Abstract

Background and purpose

A mobile stroke unit (MSU) reduces delays in stroke treatment by allowing thrombolysis on board and avoiding secondary transports. Due to the beneficial effect in comparison to conventional emergency medical services, current guidelines recommend regional evaluation of MSU implementation.

Methods

In a descriptive study, current pathways of patients requiring a secondary transport for mechanical thrombectomy were reconstructed from individual patient records within a Danish (n = 122) and an adjacent German region (n = 80). Relevant timestamps included arrival times (on site, primary hospital, thrombectomy centre) as well as the initiation of acute therapy. An optimal MSU location for each region was determined. The resulting time saving was translated into averted disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs).

Results

For each region, the optimal MSU location required a median driving time of 35 min to a stroke patient. Time savings in the German region (median [Q1; Q3]) were 7 min (−15; 31) for thrombolysis and 35 min (15; 61) for thrombectomy. In the Danish region, the corresponding time savings were 20 min (8; 30) and 43 min (25; 66). Assuming 28 thrombectomy cases and 52 thrombolysis cases this would translate to 9.4 averted DALYs per year justifying an annual net MSU budget of $0.8M purchasing power parity dollars (PPP‐$) in the German region. In the Danish region, the MSU would avert 17.7 DALYs, justifying an annual net budget of PPP‐$1.7M.

Conclusion

The effects of an MSU can be calculated from individual patient pathways and reflect differences in the hospital infrastructure between Denmark and Germany.

Keywords: drip and ship model, mobile stroke unit, stroke, thrombectomy, thrombolysis

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is a major burden for the European Union with an annual incidence of 1.12 million accounting for an annual 7.06 million disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) [1]. For ischaemic stroke, thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy have improved outcome to a large degree, shifting eligible patients towards survival without or with only minor symptoms, especially if administered at an early time point [2, 3]. Statistically, every minute from stroke onset to acute therapy will avert DALYs to an extent that has been calculated for both thrombolysis [4] and mechanical thrombectomy [5]. Therefore, every minute counts when it comes to diagnosing and treating stroke. A rapid and determined interaction within the rescue chain, from first contact to emergency medical services (EMS) to rapid transport to the hospital and treatment by physicians, is elementary to maximize chances for a good outcome.

At centre stage of this interaction is the implementation of a mobile stroke unit (MSU) capable of performing computed tomography (CT) on site [6]. Introduced as a concept two decades ago [7], an MSU has been shown to shorten time to treatment decision [8], thrombolysis [9] and—due to onsite availability of CT angiography and better triage pathways—to mechanical thrombectomy [10]. Finally, two large controlled clinical trials have elevated the MSU concept to a new evidence level by demonstrating a better outcome in stroke patients [11, 12]. MSU dispatch has been shown to improve functional outcome even when including patients with transient ischaemic attack and haemorrhagic stroke [13]. A meta‐analysis rendered a 65% increase in the odds of an excellent outcome [14]. Therefore, the current guideline of the European Stroke Organization recommends evaluation of MSU implementation for optimized stroke care [6].

A de novo MSU project has to take the existing regional infrastructure of stroke care into account, regarding, amongst others, regional stroke incidence, density of location of hospitals with thrombolysis capacity and hospitals providing mechanical thrombectomy. In contrast to Denmark with a centralized system, Germany provides more hospitals with less specialization with the apparent advantage of a shorter travel time for patients in rural areas [15]. This difference may also affect the impact of an MSU on time to thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy. The goal of this study was a parallel evaluation of a future MSU implementation in similar and adjacent regions in southern Denmark and northern Germany. Using the same methods, pathways of current stroke patients were analysed and these data were used to find an optimal location for a future MSU. To quantify and compare possible benefits, the effect of a future MSU on time to treatment as well as averted DALYs was estimated for each region.

METHODS

For this descriptive study routinely acquired standard clinical data were analysed for quality management purposes at two high volume stroke centres providing acute therapies in the Danish and the German Fehmarn Belt border region. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and after positive approval of the local ethical committees. The Danish stroke centre was the Zealand University Hospital, Campus Roskilde, and the German stroke centre was the University Hospital Schleswig‐Holstein, Campus Lübeck. To provide and optimize stroke care, both centres have established local registries for all patients treated with thrombolysis and/or thrombectomy. As part of the clinical routine, all relevant timestamps from stroke onset to acute therapy initiation were entered if available. The population densities of both regions are of comparable magnitude: 145/km2 in the German region [16] and 120/km2 in the Danish region [17]. Hospital landscape and assignment in stroke therapy differ between the catchment areas of the two centres (Figure 1a). All patients admitted to the Danish centre were brought by Emergency Medical Systems without a hospital service upstream. Therefore, the Danish centre functions as a primary hospital in stroke patient flow where initial imaging is performed followed by decision on thrombolysis or thrombectomy. Thrombolysis is administered at the primary hospital. If thrombectomy is indicated, the patient is admitted to the cooperating thrombectomy centre at the University of Copenhagen with a secondary transport. The German centre is a thrombectomy centre. About one‐third of the patients treated with thrombectomy are sent from one of seven primary hospitals within the German study region. In these primary hospitals, imaging is performed and thrombolysis initiated if indicated, followed by a secondary transport to the thrombectomy centre.

