Abstract

Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) is a toxic industrial chemical, necessitating low-level detection capabilities for safety and environmental monitoring. This study introduces a novel approach for detecting hydrogen cyanide (HCN) using a clamp-type custom quartz tuning fork (QTF) integrated with a dual-tube acoustic micro-resonator (AmR) for enhanced photoacoustic gas sensing. The design and optimization of the AmR geometry were guided by theoretical simulation and experimental validation, resulting in a robust on-beam QEPAS (Quartz-Enhanced Photoacoustic Spectroscopy) configuration. To boost the QEPAS sensitivity, an Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifier (EDFA) was incorporated, amplifying the laser power by approximately 286 times. Additionally, a transformer-based U-shaped neural network, a machine learning filter, was employed to refine the photoacoustic signal and reduce background noise effectively. This combination yielded a significantly low detection limit for HCN at 0.89 parts per billion (ppb) with a rapid response time of 1 second, marking a substantial advancement in optical gas sensing technologies. Key modifications to the QTF and innovative use of AmR lengths were validated under various experimental conditions, affirming the system's capabilities for real-time, high-sensitivity environmental monitoring and industrial safety applications. This work not only demonstrates significant enhancements in QEPAS but also highlights the potential for further technological advancements in portable gas detection systems.

Keywords: Photoacoustic spectroscopy, Quartz tuning fork, Trace gas sensor, Quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy

1. Introduction

In recent years, significant strides have been achieved in the theory and design of artificial neural networks, particularly in signal processing. It is imperative to cultivate a thorough comprehension of fundamental neural network structures and their profound implications on signal processing algorithms and applications [1]. With the progression of computer technology, neural networks have witnessed escalating utilization in estimation tasks. In comparison to conventional state estimation methods like the Wiener filter and Kalman filter, neural networks offer a distinct advantage in handling uncertainty factors and demonstrate applicability in highly nonlinear systems [2].

Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) is a molecule of substantial industrial and environmental importance. This compound is utilized in a variety of industrial applications, from synthesizing adiponitrile for nylon production to formulating specialized pharmaceuticals [3]. However, the utility of HCN is overshadowed by its significant toxicity, which has resulted in its classification as a chemical warfare agent [3], [4]. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has highlighted the dangers associated with HCN exposure, setting a stringent short-term exposure limit at 4.7 ppmv, emphasizing the risks posed by even low concentrations of this compound [5], [6], [7].

In the context of space missions, HCN detection becomes critically significant. In the closed environment of a spacecraft, potential hazards such as fire, system malfunctions, or unintended chemical releases demand immediate monitoring [8], [9]. Primary fire risks stem from solid materials, including overheated wires, cable bundles, and circuit boards [10], the combustion of which releases various trace gases including HCN [11]. Recognizing this, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has prioritized the development of fire detection technologies for manned spacecraft cabins, targeting the detection of HCN as early indicators of potential fires [12]. In their pursuit, NASA is advancing gas sensing technology to enhance the safety and emergency response of manned spacecraft in case of a fire [4], [5], [6], [9]. Additionally, HCN has been identified in planetary atmospheres during exploration missions [13]. On the earth, the primary anthropogenic sources of HCN include vehicle emissions and metallurgical processes [3]. The need for HCN sensors is thus underscored by their widespread industrial use, environmental impact, and relevance in specialized areas such as space exploration. The advancement of HCN detection methods is a crucial juncture between enhancing safety and scientific advancement.

In recent years, there has been significant progress in HCN gas detection technology, enhancing both sensitivity and response time [14]. Photoacoustic spectroscopy (PAS) has become a favored method for trace gas detection due to its robustness and compactness [15], [16]. PAS operates on the principle that modulated light sources excite molecules from their ground states to excited states [17], [18]. The subsequent de-excitation by vibrational transduction (V-T) relaxation produces periodic heating, generating acoustic waves [19], [20], [21]. To avoid 1/f noise and ambient background disturbances, modulation frequencies greater than 1 kHz are typically employed [22], [23]. The amplitude of the acoustic signal S in PAS can be expressed by (1), (2) [24], [25]:

| S∼αQP/ƒ | (1) |

| α=σN | (2) |

where α is the absorption coefficient, Q is the quality factor of the resonator, P is the effective optical power, f is the modulation frequency, σ is the absorption cross-section, and N is the concentration of gas molecules, respectively. A unique advantage of PAS is its independence from the light absorption path length [26], [27]. Signal enhancement can be effectively achieved by increasing the laser excitation power [28], [29]. PAS distinguishes itself from other spectroscopic methods by not requiring an optical detector; instead, an acoustic transducer is used to convert acoustic waves into electrical signals [30], [31]. These attributes afford PAS with high sensitivity within a compact and robust sensor design [32], [33], [34], with applications spanning medical diagnostics, chemical analysis, industrial processes, and environmental monitoring [25], [32], [35].

Quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy (QEPAS), a derivative of PAS, substitutes the conventional microphone-based approach with a quartz tuning fork (QTF) [36], [37], [38]. QTFs are piezoelectric elements of millimeter-scale, routinely integrated into clocks and electronic circuits to maintain time [39], [40], [41], [42]. The QTFs exhibit a high Q-factor of approximately 10,000 and a narrow resonant frequency bandwidth of only a few Hz at standard atmospheric pressure, even with metal casings removed [43], [44], [45], [46]. This sharp resonance enhances the selectivity of QEPAS and its immunity to ambient noise [47], [48], [49], [50]. The QEPAS spectrophone, comprising a QTF and an acoustic micro-resonator (AmR), leverages the AmR, typically made of stainless-steel capillaries, to foster acoustic resonance and amplify the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [51]. Numerous QEPAS spectrophone variations have emerged over the past decades, aiming to elevate QEPAS sensor performance [52], [53], [54], [55]. Initially, QEPAS employed commercially available watch QTFs since 2002. However, to improve optical collimation and leverage molecular V-T relaxation, Spagnolo et al. introduced custom tuning forks in 2014 [56]. These custom forks, featuring novel vibration modes [57], [58], octupole electrodes [59], and optimized T-shaped prongs [60], [61], marked a significant enhancement. Most recently, Zheng et al. have reported a novel clamp-type QTF with an aperture of approximately 1 mm and a Q-factor exceeding 10,000 [51]. This clamped QTF, built upon the cost-effective and resonantly comparable watch QTF, differs from previous custom designs.

In this work, we unveil the application of a clamp-type custom quartz tuning fork (QTF) coupled with a dual-tube acoustic micro-resonator (AmR) aimed at highly sensitive HCN photoacoustic gas sensing. A pair of specifically designed longitudinal AmRs were introduced to work in conjunction with the clamp-type custom QTF. The AmR geometry was meticulously optimized through theoretical calculations and empirical validation, resulting in a robustly coupled on-beam QEPAS configuration. The on-beam configuration, where the laser beam passes directly through the gap between the prongs of the quartz tuning fork (QTF) and is aligned with the acoustic micro-resonator (AmR), was chosen for its superior optical alignment and energy coupling efficiency. This setup facilitates stronger photoacoustic coupling and improved signal strength compared to the off-beam configuration, making it ideal for achieving high sensitivity and low detection limits in HCN detection. Recognizing the direct proportionality of QEPAS sensitivity to the optical excitation power, the inclusion of an Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifier (EDFA) proved substantially advantageous [62], [63], [64]. The EDFA was utilized to amplify the laser power by approximately 286-fold. The increased laser power enhances the photoacoustic signal due to the greater number of absorbed photons, which generate stronger acoustic waves, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). This leads to more accurate and reliable detection of trace gas concentrations. However, while the EDFA amplifies the laser power, it can also cause a slight degradation in beam quality. To mitigate the potential increase in noise due to this degradation, we optimized the structure of the quartz tuning fork, effectively maintaining a high SNR and ensuring a substantial improvement in sensitivity. This optimization allows the system to detect lower concentrations of hydrogen cyanide (HCN) by amplifying the acoustic response and achieving a lower detection limit. To improve the sensor performance, we employed a neural network filtering method based on machine learning, known as the transformer-based U-shaped neural network, tailored to refine the photoacoustic signal and effectively mitigate background noise. This multifaceted approach culminated in attaining a detection limit for HCN as low as 0.89 parts per billion (ppb). With an expedient response time of 1 second for online monitoring, these findings represent the most sensitive HCN detection reported to date via optical methods, to the best of our knowledge.

