants were recruited from 21 study sites across the United States and sampling approaches were used to recruit a sample that closely approximated national sociodemographics (Garavan et al., 2018). We used questionnaire data and tabulated fMRI data from the baseline assessment.

Measures

Conduct Disorder Symptoms.

CD was assessed using a 16-item scale (e.g., “threatens people”) from the parent-reported Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Items were rated on a 3-point scale (0=not true; 2=very/often true) (α=.80). To avoid content overlap with CU traits, a single item (“lack of guilt”) was omitted.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder Symptoms.

ODD was assessed using a 5-item scale (e.g., “argues”) from the parent-reported CBCL. Items were rated on a 3-point scale (0=not true; 2=very/often true) (α=.80).

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms.

ADHD were assessed using a 7-item scale (e.g., “can’t sit still”) from the parent-reported CBCL. Items were rated on a 3-point scale (0=not true; 2=very/often true) (α=.85).

CU Traits.

We assessed CU traits using a validated measure (Hawes et al., 2020), which includes 1 item from the CBCL (“lack of guilt”) and 3 items (reverse-scored) from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997) (e.g., “helpful if someone is upset”). Items were rated on a 3-point scale (0=not true; 2=certainly true) (α=.75).

Disruptive Behavior Disorder Diagnosis.

Parents completed the self-administered computerized version of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (KSADS-COMP; Townsend et al., 2020) at baseline. Symptom reports were categorized as meeting versus not meeting DSM-5 thresholds (Duffy et al., 2023), which we applied to evaluate past/current diagnostic status for CD (child- or adolescent-onset) and ODD. Children were categorized as having met (1) or not met (0) DBD diagnostic thresholds.

Imaging Measures

We used processed data and tabulated ROI data available from the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) Data Archive (NDA) (Hagler et al., 2018) (Supplemental Methods).

Emotional N-Back Task (EN-Back).

The EN-back was adapted from the Human Connectome Project n-back task (Barch et al., 2013). Children completed 2 runs, each consisting of 8 blocks. In each run, 4 blocks were 2-back conditions, and 4 blocks were 0-back condition. For 2-back conditions, children responded “match” when the stimulus was the same as that shown two trials back. For the 0-back condition, children responded “match” when the stimulus was the same as that presented at the start of the trial. Each block had 10 trials (total, 160 trials, which began with a 500 ms colored fixation to alert children of a switch in task condition, followed by a 2.5 s cue that indicated the condition (e.g., “2-back,” “target=,” and a photo of the target stimulus). The stimulus (i.e., emotion face, neutral face, or place) was presented for 2 s, followed by a 500 ms fixation cross. Average accuracy was 82%. We focused on the fearful versus neutral and happy versus neutral contrasts to index implicit emotion processing (Dreyfuss et al., 2014; O’Brien et al., 2020).

Processed imaging data were mapped to 33 cortical ROIs for each hemisphere based on the Desikan-Killiany atlas (Desikan et al., 2006). Subcortical structure segmentations were based on FreeSurfer (automatic segmentation) subcortical parcellations (Fischl et al., 2002). Ten ROIs were selected based on previous studies (Morawetz et al., 2020; Pozzi et al., 2021), including studies that used the EN-Back within the ABCD sample (Geckeler et al., 2022): the frontal pole, dlPFC, OFC, ACC, STG, fusiform gyrus, amygdala, parahippocampal gyrus, NAc, and insula (Figure S1). Participants were excluded if their imaging data did not pass quality assurance criteria or they had poor accuracy (≤.60; O’Brien et al., 2020).

Covariates

Models controlled for covariates derived from parent report: child age in months, child sex (1=female, 0=male), family income, and child race/ethnicity (i.e., minoritized=1; White, Non-Hispanic/Latino/a=0). Neuroimaging models controlled for EN-back task accuracy.

Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted in Mplus vs. 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) with clustering for site and family to account for dependence between observations (e.g., siblings) using mean and variance-adjusted weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimation. Model fit was evaluated using standard cut-offs for comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). First, we used Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to estimate one-factor, four-correlated factor, second-order factor, and bifactor models and conducted corrected chi-square differences tests using the DIFFTEST option to compare the fit of competing models. To establish construct validity of the best fitting models, we regressed factors onto DBD diagnosis, accounting for covariates. Second, we tested brain-behavior associations using fMRI data from the EN-Back task and compared findings for different models. We specified four correlated dependent variable models, regressing all ROIs for each contrast onto the structural models as relevant (i.e., allowing estimates of regional activation to correlate), accounting for demographic covariates and accuracy. Brain-behavior associations were tested for each of the best-fitting structural models. We applied a False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction for the four models tested for each structural model (i.e., fearful face contrast, right and left hemisphere; happy face contrast, right and left hemisphere)(Kircanski et al., 2018). Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses, evaluating the fit of structural models and brain-behavior associations for youth meeting versus not meeting criteria for current/past DBD diagnosis.

Transparency and Openness

The analytic plan was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF), see https://osf.io/enp2d/?view_only=254f22f33de04378baa299cad75b48ab. Sample size determinations, data exclusions, and all included measures are reported above. Data and research materials are available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FHZK7. There were deviations from the pre-registration that occurred prior to and following peer-review, including the addition of CD and ADHD symptoms, comparison of findings for different structural models, and use of cross-sectional data only (Supplemental Materials).

Results

Tables S1–2 present descriptive statistics for all variables. Tables S3–4 present bivariate correlations between variables. Figure S2 presents frequency plots for externalizing symptom scores for the full sample, subsample with a current/past DBD diagnosis, and non-DBD sample.

