Abstract

Background

Perineal trauma following vaginal birth can be associated with significant short‐term and long‐term morbidity. Antenatal perineal massage has been proposed as one method of decreasing the incidence of perineal trauma.

Objectives

To assess the effect of antenatal digital perineal massage on the incidence of perineal trauma at birth and subsequent morbidity.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (22 October 2012), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 10), PubMed (1966 to October 2012), EMBASE (1980 to October 2012) and reference lists of relevant articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials evaluating any described method of antenatal digital perineal massage undertaken for at least the last four weeks of pregnancy.

Data collection and analysis

Both review authors independently applied the selection criteria, extracted data from the included studies and assessed study quality. We contacted study authors for additional information.

Main results

We included four trials (2497 women) comparing digital perineal massage with control. All were of good quality. Antenatal digital perineal massage was associated with an overall reduction in the incidence of trauma requiring suturing (four trials, 2480 women, risk ratio (RR) 0.91 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.86 to 0.96), number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) 15 (10 to 36)) and women practicing perineal massage were less likely to have an episiotomy (four trials, 2480 women, RR 0.84 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.95), NNTB 21 (12 to 75)). These findings were significant for women without previous vaginal birth only. No differences were seen in the incidence of first‐ or second‐degree perineal tears or third‐/fourth‐degree perineal trauma. Only women who have previously birthed vaginally reported a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of pain at three months postpartum (one trial, 376 women, RR 0.45 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.87) NNTB 13 (7 to 60)). No significant differences were observed in the incidence of instrumental deliveries, sexual satisfaction, or incontinence of urine, faeces or flatus for any women who practised perineal massage compared with those who did not massage.

Authors' conclusions

Antenatal digital perineal massage reduces the likelihood of perineal trauma (mainly episiotomies) and the reporting of ongoing perineal pain, and is generally well accepted by women. As such, women should be made aware of the likely benefit of perineal massage and provided with information on how to massage.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Delivery, Obstetric; Delivery, Obstetric/adverse effects; Episiotomy; Episiotomy/statistics & numerical data; Massage; Massage/methods; Obstetric Labor Complications; Obstetric Labor Complications/prevention & control; Perineum; Perineum/injuries; Prenatal Care; Prenatal Care/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Antenatal perineal massage for reducing perineal trauma

Antenatal perineal massage helps reduce both perineal trauma during birth and pain afterwards.

Most women are keen to give birth without perineal tears, cuts and stitches, as these often cause pain and discomfort afterwards, and this can impact negatively on sexual functioning. Perineal massage during the last month of pregnancy has been suggested as a possible way of enabling the perineal tissue to expand more easily during birth. The review of four trials (2497 women) showed that perineal massage, undertaken by the woman or her partner (for as little as once or twice a week from 35 weeks), reduced the likelihood of perineal trauma (mainly episiotomies) and ongoing perineal pain. The impact was clear for women who had not given birth vaginally before, but was less clear for women who had. Women should be informed about the benefits of digital antenatal perineal massage.

Background

Genital tract trauma

Trauma to the genital tract commonly accompanies vaginal birth. Perineal trauma is classified as first degree (involving the fourchette, perineal skin and vaginal mucous membrane), second degree (involving the fascia and muscle of the perineal body), third degree (involving the anal sphincter) and fourth degree (involving the rectal mucosa) (Williams 1997). Genital tract trauma can result from episiotomies (incision to enlarge vaginal opening), spontaneous tears or both. Although in some countries the frequency of episiotomy has declined in recent years, overall rates of trauma remain high. There is considerable variation in the reported rates of perineal trauma because of inconsistency in definitions and reporting practices. In studies of restrictive use of episiotomy, 51% to 77% of women still sustained trauma that was considered to be sufficiently extensive to require suturing (Albers 1999; Mayerhofer 2002; McCandlish 1998). Even in a home birth setting, approximately 30% of women experience some degree of perineal trauma (Murphy 1998). Rates of trauma are especially high in women having their first baby (Albers 1999).

Morbidity associated with perineal trauma

Perineal trauma can be associated with significant short‐term and long‐term morbidity. Most women experience perineal pain or discomfort in the first few days after a vaginal birth. Of those women who sustain perineal trauma, 40% report pain in the first two weeks postpartum, up to 20% still have pain at eight weeks (Glazener 1995), and 7% to 9% report pain at three months (McCandlish 1998; Sleep 1987). Women giving birth with an intact perineum, however, report pain less frequently at one, two, 10 and 90 days postpartum (Albers 1999; Klein 1994).

Perineal pain or discomfort is common and may impair normal sexual functioning. Dyspareunia (painful sex) following vaginal delivery is reported by 60% of women at three months, 30% at six months (Barrett 2000) and 15% still experience painful sex up to three years later (Sleep 1987). Trauma to the perineum has been associated with dyspareunia during the first three months after birth (Barrett 2000). Women with an intact perineum (compared with those who have experienced perineal trauma) are more likely to resume intercourse earlier, report less pain with first sexual intercourse, report greater satisfaction with sexual experience (Klein 1994), and report greater sexual sensation and likelihood of orgasm at six months postpartum (Signorello 2001).

Women giving birth to their first baby with an intact perineum have stronger pelvic floors (measured by electromyogram) and make quicker muscle recovery than those women suffering spontaneous tears or episiotomies (Klein 1994). Perineal trauma has not, however, been clearly associated with urinary incontinence (Woolley 1995). Anal sphincter or mucosal injuries are identified following 3% to 4% of all vaginal births. This rate is not reduced by a policy of restrictive use of episiotomy (Carroli 1999). Alarmingly, one‐third of those women who are recognised will suffer some degree of incontinence of faeces (from mild to severe) following primary repair (Sultan 2002). An estimated 35% of primiparas have ultrasound scan evidence of third‐ or fourth‐degree trauma that is unrecognised at delivery and presumably associated with vaginal birth (Sultan 1993).