2. Experiment

To facilitate easier optical collimation and stronger photoacoustic transducing capability, we adopted a clamp-type QTF as the core of our QEPAS spectrophone. Initial modifications involved the removal of the standard watch QTF's metal casing, resulting in a measured resonance frequency and quality (Q) factor of 32,763.2 Hz and 11,584, respectively. A noteworthy adaptation was the inclusion of an aperture of 900 µm in diameter d, situated 0.7 mm from the QTF opening. The clamp-type configuration led to a resonance frequency shift to 34,891.6 Hz. However, the Q factor was kept at 11,216. The detailed resonance curve for the clamp-type QTF can be seen in Fig. 1(a). Lorentz fitting was used to obtain the resonance peak. The Q factor was calculated by dividing the resonance frequency f0 by its full width at half maximum Δf. The resonance was measured at the excitation voltage of 400 mV peak-to-peak.

Fig. 1.

(a) Resonance curve of clamp-type QTF. (b) Resonance curve of clamp-type QTF with the AmRs of varying lengths.

To enhance the acoustic signal amplitude with the clamp-type QTF, we chose the on-beam QEPAS configuration with strong photoacoustic coupling, not the off-beam configuration with the advantage of easy optical collimation [53]. The employment of on-beam configuration benefits from the ∼900 μm large aperture of the custom clamp-type QTF, which is 3 times larger than the usually used 3×8 mm standard QTF [51]. A pair of longitudinal AmRs were made by a stainless-steel capillary using an ultra-precision CNC machine tool. The outer diameter and inner diameter of the AmR were 1.2 mm and 1.0 mm, respectively. To ensure the beam passes through the aperture and the resonator clearly, the inner diameter of the resonator was designed to be slightly larger than that of the aperture. To explore the optimal length of the AmR, we made four different AmRs with lengths L of 4.0 mm, 4.1 mm, 4.2 mm, and 4.3 mm, respectively. Positioned symmetrically on each side of the clamp-type QTF, the AmRs formed an on-beam configuration in which the laser beam was co-axially directed, with a precise gap D = 20 µm maintained from the end of the AmR to the QTF plane, as depicted in Fig. 2(b).

Fig. 2.

(a) Front view of the clamp-type QEPAS, (b) Schematic diagram of double-tube longitudinal AmRs. d: the diameter of the aperture. L: the length of AmRs. D: the distance between the AmR end and the QTF plane.

The combined QTF and AmR system constitutes an on-beam QEPAS spectrophone. The resonance curves of the QEPAS spectrophones with different AmR lengths are compared in Fig. 1(b), indicating minimal shifts in resonance frequency. The frequency shift was less than 0.1 Hz. The 4.1 mm AmR demonstrated the highest resonance amplitude and, in combination with photoacoustic detection performance metrics, was determined to be the optimal length. Finite element analysis was conducted using the "Pressure Acoustic, Frequency Domain" module of COMSOL Multiphysics to evaluate the effect of AmR length on sound pressure levels. By varying the dimensions and configurations of the AmR in the simulation, we identified the optimal geometry that maximized sound pressure levels and acoustic coupling efficiency. The QTF was modeled as a cantilever beam, one end of which was fixed, enabling it to vibrate in a flexural mode. By holding the resonance frequency of the clamp-type QTF constant, we measured the absolute total sound pressure intensity produced by varying AmR lengths. The laser excitation was optimally positioned by centering the circular aperture at 0.7 mm below the opening of a standard QTF with dimensions of 3×8 mm. Simulation results, as depicted in Fig. 3(a), indicated the theoretical optimal length of each AmR to be 4.1 mm to maximize absolute total sound pressure. Consequently, the aggregate length of the on-beam longitudinal resonator is 8.2 mm. In the context of a custom clamp-type QTF resonating at 34,891.6 Hz, the optimal total AmR length ranged between half and a full wavelength, accounting for the separation distance from the QTF plane.

Fig. 3.

(a) Simulation of the sound pressure curve, (b) 2 f signal amplitudes corresponding to the different AmR lengths.

In this work, a pair of acoustic resonators was coupled with a quartz tuning fork to enhance the signal. The relationship between the Q factor of the quartz tuning fork and detection sensitivity is complex. In Fig. 4, the schematic diagram of the Q factor measurement is shown. A series of sine signals with constant amplitude but different frequencies were produced by a function generator to drive the tuning fork. The output of the tuning fork was recorded by a preamplifier and a lock-in amplifier. A decrease in the Q factor of the tuning fork indicates energy transfer between the tuning fork and the resonator. However, regardless of the presence of a resonator, only the response of the tuning fork was recorded. Thus, the obtained Q factor corresponds to the Q factor of the tuning fork alone, not the Q factor of the coupled tuning fork-resonator system. All the work were carried out at atmospheric pressure.

Fig. 4.

The schematic diagram of the QEPAS system for HCN gas detection.

Verification experiments were conducted using four QEPAS spectrophones with varying AmR lengths to detect H2O in ambient air. The air's relative humidity was monitored using an electronic humidity meter. We normalized the photoacoustic signal amplitude against the calculated absolute H2O molecule concentration. Fig. 3(b) illustrated the normalized 2 f signal amplitudes corresponding to the different AmR lengths. The normalized photoacoustic signal amplitude peaked at an AmR length of 4.1 mm, aligning with our theoretical predictions. Ultimately, we selected a pair of longitudinal AmRs, each with an inner diameter of 1.0 mm and a length of 4.1 mm, to construct the on-beam QEPAS spectrophone. The bare clamp-type QTF without an AmR was measured, and the signal amplitude was found to be 1.56×10−4 V. In comparison, with the 4.1 mm AmRs, the signal amplitude increased to 2.12×10−3 V. This optimized configuration enhanced the photoacoustic signal amplitude by a factor of 14.6 compared to a bare clamp-type QTF without an AmR. Subsequent studies employed the optimized on-beam QEPAS spectrophone for HCN detection.

