ABSTRACT

Influenza, COVID-19, tetanus, pertussis and hepatitis B pose increased risk for pregnant women and infants and could be mitigated by maternal immunization. In India Tetanus-diphtheria (Td) and COVID-19 vaccines are recommended during pregnancy, while influenza and tetanus-acellular pertussis-diphtheria (Tdap) vaccines are not. We conducted a multicenter study from November 2021 to June 2022 among pregnant women (n = 172) attending antenatal clinics in three public hospitals in West Bengal, to understand the factors that influence women’s decisions to get vaccinated during pregnancy. Questions assessed vaccination coverage, knowledge, intention and willingness to pay for influenza vaccine, and factors influencing decisions to get Td, influenza, and COVID-19 vaccines. 152/172 (88.4%) women were vaccinated with Td, 159/172 (93%) with COVID-19, 1/172 (0.6%) with influenza, and none with Tdap. 10/168 (6%) had received hepatitis B vaccine (HBV). Community health workers advice was crucial for Td uptake and, the belief of protection from COVID for COVID-19 vaccines. Most women were unaware about Tdap (96%), influenza (75%), and influenza severity during pregnancy and infancy (85%). None were advised for influenza vaccination by healthcare providers (HCP), albeit, 93% expressed willingness to take, and pay INR 100–300 (95% CI: ≤100 to 300–500) [$ 1.3–4.0 (95% CI: ≤1.3, 4–6.7)] for it. Vaccination on flexible dates and time, HCP’s recommendation, proximity to vaccination center, and husband’s support were most important for their vaccination decisions. Women were generally vaccine acceptors and had high uptake of vaccines included in the Universal Immunization Program (UIP). Inclusion of influenza, Tdap, and HBV into UIP may improve maternal vaccine uptake.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, hepatitis B, India, influenza, pertussis, pregnant women, tetanus, vaccination, vaccine acceptance

Plain Language Summary

Vaccinations during pregnancy protect mothers and babies from lethal infections from tetanus, influenza, COVID-19, pertussis, and hepatitis B. In India all pregnant women get tetanus (Td) vaccines, and during the pandemic, pregnant women got COVID-19 vaccines as part of the government program. We conducted a study among pregnant women attending three public hospitals in West Bengal, India, during the COVID-19 pandemic to understand the factors that influence women’s decisions to get vaccinated during pregnancy. We found that most pregnant women had gotten Td (88.4%) and COVID-19 (93%) vaccines; however, the uptake was low for influenza (0.6%), pertussis (0%), and hepatitis B vaccines (6%) which are all not available in government programs. Though the majority (92%) of women had not heard about influenza vaccines, once they learnt about them, 93% said they would get vaccinated and even pay for it. Vaccination at flexible times and their doctor’s advice were important in their decisions to get vaccinated. Our research builds the case to include influenza, pertussis, and hepatitis B vaccines in programs for pregnant women.

Introduction

Maternal immunization (MI) or vaccination of mothers during pregnancy has been recognized as an effective strategy in reducing maternal and infant morbidity and mortality from vaccine preventable diseases such as tetanus, influenza, pertussis, COVID-19 and hepatitis B.1–7 MI generates antibodies in mothers which get transferred via the placenta and through breast milk, protecting infants when they are at highest risk for infections.7

Tetanus, an acute neurotoxin-mediated disease, causes significant morbidity and mortality in neonates and pregnant women.8 Immunization during pregnancy with tetanus toxoid containing vaccines (TTCV) has played a key role in maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination (MNTE) globally. India achieved MNTE in 2015.9

Universal immunization program

The Universal Immunization Program (UIP) of India, one of the largest public health programs, vaccinates 30 million pregnant women and newborns each year.10 All pregnant women receive two doses of tetanus toxoid (TT), which was recently replaced with tetanus and diphtheria toxoid (Td) vaccine.11 Besides Td during pregnancy, there is no other vaccine included in UIP for adults.12 Although several medical societies have issued guidelines for adult immunization they have not been implemented as national policies.13

Maternal influenza in Indian context

Influenza virus infections cause significant illness and deaths among pregnant women and infants.14 Influenza infection increases risk of late pregnancy loss and mortality.4 Indian data indicates a high burden of influenza associated maternal and fetal complications. During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic a high maternal mortality (25%-75%) was observed in pregnant women.15 Clinical evidence demonstrates the safety and effectiveness of influenza immunization during pregnancy for both mothers and infants.16–19 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends pregnant women receive influenza vaccine during each pregnancy.20 The adoption of maternal influenza vaccines in national programs however has been delayed in many low-and middle-income countries.21–23 Some Indian states approved maternal influenza vaccination in 201524 and the Indian government in 201625 however it is not yet introduced in the UIP, so vaccine uptake is poor [0–12.8%].24,26,27

Infant pertussis in Indian context

Young infants (<2–3 month) are susceptible to serious pertussis disease (whooping cough). Immunization of mothers with pertussis containing vaccine [tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis, Tdap] prevents severe disease and hospitalizations in infants.5 In India, numerous cases of pertussis among infants have been documented since 2018.28–31 Pertussis immunity among unimmunized pregnant women is low (12.6%) in India,32 due to no national policy for pertussis immunization after the age of 5, and waning of whole cellular pertussis (wP) vaccine mediated immunity. Several countries and various global and Indian societies33 routinely recommend Tdap for pregnant women.12,34,35 However, this recommendation is not yet endorsed by the Indian government, and uptake is rare.36

COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination in Indian context

The first case of COVID-19 was detected in India on January 27, 2020,37 and on March 25 a nationwide lockdown was imposed. By June 8, phased re-opening was initiated when India had reached more than 250,000 documented cases with 7200 deaths. From the beginning of March 2021 until July 2021, India experienced a major epidemic from the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) that replaced the previous strains (Alpha and Kappa) with increased disease severity, requiring hospitalizations and overwhelming the healthcare system. The number of COVID-19 cases and deaths during the pandemic is much greater than the official Indian records due to limited testing capacities and underreporting of deaths from non-registration, incomplete COVID certification, labeling as chronic disease and non-medically attended deaths.38,39

COVID-19 causes serious complications in pregnant women including intensive care admissions, maternal deaths, preterm births, and neonatal morbidity.6 The data on maternal mortality in India is limited, although reports show the maternal mortality ratio increased 35.8% during the pandemic.40,41

Within a year of the pandemic, India launched its COVID-19 vaccination drive.42 Pregnant women were initially not prioritized due to a lack of safety data. However, observations of the delta variant causing adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes and the recommendations of the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization led to the emergency approval of COVID-19 vaccines on July 2, 2021.43,44 The Indian government approved two non-replicating viral vector (Oxford-Astrazeneca/Serum Institute of India and Sputnik-Gameleya V) and one inactivated viral vaccine (Bharat Biotech) for pregnant women.45 Vaccines were provided for free in government health centers and hospitals. Special immunization clinics were organized in antenatal clinics for pregnant women. By March 2023, 87.8% of the eligible population (>12 years) was fully vaccinated as recorded on CoWIN, the COVID-19 vaccination dashboard. Data on vaccination coverage of pregnant women is however unavailable on CoWIN. A report from a multi-country study showed low levels (12.9%) of maternal vaccination coverage in India.46

Hepatitis B vaccines and Indian context

Mother to child transmission (MTCT) is one of the leading causes of chronic hepatitis B. The majority of chronic infections occur by the age of 5.47 In India, around 30% of hepatitis B transmissions are vertical, posing a risk to 1 million infants out of the 26 million born each year who become carriers.48 Hepatitis B vaccines (HBV) were introduced in some states from 2002 to 2007 and expanded nationwide in 2011.49 All newborns are given four doses of HBV in the first year of life. The first dose is given at birth to prevent MTCT;50 however, its coverage has been low.29 Hepatitis B vaccines have recently been recommended for pregnant women in several countries to prevent perinatal transmission, but not yet in India.51,52

Vaccine acceptance

Vaccine hesitancy, the state of indecision and uncertainty about vaccination before making the decision to get vaccinated,53 can vary with the vaccine, context, and time. The WHO prioritized vaccine hesitancy as one of the leading threats to global health in 2019, which became more serious during the COVID-19 pandemic54 and led to a gap in utilization of routine childhood immunization services in India.55 A narrative review to understand the attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccine in Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh found hesitancy associated with insufficient information about vaccine side effects, concerns regarding vaccine safety and skepticism toward vaccine efficacy.56

Understanding the factors informing the decision making process for pregnant women is important for improving the acceptance and uptake of routine and pandemic vaccines. Little research exists on the factors influencing the vaccine uptake among pregnant women from eastern India. We conducted a cross-sectional study in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic, when COVID-19 vaccination was ongoing, to ascertain their knowledge and attitudes toward influenza and COVID-19, willingness to pay for influenza vaccines, and factors influencing the uptake of Td, COVID-19, influenza, and hepatitis B vaccines in a rural district of West Bengal.

