Abstract

Background:

Family is a crucial social institution in end-of-life care. Family caregivers are encouraged to take on more responsibility at different times during the illness, providing personal and medical care. Unpaid work can be overburdening, with women often spending more time in care work than men.

Objectives:

This study explored multiple views on the family’s role in end-of-life care from a critical perspective and a relational autonomy lens, considering gender in a socio-cultural context and applying a relational autonomy framework. It explored patients, relatives and healthcare providers’ points of view.

Design:

This qualitative study was part of the iLIVE project, involving patients with incurable diseases, their relatives and health carers from hospital and non-hospital sites.

Methods:

Individual interviews of at least five patients, five relatives and five healthcare providers in each of the 10 participating countries using a semi-structured interview guide based on Giger–Davidhizar–Haff’s model for cultural assessment in end-of-life care. Thematic analysis was performed initially within each country and across the complete dataset. Data sources, including researchers’ field notes, were translated into English for international collaborative analysis.

Results:

We conducted 158 interviews (57 patients, 48 relatives and 53 healthcare providers). After collaborative analysis, five themes were identified across the countries: family as a finite care resource, families’ active role in decision-making, open communication with the family, care burden and socio-cultural mandates. Families were crucial for providing informal care during severe illness, often acting as the only resource. Patients acknowledged the strain on carers, leading to a conceptual model highlighting socio-cultural influences, relational autonomy, care burden and feminisation of care.

Conclusion:

Society, health teams and family systems still need to better support the role of family caregivers described across countries. The model implies that family roles in end-of-life care balance relational autonomy with socio-cultural values. Real-world end-of-life scenarios do not occur in a wholly individualistic, closed-off atmosphere but in an interpersonal setting. Gender is often prominent, but normative ideas influence the decisions and actions of all involved.

Keywords: care burden, end-of-life care, family caregiving, palliative care, qualitative research

Introduction

Family is a culturally universal social institution. Its definition is debated and evolves to a varying degree across cultures, countries and religions, but the family is mainly seen as an interconnected unit of supportive and interactive people. 1 Family can include immediate blood relatives, people connected by emotional bonds, close neighbours and even companion animals. 2 Family carers are encouraged to take on more responsibility in caring for dying family members, such as providing personal and medical care. 3 Families can either endorse or disagree with care efforts in palliative care, making them central to patient care. Families are also seen as recipients of care within palliative care, although in their double role as carers and cared for, the latter may be given less priority. 4

As societies age, there will be a growing demand for palliative care in old age and an ageing population of family carers. In this context, family caregiving is the care given at home by an informal carer – a family member, friend or fictive kin – who gives some care to an older adult with whom they have a relationship. 5 Learning how to offer such care with little expertise can be difficult, causing anxiety and tension. It can exacerbate an already tense, stressful and insecure setting, potentially leading to bad experiences or consequences. 3 Reports show that carers not supported by specialists frequently lose control of the situation, causing negative experiences. 6

In this setting, where families are involved in care and decision-making, an approach to end-of-life care that emphasises solely autonomy principles without considering the relational context does not fully capture the complexity of patients’ preferences and experiences. 7 Relational autonomy is often interpreted as a reaction to individualistic accounts derived from various philosophical sources. In end-of-life care, a relational account of autonomy has been advocated as a more appropriate approach. Relational autonomy has been proposed as a foundational concept for palliative care, shared decision-making and advance care planning. A relational understanding of autonomy considers the individual’s social reality in decisions. The analysis of end-of-life practices places the patient at the centre, interacting directly with healthcare providers and the environment (i.e. family, friends and communities). 8

Moreover, a significant interplay exists between healthcare providers and the relational environment, eventually affecting the patient. These interactions do not occur in a void but in a particular socio-cultural context that shapes them. Relationships, expectations and constraints are all conditioned by the social and cultural framework in which they occur. 9

A recent scoping review has shown that taking on the responsibilities of a family carer is not stress-free and might lead to a ‘burden’ from the accepted duty. 10 Usually, women’s quality of life is negatively affected, and they become almost ‘invisible’ to the health care system. 10

Family caregivers often assume different responsibilities and roles without preparation or with insufficient knowledge of the roles or tasks. Reigada et al. 6 associated the family caregiver’s role with decision-making, describing it as the ‘Decider at the end-of-life’. The role often leads to a sense of obligation and anguish, especially regarding medical decisions. Female carers are more likely to experience burnout and receive less help from other family members. Researchers argue that this feminisation of the role should be characterised as a socio-cultural process of patriarchy, inequitable power distribution, social disparity and various types of inequity beyond sex.5,11,12 In this context, gender plays an important role, understood as ‘the social, cultural and symbolic construction of femininity and masculinity in any given society’. 5

Healthcare staff and family members are often closely involved in providing care for the patients and are all individuals who can influence and be influenced by the patient’s decisions. 7 The family participates in communications and decision-making, manages health resources and provides emotional support. 11 However, family care is unpaid work, often overburdened, needs to be more evenly distributed and has different stakeholders responsible for its provision. 13 Paid and unpaid care work is at the heart of humanity and our societies. Women typically spend disproportionately more time in unpaid care work than men, irrespective of location, class and culture. 14 Abel and Kellehear’s ‘95% rule’ suggests that very sick and dying individuals receive care from healthcare services less than 5% of the time in their last year of life, with the remaining 95% relying on family, friends or non-health professionals. 15 However, women’s caregiving largely remains invisible and underappreciated. 16

Society, in general, also plays an essential role in developing values such as dignity, responsibility and respect for the vulnerable. Layered support from social policies and organisational culture is needed to enable changes in everyday professional attitudes and practices. 16 The Lancet Commission’s report on the value of death argues for a better system of death and dying where care networks lead to support for people dying, caring for and grieving. 17

Socio-cultural mandates are societal values and meanings assigned to specific roles and practices within a community. These are determined by socio-historical and cultural factors and are internalised and naturalised. Two significant stereotypes in patient care are familiarisation and feminisation, where family members, healthcare providers and women are expected to take care of the patient, ensuring their participation. 18

We are supposed to understand palliative care as ‘an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families’ at a time of intense need. In that case, gender must be included as a category of analysis when conducting further research in this area. Furthermore, many governments, healthcare systems and social institutions only provide limited assistance to family carers, exacerbating the distress and anxiety imposed by such situations. 6 It is crucial to develop sensitive research skills and socio-cultural knowledge in end-of-life care to understand better how socio-cultural issues affect illness experience and care. 19

This study aimed to explore and understand multiple views of the family’s role in end-of-life care from a critical perspective, considering gender in a socio-cultural context and applying a relational autonomy framework. 8 We explored patients’, relatives’ and healthcare providers’ points of view.