Estimating Structural Models of Externalizing Psychopathology

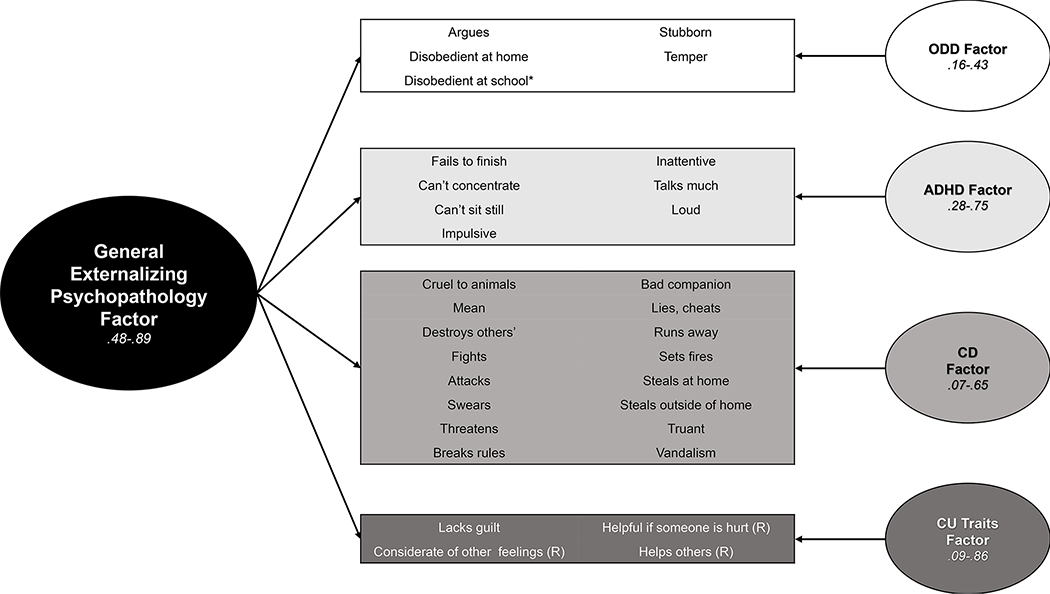

A four-correlated factor (χ2(458)= 12,167.53; CFI=.94; TLI=.93; RMSEA=.05), second-order factor (χ2(460)= 12,031.14; CFI=.94; TLI=.94; RMSEA=.05), and bifactor model (χ2(433)= 4,448.83; CFI=.98; TLI=.98; RMSEA=.03; Figure 1) each had excellent model fit, significantly outperforming a one-factor model, which showed poor fit (χ2(464)= 32,798.38; CFI=.84; TLI=.83; RMSEA=.08; Supplemental Results and Tables S5–S7). There were largely expected associations between the different estimated externalizing factors and current/past DBD diagnosis (Supplemental Results and Table S8). Next, we compared brain-behavior associations for the four-correlated factor, second-order factor, and bifactor models for the fearful versus neutral and happy versus neutral contrasts across the 10 ROIs.

Figure 1.

Bifactor model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity, oppositional defiance, conduct problems, and CU traits

Note Model fit: χ2(433)= 4,448.83; CFI=.98; TLI=.98; RMSEA=.03. See Table S5 for individual item-factor loadings. *For the bifactor model one item loaded negatively on the specific ODD factor and was removed (“Disobedient at school”). ADHD=Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Specific Factor; CD=Conduct Disorder Specific Factor; CU=Callous-unemotional traits Specific Factor; ODD= Oppositional-Defiance Disorder Specific Factor.

Brain-Behavior Associations for Different Structural Models

Fearful versus neutral faces contrast.

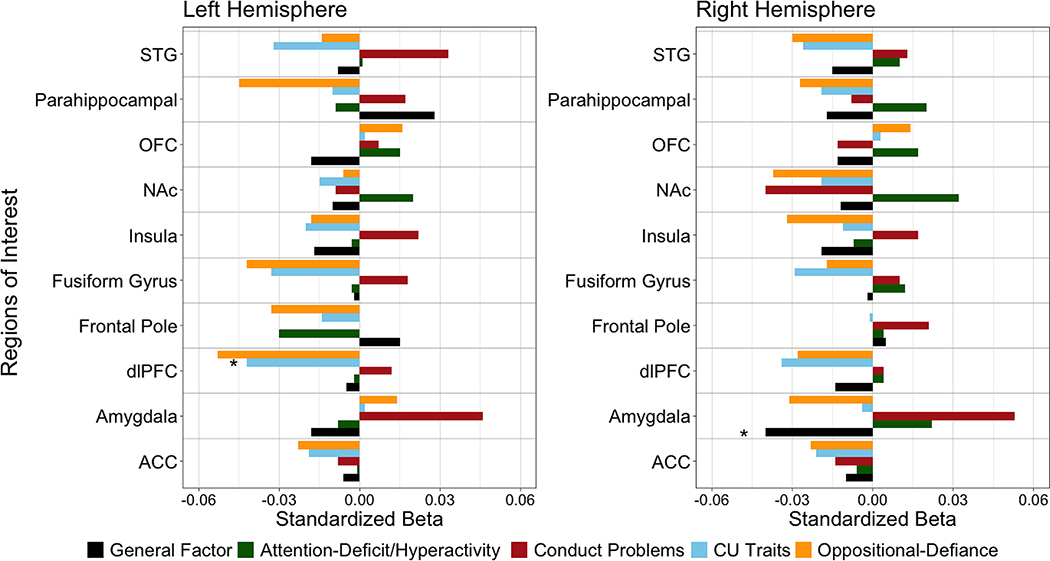

First, for the four-correlated factor model, higher ODD scores were associated with reduced right amygdala activation, higher CU traits scores were associated with reduced bilateral dlPFC activation (Table S9), and higher ADHD scores were associated with increased right NAc activation (Table S9). No other associations survived FDR correction (Table S9). Second, for the second-order model, higher general externalizing scores were associated with reduced right amygdala activation, although this finding did not survive FDR correction (Table S10). Third, within the bifactor model, higher general externalizing scores were associated with reduced right amygdala activation (Figure 2, Table S11). In addition, higher CU traits scores were associated with reduced left dlPFC activation (Figure 2, Table S11). In sum, for fearful faces, there was evidence of consistent brain-behavior associations across models, with decreased right amygdala activation associated with higher ODD scores in the four-correlated factor model and higher general externalizing scores in the second-order and bifactor models. Further, reduced left dlPFC activation was linked to higher CU traits in the four-correlated factor and bifactor models (Tables S9–11). The ADHD factor was associated with increased right NAc activation only in the four-correlated factor model.

Figure 2.

Differential associations between general externalizing, specific attention-deficit/hyperactivity, oppositional defiance, conduct problems, and CU traits, scores and neural activation in the right and left hemispheres during emotion processing of fearful faces versus neutral faces

Note. Standardized estimates from the correlated dependent variable models of brain-behavior associations for fearful versus neutral contrast for both hemispheres. Models controlled for age, sex, income, minoritized status, and task accuracy (Table S9). ACC=anterior cingulate cortex; CU=Callous-unemotional; dlPFC=Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex; G= General Externalizing Factor; NAc=Nucleus Accumbens; OFC=Orbitofrontal Cortex; STG=Superior Temporal Gyrus. *p<.05 following FDR correction

Happy versus neutral faces contrast.

