Abstract

Rhesus monkeys and other nonhuman Old World primates are naturally infected with lymphocryptoviruses (LCV) that are closely related to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). A rhesus LCV isolate (208-95) was derived from a B-cell lymphoma in a simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaque. The EBNA-2 homologues from 208-95 and a previous rhesus LCV isolate (LCL8664) were polymorphic on immunoblotting, so the EBNA-2 genes from these two rhesus LCV were cloned, sequenced, and compared. The EBNA-2 genes have 40% nucleotide and 41% amino acid identities, and the differences are similar to those between the type 1 and type 2 EBV EBNA-2. Sequence from a portion of the LMP1 gene which is extremely divergent among different LCV was virtually identical between the 208-95 and LCL8664 strains, confirming a common rhesus LCV background. Thus, the EBNA-2 polymorphism defines the presence of two different rhesus LCV types, and both rhesus LCV types were found to be prevalent in the rhesus monkey population at the New England Regional Primate Research Center. The existence of two rhesus LCV types suggests that the selective pressure for the evolution of two LCV types is shared by human and nonhuman primate hosts.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a gammaherpesvirus in the lymphocryptovirus (LCV) subgroup. EBV is a major causative agent of infectious mononucleosis and is also associated with Burkitt’s lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, and Hodgkin’s disease. Two different types of EBV, EBV-1 and EBV-2, infect the human population. These EBV types were originally defined by type-specific antibody responses and genetic polymorphisms in the EBNA-2 latent infection gene (5, 6, 35). Subsequent studies showed that the type-specific serologic reactivity and genetic polymorphisms could be extended to the EBNA-3 gene family (23, 24, 26). The allelic polymorphism varies from 55% amino acid homology between type 1 and type 2 EBNA-2 to 84, 80, and 72% amino acid homology for the EBNA-3A, -3B, and -3C alleles.

Type 1 EBV has been noted to be more efficient than type 2 EBV for immortalizing B-cell growth in vitro (22), and genetic studies prove this phenotype is due to the EBNA-2 polymorphism (4, 12). However, in vivo, the biologic significance of the two EBV types is not clear. There is no obvious correlation between EBV type and EBV-associated disease or virus tropism for specific cell types. EBV-1 infection is much more common and is present in >90% of humans. The EBV-1 dominance can be shown either by type-specific serologic assays, spontaneous outgrowth of EBV-infected B cells in vitro, or by PCR amplification of type-specific DNA sequences from oral secretions (11, 32).

It is controversial whether immunocompetent individuals can be coinfected with multiple EBV types. Two laboratories have identified subsets of healthy individuals in whom both EBV-1 and EBV-2 DNA were detected in oral secretions by type-specific PCR amplification (1, 28). In contrast, another group has identified only one EBV type in oral secretions of all healthy individuals studied (32). It is unclear whether these disparate findings are due to geographic, epidemiological, or technical differences. However, immunosuppression, as seen in AIDS patients, clearly increases the incidence of EBV-2 infection and EBV-1/EBV-2 coinfection (25, 27). Whether immunocompetent hosts can be repeatedly infected with EBV has important implications regarding the effectiveness of natural immunity and the potential for vaccination against EBV infection.

Old World nonhuman primates are naturally infected with a LCV closely related to EBV. The EBV and nonhuman LCV genomes are highly homologous, and the repertoire of lytic and latent infection genes is virtually identical (2, 9, 10, 13–15, 17, 18, 33). EBV and nonhuman LCV also share common biologic properties, including high prevalence in the adult population, persistent infection in the peripheral blood and oropharynx, and potential for LCV-induced malignancies in immunosuppressed hosts (7, 8, 19). For these reasons, experimental infection of rhesus monkeys with rhesus LCV has been proposed as a highly relevant animal model for EBV infection (19). In the current study, we report that two types of rhesus LCV have evolved with genetic polymorphisms similar to those seen between EBV-1 and EBV-2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and antibody.

IB4 and AG876 are EBV-1- and EBV-2 (human herpesvirus 4)-infected B-cell lines. S594 is a baboon LCV (cercopithicine herpesvirus 12 or herpesvirus papio)-infected B-cell line derived by spontaneous outgrowth from baboon peripheral blood lymphocytes (20). LCL8664 is a rhesus LCV (cercopithicine herpesvirus 15)-infected B-cell line derived from a retro-orbital B-cell lymphoma in a rhesus monkey (21). All lymphocyte cell lines were maintained in RPMI containing 10% horse serum and 2 mM L-glutamine. The murine monoclonal antibody, PE2 (34), recognizes an epitope in the EBNA-2 C-terminal domain and was chemically cross-linked to horseradish peroxidase for immunoblotting.

EBNA-2 cloning.