The schematic diagram of the QEPAS system for HCN gas detection was shown in Fig. 4. The system utilized a distributed feedback (DFB) diode laser as the excitation source, which emitted at a central wavelength of 1538 nm. This wavelength can be roughly adjusted by temperature changes and finely tuned through injection current. Enclosed in a butterfly package, the laser’s pigtail is fused to the input of an EDFA using an optical fiber fusion splicer. A C-band EDFA, with an amplification capability of 40 dBm, amplifies the optical power emanating from the diode laser. Subsequently, the output from the EDFA was directed through an OZ Optics fiber focuser with an approximate focal length of 1 cm. The aim was to concentrate the amplified laser beam through the QEPAS spectrophone with precision, ensuring that incidental scatter light would not strike the spectrophone, which could impede the system's performance. To enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the detection, a second harmonic (2 f) detection technique was implemented [34]. A dual-channel arbitrary waveform generator (Tektronix AFG3102) produced a ramp signal, which, through the Thorlabs CLD1015 laser driver, finely tuned the laser emission wavelength. In parallel, a sine wave at half the resonance frequency (f0/2) of the QEPAS spectrophone was generated to modulate the laser wavelength, in which f0 was the resonance frequency of the QEPAS spectrophone. The signals from the clamp-type QTF were first processed by a custom trans-impedance amplifier, which features a feedback resistance of 10 MΩ. To mitigate any electromagnetic interference, the QEPAS spectrophone and the preamplifier were enclosed within a compact, shielded module [65]. The signal was then conveyed to a lock-in amplifier (Stanford SRS 830) and demodulated in the 2 f mode. The lock-in amplifier was configured with a time constant of 1 s and a filter slope of 12 dB/octave. Communication with a personal computer (PC) was established via the RS232 serial port for data acquisition and control. For testing, gas mixtures with varying HCN concentrations were prepared using a 99.999 % pure nitrogen (N2) gas cylinder and a 20 ppm HCN gas cylinder. The dynamic mixing of gases was performed using a gas dilution system equipped with two mass flow controllers (MFCs). To optimize the signal quality, taking into account noise and gas flow effects within the high-power setup [66], the gas flow rate was maintained at 150 standard cubic centimeters per minute (SCCM). Control over the entire experimental setup was exerted through a custom-developed LabView program.

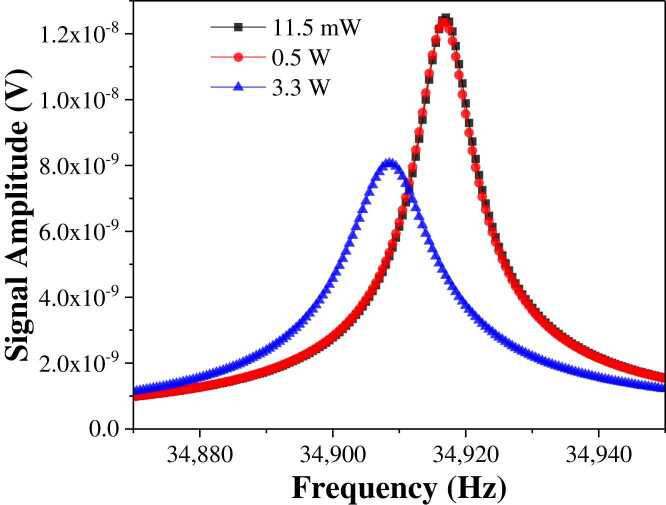

Before the detection of HCN, it is essential to calibrate the resonance frequency of the QEPAS spectrophone. In this experiment, we evaluated the thermal effects attributed to high excitation power. The diode laser’s output was fixed at 11.5 mW, while the output power from the EDFA was varied from 0.5 W to 3.3 W which is the output power range of the EDFA, from the minimum power output of 0.5 W at this wavelength, to the maximum power the EDFA can amplify. The resonance curves of the spectrophone at different levels of optical excitation power utilizing a consistent electrical drive method were recorded. The results were shown in Fig. 5. The resonance frequency shifts observed at higher laser powers are primarily due to thermal effects induced by increased laser power. However, once the laser power stabilizes, the temperature also reaches a steady state. Therefore, while initial power changes can cause frequency shifts, the system can maintain long-term stability and accuracy as the thermal conditions stabilize. This steady state ensures that the sensor remains reliable over extended periods, with minimal drift in resonance frequency, thus preserving the accuracy of the measurements. With the Lorentz fitting, the resonance frequencies and Q factors were summarized in Table 1. As the excitation power increased from 11.5 mW to 0.5 W, the resonance frequency remained relatively stable, at approximately 34,913 Hz. Concurrently, the Q factor decreased from 4757 to 4079, with a decline of 14.25 %. However, when the excitation power was further increased from 0.5 W to 3.3 W, there was a remarkable shift in the resonance frequency, descending from 34,913.3 Hz to 34,908.5 Hz. The Q factor diminished significantly to 2844, with a 30 % reduction. These findings indicated pronounced thermal effects when the excitation optical power exceeded 3.3 W. Consequently, for the QEPAS system, it is critical to adjust the modulation frequency to account for the thermal effects observed at higher optical excitation powers.

Fig. 5.

Clamp-type QTF resonance frequency at different laser power.

Table 1.

Parameters of clamp-type QTFs with different laser power.

| Laser Power (W) | Frequency (Hz) | Q Factor |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0115 | 34,913.7 | 4757 |

| 0.5 | 34,913.3 | 4079 |

| 3.3 | 34,908.5 | 2844 |

Upon reviewing the molecular absorption lines ranging from 6494 cm−1 to 6504 cm−1 within the HITRAN database [67], an HCN absorption line located at 6501.239 cm−1 with an intensity of 5.86×10−21 cm/molecule was selected as the target. This target line is devoid of spectral overlap from common atmospheric constituents such as water vapor (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2), ensuring unambiguous detection. A 20 ppm HCN:N2 standard gas mixture and a diode laser in conjunction with an EDFA were employed for detection. The diode laser's injection current was tuned between 76 mA and 102 mA by the ramp signal, corresponding to an emission wavelength sweep from 6500.91 cm−1 to 6501.82 cm−1. The resulting 2 f signals were displayed in Fig. 6. Remarkably, the peak signal obtained with a 3.3 W EDFA reached 1.04×10−3 V, a substantial enhancement by a factor of 193.47 compared to the 11.5 mW diode laser. Despite a significant increase in optical power, approximately 286-fold, the noise level remained commendably stable. This exemplary noise suppression capability can be ascribed to the custom design of the clamp-type QTF, featuring a 900 μm diameter aperture. This aperture is sufficiently large to allow the laser beam to pass through.

Fig. 6.

HCN 2 f signal of different laser power at a flow rate of 150 SCCM and a concentration of 20 ppm.

3. Results and discussion

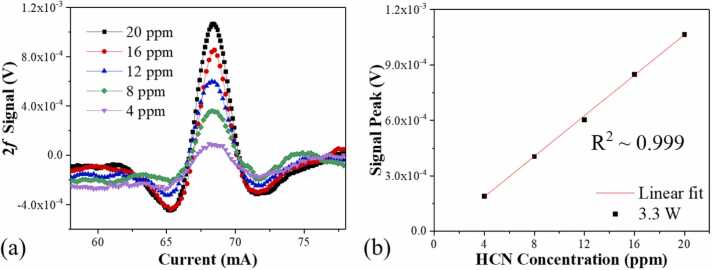

In the subsequent phase, measurements of different HCN:N2 gas mixture concentrations were conducted using the EDFA-boosted QEPAS sensor to validate its performance. Concentrations ranging from 4 ppm to 20 ppm of HCN gas were prepared to utilize the aforementioned gas dilution system. The power of the EDFA was set as 3.3 W, and the laser modulation depth was set as 2.28 cm−1. In our experiments, we have tested HCN concentrations up to 20 ppm, and the sensor demonstrated a linear response throughout this range. Therefore, the upper limit of HCN concentration that the sensor can accurately detect is up to 20 ppm, ensuring reliable performance across both low and relatively high concentration levels. The obtained results were displayed in Fig. 7(a), where an increase in HCN concentration was observed to proportionally enhance the 2 f signal. The experiments were replicated three times, and from these, the 2 f signal peaks were extracted from the waveforms. These peaks were then used to construct the response curve, as illustrated in Fig. 7(b). A linear fit was applied to the gas concentration-response data, from which an R-square value of 0.999 was derived, indicating the sensor’s robust linearity.