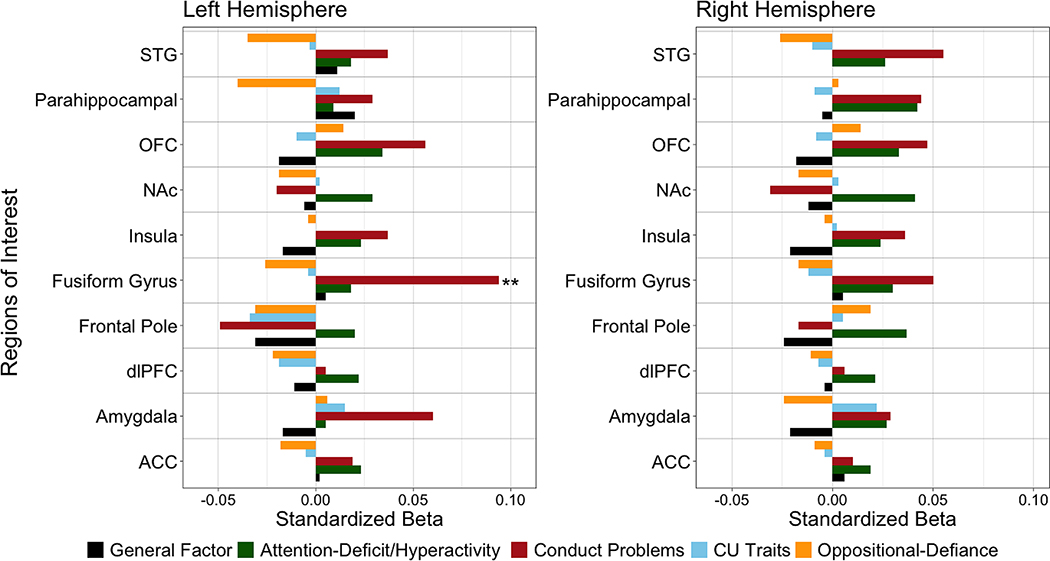

For the four-correlated factor model, only higher ADHD scores were associated with increased right NAc activation (Table S9). For the bifactor model, higher specific CD scores were associated with increased left fusiform gyrus activation (Figure 3, Table S11).

Figure 3.

Differential associations between general externalizing, specific attention-deficit/hyperactivity, oppositional defiance, conduct problems, and CU traits, scores and neural activation in the right and left hemispheres during emotion processing of happy faces versus neutral faces

Note. Standardized estimates from the correlated dependent variable models of brain-behavior associations for fearful versus neutral contrast for the both hemispheres. Models controlled for age, sex, income, minoritized status, and task accuracy (Table S9). ACC=anterior cingulate cortex; CU=Callous-unemotional; dlPFC=Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex; G=General Externalizing Factor; NAc=Nucleus Accumbens; OFC=Orbitofrontal Cortex; STG=Superior Temporal Gyrus. *p<.05, **p<.01 following FDR correction

Sensitivity Analyses: DBD Sample

Among the 1,799 children meeting criteria for past/current DBD diagnosis, the bifactor model demonstrated excellent fit (χ2(433)= 2,126.43; CFI=.95; TLI=.94; RMSEA=.05), while the second-order (χ2(458)= 3,426.07; CFI=.91; TLI=.90; RMSEA=.06) and four-correlated (χ2(456)= 3,382.83; CFI=.91; TLI=.91; RMSEA=.06) factor models demonstrated acceptable fit (Tables S12–13).

DBD Sample: fearful versus neutral faces contrast.

For the four-correlated factor model, higher ODD scores were associated with decreased left dlPFC activation and higher ADHD scores were associated with increased left dlPFC and left insula activation (Table S14). No associations emerged for the second-order model (Table S15). For the bifactor model, higher specific ODD scores were associated with reduced left dlPFC activation (Table S16). In sum, across both the four-correlated factor and bifactor models, higher ODD scores were associated with reduced left dlPFC activation. ADHD scores were associated with increased left dlPFC and left insula activation only in the four-correlated factor model.

DBD Sample: happy versus neutral faces contrast.

First, for the four-correlated factor model, higher ODD scores were associated with decreased right dlPFC and decreased bilateral insula activation. In addition, higher ADHD scores were associated with increased bilateral ACC, dlPFC, fusiform gyrus, insula, OFC, parahippocampal gyrus, and STG activation, as well as increased right NAc activation (Table S14). No significant associations emerged for the second-order model (Table S15). For the bifactor model, higher specific ODD scores were associated with decreased right dlPFC activation. In addition, higher specific ADHD scores were associated with increased bilateral ACC, fusiform gyrus, insula, OFC, and STG activation, as well as increased left dlPFC activation. Further, higher specific CU traits scores were associated with reduced bilateral dlPFC activation (Table S16). In sum, there was some consistency in brain-behavior associations for happy faces across the four-correlated factor and bifactor models, particularly for links between ODD and decreased right dlPFC activation. Likewise, across models, ADHD scores were consistently associated with increased ACC, dlPFC, fusiform gyrus, insula, OFC, and STG activation. However, higher CU traits scores were only associated with reduced bilateral dlPFC activation to happy faces in the bifactor model, while higher ODD scores were associated with reduced bilateral insula activation only in the four-correlated factor model.

Table 1 presents a summary of all findings across different model solutions and subsamples. See Supplemental Results and Tables S17–22 for analyses within the non-DBD subsample. Findings were similar when we did not control for task accuracy (see Table S23).

Table 1.

Summary of neural findings by study sample

| Full Sample | DBD Sample | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-Correlated | Second-Order | Bifactor | Four-Correlated | Second-Order | Bifactor | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Fearful | Happy | Fearful | Happy | Fearful | Happy | Fearful | Happy | Fearful | Happy | Fearful | Happy | ||

|

| |||||||||||||

| ACC | L | ↑ADHD | ↓ODD ↑ADHD |

↑ADHD ↓ODD |

|||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| R | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | |||||||||||

| Amygdala | L | ↑CD | ↓G ↑ADHD |

||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| R | ↓ODD | ↓G | ↓G | ↑CD | |||||||||

| dlPFC | L | ↓CU | ↓CU |

↓ODD

↑ADHD |

↑ADHD | ↓ODD |

↑ADHD

↓CU |

||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| R | ↓CU | ↓CU |

↓ODD

↑ADHD |

↓ODD

↓CU |

|||||||||

| Frontal Pole | L | ↓G | ↓CU | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| R | |||||||||||||

| Fusiform Gyrus | L | ↓CU | ↓CU | ↑CD | ↓ ODD ↑ADHD |

↓G ↑ADHD |

|||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| R | ↓CU | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | |||||||||

| Insula | L | ↑ADHD |

↓ODD

↑ADHD |

↓G ↑ADHD ↓CU |

|||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| R |

↓ ODD

↑ADHD |

↓G ↑ADHD |

|||||||||||

| NAc | L | ↑ADHD | ↓CU | ↑ADHD | ↑ ADHD | ↑ADHD | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| R | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | ||||||||

| OFC | L | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | ↓G ↑ADHD |

|||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| R | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | |||||||||||

| PH | L | ↑CD | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| R | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | ||||||||||

| STG | L | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| R | ↑ADHD | ↑ADHD | |||||||||||

