Abstract

Background

Changes in Polish demographic data with a growing number of culturally and linguistically diverse patients stipulate new directions in medical education to prepare future physicians to work effectively across cultures. However, little is known about Polish medical students’ willingness to gain cross-cultural knowledge and skills, desire to get engaged in interactions with patients from diverse cultural backgrounds, expectations and needs concerning cross-cultural training as well as challenges they face in the path to cultural competence.

Methods

Therefore, in this study, we conducted and thematically analysed fifteen semi-structured interviews with medical students to broaden our understanding of medical students’ perception of cross-cultural competence enhancement.

Results

The conducted thematic analysis allowed for the development of four themes, which showed that Polish medical students perceived skills and knowledge necessary to facilitate culturally congruent care as indispensable to form quality patient-doctor relations, believed that lack of cultural sensitivity may lead to dangerous stereotype formation and insufficient competence may be the source of stress and anxiety resulting in confusion and lack of confidence. Finally, numerous suggestions have been made by participants on how to improve their cross-cultural competence. Students emphasized, however, the role of medical education with active and experiential learning methods, including simulation-based training, in the process of equipping them with the knowledge and skills necessary to provide best quality care to culturally diverse patients.

Conclusions

Our analysis indicated that Polish medical students seem to hold positive attitudes towards cultural competence development and view it as an important component of physician professionalism.

Keywords: Cultural competence, Cross-cultural competence, Medical students, Medical education

Background

The concept of cultural competence in healthcare is ambiguous and is constantly evolving [1]. Consequently, a great complexity of definitions and theories explaining the nature of the notion has been introduced by various authors. For example, Cross et al. define it as “patterns of human behaviour that includes thoughts, communication, actions, customs, beliefs, values, and institutions of a racial, ethnic, religious, or social group” [2]. Dreachslin et al. state that culture is “the learned and shared knowledge and symbols that specific groups use to interpret their experience of reality and to guide their thinking and behaviour” [3]. Culture determines the way we act, what we believe in, how we work, love and marry, but also how we perceive health, illness and death [3, 4]. Purnell views culture as “the totality of socially transmitted behavioural patterns, arts, beliefs, values, customs, lifeways, and all other products of human work and thought characteristic of a population of people that guide their worldviews and decision-making” [4]. Meanwhile, competency is delineated as the capacity to function effectively and should be viewed as a developmental process [2].

The first term to be used to relate to practices of healthcare professionals to improve the quality of care delivered to culturally diverse groups of patients was multicultural competence, introduced by a psychologist, Paul Pedersen, in 1988 [3]. This was followed by the term cultural competence introduced a year later by Cross et al., seen as a starting point in the understanding and development of cultural competence approaches in healthcare and the basis for numerous interventions aiming at the enhancement of those competencies among healthcare professionals [5, 6]. Cross et al. defined cultural competence as “a set of congruent behaviours, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enables that system, agency, or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations” [2].

According to Dreachslin et al. [3], one of the first steps to developing culturally competent healthcare involves cultural awareness, which allows people to recognize their own distinctive culture and the effect it has on their actions, thoughts, etc. and helps to realize that individuals from other cultures may experience the world differently. In this process of self-reflection and self-examination, the recognition of individual biases and prejudices is emphasised [7]. The next step toward cultural competence involves cultural sensitivity, which recognises the specific cultural needs of individuals as well as the response to those needs in a sympathetic and not resistant manner [3]. Both notions, cultural awareness and cultural sensitivity, express the willingness of healthcare providers to acquire new knowledge and skills [3]. Moreover, M. Tervalon and J. Murray-Garcia advocate the term cultural humility to replace a traditional notion of cultural competence, which is based on a static set of information and skills, stressing the lifelong commitment and an ongoing process of increasing cultural knowledge, self-examination and critique, openness and respectful recognition of cultural differences during active and supportive interactions with diverse patients [8]. The cultural competence training should, therefore, be based on the development of reflection, critical thinking and intuition [9]. Moreover, cultural competence can be seen as an unrealistic goal as acquiring ultimate knowledge is impossible, and thus, cultural humility may provide a better term to conceptualise the process [10]. The difficulties in providing a single definition of cultural competence in healthcare have led to the introduction of many various terms used interchangeably in the literature. Notions such as cross-cultural competence, trans-cultural competence, cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity, cultural safety, cultural humility, cultural responsiveness and cultural congruence, etc., have been put forward, which may indicate the lack of clear definitions in the area.

The above-mentioned theories and the growing interest in global health issues among medical educators have triggered the design and implementation of cultural competence requirements in medical education guidelines, for instance, those introduced over twenty years ago in Tomorrow’s Doctors published by General Medical Council in the UK [11]. As one of the main objectives of cross-cultural education is to reduce racial and ethnic inequalities in health and decrease health disparities [12–16], the document emphasises the demand on medical graduates to show respect towards all patients regardless of their lifestyle, culture, beliefs and race. The ability to maintain successful communication with every individual, whatever their culture, ethnic background or language, is equally stressed [11]. To ensure equal participation in healthcare opportunities, Douglas et al. [12] defined twelve universally applicable standards for culturally competent nursing designed in recognition and responsiveness to the needs of diverse patient populations and advocated suggestions for their implementation in nursing education and practice. The main emphasis of the recommendations is placed on social justice, understanding and inclusion of perspectives and values of diverse individuals, demonstrating culturally competent verbal and non-verbal communication skills and the ability to use resources necessary to meet language needs of diverse patients [12]. Drain et al. [17] defined global health demands on new physicians and developed suggestions for designing global health education, which would integrate into core medical curricula such global health topics as knowledge about tropical diseases, travel medicine and cross-cultural training, including collaboration with interpreters and understanding cultural beliefs.

Although the subject of cross-cultural competence among healthcare professionals has been developed by researchers around the world, especially US, Canada and Australia, for many years, Polish studies showed little interest in that research area mainly due to the demographic homogeneity of our country. The accession of Poland to the European Union in 2004, the measures imposed by the government to facilitate legal employment for labour immigrants [18] and a drastic demographic change after the 24th of February 2022, with millions of Ukrainian refugees fleeing their homes and seeking protection and safety in their neighbouring country, have brought a diversification of the Polish population. The demographic changes of the past two decades, which have been introducing more and more patients with different cultural backgrounds into the Polish healthcare system, urged the policymakers to prepare healthcare professionals to provide culturally congruent care [19]. Medical educators have been, therefore, expected to pay attention to cultural issues and incorporate them into medical curriculum frameworks by designing courses dedicated to providing culturally competent care. The basic standards for medical education in Poland are regulated by the Ordinance of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education on the standards of education for the faculties of: medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, nursing, midwifery, medical analytics, physiotherapy and medical rescue, and stress the importance of including cultural information and language education in the study programmes [19].

Although the issue of cultural competence has been introduced into the context of Polish medical education, and the necessity to equip future health professionals with communication skills that would include aspects of interculturalism has also been emphasised by students [20], there has been little research to determine the expectations of medical students or to characterise the students’ challenges with the attainment of cross-cultural competence. This qualitative study aims to further our understanding of Polish medical students’ perceptions and attitudes regarding cross-cultural competence by comprehensively exploring the following research questions:

What are the attitudes and perceptions of Polish medical students regarding the importance of cross-cultural competence in healthcare and physicians’ profession?