Material and methods

Study area

We conducted a multicenter study with one hundred seventy-two pregnant women attending antenatal clinics at Kharagpur Sub Divisional Hospital (KSDH), South Eastern Railway Main Hospital (SERH), and, the Midnapore Medical College & Hospital (MMCH), in West Midnapore from November 10, 2021 to June 10, 2022. The sample size was arbitrary. All three hospitals are government-run public health institutions where care is free without deductibles. KSDH and MMCH are governed independently by the state government for the general public, although programs for maternal and antenatal care are governed jointly by the central and state government under the National Health Mission. SERH comes under the aegis of the central government health scheme for railway employees and their dependents.

KSDH is the secondary hospital in Kharagpur, catering to the Kharagpur Sub-Division catchment; MMCH is the tertiary level hospital in Midnapore; SERH is a secondary hospital in Kharagpur. KSDH caters to a population of 2.3 million and MMCH caters to nearly 1.4 million, which is equivalent to 78% of the population of the whole district. The catchment of SERH is limited to railway beneficiaries, which is about 180,000. The catchment of KSDH is semi-urban and rural; largely semi-urban for SERH; and rural for MMCH. The geographic location of study participants was plotted using Quantum GIS software.

Study design and inclusion criteria

The study followed an embedded mixed-methods research design involving individual face-to-face interviews by two trained social workers in each of the three study sites in Bengali or Hindi, in private, in the antenatal clinic lasting 15–20 minutes. Clinics were planned once to twice per week. From January 1 to February 13, 2022 interviews were halted due to the Omicron wave. All pregnant women presenting to the three hospitals for antenatal care, regardless of their age and gestation were eligible. Subject recruitment followed a non-probability purposive sampling method. The written informed consent process was led by the social workers. Participation was voluntary and did not involve payment. N95 masks were given to participants.

Data collection tool

A semi-structured interview guide was developed for measuring vaccine hesitancy.57–60 The questionnaire was translated into Bengali targeting a class 5 reading level, field-tested, edited, and validated with 25 native Bengali speakers. The questionnaire consisted of six sections with 90 questions that included eighty-two quantitative and eight qualitative open-ended questions.

Questions covered the following six components:

Socio-demographics: Eighteen questions covered individual and family socio-demographic characteristics. Socioeconomic status was measured using the Kuppuswamy Socioeconomic Scale 2021.61

Antenatal health behavior, vaccination history, and decision making: Nineteen questions covered antenatal health behavior, vaccination history and decision making. Questions included number of visits to the ANC facility, number of iron/folic acid supplements consumed, and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) screening. Access to ANC was measured by asking the distance, time, and cost to reach the health facility. Vaccination status was measured by asking if the participants were vaccinated and with how many doses, and the reasons for taking or not taking Td. Data on Td vaccination, HBsAg testing, and the number of antenatal visits were cross-checked with the written records in their mother and child cards and clinic records. Mothers were asked if their child received vaccines that are not part of the government immunization program by paying out-of-pocket. Two questions assessed their decision making: (1) how difficult their decision making is; and (2) who makes decisions about their vaccination.

Knowledge and beliefs towards maternal immunization, influenza, and intention for influenza vaccines: For assessing awareness and attitudes toward maternal immunization, influenza, and vaccines, we used five open-ended questions. For vaccine intention, they were asked if they would like to get the influenza vaccine in the current pregnancy and the reason why they would like or not like to get vaccinated. For willingness to pay for influenza vaccine, they were given eight options ranging from INR 100 to INR 1500–2000 ($1.3 to $20.0–26.7).

Contextual factors: Nine questions covered their trust in government, pharmaceutical industry, news and information about vaccines, their past experience with vaccination, and health care professionals, sources they rely most for vaccine-related information, and who they turn to for vaccination advice.

Knowledge and individual beliefs towards COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines: Six questions covered their understanding about COVID-19, awareness about COVID-19 symptoms and spread, and their pandemic and disease experience. For measuring attitudes toward COVID-19, we utilized a scale based on the Health Belief Model62 having 13-items to assess their perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, benefits, safety, and barriers, with a Cronbach alpha statistic of 0.69. The responses were in a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), asked using visual prompts. Vaccination status was measured by asking if the participants were vaccinated and the reasons for taking or not taking COVID-19 vaccine.

Factors influencing vaccination decision: For measuring who they think is most important for their vaccination decision making, we used a thirteen-item scale with Cronbach alpha of 0.83. The responses were in a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 5 (most important), asked using visual prompts.

Data analysis

The responses were entered into an EpiInfo databaseTM version 7.2.4.0. Only study members had access to the data. For the open-ended questions, a team of three people identified and manually developed the themes individually, and then the emerging themes were refined with discussion. The data was analyzed using STATA/BE V.17.0 (STATA Corp, Texas, USA). Internal reliability of the instrument was measured using Cronbach alpha statistic. Continuous variables were presented as median (interquartile range) and categorical data as number, n (percentage, %). Categorical variables were assessed by chi-squared test and bivariate logistic regression, while continuous variables by Wilcoxon rank-sum test and ordinal logistic regression. Likert scale responses were recoded as disagree (those who strongly disagree and disagree, Likert scale 1–2); neutral (those who neither agree nor disagree, Likert scale 3); and agree (those who agree and strongly disagree, Likert scale 4–5). Similarly, scale questions were recoded as not important, neutral, and important.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institute Ethical Committee of Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur (#IIT/SRIC/DeanSRIC/2021) and the Institutional Ethics Committee of Midnapore Medical College (#IEC/2021/02). Approvals were obtained from medical superintendents of the three hospitals, and the district (#1655) and state health department (#SS(ME)/Spl./184/2021).

Results

Individual and family background

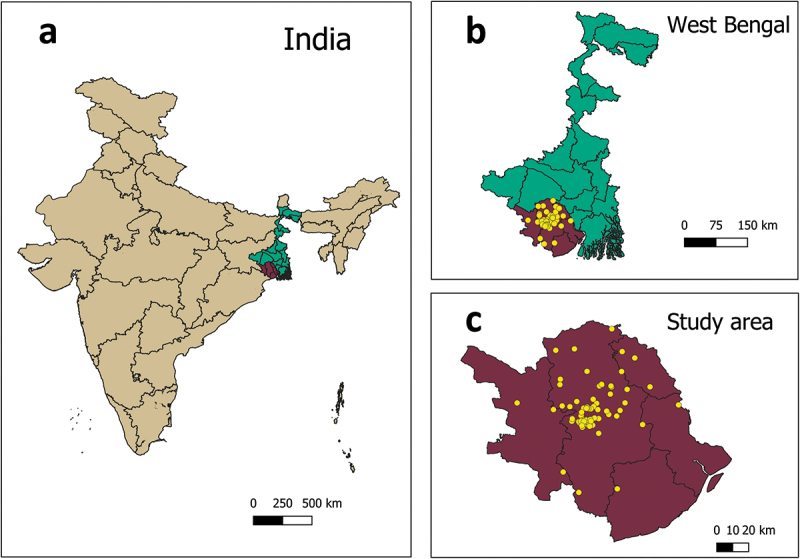

Table 1 displays the individual and family socio-demographic characteristics of study participants. In all, one hundred seventy-two pregnant women were interviewed at KSDH (n = 65), MMCH (n = 66), and SERH (n = 41). The majority of participants (164/172; 95%) were from District West Midnapore and a small number were from nearby districts (Jhargram, East Midnapore, Hooghly, Howrah) (Figure 1). Around 48% (83/172) were pregnant for the first time. Half of them 85/171 (50%) were in their third trimester, 67/171 (or 39%) were in the second, and 19/171 (11%) in the first. Approximately 12% (9/73) of women who were already parents had previously paid for their child vaccinations out-of-pocket, outside of the national immunization program.

Table 1.