The rhesus LCV LCL8664 EBNA-2 was cloned and sequenced from a rhesus LCV cosmid clone (CC1) and is described elsewhere (19a). Most of the rhesus LCV 208-95 EBNA-2 was amplified by PCR, using degenerative primers (NA2F, CCAACAACCTTYTAAGCACC, and NA2R, ATACCARTCTTCWGGGAAGAG) based on EBV and LCL8664 EBNA-2 sequences. The remaining portion of 208-95 EBNA-2 was PCR amplified using a 5′ primer (1125F, CCCATGCCTCATCTAAGTCC) based on the N-terminal 208-95 EBNA-2 sequence and a 3′ primer (3′UTR, GTTTAAYTAATAKAATGACAG) based on 3′ untranslated EBV and LCL8664 EBNA-2 sequence. PCR amplifications of the EBNA-2 C terminus from other type 2 rhesus LCV isolates were performed using the primer pairs XMASF (ATCCGCCACCATTGAAAT) and 3′ UTR, 1125F, and XMASR (TATACGGAGTCACAAGGTT) or XMASF and XMASR. Each PCR product was ligated into the EcoRV site of pBluescript (Stratagene Co.), and two or three clones from each amplification were sequenced.

PCR amplification of the rhesus LCV LMP1 cytoplasmic domain.

A portion of the carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic domain from the rhesus LCV 208-95 LMP1 was cloned by PCR amplification using primers (REL1-774F, ATATCACCATTTACATGGC, and REL1-1451R, CTGGGTGTGGTAGATGATCGG) based on the LCL8664 LMP1 sequence (10). The 640-bp PCR product was ligated into the EcoRV site of pBluescript (Stratagene), and two clones were sequenced.

Rhesus LCV type-specific PCR amplification.

Oral washes were obtained by inoculating and aspirating 1 cc of water into the mouths of randomly selected rhesus monkeys in the conventional colony at the New England Regional Primate Research Center (NERPRC). The oral wash samples were heat inactivated for 10 min at 100°C, digested with 100 μg of proteinase K/ml for 1 h at 45°C, heat inactivated again, and clarified by centrifugation. LCL8664-specific primers, T1E2F (TAAAGTTCCAACTGTGCAAT) and T1E2R (CTTTGCCCTTGCCCTTTTG), and 208-95-specific primers, T2E2F (TGCCCCAAGAGTAGTAACA) and T2E2R (CTTGCCCTTGCCCTTTTG) were designed to specifically amplify either type 1 or type 2 rhesus LCV EBNA-2 DNA. The PCR products were also probed by hybridization with type-specific oligonucleotide probes (T1E2I, TTACCCGTTCCAAGGCCTCT, and T2E2I, TCAATTACCTTCGTTACACT).

Nucleotide sequences and analysis.

The EBV-1 (HS4U2IR2A), EBV-2 (HS4U2IR2), and baboon LCV (HSVEBNA2A) EBNA-2 sequences were obtained from GenBank. The LCL8664 (19a) and 208-95 EBNA-2 (AF 183139 and AF 183140) sequences have been submitted to GenBank. The nucleotide and amino acid sequences were aligned by the CLUSTAL method in the Megalign program of Lasergene software (DNASTAR Inc.).

RESULTS

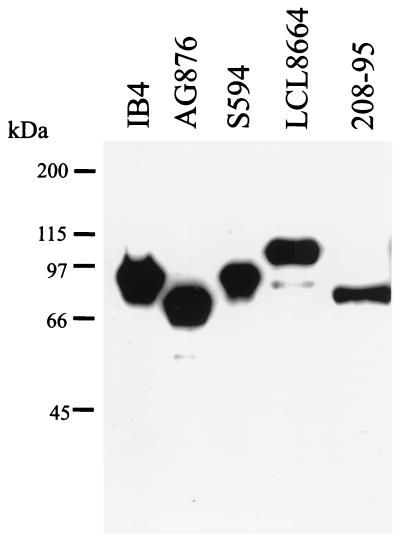

A simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected rhesus macaque (Mm208-95) at the NERPRC was diagnosed with a B-cell lymphoma. A lymph node biopsy was obtained from this animal, and a spontaneous, continuously growing cell line, 208-95, was obtained by tissue culture of the lymph node cells. Since LCVs are a common cause of B-cell lymphomas in humans and nonhuman Old World primates, immunoblotting was performed on the 208-95 cell line to test for LCV latent infection gene expression. As shown in Fig. 1, the PE2 monoclonal antibody detects expression of EBV-1 (IB4) and EBV-2 (Ag876) EBNA-2s and related homologues in baboon LCV- (S594) and rhesus LCV (LCL8664)-infected B cells. Expression of an EBNA-2 homologue was also detected in the 208-95 cell line, suggesting that the 208-95 cell line was infected with a LCV closely related to EBV. The cell-free tissue culture supernatants from the 208-95 cell line were able to immortalize rhesus monkey peripheral blood lymphocytes, and EBV-related DNA sequences were detected by Southern blot cross-hybridization with EBV DNA probes, confirming LCV infection in the 208-95 cell line (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot of EBNA-2 proteins from different LCV-infected B cells. IB4 and AG876 are type 1 and type 2 EBV-infected B cells, respectively. S594 is a baboon LCV-infected B-cell line, and LCL8664 and 208-95 are rhesus LCV-infected B-cell lines. The blot was probed with an EBNA-2-specific monoclonal antibody, PE2. Molecular size markers are shown at the left.