What are their previous experiences and observations in this regard, including the level of the cross-cultural competences among the representatives of the medical profession, personal experiences, and stereotypes prevailing in the society?

What are their views on the need for the enhancement of the level of cross-cultural competences of the members of the medical profession in Poland?

Do Polish medical students feel ready to provide care and interact with a culturally diverse patient, including any potential barriers, impediments, as well as possibilities for and actions taken by them to improve their level of cross-cultural competencies?

Methods

Design of the study and research approach

The study utilizes semi-structured interviews carried out from March to April 2023 with a thematic guide illustrated as an interview outline in Table 1, on a sample of fourth, fifth and sixth-year medical students of Poznan University of Medical Sciences. Students at the later stages of their studies were chosen due to their more extensive experience in interacting with patients and, consequently, potentially deeper insight into the research topic. The participants were invited to the study by the first author via e-mails. The electronic invitations to participate in the study were distributed among all fourth, fifth and sixth-year medical students with the help of class representatives. In order to ensure the diversity of the participant group and not to introduce any restrictions for students willing to participate in the study in terms of demographic factors, including their gender, age, nationality et cetera, the only inclusion criteria adopted in the study were students’ consent to participate in the study and being a medical student of Poznan University of Medical Sciences in one of the three final years of the course. The information about the objectives and scientific character of the study was presented to the students and their consent for the participation was obtained. There was no recompense offered to the students and their participation was voluntary. Moreover, prior to the interviews, the participants were assured of their right to withdraw from the project at any point of its duration and informed that the obtained data would be analysed and subsequently presented and published solely in an anonymized form, making the identification of particular individuals impossible.

Table 1.

The interview outline

| 1. Understanding of the concept of cultural competence – opening question |

| 2. Perception of cultural differences and their impact on human interactions and people’s understanding of health and disease |

| 3. Evaluation of the organization and quality of care delivered to culturally diverse patients in Poland |

| 4. Recognition of stereotypes present in Polish society, including those appearing in medical environment |

| 5. Personal experiences of interactions with people from diverse cultures (types, frequency, encountered difficulties, associated emotions) |

| 6. Personal experiences of encounters with culturally diverse patients (participants, challenges, etc.) |

| 7. Assessment of the cultural competence of Polish physicians |

| 8. Recognition of the need and methods to enhance cultural competences of Polish physicians and consequences of its development |

| 9. Major impediments to respondents’ cultural competences |

| 10. Respondent’s readiness to engage in cross-cultural interactions with patients |

| 11. Evaluation of the possibilities of developing respondents’ cross-cultural competence offered in the course of medical training |

| 12. Respondents’ efforts to strengthen cultural competence |

| 13. Further issues that respondents wished to add to the topic – closing question |

The interviews were carried out by the first author using the MS Teams application at the time chosen by the participants to adapt to their convenience. After the interviews, the recorded data were transcribed, supplemented with the demographic characteristic of the participants (gender, age and study year) and encoded to secure the anonymity of the respondents. The analysis process continued in the coded form. The data were thematically analysed by the first author following Braun and Clarke’s method [21–26]. The analysis process focused on semantic and latent elements of the data, the latter going beyond surface meaning or descriptive character of the data and contributing to the interpretative character of the study [24]. The inductive or data-driven orientation to coding was undertaken in which data are not coded to fit a specified coding frame and themes develop from codes in the course of analytic and interpretative study [23, 25]. The analysis was conducted following the six steps described by Braun and Clarke [23]. The first step involved familiarization with the data, which entailed reading and re-reading the transcribed interviews in order to identify information relevant to the research question. Next, the process of coding was undertaken. A code is “conceptualized as an analytic unit or tool, used by researchers to develop (initial) themes” [22]. Phase three involved reviewing and analysing meanings conveyed by different codes and collating them into themes. Then, the themes were reviewed in terms of coherence, patterns and relation to the data and the research question. In the next step, the themes were refined, defined and named and relevant data were identified to be used as extracts to provide the illustrations for the themes. Lastly, a final report of the analysis was produced. During the data analysing process, the first author also continuously consulted and discussed her findings with other authors, including the proposed themes, quotations extracts and a draft of the final report, the goal of which was to exchange views and opinions to gain deeper comprehension and perception of the data rather than reach a consensus, since, as it should be mentioned, the authors of the form of thematic analysis that we employed in the study bring attention to the incoherence of their research method with practices like, e.g. intercoder agreement [24]. In total, 15 semi-structured interviews were carried out with 12 female and 3 male students. The sample comprised 2 fourth-year, 6 fifth-year and 7 sixth-year medical students aged 23–26. The average duration time of the interviews was approximately 41 min. All the study participants were of Polish nationality.

Ethical considerations

The protocol of this study was presented to the Bioethics Committee of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences, which confirmed that their approval was not legally required for the present research to be conducted (Decision No. KB – 915/22). Prior to each interview, the respondents were informed about the objectives and the scientific character of the study as well as their voluntary participation. The respondents’ confidentiality was maintained throughout the entire research process, from data collection to their publication.

Results

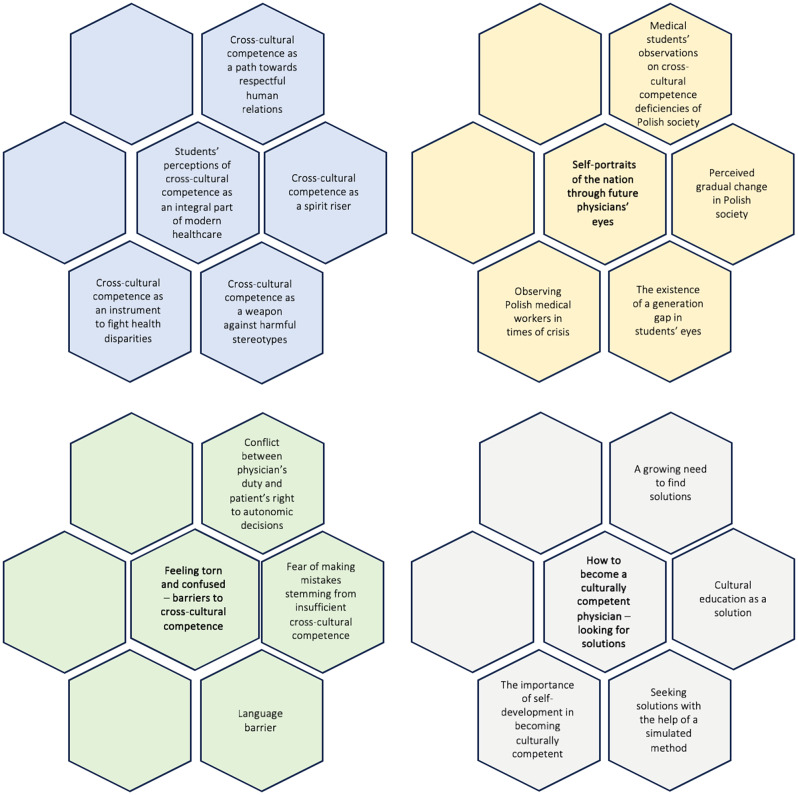

In the course of thematic analysis, we developed four themes to capture medical students’ narratives of their attitudes towards cross-cultural competence enhancement. They were presented below and are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Four themes developed in the course of the study with their main findings

Theme 1: students’ perceptions of cross-cultural competence as an integral part of modern healthcare

The first theme describes students’ understanding of cross-cultural competence and their perception of the significance of having the knowledge and skills necessary to communicate with people coming from different cultural backgrounds. The main idea behind this theme was to capture medical students’ positive attitudes toward the importance of cross-cultural competence among healthcare team members and their evaluation of outcomes and consequences of both successful as well as ineffective communication with people across cultures.

