Abstract

Microtubule organization in cells relies on targeting mechanisms. Cytoplasmic linker proteins (CLIPs) and CLIP-associated proteins (CLASPs) are key regulators of microtubule organization, yet the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Here, we reveal that the C-terminal domain of CLASP2 interacts with a common motif found in several CLASP-binding proteins. This interaction drives the dynamic localization of CLASP2 to distinct cellular compartments, where CLASP2 accumulates in protein condensates at the cell cortex or the microtubule plus end. These condensates physically contact each other via CLASP2-mediated competitive binding, determining cortical microtubule targeting. The phosphorylation of CLASP2 modulates the dynamics of the condensate-condensate interaction and spatiotemporally navigates microtubule growth. Moreover, we identify additional CLASP-interacting proteins that are involved in condensate contacts in a CLASP2-dependent manner, uncovering a general mechanism governing microtubule targeting. Our findings not only unveil a tunable multiphase system regulating microtubule organization, but also offer general mechanistic insights into intricate protein-protein interactions at the mesoscale level.

Subject terms: X-ray crystallography, Microtubules, Cytoskeletal proteins

This study shows that CLASP2, a microtubule-stabilizing protein, regulates microtubule targeting via a tunable condensate interaction, offering mechanistic insights into the dynamic organization of multi-condensates in response to cellular signals.

Introduction

Microtubules (MTs) are fundamental structural components of the cell, playing pivotal roles in a wide array of cellular processes, including mitosis, cell movement, and intracellular transport1–3. MTs possess intrinsic polarity, characterized by a slow-growing minus end and a fast-growing plus end4,5. The plus end of MTs exhibits a dynamic behavior, continually oscillating between phases of growth and shrinkage, allowing MTs to rapidly reconfigure in response to cellular signals6,7. MTs do not exist in isolation within the cell but instead form intricate patterns. For instance, in motile cells, MTs often form radial networks, while neuronal axons require parallel arrays of MTs for axonal transport and neuronal structure maintenance1,8,9. However, despite the importance of MT patterns in cellular processes, the molecular mechanisms governing the spatial organization of MTs in different cellular regions remain elusive.

The MT dynamics is regulated by a group of specialized proteins known as plus end tracking proteins (+TIPs) that selectively accumulate at the MT plus end10,11. Among the +TIPs, cytoplasmic linker proteins (CLIPs), CLIP-associated proteins (CLASPs), and ending-binding proteins (EBs), can act as molecular liaisons, modulating interactions between MTs and diverse cellular compartments, such as the cell cortex12. As one of the earliest identified +TIPs13, CLASPs play an essential role in MT organization within various cellular compartments by inhibiting MT shrinkage/catastrophe and repairing damaged MTs14–16. The CLASP gene has been found in a wide range of organisms, from yeast and plants to mammals13,17,18. Mammalian CLASPs contain two paralogs, CLASP1 and CLASP2, each consisting of three tumor-overexpressed-gene (TOG) domains for MT binding, a C-terminal CLIP-interacting domain, and two Ser-X-Ile-Pro (SxIP) motifs binding to EBs (Fig. 1a)19. The binding of CLASPs to different proteins regulates the localization of CLASPs in various cellular compartments through its CLIP-interacting domain19,20. For instance, CLIP170, a member of the CLIP family, guides CLASPs to the MT plus end and regulates their activity in preventing MT catastrophe13,14. GCC185, a Golgi coiled-coil protein, recruits CLASPs to the Golgi apparatus and promotes Golgi-directed microtubule growth21,22. Centromere-associated protein E (CENP-E), a kinesin motor, associates with CLASPs, facilitating the targeting of MTs to the kinetochore during cell division20,23. Additionally, CLASPs and membrane-associated scaffold protein LL5β are involved in the formation of the cortical MT stabilizing complex (CMSC), anchoring MTs to focal adhesions (FAs) at the cell cortex and regulating FA dynamics24,25. Despite the crucial role of the CLASP-mediated interactions in targeting MTs to the diverse cellular compartments, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain elusive.

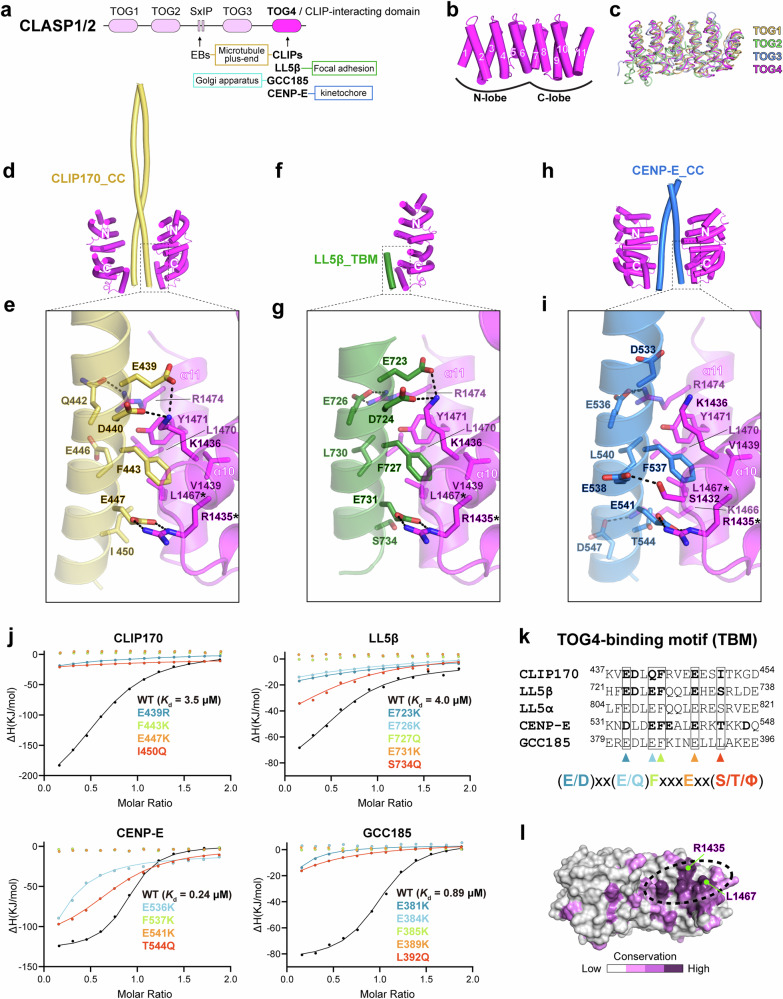

Fig. 1. Biochemical and structural characterization of TOG4-binding motifs.

a Domain organization of CLASP proteins, highlighting the regions responsible for interactions with various binding partners, essential for their cellular targeting. b Overall structure of the TOG4 domain in CLASP2, consisting of 11 α-helixes. c Structure alignment of the four TOG domains in CLASP2, showing the overall folding similarity. The PDB codes of the TOG1, TOG2, and TOG3 structures are 5NR4, 3WOY, and 3WOZ, respectively. d–i Structural analyses of the interactions between the TOG4 domain and its binding fragments in CLIP170 (d, e), LL5β (f, g), and CENP-E (h, i). Overall structures of these complexes are presented in (d, f–h) with detailed interface interactions shown in (e–g) and (i). Salt bridges and hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. j ITC-based analysis showing a similar interaction mode for TOG4-mediated interactions. Corresponding titration curves are listed in Fig. S3. The protein concentration of CLIP170_CC, LL5β_CC, CENP-E_CC, GCC185_CC, and their mutants in the syringe was 200 μM, and the protein concentration of CLASP2_TOG4 in the cell was 20 μM. k Sequence alignment of the TOG4-binding motifs (TBMs) in human CLIP170, LL5α, LL5β, GCC185 and CENP-E, highlighting the consensus sequence for TOG4 binding. Residues involved in TOG4 binding, as revealed by the structural analyses in (e–g) and (i) are shown in bold. l Surface conservation analysis of the TOG4 domain. The TBM-binding groove is indicated by a dashed circle.

In this study, we pinpointed the minimal CLASP-binding regions in CLIP170, LL5β, and CENP-E and determined the crystal structures of the CLASP2 C-terminal domain in complex with these CLASP-binding proteins. The structural findings revealed a common binding mode employed by these proteins to interact with a TOG-like fold of the CLIP-interacting domain, thereby named TOG4 hereafter. Interestingly, the proteins containing TOG4-binding motifs (TBMs) show the propensity to form cellular condensates. To our surprise, unlike the repulsive effect typically found when two competitive binders coexist in solution, competitive binding of these proteins to CLASP2 in the condensed phase mediates stable attachment between the CLIP170 condensate located at the MT plus ends and the ELKS1 condensate positioned near FAs. Remarkably, the phosphorylation of CLASP2 modulates the condensate interaction, leading to the detachment of the MT plus end from the ELKS1 condensate. The dynamic contact and departure of the MT plus end from the ELKS1 condensate support the directional growth of MTs along the ELKS1 condensate. Furthermore, we identified additional TBM-containing proteins and found that CLASP-mediated condensate attachment is general for the TBM-containing proteins. Collectively, our structural, biochemical, and cellular data unexpectedly unveil a mesoscale protein-protein interaction mediated by competitive binding, providing a plausible mechanism for targeted MT growth in cells.

Results

Identification of a consensus sequence for CLASP2 binding

To elucidate the molecular basis of the CLASP-mediated interaction, we mapped the regions critical for binding to the TOG4 domain of CLASP2 in both CLIP170 and LL5β, using analytical size exclusion chromatography (aSEC) and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)-based measurements. The binding region in CLIP170 was narrowed down to an N-terminal coiled coil (CLIP170_CC) (Fig. S1a–c), while the minimal TOG4-binding motif in LL5β (LL5β_TBM) was identified to contain only 19 residues within a predicted coiled coil (LL5β_CC) (Fig. S1d–f). With the mapped interacting regions, we determined the TOG4 structures of CLASP2 in complex with the identified fragments of CLIP170 and LL5β, respectively, by using crystallography (Table S1).

In these crystal structures, the TOG4 domain adopts a typical α-solenoid fold (Fig. 1b), closely resembling the structures of other TOG domains in CLASP2 (Figs. 1c and S2a). Interestingly, the C-terminal end of TOG4 forms a short, twisted 310-helix, instead of the α-helix (α−12) that is typically found in other TOG domains (Fig. S2b), which results in 11 rather than 12 α‐helices in the TOG4 domain. This atypical conformation is likely due to the presence of a proline residue in the middle of the original α−12 sequence, hindering the formation of an α-helix (Fig. S2b). Our local structural alignments further delineated the TOG domains in CLASP2 into two lobes, the N-lobe and the C-lobe (Fig. S2a, c). CLIP170_CC forms a dimeric coiled coil, interacting with the C-lobes from two TOG4 fragments (Fig. 1d). Notably, a short yet highly conserved sequence in CLIP170_CC is involved in TOG4 binding (Fig. S2d, e). This interaction is characterized by the insertion of F443 in CLIP170_CC into a pocket formed by the last two α-helices in the C-lobe (Fig. 1e). In addition, several negatively charged residues (e.g., E447) in CLIP170_CC form salt bridges with positively charged residues at the groove (Fig. 1e).

