Abstract

This study demonstrates that root-associated Kosakonia oryziphila NP19, isolated from rice roots, is a promising plant growth-promoting bioagent and biopesticide for combating rice blast caused by Pyricularia oryzae. In vitro experiments were conducted on fresh leaves of Khao Dawk Mali 105 (KDML105) jasmine rice seedlings. The results showed that NP19 effectively inhibited the germination of P. oryzae fungal conidia. Fungal infection was suppressed across three different treatment conditions: rice colonized with NP19 and inoculated by fungal conidia, a mix of NP19 and fungal conidia concurrently inoculated on the leaves, and fungal conidia inoculation first followed by NP19 inoculation after 30 h. Additionally, NP19 reduced fungal mycelial growth by 9.9–53.4%. In pot experiments, NP19 enhanced the activities of peroxidase (POD) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) by 6.1–63.0% and 3.0–67.7%, respectively, indicating a boost in the plant’s defense mechanisms. Compared to the uncolonized control, the NP19-colonized rice had 0.3–24.7% more pigment contents, 4.1% more filled grains per panicle, 26.3% greater filled grain yield, 34.4% higher harvest index, and 10.1% more content of the aroma compound 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (2AP); for rice colonized with NP19 and infected with P. oryzae, these increases were 0.2–49.2%, 4.6%, 9.1%, 54.4%, and 7.5%, respectively. In field experiments, blast-infected rice that was colonized and/or inoculated with NP19 treatments had 15.1–27.2% more filled grains per panicle, 103.6–119.8% greater filled grain yield, and 18.0–35.8% higher 2AP content. A higher SOD activity (6.9–29.5%) was also observed in the above-mentioned rice than in the blast-infected rice that was not colonized and inoculated with NP19. Following blast infection, NP19 applied to leaves decreased blast lesion progression. Therefore, K. oryziphila NP19 was demonstrated to be a potential candidate for use as a plant growth-promoting bioagent and biopesticide for suppressing rice blast.

Keywords: Biocontrol agent, KDML105 jasmine rice, Kosakonia oryziphila, Plant growth-promoting bacteria, Rice blast fungi

Subject terms: Applied microbiology, Plant stress responses

Introduction

Thai jasmine rice (Oryza sativa L. cv. Khao Dawk Mali 105: KDML105) is a valuable and well-known crop in Thailand and is well-known worldwide for its unique aroma and exceptional quality. 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline (2AP) has been identified as the main aroma compound of KDML105, which is a factor in its pricing1. As a result of its environment, rice encounters several abiotic and biotic stresses. Infection by rice blast caused by Pyricularia oryzae (teleomorph: Magnaporthe oryzae) reduces rice yield by 10–30% and even up to 40–50% under severe conditions2. Several management strategies are used to control rice blast pertaining to different rice cultivars, including cultural strategies like crop rotation, irrigation, and fertilizer management. A major strategy for achieving successful rice production has long been to plant varieties that are resistant to rice blast. However, the resistance of newly deployed cultivars is less effective as a result of rapid genetic mutations in P. oryzae3. Chemical fungicides are widely used because of their effectiveness. However, there are several factors that influence the effectiveness of fungicides. These factors include the composition of the compound, the timing and method of application, the severity of the disease, the efficiency of disease forecasting systems, and the rate of emergence of fungicide-resistant strains4. In addition, chemical fungicide application may cause residual toxicity in the environment and may be unhealthy for users5.

Biological control is becoming increasingly important for managing rice blast and other plant diseases6,7 because these approaches are inexpensive and harmless, and even if they are slow, they can last a long time and provide long-term benefits8. In addition, the use of natural fungicidal compounds from plants such as Tribulus terrestris has been demonstrated to be beneficial in the control of P. oryzae9 and Trichoderma harzianum and T. viride can control Sclerotium rolfsii10. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) are safe and effective alternatives to chemical pesticides. Biological control by PGPR provides a cost-effective and long-term solution for managing plant diseases and reducing crop loss11,12. The beneficial effects of PGPR on host plants are mediated by direct and indirect mechanisms. The direct mechanisms include (i) biofertilizer properties such as phosphate solubilization, biological nitrogen fixation, and solubilization of insoluble potassium and (ii) the production of phytohormones, indole acetic acid, gibberellin, and ethylene. Indirect mechanisms include (i) stress tolerance via the biosynthesis of proline and quaternary amines, the production of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxidase (POX), and (ii) biological control properties such as the production of lytic enzymes (chitinase, cellulase and others), the production of antibiotic and antifungal metabolites, and acquired and induced systemic resistance11,13.

The root-associated bacterium Kosakonia oryziphila NP19 was isolated from rice (Oryza sativa L. cv. RD6 roots)14. The plant growth-promoting properties of K. oryziphila NP19 include nitrogen fixation, indole acetic acid (IAA) production, and phosphate solubilization. Interestingly, a strain of K. oryziphila NP19 was found to produce chitinase enzymes14. The application of K. oryziphila NP19 to KDML105 rice seeds improved rice survival after infection with rice blast fungus. The present investigation aimed to (i) elucidate the suppression of rice blast fungus by K. oryziphila NP19 and (ii) study the effect of K. oryziphila NP19 applied for rice blast control.

Results

Effects of K. oryziphila NP19 cell suspension on P. oryzae infection in rice

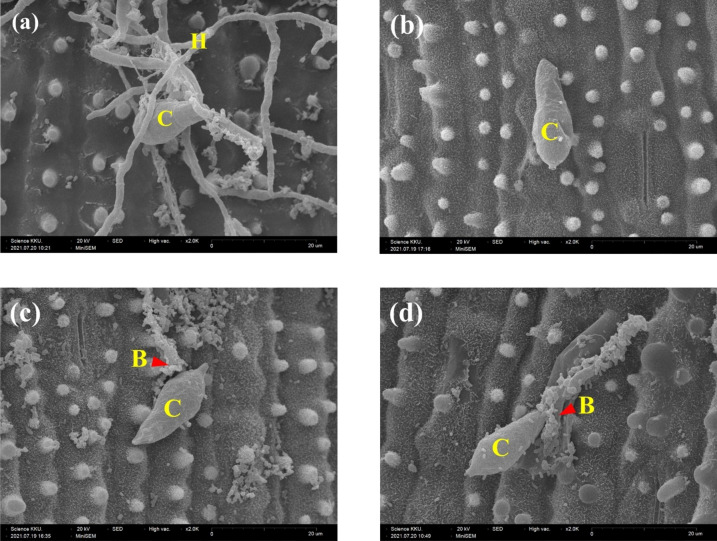

Khao Dawk Mali 105 leaf segments with fungal conidia were observed after 72 h of incubation. Similarly, the plants in the C, RB + F, R + BF, and RF + B treatments had healthy leaf characteristics, whereas those in the R + F treatment turned pale yellow (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online). To confirm fungal infection, rice leaf segments were observed under scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Hyphae were found in R + F, while only undeveloped conidia were found in RB + F. Both R + BF and RF + B resulted in undeveloped conidia attached to the expected K. oryziphila NP19 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

SEM photographs of P. oryzae on fresh KDML105 leaves after the treatments were established followed by incubation at 25 °C for 72 h. (a) 2 µL conidial suspension on an R leaf, (b) 2 µL conidial suspension on an RB leaf, (c) mixture of 2 µL conidial suspension and 2 µL K. oryziphila NP19 on an R leaf, (d) 2 µL conidial suspension for 30 h followed by 2 µL K. oryziphila NP19 on an R leaf. C, conidia; H, hypha; B, K. oryziphila NP19.

Suppression of P. oryzae mycelial growth by K. oryziphila NP19 cell suspension

The effects of K. oryziphila NP19 on mycelial growth were related to the bacterial cell concentration. Under untreated conditions (0% bacterial cells), the mycelial dry weight was 3.88 mg/mL. A bacterial concentration of 5.0 × 107–2.0 × 109 colony forming units (CFU)/mL inhibited mycelial growth by 9.9–53.4% (see Supplementary Table S1 online).

Pot experiment

Effects of K. oryziphila NP19 on rice growth, yield, and grain quality under rice blast fungal infection in a pot experiment

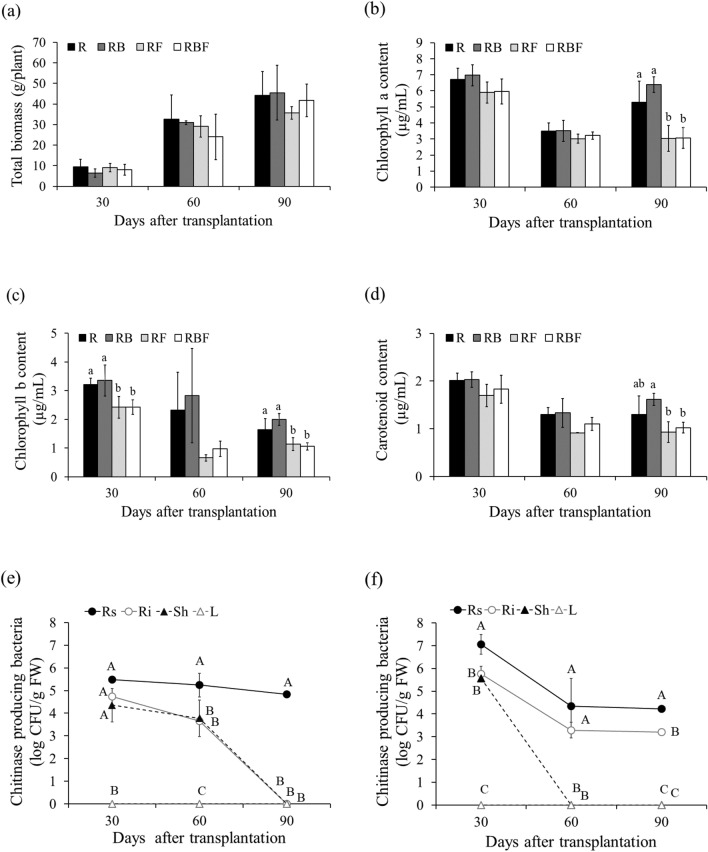

The total biomass did not differ significantly among the 4 treatments. At 30 and 60 days after transplanting (DAT), the total biomass of RB decreased by 32.2% and 5.2%, respectively, compared to that of R. Moreover, the total biomass of RBF decreased slightly by 10.5% and 17.4% at 30 and 60 DAT, respectively, compared to that of RF. However, at 90 DAT, the total biomass of RB and RBF increased slightly, by 2.8% (compared to R) and 17.1% (compared to RF), respectively (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Agronomic traits of KDML105 rice plants grown under greenhouse conditions with and without rice blast infection. (a) Total biomass, (b) chlorophyll a, (c) chlorophyll b, and (d) carotenoids. The numbers of chitinase-producing bacteria isolated from different plant tissues of KDML105 rice (e) RB and (f) RBF. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments at the same time based on the LSD test. Uppercase letters indicate significant differences between the bacterial numbers in different plant tissues at the same time and in the same treatments based on the LSD test.