Cross-cultural competence as a path towards respectful human relations

For the majority of participants, the main aspect of cultural competence was the ability to show respect towards diverse traditions, beliefs, norms of behaviour, views of the world, perspectives, etc. For many students, a person’s faith constituted the most important determinant of culture. The majority of respondents saw cultural competence as a set of skills and abilities such as expressing understanding, empathy, awareness and willingness to learn about other cultures and differences among them.

S7 “To be culturally competent is to know how to behave in the company of people from a different cultural background than ours. It is the ability to respect their values and faith.”

S12 “Cultural competence enables collaboration and action regardless of the culture we come from.”

Cross-cultural competence as a spirit riser

Interviewed medical students stressed how being positive and open-minded towards other nations helped to establish culturally competent relations in the course of regardful communication and how this, in turn, enabled them to positively experience the world.

S12 “ I believe that if we have good intentions, and I always have them, so no matter what cultures we represent, we will always communicate and understand each other.”

S8 “Cultural differences bring me the opportunity to gain new experience and see different perspectives and are a great way to learn about the world.”

Cross-cultural competence as a weapon against harmful stereotypes

Accounts within this theme often referred to the observation that a lack of awareness of differences among cultures and unwillingness to acquire knowledge and understanding about them may result in dangerous stereotype formation and hostility. The notion of destroying the ground for harmful stereotypes by gaining knowledge and skills and acknowledging the equality of cultures and traditions was highly appreciated by respondents.

S1 “The biggest problem is the lack of understanding of different customs, distinct cultures, because it may give rise to disagreements.”

S13 “Building relations with patients based only on what we think we know without having actual knowledge may lead to the creation of stereotypes.”

Cross-cultural competence as an instrument to fight health disparities

For some respondents cultural knowledge and skills were necessary for a doctor to provide care for diverse patients and to develop successful collaboration with medical staff from distinct cultural backgrounds. They believed respectful communication with patients, regardless of their background, should set the ground for a favourable social environment in healthcare.

S9 “As future doctors we must be vigilant about the cultural background and upbringing of our patients (…). We should be able to understand patients’ perspective so that everyone feels respected.”

Theme 2: self-portraits of the nation through future physicians’ eyes

The next theme developed in this study relates to students’ perception of Polish society. Different views on the cultural competence of Polish people, including Polish physicians, were presented in the interviews and contrasting portraits of the country were drawn, which we tried to reflect by the use of the plural in the name of the theme. The most eminent observation, however, was the presentation of Poland as a country of change, with the difference in attitudes and behaviours towards diversity mainly noticeable among the younger generation and in bigger cities.

Medical students’ observations on cross-cultural competence deficiencies of Polish society

In one of the portraits, the communication skills of doctors were presented as rather poor and their awareness of differences and willingness to learn about other cultures as insufficient. Students reflected that due to their unfamiliarity with cultural sensitivity and inadequate communication skills, many physicians are not ready to engage in cross-cultural interactions.

S1 “I’ve heard a lot of unsuitable comments made by doctors towards students. I don’t think this cultural sensitivity is something some doctors are familiar with.”

In this portrait, respondents depicted Poland as an ethnically, culturally and religiously homogenous nation with tendencies for dislike and prejudice against people who are in some way different or come from other countries.

S9 “Our system does not assume differences. We are supposed to build a particular society where only heteronormative couples live and form multi-child families. We are supposed to be happy, have a garden, a dog and a few children (…), attend the church on Sundays, of one correct denomination.”

What is more, as one respondent remarked, many recent political decisions contributed to the negative picture of Poland.

S12 “The last political decisions related to abortion, approach to homosexual couples, transgender people, etc. create a bad image of Poland in the world.”

Medical students participating in the study would observe that patients of Polish hospitals are given the opportunity to access prayers, sacraments and other religious practices. However, some students were under the impression that those practices were mostly confined to only one dominating religion.

S7 “There is only a catholic chapel and a catholic priest in a Polish hospital. People of different faiths are denied access to such facilities.”

On the other hand, this view was not shared by some other respondents, who provided first-hand accounts of witnessed instances in which the spiritual care of their affirmed faith was offered to the patients, as evidenced by the example below, introducing a depiction of a different picture of Poland.

S9 “I have some positive experience from Palium Hospice in Poznan (…) where they asked an imam to accompany the dying patient and perform the prayers and rituals according to the Muslim traditions (…).”

Perceived gradual change in Polish society

Other students added to this different picture of Poland, illustrating a change occurring in the society imposed by the increasing population diversification due to migration, and presented descriptions of a more tolerant and open-minded society, where physicians are adequately prepared to provide culturally competent healthcare, engaging with patients coming from a wide range of cultural backgrounds. In this portrait, students described doctors who recognize and respect patients’ preferences, values and traditions, diversities of lifestyles and perspectives.

S9 “Polish society is changing. We are slowly opening up to other cultures. We are becoming a big economy, and consequently, more and more international people are becoming a part of this economy.”

S8 “I think the doctors who I’ve met in our hospitals are well prepared to work with a foreign patient. I’ve never witnessed any negative attitude (…). I see physicians as a group of people who respect diversity and, (…), try to approach everybody with equal attentiveness and understanding.”

The existence of a generation gap in students’ eyes

Some participants would also acknowledge that the younger generation of physicians seems more prone to accept these changes and implement some improvements. This was seen as a consequence of promoting a patient-centred care approach among younger doctors and the modifications introduced in medical education, where more emphasis on communication and interpersonal skills is being placed these days. An interesting account of the changes in education is presented below.

S7 “We (medical students) are taught a different approach to a patient. We should focus on a patient’s comfort and needs. During classes, we practice communication skills, paying attention to such details as eye contact, for example (…).”

According to the respondents, some of the differences between the younger and older generation of physicians may also still be the consequence of the communist era, which strived to eliminate any form of diversity, strongly supporting the image of a mono-ethnic society.

S5 “It is possible that a younger generation of doctors, who has more possibilities to acquire cross-cultural skills, is better prepared to work with a culturally diverse patient. This relates to education during the communist era. Now we can travel around the world and get to know it. (…). The generation of our parents is the lost generation.”

Moreover, the ideological and economic changes that Poland witnessed after the collapse of the communist regime, along with the influence of mass media and the internet, resulted in the growing acceptance of cultural varieties in Polish society. The differences in the speed and extent of adaptation to those transformations were still observed between the regions of Poland, the size of towns, the types of hospitals doctors work in and also the area of medicine they specialize in.

S13 “Most people of my age have a different attitude than people who are older than me. (…) we were just brought up in a different way. My generation has practically unlimited access to other cultures (…). The younger generation is more open-minded, has a bigger knowledge about different cultures, is more liberal (…), the generation of older doctors might be less accepting towards cultural diversities.”