Fig. 7.

(a) HCN signal amplitude with different gas concentrations, (b) Concentration and signal linearity.

The implementation of a neural network filtering method based on deep learning, known as the U-net, was undertaken to enhance the performance of the QEPAS sensor. This innovative machine-learning method dynamically assigns varying weights to individual sampling points, aiming to streamline the complex manual parameter evaluation process and enhance the effectiveness of spectral filtering [68]. The U-net neural network offers significant advantages over traditional noise reduction methods. Traditional methods, such as Fourier or wavelet transforms, often require manual tuning of parameters and may not effectively handle complex noise patterns. In contrast, the U-net neural network automatically learns the noise characteristics from the data, providing more accurate and adaptive noise reduction. While the U-net approach has higher computational complexity due to the deep learning model, it is more efficient in terms of noise suppression and preserving signal integrity. The U-net model's ability to perform end-to-end learning and its robustness in dealing with various noise types make it a superior choice for our application, ensuring high sensitivity and low detection limits. As shown in Fig. 8, the 2 f signals will first undergo dimensional reduction upon its import into the training set. This process involves data sampling and feature extraction, facilitated by skip connections. Initially, the data are passed through the dimensioning component to prepare for subsequent data combinations. This step is followed by repeated dimensionality reduction until reaching the lowest dimensionality. Subsequently, the data undergoes dimensional uplift to return to its original dimensionality. The results of this uplift are then combined with the results of the initial reduction to obtain optimized outcomes. This iterative process of dimensionality uplift continues until the data achieves its final optimized state. The U-net was implemented using the Pytorch deep learning framework. U-net consists of DownBlocks, MidBlocks, and UpBlocks. DownBlocks is responsible for compressing the dimension of the input one-dimensional signal from 1 × 1 × 256–1 × 64 × 64 to achieve the role of information extraction. MidBlock is a bottleneck layer. This layer is responsible for reducing the dimensionality of the input data, compressing the information, and extracting features. This compression helps in reducing the computational complexity and memory requirements of the network, making it more efficient. UpBlocks is responsible for outputting the denoised 2 f signal through the hidden state from DownBlocks and MidBlock. The detailed information of the U-net is presented in Table 2. During the algorithm training process, we used a batch size of 256, an Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0001, and performed 39, 000 steps (shown in Table 3). All training and testing were conducted on an NVIDIA 2080 Ti GPU. The data source for training the U-net model comprised experimentally obtained photoacoustic signals of varying hydrogen cyanide (HCN) concentrations under different environmental conditions. The parameters of the U-net model were obtained from the Unet1DModel in diffusers (https://huggingface.co).

Fig. 8.

The complete architecture of U-net.

Table 2.

The detailed information of the U-net.

| Input – 1 × 1 × 256 | ||

|---|---|---|

| DownBlocks | DownBlock | Resnets – 1 × 32 × 256 |

| DownsampleBlock | Downsample – 1 × 32 × 128 | |

| Resnets – 1 × 32 × 128 | ||

| AttnDownBlock | Downsample – 1 × 32 × 64 | |

| Resnets & attentions – 1 × 64 × 64 | ||

| MidBlock | Downsample – 1 × 64 × 32 | |

| Resnets & attentions – 1 × 64 × 32 | ||

| Upsample – 1 × 64 × 64 | ||

| UpBlocks | AttnUpBlock | Resnets & attentions – 1 × 32 × 64 |

| Upsample – 1 × 32 × 128 | ||

| UpsampleBlock | Resnets – 1 × 32 × 128 | |

| Upsample – 1 × 32 × 256 | ||

| UpBlock | Resnets – 1 × 1 × 256 | |

| Output – 1 × 1 × 256 | ||

Table 3.

U-net training parameters.

| Batch Size | Steps | Optimizer | Learning Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 256 | 39,000 | Adam | 0.0001 |

Unlike conventional machine learning methods based on U-shaped networks, which analyze spectral data at a global level, enabling them to consider dependencies and relationships across all data points, this approach enhanced the algorithm’s ability to discern critical features within spectra. As a result, it achieved more accurate and reliable filtering of HCN absorption information, even in the presence of noise [69]. By first reducing the data to a low latitude and then elevating it to a high latitude, a connection was established between the descending and ascending dimensions. Utilizing this connection, U-net noise filtering was implemented without decreasing the peak value of the signal, as illustrated by the U-net filtered noise graph in Fig. 9. Fig. 9(a) illustrates the peak comparison between the original 2 f signal and the U-net processed 2 f signal. The inset of Fig. 9(a) is the zoom of the 2 f signal peak. From the inset, it can be observed that the peak of the original signal is 1.08×10⁻³ V, whereas the peak of the U-net processed signal is 1.07×10⁻³ V, showing a difference of less than 1 %. The obtained noise was shown in the Fig. 9(b). In regions far from the molecular absorption lines, the sensor noise is relatively low due to the lack of absorption. In this experiment, to simulate real-world continuous monitoring scenarios and obtain the true noise of the sensor, the laser wavelength was locked at the molecular absorption line and filled the photoacoustic cell with pure nitrogen to evaluate the noise level. It was observed that the signal level remained nearly constant, while a significant reduction in the 1σ noise level was noted, from 2.77 μV to 0.048 μV. The detection SNR and the Normalized Noise Equivalent Absorption (NNEA) coefficient were tabulated in Table 4. The results indicated that the detection SNR could be augmented by a factor of 58. Conclusively, with a 1-second integration time, the sensor achieved a 1σ detection limit and an NNEA coefficient of 0.89 ppb and 2.31×10−9 W·cm−1·Hz−1/2, respectively. The baseline noise level of our QEPAS system is 0.048 μV, which significantly influences the detection limit. This low noise level, achieved through the optimized design of the quartz tuning fork and the implementation of the U-net noise filtering technique, allows for the detection of weaker signals and enhathences the system's sensitivity. The low noise floor is essential for accurately detecting trace concentrations of hydrogen cyanide (HCN), ensuring high sensitivity and reliability in our measurements. Compared with reference [14], which reports an MDL of 29 ppb, our results may initially appear to have a gap. However, it is important to note that our experiments used different equipment. The application of the U-net noise filtering technique significantly improved our detection sensitivity. Although there is a difference, 29 ppb and 51.77 ppb are within the same order of magnitude, demonstrating that our approach remains competitive.

Fig. 9.

(a) 2 f signal amplitude with and without U-net, inset: the zoom of the peak 2 f signal amplitude (b) Noise levels with and without U-net, inset: the zoom of the noise obtained with U-net noise filtering.

Table 4.