Interestingly, the EBNA-2 protein from the 208-95 cell line migrated as a 70-kDa band, but the EBNA-2 in the LCL8664 cell line migrated as a 100-kDa band. The EBNA-2 size polymorphism in these two different rhesus LCV isolates suggested either significant strain variation or major differences in the EBNA-2 polyproline repeats. To distinguish these possibilities, we cloned and sequenced the EBNA-2 homologues from the LCL8664 and 208-95 cell lines. The LCL8664 and 208-95 EBNA-2 open reading frames (ORF) are 1,818 and 1,395 nucleotides, respectively, with only 40% nucleotide homology to each other. Both rhesus LCV EBNA-2 genes are equally distant from EBV-1 EBNA-2 (36 and 37% nucleotide homology) or EBV-2 EBNA-2 (32 and 37% nucleotide homology) as shown in Table 1. In contrast, the nontranslated regions immediately upstream (32 nucleotides) and downstream (82 nucleotides) of the EBNA-2 open reading frame have 81 and 67% nucleotide homology between LCL8664 and 208-95. Sequence divergence in the coding regions for the latent infection genes compared to sequence conservation in the lytic infection genes and noncoding regions has been a common pattern among different LCVs (2, 9, 10, 17, 18, 33).

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide and amino acid homologies among LCV EBNA-2s

| % Similarity (nucleotide/amino acid) of EBNA-2 from:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBV type 2 | Baboon LCV | Rhesus LCV type 1 | Rhesus LCV type 2 | |

| EBV type 1 | 64.9/54.7 | 32.2/27.7 | 35.5/29.7 | 37.4/32.0 |

| EBV type 2 | 33.6/33.0 | 31.9/30.1 | 37.2/31.4 | |

| Baboon LCV | 39.5/26.7 | 39.2/35.7 | ||

| Rhesus LCV type 1 | 40.3/41.1 | |||

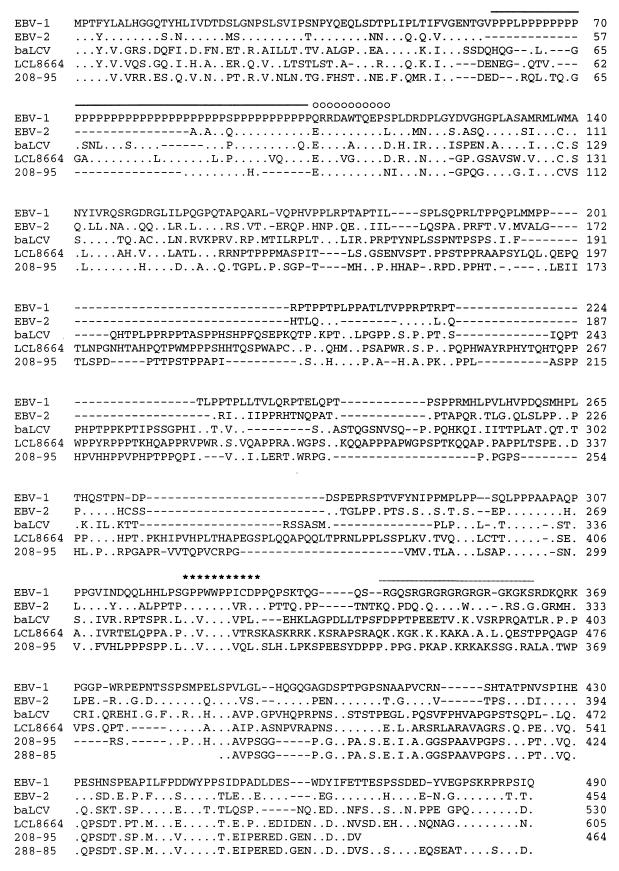

The LCL8664 and 208-95 EBNA-2 genes encode 605 and 464 amino acids, respectively, and have 41% of amino acid identity to each other (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Thus, these rhesus LCV EBNA-2s are more divergent from each other compared to the differences between EBV-1 and EBV-2 EBNA-2s (55% amino acid identity to each other). Previously defined domains within EBV EBNA-2 have been conserved in both rhesus LCV EBNA-2s, including the N-terminal negatively charged domain, the polyproline track, a highly charged domain (Q/ERRDAWTQEP), the RBP-Jκ/CBF1 binding sequence, and the C-terminal acidic domain (Fig. 2 and 3).

FIG. 2.