Observing Polish medical workers in times of crisis

The outbreak of war in neighbouring Ukraine has contributed to the creation of one more portrait of Poland – a country where immediate actions are taken to meet new arising needs. The radical change in the migration situation in Poland caught Polish people, and among them health professionals, completely off guard, as evidenced in the following utterance:

S5 “We were not prepared to provide care to Ukrainian patients. It was just a matter of having no other choice than to act.”

According to respondents, doctors and other healthcare workers had to find their own ways to help the numerous patients arriving from Ukraine. This entailed overcoming plentiful difficulties such as language barriers in communication and medical documentation, procedural differences, variations in medicine classification and vaccination schedules, etc. As it was very uncommon for hospitals to supply enough interpreters to meet the enormous linguistic demands, the language barrier became a real struggle. Although Ukrainian language helplines were created, they were not efficient enough. The medical staff fell back on internet translating applications, started searching for people speaking Ukrainian language among hospital medical staff, medical students and patients’ family members, who often volunteered to help with communication. The accounts of physicians’ confrontation with the linguistic barrier can be traced in the below-mentioned quote.

S10 “We had a really terrible time trying to communicate with patients coming from Ukraine. We all had to rely on such helps as google translate. We would be lucky to have an interpreter as they weren’t available round the clock as we needed them. (…). We often had to rely on the help of a family member who knew at least a little Polish (…)”.

As reported by students, translating documents and distributing medical information materials in the Ukrainian language among patients had become a common practice, which greatly facilitated communication and enhanced care. Many problems resulting from the distinct rules relating to units of measurement operating in both countries, for example, were avoided.

S2 “Various materials were created for Ukrainian patients. In diabetology, for example, we made those leaflets for the patients where we gave them the doses in millimoles and not in milligrams as it is presented in Poland. We had to be aware of those differences because otherwise, the patients would not be able to understand the dosage.”

Many respondents went on to reflect that physicians were faced with systemic differences that existed between Polish and Ukrainian healthcare system organization, dissimilarities in children vaccination schedules and medicine classifications, lack of health records for chronic disease patients or medical documentation written in Cyrillic script and, above all, the feelings of confusion, fear and helplessness experienced by the people fleeing the war.

S2 “The medical documents (the Ukrainian patients had) were written in Cyrillic script and it was hard for Polish doctors to obtain any medical information from them.”

S14 “Patients from Ukraine seemed less organized and it was not caused by their negative attitude or anything like that but by the fact they came here in total chaos. They didn’t take their medical files with them, had no CDs with previous MRI scans. It wasn’t just anything they would think about at that time (…). And our doctors needed to be patient and understanding and know that our health care system might work a bit differently than the Ukrainian one.”

Finally, the involvement of Polish medical workers in helping the refugees was driven by spontaneous solidarity and far exceeded the medical sphere. The support towards Ukrainian citizens gave rise to a very positive portrait of the nation, which is evidenced by the example below.

S15 “I saw a tremendous engagement of our oncologists (…) and not only medicine-related (…). We were collecting food and clothes but also helped to organize housing for the patients and their families. I helped to arrange clothing, packed the clothes and distributed them to the people who needed them. We all did it in our university.”

Theme 3: feeling torn and confused - barriers to cross-cultural communication

The third theme captures conflicts and dilemmas, often resulting from fear and anxiety, physicians may come across during culturally diverse encounters as well as linguistic barriers, which, in turn, may fuel the feelings of apprehension and reluctance to engage in interactions with patients from distinct cultural backgrounds. Doctors may feel distracted by conflicting moral and ethical choices and their confusion may be exacerbated by the fear of legal consequences of their actions. Moreover, although they often undertake earnest efforts to become culturally competent physicians, their lack of sufficient knowledge about cultural beliefs and values expressed by the patients and inadequate awareness of certain verbal and non-verbal behaviour differences may leave them feeling torn between what they strive for and what they achieve.

Conflict between a physician’s duty and a patient’s right to autonomic decisions

As pointed out by respondents, the feelings of being torn were often associated with the conflict that sometimes arises between a physician’s duty to preserve life and the right of freedom of thought, belief and religion of an autonomic individual. Students gave accounts of their difficulties in accepting patients’ health and treatment choices or refusal of procedures, especially those which, according to their medical knowledge, serve in the best interest of their patients and often result in saving their lives. Respondents also referred to the conflicting opinions concerning such issues as termination of pregnancy, fertility treatment or gender interaction rules.

S5 “The thing I’d be worried about would be my patient’s refusal of treatment, especially if the treatment was the only option available. To be honest, this would be my nightmare, especially if it was a child whose family would reject the treatment because it would conflict with their religious principles or cultural values (…).

A commonly referenced religious group in this aspect were Jehovah’s Witnesses (JWs), who, as reported by respondents, constitute a visible congregation in a relatively nationally and religiously uniform state and whose religious teaching affecting health decisions are often called attention to in the course of medical education. Therefore, many students’ concerns were related to the fear of legal consequences of providing care for JWs patients, who believe certain medical procedures are contrary to Biblical teaching and reject them on this ground. Participants’ accounts emphasize the conflict between the Hippocratic oath and the patients’ right to reject life-saving procedures, which seemed especially disturbing in the case of children patients. Students’ worries concerning the choices to be made while looking after those patients are evidenced by the following example.

S3 “There was this young patient with a chronic disease who needed surgery but refused the procedure as taking blood and its primary components was contrary to his religious teaching (…) and the patient died. I heard the frustration in the clinician’s account of this story and sadness, too. They had a chance to save this patient.”

Fear of making mistakes stemming from an insufficient cross-cultural competence

Participants’ accounts also revealed the discrepancy that arises between their desire to act as culturally competent individuals and the fear of misapprehension, misreading and embarrassment that may result from their lack of knowledge about culturally defined norms of behaviour, lifeways, patterns of verbal and non-verbal communication, etc. The cultural aspects most often referred to as confusing for students were gestures, touching, clothing, meal times, asking questions, expressing gratitude, communication styles and gender-related issues. The lack of understanding and the paucity of knowledge of those elements of culture might leave respondents perplexed and incapable of conducting a successful communication because, as one person (S13) noted, ‘if you don’t have knowledge and experience, it’s very easy to make a faux pas”; this may, in turn, affect their confidence and performance as doctors.

S2 “If I had a patient from an Arabic country, I’d be a little afraid if I did everything right (…) I would think that maybe I shouldn’t do something because it’s forbidden in their culture. I might not know which part of the body I’m allowed to touch, etc. (…). I’d be afraid of pushing (…) those cultural boundaries I might not know about”.

However, as evidenced by a captivating account below, this feeling of confusion felt by the students does not seem to be strictly limited to the medical profession. In their accounts, students also shared some private experiences when they also felt the aforementioned paradoxical contrast between their wish to behave in a culturally competent way and the moments when their insufficient cultural knowledge left them unsure of what was happening and why the other person behaved in a given manner, which seemed to impair their overall sense of competence.

S11 “We went bowling once with a group of Asian friends. When our team lost the game, the Asian team started apologizing to us for their victory. In my country, when somebody loses, they just lose and simply congratulate the winners (…). We didn’t know how to react to their behaviour (…), it was confusing to all of us.”