Similar to CLIP170, LL5β employs an α-helix to interact with the CLIP170-binding groove in CLASP2_TOG4 (Fig. 1f, g), although LL5β_CC does not form a dimer in solution (Fig. S2f). The similar TOG4-binding mode of CLIP170 and LL5β indicates the TOG4 domain may be used for recognizing other CLASP-binding proteins. Remarkably, a similar sequence pattern, termed TOG4-binding motif or TBM, was also found in the conserved coiled-coil regions of CENP-E and GCC185 (Fig. S2d, e). ITC-based analyses confirmed the interactions between CLASP2_TOG4 and potential TBM-containing fragments of CENP-E and GCC185 (Figs. 1j and S3a). By solving the CLASP2_TOG4 structure in complex with the CENP-E fragment (Fig. 1h, i), we validated the binding of CENP-E TBM to the TOG4 domain. Notably, although the TBM in these proteins features a consensus sequence required for TOG4 binding (Fig. 1k), less conserved residues in the TBM also contribute. For instance, the binding of CENP-E_CC to the TOG4 domain is strengthened by additional polar interactions that form between E541/D547CENP-E and S1432/K1466CLASP2 (Fig. 1i), explaining, at least partially, for the higher binding affinity of CENP-E_CC to the TOG4 domain, compared to CLIP170 and LL5β.

Crucially, all four identified TBMs exhibit a common sequence feature with two strictly conserved residues, a phenylalanine (F) and a glutamic acid (E), in the middle of their sequences (Fig. 1k). In our complex structures, these two residues adopt essentially identical conformations to tightly pack with the TOG4 domain (Fig. 1e, g, and i). The critical role of these two residues in the TOG4/TBM interaction was strongly supported by our ITC data (Figs. 1j and S3a), showing the profound disruption of the TOG4/TBM interaction by mutating these two positions. Additionally, the N-terminus of TBM features two negatively charged/polar residues that contribute to the polar interaction, while a serine/threonine or a hydrophobic residue at the C-terminus of TBM is involved in the hydrophobic interaction (Fig. 1e, g, and i). The TBM-binding groove in the TOG4 domain is highly conserved in CLASPs across different plant and animal species (Figs. 1l and S4a), suggesting a fundamental role for the TOG4/TBM interaction in the function of CLASP family members. Our structural analysis revealed that two critical residues, L1467CLASP2 and R1435CLASP2, located at the center of the TBM-binding groove (Fig. S4a), directly interact with the two key residues, F and E, in the TBMs, respectively (Figs. 1e, g, i, and S4b). Consistent with the structural finding, two disruptive mutations, L1467E and R1435E, within the groove blocked the binding of the TOG4 domain to the four TBMs (Fig. S4c).

Taken together, the above biochemical, structural, and sequence analyses demonstrate that despite having distinct overall sequences, the four CLASP-binding proteins share a characteristic TBM sequence essential for their specific interaction with CLASPs via the TOG4 domain (Fig. S3b).

The TOG4/TBM interaction is essential for CLASP2 targeting in cells

To analyze the role of the TOG4/TBM interaction in the cellular distribution of CLASP2, we overexpressed CLASP2α, the longest isoform of CLASP2, and its variants in HeLa cells. As reported previously13,24–27, CLASP2α accumulated at the MT plus end (Fig. S4d, e), and depolymerizing MTs via nocodazole treatment promoted CLASP2α targeting to the vicinity of FAs (Fig. S4f, g). However, either the TOG4 deletion mutant or the TBM-binding deficient mutations (L1467E and R1435E) resulted in a diminished enrichment of CLASP2α in these cellular locations (Fig. S4d–g). Considering the crucial role of CLIP170 and LL5β in recruiting CLASP2 to the MT plus end and the FA vicinity, respectively13,24, these observations indicate the requirement of the specific TOG4/TBM interaction in the cellular localization of CLASP2.

Given that these TBM-containing proteins share the same binding site in the TOG4 domain, these proteins may compete for the binding to CLASPs. Given the TOG4-mediated enrichment of CLASP2α in the MT plus end and several specific cellular compartments, this binding competition likely occurs between CLIP170 and the compartmentalized TBM-containing proteins in the place where the MT plus end is anchored, such as the plus end-tethered CMSCs in the vicinity of FAs24,28,29. It raises an intriguing question regarding how CLASP proteins orchestrate MT dynamics and organization in different cellular compartments amid such competing interactions.

ELKS co-phase separates with LL5β in the recruitment of CLASP2 to the FA vicinity

To explore the mechanism governing the FA vicinity localization of CLASP2 and MTs, we focused on two key components of the CMSC, LL5β, and ELKS, which associate with each other and play important roles in regulating the cortical localization of CLASPs and MTs24,30 (Fig. 2a). Notably, although ELKS does not directly interact with CLASPs, the depletion of ELKS leads to a reduction in CLASP accumulation at the cell edge24. The ELKS protein family in mammals contains two closely related members, ELKS1 and ELKS231. We identified the minimal regions in both LL5β (ELKS-binding motif or EBM) and ELKS2 (CC3), which are sufficient for mediating the ELKS/LL5β interaction (Fig. S5a–c). As the EBM sequence does not overlap with the TBM in LL5β, LL5β may simultaneously bind to CLASPs and ELKSs. Indeed, a LL5β fragment containing both binding motifs (LL5β_2BM) formed a tripartite complex with CLASP2_TOG4 and the CC3 fragment of ELKS2 (Fig. S5d).

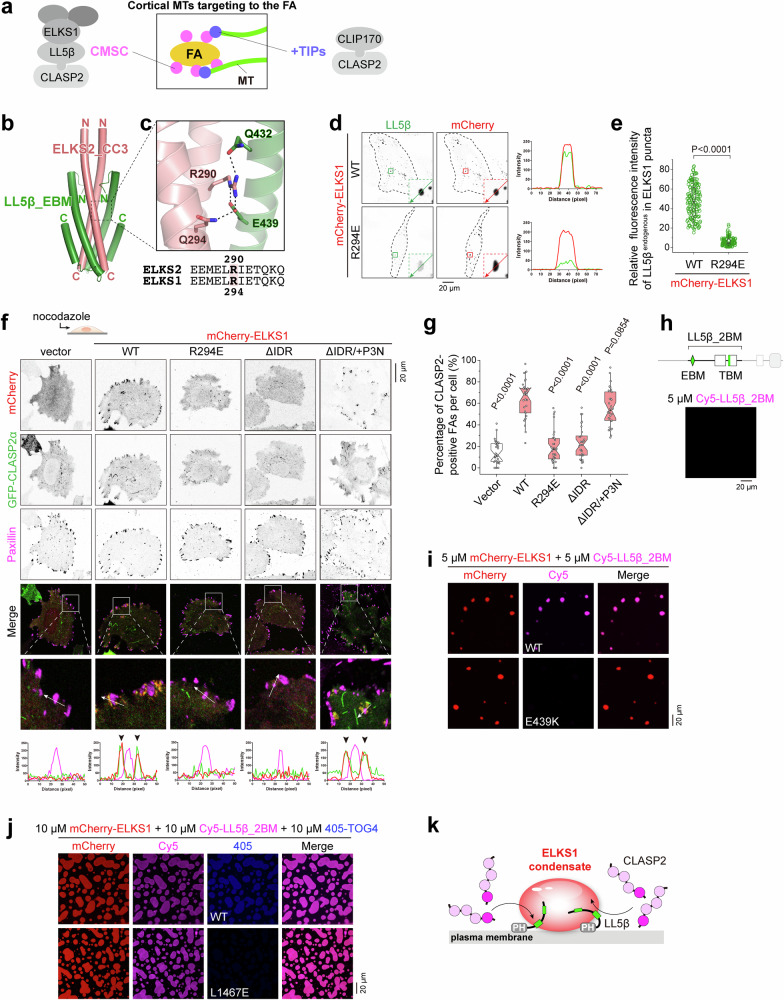

Fig. 2. The LLPS of ELKS1 facilitates CLASP2 accumulation at the FA vicinity.

a Schematic model showing the involvement of CLASP2 in two complexes at the MT plus end and FA vicinity for cortical MT targeting. b Overall structure of the ELKS2_CC3/LL5β_EBM complex. c Molecular details of the interface between ELKS2_CC3 and LL5β_EBM. R290 in ELKS2, corresponding to R294 in ELKS1, forms salt bridges and hydrogen bonds with LL5β_EBM, as indicated by dashed lines. d Cell imaging analysis showing the critical role of R294 for recruiting endogenous LL5β into the ELKS1 condensate. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-LL5β antibody. e Quantification of the relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) of endogenous LL5β in the ELKS1 condensate as indicated in (d). The RFI was normalized to background fluorescence intensity. The error bars represent the values in the 5%–95% range. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 156 condensates from 20 cells). f, Analysis of CLASP2 accumulation at the FA vicinity in nocodazole-treated cells. HeLa cells were co-transfected with GFP-tagged CLASP2α with mCherry-tagged ELKS1 or its mutants. FA was stained by anti-Paxillin antibody. The CLASP2 distribution at the FA vicinity is further indicated by arrowheads in the line analysis. g Quantification of the percentage of FAs with CLASP2α clusters at their vicinity as shown in (e). The paxillin-stained FAs (>0.3 μm2) were selected for statistics. The error bars represent the values in the 5%-95% range. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 30 cells). h Confocal imaging of Cy5-labeled LL5β_2BM in solution. The experiment was repeated three times. i In vitro co-phase separation of mCherry-ELKS1 and Cy5-labeled LL5β_2BM. The concentration of each protein was 10 μM. The experiment was repeated three times. j In vitro co-phase separation of mCherry-ELKS1, LL5β_2BM, and 405-labeled CLASP2_TOG4 or its TBM-binding deficient mutant. The concentration of each protein was 10 μM. The experiment was repeated three times. k A schematic model illustrating the cortical ELKS1/LL5β co-condensate recruiting CLASP2 via LLPS.