Note. Brain-behavior associations across structural models (i.e., four-correlated factor, second-order, and bifactor models) and sample. ↑= higher factor scores relate to increased activation. ↓=higher factor scores relate to decreased activation. Bolded values indicate findings that survived FDR correction. ACC=anterior cingulate cortex; ADHD=Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; CD=Conduct Problems Disorder; CU=Callous-unemotional traits; DBD=disruptive behavior disorder; dlPFC=Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex; G=General Externalizing Factor; NAc=Nucleus Accumbens; ODD=Oppositional-Defiance Disorder; OFC=Orbitofrontal Cortex; PH= Parahippocampus; STG=Superior Temporal Gyrus.

Discussion

We examined shared and unique neural correlates of externalizing problems, focusing on symptoms of CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits and comparing brain-behavior associations across structural models. We demonstrated that the fit of a four-correlated factor, second-order factor, and bifactor model were each superior to a one-factor model, providing evidence for both multidimensionality and shared variance between CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits. Notably, while the bifactor model demonstrated superior fit to other models, this finding could be reflective of bifactor models often “overfitting” data given their higher number of parameters (Markon, 2019). Thus, we retained each model solution to better evaluate brain-behavior associations in relation to externalizing psychopathology. An improved understanding of shared versus unique brain-behavior associations for symptoms within the externalizing spectra can help guide our conceptualizations of transdiagnostic processes and the development of more specific diagnostic procedures or interventions (Caspi & Moffitt, 2018).

First, decreased right amygdala activation to fearful versus neutral faces was associated with higher general factor scores in the second-order and bifactor models, and to higher ODD scores in the four-correlated factor model. These findings suggest that general externalizing psychopathology, driven by severity of ODD symptoms, is associated with decreased amygdala responsivity to fearful emotional expressions. Findings are consistent with a large body of literature emphasizing the role of the amygdala in emotional responding and learning (Davis & Whalen, 2001), which are processes that are disrupted among children with difficulties across the externalizing spectrum (Hartmann & Schwenck, 2020; Morawetz et al., 2020; Stringaris et al., 2018). Moreover, disrupted amygdala activation appears to be a consistent marker of externalizing psychopathology in children and adolescents (Berluti et al., 2023; Efferson & Glenn, 2017).

In contrast to hypotheses (Cardinale et al., 2019; Marsh et al., 2008; Viding et al., 2012; White et al., 2012), CU traits were not significantly associated with amygdala activity to fearful faces. This point remained true across all models. Our results echo those of a recent meta-analysis of 23 studies, which found no overall association between CU traits and amygdala functioning (Berluti et al., 2023). However, we provide evidence that reduced amygdala reactivity to fearful faces may be a neural marker for general severity in externalizing psychopathology, represented either by a general factor capturing variance shared by items assessing CD, ODD, ADHD, and CU traits, or by specific variance in ODD symptoms, at least in 9–10-year-old children. At the same time, we found almost no other significant brain-behavior associations between neural activation to emotional faces and a general externalizing psychopathology factor, bifactor or hierarchical, after correcting for multiple comparisons. These null findings emphasize the importance of modeling multiple (albeit correlated) specific factors to characterize shared and unique variance relevant to brain-behavior associations. In addition, future longitudinal studies are needed to assess how changes between brain functioning and increasing severity of externalizing symptomatology unfold over time using trajectory-based approaches.

Second, CU traits were significantly associated with reduced dlPFC activation to fearful faces across models. The dlPFC is implicated in reward receipt and reward learning (Wilson et al., 2018), which are both processes that appear disrupted among children with CU traits, especially in the context of fear learning (Waller & Wagner, 2019). Associations between reduced activation in the dlPFC and higher CU traits may be indicative of a lower motivational salience of fearful faces, which would otherwise guide adaptive social behavior. This interpretation is consistent with work that identified reduced dlPFC activation during emotion regulation among children with CD and CU traits, although direct associations with CU traits were not found (Raschle et al., 2019). Higher CU traits were also associated with decreased left fusiform gyrus activation to fearful faces across models, although findings did not survive multiple comparisons correction and should be interpreted with caution. However, it is notable that a prior meta-analysis also linked higher CU traits to reduced left fusiform gyrus activation to emotional faces (Berluti et al., 2023), with the fusiform gyrus implicated in human face perception (Rossion et al., 2023) and recognition (Rossion & Lochy, 2022).

Among the DBD sample, CU traits were also associated with reduced bilateral dlPFC activation to happy, relative to neutral, faces. Few prior studies have investigated neural responses to happy faces and CU traits, with inconsistent findings (Dotterer et al., 2017; Efferson & Glenn, 2017). However, much prior research has implicated the dlPFC in the regulation of positive emotions, including within the context of depression and anhedonia (Light et al., 2019; Taylor & Liberzon, 2007), with reduced dlPFC activation to happy faces linked to increased risk for adolescent depression (Kerestes et al., 2016). Children with CU traits also exhibit affiliation difficulties responding to positive social cues (O’Nions et al., 2017; Waller & Wagner, 2019), though the mechanisms underlying these affiliation difficulties are likely different to those for depression (Paz et al., 2024). Thus, future studies need to investigate individual differences in the neural representation of social or facial cues of emotion that signal fear, distress, positive engagement (e.g., happiness), or social bonding (e.g., laughter) in relation to CU traits. Indeed, while children with externalizing problems and CU traits improve following treatment, particularly those with a parenting component, they begin and end treatment with more externalizing symptoms than children with low CU traits (Perlstein et al., 2023). Thus, specialized treatment modules are needed that address the greater symptom severity associated with CU traits, including by targeting fearful and happy emotion processing (Rossion et al., 2023).

