Abstract

Accurate inspection of rebars in Reinforced Concrete (RC) structures is essential and requires careful counting. Deep learning algorithms utilizing object detection can facilitate this process through Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) imagery. However, their effectiveness depends on the availability of large, diverse, and well-labelled datasets. This article details the creation of a dataset specifically for counting rebars using deep learning-based object detection methods. The dataset comprises 874 raw images, divided into three subsets: 524 images for training (60 %), 175 for validation (20 %), and 175 for testing (20 %). To enhance the training data, we applied eight augmentation techniques—brightness, contrast, perspective, rotation, scale, shearing, translation, and blurring—exclusively to the training subset. This resulted in nine distinct datasets: one for each augmentation technique and one combining all techniques in augmentation sets. Expert annotators labelled the dataset in VOC XML format. While this research focuses on rebar counting, the raw dataset can be adapted for other tasks, such as estimating rebar diameter or classifying rebar shapes, by providing the necessary annotations.

Keywords: Rebar inspection, Rebar counting, Unmanned aerial vehicles, Image augmentation, Deep learning, Object detection, Faster R-CNN, YOLO

Specifications Table

| Subject | Civil and Structural Engineering, Artificial Intelligence |

| Specific subject area | Deep Learning-based object detection for rebar counting inspection |

| Type of data | Image |

| Data collection | This dataset was created for rebar counting inspection using object detection with drones. The drones followed a carefully guided vertical path above each column, maintaining an altitude of 1–2 m directly above the rebars to collect raw images. Each image was annotated in VOC XML format. All images are in PNG format with a resolution of 1500 × 900 pixels. The dataset is divided into subsets for training, augmentation, validation, and testing purposes. To increase the amount of training data, eight image augmentation techniques were applied exclusively to the training set. The total size of the dataset is 3.57 GB, and it is provided as a ZIP file. |

| Data source location | Country: South Korea |

| Data accessibility | Repository name: FigShare Data identification number: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23633703.v4 Direct URL to data: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Rebar_counting_detection/23633703 |

| Related research article | The Development of a Rebar-Counting Model for Reinforced Concrete Columns: Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle and Deep-Learning Approach [1] |

1. Values of the Data

-

•

This dataset was constructed for rebar counting inspection on construction sites using unmanned aerial vehicles.

-

•

The lack of labeled data hinders the development of deep learning models for counting rebars, as these data-driven methods require extensive labeled datasets to learn accurately.

-

•

As the entire dataset is labelled, object detection based on deep learning is recommended to develop models such as Faster R-CNN (Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks) and YOLO (You Only Look Once).

-

•

An artificially generated dataset based on real data was also created, which can be used as a benchmark dataset for developing new augmentation techniques.

-

•

In addition to the labelled dataset, the raw data can be used for new tasks such as the estimation of rebar diameter and the classification of rebar shapes.

2. Background

Inspecting the number of rebars in each column of a reinforced concrete (RC) structure is crucial on construction sites [2]. Traditionally, rebar counting has relied on manual inspections conducted by visiting inspectors. However, this method is time-consuming and labor-intensive [3]. As an alternative, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, can be used to efficiently collect images. Object detection models based on deep learning can identify each rebar within a bounding box, allowing for accurate counting by summing these boxes, provided a sufficient dataset is available for training [1]. Despite the potential benefits, accessing construction sites to collect drone images is challenging due to logistical constraints and safety regulations. In addition, there is no publicly available raw and labelled data for counting rebars. This absence of similar datasets in prior research highlights a significant gap, impeding the development of robust deep learning models for rebar inspection. In this article, we provide a rebar dataset sourced from real construction sites to encourage the development of effective techniques for inspecting rebars.