Methods

Study design

This analysis is part of the iLIVE project (funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Programme), which aimed to describe experiences at the end of life for patients with advanced chronic, life-threatening illnesses and their families in Argentina, Germany, Iceland, The Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK. In addition, we aimed to build a better understanding of culture-related issues concerning family support at the end of life in each iLIVE participating country. This qualitative study was embedded in the iLIVE cohort study. Please refer to the protocol article related to this study for further details about the study’s setup. 20

Study population

Recruited patients with incurable diseases receiving palliative care and their relatives and health carers were invited for an in-depth interview. In each of the 10 participating countries, at least 5 patients, 5 relatives and 5 healthcare providers were interviewed. Eligible patients were identified using a modified version of the Gold Standards Framework Proactive Identification Guidance with the surprise question (SQ) 21 and the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool 22 for identifying general and disease-specific inclusion criteria. The SQ enquires about the physician’s surprise if a patient dies within 12 months, which was adjusted to 6 months in our study.

Patients were recruited in hospital departments (general wards or specialist palliative care units) and non-hospital sites (hospices, home-based care, nursing homes, long-term care clinics). We used a purposeful convenience sampling technique involving diverse healthcare professionals and patients of varying ages, diseases and genders, considering the complexity and diversity of end-of-life experiences. Physicians at the participating sites assessed patients’ eligibility and recruitment. Patients under 18 years old, unaware of the unlikelihood of recovery, or unable to provide informed consent were excluded from participation. All participants in the study were provided with understandable oral and written information on the study in the country’s language and had written informed consent.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted face-to-face, by telephone or via videoconferencing, depending on the setting facilities and participants’ preferences amid the pandemic. They were semi-structured using a topic guide based on Giger–Davidhizar–Haff’s model for cultural assessment in end-of-life care, 23 the affective, behavioural, cognitive and dynamics of difference (ABCD) model 24 and perception of disease questions. 25 The model postulates that each individual is culturally unique and should be assessed based on six cultural phenomena: (a) communication, (b) space, (c) social organisation, (d) time, (e) environmental control and (f) biological variations. For each group, patients, family members and healthcare providers, a topic guide was developed based on the one for patients (Supplemental Appendix 1). The guide explored the following domains: (a) perception of illness; (b) space – family; (c) communication; (d) environmental control, (e) social organisation – spiritual comfort and transcendental belief; (f) time orientation and (g) emotional and physical pain and suffering.

We prepared extensively to ensure sensitivity to different views in the interviews and multi-perspective analysis across countries. We produced a comprehensive work plan, protocol, interview manual and online training for interviewers, discussing methodological difficulties. Interviews were collected in parallel waves across nations, with monthly comparisons to stay updated on discoveries. The transcripts in each country’s language were analysed at three levels: within each country, within three sub-groups and across all countries. Similarities in mother tongue (Scandinavian, English and Spanish speakers) were used to create these sub-groups. Participants were recruited to the study between February 2020 and October 2021.

Data analysis

A reflexive thematic approach was used to analyse the qualitative interview data. Braun and Clarke’s six-step process 26 was used to organise the data into meaningful themes. This consisted of (1) familiarisation with the interview transcripts, (2) initial coding, (3) identification of themes, (4) review of themes, (5) definition of themes and (6) writing up.

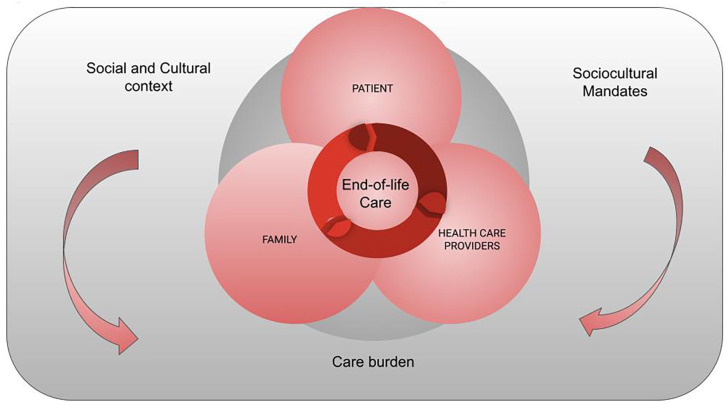

Each country’s research team contributed to first-phase analyses, including coding and identifying possible themes from all data sources and researchers’ field notes. Researchers translated themes and codes into English. Two researchers (VAT and VIV) designed the contextual framework for qualitative analysis (Figure 1). We critically reflected on how relational autonomy can serve as a touchstone for dealing with end-of-life complexities, integrating different socio-cultural contexts. 7 Humans are not isolated; they are part of a complex network of relationships with other humans and a specific cultural setting.

Figure 1.

The contextual framework for qualitative analysis.

Researchers from Argentina, Spain and Germany studied local interviews and patients’ words to identify dying and end-of-life care themes. They created a shared codebook with high-level themes and sub-themes distributed to all participating countries. The thematic analysis uncovered patterns and processes, revealing how people perceive, assess and reflect on experiences, concerns, expectations and preferences. The multi-perspective analysis involved iterative activities at various levels, including within each country, within sub-groups and between all countries. Regular meetings and workshops were organised for inductive analysis. The study focused on family domains, coding reported needs, preferences and values, and exploring links between family support, communication and decision-making. At least two researchers from each country coded the data. The depth of engagement was crucial for quality coding. We followed the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research: a 32-item interview checklist 27 (Supplemental Appendix 2).

Results

We conducted 158 in-depth interviews (57 with patients, 48 with relatives and 53 with healthcare providers). Table 1 describes the socio-demographic characteristics of the population and the bonds with the person cared for. Interviews with patients and family members lasted 60–140 min, while with healthcare providers, they lasted approximately 30 min.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of 158 interview participants.