Third, we found consistent associations across models between higher ADHD scores and increased right NAc activation to happy faces, including among children with a past/current DBD diagnosis. The NAc is implicated in behaviors related to reward (Salgado & Kaplitt, 2015) and impulsivity (Basar et al., 2010), which overlap with ADHD symptomatology. In addition, higher ADHD scores were associated with increased activation in the right parahippocampal gyrus to happy faces for both the four-correlated factor and bifactor models. In the DBD subsample, higher ADHD scores were also linked to increased bilateral ACC, left dlPFC, bilateral insula, bilateral OFC, and bilateral STG activation to happy faces, with findings consistent across the four-correlated factor and bifactor models. That is, with increasing DBD severity, ADHD appears to be underpinned by broad hyperactivity to happy faces across regions. Although prior research examining associations between ADHD and neural responses to positive emotional cues is limited, studies have reported associations between childhood ADHD and hyperresponsiveness to positive emotional stimuli when operationalized by pupil dilation (Kleberg et al., 2021), changes in oxyhemoglobin (Ichikawa et al., 2014), and event-related potentials (López-Martín et al., 2013). Future fMRI studies are needed to confirm findings across tasks and sample types. Notably, our fMRI paradigm differs from prior neuroimaging studies of emotion processing by capturing implicit face emotion processing in the context of working memory (Barch et al., 2013). Prior studies suggest that children and adults with ADHD have executive function difficulties, including during working memory tasks (Welsh & Peterson, 2014), with evidence that ADHD symptoms correlate with emotional distractibility during executive functioning tasks that feature goal-irrelevant affective stimuli (López-Martín et al., 2013; Vetter et al., 2018). Our findings also suggest an association between ADHD and emotional distractibility, especially since ADHD was associated with worse task performance alongside hyperresponsivity to happy faces across brain regions.

Our findings should be considered alongside several limitations. First, the majority of effects were very small in the context of established metrics (Cohen, 1988). However, an investigation of effect-size distributions within the ABCD study reported r=.03 as the median effect size, with r=.07 representing a large effect (Owens et al., 2021), which is largely consistent with those we report. Effect sizes also increased in magnitude when the sample was restricted to children with a past/current DBD diagnosis. For example, within the DBD subsample and the four-correlated factor model, an increase of one standard deviation for the ODD factor score corresponded to a .32 standard deviation decrease in right insula activation to fearful faces. Second, although the ABCD study used a complex probability sampling design to maximize generalizability, there are known discrepancies in the sociodemographic features of the sample with usable functional imaging data when compared to 8–11 year-olds in the US population (Gard et al., 2023). Future studies need to replicate our findings in more representative samples, as well as in clinical populations with greater externalizing symptom severity. Third, our CU traits measure included only four items and may have been limited in capturing the full range of the CU traits construct. Fourth, the fMRI paradigm we used was designed to assess working memory and implicit face emotion processing, contrasting with more traditional emotion processing fMRI tasks (Berluti et al., 2023; White et al., 2012). Fifth, we found somewhat different results across models comparing the full sample and the DBD sub-sample. These differences cement the importance of considering how the low incidence of severe externalizing problems within community samples might impact findings, or by the same token, how results from prior studies of very small case-control studies of children with CD or ODD may not be replicable. Sixth, for better or worse, we demonstrated “the perils of partialling” (Lynam et al., 2006), most notably with different findings linking CD scores to the likelihood of having a DBD diagnosis: reduced likelihood in the bifactor model and increased likelihood in the four-correlated factor model. These results, alongside subtle differences in the pattern of brain-behavior associations across models, reiterate the need for caution when evaluating results within a bifactor framework. In this case, once variance shared with ODD, ADHD, and CU traits was modeled, the remaining variance in the CD specific factor appears at best spurious, and at worse, indicative of a different phenotypic construct. Our presentation of brain-behavior associations across different factor models represents one approach for addressing potentially spurious associations when modeling shared versus unique variance in comorbid symptom profiles. Finally, the behavioral tasks commonly used within fMRI research can produce unreliable estimates when it comes to between person differences, especially when estimates require computing a difference score across two conditions, as was the case in our study (Dang et al., 2020; Elliott et al., 2020). Thus, an alternative explanation for the predominance of null findings presented here is that the task itself lacked the psychometric foundations needed to reliably detect individual differences, regardless of the large sample size. This concern raises additional difficulties for interpreting the findings of smaller prior studies in the field, which may also have leveraged measures with low reliability (Dang et al., 2020; Elliott et al., 2020).

In sum, reduced amygdala activation to fearful faces may underlie general risk for externalizing psychopathology in late childhood, while reduced dlPFC and fusiform activity to fearful faces may be specifically associated with CU traits and increased NAc activity to happy faces specifically associated with ADHD. Among youth with a past/current DBD, higher ADHD scores were associated with increased neural activity to happy versus neutral faces across a host of brain regions implicated in emotion processing. Our results inform the development of treatment modules for externalizing psychopathology that have universal components (e.g., parenting management training) and potential specialized modules for children with CU traits (e.g., training to better orient attention to positive and negative cues of emotion) and/or ADHD (e.g., improved regulation in the context of emotional stimuli).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive DevelopmentSM (ABCD) Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). This is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10,000 children aged 9–10 and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. The ABCD Study® is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041048, U01DA050989, U01DA051016, U01DA041022, U01DA051018, U01DA051037, U01DA050987, U01DA041174, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041028, U01DA041134, U01DA050988, U01DA051039, U01DA041156, U01DA041025, U01DA041120, U01DA051038, U01DA041148, U01DA041093, U01DA041089, U24DA041123, U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/consortium_members/. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in the analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators.