3. Data Description

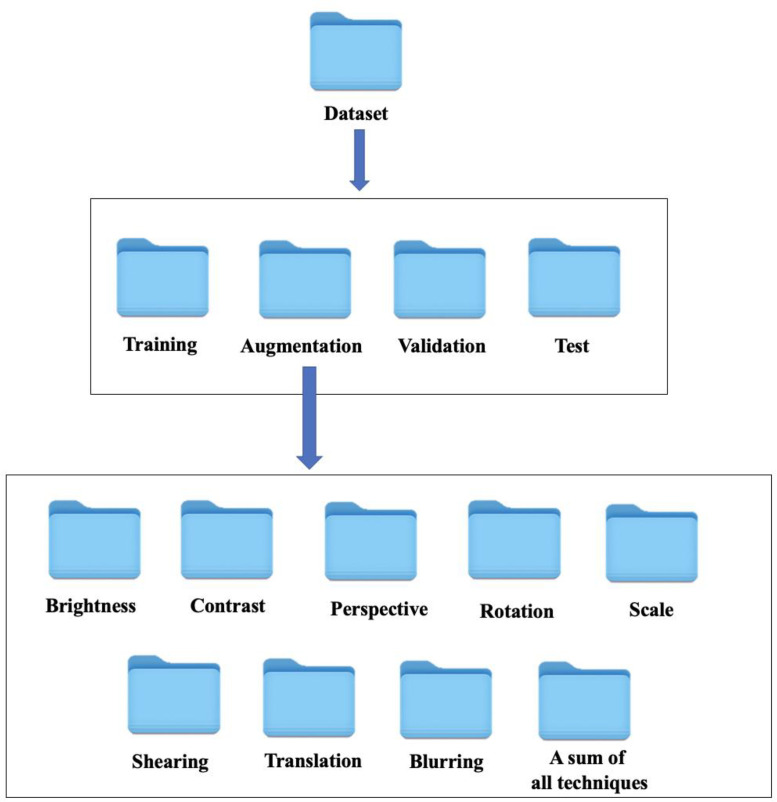

The total size of the dataset is 3.57 GB, provided as a ZIP file. The captured drone images feature centrally framed columns with an ortho angle to ensure the rebars are not overlapped, providing good visibility of the rebars. Each image is annotated in VOC XML format and is in PNG format with a resolution of 1500 × 900 pixels. The constrcuted dataset, designed consists of four different subsets: training, augmentation, validation, and testing. In each folder, images are provided with the corresponding annotation files for object detection. Additionally, the augmentation folder is divided into nine different folders, each corresponding to a specific augmentation technique. Fig. 1 illustrates the organization of the images. Starting with 874 raw images, the dataset was split into three subsets: 524 images for training (60 %), 175 for validation (20 %), and 175 for testing (20 %). Eight augmentation techniques (brightness, contrast, perspective, rotation, scale, shearing, translation, and blurring) were applied exclusively to the training subset, resulting in nine different datasets, including each individual augmentation and a combined dataset using all techniques. In total, 13,974 images were constructed, which include 119,034 rebars. Table 1 below provides a detailed distribution of the datasets based on the rebars.

Fig. 1.

Labeling structure of dataset for rebar counting.

Table 1.

Detailed distribution of datasets for rebar.

| Purpose | Number of images | Number of rebars |

|---|---|---|

| Original training | 524 | 13,226 |

| Original + brightness | 1048 | 26,452 |

| Original + contrast | 1048 | 26,452 |

| Original + perspective | 1048 | 26,452 |

| Original + rotation | 1048 | 26,452 |

| Original + scale | 1048 | 26,452 |

| Original + translation | 1048 | 26,452 |

| Original + shearing | 1048 | 26,452 |

| Original + blurring | 1048 | 26,452 |

| Original + a sum of techniques | 4716 | 119,034 |

| Validation | 175 | 4640 |

| Test | 175 | 4232 |

| Total | 13,974 | 352,748 |

4. Experimental Design, Materials and Methods

4.1. Dataset construction

4.1.1. Use of UAVs for rebar counting

There are several image-based methods for counting rebars, with UAVs being a promising option compared to ground-based robots and stationary cameras. UAVs make the process faster and safer by enabling workers to conduct inspections remotely, avoiding potentially hazardous areas. The speed of UAVs is notable, as they can quickly cover large areas, significantly reducing the time required for inspections.

Despite the advantages of drone-based inspection, there are critical limitations. Operating UAVs on construction sites requires certification from authorities like the FAA or EASA and UAV registration. Flying drones is highly regulated, especially near certain facilities (e.g., military bases and nuclear plants) due to security and safety concerns. Safety measures include pre-flight checks and equipping UAVs with anti-collision lights. Addressing privacy involves informing stakeholders, avoiding sensitive areas, and anonymizing data. Additionally, the quality of photography can be limited; for example, images taken at night may lack proper illumination, and strong winds can cause blurred images due to vibrations. Considering these advantages and limitations, UAVs are most effective for counting rebars in RC columns when the rebars are visible to the naked eye.