| Country | Patients | Relatives | Healthcare providers | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean age | Gender female/male | Living with the family | n | Mean age | Gender female/male | Bond: children/partner/other | Living with the patient | n | Mean age | Gender female/male | Profession: doctor/nurse/other | Setting hospital/hospice/PC homecare | |

| AR | 6 | 67 | 3/3 | 4 | 6 | 54.3 | 3/3 | 2/2/2 | 5 | 6 | 54 | 4/2 | 4/1/1 | 3/1/2 |

| GER | 10 | 67.5 | 6/4 | 3 | 5 | 56.6 | 3/2 | 2/2/1 | 2 | 6 | 43 | 3/3 | 1/3/2 | 6/0/0 |

| IS | 5 | 74 | 3/2 | 2 | 5 | 61 | 2/2 | 2/1/0 | 2 | 5 | 57.8 | 5/0 | 1/3/1 | 5/0/0 |

| NO | 5 | 60.6 | 2/3 | 4 | 5 | 49.8 | 4/1 | 3/2/0 | 5 | 5 | 43.8 | 3/2 | 1/4/0 | 5/0/0 |

| SP | 5 | 72.8 | 3/2 | 3 | 5 | 45.6 | 3/2 | 2/2/1 | 2 | 5 | 43.8 | 3/2 | 3/2/0 | 0/5/0 |

| NL | 5 | 76 | 2/3 | 2 | 5 | 59.6 | 4/1 | 3/1/1 | 4 | 5 | 57 | 2/* | 2/3/0 | 3/2/0 |

| UK | 5 | 71.8 | 3/2 | 4 | 5 | 50 | 3/2 | 1/*/* | 1 | 5 | * | 5/0 | 2/3/0 | 3/2/0 |

| SWI | 6 | 60 | 3/3 | 4 | 6 | 44.4 | 5/1 | 4/2/0 | 5 | 5 | 48.2 | 3/2 | 1/2/2 | 5/0/0 |

| SI | 5 | 74.4 | 2/3 | 4 | 5 | 62.8 | 4/1 | 3/2/0 | 3 | 5 | 54.25 | 5/0 | 1/3/1 | 4/*/* |

| SWE | 5 | 72.4 | 2/3 | 3 | 5 | 61.1 | 5/1 | 3/3/0 | 3 | 6 | 51.8 | 4/1 | 1/4/0 | 0/5/0 |

| Total | 57 | 70.8 | 28/29 | 34 | 52 | 55.5 | 35/16 | 24/18/4 | 29 | 52 | 52.3 | 28/11 | 17/24/6 | 35/10/2 |

Missing data.

AR, Argentina; GER, Germany; IS, Iceland; NO, Norway; SP, Spain: NL, Netherlands; UK, United Kingdom; SWI, Switzerland; SI, Slovenia; SWE, Sweden.

These results integrate the perspectives of patients, families and professionals. Gender is considered, and age is given as under or over 50 years in quotes to protect anonymity. The mean age of the patients was 70.8 years, and of the caregivers, 55.5 years, mostly women (67%). The collaborative analysis will result in five themes for their experiences with end-of-life care: (1) Family as a finite care resource; (2) families in decision-making; (3) communication with the family; (4) care burden and (5) Socio-cultural mandates.

Family as a finite care resource: ‘I have to be the one who does everything’

Being faced with death, patients valued the accompaniment of the family. Family members started to do other and more things than before, and bonds were restored for most, allowing many to become closer.

My family plays a significant role because they accompany me throughout the whole process, and they accompany me in what I need most. So, the role played by the family is crucial. (AR_M_age under 50_ Hospital inpatient)

Family members experienced this increased intensity likewise and often reported a challenge to continue their everyday lives, as their involvement in the care of their dying relative took over many parts of their lives.

He is totally dependent on me regardless of where he is. At home, he needs me around for practical reasons all the time. At the hospital, he needs me to convey new information to his family, communicate with different public offices and institutions, and with the home care nurses because he does not have the strength to do this himself anymore. So, his disease affects all parts of my life. (NO_F_age under 50_partner)

Family members were the main source of care, and they described changes in several life domains. They noted the difficulty of these changes and expressed concerns about growing dependency. Family members, mostly women of all ages, were involved in the organisation of care, practical issues, support, decision-making and communication within their families and with professionals.

I stopped seeing him as the protective husband, the man of the house; that change of roles was a job of saying, well, now I have to be the one who generates the money, who generates the maintenance, the cooking, who does everything. (AR_F_age over 50_partner)

Health professionals identified the family as the only finite resource of care and reported challenges with missing and complex relationships, which complicated the provision of care.

Thus, it is really challenging when the patient has no close relatives or if they are in constant conflict, which is very often the case. Above all, difficult family relationships are the biggest problem. (SI_F_age over 50_ nurse_hospital)

Families’ active role in end-of-life decision-making: ‘My wife knows more than I do’

Patients’ reflections showed that they relied on family members for decision-making concerning care and more.

My wife knows more than I do. (. . .) We have discussed things, and they know what I want. (NL_M_ age over 50_ home)

I have told my partner where I want to be buried, and I have made a will, and I will write the white archive here, write about it. (SWE_F_age over 50_home)

Family members became the voice of the patients. They were the agents that could include the dying person’s experience in decision-making.

I will be in everything, and I like to be involved in those decisions, but it was clear to me that he had to make them. (SP_ M_age under 50_ Ex-partner)

It is all very well to have a professional perspective that can provide information. But there is an experience that is yours, that is his (patient’s), that is also part of the decision, and that is not so simple. (AR_F_age over 50_partner)

This included decisions that sometimes led to being less close to each other to relieve the pressure on the family caregivers.

To be honest, it was a relief for them when I went into a nursing home. (. . .) Now, we have friendly relationships. If I were at home, we wouldn’t have. One seems to get tired of it. (SI_F_age over 50_nursing home)

Although challenging, the decisions made reassured and empowered patients and families. Some carers wanted decisions in writing.

I wanted to have it in writing because I was under pressure from the doctor (. . .) I remember he wrote me a NO; it was hard for her. I remember putting a sign to cross out the wrong thing, but the doctor told me he is not fully aware of what it is like to die by drowning; it is not valid. Unless he makes an advance directive at the onset of the disease. (AR_F_age over 50_partner)

Healthcare providers expressed that they included families in decisions as much as possible. However, they also recognised situations in which they ensured that patients would have the last word unless they were too ill to make decisions any longer.

A negative situation is especially when you can’t reach an agreement, when the relatives definitely don’t think their partner should be allowed to die, or should get another chemotherapy (. . .) and the patient stands in between and doesn’t know what to decide. In this situation, as long as the patient is capable of judgment, he ultimately decides. The question is whether he can assert himself against his relatives. (. . .) So then we go one step further to find out what the patient’s wish is, and then take that back to the relatives to tell them that’s what the patient has decided. (SWI, F, age over 50, social worker at Hospital Palliative Care Unit)

Open communication with the family: ‘Anticipating what can happen and how it will happen’

Regarding communication with the family in our study, patients preferred to protect their families to avoid suffering.

(. . .) I needed an outlet for me to be able to process what wasn’t going to hurt the people I love. (UK_F_age over 50_home)

However, they stressed the need for honest communication and to be able to deal with pending conversations. Patients described the wish for honest communication within the family.