Amino acid alignment of LCL8664 and 208-95 rhesus LCV EBNA-2 with type 1 and type 2 EBV EBNA-2 and baboon LCV EBNA-2. Identical amino acid residues (.) and specific substitutions relative to type 1 EBV EBNA-2 (B95) are shown. The partial C-terminal EBNA-2 sequence from an independent rhesus LCV isolate (288-85) is also shown. Gaps introduced for proper alignment are indicated (−). A highly charged region (○) and essential amino acids of the RBP-Jκ/CBF1 binding region (∗) are indicated above the B95 sequence. The polyproline track and partial arginine-glycine (RG) domain are shown by the solid line and dotted line, respectively.

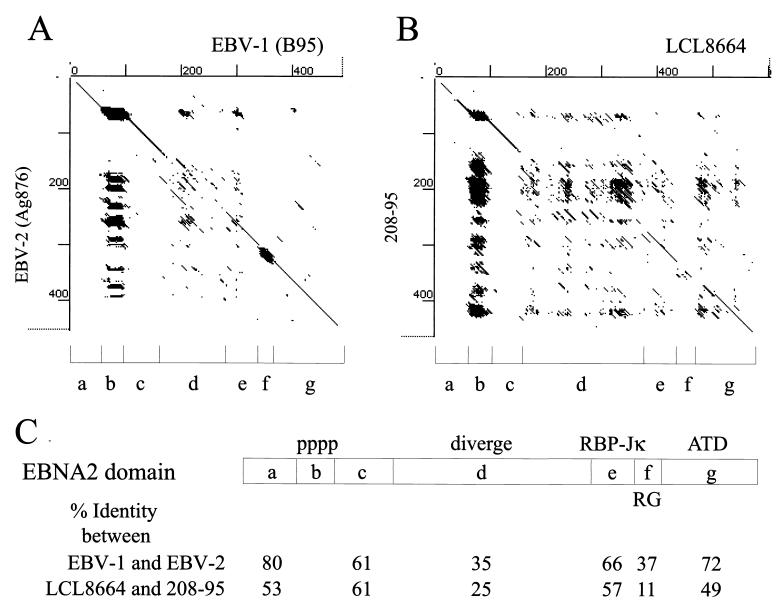

FIG. 3.

Dot matrix representation of amino acid homology between (A) EBV-1(B95) and EBV-2 (AG876) EBNA-2s and between (B) LCL8664 and 208-95 EBNA-2s. Domains (a to g) were identified in EBV EBNA-2 by sequence or functional characteristics and include the N-terminal negatively charged domain (a), polyproline track (b), the highly charged domain (Q/ERRDAWTQEP) (c), the divergent region between type 1 and type 2 EBV EBNA-2s (d), the RBP-Jκ/CBF1 binding sequence (e), the arginine-glycine rich domain (f), and the C-terminal acidic transactivating domain (g). (C) The percent amino acid identities between EBV-1 and EBV-2 EBNA-2s or between type 1 and type 2 rhesus LCV EBNA-2s are shown for each domain.

A large divergent region between the two rhesus LCV EBNA-2 has only 25% amino acid identity and corresponds positionally with the most divergent region between EBV-1 and EBV-2 EBNA-2s (35% amino acid identity between amino acids 161 to 291 of EBV-1 EBNA-2; Fig. 2 and domain d in Fig. 3). This region consists of 236 residues in the LCL8664 EBNA-2 versus 149 residues in the 208-95 EBNA-2 and represents a major component of the size heterogeneity. The argine-glycine-rich domain (domain f in Fig. 3) is also a region of divergence between EBV types and rhesus LCV types. The pattern of domain homology and divergence between the two rhesus LCV EBNA-2s is strikingly similar to the patterns between EBV-1 and EBV-2 EBNA-2s (Fig. 3). These results suggest that LCVs infecting humans and rhesus monkeys are under similar selective pressures, resulting in the evolution of two EBNA-2 alleles in each species.

Two other features of interest were noted. First, the 208-95 EBNA2 has just 12 prolines in the polyproline track. Studies of recombinant viruses indicate that genetically engineered EBNA-2 genes with as few as 7 proline residues are sufficient for B-cell immortalization in vitro (30), and 12 prolines represent the shortest polyproline repeat in a naturally occurring EBNA-2 from any LCV species. It is unknown whether additional factors in vivo may select for larger polyproline repeats. Second, the premature termination codon in the 208-95 EBNA-2 gene results in truncation of the C-terminal 24 amino acids compared to those of LCL8664 and EBV EBNA-2s (Fig. 2). PCR amplification with three different primer sets and sequencing of at least two clones from each PCR amplification demonstrated that the C-terminal truncation is reproducibly present in the 208-95 EBNA-2. This naturally occurring C-terminal truncation is similar to a C-terminal 21-amino-acid mutation genetically engineered into a recombinant EBV which showed a nearly wild-type transformation phenotype in vitro (3).