Individual and family socio-demographic characteristics of study participants.

| Category | Variables | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | N | 172 (100) |

| Age (years) (N = 172) | ≤25 | 111 (64.5) |

| >25 | 61 (35) | |

| Education, (N = 171) | None | 13 (7.6) |

| Primary (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8) | 34 (20) | |

| Secondary (9,10,11,12) | 81 (47.4) | |

| Tertiary & above | 43 (25.1) | |

| Education of spouse, (N = 171) | None | 13 (8) |

| Primary (1,2,3,4,5,6 7,8) | 77 (45) | |

| Secondary (9,10,11,12) | 49 (29) | |

| Tertiary & above | 32 (19) | |

| Occupation (N = 172) | Housewife | 150 (87) |

| Working | 22 (13) | |

| Faith (N = 172) | Hindu | 120 (70) |

| Muslim | 52 (30) | |

| Months of gestation, (N = 171) | 0–3 | 19 (11) |

| 4–6 | 67 (39) | |

| 7–9 | 85 (50) | |

| Number of pregnancies (N = 172) | 0 (gravida 1) | 83 (48) |

| 1 (gravida 2) | 57 (57) | |

| 2 (gravida 3) | 28 (16) | |

| 3 or more | 4 (2) | |

| Number of children (N = 172) | 0 | 94 (55) |

| 1 | 64 (37) | |

| 2 or more | 14 (8) | |

| Number of family members (N = 172) | 1 | 1 (0.6) |

| 2 | 22 (13) | |

| 3 | 38 (22) | |

| 4 | 46 (27) | |

| >4 | 65 (38) | |

| Number of rooms, (N = 171) | 1 | 45 (26) |

| 2 | 56 (33) | |

| 3 | 26 (15) | |

| 4 or more | 44 (26) | |

| Family monthly income**, INR (N = 171) | >46129 | 17 (10) |

| 30,831–46,128 | 21 (12) | |

| 18,497–30,830 | 13 (7.6) | |

| 6175–18,496 | 95 (56) | |

| ≤6174 | 25 (15) | |

| Socioeconomic status of family** (N = 171) | Upper | 1 (0.6) |

| Upper middle | 41 (24) | |

| Lower middle | 34 (20) | |

| Upper lower | 91 (53) | |

| Lower | 4 (2) |

*p values were calculated using Pearson’s chi-squared test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test; **Kuppuswamy socioeconomic scale 2021.

Figure 1.

Geographic location of study participants.

The study was conducted in district West Midnapore of state West Bengal located in eastern India. The yellow dots show the location of study participants coming from West Midnapore and neighboring districts (in the right bottom).

The age distribution was 16 to 35 years, with a median age of 23 (20, 28) years. Overall, the median education of participants was higher than that of their spouse [10 (8, 13) versus 4 (2, 4)]. The majority were housewives (86.6%) and from Hindu faith (70%). The proportion of Muslims in SERH was lower than that of MMCH or KSDH [(3/41 (7%) versus 49/131 (37%); p=<.001).

More than half (55%) were from upper-lower socioeconomic backgrounds (53%; 91/171) and hailed from households earning INR 6175–18496 per month ($74–$222; 1 USD = INR 83.2).

Utilization of antenatal care services

Supplementary Table S1 describes the utilization of antenatal care (ANC) services by study participants. The majority 148/158 (94%) had the mother and child protection card. The median number of ANC visits were 4 (2, 5). Women were provided iron and folic acid (IFA) supplements for free as part of ANC and almost 90% of participants took the IFA supplementation. Interestingly, 42% of third-trimester participants had consumed fewer than 100 IFA tablets. Only 79/167 (47%) underwent HBsAg screening, and all them came out HBsAg negative. They traveled to the ANC clinic in a median of 30 minutes (iqr: 20, 42.5), and each visit cost INR 50 (40, 100) in transport expenses.

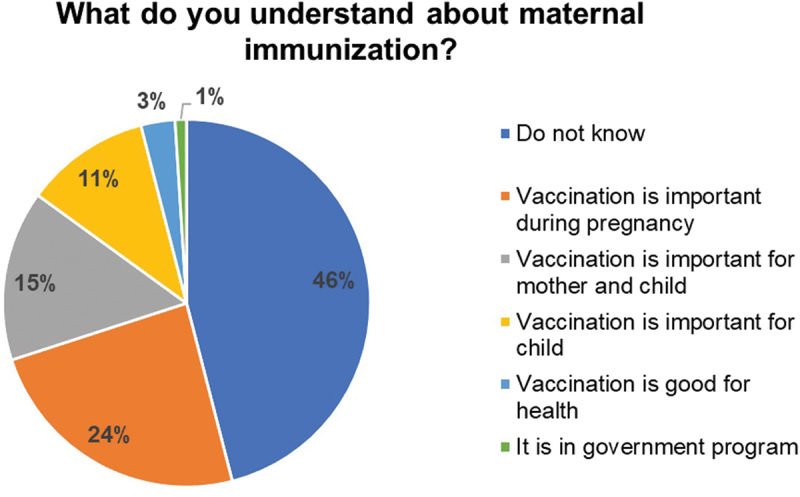

Awareness about maternal immunization

As shown in Figure 2, less than half of the women, 79/172 (46%) did not have an understanding of the principles of maternal immunization. Of those who were aware, the majority said that “vaccination is very important during pregnancy” 41/172 (24%), or that “vaccination is important for mother and child” 25/172 (14.5%). Of the others, 19/172 (11%) said “vaccination is important for child,” 5/172 (3%) said that “vaccination is good for health” and 1/172 (0.6%) cited it “as the government program.”

Figure 2.

Participants’ understanding about maternal immunization, N = 172.

Key responses recorded by the study participants on their understanding about maternal immunization. The pie chart represents the percent responses.

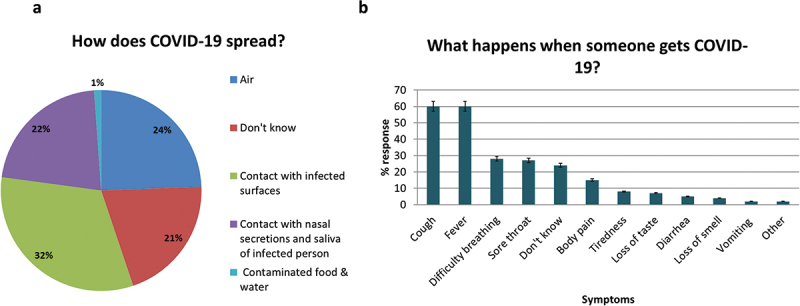

Awareness about COVID-19

After two years of COVID-19 pandemic, 26/172 (15%) were not sure what COVID-19 is. A minority (3%) thought it was a myth, while the majority (83%) believed it was a disease.

Figure 3 shows the participants’ awareness about COVID-19. Almost 31% of the women (52/170) did not know how COVID-19 spreads; the rest believed it spreads through infected surfaces 84/170 (49%), air 63/170 (37%) and nasal secretions 57/170 (33%). The most commonly reported symptoms for COVID-19 were fever (60%), cough (60%), sore throat (27%) and difficulty breathing (28%); while nearly one-fourth (42/172) did not know. The majority 158/172 (92%) did not believe the pandemic impaired their routine ANC services.

Figure 3.

COVID-19 awareness among study participants.

(a). Awareness about the modes of transmission of COVID-19, n = 170. The pie chart represents the percent responses; (b). Awareness about the symptoms during COVID-19, n = 172. The bars represent the percent responses.

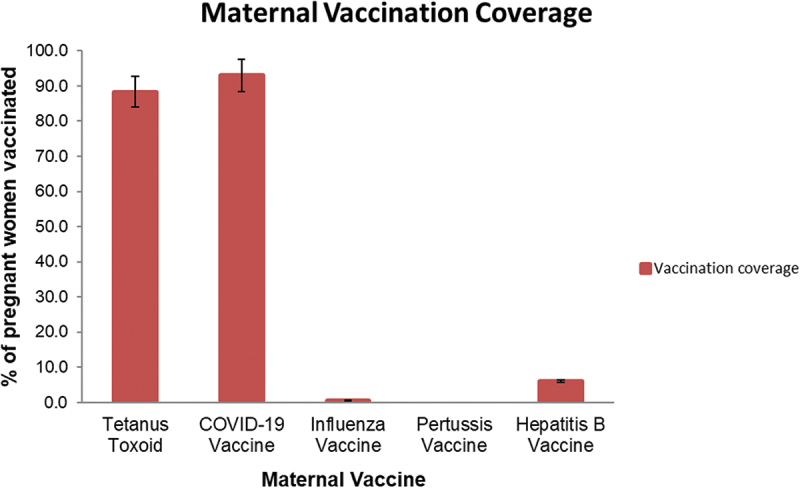

Maternal immunization coverage

Immunization coverage of study participants is presented in Figure 4. The majority, 152/172 (88.4%) had received Td during pregnancy. This included 120/172 (69.7%) who received two doses, and 32/172 (18.6%) who received just one. The majority, 159/171 (93%) reported receiving COVID-19 vaccine.

Figure 4.

Vaccination status of study participants.

Vaccination status of study participants for maternal vaccines, n = 172. The bars represent the percent vaccination for individual vaccines. The first and second dose of TT and COVID-19 vaccination are depicted in a combined format.

Only 10 of 168 (6%) reported receiving hepatitis B vaccine in the past, with the majority coming from SERH (9/10). Only 1/172 (0.6%) woman had received influenza vaccine. None of them had received Tdap.