Language barrier

Some respondents regarded the command of a language as the primary constituent of cross-cultural competence that in itself warrants the development of successful communication and, consequently, a promising diagnostic and therapeutic process. Language seems to occupy a uniquely crucial space in medical communication and some students viewed the knowledge of patients’ language as more important than the familiarity with such aspects of culture as religious beliefs and practices, social interactions and rules, etc.

S5 “A language barrier poses the biggest problem to our physicians. If you don’t know something about a particular culture, you will ask to have it explained to you, but if there is a linguistic barrier (…), you might have a problem overcoming it.”

Theme 4: how to become a culturally competent physician – looking for solutions

The identified needs have urged medical students to search for solutions and find ways to interact effectively with people across cultures. The last theme, therefore, encompasses respondents’ accounts of various attempts that have been made to improve skills, knowledge and attitudes necessary for engaging with culturally diverse individuals. Many participants would acknowledge, for example, that travelling helped them improve their competencies. Others would stress interactions with real patients during their clinical practice. One of the most commonly reported solutions, however, was cultural education, which was perceived as a valuable investment in the future role of a culturally competent physician. Students’ accounts emphasize that the amount of time devoted to culturally congruent care training during their medical course was insufficient and, therefore, a demand to intensify this area of education was made.

A growing need to find solutions

In view of the population changes Poland has experienced in the last decades, some students would emphasize the necessity to find solutions to become culturally aware and sensitive to care for the needs of all people living in their transforming country, pointing out that not enough attention is given to the issues of cross-cultural care in Poland.

S5 “Looking at what’s currently happening around the world, we are going to have more and more patients from different countries and cultures. For practical reasons, we need to do it (enhance cultural competence).”

Sharing their experiences gained during travelling or participation in various exchange programmes, students wished that the culturally competent behaviours and attitudes noticed abroad were also present in their country. Openness towards ethnical, religious and cultural equality, diversity and inclusion, and treating every patient with respect, etc., observed abroad, were enthusiastically emphasized by respondents, which may indicate their longing for achieving a similar level of competence and could constitute a drive to find ways to obtain similar qualities. Many participants made statements parallel to the following one:

S8 “I met people from all over the world in Sweden. They were all so different from each other in terms of religion, skin colour, etc. (…). In Sweden, despite this huge diversity, people didn’t judge each other (…), everyone was equally respected.”

Cultural education as a solution

One of the solutions to increase cultural competence was recognized in education. As the idea behind successful and effective education is based on the eagerness and readiness of the learner to learn, students emphasized the importance of medical students’ and physicians’ willingness to acquire knowledge about distinct cultures and develop their skills and competencies in this regard.

S15 “No course will be able to change anything if doctors are not willing to develop those competencies.”

Furthermore, some respondents observed that the lack of enthusiasm for developing cultural competence might stem from indifference and the conviction that cultural communication skills were of lesser importance than medical knowledge and skills. The comment presented below may serve as a good illustration of this opinion.

S12 “Not everyone is interested (…). For many of my friends, it would be a waste of time. Medical students are often, in my opinion, not open to things other than medicine (…), such skills as communication, psychology or multiculturalism do not matter to many (…).”

In addition to the poor enthusiasm, some participants would report the lack of time as the aspect that might impede the educational process. This often results from the work overload of clinicians due to hospital staff shortages as well as the overload of the medical school curriculum.

S10 “I can see one major obstacle here and this is the lack of time. (…) it would be lovely to expand one’s interests, acquire knowledge, learn languages (…). It seems so unrealistic, especially when you realize you still have to expand your medical knowledge and skills at the same time.”

Multicultural training carried out as an elective course or incorporated into the already existing classes was seen as the way to overcome the hardship of a medical curriculum overload. Another suggestion, which one student (S9) referred to as “such an easy solution”, was a joint course arranged for both Polish and the English Division programme students at our university. Furthermore, the lack of collaboration between the two student groups was perceived as a considerable loss of cultural competence training possibilities and a great disappointment with the university organization.

S8 “I know it’s hard to accommodate a course about cultures or classes on how to care for foreign patients into the busy medical syllabus. But maybe they could be offered as electives.”

S14 “ We have English Division students from all over the world here. It would be a great idea to do some joint elective classes (…). They could learn a lot about us because, despite living in Poland, they have very little opportunity to interact with the Polish people (…). Polish students could benefit a lot too, as far as cultural knowledge and the language are concerned.”

Not all respondents were in favour of multicultural classes as elective courses for volunteers. Some declared that only compulsory training could guarantee an increase in individual engagement and motivation to learn. The electiveness of the class might result in lower attendance as some students may doubt the effectiveness of the course and consider it less important than basic science classes.

S9 “We mustn’t expect everyone will be willing to learn (…). I know many students who are not serious about such classes (…). I talked to a friend about it and he believes that all subjects like psychology, communication, etc. are a waste of time because we should be learning practical medicine and everyone knows how to talk, so there is no point learning about it. ”

Some respondents referred to the flaws in the Polish education system, which has been inattentive to multicultural issues at any of its levels. For example, one participant noted:

S3 “I wish we had courses teaching about different cultures in the earliest stages of education. I’m thinking of primary and secondary schools. We tend to teach children about different countries in terms of geography but not in terms of cultures.”

According to respondents, medical education has been equally inattentive to the multicultural needs of future physicians as medical students receive hardly any instructions on how to provide care to culturally diverse patients. The majority of participants reported that the courses would allow for better communication with foreign patients, who are becoming more and more common in Polish hospitals and would help doctors avoid making mistakes.

S7 “I’m finishing my medical course next year and I’m going to start working in a hospital and I have never been taught how to provide care to a patient from a different culture. There was not even a single elective course that would introduce the subject of cultural differences (…).”

Students valued the medical English course offered to them during the first years of their studies but pointed out the insufficient number of classes.

S10 “The only course devoted to cross-cultural education was English in Medicine. I don’t even recall any classes with SPs (Simulated Patients), not even one class with a patient who would at least not be able to speak Polish.”

Seeking solutions with the help of a simulated method

Next, a great appreciation towards communication classes with Simulated Patients (SPs) held in the university simulation centre was expressed by respondents. Their accounts emphasize that the simulated method allows for communication with a patient in a safe environment without putting a real patient at risk of feeling intimidated by the presence of students and, most importantly, enables students to get actively involved in a communication process. Most students regarded simulation classes as a perfect setting for introducing cultural competence education elements.

S6 “It would be worth having such classes, let’s say in the simulation centre (…). We could introduce four patients from different cultures (…). For instance, most needed at this moment: a Ukrainian patient, a patient only speaking English, someone with a different skin colour and somebody who speaks neither Polish nor English. (…). We would be better prepared to deal with similar situations in real life.”

Students went on to reflect that not much deliberate effort was needed to design cross-cultural classes with SPs as only minor modifications to the existing scenarios were considered necessary. Attempts to design culturally tailored health interventions with SPs were also made.

S1 “If we have a scenario depicting a stomach ache, why don’t we introduce some cultural elements into it? (…), the existing scenarios could be used (…)”.