By determining the crystal structure of the ELKS2_CC3/LL5β_EBM complex (Table S1), we found that the dimeric ELKS2_CC3 interacts with two LL5β_EBM fragments, each consisting of an α-helical hairpin (Fig. 2b). The extensive interactions observed in the structure contribute to the stable association of LL5β with ELKSs (Fig. S5e). Among these interactions, R290ELKS2 (corresponding to R294 in ELKS1) plays a critical role by forming several salt bridges and hydrogen bonds with LL5β_EBM (Fig. 2c). Charge-reverse mutations (R290E in ELKS2 and R294E in ELKS1) abolished the binding of LL5β to the ELKS proteins in solution (Fig. S5f, g). To further determine the impact of the R294E mutation on the interaction between ELKS and LL5β in cells, we overexpressed ELKS1 to a high level in HeLa cells, which allows ELKS1 to form cytosolic puncta without being restricted to CMSC’s localization at the cell edge (Fig. 2d). Consistent with our biochemical data, while endogenous LL5β was highly enriched in the ELKS1 puncta, this enrichment was dramatically decreased in ELKS1R294E puncta (Fig. 2d, e).

In line with the previous finding that ELKS1 promotes the clustering of CLASP2 at the cell cortex24, the overexpression of ELKS1 significantly enhanced the accumulation of CLASP2α around FAs in nocodazole-treated cells (Fig. 2f). However, the ELKS1R294E mutant failed to enrich CLASP2α in the vicinity of FAs (Fig. 2f, g), indicating that the cortical accumulation of CLASP2 depends on the formation of the LL5β/ELKS1 complex. Interestingly, the removal of the N-terminal intrinsically disorder region (IDR) from ELKS1 resulted in the diffused distribution of ELKS1 and a reduction in the accumulation of CLASP2α around FAs (Fig. 2f, g). It is noteworthy that ELKS proteins undergo IDR-dependent liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and form co-condensates with interacting proteins32–35. Hence, we speculated that ELKS1 may accumulate LL5β and CLASP2 via LLPS.

Indeed, LL5β_2BM alone did not form condensates but co-phase separated with the purified full-length protein of ELKS1 in solution (Fig. 2h, i). Conversely, with the addition of LL5β_2BM, ELKS1 could form droplets at concentrations as low as 0.5 μM (Fig. S6a), a level comparable with the cellular concentration of ELKS proteins36. In contrast, the E439K mutation in LL5β and the L1467E mutation in CLASP2, which disrupt the LL5β/ELKS (Fig. 2c) and CLASP2/LL5β (Fig. 1g) interactions, respectively, blocked the accumulation of LL5β_2BM and CLASP2_TOG4 in the ELKS1 condensate (Fig. 2i, j). In line with the observed condensate formation in solution, the endogenous protein phenocopies the condensation of the overexpressed ELKS1 in HeLa cells, which is IDR-dependent (Fig. S6b). ELKS1, but not its R294E mutant, is capable of accumulating CLASP2α in cellular condensates (Fig. S6c, d). These results collectively suggest that LL5β accumulates in the ELKS1 condensate by binding to ELKS1 and consequently recruits CLASP2 into condensates.

To verify this scenario in cells, we designed a chimeric protein by replacing the IDR of ELKS1 with the N-terminal domain of Par3 (P3N), which has a distinct sequence from ELKS1_IDR and is known to form cellular condensates through LLPS37. Interestingly, the ΔIDR/ + P3N chimaera regained the ability to form condensates that specifically recruit LL5β (Fig. S6b and e). Importantly, this chimeric protein also restored the accumulation of CLASP2α in the FA vicinity (Fig. 2f, g). Thus, the LLPS propensity of ELKS1 may drive condensate formation beneath the plasma membrane, in coordination with LL5β, which can bind to the phospholipid through its PH domain24 and recruit CLASP2 via the TOG4/TBM interaction (Fig. 2k).

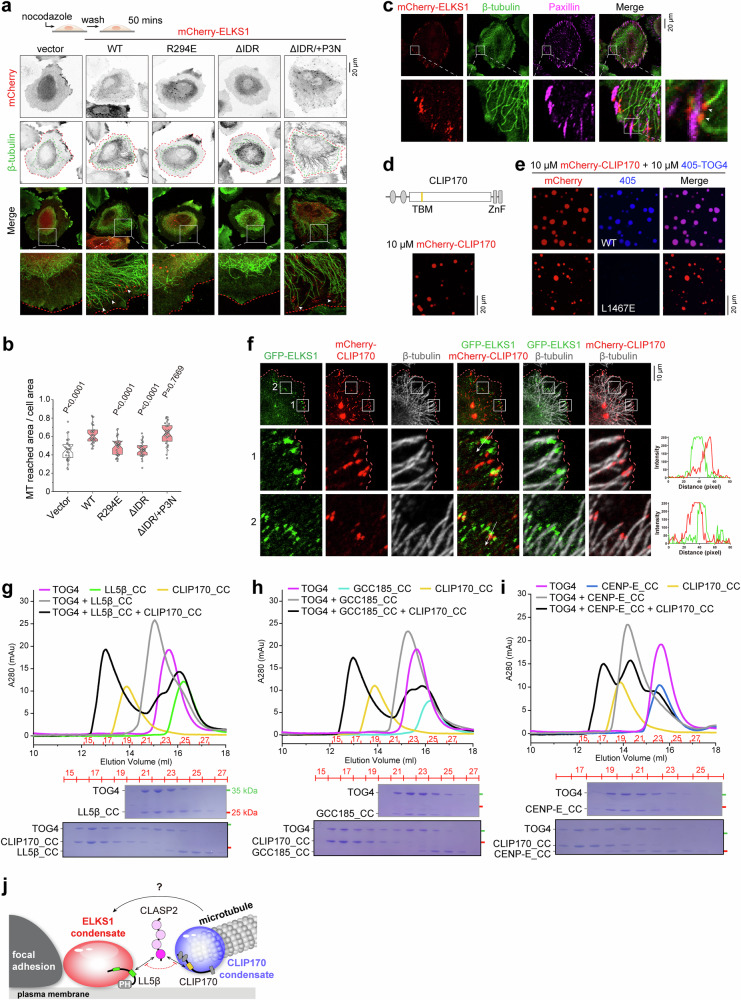

CLASP2 accumulation in ELKS1 and CLIP170 condensates is required for cortical MT targeting

Given the critical role of CLASPs in stabilizing MTs, ELKS1 may regulate cortical MT organization by recruiting CLASP proteins. To explore this possibility, we analyzed the distribution of MTs in nocodazole-treated cells overexpressing ELKS1 or its variants. After nocodazole washout, MTs at the ventral region of cells overexpressing wild-type ELKS1 massively reached the cell edge, in stark contrast to the perinuclear accumulation of MTs in control cells (Fig. 3a, b). Consistent with the impaired ability to accumulate CLASP2, neither the LL5β binding-deficient mutant (R294E) nor LLPS-deficient mutant (ΔIDR) of ELKS1 guides MT growth towards the cell edge, whereas the ΔIDR/ + P3N chimaera showed a promotion on cortical MT growth like wild-type ELKS1 (Fig. 3a, b). Given that CLASP2 is assembled with ELKS1 and LL5β to form CMSCs around FAs28 (Figs. 2a and S7a), we speculated that the ELKS1 condensate facilitates MT attachment to FAs. Supporting this hypothesis, the ELKS1 condensates in the FA vicinity contact the MT plus end (Fig. 3c). Together, these results suggest that the ELKS1 condensate plays a crucial role in targeting MTs to the cell cortex by creating a CLASP2-enriched environment that stabilizes the attached MT plus end.

Fig. 3. The LLPSs of ELKS1 and CLIP170 facilitate MT targeting.

a Cell imaging of cortical MT targeting in nocodazole-treated cells. HeLa cells were transfected with mCherry, mCherry-tagged ELKS1, or its mutants. After being treated with 10 μM nocodazole for 2 h, transfected cells were washed three times and cultured in the fresh medium for 50 min, allowing MTs to regrow. This approach enables the assessment of ELKS1’s influence on MT growth. MTs were stained by anti-β-tubulin antibody. Cell edges and MT reaching boundaries are indicated by red and green dashed lines. ELKS1 puncta at MT tips are indicated by arrowheads in zoom-in views. b Quantification of the proportion of MT reaching area to the total cell area as shown in (j). The error bars represent the values in the 5%–95% range. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 30 cells). c Cell imaging of ELKS1 condensates at the FA vicinity. Transfected cells were treated using the same procedure as in (a). FAs were stained by anti-paxillin antibody, and MTs were stained by anti-β-tubulin antibody. Similar observations were found in ~20 cells in this experiment. d Confocal imaging of mCherry-tagged CLIP170 in solution. The experiment was repeated three times. e In vitro co-phase separation of mCherry-CLIP170 and 405-labeled TOG4 or its TBM-binding deficient mutant. The concentration of each protein was 10 μM. f Cell imaging showing the spatial relationship between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 condensates at the cell cortex. The non-overlapping positions of the two types of condensates were indicated by line analysis. A similar phenomenon was observed in two independent experiments. g–i TBM-containing proteins compete for the binding to the TOG4 domain of CLASP2. aSEC-based analysis showed that CLIP170 competes with LL5β (g), GCC185 (h), and CENP-E (i) for CLASP2_TOG4 binding in solution. The concentration of CLIP170_CC, LL5β_CC, CENP-E_CC, GCC185_CC, and CLASP2_TOG4 in the aSEC experiment was 40 μM. j A schematic model illustrating the multiphase system in MT targeting, involving the ELKS1 and CLIP170 condensates.

In addition to its enrichment in the ELKS1 condensate, CLASP2 also accumulates at the MT plus end in a TOG4-dependent manner (Figs. 2a and S4d). Disrupting the TOG4/TBM interaction eliminated the enrichment of CLASP2 in the CLIP170 puncta at the MT plus end (Fig. S7b). Interestingly, CLIP170 also forms condensates coating the MT ends in HeLa cells38 (Fig. S7c) and undergoes phase separation39 (Fig. 3d), which are capable of accumulating CLASP2 through the TOG4/TBM interaction (Fig. 3e). Intriguingly, the CLIP170 condensate at the MT plus end contact the cortical ELKS1 condensate (Figs. 3f and S7e), suggesting a role of the CLIP170 condensate in targeting MTs to the cell cortex. Consistently, deleting the C-terminal zinc finger (ZnF) domain from CLIP170 disrupts its ability for condensate formation (Fig. S7d) and cortical MT organization (Fig. S7f, g).

However, given the competition between the TBMs for binding to CLASP2 (Fig. 3g–i), it remains puzzling how the MT plus-end enriched with CLIP170 can tether to the ELKS1 condensate enriched with LL5β and how CLASP2-mediated interactions function in this tethering (Fig. 3j).