Factors influencing the uptake of maternal tetanus-diphtheria and COVID-19 vaccine

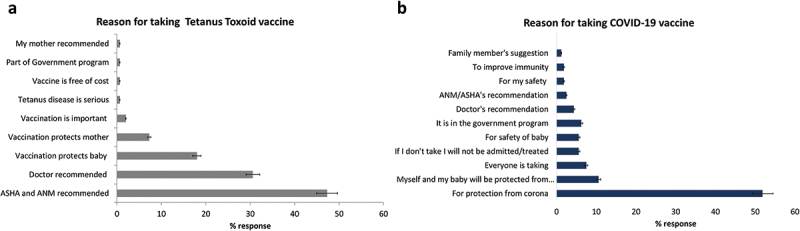

The most common reasons given by participants for receiving Td were the vaccination advice of auxiliary nurse midwives (ANM)/Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers (71/150, 47%), or the doctors’ recommendation (46/150, 31%). The rest obtained Td because they believed that vaccines would protect their baby (27/150, 18%) or the mothers (11/150, 7%), see Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

Reasons for taking tetanus toxoid vaccine and COVID-19 vaccine.

(a) Major reasons reported by the study participants for taking tetanus toxoid vaccine, n = 150, and, (b) Major reasons reported by the study participants for taking COVID-19 vaccine, n = 159. The bars represent the percent responses.

The key reasons for not taking Td were their ineligibility owing to early pregnancy (4/19, 21%), or having a recent card (3/19, 16%). Some had vaccinations scheduled for later dates (3/19, 16%).

Compared to their reasons for receiving the Td vaccine, the study participants were more aware about the importance of COVID-19 vaccination. More than half of them, 83/159 (52%) reported receiving the vaccine to protect them from “corona” infection. Some 17/159 (11%) believed that the baby and mother would be protected from corona, while 12/159 (8%) said that because everyone is taking, I am also taking, see Figure 5b. Interestingly, 9/159 (6%) received the vaccine for fear of not being treated, or not being allowed for institutional delivery, or fearing social discrimination, suggesting the impact of vaccine mandate.

The primary reason for not receiving COVID-19 vaccine was their pregnancy and fear of adverse effects (5/13). Others stated that their spouse didn’t support (1/13), that their doctor did not recommend (1/13), that their family or doctor advised them to take after delivery (1 each), or that they planned to take after discussion at home or after delivery (1 each).

Health belief model domains for the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine

The individual attitudes toward COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines are presented in Table 2. Despite the high uptake of COVID-19 vaccine, their awareness about disease risk and severity was low. More than three-fourth (78%) did not perceive themselves to be at risk of COVID-19; 67% did not worry about COVID-19; 43% did not believe they may become sick with COVID-19, and 28% were neutral. Less than half of them, 44%, believed that if they contracted COVID-19 their baby could become ill.

Table 2.

Individual attitudes toward COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines based on the Health Belief Model Theory.

| HBM Construct |

Item |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neither Disagree nor Agree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

Cronbach alpha |

| n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

||

| Fear | I worry about COVID-19. | 97 (56) | 19 (11) | 27 (16) | 14 (8) | 15 (9) | 0.668 |

| Risk | I am at risk of getting COVID-19 | 105 (61) | 29 (17) | 28 (16) | 9 (5) | 1 (0.58) | 0.6655 |

| Severity | If I get infected with COVID-19, I could get very ill | 57 (33) | 18 (10) | 48 (28) | 29(17) | 20 (12) | 0.6476 |

| If I get infected with COVID-19, my baby could get ill | 32 (19) | 15 (9) | 50 (29) | 43 (25) | 32 (19) | 0.68 | |

| If I get infected with COVID-19, my other family members could also get ill | 30 (17) | 15 (9) | 49 (29) | 51 (30) | 27 (16) | 0.6759 | |

| Benefits | If I take the vaccine, I will be protected from COVID-19. | 14 (8) | 5 (3) | 49 (29) | 34 (20) | 70 (41) | 0.6634 |

| If I take the vaccine, my baby will be protected from COVID-19 | 7 (4) | 4 (2) | 33 (19) | 47 (27) | 81 (47) | 0.6479 | |

| If I take the vaccine, my other family members could also be protected from COVID-19 | 6 (4) | 5 (3) | 40 (23) | 42 (24) | 79 (46) | 0.6524 | |

| Safety | If I take the COVID-19 vaccine, it could hurt me and my baby | 116 (67) | 37 (22) | 11 (6) | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 0.68 |

| Barrier | I fear injections | 88 (51) | 7 (4) | 31 (18) | 13 (8) | 33 (19) | 0.7051 |

| Vaccination is not important | 56 (33) | 18(10) | 12(7) | 7 (4) | 79 (46) | 0.6988 | |

| Vaccination lines are very long | 72 (42) | 32 (19) | 16 (9) | 20 (12) | 32 (19) | 0.6738 | |

| Vaccine do not work against COVID-19 | 97 (56) | 28 (16) | 23 (13) | 11 (6) | 13 (8) | 0.6667 |

Despite their low awareness about the disease, they believed in the benefits of COVID-19 vaccine. Around 6 out of 10 women (60%) agreed that vaccination would protect them from COVID-19, and 74.4% agreed that their baby would be protected by maternal vaccination. The majority (88.5%) trusted that COVID-19 vaccine was safe for their baby. Regarding barriers, half of them (50%) thought vaccination was not important, 30% reported long vaccination queues, and 26.7% feared injections. Of those who refused COVID-19 vaccine, the majority thought that vaccination was not important as compared to those who accepted (10/13 vs. 76/159; p = <.05).

Awareness about Tdap, influenza, and acceptance and willingness to pay (WTP) for influenza vaccines

Overall, there was very low awareness about Tdap vaccine. Most of the participants 165/172 (96%) had not heard about Tdap. Three-fourth (129/172) of the women had never heard of “influenza” before. When questioned about the seriousness of influenza, 157 (91%) did not know, with only 12 (7%) believing it was very serious.

A good number of participants, 146 (85%) did not know that pregnant women can become sick with influenza, 20 (11.6%) believed it would make them very sick, while six (3.5%) disagreed. The majority (144; 84%) were unaware that influenza can cause serious illness in infants; 24 (14%) agreed that it would make infants sick, while four failed to agree.

The majority (159/172; 92%) were not aware that a vaccine is available for influenza; 167 (97%) had not heard about the influenza vaccine recommendation for pregnant women by the government. The majority (170; 98.8%) had not received maternal influenza vaccine recommendations from a healthcare provider.

Despite their low awareness, when asked “Now that you have heard would you like to take influenza vaccine during this pregnancy”, 164/171 (96%) were willing to take, three (2%) were unsure, and four (2%) refused. Their willingness was not related with their “influenza” awareness (p = .06) or their belief in influenza severity in mothers and babies (p > .05).

The primary reasons for their willingness to receive influenza vaccine were the belief that their baby would be safe and healthy 109/164 (66%), that the vaccine would save them (15/164; 9%), or both the mom and baby would be healthy (10/164; 6%). The rest would take if doctor recommended it (7/164; 4%) or to prevent catching cold (5/164; 3%). Few said they would take if the government offers (4/164; 2.4%). Four participants refused because they were afraid that their family would not give permission, they were afraid of side effects, they planned to take it after birth, or their doctor had not advised it. Two that were hesitant stated that they would have to discuss with their family first before making any decision.

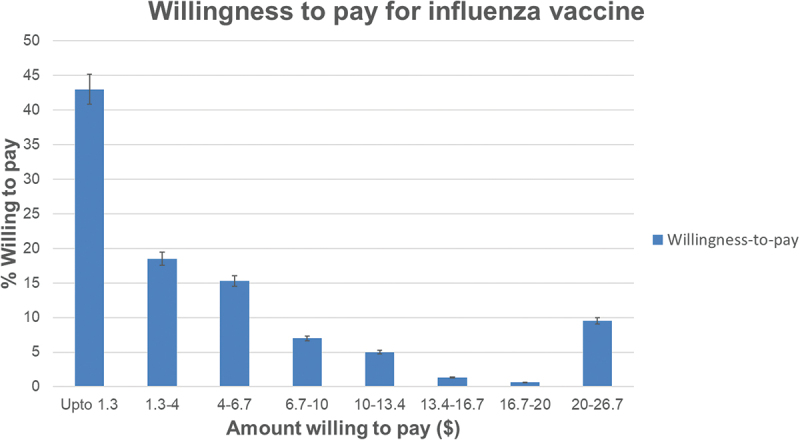

The majority (157/164; 96%) were willing to pay for influenza vaccination out-of-pocket for a median of INR 100–300 (95% CI: ≤100 to 300–500) ($1.3–4.0, 95% CI: ≤1.3 to 4–6.7), see Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Willingness-to-pay for influenza vaccination by the study participants in USD, n = 157 the bars represent the percent responses for their willingness-to-pay for one dose of influenza vaccine starting from upto 1.3 USD to 20–26.7 USD.