FIGURE 1.

Mapping of patient pathways. The two study regions are located adjacent to each other on the two sides of the Fehmarn Belt (a). Hospital landscapes and patient locations are displayed for the German region (b) and the Danish region (c), both inhabited by about 500,000 people. Blue points denote individual locations of stroke patients who have been treated in the thrombectomy centre of the University of Lübeck (triangle in left map) and in the thrombectomy centre of the University of Copenhagen (triangle in right map). Plus symbols show the positions of the seven primary hospitals in Germany and the single primary hospital in Denmark. Patients were admitted to a primary hospital first. After initial imaging and thrombolysis (if applicable) they were brought to the thrombectomy centre with a secondary transport. This real‐world situation was compared to a hypothetical MSU pathway that starts thrombolysis at the patient location and admits them directly to the thrombectomy centre, bypassing the primary hospital. The red ambulance symbol denotes the optimized MSU location rendered by AI using the Nelder–Mead algorithm.

The goal of this study was to describe a high precision hypothetical MSU pathway for patients requiring a secondary transport for mechanical thrombectomy in each region. Therefore, the registries of both centres were screened for patients with a complete and detailed documentation of prehospital management. This includes the exact position where the patient was found as well as the following timestamps: last well seen from normal, time of 112 call (EMS call in Germany and Denmark), arrival of EMS at the patient's location, arrival of EMS at primary hospital, start of thrombolysis (if applicable), departure of secondary transport to thrombectomy centre, arrival of secondary transport at thrombectomy centre, start of thrombectomy (groin puncture). Since documentation in the Danish region has been digitized recently, it included a high percentage of patients with documented time of EMS departure to the primary hospital that were included in the study. In the German region, this departure time was reconstructed by subtracting the estimated driving time (see below) from the time of arrival at the primary hospital. Further standard clinical parameters routinely documented in the registry and included in our study were age, sex, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) at admission in primary hospital, anterior stroke (internal carotid artery, M1, M2) and posterior stroke (basilar artery).

Inclusion criteria for both cohorts were out of hospital stroke patients with the need of secondary transport for thrombectomy (Figure 2). Exclusion criteria were airborne transport or incomplete documentation of prehospital management regarding the parameters above. In the Danish region, all 127 consecutive patients with secondary transport for thrombectomy from January 2018 to April 2021 were screened. The advanced digitalization led to a high level of documentation with only five patients having to be excluded due to incomplete prehospital documentation. In contrast, the German region had a relatively low number of patients with complete prehospital documentation. In order to achieve an acceptable cohort size, all 318 consecutive patients with secondary transport for thrombectomy from January 2014 to January 2020 were screened. Two patients were excluded because their transport was airborne. In addition, 236 patients were excluded because of insufficient prehospital documentation. As a result of the screening process, study cohort sizes were 80 and 122 for the German and Danish region respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Flowchart displaying inclusion and exclusion of patients in the two cohorts.

To estimate the effect of an MSU within each region, two main analysing steps were performed. In a first step, driving times from the patient location to the thrombectomy centre were estimated, bypassing the primary hospital. This was done with custom written Python scripts (Plan D GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and Google Maps (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA). Both regions have multiple EMS ambulances at their disposal with the closest one available being ordered to the patient location. In contrast, our simulation intends to employ one MSU per region. Therefore, the additional driving time for the MSU had to be accounted for. Using the patient locations and driving times the optimal MSU location for each region was determined. This was also done by custom written Python scripts (Plan D GmbH) applying the Nelder–Mead algorithm, an established artificial intelligence (AI) method for this problem [18]. The illustration of hospital landscape, patient locations and optimized MSU location was created using Plotly (Montreal, Canada), which utilizes Mapbox (San Francisco, CA, USA) and draws data from OpenStreetMap (OpenStreetMap Foundation).

The time difference for each patient when treated by the hypothetical MSU pathway instead of the real‐world pathway was determined for relevant intermediate steps after the initial EMS call (arrival at patient, start of thrombolysis, departure to and arrival at thrombectomy centre, groin puncture). An assumed time of 29 min from MSU arrival to start of thrombolysis was derived from Sheikhi et al. [19]. To compare the two groups, the 50th percentile (median) as well as 25th and 75th percentiles (Q1; Q3) were calculated. Accordingly, the minutes saved to thrombolysis (if applicable) and to thrombectomy (groin puncture) were determined. Adjusting for age, sex and NIHSS, these saved minutes for all patients were translated into disability‐adjusted lifetime following Meretoja et al. [4, 5], resulting in a median (Q1; Q3) combined value for DALYs averted per patient by the MSU pathway for each partner region.