4.1.2. Hardware and software requirement

Implementing a UAV-based rebar counting system requires specific hardware and software. The UAV must have a high-resolution camera for detailed imaging, GPS for precise navigation, stability control for steady flights, long battery life for extended coverage, and payload capacity for additional sensors. Software requirements include mission planning tools for automated flight paths, real-time control applications for in-flight adjustments, and image processing software like PyTorch and TensorFlow.

In this study, a DJI Phantom 4 Pro drone was used. Training the deep learning model necessitated a GPU. All experiments were conducted on a Windows 10 system with an Intel Core i7-13700H processor (14 cores, 20 threads), an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 4090 Ti GPU, and 128 GB of RAM. To ensure reproducibility, the complete code is publicly accessible. The dataset, the PyTorch-coded trained model, and the test results can be downloaded from the Figshare data repository referenced here [4].

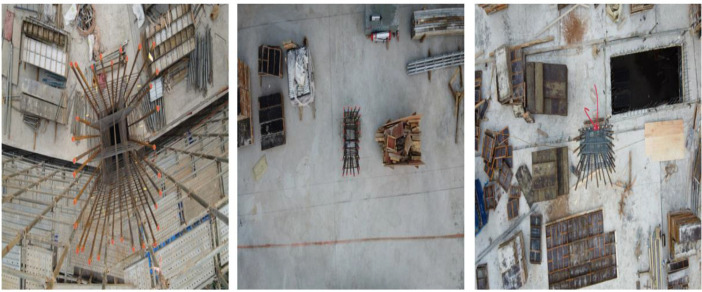

4.1.3. Original dataset preparation

A DJI Phantom 4 Pro drone was deployed at five different construction sites in South Korea during peak productivity hours. Supervisors manually operated the drone to take picture of clear images for counting the rebars. The drone followed a carefully guided vertical path above each column, maintaining an altitude of 1–2 m directly above the rebars. At each designated position, the drone captured still images with the columns centrally framed. To validate the practical applicability, rebar images were obtained under genuine operational conditions, illustrating the complexities of real construction sites. Examples of the original dataset are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Representative samples of original dataset.

In total, 728 images of rebars, each with a resolution of 1500 × 900 pixels, were acquired. The dataset was subsequently divided into two subsets: a training set, and test set. The images were randomly allocated into training (60 %), validation (20 %) and test (20 %) subsets, resulting in 524, and 175, 175 images, respectively, ensuring that each subset accurately represented the original dataset.