Decision making on maternal immunization

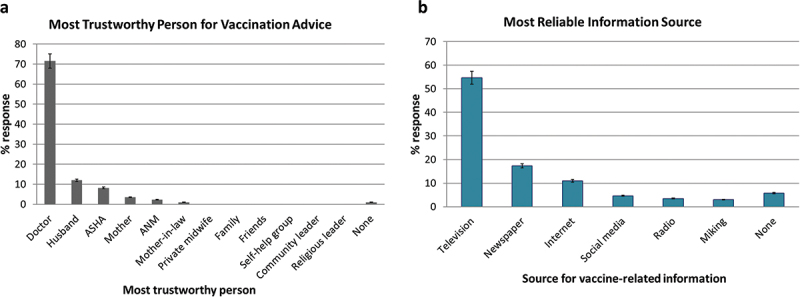

For 95% of study participants the decision making on maternal vaccination was easy. The decision was their own for 89%, their husband for 6%, and the entire family for 4%. Television 94 (54.6%), newspapers 30 (17%), and the internet 19 (11%) were the most reliable sources of vaccine information, followed by social media (4.6%) (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Trust.

Study participants were asked for who they trust most for vaccination advice and the sources they rely most for vaccine-related information. (a) The percent wise response for the most trustworthy person for advice related to vaccines and, (b) the most reliable information source regarding vaccines (b). The bars represent the percent responses.

Doctors were the most trusted source of vaccination advice among the study participants (71.5%; 123/172), followed by husbands (12%; 21/172), ASHA workers (8.1%; 14/172) and mothers (3.5%; 6/172) (Figure 7b).

The majority (93%) trusted the government recommendations for vaccination; 72% believed that pharmaceutical companies provided safe and effective vaccines, while 23% were neutral. Almost all (99%) had no previous negative experience with immunizations and had not experienced ill-treatment by health care professionals. Of note, 45% thought that in general news and information about disease and vaccines were sometimes true, whereas 5% thought they were seldom true.

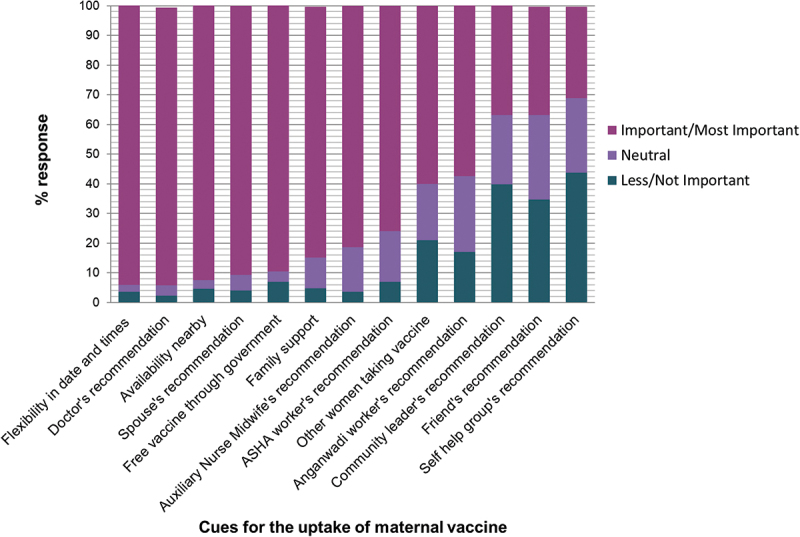

Cues to action for vaccine uptake

Figure 8 depicts the factors that were most important for vaccination decision. The cues for uptake of maternal vaccines were vaccine availability on flexible days and times (94.3%), doctor’s recommendation (93.5%), vaccine access nearby (92.7%), spouse support (91%), free vaccines from the government (90%), advice of family (84.4%), ANM (81.4%) and ASHA workers (76%).

Figure 8.

Cues for maternal vaccine uptake, n = 172.

Study participants were asked who they think was most important for their vaccination decision. The responses were measured in a 5 point likert scale ranging from choice 1 (not important) to choice 5 (most important). The bars represent the percent responses for not important or less important (1, 2) combined, neutral (3) and important or most important (4, 5).

Factors influencing maternal vaccine uptake and willingness

Td uptake was associated with advanced stage of pregnancy (p = <.001). COVID-19 vaccination was correlated with higher maternal education (p = .03). We did not find any significant association between the uptake of Td/COVID-19 vaccine and various risk factors such as age, religion, maternal occupation, number of pregnancies, number of children, number of rooms at home, family income, socioeconomic status or the hospital they visited, see Supplementary Table S2.

Discussion

This study examined the factors influencing vaccination decisions of pregnant women from a rural district in eastern India from the perspectives of socio-demographics, individual awareness, beliefs, inter-personal influences and contextual factors. This study revealed the representation of Muslims in railway jobs was overwhelmingly low (7%) as compared to Hindus. This aligns with the reports of poor representation (4.5%) of Muslims in Indian railways,63 and also in other formal jobs.64 However, this study did not find significant faith-related differences in maternal tetanus and COVID-19 vaccine uptake and influenza vaccine intention, unlike other Indian studies.65

Introduction and implementation of vaccines at a national level is a prerequisite for improving vaccination rates and reducing morbidity and mortality in pregnant women and children.66 This study revealed a high coverage of tetanus-diphtheria and COVID-19 vaccines, all administered within the framework of the national program and antenatal care.67 However, influenza vaccination coverage was notably deficient and Tdap non-existent, both of which are not yet integrated into the national program. Similar trends are observed in most LMICs where the inclusion of influenza and Tdap in national programs has not been implemented.66

Studies from Gambia, Senegal, and Pakistan emphasize the vitality of community health workers in promoting tetanus immunizations among pregnant women in agreement with our findings.68,69 Coming from the same community fosters trust and improves access for women to the health system.

Acceptance for COVID-19 vaccines and their determinants has been observed to vary with the stage of pandemic and country of residence. This study was conducted when COVID-19 vaccines were being offered to pregnant women in India. In contrast to our findings, globally COVID-19 vaccination rates have been low, 27.5% (95% CI: 18.8–37.0%) among pregnant women.70 Studies from India however report a higher uptake (64.4%-66.8%).71,72 Even before the vaccine approval, a multi-national survey conducted in sixteen countries demonstrated that assuming 90% COVID-19 vaccine efficacy the willingness for COVID-19 vaccine was highest among pregnant women from India (>80%) and Mexico, but lower in high-income nations like the USA, Russia, and Australia (45%).73 Other studies revealed an intention of 37% in Turkey,74 44.3% in the USA,75 60.4% in Vietnam,76 93.7% in Saudi Arabia77 and 78.5% from India.65

A review of eleven studies on COVID-19 vaccine uptake among pregnant women suggested trust in vaccine, fear of COVID-19 during pregnancy, older age, ethnicity, and race as the key predictors for vaccination.70 Similarly, in our study the strongest reason for vaccine uptake was protection from COVID-19.70,73 This suggests that the pandemic created awareness among the public and increased the vaccine demand. Further, vaccination integrated in the government program was crucial.65 COVID-19 vaccination camps were organized close to their homes, and ASHAs coordinated vaccination visits. High uptake could also be attributed to their strong trust in government (93% trusted), as mistrust in government has been globally seen to be associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women.70,73

In alignment with our findings other Indian studies have reported low awareness about influenza (8%) and influenza vaccines (2%) among pregnant women.24 In addition, the uptake of influenza vaccine among pregnant women in India has been seen to be almost non-existent in the past [Nagpur (1% in 2017) and Kashmir (0% in 2012–2013)].24,26 Interestingly, even in high-income countries like the USA, UK and the European nations where flu vaccines are offered to pregnant women, the uptake is disappointing.78–80 This is primarily due to vaccine hesitancy regarding the concerns about safety of vaccines, potential harm to the fetus, and limited awareness about the severity of disease and benefits of vaccination.