The importance of self-development in becoming culturally competent

Accounts within this theme often implied that the majority of information, skills and cultural and linguistic knowledge were obtained in the process of students’ self-study and self-development. Although multicultural knowledge was introduced at university, it was described as scarce and limited. The idea was frequently evoked, for example:

S13 “We don’t learn about cultural differences in medicine. In epidemiology, there was a short reference to some disorders typical for people of Asian or African origins (…). It was very scarce, though (…).”

Future doctors recognised the importance of learning through travelling, taking part in various student exchange programmes, using international study materials, acquiring information from the internet or practicing communication with real patients in hospitals.

S12 “I don’t think my university prepared me to function in a multilingual healthcare environment. I just did a lot of reading on my own; I was a member of a few student organizations where we talked about such issues.”

S9 “I travel a lot. I go to conferences. I was in Slovenia as an Erasmus exchange student. I was also very lucky to have grown up in a family with parents who paid a lot of attention to showing us the world.”

In their attempt to find solutions to increase their cultural competence, one student would acknowledge taking up Ukrainian language lessons to deal with the linguistic barrier following the outbreak of war in Ukraine. As reported here, language education was completely voluntary and the course syllabus was exclusively designed by the learner. Here is the account of the student’s struggle with the new language:

S4 “I’m learning Ukrainian in order to communicate with those patients (…). I started with the alphabet on Duolingo (…). Then I continued with some basic expressions (…), took part in a course on the internet (…). I watched some free channels on YouTube (…). I listened to podcasts, songs and watched films on Instagram (…).”

Discussion

The study aimed to characterize medical students’ perception of the importance of cultural competence learning for successful engagement in cross-cultural interactions with their future patients, the main barriers they may experience when trying to reach the competence and the attempts to overcome the obstacles. According to the study results, medical students perceived the ability to provide culturally congruent care as a significant aspect of their job as physicians, with the lack of knowledge and skills as a crucial factor impeding the provision of quality healthcare. Furthermore, the study revealed the main factors that may hinder students from becoming culturally competent physicians and the solutions to overcome the constraints.

Our analysis reveals that students’ understanding of culture and cultural competence varied, which seems consistent with the discrepancies observed in the literature and numerous definitions put forward to explain the terms [2–4, 6]. Respect for different traditions and non-judgemental openness to each individual, regardless of their cultural background, was emphasised by the majority of respondents. Participants’ opinions concerning the role of cultural competence in delivering appropriate health care to patients from diverse backgrounds and cultural beliefs and its significance in reducing health disparities also remained harmonious with the research on the subject [27–30]. Inadequate cultural competence, on the other hand, which students mostly viewed as the lack of acceptance and understanding for differences, unwillingness to learn and interact with culturally diverse people and, most of all, regarding and presenting their own worldviews, traditions and values as superior to those of other people, was identified as the ground for the formation of hurtful stereotypes, the source of disputes and even acts of violence. Moreover, some participants highlighted the importance of language proficiency in responding to the needs of diverse populations. In fact, linguistic incompetence contributes to the decrease in patients’ satisfaction and compliance with the treatment; it may also be the cause of misdiagnosis and the reason for patients’ refusal to seek treatment and has been, therefore, identified as one of the main access barriers to health care [30–35]. As one study on Latino children in U. S. concluded, more than one in four parents identified linguistic problem as the single greatest obstacle to getting health care for their children [32]. García-Izquierdo et al. [30]. emphasized the need to create policies that would reduce linguistic barriers to patient care to minimize the risk of detrimental health consequences but recognized the social and cultural needs of patients as equally important to effectively deliver health services to all patients. In our study, some respondents perceived linguistic competence as superior to other elements of cultural competence, such as knowledge about religious beliefs, familiarity with social interactions, rules of verbal and non-verbal behaviour, etc. Respondents’ accounts of the struggle with the linguistic barrier they encountered after the unanticipated influx of Ukrainian war refugees also emphasize the significance of language skills in providing appropriate services and promoting treatment adherence. Furthermore, analysing their educational needs, some participants would indicate taking language lessons as the single way to enhance cultural competence. However, it should be emphasized that not all communication problems in health care can be related to the language barrier and many are, in fact, attributable to the insufficient capacity to identify, understand and respect the values and beliefs of patients and to the lack of recognition that culture determines the way they perceive health and illness, influences how symptoms are recognised and described and what treatment options are preferable. Although language plays a vital role in patient-doctor interactions, by regarding linguistic competence as the only aspect of cultural competence and discrediting the magnitude of other constructs, participants may fail to notice individual patients’ needs, decreasing their chances of establishing respectful and accepting relations with diverse patients. Anderson et al. [28]. emphasise that culturally competent health care system should provide both culturally and linguistically appropriate services and recognise linguistic barriers as structural barriers to cross-cultural communication. In fact, to become a culturally competent individual, which can only happen during a life-time continuous process, one needs to acquire cultural knowledge, skills, awareness of the recognition of own biases and prejudices and a desire to engage in cross-cultural interactions with culturally diverse patients [7]. Cultural knowledge, which also includes knowledge of interpretation services, assessment of linguistic needs of a patient, etc., involves obtaining information about cultural and ethnic groups, health-related beliefs, disease incidence and prevalence, the manifestation of diseases among ethnic groups, treatment outcomes related to ethnic origin, socioeconomic factors, etc. [7, 28, 36–38].

Participants’ assessment of the level of cultural competence skills of Polish society, including their perception of various imperfections and struggles for improvement carried on by many Polish people, highlights medical students’ sensitivity, responsibility and concern over the subject. The demographic changes, the ideological and economic transformation following the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, and the effects of mass media and the internet on the formation of opinions, beliefs, and habits of life have all contributed to a greater openness of Polish society. Although Poland has been receiving many economic immigrants over the last decades, the possibility of engaging in multicultural interactions with foreign patients has vastly increased with the humanitarian crisis in Ukraine, which has forced many Ukrainian citizens to find protection in Poland. According to the statistics presented in January 2023 by the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, there were nearly 8 million refugees from Ukraine recorded across Europe, with over 1.5 million registered in Poland out of almost 9 million crossing the Ukrainian-Polish border between February 2022 and April 2023 [39]. Students’ accounts of the situation faced by Polish healthcare workers after the Russian invasion of Ukraine highlight the enormous engagement and persistence of medical staff in overcoming numerous obstacles when providing care to patients speaking a different language, complying with incompatible organizational and administrative rules, presenting distinct treatment expectations and, above all, often requiring immediate psychological and emotional support. The experiences of participants in our study correspond with the empathy expressed by Polish healthcare professionals and the willingness to deliver help, not only limited to strictly medical aspects, which was the shared experience of the whole country, as Domaradzki et al. remarked: “as never before, Poland has seen mass mobilizations of thousands of ordinary people and a true explosion of citizens’ commitment to the cause of the refugees” [40]. Despite the high level of cultural sensitivity expressed towards the war refugees, according to students, some Polish physicians still tend to demonstrate insufficient skills in cultural competence, causing them to pass judgement, disrespect and discriminate against patients. The difference in the level of cultural competence was especially noticed by students between the young and old generation of doctors, with the latter being also reported to show bigger deficits in communication skills. The existence of a similar student-perceived generation gap between groups of Polish physicians stipulated by the accounts of participants has also been demonstrated in recent research on medical students’ intentions towards interprofessional collaboration, with younger physicians being regarded as more open to it [41]. The generation gap was indicated by our respondents to be one of the consequences of the communist regime with its political repressions, restriction of human rights, cultural and artistic censorship and the educational curriculum that was carefully selected to represent the socialist ideology. Growing up and becoming educated in a country where a common cultural frame was created to remain isolated from broader global culture was believed to exert a significant influence on the attitudes, opinions and values of the generation and might constitute one of the reasons for lower interpersonal skills and openness among the older age group [42, 43]. In fact, Sztompka [43] uses the term “socialist cultural syndrome” to refer to the consequences of prevalent habituation and indoctrination of these times. Finally, some students were under the impression of inadequate respect for the religious and spiritual needs of patients of minority denominations in Polish hospitals. Although a patient’s right to receive spiritual care according to their affirmed faith is guaranteed under Polish law [44], some participants believed that hospital access to spiritual practices is narrowed down to only one dominant religion. This observation should prompt policy-makers to examine the situation as it may either indicate the limited awareness of students as future physicians in this area or, in fact, be a signal that in some healthcare facilities, law-guaranteed patients’ rights are not fully met.