There is no evidence that birthing practices that aim to reduce perineal trauma are correlated with adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes. Restrictive use of episiotomy results in less posterior perineal trauma, less suturing and fewer healing complications (Carroli 1999). Episiotomy does not reduce the risk of intraventricular haemorrhage in low‐birthweight babies (Woolley 1995), and allowing a longer second stage (and potentially avoiding perineal trauma), has not been shown to be associated with adverse perinatal outcomes (Menticoglou 1995).

Factors associated with perineal trauma

Numerous factors related to the woman or the care she receives have been suggested as potentially affecting the occurrence of genital tract trauma. Perineal trauma is more likely in nulliparas, and is more likely with increasing fetal head diameter and weight, and with malposition (Mayerhofer 2002; Nodine 1987). As mentioned, restrictive use of episiotomy is associated with less perineal trauma (Carroli 1999), as is the use of vacuum extraction for instrumental deliveries as opposed to forceps (Johanson 1999). There is no clear consensus about the role of perineal guarding (Mayerhofer 2002; McCandlish 1998), active directed pushing (Parnell 1993), maternal position (Gupta 2003) or the use of perineal massage during second stage (Stamp 2001) in reducing the incidence of perineal trauma. There is a lack of evidence to associate induction of labour with perineal trauma and only retrospective studies which suggest an association between accoucheur type and perineal trauma (Bodner‐Adler 2004; Shorten 2002). In the event of a perineal injury which requires suturing, a continuous subcuticular technique compared with interrupted sutures has been associated with less pain postpartum (Kettle 1998).

Preventing perineal trauma

The potential morbidity associated with vaginal birth is concerning. It is possible that this is contributing to the increase in requests for caesarean section (Al‐Mufti 1997). Considering these factors, any method proven to reduce the likelihood of sustaining genital tract trauma (and therefore delivery‐associated morbidity) is to be commended. Preventing even some of this childbirth trauma is likely to benefit large numbers of women. It may also result in cost savings in terms of less suturing, drugs and analgesics. Some have advocated the use of perineal massage antenatally in decreasing the incidence of perineal trauma during vaginal birth. It is proposed that perineal massage may increase the flexibility of the perineal muscles and therefore, decrease muscular resistance, which would enable the perineum to stretch at delivery without tearing or needing episiotomy. Our aim is to investigate the role of antenatal digital perineal massage and its effect upon the incidence and morbidity associated with perineal trauma.

Objectives

To assess the effect of antenatal perineal massage on the incidence of perineal trauma at birth and subsequent morbidity.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published and unpublished randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials evaluating any described method of digital antenatal perineal massage were considered for inclusion in the review.

Types of participants

All pregnant women who are planning vaginal birth and have undertaken digital perineal massage for at least the last four weeks of pregnancy.

Types of interventions

Any described method of perineal massage undertaken by women and/or her partner.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

(a) Perineal trauma requiring suturing; (b) first‐degree perineal tear; (c) second‐degree perineal tear; (d) third‐ or fourth‐degree perineal trauma; (e) incidence of episiotomy.

Secondary outcomes

(f) Length of second stage; (g) instrumental delivery; (h) length of inpatient stay; (i) admission to nursery; (j) Apgar less than four at one minute and/or less than seven at five minutes; (k) woman's satisfaction; (l) perineal pain postpartum; (m) ongoing perineal pain postpartum; (n) painful sex postpartum; (o) sexual satisfaction postpartum; (p) uncontrolled loss of urine postpartum; (q) uncontrolled loss of flatus or faeces postpartum.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (22 October 2012).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Coordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above were each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Coordinator searched the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

In addition, we searched CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 10), PubMed (1966 to October 2012) and EMBASE (1980 to October 2012) using the search strategy in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We contacted researchers to provide further information. We contacted experts in the field for additional and ongoing trials. We searched the reference lists of trials and review articles.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 2.

For this update, two review authors independently assessed for inclusion the two reports that were identified as a result of the updated search. We did not include either. If we identify new trials for inclusion in future updates of this review, we will use the methods described in Appendix 3.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Twelve study reports of seven trials (Avery 1986; Foroghipour 2012; Labrecque 1994; Labrecque 1999; Mei‐Dan 2008; Shimada 2005; Shipman 1997) were identified from electronic searches. Four trials are included in this review (Labrecque 1994; Labrecque 1999; Shimada 2005; Shipman 1997), two trials are excluded (Avery 1986; Mei‐Dan 2008) and one is an ongoing trial (Foroghipour 2012).

Included studies

Four trials (Labrecque 1994; Labrecque 1999; Shimada 2005; Shipman 1997) involving 2497 women assessing digital perineal massage performed by the woman or her partner were included in the review. Labrecque 1994 was a pilot paper involving just 46 women. Labrecque 1994, Shimada 2005 and Shipman 1997 studied only women without previous vaginal birth. Labrecque 1999 involved women with and without a previous vaginal birth and the randomisation of participants was stratified by parity. The trial participants were also followed up with a questionnaire that was subsequently reported in 2001 (Labrecque 2001).

Excluded studies

Two trials (three study reports) were excluded (Avery 1986; Mei‐Dan 2008).

Risk of bias in included studies

Details for each trial are in the table of Characteristics of included studies, Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

All included trials of digital perineal massage were of good quality. Given the nature of the intervention, it was not possible for any of the studies to blind participants to the intervention. The trials all recommended a similar technique of digital perineal massage which was undertaken at a similar gestation. The authors all instructed participants not to inform their birth attendant of their allocation and some attempt was made by authors of three of the four included studies to ensure adequate blinding of outcome assessment was upheld. The three month follow‐up questionnaire was returned by 79% of trial participants (with similar response rates from women in the massage and control groups).