In order to estimate the overall effect of the MSU in each region, the number of thrombolysis and thrombectomy cases with prehospital MSU treatment had to be estimated. Both regions have about the same numbers of thrombolysis cases per year (∼130) and thrombectomy cases per year (∼70). As a point estimation it was assumed that the MSU can reach 40% of these cases (55 thrombolysis cases, 30 thrombectomy cases) [20]. However, since yearly numbers, spatial distribution and the validity of MSU dispatch can vary, a variation of thrombolysis cases (20–80/year) and thrombectomy cases (10–50/year) was modelled. For each combination of these numbers the number of averted DALYs was calculated by translating the sum of saved minutes to thrombectomy and saved minutes to thrombolysis using the published tables from Meretoja et al. [4, 5]. In addition, the costs that society would be willing to take into account for the calculated MSU effect were estimated. As currency, purchasing power parity dollars (PPP‐$) were used, a measure that takes into account the absolute purchasing power of the countries' currencies [21]. The corresponding amount of money was derived by multiplying the number of DALYs averted by the cost per DALY averted accepted in each country (Germany PPP‐$84.506 per DALY averted; Denmark PPP‐$94.390 per DALY averted; derived from 1.46 × GDP per capita from 2021, following Daroudi et al. [22] and published data from the Worldbank group [23]). For the German region, an additional point estimation was done that integrated the effect of two new thrombectomy centres planned in the future. These will be able to treat approximately half of the thrombectomy cases in the region (35 thrombectomy cases per year). With these numbers a rough estimation of net MSU costs accepted by society was put side by side for each partner region.

RESULTS

Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of the two cohorts. There is a numerical trend towards a younger age (72 years vs. 75 years) and a larger portion of male patients (54% vs. 41%) in the Danish cohort. NIHSS and time from last seen well are comparable between the two cohorts. A major difference is the large portion of patients with thrombolysis in the Danish cohort which is due to the different prehospital organization. Patients with a clear contraindication for thrombolysis are usually transferred directly to the thrombectomy centre in the Danish study region. Taking age, sex and admission NIHSS into account, the individual treatment effect in disability‐adjusted life days that can be expected for each minute of a faster thrombectomy or thrombolysis was taken from the supplementary tables of Meretoja et al. [4, 5].

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the two patient cohorts.

| Characteristic | German cohort (n = 80) | Danish cohort (n = 121) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (Q1; Q3) | 75 (66; 81) | 72 (60; 78) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 47 (59) | 56 (46) |

| Male | 33 (41) | 66 (54) |

| Admission status | ||

| NIHSS, median (Q1; Q3) | 14 (10; 17) | 15 (10; 19) |

| Time from last seen well (min), median (Q1; Q3) | 115 (63; 237) | 91 (63; 144) |

| Thrombolysis at primary hospital, n (%) | 42 (53) | 94 (77) |

| Type of stroke, n (%) | ||

| Anterior stroke (ICA, M1, M2) | 78 (98) | 108 (89) |

| Posterior stroke (BA) | 2 (3) | 14 (11) |

| Model‐based disability‐adjusted life days averted a , median (Q1; Q3) | ||

| Per saved minute to thrombectomy | 3.09 (2.39; 4.95) | 3.94 (2.63; 5.26) |

| Per saved minute to thrombolysis | 1.32 (1.08; 2.00) | 1.66 (1.09; 2.45) |

The patient pathways of the two regions are illustrated in Figure 1. The individual patient locations are plotted as blue points. For these patients, a complete dataset was available with documented timestamps for management during EMS, primary hospital, secondary transport and thrombectomy centre. One major difference between the German and the Danish hospital landscapes becomes obvious when considering the primary hospitals to which patients were first admitted (black plus symbols). Whilst the German region has seven different primary hospitals, the Danish region is centralized with one large primary hospital leading to longer driving times for the more peripherally localized stroke patients. Every patient in this map had an indication for thrombectomy and therefore received secondary transport from the primary hospital to the thrombectomy centre: University of Lübeck in the German region (triangle in left map) and University of Copenhagen in the Danish region (triangle in right map). This real‐world pathway was compared to a hypothetical MSU pathway. When analysing the patient's location and driving times to the thrombectomy centre, an optimal MSU location was determined with an AI approach using the Nelder–Mead algorithm (red ambulance symbol). For both regions the median driving time to a stroke patient of the cohort was 36 min from this optimized MSU location. This MSU location was used to describe a hypothetical MSU pathway. In this pathway, the MSU is driving to the patient, performing brain CT imaging on site, starting thrombolysis if applicable and driving directly to the thrombectomy centre, bypassing the primary hospital.