The feeling is that there are talks that I have to end, that I have not ended. About her future, my son’s future, the fact that I’m not going to be there, how daily life continues, she has to go back to work. We should talk about all these things, which are everyday things. (AR_M_age over 50_Private Hospice)

Family members also emphasised the need for honest information to be able to help and receive support from others.

We are open about the situation with our families and close friends on both sides. Also, with healthcare providers. With everybody who cares, really. It is very nice to know that they care and would like to help. If they are not informed, how could they help us? (NO_F_age under 50_partner)

Sometimes, women assuming caregiving became isolated, preferred not to talk about it or felt mentally overwhelmed.

It is difficult to live normally when he is in and out of the hospital all the time because he is so ill. This situation is mentally disturbing for me, and I do not function normally. (NO_F_age over 50_daughter)

The professionals considered communication with the family essential, pointing out the importance of anticipating what could happen and how. The family was also considered an essential source of information.

We start the conversation, but what we do is facilitate and provide the space for the family to start giving us the information. (SP_M_age over 50_PC nurse hospice)

Just the fact that families could communicate with a professional when needed seemed to be reassuring.

I think it is fundamental that (the patient-family) has your mobile phone number, but I don’t know if it’s right or wrong (. . .) I think the family is calm because they have it (. . .) they don’t bother me, they call me, they don’t harass me. (AR_F_age under 50_ physician Private Hospice)

Care burden: ‘Some days, you reach your limits’

We found that patients expressed concern about family efforts and how concerns, needs and support within the family system could become entangled. At times, families and patients did not know how to communicate their needs and worries about each other, which became a burden on their own.

He (adult son) is hurting . . . He has always been very close to me. I feel that he has closed it inside. Sometimes, he comes and sits with me and tries to talk to me, but he can’t say what he wants to talk about, and then he becomes angry, hurt, and so frustrated . . . (IS_F_age over 50)

He’s my biggest worry, I would have thought, and he’s my biggest support system, so it’s a worry that he’s my biggest worry. (UK_F_age over 50_home)

Sometimes, they felt the last man standing. Relatives stressed loneliness in the task and the fear of also becoming ill. Physical and mental tiredness associated with dependency made relatives feel exhausted.

So I’m the one who’s here 24 hours a day. And I mean, if I hadn’t been here, (name) wouldn’t have gotten any help, (. . .) because he didn’t have this alarm on when he went to the bathroom. (. . .) And then the question is, if something happens to me, what happens then? (SWE_F_age over 50_partner)

His dependency on me is exhausting in the long run. To keep my head above water in the future, I would need some more support and practical help in our home. (NO_F_age under 50_partner)

They also worried about skills in the last phase and difficulties discussing death and dying with the patients.

Women expressed their surprise at the end of the day by the work done but recognised their emotional vulnerability.

Because on some days you really reach your limits (.) [I: Yes] and (–) your own psyche doesn’t always put up with everything. (GER_F_age under 50_daughter)

Professionals tried to assess what was best for the whole system and most interpreted stressed communication from a compassionate point of view.

You try to match what you have with what the family gives you. In another case with the same patient, the family tells you they can’t go any further and that your only resource is institutionalising the patient. (SP_M_age under 50_PC physician Hospice)

There is always the situation that you (exhales loudly) learn from nurses or third parties, the colleagues of other departments (inhales loudly) about the relatives, that they are extremely aggressive, that they are very, very demanding, that they want everything, everything should be done. (GE_M_age under 50_intensive care physician, hospital)

Socio-cultural mandates: Who cares? ‘Someone must do it’

We found that patients felt ambiguity regarding the family caregiving they received.

Did you talk to her (wife) about it? Yes, little by little, but the reaction ‘I do it because I have to do it (. . .) a huge job, (. . .) and the answers are more or less ‘but someone must do it’, that kills you’. (AR_M_age over 50_Private Hospice)

Regarding patient support, the family played a very important role throughout the whole process. Relatives assumed what they had to deal with and felt responsible for it. It involved broad networks of support.

We have been separated for the last two years. Before that, I lived with him. I left for two years, and now, with the illness, I am back with him. (SP_ M_age under 50_ ex-partner)

The caring tasks were considered mandatory for some relatives and a priority for patients. However, patients felt guilty because they did not want to drag anyone else into it. Relatives felt responsible for this care and assumed that ‘they have to deal with it’. This responsibility was more ingrained in women who highlighted their role as ‘natural carers’ and who saw themselves and were seen as wanting to assume all caring tasks.

Well, I think it, for most women, they’re always looking after people, aren’t they? Families and I do things on my own, and I’ve had a good life; I’m not moaning! But, I do think that women are natural carers and don’t want to give too much trouble to anybody else, basically. (UK_F_age over 50_hospital)

Unfortunately, the one who will bear the burden of everything will be my mother because he will want my mother to do everything (. . .) But I don’t know if my mother will allow herself to say, ‘No, I can’t’. (AR_F_age under 50_daughter)

Decisions about reducing the working percentage or quitting their job were also made for those in the workforce. Women more often made these decisions.

I stopped working because it wasn’t right for me; I know that my father’s time is very limited (. . .) So, I just decided by myself that I still have a lifetime to work, while my time with him is limited (. . .) and with the additional burden that I am experiencing currently with my father, I needed to find a way that works for me. (SWI, F_age under 50_ daughter)

Female relatives sometimes did not think much about themselves; they prioritised everyone and everything else.

I take care of everything and clean her home and such . . . I don’t think much about myself; I think foremost about others. (IS_F_age over 50_daughter)

I don’t like to be involved in these decisions, but my sister is the youngest, and I feel responsible for it. It’s a question of personality, I consider that I take into account the smallest detail. Some people are good at it, and some people are not. (SP_F_age under 50_daughter)

Healthcare providers worried about some palliative care teams that associated the concept of ‘Good families’ with those that undertake many caring tasks and if, in particular, there were women in those families who would take on the carer roles without question. Argentinian professionals highlighted this concept.

- Who should be involved in caring for patients in the last weeks of life? – The family. (AR_F_age under 50_nurse_Private Home PC)

Even worse, there are still teams that believe a family is a good family if it cares and has a woman who looks after the family. (AR_F_age over 50_Social Worker_Home PC)

In addition, healthcare providers had the perception that families had an ‘It’s going to be all right’ attitude, denying the situation and expecting teams to keep doing everything. This sometimes challenges and confuses healthcare providers.