The ABCD data repository grows and changes over time. The ABCD data used in this report came from: http://dx.doi.org/10.15154/1523041.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). The manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R (2002). Neural systems for recognizing emotion. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 12(2), 169–177. 10.1016/S0959-4388(02)00301-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggensteiner P-M, Holz NE, Böttinger BW, Baumeister S, Hohmann S, Werhahn JE, Naaijen J, Ilbegi S, Glennon JC, Hoekstra PJ, Dietrich A, Deters RK, Saam MC, Schulze UME, Lythgoe DJ, Sethi A, Craig MC, Mastroianni M, Sagar-Ouriaghli I, … Brandeis D (2022). The effects of callous-unemotional traits and aggression subtypes on amygdala activity in response to negative faces. Psychological Medicine, 52(3), 476–484. 10.1017/S0033291720002111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari Nasab S, Panahi S, Ghassemi F, Jafari S, Rajagopal K, Ghosh D, & Perc M (2022). Functional neuronal networks reveal emotional processing differences in children with ADHD. Cognitive Neurodynamics, 16(1), 91–100. 10.1007/s11571-021-09699-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balia C, Carucci S, Coghill D, & Zuddas A (2018). The pharmacological treatment of aggression in children and adolescents with conduct disorder. Do callous—Unemotional traits modulate the efficacy of medication? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 91, 218–238. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Burgess GC, Harms MP, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL, Corbetta M, Glasser MF, Curtiss S, Dixit S, Feldt C, Nolan D, Bryant E, Hartley T, Footer O, Bjork JM, Poldrack R, Smith S, Johansen-Berg H, Snyder AZ, & Van Essen DC (2013). Function in the Human Connectome: Task-fMRI and Individual Differences in Behavior. NeuroImage, 80, 169–189. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basar K, Sesia T, Groenewegen H, Steinbusch HWM, Visser-Vandewalle V, & Temel Y (2010). Nucleus accumbens and impulsivity. Progress in Neurobiology, 92(4), 533–557. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berluti K, Ploe ML, & Marsh AA (2023). Emotion processing in youths with conduct problems: An fMRI meta-analysis. Translational Psychiatry, 13(1), Article 1. 10.1038/s41398-023-02363-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes CM, Herzhoff K, Smack AJ, & Tackett JL (2019). The p Factor and the n Factor: Associations Between the General Factors of Psychopathology and Neuroticism in Children. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1266–1284. 10.1177/2167702619859332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Rich BA, Guyer AE, Lunsford JR, Horsey SE, Reising MM, Thomas LA, Fromm SJ, Towbin K, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2010). Amygdala Activation During Emotion Processing of Neutral Faces in Children With Severe Mood Dysregulation Versus ADHD or Bipolar Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(1), 61–69. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA (2015). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, Second Edition. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale EM, O’Connell K, Robertson EL, Meena LB, Breeden AL, Lozier LM, VanMeter JW, & Marsh AA (2019). Callous and uncaring traits are associated with reductions in amygdala volume among youths with varying levels of conduct problems. Psychological Medicine, 49(9), 1449–1458. 10.1017/S0033291718001927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, & Moffitt TE (2018). All for One and One for All: Mental Disorders in One Dimension. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(9), 831–844. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17121383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1016/C2013-0-10517-X. [Google Scholar]