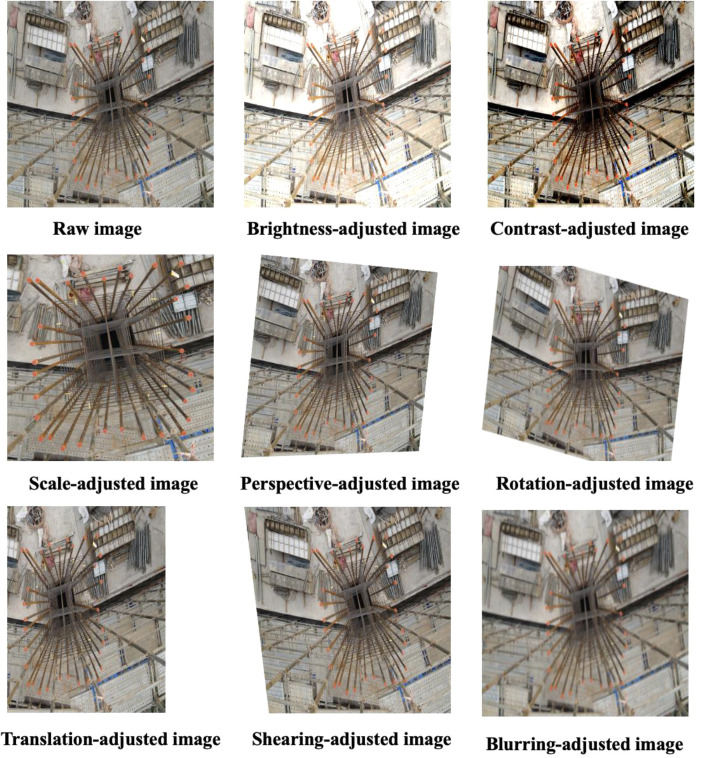

4.1.4. Augmenting the training datasets

Image augmentation techniques, which artificially expand training datasets, were introduced to collect data efficiently without direct filming. These techniques can enhance a modelʼs performance by providing additional features such as non-uniform illumination and scale variance within the existing dataset. When the existing dataset lacks sufficient features, augmentation can improve the modelʼs accuracy. The parameters of image augmentation significantly impact image quality [5]. The dataset and the range of parameters used are presented in Table 2. Detailed mathematical operations of each augmentation technique are described in [6].

Table 2.

Created datasets with ranges of parameters.

| Dataset | Ranges of parameter | Number of images |

|---|---|---|

| Original | – | 524 |

| Brightness | [−30, 30] | 524 |

| Contrast | [0.5, 2.0] | 524 |

| Scale | [x: 0.8, 1.2], [y: 0.8, 1.2] | 524 |

| Perspective | [0.01, 0.15] | 524 |

| Rotation | [−25°, 25°] | 524 |

| Translation | [x: −0.2, 0.2], [y: −0.2, 0.2] | 524 |

| Shearing | [− 15°, 15°] | 524 |

| Blurring | [0.5, 1.5] | 524 |

| Total | – | 4716 |

First, various images of rebars under different lighting conditions were collected. Brightness augmentation was applied to artificially increase or decrease pixel intensity, making images brighter or darker. A pixel intensity ranging from −30 to 30 was randomly added. Second, contrast adjustment was used to enhance the definition of boundaries between rebar and background. The contrast levels were modified by varying the alpha value (α) randomly within a range of 0.5–2.0. Third, scale augmentation addressed variations caused by different UAV flight altitudes. Images were scaled up or down by altering their size along the x and y axes, with transformations ranging from 80 % to 150 % of the original size.

Perspective transformation augmentation accounted for changes in rebar orientation due to different UAV angles. This was done by applying a homography matrix, with perspective changes simulated by adjusting the 'scale' parameter randomly between 0.01 and 0.15 for each image. Furthermore, as the UAV navigates its flight path to capture images of vertical columns, its orientation relative to the columns inevitably changes. Rotation augmentation addresses this variation by rotating the original images by specific angles. In this research, rotation angles were randomly assigned between 5 and 90° to create a more diverse set of rotated images. Horizontal and vertical movements of the UAV shift the position of the rebar within the frame, causing it to appear at different locations in the image, from edges to the center. Translation augmentation shifts the objectʼs position along the x or y-axis, controlled by adjusting and , within a range of −0.2 to +0.2 times the image's dimensions.

The UAVʼs motion and camera angle variations can introduce distortions, leading to a shearing effect, making the rebar appear skewed or slanted. Shearing augmentation, executed within a −15 to +15° range, modifies the parameters and to achieve this effect. To account for blurred images caused by strong winds, the model was trained to recognize objects in blurred images. A Gaussian filter was applied to the original images, creating a more pixelated effect by averaging pixel values in a weighted manner. The Gaussian filter parameter θ ranged from 0 to 1.

For rotation augmentation, an angle parameter θ between −25 and +25° was assigned. Translation was controlled by adjusting and within a range of −0.2 to +0.2 times the image's dimensions. Shearing augmentation was executed within a −15 to +15° range by modifying the parameters and . Examples of original and augmented images are shown in Fig. 3. To evaluate the effectiveness of the augmented datasets, nine distinct datasets were created based on 524 original training images: one original dataset and eight augmented versions (each modified for brightness, contrast, scale, perspective, rotation, translation, shearing, blurring, and a combination of all these techniques).

Fig. 3.

Examples of augmented images in a dataset.

4.1.5. Annotation

The rebar counting process involved annotating the rebars by assigning rectangular ground-truth bounding boxes to each rebar region as the area of interest. In this article, the area of interest for the rebar counting task is considered as the foreground, with each rebar completely covered by the bounding boxes. During this annotation process, the rebars were labelled as ʻrebar,ʼ while all other areas were marked as ʻbackground.ʼ Table 3 provides a detailed distribution of the annotated data across each dataset.