Vaccine recommendation by providers is a major driving force for influenza and Tdap vaccine uptake in pregnant women in various situations.81,82 An Indian study on obstetricians reported the barriers to Tdap recommendation related to non-affordability, non-inclusion in the immunization program, lack of awareness, and non-availability.36

In Thailand only one-fourth of clinicians recommended influenza vaccine to pregnant women, despite having a national policy.83 Similarly Maharashtra offered influenza vaccines through ANC program for free in 2015 based on the mortality data from the state, however the uptake remained poor (<5%), mainly due to a lack of providers’ recommendation.24 This hesitancy in recommending vaccines by providers could be associated with their low risk perception about maternal influenza and lack of a national policy.26–27,83–86 It is interesting to note that influenza vaccination is not a mandate even for health workers in India and vaccine uptake is thus rare.87 Therefore, a vaccine policy, sensitization of providers, and addressing their concerns is essential to improve maternal and HCP’s vaccine uptake.27,65,81,86,88

The positive message from this study was that the majority of women had intention to receive and even pay for influenza vaccines despite the high vaccine cost and their lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Similar high intentions were observed in Pakistan.89 In Pakistan, similar to our findings fear of vaccine harm and the absence of family decision maker was associated with influenza vaccine refusal,89 underscoring the importance of conversations with family in vaccination decisions.89 Overall, it can be concluded that maternal vaccination decisions are influenced by individual awareness, attitudes toward vaccines, support of partners and family, provider’s recommendation, and vaccine policy. These findings align with studies from Bangladesh on COVID-19 vaccination.90

Following the outbreaks of COVID-19, Ebola, and Lassa fever that demonstrated disproportionate disease severity in pregnant women, there has been a renewed interest in maternal immunization.91 Very recently, hepatitis B vaccines were recommended for pregnant women. Pneumococcal, meningococcal and hepatitis A vaccines are recommended in high-risk pregnant women.52 We observed very low hepatitis B vaccination coverage, although hepatitis B transmissions are predominantly vertical in India.92 Screening for HBsAg in pregnant individuals is important for timely treatment for hepatitis B and for prevention of transmission to neonates. The low levels of HBsAg screening observed in this study warrants the need for testing of all women entering pregnancy.

Strengths and limitations

This study gave the holistic picture of pregnant women in a rural district of West Bengal by looking into their socio-demographic structure, beliefs, and health behaviors. The inclusion of open-ended questions gave profound insights into their attitudes and reasons for vaccine acceptance or refusal. Further, questions on contextual factors and the decision making process shed light into their beliefs and past experiences. The study was unique as it was conducted in three different hospitals and involved face-to-face interviews, contrary to surveys. The study was able to determine the actual vaccination rates of COVID-19 vaccines, as opposed to intention.

The limitations of the study are its small sample size restricted to one district and the fact that participants were recruited in health centers, which may limit the generalizability of results to the whole population. However, since we included multiple hospitals which account for the majority of deliveries in the two subdivisions, vaccination behaviors would be representative. There is a sampling bias since the study focused on women who were already seeking antenatal care and might be more inclined to accept vaccines. We may have missed those women who were not seeking antenatal care and might be vaccine hesitant. Furthermore, the study did not capture data from women seeking care in private clinics, where the HCP’s vaccine recommendations, the socio-demographic status of women, and their responses might be different. Lastly, due to insufficient numbers of influenza and COVID-19 vaccine hesitant subjects, a multivariable analysis could not be performed for the factors associated with vaccine uptake or intention, although, the inclusion of open-ended questions gave us more insights on decision making around individual vaccines. Future studies are needed to study vaccination behaviors of women who are not seeking antenatal care and those seeing private obstetricians.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the importance of inclusion of maternal vaccines in government programs. Further, the study highlights the role of clinicians, community health workers, and families in vaccine uptake among pregnant women in West Bengal. Additionally, the study shows that women were generally vaccine acceptors and believed in the benefits and protection mediated by maternal vaccines and expressed their intention to receive and even pay for vaccines not included in the program. Low awareness and fear of side effects were barriers. The findings can influence the future strategies to improve the acceptance of maternal vaccines and advocacy efforts for vaccine policy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the study participants. Sincere appreciation is extended to Dr. Amita Pathak, Dr. Jagriti Pandey, the on-duty medical interns, nursing staff and hospital administration of the three study hospitals for facilitating this work. We also want to acknowledge the district West Midnapore and state health authorities for giving us the permission to do this study. Lastly, we want to thank Dr. Joanna D Das for reviewing the manuscript and providing critical inputs.

Biography

Tila Khan is a DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance Fellow at School of Medical Science & Technology, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, West Bengal, India. She has a PhD in Molecular Virology from Virginia Tech, USA and post PhD research experience in public health research in India. During PhD, she developed immunomodulatory influenza vaccines. Her research interests are molecular epidemiology, vaccine access in high-risk groups, vaccine acceptance, vaccine equity, vaccine policy and evidence-based research. She received the Robert Austrian Research Award in 2016 in the field of pneumococcal vaccinology in Scotland. She is recipient of the prestigious DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance Early Career Fellowship in Clinical and Public Health Research on building the evidence base for maternal influenza and RSV immunization to protect infants from lower respiratory tract infections. She is looking into estimating the burden of influenza, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, COVID-19 among infants and pregnant women in a rural district in West Bengal. Further, she is studying the impact of respiratory viral infections such as influenza, RSV and COVID-19 on pregnancy and perinatal outcomes.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology/Wellcome Trust India Alliance under Grant [IA/CPHE/19/1/504599, Dated 06/08/2019].

Abbreviation

- MI

Maternal Immunization

- Td

Tetanus diphtheria

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- HCP

Health care provider

- ANC

Antenatal care

- ASHA

Accredited Social Health Activist

- ANM

Auxiliary Nurse Midwives

- KSDH

Kharagpur Sub Divisional Hospital

- MMCH

Midnapore Medical College & Hospital

- SERH

South Eastern Railway Hospital

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Authors’ contribution

SDB and TK conceived the study design; TK prepared the questionnaire with inputs from SDB and RSD; RSD and MJ conducted interviews under the supervision of SR, PS, TG, SPC and KM; RSD, MJ and TK worked on qualitative data analysis; SH plotted the map; TK performed statistical analysis, interpretation and drafted the original manuscript; SDB revised it critically for intellectual content; and all authors approved the final version of the article and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data availability statement

Data supporting the findings of this study will be made available on reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2024.2383030

References

- 1.Roper MH, Vandelaer JH, Gasse FL.. Maternal and neonatal tetanus. Lancet Lond Engl. 2007;370(9603):1947–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61261-6. PMID: 17854885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuzil KM, Reed GW, Mitchel EF, Simonsen L, Griffin MR. Impact of influenza on acute cardiopulmonary hospitalizations in pregnant women. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(11):1094–1102. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009587. PMID: 9850132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhat N, Wright JG, Broder KR, Murray EL, Greenberg ME, Glover MJ, Likos AM, Posey DL, Klimov A, Lindstrom SE, et al. Influenza-associated deaths among children in the United States, 2003–2004. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(24):2559–2567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051721. PMID: 16354892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somerville LK, Basile K, Dwyer DE, Kok J. The impact of influenza virus infection in pregnancy. Future Microbiol. 2018;13:263–274. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2017-0096. PMID: 29320882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandeil W, van den Ende C, Bunge EM, Jenkins VA, Ceregido MA, Guignard A. A systematic review of the burden of pertussis disease in infants and the effectiveness of maternal immunization against pertussis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020;19(7):621–638. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2020.1791092. PMID: 32772755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, Thiruvengadam R, Rauch S, Kholin A, Roggero P, Prefumo F, Do Vale MS, Cardona-Perez JA, et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID multinational cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(8):817–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050. PMID: 33885740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Omer SB, Longo DL. Maternal immunization. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(13):1256–1267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1509044. PMID: 28355514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Tetanus. Fact Sheets [Internet]. 2023. Aug 24. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tetanus.

- 9.Cousins S. India is declared free of maternal and neonatal tetanus. BMJ. 2015;350:h2975. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2975. PMID: 26032894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Health Mission . Immunization. https://www.nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=824&lid=220.

- 11.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare . Tetanus and adult diphtheria (Td): operational guidelines. Introduction of Td vaccine in universal immunization program of India [internet]. https://jsiindia.in/assets/img/pdf/td-vaccine.pdf.

- 12.Dash R, Agrawal A, Nagvekar V, Lele J, Di Pasquale A, Kolhapure S, Parikh R. Towards adult vaccination in India: a narrative literature review. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16(4):991–1001. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1682842. PMID: 31746661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare . Universal Immunization Program. India: MoHFW; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraham K, Abraham A, Regi A, Lionel J, Thomas E, Vijayaselvi R, Jeyaseelan L, Abraham AM, Santhanam S, Kuruvilla KA, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes of influenza in pregnancy after treatment with Oseltamivir. J Glob Infect Dis. 2021;13(1):20–26. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_157_20. PMID: 33911448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhalerao-Gandhi A, Chhabra P, Arya S, Simmerman JM. Influenza and pregnancy: a review of the literature from India. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2015;2015:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2015/867587. PMID: 25810687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaman K, Roy E, Arifeen SE, Rahman M, Raqib R, Wilson E, Omer SB, Shahid NS, Breiman RF, Steinhoff MC. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1555–1564. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708630. PMID: 18799552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda S, Hisano M, Komano J, Yamamoto H, Sago H, Yamaguchi K. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and its usefulness to mothers and their young infants. J Infect Chemother Off J Jpn Soc Chemother. 2015;21(4):238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.01.015. PMID: 25708925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omer SB, Goodman D, Steinhoff MC, Rochat R, Klugman KP, Stoll BJ, Ramakrishnan U, Cooper BS. Maternal influenza immunization and reduced likelihood of prematurity and small for gestational age births: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2011;8(5):e1000441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000441. PMID: 21655318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahni LC, Olson SM, Halasa NB, Stewart LS, Michaels MG, Williams JV, Englund JA, Klein EJ, Staat MA, Schlaudecker EP, et al. Maternal vaccine effectiveness against influenza-associated hospitalizations and emergency department visits in infants. JAMA Pediatr [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2024 Jan 5.] doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.5639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO . Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper – November 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87(47):461–476. PMID: 23210147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA . Maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination by 2005: strategies for achieving and maintaining elimination [internet]. 2000. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/maternal_health_2000.pdf.