If the 208-95 and LCL8664 represented two different types of naturally occurring rhesus LCV, we would predict that the LMP1 genes from both isolates should be nearly identical. To address this, we cloned and sequenced a portion of the LMP1 gene from the 208-95 cell line, including the LMP1 sixth transmembrane domain and the carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic domain immediately adjacent to the plasma membrane. The 208-95 LMP1 sequence (640 nucleotides) from this region was identical to the LCL8664 LMP1 sequence except for three nucleotides, resulting in two amino acid substitutions (D to G at amino acid 358 and A to G at amino acid 386 of LCL8664-LMP1). These amino acid changes did not involve the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) binding motif located in the proximal cytoplasmic terminal activation region 1. Because of the dramatic divergence among EBV, baboon LCV, and rhesus LCV LMP1 sequences (10), the nearly identical LMP1 sequence from 208-95 and LCL8664 is strong evidence that these are rhesus LCV isolates. Therefore, we arbitrarily refer to the LCL8664 isolate as type 1 rhesus LCV and the 208-95 isolate as type 2 rhesus LCV.

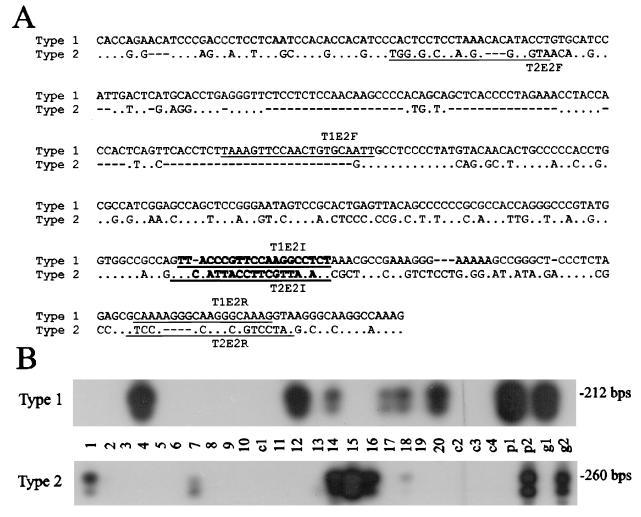

Since the LCL8664 cell line was derived from an animal at the Tulane Regional Primate Research Center (21) and the 208-95 cell line was derived from an animal at the NERPRC, we asked whether both rhesus LCV types are prevalent in the same animal population. The PCR primers were designed to specifically amplify type 1 and 2 rhesus LCV EBNA-2s (Fig. 4A), and the specificity of the primer pairs can be demonstrated by using plasmid DNA or cell genomic DNA from type 1 or type 2 rhesus LCV-infected cells (Fig. 4B, lanes p1/p2 and g1/g2). Type-specific PCR amplification was performed on DNA extracted from oral washes of 20 rhesus monkeys selected randomly from the NERPRC conventional colony. All animals were seropositive to rhesus LCV viral capsid antigen (data not shown). Mock water samples (c1 and c2) were prepared at the same time as the oral washes and processed in parallel with all animal specimens to control for possible contamination. Oral washes from half of the animals were positive for rhesus LCV-specific DNA. This frequency is comparable to the episodic viral shedding detected by PCR in oral washes from humans and the episodic oral shedding we have detected in experimentally infected rhesus monkeys (19, 31). Type 1 rhesus LCV DNA was detected in oral washes from six animals, and type 2 rhesus LCV DNA was detected from six animals, indicating that both rhesus LCV types are prevalent in the NERPRC colony.

FIG. 4.

Type-specific PCR for type 1 and type 2 rhesus LCV EBNA-2s. (A) Nucleotide sequence alignment from a divergent region between type 1 and type 2 rhesus LCV EBNA-2s. Type 1-specific primers (T1E2F and T1E2R) and type 2-specific primers (T2E2F and T2E2R) are underlined and type-specific probes (T1E2I and T2E2I) are in bold type. (B) PCR amplification for type 1 and type 2 rhesus LCV EBNA-2s from oral washes of rhesus monkeys. PCR amplification was performed on DNA extracted from oral washes of LCV-seropositive rhesus monkeys at the NERPRC (lanes 1 to 20). Control amplifications with rhesus LCV type 1 EBNA-2 from plasmid DNA (lane p1) or genomic DNA from type 1 rhesus LCV-infected cells (lane g1) and type 1 EBNA-2 from plasmid DNA (lane p2) or genomic DNA from type 2 rhesus LCV-infected cells (lane g2) are shown. c1 and c2 are negative control samples collected and processed in parallel with the animal specimens. c3 and c4 represent additional negative control reactions for the PCRs. The exposures shown for the controls (lanes c3, c4, p1, p2, g1, and g2) are approximately 1/10 the time of the sample lanes. The c1 and c2 controls were exposed for the same amount of time as the samples in lanes 1 to 20.