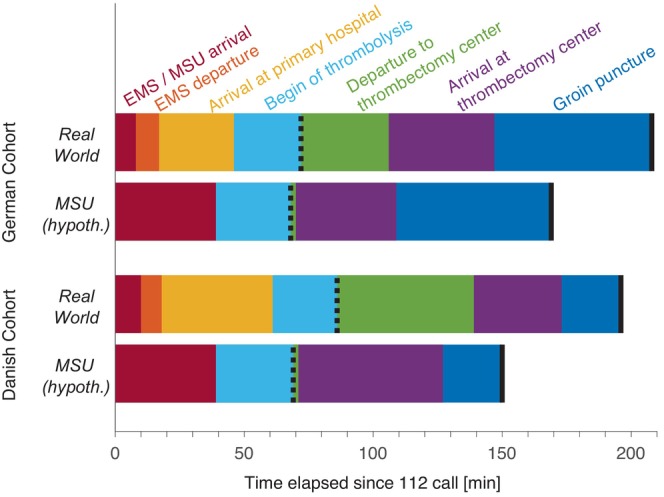

The timelines of both study cohorts are presented in Table 2 and graphically illustrated in Figure 3. The ‘Real world’ column contains the collected data whereas the ‘MSU (hypothetical)’ column simulates the MSU pathway for each patient. Interestingly, the elapsed time from the 112 call until EMS arrival at the patient (8 min vs. 10 min) and departure to the primary hospital (17 min vs. 18 min) are very similar in both regions, reflecting a well‐established EMS system in both rural regions. However, as expected, the arrival at the primary hospital tends to be earlier in the German region (46 min after 112 call) compared to the Danish region (61 min after 112 call). This reflects the many surrounding primary hospitals in the German region in contrast to one primary target hospital in the Danish region. The median door to needle time for patients treated with thrombolysis was 26 min in both regions. Since CT perfusion—if indicated—was routinely performed already at the primary hospital in the Danish region, the time from arrival to departure for the thrombectomy centre was longer than in the German region (78 min vs. 60 min). However, since the distance between primary hospital and thrombectomy centre in the Danish region was short, the cumulated difference of 33 min elapsed since the 112 call shrank to 25 min once the patient arrived at the thrombectomy centre. Since the primary hospitals in the German study region did not have an established penumbral imaging (e.g. CT perfusion imaging with mismatch of cerebral blood flow vs. cerebral blood volume), additional imaging had to be performed in the German thrombectomy centre in many cases. This explains the door to groin puncture of 61 min versus 23 min in the Danish thrombectomy centre which did not have to perform additional imaging. Due to the acceleration at this last step, the time elapsed from the 112 call to groin puncture was similar in the German and the Danish cohorts, considering the dispersion across the patients with median (Q1; Q3) time spans of 208 min (179; 242) versus 196 min (171; 230). The results of the MSU simulation are displayed in the column ‘MSU (hypothetical)’. In this model, the MSU functions as primary hospital with regard to thrombolysis and admission to the thrombectomy centre with no need of a secondary transport. The third and second table row from below contain the time differences between the MSU simulation and the real‐world situation for thrombolysis and thrombectomy. The median (Q1; Q3) of saved time was 7 min (−15; 31) in the German region versus 20 min (8; 30) in the Danish region for a thrombolysis and 32 min (15; 61) in the German region versus 43 min (25; 66) in the Danish region for a thrombectomy. Translating these time differences into outcome changes [4, 5] caused by the hypothetical MSU pathway yields 0.32 (0.07; 0.74) averted DALYs per patient in the German region and 0.49 (0.21; 0.83) averted DALYs per patient in the Danish region.

TABLE 2.

Timeline of hypothetical MSU.

| Minutes elapsed since 112 call, median (Q1; Q3) | German cohort (n = 80) | Danish cohort (n = 121) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real world | MSU (hypothetical) | Real world | MSU (hypothetical) | |

| EMS/MSU arrival | 8 (6; 12) | 39 (17; 58) a | 10 (6; 13) | 39 (24; 54) a |

| EMS departure | 17 (12; 26) b | 18 (14; 24) | ||

| Arrival at primary hospital | 46 (36; 54) | 61 (47; 72) | ||

| Start of thrombolysis (if applicable) | 72 (60; 89) | 68 (45; 87) c | 86 (73; 103) | 69 (53; 83) c |

| Departure to thrombectomy centre | 106 (92; 138) | 70 (49; 88) | 139 (121; 178) | 71 (55; 84) |

| Arrival at thrombectomy centre | 147 (129; 179) | 109 (92; 138) | 173 (152; 213) | 127 (99; 161) |

| Groin puncture | 208 (179; 242) | 169 (141; 205) | 196 (171; 230) | 150 (123; 179) |

| Saved minutes to thrombolysis | 7 (−15; 31) | 20 (8; 30) | ||

| Saved minutes to thrombectomy | 32 (15; 61) | 43 (25; 66) | ||

| Combined averted DALYs per patient | 0.32 (0.07; 0.74) d | 0.49 (0.21; 0.83) d | ||

Abbreviations: DALY, disability‐adjusted life year; EMS, emergency medical services; MSU, mobile stroke unit; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

MSU alarm to departure time was assumed to be 3 min.

Departure time in German cohort was deduced from Google Maps driving time.

Arrival at thrombolysis estimated 29 min from Sheikhi et al. [19].

FIGURE 3.

Timeline from the 112 call to groin puncture (see also Table 1).