Effects of interventions

We included four trials of digital perineal massage (involving a total of 2497 women) in the review. All four trials (Labrecque 1994; Labrecque 1999; Shimada 2005; Shipman 1997) report findings for a total of 2004 women without previous vaginal birth. Labrecque 1999 is the single trial reporting findings for an additional 493 women with previous vaginal birth.

Digital perineal massage versus control

Primary outcomes

(A) Perineal trauma requiring suturing

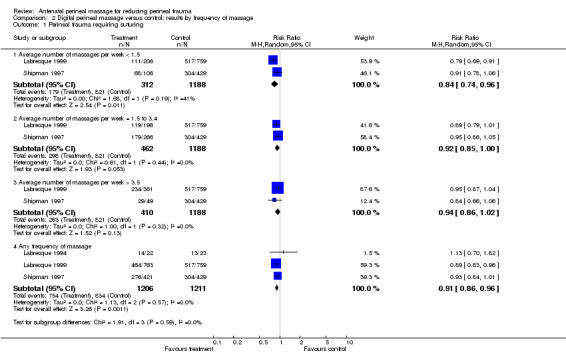

Perineal massage was associated with an overall 9% reduction in the incidence of trauma requiring suturing (four trials, 2480 women, risk ratio (RR) 0.91; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.86 to 0.96), number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) 15 (10 to 36)), Analysis 1.1. This reduction was statistically significant for women without previous vaginal birth only (four trials, 1988 women, RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.96), NNTB 14 (9 to 32)). Subgroup analysis revealed that women who massaged up to an average of 1.5 times per week experienced a 16% reduction (two trials, 1500 women, RR 0.84 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.96), NNTB 9 (6 to 18)), women who massaged an average of 1.5 to 3.4 times per week experienced a 8% reduction (two trials, 1650 women, RR 0.92 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.00), NNTB 22 (10 to 208)), while women who massage more than 3.5 times per week did not experience a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of trauma requiring suturing (two trials, 1598 women, average RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.02); Tau² = 0.00; I² = 0%), Analysis 2.1. There were no differences between subgroups according to the test for subgroup differences, interaction test (Chi² = 1.91; P = 0.59; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 1 Perineal trauma requiring suturing.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 1 Perineal trauma requiring suturing.

(B) First‐degree perineal tear

There was no difference in the incidence of first‐degree perineal tear overall (four trials, 2480 women, average RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.19); Tau² = 0.04; I² = 40%), Analysis 1.2, or in any subgroup.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 2 1st degree perineal tear.

(C) Second‐degree perineal tear

There was no difference in the incidence of second‐degree perineal tear overall (four trials, 2480 women, RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.15)), Analysis 1.3, or in any subgroup.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 3 2nd degree perineal tear.

(D) Third‐ or fourth‐degree perineal trauma

There was no difference in the incidence of third‐ or fourth‐degree perineal trauma overall (four trials, 2480 women, RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.18)), Analysis 1.4, or in any subgroup.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 4 3rd or 4th degree perineal trauma.

(E) Incidence of episiotomy

Women who practised perineal massage were 16% less likely to have an episiotomy (four trials, 2480 women, RR 0.84 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.95), NNTB 21 (12 to 75)), Analysis 1.5. Again, this reduction was statistically significant for women without previous vaginal birth only (four trials, 1988 women, RR 0.83 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.95), NNTB 18 (11 to 70)), Analysis 1.5.1. There were no differences between subgroups according to the test for subgroup differences, interaction test (Chi² = 0.02; P = 0.89; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.5). Only the subgroup of women who massaged up to an average of 1.5 times per week experienced a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of episiotomy (two trials, 1500 women, RR 0.72 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.91), NNTB 12 (7 to 31)), Analysis 2.5.1. No such effect was seen in women who massaged more frequently. Again, There were no differences between subgroups according to the test for subgroup differences, interaction test (Chi² = 2.72; P = 0.44; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 5 Incidence of episiotomy.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 5 Incidence of episiotomy.

Secondary outcomes

(F) Length of second stage

No difference in length of second stage was seen overall (two trials, 2211 women, mean difference (MD) 3.84 minutes (95% CI ‐0.26 to 7.95)), Analysis 1.6, or comparing women with and without previous vaginal births. The women who massaged on average more than 3.5 times per week (but not the subgroups of women who massaged less frequently) had a statistically significant longer second stage (two trials, 1509 women average MD 10.80 minutes (95% CI 4.03 to 17.58); Tau² = 0.00; I² =0%), Analysis 2.6. There were differences between subgroups according to the test for subgroup differences, interaction test (Chi² = 8.33; P = 0.04; I² = 64%; Analysis 2.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 6 Length of second stage.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 6 Length of second stage.

(G) Instrumental delivery

There was no difference in the proportion of instrumental deliveries performed overall (three trials, 2417 women, average RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.16); Tau² = 0.01; I² = 33%), Analysis 1.7, or in any subgroup.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 7 Instrumental delivery.

(H) Length of inpatient stay

Length of inpatient stay was not recorded in any of the included studies.

(I) Admission to nursery

Admission to nursery was not recorded in any of the included studies.

(J) Apgar less than four at one minute and/or less than seven at five minutes

Apgar scores were not recorded in any of the included studies.

(K) Woman's satisfaction with perineal massage

Woman's satisfaction was not recorded in any of the included studies; however, a subsequent paper (Labrecque 2001) did report women's views on the practice of perineal massage (seeDiscussion).

(L) Perineal pain postpartum

Perineal pain in the days following birth was not recorded in any of the included studies.