Competitive binding to accumulated CLASP2 mediates the stable contact between condensates

To explore these questions, we analyzed the LLPS of ELKS1 and CLIP170 in cells co-transfected with these proteins. The two proteins formed droplets separately in the cytosol, occasionally touching each other in an immiscible manner (Figs. 4a and S8a and Movie S1). Strikingly, upon the additional overexpression of LL5β and CLASP2α in this multiphase system, a significant proportion of ELKS1 droplets became trapped onto the surface of CLIP170 droplets (Figs. 4a and S8a and Movie S1), with the average contact duration extended from ~2 min to >12 min (Fig. 4b). Remarkably, in about half measurements, the two types of droplets remained in contact throughout the 20-min observation (Fig. 4b), indicating that the presence of CLASP2 dramatically prolongs droplet adhesion. Interestingly, this stable contact could still occur in a significant proportion of droplets in the absence of LL5β overexpression (Figs. 4a–d and S8a and Movie S1), presumably due to the presence of endogenous LL5β in the ELKS1 condensate (Fig. 2d). This unexpected finding suggests a role of the interaction between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 condensates in the regulation of MT tethering to the vicinity of FAs.

Fig. 4. CLASP2 mediates the attachment between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 condensates.

a Kymographic analysis of attachment between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 condensates in live cells. Kymographs were generated using NIS-Elements A1R Analysis software. The magenta lines indicate the contact duration between the two types of droplets. The upper limit of recording time was set to 20 min. Two snapshots indicated by arrowheads in each kymography are shown aside. See also Movie S1. b Quantification of the contact duration between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 droplets as indicated in (a). Data are mean ± s.d. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 40 droplet contacts from 10 movies). c, d Quantification analysis of contact ratios between CLIP170 and ELKS1 droplets as indicated in Fig. S8a. Data are mean ± s.d. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 10 cells).

In agreement with the CLASP2-dependent condensate interaction, in cells transfected with LL5β but not CLASP2α, the prolonged contact duration was diminished, and the proportion of droplets that made contact also decreased (Figs. 4a–d, and S8a and Movie S1). Similarly, either depleting CLASP2α from the droplets by introducing the TBM-binding deficient mutation (L1467E) in CLASP2α or removing LL5β from the ELKS1 droplet by introducing the LL5β-binding deficient mutation (R294E) in ELKS1 abolished the prolonged droplet adhesion and reduced the droplet contact ratio (Figs. 4a–d, and S8a and Movie S1). Consistent with our live imaging analysis, the 3D reconstruction of cytosolic droplets further confirmed the requirement of CLASP2α in the droplet attachment (Fig. S8b and Movie S5). These results demonstrate that CLASP2 is essential for the stable attachment between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 condensates.

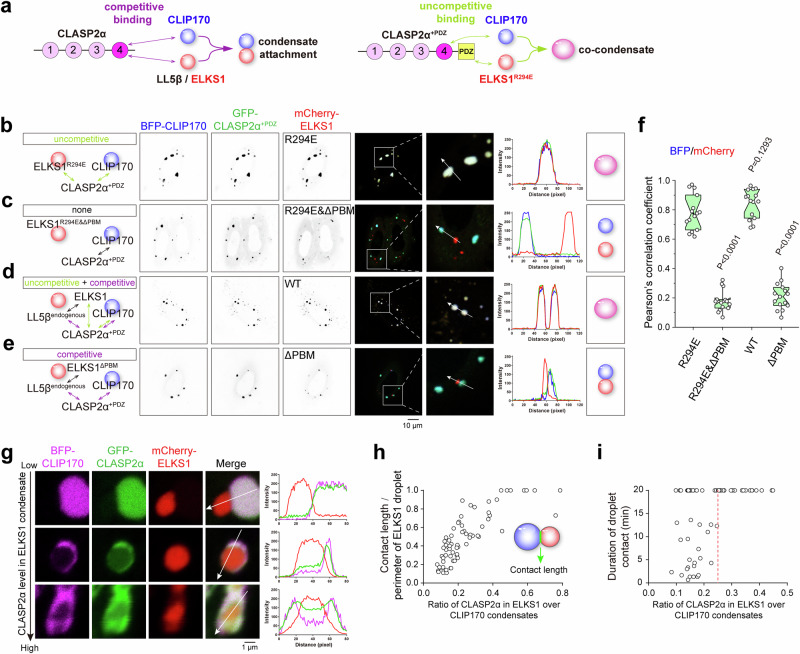

Since LL5β and CLIP170 compete for binding to CLASP2, we asked whether competitive binding contributes to the CLASP2-mediated condensate interaction. Thus, we designed the CLASP2α+PDZ chimaera by fusing the PDZ domain of RIM1 to the C-terminus of CLASP2α (Fig. 5a). As the RIM1 PDZ domain can interact with the PDZ binding motif (PBM) at the C-terminus of ELKS140, CLASP2α+PDZ acquires the ability to directly bind to ELKS1 (Fig. S9a, b). Upon overexpressing CLASP2α+PDZ and ELKS1R294E, competitive binding was replaced with uncompetitive binding in the multiphase system (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, CLIP170 and ELKS1 co-phase separated in this system (Fig. 5b), likely because the binding of CLASP2α+PDZ to CLIP170 and ELKS1R294E are compatible, allowing mixed distribution of CLIP170 and ELKS1 in the condensed phase. As a control, deleting the PBM from ELKS1R294E blocked the accumulation of CLASP2α+PDZ in the ELKS1 condensate (Fig. S9a), resulting in separated condensates of CLIP170 and ELKS1 (Fig. 5c). Although competitive binding occurs, the wild-type ELKS1 protein also co-condensed with CLIP170 in the presence of CLASP2α+PDZ (Fig. 5d), indicating that the uncompetitive binding of CLASP2α+PDZ to ELKS1 surpasses the competitive binding for the co-condensate formation. As expected, ELKS1ΔPBM, which lacks uncompetitive binding while remains competitive binding to CLASP2α+PDZ, reestablished the condensate attachment (Figs. 5e, S9a, and S9b). These observations were further confirmed by statistical analyses of the co-condensation in the designed conditions (Fig. 5f). Therefore, we concluded that the condensate attachment relies on the competitive binding of LL5β and CLIP170 to CLASP2, which likely mediates mesoscale protein-protein interactions between the attached droplets (Fig. S9c).

Fig. 5. Competitive binding to CLASP2 in the condensed phase mediates condensate attachment.

a Schematic models of condensate interactions mediated by CLASP2α. Competitive binding to CLASP2α leads to condensate attachment, while introducing uncompetitive binding to CLASP2α+PDZ results in co-condensate formation. b–e Cellular analysis of the effect of competitive binding on condensate interactions. The designed interactions and outcomes are illustrated in the corresponding left and right diagrams, respectively. f Pearson’s correlation coefficient of BFP and mCherry signals as shown in (b–e). The error bars represent the values in the 5%-95% range. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 15 cells). g Droplet contact analysis of the ELKS1 condensate with varying CLASP2 levels. To alter the CLASP2 level in the ELKS1 condensate, the plasmid ratios of CLIP170, CLASP2α, and ELKS1 transfected into cells were set as 1:1:1, 1:2:1, and 1:3:1. h Scatterplot of the contact levels of CLIP170 droplets on ELKS1 droplets with different CLASP2 levels. The corresponding contact levels at different CLASP2 levels in the ELKS1 condensate were calculated from a total of 68 droplet contacts. i Scatterplot of the contact duration between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 droplets with different CLASP2 levels in the ELKS1 condensate. A total of 65 droplet contacts from 20 movies were recorded. See also Fig. S9i, j for examples.

As shown by live imaging analysis, many CLASP2α clusters intermittently moved towards the growing leading edge (Movie S2). This dynamic accumulation of CLASP2α results in the predominant distribution of CLASP2α clusters near the cell edge (Fig. S9d–g). These observations suggest that CLASP2 may delocalize from the ELKS1 condensate and move with the CLIP170 condensate at the MT plus end. However, cellular localization analysis of CLASP2α+PDZ showed a different pattern. It forms co-puncta with ELKS1 and CLIP170 (Fig. S9d), and more than half of CLASP2α+PDZ puncta were located away from the cell edge (Fig. S9e). It is likely that the co-condensate formation prevents the detachment of the CLIP170 condensate from the ELKS1 condensate, thereby inhibiting the redistribution of CLASP2α from the co-condensate. Thus, the competitive rather than uncompetitive binding allows condensate attachment and detachment, regulating the dynamic distribution of CLASP2 in cortical MT organization.

Intriguingly, although LL5β and CLIP170 have comparable binding affinities to CLASP2 (Fig. 1j), the accumulation level of CLASP2α in the ELKS1 droplet is significantly lower than that in the CLIP170 droplet (Fig. 5g). This difference may be attributed to the indirect recruitment of CLASP2α to the ELKS1 condensate, and the preferential binding of TOG4 to CLIP170 over LL5β (Fig. 3g). Surprisingly, the accumulation ratio of CLASP2α in the two condensates spatiotemporally determines the condensate interaction mode. With increasing CLASP2α levels in the ELKS1 droplet, the CLIP170 droplet tended to engulf the ELKS1 droplet, covering a larger surface area (Fig. 5g, h). Moreover, quantitative analysis revealed that elevating CLASP2α levels in the ELKS1 droplet to >25% of that in the CLIP170 droplet efficiently extends the droplet contact duration (Figs. 5i and S9h–j), presumably due to the larger contact area between droplets. Thus, the strength of the condensate attachment is regulated by the accumulation level of CLASP2 in the two condensates, indicating a control mechanism for condensate interaction via the modulation of CLASP2 levels in these condensates.

Phosphorylation of CLASP2 controls the detachment of the MT plus end from the ELKS1 condensate for the directional growth of MTs

The cellular distribution of the ELKS1 condensate is not restricted to the cell periphery. Many ELKS1 condensates were found to be formed away from both FAs and the cell edge (Fig. S10a, b). While a large portion of the ELKS1 condensates disappeared as the leading edge of the cell expanded, some ELKS1 condensates persisted and thereby could be observed away from the cell edge (highlighted by white circles in Movie S2). Intriguingly, the path of MTs often overlapped with several ELKS1 condensates in a row (Fig. 6a). Superresolution microscopic analysis confirmed the spatial proximity of MTs at the ventral region to the ELKS1 condensates (Fig. S10c). Importantly, through monitoring the growing MT plus end, indicated by CLIP170 signals, we found that cortical MTs passed through multiple ELKS1 condensates behind the leading edge and showed transient contact with these condensates (Fig. 6b and Movie S3). It suggests that the ELKS1 condensates distal to the cell edge may play a role in navigating MT growth towards the cell edge.

Fig. 6. The ELKS1 condensate guides the growth of cortical MTs through CLASP2.