Comparison table original signal and U-net signal. DL: detection limit.

| Signal (V) |

1σ Noise (V) |

SNR | DL (Ppb) |

NNEA (W·cm−1·Hz−1/2) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 1.07×10−3 | 2.77×10−6 | 386.28 | 51.77 | 1.32×10−7 |

| U-net | 1.08×10−3 | 4.82×10−8 | 22406.63 | 0.89 | 2.31×10−9 |

Table 5 provides a comparative analysis of the performance of various mainstream. HCN sensors developed in recent years, with a particular emphasis on response time and detection sensitivity. Optical detection methods, represented in the table, are notable for their relatively rapid response, typically on the order of seconds, as well as their impressive detection thresholds. Optical sensors employed mid-infrared optical parametric oscillator or integrated cavity can achieve a sensitivity of ppb level. Traditional QEPAS sensor obtained a detection sensitivity of 21 ppb with 1 s integration time [14].

Table 5.

Comparison of various HCN gas sensors.

| Method | Average time | Sensitivity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion mobility spectrometer | A few seconds | 20 ppb | [70] |

| Polymer nanocomposite material | 21 seconds | 890 ppb | [71] |

| Resonance silicon film | \ | 2 ppm | [72] |

| Quartz crystal microbalance sensor | 1 second | 169 ppb | [73] |

| Colorimetric paper | 5 minutes | 10 ppb | [74] |

| Fluorometric detection | 10 seconds | 60 ppm | [75] |

| Photonic crystal cavity | \ | 2 ppm | [76] |

| Tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy | \ | 1 ppm | [77] |

| Traditional QEPAS | 1 second | 21 ppb | [14] |

| Mid-infrared optical parametric oscillator-based photoacoustic spectroscopy | 1 second | 0.19 ppb | [78] |

| Off-aixs integrated cavity output spectroscopy | 1 second | 8 ppb | [79] |

| Clamp-type QEPAS | 1 second | 0.89 ppb | This work |

In this work, a lower-cost clamp-type QTF with optimized dual tube AmRs were developed. The sensor handles potential interference from other gases through several key mechanisms. First, the QEPAS system is highly selective due to the precise tuning of the laser wavelength to the specific absorption line of hydrogen cyanide (HCN). This minimizes the likelihood of interference from other gases. Additionally, the high Q-factor of the quartz tuning fork (QTF) enhances the system's selectivity by narrowing the detection bandwidth. Furthermore, the use of advanced signal processing techniques, including the U-net neural network, helps to further distinguish the HCN signal from background noise and potential interfering signals. These combined features ensure that the sensor can accurately detect HCN even in the presence of other gases commonly found in industrial or environmental settings. The rapid response time of 1 second for HCN detection in our study was measured using the lock-in amplifier setup. The lock-in amplifier was configured with a time constant of 1 second, which directly determines the system's response time by defining how quickly the output signal stabilizes in response to changes in the detected gas concentration [80]. Factors contributing to achieving this rapid response include the high sensitivity and fast reaction of the quartz tuning fork (QTF), the efficient acoustic coupling in the QEPAS setup, and the advanced signal processing capabilities of the U-net neural network for noise filtering. These elements combined ensure that the sensor can promptly and accurately detect changes in HCN concentration within 1 second. Moreover, when compared to conventional HCN sensors such as Ion mobility spectrometer, the compact form factor of the QEPAS sensor described herein is highlighted, offering significant advantages for the development of portable and miniaturized gas sensors. The compact size is achieved through the use of a clamp-type QTF and a dual-tube AmR, both of which are small in size. The high Q-factor of the QTF enhances sensitivity without requiring bulky components. Additionally, the sensor is designed for easy integration into handheld devices, facilitating real-time, on-site gas detection and monitoring. The low power consumption, supported by efficient acoustic coupling and advanced noise filtering techniques like the U-net neural network, further underscores its suitability for portable applications.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper introduced a novel clamp-type QTF with an on-beam AmR for QEPAS and demonstrated its superior performance in detecting hydrogen cyanide (HCN) gas. The innovative QEPAS sensor, utilizing the clamp-type QTF, exhibited enhanced sensitivity and a rapid response. Optimized through both theoretical and experimental approaches, the sensor achieved a substantial increase in photoacoustic signal amplitude, with an optimized AmR length of 4.1 mm. The inclusion of an EDFA and a neural network filtering method based on machine learning, known as the U-net significantly improved the detection SNR, achieving a minimum detection limit of 0.89 ppb and an NNEA coefficient of 2.31×10−9 W·cm−1·Hz−1/2. This performance enhancement was realized without saturation effects under a 3.3 W excitation laser, suggesting potential for further advancements with higher power outputs. The sensor’s efficiency, coupled with the cost-effectiveness of using commercial watch QTF, positions the clamp-type QTF as a viable solution for real-time HCN monitoring and indicates its potential for miniaturization in portable devices. The proposed QEPAS sensor system offers significant potential for miniaturization and portability due to its compact form factor, high Q-factor, and advanced noise filtering techniques, which collectively ensure high sensitivity, low power consumption, and easy integration into handheld devices for real-time, on-site gas detection and monitoring. This work not only contributes to the advancement of gas sensing technology but also opens avenues for broader applications in industrial safety and environmental monitoring. Further improvement can be made by using of novel light sources such as dual comb sources or high-power single-longitudinal-mode solid-state lasers [81], [82].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jianhui Yu: Conceptualization. Lihao Wang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yongchun Zhong: Conceptualization. Bin Liu: Conceptualization. Yaohong Zhao: Conceptualization. Chenglong Wang: Conceptualization. Huadan Zheng: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Haohua Lv: Data curation. Jiabao Xie: Conceptualization. Wenguo Zhu: Conceptualization. Huijian Luo: Conceptualization. Haoyang Lin: Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFB2800801), National Natural Science Foundation of China (62375111, 62005105, 12174156, 12174155, 62105125, 62075088, 62175137), the Ministry of Education of China (8091B03012309), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2020B1515020024, 2023B1515020027), the Science and Technology Projects of Guangzhou (202102020445), Special Project in Key Fields of the Higher Education Institutions of Guangdong Province (2020ZDZX3022), Open foundation of CEPREI (NO. 19D09), Foundation for Distinguished Young Talents in Higher Education of Guangdong (2018KQNCX009), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (21619402, 11618413, 21624113), State Key Laboratory of Applied Optics (SKLAO-201914). Special Funds for the Cultivation of Guangdong College Students' Scientific and Technological Innovation (NO. pdjh2023a0052, NO. pdjh2024a051, NO. pdjh2024a048), National Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for Undergraduate (NO. 202310559088, NO. 202410559001). Conflict of interest the authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Biographies

Lihao Wang received his bachelor’s degree in opto-electronics information science and engineering from Jinan University, China, in 2022. He is now pursuing a master’s degree in electronic information from the Department of Optoelectronic Engineering of Jinan University. His research interests include photoacoustic spectroscopy and optical gas sensors.

Haohua Lv received his bachelor’s degree in opto-electronics information science and engineering from Jinan University, China, in 2022. He is now pursuing a master’s degree in optical engineering from the Department of Optoelectronic Engineering of Jinan University. His research interests include photoacoustic spectroscopy and optical gas sensors.

Yaohong Zhao received his Ph.D. degree in chemical and molecular engineering from Peking University, China, in 2014. From 2014–2016, he studied as a joint postdoctoral in Xi'an Jiaotong University and Guangdong Power Grid Jointly Cultivate. Currently he is a supervisor in the Electric Power Scientific Research Institute of Guangdong Power Grid Corporation. His research interests include transformer oil applications.

Chenglong Wang received his bachelor’s degree on school of electrical and photoelectronic engineering in 2020 from West Anhui University, Anhui, China. He is now pursuing a master's degree in Department of Optoelectronic Engineering at Jinan University, China. His research interests include gas sensor, multi-pass cell, and photoacoustic spectroscopy.