(M) Ongoing perineal pain postpartum

One trial involving 931 women reported perineal pain at three months postpartum. Overall there was no difference in the reporting of perineal pain at three months postpartum (RR 0.64 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.06), Analysis 1.13. Women who had previously birthed vaginally (and not nulliparas) were statistically significantly less likely to report perineal pain at three months postpartum (one trial, 376 women, RR 0.45 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.87) NNTB 13 (7 to 60); Tau² = 0.07; I² = 51%), Analysis 1.13.2, as were the subgroup of women who most frequently massaged (one trial, 701 women, RR 0.51 (95% CI 0.33 to 0.79) NNTB 11 (7 to 24)), Analysis 2.13.3. There were no differences between subgroups according to the test for subgroup differences, interaction test, for either of the subgroup analyses: (Chi² = 2.02; P = 0.16; I² = 50.4%; Analysis 1.13) (Chi² = 4.70; P = 0.20; I² = 36.1%; Analysis 2.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 13 Perineal pain at 3 months postpartum.

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 13 Perineal pain at 3 months postpartum.

(N) Painful sex postpartum

No differences in the reporting of painful sex at three months postpartum were detected overall (one trial, 831 women, RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.08)), Analysis 1.14, or in any subgroup.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 14 Painful sex at 3 months postpartum.

(O) Sexual satisfaction postpartum

One trial involving 921 woman reported the woman's sexual satisfaction at three months postpartum. No difference was seen overall (RR 1.02 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.10)), Analysis 1.15, or in any subgroup. In one trial, 916 women responded to questions about their partner's sexual satisfaction at three months postpartum. Again, no difference was seen overall (RR 0.97 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.04)), Analysis 1.16, or in any subgroup.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 15 Woman's sexual satisfaction at 3 months postpartum.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 16 Partner's sexual satisfaction at 3 months postpartum.

(P) Uncontrolled loss of urine postpartum

No difference was seen in the proportion of women reporting incontinence of urine at three months postpartum overall (one trial, 949 women, RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.08)), Analysis 1.17, or in any subgroup.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 17 Uncontrolled loss of urine at 3 months postpartum.

(Q) Uncontrolled loss of flatus or faeces postpartum

No difference was seen in the overall proportion of women reporting incontinence of flatus at three months postpartum (one trial, 948 women, RR 1.09 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.36); ), Analysis 1.19, or comparing women with and without a previous vaginal birth. Only the subgroup of women who massaged an average of less than 1.5 times per week reported flatal incontinence more frequently than controls (one trial, 587 women, RR 1.40 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.90) NNTB 10 (5 to 1111)), Analysis 2.19.1. Within this subgroup, there was no difference in the reporting of infrequent flatal incontinence (RR 0.87 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.26)), Analysis 2.19.2, however, more women reported flatal incontinence occurring at least daily (RR 2.66 (95% CI 0.99 to 7.16)). This finding is based on very small numbers (6/108 versus 10/479) and hence the significance of this finding is unclear ‐ seeTable 1. No difference was seen in the proportion of women reporting incontinence of faeces at three months postpartum overall (one trial, 948 women, RR 0.70 (95% CI 0.27 to 1.80), Analysis 1.18, or in any subgroup.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 19 Uncontrolled loss of flatus at 3 months postpartum.

2.19. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 19 Uncontrolled loss of flatus at 3 months postpartum.

1. Flatal incontinence at 3 months postpartum in women who massage less than 1.5 times per week.

| Treatment | Control | Risk ratio, M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI | |||

| Events | Total | Events | Total | ||

| Reporting of infrequent flatal incontinence | 21 | 108 | 107 | 479 | 0.87 (0.57,1.32) |

| Reporting of flatal incontinence at least daily | 6 | 108 | 10 | 479 | 2.66 (0.99,7.16) |

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity, Outcome 18 Uncontrolled loss of faeces at 3 months postpartum.

Discussion

Women who practise digital perineal massage from approximately 35 weeks' gestation are less likely to have perineal trauma which requires suturing in association with vaginal birth. For every 15 women who practise digital perineal massage antenatally, one fewer will receive perineal suturing following the birth. There is no difference in the proportion of women who incur first‐ or second‐degree perineal tears or third/fourth degree perineal trauma comparing those who massage with controls. There is, however, a statistically significant 16% reduction in the incidence of episiotomies in women who practise digital perineal massage. Thus the reduction in perineal trauma requiring suturing following vaginal birth is almost entirely due to the fact that she is less likely to have an episiotomy. These reductions are significant for the subgroup of women who have never previously had a vaginal birth. There is no statistical difference in these outcomes for women who have previously birthed vaginally; however, only one included trial studied this group of women.

For the subgroup of women who have previously had a vaginal birth, antenatal perineal massage reduces the likelihood of perineal pain at three months in the sole study that assessed this outcome. The women who massage the most frequently are the least likely to report ongoing perineal pain postpartum. We proposed that this reduction in perineal pain at three months was because women who practise perineal massage are less likely to have an episiotomy and that having had an episiotomy is the most likely reason for ongoing pain. However, when we analysed the data excluding women who had episiotomies, this effect remained. In other words, for women who have had a previous vaginal birth, antenatal perineal massage appears to result in less reporting of perineal pain at three months even for those women who do not have an episiotomy. Women who massage the most frequently may not be able to further reduce their chance of an episiotomy but may lessen their likelihood of perineal pain at three months.

No significant differences are observed in the incidence of instrumental deliveries, sexual satisfaction, or incontinence of urine, faeces or flatus for any women who practise perineal massage compared with those who do not massage in the study that reported these outcomes.

Surprisingly the reduction in the incidence of episiotomy and of perineal trauma requiring suturing is not more pronounced in the women who massage the most frequently. It is also an unexpected finding that the subgroup of women who massage the most frequently have the longest second stage. If the reason that perineal massage works is that it increases the flexibility and decreases the resistance of the perineal muscles and soft tissues, then it would be anticipated that the most diligent massager should have the least chance of needing suturing and have a relatively short second stage. As this effect was not seen, there may be other reasons that women who practise perineal massage are less likely to incur perineal trauma (mainly episiotomies) that requires suturing. The decision regarding if and when an episiotomy is cut is a subjective one. We therefore considered the adequacy of blinding. We also considered the possibility that women who were instructed in perineal massage became very motivated to achieve a vaginal birth with an intact perineum and consequently, may have been more likely to want to keep pushing longer and oppose an episiotomy unless it was clearly necessary.