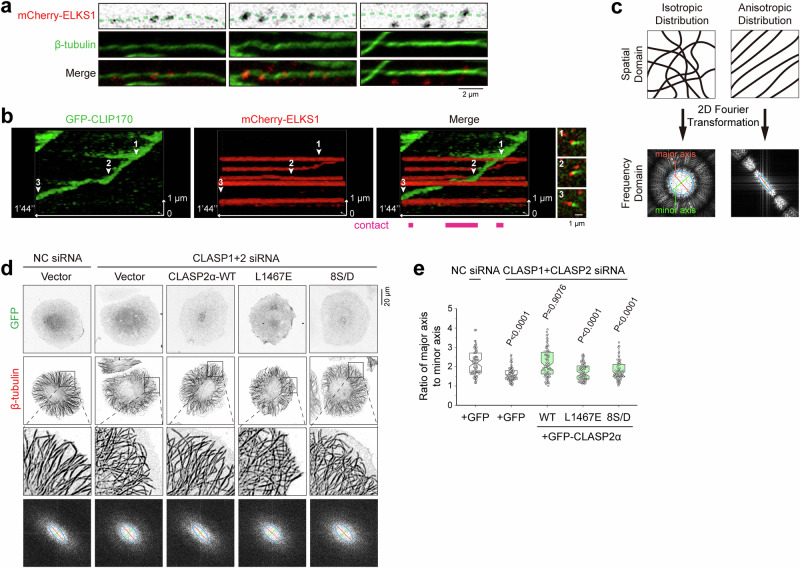

a Distribution of ELKS1 condensates along MTs. Cellular regions with less dense MTs were chosen for imaging. Similar phenomena were observed in more than three experiments. b Kymographic analysis showing the MT plus end with the CLIP170 condensate passing through multiple ELKS1 condensates in live cells. Three snapshots indicated by arrowheads in the kymography are shown aside. See also Movie S3. c Schematic diagrams illustrating the quantitative evaluation of MT distribution patterns by applying 2D Fourier transformation. d Cellular analysis of cortical MT organization regulated by CLASP2. Cells were fixed with methanol at −20 °C. 2D Fourier transform was applied to MT patterns of different samples, and corresponding results were shown at the bottom. e Quantification of the ratio of the major axis to the minor axis for the ellipses in the frequency domain as shown in the bottom panels in (d). Four regions near the cell edge in each cell were selected as the ROIs. The error bars represent the values in the 5%–95% range. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 80 ROIs from 20 cells).

To verify the role of ELKS1 in directing cortical MT organization, we prepared cells with ELKS1 knockdown (Fig. S11a). To quantitatively assess the organization of cortical MTs, a two-dimensional Fourier transform was applied to the pattern of MT distribution at the cell periphery (Fig. 6c). Unlike the typical radial organization of MTs at the cell periphery with an anisotropic distribution, depletion of ELKS1 led to disorganized cortical MTs with a tendency towards isotropic distribution (Fig. S11b, c). Resembling the effect of ELKS1 knockdown, disorganized cortical MTs were also observed in cells with LL5β knockdown (Fig. S11a–c), further supporting the function of ELKS1 and LL5β in accumulating CLASP2 and organizing MT growth at the cell cortex. Consistently, knocking down both CLASP1 and CLASP2 resulted in impaired cortical MT organization27 (Figs. 6d, e, and S11d). Together, these results indicate that the ELKS1 condensates contribute to directional MT growth by orchestrating the CMSC components, including LL5β and CLASP2.

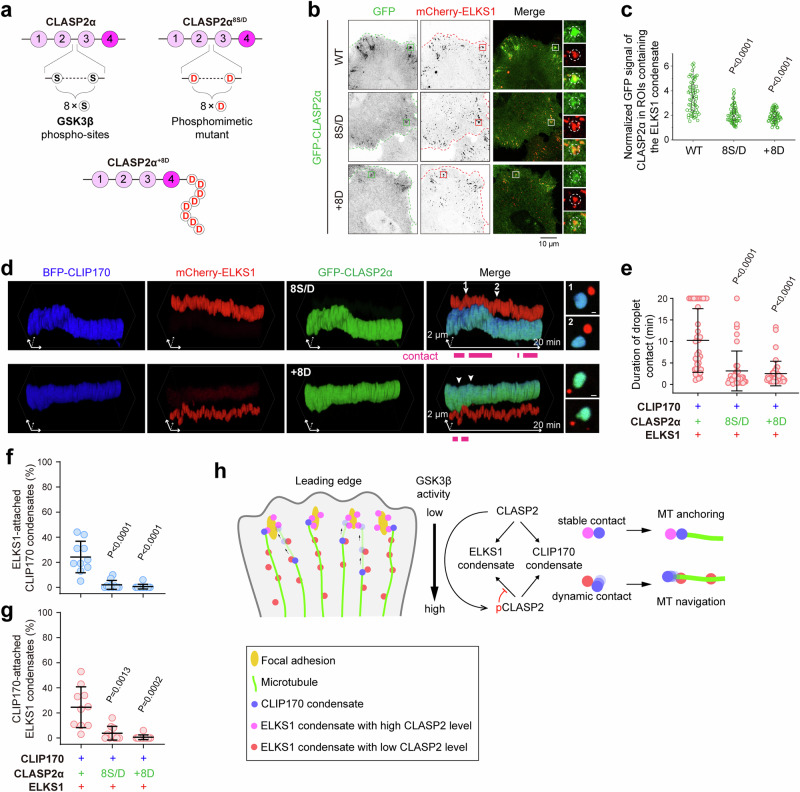

When the MT plus end attaches to an ELKS1 condensate, how does it detach rapidly from the condensate to continue the MT growth? As a high level of CLASP2 is required for the stable contact between the CLIP170 and ELKS1 condensates (Fig. 5g), the detachment may be achieved by lowering the CLASP2 level in the ELKS1 condensate. CLASPs have been reported to be phosphorylated by GSK3β29,41, and overexpression of either GSK3β or a phosphomimetic mutant of CLASP2 (8 S/D), which replaces eight serine phosphorylation sites with aspartic acids, led to directionless MT growth (Fig. 7a)29. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the phosphorylation of CLASP2 by GSK3β may inhibit its accumulation in the ELKS1 condensate, considering the importance of electrostatic interactions in regulating protein recruitment to condensates42,43.

Fig. 7. Phosphorylation of CLASP2 regulates condensate attachment for cortical MT organization.

a Schematic diagrams illustrating the phosphomimetic mutation (8 S/D) in CLASP2α. b Cell imaging of the accumulation of CLASP2α in the ELKS1 condensate in cells. The ROIs containing the cortical ELKS1 condensate are indicated by dashed circles. c Quantification of the GFP signal of CLASP2α in the ROI as shown in (b). Three ROIs containing the cortical ELKS1 condensate were randomly selected for each cell. The GFP signal was normalized to background fluorescence intensity. The error bars represent the values in the 5%–95% range. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 20 cells). d Kymographic analysis of the weakened attachment between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 condensates in cells overexpressing CLASP2α mutants. See also movie S4. e Quantification of the contact duration between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 droplets as indicated in (d). Data are mean ± s.d. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 40 droplet contacts from 10 movies). f, g Quantification analysis of contact ratios between CLIP170 and ELKS1 droplets as indicated in Fig. S12g. Data are mean ± s.d. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 10 cells). h A schematic model illustrating cortical MT organization mediated by CLASP2. The different levels of CLASP2 in the condensed phase, which are regulated by GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation, determine the two different modes of condensate attachment for MT anchoring and navigation.

In line with this hypothesis, the accumulation level of the CLASP2α 8 S/D mutant in the ELKS1 condensate was significantly decreased in either low or high expression levels (Figs. 7b, c, S12a, and S12b). Furthermore, the direct addition of eight aspartic acids (+8D) to the C-terminus of CLASP2α attenuated its accumulation in the ELKS1 condensate (Figs. 7b, c, S12a, and S12b), confirming the charge-mediated prevention of CLASP2 entry into the condensed phase of ELKS1. Remarkably, CLASP28S/D still accumulated in the CLIP170 condensate in the cytosol or MT ends, with a level comparable to that of the wild-type protein (Fig. S12c–e). This indicates that the phosphorylation-dependent inhibition of CLASP2 accumulation in the condensed phase is selective. Consistent with the decreased CLASP2α level of the 8S/D and +8D mutants in the ELKS1 condensate, the droplet attachment between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 condensates became significantly less stable (Figs. 7d–g and S12g). Thus, GSK3β-phosphorylation of CLASP2 likely modulates the condensate attachment. Importantly, the CLASP2α8S/D mutant failed to restore cortical MT organization in CLASP1/2 double-knockdown cells, phenocopying the TBM-binding deficient mutant CLASP2αL1467E (Fig. 6d, e). These results indicate that the regular arrangement of cortical MTs requires tunable CLASP2 levels in the ELKS1 condensates.

Consistent with the previous observation that the GSK3β activity is inhibited in the cell edge29,44, the ELKS1 condensates in the cell periphery accumulate more CLASP2 than those in the cell interior (Fig. S12f). Therefore, in the region distal to the cell edge, the GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation of CLASP2 enables dynamic contact between the ELKS1 and CLIP170 condensates for MT navigation by specifically decreasing CLASP2 levels in the ELKS1 condensate (Fig. 7h). On the other hand, in the FA vicinity proximal to the cell edge, high CLASP2 levels in the ELKS1 condensate may promote stable contact between the two condensates for MT anchoring (Fig. 7h).

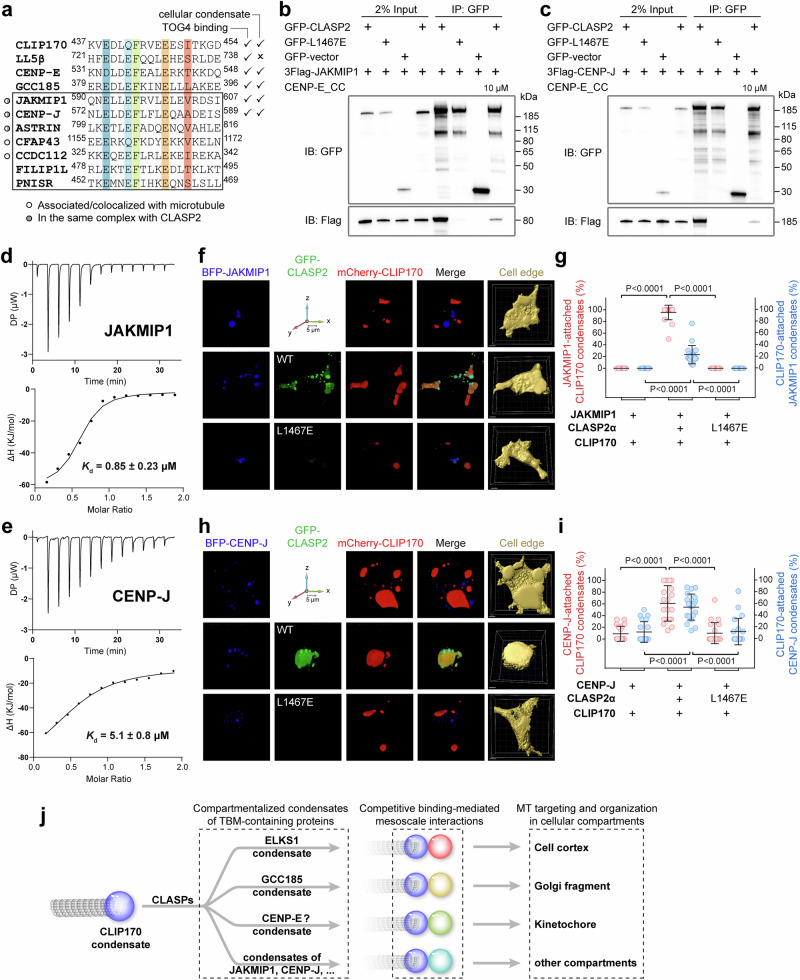

The CLASP-mediated condensate attachment is a general paradigm for TBM-containing proteins

As MTs are recruited to various cytoplasmic compartments, it is appealing to explore additional proteins involved in the cellular targeting of CLASPs via the TOG4-mediated interaction. To identify potential TBM-containing proteins in the human genome, we employed the consensus sequence pattern for TBMs (Fig. 1k), taking into account additional criteria such as intracellular localization and the helical conformation of TBMs. After careful selection, we identified seven candidate proteins (Fig. 8a), most of which have been reported to associate with MTs45–49.