Finally, to determine whether the C-terminal truncation of 208-95 EBNA-2 was common to all type 2 rhesus LCV EBNA-2s, the C-terminal portion of the EBNA-2 gene was cloned and sequenced from two oral washes positive for type 2 rhesus LCV. Multiple clones from each animal were cloned and sequenced. The nucleotide sequences from these two independent type 2 rhesus LCV isolates showed more than 97% nucleotide identity with the 208-95 EBNA-2 but did not have the premature termination codon present in the 208-95 EBNA-2. The amino acid sequence of an independent rhesus LCV type 2 isolate (288-85) is shown in Fig. 2. Thus, the 208-95 EBNA-2 appears to be a natural mutant of the type 2 rhesus LCV EBNA-2, and the EBNA-2 C terminus appears to be dispensable for B-cell immortalization in vitro and for oncogenesis in vivo.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that the evolution of two LCV types has been conserved in humans and nonhuman primates. In a given host species, these two virus types can be defined by unique EBNA-2 alleles. The biological significance for two LCV types is not clear. There is no obvious disease association or tissue tropism demonstrated by EBV-1 and EBV-2. For rhesus LCV, both types have oncogenic potential since both prototypic isolates were derived from B-cell lymphomas. It is interesting to note that the 208-95 cell line grows very slowly and the progeny immortalized with 208-95 LCV also grow very slowly, similar to EBV-2-infected B cells. It is difficult to determine whether this represents a significant difference since only single isolates of type 1 and 2 rhesus LCV are available for comparison. How such an in vitro growth phenotype might affect pathogenesis in vivo is also unclear since both types are oncogenic in humans and rhesus monkeys. However, the similar evolution of type 1 and 2 EBNA-2s in human and nonhuman primates suggests that the type-specific polymorphisms are not random and that each allele confers a selective advantage in vivo.

The existence of two LCV types provides the opportunity to ask whether infection with one virus type induces protective immunity against infection with another virus type. In immunocompetent humans, the answer remains ambiguous. Two groups have reported that both EBV-1 and EBV-2 DNA could be detected in oral secretions from a small subset of healthy individuals, using type-specific PCR amplification (1, 28). In contrast, another group has reported that only one EBV type could be recovered from healthy individuals, using either PCR amplification or spontaneous outgrowth of EBV-infected B cells (32). However, immunosuppression, as seen in AIDS patients, is clearly associated with an increased prevalence of EBV-2 infection and coinfection with two EBVs (25, 27, 29). An unanswered question is whether immunosuppression results in an increased susceptibility to infection with a second EBV type or whether immunosuppression permits higher viral loads, making a preexisting coinfection more readily detectable. It is also not known whether dual infection in the population is sustained primarily by simultaneous transmission of two virus types from a dually infected individual or by sequential transmission from singly infected individuals.

In the current study, coinfection with two different rhesus LCV types was found in 20% (2 of 10) rhesus monkeys shedding virus from the oropharynx. In one animal, the type 2 signal was barely detectable, but in another animal the signals from both types were more comparable in magnitude. Similar results were obtained on repeat assays. These data are comparable to two human studies which found coinfection in 9 and 14% of humans shedding EBV (1, 28). However, the frequency of coinfection in rhesus monkeys may be lower than expected given the following epidemiologic considerations. Newborn rhesus monkeys generally lose maternal antibodies and become rhesus LCV seronegative within 6 months after birth, but by 1 year of age, approximately 70% of the rhesus monkeys at the NERPRC are LCV infected and become rhesus LCV seropositive (29a). This more rapid seroconversion among rhesus monkeys versus that in humans may be a result of group housing and frequent exposures to infectious oral secretions, e.g., during preening between animals. In addition, the equal prevalence of both LCV types in rhesus monkeys means animals are very likely to encounter a second LCV type. Furthermore, this study was performed on a cohort of older animals (mean age, 13 years), suggesting that coinfection with both rhesus LCV types may not be a common event relative to the number of exposures. PCR amplification would also not be able to distinguish whether LCV colonization, e.g., oropharyngeal infection without peripheral blood infection, might be a possible cause for transient viral shedding of a second LCV type. Genetic differences in immune responses may also contribute to instances in which infection with one virus type may not induce protective immunity to infection with a second type.

The similarity between LCVs, which naturally infect humans and Old World nonhuman primates, has been a strong argument for the use of a rhesus monkey animal model for EBV infection (19). The epidemiology and biology of these viruses are nearly identical. In rhesus monkeys and humans, LCV infections are prevalent and persistent in both peripheral blood B cells and the oropharynx. Persistent infection is generally asymptomatic, but infection with immunodeficiency-inducing retroviruses, such as HIV and SIV, increases the risk of LCV-induced malignancies. The LCVs also have strong genetic similarities. The genomes are colinear and encode a similar repertoire of lytic and latent genes. The lytic genes generally have a high degree of sequence similarity and in many cases are functionally interchangeable. For example, the EBV lytic transactivator, BZLF1 can induce lytic cycle infection when introduced into rhesus LCV-infected cells and when rhesus LCV glycoproteins (gp350) are allowed to infect human B cells (19). Although latent genes are less well conserved at a sequence level, they also demonstrate a high degree of functional conservation and interaction of EBNA-2 with RBP-Jκ/CBF1 and LMP1 with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (10, 16). The coevolution of type 1 and type 2 EBNA-2s in the rhesus LCVs provides additional evidence for the strong similarities between EBV and rhesus LCV.