There are family members who have some difficulty in coping with the situation, so their defence mechanism is to doubt what you are doing, and in the end, you doubt what you are doing. (SP_F_age under 50_PC physician)

I would like not to provide invasive measures that may not add up. Still, I often think that the family’s perception is very difficult (. . .) because it isn’t a paternalistic model in which you make all the decisions (. . .); they think that doing nothing is killing the patient, and that feeling and that shock is what makes it more difficult for me. (AR_F_age under 50_nurse_Private Home PC)

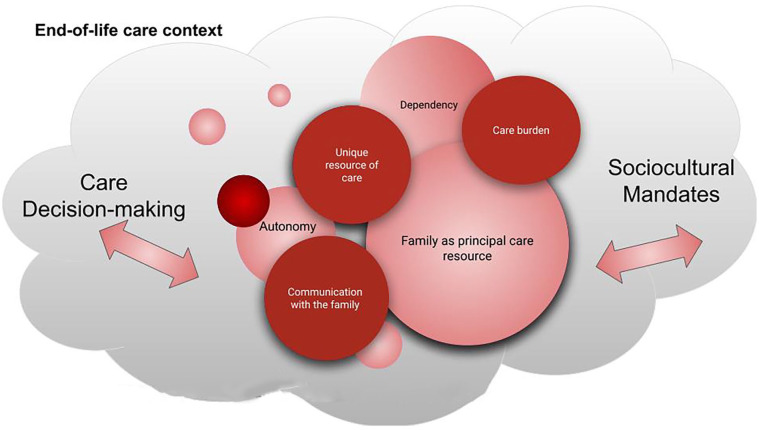

An explanatory model regarding culture, family and decision-making

Based on our findings, we developed an exploratory model that describes how, in the end-of-life context, the role of the family in decision-making and end-of-life care is linked to cultural mandates in a constant tension of forces, depending on the perspective of the patient, the relatives or the healthcare providers (Figure 2). Dependency was added after analysis as it was found relevant to care burden and relational autonomy. It helped to come to a better understanding of the care burden and the feminisation of care.

Figure 2.

Exploratory and interpretative model regarding socio-cultural context, family care and care decision-making.

This approach, therefore, provides a pathway for professional engagement with the patient and family carers, taking into account socio-cultural mandates and autonomy in an individualised social environment. These interrelated domains reflect what would need to be addressed to meet the core goal of palliative care: to care for the patient and family as a unit of care. In this way, all those involved (patients, carers and healthcare providers) can feel recognised as elements of a beneficial partnership.

Discussion

We examined the family’s role in end-of-life care from the perspectives of very ill patients, most of whom were over 60 years old, family members, primarily women and healthcare providers in 10 countries. We proposed a model that considers socio-cultural context, relational autonomy frameworks, care burden and feminisation of care to understand the experience of informal caregiving. The study contributes to understanding how patients’ end-of-life care is contextualised. Participants in the iLIVE project were a culturally diverse group from one South American and nine European countries. Culture shapes thinking, actions and being, resulting in patterned expressions passed down from generation to generation. 23 The study highlights the concept of relational autonomy in different countries, emphasising the importance of honest communication and patient consent. The narratives also reveal feelings of guilt due to dependency overload.

Caring was naturalised as a natural role for families, especially for women. The tension between ‘someone must do it’ and ‘no one forced me to care for him’ highlighted the obligation and duty internalised beyond age. European reports on informal care reveal that informal care is prevalent in Spain, and formal services are underdeveloped. 28 In Germany, informal care is crucial, partly covered by care insurance. The UK and the Netherlands have high residential care supply. Sweden and Norway have well-developed formal care services. In both countries, informal care is also partly covered by the State. Family plays a vital role in palliative and end-of-life care within the Latin American population, revealing varied attitudes towards palliative and end-of-life care and emphasising regional differences. 11 Caregivers often feel overwhelmed and require professional and social support, highlighting the need for systematic identification and assessment. In our study, professionals, for their part, expected the family to take care of their relatives, ‘the good families’, especially in Argentina. It could be related to the fact that in Latin America, the family’s importance for patients and caregivers at the end of life is often seen as a social obligation or lack of choice rather than a positive duty. 11

Who cares and why?

Family carers view caring as a moral commitment, requiring various stages of support, education and communication to ensure an individual’s end-of-life care.29,30 We have introduced a new feature that brings together the views of patients, their families and HCPs.

We emphasised that the current tendency to dichotomise autonomy as present or absent does not correspond well with actual end-of-life care practices. Our results confirm the need to see autonomy as relational, as advocated by Gomez-Virseda et al. 7 By including the lived experiences of patients and caretakers at the end of life in this analysis, we arrive at a point where we must seek other ways of thinking about autonomy. This alternate approach to the autonomy principle, known as relational autonomy, is rapidly gaining the attention of ethicists. 8

The economic invisibility of women’s care work reflects and reinforces gendered understandings of care as a ‘natural’ role for women. Furthermore, access to hospice and palliative care is a human right, but it is still limited to those with high socioeconomic status and family support. 31 Social injustices like poverty, homelessness, racism and stigma also impact patients who are at the end of life. 32 Modern hospice and palliative care services, while crucial, can favour specific individuals, causing inequalities and challenging the foundations of palliative care.

In our research, patients wanted their families to care for them while, at the same time, they wanted to protect them from the overburden it causes. Family members described caregiving as a choice but often felt lonely and at the limit of their strength, aggravated by increasing dependency and disability from the patients’ changing state but also, at times, their physical decline. They felt responsible for providing care and were satisfied that they could do so but recognised the lack of care networks and professional resources to help them. Women were involved in caregiving and care management no matter how old. Healthcare providers expected this caring role to be fulfilled by families even when they could not go any further.

Studies have shown that many women find that being a carer improves their well-being, 16 which means that caring can be a good experience in and of itself. However, as seen in our study, when caring for a family member at the end of life, women’s experiences can move along both positive and negative spectrums, and sometimes simultaneously. In palliative home care, the majority of people who die at home are men, while the majority of carers are women. 16 This trend is due to men being older than their female companions. Despite the increasing number of male carers, around 68% of carers in end-of-life care are women. In critically ill women, most family care is supplied by a female member within or outside the family. Women of any age can be involved in caregiving. 16 Female carers have been found to believe that it was their ‘duty’ to carry on this role, even after being diagnosed with several medical illnesses, resulting in increased feelings of shame or failure when they were unable to provide care. 33 They were expected to care for and support a loved one, while men were not held to the same ideal.

When family members are called to provide informal care, they are frequently asked to take on new tasks besides those they already have. It can be challenging, especially if they are asked to manage domains for which they have not gained prior experience. When these new roles are assumed, the power dynamics of their partnerships and other relationships will likely change. Women’s roles as primary carers in their families directly impact their engagement in the labour market and the jobs they apply for. 14 Sometimes, women do not think much about themselves; instead, they focus on others. We found that gendered caring was a pivotal point to highlight, bearing in mind that we would like to explore the role of family caregiving in the context of the family as a receptor of care.