Using the determined time saving for thrombolysis and thrombectomy, the annual effect of an MSU in each region was calculated assuming a range of cases reached by the MSU (Figure 4). Displayed as pseudo‐colour values are the number of DALYs averted per year for different numbers of thrombectomy cases and thrombolysis cases in the German region (a) and the Danish region (b). As expected from the time saving analysis, the overall effect is larger in the Danish region. The influence of thrombolysis cases is minor in Germany, reflecting the higher number of primary hospitals with thrombolysis capacity in the region. Isolines of equal net MSU budget justified by the DALYs averted are plotted above the pseudo‐colour values for incrementing steps from $0.5M to $2.5M. The matching net MSU budget was derived by multiplying the number of DALYs averted by the cost per DALY averted accepted in each country (Germany PPP‐$84.506 per DALY averted; Denmark PPP‐$94.390 per DALY averted; derived from 1.46 × GDP match per capita from 2021, following Daroudi et al. [22,23]). Both regions have about the same numbers of thrombolysis cases per year (∼130) and thrombectomy cases per year (∼70). Assuming that the MSU can reach 40% (52 thrombolysis cases, 28 thrombectomy cases) the number of DALYs averted per year is 9.4 in Germany translating into an annual net MSU budget justified by its effect of PPP‐$0.8M (black dot in (a)). With the same number of cases, the number of DALY averted per year amounts to 17.7 in Denmark, corresponding to an annual net MSU budget justified by its effect of PPP‐$1.7M (black dot in (b)). This numerical difference is even larger when a recent development in the German region is taken into account where two additional thrombectomy centres have been established, cutting in half the number of thrombectomy cases with the need for secondary transport. With the remaining number of 15 thrombectomy cases possibly reached by the MSU, the resulting annual effect is diminished to 5.1 DALY, an effect that would worth PPP‐$0.43M to German society, a budget that safely falls below a realistic net MSU budget. When considering the iso‐contour lines neighbouring the assumed numbers it becomes evident that, in contrast to the German region, the Danish region has a robust MSU effect even when assuming a lower number of cases. Taken together, whilst both regions cover a similar number of patients with a comparable population density and an equal MSU driving distance optimized from patient pathways, there is a considerable difference in the prognosticated MSU effect.

FIGURE 4.

Prognostication of annual DALYs averted by MSU implementation is colour‐coded for different combinations of thrombectomy cases (y‐axis) and thrombolysis cases (x‐axis) for the German region (a) and the Danish region (b). Note the overall smaller effect in the German region that is mainly dependent on thrombectomy cases, reflecting the minor time saving for thrombolysis cases. Plotted as dashed lines are isolines of averted DALYs multiplied by society‐adapted granted cost per DALYs averted (Germany PPP‐$84.506; Denmark PPP‐$94.390) in $0.5M steps. These lines reflect the maximal annual net cost of an MSU that would justify its effect in the eyes of society. Black circles denote the assumption that the MSU reaches 40% of 130 thrombolysis cases and 40% of 70 thrombectomy cases within each region. This allows for an annual MSU budget of $0.8M in the German region (black circle in (a)). After two new thrombectomy centres in the German region were established recently, the net annual MSU budget shrinks to below $0.5M (light grey circle in (a)) due to the low number of remaining thrombectomy cases. The net annual MSU budget justifying its benefits in the Danish region amounts to $1.7M (black circle in (b)), due to the large influence on both thrombolysis and thrombectomy cases, with an unchanged hospital landscape restricted to one primary hospital and one thrombectomy centre.

DISCUSSION

A descriptive two‐centre study was performed to analyse the potential effect of an MSU for neighbouring regions in southern Denmark and northern Germany. Using prehospital patient records and AI methods an optimal MSU location was found for each region with a median driving time of 36 min to the stroke patient. The hypothetical MSU pathway would result in a relevant time saving for both thrombolysis (German region 7 min, Danish region 20 min) and thrombectomy (German region 32 min, Danish region 43 min). Translated into the clinical effect of stroke therapies this would amount to 0.32 versus 0.49 averted DALYs per MSU‐treated patient in the German and Danish region, respectively. When assuming 28 thrombectomy cases and 52 thrombolysis cases treated by the MSU per year, the net yearly cost that society could be expected to accept would be $0.8M for the German region and $1.7M for the Danish region.

The technological challenges and medical safety issues involved in setting up an MSU have not been taken into account in this study. To date there are numerous variations of MSU vehicles of different sizes and equipment, and the service personnel also differ with some projects involving physicians on board whilst others rely on a complete telemedicine setup [24]. This is an important aspect when doing a complete cost‐effectiveness analysis. A major European milestone was the Berlin MSU Project, and the corresponding PHANTOM‐S study calculated annual MSU costs of about 1 million EUR (1.2 million PPP‐$). In a very recent MSU cost‐effectiveness study in Norway, annual costs of an MSU including operational costs, personnel costs and cost of medical devices were assumed to be 6.6 million Norwegian kroner [25], a sum that converts to PPP‐$615,000, therefore ranging at the lower end of the spectrum. When taking these numbers into the context of our study, it becomes apparent that relevant thresholds for a beneficial economical evaluation can be different in two comparable regions, depending on the hospital density and the general health system infrastructure. Whilst the German region would need a very inexpensive MSU project in order to be acceptable by the stakeholders, the financial scope for an MSU in the Danish region has larger margins, allowing lower numbers of patients to be reached and treated by an MSU. This reflects the different hospital density of the German healthcare system that exceeds the one of the Danish healthcare system by a factor of 2.5 [15]. A detailed cost‐effectiveness calculation could also take into account future developments in the hospital landscape that are currently planned by the German federal government [26] where MSUs may help to close gaps due to hospital closures. Although MSUs have been developed in high income countries our conclusion may also be relevant for middle income countries in Europe since they may help to optimize stroke care in areas with few thrombectomy centres.