The pigment content in RB exceeded that in R by more than 0.3%. The chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoid contents increased in RB by 4.0%, 4.6%, and 0.9% (at 30 DAT), 0.3%, 21.5%, and 2.7% (at 60 DAT), and 20.6%, 21.5%, and 24.7% (at 90 DAT), respectively. Under fungal infection, the chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoid contents in RF were lower than those in R by 12.0–42.7%, 24.5–71.7%, and 15.8–29.5%, respectively, at 30–90 DAT. However, compared with those in RF, the chlorophyll a and carotenoid contents in response to K. oryziphila NP19 colonization increased, by 0.9–6.7% and 7.8–20.2%, respectively, at 30–90 DAT, while the chlorophyll b content increased, by 0.2–49.2%, at 30–60 DAT (Fig. 2b–d).

The yield components did not differ significantly between treatments except for the number of filled grains per panicle. However, compared with those in R, the panicle length, 1,000-grain weight, number of filled grains per panicle, yield, and harvest index in RB increased by 12.4%, 3.9%, 4.1%, 26.3%, and 34.4%, respectively. Under fungal infection (RF), the panicle number, panicle length, number of filled grains per panicle, yield, and harvest index decreased, by 12.0%, 1.8%, 6.1%, 8.5%, and 22.2%, respectively, compared to those under R. Moreover, compared with those under RF, the panicle length, number of filled grains per panicle, yield, and harvest index under RBF increased, by 1.4%, 4.6%, 9.1%, and 54.4%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Grain yield and properties of KDML105 rice plants grown under greenhouse conditions with and without rice blast infection.

| Treatment | Panicle no. per plant | Panicle length (cm) | 1000-grain weight (g) | Filled grain/panicle (%) | Yield (filled grain weight (g/plant)) | Harvest index | Total starch (mg/g rice) | Amylose content (%) | Protein (mg/g rice) | 2AP content (ng/g rice) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 8.3 ± 1.2 | 20.83 ± 2.15 | 25.21 ± 0.16 | 88.76 ± 2.96ab | 12.29 ± 2.40 | 0.53 ± 0.16 | 453.1 ± 18.4 | 13.2 ± 1.0 | 6.02 ± 0.75 | 329.9 ± 27.9 |

| RB | 7.0 ± 1.0 | 23.40 ± 1.03 | 26.19 ± 0.79 | 92.41 ± 2.34a | 15.53 ± 3.33 | 0.72 ± 0.14 | 482.6 ± 10.2 | 14.0 ± 0.8 | 5.96 ± 0.21 | 363.2 ± 151.1 |

| RF | 7.3 ± 2.5 | 20.46 ± 0.17 | 27.27 ± 2.86 | 83.32 ± 2.81c | 11.24 ± 3.08 | 0.41 ± 0.09 | 476.7 ± 31.9 | 15.1 ± 1.1 | 6.42 ± 0.84 | 329.7 ± 229.1 |

| RBF | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 20.74 ± 2.48 | 25.41 ± 0.98 | 87.14 ± 2.14bc | 12.26 ± 2.47 | 0.64 ± 0.32 | 450.2 ± 0.0 | 14.1 ± 9.9 | 6.12 ± 0.67 | 354.3 ± 164.0 |

| p < 0.05 | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

ns and * indicate a nonsignificant difference and a significant difference at p < 0.05, respectively. Means followed by different letters within a column are significantly different at p < 0.05, as determined by the LSD test.

The grain quality did not differ significantly among the treatments. The total starch, amylose, protein, and 2AP contents were 450.2–482.6 mg/g rice grain, 13.2–15.1%, 5.96–6.42 mg/g rice grain, and 329.7–363.2 ng/g rice grain, respectively. Interestingly, the 2AP contents in RB and RBF increased slightly, by 10.1% (compared to those in R) and 7.5% (compared to those in RF), respectively (Table 1).

Distribution of K. oryziphila NP19 in KDML105 rice in the pot experiment

Total bacteria, which were able to grow on chitin agar, were extracted from the rice plants. At 30, 60, and 90 DAT, the bacterial concentrations on the root surface (Rs) were 5.5, 5.2, and 4.8 log CFU/g plant in RB, respectively. In the root interior (Ri) and shoot (Sh), the bacterial concentrations were 4.7 and 4.4 log CFU/g plant (30 DAT) and 3.7 and 3.8 log CFU/g plant (60 DAT), respectively (Fig. 2e). In RBF, bacteria were found in Rs and Ri at 30–90 DAT. The bacterial concentrations in Rs were 7.1, 4.3, and 4.2 log CFU/g plant at 30, 60, and 90 DAT, respectively. In Ri, the bacteria decreased slightly, i.e., 5.8, 3.3, and 3.2 log CFU/g plant. In Sh, the bacterial concentration was 5.6 log CFU/g plant only at 30 DAT (Fig. 2f). Moreover, bacteria were not found in the leaves (L) of the plants in the RB and RBF treatments. The random colonies were identified by 16S rDNA sequencing, and the results were similar to those for K. oryziphila.

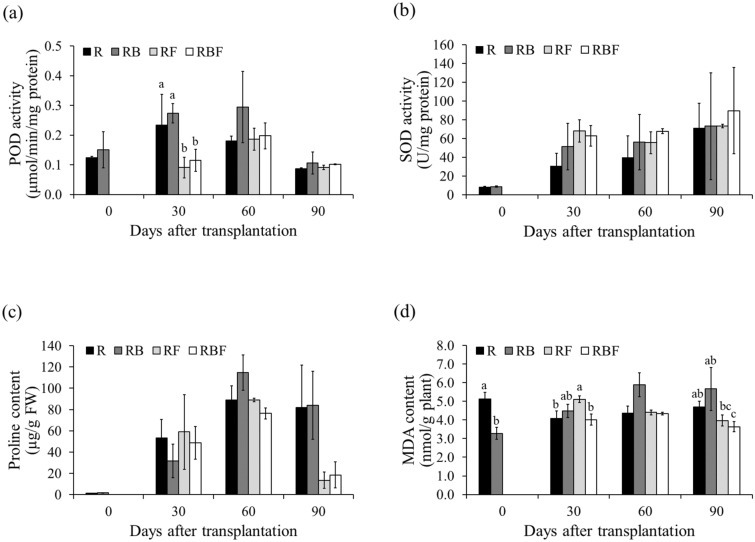

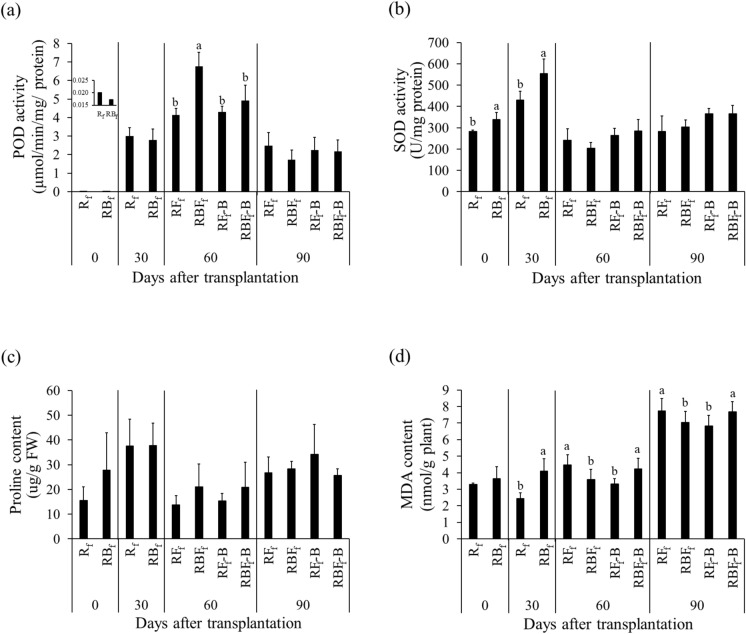

Effects of K. oryziphila NP19 on the antioxidant response of KDML105 rice in a pot experiment

Peroxidase activity differed significantly between treatments at 30 DAT, and the fungal infection treatments resulted in lower POD activity. However, colonization with K. oryziphila NP19 enhanced POD activity. In RB, POD activity increased by 22.2%, 17.1%, 63.0%, and 22.3% at 0, 30, 60, and 90 DAT, respectively, compared to that in R. In RBF, POD activity increased by 27.1%, 6.1%, and 11.6% at 30, 60, and 90 DAT, respectively, compared to that in RF (Fig. 3a). Superoxide dismutase activity increased in RB by 4.1%, 67.7%, 40.6%, and 3.0% at 0, 30, 60, and 90 DAT, respectively) compared to that in R. In RBF, SOD activity increased (by 22.3%) at 60 and 90 DAT compared to that in RF. Interestingly, the SOD activity in RF increased by 121.9%, 39.4%, and 3.1% at 30, 60, and 90 DAT, respectively, compared to that in R (Fig. 3b). In this study, SOD may have been an important antioxidant defense against oxidative stress in plants.