Huijian Luo received his bachelor’s degree in opto-electronics information science and engineering from Jinan University, China, in 2022. He is now pursuing a master’s degree in optical engineering from the Department of Optoelectronic Engineering of Jinan University. His research interests include photoacoustic spectroscopy and optical gas sensors.

Haoyang Lin received his bachelor’s degree in opto-electronics information science and engineering from Jinan University, China, in 2021. He is now pursuing a master’s degree in optical engineering from the Department of Optoelectronic Engineering of Jinan University. His research interests include photoacoustic spectroscopy and optical gas sensors.

Jiabao Xie is now pursuing a bachelor’s degree in at Jinan University. His research interests include gas sensor, photoacoustic spectroscopy and laser spectroscopy.

Wenguo Zhu is now an associate professor in Department of Optoelectronic Engineering at Jinan University, China. He got both his Ph. D. degree on Optics in 2016 and his Bachelor’s degree on optical information in 2011 from Sun Yet-Sen University, China. His recent research interests include optical spin and orbital angular momentum, zero-index metamaterial, novel nano-photonic devices, and novel optical fibre sensors.

Yongchun Zhong received the Ph.D. degree in optics from Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China, in 2004. Then, he did postdoctoral research with the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology from 2004 to 2009. He is an associate professor with the Jinan University, Guangzhou, China. He has authored more than 30 journal papers. His current research interests include photonic crystal fiber devices, holography, and photoelectric material.

Bin Liu received her Ph.D. degree in theoretical physics from Shanxi University, China, in 2018. Currently she is an assistant professor in the department of physics of Foshan University. Her research interests include optical sensors and nonlinear optics.

Jianhui Yu is a professor in Department of Optoelectronic Engineering at Jinan University, China. He got both his Ph. D. degree on optical engineering in 2009 and his bachelor degree on physics in 2002 from Sun Yet-Sen University, China. His recent research interests include novel micro/nano fibre-based optical devices, all optical controllable devices, optical momentum in dielectric media and in waveguide, measurement and application of optical force, and novel optical fibre sensors.

Huadan Zheng received his Ph.D. degree in atomic and molecular physics from Shanxi University, China, in 2018. From 2016–2017, he studied as a joint Ph.D. student in the electrical and computer engineering department and rice quantum institute, Rice University, Houston, USA. Currently he is a tenured associate professor in the Department of Optoelectronic Engineering of Jinan University. His research interests include optical sensors and laser spectroscopy techniques.

Contributor Information

Jianhui Yu, Email: jianhuiyu@jnu.edu.cn.

Huadan Zheng, Email: zhenghuadan@jnu.edu.cn.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Hu Y.H., Hwang J.N. In: Handbook of neural network signal processing. Hu Y.H., Hwang J.N., editors. CRC press; Boca Raton: 2018. Introduction to neural networks for signal processing; p. 1. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng S., Li X., Zhang S., Jian Z., Duan H., Wang Z. A review: state estimation based on hybrid models of Kalman filter and neural network. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2023;11(1):2173682. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu K., Zhao W., Wang L., Tan T., Wang G., Zhang W., Gao X., Chen W. Quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy of HCN from 6433 to 6613 cm−1. Opt. Commun. 2015;340:126–130. [Google Scholar]

- 4.J. Taylor, Toxicological profile for cyanide, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2006. [PubMed]

- 5.NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards, “Hydrogen cyanide,” https:/www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0333..

- 6.Blank T.L., Roloff M.V., Short R.D., Schuengel S.M., Ribelin W.E. Inhalation toxicity studies of hydrogen cyanide (HCN) in spbague-dawley rats. Toxicol. Lett. 1983;18:136. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosterev A.A., Mosely T.S., Tittel F.K. Impact of humidity on quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy based detection of HCN. Appl. Phys. B. 2006;85:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong L., Kosterev A.A., Thomazy D., Tittel F.K. Compact portable QEPAS multi-gas sensor. Quantum Sens. Nanophotonic Devices VIII. 2011;7945 79450R. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosterev A.A., Tittel F.K., Bearman G. Advanced quartz-enhanced photoacoustic trace gas sensor for early fire detection. SAE Int. J. Aerosp. 2008;1(1):331–336. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keski-Rahkonen O., Mangs J. Tech. Res. Centre Fin; Espoo: 1999. Ignition of and fire spread on cables and electronic components; pp. 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alison A.C. Cyanide-smelling deficiency among africans. Man. 1953;53(11):176–177. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunter G.W., Xu J.C., Ward B., Makel D., Dutta P., Liu C.C. Miniaturized sensor systems for early fire detection in spacecraft. SAE Tech. Pap. 2009:11. 2009-01-2469. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lellouch E., Gurwell M., Butler B., Fouchet T., Lavvas P., Strobel D.F., Sicardy B., Moullet A., Moreno R., Bockelée-Morvan D., Biver N., Young L., Lis D., Stansberry J., Stern A., Weaver H., Young E., Zhu X., Boissier J. Detection of CO and HCN in Pluto’s atmosphere with ALMA. Icarus. 2017;286:289–307. [Google Scholar]