The MSU concept also profits from technological advances in telemedicine that have been shown to be effective in the clinical outcome of neurological patients, especially in stroke medicine [27]. It has been shown that—with teleneurological support—also anaesthesiologists after specialized training can safely apply thrombolysis in an MSU setting with relevant acceleration and a higher portion of treatment within 1 h [28].

Our study has several limitations. It is a descriptive study which includes only patients with complete prehospital documentation. This may lead to a selection bias. The German region had a lower portion of complete documentation compared to the Danish region, reflecting the high level of Denmark regarding digitalization and e‐health technologies [29]. Considering the high number of patients with incomplete data in the German region, it can be argued that a bias could be introduced. The limited data available on patients with incomplete prehospital documentation were assessed. When looking at included patients versus excluded patients, a similar median age (75 years vs. 74 years), a higher portion of female patients (59% vs. 50%) and a slightly higher number of patients who received thrombolysis (56% vs. 53%) were found. Whilst this does not exclude a potential bias it suggests a certain epidemiological comparability between excluded and included patients. In general, it may be argued that our study included a sufficient number of patients in both partner regions to allow for a valid estimation.

Our study excluded patients who had a primary transport but not a secondary transport. There are two main reasons for this approach. For one, there was no access to patient data from the primary hospitals in the German study region. As shown in our article, there are seven primary hospitals all of which have special policies and modes of data acquisition. Therefore, the study cohort had to be confined to patients treated in the thrombectomy centre. In order to sustain comparability the same inclusion criteria were applied to the Danish study cohort. The second reason is our motivation and aim of the study. It was assumed that a drip‐and‐ship pathway can be taken to a completely new level of effectiveness if an MSU is involved. The main difference between the two study regions was the high number of primary hospitals in the German region. A close primary hospital with routine nearby EMS can outperform an MSU that has to travel larger distances when considering thrombolysis alone. However, if a secondary transport to a thrombectomy centre is necessary there is a large time saving effect. In the Danish region, time to thrombolysis is much more relevant since only one primary hospital is involved, with larger distances to many patients. However, even in this setting the MSU effect of time saving by bypassing the primary hospital with direct transport to the thrombectomy centre was considerable.

When rendering the optimal MSU location a straightforward approach of a direct MSU dispatch was chosen, leading to a relatively long median driving time of 36 min to the stroke patient. Installing an MSU station at a site chosen by optimal distances is often not realistic. An actually running MSU project has tested a rendezvous approach for more distant patients where EMS and MSU meet at an intermediate location en route to the target hospital [30]. In particular, in the Danish partner region with only one large primary hospital this would probably enhance the effect although the time of the transfer from EMS to MSU would have to be taken into account. However, in our model approach, an additional rendezvous approach would have required further assumptions that in turn would have introduced inaccuracies.

To estimate the driving time of the MSU to the patient and the thrombectomy centre Google Maps was used as source, as done previously in other studies on emergency health access [31]. It could be argued that driving times are not sufficiently precise and that EMS could be faster because of speed limit exemptions and special rights. It has been shown that transports within a city were 44 s faster when lights and siren were turned on [32]. However, depending on their size and safety regulations, some MSU vehicles cannot exceed the allowed speed limits to a relevant degree [33].

When looking at the resulting optimal MSU location, the German study cohort can introduce a systematic error when assuming that the completeness of prehospital data is heterogeneous across the study area. However, whilst the exact location of the excluded patients is not known (i.e., the location where EMS had the first encounter) the primary hospital location of all excluded patients is known. Whilst four of the three primary stroke centres only account for up to six patients each in both study populations, the three centres with the highest number of stroke patients referred to the thrombectomy centres have a similar distribution (study cohort 36, 17 and 18 patients; excluded patients 74, 73 and 53 patients). Therefore, instead of than a systematic selection bias, differences of population density within the study region are more likely to be responsible for the heterogeneous patient distribution.

Apart from its effect on accelerating the process from stroke onset to thrombolysis, neither the BEST‐MSU study nor the B_PROUD study showed a reduction in dispatch to thrombectomy times [11, 12]. However, a recent study has also shown that MSU service can shorten the interval from stroke onset to thrombectomy by several hours with resulting better stroke outcome [10]. This does not come as a surprise since thrombectomy acceleration generally has a larger effect on outcome than thrombolysis acceleration [4, 5].