Figure 3.

Antioxidant and lipid peroxidation in the leaves of KDML105 rice plants grown under greenhouse conditions with and without rice blast infection. (a) Peroxidase activity, (b) superoxide dismutase activity, (c) proline content, (d) malondialdehyde content. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments at the same time based on the LSD test.

At 30 DAT, the proline content in leaves in the RB and RBF treatments decreased by 40.5% (compared to that in the R treatment) and 17.4% (compared to that in the RF treatment), respectively. On the other hand, at 90 DAT, RB and RBF showed slight increases of 2.4% (compared to R) and 36.9% (compared to RF), respectively (Fig. 3c). However, the proline content did not differ significantly between treatments.

The malondialdehyde (MDA) content provides an indication of lipid peroxidation. In RB, the MDA content increased by 9.9%, 34.9%, and 20.3% at 30, 60, and 90 DAT, respectively, compared to that in R. On the other hand, in RBF, the MDA content decreased by 21.5%, 1.4%, and 8.4% at 30, 60, and 90 DAT, respectively, compared to that in RF. Compared with that in R, the MDA content in RF increased by 25.7% and 0.8% at 30 and 60 DAT, respectively, but decreased significantly by 15.6% at 90 DAT (Fig. 3d).

Rice blast severity in KDML105 rice in the pot experiment

Rice blast disease in RF and RBF presented specific lesions and was rated 5 (narrow or slightly elliptical lesions, 1–2 mm in breadth, more than 3 mm long with a brown margin), which indicated susceptible lesions. Nevertheless, lesions appeared on less than 1% of the leaves, and there was no difference between RF and RBF at 30–90 DAT. However, fungal conidia in the leaf lesion were observed under a light microscope to confirm the presence of P. oryzae (see Supplementary Fig. S2 online).

Field experiments

Effects of K. oryziphila NP19 on rice growth, yield, and grain quality under rice blast fungal infection in a field experiment

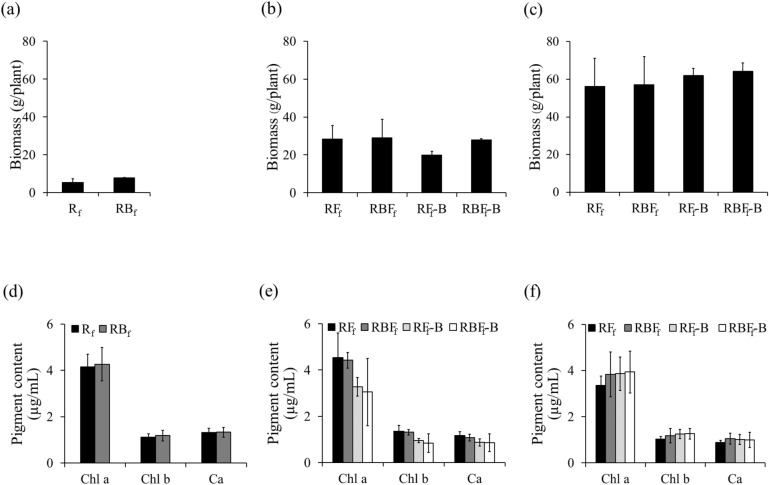

As there was no evidence of rice blast infection at 57 DAT, the experiment during 0–57 DAT was conducted with only two treatments (Rf and RBf). Nevertheless, after finding rice blast lesions at 58 DAT, all rice plants of the Rf and RBf treatments were changed to RFf and RBFf, respectively. At 58, 61, and 65 DAT, K. oryziphila NP19 culture was sprayed on the leaves of half of the total number of rice plants in both RFf and RBFf plots. Therefore, the experiments conducted at 60 and 90 DAT were divided into four treatments in which all infected with rice blast, including original treatments (RFf, RBFf) and new treatments (RFf-B, RBFf-B), where (-B) refers to spraying NP19 culture on rice leaves of RFf and RBFf, respectively.

The total biomass in RBf was greater than that in Rf by 42.5% at 30 DAT. At 60 and 90 DAT, the total biomass in RBFf was slightly greater than that in RFf by 2.6% and 1.7%, respectively. In addition, the total biomass of RBFf-B was greater than that of RFf-B by 39.5% and 3.6% at 60 and 90 DAT, respectively. However, the results were not significantly different between treatments (Fig. 4a–c).

Figure 4.

Agronomic traits of KDML105 rice plants grown under field conditions with and without rice blast disease infection. (a) Total biomass at 30 DAT, (b) total biomass at 60 DAT, (c) total biomass at 90 DAT, (d) pigment contents at 30 DAT, (e) pigment contents at 60 DAT, and (f) pigment contents at 90 DAT. Chl a chlorophyll a, Chl b chlorophyll b, Ca carotenoid.

Compared with those in Rf, the chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoid contents in RBf increased slightly, by 2.5%, 6.5%, and 1.1%, respectively, at 30 DAT. On the other hand, the chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoid contents in RBFf decreased slightly by 2.4%, 3.4%, and 7.3%, respectively, compared to those in RFf at 60 DAT. The pigment contents in RBFf-B decreased slightly, by 0.6–7.2%, compared to that in RFf-B. After applications of K. oryziphila NP19, at 90 DAT, the chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoid contents in RFf-B increased, by 15.2%, 22.2%, and 15.5%, respectively, compared to those in RFf (Fig. 4d–f). However, the results did not differ significantly between treatments.

The yield and yield components are shown in Table 2. Compared with RFf, the RBFf treatment significantly increased the number of filled grains per panicle and the grain yield by 27.2% and 115.3%, respectively. Interestingly, compared with RFf, RFf-B significantly increased the number of filled grains per panicle and the grain yield by 15.1% and 119.8%, respectively.

Table 2.

Grain yield and properties of KDML105 rice plants grown under field conditions and infected with rice blast disease.

| Treatment | Panicle no. per plant | Panicle length (cm) | 1000-grain weight (g) | Filled grain/panicle (%) | Yield (filled grain weight (g/m2)) | Total starch (mg/g rice) | Amylose content (%) | Protein (mg/g rice) | 2AP content (ng/g rice) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFf | 4.18 ± 2.23 | 27.99 ± 0.78 | 28.67 ± 2.80 | 66.76 ± 8.88b | 202.09 ± 131.68b | 425.29 ± 21.69 | 11.31 ± 0.54 | 3.03 ± 0.20 | 187.02 ± 25.57b |

| RBFf | 5.87 ± 0.12 | 27.80 ± 1.01 | 27.97 ± 0.75 | 84.94 ± 7.69a | 435.05 ± 56.39a | 563.22 ± 106.40 | 15.18 ± 2.10 | 2.79 ± 0.43 | 220.70 ± 20.02ab |

| RFf-B | 6.93 ± 0.95 | 27.04 ± 0.74 | 27.23 ± 1.39 | 76.82 ± 5.74ab | 444.22 ± 9.38a | 433.91 ± 24.88 | 12.23 ± 0.91 | 2.79 ± 0.19 | 230.51 ± 22.41ab |

| RBFf-B | 5.93 ± 1.47 | 27.67 ± 0.18 | 28.59 ± 1.70 | 83.91 ± 0.69a | 411.47 ± 131.94a | 419.54 ± 73.32 | 12.63 ± 2.05 | 2.92 ± 0.20 | 253.98 ± 24.13a |

| p < 0.05 | ns | ns | ns | * | * | ns | ns | ns | * |

ns and * indicate a nonsignificant difference and a significant difference at p < 0.05, respectively. Means followed by different letters within a column are significantly different at p < 0.05, as determined by the LSD test.

The grain quality did not significantly differ among the 4 treatments in terms of total starch content, amylose content, or total protein content. The total starch, amylose, and total protein contents were 419.54–563.22 mg/g rice grain, 11.3–15.2%, and 2.79–3.03 mg/g rice grain, respectively. Surprisingly, the 2AP content in RBFf-B differed significantly from that in RFf (35.8% increase in RBFf-B). In addition, the 2AP content in RBFf and RFf-B increased by 18.0% and 23.3%, respectively, compared to that in RFf (Table 2).