We proceeded to exclude women who had an episiotomy and reassess length of second stage (seeTable 2). No significant differences were seen in the length of second stage after excluding women who had an episiotomy. If birth attendants were unblinded, we propose that after excluding episiotomies, the remaining women in the massage group would still have been encouraged to push longer while those in the control group would have had an overall shorter second stage (as the controls who avoided episiotomy likely delivered quickly). The net effect would therefore be an overall increase in the length of second stage when compared with controls. As this effect was not seen, we considered it less likely that unblinding occurred.

2. Length of second stage perineal massage versus control: analysis excluding episiotomies.

| Duration | All women | Excl episiotomy |

| Length of 2nd stage (mins) | +3.84 (95% CI ‐0.26 to +7.95) | +3.57 (95% CI ‐0.86 to +8.00) |

| Length of 2nd stage for women massaging more than 3.5 times/week (mins) | +10.80 (95% CI +4.03 to +17.58) | +5.21 (95% CI ‐1.45 to +11.86) |

mins: minutes CI: confidence interval

If the motivation of the informed woman for an intact perineum explains the reduction in trauma, then those who massaged the most frequently would likely have had the longest second stage (as was seen). Further, women in the control group who were less informed and motivated about preventing perineal trauma, may have been less likely to push for as long and more receptive to an episiotomy if suggested. By excluding women who had episiotomies, the time spent pushing for women who practise perineal massage should be reduced (particularly for the subgroup of women who massaged the most frequently). When this analysis was performed we did see a reduction in the length of second stage in this subgroup. This weighs against the supposition that perineal massage reduces the incidence of episiotomy because of increased flexibility of the perineum. Nevertheless, it appears that women who are instructed in perineal massage (either because they become more informed about birthing, episiotomies and the advantages of an intact perineum, or because of the act of massaging itself) are less likely to have an episiotomy, require perineal suturing or report ongoing perineal pain postpartum.

Most women find the practice of perineal massage acceptable and believe it helps them prepare for birth (Labrecque 2001). (Details regarding the technique of perineal massage as described by Labrecque and Shipman are provided under Characteristics of included studies). Women comment that in the first few weeks massage can be uncomfortable, unpleasant and even produce a painful or burning sensation. Most women report that the pain and burning sensation has decreased or gone by the second or third week of massage. The majority (79%) report they would massage again and 87% would recommend it to another pregnant woman. Most women considered their partner's participation as positive.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Perineal trauma is associated with significant postpartum morbidity. Antenatal digital perineal massage from approximately 35 weeks' gestation reduces the incidence of perineal trauma requiring suturing (mainly episiotomies) and women are less likely to report perineal pain at three months postpartum (regardless of whether or not an episiotomy was performed). Although there is some transient discomfort in the first few weeks, it is generally well accepted by women. As such, women should be made aware of the likely benefit of perineal massage and provided with information on how to massage.

Implications for research.

There are reasonable data supporting the reduction in perineal trauma requiring suturing in women who practise antenatal perineal massage. The reported outcomes of perineal pain, sexual satisfaction and incontinence are however based on one study and such findings need confirmation. More data are also needed regarding women who have previously had a vaginal birth before reaching conclusions about the effect of perineal massage on perineal trauma in this group.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 November 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Results and conclusions are unchanged. |

| 12 November 2012 | New search has been performed | A new search found two studies (Mei‐Dan 2008; Foroghipour 2012). One of these is the full study report of an already excluded trial (Mei‐Dan 2008) and one is a report of an ongoing trial (Foroghipour 2012). References to perineal massage using massage device have been removed following publication of dedicated Cochrane protocol. Methods have been updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2005 Review first published: Issue 1, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 July 2008 | New search has been performed | A new search found two studies (Shimada 2005; Mei‐Dan 2004); only one has been included (Shimada 2005). The meta‐analysis has been updated. Results and conclusions are unchanged. |

| 9 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrea Garrett for her contribution to previous versions of this review. Andrea worked collaboratively on the development of the protocol, undertook selection of trials for inclusion, quality assessment, data extraction and commented on drafts of the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 10), PubMed (1966 to October 2012) and EMBASE (1980 to October 2012) adapted for each database by selecting appropriate subject headings and/or free text terms.

#1 PERINEUM (MeSH) #2 perine* #3 MASSAGE (MeSH) #4 massag* #5 EPISIOTOMY (MeSH) #6 episiotom* #7 LACERATION (MeSH) #8 lacerat* #9 #1 or #2 #10 #3 or #4 #11 #5 or #6 #12 #7 or #8 #13 #9 and #10 #14 #11 and #10 #15 #12 and #10 #16 #13 or #14 or #15

Appendix 2. Data collection and analysis ‐ methods used in previous versions

We considered for inclusion all studies identified by the search strategy outlined above. Both review authors independently evaluated trials under consideration for appropriateness for inclusion and methodological quality without consideration of their results. Any differences of opinion were resolved by open discussion. We recorded and reported in the review the reasons for excluding trials. Both review authors independently entered the extracted data into Review Manager (RevMan 2008). We performed statistical analyses using Review Manager.

We assessed included trial data as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We described methods used for generation of the randomisation sequence for each trial.

(1) Selection bias (allocation concealment)

We assigned a quality score for each trial, using the following criteria:

(A) adequate concealment of allocation, such as: telephone randomisation, consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes;

(B) unclear whether adequate concealment of allocation, such as: list or table used, sealed envelopes, or study does not report any concealment approach;

(C) inadequate concealment of allocation, such as: open list of random‐number tables, use of case record numbers, dates of birth or days of the week.

(2) Attrition bias (loss of participants, e.g. withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We assessed completeness to follow up using the following criteria:

(A) less than 5% loss of participants;

(B) 5% to 9.9% loss of participants;

(C) 10% to 19.9% loss of participants;

(D) more than 20% loss of participants.