Considering the number of thrombolysis and thrombectomy cases, 28 thrombectomy cases and 52 thrombolysis cases per year were estimated. This is well within the range of a recent meta‐analysis evaluating the thrombolysis and thrombectomy treatments of all published MSU studies, rendering 131 (95% confidence interval 79–183) thrombolysis treatments per year and 34 (95% confidence interval 17–50) thrombectomy cases per year [34]. Because of our hypothetical approach, there are a number of unknown errors possibly interfering with our assumptions, amongst others the actual stroke incidence and its regional heterogeneity. Because of these uncertainties calculations were performed with different thrombolysis and thrombectomy cases covering a range of possible combinations.

When assessing the clinical effect of the MSU project the time saved to thrombolysis and to thrombectomy was translated into averted DALYs following Meretoja et al. [4, 5]. With this approach a recent economic evaluation of the Melbourne Mobile Stroke Unit was followed that also used DALYs [35]. The Berlin B‐PROUD project used quality‐adjusted life years (QALYs) derived from prospective studies to perform a detailed cost‐effectiveness study [36]. Using DALYs instead of QALYs is not considered to introduce relevant differences for cost‐effectiveness analyses [37]. In our study DALYs were preferred, similar to other modelling studies [38, 39, 40], because this enabled us to use the differentiated tables from Meretoja et al. [4, 5]. Our approach of a linear translation from saved minutes to better outcome probably underestimates averted DALYs as it leaves the ‘golden hour of stroke’ concept unconsidered where a saved minute has more effect in the early period of stroke [41].

Our study focused on time differences and did not account for the higher proportion of patients receiving thrombolysis after MSU dispatch [14]. Whilst this effect further enhances the influence of an MSU it is difficult to quantify in our setting. For one, from our retrospectively acquired dataset it is challenging to estimate how many more patients could be treated with intravenous thrombolysis. In our cohort the specific reasons why intravenous thrombolysis was not applied are not known, and data are also lacking on patients who were not treated with an acute recanalization therapy at all. Therefore, this issue must remain unresolved in our approach but should be considered in future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

In a cross‐border endeavour, this study used pathways of patients with secondary transport for thrombectomy in two regions to calculate the effect of a future MSU implementation. Differences in hospital landscapes between Germany and Denmark became visible and show a large influence on the total outcome improvement in the catchment area. Considering the benefit–cost ratio stakeholders are more likely to invest in an MSU project in the Danish region than in the German region. However, future changes in the hospital landscape may change this consideration.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The project was funded in part by the European Union (Interreg5a). TFM is funded by the DFG (MU1311/20–1, 17–1).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

GR received speaker's honoraria and/or reimbursement for congress travelling and accommodation from Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Astra Zeneca, Ipsen, Boston Scientific, Novartis and Daiichi Sankyo.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and after positive approval of the local ethical committee.

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

As it relies on anonymized data from clinical routine, a consent was not required.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Bluhm S, Schramm P, Spreen‐Ledebur Y, et al. Potential effects of a mobile stroke unit on time to treatment and outcome in patients treated with thrombectomy or thrombolysis: A Danish–German cross‐border analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2024;31:e16298. doi: 10.1111/ene.16298

Troels Wienecke and Georg Royl contributed equally.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wafa HA, Wolfe CDA, Emmett E, Roth GA, Johnson CO, Wang Y. Burden of stroke in Europe: thirty‐year projections of incidence, prevalence, deaths, and disability‐adjusted life years. Stroke. 2020;51:2418‐2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Turc G, Bhogal P, Fischer U, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO)—European Society for Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) guidelines on mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischaemic stroke endorsed by Stroke Alliance for Europe (SAFE). Eur Stroke J. 2019;4:6‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berge E, Whiteley W, Audebert H, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2021;6:I‐LXII. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meretoja A, Keshtkaran M, Saver JL, et al. Stroke thrombolysis: save a minute, save a day. Stroke. 2014;45:1053‐1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meretoja A, Keshtkaran M, Tatlisumak T, Donnan GA, Churilov L. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke: save a minute—save a week. Neurology. 2017;88:2123‐2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walter S, Audebert HJ, Katsanos AH, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on mobile stroke units for prehospital stroke management. Eur Stroke J. 2022;7:XXVII‐XXLIX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fassbender K, Walter S, Liu Y, et al. ‘Mobile stroke unit’ for hyperacute stroke treatment. Stroke. 2003;34:e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walter S, Kostopoulos P, Haass A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with stroke in a mobile stroke unit versus in hospital: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:397‐404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ebinger M, Winter B, Wendt M, et al. Effect of the use of ambulance‐based thrombolysis on time to thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1622‐1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Al Saiegh F, Velagapudi L, Khanna O, et al. Improved functional outcomes of stroke patients undergoing mechanical thrombectomy after arriving via a mobile stroke unit. World Neurosurg. 2022;166:e546‐e550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ebinger M, Siegerink B, Kunz A, et al. Association between dispatch of mobile stroke units and functional outcomes among patients with acute ischemic stroke in Berlin. JAMA. 2021;325:454‐466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grotta JC, Yamal J‐M, Parker SA, et al. Prospective, multicenter, controlled trial of mobile stroke units. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:971‐981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rohmann JL, Piccininni M, Ebinger M, et al. Effect of mobile stroke unit dispatch in all patients with acute stroke or TIA. Ann Neurol. 2023;93:50‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Turc G, Hadziahmetovic M, Walter S, et al. Comparison of mobile stroke unit with usual care for acute ischemic stroke management: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79:281‐290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Amelung V, Klapper B, Knieps F. Gesundh‐ Sozialpolitik GS. 2020;74. 10.5771/1611-5821-2020-4-5 [DOI]