The experiences of participants in our study revealed their primary concerns and anxieties related to collaboration with diverse patients, which were mainly caused by the feeling of confusion resulting from the reduced ability to comply with unfamiliar norms of social interactions but most importantly by the ethical conflict that arises between a clinician’s duty to safe life and a patient’s right for their autonomic choices. The clash between the respect for patients’ autonomy, expressed by accepting that it is the patient who has decision-making capacity regarding their care, even if their decisions refute the physician’s recommendations [45] and the doctor’s duty to provide care for patients through the application of evidence-based medicine, constituted the most evident moral dilemma for medical students. Students’ accounts were mostly concerned with Jehovah’s Witness patients, who, although being the third biggest religious denomination in Poland, constitute only 0.36% of the total population of the predominately Roman Catholic country [46]. As remarked by Trzciński et al. [47], nowadays, a different attitude to the treatment of JWs patients could be employed, as solutions have been introduced to avoid the religiously objectionable procedure of blood transfusions, which use, for example, colloid or crystalloid replacement fluids or intravenous iron dextran injections. The “bloodless surgeries”, however, are not widespread as they require a highly qualified and experienced team of clinicians to provide the alternative treatment [47]. Meanwhile, as can be expected, the situation in which “a mentally competent individual has an absolute right to refuse consent for medical treatment, for any reason, even when it may lead to his or her own death” [47] and a physician is legally obliged to concur in this decision seemed to be very difficult to accept for many participants in our study. Therefore, medical students should be to a greater extent educated on these substitute solutions as part of their studies to aid them in their future work, allowing them to, on the one hand, provide their patients with alternatives for blood transfusion and save their lives, and on the other hand, lessen the physicians’ burden and feeling of helplessness associated with wanting to help the patient but being unable to do so due to their refusal for treatment.

The majority of students stressed the significance of cultural competence in their future job as physicians in the demographically transforming country and many admitted making continuous attempts to increase their cross-cultural skills beyond the classroom through personal experiences, such as travelling abroad, participating in students’ exchange programmes, socializing with English Division students at their university, etc. Learning from their peers was especially valued and the large group of over 700 foreign students participating in medicine and dentistry programmes at Poznan University of Medical Sciences was seen as a valuable yet unfortunately untapped source of cultural interactions. This observation seems to confirm the results of a study by Liu et al. [48], the participants of which highlighted the beneficial effects of immersion in a diverse student population of their London-based medical school, emphasizing the idea of beyond-the-classroom cultural competence development. Moreover, the vast majority of participants highlighted the importance of formal cross-cultural education, indicating, at the same time, inattention to cultural competence training in medical education programmes. Students reported that cultural competence knowledge and skills are not adequately addressed in the medical curriculum, stressing the scarcity of courses, including language education, limited teaching methods and the scope of subjects related to cross-cultural issues. Likewise, findings concerning cultural education of healthcare professionals obtained from other studies conducted around the world revealed the insufficient attention of educational approaches to multicultural issues, lack of conceptual clarity concerning cultural diversity and cultural competence, little consistency in teaching methods and assessment tools, challenges in determining the most appropriate intervention strategies and integrating cultural activities into curricula, inadequate opportunities for students to practice learned cultural concepts, little faculty support and insufficient training of staff, etc. [48–54].

Finally, our analysis highlights simulated sessions with SPs as a valued learning modality, which seems to confirm the results of the previous research revealing Polish medical students’ positive reception of classes with simulated patients as a learning method and the increased attitudes and self-efficacy of their communication skills following them [55]. Many participants in our study saw simulated classes with human actors as the best learning strategy to introduce cultural knowledge and practice interactions with diverse patients and believed the sessions would be an effective method to prepare future physicians for cross-cultural encounters in clinical placements. Their positive attitude was also related to the support and feedback from SPs, which was mainly valued for its emotional content. As suggested by Pascucci et al. [56], such feedback is possible due to the thorough training that actors receive on how to respond to the students’ performances and is expected to reflect a personal, emotional experience rather than medical issues. Moreover, highlighting the deficiency in simulated interaction with multicultural elements, participants suggested integration of cultural issues into the scenarios employed during clinical communication or professionalism classes and suggested topics such as, for example, overcoming language barriers, distinct attitudes to personal space and touch, religious and ethnic differences, to be added to the scenarios. In fact, numerous studies demonstrated that the design of real-life, authentic scenarios incorporating cultural elements was an attainable goal. Various cultural challenges can be introduced into the scenarios, for example, patients with limited language proficiency, religious differences, attitudes to treatment and health based on beliefs, family and gender relations, immigration and economic status of patients, etc. [57]. The number of classes with human actors, allowing students to engage in cultural content interactions and practice cross-cultural skills, is insufficient. Indeed, only two participants in our study were able to recall cultural content scenarios introduced during their medical course, which indicates the need for the revision and modification of the medical curriculum. Moreover, the need for intensification of the simulated sessions promoting culturally competent care and incorporating them into an obligatory part of the medical curriculum was also stressed.

Limitations

One of the limitations of the current study is the fact that it was conducted among medical students of one Polish university, which limits the generalizability of the findings. By limiting the study to one geographical setting, we could not analyse the views of students from other institutions set in different parts of the country, who might present distinct attitudes towards cultural competence. However, qualitative methodology enabled us to gather considerable and in-depth information on the experiences, opinions and reflections of medical students regarding cultural competence enhancement, which we aim to examine further on a wider representative population of Polish medical students using a dedicated survey created based on the results of this study. Next, students who agreed to participate in our research might have more positive attitudes towards the study subject than the ones who were not willing to take part in the interview. To limit this risk, at all times of the recruitment process, the value of every student’s point of view and opinions (both positive and negative) was highlighted. Moreover, the number of female respondents exceeded the males, but it reflected a smaller number of male students among the medical student population at our university. The data provided by the Office of Students Affairs of Poznan University of Medical Sciences show that among 2589 of the total number of medical students in the academic year 2022/2023, there were 1643 (63.4%) females and 946 (36.5%) males.