- Da Fonseca D, Seguier V, Santos A, Poinso F, & Deruelle C (2009). Emotion Understanding in Children with ADHD. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 40(1), 111–121. 10.1007/s10578-008-0114-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang J, King KM, & Inzlicht M (2020). Why Are Self-Report and Behavioral Measures Weakly Correlated? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(4), 267–269. 10.1016/j.tics.2020.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, & Whalen PJ (2001). The amygdala: Vigilance and emotion. Molecular Psychiatry, 6(1), Article 1. 10.1038/sj.mp.4000812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deming P, Heilicher M, & Koenigs M (2022). How reliable are amygdala findings in psychopathy? A systematic review of MRI studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 104875. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, & Killiany RJ (2006). An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage, 31(3), 968–980. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotterer HL, Hyde LW, Swartz JR, Hariri AR, & Williamson DE (2017). Amygdala reactivity predicts adolescent antisocial behavior but not callous-unemotional traits. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 24, 84–92. 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotterer HL, Waller R, Hein TC, Pardon A, Mitchell C, Lopez-Duran N, Monk CS, & Hyde LW (2020). Clarifying the Link Between Amygdala Functioning During Emotion Processing and Antisocial Behaviors Versus Callous-Unemotional Traits Within a Population-Based Community Sample. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(5), 918–935. 10.1177/2167702620922829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss M, Caudle K, Drysdale AT, Johnston NE, Cohen AO, Somerville LH, Galván A, Tottenham N, Hare TA, & Casey BJ (2014). Teens Impulsively React rather than Retreat from Threat. Developmental Neuroscience, 36(3–4), 220–227. 10.1159/000357755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy KA, Gandhi R, Falke C, Wiglesworth A, Mueller BA, Fiecas MB, Klimes-Dougan B, Luciana M, & Cullen KR (2023). Psychiatric Diagnoses and Treatment in Nine- to Ten-Year-Old Participants in the ABCD Study. JAACAP Open. 10.1016/j.jaacop.2023.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KJ, & McCray G (2020). The Place of the Bifactor Model in Confirmatory Factor Analysis Investigations Into Construct Dimensionality in Language Testing. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1357. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efferson LM, & Glenn AL (2017). The Neurobiology of Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder. In The Wiley Handbook of Disruptive and Impulse-Control Disorders (pp. 143–158). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 10.1002/9781119092254.ch9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott ML, Knodt AR, Ireland D, Morris ML, Poulton R, Ramrakha S, Sison ML, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, & Hariri AR (2020). What Is the Test-Retest Reliability of Common Task-Functional MRI Measures? New Empirical Evidence and a Meta-Analysis. Psychological Science, 31(7), 792–806. 10.1177/0956797620916786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyler LT, Pierce K, & Courchesne E (2012). A failure of left temporal cortex to specialize for language is an early emerging and fundamental property of autism. Brain, 135(3), 949–960. 10.1093/brain/awr364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanti KA, Mavrommatis I, Colins O, & Andershed H (2023). Fearlessness as an Underlying Mechanism Leading to Conduct Problems: Testing the Intermediate Effects of Parenting, Anxiety, and callous-unemotional Traits. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 51(8), 1115–1128. 10.1007/s10802-023-01076-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, van der Kouwe A, Killiany R, Kennedy D, Klaveness S, Montillo A, Makris N, Rosen B, & Dale AM (2002). Whole Brain Segmentation: Automated Labeling of Neuroanatomical Structures in the Human Brain. Neuron, 33(3), 341–355. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, & Marsee MA (2018). Psychopathy and developmental pathways to antisocial behavior in youth. In Handbook of psychopathy, 2nd ed (pp. 456–475). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, & Kahn RE (2014). Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 1. 10.1037/a0033076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard AM, Hyde LW, Heeringa SG, West BT, & Mitchell C (2023). Why weight? Analytic approaches for large-scale population neuroscience data. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 59, 101196. 10.1016/j.dcn.2023.101196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geckeler KC, Barch DM, & Karcher NR (2022). Associations between social behaviors and experiences with neural correlates of implicit emotion regulation in middle childhood. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(6), Article 6. 10.1038/s41386-022-01286-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbing DW, & Anderson JC (1992). Monte Carlo Evaluations of Goodness of Fit Indices for Structural Equation Models. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 132–160. 10.1177/0049124192021002002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyurak A, Gross JJ, & Etkin A (2011). Explicit and implicit emotion regulation: A dual-process framework. Cognition and Emotion, 25(3), 400–412. 10.1080/02699931.2010.544160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler DJ, Hatton SN, Makowski C, Cornejo MD, Fair DA, Dick AS, Sutherland MT, Casey B, Barch DM, Harms MP, Watts R, Bjork JM, Garavan HP, Hilmer L, Pung CJ, Sicat CS, Kuperman J, Bartsch H, Xue F, … Dale AM (2018). Image processing and analysis methods for the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study [Preprint]. Neuroscience. 10.1101/457739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann D, & Schwenck C (2020). Emotion processing in children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits: An investigation of speed, accuracy, and attention. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes SW, Byrd AL, Waller R, Lynam DR, & Pardini DA (2017). Late childhood interpersonal callousness and conduct problem trajectories interact to predict adult psychopathy. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(1), 55–63. 10.1111/jcpp.12598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes SW, Waller R, Thompson WK, Hyde LW, Byrd AL, Burt SA, Klump KL, & Gonzalez R (2020). Assessing callous-unemotional traits: Development of a brief, reliable measure in a large and diverse sample of preadolescent youth. Psychological Medicine, 50(3), 456–464. 10.1017/S0033291719000278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H, Nakato E, Kanazawa S, Shimamura K, Sakuta Y, Sakuta R, Yamaguchi MK, & Kakigi R (2014). Hemodynamic response of children with attention-deficit and hyperactive disorder (ADHD) to emotional facial expressions. Neuropsychologia, 63, 51–58. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RE, Frick PJ, Youngstrom EA, Youngstrom JK, Feeny NC, & Findling RL (2013). Distinguishing Primary and Secondary Variants of Callous Unemotional Traits among Adolescents in a Clinic-referred Sample. Psychological Assessment, 25(3), 966–978. 10.1037/a0032880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerestes R, Segreti AM, Pan LA, Phillips ML, Birmaher B, Brent DA, & Ladouceur CD (2016). Altered Neural Function to Happy Faces in Adolescents with and at Risk for Depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 192, 143–152. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircanski K, White LK, Tseng W-L, Wiggins JL, Frank HR, Sequeira S, Zhang S, Abend R, Towbin KE, Stringaris A, Pine DS, Leibenluft E, & Brotman MA (2018). A Latent Variable Approach to Differentiating Neural Mechanisms of Irritability and Anxiety in Youth. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(6), 631–639. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleberg JL, Frick MA, & Brocki KC (2021). Increased pupil dilation to happy faces in children with hyperactive/impulsive symptoms of ADHD. Development and Psychopathology, 33(3), 767–777. 10.1017/S0954579420000036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hobbs KA, Conway CC, Dick DM, Dretsch MN, Eaton NR, Forbes MK, Forbush KT, Keyes KM, Latzman RD, Michelini G, Patrick CJ, Sellbom M, Slade T, South SC, Sunderland M, Tackett J, Waldman I, Waszczuk MA, … HiTOP Utility Workgroup. (2021). Validity and utility of Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): II. Externalizing superspectrum. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 20(2), 171–193. 10.1002/wps.20844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light SN, Bieliauskas LA, & Taylor SF (2019). Measuring change in anhedonia using the “Happy Faces” task pre- to post-repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) treatment to left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): Relation to empathic happiness. Translational Psychiatry, 9, 217. 10.1038/s41398-019-0549-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Martín S, Albert J, Fernández-Jaén A, & Carretié L (2013). Emotional distraction in boys with ADHD: Neural and behavioral correlates. Brain and Cognition, 83(1), 10–20. 10.1016/j.bandc.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozier LM, Cardinale EM, VanMeter JW, & Marsh AA (2014). Mediation of the Relationship Between Callous-Unemotional Traits and Proactive Aggression by Amygdala Response to Fear Among Children With Conduct Problems. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(6), 627–636. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE (2019). Bifactor and Hierarchical Models: Specification, Inference, and Interpretation. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15, 51–69. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, & Blair RJR (2008). Deficits in facial affect recognition among antisocial populations: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(3), 454–465. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Finger EC, Mitchell DGV, Reid ME, Sims C, Kosson DS, Towbin KE, Leibenluft E, Pine DS, & Blair R. J. r. (2008). Reduced Amygdala Response to Fearful Expressions in Children and Adolescents With Callous-Unemotional Traits and Disruptive Behavior Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(6), 712–720. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew KS (2009). CHC theory and the human cognitive abilities project: Standing on the shoulders of the giants of psychometric intelligence research. Intelligence, 37(1), 1–10. 