Table 3.

Faster R-CNN for rebar counting in AP50.

| Techniques | ResNet-50 | ResNet-101 | MobileNetV3 | EfficientNetV2 | InceptionV3 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 90.23 | 88.45 | 92.56 | 87.34 | 89.78 | 89.67 |

| Brightness | 91.67 | 94.90 | 93.22 | 90.45 | 92.13 | 92.47 |

| Contrast | 93.01 | 89.67 | 94.56 | 91.23 | 93.45 | 92.38 |

| Perspective | 88.34 | 86.78 | 91.23 | 87.56 | 89.12 | 88.61 |

| Rotation | 89.12 | 87.45 | 90.78 | 88.67 | 90.23 | 89.25 |

| Scale | 92.34 | 88.89 | 93.12 | 90.01 | 91.45 | 91.16 |

| Shearing | 90.45 | 89.34 | 92.67 | 89.78 | 90.56 | 90.56 |

| Translation | 91.01 | 87.90 | 93.45 | 90.12 | 91.23 | 90.34 |

| Blurring | 89.78 | 86.56 | 90.34 | 88.23 | 89.67 | 88.52 |

| Sum of Techniques | 92.34 | 94.59 | 92.78 | 89.45 | 90.89 | 92.01 |

| Average | 90.82 | 89.35 | 92.37 | 89.09 | 91.05 | 90.54 |

4.2. Application example of object detection method

Deep learning-based methods have demonstrated high accuracy in studies related to rebar detection [[7], [8], [9]]. An example application of Faster R-CNN using various deep learning architectures—ResNet-101, ResNet-152, MobileNetV3, EfficientNetV2, and InceptionV3—was conducted.

4.2.1. Evaluation metrics

In object detection, Average Precision (AP) is a widely accepted metric for assessing accuracy. AP quantifies the average precision across all recall values, ranging from 0 to 1, at different Intersection Over Union (IOU) thresholds. Detailed mathematical operations and explanations are provided in [10]. IOU is the ratio of the overlapping area between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth bounding box to the total area occupied by both boxes. AP50 measures the modelʼs ability to detect the presence of rebars with at least 50 % overlap with the ground truth, using this as the IOU threshold. For rebar counting tasks, AP50 ensures that the model correctly recognizes objects.

4.2.2. Result analysis

The analysis, as presented in Table 3 and Fig. 4, shows significant variability in AP50 when different augmentation techniques are applied to each architecture. For ResNet-50, contrast augmentation proved to be the most effective, increasing the AP from 90.23 % to 93.01 %. ResNet-101 benefited the most from brightness augmentation, which boosted the AP from 86.56 % to 94.90 %. MobileNetV3 showed the highest improvement with contrast augmentation, achieving an AP of 94.56 %. EfficientNetV2 also performed best with contrast augmentation, raising its AP from 87.34 % to 91.23 %. InceptionV3 saw the greatest enhancement from contrast augmentation as well, with the AP increasing from 89.12 % to 93.45 %.

Fig. 4.

Graphical results of AP50 in Faster R-CNN.

When all augmentation techniques were applied together, ResNet-50 achieved an AP of 92.34 %, ResNet-101 reached 94.59 %, MobileNetV3 obtained 92.78 %, EfficientNetV2 recorded 89.45 %, and InceptionV3 achieved an AP of 90.89 %. However, the combined augmentation techniques did not result in the highest AP for any of the architectures.

4.2.3. Potential effectiveness of labeled dataset, and model

The research integrates labeled datasets and advanced object detection models into construction site management by training models with labeled data to accurately recognize and count rebars. UAVs collect data, which is processed and synchronized with the Building Information Modeling (BIM) system for real-time updates. The BIM model visualizes current site conditions, including rebar placement and quantity.

Accurate synchronization between the real-world RC columns and the BIM model requires georeferencing and reference points, ensuring precise and reliable integration. This enhances the reliability and accuracy of automated rebar counting, crucial for maintaining construction quality and safety. To improve rebar counting systems, expertise from computer vision, civil engineering, and UAV technology must be integrated. Collaborative efforts in interdisciplinary research, standardizing data formats, user-friendly interfaces, training, regulatory compliance, and continuous feedback will ensure successful implementation.