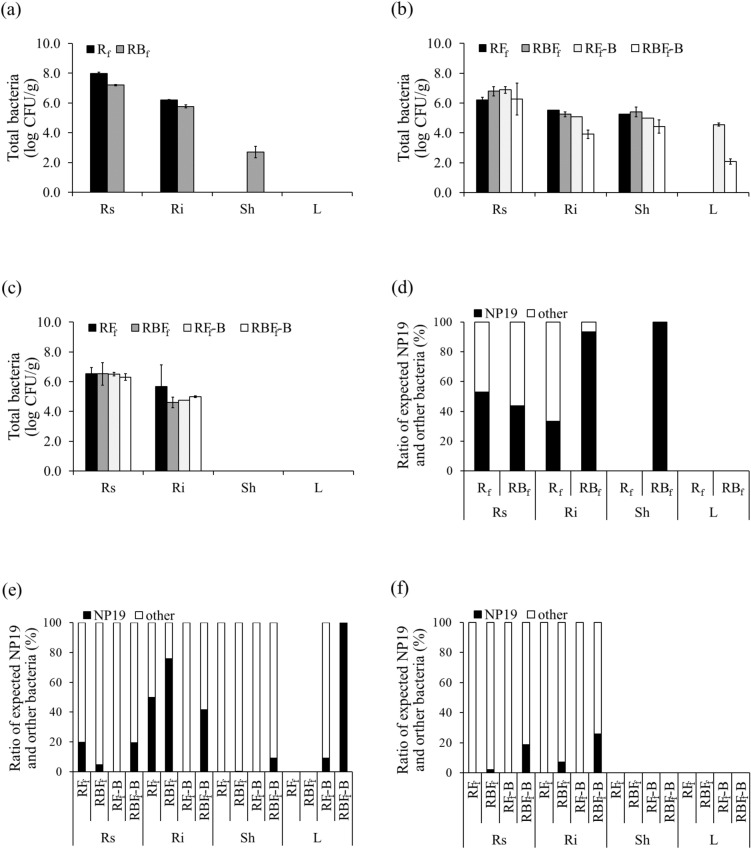

Distribution of K. oryziphila NP19 in KDML105 rice in the field experiment

At 30 DAT, the total bacterial concentrations in the Rs and Ri of Rf were 8.0 and 6.2 log CFU/g plant, respectively. In the RBf treatment, the total bacterial concentrations in Rs, Ri, and Sh were 7.2, 5.8, and 2.7 log CFU/g plant, respectively. Bacteria were not found in the leaves (L) (Fig. 5a). At 60 DAT, the total bacterial concentration in Rs was similar among the 4 treatments, i.e., 6.2–6.9 log CFU/g plant. In Ri and Sh, the total bacterial concentrations in RFf, RBFf, and RFf-B were 5.1–5.5 and 5.0–5.4 log CFU/g plant, respectively, while those in RBFf-B were 3.9 and 4.4 log CFU/g plant, respectively. The total bacterial concentrations in L in RFf-B and RBFf-B were 4.6 and 2.1 log CFU/g plant, respectively (Fig. 5b). At 90 DAT, total bacteria were found only in Rs and Ri, i.e., 6.3–6.5 and 4.6–5.7 log CFU/g, respectively (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5.

Numbers of total bacteria on chitin agar isolated from different tissues of KDML105 rice plants grown under field conditions at (a) 30 DAT, (b) 60 DAT, and (c) 90 DAT. Ratio of the expected K. oryziphila NP19 and other bacteria at (d) 30 DAT, (e) 60 DAT, and (f) 90 DAT. Rs root surface, Ri root interior, Sh shoot, L leaf.

At 30 DAT in Rf, the percentages of the expected K. oryziphila NP19 were 52.9% and 33.3% in Rs and Ri, respectively. However, the expected K. oryziphila NP19 percentages in Rs, Ri, and Sh of RBf were 43.9%, 93.3%, and 100%, respectively. At 60 DAT, the percentages of expected K. oryziphila NP19 in Rs were 19.7%, 4.7%, and 19.5% in RFf, RBFf, and RBFf-B, respectively, whereas in Ri, they were 50.0%, 75.9%, and 41.5% in RFf, RBFf, and RBFf-B, respectively. In shoot, RBFf and RBFf-B had 0.1% and 9.0% of the expected K. oryziphila NP19, respectively, whereas in L, a value of 100% was found in RBFf-B. At 90 DAT, K. oryziphila NP19 was detected in RBFf, at 2.1% (in Rs) and 7.2% (in Ri), and in RBFf-B, at 18.6% (in Rs) and 25.7% (in Ri) (Fig. 5d–f).

The expected K. oryziphila NP19 colonies were random according to 16S rDNA sequencing, and the results showed that K. oryziphila was not found in RFf but was found in RFf-B at 60 DAT. In addition, the bacteria from the 4 treatments were also similar to Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Burkholderia multivorans, Burkholderia diffusa, Pantoea dispersa, Burkholderia vietnamiensis, Chryseobacterium gleum, and Xanthomonas sacchari (data not shown).

Effects of K. oryziphila NP19 on the antioxidant response of KDML105 rice in field experiments

The effects of K. oryziphila NP19 on the antioxidant enzyme activity, proline content, and lipid peroxidation of KDML105 in the field experiment are shown in Fig. 6. Peroxidase activity in leaves slightly decreased by 13.6% and 7.3% in RBf compared to that in the Rf at 0 and 30 DAT, respectively. On the other hand, at 60 DAT, POD activity in RBFf and RBFf-B increased, by 64.3% (compared to RFf) and 14.3% (compared to RFf-B), respectively. In addition, POD activity in RFf-B increased slightly, by 4.2%, compared to that in RFf. At 90 DAT, POD activity decreased by 31.0% and 3.4% in RBFf and RBFf-B compared to that in RFf and RFf-B, respectively, whereas POD activity in RFf-B decreased slightly by 9.4% compared to that in RFf (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

Antioxidant response in the leaves of KDML105 rice plants grown under field conditions with and without rice blast disease infection. (a) Peroxidase activity, (b) superoxide dismutase activity, (c) proline content, (d) malondialdehyde content. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments at the same time based on the LSD test.

Superoxide dismutase activity in RBf significantly increased by 19.6% and 28.8% compared to that in Rf at 0 and 30 DAT, respectively. However, compared with that in RFf, SOD activity in RBFf decreased slightly by 15.4%, whereas SOD activity in RBFf-B increased slightly by 7.8%. After the application of K. oryziphila NP19 to the plots at 58 DAT, the SOD activity at 60 DAT increased in RFf-B and RBFf-B, by 9.0% and 38.7%, respectively, compared to that in RFf and RBFf. At 90 DAT, SOD activity in RBFf increased slightly, by 6.9%, compared to that in RFf. In addition, the SOD activity in RFf-B and RBFf-B increased, by 29.6% and 21.1%, respectively, compared to that in RFf and RBFf (Fig. 6b).

The proline content in leaves did not differ significantly between Rf and RBf at 0 and 30 DAT. At 60 DAT, the proline content in the RBFf increased, by 53.5%, compared to that in the RFf. After the application of K. oryziphila NP19 to the plots at 58 DAT, the proline content in RFf-B increased slightly, by 12.1%, compared to that in RFf, but there was no difference between RBFf-B and RBFf. Interestingly, the proline content in RBFf-B was greater than that in RFf-B by 36.0%. At 90 DAT, the proline content in RFf-B and RBFf increased, by 28.0% and 5.7%, respectively, compared to that in RFf (Fig. 6c).

The MDA content in leaves differed significantly between RFf and RBFf at 30 DAT. The MDA content in RBf was 68.5% greater than that in Rf. At 60 DAT, the MDA content in RBFf, RFf-B, and RBFf-B decreased, by 19.4%, 25.6%, and 5.3%, respectively, compared to that in RFf. However, the MDA content in RBFf-B increased, by 27.3%, compared to that in RFf-B. Similar to the results at 60 DAT, the MDA content in RBFf, RFf-B, and RBFf-B decreased slightly, by 9.1%, 11.8%, and 0.8%, respectively, compared to that in RFf (Fig. 6d).

Rice blast severity in KDML105 rice in the field experiment

Blast lesions (code 7) were found in 4 treatments, but the severity differed in terms of the leaf area. In RFf, lesions covered 14.0% of the leaf area at 58 DAT and increased to 39.0% of the leaf area at 106 DAT. In RBFf, lesions covered 4.0% of the leaf area at 58 DAT and increased to 13.0% of the leaf area at 106 DAT. After the application of K. oryziphila NP19 to the plots at 58, 61, and 72 DAT, the lesions covered 25.0% of the leaf area in RFf-B at 58 DAT and increased slightly to 28.0% and 27.0% at 86 and 106 DAT, respectively. Interestingly, in RBFf-B, the lesions covered 20.0% of the leaf area at 58 DAT and decreased to 17.0% and 8.0% at 86 and 106 DAT, respectively (see Supplementary Fig. S3 online).

Discussion

Kosakonia oryziphila NP19 suppressed the mycelial growth of P. oryzae in potato dextrose broth (PDB). In addition, K. oryziphila NP19 inhibited rice blast conidial development on KDML105 rice seedling leaves. Bacteria can produce chitinase enzymes that damage chitin in the fungal cell wall. Streptomyces globisporus JK-1 produces a biocontrol agent to suppress rice blast fungi15. Furthermore, Santoyo et al.16 reported that extracellular hydrolytic enzymes degrade plant pathogenic microbe cell walls. Rhizobacteria may also activate defense mechanisms in plants, including cell wall reinforcement, phytoalexin production, and pathogenesis-related proteins synthesis17.

Under greenhouse conditions, K. oryziphila NP19 may enhance plant growth by improving photosynthetic pigments. Although the disease lesion area was less than 1%, the pigment contents in the rice leaves decreased by 12.0–42.7%. Surprisingly, the pigment contents in colonized rice increased, by 0.2–49.2%, under fungal infection (Fig. 2). In addition, the number of filled grains per panicle, filled grain yield, and harvest index were greater in RBF treatment than in RF (Table 1). Under field conditions without fungal infection, the pigment contents of K. oryziphila NP19- colonized rice were slightly greater than those of uncolonized rice by 1.1–6.5% (Fig. 4d). In addition, compared with RFf, K. oryziphila NP19 increased the percentage of filled grains to more than 9.2% (Table 2). Blast disease has negative effects on plant height, the number of tillers, panicle length, and chlorophyll content, leading to a reduction in yield18. Rice blast fungal infection depends on a suitable environment (extended periods of leaf dampness, favorable conditions at 25–28 °C and 92.0–96.0% relative humidity), host variety, and specific fungal strains19,20.