Fig. 8. CLASP2 mediates condensate attachment in other TBM-containing proteins.

a Sequence alignment of TBM-containing proteins in the human genome. To identify more TBM-containing proteins in silico, a motif search was performed on the Scansite website (https://scansite4.mit.edu/) with the consensus sequence pattern of TBM (Fig. 1k). The helical conformation of the potential TBMs in candidate proteins was checked using AlphaFold2-based predictions (https://www.alphafold.ebi.ac.uk). The identified TBM-containing proteins in this study are boxed. b, c Co-immunoprecipitation assays showing the TOG4-mediated interaction between CLASP2α and JAKMIP1 (b) or CENP-J (c). The experiment was repeated twice. d, e ITC-based analyses of the interaction between CLASP2_TOG4 and TBM-containing fragments in JAKMIP1 (d) or CENP-J (e). The boundaries used are residues 549–627 for JAKMIP1 and 571 – 589 for CENP-J. f–i Three-dimensional reconstruction (f, h) and quantification analysis (g, i) of attachment between the CLIP170 and JAKMIP1 (f, g) or BFP-CENP-J (h, i) condensates. Competitive binding to CLASP2 is required for the condensate interactions, as the L1467E mutation in CLASP2α abolished condensate attachment. Images were captured every 0.2 μm on the Z-axis, and the number of images depended on the distribution of condensates along the Z-axis. The 3D pictures for each cell were generated using NIS-Elements A1R Analysis software. The cell boundaries were generated using Imaris software. Data are mean ± s.d. The middle, bottom, and top of boxplots represent, respectively, the median, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile (n = 20 cells). j A schematic model illustrating TBM-containing proteins in MT organization in various cellular compartments. CLASP2 promotes condensate attachment by mediating mesoscale protein-protein interactions in the condensed phase.

Among these proteins, Janus kinase and MT interacting protein 1 (JAKMIP1) and CENP-J were selected for further validation, as previous studies had suggested them as being part of complexes with CLASPs23,50. Co-immunoprecipitation assay demonstrated that CLASP2, but not its L1467E mutant, binds to both JAKMIP1 and CENP-J (Fig. 8b, c). Notably, the addition of CENP-E_CC in the assay reduced the binding of CLASP2 to JAKMIP1 and CENP-J (Fig. 8b, c). Furthermore, ITC-based analyses confirmed that the TBM fragments of JAKMIP1 and CENP-J interact with CLASP2_TOG4 (Fig. 8d, e). Thus, we concluded that both JAKMIP1 and CENP-J directly bind to CLASP2 through the specific TOG4/TBM interaction. Our findings are consistent with a recent study that also identified CENP-J as a potential binding partner for the TOG4 domain in CLASP120.

Interestingly, both JAKMIP1 and CENP-J form protein condensates in transfected cells (Fig. S13a), suggesting the potential for CLASP2-mediated mesoscale association between the CLIP170 condensate and these condensates. Indeed, by co-expressing either JAKMIP1 or CENP-J with CLIP170 and CLASP2α in cells, we observed the stable attachment of the CLIP170 condensate to the JAKMIP1 and CENP-J condensates in a CLASP2-dependent manner, relying on the TOG4-mediated interaction (Fig. 8f-i). Given that these TBM-containing proteins form cellular condensates (Fig. S13a), it is likely that such condensate attachments mediated by CLASP2_TOG4 represent a common feature for TBM-containing proteins to regulate MT organization in various cellular compartments. Notably, the 8 S/D mutation of CLASP2 had minimal impact on the adhesive contact between these condensates (Fig. S13b–d), as CLASP8S/D remained highly enriched in the JAKMIP1 and CENP-J condensates (Fig. S13e–h). This finding indicates that the JAKMIP1 and CENP-J condensates are insensitive to phosphorylated CLASP2, and GSK3β may not be a critical regulator of the mesoscale association between CLIP170 and JAKMIP1 or CENP-J via CLASP2.

Remarkably, our sequence analysis of the CLASP family proteins across a spectrum of organisms, ranging from yeast to human, showed that the TBM-binding site in the TOG4 domain is conserved in plants and animals (Fig. S14). In addition to the TOG4 domain, the SxIP motifs have been found to promote the localization of CLASPs at the MT plus-end by binding to EBs and facilitate cortical MT organization27,29,51 (Fig. 1a). However, the SxIP motifs appear in vertebrates but are absent in most invertebrates. This observation suggests a fundamental role for the TOG4/TBM interaction in organizing MTs (Fig. 8j), which remains to be explored in different cellular compartments and different organisms (e.g., dynamic MT network in growth cone52,53 and cortical MT organization in plants54,55).

Discussion

By employing an integrative approach involving structural, biochemical, and cellular techniques, our study here revealed a multiphase system governing the regular organization of MTs at the cell cortex. This intricate system relies on CLASP2, which serves as a molecular glue, mediating the interactions between the CLIP170 and ELKS1 condensates through two different modes: the transient interaction navigating MT growth towards the cell edge and the stable association anchoring MTs to FAs (Fig. 7h). Given the highly dynamic nature of MT growth, the protein assemblies in this system demands rapid regulation, which is efficiently achieved through LLPS. Importantly, our findings highlight the significance of competitive binding in drives protein-protein interactions at the mesoscale level, offering a plausible mechanism to dynamically manage the intricate interplay of different protein condensates in cells.

Biomolecular condensates have been widely characterized in diverse cellular processes56–58. Emerging evidence has suggested the co-existence of multiple condensates in certain cellular milieu59–62, yet the condensate organization in a multiphase system has remained largely a mystery. Our study unveiled the dynamic interaction between immiscible condensates in the multiphase system mediated by competitive binding. In the dilute phase, proteins are excluded from binding sites by competing molecules and then quickly diffuse away. However, in the condensed phase, the concentrated environment limits protein diffusion63, allowing previously disassociated molecules to reassociate. Crucially, unlike the single TBM-binding site in a CLASP2 molecule, the condensed CLASP2 assembly can provide multiple TBM-binding sites for interacting with different TBM-containing proteins simultaneously (Fig. S9c). Consequently, rather than exclusive interactions in the dilute phase, competitive binding likely mediates condensate-condensate interactions through mesoscale protein-protein interactions at the contact interface between condensates. On the other hand, competitive binding prevents the mixing of two closely attached condensates, as competing molecules in these two condensates are mutually excluded. The substitution of competitive binding with uncompetitive binding leads to co-condensate formation (Fig. 5b), which mixes all interacting proteins and thereby limits the dynamic distribution of proteins. Thus, competitive binding favors the reversible association and dissociation of the MT plus end with the ELKS1 condensate. Considering the prevalence of binding competitions, our discovery provides a potential organization mode for multiphase systems in cellular processes, which require dynamic associations between immiscible condensates. Interestingly, in addition to CLIP170, EB1 was reported to undergo LLPS as well64, suggesting a multiphase organization at the MT plus end. As EB1 has similar affinities for binding to the SxIP motifs of CLASPs and CLIP17065, it raises the intriguing possibility that the SxIP-mediated competitive binding of CLASPs and CLIP170 to EB1 plays a role in organizing these protein condensates at the MT plus ends.

An important feature of the CLASP2-mediated condensate interaction is its tunability, which allows for precise control of directional MT growth (Fig. 7h). This tunability is achieved through the GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation of CLASP2. When MTs are growing towards the leading edge, active GSK3β phosphorylates CLASP2 and consequently reduces the CLASP2 level in the ELKS1 condensate, which shortens the duration of the condensate contact and allows MTs to continue growing. Notably, GSK3β can substantially inhibit the accumulation of CLASP2 at the MT plus-end, partly by the disrupted binding of phospho-CLASP2 to EBs13,26,29,41, which may also contribute to the shortened contact duration. Once MTs reach the leading edge, decreased GSK3β activity promotes the accumulation of CLASP2 in the ELKS1 condensate, leading to a stable anchoring of the MT plus-ends to cortical FAs. The dynamic concentration changes in the condensed phase indicate the role of CLASP2 as a “client” in the multiphase system. The “client” role of CLASP2 allows cells to regulate the CLASP2 level rapidly and selectively in the condensates without affecting condensate formation. As CLASPs are recruited to various cellular compartments by different TBM-containing proteins, the CLASP-mediated condensate interaction likely plays a role in MT organization in cellular compartments other than the cell cortex, such as the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 8j), regarding the LLPS propensity of GCC18566.

While FAs are critical players in MT guidance67,68, the underlying mechanisms have remained poorly understood. CMSC proteins are known to regulate the interplay between MTs and FAs. As the core component of the CMSC, ELKS1 forms condensates with LL5β beneath the plasma membrane, generating a widespread network at the cell cortex (Figs. 2d, S6b). These condensates act as hotspots that dynamically associate with the MT plus end for MT guidance. During cell migration, with the leading edge advances, while most ELKS1 condensates disassembled, a subset persists (Movie S2). As these residual ELKS1 condensates mark the former edge, they likely serve as guidance cues, directing MTs to grow in alignment with the migrating leading edge. In addition, ELKS proteins are known to participate in vesicle docking and release at both the cell cortex and presynaptic terminals24,69. Given the proximity of the ELKS1 condensate to MTs and the plasma membrane, these condensates may also serve as effective platforms for capturing and releasing vesicles transported by kinesin motors32. Nevertheless, as the ELKS1 condensate is tethered to the plasma membrane through the association of LL5β with phospholipids24, the effect of ELKS1 on MT organization is likely confined to MTs close to the plasma membrane. MTs located away from the plasma membrane, particularly those in the cell interior, may be organized by other mechanisms. One such alternative mechanism involves actin filaments, which have been indicated in guiding MT growth through actin-MT crosstalk70. How the different mechanisms coordinate MT growth requires further investigations to provide a comprehensive understanding of MT organization in cells.