- 14.He Y., Ma Y., Tong Y., Yu X., Tittel F.K. HCN ppt-level detection based on a QEPAS sensor with amplified laser and a miniaturized 3D-printed photoacoustic detection channel. Opt. Express. 2018;26(8):9666–9675. doi: 10.1364/OE.26.009666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J., Chen W., Yu B. Recent progress on infrared photoacoustic spectroscopy techniques. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2011;46(6):440–471. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi H., Xu Y., Yang L., Zhao X., Li C., Guo M., Chen K. Detection of gaseous halocarbon refrigerants and extinguishing agent based on photoacoustic spectroscopy. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023;394 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trzpil W., Charensol J., Ayache D., Maurin N., Rousseau R., Vicet A., Bahriz M. A silicon micromechanical resonator with capacitive transduction for enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022;353 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Q., Wei Y., Li J. Simultaneous detection of multiple gases using multi-resonance photoacoustic spectroscopy. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022;369 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duquesnoy M., Aoust G., Melkonian J.M., Lévy R., Raybaut M., Godard A. Quartz enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy based on a custom quartz tuning fork. Sensors. 2019;19(6):1362. doi: 10.3390/s19061362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin H., Zheng H., Montano B.A.Z., Wu H., Giglio M., Sampaolo A., Patimisco P., Zhu W., Zhong Y., Dong L., Kan R., Yu J., Spagnolo V. Ppb-level gas detection using on-beam quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy based on a 28 kHz tuning fork. Photoacoustics. 2022;25 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2021.100321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei Q., Li B., Zhao B., Yang P. EC-QCL based photoacoustic spectroscopy for detection of SF6 decomposition components. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022;369 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng H., Liu Y., Lin H., Liu B., Gu X., Li D., Huang B., Wu Y., Dong L., Zhu W., Tang J., Guan H., Lu H., Zhong Y., Fang J., Luo Y., Zhang J., Yu J., Chen Z., Tittel F.K. Quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy employing pilot line manufactured custom tuning forks. Photoacoustics. 2020;17 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2019.100158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nidheesh V.R., Mohapatra A.K., Nayak R., Unnikrishnan V.K., Kartha V.B., Chidangil S. UV laser-based photoacoustic breath analysis for the diagnosis of respiratory diseases: Detection of Asthma. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022;370 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma Y., He Y., Yu X., Chen C., Sun R., Tittel F.K. HCl ppb-level detection based on QEPAS sensor using a low resonance frequency quartz tuning fork. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016;233:388–393. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lv H., Luo H., Zheng H., Zhu W., Fang J., Yu J., Tittel F.K., Chen Z. Application of piezoelectric transducers in photoacoustic spectroscopy for trace gas analysis. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2021;63(8):2040–2051. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huszár H., Pogány A., Bozóki Z., Mohácsi Á., Horváth L., Szabó G. Ammonia monitoring at ppb level using photoacoustic spectroscopy for environmental application. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2008;134(2):1027–1033. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J., Chen M., Chen Q., An Y., Feng Z., Wang H. Photoacoustic spectrometry and resonant frequency tracking based dual-mode gas sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023;390 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li T., Sima C., Ai Y., Tong C., Zhao J., Zhao Z., Lu P. Photoacoustic spectroscopy-based ppb-level multi-gas sensor using symmetric multi-resonant cavity photoacoustic cell. Photoacoustics. 2023;32 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2023.100526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu G., Wu X., Gong Z., Xing J., Fan Y., Ma J., Peng W., Yu Q., Mei L. Highly sensitive trace gas detection based on a miniaturized 3D-printed Y-type resonant photoacoustic cell. Opt. Express. 2023;31(21):34213–34223. doi: 10.1364/OE.502733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang G., Huang H., Luo H., Kou S., Amidi E., Achilefu S., Zhu Q. Fiber endface photoacoustic generator for quantitative photoacoustic tomography. Opt. Lett. 2021;46(11):2706–2709. doi: 10.1364/OL.426033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu L., Huan H., Mandelis A., Zhang L., Guo C., Li W., Zhang X., Yin X., Shao X., Wang D. Design and structural optimization of T-resonators for highly sensitive photoacoustic trace gas detection. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022;148 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chamassi K., Trzpil W., Arinero R., Rousseau R., Vicet A., Bahriz M. Capacitive silicon micro-electromechanical resonator for enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019;115(8) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menduni G., Zifarelli A., Kniazeva E., Russo S.D., Ranieri A.C., Ranieri E., Patimisco P., Sampaolo A., Giglio M., Manassero F., Dinuccio E., Provolo G., Wu H., Lei D., Spagnolo V. Measurement of methane, nitrous oxide and ammonia in atmosphere with a compact quartz-enhanced photoacoustic sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023;375 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo H., Yang Z., Zhuang R., Lv H., Wang C., Lin H., Zhang D., Zhu W., Zhong Y., Cao Y., Liu K., Kan R., Pan Y., Yu J., Zheng H. Ppbv-level mid-infrared photoacoustic sensor for mouth alcohol test after consuming lychee fruits. Photoacoustics. 2023;33 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2023.100559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russo S.D., Sampaolo A., Patimisco P., Menduni G., Giglio M., Hoelzl C., Passaro V.M.N., Wu H., Dong L., Spagnolo V. Quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy exploiting low-frequency tuning forks as a tool to measure the vibrational relaxation rate in gas species. Photoacoustics. 2021;21 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2020.100227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kosterev A.A., Bakhirkin Y.A., Curl R.F., Tittel F.K. Quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy. Opt. Lett. 2002;27(21):1902–1904. doi: 10.1364/ol.27.001902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma Y. Review of recent advances in QEPAS-based trace gas sensing. Appl. Sci. 2018;8(10):1822. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma Y., Liang T., Qiao S., Liu X., Lang Z. Highly Sensitive and fast hydrogen detection based on light-induced thermoelastic spectroscopy. Ultra Sci. 2023;3:0024. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mordmüller M., Köhring M., Schade W., Willer U. An electrically and optically cooperated QEPAS device for highly integrated gas sensors. Appl. Phys. B. 2015;119:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petra N., Zweck J., Kosterev A.A., Minkoff S.E., Thomazy D. Theoretical analysis of a quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy sensor. Appl. Phys. B. 2009;94:673–680. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gong P., Xie L., Qi X., Wang R. A QEPAS-based central wavelength stabilized diode laser for gas sensing. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2014;27(5):545–548. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hou J.F., Liu X.N., Liu Y.H., He Y., Zhao W., Ma Y. Highly sensitive CO2-LITES sensor based on a self-designed low-frequency quartz tuning fork and fiber-coupled MPC. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2024;22(7) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nie Q., Wang Z., Borri S., Natale P.D., Ren W. Mid-infrared swept cavity-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy using a quartz tuning fork. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023;123(5) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shang Z., Wu H., Li S., Wang G., Sampaolo A., Patimisco P., Spagnolo V., Dong L. Ppb-level mid-IR quartz-enhanced photoacoustic sensor for sarin simulant detection using a T-shaped tuning fork. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023;390 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen W., Qiao S., He Y., Zhu J., Wang K., Qi L., Zhou S., Xiao L., Ma Y. Mid-infrared all-fiber light-induced thermoelastic spectroscopy sensor based on hollow-core anti-resonant fiber. Photoacoustics. 2024;36 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2024.100594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rück T., Bierl R., Matysik F.M. NO2 trace gas monitoring in air using off-beam quartz enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy (QEPAS) and interference studies towards CO2, H2O and acoustic noise. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018;255:2462–2471. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y., Chang J., Lian J., Liu Z., Wang Q., Qin Z. Quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy with right-angle prism. Sensors. 