We conducted pot experiments from July to September 2020, with a mean temperature of 27.36 °C (range 24.11–30.82 °C) and a mean relative humidity (RH) of 80.1% (range 63.8–95.3%) (see Supplementary Fig. S5a online). At the tillering stage (1–30 DAT), the temperature and RH were 28.64 °C and 76.8%, respectively. The field experiment was conducted from July to September 2021, and the mean temperature was 27.38 °C (range 24.11–30.82 °C), and the mean RH was 80.6% (range 63.8–95.3%) (see Supplementary Fig. S5b online). In this study, relative humidity was lower than 92.0%, which may not be favorable for sporulation and lesion development. Moreover, growth parameters and grain yield were not affected in the pot experiment. However, the effects of K. oryziphila NP19 on filled grain yield, grain yield, and the progression of blast lesions in field experiments were quite clear in terms of rice blast fungal treatment after infection.

According to many studies, sulfur (S) fertilizer increases crop resistance to fungal pathogens. Plants can develop leaf blast diseases due to high levels of magnesium (Mg), a constituent of chlorophyll21. Zinc (Zn) is directly toxic to pathogens and has been found to reduce disease severity22. In the present study, field experiments revealed the progression of blast areas on rice leaves despite higher phosphorus (P), potassium (K), S, and Zn concentrations than in the pot experiments. Soil nutrition may not have affected the rice blast disease control because the relative humidity and air temperature were not favorable for severe pathotype infections.

As factors that control various diseases caused by microorganisms, nutrients play essential roles in plant growth and development. The mineral nutrients of a plant determine its resistance to disease, its morphological or histological characteristics, and its virulence or ability to survive infection by pathogens21. Phosphorus delays the onset and reduces the severity of rice blast disease, probably by increasing phenolic synthesis23. In general, potassium reduces the incidence of various diseases, such as blast, bacterial leaf blight, sheath blight, stem rot, and leaf spot diseases, in rice21,24,25. A previous study conducted by Perrenoud26 revealed that high levels of K also reduce the incidence of fungal diseases in rice and increase crop yields. Sulfur fertilizer increases crop resistance to fungal pathogens according to many studies27. Plants can develop leaf blast diseases due to high levels of Mg, a constituent of chlorophyll21. Zinc toxifies pathogens directly, reducing disease severity22. Field experiments showed the progression of blast areas on rice leaves despite higher P, K, S, and Zn concentrations than pot experiments. Soil nutrition may not affect rice blast disease control because relative humidity and air temperature are not favorable for severe pathotype infections.

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, P. dispersa, X. sacchari, B. multivorans, B. diffusa, B. vietnamiensis, and C. gleum were detected in all treatments in the field experiment. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia species have been isolated from the rhizosphere of wheat, oat, cucumber, maize, and potato plants and show biocontrol activity against Colletotrichum nymphaeae28. Moreover, the effectiveness of P. dispersa as a biocontrol agent for black rot in sweet potato has been reported29. In addition, the X. sacchari R1 strain exhibits antagonistic effects on Burkholderia glumae-induced blight and dirty panicles in rice30. It is possible that K. oryziphila NP19 develops symbiotic relationships with rice tissues during rice germination and becomes an indigenous symbiont in some species of rice. There are other soil bacteria that can colonize rice after transplantation, but K. oryziphila NP19 affects several factors involved in rice blast defense mechanisms after colonization. Kosakonia oryziphila NP19 not only suppressed P. oryzae growth by over 50.0% (see Supplementary Table S1 online), but also reduced the number of blast lesions in the leaf area and improved yield of rice colonized and/or inoculated with K. oryziphila NP19 (RBf, RFf-B, and RBFf-B) in field experiments (Fig. S3).

Pyricularia oryzae is a hemibiotrophic fungus that requires host nutrients during infection. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced in plants to inhibit fungal infection; however, P. oryzae uses several strategies to respond to host ROS31. Peroxidase appears to play a role in pathogen resistance, including crosslinking of cell wall proteins, xylem wall thickening, production of reactive oxygen species, and hydrogen peroxide scavenging32. An antioxidant enzyme can act as a specific ROS cleanup system. Due to their antioxidant effects, SOD and POD help initiate a defense response, where SOD acts as a first line of defense33. In rice, plant peroxidase activity is induced after infection with plant pathogens such as rice blast fungus and Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae32. In this study, peroxidase activity increased in rice colonized and/or inoculated with K. oryziphila NP19; however, rice blast fungus did not affect peroxidase activity. Superoxide dismutase acts as a H2O2 synthetase, catalyzing the reduction of O• 2 − into H2O2. Superoxide dismutase is a key factor against several stresses by balancing H2O2 concentrations in plants, leading to tolerance against various stresses34. In this study, at 30 DAT in the pot experiment, the SOD activity in RF and RBF was 121.9% and 104.5% greater than that in R, respectively, which indicated that SOD responded to blast infection. In both pot experiment and field condition, K. oryzae NP19-colonized rice showed increases in SOD activity by 67.7% and 28.8%, respectively, when compared to uncolonized rice at 30 DAT. The biochemical responses of plants depend on the environment, stress sources, and type of plant35. Plant antioxidant enzyme activity is directly affected by environmental factors by altering the microbiota of plants33.

Proline is a proteogenic amino acid that is synthesized in the plant cytosol and accumulates in the chloroplast. Under adverse conditions, proline maintains redox balance and stabilizes cellular structures as an osmoprotectant36. Vurukonda et al.37 reported that PGPR increased proline content, which was higher in water-stressed crops. In this study, proline levels were not significantly different between control and infected rice based on the pot experiment. However, proline in the K. oryziphila NP19 treatment (RFf-B) group increased by up to 28.0% in the field experiment. Antioxidant enzyme activities were measured in the leaves, and SOD could be the dominant enzyme involved in balancing stress toxicity. Bhattacharyya et al.38 reported that rhizobacterial treatment in rice induced catalase activity, ascorbate peroxidase activity, chitinase activity, and proline production, which primed plants toward stress mitigation.

2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline is a key aroma compound of cooked rice and varies in its levels, depending on the planting location39. The role of PGPR in 2AP production in rice may involve the optimum number of rhizobacteria in rice tissue and the ability of bacteria to solubilize phosphorus, solubilize potassium, and produce siderophores1. In this study, K. oryziphila NP19-colonized rice had a 7.5–10.1% greater 2AP content in the pot experiment. Surprisingly, the 2AP content in the colonized rice (RBFf) and the treatments sprayed with K. oryziphila NP19 (RFf-B and RBFf-B) increased by 18.0–35.8% in the field experiment. These results suggest that K. oryziphila NP19 can be applied to improve the grain quality of KDML105 in an alternative manner.

Precursors for 2AP biosynthesis, such as proline, ornithine, and glutamate, were found. Environmental factors affect rice aroma, and soil salinity is positively related to 2AP synthesis40. Chinachanta et al.1 reported that Sinomonas sp. ORF15-23 may enhance 2AP production in KDML105 under salt stress. In the pot experiment, the 2AP content in the grain was 329.7–363.2 ng/g rice, whereas in the field experiment, the content was 187.02–253.98 ng/g rice (Tables S3, S4). In this study, the electrical conductivity (EC) in the pot and field experiments were found to be 0.020 and 0.033 dS/m, respectively, which are similar to those detected in nonsaline soil (see Supplementary Table S2 online). However, the sodium (Na) level in the pot experiment was 2.7 × greater than that in the field experiment, which may have led to greater 2AP accumulation. Changsri et al.41 reported that the addition of Na to a nutrient solution resulted in a greater 2AP level in rice. Overall, K. oryziphila NP19 demonstrated its potential as a candidate before being applied as a plant growth-promoting bioagent and biopesticide to suppress rice blast and should be further investigated with various strains of fungal pathotypes under field conditions.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms and culture conditions

Kosakonia oryziphila NP19 (NCBI accession number PP861312) used in this study is a rice root-associated strain isolated from RD6 rice roots in Nakhon Phanom Province, Thailand (16° 59′ 42.9" N 104° 22′ 17.9" E)13. The bacteria were grown in nutrient broth (NB) at 30 °C and 150 rpm for 18 h. The optical density at 600 nm of cell suspension was measured to calculate the cell concentration. The cell suspension was adjusted to 106 CFU/mL with sterilized deionized water (dH2O). Pyricularia oryzae was point inoculated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) and incubated at 25 °C for 7 days. The fungal mycelia were transferred to rice bran agar (2% (w/v) rice bran, 0.5% (w/v) sucrose, and 2% (w/v) agar in dH2O at pH 7) and incubated at 25 °C for 7 days. A sterilized leaf of a blast fungus-susceptible rice variety (KDML105) was placed on the fungal mycelia to induce sporulation and incubated at 25 °C under violet and white light together for 5 days. The conidia were harvested in 10 mL of sterilized 0.025% (v/v) Tween 20 by gentle scrubbing of the mycelium and surface of the infected leaf. The fungal solution was filtered through 8 layers of cheesecloth to remove mycelia, agar, and rice leaves. The conidial suspension was adjusted to 5 × 105 conidia/mL for further study.

Plant material preparation

Seeds of Thai jasmine rice (KDML105) were provided and authorized by Khon Kaen Rice Research Center, Thailand. The seeds were sterilized with ethanol and 0.2% (w/v) mercuric chloride, and then the surface-sterilized seeds were incubated in the dark until the roots germinated. To colonize the bacteria into rice, 5 mL of 106 CFU/mL K. oryziphila NP19 was added to 150 germinated seeds and incubated for 2 days in the dark. The K. oryziphila NP19-colonized rice seeds were prepared using the same method and used for leaf, pot, and field experiments. To determine the effects of NP19 cell suspension on P. oryzae infection in KDML105 leaf experiments, colonized rice seedlings (RB) were transferred to Hoagland’s agar medium (202 g KNO3, 472 g Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 493 g MgSO4·7H2O, 115 g NH4H2PO4, 2.86 g H3BO3, 1.81 MnCl2·4H2O, 0.22 g ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.08 g CuSO4·5H2O, 0.02 g MoH2O4·H2O, and 15 g Fe-EDTA per liter)42 for 7 days under 14/10 h light/dark conditions and 70% humidity at 25 °C. Rice seedlings without bacterial colonization were used as the control (R).