Noteworthy, the observations of cellular condensates and their interplay in our study were performed under conditions of target protein overexpression. We acknowledge that condensates generated through this approach may not fully represent the properties of those formed under endogenous protein levels, despite sharing similar morphological features (Fig. S6b). Therefore, future research on cellular condensates at physiological expression levels is required to confirm the biological significance of our findings and to deepen our understanding of the intricate interplay among these cellular condensates.

Methods

Plasmids

For cellular assays, the genes of human CLASP2 (GeneBank, NM_001365634.1), rat ELKS1 (NM_170788.2), rat ELKS2 (NM_001401498.1), human CLIP170 (NM_001247997.2), human LL5β (NM_001134439.2), human GCC185 (NM_181453.3), human CENP-J (NM_018451.4) and human JAKMIP1 (NM_001099433.1) were amplified from human or rat cDNA library and then cloned into a pEGFP-C1, pmCherry-C1, or modified pcDNA3.1 vector with an N-terminal 3×Flag tag. The chimeric proteins, ELKS1ΔIDR/+P3N and CLASP2α+PDZ, were designed by replacing the IDR (residues 1 – 137) of ELKS1 with the N-terminal domain (residues 2 – 82) of Par3 (NM_031235.1) and by fusing the PDZ domain (residues 575 – 684) of RIM1 (XM_017596673) to the C-terminus of CLASP2α, respectively. Human CENP-E (NM_001286734.2) fragments were synthesized by Tsingke Biological Technology. For protein production, ELKS1 and CLIP170 were cloned into a pCAG vector with an N-terminal Flag tag. CLASP2_TOG4 (residues 1251 – 1479) and fragments of ELKS1, ELKS2, LL5β, CLIP170, GCC185, CENP-E, JAKMIP1, and CENP-J were subcloned into a modified pET-32a vector with an N-terminal thioredoxin (Trx)-His6-tag. Mutagenesis was performed using the Mut Express II Fast Mutagenesis Kit V2 (Vazyme Biotech). All plasmids were extracted using the MiniPrep or MaxiPrep Kit (TransGen Biotech) and were subsequently sequenced for verification.

Antibodies

The primary antibodies used in this study included mouse anti-β-tubulin (Sangon Biotech, D1930693), 1:500 dilution for immunofluorescence (IF), rabbit anti-Paxillin (Abcam, ab32115), 1:200 dilution for IF, rabbit anti-TGN46 (Proteintech, 13573-1-AP), 1:500 dilution for IF, rabbit anti-CLASP1 (Abcam, ab108620), 1:3000 dilution for western blot (WB), rat anti-CLASP2 (Absea, 32006E03), 1:1000 dilution for WB, rabbit anti-ELKS1 (Proteintech, 22211-1-AP), 1:500 dilution for IF and 1:1000 dilution for WB, rabbit anti-LL5β (Sigma, HPA035147), 1:500 dilution for IF and 1:1000 dilution for WB, mouse anti-GAPDH (Transgene, HC301-02), 1:3000 dilution for WB, mouse anti-GFP (Transgene, HT801), 1:3000 dilution for WB, and mouse anti-Flag (Sigma, F1804), 1:3000 dilution for WB. The secondary antibodies used in this study included anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 7076 S), anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 7074 S), and anti-rat IgG HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 7077 S), 1:3000 dilution for WB, and Alexa Fluor 488/594/647–conjugated anti-mouse/rabbit IgG antibody (Invitrogen), 1:3000 dilution for IF.

Protein expression and purification

The protein fragments were expressed in BL21(DE3) E. coli and induced with 0.2 mM IPTG in LB medium at 16 °C. Following induction, cells were harvested, resuspended in a binding buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and lysed using an ultrahigh-pressure homogenizer (ATS, AH-BASICI). The lysate was centrifuged at ~50,000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was directly applied to a Ni-NTA agarose column that had been pre-equilibrated with the binding buffer. The target protein was eluted with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, and 300 mM imidazole and further purified using a size-exclusion column (HighLoad 26/60 Superdex-200, GE Healthcare) with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The Se-Met derivative CLASP2-TOG4 was produced in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 100 mg/L of lysine, phenylalanine, and threonine, and 50 mg/L of isoleucine, leucine, valine, and selenomethionine (Se-Met). The purification of Se-Met derivative protein was the same as described above.

The full-length proteins of ELKS1, CLIP170, and their mutants were expressed in HEK 293 F cells. After 3 day expression, the HEK cells were collected and rinsed with the PBS buffer. The cells were then lysed using ultrasonication in an ice-bath with a lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EGTA, and protease inhibitor cocktail (TargetMol). The cell lysate was centrifuged at ~50,000 g for 30 min, and the resulting supernatant was then loaded onto anti-Flag beads (GenScript) followed by a 1-h incubation. After extensive washing, the target protein was eluted with the lysis buffer without Triton X-100, supplemented with Flag peptide (500 μg/ml). The eluted protein was further purified using a size exclusion column (Superdex increase-6, GE Healthcare) with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT. The ELKS1 protein quality was further checked using an HT7700 transmission electron microscope (HITACHI) with 100 kV voltage. It is worth noting that even in the presence of high salt conditions, ELKS1ΔIDR/+P3N and CLIP170 formed droplets during purification. The droplets were collected using centrifugation and were subsequently used for LLPS assays.

Analytical size exclusion chromatography

Protein samples with a volume of 100 μl were prepared at a final concentration of 40 μM and loaded onto an analytical size exclusion column (Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare) on an ÄKTA pure system (GE Healthcare). The column was pre-equilibrated with the same buffer that was used for the protein purification.

Crystallization and X-ray data collection

For crystallization, the freshly purified CLASP2_TOG4 and ELKS2_CC3 proteins were concentrated to ~10 mg/ml and mixed with CENP_CC, CLIP-170_CC, or LL5β_CC and LL5β_EBM at a molar ratio of 1:1.2, respectively. In addition, to ensure the CLASP2_TOG4 forms a stable 1:1 complex with LL5β_TBM during crystallization, the LL5β_TBM sequence was fused to the C-terminus of CLASP2_TOG4 with a thrombin cleavage sequence in between them, resulting in a chimeric protein of CLASP2_TOG4+LL5β_TBM. Crystals were grown by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at 16 °C in a reservoir solution containing 0.2 M ammonium acetate, 0.1 M Tris pH 8.5, 25% w/v polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 for the Se-Met derivative CLASP2_TOG4 in complex with CLIP170_CC, containing 0.2 M NaCl, 0.1 M Tris pH 8.5, and 25% w/v PEG 3,350 for the native CLASP2_TOG4 in complex with CLIP170_CC, containing 0.2 M NaCl, 0.1 M Bis-Tris pH 5.5, and 25% w/v PEG 3,350 for CLASP2_TOG4+LL5β_TBM, containing 0.2 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M Bis-Tris pH 6.5, and 25% w/v PEG 3,350 for the CLASP2_TOG4/LL5β_CC complex, containing 0.1 M HEPES pH 6.5 and 1.4 M sodium citrate for the CLASP2_TOG4/CENP-E_CC complex, or containing 0.2 M ammonium formate pH 6.6 and 20% w/v PEG 3,350 for the ELKS2_CC3/LL5β_EBM complex. Before being stored in liquid nitrogen, the crystals were soaked in a crystallization solution containing an additional 25% glycerol for cryoprotection. The diffraction data of the crystals was collected at the beamline BL17U1, BL18U1, and BL19U1 at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). The data were processed and scaled using HKL200071.

Structure determination and analysis

The structure of CLASP2_TOG4 in complex with CLIP_CC was determined by using single wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) phasing in AutoSol72. The other structures of CLASP2_TOG4 in complex with its targets were determined by molecular replacement in PHASER73 using the CLASP2_TOG4 structure as the search model. The coiled-coil structure of the ELKS2-CC3/LL5β-EBM complex was solved by combinatorial usage of ARCIMBOLDO_LITE74 in CCP475 and PHASER. All the structural models were refined in PHENIX76 and adjusted in COOT77. The model quality was checked by MolProbity77. The final refinement statistics are listed in Table S1. All structure figures were prepared by using PyMOL (https://www.pymol.org).

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

ITC measurements were performed on a PEAQ-ITC Microcal calorimeter (Malvern). The CLASP2_TOG4 or LL5β_EBM were prepared with a concentration of 200 μM in the syringe and the CLIP170_CC, LL5β_TBM, CENP-E_CC, GCC185_CC or ELKS2_CC3 with a concentration of 20 μM in the cell. All the protein samples were prepared in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 and 100 mM NaCl. The titration was processed by injecting 3 μl of sample in the syringe to the cell each time. An interval of 150 s between two injections was set to ensure the curve back to the baseline. The titration data were analyzed and fitted by a one-site binding model.

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa cells and HEK 293 T were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution, and 1% non-essential amino acids. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in an incubator with 5% CO2. Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for HeLa and HEK 293 T cells transfection, and polyethylenimine linear (PEI) MW40000 (YEASEN) was used for HEK 293 F cells transfection.

Immunofluorescence and imaging

Hela cells or HEK293T cells were transfected with constructs and transferred to glass coverslips (treated with 10 mg/ml fibronectin for 1 h) after 24 h. Cells grew on glass coverslips for 12 h. For nocodazole treatment, 10 μM nocodazole was added into the culture medium for different durations. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min at 37 °C or fixed with −20 °C methanol for 10 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, cells were treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature and blocked in 2% Bovine Serum Albumin for 30 min. The cells were stained by primary and secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. In the condensate attachment assay, the cells were first cultured on glass coverslips (treated with 10 mg/ml fibronectin for 1 h) and were transfected after 12 h. The cells were visualized with 100x objective using Nikon A1R and Zeiss LMS980 Confocal Microscopes.

To analyze CLASP2α localization around the FAs, cells were treated with 10 μM nocodazole for 2 h before fixation. Nocodazole treatment eliminates the CLASP2α signal at the microtubule tip, preventing it from being conflated with the signal from CLASP2 at the FA vicinity, and enlarges the FAs, enhancing the visibility of CLASP2 localization at these sites. Notably, the focus plane in microscopic analyses of cortical MTs was set at the ventral region of cells. When imaging, we aimed to minimize the influence of varying protein expression levels by selecting cells with relatively consistent fluorescence intensities. This approach ensured a standard for comparison. For studies focusing on protein localization at specific subcellular structures, such as the ends of MTs or FAs, we prioritized cells with lower expression levels of targets. This selection criterion was based on the observation that high expression levels often result in large puncta formation, which can obscure localization patterns. Conversely, when examining large condensates in the cytoplasm, cells exhibiting higher expression levels of targets were chosen for imaging. This strategy was employed to maximize the visibility of these cellular condensates for quantification analyses.