Conclusions

To conclude, in view of the above data, it seems that Polish medical students express positive attitudes towards cross-cultural competence development and perceive cultural skills as a way to improve human interactions, patient-doctor relations as well as their personal satisfaction. They seem to appreciate the change in the eagerness to open for diversity, which, as they observe, is currently taking place in Poland. Participants’ experiences indicate that although numerous shortcomings in cultural skills and deficiencies in cultural sensitivity still exist, the cultural knowledge, attitudes and skills of many Polish people are noticeably increasing. Many students highlighted the growth in cultural sensitivity of Polish healthcare professionals while giving an account of the involvement of medical staff in the process of delivering help to Ukrainian refugees. However, many obstacles to physicians’ cultural competence are still observed, mainly in the lack of linguistic proficiency, often perceived as the sole factor capable of significantly jeopardizing successful cross-cultural encounters, but also in ethical dilemmas and difficult choices that often need to be made to accommodate the needs of patients. The conflict between a doctor’s duty to save lives and a patient’s freedom to comply with the recommendation or not was the cause of the biggest moral and ethical concerns expressed by future physicians in our study. A lack of insufficient level of cultural knowledge and competencies, seen as a potential cause for misunderstanding and embarrassment, also generated substantial anxiety in students. Finally, in their attempt to find solutions to overcome many obstacles in their path to cultural competence, students call for more attention to cross-cultural education in the medical curriculum. Participants view the number of classes where culture-based care is emphasized as insufficient and request for their intensification and modification. They expect the medical studies to equip them with the ability to understand and apply culture-sensitive actions and knowledge to provide the best quality care and see the need for the medical curriculum to include cultural training to improve communication with diverse patients. To achieve this goal, calls for the intensification of cultural training and the implementation of experiential teaching methods, such as medical simulation and simulated patients, were made.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all students participating in the study.

Abbreviations

- SPs

Simulated Patients

- JW

Jehovah’s Witness

Author contributions

AW, PP, PMS and EB contributed to study conception and design; AW contributed to the data collection; AW and PP contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, AW prepared the initial draft of the article with revisions by PP, PMS, MN and EB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The project of the study was submitted to the Bioethics Committee of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences, which confirmed that its approval was not required under Polish law since the study was not a medical experiment (Decision No. KB-915/22). Informed consent was obtained from all students prior to their participation in the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Henderson S, Horne M, Hills R, Kendall E. Cultural competence in healthcare in the community: a concept analysis. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26:590–603. 10.1111/hsc.12556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross TL, Bazron BJ, Dennis KW, Isaacs MR. Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care: A Monograph on Effective Services for Minority Children Who Are Severely Emotionally Disturbed. Washington, DC; 1989.

- 3.Dreachslin Janice L, Gilbert M, Jean MB. Diversity and cultural competence in Health Care: A systems Approach. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2013;26.

- 4.Purnell L. The Purnell Model for Cultural competence. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13:193–6. 10.1177/10459602013003006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Przyłęcki P. Kompetencje kulturowe w opiece zdrowotnej. Władza Sądzenia. 2019;16:10–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R. Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:232. 10.1186/s12913-018-3001-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campinha-Bacote J. The process of Cultural competence in the delivery of Healthcare services: a model of Care. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13:181–4. 10.1177/10459602013003003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural Humility Versus Cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in Multicultural Education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:117–25. 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Gill E, Li S. Revisiting cultural competence. Clin Teach. 2021;18:191–7. 10.1111/tct.13269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkins K, Lorelle S. Cultural Humility: lessons learned through a Counseling Cultural Immersion. J Counselor Preparation Superv. 2022;15:9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomorrow’s doctors. General Medical Council. 2003. https://www.educacionmedica.net/pdf/documentos/modelos/tomorrowdoc.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2023.

- 12.Douglas MK, Pierce JU, Rosenkoetter M, Callister LC, Hattar-Pollara M, Lauderdale J, et al. Standards of Practice for culturally competent nursing care: a request for comments. J Transcult Nurs. 2009;20:257–69. 10.1177/1043659609334678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Echeverri M, Chen AMH. Educational interventions for culturally competent Healthcare: developing a protocol to Conduct a systematic review of the Rationale, Content, teaching methods, and measures of effectiveness. J Best Pract Health Prof Divers. 2016;9:1160–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musolino GM, Babitz M, Burkhalter ST, Thompson C, Harris R, Ward RS, et al. Mutual respect in healthcare: assessing cultural competence for the University of Utah Interdisciplinary Health Sciences. J Allied Health. 2009;38:e54–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brach C, Fraserirector I. Can Cultural Competency reduce racial and ethnic Health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:181–217. 10.1177/1077558700057001S09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jernigan VBB, Hearod JB, Tran K, Norris KC, Buchwald D. An examination of Cultural competence training in US Medical Education guided by the Tool for assessing Cultural competence training. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2016;9:150–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P. Global Health in Medical Education: a call for more Training and opportunities. Acad Med. 2007;82:226–30. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305cf9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaroszewicz M. Kryzysowa Migracja Ukraińców. Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich Im. Marka Karpia. 2015;187:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozporządzenie Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego z dnia 26. lipca 2019r. w sprawie standardów kształcenia przygotowującego do wykonywania zawodu lekarza, lekarza dentysty, farmaceuty, pielęgniarki, położnej, diagnosty laboratoryjnego, fizjoterapeuty i ratownika medycznego. https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20190001573/O/D20191573.pdf. Accessed 26 Sep 2022.

- 20.Przymuszala P, Cerbin-Koczorowska M, Marciniak-Stepak P, Szlanga L, Zielinska-Tomczak L, Dabrowski M, et al. Communication skills learning during medical studies in Poland: opinions of final-year medical students. Disaster Emerg Med J. 2021;6:172–82. 10.5603/DEMJ.a2021.0035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun V, Clarke V. (Mis)conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts’ (2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2016;19:739–43. 10.1080/13645579.2016.1195588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18:328–52. 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun V, Clarke V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int J Transgend Health. 2023;24:1–6. 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun V, Clarke V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns Psychother Res. 2021;21:37–47. 10.1002/capr.12360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic analysis. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2019. pp. 843–60. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai D-Y. A concept analysis of cultural competence. Int J Nurs Sci. 2016;3:268–73. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE, Normand J. Culturally competent healthcare systems. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:68–79. 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00657-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betancourt JR, Corbett J, Bondaryk MR. Addressing disparities and achieving equity. Chest. 2014;145:143–8. 10.1378/chest.13-0634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.García-Izquierdo I, Montalt V. Cultural competence and the role of the patient’s mother Tongue: an exploratory study of Health professionals’ perceptions. Societies. 2022;12:53. 10.3390/soc12020053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, Saver BG. Disparities in Health Care by Race, ethnicity, and Language among the Insured. Med Care. 2002;40:52–9. 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flores G, Abreu M, Olivar MA, Kastner B. Access barriers to Health Care for latino children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:1119–25. 10.1001/archpedi.152.11.1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maly NC, Commentary. Language barriers in medicine and the role of the pediatric dermatologist. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:164–6. 10.1111/pde.14696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Rosenthal A, Stewart AL, Wang F, et al. Physician language ability and cultural competence. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:167–74. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30266.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lam CK, Kiser TC, Metzler-Sawin E, Brown CA, Ward CL. Utilizing evidence-based guidelines to develop a language barriers simulation. Contemp Nurse. 2020;56:534–9. 10.1080/10376178.2020.1855996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]