- 16. Ostholstein K. Wikipedia. 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://de.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kreis_Ostholstein&oldid=228620989

- 17. Region Zealand . Wikipedia. 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Region_Zealand&oldid=1114234690

- 18. Nelder JA, Mead R. A simplex method for function minimization. Comput J. 1965;7:308‐313. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sheikhi LE, Mullaguri N, Nocero J, et al. Abstract TP285: improving mobile stroke unit intravenous thrombolysis times through parallel processing. Stroke. 2018;49:ATP285. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wenstrup J, Hestoy BH, Sagar MV, et al. Emergency medical services dispatcher recognition of stroke: a systematic review. Eur Stroke J. 2024;23969873231223339. doi: 10.1177/23969873231223339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buja A, Rebba V, Montecchio L, et al. The cost of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Value Health. 2024;27(4):527‐541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Daroudi R, Akbari Sari A, Nahvijou A, Faramarzi A. Cost per DALY averted in low, middle‐ and high‐income countries: evidence from the Global Burden of Disease Study to estimate the cost‐effectiveness thresholds. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2021;19:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. GDP per capita, PPP (current international $)—Denmark, Germany | Data. Accessed January 24, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?locations=DK‐DE

- 24. Fassbender K, Merzou F, Lesmeister M, et al. Impact of mobile stroke units. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92:815‐822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lund UH, Stoinska‐Schneider A, Larsen K, Bache KG, Robberstad B. Cost‐effectiveness of mobile stroke unit care in Norway. Stroke. 2022;53:3173‐3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vierte_Stellungnahme_Regierungskommission_Notfall_ILS_und_INZ.pdf. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/K/Krankenhausreform/Vierte_Stellungnahme_Regierungskommission_Notfall_ILS_und_INZ.pdf

- 27. León‐Salas B, González‐Hernández Y, Infante‐Ventura D, et al. Telemedicine for neurological diseases: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2023;30:241‐254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Larsen K, Jæger HS, Tveit LH, et al. Ultraearly thrombolysis by an anesthesiologist in a mobile stroke unit: a prospective, controlled intervention study. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:2488‐2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wadmann S, Hartlev M, Hoeyer K. The life and death of confidentiality: a historical analysis of the flows of patient information. BioSocieties. 2023;18:282‐307. doi: 10.1057/s41292-021-00269-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parker SA, Kus T, Bowry R, et al. Enhanced dispatch and rendezvous doubles the catchment area and number of patients treated on a mobile stroke unit. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29:104894. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Banke‐Thomas A, Avoka CK‐O, Gwacham‐Anisiobi U, et al. Travel of pregnant women in emergency situations to hospital and maternal mortality in Lagos, Nigeria: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:008604. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hunt RC, Brown LH, Cabinum ES, et al. Is ambulance transport time with lights and siren faster than that without? Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:507‐511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ebinger M, Rozanski M, Waldschmidt C, et al. PHANTOM‐S: the prehospital acute neurological therapy and optimization of medical care in stroke patients study. Int J Stroke. 2012;7:348‐353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ellens NR, Schartz D, Rahmani R, et al. Mobile stroke unit operational metrics: institutional experience, systematic review and meta‐analysis. Front Neurol. 2022;13:868051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim J, Easton D, Zhao H, et al. Economic evaluation of the Melbourne mobile stroke unit. Int J Stroke. 2021;16:466‐475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oliveira Gonçalves AS, Rohmann JL, Piccininni M, et al. Economic evaluation of a mobile stroke unit service in Germany. Ann Neurol. 2023;93:942‐951. doi: 10.1002/ana.26602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Feng X, Kim DD, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ, Ollendorf DA. Using QALYs versus DALYs to measure cost‐effectiveness: how much does it matter? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020;36:96‐103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schlemm L, Endres M, Scheitz JF, Ernst M, Nolte CH, Schlemm E. Comparative evaluation of 10 prehospital triage strategy paradigms for patients with suspected acute ischemic stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schlemm L, Endres M, Nolte CH. Bypassing the closest stroke center for thrombectomy candidates: what additional delay to thrombolysis is acceptable? Stroke. 2020;51:867‐875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sriudomporn S, Rachmad Nugraha R, Ahuja N, Drabo E. The cost effectiveness of mobile stroke unit in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2020;55:47. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kunz A, Nolte CH, Erdur H, et al. Effects of ultraearly intravenous thrombolysis on outcomes in ischemic stroke: the STEMO (stroke emergency mobile) group. Circulation. 2017;135:1765‐1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.