In vitro LLPS assay

All stock proteins were centrifuged at ~20,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove any precipitations and diluted to designed concentrations with a dilution buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT. For protein fluorescence labeling, Cy3 or iFluor 405 NHS ester (AAT Bioquest) was mixed with the corresponding protein at a 1:1 ratio in the PBS buffer. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The reaction was quenched by adding 200 mM Tris pH 7.5. To remove the unlabeled fluorophores, the labeled proteins were exchanged into a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT using a desalting column. Fluorescence labeling efficiency was measured by NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher). In fluorescent imaging experiments, fluorescently labeled proteins were mixed with the corresponding unlabeled proteins at a 1:50 ratio. Fluorescent images were captured 15 min after the samples were added to a 384-well glass bottom plate (Cellvis). The imaging was conducted using a Nikon A1R Confocal Microscope at room temperature.

siRNA-knockdown

ELKS1, LL5β, CLASP1, and CLASP2 were knocked down in HeLa cells by using siRNA with Lipofectamin 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). Cells were cultivated in 6-well plates prior to transfection. In each well, ELKS1 siRNA78 (20 pmol), LL5β siRNA79 (20 pmol), or CLASP1 (20 pmol) and CLASP2 (40 pmol) siRNAs27, were used. For rescue experiments, cells were co-transfected with 1 μg of DNA per well. Following transfection, the fresh medium was replaced every 24 h. After 60 h post-transfection, the cells were transferred to glass coverslips that had been treated with 10 mg/ml fibronectin for 1 h. The cells were then cultured for an additional 12 h before fixation. The excess cells were sampled with a loading buffer and subsequently used for Western blotting.

Live-cell imaging

HeLa cells were transferred to Nunc Glass Base Dish that had been treated with 10 mg/ml fibronectin for 1 h. A Nikon A1R Confocal Microscope was used for live-cell imaging experiments. Cells were kept in a humidified condition of 5% CO2 in a 37 °C incubation chamber during the experiments.

Superresolution imaging

To analyze the spatial relationship between the ELKS1 condensate and MTs, Single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) was used to image Hela cells transfected with GFP-ELKS1 on the high-precision coverslips (no. 1.5H, CG15XH, Thorlabs). For dual-color staining, GFP-ELKS1 proteins were labeled with anti-GFP nanobodies conjugated Alexa Fluor 647 (FluoTag-Q, N0301-AF647-L, SYSY), and MTs were labeled with anti-β-tubulin (mouse, 1:600, T4026, Sigma) and secondary antibodies conjugated CF680 (anti-mouse, 1:250, 20817, Biotium). For SMLM imaging, samples were immersed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM NaCl, 10% (w/v) glucose, 0.5 mg/ml glucose oxidase (G7141, Sigma), 40 μg/ml catalase (C100, Sigma) and 35 mM cysteamine. SMLM imaging was performed at room temperature on a custom-built microscope. During data acquisition, samples were excited with a 640-nm laser (~2 kW/cm2) and recorded 100,000 frames with 20-ms exposure time, and the z-focus was stabilized by a customized focus lock system.

The raw dual-color data were globally fitted and analyzed with SMAP software as described previously80. The global multi-channel experimental PSF model was generated based on the z stacks of beads (T7279, Invitrogen) on a coverslip. The color of single molecules was assigned by the ratio of the intensities in each channel. For sample drift, the x, y, and z positions were corrected based on a redundant cross-correlation algorithm. The localizations appearing in consecutive frames (within 35 nm) were regarded as a single molecule and thus merged into one localization. To reject dim localizations and bad fits, localizations were filtered by x–y precision (0–20 nm), z precision (0–45 nm), photon count (>800), and relative log-likelihood (>−2.5).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Transfected HEK293T cells were lysed in an ice-cold lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitor cocktail (TargetMol) for 30 min at 4 °C and followed by centrifugation at 12000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, the supernatants were incubated with GFP Nanoab Agarose beads for 1 h at 4 °C. After washing four times in the lysis buffer, the samples were mixed with the loading buffer, then boiled for 10 min, and examined by western blotting.

Western blotting

The prepared samples were separated by 4-12% SDS-PAGE (GenScript, M41212C) and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, IPVH00010). The membranes were sequentially blocked with 3% BSA in TBST buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20, immunoblotted with first antibodies, and probed with HRP-linked antibody secondary antibodies, and finally developed with a chemiluminescent substrate (BioRad, 107-5061). After each step, the membranes were washed three times with TBST buffer. Protein bands were visualized on the Tanon-6011C Chemiluminescent Imaging System (Tanon Science and Technology).

Calculation of MT orientation

The initial step involves segmenting the entire single-cell image into four Regions of Interest (ROIs). These ROI images were then subjected to a two-dimensional Fourier transform to extract their frequency content. Subsequently, an elliptic feature analysis was conducted to quantitatively evaluate the MT distribution. The anisotropic property of the microtubule fibers is characterized by calculating the ratio of the major axis to the minor axis of the resulting ellipse. The MATLAB software was used for calculation, and the corresponding codes were uploaded to the GitHub website (https://github.com/GuoSiqi350/2D-FT-Elliptic-Feature-Analysis.git).

Statistics and data reproducibility

Image pro plus 6.0 software and NIS-Elements A1R Analysis software were used to analyze captured images or movies. Significance was analyzed using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test model. All the statistical analysis was performed and exported to figures using GraphPad Prism 8.0 and Origin 2019.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank the assistance of Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech) Core Research Facilities and Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (beamlines 17U1, 18U1, and 19U1). We are grateful to Prof. Mingjie Zhang and Dr. Fengfeng Niu for their valuable suggestions in improving our manuscript. This work was supported by the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2023B0303010001 to Z.W.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170697 and 32370743 to C.Y., 32371009 to X.X., 32101211 to S.H., and 62375116 to Y.L.), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (RCJC20210609104333007 to Z.W. and 20231121095506001 to C.Y.), Shenzhen-Hong Kong Institute of Brain Science, Shenzhen Fundamental Research Institutions (2023SHIBS0002), Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Biomolecular Assembling and Regulation (ZDSYS20220402111000001), Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (JCYJ20220818100416036 and KQTD20200820113012029), Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (B2301004 to S.H. and B2302038 to Y.L.), and Key Technology Research and Development Program of Shandong (2021CXGC010212). Z.W. and C.Y. are investigators of SUSTech Institute for Biological Electron Microscopy.

Author contributions

Z.W. and C.Y. conceived and supervised the project. X.J., L.L., S.G., L.Z., G.J., J.D., J.X., X.X. designed and performed experiments. X.J., L.L., Y.L., S.H., Z.W., and C.Y. analyzed the data. X.J., L.L., Z.W., and C.Y. wrote the manuscript with inputs from other authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The structure factors and atomic models of CLASP2_TOG4 in complex with CLIP170, LL5β, and CENP-E and the LL5β/ELKS2 complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession codes 8WHH, 8WHI, 8WHJ, 8WHK, 8WHL, and 8WHM. The code used for 2D-FT elliptic feature analysis is available at Zenodo [10.5281/zenodo.12622051]. Source data are provided along with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xuanyan Jia, Leishu Lin.

Contributor Information

Zhiyi Wei, Email: weizy@sustech.edu.cn.

Cong Yu, Email: yuc@sustech.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-50863-3.

References

- 1.Akhmanova, A. & Kapitein, L. C. Mechanisms of microtubule organization in differentiated animal cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.23, 541–558 (2022). 10.1038/s41580-022-00473-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcin, C. & Straube, A. Microtubules in cell migration. Essays Biochem.63, 509–520 (2019). 10.1042/EBC20190016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vicente, J. J. & Wordeman, L. The quantification and regulation of microtubule dynamics in the mitotic spindle. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol.60, 36–43 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Desai, A. & Mitchison, T. J. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol.13, 83–117 (1997). 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nogales, E. Structural insights into microtubule function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct.30, 397–420 (2001). 10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard, J. & Hyman, A. A. Growth, fluctuation and switching at microtubule plus ends. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.10, 569–574 (2009). 10.1038/nrm2713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gudimchuk, N. B. & McIntosh, J. R. Regulation of microtubule dynamics, mechanics and function through the growing tip. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.22, 777–795 (2021). 10.1038/s41580-021-00399-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conde, C. & Cáceres, A. Microtubule assembly, organization and dynamics in axons and dendrites. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.10, 319–332 (2009). 10.1038/nrn2631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muroyama, A. & Lechler, T. Microtubule organization, dynamics and functions in differentiated cells. Development (Cambridge)144, 3012–3021 (2017). 10.1242/dev.153171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhmanova, A. & Steinmetz, M. O. Microtubule +TIPs at a glance. J. Cell Sci.123, 3415–3419 (2010). 10.1242/jcs.062414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akhmanova, A. & Steinmetz, M. O. Control of microtubule organization and dynamics: two ends in the limelight. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.16, 711–726 (2015). 10.1038/nrm4084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akhmanova, A. & Noordstra, I. Linking cortical microtubule attachment and exocytosis. F1000Res.6, 469 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Akhmanova, A. et al. CLASPs are CLIP-115 and −170 associating proteins involved in the regional regulation of microtubule dynamics in motile fibroblasts. Cell104, 923–935 (2001). 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00288-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aher, A. et al. CLASP suppresses microtubule catastrophes through a single TOG domain. Dev. Cell46, 40–58.e8 (2018). 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence, E. J. et al. Human CLASP2 specifically regulates microtubule catastrophe and rescue. Mol. Biol. Cell29, 1168–1177 (2018). 10.1091/mbc.E18-01-0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aher, A. et al. CLASP mediates microtubule repair by restricting lattice damage and regulating tubulin incorporation. Curr. Biol.30, 2175–2183.e6 (2020). 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ambrose, J. C., Shoji, T., Kotzer, A. M., Pighin, J. A. & Wasteneys, G. O. The arabidopsis CLASP gene encodes a microtubule-associated protein involved in cell expansion and division. Plant Cell19, 2763–2775 (2007). 10.1105/tpc.107.053777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bratman, S. V. & Chang, F. Stabilization of overlapping microtubules by fission yeast CLASP. Dev. Cell13, 812–827 (2007). 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence, E. J., Zanic, M. & Rice, L. M. CLASPs at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 133, jcs243097 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Gareil, N. et al. An unconventional TOG domain is required for CLASP localization. Curr. Biol.33, 3522–3528 (2023). 10.1016/j.cub.2023.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]