- 22.Ortiz JR, Englund JA, Neuzil KM. Influenza vaccine for pregnant women in resource-constrained countries: a review of the evidence to inform policy decisions. Vaccine. 2011;29(27):4439–4452. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.048. PMID: 21550377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forsyth KD, Tan T, von König C-H, Heininger U, Chitkara AJ, Plotkin S. Recommendations to control pertussis prioritized relative to economies: a global pertussis initiative update. Vaccine. 2018;36(48):7270–7275. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.028. PMID: 30337176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arriola CS, Suntarattiwong P, Dawood FS, Soto G, Das P, Hunt DR, Sinthuwattanawibool C, Kurhe K, Thompson MG, Wesley MG, et al. What do pregnant women think about influenza disease and vaccination practices in selected countries. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(7):2176–2184. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1851536. PMID: 33499708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Directorate General of Health Services . Seasonal influenza: guidelines for vaccination with influenza vaccine. [accessed 2017 Apr 25]. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/30580390001493710612.pdf.

- 26.Koul PA, Bali NK, Ali S, Ahmad SJ, Bhat MA, Mir H, Akram S, Khan UH. Poor influenza vaccination in pregnant females in north India. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;127(3):234–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhaskar E, Thobias S, Anthony S, Kumar V, Navaneethan N. Vaccination rates for pandemic influenza among pregnant women: an early observation from Chennai, South India. Lung India Off Organ Indian Chest Soc. 2012;29(3):232–235. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.99105. PMID: 22919161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dash N, Rose W. Antenatal TdaP: it’s time India adapts. Pediatr Inf Dis. 2020;2:120–121. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10081-1271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization South-East Asia . Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI). Factsheet 2023 India [Internet]. 2023. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/375309/India-EPI-factsheet-2023.pdf?sequence=1.

- 30.Singh V, S B, Lalwani S, Singh R, Singh P, Datta K, Mohanty N, Poddar S, Sodani R, Saha M, et al. Evaluation of pertussis disease in young infants in India: a hospital-based multicentric observational study. Indian J Pediatr. 2024;91(4):358–365. doi: 10.1007/s12098-023-04700-y. PMID: 37378885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apte A, Shrivastava R, Sanghavi S, Mitra M, Ramanan PV, Chhatwal J, Jain S, Chowdhury J, Premkumar S, Kumar R, et al. Multicentric hospital-based surveillance of pertussis amongst infants admitted in tertiary care facilities in India. Indian Pediatr. 2021;58(8):709–717. PMID: 34465657. 10.1007/s13312-021-2276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Viswanathan R, Bafna S, Patil K, Jadhav S, Katendra S, Mishra S, Maheshwari S, Damle H. Pertussis seroprevalence in mother–infant pairs from India: role of maternal immunisation. Arch Dis Child. 2022;107(5):431–435. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2021-322286. PMID: 34526295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.FOGSI . Vaccination in women. India: Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Committee Opinion No . 718: update on immunization and pregnancy: tetanus, diptheria, and pertussis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(3):153–157. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abu-Raya B, Forsyth K, Halperin SA, Maertens K, Jones CE, Heininger U, Hozbor D, Wirsing von König CH, Chitkara AJ, Muloiwa R, et al. Vaccination in pregnancy against pertussis: a consensus statement on behalf of the global pertussis initiative. Vaccines. 2022;10(12):1990. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10121990. PMID: 36560400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaur H, Sehgal A, Malik N, Kaushal S, Kaundal A. Knowledge and practice of gynecologists about tdap and influenza vaccination: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2023;15:e40037. doi: 10.7759/cureus.40037. PMID: 37425540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrews MA, Areekal B, Rajesh KR, Krishnan J, Suryakala R, Krishnan B, Muraly CP, Santhosh PV. First confirmed case of COVID-19 infection in India: a case report. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151(5):490–492. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2131_20. PMID: 32611918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jha P, Deshmukh Y, Tumbe C, Suraweera W, Bhowmick A, Sharma S, Novosad P, Fu SH, Newcombe L, Gelband H, et al. COVID mortality in India: national survey data and health facility deaths. Science. 2022;375(6581):667–671. doi: 10.1126/science.abm5154. PMID: 34990216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu S, Anzai A, Nishiura H. Reconstructing the COVID-19 incidence in India using airport screening data in Japan. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12879-023-08882-w. PMID: 38166666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calvert C, John J, Nzvere FP, Cresswell JA, Fawcus S, Fottrell E, Say L, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality in the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a rapid systematic review. Global Health Action. 2021;14(sup1):1974677. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1974677. PMID: 35377289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumari V, Mehta K, Choudhary R. COVID-19 outbreak and decreased hospitalisation of pregnant women in labour. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9):1116–1117. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30319-3. PMID: 32679037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wikipedia . COVID-19 vaccination in India. 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_vaccination_in_India.

- 43.DeSisto CL, Wallace B, Simeone RM, Polen K, Ko JY, Meaney-Delman D, Ellington SR. Risk for stillbirth among women with and without COVID-19 at delivery hospitalization — United States, March 2020–September 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(47):1640–1645. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7047e1. PMID: 34818318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization . Update on WHO interim recommendations on COVID-19 vaccination of pregnant and lactating women. [accessed 2021 June 2]. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/2021-dha-docs/update-on-who-interim-recommendations-on-c-19-vaccination-for-pregnant-and-lactating-women-70-.pdf?sfvrsn=2c1d9ac8_1&download=true.

- 45.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare . Pregnant women now eligible for COVID-19 vaccination. 2021. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1732312.

- 46.Agarwal SK, Naha M. COVID-19 vaccine coverage in India: a district-level analysis. Vaccines. 2023;11(5):948. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11050948. PMID: 37243052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Premkumar M, Kumar Chawla Y. Chronic hepatitis B: challenges and successes in India. Clin Liver Dis. 2021;18(3):111–116. doi: 10.1002/cld.1125. PMID: 34691396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization . Operational guidelines for hepatitis B vaccine introduction in the universal immunization programme. New Delhi: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murhekar MV, Santhosh Kumar M, Kamaraj P, Khan SA, Allam RR, Barde P, Dwibedi B, Kanungo S, Mohan U, Mohanty SS, et al. Hepatitis-B virus infection in India: findings from a nationally representative serosurvey, 2017-18. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis. 2020;100:455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.084. PMID: 32896662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.World Health Organization . Preventing perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission: a guide for introducing and strengthening hepatitis B birth dose vaccination [internet]. 2015. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/208278/9789241509831_eng.pdf.