Family caregivers provide emotional and financial support for a ‘good death’ for dying patients, focusing on pain-free end-of-life experiences rather than unnecessary treatments. 34 However, our interviewed patients expressed concern about family efforts and guilt for dependency. We found that family was a principal or unique care resource at the end of life. Furthermore, overburdened families could not go any further, and the only resource they found was institutionalising the patient. Some patients faced with family burdens also preferred formal care, if available. Other studies have found that some patients present a desire for a hastened death when they feel like a burden to their families. 35

Patients are universally acknowledged to have three essential needs: security, integrity and a sense of life and belonging. 10 The family carer can meet most of these needs, thanks to the intimacy of the relationship with the patient. Nonetheless, being a family carer is not without hardship. The expected task is likely to create a ‘burden’. According to an examination of UK policy papers, an evidence-based approach to policy priorities such as integrated care, individualised care and support for unpaid carers could improve palliative care outcomes. 36 Despite the importance of family engagement around the end of life and positive attitudes towards caring, homecare offers several challenges for overburdened families. It creates a need for more expert assistance. 11

Latin American family members are crucial in palliative and end-of-life care, but caregivers often feel overwhelmed and lack professional support. 11 A study found that Spain has more people with functional limitations receiving care than the UK, with more care provided outside the household. 37 The UK has the lowest use of formal care for disabled people. Family care is preferred in Southern and Eastern Europe, while Nordic and Western European countries like the Netherlands and Sweden prefer formal care services. Relatives in Germany and Sweden transfer their dependent relatives to formal care services, while countries with a more traditional family caring system pass on the dependent to informal carers. 28 From our results, we argue that families naturally take on a caring role in all countries. However, this could be different if formal care services were well developed. In our work, we did not incorporate the exploration of the availability of such care resources in all countries, which is why we based the discussion on the existing literature.11,28,37 This would open the question for future research as to whether families would take on caregiving electively and with less risk of overburdening themselves if formal services were more widely available.

The Lancet Commission on the Value of Death (2022) has proposed five principles for a realistic utopia addressing social determinants of death, dying and grieving. These principles include addressing dying as a relational and spiritual process, fostering care networks, promoting ordinary conversations about everyday death, dying and grief, and recognising death’s value. 17 Although health systems increasingly control death and dying, most of the care of the dying, hour by hour, is the responsibility of the dying, family, friends and the community.

Who decides about end-of-life care and why?

Autonomy in treatment and care decision-making is part of an unchanging narrative about a ‘good death’. 38 While autonomy and individualism are frequently associated, Collier’s (2023) review revealed that constructs of the good death could also correlate to the collectivist orientation of communities and cultures. 38 In the model proposed in our analysis, decision-making is conditioned and influenced by the end-of-life context and socio-cultural mandates. Dependency imposes care, which at the same time is imposed on the family as the only care resource. In this way, communication and decisions about who cares, where care is provided and with what resources care is provided fall to families, especially women in families. As a result, relational autonomy may be limited and conditioned by socio-cultural mandates and the availability of care resources. In some countries, these health resources limit genuine autonomy of choice.

Furthermore, social support from family members fulfils their familial obligations and is a foundation for quality end-of-life care. Pun et al. 34 suggest that family participation in end-of-life discussions should also be considered. Family participation in communication positively affected the patients’ quality of end-of-life treatment receptions. 34

Western societies are accustomed to palliative care and are prepared for early end-of-life conversations. 34 Given the prevalence of individualism, most patients in Western contexts want to make end-of-life decisions for themselves. Regardless of the implications of differing cultural norms, our study demonstrates that healthcare providers generally agreed that end-of-life communication should include the patient and family members. Meanwhile, recommendations mainly focus on the patient–clinician interaction rather than a family-oriented conversation. 39

As a result of the conditional involvement of the family in the context of end-of-life care, the concept of ‘familism’ has emerged. 40 Familism is crucial in palliative care for Latin background patients and their families. It involves a comprehensive support network, including aunts, uncles, grandparents, godparents and close family friends. Family-centred socialisation fosters connectedness and interdependence, promoting solidarity, family pride and a sense of belonging.

Latin American patients and family carers prefer shared decision-making styles, while doctors and relatives delegate information. 11 Communication is vital to conflicting preferences. Healthcare providers tried to include the family in decision-making as much as possible. Family caregiving negatively impacts women more than men, causing increased stress, anxiety, depression and unmet psychosocial needs due to higher care levels.5,29

Concerning relatives, they wished to participate and share decision-making while patients asked relatives to participate. More positively, relational theorists object to the existing ethical and legal framework, commonly conceived as a dyad between patient and physician. Yet, a patient–doctor–family triad appears more relevant in characterising what occurs in clinical practice. 7 In the triad paradigm, the family is only sometimes viewed as a threat to autonomy.

Strengths and limitations

The study explored cultural diversity in end-of-life care from the perspectives of patients, family members and healthcare professionals in 10 countries. Despite the abundance of interviews, our results are limited to a Western perspective. In addition, although we sought a more or less even participation of women and men, most countries interviewed most female caregivers. The limited participation of men could have impacted our results, but it may also reflect international trends in which men take up the role of caregivers less often than women. Although we did not conduct a differential analysis between countries regarding the assumption of the role of family carers, we found similarities in the naturalisation of this role, especially among women. Research on gender impacts in end-of-life care is needed for a clearer understanding.

As strengths of our study, the focus on the role of families in end-of-life care and decision-making, with questions about relational autonomy and shared decision-making, helped to understand more in-depth how caregiving opportunities can condition these. We also identified the role of women and socio-cultural mandates, which helped shed light on the different pressures that influence decisions to care and their potential consequences. While examining gender roles was not the original intention of the research (iLIVE Study), we found that gender was meaningful as a concept when we talked about the role of the family during our analysis. Future research should include a greater focus on gender in palliative care. Literature and policymakers should be aware of the gendered implications of family caregiving and community palliative care.