Questions regarding multiplicity of infection and induction of protective immunity can be experimentally addressed in the rhesus monkey model. In previous experiments, animals rechallenged with the same rhesus LCV isolate did not develop acute responses detected in primary infection (19). This was consistent with the observation that humans usually experience EBV-induced infectious mononucleosis only once. The identification of a second rhesus LCV type provides a means for testing whether an immunocompetent animal can be sequentially coinfected with two LCV types. Animals infected with one rhesus LCV type can be challenged with oral inoculation of a second rhesus LCV type, and the genetic polymorphisms can be used to distinguish which viral types are shed in oral secretions and are present in peripheral blood after challenge. Low viral load and limits of detection may still be problematic, but SIV infection may provide a means of inducing immunosuppression and testing for the possibility of preexisting coinfection. It remains to be determined whether protective immunity can be induced by natural infection or vaccination, but the rhesus monkey animal model should be useful for addressing both questions. The identification of a second rhesus LCV type provides an experimental system for reproducing the polymorphisms typically encountered by human exposure to two EBV types.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by grants from the Public Health Service (CA68051 and CA65319) and by support to the New England Regional Primate Research Center (USPHS P51RR00168).

We thank Ronald Desrosiers and Sue Czajak for identifying and providing tissue from Mm208-95.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apolloni A, Sculley T B. Detection of A-type and B-type Epstein-Barr virus in throat washings and lymphocytes. Virology. 1994;202:978–981. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blake N W, Moghaddam A, Rao P, Kaur A, Glickman R, Cho Y, Marchinim A, Haigh T, Johnson R P, Rickinson A B, Wang F. Inhibition of antigen presentation by the glycine/alanine repeat domain is not conserved in simian homologues of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. J Virol. 1999;73:7381–7389. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7381-7389.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen J I, Wang F, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 mutations define essential domains for transformation and transactivation. J Virol. 1991;65:2545–2554. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2545-2554.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen J I, Wang F, Mannick J, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 is a key determinant of lymphocyte transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9558–9562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dambaugh T, Hennessy K, Chamnankit L, Kieff E. U2 region of Epstein-Barr virus DNA may encode Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:7632–7636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dambaugh T, Wang F, Hennessy K, Woodland E, Rickinson A, Kieff E. Expression of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 in rodent cells. J Virol. 1986;59:453–462. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.453-462.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feichtinger H, Li S L, Kaaya E, Putkonen P, Grunewald K, Weyrer K, Bottiger D, Ernberg I, Linde A, Biberfeld G, et al. A monkey model for Epstein Barr virus-associated lymphomagenesis in human acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Exp Med. 1992;176:281–286. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.281. . (Erratum, 176:634.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank A, Andiman W A, Miller G. Epstein-Barr virus and nonhuman primates: natural and experimental infection. Adv Cancer Res. 1976;23:171–201. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franken M, Annis B, Ali A N, Wang F. 5′ coding and regulatory region sequence divergence with conserved function of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A homolog in herpesvirus papio. J Virol. 1995;69:8011–8019. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8011-8019.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franken M, Devergne O, Rosenzweig M, Annis B, Kieff E, Wang F. Comparative analysis identifies conserved tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3 binding sites in the human and simian Epstein-Barr virus oncogene LMP1. J Virol. 1996;70:7819–7826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7819-7826.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gratama J W, Oosterveer M A, Weimar W, Sintnicolaas K, Sizoo W, Bolhuis R L, Ernberg I. Detection of multiple ‘Ebnotypes’ in individual Epstein-Barr virus carriers following lymphocyte transformation by virus derived from peripheral blood and oropharynx. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:85–94. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-1-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammerschmidt W, Sugden B. Genetic analysis of immortalizing functions of Epstein-Barr virus in human B lymphocytes. Nature. 1989;340:393–397. doi: 10.1038/340393a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heller M, Gerber P, Kieff E. Herpesvirus papio DNA is similar in organization to Epstein-Barr virus DNA. J Virol. 1981;37:698–709. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.2.698-709.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heller M, Kieff E. Colinearity between the DNAs of Epstein-Barr virus and herpesvirus papio. J Virol. 1981;37:821–826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.2.821-826.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee Y S, Tanaka A, Lau R Y, Nonoyama M, Rabin H. Comparative studies of herpesvirus papio (baboon herpesvirus) DNA and Epstein-Barr virus DNA. J Gen Virol. 1980;51:245–253. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-2-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling P D, Hayward S D. Contribution of conserved amino acids in mediating the interaction between EBNA2 and CBF1/RBPJκ. J Virol. 1995;69:1944–1950. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1944-1950.