(3) Performance bias (blinding of participants, researchers and outcome assessment)

We assessed blinding using the following criteria: (A) blinding of participants (yes/no/unclear); (B) blinding of caregiver (yes/no/unclear); (C) blinding of outcome assessment (yes/no/unclear).

For dichotomous data we calculated the relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CI) and pooled the results using a fixed‐effect model. For continuous data we used mean differences and 95% CI. We evaluated statistical heterogeneity by a visual inspection of forest plots and using the I² statistic as calculated in 'RevMan Analyses'. We detected no significant heterogeneity (I² statistic greater than 50%) in any of the outcome measures.

We attempted to undertake the following subgroup analyses: (a) women with previous vaginal birth versus without previous vaginal birth; (b) digital perineal massage versus massaging device; (c) daily perineal massage versus less frequent perineal massage.

Appendix 3. Data collection and analysis ‐ methods to be used in future updates

Selection of studies

Two review authors will independently assess for inclusion all the potential studies we identify as a result of the search strategy. We will resolve any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we will consult the third review author.

We will design a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors will extract the data using the agreed form. We will resolve discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we will consult the third review author. Data will be entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above is unclear, we will attempt to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors will independently assess risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement will be resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We will describe for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We will assess the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We will describe for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and will assess whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We will assess the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We will describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We will consider that studies are at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judge that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We will assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We will assess the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We will describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We will assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We will assess methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We will describe for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We will state whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information is reported, or can be supplied by the trial authors, we will re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertake.

We will assess methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We will describe for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We will assess the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We will describe for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We will make explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we will assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it is likely to impact on the findings. We will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we will present results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we will use the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We will include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. Their sample sizes or standard errors will be adjusted using the methods described in the Handbook using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), or from another source. If ICCs from other sources are used, this will be reported and sensitivity analyses conducted to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a separate meta‐analysis.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials will be excluded from this review.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, levels of attrition will be noted. The impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect will be explored by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, analyses will be carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis i.e. we will attempt to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial will be the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We will assess statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We will regard heterogeneity as substantial if I² is greater than 50% and either T² is greater than zero, or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identify substantial heterogeneity (above 50%), we will explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We will carry out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We will use fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it is reasonable to assume that studies are estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. If there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity is detected, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials. If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We plan to carry out the following subgroup analyses:

women with previous vaginal birth versus without previous vaginal birth;

digital perineal massage versus massaging device;

daily perineal massage versus less frequent perineal massage.

Subgroup analyses will be conducted on all the review's outcomes.

We will assess differences between subgroups by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2011).

Sensitivity analysis

We plan to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor quality studies being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this makes any difference to the overall result.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Digital perineal massage versus control: results by parity.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Perineal trauma requiring suturing | 4 | 2480 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.86, 0.96] |

| 1.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 4 | 1988 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.84, 0.96] |

| 1.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 492 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.83, 1.08] |

| 2 1st degree perineal tear | 4 | 2480 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.78, 1.19] |

| 2.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 4 | 1988 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.69, 1.36] |

| 2.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 492 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.72, 1.41] |

| 3 2nd degree perineal tear | 4 | 2480 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.85, 1.15] |

| 3.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 4 | 1988 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.84, 1.19] |

| 3.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 492 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.72, 1.29] |

| 4 3rd or 4th degree perineal trauma | 4 | 2480 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.56, 1.18] |

| 4.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 4 | 1988 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.56, 1.20] |

| 4.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 492 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.05, 5.52] |

| 5 Incidence of episiotomy | 4 | 2480 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.74, 0.95] |

| 5.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 4 | 1988 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.73, 0.95] |

| 5.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 492 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.57, 1.30] |

| 6 Length of second stage | 2 | 2211 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.84 [‐0.26, 7.95] |

| 6.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 2 | 1719 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.16 [‐3.58, 7.91] |

| 6.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 492 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.60 [‐0.27, 11.47] |

| 7 Instrumental delivery | 3 | 2417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.77, 1.16] |

| 7.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 3 | 1925 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.78, 1.04] |

| 7.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 492 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.58 [0.83, 3.02] |

| 8 Length of inpatient stay | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Admission to nursery | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Apgar < 4 at 1 minute and/or Apgar < 7 at 5 minutes | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Woman's satisfaction with perineal massage | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Perineal pain postpartum | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13 Perineal pain at 3 months postpartum | 1 | 931 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.39, 1.06] |

| 13.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 1 | 555 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.55, 1.09] |

| 13.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 376 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.24, 0.87] |

| 14 Painful sex at 3 months postpartum | 1 | 831 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.84, 1.08] |

| 14.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 1 | 493 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.85, 1.11] |

| 14.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 338 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.68, 1.24] |

| 15 Woman's sexual satisfaction at 3 months postpartum | 1 | 921 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.96, 1.10] |

| 15.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 1 | 552 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.93, 1.14] |

| 15.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 369 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.93, 1.11] |

| 16 Partner's sexual satisfaction at 3 months postpartum | 1 | 916 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.91, 1.04] |

| 16.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 1 | 548 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.90, 1.09] |

| 16.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 368 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.87, 1.03] |

| 17 Uncontrolled loss of urine at 3 months postpartum | 1 | 949 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.74, 1.08] |

| 17.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 1 | 572 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.71, 1.20] |

| 17.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.66, 1.13] |

| 18 Uncontrolled loss of faeces at 3 months postpartum | 1 | 948 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.27, 1.80] |

| 18.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 1 | 572 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.41, 2.54] |

| 18.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 376 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.10, 1.41] |

| 19 Uncontrolled loss of flatus at 3 months postpartum | 1 | 948 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.88, 1.36] |

| 19.1 Women without previous vaginal birth | 1 | 571 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.85, 1.50] |

| 19.2 Women with previous vaginal birth | 1 | 377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.74, 1.45] |