The potential challenge is to collect a diverse dataset that includes many variations, such as occlusions, shadows, and varying rebar orientations. In this article, we introduced image augmentation, but it may still be vulnerable to background objects like occlusions and shadows, reducing the model's performance in such scenarios. Therefore, more robust augmentation techniques are required, which need to be developed in collaboration with the computer vision field.

Limitations

In deep learning, model success heavily depends on the quality and diversity of training data [[11], [12], [13]]. A major limitation of our dataset is its lack of variation. Although collected from five different construction sites in South Korea, it may not adequately capture challenging conditions like rain or wind. Most images are taken from the center of columns, which works well when the drone is perfectly centered but is less effective with deviations along the x-axis or y-axis. Consequently, models trained on this dataset may struggle with images from significantly different environments.

Another limitation is that the dataset only labels the number of rebars for object detection. Estimating rebar diameter and spacing is also important, but this dataset does not address these aspects. Techniques like semantic segmentation and instance segmentation may be required for these tasks. While our dataset is valuable for rebar counting, it may not fully support comprehensive inspection tasks. This article also aims to determine whether augmentation can improve accuracy in the constructed dataset. For future research and practical model development on real construction sites, advanced model validation techniques such as cross-validation need to be developed.

Ethics Statement

The authors have read and followed the ethical guidelines for publishing in Data in Brief, and they affirm that the present study does not involve human subjects, animal research, or data gathered from social media sites.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Seunghyeon Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ikchul Eum: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Sangkyun Park: Methodology, Investigation. Jaejun Kim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability

References

- 1.Wang S., Kim M., Hae H., Cao M., Kim J. The development of a rebar-counting model for reinforced concrete columns: using an unmanned aerial vehicle and deep-learning approach. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023;149:1–13. doi: 10.1061/JCEMD4.COENG-13686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang Z., Roy K., Uzzaman A., Lim J.B.P. Numerical simulation and proposed design rules of cold-formed stainless steel channels with web holes under interior-one-flange loading. Eng. Struct. 2022;252:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.113566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J., Liu P., Feng L., Wu W., Li D., Chen F. Towards automated clash resolution of reinforcing steel design in reinforced concrete frames via Q-learning and building information modeling. Autom. Constr. 2020;112:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.autcon.2019.103062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S. Rebar counting detection using object detection based on deep learning. Figshare Data Repos. 2023 doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.23633703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang S., Gong Y.H., Wang J.J. The development of deep convolution neural network and its applications on computer vision. Jisuanji Xuebao/Chin. J. Comput. 2019;42:453–482. doi: 10.11897/SP.J.1016.2019.00453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shorten C., Khoshgoftaar T.M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s40537-019-0197-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai Y., Roy K., Fang Z., Raftery G.M., Lim J.B.P. Web crippling resistance of cold-formed steel built-up box sections through experimental testing, numerical simulation and deep learning. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.tws.2023.111190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang Z., Roy K., Ingham J.M., Lim J.B.P. Assessment of end-two-flange web crippling strength of roll-formed aluminium alloy perforated channels by experimental testing, numerical simulation, and deep learning. Eng. Struct. 2022;268:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.114753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang Z., Roy K., Ma Q., Uzzaman A., Lim J.B.P. Application of deep learning method in web crippling strength prediction of cold-formed stainless steel channel sections under end-two-flange loading. Structures. 2021;33:2903–2942. doi: 10.1016/j.istruc.2021.05.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cha Y.J., Choi W., Suh G., Mahmoudkhani S., Büyüköztürk O. Autonomous Structural visual inspection using region-based deep learning for detecting multiple damage types. Comput. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2018 doi: 10.1111/mice.12334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S., Korolija I., Rovas D. CLIMA 2022 Conference. 2022. Impact of traditional augmentation methods on window state detection; pp. 1–8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang Z., Roy K., Chen B., Sham C.W., Hajirasouliha I., Lim J.B.P. Deep learning-based procedure for structural design of cold-formed steel channel sections with edge-stiffened and un-stiffened holes under axial compression. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.tws.2021.108076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy K., Lau H.H., Lim J.B.P. Finite element modelling of back back-to-back built built-up cold cold-formed stainless-steel lipped channels under axial compression. Steel Compos. Struct. 2019 doi: 10.12989/scs.2019.33.1.869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.