- 51.Maltezou HC, Effraimidou E, Cassimos DC, Medic S, Topalidou M, Konstantinidis T, Theodoridou M, Rodolakis A. Vaccination programs for pregnant women in Europe, 2021. Vaccine. 2021;39(41):6137–6143. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.08.074. PMID: 34462162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ault KA, Riley LE, ACOG Committee. Maternal immunization. Practice Advisory. 2022. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2022/10/maternal-immunization. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Larson HJ, Gakidou E, Murray CJL, Longo DL. The vaccine-hesitant moment. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(1):58–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2106441. PMID: 35767527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.WHO . Ten threats to global health in 2019. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dhamania M, Gaur K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on routine immunization services in a tertiary care hospital of Rajasthan, India. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2023;12(4):313–318. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2023.12.4.313. PMID: 38025919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ennab F, Qasba RK, Uday U, Priya P, Qamar K, Nawaz FA, Islam Z, Zary N. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a narrative review of four South Asian countries. Front Public Health. 2022;10:997884. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.997884. PMID: 36324470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, Chaudhuri M, Zhou Y, Dube E, Schuster M, MacDonald NE, Wilson R, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy . Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4165–4175. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037. PMID: 25896384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coe AB, Gatewood SBS, Moczygemba LR, Goode J-V, Beckner JO. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the novel (2009) H1N1 influenza vaccine. Innov Pharm. 2012;3(2):1–11. doi: 10.24926/iip.v3i2.257. PMID: 22844651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chimukuche RS, Ngwenya N, Seeley J, Nxumalo PS, Nxumalo ZP, Godongwana M, Radebe N, Myburgh N, Adedini SA, Cutland C. Assessing community acceptance of maternal immunisation in Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a qualitative investigation. Vaccines. 2022;10(3):415. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10030415. PMID: 35335047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blagden S, Seddon D, Hungerford D, Stanistreet D, Brusic V. Uptake of a new meningitis vaccination programme amongst first-year undergraduate students in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0181817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181817. PMID: 28767667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saleem SA, Jan SS. Modified kuppuswamy socioeconomic scale updated for the year 2021. Indian J Forensic Community Med. 2021;8(1):1–3. doi: 10.18231/j.ijfcm.2021.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief Model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175–183. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. PMID: 3378902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson R. Religion, socio-economic backwardness & discrimination: the case of Indian muslims. Indian J Ind Relat. 2008;44:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mansoor K. Status of employment and occupations of muslims in India: evidence from a household survey – 2011–2012. J Muslim Minor Aff. 2021;41(4):742–762. doi: 10.1080/13602004.2022.2032900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumari A, Kumari S, Kujur M, Tirkey S, Singh SB. Acceptance rate of COVID-19 vaccine and its determinants among Indian pregnant women: a hospital-based cross-sectional analysis. Cureus. 2022;14:e30682. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30682. PMID: 36439607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kochhar S, Edwards KM, Ropero Alvarez AM, Moro PL, Ortiz JR. Introduction of new vaccines for immunization in pregnancy – programmatic, regulatory, safety and ethical considerations. Vaccine. 2019;37(25):3267–3277. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare . National family health survey (NFHS-5) 2019-21: India and West Bengal. https://ruralindiaonline.org/hi/library/resource/national-family-health-survey-nfhs-5-2019-21-west-bengal/.

- 68.Johm P, Nkoum N, Ceesay A, Mbaye EH, Larson H, Kampmann B. Factors influencing acceptance of vaccination during pregnancy in the Gambia and Senegal. Vaccine. 2021;39(29):3926–3934. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.068. PMID: 34088509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hasnain S, Sheikh NH. Causes of low tetanus toxoid vaccination coverage in pregnant women in Lahore district, Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J Rev Sante Mediterr Orient Al-Majallah Al-Sihhiyah Li-Sharq Al-Mutawassit. 2007;13(5):1142–1152. doi: 10.26719/2007.13.5.1142. PMID: 18290408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Galanis P, Vraka I, Siskou O, Konstantakopoulou O, Katsiroumpa A, Kaitelidou D. Uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines. 2022;10(5):766. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050766. PMID: 35632521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gandhi AP, Thakur JS, Gupta M, Kathirvel S, Goel K, Singh T. COVID-19 vaccination uptake and adverse events following COVID-19 immunization in pregnant women in Northern India: a prospective, comparative, cohort study. J Rural Med JRM. 2022;17(4):228–235. doi: 10.2185/jrm.2022-025. PMID: 36397796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goruntla N, Karisetty B, Nandini N, Bhupasamudram B, Gangireddy HR, Veerabhadrappa KV, Ezeonwumelu JOC, Bandaru V. Adverse events following COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant women attending primary health centers: an active-surveillance study. Vacunas. 2023;24(4):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.vacun.2023.05.003. PMID: 37362835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Skjefte M, Ngirbabul M, Akeju O, Escudero D, Hernandez-Diaz S, Wyszynski DF, Wu JW. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and mothers of young children: results of a survey in 16 countries. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(2):197–211. doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00728-6. PMID: 33649879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goncu Ayhan S, Oluklu D, Atalay A, Menekse Beser D, Tanacan A, Moraloglu Tekin O, Sahin D. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in pregnant women. Intl J Gynecol Obste. 2021;154(2):291–296. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13713. PMID: 33872386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sutton D, D’Alton M, Zhang Y, Kahe K, Cepin A, Goffman D, Staniczenko A, Yates H, Burgansky A, Coletta J, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant, breastfeeding, and nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3(5):100403. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100403. PMID: 34048965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nguyen LH, Hoang MT, Nguyen LD, Ninh LT, Nguyen HTT, Nguyen AD, Vu LG, Vu GT, Doan LP, Latkin CA, et al. Acceptance and willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women in Vietnam. Trop Med Int Health TM IH. 2021;26(10):1303–1313. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13666. PMID: 34370375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Habbash AS, Siddiqui AF. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women: a cross sectional study from Abha City, Saudi Arabia. Vaccines. 2023;11(9):1463. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11091463. PMID: 37766139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Calhoun K, Kahn KE, Razzaghi H, Garacci E, Lindley M, Black C. Association of vaccine hesitancy with maternal influenza and Tdap vaccination coverage – United States, 2019–20 to 2022–23. CDC; 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/pregnant-women-sept2023.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Woodcock T, Novov V, Skirrow H, Butler J, Lovett D, Adeleke Y, Blair M, Saxena S, Majeed A, Aylin P. Characteristics associated with influenza vaccination uptake in pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2023;73:148–155. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2022.0078. PMID: 36702602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Adeyanju GC, Engel E, Koch L, Ranzinger T, Shahid IBM, Head MG, Eitze S, Betsch C. Determinants of influenza vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women in Europe: a systematic review. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00584-w. PMID: 34583779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ahluwalia IB, Jamieson DJ, Rasmussen SA, D’Angelo D, Goodman D, Kim H. Correlates of seasonal influenza vaccine coverage among pregnant women in Georgia and Rhode Island. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):949–955. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f1039f. PMID: 20859160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Varan AK, Esteves-Jaramillo A, Richardson V, Esparza-Aguilar M, Cervantes-Powell P, Omer SB. Intention to accept bordetella pertussis booster vaccine during pregnancy in Mexico City. Vaccine. 2014;32(7):785–792. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.054. PMID: 24394441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Praphasiri P, Ditsungneon D, Greenbaum A, Dawood FS, Yoocharoen P, Stone DM, Olsen SJ, Lindblade KA, Muangchana C, Chuang J-H. Do Thai physicians recommend seasonal influenza vaccines to pregnant women? A Cross-sectional survey of physicians’ perspectives and practices in Thailand. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169221. PMID: 28099486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li R, Xie R, Yang C, Rainey J, Song Y, Greene C. Identifying ways to increase seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women in China: a qualitative investigation of pregnant women and their obstetricians. Vaccine. 2018;36(23):3315–3322. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.060. PMID: 29706294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koul PA, Mir H. The biggest barrier to influenza vaccination in pregnant females in India: poor sensitization of the care providers. Vaccine. 2018;36(25):3569–3570. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.039. PMID: 29801758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Giduthuri JG, Purohit V, Maire N, Kudale A, Utzinger J, Schindler C, Weiss MG. Influenza vaccination of pregnant women: engaging clinicians to reduce missed opportunities for vaccination. Vaccine. 2019;37(14):1910–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.02.035. PMID: 30827735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bali NK, Ashraf M, Ahmad F, Khan UH, Widdowson M-A, Lal RB, Koul PA. Knowledge, attitude, and practices about the seasonal influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in Srinagar, India. Influenza Resp Viruses. 2013;7(4):540–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00416.x. PMID: 22862774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Giduthuri JG, Purohit V, Kudale A, Utzinger J, Schindler C, Weiss MG. Antenatal influenza vaccination in urban Pune, India: clinician and community stakeholders’ awareness, priorities, and practices. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(4):1211–1222. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1806670. PMID: 32966146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Khan AA, Varan AK, Esteves-Jaramillo A, Siddiqui M, Sultana S, Ali AS, Zaidi AKM, Omer SB. Influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in urban slum areas, Karachi, Pakistan. Vaccine. 2015;33(39):5103–5109. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.014. PMID: 26296492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Limaye RJ, Singh P, Paul A, Fesshaye B, Lee C, Zavala E, Wade S, Ali H, Rahman H, Akter S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine decision-making among pregnant and lactating women in Bangladesh. Vaccine. 2023;41(26):3885–3890. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.05.024. PMID: 37208208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Salloum M, Paviotti A, Bastiaens H, Van Geertruyden J-P. The inclusion of pregnant women in vaccine clinical trials: an overview of late-stage clinical trials’ records between 2018 and 2023. Vaccine. 2023;41(48):7076–7083. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.10.057. PMID: 37903681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Giri S, Sahoo S, Angadi S, Afzalpurkar S, Sundaram S, Bhrugumalla S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus among pregnant women in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;12(6):1408–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2022.08.005. PMID: 36340309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study will be made available on reasonable request.