10.1016/j.intell.2008.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Witkiewitz K, & Kotler JS (2010). Predictive Validity of Callous-unemotional Traits Measured in Early Adolescence with Respect to Multiple Antisocial Outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119(4), 752–763. 10.1037/a0020796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AA, Blair RJ, Hettema JM, & Roberson-Nay R (2019). The genetic underpinnings of callous-unemotional traits: A systematic research review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 100, 85–97. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawetz C, Riedel MC, Salo T, Berboth S, Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, & Kohn N (2020). Multiple large-scale neural networks underlying emotion regulation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 116, 382–395. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables, User’s Guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Noordermeer SDS, Luman M, & Oosterlaan J (2016). A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Neuroimaging in Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) and Conduct Disorder (CD) Taking Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Into Account. Neuropsychology Review, 26(1), 44–72. 10.1007/s11065-015-9315-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien KJ, Barch DM, Kandala S, & Karcher NR (2020). Examining Specificity of Neural Correlates of Childhood Psychotic-like Experiences During an Emotional n-Back Task. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 5(6), 580–590. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Nions E, Lima CF, Scott SK, Roberts R, McCrory EJ, & Viding E (2017). Reduced Laughter Contagion in Boys at Risk for Psychopathy. Current Biology, 27(19), 3049–3055.e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orri M, Galera C, Turecki G, Boivin M, Tremblay RE, Geoffroy M-C, & Côté SM (2019). Pathways of Association Between Childhood Irritability and Adolescent Suicidality. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(1), 99–107.e3. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MM, Potter A, Hyatt CS, Albaugh M, Thompson WK, Jernigan T, Yuan D, Hahn S, Allgaier N, & Garavan H (2021). Recalibrating expectations about effect size: A multi-method survey of effect sizes in the ABCD study. PLOS ONE, 16(9), e0257535. 10.1371/journal.pone.0257535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz Y, Perkins ER, Colins O, Perlstein S, Wagner NJ, Hawes SW, Byrd AL, Viding E, & Waller R (2024). Evaluating the Sensitivity to Threat and Affiliative Reward (STAR) Model in the ABCD Study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 10.1111/jcpp.13976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlstein S, Fair M, Hong E, & Waller R (2023). Treatment of childhood disruptive behavior disorders and callous-unemotional traits: A systematic review and two multilevel meta-analyses. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 10.1111/jcpp.13774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlstein S, Hawes S, Byrd AL, Barzilay R, Gur R, Laird A, & Waller R (2024, April 6). Unique Versus Shared Neural Correlates of Externalizing Psychopathology in Late- Childhood. Retrieved from osf.io/enp2d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi E, Vijayakumar N, Rakesh D, & Whittle S (2021). Neural Correlates of Emotion Regulation in Adolescents and Emerging Adults: A Meta-analytic Study. Biological Psychiatry, 89(2), 194–204. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschle NM, Fehlbaum LV, Menks WM, Martinelli A, Prätzlich M, Bernhard A, Ackermann K, Freitag C, De Brito S, Fairchild G, & Stadler C (2019). Atypical Dorsolateral Prefrontal Activity in Female Adolescents With Conduct Disorder During Effortful Emotion Regulation. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 4(11), 984–994. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2019.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehder PD, Mills-Koonce WR, Willoughby MT, Garrett-Peters P, & Wagner NJ (2017). Emotion Recognition Deficits among Children with Conduct Problems and Callous-Unemotional Behaviors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 41, 174–183. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B, Jacques C, & Jonas J (2023). Intracerebral Electrophysiological Recordings to Understand the Neural Basis of Human Face Recognition. Brain Sciences, 13(2), Article 2. 10.3390/brainsci13020354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B, & Lochy A (2022). Is human face recognition lateralized to the right hemisphere due to neural competition with left-lateralized visual word recognition? A critical review. Brain Structure and Function, 227(2), 599–629. 10.1007/s00429-021-02370-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado S, & Kaplitt MG (2015). The Nucleus Accumbens: A Comprehensive Review. Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery, 93(2), 75–93. 10.1159/000368279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenck C, Gensthaler A, Romanos M, Freitag CM, Schneider W, & Taurines R (2014). Emotion recognition in girls with conduct problems. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(1), 13–22. 10.1007/s00787-013-0416-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff AI, Luman M, van der Oord S, Bergwerff CE, van den Hoofdakker BJ, & Oosterlaan J (2022). Facial emotion recognition impairment predicts social and emotional problems in children with (subthreshold) ADHD. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(5), 715–727. 10.1007/s00787-020-01709-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, & Leibenluft E (2018). Practitioner Review: Definition, recognition, and treatment challenges of irritability in young people. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(7), 721–739. 10.1111/jcpp.12823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura T, & Hanakawa T (2017). Clinical utility of resting-state functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging for mood and cognitive disorders. Journal of Neural Transmission, 124(7), 821–839. 10.1007/s00702-017-1710-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, & Liberzon I (2007). Neural correlates of emotion regulation in psychopathology. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(10), 413–418. 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend L, Kobak K, Kearney C, Milham M, Andreotti C, Escalera J, Alexander L, Gill MK, Birmaher B, Sylvester R, Rice D, Deep A, & Kaufman J (2020). Development of Three Web-Based Computerized Versions of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Child Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview: Preliminary Validity Data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(2), 309–325. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbach RH, & Tottenham N (2021). Callous-unemotional traits and reduced default mode network connectivity within a community sample of children | Development and Psychopathology | Cambridge Core. Development and Psychopathology, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter NC, Buse J, Backhausen LL, Rubia K, Smolka MN, & Roessner V (2018). Anterior insula hyperactivation in ADHD when faced with distracting negative stimuli. Human Brain Mapping, 39(7), 2972–2986. 10.1002/hbm.24053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viding E, Sebastian CL, Dadds MR, Lockwood PL, Cecil CAM, De Brito SA, & McCrory EJ (2012). Amygdala Response to Preattentive Masked Fear in Children With Conduct Problems: The Role of Callous-Unemotional Traits. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(10), 1109–1116. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viering T, Naaijen J, van Rooij D, Thiel C, Philipsen A, Dietrich A, Franke B, Buitelaar J, & Hoekstra PJ (2022). Amygdala reactivity and ventromedial prefrontal cortex coupling in the processing of emotional face stimuli in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(12), 1895–1907. 10.1007/s00787-021-01809-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, & Hyde LW (2018). Callous-unemotional behaviors in early childhood: The development of empathy and prosociality gone awry. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 11–16. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, & Wagner N (2019). The Sensitivity to Threat and Affiliative Reward (STAR) model and the development of callous-unemotional traits. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 656–671. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschbusch DA, Baweja R, Babinski DE, Mayes SD, & Waxmonsky JG (2020). Irritability and Limited Prosocial Emotions/Callous-Unemotional Traits in Elementary-School-Age Children. Behavior Therapy, 51(2), 223–237. 10.1016/j.beth.2019.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh M, & Peterson E (2014). Issues in the Conceptualization and Assessment of Hot Executive Functions in Childhood. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 20(2), 152–156. 10.1017/S1355617713001379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SF, Marsh AA, Fowler KA, Schechter JC, Adalio C, Pope K, Sinclair S, Pine DS, & Blair RJR (2012). Reduced Amygdala Response in Youths With Disruptive Behavior Disorders and Psychopathic Traits: Decreased Emotional Response Versus Increased Top-Down Attention to Nonemotional Features. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(7), 750–758. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RP, Colizzi M, Bossong MG, Allen P, Kempton M, Abe N, Barros-Loscertales AR, Bayer J, Beck A, Bjork J, Boecker R, Bustamante JC, Choi JS, Delmonte S, Dillon D, Figee M, Garavan H, Hagele C, Hermans EJ, … MTAC. (2018). The Neural Substrate of Reward Anticipation in Health: A Meta-Analysis of fMRI Findings in the Monetary Incentive Delay Task. Neuropsychology Review, 28(4), 496–506. 10.1007/s11065-018-9385-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymbs BT, McCarty CA, King KM, McCauley E, Vander Stoep A, Baer JS, & Waschbusch DA (2012). Callous-Unemotional Traits as Unique Prospective Risk Factors for Substance Use in Early Adolescent Boys and Girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(7), 1099–1110. 10.1007/s10802-012-9628-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Sun T, Cao M, & Drasgow F (2021). Using Bifactor Models to Examine the Predictive Validity of Hierarchical Constructs: Pros, Cons, and Solutions. Organizational Research Methods, 24(3), 530–571. 10.1177/1094428120915522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.