For the pot experiment, rice seeds were surface sterilized, geminated, and colonized with K. oryziphila NP19 as previously described, then transferred to plug tray and cultivated for 30 days to produce rice seedlings. The rice seedlings were then transplanted to pots. Rice plants were fertilized while growing in pots to prepare them for rice blast fungal infection and tested for antagonism.

For the field experiments, germinated and K. oryziphila NP19-colonized seeds were prepared using the same method as previously described and separated into 2 treatment groups: those colonized with K. oryziphila NP19 (RB) and those without bacterial colonization (R). The germinated seeds were transferred to plug trays with sterilized soil (a mixture of soil, burnt rice husk and manure at 7:2:1 (w/w/w)) for 30 days.

Effects of K. oryziphila NP19 cell suspension on P. oryzae infection of rice leaves

Kosakonia oryziphila NP19 fresh cell culture was prepared by cultivation in NB at 37 °C for 24 h. After centrifugation at 3047×g for 10 min, the cell pellet was harvested, washed twice with 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) and resuspended in the same buffer. The optical density of the cell suspension was measured at 600 nm to obtain a value of ~ 1.0 (equal to 1.0 × 107 CFU/µL when measured by the spread plate technique on a nutrient agar plate). P. oryzae fungal conidia were prepared by suspension in PBS solution and counted using hemacytometer. K. oryziphila NP19 cell and P. oryzae conidia suspensions were prepared at 1.0 × 107 CFU/µL and 5.0 × 102 conidia/µL, respectively and used for the spot test on fresh rice leaf segment. For rice sample preparation, rice seedling leaves were cut to a length of 5 cm. The leaf segments were placed in petri plates with moist absorbent paper. Five groups for the following treatments were established: (i) R: rice leaf segment control without bacterial colonization dropped with 0.025% (v/v) Tween 20 solution, (ii) RB + F: rice colonized with K. oryziphila NP19 dropped with 2 µL of P. oryzae conidial suspension, (iii) R + BF: R rice dropped with a 4-µL mixture of P. oryzae conidial suspension and K. oryziphila NP19 at a ratio of 1:1 (v/v), (iv) R + F: R rice dropped with 2 µL of P. oryzae conidial suspension, and (v) RF + B: R rice dropped with 2 µL of P. oryzae conidial suspension, and after 30 h of incubation, 2 µL of K. oryziphila NP19 was dropped onto the same spot. All plates were incubated at 25 °C in darkness for 30 h and then under constant light. For each group, three replications were conducted. After 72 h of incubation, the plant segments were observed and subjected to SEM. Briefly, plant segments were fixed in phosphate buffer containing 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and dehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions. The sample was critical point-dried with CO2, after which the samples were coated with gold and observed using scanning electron microscopy15.

Suppression of mycelial growth of P. oryzae by K. oryziphila NP19 cell

Kosakonia oryziphila NP19 was grown in 100 mL of NB for 18 h, and the bacterial cell culture was centrifuged at 4025×g for 15 min at 4 °C and washed three times with PDB to remove the supernatant. One hundred milliliters of PDB was added to the K. oryziphila NP19 cell pellet for resuspension. Resuspended K. oryziphila NP19 was measured at an optical density of 600 nm (OD600) to reach 1010 CFU/mL by comparing to an OD600 and cell density (CFU/mL) standard curve as counted by the spread plate technique on PDA. The K. oryziphila NP19 cell suspension was diluted and added to PDB at final concentrations of 5.0 × 107, 1.0 × 108, 1.0 × 109 and 2.0 × 109 CFU/mL in a 125 mL flask. Five mycelial plugs of P. oryzae on PDA were transferred to each flask. Potato dextrose broth with mycelial plugs and without K. oryziphila NP19 cells was used as a control. After incubation at 25 °C for 7 days, the cultures were filtered to harvest mycelia on dry preweighed filter paper. The mycelia were dried at 60 °C for 3 days and weighed15.

Pot and field experiments

Soil preparation, plant management, and application of bacteria and fungal pathogen

For the pot experiment, soil was collected from a paddy field in Khon Kaen Province, Thailand, in 2020. The soil was air-dried, sieved and sterilized by high-temperature steam. The soil properties are shown in Supplementary Table S2 online. The experimental design consisted of a randomized complete block design with one plant per pot, 60 plants (plots) per treatment, 20 plants per replicate, and 3 replicates per treatment. Kosakania oryziphila NP19 was colonized into KDML105 rice as previously described. Khao Dawk Mali 105 rice seedlings were transferred to pots and separated into 4 treatment groups: (1) R: rice without K. oryziphila NP19 colonization, (2) RB: rice colonized by K. oryziphila NP19, (3) RF: rice + fungal infection, and (4) RBF: rice colonized by K. oryziphila NP19 + fungal infection (Supplementary Table S3 online). Twelve seedlings were employed per treatment, and one seedling was transplanted to a pot container. Nitrogen-P-K 16–20-0 and 46–0-0 fertilizers were applied at 187 kg/ha (at 15 DAT) and 31 kg/ha (at 45 DAT) based on the rate recommended by the Rice Department, Thailand43. In addition, to induce rice blast fungal infection, 46–0-0 fertilizer was applied at 46.5 kg/ha at 15 DAT. In the RF and RBF treatments, 15 mL of a P. oryzae conidial suspension at 5.0 × 105 conidia/mL was sprayed twice per pot to the rice plants at the tillering stage at 17 and 20 DAT. After spraying, the inoculated plants were covered in plastic bags for 24 h44.

The field experiment was conducted in a paddy field in Ta Kra Serm, Nam Phong District, Khon Kaen Province, Thailand (16° 37′ 36.4" N 102° 51′ 43.6" E), in 2021. The soil properties are shown in Supplementary Table S2 online. Soil preparation was carried out using conventional tillage methods, including primary and secondary plowing and harrowing. The experimental design consisted of a randomized complete block design with 576 plants per treatment, 96 plants per replicate, and 12 replications (plots) for Rf and RBf treatments. For RFf, RBFf, RFf-B, and RBFf-B, there were 6 replications (plots) per treatment. Each plot measured 2 × 3 m with 25 cm spacing between rows and plants and contained 96 plants per plot. There was a 94 kg/ha application of NPK 16-20-0 and a 37 kg application of urea fertilizer (46-0-0) applied after 15 and 45 DAT, respectively42. Rice seedlings were transferred to paddy fields and subjected to 6 treatments: (i) Rf: rice without K. oryziphila NP19 colonization and no blast infection during 0–57 DAT (12 plots), (ii) RBf: rice colonized with K. oryziphila NP19 and no blast infection during 0–57 DAT (12 plots), (iii) RFf: Rf-rice infected by natural blast fungi at 58 DAT until harvest (6 plots), (iv) RBFf: RBf rice infected by natural blast fungi at 58 DAT until harvest (6 plots), (v) RFf-B: RFf rice sprayed by K. oryziphila NP19 at 58, 61, and 65 DAT (6 plots), and (vi) RBFf-B: RBFf rice sprayed by K. oryziphila NP19 at 58, 61, and 65 DAT (6 plots) (Supplementary Table S3 online). A urea fertilizer at 50% higher than the normal level was applied to the rice plants 15 DAT to induce natural rice blast fungal infection. After blast infection, 180 mL of 109 CFU/mL K. oryziphila NP19 cell suspension was sprayed 3 times (at 58, 61, and 65 DAT) in each plot of RFf-B and RBFf-B.

Determination of plant growth, pigment contents, and yield

In the pot experiment, a total of three replications (9 plants) were conducted per treatment for each sample collection to determine total biomass, pigment contents, and yield. In the field experiment, a total of six replications (30 plants) were conducted per treatment for each sample collection to determine total biomass, pigment contents, and yield.

At 30, 60, and 90 DAT and at the harvest stage, the total biomass was determined by drying the plants at 80 °C until constant weight, after which the dried plants were weighed. The contents of pigments, including chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids, in leaves were extracted with 10 mL of 80% (v/v) acetone, and then the extracts were measured using a spectrophotometer (Genesys 10 s UV‒VIS Spectrophotometer). The pigments were calculated based on a published equation45.

To determine grain yields at harvest, 9 plants from each treatment (3 plants per replicate) were collected in the pot experiment, and 30 plants from each treatment (5 plants per plot) were collected in the field experiment. The panicle number per plant, panicle length, filled-grain percentage, and 1000-grain weight were determined. The yield of the filled-grain weight was measured from 9 plants per treatment in the pot experiment and 1 m2 per plot for each treatment in the field experiment. The harvest index was computed as the ratio of the total grain weight to the total biomass at the final harvest.

Determination of rice grain quality

Milled grains were ground for total starch, amylose content, and total protein determination. The total starch and amylose contents were measured following Timabud et al.46 with some modifications. Rice powder, 2 mL of dH2O and 2 mL of 2 M NaOH were mixed to prepare a starch slurry. The slurry was shaken at room temperature overnight, and then 4 mL of 1 M HCl was added to neutralize the homogenate. The homogenate was diluted in dH2O (1:30 dH2O). Total starch was measured using the starch-iodine assay. A mixture of 40 µL of starch slurry, 40 µL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and 20 µl of 1 M HCl was used. This was followed by the addition of 100 µL of iodine reagent (5 mM I2 and 5 mM KI) and measurement at 580 nm on a spectrophotometer. Total starch content was calculated using a standard soluble starch curve (25, 50, 100, 125, 150 mg of soluble starch). The amylose content was measured by mixing 250 µL of starch slurry with 1 mL of iodine reagent (0.3% w/v I2 and 1.5% w/v KI), and after 5 min of reaction at room temperature, the absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured by a spectrophotometer at A620 nm and A535 nm. The percentage of amylose was calculated as follows: 1.4935*exp(2.7029 × ratio A620:A535).