Comparison 2. Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Perineal trauma requiring suturing | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 2 | 1500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.74, 0.96] |

| 1.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 2 | 1650 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.85, 1.00] |

| 1.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 2 | 1598 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.86, 1.02] |

| 1.4 Any frequency of massage | 3 | 2417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.86, 0.96] |

| 2 1st degree perineal tear | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 2 | 1500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.60, 1.83] |

| 2.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 2 | 1650 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.75, 1.33] |

| 2.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 2 | 1598 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.67, 1.17] |

| 2.4 Any frequency of massage | 3 | 2417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.71, 1.38] |

| 3 2nd degree perineal tear | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 2 | 1500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.78, 1.27] |

| 3.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 2 | 1650 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.75, 1.16] |

| 3.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 2 | 1598 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.82, 1.27] |

| 3.4 Any frequency of massage | 3 | 2417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.84, 1.14] |

| 4 3rd or 4th degree perineal trauma | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 2 | 1500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.08, 8.48] |

| 4.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 2 | 1650 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.33, 1.25] |

| 4.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 2 | 1598 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.78, 1.81] |

| 4.4 Any frequency of massage | 3 | 2417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.56, 1.19] |

| 5 Incidence of episiotomy | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 2 | 1500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.57, 0.91] |

| 5.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 2 | 1650 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.77, 1.08] |

| 5.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 2 | 1598 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.67, 1.04] |

| 5.4 Any frequency of massage | 3 | 2417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.75, 0.97] |

| 6 Length of second stage | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 2 | 1403 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [‐6.45, 8.39] |

| 6.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 2 | 1525 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.38 [‐8.55, 3.79] |

| 6.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 2 | 1509 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 10.80 [4.03, 17.58] |

| 6.4 Any frequency of massage | 2 | 2211 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.35 [‐1.29, 8.00] |

| 7 Instrumental delivery | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 2 | 1500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.71, 1.13] |

| 7.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 2 | 1650 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.72, 1.07] |

| 7.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 2 | 1598 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.86, 1.33] |

| 7.4 Any frequency of massage | 3 | 2417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.76, 1.13] |

| 8 Length of inpatient stay | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.4 Any frequency of massage | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Admission to nursery | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.4 Any frequency of massage | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Apgar < 4 at 1 minute and/or Apgar < 7 at 5 minutes | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.4 Any frequency of massage | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Woman's satisfaction with perineal massage | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 11.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.4 Any frequency of massage | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Perineal pain postpartum | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 12.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.4 Any frequency of massage | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13 Perineal pain at 3 months postpartum | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 13.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 1 | 577 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.65, 1.56] |

| 13.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 1 | 595 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.42, 1.13] |

| 13.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 1 | 701 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.33, 0.79] |

| 13.4 Any frequency of massage | 1 | 931 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.50, 0.92] |

| 14 Painful sex at 3 months postpartum | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 14.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 1 | 521 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.67, 1.08] |

| 14.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 1 | 538 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.85, 1.25] |

| 14.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 1 | 622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.81, 1.13] |

| 14.4 Any frequency of massage | 1 | 831 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.83, 1.09] |

| 15 Woman's sexual satisfaction at 3 months postpartum | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 15.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 1 | 569 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.93, 1.16] |

| 15.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 1 | 588 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.98, 1.19] |

| 15.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 1 | 692 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.90, 1.08] |

| 15.4 Any frequency of massage | 1 | 921 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.96, 1.10] |

| 16 Partner's sexual satisfaction at 3 months postpartum | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 16.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 1 | 576 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.91, 1.11] |

| 16.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 1 | 586 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.95, 1.13] |

| 16.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 1 | 688 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.86, 1.02] |

| 16.4 Any frequency of massage | 1 | 916 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.91, 1.04] |

| 17 Uncontrolled loss of urine at 3 months postpartum | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 17.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 1 | 587 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.83, 1.46] |

| 17.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 1 | 606 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.62, 1.15] |

| 17.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 1 | 714 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.65, 1.06] |

| 17.4 Any frequency of massage | 1 | 949 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.74, 1.08] |

| 18 Uncontrolled loss of faeces at 3 months postpartum | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 18.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 1 | 586 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.36, 3.03] |

| 18.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 1 | 605 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.10, 1.89] |

| 18.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 1 | 713 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.29, 1.80] |

| 18.4 Any frequency of massage | 1 | 948 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.35, 1.49] |

| 19 Uncontrolled loss of flatus at 3 months postpartum | 1 | 2854 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.95, 1.25] |

| 19.1 Average number of massages per week < 1.5 | 1 | 587 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [1.03, 1.90] |

| 19.2 Average number of massages per week = 1.5 to 3.4 | 1 | 606 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.60, 1.26] |

| 19.3 Average number of massages per week > 3.5 | 1 | 713 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.82, 1.39] |

| 19.4 Any frequency of massage | 1 | 948 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.88, 1.36] |

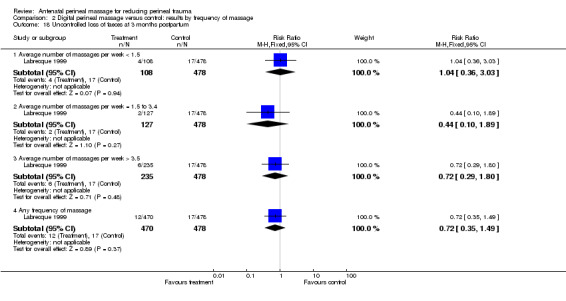

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 2 1st degree perineal tear.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 3 2nd degree perineal tear.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 4 3rd or 4th degree perineal trauma.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 7 Instrumental delivery.

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 14 Painful sex at 3 months postpartum.

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 15 Woman's sexual satisfaction at 3 months postpartum.

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 16 Partner's sexual satisfaction at 3 months postpartum.