Conclusion

The role of family caregivers in end-of-life care is crucial, but it requires better support from society, healthcare teams and family systems. We discussed mainstream talks regarding autonomy, which focus on patients’ interests in isolation from their social setting. Mainstream views of autonomy, which focus on patients’ interests in isolation from their social setting, fail to consider that real-world end-of-life scenarios do not occur in a wholly individualistic, closed-off atmosphere but in an interpersonal setting. The balance between relational autonomy and socio-cultural values drives the family’s role as a caregiver. Gender is often a factor, but normative ideas influence care strategies. Healthcare providers reinforce socio-cultural mandates in families and do not recognise their potential needs as carers. Policymakers should recognise the importance of family caregivers, provide financial, social and homecare assistance and support initiatives for community-based research.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pcr-10.1177_26323524241260425 for ‘Someone must do it’: multiple views on family’s role in end-of-life care – an international qualitative study by Vilma A. Tripodoro, Verónica I. Veloso, Eva Víbora Martín, Hana Kodba-Čeh, Miša Bakan, Birgit H. Rasmussen, Sofía C. Zambrano, Melanie Joshi, Svandis Íris Hálfdánardóttir, Guðlaug Helga Ásgeirsdóttir, Elisabeth Romarheim, Dagny Faksvåg Haugen, Tamsin McGlinchey, Berivan Yildiz, Pilar Barnestein-Fonseca, Anne Goossensen, Urška Lunder and Agnes van der Heide in Palliative Care and Social Practice

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-pcr-10.1177_26323524241260425 for ‘Someone must do it’: multiple views on family’s role in end-of-life care – an international qualitative study by Vilma A. Tripodoro, Verónica I. Veloso, Eva Víbora Martín, Hana Kodba-Čeh, Miša Bakan, Birgit H. Rasmussen, Sofía C. Zambrano, Melanie Joshi, Svandis Íris Hálfdánardóttir, Guðlaug Helga Ásgeirsdóttir, Elisabeth Romarheim, Dagny Faksvåg Haugen, Tamsin McGlinchey, Berivan Yildiz, Pilar Barnestein-Fonseca, Anne Goossensen, Urška Lunder and Agnes van der Heide in Palliative Care and Social Practice

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the international consortium of the iLIVE project and all patients, relatives and healthcare providers interviewed.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Vilma A. Tripodoro  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2328-6032

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2328-6032

Eva Víbora Martín  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2680-8019

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2680-8019

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Vilma A. Tripodoro, Instituto Pallium Latinoamérica, Bonpland 2287, Ciudad de Buenos Aires (1425), Argentina; Instituto de Investigaciones Médicas Alfredo Lanari, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina; ATLANTES Global Observatory of Palliative Care, University of Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra, Spain.

Verónica I. Veloso, Instituto Pallium Latinoamérica, Buenos Aires, Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina Instituto de Investigaciones Médicas Alfredo Lanari, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Eva Víbora Martín, Fundación Cudeca, Malaga, Spain.

Hana Kodba-Čeh, University Clinic of Pulmonary and Allergic Diseases Golnik, Research Department, Golnik, Slovenia.

Miša Bakan, University Clinic of Pulmonary and Allergic Diseases Golnik, Research Department, Golnik, Slovenia.

Birgit H. Rasmussen, Institute for Palliative Care, Lund University and Region Skåne, Sweden Department of Health Sciences, Lund University, Sweden.

Sofía C. Zambrano, Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland University Centre for Palliative Care, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland.

Melanie Joshi, Department of Palliative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany.

Svandis Íris Hálfdánardóttir, Palliative Care Unit, Landspitali – The National University Hospital of Iceland, Reykjavik Iceland.

Guðlaug Helga Ásgeirsdóttir, Palliative Care Unit, Landspitali – The National University Hospital of Iceland, Reykjavik Iceland.

Elisabeth Romarheim, Regional Centre of Excellence for Palliative Care, Western Norway, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway.

Dagny Faksvåg Haugen, Regional Centre of Excellence for Palliative Care, Western Norway, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway; Department of Clinical Medicine K1, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

Tamsin McGlinchey, Institute of Life Course and Medical Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK.

Berivan Yildiz, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Pilar Barnestein-Fonseca, Fundación Cudeca, Malaga, Spain; Instituto IBIMA – Plataforma Bionand, Málaga, Spain.

Anne Goossensen, University of Humanistic Studies, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Urška Lunder, University Clinic of Pulmonary and Allergic Diseases Golnik, Research Department, Golnik, Slovenia.

Agnes van der Heide, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Declaration of Helsinki, 2013) and approved by the relevant Ethics Committees of all participating countries: Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden (#2020-01956); Medical Ethics Committee of Slovenia (#0120-129/2020/3); Bern Cantonal Ethical Commission (#2020-02569 and Req-2019-01153); Ethics Commission of Cologne University’s Faculty of Medicine (#19-1456_3); Health Research Authority (HRA) and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW) (#272927), United Kingdom; Comité de Ética de la Investigación Provincial de Málaga, Hospital Regional Universitario de Malaga, Spain; The National Bioethics Committee Iceland (#VSN-20-129;#VSNb2019090032/03.01); Medical Research Ethics Committees United (MEC-U), The Netherlands (#R20.004); Dictamen del Comité de ética del Instituto de Investigaciones Médicas A. Lanari, University of Buenos Aires (#Protocolo Nro 289) and Hospital Privado-Centro mëdico de Córdoba S.A (#HP4-322), Argentina; Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics South East D, Norway (#35035) and registered at the Clinical Trials Register (#NCT04271085). All participants provided written and oral consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Vilma A. Tripodoro: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Verónica I. Veloso: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Eva Víbora Martín: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Hana Kodba-Čeh: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Miša Bakan: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Birgit H. Rasmussen: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Sofía C. Zambrano: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Melanie Joshi: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Svandis Íris Hálfdánardóttir: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Guðlaug Helga Ásgeirsdóttir: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Elisabeth Romarheim: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Dagny Faksvåg Haugen: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Tamsin McGlinchey: Data curation; Formal analysis; Writing – review & editing.

Berivan Yildiz: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation.

Pilar Barnestein-Fonseca: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Anne Goossensen: Conceptualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Urška Lunder: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; review & editing.

Agnes van der Heide: Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement ID: 825731.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author. However, due to privacy or ethical restrictions, the data are not publicly available.