Total protein was extracted using polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) following Kiran and Sandeep47. A mixture of 0.5 g of grain powder with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer and 10% (v/v) insoluble PVP was incubated at 40 °C overnight. The homogenate was centrifuged at 4 °C and 12,225×g for 20 min. The total protein in the supernatant was measured using the Bradford protein assay.

The 2AP content was defined as the aroma volatile fraction of 2AP that was measured following the methods of Timabud et al.46 with some modifications. Rice grains were kept in a GC vial with a cap at − 80 °C until analysis. The rice grains were dehusked and ground in liquid nitrogen. Fifty milligrams of rice powder was added to a 10 mL headspace vial, and then 5 µL of 2 ng/µL 2,4-dimethyl pyridine (DMP) was added, after which the vial was capped with a PTFE/silicone cap. 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline was measured by gas chromatography‒mass spectrometry (Agilent Technologies series 5977B Inert Plus MSD/GC 8890 with a headspace system) under the following conditions:

Oven temp.: 80 °C.

Inlet-F temp.: 50 °C, 5 °C/min to 120 °C.

Column flow: 1.0

Headspace oven temp.: 140 °C (15 min).

Inlet-B temp.: 250 °C.

MS source: 230 °C.

MS quad: 150 °C.

Helium flow: 0.6 mL/min.

Sample injection: 5 µL.

The 2AP content was calculated using a standard curve of a peak area ratio of 2AP/DMP with the concentration of the 2AP standard at 0.03–0.60 mg/g.

Determination and identification of K. oryziphila NP19 colonization in rice plants

Kosakonia oryziphila NP19 colonization was determined on the rice root surface and inside the roots, shoots and leaves at 30-day intervals. The bacterium was extracted in sterile normal saline (0.85% (w/v) NaCl). Extracted bacterial samples were cultured on chitin agar and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. The colony morphology of K. oryziphila NP19 after incubation on chitin agar at 30 °C for 24 h was as follows: circular form, raised elevation, entire margin, translucent, and ~ 2 mm diameter. The expected amount of K. oryziphila NP19 and the total number of bacteria on chitin agar were counted. Colonies of chitinase-producing bacteria were counted and randomly identified by 16S rDNA.

Determination of antioxidant enzymes, proline, and malondialdehyde

During the pot and field experiments, antioxidant enzyme activities and MDA content were measured at 0, 30, 60, and 90 DAT. The extraction of crude enzymes was performed according to Ali et al.48 with some modifications. Khao Dawk Mali 105 leaves were ground in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C until use. Crude enzymes were extracted from one hundred milligrams of leaf powder homogenized in 1 mL of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 1% (w/v) PVP. A homogenate of the mixture was centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min at 9660×g. The supernatants were collected to measure POD and SOD activities. The protein content in the supernatant was measured using a Bio-Rad protein assay.

Peroxidase activity was determined according to the methods of Thanwisai et al.49. Ten microliters of crude enzyme was added to 1 mL of reaction mixture (50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 7) and 0.3 mM guaiacol). The reaction was initiated after the addition of 0.1 M H2O2. The absorbance was measured at 470 nm. One unit is defined as the amount of enzyme producing 1 µmol/min of oxidized guaiacol. The activity is expressed as µmol/min/mg protein.

Superoxide dismutase activity was measured following the methods of Thanwisai et al.49. Fifty microliters of crude enzyme and 10 µL of 1 mM riboflavin were added to 2 mL of reaction mixture (100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 2 mM EDTA, 9.9 mM l-methionine, 55 μM nitroblue tetrazolium chloride, 0.025% (w/v) Triton-X 100). The reaction was initiated by illumination for 10 min, and the absorbance was recorded at 560 nm. A reaction without crude enzyme under dark and illuminated conditions was used as a control. One unit is defined as the amount of enzyme required to cause 50% inhibition of the nitroblue tetrazolium photoreduction rate, and the results are expressed as U/mg protein.

Five hundred fresh leaves were extracted in 3% w/v 5′-sulfosalicylic acid. One milliliter of supernatant was mixed with 1 mL of the ninhydrin agent (1.25 g of ninhydrin, 20 mL of 6 M phosphoric acid, and 30 mL of acetic acid) and 1 mL of acetic acid, followed by 1 h of heating at 100 °C. A cold bath was used to stop the reaction, followed by vigorous mixing with 2 mL of toluene. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm49. A proline standard curve was used to calculate the proline content, which is presented as μmol/g fresh weight.

Malondialdehyde is used as a marker of lipid peroxidation under oxidative stress. A 500-mg rice leaf sample was ground in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 0.1% trichloroacetic acid. In the following step, 1 mL of the plant extract was mixed with 4 mL of 20% w/v trichloroacetic acid that contained 0.5% w/v thiobarbituric acid and heated at 95 °C for 30 min. Following cooling on ice, the mixture was centrifuged at 6,708 × g for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 532 and 600 nm. The concentration of MDA was calculated using an extinction coefficient of 155 mM−1 cm−150.

Evaluation of rice blast severity in KDML105 rice

The severity of rice blast was evaluated following the SES scoring system. The standard area diagram was generated based on 3 replicates and is presented as index values of 1–9 (see Supplementary Fig. S4 online). The predominant lesion type was considered codes 0–9, and codes 5, 7, and 9 were considered susceptible lesions (see Supplementary Table S3 online)51.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed for significant differences (p < 0.05) for each characteristic following a completely randomized design (CRD)52 using Statistix 853, and the means were compared by least significant difference (LSD) tests. The data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs) of at least 3 replicates.

Ethical approval

A license for the use of Oryza sativa L. cv. KDML105 seeds and rice blast fungi were granted by Khon Kaen Rice Research Center and Ubon Ratchathani Rice Research Center, Thailand, respectively. The methods used in this study comply with the national guidelines and legislation of the Rice Department, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Thailand.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The work was financially supported by the Post Doctoral Training Program from Khon Kaen University, Thailand (Grant No. PD2567-12), the Fundamental Fund of Khon Kaen University, and the Fundamental Fund from the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF), Thailand.

Abbreviations

- DMP

2,4-Dimethyl pyridine

- 2AP

2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline

- CAT

Catalase

- CFU

Colony forming units

- DAT

Days after transplanting

- EC

Electrical conductivity

- IAA

Indole acetic acid

- NP19

Kosakonia oryziphila NP19

- L

Leaves

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- NB

Nutrient broth

- RH

Mean relative humidity

- KDML105

Oryza sativa L. cv. Khao Dawk Mali 105

- RD6

Oryza sativa L. cv. RD6

- POD

Peroxidase

- PGPR

Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria

- PVP

Polyvinylpyrrolidone

- PDA

Potato dextrose agar

- PDB

Potato dextrose broth

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- Ri

Root interior

- Rs

Root surface

- Sh

Shoot

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

Author contributions

L.T. methodology, formal analysis, data curation, investigation, writing—original draft. W.S. conceptualization, resources, writing—review and editing. S.S. conceptualization, methodology, resources, supervision, validation, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-68097-0.

References

- 1.Chinachanta, K., Shutsrirung, A., Herrmann, L., Lesueur, D. & Pathom-Aree, W. Enhancement of the aroma compound 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline in Thai Jasmine Rice (Oryza sativa) by rhizobacteria under salt stress. Biology.10(10), 1065. 10.3390/biology10101065 (2021). 10.3390/biology10101065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, Z. et al. The antagonistic mechanism of Bacillus velezensis ZW10 against rice blast disease: Evaluation of ZW10 as a potential biopesticide. Plos. One.16(8), e0256807. 10.1371/journal.pone.0256807 (2021). 10.1371/journal.pone.0256807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damchuay, K. et al. Genetic distribution of the avirulence gene AVRPiz-t in Thai rice blast isolates and their pathogenicity to the broad-spectrum resistant rice variety Toride 1. Plant Pathol.71(2), 334–343. 10.1111/ppa.13482 (2022). 10.1111/ppa.13482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Law, J. W. F. et al. The potential of Streptomyces as biocontrol agents against the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae (Pyricularia oryzae). Front. Microbiol.8, 3. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00003 (2017). 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.TeBeest, D. O., Guerber, C. & Ditmore, M. Rice blast. Plant. Health. Instr.10.1094/PHI-I-2007-0313-07 (2007). 10.1094/PHI-I-2007-0313-07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Javaid, A., Ali, A., Shoaib, A. & Khan, I. H. Alleviating stress of Sclertium rolfsii on growth of chickpea var. Bhakkar-2011 by Trichoderma harzianum and T. viride. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 31(6), 1755–1761. 10.36899/JAPS.2021.6.0378 (2021).

- 7.Khan, I. H. & Javaid, A. In vitro screening of Aspergillus spp. for their biocontrol potential against Macrophomina phaseolina. J. Plant Pathol. 103(4), 1195–1205. 10.1007/s42161-021-00865-7 (2021).

- 8.Zarandi, M. E. et al. Biological control of rice blast (Magnaporthe oryzae) by use of Streptomyces sindeneusis isolate 263 in greenhouse. Am. J. Appl. Sci.6(1), 194–199. 10.3844/ajas.2009.194.199 (2009). 10.3844/ajas.2009.194.199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javaid, A., Anjum, F. & Akhtar, N. Molecular characterization of Pyricularia oryzae and its management by stem extract of Tribulus terrestris. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 21(6), 1256–1262. 10.17957/IJAB/15.1019 (2019).

- 10.Javaid, A., Ali, A., Shoaib, A., & Khan, I. H. Alleviating stress of Sclertium rolfsii on growth of chickpea var. Bhakkar-2011 by Trichoderma harzianum and T. viride. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 31(6), 1755–1761. 10.36899/JAPS.2021.6.0378 (2021).