2.17. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 17 Uncontrolled loss of urine at 3 months postpartum.

2.18. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Digital perineal massage versus control: results by frequency of massage, Outcome 18 Uncontrolled loss of faeces at 3 months postpartum.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Labrecque 1994.

| Methods | Randomisation using table of random numbers. Concealment of allocation by sealed, numbered, opaque envelopes. Participants asked not to tell their healthcare providers their assignment. Secrecy instruction upheld by 93.3%. All participants entered into trial included in analysis. | |

| Participants | 46 women without previous vaginal birth between 32‐34 weeks, singleton. Excluded if likely caesarean section or history of genital herpes in pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Woman or partner performed daily 5‐10 minute perineal massage from 34 weeks. 1‐2 fingers introduced 3‐4 cm in vagina, applying alternating downward and sideward pressure using sweet almond oil. Explained using foam perineal model in 15‐20 minute session. Written instructions given and telephone follow‐up 1 and 3 weeks after enrolment to encourage compliance. Given diary to record daily practice. Control group received no instruction on massage. | |

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery, incidence of episiotomy, incidence of perineal tear. | |

| Notes | Pilot study. Intervention group asked to complete questionnaire regarding acceptability of perineal massage. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation using table of random numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Concealment of allocation by sealed, numbered, opaque envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants asked not to tell physicians their assignment. Secrecy instruction upheld by 93.3%. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ All participants entered into trial included in analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Small pilot study only. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Labrecque 1999.

| Methods | Multicentre trial. Randomisation (stratified by whether or not previous vaginal birth) using table of random numbers. Concealment of allocation by sealed, numbered, opaque envelopes. No breaches of sequential assignment. Participants asked not to tell their healthcare providers their assignment. Unblinding of study group in 5.6%. All participants entered into trial included in the analysis. Three months after delivery participants mailed a questionnaire. 79% response rate, similar between massage group and controls. | |

| Participants | 1034 women without previous vaginal birth and 493 women with previous vaginal birth between 30‐35 weeks, singleton. Excluded if high likelihood of delivery by caesarean section, history of genital herpes during pregnancy, inability to understand instructions or already practising perineal massage. 572 women without previous vaginal birth and 377 women with previous vaginal birth returned the subsequent questionnaire. | |

| Interventions | Woman or partner performed daily 10 minute perineal massage from 34 weeks. 1 or 2 fingers introduced 3 to 4 cm in vagina, applying alternating downward and sideward pressure using sweet almond oil. Explained using foam perineal model in 15 to 20 minute session. Written instructions were offered and telephone follow‐up 1 and 3 weeks after enrolment to encourage compliance. Given diary to record daily practice. Control group received no instruction on massage. | |

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery, incidence of episiotomy, incidence of perineal tear, satisfaction with birth. Questionnaire at 3 months assessed self‐reported pain, sexual function of woman and partner, urinary, faecal and flatal incontinence. | |

| Notes | Contact with author provided results by frequency of massage. Data from questionnaire at 3 months is also reported by Eason 2002. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation (stratified by whether or not previous vaginal birth) using table of random numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Concealment of allocation by sealed, numbered, opaque envelopes. No breaches of sequential assignment. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants asked not to tell physicians their assignment. Unblinding of study group in 5.6%. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ All participants entered into trial included in the analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Contact with author provided results by frequency of massage. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Shimada 2005.

| Methods | Randomisation was carried out by phone by an independent organisation. Concealment achieved by drawing a sealed opaque envelope from a closed box. Participants were asked not to tell healthcare providers their assignment. No process documented to check blinding. All participants entered into trial included in the analysis. | |

| Participants | 63 women without previous vaginal birth between 34 to 36 weeks. Excluded if high likelihood of birth by caesarean section. | |

| Interventions | Woman or partner performed 5 minutes of perineal massage following bath or shower using sweet almond oil. No specific description of technique. Massage performed 4 times per week. Given diary to record practice. Weekly face‐to‐face meeting with trial coordinator to reinforce technique and aid compliance. Control group received no instruction on massage. | |

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery, incidence of episiotomy, incidence of perineal tear. | |

| Notes | Article in Japanese. Unable to communicate with author for further clarification. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ The method described appears to have successfully concealed allocation. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Participants were asked not to tell healthcare providers their assignment. No process documented to check blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ All participants entered into trial included in the analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Article in Japanese. Unable to communicate with author for further clarification. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Shipman 1997.

| Methods | Computer‐generated random numbers. Concealment of allocation by indistinguishable, sealed, numbered envelopes. Participants asked not to tell their healthcare providers their assignment. No formal assessment to check blinding but "random checks by trial research midwife indicated that midwives were blind to the group allocation". Outcomes for 179 women who did not deliver vaginally not reported but clarified following correspondence from author. | |

| Participants | 861 women without previous vaginal birth between 29 to 32 weeks, singleton. Excluded if high likelihood of delivery by caesarean section, history of genital herpes during pregnancy, allergy to nuts (contained in massage oil), inability to understand instructions or already practising perineal massage. | |

| Interventions | Woman or partner performed 4 ‐minute perineal massage 3‐4 times per week from 34 weeks. 1 or 2 fingers introduced 5 cm in vagina, applying sweeping downward pressure from 3:00 to 9:00 using provided sweet almond oil. Women given verbal and written instructions. Given diary to record daily practice. Control group received no instruction on massage. Both intervention and control groups encouraged to perform pelvic floor exercises. | |

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery, incidence of perineal trauma. | |

| Notes | Contact with author provided incidence of episiotomy and perineal tears, length of second stage, and results by frequency of massage. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Concealment of allocation by indistinguishable, sealed, numbered envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Participants asked not to tell their healthcare providers their assignment. No formal assessment to check blinding but "random checks by trial research midwife indicated that midwives were blind to the group allocation". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ Outcomes for 179 women who did not deliver vaginally not reported but clarified following correspondence from author. |