2016;16(2):214. doi: 10.3390/s16020214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kosterev A.A., Bakhirkin Y.A., Tittel F.K. Ultrasensitive gas detection by quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy in the fundamental molecular absorption bands region. Appl. Phys. B. 2005;80:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lassen M., Lamard L., Feng Y., Peremans A., Petersen J.C. Off-axis quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy using a pulsed nanosecond mid-infrared optical parametric oscillator. Opt. Lett. 2016;41(17):4118–4121. doi: 10.1364/OL.41.004118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ge H., Kong W., Wang R., Zhao G., Ma W., Chen W., Wan F. Simple technique of coupling a diode laser into a linear power buildup cavity for Raman gas sensing. Opt. Lett. 2023;48(8):2186–2189. doi: 10.1364/OL.486417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu Q., Lv H., Lin L., Wu H., Giglio M., Zhu W., Zhong Y., Sampaolo A., Patimisco P., Dong L., Spagnolo V., Yu J., Zheng H. Clamp-type quartz tuning fork enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy. Opt. Lett. 2022;47(17):4556–4559. doi: 10.1364/OL.464334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dong L., Kosterev A.A., Thomazy D., Tittel F.K. QEPAS spectrophones: design, optimization, and performance. Appl. Phys. B. 2010;100:627–635. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu K., Guo X., Yi H., Chen W., Zhang W., Gao X. Off-beam quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy. Opt. Lett. 2009;34(10):1594–1596. doi: 10.1364/ol.34.001594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu L., Zheng C., Zheng J., Wang Y., Tittel F.K. Quartz tuning fork embedded off-beam quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy. Opt. Lett. 2019;44(10):2562–2565. doi: 10.1364/OL.44.002562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wan F., Wang R., Ge H., Kong W., Sun H., Wu H., Zhao G., Ma W., Chen W. Optical feedback frequency locking: impact of directly reflected field and responding strategies. Opt. Express. 2024;32(7):12428–12437. doi: 10.1364/OE.520346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patimisco P., Scamarcio G., Tittel F.K., Spagnolo V. Quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy: a review. Sensors. 2014;14(4):6165–6206. doi: 10.3390/s140406165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sampaolo A., Patimisco P., Dong L., Geras A., Scamarcio G., Starecki T., Tittel F.K., Spagnolo V. Quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy exploiting tuning fork overtone modes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;107(23) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng H., Dong L., Sampaolo A., Patimisco P., Ma W., Zhang L., Yin W., Xiao L., Spagnolo V., Jia S., Tittel F.K. Overtone resonance enhanced single-tube on-beam quartz enhanced photoacoustic spectrophone. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016;109(11) doi: 10.1364/OL.41.000978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patimisco P., Sampaolo A., Giglio M., Mackowiak V., Rossmadl H., Gross B., Cable A., Tittel F.K., Spagnolo V. Octupole electrode pattern for tuning forks vibrating at the first overtone mode in quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy. Opt. Lett. 2018;43(8):1854–1857. doi: 10.1364/OL.43.001854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hayden J., Giglio M., Sampaolo A., Spagnolo V., Lendl B. Mid-infrared intracavity quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy with pptv–Level sensitivity using a T-shaped custom tuning fork. Photoacoustics. 2022;25 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2022.100330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li S., Yuan Y., Shang Z., Yin X., Sampaolo A., Patimisco P., Spagnolo V., Dong L., Wu H. Ppb-level NH3 photoacoustic sensor combining a hammer-shaped tuning fork and a 9.55 µm quantum cascade laser. Photoacoustics. 2023;33 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2023.100557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang Z., Lin H., Montano B.A.Z., Zhu W., Zhong Y., Yuan B., Yu J., Kan R., Shao M., Zheng H. High-power near-infrared QEPAS sensor for ppb-level acetylene detection using a 28 kHz quartz tuning fork and 10 W EDFA. Opt. Express. 2022;30(4):6320–6331. doi: 10.1364/OE.449357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Y., Qiao S., Fang C., He Y., Sun H., Liu J., Ma Y. A highly sensitive LITES sensor based on a multi-pass cell with dense spot pattern and a novel quartz tuning fork with low frequency. Opto-Electron. Adv. 2024;7(3) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lang Z., Qiao S., Ma Y. Fabry–Perot-based phase demodulation of heterodyne light-induced thermoelastic spectroscopy. Light Adv. Manuf. 2023;4(3):233–242. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Y., Lin H., Montano B.A.Z., Zhu W., Zhong Y., Kan R., Yuan B., Yu J., Shao M., Zheng H. Integrated near-infrared QEPAS sensor based on a 28 kHz quartz tuning fork for online monitoring of CO2 in the greenhouse. Photoacoustics. 2022;25 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2022.100332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yin X., Wu H., Dong L., Li B., Ma W., Zhang L., Yin W., Xiao L., Jia S., Tittel F.K. Ppb-level SO2 photoacoustic sensors with a suppressed absorption–desorption effect by using a 7.41 μm external-cavity quantum cascade laser. ACS Sens. 2020;5(2):549–556. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.9b02448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gordon I.E., Rothman L.S., Hargreaves R.J., Hashemi R., Karlovets E.V., Skinner F.M., Conway E.K., Hill C., Kochanov R.V., Tan Y., Wcislo P., Finenko A.A., Nelson K., Bernath P.F., Brik M., Boudon V., Campargue A., Chance K.V., Coustenis A., Drouin B.J., Yurchenko S.N. The HITRAN2020 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2022;277 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu C., Wang G., Zhang C., Patimisco P., Cui R., Feng C., Sampaolo A., Spagnolo V., Dong L., Wu H. End-to-end methane gas detection algorithm based on transformer and multi-layer perceptro. Opt. Express. 2024;32(1):987–1002. doi: 10.1364/OE.511813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.D’Andrea E., Pagnotta S., Grifoni E., Lorenzetti G., Legnaioli S., Palleschi V., Lazzerini B. An artificial neural network approach to laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy quantitative analysis. Spectrochim. Acta Part B. 2014;99:52–58. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bocos-Bintintan V., Ratiu I.A. Fast sensing of hydrogen cyanide (Hcn) vapors using a hand-held ion mobility spectrometer with nonradioactive ionization source. Sensors. 2021;21(15):5045. doi: 10.3390/s21155045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh A., Dipak P., Iqbal A., Samadhiya A., Dwivedi S.K., Tiwari D.C., Tiwari R.K., Pandey K.N. Fast response and recovery polyaniline montmorillonite reduce graphene oxide polymer nanocomposite material for detection of hydrogen cyanide gas. Sci. Rep. 2023;13(1):8074. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-32151-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun M., Maqbool E., Han Z. Terahertz sensing with high sensitivity and substance identification capability using a novel High-quality resonance supported by a thin structured silicon film. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022;152 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alev O., Sarıca N., Özdemir O., Arslan L.Ç., Büyükköse S., Öztürk Z.Z. Cu-doped ZnO nanorods based QCM sensor for hazardous gases. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020;826 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Petruci J.F. da Silveira, Hauser P.C., Cardoso A.A. Colorimetric paper-based device for gaseous hydrogen cyanide quantification based on absorbance measurements. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018;268:392–397. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhong L., Li H., Wang S.L., Song Q.H. The sensing property of charge-transfer chemosensors tuned by acceptors for colorimetric and fluorometric detection of CN−/HCN in solutions and in gas phase. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018;266:703–709. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shi X., Zhao Z., Han Z. Highly sensitive and selective gas sensing using the defect mode of a compact terahertz photonic crystal cavity. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018;274:188–193. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghanekar S., Horn G.P., Kesler R.M., Rajasegar R., Yoo J., Lee T. Quantification of Elevated Hydrogen Cyanide (HCN) Concentration Typical in a Residential Fire Environment Using Mid-IR Tunable Diode Laser. Appl. Spectrosc. 2023;77(4):382–392. doi: 10.1177/00037028231152498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peltola J., Vainio M., Hieta T., Uotila J., Sinisalo S., Metsälä M., Siltanen M., Halonen L. High sensitivity trace gas detection by cantilever-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy using a mid-infrared continuous-wave optical parametric oscillator. Opt. Express. 2013;21(8):10240–10250. doi: 10.1364/OE.21.010240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Azhar M., Mandon J., Neerincx A.H., Liu Z., Mink J., Merkus P., Cristescu S.M., Harren F.J.M. A widely tunable, near-infrared laser-based trace gas sensor for hydrogen cyanide (HCN) detection in exhaled breath. Appl. Phys. B. 2017;123:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen W., Qiao S., He Y., Zhu J., Wang K., Xiao L., Ma Y. Quasi-distributed quartz enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy sensing based on hollow waveguide micropores. Opt. Lett. 2024;49(10):2765–2768. doi: 10.1364/OL.525188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Qiao S., He Y., Sun H., Patimisco P., Sampaolo A., Spagnolo V., Ma Y. Ultra-highly sensitive dual gases detection based on photoacoustic spectroscopy by exploiting a long-wave, high-power, wide-tunable, single-longitudinal-mode solid-state laser. Light Sci. Appl. 2024;13(1):100. doi: 10.1038/s41377-024-01459-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang J., Wu H., Sampaolo A., Patimisco P., Spagnolo V., Jia S., Dong L. Quartz-enhanced multiheterodyne resonant photoacoustic spectroscopy. Light Sci. Appl. 2024;13(1):77. doi: 10.1038/s41377-024-01425-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.