- 11.El-Saadony, M. T. et al. Plant growth-promoting microorganisms as biocontrol agents of plant diseases: Mechanisms, challenges and future perspectives. Front. Plant. Sci. 13; 10.3389/fpls.2022.923880 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Sharf, W., Javaid, A., Shoaib, A. & Khan, I. H. Induction of resistance in chili against Sclerotium rolfsii by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and Anagallis arvensis. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control.31, 16. 10.1186/s41938-021-00364-y (2021).

- 13.Javed, S. et al. Effect of necrotrophic fungus and PGPR on the comparative histochemistry of Vigna radiata by using multiple microscopic techniques. Microsc. Res. Tech.84(11), 27372748. 10.1002/jemt.23836 (2021). 10.1002/jemt.23836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaowanaprasert, A., Thanwisai, L., Siripornadulsil, W. & Siripornadulsil, S. Biocontrol of blast disease in KDML105 rice by root-associated bacteria. Eur. J. Plant Pathol.10.1007/s10658-024-02901-5 (2024). 10.1007/s10658-024-02901-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, Q. et al. Suppression of Magnaporthe oryzae by culture filtrates of Streptomyces globisporus JK-1. Biol. Control.58(2), 139–148. 10.1016/J.BIOCONTROL.2011.04.013 (2011). 10.1016/J.BIOCONTROL.2011.04.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santoyo, G., Urtis-Flores, C. A., Loeza-Lara, P. D., Orozco-Mosqueda, M. D. C. & Glick, B. R. Rhizosphere colonization determinants by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). Biology.10(6), 1–18. 10.3390/biology10060475 (2021). 10.3390/biology10060475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González-Lamothe, R. et al. Plant antimicrobial agents and their effects on plant and human pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci.10(8), 3400. 10.3390/IJMS10083400 (2009). 10.3390/IJMS10083400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rais, A., Shakeel, M., Hafeez, F. Y. & Hassan, M. N. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria suppress blast disease caused by Pyricularia oryzae and increase grain yield of rice. BioControl.61, 769–780. 10.1007/s10526-016-9763-y (2016). 10.1007/s10526-016-9763-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asibi, A. E., Chai, Q. & Coulter, J. A. Rice blast: A disease with implications for global food security. Agronomy.9(8), 451–464 (2019). 10.3390/agronomy9080451 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kongcharoen, N., Kaewsalong, N. & Dethoup, T. Efficacy of fungicides in controlling rice blast and dirty panicle diseases in Thailand. Sci. Rep.10(1), 1–7. 10.1038/s41598-020-73222-w (2020). 10.1038/s41598-020-73222-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahman, M. T. et al. Mineral nutritional status of blast infected rice plant and allied soil. J. Bangladesh. Agric. Univ.18(2), 395–404. 10.5455/JBAU.81279 (2020). 10.5455/JBAU.81279 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham, D. R. & Webb, M. J. Micronutrients and disease resistance and tolerance in plants in Micronutrients in Agriculture 2nd edn (ed. Mortvedt, J. J., Cox, F. R., Shuman, L. M. & Welch, R. M.) 329–370 (USA, 1991).

- 23.Tiwari, K. N. Rice production and nutrient management in India. BCI.16, 18–22 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber, D. M. & Graham, R. D. The role of nutrition in crop resistance and tolerance to disease. In Mineral nutrition of crops fundamental mechanisms and implications (ed. Rengel, Z.) 205–266 (New York, 1999).

- 25.Sharma, R. C. & Duveiller, E. Effect of Helminthosporium leaf blight on performance of timely and late-seeded wheat under optimal and stressed levels of soil fertility and moisture. Field. Crops. Res.89, 205–218. 10.1016/j.fcr.2004.02.002 (2004). 10.1016/j.fcr.2004.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrenoud, S. Potassium and Plant Health, second ed (Switzerland, 1990).

- 27.Haneklaus, S., Bloem, E. & Schnug, E. Disease control by sulphur induced resistance. Asp. Appl. Biol.79, 221–224 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alijani, Z., Amini, J., Ashengroph, M. & Bahramnejad, B. Volatile compounds mediated effects of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strain UN1512 in plant growth promotion and its potential for the biocontrol of Colletotrichum nymphaeae. Physiol. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 112, 101555. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2020.101555 (2020).

- 29.Jiang, L. et al. Potential of Pantoea dispersa as an effective biocontrol agent for black rot in sweet potato. Sci. Rep.9(1), 16354. 10.1038/s41598-019-52804-3 (2019). 10.1038/s41598-019-52804-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang, Y. et al. Genome sequence of Xanthomonas sacchari R1, a biocontrol bacterium isolated from the rice seed. J. Biotechnol.206, 77–78. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.04.014 (2015). 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, X. & Zhang, Z. A double-edged sword: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) during the rice blast fungus and host interaction. FEBS. J.289(18), 5505–5515. 10.1111/febs.16171 (2022). 10.1111/febs.16171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasaki, K. et al. Ten rice peroxidases redundantly respond to multiple stresses including infection with rice blast fungus. Plant. Cell. Physiol.45(10), 1442–1452. 10.1093/pcp/pch165 (2004). 10.1093/pcp/pch165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rais, A. et al. Antagonistic Bacillus spp. reduce blast incidence on rice and increase grain yield under field conditions. Microbiol. Res.208, 54–62. 10.1016/j.micres.2018.01.009 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Li, Y. et al. Osa-miR398b boosts H2O2 production and rice blast disease-resistance via multiple superoxide dismutases. New. Phytol.222(3), 1507–1522. 10.1111/nph.15678 (2019). 10.1111/nph.15678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovreškov, L. et al. Are foliar nutrition status and indicators of oxidative stress associated with tree defoliation of four mediterranean forest species?. Plants.11(24), 3484. 10.3390/plants11243484 (2022). 10.3390/plants11243484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meena, M. et al. Regulation of L-proline biosynthesis, signal transduction, transport, accumulation and its vital role in plants during variable environmental conditions. Heliyon. 5(12). 10.1016/J.HELIYON.2019.E02952 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Vurukonda, S. S. K. P., Vardharajula, S., Shrivastava, M. & SkZ, A. Enhancement of drought stress tolerance in crops by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Microbiol. Res.184, 13–24. 10.1016/J.MICRES.2015.12.003 (2016). 10.1016/J.MICRES.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhattacharyya, C. et al. Evaluation of plant growth promotion properties and induction of antioxidative defense mechanism by tea rhizobacteria of Darjeeling. India. Sci. Rep.10(1), 1–19. 10.1038/s41598-020-72439-z (2020). 10.1038/s41598-020-72439-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kongchum, M., Harrell, D. L. & Linscombe, S. D. Comparison of 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (2AP) in rice leaf at different growth stages using gas chromatography. Agric. Sci.13(2), 165–176. 10.4236/as.2022.132013 (2022). 10.4236/as.2022.132013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Renuka, N. et al. Co-functioning of 2AP precursor amino acids enhances 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline under salt stress in aromatic rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 3911. 10.1038/s41598-022-07844-7 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Changsri, R. et al. Factors affecting the quality of Thai Hom Mali ricehttps://agkb.lib.ku.ac.th/rd/search_detail/dowload_digital_file/328848/77669 (2015).

- 42.Hoagland, D. R. & Arnon, D. I. The water-culture method for growing plants without soil in California agricultural experiment station (Berkeley, 1950).

- 43.Pollution Control Department, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. Guidelines for reducing rice field pollution in a good practice manual.https://www.pcd.go.th/publication/4276 (2004).

- 44.Chen, X., Jia, Y. & Wu, B. M. Evaluation of rice responses to the blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae at different growth stages. Plant Dis.103(1), 132–136. 10.1094/PDIS-12-17-1873-RE (2019). 10.1094/PDIS-12-17-1873-RE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lichtenthaler, H. K. & Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: measurement and characterization by UV-VIS spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food. Anal. Chem. 1(1), F4.3.1-F4.3.8. 10.1002/0471142913.FAF0403S01 (2001).

- 46.Timabud, T., Yin, X., Pongdontri, P. & Komatsu, S. Gel-free/label-free proteomic analysis of developing rice grains under heat stress. J. Proteomics.133, 1–19. 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.12.003 (2016). 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiran, K. M. & Sandeep, B. V. Comparative study of proximate composition and total antioxidant activity in leaves and seeds of Oryza sativa and Myriostachya wightiana. Int. J. Adv. Res. Publ.4(2), 842–852 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ali, M. B., Chun, H. S. & Lee, C. B. Response of antioxidant enzymes in rice (Oryza sauva L. cv. Dongjin) under mercury stress. J. Plant. Biol. 45(3), 141–147. 10.1007/bf03030306 (2002).

- 49.Thanwisai, L., Janket, A., Tran, H. T. K., Siripornadulsil, W. & Siripornadulsil, S. Low Cd-accumulating rice grain production through inoculation of germinating rice seeds with a plant growth-promoting endophytic bacterium. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.251, 114535. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.114535 (2023). 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.114535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fukao, T., Yeung, E. & Bailey-Serres, J. The submergence tolerance regulator SUB1A mediates crosstalk between submergence and drought tolerance in rice. Plant. Cell.23(1), 412–427. 10.1105/tpc.110.080325 (2011). 10.1105/tpc.110.080325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.International Rice Research Institute. Standard evaluation system for rice 5th Edition (Philippines, 2013).

- 52.Gomez, K. A. & Gomez, A. A. Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research, second edition (New York, 1984).

- 53.Statistix8. Analytical Software, “Statistix 8 Users Manual,” Analytical Softwarehttps://www.scirp.org/(S(i43dyn45teexjx455qlt3d2q))/reference/References (2003).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.