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ling P D, Ryon J J, Hayward S D. EBNA-2 of herpesvirus papio diverges significantly from the type A and type B EBNA-2 proteins of Epstein-Barr virus but retains an efficient transactivation domain with a conserved hydrophobic motif. J Virol. 1993;67:2990–3003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.2990-3003.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moghaddam A, Koch J, Annis B, Wang F. Infection of human B lymphocytes with lymphocryptoviruses related to Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1998;72:3205–3212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3205-3212.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moghaddam A, Rosenzweig M, Lee-Parritz D, Annis B, Johnson R P, Wang F. An animal model for acute and persistent Epstein-Barr virus infection. Science. 1997;276:2030–2033. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Peng, R., A. V. Gordadze, E. M. Fuentes Pannana, F. Wang, J. Zong, G. Hayward, J. Tan, and P. D. Ling. Sequence and functional analysis of EBNA-LP and EBNA2 proteins from nonhuman primate lymphocryptoviruses. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Rabin H, Neubauer R H, Hopkins R F, Levy B M. Characterization of lymphoid cell lines established from multiple Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-induced lymphomas in a cotton-topped marmoset. Int J Cancer. 1977;20:44–50. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910200109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rangan S R, Martin L N, Bozelka B E, Wang N, Gormus B J. Epstein-Barr virus-related herpesvirus from a rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) with malignant lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 1986;38:425–432. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910380319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rickinson A B, Young L S, Rowe M. Influence of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA 2 on the growth phenotype of virus-transformed B cells. J Virol. 1987;61:1310–1317. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1310-1317.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowe M, Young L S, Cadwallader K, Petti L, Kieff E, Rickinson A B. Distinction between Epstein-Barr virus type A (EBNA 2A) and type B (EBNA 2B) isolates extends to the EBNA 3 family of nuclear proteins. J Virol. 1989;63:1031–1039. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1031-1039.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sample J, Young L, Martin B, Chatman T, Kieff E, Rickinson A, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus types 1 and 2 differ in their EBNA-3A, EBNA-3B, and EBNA-3C genes. J Virol. 1990;64:4084–4092. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4084-4092.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sculley T B, Apolloni A, Hurren L, Moss D J, Cooper D A. Coinfection with A- and B-type Epstein-Barr virus in human immunodeficiency virus-positive subjects. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:643–648. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.3.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sculley T B, Apolloni A, Stumm R, Moss D J, Mueller-Lantczh N, Misko I S, Cooper D A. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigens 3, 4, and 6 are altered in cell lines containing B-type virus. Virology. 1989;171:401–408. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90608-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sculley T B, Cross S M, Borrow P, Cooper D A. Prevalence of antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2B in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:186–192. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sixbey J W, Shirley P, Chesney P J, Buntin D M, Resnick L. Detection of a second widespread strain of Epstein-Barr virus. Lancet. 1989;ii:761–765. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90829-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walling D M, Clark N M, Markovitz D M, Frank T S, Braun D K, Eisenberg E, Krutchkoff D J, Felix D H, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus coinfection and recombination in non-human immunodeficiency virus-associated oral hairy leukoplakia. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1122–1130. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Wang, F. Unpublished data.

- 30.Yalamanchili R, Harada S, Kieff E. The N-terminal half of EBNA2, except for seven prolines, is not essential for primary B-lymphocyte growth transformation. J Virol. 1996;70:2468–2473. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2468-2473.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao Q Y, Rickinson A B, Epstein M A. Oropharyngeal shedding of infectious Epstein-Barr virus in healthy virus-immune donors. A prospective study. Chin Med J (Engl Ed) 1985;98:191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao Q Y, Rowe M, Martin B, Young L S, Rickinson A B. The Epstein-Barr virus carrier state: dominance of a single growth-transforming isolate in the blood and in the oropharynx of healthy virus carriers. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:1579–1590. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-7-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yates J L, Camiolo S M, Ali S, Ying A. Comparison of the EBNA1 proteins of Epstein-Barr virus and herpesvirus papio in sequence and function. Virology. 1996;222:1–13. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young L, Alfieri C, Hennessy K, Evans H, C O H, Anderson K C, Ritz J, Shapiro R S, Rickinson A, Kieff E, et al. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus transformation-associated genes in tissues of patients with EBV lymphoproliferative disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1080–1085. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910193211604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimber U, Adldinger H K, Lenoir G M, Vuillaume M, Knebel-Doeberitz M V, Laux G, Desgranges C, Wittmann P, Freese U K, Schneider U, et al. Geographical prevalence of two types of Epstein-Barr virus. Virology. 1986;154:56–66. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]