References

- 1. Ferrell BR, Coyle N. Social aspects of care. Oxford University Press, New York, 2016, 126 p. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Charles N, Davies CA. My family and other animals: pets as kin. Sociol Res Online 2008; 13: 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stajduhar KI, Funk L, Outcalt L. Family caregiver learning – how family caregivers learn to provide care at the end of life: a qualitative secondary analysis of four datasets. Palliat Med 2013; 27: 657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Payne S. EAPC task force on family carers white paper on improving support for family carers in palliative care: part 1. Eur J Palliat Care 2010; 17: 8. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morgan T, Ann Williams L, Trussardi G, et al. Gender and family caregiving at the end-of-life in the context of old age: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2016; 30: 616–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reigada C, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Anna Novella S, et al. The caregiver role in palliative care: a systematic review of the literature. Health Care Curr Rev 2015; 3: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gómez-Vírseda C, de Maeseneer Y, Gastmans C. Relational autonomy in end-of-life care ethics: a contextualized approach to real-life complexities. BMC Med Ethics 2020; 21: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gómez-Vírseda C, de Maeseneer Y, Gastmans C. Relational autonomy: what does it mean and how is it used in end-of-life care? A systematic review of argument-based ethics literature. BMC Med Ethics 2019; 20: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giger JN, Davidhizar R. The Giger and Davidhizar transcultural assessment model. J Transcult Nurs 2002; 13: 185–188; discussion 200–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Veloso VI, Tripodoro VA. Caregivers burden in palliative care patients: a problem to tackle. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2016; 10: 330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dittborn M, Turrillas P, Maddocks M, et al. Attitudes and preferences towards palliative and end of life care in patients with advanced illness and their family caregivers in Latin America: a mixed studies systematic review. Palliat Med 2021; 35: 1434–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tripodoro V, Veloso V, Llanos V. Sobrecarga del cuidador principal de pacientes en cuidados paliativos. Argument Rev Crit Soc 2015; 17. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Addati L, Cattaneo U, Esquivel V, et al. Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work, https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv:80132 (2018, accessed 5 December 2023).

- 14. Rodriguez Ferrari A. The invisibility of women’s unpaid work in gender policies. Pol Perspect 2021; 28: 1. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abel J, Kellehear A. (eds). Oxford textbook of public health palliative care. Oxford University Press, 2022, 320 p. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mackinnon CJ. Applying feminist, multicultural, and social justice theory to diverse women who function as caregivers in end-of-life and palliative home care. Palliat Support Care 2009; 7: 501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sallnow L, Smith R, Ahmedzai SH, et al. Report of the lancet commission on the value of death: bringing death back into life. Lancet 2022; 399: 837–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Green A, Jerzmanowska N, Green M, et al. ‘Death is difficult in any language’: a qualitative study of palliative care professionals’ experiences when providing end-of-life care to patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Palliat Med 2018; 32: 1419–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gysels M, Evans N, Meñaca A, et al. Culture and end of life care: a scoping exercise in seven European countries. PLoS One 2012; 7: e34188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yildiz B, Allan S, Bakan M, et al. Live well, die well – an international cohort study on experiences, concerns and preferences of patients in the last phase of life: the research protocol of the iLIVE study. BMJ Open 2022; 12: e057229. [Google Scholar]

- 21. White N, Kupeli N, Vickerstaff V, et al. How accurate is the ‘Surprise Question’ at identifying patients at the end of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2017; 15: 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Highet G, Crawford D, Murray SA, et al. Development and evaluation of the supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT): a mixed-methods study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014; 4: 285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Giger JN, Davidhizar RE, Fordham P. Multi-cultural and multi-ethnic considerations and advanced directives: developing cultural competency. J Cult Divers 2006; 13: 3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Srivastava R. The ABC (and DE) of cultural competence in clinical care. Ethn Inequal Health Soc Care 2008; 1: 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Price A, Goodwin L, Rayner L, et al. Illness perceptions, adjustment to illness, and depression in a palliative care population. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012; 43: 819–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 2019; 11: 589–597. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zigante V, Others. Informal care in Europe: exploring formalisation, availability and quality. European Commission, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gott M, Morgan T, Williams L. Gender and palliative care: a call to arms. Palliat Care Soc Pract 2020; 14: 2632352420957997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tieman J, Hudson P, Thomas K, et al. Who cares for the carers? Carerhelp: development and evaluation of an online resource to support the wellbeing of those caring for family members at the end of their life. BMC Palliat Care 2023; 22: 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stajduhar KI. Provocations on privilege in palliative care: are we meeting our core mandate? Prog Palliat Care 2020; 28: 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rowley J, Richards N, Carduff E, et al. The impact of poverty and deprivation at the end of life: a critical review. Palliat Care 2021; 15: 26323524211033873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wong AD, Phillips SP. Gender disparities in end of life care: a scoping review. J Palliat Care 2023; 38: 78–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pun J, Chow JCH, Fok L, et al. Role of patients’ family members in end-of-life communication: an integrative review. BMJ Open 2023; 13: e067304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pestinger M, Stiel S, Elsner F, et al. The desire to hasten death: using grounded theory for a better understanding ‘When perception of time tends to be a slippery slope.’ Palliat Med 2015; 29: 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sleeman KE, Timms A, Gillam J, et al. Priorities and opportunities for palliative and end of life care in United Kingdom health policies: a national documentary analysis. BMC Palliat Care 2021; 20: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Solé-Auró A, Crimmins EM. Who cares? A comparison of informal and formal care provision in Spain, England and the USA. Ageing Soc 2014; 34: 495–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Collier A, Chapman M. Matters of care and the good death – rhetoric or reality? Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2023; 17: 208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kastbom L, Karlsson M, Falk M, et al. Elephant in the room – family members’ perspectives on advance care planning. Scand J Prim Health Care 2020; 38: 421–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Adames HY, Chavez-Dueñas NY, Fuentes MA, et al. Integration of Latino/a cultural values into palliative health care: a culture centered model. Palliat Support Care 2014; 12: 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pcr-10.1177_26323524241260425 for ‘Someone must do it’: multiple views on family’s role in end-of-life care – an international qualitative study by Vilma A. Tripodoro, Verónica I. Veloso, Eva Víbora Martín, Hana Kodba-Čeh, Miša Bakan, Birgit H. Rasmussen, Sofía C. Zambrano, Melanie Joshi, Svandis Íris Hálfdánardóttir, Guðlaug Helga Ásgeirsdóttir, Elisabeth Romarheim, Dagny Faksvåg Haugen, Tamsin McGlinchey, Berivan Yildiz, Pilar Barnestein-Fonseca, Anne Goossensen, Urška Lunder and Agnes van der Heide in Palliative Care and Social Practice

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-pcr-10.1177_26323524241260425 for ‘Someone must do it’: multiple views on family’s role in end-of-life care – an international qualitative study by Vilma A. Tripodoro, Verónica I. Veloso, Eva Víbora Martín, Hana Kodba-Čeh, Miša Bakan, Birgit H. Rasmussen, Sofía C. Zambrano, Melanie Joshi, Svandis Íris Hálfdánardóttir, Guðlaug Helga Ásgeirsdóttir, Elisabeth Romarheim, Dagny Faksvåg Haugen, Tamsin McGlinchey, Berivan Yildiz, Pilar Barnestein-Fonseca, Anne Goossensen, Urška Lunder and Agnes van der Heide in Palliative Care and Social Practice